In line with several other countries, Denmark increasingly faces health problems induced by unhealthy diets, including overweight, obesity and a number of associated co-morbidities( 1 ). There is an increasing awareness of the need for public regulations to reverse this trend. One interpretation of the trend is that consumers’ incentives to consume a healthy diet are too weak, because part of the costs arising from unhealthy diets is borne by others (e.g. public health-care system, employers, etc.) and hence considered external costs that are not taken into consideration in consumers’ decision making, leading to loss of social welfare. Taxation of an unhealthy food is expected to increase the consumer price of this food, thus internalizing the external costs into consumers’ decisions and providing an incentive for consumers to buy less of it. Furthermore, revenues generated from such a tax can be used for financing public expenditures or reducing other taxes.

Recently, some countries have adopted the approach of introducing new taxes on foods or beverages that are considered unhealthy. In France, a tax on sweetened non-alcoholic beverages was introduced in 2011( Reference Villanueva 2 ); in Hungary taxes on different ready-to-eat foods (candies, soft drinks, energy drinks, savoury snacks and seasonings) with specified nutritional characteristics were also introduced in 2011( Reference Villanueva 2 , Reference Holt 3 ); Finland in 2011 reintroduced taxes on sweets which had been abolished since 1999; Mexico introduced a tax on soft drinks and junk food in January 2014( Reference Boseley 4 ); and more countries are considering the use of tax instruments in health promotion policies( 5 ). In Denmark, a tax on saturated fat in food products was introduced in October 2011, as a supplement to existing taxation on sugar, chocolate, candy, ice cream and soft drinks. The fat tax in Denmark distinguished itself by targeting a nutrient that occurs naturally in foods, and as such this was the first tax of its kind in the world. For political reasons, the tax was however already repealed by the end of 2012, prior to any evaluation of the tax’s effects( Reference Vallgårda, Holm and Jensen 6 ).

The issue of food taxation as a health-promoting instrument has been considered in several scientific papers (see e.g. review by Mytton et al.( Reference Mytton, Clarke and Rayner 7 )). As the actual use of food taxation in health policy has been very limited, these studies are based on model simulations derived, for example, from econometrically estimated price elasticities. For instance, Smed et al.( Reference Smed, Jensen and Denver 8 ) and Jensen and Smed( Reference Jensen and Smed 9 ) investigated the potential effects of alternative health-related food tax models (including a tax on saturated fat) and found that such taxes can change dietary behaviour, with the potentially largest effects on lower social groups. Chouinard et al.( Reference Chouinard, Davis and LaFrance 10 ) studied the impact of a fat tax on the consumption of dairy products, based on econometrically estimated price elasticities, and found a rather inelastic demand for these products, suggesting a low impact on consumption but a high potential to generate tax revenue. Allais et al.( Reference Allais, Bertail and Nichele 11 ) found that a fat tax had small and ambiguous effects on nutrients purchased by French households. Tiffin and Arnoult( Reference Tiffin and Arnoult 12 ) found that a fat tax will not bring fat intake among UK consumers in line with nutritional recommendations and that potential health impacts of a fat tax will be negligible. Finally, Nordström and Thunström( Reference Nordström and Thunström 13 ) found that a tax on saturated fat would be more efficient in changing consumer behaviour than a tax on all fat, but the impact on consumption would still be minor, assuming politically feasible tax levels. Simulation studies by Mytton et al.( Reference Mytton, Gray and Rayner 14 ) and Nnoaham et al.( Reference Nnoaham, Sacks and Rayner 15 ) found that a fat tax may reduce the intake of saturated fats, but that adverse effects on the intakes of fruit, vegetables and salt outweigh the health-improving effect of a lower saturated fat intake. However, the above simulation studies assumed perfect transmission of the tax into consumer prices and that price elasticities remain unaffected by the tax, which might not be the case in a real-life setting. The authors are aware of only one publication where actual effects of a fat tax have been studied ex post ( Reference Jensen and Smed 16 ).

The objective of the present paper is to investigate whether the Danish tax on saturated fat was effective in reducing consumers’ intake of saturated fat and to study how the tax has triggered different mechanisms in consumption, including the relative importance of these different mechanisms. We investigate these effects by studying the impact on the composition of consumption within three different types of food product containing considerable amounts of saturated fats, namely minced beef and two types of cream (regular cream and sour cream). Together, these three commodity groups represent an estimated 10–15 % of Danes’ total intake of saturated fat, with major contributions from minced beef and regular cream and the lowest share from sour cream( Reference Pedersen, Fagt and Groth 17 ).

The Danish tax on saturated fat

The tax on saturated fat was part of a larger tax reform taking place in Denmark in 2010. The overall aim of this reform was to reduce the marginal income taxation rates for all people actively participating in the labour market and to finance this, among other ways, by increased energy and environmental taxes and increased taxes to reduce adverse health behaviour( 18 ). The so-called health taxes included upward adjustments in existing taxes on sweet products, soft drinks, tobacco and alcohol.

