Summations

• Exosome-based approaches provide promising insights into the mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment of ASD.

• Exosomal content differs between ASD patients or models and healthy controls, offering potential biomarker candidates.

• Administration of exosomes from healthy sources improved behavioural outcomes in ASD-like mice, highlighting therapeutic potential.

Considerations

• No single, consistent exosomal biomarker has yet been identified across studies, limiting immediate clinical application.

• Variability in reported molecules suggests a need for multi-marker panels rather than reliance on a universal biomarker.

• Current findings are largely preclinical; translation to human diagnosis and treatment remains preliminary.

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterised by difficulties with social communication and interaction as well as restricted, repetitive activities and interests (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Loyacono, Rossignol and Frye2021). The prevalence of ASD is estimated to affect roughly 1.5% of children and youth in North America, highlighting the significance of this condition (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Arbour-Nicitopoulos, Martin Ginis, Latimer-Cheung and Bassett-Gunter2020). The pathophysiology of ASD is multifaceted, involving interactions between genetic and environmental factors (Waye and Cheng, Reference Waye and Cheng2018). Understanding the genetic underpinnings and epigenetic influences on ASD is crucial for unravelling its complexity and developing targeted interventions. Early diagnosis is critical for improving outcomes for people with ASD, highlighting the necessity of appropriate interventions and support services (Fernell et al., Reference Fernell, Eriksson and Gillberg2013).

Because of its prevalence and associated morbidity, early diagnosis of ASD is a current and significant issue. Currently using techniques are clinical observation, behavioural diagnostic criterias and using checklists (Matson et al., Reference Matson, Wilkins and González2008). For the diagnosis of ASD, tools such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) can be used (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Zhong, Zeng, Li and Yao2025). Examples of checklists used for diagnosing ASD include the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT), Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) and the Childhood Autism Spectrum Test (CAST) (Matson et al., Reference Matson, Wilkins and González2008). Besides, numerous studies are ongoing in the fields of genetics, proteomics, metabolomics, machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches, as well as screening and diagnostic tools (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Zhong, Zeng, Li and Yao2025). Finding biomarkers is a challenge due to the heterogeneity of aetiological and clinical approaches in ASD. Therefore, identifying multiple biomarkers or developing person-specific treatments may need to be the main objective of future studies as current evidence-based treatments for ASD are only behavioural and educational interventions, such as applied behaviour analysis (ABA) and family interventions (Bordini et al., Reference Bordini, Moya, Asevedo, Paula, Brunoni, Brentani, Caetano, Mari and Bagaiolo2024; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Zhong, Zeng, Li and Yao2025). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may be another option for comorbid psychiatric disorders such as obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder if applicable (Syriopoulou-Delli and Filiou, Reference Syriopoulou-Delli and Filiou2022). Medications, such as antipsychotics, are used for managing symptoms like irritability, repetitive behaviours, aggression and obsessions (Meza et al., Reference Meza, Franco, Sguassero, Núñez, Escobar Liquitay, Rees, Williams, Rojas, Rojas, Pringsheim and Madrid2025). However, there is no approved medical treatment for the core symptoms of ASD. All these treatments are non-personalised and symptom focused; they do not cure ASD (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Son, Yon and Lee2025).

For this reason, advances in biomedical research have focused on the complex molecular interplay between genes and the environment in the developmental pathophysiology of ASD (Cheroni et al., Reference Cheroni, Caporale and Testa2020). One groundbreaking discovery has been the exosomes, which has the potential to make a non-invasive brain biopsy possible for brain disorders (Cheroni et al., Reference Cheroni, Caporale and Testa2020; De La Monte et al., Reference De La Monte, Yang and Tong2024; Gusar et al., Reference Gusar, Kan, Leonova, Chagovets, Tyutyunnik, Khachatryan, Yarotskaya and Sukhikh2025). Exosomes are small vesicles, approximately 30–100 nm in size, secreted by all cell types. Exosomes are present in many human body fluids, including amniotic fluid, aqueous humour, ascites (peritoneal lavage fluid), blood (plasma and serum), breast milk, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, follicular fluid, malignant pleural effusions, saliva, seminal fluid and synovial fluid. They are secreted into these fluids by various cell types such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), immune cells and tumour cells (Schuh et al., Reference Schuh, Cuenca, Alcayaga-Miranda and Khoury2019). They contain proteins, nucleic acids, metabolites and lipids, and function by transferring these molecules between cells (Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Perocheau, Touramanidou and Baruteau2021). Exosomes also regulate intercellular communication and the extracellular matrix, and influence cell proliferation and differentiation (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Xue, Duan, Mao and Wan2024).

Exosomes are isolated using various methods. Ultracentrifugation and density gradient ultracentrifugation rely on differences in particle size and density. Microfluidics based techniques use parameters such as size, fluid dynamics and immunocompatibility. Immunoaffinity capture isolates exosomes by targeting surface antigens. Polymer based precipitation is based on solubility differences, while ultrafiltration separates exosomes by size. Commercial kits typically combine centrifugation, chemical precipitation and immunoaffinity approaches. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are characterised by determining the CD9 and CD81 membrane-associated markers with Western blot analysis, while their morphology and size can be assessed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The concentration of EV-associated protein can be quantified by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay and also nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) is one of the techniques used for exosome isolation and characterisation. (Ju et al., Reference Ju, Hu, Yang, Xie and Fang2022; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Xue, Duan, Mao and Wan2024).

Exosomes have been studied as potential biomarkers and treatments for a wide range of diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, brain injury and epilepsy; neuropsychiatric conditions such as ASD, depression, bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia; various cancers such as pancreatic and colon cancer; orthopaedic issues including knee osteoarthritis and degenerative meniscal injury; cardiovascular diseases such as atrial fibrillation and other medical applications such as cutaneous nerve injuries, wound healing and treatment of hair loss (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Xue, Duan, Mao and Wan2024; Li et al., Reference Li, Yuan, Xie and Dong2024, Mu et al., Reference Mu, Luo, Zhao, Chen, Cao, Jin, Li and Wang2025).

In the field of neurodegenerative diseases, exosome research has gained significant attention in recent years, with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease being the most extensively investigated disorders. (Cui et al., Reference Cui, Shao, Li, Qiao, Lin and Guan2025). In Parkinson’s disease, exosomal biomarkers include proteins like α-synuclein, along with regulatory miRNAs such as miR-153, miR-409-3p and miR-10a-5p (Gui et al., Reference Gui, Liu, Zhang, Lv and Hu2015; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Wang, Zhao, Feng, Han, Dong, Cui and Tieu2020). For diagnostic purposes, in Alzheimer’s disease, exosome-based biomarker research focuses on proteins such as amyloid β42 (Aβ42), total tau (T-tau) and phosphorylated tau (P-T181), as well as miRNAs including miR-125b-5p, miR-451a and miR-605-5p (McKeever et al., Reference McKeever, Schneider, Taghdiri, Weichert, Multani, Brown, Boxer, Karydas, Miller, Robertson and Tartaglia2018, Jia et al., Reference Jia, Qiu, Zhang, Chu, Du, Zhang, Zhou, Liang, Shi, Wang, Qin, Wang, Li, Wang, Li, Shen, Wei and Jia2019. In the context of therapeutic applications for Alzheimer’s disease, the intracerebral infusion of neuronal exosomes has been shown to reduce amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation in amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mouse models, suggesting a potential role for exosome mediated Aβ clearance (Yuyama et al., Reference Yuyama, Sun, Usuki, Sakai, Hanamatsu, Mioka, Kimura, Okada, Tahara, Furukawa, Fujitani, Shinohara and Igarashi2015). The transfer of toxic proteins via exosomes has been proposed as a mechanism contributing to neurotoxicity in conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, raising questions about their involvement in ASD (Padmakumar et al., Reference Padmakumar, Van Raes, Van Geet and Freson2019). A study demonstrated that miR-17 derived from neural EVs in the blood may serve as a potential biomarker for subthreshold depression (Mizohata et al., Reference Mizohata, Toda, Koga, Saito, Fujita, Kobayashi, Hatakeyama and Morimoto2021). Also, when neuronal exosomes enriched with miR-124-3p were administered in mouse models of spinal cord injury, they promoted functional recovery by suppressing the activation of microglia and astrocytes (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Gong, Ge, Lv, Huang, Feng, Zhou, Rong, Wang, Ji, Chen, Zhao, Fan, Liu and Cai2020).

