Oral glucocorticoids, a type of corticosteroid, are immunosuppressant and anti-inflammatory agents Reference Judd, Schettler, Brown, Wolkowitz, Sternberg and Bender1 used for a wide range of indications, including autoimmune disorders. Reference Freishtat, Nagaraju, Jusko and Hoffman2 Despite their efficacy, there is concern about adverse neuropsychiatric and behavioural effects. These include acute outcomes such as anxiety attacks, mania, suicidal behaviour and psychotic episodes. Reference Judd, Schettler, Brown, Wolkowitz, Sternberg and Bender1 In support, a large cohort study in primary care data found that glucocorticoid treatment was associated with substantially elevated risks of suicidal behaviour, mania and panic disorder over a period of 3 months, and that a past history of mental health disorders increased the risk of these outcomes. Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3 This and other studies have found that higher doses of glucocorticoids are associated with greater risk of psychiatric and behavioural outcomes, Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3–Reference Dalal, Duh, Gozalo, Robitaille, Albers and Yancey5 and that age is a moderator of these risks. Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3,Reference Laugesen, Farkas, Vestergaard, Jørgensen, Petersen and Sørensen4 Prior studies have found a varying impact of a history of psychiatric disorders. Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3,Reference Smets, Van Deun, Bohyn, van Pesch, Vanopdenbosch and Dive6–Reference Poetker and Reh8

However, there is limited large-scale observational evidence considering a broad set of psychiatric outcomes defined by psychiatric healthcare admissions, which are likely to represent more serious events. Furthermore, we are not aware of any studies that have used self-controlled designs, which account for all measured and unmeasured time-invariant confounding within individuals, including genetic make-up and childhood environment; or of studies that have employed a target trial emulation approach to ensure that a range of common biases are mitigated and that a clear clinical question is formulated. Reference Hernán and Robins9

In this study, we therefore aimed to explore the association between glucocorticoid treatment and psychiatric and suicidal outcomes, as defined by specialist care contacts in a nationally representative data linkage, using two complementary designs. First, we considered all individuals ever dispensed a glucocorticoid (medication-only cohort) and used a self-controlled design to account for within-individual factors that remain stable over time. We stratified these analyses by (a) age, (b) whether individuals had a history of psychiatric diagnoses and (c) receipt of an autoimmune disorder diagnosis. We also considered the impact of treatment duration. Second, we followed individuals from their first diagnosis of an autoimmune or gastrointestinal autoimmune disorder (indication cohorts) and compared psychiatric risks in those who did and did not initiate a glucocorticoid medication, using a target trial emulation approach. These analyses were also stratified by history of psychiatric disorders.

Method

Ethics and consent

Ethical approval was secured from the Stockholm Regional Ethics Committee (Stockholm, Sweden, reference nos 2013/862-31/5 and 2020-06540). The need for informed consent was waived according to Swedish law, on the basis that the research was register based and data were pseudonymised.

Data sources

Information was linked across Swedish national registers using unique personal identification numbers. Reference Ludvigsson, Otterblad-Olausson, Pettersson and Ekbom10 We extracted prescription information from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, where pharmaceuticals dispensed (prescribed and collected) since 2005 are documented; Reference Wettermark, Hammar, MichaelFored, Leimanis, Otterblad Olausson and Bergman11 information on in-patient and specialist out-patient care from the National Patient Register, which has documented this information since 1973 (for in-patient care) and since 2001 (for specialist outpatient care); Reference Ludvigsson, Andersson, Ekbom, Feychting, Kim and Reuterwall12 demographic data from the Total Population Register; Reference Ludvigsson, Almqvist, Bonamy, Ljung, Michaëlsson and Neovius13 and emigration data from the Migration Register. Reference Ludvigsson, Almqvist, Bonamy, Ljung, Michaëlsson and Neovius13 Causes and dates of death were extracted from The Cause of Death Register. Reference Brooke, Talbäck, Hörnblad, Johansson, Ludvigsson and Druid14

Cohort

Medication-only cohort

We identified individuals aged 15–54 years who had collected at least one glucocorticoid prescription (see Measures, below, for details on Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes) in oral form between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2020. We focused on individuals aged <55 years to estimate effects in adults. We excluded individuals who had ever been dispensed a glucocorticoid where the prescription text indicated they had Addison’s disease, given that steroid treatment in these individuals is intended to replace insufficient endogenous production. Follow-up started on either 1 January 2006 or the date of the individual’s 15th birthday, whichever came last; it ended on the date of either first emigration, death, reaching age 55 years or 31 December 2020, whichever occurred first.