A novelty in the tax reform was the introduction of a tax on saturated fat in foods. The tax was motivated by the fact that the intake level of saturated fat among Danish consumers (14E%, where the unit E% represents percentage of daily energy intake) is above the recommended maximum of 10E%( Reference Pedersen, Fagt and Groth 17 , 19 ). The fat tax was a tax levied on the weight of saturated fat in foods, if the content of saturated fat exceeded 2·3 g/100 g( Reference Smed 20 , 21 ). The threshold of 2·3 g saturated fat per 100 g implied that all kinds of drinking milk were exempt from taxation. The tax was imposed on food manufacturers and food importers, but was expected to be transmitted to consumer prices. Foods determined for export or animal fodder and foods produced at small enterprises (less than approximately 7000€ annual turnover) were exempt from the tax. The tax was set at 16 DKK (2·15 €) per kilogram of saturated fat, which was topped up by value added tax of 25 %. The tax came into force on the 1 October 2011 (and was repealed by the end of 2012 mainly for political reasons( Reference Vallgårda, Holm and Jensen 6 )).

Fatty products, such as butter and margarine, cream, cheese and meats, were the food commodities for which prices were affected the most by the tax on saturated fat, due to their high content of saturated fat. One study( Reference Jensen and Smed 16 ) has investigated the impacts of the saturated fat tax on the consumption of butter, butter blends, margarine and oils, based on household purchase data. That study found that the tax led to significant reductions in the consumption of butter and margarine, but also that the tax induced some structural shifts in different store types’ market shares for these products and on the transmission of the tax into the pricing of the products.

In Denmark, a large share of the meat sold in retail stores is distributed from the manufacturers or importers to the retailers in the form of whole carcasses, and then further processed and cut in the retail stores. Hence, in many cases it was not possible to put the levy directly on individual cuts of meat without considerable extra costs. Instead, animal-specific ‘standardized’ coefficients for content of saturated fat in the meat could be applied when determining the taxable base (i.e. one coefficient for beef, one for pork, etc.). The regulation also allowed for a ‘differentiated’ taxation according to content of saturated fat in specific cuts of meat, based on official food composition tables or specifically documented fat contents, as long as this was done consistently for the whole carcass. As the latter option was administratively more demanding, it was used only for a small share of the Danish meat market.

Because lean meat is generally higher priced than high-fat meat, the standardized saturated fat tax still (from a partial perspective without consideration of supply–demand interactions in the determination of market price impact) implies a larger relative price increase for fatty meat than for lean meat, and hence probably a stronger economic incentive to reduce the consumption of high-fat meat, compared with lean meat. But this incentive could have been even stronger if the true content of saturated fat had been applied to calculate the taxation rate.

Methodology

We aim to analyse the effects of the Danish fat tax on the consumption of three product categories directly affected by the tax: minced beef, sour cream and regular cream products, based on standard economic theory on consumption behaviour. These three product categories were chosen because they represent a substantial share of Danes’ saturated fat intake, have sufficient saturated fat content to be affected by the tax, and contain different varieties that differ only with respect to fat content. It should be noted that the consumption of the three product categories may interact with the consumption of several other food categories, such as other types of meat product, other dairy products, grain-based foods, vegetables, etc., of which the prices of some product types (mainly within meat and dairy) were also affected by the tax on saturated fat, whereas others were not directly affected (but were indirectly affected via supply–demand interactions in the respective markets). In order to incorporate such interaction effects (substitution or complementarity effects), one should ideally estimate a multistage demand model, with interactions between product categories such as minced beef, regular cream, sour cream, other meat categories, other dairy categories, vegetables, etc. at the top stage, and the within-category compositions of the three product categories in the second stage( Reference Edgerton 22 , Reference Carpentier and Guyomard 23 ). However, because data were available only for the three product categories, such an approach was not possible in the present study. Instead, we have utilized price elasticity estimates from the literature to estimate and incorporate these interaction effects on the consumption of the three selected product categories.

The data used in the analysis originate from Coop Danmark, one of the largest food retailer corporations in Denmark (representing a market share of about 40 % of total food retailing in Denmark), spanning five large retail chains: Kvickly, Super Brugsen, Dagli’Brugsen, Fakta and Irma, of which the former four are located all over the country and Irma is located in the eastern part of the country (Sealand). These stores represent all types of stores from high-end supermarkets (Irma) to discount stores (Fakta). The data available for the study cover the period from 1 January 2010 to 31 October 2012 and represent a balanced panel that contains observations from 1293 stores. For each store, monthly records of sales volume and sales revenue, as well as information about specific campaigns are available at barcode level. An alternative to store sales data would be to use household purchase data, which would (in principle) address the consumption effects more directly. On the other hand, the applied retailer sales data enable a high level of detail in terms of, for example, fat percentage, and the accuracy in measurement is considered to be very high. Furthermore, the number of observations in the data set is high.