Moreover, the search for biomarkers in ASD has led researchers to explore various avenues, including blood platelet research, metabolomic profiling and serum protein levels (Padmakumar et al., Reference Padmakumar, Van Raes, Van Geet and Freson2019; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Xu, Li, Liu, Chen, Lu and Xia2020; Eraslan et al., Reference Eraslan, Durukan, Bodur and Demircan Tulaci2021). These studies aim to identify specific biological markers associated with ASD that could aid in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment monitoring. Understanding the molecular alterations associated with ASD through biomarker research is crucial for advancing personalised medicine approaches in the management of individuals with ASD (Eraslan et al., Reference Eraslan, Durukan, Bodur and Demircan Tulaci2021). Recent investigations have explored the use of stem cell derived exosomes in ASD, suggesting that exosomes may hold promise in the context of this disorder (Alessio et al., Reference Alessio, Brigida, Peluso, Antonucci, Galderisi and Siniscalco2020). The brain specific delivery of human umbilical cord MSC exosomes has shown potential in alleviating autism related phenotypes, providing a new direction for the treatment of mental development disorders. Stem cell derived exosomes have been proposed as potential therapeutic agents for ASD, offering a novel approach to addressing the core symptoms and associated phenotypes of the disorder (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Xu, Li, Liu, Chen, Lu and Xia2020).

In conclusion, exosome studies in ASD represent a burgeoning field with significant implications for understanding the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of this complex neurodevelopmental disorder. Research on exosomes may lead to finding biomarkers and opening new avenues for targeted interventions and personalised medicine approaches in the management of individuals with ASD.

Methods

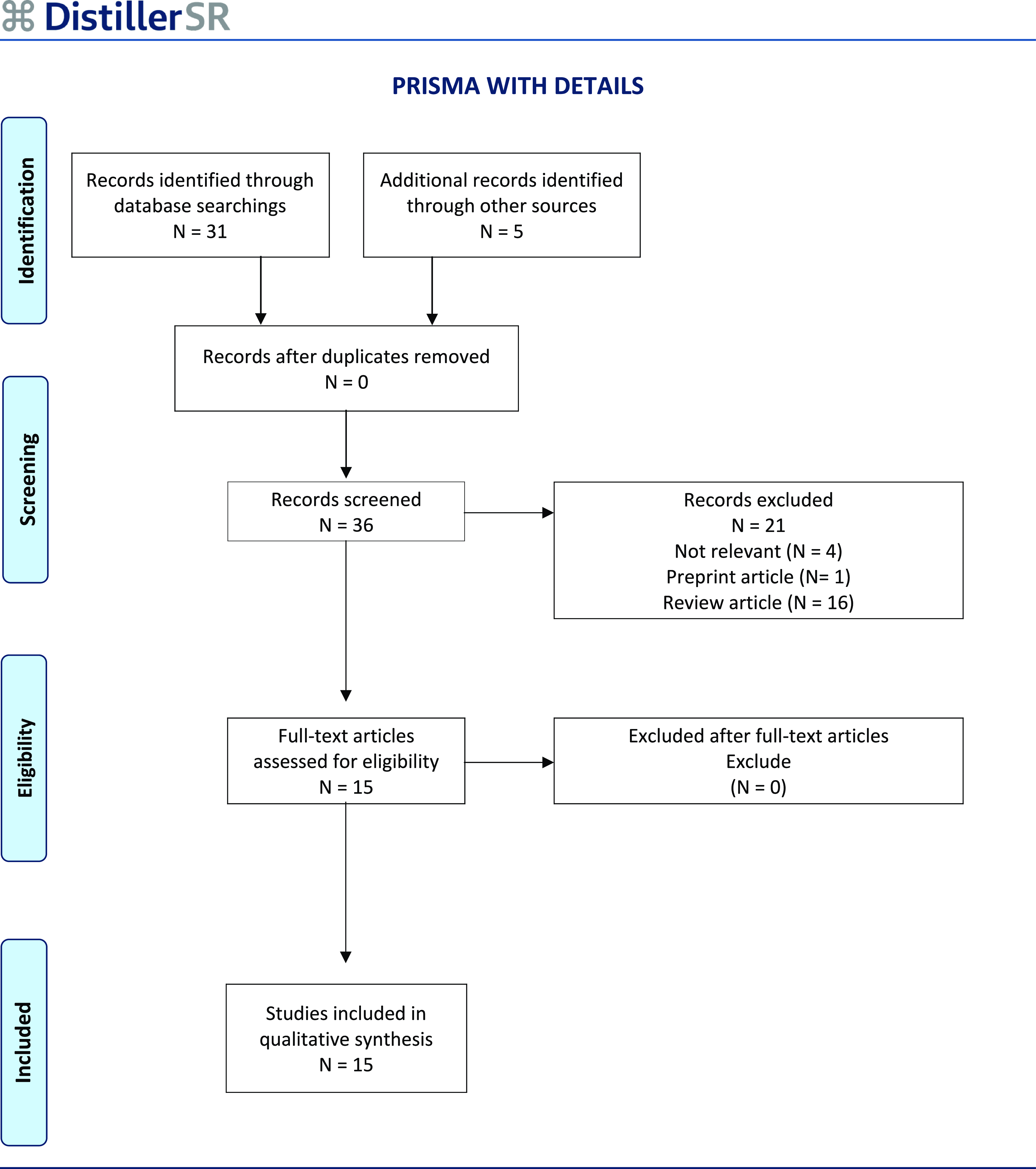

The study adhered to The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for screening, selection, data extraction and acquisition (Fig. 1) (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021). This review was conducted to investigate the studies held in this new research field by searching PubMed database with the key words ‘exosomal, exosome, autism spectrum disorder’ up to 2 October 2025. A total of thirty-one publications were identified, of which twenty-one were excluded: sixteen were review articles, one was a preprint focusing on exosomes, and four were deemed irrelevant. Subsequently, an additional search using the terms ‘extracellular vesicles, autism spectrum disorder’ yielded five more articles. In total, fifteen research articles met the PRISMA inclusion criteria. The remaining fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria, comprising human and animal research combined with in vitro experiments. Considering the substantial differences and the number of the included studies, descriptive summaries of the study characteristics and their findings are given and discussed without any statistical analysis.

Figure 1. The methodology for searching and extracting data was aligned with PRISMA guidelines for gathering and analysing data, resulting in a final dataset that included 15 reseach articles.

Results and discussion

Research on exosomes in ASD remains in its early stages, while parallel investigations are being conducted in several other neurological disorders. Exosomal studies, such as those involving stem cell-derived exosomes, offer promising avenues for ASD research and potential therapeutic interventions (Alessio et al., Reference Alessio, Brigida, Peluso, Antonucci, Galderisi and Siniscalco2020, Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Xu, Li, Liu, Chen, Lu and Xia2020). Bioavailability of these vesicles for drug delivery has also been discussed before (Ren et al., Reference Ren, Nie, Zhu and Zhang2022).