Indication cohorts – target trial emulation

As an alternative to the medication-only cohort, we defined indication cohorts in order to emulate two target trials. This allowed us to define clear clinical questions: what is the effect of glucocorticoid treatment initiation following any autoimmune or a gastrointestinal autoimmune disorder diagnosis on psychiatric and suicidal behaviour risks? See Supplementary Table 1 for a description of the target trials and how we emulated them.

We identified two cohorts based on a diagnosis of disorders indicating glucocorticoid treatment – any autoimmune disorders and gastrointestinal autoimmune disorders. See Supplementary Table 2 for the diagnoses considered, defined using ICD-10 codes. 15 We selected individuals who had received a diagnosis of either of these disorders between 1 January 2006 and 30 November 2019, choosing the first recorded diagnosis as index. We then excluded individuals who had been prescribed a glucocorticoid <180 days before they received their diagnosis, to ensure that all included individuals had a washout period from glucocorticoid treatment of at least 180 days. Anyone initiating a glucocorticoid within 28 days of their diagnosis was assigned as an initiator, and anyone who did not as a control. The start of follow-up was the date of glucocorticoid dispensation among initiators. Among controls, the time between diagnosis date and dispensation date in initiators was randomly assigned to define the follow-up start. Reference Lagerberg, Matthews, Zhu, Fazel, Carrero and Chang16 We carried out intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses (see Analyses, below). For intention-to-treat analyses, follow-up ended at 365 days after follow-start. For per-protocol analyses, follow-up ended at 365 days after follow-start unless individuals stopped adhering to their baseline treatment strategy, at which point they were censored.

Measures

Exposure

We considered any glucocorticoid medication licensed for sale in Sweden during the study period. Because we did not have information on individual ATC codes below the second level (H02) for the main cohort, we could not directly select glucocorticoid-only dispensations (H02AB). However, the only medication in the H02 category that is not a glucocorticoid and licensed for sale in Sweden is fludrocortisone (H02AA02), a mineralocorticoid used to treat Addison’s disease and congenital adrenal hyperplasia, both rare conditions. An estimated 1300 Swedish residents have Addison’s disease, 17 and we excluded any individual where their prescription text indicated this disease, although we did not have structured diagnostic information on it. Meanwhile, only 606 individuals born between 1915 and 2011 had congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Reference Gidlöf, Falhammar, Thilén, von Döbeln, Ritzén and Wedell18 For completeness, we carried out sensitivity analyses in a subset of the follow-up (2006–2013), where we were able to restrict to glucocorticoid-only prescriptions (H02AB; see ‘Analyses’ below). We created continuous treatment periods on the assumption that any prescriptions falling within 120 days of each other within an individual belonged to the same treatment period. Reference Lagerberg, Fazel, Molero, Franko, Chen and Hellner19 The treatment period started on the date of the first prescription in the period. For the last or single prescription in a treatment period, 14 days were added to the end to define the date of treatment period end. Reference Lagerberg, Fazel, Molero, Franko, Chen and Hellner19 Continuous treatment periods were considered in the analyses of the medication-only cohort, and in per-protocol analyses in the indication cohorts.

Outcomes

We considered any unplanned specialist psychiatric healthcare contact where diagnosis was made for anxiety (F4), bipolar (F25.0, F30, F31, F34.0), depressive (F32, F33, F34, excluding F34.0, F38, F39) or schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (ICD-10 codes: F2, excluding F25.0). For suicidal behaviour, we considered any unplanned healthcare contact where the diagnosis was self-harm or death by suicide, of either known (X60–84) or unknown (Y10–34) intent. The date of patient admission to care was assumed to be the date of the event.