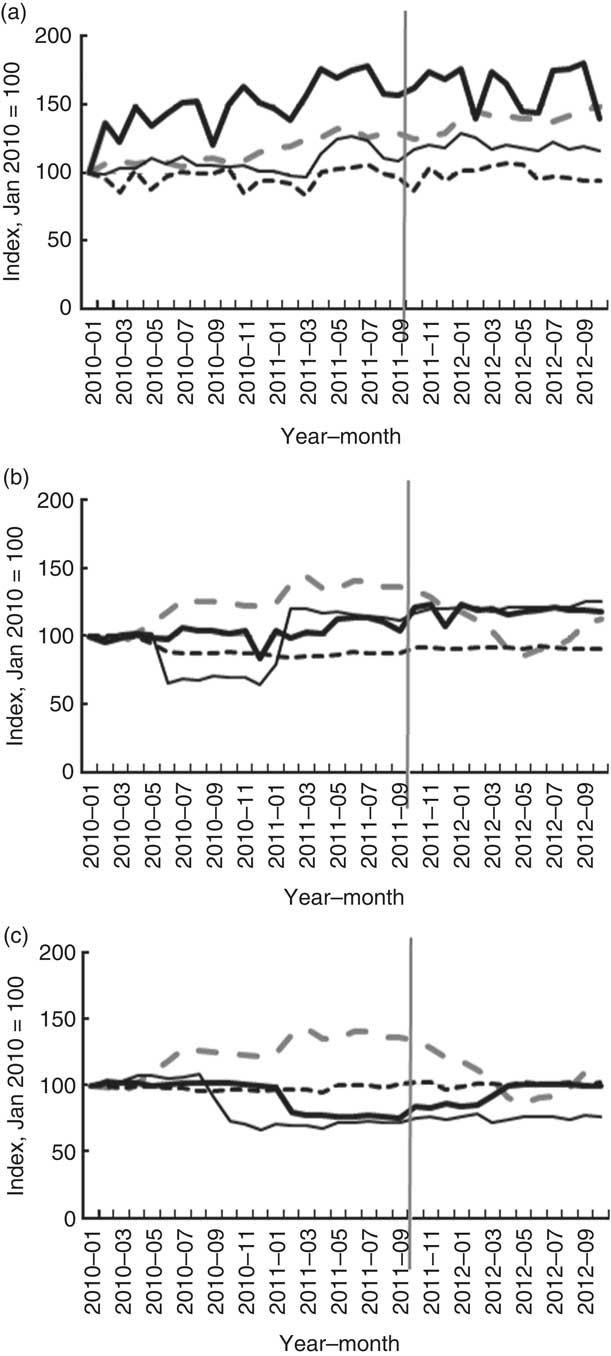

For the econometric analysis, data for minced beef, regular cream and sour cream with different fat contents have been used. Descriptive statistics for these data are given in Table 1. These descriptive statistics show that the prices of minced beef and regular cream tended to be higher after 1 October 2011, when the tax on saturated fat was introduced, whereas no general pattern was seen for the price of sour cream before v. after introduction of the tax. For minced beef, the average price increase seems to have been stronger for medium-fat and weakest for low-fat minced beef; a similar pattern was observed for regular cream; whereas for sour cream, the prices of low- and high-fat varieties remained almost unchanged and the average price of medium-fat sour cream decreased. Figure 1 reveals that this development does not seem to be closely related to the introduction of the tax on saturated fat.

Fig. 1 Developments in the price (![]() , price_ref;

, price_ref; ![]() , price_LoF;

, price_LoF; ![]() , price_MdF;

, price_MdF; ![]() , price_HiF) of (a) minced beef, (b) regular cream and (c) sour cream in Denmark, January 2010–October 2012;

, price_HiF) of (a) minced beef, (b) regular cream and (c) sour cream in Denmark, January 2010–October 2012; ![]() represents introduction of the tax on saturated fat in foods on 1 October 2011 (ref, reference; LoF, low-fat variety; MdF, medium-fat variety; HiF, high-fat variety)

represents introduction of the tax on saturated fat in foods on 1 October 2011 (ref, reference; LoF, low-fat variety; MdF, medium-fat variety; HiF, high-fat variety)

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of variables before and after 1 October 2011, when the Danish tax on saturated fat in foods was introduced

LoF, low-fat variety; MdF, medium-fat variety; HiF, high-fat variety.