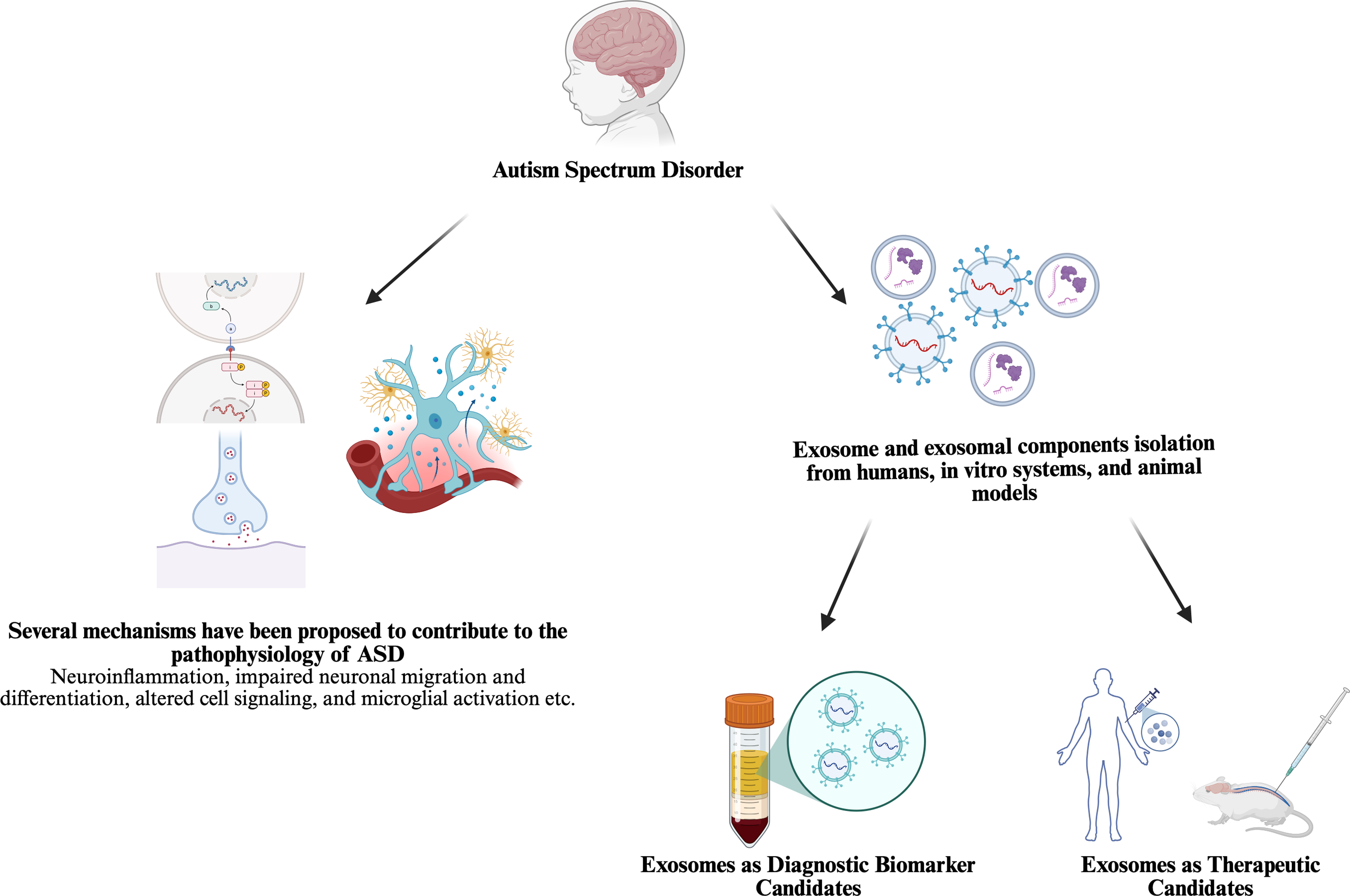

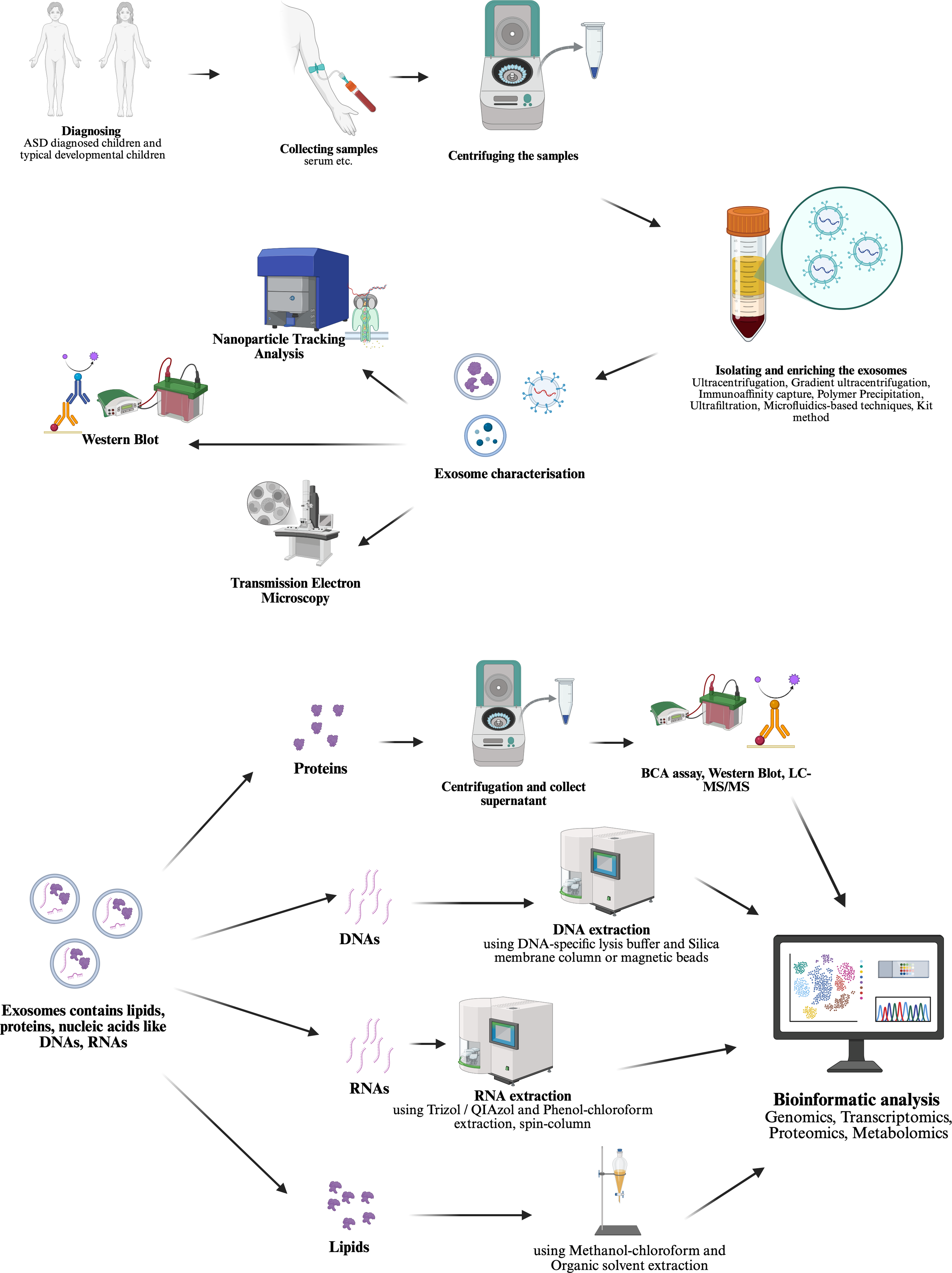

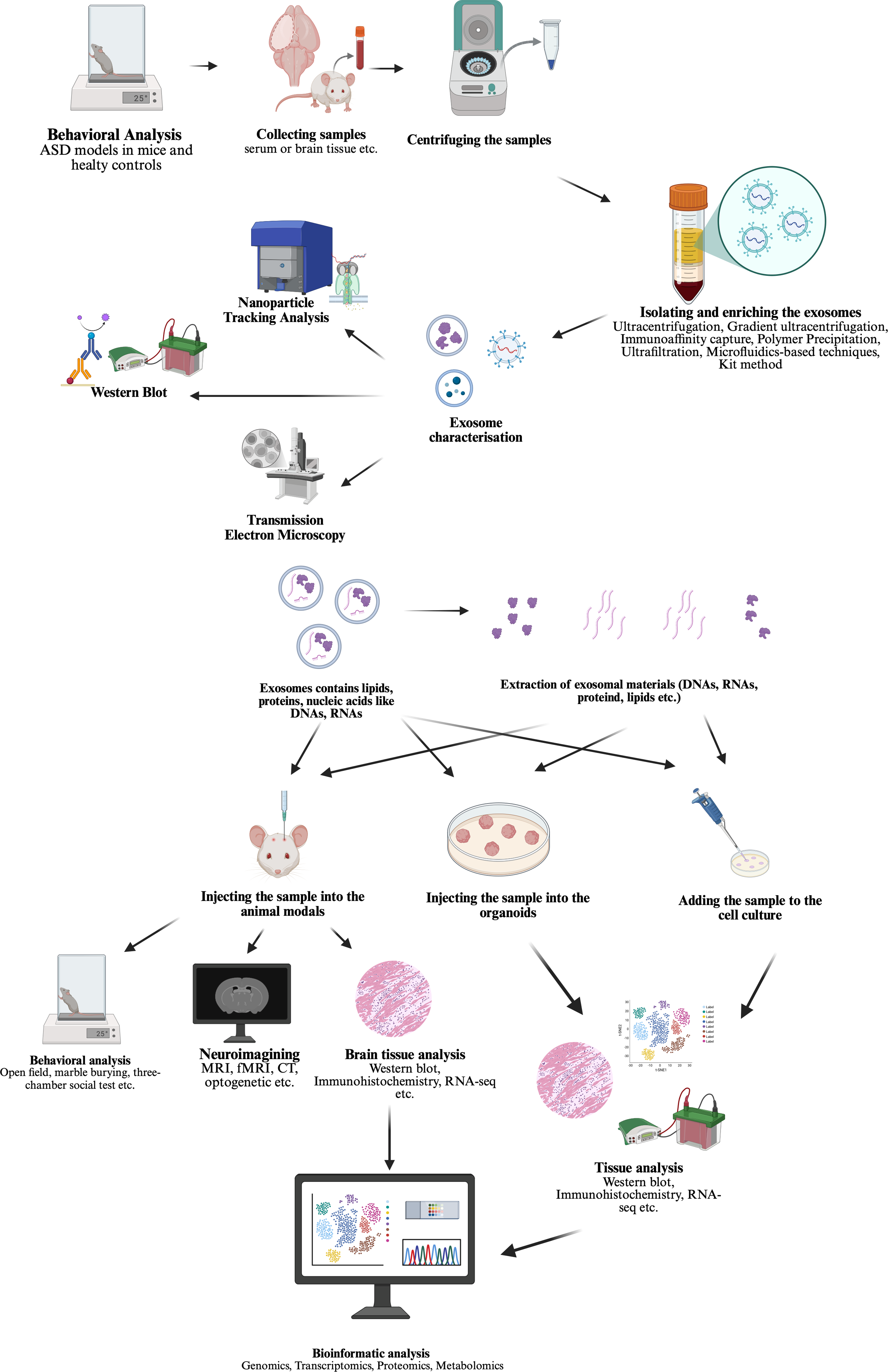

When the studies found in PubMed search, two main approaches stand out for studying exosomes in ASD field. (shown in Fig. 2 created in https://BioRender.com) First, investigating the carriage for identifying a potential biomarker and intervention point based on a prior hypothesis as it is known that EVs are secreted from many cells in the blood and other biological fluids and carry molecules that could influence the function of target cells (shown in Fig. 3 created in https://BioRender.com) (Garcia-Romero et al., Reference Garcia-Romero, Esteban-Rubio, Rackov, Carrión-Navarro, Belda-Iniesta and Ayuso-Sacido2018). Secondly, using MSC derived exosomes transfer for treatment in ASD models in vivo or in vitro as stem cell treatments, even bone marrow transplantation clinical trials have been conducted on humans and showed improvements in symptoms (shown in Fig. 4 created in https://BioRender.com) (Darwish et al., Reference Darwish, El Hajj, Khayat and Alaaeddine2024).

Figure 2. New biomarker and therapeutic candidates in autism spectrum disorder research.

Figure 3. ASD biomarker study methodology steps identified as first approach in this review.

Figure 4. Exosome transfer study methodology steps in ASD literature identified as second approach in this review.

