1. Introduction

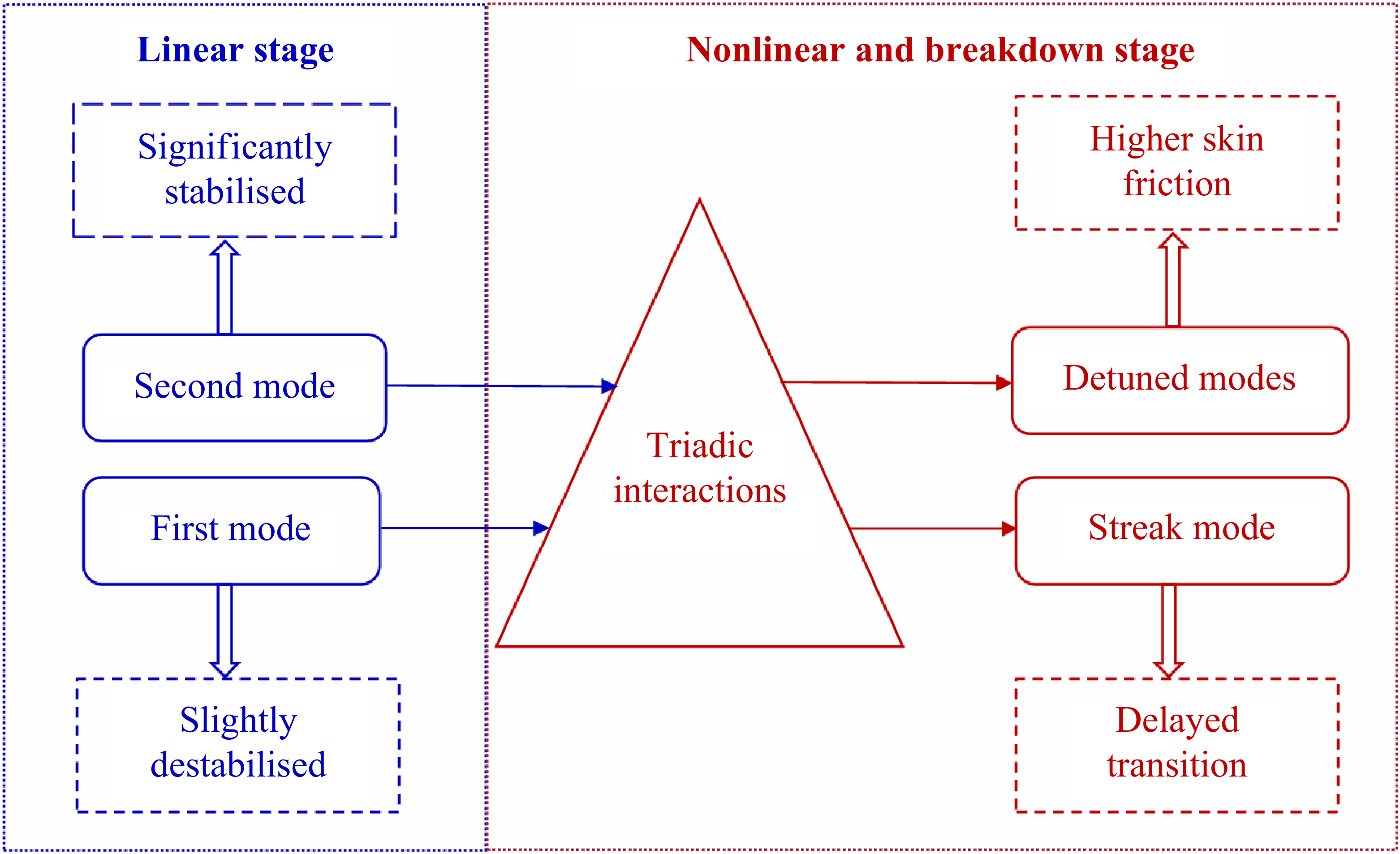

One of the key obstacles to the development of hypersonic vehicles has been the prediction and control of the laminar–turbulent boundary-layer transition. The performance of hypersonic vehicles may be compromised by the transition, as it would escalate skin friction and heat flux (Fedorov Reference Fedorov2011). Therefore, accurate transition prediction and effective control (or delay) technologies are crucial for the design of hypersonic vehicles, particularly regarding the thermal protection system. Transition induced by free-stream disturbances with low amplitudes usually follows four stages: receptivity (excitation of initial disturbance inside the boundary layer), linear instability (including modal and non-modal growth), nonlinear instability and parametric resonance and breakdown to turbulence (Morkovin et al. Reference Morkovin1994). Hypersonic boundary-layer transition over two-dimensional or axisymmetric models at a zero angle of attack is typically triggered by the growth of unstable modes, known as the first mode, associated with the vorticity disturbance (Smith Reference Smith1989), and the Mack second mode of acoustic nature (Mack Reference Mack1975; Fedorov Reference Fedorov2003; Ma & Zhong Reference Ma and Zhong2003; Chen, Guo & Wen Reference Chen, Guo and Wen2023a ). In realistic flight or wind tunnel conditions, these two types of instabilities tend to coexist and compete with one another.