Covariates

In the medication-only cohort, all analyses were adjusted for age. Between-individual analyses were additionally adjusted for gender. In the indication cohorts, all analyses were adjusted for gender; age; year of follow-up start; highest level of attained education of individual and their parents; highest income category between individual and parents; and diagnoses at baseline (anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, substance use disorder and a history of self-harm). The only variable with missing information was highest attained education between individuals and their parents, where the prevalence of missingness was between 1 and 2% (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Missing values for education were treated as a separate category in the education variable.

Analyses

Medication-only cohort

We used stratified Cox proportional hazards models to estimate within-individual hazard ratios. We compared the hazards of outcomes during treated and untreated periods within the same individual, ensuring that all time-invariant confounding was controlled for. Reference Lichtenstein, Halldner, Zetterqvist, Sjölander, Serlachius and Fazel20,Reference Lu, Sjölander, Cederlöf, D’Onofrio, Almqvist and Larsson21 Analyses were carried out overall and stratified by: gender, age category (15–24, 25–34, 35–44 and 45–54 years) and a history of any of the outcomes at start of follow-up (past psychiatric diagnosis). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis where we excluded any individual ever prescribed an inhaled glucocorticoid (ATC code R03BA). All analyses were adjusted for time-varying age.

To investigate whether there were periods of high or low risk during glucocorticoid treatment, we carried out analyses looking at the outcome in each of the following periods since treatment start: <14, 14–119, 120–364 and >364 days, using any off-treatment period as the reference. We also considered average daily dose of glucocorticoid medication collected during treatment. We calculated this by taking the sum of the amount of medication – expressed as defined daily dose (DDD) 22 – that was dispensed over a treatment period. We then divided cumulative DDD by the length of treatment in days. We classified <0.5 DDD per day as low dose, 0.5–1.5 DDD per day as medium dose and >1.5 DDD per day as high dose. Reference Einarsdottir, Ekman, Molin, Trimpou, Olsson and Johannsson23

We further stratified by diagnosis of an autoimmune or gastrointestinal autoimmune disorder. These diagnoses were defined as being present after the first recorded diagnosis from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2020. To investigate the impact of between-individual confounding in the medication-only cohort, we carried out between-individual analyses using Cox poportional hazards models, which were adjusted for age and gender. We used robust sandwich covariance estimation when calculating confidence intervals to account for correlation of person–time within individuals. Reference Lee, Wei, Amato, Leurgans, Klein and Goel24

Finally, to assess whether our results were impacted by the potential inclusion of non-glucocorticoid corticosteroids, we restricted analyses to the follow-up period 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2013. In these data, we had access to information up to the 5th ATC level (e.g. H02AB01), and were able to ensure that the cohort contained only dispensations of glucocorticoids.

Indication cohorts

We used pooled logistic regression models with product terms between treatment and time Reference Hernán25 to estimate cumulative incidence and hazard ratios for each of the outcomes at 14, 120 and 365 days of follow-up. We accounted for baseline confounders by applying inverse probability weighting (IPW), Reference Hernán, Lanoy, Costagliola and Robins26 and calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) between confounder distributions in initiators and controls before and after weighting. We conducted both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses (Supplementary Table 1). In intention-to-treat analyses, individuals were assumed to have adhered to their assigned baseline treatment throughout follow-up. In per-protocol analyses, we censored individuals when they stopped adhering to the treatment strategy they were assigned at baseline. For initiators, this occurred if the individual terminated their treatment during follow-up; for controls, this occurred if the individual initiated glucocorticoid treatment during follow-up. We estimated time-varying treatment adherence weights using baseline confounders and specialist out- or in-patient healthcare contacts over follow-up. We weighted each 2-week period of follow-up by the product of time-varying and baseline IPW. Weights were stabilised and truncated at the 99th percentile. We used non-parametric bootstraps over 500 samples to estimate 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were run overall, and intention-to-treat analyses were stratified by a history of outcomes at the start of follow-up (past psychiatric diagnosis).