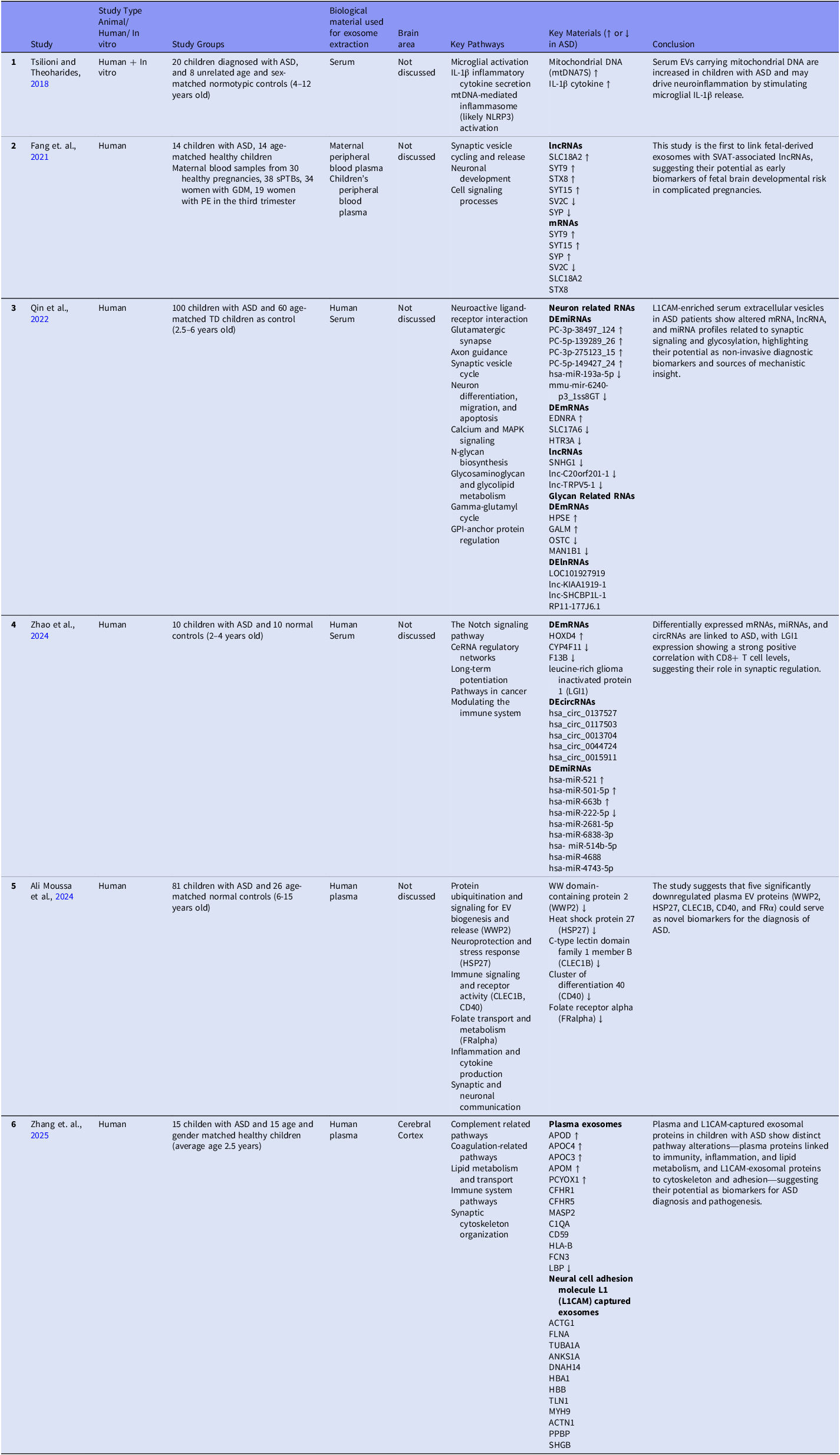

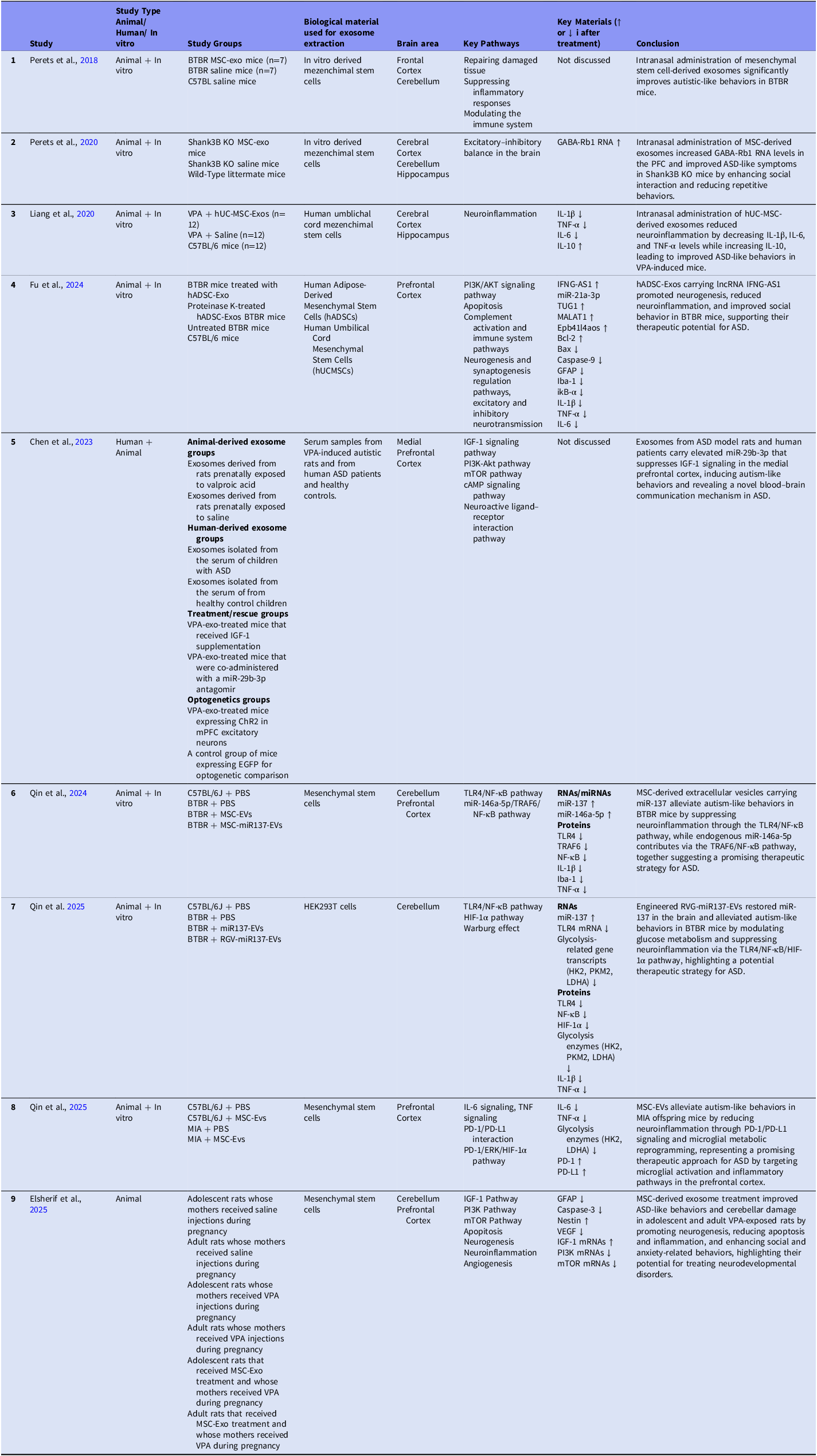

All of the ASD exosome studies evaluated in this review are summarised in Table 1 and Table 2 and discussed according to these two approaches below.

Table 1. ASD exosome studies, first approach

In the Key Materials column of the first table, upward arrows denote materials exhibiting increased levels in ASD, whereas downward arrows indicate decreased levels. Materials that were associated but did not demonstrate a clear directional change are presented without arrows. List Of Abbreviations: ASD, Autism Spectrum Disorder; sPTB, Spontaneous Preterm; GDM, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus; PE, Preeclampsia; SVATs, Autism-Associated Synaptic Vesicle Transcripts.

Table 2. ASD exosome studies, second approach

In the Key Materials column of the second table, upward arrows indicate materials exhibiting elevated levels following exosome treatment in ASD, whereas downward arrows represent decreased levels. Materials that were associated but did not exhibit a definitive directional change are presented without arrows.

List Of Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; hUC-MSC-Exos, human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells exosomes; hADSC-Exos, exosomes derived from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells; VPA, valproic acid; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; MSC-EVs, mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles.

First approach: biomarker studies in autism spectrum disorder research

Blood samples are collected from children with autism and age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Exosomes are then isolated from these samples using established techniques. To validate the isolation, characterisation is performed through nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), Western blotting and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The contents of the isolated exosomes, including proteins, DNA, RNA and lipids, are subjected to genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic analyses. This approach enables the identification of disease-associated molecules through bioinformatic analyses and is aimed at the discovery of potential biomarkers.

First example of the first approach (Fig. 3, Table 1) is the study held by Tsilioni and Theoharides in 2018. EVs were isolated from serum of children with ASD versus normal controls. Increased EV-associated protein was shown in the ASD group compared to controls. EVs from ASD children were also shown to contain more mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which was thought to be a potential trigger for microglia. This was further tested on stimulated mesenchymal cells showing increased secretion of mtDNA (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Angelidou, Alysandratos, Vasiadi, Francis, Asadi, Theoharides, Sideri, Lykouras, Kalogeromitros and Theoharides2010). The group applied their in vitro combination approach for their exosome study and hypothesised that EVs might stimulate inflammatory processes involving microglia. To test this, human microglia simian virus 40 (SV40) culture was stimulated with EVs (1 or 5 μg/mL) obtained from the serum of the patients and IL-1β was measured with enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA). IL-1β was chosen based on their finding of neurotensin stimulating microglia to secrete IL-1β (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Tsilioni, Leeman and Theoharides2016) which had been shown to be increased in the brains of children with ASD (Ashwood et al., Reference Ashwood, Krakowiak, Hertz-Picciotto, Hansen, Pessah and Van de Water2011), and in a mouse model of autism before. (Estes and McAllister, Reference Estes and McAllister2015). EVs isolated from the serum of patients with ASD stimulated with cultured human microglia secreted significantly more of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β as compared to the control. Their study was stated as the first to show increased total EV protein and mtDNA in ASD patients and mtDNA trigger of microglial inflammation process although more studies are needed to draw certain conclusions.