Regarding the breakdown or parametric resonance, several scenarios have been confirmed by numerous direct numerical simulations (DNS) and experimental studies. These include the first-mode-dominated subharmonic resonance (Kosinov et al. Reference Kosinov, Semionov, Shevel’kov and Zinin1994), the first-mode-dominated oblique breakdown (Mayer, Von Terzi & Fasel Reference Mayer, Von Terzi and Fasel2011), the second-mode oblique breakdown (Hartman, Hader & Fasel Reference Hartman, Hader and Fasel2021), the second-mode-dominated fundamental resonance (Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Jewell, Paredes and Laurence2022; Unnikrishnan & Gaitonde Reference Unnikrishnan and Gaitonde2020) and the second-mode subharmonic resonance (Bountin, Shiplyuk & Maslov Reference Bountin, Shiplyuk and Maslov2008; Franko & Lele Reference Franko and Lele2013). These conventional transition scenarios are characterised by tuned modes with frequencies that are integer times

![]() $f_{1/2}$

; here,

$f_{1/2}$

; here,

![]() $f_{1/2}$

refers to half of the frequency of the primary instability wave. The dominating transition scenario depends on the specific numerical forcing with given flow and geometric conditions. In a realistic disturbance environment, several primary instabilities can be excited simultaneously and coexist. In this case, complex mode–mode interactions emerge, and detuned modes may be pronounced (Fezer & Kloker Reference Fezer and Kloker2000). As reported by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017) for the flared-cone model at Peking University, multiple primary instabilities give rise to complex nonlinear interactions and significant energy transfer between low- and high-frequency components. A possible combination resonance is also indicated, which differs from that induced by a single primary instability (Franko & Lele Reference Franko and Lele2013; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019). Nonetheless, direct evidence in the transitional stage was not provided. Recently, Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

) have demonstrated the significance of the non-conventional combination resonance associated with modal detuning in the high-speed boundary-layer transition. The nonlinear interaction between low-frequency first mode and high-frequency second mode can produce a new breakdown scenario. This multiple-primary-instabilities scenario is believed to be noteworthy, since multiple instabilities are seeded in realistic boundary layers. As an extension, the effect of flow control on the breakdown scenario is of particular interest.

$f_{1/2}$

refers to half of the frequency of the primary instability wave. The dominating transition scenario depends on the specific numerical forcing with given flow and geometric conditions. In a realistic disturbance environment, several primary instabilities can be excited simultaneously and coexist. In this case, complex mode–mode interactions emerge, and detuned modes may be pronounced (Fezer & Kloker Reference Fezer and Kloker2000). As reported by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017) for the flared-cone model at Peking University, multiple primary instabilities give rise to complex nonlinear interactions and significant energy transfer between low- and high-frequency components. A possible combination resonance is also indicated, which differs from that induced by a single primary instability (Franko & Lele Reference Franko and Lele2013; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019). Nonetheless, direct evidence in the transitional stage was not provided. Recently, Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

) have demonstrated the significance of the non-conventional combination resonance associated with modal detuning in the high-speed boundary-layer transition. The nonlinear interaction between low-frequency first mode and high-frequency second mode can produce a new breakdown scenario. This multiple-primary-instabilities scenario is believed to be noteworthy, since multiple instabilities are seeded in realistic boundary layers. As an extension, the effect of flow control on the breakdown scenario is of particular interest.