According to Table 1, the average purchase of both minced beef and regular cream was higher in the period after the tax was introduced than before, which may come as a surprise, as these products were both taxed. It should however be kept in mind that the values presented in Table 1 are not corrected for seasonal variation, fluctuations in supply conditions, trends, etc., which is done in the econometric analyses below. We should also keep in mind that these values represent sales of minced beef and cream from Coop Danmark’s stores and interpreting these figures as representative of the Danish population should be done with care, as we have not been able to adjust for possible changes in consumers’ selection of shops, etc., which might imply a risk of biased effect estimates.

Looking at Coop Danmark’s customers’ allocation of spending budget within these food categories, represented by ‘budget shares’, Table 1 shows a movement from high-fat varieties towards low- or medium-fat varieties for all three product categories after the tax was introduced (although an increase in the budget share for high-fat sour cream was observed).

In Fig. 1, the price developments of the different product varieties are plotted against a reference price for each product category. The reference price is presumed to represent a relevant price variable that is closely linked to the international markets and hence is assumed not to be influenced by the Danish tax on saturated fat. For minced beef, we use an index for the farm-gate price of cattle for slaughtering( 24 ), and as a reference for cream (both regular and sour) prices, we use the German butter price (CIAL), reflecting the assumption that the alternative use of the cream would be to process it to butter for exports. For minced beef, the prices of medium- and low-fat product varieties tend to follow the price of slaughter cattle, whereas the average price of high-fat minced beef exhibits a completely different pattern.

Econometric model

We assume separability in utility in the sense that the composition of consumption within each of the three product categories is assumed to be independent of prices and consumption within other product categories, and hence that the consumption behaviour can be described by a multistage budgeting model. Due to its flexibility and feasibility properties in terms of estimation and in imposing and testing theoretical properties such as linear homogeneity, adding-up and Slutsky symmetry, we choose the Linearized Almost Ideal Demand System (LAIDS) functional form for each of the three product categories:

$$\eqalignno{ & w_{{it}}^{b} =\alpha _{i}^{b} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {\alpha _{{ji}} \cdot \ln p_{{jt}}^{b} {\plus}\alpha _{{yi}} (\ln y_{t}^{b} {\minus}\ln P_{t}^{b} )} , \cr & \ln P_{t}^{b} =\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {w_{{jt}}^{b} } \cdot \ln p_{{jt}}^{b} . $$

$$\eqalignno{ & w_{{it}}^{b} =\alpha _{i}^{b} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {\alpha _{{ji}} \cdot \ln p_{{jt}}^{b} {\plus}\alpha _{{yi}} (\ln y_{t}^{b} {\minus}\ln P_{t}^{b} )} , \cr & \ln P_{t}^{b} =\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {w_{{jt}}^{b} } \cdot \ln p_{{jt}}^{b} . $$

Commodity i’s expenditure share w i can be described as a linear function of the logarithmic prices, ln p, and the total real consumption expenditure within the commodity category, ln(y/P). Taking departure in sales from retail stores, the sales from store b is an approximation of the ‘representative’ consumer’s expenditure in this store. α are parameters to be estimated.

The tax on saturated fat can be investigated by augmenting the LAIDS model in the following way:

$$\eqalignno{ w_{{it}}^{b} =& \,\alpha _{i}^{b} {\plus}\theta _{i}^{b} \cdot \tau _{t} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {(\alpha _{{ji}} {\plus}\theta _{{ji}} \cdot \tau _{t} )} \cdot \ln (p_{{jt}}^{b} {\plus}\beta _{{jt}} \cdot \phi _{j} \cdot \tau _{i} ) \cr & {\plus}(\alpha _{{yi}} {\plus}\theta _{{yi}} \cdot \tau _{t} ) \cdot \ln ({{y_{t}^{b} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{y_{t}^{b} } {P_{t}^{b} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {P_{t}^{b} }}). $$

$$\eqalignno{ w_{{it}}^{b} =& \,\alpha _{i}^{b} {\plus}\theta _{i}^{b} \cdot \tau _{t} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {(\alpha _{{ji}} {\plus}\theta _{{ji}} \cdot \tau _{t} )} \cdot \ln (p_{{jt}}^{b} {\plus}\beta _{{jt}} \cdot \phi _{j} \cdot \tau _{i} ) \cr & {\plus}(\alpha _{{yi}} {\plus}\theta _{{yi}} \cdot \tau _{t} ) \cdot \ln ({{y_{t}^{b} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{y_{t}^{b} } {P_{t}^{b} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {P_{t}^{b} }}). $$

Introducing the saturated fat tax (the dummy variable e=1 from 1 October 2011 and onwards, otherwise e=0) affects the price of product j, depending on the product’s content of saturated fat, ϕ j , and the extent to which the store passes the tax on to the consumer price, represented by the parameter β, which might be expected to be close to unity( Reference Jensen and Smed 16 ). The price change will in turn affect the demand, represented by the price effect parameter α ij . But to the extent that introduction of the tax affects consumers’ demand behaviour more directly, the model also accounts for three effects: (i) a modification of the price’s effect on consumption, given by the parameter θ ji ; (ii) a modification of the income (or budget) effect, represented by the parameter θ yi ; as well as (iii) a general shift in demand level (intercept term), represented by the parameter θ i . These parameters are quantified by means of econometric analyses.