Results

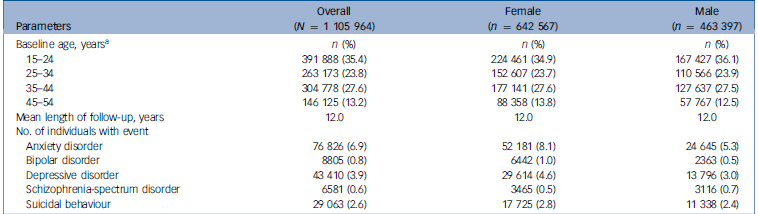

We identified 1 105 964 individuals who had at least one dispensed glucocorticoid prescription between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2020 at age 15–54 years (Table 1). Of those prescribed glucocorticoids, 642 567 (58.1%) were female. Mean length of follow-up was around 12 years in the medication-only cohort. During follow-up, there were unplanned specialist healthcare contacts for anxiety disorder (in 6.9% of the cohort), bipolar disorder (0.8%), depressive disorder (3.9%), schizophrenia-spectrum disorder (0.6%) and suicidal behaviour (2.6%). These proportions were similar between men and women.

Table 1 Characteristics of individuals dispensed a glucocorticoid (medication-only cohort)

a . At start of follow-up.

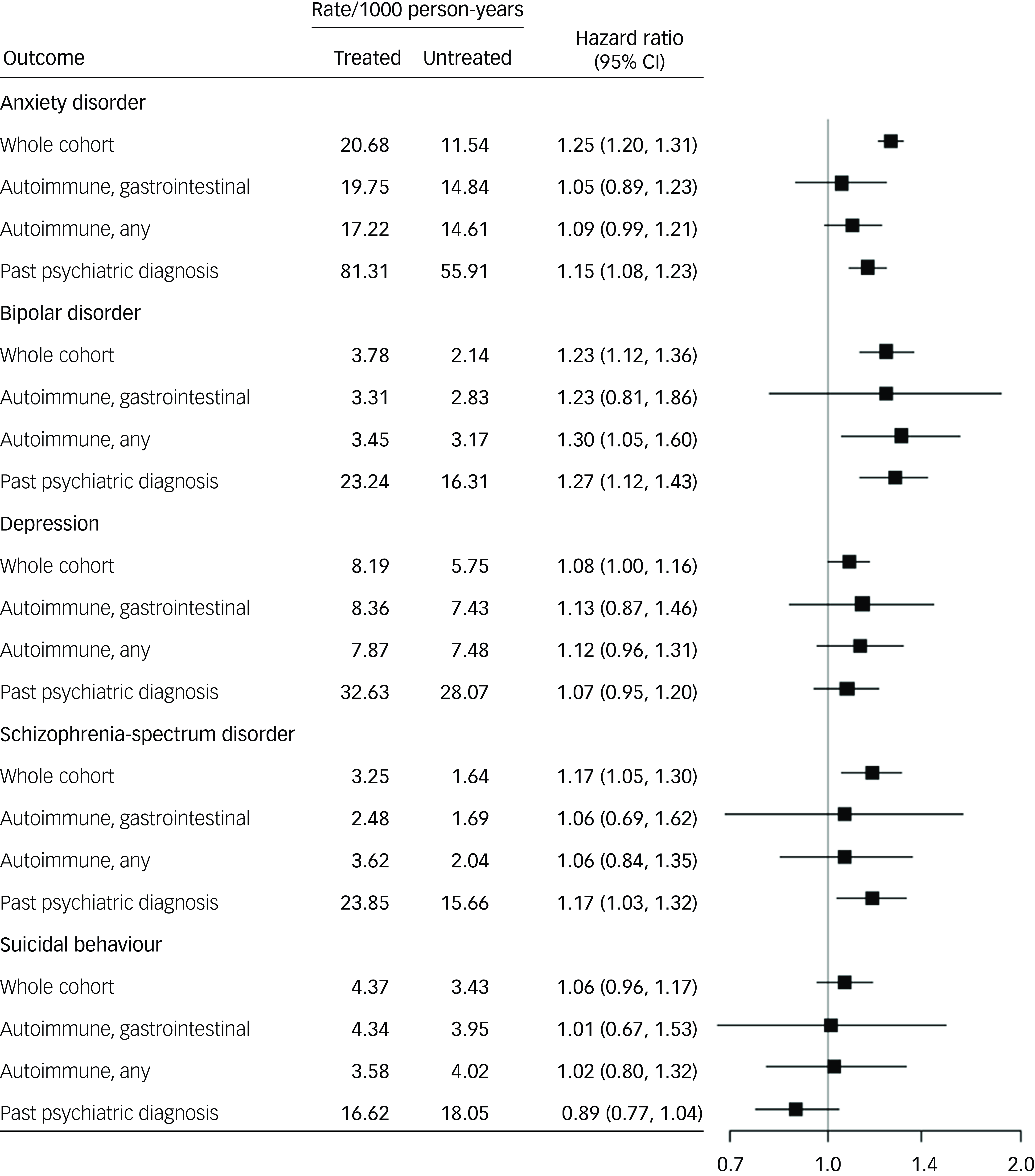

In the medication-only cohort, we found increased hazards for the main psychiatric disorders. Within-individual hazard ratios in the overall cohort ranged between 1.06 and 1.25 (Fig. 1), with no clear differences by gender or age (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). We found no strong evidence for an association with suicidal behaviour in within-individual analyses, either overall (hazard ratio: 1.06; 95% CI, 0.96–1.17; Fig. 1) or when stratified by gender or age (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). There was virtually no impact on results when excluding individuals ever dispensed an inhaled glucocorticoid during follow-up (Supplementary Table 7).

Fig. 1 Psychiatric and suicidal behaviour outcomes in individuals dispensed a glucocorticoid (medication-only cohort) using a within-individual analysis, stratified by indication and past psychiatric diagnosis.

We also carried out between-individual analyses in the medication-only cohort (Supplementary Table 8). For all diagnostic outcomes, effect estimates were higher in between-individual compared with within-individual analyses. For example, the hazard ratio for anxiety disorder was 1.70 (95% CI, 1.64–1.77) in between-individual analyses and 1.25 (95% CI, 1.20–1.31) in within-individual analyses.