Boundary-layer transition control strategies are useful in delaying the occurrence of transition. These strategies can be categorised into active methods, such as wall cooling and heating (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wen, Tian, Long and Yuan2018b ; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Liu, Lu, Kang and Yan2022), and passive methods, such as the acoustic metasurface implemented by a porous coating (Fedorov et al. Reference Fedorov, Malmuth and Rasheed2001; Zhao et al. Reference Zhou, Liu, Lu, Kang and Yan2022). The acoustic metasurface, including the absorptive acoustic metasurface, the impedance-near-zero acoustic metasurface and the reflection-controlled acoustic metasurface, was proposed mainly to suppress the second mode of acoustic nature (Zhao et al. Reference Zhou, Liu, Lu, Kang and Yan2022). The passive approach is flexible for implementation and requires no additional energy input, which has attracted growing interest from both academia and industry. Experimental observations have shown that the porous coating can successfully postpone the transition onset (Rasheed, Hornung & Fedorov Reference Rasheed, Hornung, Fedorov and Malmuth2002; Fedorov et al. Reference Fedorov2003; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Kuhn, Martinez Schramm and Hannemann2013, Reference Wagner, Hannemann and Kuhn2014). However, a porous coating leads to an undesirable increment of wall friction and flux during the late stage of transitional flow. This phenomenon has been observed experimentally (Wartemann, Wagner & Kuhn Reference Wartemann, Wagner, Kuhn, Eggers and Hannemann2015) but remains poorly understood.

In the linear stability stage, the effect of the porous coating can be theoretically described and satisfactorily predicted using linear stability theory (LST) with the deduced acoustic impedance boundary condition (Fedorov et al. Reference Fedorov, Malmuth and Rasheed2001). The physical mechanism by which the porous coating influences the linear stage has been widely studied (Fedorov et al. Reference Fedorov2003; Tian & Wen Reference Tian and Wen2021; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Guo and Wen2023b ; Ji, Dong & Zhao Reference Ji, Dong and Zhao2023). It is known that viscous effects within the pores of the porous coating can dissipate the second-mode instability. Acoustic wave reflection is also linked to regimes with phase cancellation or reinforcement (Bres et al. Reference Brès, Inkman and Colonius2013). The porous coating effect in the nonlinear regime has also been the subject of early research (Tullio et al. Reference De Tullio and Sandham2010; Hader et al. Reference Hader, Brehm and Fasel2013, Reference Hader, Brehm and Fasel2014). Tullio et al. (Reference De Tullio and Sandham2010) conducted the first DNS of nonlinear breakdown with directly resolved pore-scale flow in an acoustic metasurface. Their study provided a detailed analysis of how porous coatings affect secondary instabilities for both first and second instability modes individually. Hader et al. (Reference Hader, Brehm and Fasel2013, Reference Hader, Brehm and Fasel2014) discovered that the second-mode fundamental breakdown caused a delayed transition onset. However, these investigations are restricted to single-primary-mode perturbations and the resulting typical breakdown situations, which may not accurately represent the transitional flow with broadband disturbances in wind tunnels or flight tests. Recently, Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Wartemann and Wagner2024) investigated the hypersonic transition delay over a broadband wall impedance using dynamic large-eddy simulation. Good agreement was observed with experimental data in the literature. The corresponding wind tunnel experiment features a high-enthalpy flow with a highly cooled wall condition, where the first mode is significantly suppressed. Consequently, the nonlinear interaction between the low-frequency first mode and the high-frequency second mode was not considered in their simulation. The resulting breakdown is more likely to be a fundamental breakdown induced by the second mode, which represents the only dominant instability under such cold-wall conditions.

Triadic interactions serve as the fundamental mechanism governing energy transfer in nonlinear flow fields, playing a well-documented role in laminar–turbulent transition. The seminal work by Craik (Reference Craik1971) established that resonant Tollmien – Schlichting wave triads can significantly accelerate transition in wall-bounded shear flows. Building on this, Rigas et al. (Reference Rigas, Sipp and Colonius2021) employed resolvent analysis incorporating nonlinear triadic interactions, demonstrating that the transition dynamics can be accurately captured using only a limited number of harmonics and their triadic couplings. To quantify such interactions, bispectral mode decomposition (BMD) proposed by Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2020) has emerged as a powerful diagnostic tool, enabling identification of dominant triads and their associated energy-transfer pathways in three-dimensional nonlinear flows. For instance, Schmidt & Oberleithner (Reference Schmidt and Oberleithner2023) applied bispectral analysis to two-phase swirling flows, revealing that triadic resonance generates a broad spectrum of secondary modes. Recent advances by Craig et al. (Reference Craig, Humble, Hofferth and Saric2019) further extended BMD to hypersonic boundary layers, where bispectral analysis of experimental data identified multiple quadratic phase-coupled sum and difference interactions. Their findings suggest that, under quiet wind tunnel conditions, the nonlinear transition mechanism is predominantly governed by high-frequency second-mode-induced fundamental breakdown. Nevertheless, this framework may not fully explain transition scenarios involving mutual interactions between low-frequency first modes and high-frequency second modes, revealing the need for further investigations on multimodal triadic coupling effects.