From the LAIDS model, we can derive expressions for conditional price elasticities, ε

ji

, evaluated at the mean budget shares,

![]() $\left( {\bar{w}_{i} ,\bar{w}_{j} } \right)$

:

$\left( {\bar{w}_{i} ,\bar{w}_{j} } \right)$

:

$$\eqalignno{ {\varepsilon}_{{ji}} = & {{\partial q_{i} } \over {\partial p_{j} }} \cdot {{p_{j} } \over {q_{i} }} \cr = & {{(\alpha _{{ji}} {\plus}\theta _{{ji}} \cdot \tau _{i} ){\minus}(\alpha _{{yi}} {\plus}\theta _{{yi}} \cdot \tau ) \cdot \bar{w}_{j} } \over {\bar{w}_{i} }}{\minus}\delta _{{ij}} , $$

$$\eqalignno{ {\varepsilon}_{{ji}} = & {{\partial q_{i} } \over {\partial p_{j} }} \cdot {{p_{j} } \over {q_{i} }} \cr = & {{(\alpha _{{ji}} {\plus}\theta _{{ji}} \cdot \tau _{i} ){\minus}(\alpha _{{yi}} {\plus}\theta _{{yi}} \cdot \tau ) \cdot \bar{w}_{j} } \over {\bar{w}_{i} }}{\minus}\delta _{{ij}} , $$

where δ ij is the Kronecker delta (=1 for i=j;=0 for i≠j). These price elasticities are conditional on an unchanged total budget for the product category (e.g. minced beef) as a whole.

If the θ ji or θ yi parameters differ from zero, the introduction of the tax influences the price elasticities; that is, either increases or decreases the consumer sensitivity to price changes. This implies that we can decompose the conditional effect of the tax on consumption of commodity i into two components: (i) a price change component given by the expression,

and (ii) a component originating from the changes in elasticities driven by the θ ji and θ yi parameters,

$$\eqalignno{ & {{\partial \left( {{{q_{i}^{1} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{q_{i}^{1} } {q_{i}^{0} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {q_{i}^{0} }}} \right)} \over {\partial {\varepsilon}_{{ij}} }}=\ln \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right) \cdot \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right)^{{{\varepsilon}_{{ij}}^{0} }} \cr\Rightarrow\left. {\Delta \left( {{{q_{i}^{1} } \over {q_{i}^{0} }}} \right)} \right|_{{{\mathop{\rm elast}\nolimits} }} =\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {\ln \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right) \cdot \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right)^{{{\varepsilon}_{{ij}}^{0} }} \cdot \left( {{\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{1} {\minus}{\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{0} } \right)} . $$

$$\eqalignno{ & {{\partial \left( {{{q_{i}^{1} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{q_{i}^{1} } {q_{i}^{0} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {q_{i}^{0} }}} \right)} \over {\partial {\varepsilon}_{{ij}} }}=\ln \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right) \cdot \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right)^{{{\varepsilon}_{{ij}}^{0} }} \cr\Rightarrow\left. {\Delta \left( {{{q_{i}^{1} } \over {q_{i}^{0} }}} \right)} \right|_{{{\mathop{\rm elast}\nolimits} }} =\mathop{\sum}\limits_j {\ln \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right) \cdot \left( {{{p_{j}^{1} } \over {p_{j}^{0} }}} \right)^{{{\varepsilon}_{{ij}}^{0} }} \cdot \left( {{\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{1} {\minus}{\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{0} } \right)} . $$

The total effect to be derived from the tax can be calculated as the sum of these two terms.

The augmented LAIDS models for demand were estimated as simultaneous systems of three price equations and two budget share equations for the three varieties of each commodity group (due to adding-up, the budget share equation for the high-fat varieties were skipped). Price equations were estimated with the tax dummy, reference prices, season (monthly) dummies and a variable representing temporary price campaigns as explanatory variables. Furthermore, inspired by Jensen and Smed( Reference Jensen and Smed 16 ), a pre-tax dummy (=1 in September 2011) was included to capture possible price campaigns prior to the introduction of the tax and hoarding. The budget share equations of the LAIDS model contained prices, real budget term, season dummies, tax dummy, pre-tax dummy, as well as interactions between prices, real budget and tax dummy. The equations were estimated as fixed-effects models (fixed effect with regard to store), using three-stage least squares (treating prices, budget shares and real budget as endogenous variables) and imposing linear homogeneity and symmetry.