To assess whether individuals with past psychiatric diagnoses were at greater risk of psychiatric outcomes, we considered a subset of the medication-only cohort in which all individuals had received a diagnosis of one of the psychiatric outcomes considered in the analyses before the start of follow-up (n = 80 952, 7.3%; Supplementary Table 8). The results were very similar to those in the main cohort, though absolute rates were highest for all outcomes in those with a psychiatric history (Fig. 1).

We stratified the medication-only cohort by diagnosis with an autoimmune disorder (n = 153 848, 13.9% of cohort) and diagnosis with a gastrointestinal autoimmune disorder (n = 58 318, 5.3% of cohort; Supplementary Table 8). Associations were attenuated in both strata compared with the overall cohort, with wide confidence intervals. Point estimates were similar to those in the overall cohort for depression and bipolar disorder outcomes (Fig. 1).

When considering risks in periods relative to treatment start, it appeared that the first 14 days since treatment start were associated with the highest hazard relative to untreated periods for anxiety (hazard ratio: 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27–1.47) and bipolar disorders (hazard ratio: 1.58; 95% CI, 1.35–1.85; Supplementary Table 9).

We further investigated the impact of average dose on the risk of the outcomes (Supplementary Table 10). A high or medium dose was associated with elevated hazard ratios for anxiety and bipolar disorder outcomes.

We also ran the main within-individual analyses in a cohort from the years 2006–2013 (n = 680 215), where we could ensure that the dispensed medication was restricted to glucocorticoids (H02AB). There were no material differences in the results (Supplementary Table S11).