Fang and colleagues conducted a study in 2021 on autism-associated synaptic vesicle transcripts (SVATs) in maternal plasma exosomes, comparing healthy and physiopathologic pregnancies (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Wan, Wen, Wu, Pan, Zhong and Zhong2021). Maternal blood samples collected at different pregnancy weeks from 30 healthy pregnancies, 38 cases of spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB), 34 women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and 19 women with preeclampsia (PE) in the third trimester were included in the study. They identified exosomes derived from pregnant women using anti-PSG1 antibodies. Additionally, anti-NES and anti-L1CAM antibodies showed that some exosomes were neuron-derived, while anti-PLAP antibody positivity indicated placental trophoblast origin. They examined the levels of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and mRNAs in exosomes from maternal plasma samples across weeks 5 to 40 of pregnancy, but these transcripts were not detected between weeks 5 and 10. SLC18A2 lncRNA reached its highest levels in the third trimester and correlated with mRNA levels. SV2C lncRNA peaked at week 18 but did not correlate with mRNA levels. STX8 mRNA and lncRNA levels did not correlate. SYP mRNA and lncRNA peaked at different weeks. SYT9 lncRNA and mRNA had different patterns, but both reached their highest levels after week 33. SYT15 mRNA and lncRNA shared similar expression curves. Except for SYT9, the other five proteins showed dynamic expression trends throughout pregnancy. At different points of pregnancy, different lncRNAs/mRNAs reached their highest peaks, and different pregnancy complications were associated with different lncRNAs/mRNAs, as expected. The study found that SLC18A2 lncRNA and mRNA and SYP lncRNA levels were elevated in sPTB pregnancies, while SV2C lncRNA and mRNA and SYP mRNA were higher in GDM pregnancies compared to healthy pregnancies. In contrast, STX8 lncRNA and mRNA levels were lower in sPTB and PE pregnancies compared to healthy pregnancies. This is the first study to demonstrate a connection between fetal-derived exosomes (EXs) and SVAT-associated lncRNAs. These findings highlight potential links between maternal exosomal RNA expression and fetal neurodevelopmental pathways.

In addition, 14 children with ASD and 14 age-matched healthy children participated in this study. The researchers examined SVAT expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes from children with ASD and compared them with healthy children. ASD children showed differential expression of SVAT-related RNAs. In ASD children, SVAT lncRNAs of SLC18A2, SYT9, STX8 and SYT15, as well as SVAT mRNAs of SYT15, SYT9 and SYP loci, were upregulated. In contrast, SVAT lncRNAs of SV2C and SYP, as well as SVAT mRNA of SV2C, were downregulated in ASD children. Interestingly, 10 out of 12 SVAT-associated mRNAs were not detected in ASD children’s samples, despite being present in healthy children’s samples. This may indicate that lncRNAs and mRNAs have different roles. All in all, this study suggests that SVATs may be associated with pregnancy-related complications and fetal neurological development, underscoring their potential as biomarkers for ASD.