Even though the linear-stage stabilisation or destabilisation mechanisms are well established, how metasurfaces modulate nonlinear interactions between coexisting first and second modes – a scenario routinely encountered in practice – remains unknown. Moreover, the undesired increase of late-stage skin friction observed experimentally has yet to be explained through first-principles simulations. The current work is to examine the impact of porous coatings on the nonlinear mode–mode interaction and the resulting breakdown process. Two research objectives are included: (i) to reveal the transition delay mechanism by the acoustic metasurface subject to multiple primary instabilities; (ii) to explain why the skin friction is augmented in the late transitional stage. To this end, the effect of the metasurface is evaluated using a modelled impedance boundary condition (IBC) to avoid meshing the cavity, which can save computational costs. The time-domain impedance boundary condition (TDIBC) (Fung & Ju Reference Fung and Ju2004; Douasbin, Scalo & Selle Reference Douasbin, Scalo, Selle and Poinsot2018; Fiévet et al. Reference Fiévet, Deniau, Brazier and Piot2021; Guo, Hao & Wen Reference Guo, Liu, Zhao, Hao and Wen2023b ) can be efficiently incorporated into a Navier–Stokes solver and handle broadband disturbances. The accuracy and efficiency of TDIBC have been shown in the simulation of late transitional and turbulent boundary layers (Scalo, Bodart & Lele Reference Scalo, Bodart and Lele2015; Chen & Scalo Reference Chen and Scalo2021b ; Sousa et al. Reference Sousa, Wartemann and Wagner2024). It is anticipated that the mode–mode interaction and the resulting breakdown scenario with the acoustic metasurface will be revealed to understand why the transition onset is delayed. Moreover, regarding the enhanced skin friction in the late transition stage, which has also been observed in the experiments by Wagner et al. (Reference Wagner, Kuhn, Martinez Schramm and Hannemann2013, Reference Wagner, Hannemann and Kuhn2014), an energy budget analysis and bi-Fourier analysis are performed to explore the underlying physics.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the investigated model and flow parameters, the formulation of TDIBC, stability analysis tools and numerical methods for DNS. Section 3 presents the fitting results of TDIBC using a theoretical model, the results of the stability analysis and the effect of TDIBC on the linear stage. Comparative transition simulations induced by multiple disturbances with and without the acoustic metasurface are shown in §§ 4 and 5. The instantaneous and time-averaged flow fields, bi-Fourier analysis, results of BMD and energy budget analysis are included. Section 4 characterises the three-dimensional flow structure and provides statistical analysis of mean-flow properties, while § 5 investigates the nonlinear mode – mode interactions and subsequent breakdown dynamics. The principal findings and their physical implications are systematically summarised in § 6.

2. Flow condition and methodology

The free-stream flow condition investigated is based on a wind tunnel experiment by Bountin et al. (Reference Bountin, Chimitov, Maslov, Novikov, Egorov, Fedorov and Utyuzhnikov2013) at Mach 6 and unit Reynolds number

![]() $1.05 \times {10^{7}}\,{\text{m}^{ - 1}}$

. The free-stream temperature

$1.05 \times {10^{7}}\,{\text{m}^{ - 1}}$

. The free-stream temperature

![]() $T_\infty$

is 43.18 K and the isothermal wall temperature (room temperature, which approaches the adiabatic wall condition)

$T_\infty$

is 43.18 K and the isothermal wall temperature (room temperature, which approaches the adiabatic wall condition)

![]() $T_w$

= 293 K are employed. In this study, the subscripts ‘

$T_w$

= 293 K are employed. In this study, the subscripts ‘

![]() $\infty$

’ and ‘

$\infty$

’ and ‘

![]() $w$

’ refer to the values at free stream and on the wall, respectively. The free-stream variables are utilised for non-dimensionalisation, except that

$w$

’ refer to the values at free stream and on the wall, respectively. The free-stream variables are utilised for non-dimensionalisation, except that

![]() ${\rho _\infty }u_\infty ^2$

is utilised for pressure,

${\rho _\infty }u_\infty ^2$

is utilised for pressure,

![]() $u$

is the streamwise velocity and

$u$

is the streamwise velocity and

![]() $\rho$

is the density. Unless otherwise stated, the reference length

$\rho$

is the density. Unless otherwise stated, the reference length

![]() $L_{\textit {ref}}$

is taken as 1 mm. Without unit markings, the following physical quantities are presented in their dimensionless form.