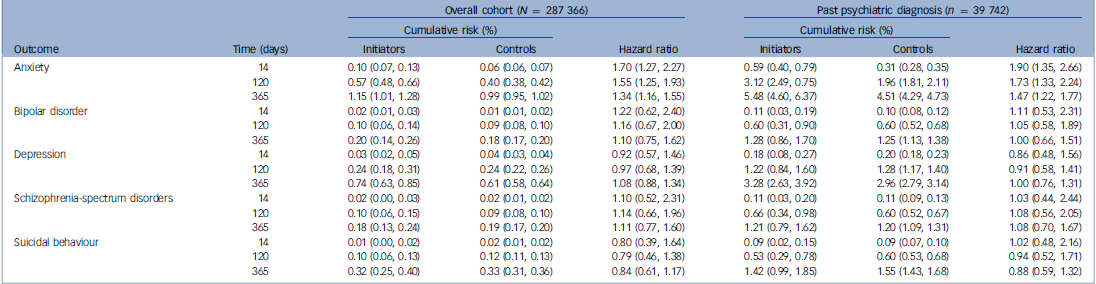

Finally, we considered two cohorts defined by having a diagnosis of either any autoimmune disorder (n = 287 366) or a gastrointestinal autoimmune disorder (n = 96 029) rather than by medication receipt, in order to emulate two target trials assessing the effect on psychiatric and suicidal behaviour risks of initiating a glucocorticoid following an autoimmune diagnosis (Supplementary Table 1). We applied IPW to balance baseline confounders between initiators and controls – an SMD of <0.1 was achieved for all covariates after weighting (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3), indicating sufficiently balanced covariates. Reference Austin27 In the intention-to-treat analyses, we found evidence of an increased risk of anxiety outcomes among initiators in the autoimmune disorder cohort, in particular early in follow-up (hazard ratio in the first 14 days of follow-up: 1.70; 95% CI, 1.27–2.27; Table 2). This was replicated when we stratified the cohort on past psychiatric diagnosis. We did not find evidence of other associations, and confidence intervals were wide. Anxiety outcomes had the highest cumulative incidence over follow-up. Those with past psychiatric diagnoses had substantially elevated cumulative risk of the outcomes: for example, 5.48% of initiators with a past psychiatric diagnosis had an anxiety outcome over the full 365 days of follow-up, compared with 1.15% of those with no history of a mental health disorder (Table 2). In per-protocol analyses, point estimates were similar but all confidence intervals included 1 (Supplementary Table 12). We found no clear evidence of an association for any of the outcomes in the gastrointestinal autoimmune disorder cohort, in either the per-protocol or intention-to-treat analyses (Supplementary Tables 12 and 13).

Table 2 Intention-to-treat analyses in individuals with an autoimmune disorder diagnosis´´ (indication cohort), stratified by past psychiatric diagnosis

Discussion

In this population-based nationwide study of 1 105 964 people, we found that glucocorticoid treatment was associated with modestly elevated risks of unplanned specialist healthcare contacts due to anxiety, depressive, bipolar or schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. The findings were consistent across men and women, different age bands and individuals with a prior history of psychiatric disorder. Those with a history of psychiatric disorders had a higher absolute risk of all outcomes, and there may be a particularly elevated risk early in the treatment course. Glucocorticoid treatment was not associated with suicidal outcomes.

Our findings suggest that clinicians should be vigilant for the risk of acute psychiatric outcomes during glucocorticoid treatment, and have awareness that individuals with a history of psychiatric disorders have an elevated baseline risk. Further research is necessary to predict who is at greatest risk of adverse psychiatric events during glucocorticoid treatments, Reference Judd, Schettler, Brown, Wolkowitz, Sternberg and Bender1 and to investigate the impacts of dose and glucocorticoid subtype in more depth.

The lack of strong links between glucocorticoids and suicidal behaviour in our study is novel. A previous observational study using a between-individual design in UK primary care data found that glucocorticoid treatment was associated with a substantially increased hazard of suicidal behaviour (hazard ratio: 6.9; 95% CI, 4.5–10.5). Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3 This discrepancy with our results may be due to residual between-individual confounding in the previous paper. Our study also exclusively considered diagnoses from specialist care for the non-fatal component of suicidal behaviour, meaning that our outcome is likely to represent more serious suicidal behaviours. Meanwhile, another investigation, in Danish national health registers, found a substantially elevated risk of suicide death following glucocorticoid treatment, Reference Laugesen, Farkas, Vestergaard, Jørgensen, Petersen and Sørensen4 although comparison with our results is difficult given that we considered a composite outcome including self-harm in addition to suicide death.