The transcriptome profiles of serum neural cell adhesion molecule L1 (L1CAM)-captured extracellular vesicles (LCEVs) from 60 healthy controls and 100 children with ASD were examined by Qin et al. (Reference Qin, Cao, Zhang, Zhang, Cai, Guo, Wu, Zhao, Li, Ni, Liu, Wang, Chen and Huang2022). Comparing ASD LCEVs to controls, a total of 1418 mRNAs, 1745 lncRNAs and 11 miRNAs showed differential expression. The majority were downregulated. ASD and control groups were found to have differing levels of expression for a number of neuron-related RNAs. In ASD, hsa-miR-193a-5p and mmu-mir-6240-p3_1ss8GT were downregulated, whereas PC-3p-38497_124, PC-5p-139289_26, PC-3p-275123_15 and PC-5p-149427_24 were upregulated among differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs). Notably, the typical developmental group did not have PC-5p-139289_26. While SLC17A6 and HTR3A were downregulated in the ASD group, EDNRA was elevated among differentially expressed mRNAs (DEmRNAs). Children with ASD had downregulated levels of SNHG1, lnc-C20orf201-1 and lnc-TRPV5-1, among other lncRNAs. Differentially expressed genes for glycan related RNAs included OSTC and MAN1B1 were downregulated, and HPSE and GALM were elevated in ASD. Furthermore, differentially expressed lnRNAs (DElnRNAs) with notable expression alterations included RP11-177J6.1, lnc-KIAA1919-1, lnc-SHCBP1L-1 and LOC101927919. With 81.3% of lncRNA–mRNA couples showing positive correlation and frequent downregulation, correlation analysis showed that 107 DElnRNAs were strongly co-expressed with DEmRNAs, indicating coordinated transcriptional control. Key biological pathways such as neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, glutamatergic synapse, axon guidance, synaptic vesicle cycle, neuron differentiation, migration and apoptosis, calcium and MAPK signalling, N-glycan biosynthesis, glycosaminoglycan and glycolipid metabolism, gamma-glutamyl cycle and GPI-anchor protein regulation may be linked to these transcriptomic changes, according to the study. All things considered, the results point to the possibility that transcriptome profiling of serum L1CAM-captured EVs could provide possible biomarkers and assist in identifying the pathogenic processes behind ASD.

In another study of the first approach, Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Zhong, Shen, Cheng, Qing and Liu2024 aimed to contribute to the understanding of ASD pathogenesis and provide more evidence for transcriptomic abnormalities in ASD patients’ exosomes. For this reason, the exosomal miRNA profile in the peripheral blood of children with ASD and healthy controls was investigated. Furthermore, the level of immune cell infiltration depending on gene expression in ASD was evaluated to determine the distribution of immune cell subtypes. RNA from exosomes was isolated and RNA sequencing was performed validating their results with RT-qPCR and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. The GEO database provides the public with circular RNA (circRNA), miRNA, and mRNA data on ASD and is a valuable resource for researchers studying ASD pathogenesis. The competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis, proposed in 2011, describes transcriptional control through miRNA binding sites and miRNA response elements. As proposed by this hypothesis, circRNAs contribute to transcriptional regulation by acting as ‘miRNA sponges’. Although our current understanding of ceRNA networks in ASD remains limited, this study identified 35 DEmRNAs, 63 DEmiRNAs and 494 DEcircRNAs in patients with ASD. Based on these findings, ceRNA regulatory networks comprising 6 DEmRNAs, 14 DEmiRNAs and 86 differentially expressed circular RNAs (DEcircRNAs) were established (Salmena et al., Reference Salmena, Poliseno, Tay, Kats and Pandolfi2011). They explained their different findings from previous research as using data in GEO obtained from both blood and tissues and due to their small sample size for RNA sequencing. One major finding was their correlation analysis indicated that leucine-rich glioma inactivated protein 1 (LGI1) expression was significantly positively correlated with the content of CD8+ T cells which was supported by some other studies. LGI1 is associated with synaptic regulation (Fels et al., Reference Fels, Muñiz-Castrillo, Vogrig, Joubert, Honnorat and Pascual2021). Moreover, synaptic dysfunction is associated with ASD pathogenesis and affects typical autistic behaviour in patients (Delorme et al., Reference Delorme, Ey, Toro, Leboyer, Gillberg and Bourgeron2013; Sztainberg and Zoghbi, Reference Sztainberg and Zoghbi2016). Immunohistochemistry of postmortem brain tissues revealed an increase in CD8+ T cells in ASD (DiStasio et al., Reference DiStasio, Nagakura, Nadler and Anderson2019). These findings may suggest the combined role of LGI1 and CD8+ T cells in ASD pathogenesis further supporting neuroinflammation hypothesis.

Another biomarker study was conducted by Ali Moussa et al., (2024), who investigated whether plasma EVs could serve as biomarkers for ASD. The study included 81 children aged 6–15 years with ASD and 26 age- and sex-matched healthy controls, all residing in Qatar. Proteomic analysis was performed using the Olink proximity extension assay (PEA), which screened 1,196 proteins. The results showed that EV morphology and size were similar between the ASD and control groups, although the number of EV particles was slightly lower in ASD plasma. A significant downregulation was observed in five proteins within ASD EVs, namely WWP2, HSP27, CLEC1B, CD40 and FRalpha. WWP2 is associated with protein ubiquitination and signalling for EV biogenesis and release, HSP27 with neuroprotection and stress response, CLEC1B and CD40 with immune signalling and receptor activity, and FRalpha with folate transport and metabolism. Furthermore, pathways related to inflammation and cytokine production as well as synaptic and neuronal communication were highlighted as important. Machine learning analyses further confirmed that these proteins could distinguish ASD cases with high diagnostic accuracy. The study concludes that a panel of EV proteins may serve as non-invasive biomarkers for ASD, supporting early diagnosis and informing potential therapeutic strategies.

The latest study on exosomes in ASD within this first approach was conducted by Zhang et al., in 2025. The study consisted of 30 children (15 ASD children and 15 healthy controls). There were differences between ASD and control groups in terms of levels of twenty-eight plasma exosomal differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). DEPs were identified using Isobaric Tag for Relative and Absolute Quantitation analysis (iTRAQ analysis). Twenty-three of DEPs were upregulated and five were down regulated in children with ASD. Some of the significant plasma exosomal proteins included APOD, APOC4, APOC3, APOM, PCYOX1, CFHR1, CFHR5, MASP2, C1QA, CD59, HLA-B, FCN3 and GSN and these proteins were associated with complement activation, immunity, inflammation and lipopolysaccharide metabolism and transport. Some of the significant proteins from neural cell adhesion molecule L1 (L1CAM)-captured exosomes (LCEs) included ACTG1, FLNA, TUBA1A, ANKS1A, DNAH14, HBA1, HBB, TLN1, SHBG, MYH9, ACTN1, PPBP, which were associated with cytoskeleton structure, tight junctions, focal adhesion and platelet-associated pathways. In this study, the authors discussed that it remains controversial whether L1CAM-captured exosomal proteins truly represent neuronal-derived brain cargos in plasma, as the neuronal specificity of L1CAM has been questioned in previous studies. They also reported that the protein profiles of plasma-derived EVs and LCEs differed between children with ASD and healthy controls. Also, plasma exosomal DEPs were found associated with many different biological pathways, which might be potential biomarkers for ASD diagnosis and pathogenesis research.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that exosome-based profiling reveals widespread alterations across multiple biomolecular cargos in ASD, including proteins, DNA, RNA and lipids, each providing unique insights into disease biology. Protein-level changes indicate disruptions in pathways such as complement activation, immune signalling and cytoskeletal organisation, while mtDNA suggests potential triggers of microglial activation and neuroinflammatory responses. RNA alterations, including mRNAs, lncRNAs, miRNAs and circRNAs, consistently point to dysregulated networks involved in synaptic transmission, glycosylation, neuronal differentiation and apoptosis, reflecting impaired gene expression regulation during neurodevelopment. Together, these multi-omics findings converge on key themes in ASD pathophysiology: immune dysregulation (altered cytokine signalling, T-cell infiltration, immune receptor changes), inflammation (microglial activation and elevated pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β) and synaptic dysfunction (abnormal regulation of synaptic vesicle proteins, neurotransmitter receptors and structural proteins). Beyond clarifying disease mechanisms, the consistent detection of these exosomal alterations in patients underscores their potential as non-invasive biomarkers, offering opportunities for earlier diagnosis, patient stratification and the identification of novel therapeutic targets by linking molecular cargo changes to clinical phenotypes.