As mentioned earlier, the consumption of different fat varieties of minced beef, regular cream and sour cream are considered elements in a multistage budgeting process in the consumers’ behaviour. The estimated elasticities in equation (3) represent the demand effects conditional on the assumption of an unchanged total budget for the considered commodity category. In order to derivethe corresponding unconditional effects, which take into account the interaction between commodity categories, we use the expression for unconditional uncompensated own-price elasticities derived by Carpentier and Guyomard( Reference Carpentier and Guyomard 23 ) in combination with equation (3) above. Hence, we can determine the difference between the unconditional and conditional price elasticities between goods within commodity aggregate H as:

$$\eqalignno{ {\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{{{\mathop{\rm uncond}\nolimits} }} {\minus}{\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{{\rm cond}} = & \bar{w}_{j} \cdot \left( {{1 \over {\left[ {1{\plus}\left( {{{\alpha _{{yj}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\alpha _{{yj}} } {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right)} \right]}}{\plus}{\varepsilon}_{{HH}} } \right) \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yi}} } \over {\bar{w}_{i} }}} \right) \cr \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yj}} } \over {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right) {\plus} & \bar{w}_{j} \cdot \bar{w}_{H} \cdot \eta _{H} \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yi}} } \over {\bar{w}_{i} }}} \right) \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yj}} } \over {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right) $$

$$\eqalignno{ {\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{{{\mathop{\rm uncond}\nolimits} }} {\minus}{\varepsilon}_{{ji}}^{{\rm cond}} = & \bar{w}_{j} \cdot \left( {{1 \over {\left[ {1{\plus}\left( {{{\alpha _{{yj}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\alpha _{{yj}} } {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right)} \right]}}{\plus}{\varepsilon}_{{HH}} } \right) \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yi}} } \over {\bar{w}_{i} }}} \right) \cr \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yj}} } \over {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right) {\plus} & \bar{w}_{j} \cdot \bar{w}_{H} \cdot \eta _{H} \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yi}} } \over {\bar{w}_{i} }}} \right) \cdot \left( {1{\plus}{{\alpha _{{yj}} } \over {\bar{w}_{j} }}} \right) $$

for given price elasticity ε

HH

, income elasticity η

H

and share of overall budget

![]() $\bar{w}_{H} $

for aggregate commodity group H. Using this expression, we can derive the following term for the difference between unconditional and conditional price elasticities:

$\bar{w}_{H} $

for aggregate commodity group H. Using this expression, we can derive the following term for the difference between unconditional and conditional price elasticities:

Estimates for ε HH and η H were obtained from a previous Danish study( Reference Jensen and Smed 9 ), which found own-price elasticities for beef and ‘other milk’ (which is here assumed to represent regular and sour cream) of −0·362 and −0·424, respectively, and income elasticities of 0·220 and 0·241. Furthermore, minced beef, regular cream and sour cream’s share of the overall food budget were estimated to 5 %, 0·5 % and 0·5 %, respectively.

Results

Table 2 summarizes econometric estimates of the partial influence of the tax dummy on the prices of different varieties of minced beef, regular cream and sour cream, when we control for general market developments and seasonality. More detailed estimation results are displayed in Appendix 1 and the full set of estimated parameters can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Table 2 Estimated effect of the Danish tax on saturated fat in foods on consumer prices

LoF, low-fat variety; MdF, medium-fat variety; HiF, high-fat variety.

*Significant at 5 % level, **significant at 1 % level, ***significant at 0·1 % level.

The estimation results indicate similarities across the three commodity groups, with insignificant or small negative tax effects for low- and medium-fat varieties, and 13–16 % price increases for high-fat varieties. The estimated effects of the tax on prices of high-fat varieties exceed our a priori expectations derived from multiplying the tax rate with the content of saturated fat in the products( 25 ), whereas the estimated effects on low- and medium-fat varieties are obviously smaller than the expected.

Conditional uncompensated price elasticities derived from the estimated LAIDS models are shown in Table 3 (more detailed results are displayed in Appendix 2 and a full set of results can be obtained from the authors upon request). Elasticity estimates are calculated both before and after the introduction of the tax (evaluated around the average of pre- and post-tax budget shares, thus with the coefficients to interaction terms between tax dummy and prices or budget constituting the difference) in order to assess the potential effects of the tax on these price elasticities and hence on the underlying preference parameters of the consumers.

Table 3 Estimated uncompensated price elasticities before and after 1 October 2011, when the Danish tax on saturated fat in foods was introduced

LoF, low-fat variety; MdF, medium-fat variety; HiF, high-fat variety.

Significance denotes the statistical significance of difference in θ ji coefficient, hence a test of significant change in elasticity: *significant at 5 % level, **significant at 1 % level, ***significant at 0·1 % level.

Most estimated elasticities are consistent with a priori expectations, including for example negative signs of own-price elasticities (with high-fat sour cream prior to the fat tax as an exception). For example, the results show that the own-price elasticity of low-fat regular cream was −0·898 before 1 October 2011 and −1·013 after this date. Many cross-price elasticities between different fat varieties of the products were negative, suggesting that real budget effects of price changes dominate substitution effects for these products. Overall, the estimated elasticities did not seem to change very much as a consequence of the tax, although the difference was found to be statistically significant for more than half of the elasticities.