Regarding psychiatric outcomes, our results are broadly consistent with prior evidence. Reference Naber, Sand and Heigl28,Reference Bolanos, Khan, Hanczyc, Bauer, Dhanani and Brown29 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence from observational studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) found elevated risk of depression and mania, Reference Koning, van der Meulen, Schaap, Satoer, Vinkers and van Rossum30 although the included studies were highly heterogeneous. Compared with the previous large cohort study in UK primary care data discussed above, our associations were weaker: for example, we found a hazard ratio of 1.1 (95% CI, 1.0–1.2) for depression, compared with 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7–1.9) in the prior study. Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3 The attenuated associations in our study may be due partly to our use of specialist care contacts to define outcomes. This is also likely to have reduced the prevalence of the outcomes. The proportion of glucocorticoid users with outcomes was lower in our study than in the prior review, which found that 22% of all glucocorticoid users experienced events related to depressive disorder, Reference Koning, van der Meulen, Schaap, Satoer, Vinkers and van Rossum30 as compared with 3.9% in our study.

Consistent with previous literature, we found that the risk of events related to anxiety and bipolar disorder was higher in the first few weeks of glucocorticoid treatment. Reference Warrington and Bostwick31 Prior studies also found a dose–response relationship of glucocorticoids with the outcome. Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3–Reference Dalal, Duh, Gozalo, Robitaille, Albers and Yancey5 While our results may be consistent with such an effect, our method used to estimate average dose made it difficult to separate the effects of dose from the impact of treatment time (see ‘Limitations’ below). Despite prior work finding that age is a moderator of the psychiatric effects of glucocorticoids, Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth3,Reference Laugesen, Farkas, Vestergaard, Jørgensen, Petersen and Sørensen4,Reference O’Connor, Ferguson, Green, O’Carroll and O’Connor32 our results do not support this.

In the between-individual analyses in the medication-only cohort, the associations with all outcomes were higher compared with the within-individual analyses, and there was a statistically significantly increased risk of suicidal behaviour. It is possible that individuals who have a higher baseline risk for psychiatric disorders also have a higher propensity for repeated treatment with glucocorticoids. This would inflate the associations of glucocorticoids with psychiatric outcomes when between-individual confounding is not fully accounted for.

We attempted to account for the impact of different indications for glucocorticoid treatment by stratifying on autoimmune and gastrointestinal autoimmune disorders in the medication-only cohort (Fig. 1). Associations were attenuated in both diagnosis strata as compared with the overall cohort, with wide confidence intervals. The smaller number of individuals may make it hard to draw conclusions about outcomes that are already rare; alternatively, restricting to one type of indication may change the impact of time-varying confounding.

We further triangulated our results by following individuals diagnosed with an autoimmune or gastrointestinal autoimmune disorder and comparing psychiatric risks in those who did and did not initiate a glucocorticoid shortly after their diagnosis. Here, we found elevated risks of anxiety outcomes over the full follow-up in glucocorticoid initiators with an autoimmune disorder diagnosis. Similar to findings in the medication-only cohort, risks appeared particularly elevated over the first 2 weeks of treatment. No statistically significant associations were found for other outcomes, or in the gastrointestinal autoimmune cohort, although these cohorts were limited in sample size and confidence intervals were wide.

There is extensive evidence supporting a causal relationship between glucocorticoid treatment and psychiatric events. Reference Kenna, Poon, de los Angeles and Koran33 Dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which controls glucocorticoid production in the body, has been linked to risk of anxiety and depression. Reference Thibaut34 Cortisol levels are elevated in individuals with first-episode psychosis, Reference Misiak, Pruessner, Samochowiec, Wiśniewski, Reginia and Stańczykiewicz35 and long-term exposure to excess glucocorticoids has been linked to lower grey matter volume in the brain and higher rates of depression. Reference Dekkers, Amaya, van der Meulen, Biermasz, Meijer and Pereira36

Strengths and limitations

A key strength is our use of a data linkage covering virtually the entire Swedish population. To our knowledge, this is also the first large-scale observational study to investigate psychiatric and suicidal behaviour risks of glucocorticoid treatment using both a self-controlled design and a target trial emulation approach.