Second approach: treatment studies in autism spectrum disorder research

Studies focuses on evaluating the biological effects of the identified findings. At this stage, tissue samples are collected from autistic individuals, healthy controls or animal models generated by genetic or environmental approaches. Exosomes are isolated from these tissues and characterised using NTA, Western blotting and TEM. Subsequently, the exosomal contents are injected into cell cultures, organoids, or live animals to assess their effects. Tissue analysis, imaging techniques and behavioural tests are employed for this purpose. In this way, the biological effects of the identified molecules can be verified, and their functional roles can be elucidated. As mentioned before, second approach studies (Fig. 4, Table 2) tested the treatment effect and pathophysiology of the exosomes in ASD research.

First of them was held by Perets and his colleagues which involved administering exosomes derived from MSCs (in vitro obtained) intranasally to Black and Tan BRachyury (BTBR) mice to evaluate their impact on autistic-like behaviours (Perets et al., Reference Perets, Hertz, London and Offen2018). The researchers planned the study depending on the promising results of their human bone marrow MSCs transplantation to the lateral ventricles of BTBR mice (Segal-Gavish et al., Reference Segal‐Gavish, Karvat, Barak, Barzilay, Ganz, Edry, Aharony, Offen and Kimchi2016). The primary objective of the study was to assess the effects of this delivery method on ASD-related behaviours and symptoms in the BTBR mice. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-exo) and MSCs were labelled and traced with ex vivo brain imaging. The passage of the MSC-Exo was shown with immunostaining in brain sections. The exosomes were detected within brain cells, whereas MSC were not detected. The effects of MSC on autistic-like symptoms were mainly found related to the MSC-derived exosomes. Behavioural assessments involved tests to analyse social interaction patterns (reciprocal dyadic social interaction test, pup retrieval test), vocalisation frequencies (ultrasonic vocalisation test), and instances of repetitive behaviour (grooming, digging) both before and after the exosome treatment. The researchers showed the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal cell derived exosomes in addressing ASD-related symptoms and behaviours in BTBR mice. They also suggested researchers to identify miRNA profile of the exosomes pointing out potential treatment options.

The study group further tested their intervention through using another genetic ASD model (Shank3B KO mice) (Perets et al., Reference Perets, Oron, Herman, Elliott and Offen2020). They used the same methodology to assess the effect of their intervention and hypothesised an increase in inhibitory tone contributing to the excitation/inhibition balance. Intranasal treatment with MSC-exo improved the social behaviour deficit in multiple paradigms, increased vocalisation and reduced repetitive behaviours. They also captured the accumulation of MSC exosomes in the prefrontal cortex, cerebellum and hippocampus regions, which are related to ASD symptoms. Increase of GABA-Rb1 expression as an indicator of inhibitory response was shown after their treatment in the prefrontal cortex. This study was interpreted as supporting MSC effects via MSC exosomes as they found in their previous study.

In another recent study, Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Xu, Li, Liu, Chen, Lu and Xia2020 showed that intranasal human umbilical cord MSC derived exosomes (hUC-MSC-Exos) treatment ameliorated ASD like symptoms in a VPA induced ASD animal model (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Xu, Li, Liu, Chen, Lu and Xia2020). The study included three groups, each consisting of 12 mice: the VPA + hUC-MSC-Exos group, the VPA + Saline group and the Healthy Control group (C57BL/6 mice). Near infrared (NIR) imaging was used to detect also showed that the intranasal administration delivered DiR-labelled hUC-MSC-Exos into the brain which was consistent with their previous report (Zhuang et al., Reference Zhuang, Xiang, Grizzle, Sun, Zhang, Axtell, Ju, Mu, Zhang, Steinman, Miller and Zhang2011). When MSC-Exo treatment was administered, both rearing behaviour and self-grooming in VPA induced mice were significantly reduced. Moreover, the treatment effectively enhanced social interaction and alleviated anxiety-like behaviours in these mice. To check if their treatment reduced pro-inflammatory state in the ASD model mice brains, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α levels were found significantly decreased following intranasal MSC-exosome treatment in VPA-induced ASD animals. On the other hand, the level of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, was increased. They concluded using MSC and MSC-exosomes as a promising treatment for neurodevelopmental disorders as the exosomes provide a feasible way to transfer into the central nervous system (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Duan, Xu, Li, Liu, Chen, Lu and Xia2020, Ghosh and Pearse, Reference Ghosh and Pearse2024).

A study using exosomes derived from human adipose-derived MSCs (hADSC-Exos) for ASD treatment in BTBR mouse models was conducted by Fu and colleagues in 2024. They compared the lncRNA profiles of hADSC-Exos and hUCMSC-Exos using lncRNA sequencing analysis and found that hADSC-Exos contained more lncRNAs. Next, they used brain organoids to test the effects of hADSC-Exos on neurogenesis. While hADSC-Exos did not significant changes the total number of cells, they increased the proportion of mature neurons and decreased the proportion of neural progenitor cells. Finally, they studied BTBR mice and C57BL/6 mice. BTBR mice were assigned to groups receiving hADSC-Exos or Proteinase K-treated hADSC-Exos (negative control). Proteinase K-treated exosomes were used as negative controls. In the prefrontal cortex of BTBR mice treated with hADSC-Exos, neurogenesis was promoted and the immune microenvironment improved. The researchers conducted four behavioural analyses and observed that untreated BTBR mice exhibited more self-grooming and marble burying, showed decreased novelty preference in the novel object recognition test and showed less interest in social interactions. Treatment with hADSC-Exos improved all these behaviours. They also analysed miRNAs and found that miR-21a-3p was linked to the ASD-like phenotype in BTBR mice. When lnc-IFNG-AS1 in the hADSC-Exos reached the brains of BTBR mice, the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway was activated, apoptosis was prevented and ASD-like symptoms reduced suggesting that the PI3K/AKT signalling might be an important pathway in ASD pathogenesis.

The effects of exosomes were examined by Chen et al. Reference Chen, Xiong, Yao, Gui, Luo, Du and Cheng(2023), who concentrated on exosomal contents taken from rats given VPA on prenatal stage, children with ASD and healthy controls who were matched for age and sex (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiong, Yao, Gui, Luo, Du and Cheng2023). Exosomes isolated from the serum of children with ASD and healthy control children. Mice in the treatment/rescue groups were given exosomes derived from VPA and were also given systemic recombinant insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) supplementation or a miR-29b-3p antagonist. For optogenetic comparison, the control group expressed only EGFP, while the optogenetics groups were mice treated with VPA-exosomes and expressing ChR2 in medial prefrontal cortex excitatory neurons. First, healthy C57BL/6 mice were given injections of exosomes from rats that had been given VPA. In behavioural tests, the treated mice performed worse: in the digging test, marble burying test, repetitive behaviour increased and in the three-chamber social interaction test, social interaction decreased. Following that, RNA sequencing of the mPFC tissue showed changed expression in a number of signalling pathways, such as glutamatergic synapse related processes (GO) and KEGG-based synaptic/neuronal pathways. IGF-1 gene and protein levels are decreased. The reduction in IGF-1 mRNA expression in mice treated with VPA-derived exosomes was further validated by a luciferase reporter assay demonstrating direct targeting of IGF-1 by miR-29b-3p. The behavioural impairments of these mice improved when given recombinant IGF-1 protein, suggesting that IGF-1 signalling plays a part in mediating the effects seen. Furthermore, mice treated with VPA exosomes showed increased levels of miR-29b-3p, indicating that this microRNA may inhibit IGF-1. The behavioural performance enhancements brought about by the administration of a miR-29b-3p antagonist provided evidence in favour of this idea. Furthermore, healthy mice were given exosomes from children with ASD patients and healthy controls. Mice given exosomes from children with ASD patients displayed behavioural abnormalities, whereas mice given control exosomes exhibited no such effects. Activation of ChR2-expressing excitatory neurons in the mPFC also resulted in enhanced performance in the digging test and the three-chamber social interaction test during the optogenetic portion of the study establishing a relationship between the behavioural abnormalities and mPFC in ASD.