Using equations (4) and (5) above, we can now derive three tax-induced components in the demand response for the different minced beef and cream products: (i) the conditional price effect as a direct consequence of the tax on saturated fat (which can be further decomposed into own- and cross-price effects); (ii) the change in preferences, represented by a change in conditional price elasticities; and (iii) a budget re-allocation effect, represented by the difference between unconditional and conditional price elasticities. These components are presented in Table 4, which shows that the effects of the fat tax on consumption and saturated fat intake become rather complex when we take substitution effects and changes in preferences into account. For example, it is striking that the tax-induced price effects seem to lead to an increase in the consumption of low-fat minced beef, due to substitution of high-fat with low-fat minced beef. Similar effects were found for sour cream, whereas the consumption of all fat levels of regular cream was found to decrease due to the tax due to lower substitutability between fat varieties of regular cream.

Table 4 Decomposition of demand change since 1 October 2011, when the Danish tax on saturated fat in foods was introduced

LoF, low-fat variety; MdF, medium-fat variety; HiF, high-fat variety.

Preference changes, as represented by changes in the price elasticities, tended to imply a shift in the direction of relatively stronger preference for low-fat varieties for all three commodity groups (although the pattern was less clear for minced beef than for the cream products). The differences between unconditional and conditional effects represent re-allocations of the overall food budget, and this effect was generally seen to moderate the reducing effect of the tax-induced price increases – most pronounced for regular cream.

Combining the demand effects with coefficients for saturated fat content in the respective product types( 25 ), we can calculate the effects on saturated fat intake from the three products. As shown in Table 4, the tax has led to a decrease in the intake of saturated fat for minced beef and regular cream, whereas the net effect on intake from sour cream was negligible because an increase in the consumption of low-fat sour cream outweighs the reduction in the consumption of high-fat sour cream.

Discussion

The above econometric analyses suggest that the introduction of a tax on saturated fat in food products in Denmark has had effects on the retail market for beef and cream products, and that it reduced saturated fat intake from minced beef and regular cream by 4–6 % but had no clear effect for sour cream. Taking into consideration that Danes’ average intake of saturated fat exceeds the recommended level by 40 %, these reductions may be considered fairly small from a health perspective, albeit statistically significant. The results however also illustrate that the impacts of the tax have been somewhat complex. Budget effects and substitution effects between product varieties with different contents of saturated fat play an important role, whereas shifts in consumers’ preferences following the introduction of the tax play a minor role. Hence, the present study yields some support for previous simulation analyses suggesting that a fat tax has an effect on consumption( Reference Smed, Jensen and Denver 8 , Reference Jensen and Smed 9 , Reference Mytton, Gray and Rayner 14 , Reference Nnoaham, Sacks and Rayner 15 , Reference Eyles, Ni Mhurchu and Nghiem 26 ). For example, Jensen and Smed( Reference Jensen and Smed 9 ) estimated a 3–4 % decrease in meat consumption as a consequence of a saturated fat tax rate comparable to that of the actual tax in real terms, whereas Smed et al.( Reference Smed, Jensen and Denver 8 ) estimated a 9 % decrease in intake of saturated fat as result of a tax rate of about 8 DKK/kg (in year 2000-price level). Findings in the studies by Mytton et al.( Reference Mytton, Gray and Rayner 14 ) and Nnoaham et al.( Reference Nnoaham, Sacks and Rayner 15 ) regarding effects on saturated fat intake were somewhat in line with our results (whereas more moderate effects were suggested in findings by Tiffin and Arnoult( Reference Tiffin and Arnoult 12 )), but as their studies took the analysis of fat taxes further by estimating likely health impacts of the dietary changes induced by a fat tax, they tend to suggest positive health impacts of lower fat consumption, but also adverse health effects due to substitution effects on the intake of salt and of fruits and vegetables.

The change in preferences represented by the difference in price elasticities before and after the introduction of the saturated fat tax is somewhat in contrast to the normal assumption in economic theory that preferences are independent of prices. Various explanations can be given for these differences in elasticities. One methodological explanation could be that even though preferences may be stable, they need not be well approximated by a constant elasticity framework, which might suggest that a functional form with greater flexibility than the LAIDS form (such as the Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System, or QAIDS) might be more appropriate. However, besides such methodological explanations for the differences in elastiticies, there may also be good behavioural and/or psychological explanations. Much of the behavioural economics literature( Reference Just and Payne 27 , Reference Lusk 28 ) points out bounded rationality due, for example, to cognitive limitations of the individuals, which prevents them from taking all possible aspects into consideration in their decision making. The introduction of the saturated fat tax – and the public debate surrounding this introduction – could have increased consumers’ awareness and knowledge of certain product characteristics and hence the way that their preferences are expressed in actual consumption behaviour.