Several limitations should be noted. First, while our within-individual analyses accounted for all time-invariant confounding, we could not account for unmeasured time-varying confounding, including confounding by indication. Glucocorticoids are prescribed for a wide range of disorders, including those known to be associated with psychological distress. One important example is cancer, which is the indication for a significant proportion of individuals taking glucocorticoids. Reference Einarsdottir, Ekman, Trimpou, Olsson, Johannsson and Ragnarsson37 We did not have specific diagnostic information on cancer in our data linkage. If prescribed a glucocorticoid due to, for example, cancer relapse, any apparent psychiatric risk of treatment may be due to the distress of dealing with a serious somatic disorder. This is also likely to be true of autoimmune disorders, which are associated with discomfort and stress – there are bidirectional relationships between autoimmune and psychiatric disorders. Reference Liu, Nudel, Thompson, Appadurai, Schork and Buil38 However, it is also possible that certain chronic symptoms of the indicating disorders are alleviated during glucocorticoid treatment, which may have positive psychiatric effects. Second, we did not have information on diagnoses given in primary care, and hence could not estimate risks of less serious psychiatric and behavioural outcomes. However, our inclusion of unplanned specialist care diagnoses meant that we have investigated more serious events that are of greatest clinical interest. Many prior studies consider less serious forms of the outcomes, making our study a useful addition to the literature. Third, our treatment period definition may misclassify follow-up time as either treated or untreated: we do not know whether individuals consumed their medication following purchase. This means that our analyses estimate a modified intention-to-treat effect, which is expected to bias results toward the null. Reference Hernán and Hernández-Díaz39 The classification of any given time period as treated or untreated also relied on whether a medication was dispensed at a future point in time – that is, within 120 days since the last dispensed prescription. This may induce bias if, for example, the occurrence of an outcome of interest influences future prescribing behaviour. However, the intention-to-treat analyses in the target trial emulations were not subject to this bias. We also did not have structured information on the prescribed daily dose, but calculated the average daily dose by taking cumulative dispensed DDD divided by treatment time. This was subject to the same issues of reliance on future prescription information as described above, and made it difficult to separate effects of treatment duration from those of treatment dose. Finally, while our results derive from a large and nationally representative cohort with comprehensive information on psychiatric diagnoses received in specialist care, they may not be generalisable to other time periods, national settings or clinical contexts.

In conclusion, we found that glucocorticoid treatment is associated with an elevated risk for psychiatric events leading to unplanned specialist psychiatric care, but not for suicidal behaviour. Risks may be particularly elevated during the first few weeks of treatment. Absolute rates were highest among those with a past psychiatric history, suggesting that this population might require greater clinical attention. Clinicians should be vigilant for serious psychiatric outcomes during glucocorticoid treatment, including the onset and relapse of common psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.128

Data availability

The Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act in Sweden prohibits us from making individual-level data publicly available. Researchers may apply for individual-level data from the National Board of Health and Welfare for data from the Patient Register, the Prescribed Drug Register or the Cause of Death Register; and to Statistics Sweden for data from the Total Population Register.

Author contributions

T.L., T.T.G. and S.F. formulated the research questions. T.L. and S.F. designed the study. T.L. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript, with detailed input from all co-authors. All co-authors contributed to interpretation of the data.

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (no. 202836/Z/16/Z) and by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (grant number not applicable). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

A.S. and S.F. are further supported by the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre (grant no. BRC-1215-20005). The funding sources had no involvement in writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit, or in data collection, analysis or interpretation or any aspect pertinent to the study. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of interest

None.

Transparency declaration

T.L. acts as guarantor and affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.