Three studies conducted by Qin and colleagues on exosomes and ASD during 2024–2025, from Harbin Medical University, China, will also be discussed here. The first of these studies, by Qin et al. Reference Qin, Shan, Xing, Jiang, Li, Fan, Zeng, Ma, Zheng, Wang, Wang, Liu, Liang, Wu and Liang(2024), explored the therapeutic potential of intranasally administered MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) and miR-137 in a BTBR mouse model of ASD. The mice were divided into four groups and received intranasal administration of MSC-EVs, MSC-miR137-EVs or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for one week. The results demonstrated that MSC-EVs enriched with miR-137 improved cognitive deficits in spatial and directional learning and memory in BTBR mice. Moreover, both MSC-EVs enriched with miR-137 and MSC-EVs alone enhanced social abilities in BTBR mice. They associated the improvements with the suppression of microglial activation and neuroinflammation through the TLR4/NF-κB signalling pathway. Also, endogenous miR-146a-5p within MSC-EVs further reduced inflammation via the TRAF6/NF-κB pathway. Notably, the study emphasised the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex as key brain regions in ASD pathology, with particular focus on the cerebellum, which distinguishes this work from earlier studies. The findings suggest that MSC-EV–mediated delivery of miRNAs, especially miR-137 and miR-146a-5p, represents a promising therapeutic strategy for ASD.

The second study is closely related to the first. Qin et al., Reference Qin, Fan, Zeng, Zheng, Wang, Li, Jiang, Wang, Liu, Liang, Wu and Liang2025 investigated the role of miR-137 in ASD and found that miR-137 levels were reduced in the blood of ASD patients and in the cerebellum of BTBR mice. To restore miR-137, the researchers engineered RVG-modified extracellular vesicles (RVG-miR137-EVs) capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier and delivering miR-137 directly to the brain. The mice were divided into four groups: BTBR + PBS, BTBR + miR-137-EVs, BTBR + RVG-miR-137-EVs and C57BL/6J + PBS. To assess the effects of RVG-EV-mediated miR-137 on autism-like behaviours, BTBR mice received intravenous miR-137-EVs, RVG-miR-137-EVs, or PBS for one week, while C57BL/6J mice served as controls. Cerebellar tissue was collected to evaluate in vivo biodistribution by qPCR. Additional experiments tested the role of TLR4 using TAK-242 and examined glycolysis inhibition with 2-DG, both administered intraperitoneally in BTBR mice, while C57BL/6J mice received PBS as controls. Treatment with RVG-miR137-EVs alleviated autism-like behaviours in BTBR mice by suppressing neuroinflammation via the TLR4/NF-κB pathway, reducing glycolysis and lactate production through HIF-1α downregulation and correcting microglial overactivation. Overall, the study provides proof of concept that restoring miR-137 using engineered EVs can modulate glucose metabolism and neuroinflammation, offering a potential therapeutic strategy for ASD.

The third study by Qin et al., Reference Qin, Fan, Zeng, Zheng, Wang, Li, Jiang, Wang, Liu, Liang, Wu and Liang2025 investigated whether MSC-EVs could alleviate autism-like behaviours in a maternal immune activation (MIA) mouse model. Pregnant C57BL/6J mice received poly(I:C) injections to induce autism-like phenotypes in their offspring. The mice were divided into four groups: C57BL/6J + PBS, C57BL/6J + MSC-EVs, MIA + PBS and MIA + MSC-EVs. The results showed that MIA offspring developed social deficits, anxiety-like behaviours, repetitive behaviours and cognitive impairments, accompanied by increased neuroinflammation and microglial activation in the prefrontal cortex. MSC-EVs, characterised by high programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, or PBS were intranasally administered to both MIA and C57BL/6J mice for one week. Treatment significantly improved behavioural deficits, reduced IL-6 and TNF-α levels, suppressed microglial activation and upregulated PD-L1 while counteracting elevated programmed death receptor 1(PD-1) expression in the brain, via the PD-1/ERK/HIF-1α pathway. Bioinformatic analyses of human ASD datasets further supported these findings, revealing inflammatory pathway activation and microglial dysregulation. In conclusion, MSC-EVs ameliorated autism-like phenotypes by modulating microglial immune responses and glucose metabolism through the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, suggesting a novel therapeutic strategy for ASD.

The last study from the second approach is by Elsherif and colleagues, who investigated the therapeutic effects of MSC-Exos in VPA-induced rats, with a particular focus on their neuroprotective properties (Elsherif et al., Reference Elsherif, Mm Abdel-Hafez, Hussein, Sabry, Abdelzaher and Bayoumy2025). They compared VPA induced rats with and without MSC-Exo treatment using behavioural, histological and molecular analyses. The cerebellar structure of VPA + rats was deformed compared to the control group, and treatment with MSC-Exos reduced this structural deformity. The ultrastructure was damaged in the VPA + groups but improved following Exo treatment. qRT-PCR was used to analyse the mRNA levels of IGF-1, PI3K and mTOR. IGF-1 levels were higher in the VPA + Exo group compared to the VPA + group in both adolescents and adults. In contrast, PI3K and mTOR levels were lower in the VPA + Exo group compared to the VPA + group in both adolescents and adults. Additionally, PI3K and mTOR levels in the adult VPA + group were higher than in the adolescent VPA + group. In the VPA + group glial cells, apoptotic neurons, vascular endothelial growth factor is increased and after Exo treatment these cells are decreased while neural stem cells increased. Social interaction in the adult VPA + Exo group was similar to the adult control group and better than in the adult VPA + group. Additionally, self-grooming was lower in the adult VPA + Exo group than in the adult VPA + group, similar to levels in the adult control group. The adult VPA + group locomotor, exploratory and anxiety-like behaviours are increased than the adult VPA + Exo and adult control groups. When the adolescent groups were assessed by the three-chamber assay and the open-field test, there was no significant distinction. Across all groups, the Morris water maze (MWM) test did not show any discernible difference. Overall, when assessing all the results regarding cerebellar structure and behavioural changes, MSC-Exo treatment appears to be a promising therapeutic option for ASD in the future.

The second research approach in exosome studies on ASD focuses on testing their biological and therapeutic effects rather than only identifying biomarkers. Across different ASD models (BTBR, Shank3, VPA-induced, and maternal immune activation mice), intranasally administered exosomes, primarily derived from MSCs, were shown to cross into the brain and accumulate in ASD-related regions such as the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum. These treatments consistently improved ASD-like behaviours by enhancing social interaction and communication, reducing repetitive and anxiety-like behaviours, and restoring excitation/inhibition balance. At the molecular level, exosomes reduced neuroinflammation by lowering pro-inflammatory cytokines and regulating microglial activity through TLR4/NF-κB, TRAF6/NF-κB and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways; promoted neuronal survival and maturation via the PI3K/AKT pathway; and modulated synaptic processes linked to glutamatergic and GABAergic signalling. Moreover, specific exosomal miRNAs and lncRNAs were identified as key regulators of these effects. Collectively, the findings highlight exosomes as natural nanocarriers capable of reshaping immune responses, supporting neuroprotection, and reversing behavioural deficits, offering a promising and minimally invasive therapeutic strategy for ASD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, behavioural observations, screening instruments, and diagnostic criteria are the mainstays of today’s ASD diagnosis. Furthermore, rather than addressing the fundamental characteristics of ASD or providing a permanent cure, present treatments only address specific symptoms. Exosome-based methods, which can be obtained from a variety of sources and cell types, may provide new insights into the causes, symptoms, and treatment of ASD. The exosomal content differs between healthy controls and individuals with ASD or mice exhibiting ASD-like behaviours.

However, a major limitation of current exosomal biomarker research is that no single, definitive molecule has yet been consistently identified. Different studies highlight different molecules, but a specific and reproducible biomarker has not been established. This not only complicates direct translation into clinical practice but also suggests that instead of focusing on one universal marker, multiple molecules may need to be considered in order to tailor more personalised and individualised treatment approaches.

Despite these challenges, the field remains highly promising. When exosomes from healthy sources were administered to ASD-like mice, significant improvements were observed in multiple behavioural domains. Exosomal biomarker studies are vital in ASD research as they provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of the disorder, aid in early detection, and offer potential targets for therapeutic interventions. By identifying reliable biomarkers, researchers can enhance diagnostic accuracy, stratify patient subgroups, and predict treatment responses, ultimately improving outcomes for individuals with ASD.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

The document was conceptualised in collaboration with DÜ and ASÖ. The literature review and manuscript writing were completed by all writers. The final text was reviewed and approved by all authors.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.