Our analysis is based on a relatively short period after the introduction of the tax (12 months, corrected for seasonality effects) and hence interpretation of these findings from a long-run perspective should be done with some care. On the one hand, hoarding prior to the introduction of the tax may have affected purchases in the beginning of the tax period. On the other hand, economic reasoning might suggest larger behavioural adjustments and reductions in consumption of high-fat products in the longer run, both on the consumer demand side (e.g. because formation of new dietary patterns and habits as a response to a price change takes time) and on the supply side (in terms of e.g. product reformulation towards products with a lower content of saturated fats, changed marketing strategies with more emphasis on lower-taxed products, etc.). So even if the presented short-run results may provide a biased estimate of long-run effects, there is some ambiguity about the direction of such bias. Extending the analysis to include data from the period after the repeal of the tax might provide useful insights as to the robustness of our findings and the identified mechanisms, but unfortunately only data until October 2012 were available for the present study.

For pragmatic reasons, the empirical analysis has focused on the consumption of minced beef, regular cream and sour cream, which represent significant market volumes within a limited number of specific product items. In order to obtain estimates of unconditional effects of the tax on the demand for the three product types, we have combined the econometric estimates with findings from the literature concerning price elasticities at more aggregated product levels. However, a range of other food products, including especially other dairy products and meat products, were also directly affected by the tax on saturated fat. The study by Jensen and Smed( Reference Jensen and Smed 16 ) found that the Danish fat tax had decreased consumers’ purchase of fat in butter, butter blends, margarine and oils by about 8–10 %. But also the prices of a whole range of processed foods, such as ready-meals, bread, pastries, processed foods, snacks, etc., were affected by the tax because they are based upon ingredients that were subject to taxation. As data were available only for the three selected commodity groups, we have not been able to evaluate the detailed interactions with other product categories affected by the saturated fat tax, which is suspected to imply some uncertainty in our approximation of the budget re-allocation effect via the uncompensated price elasticities – especially for minced beef. Previous results however indicate that such substitution effects may be moderate in magnitude( Reference Ni Mhurchu, Eyles and Schilling 29 ). In principle, similar effects might be suspected for the cream product categories, but as the availability of substitutes for regular cream and sour cream is more limited, such substitution effects – and hence the potential bias from ignoring these substitution effects – are also likely to be smaller for these product categories than for minced beef.

We should also mention that the present analysis interprets changes in sales from one (major) retail supplier as changes in consumption, which of course should be done with care because this interpretation hinges on a number of critical assumptions, including that all that is bought is also consumed and that retail chains’ market shares in the considered products remain stable. It has not been possible to investigate these assumptions within the framework of the present analysis, but it would be an issue worthy of further investigation.

Several representatives of political parties and industry lobbies have been making the point that increased food taxation has led to increased cross-border trade and that such trade offsets the direct consumption reduction effect of the tax. Economic theory would suggest a substitution effect between purchases domestically and across the border, if the price of domestically sold products increases, ceteris paribus. Although this may be a valid point for citizens living close to the border, most citizens in Denmark would face considerable transaction costs to go outside the country to buy products containing saturated fats, which would suggest that the extent of such cross-border trade would be limited. Our results may thus represent an upper-end estimate of the tax’s effect on consumers’ saturated fat intake from beef and cream, but the issue of cross-border trade could also be an issue worthy of further investigation in future research.

Conclusion

Based on econometric analysis of sales data from one of the major retailers in the Danish market, we conclude that the Danish introduction of a tax on saturated fat in food in October 2011 had statistically significant effects on the sales of minced beef and cream products. The tax induced substitution of high-fat with low-fat varieties, and the substitution in minced beef consumption took place, even though the tax on beef was not differentiated according to saturated fat content. Hence, we can conclude that the introduction of the saturated fat tax contributed to reducing the intake of saturated fat among Danish consumers by 4–6 % for minced meat and regular cream but the tax had negligible effects on saturated fat intake from sour cream. However, taking into consideration that Danes’ average saturated fat intake exceeds the recommended intake by some 40 %, the tax seems to have reduced this gap only to a limited extent.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: The research reported in this manuscript was part of a large research centre ‘UNIK – Food, Pharma, Fitness’ at the University of Copenhagen. The centre has obtained financial support from the Danish Ministry of Science. The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authorship: J.D.J. participated in the design of the study, undertook statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; S.S. participated in the design of the study, interpretation of results and writing of the manuscript; L.A. participated in the design of the study and interpretation of results; E.N. participated in the design of the study, preparation of data for the analysis and interpretation of results. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Appendix 1 Selected econometric estimation results, price equations

Appendix 2 Selected econometric estimation results, budget share equations