$L_{\textit {ref}}$

is taken as 1 mm. Without unit markings, the following physical quantities are presented in their dimensionless form.

2.1. Direct numerical simulation

The governing equation for the computation of flow fields is the compressible Navier–Stokes equation in the conservation form

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol{U}} = (\rho , \,\rho u,\,\rho v,\,\rho w,\,\rho e)^{\textrm {T}}$

is the vector of conservative variables, and

${\boldsymbol{U}} = (\rho , \,\rho u,\,\rho v,\,\rho w,\,\rho e)^{\textrm {T}}$

is the vector of conservative variables, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}$

,

$\boldsymbol{F}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{G}$

and

$\boldsymbol{G}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{H}$

are the vectors of inviscid and viscous fluxes. Detailed expressions can be found in Anderson (Reference Anderson1995). Here,

$\boldsymbol{H}$

are the vectors of inviscid and viscous fluxes. Detailed expressions can be found in Anderson (Reference Anderson1995). Here,

![]() $\rho$

is density, and

$\rho$

is density, and

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $w$

are velocities in the Cartesian

$w$

are velocities in the Cartesian

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

directions, respectively. Total energy per unit mass is denoted by

$z$

directions, respectively. Total energy per unit mass is denoted by

![]() $e$

. The matrix

$e$

. The matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D63D}$

constrains the forcing vector (

$\unicode{x1D63D}$

constrains the forcing vector (

![]() $\boldsymbol{f'}$

) to be added at a certain region, which is set to be

$\boldsymbol{f'}$

) to be added at a certain region, which is set to be

![]() $x$

= 0.04 m in this study. In the DNS, the optimal forcings obtained by resolvent analysis are employed to initiate the unsteady flow.

$x$

= 0.04 m in this study. In the DNS, the optimal forcings obtained by resolvent analysis are employed to initiate the unsteady flow.

The perfect gas model is employed with a constant specific heat ratio of 1.4. Furthermore, the dynamic viscosity is calculated using Sutherland’s law with a constant

![]() $T_s$

= 110.4 K, and the thermal conductivity coefficient is calculated based on a constant Prandtl number 0.72. The simulation constitutes two steps. In the first step, the base flow is calculated, and the right-hand side term of (2.1) is set to zero. Subsequently, the resolvent analysis or DNS is performed on the converged base flow. It is assumed that the vector of conservation variable can be decomposed into its base-flow and perturbation parts

$T_s$

= 110.4 K, and the thermal conductivity coefficient is calculated based on a constant Prandtl number 0.72. The simulation constitutes two steps. In the first step, the base flow is calculated, and the right-hand side term of (2.1) is set to zero. Subsequently, the resolvent analysis or DNS is performed on the converged base flow. It is assumed that the vector of conservation variable can be decomposed into its base-flow and perturbation parts

Hereafter, the overbar and prime represent mean variables and perturbation variables, respectively.

The DNS is performed using a multi-block parallel finite difference solver called OpenCFD, which has been successfully employed in high-speed transitional and turbulent simulations (Li et al. 2002, Li et al. 2009). The inviscid flux splitting is implemented by the Steger – Warming scheme, and a seven-order weight essential non-oscillation scheme is employed for the reconstruction of the split flux. The sixth-order central difference scheme is utilised for viscous flux discretisation, and a third-order Runge – Kutta method is employed for temporal integration. With regard to the boundary condition, the left boundary of the computational domain is free stream, and the wall is set to be isothermal, no slip and no penetration or with TDIBC in a certain region. Furthermore, the computational domain extends upstream to

![]() $x$

= −0.05 m with a slip-wall (inviscid symmetry) boundary condition to ensure proper inflow development and mitigate potential numerical instabilities. The upper and outer boundaries are addressed by extrapolation. The spanwise boundary is set to be periodic.

$x$

= −0.05 m with a slip-wall (inviscid symmetry) boundary condition to ensure proper inflow development and mitigate potential numerical instabilities. The upper and outer boundaries are addressed by extrapolation. The spanwise boundary is set to be periodic.

2.2. Time-domain impedance boundary condition

Direct numerical simulation with realistic metasurface microstructures can be conducted to investigate the transition control mechanism. However, it is computationally expensive to mesh numerous micro-cavities. To efficiently and simultaneously simulate the interactions between acoustic metasurfaces and multi-modal waves, the application of an IBC is recommended. The early acoustic impedance models of a metasurface were all built in the frequency domain and applied with a single disturbance frequency in hypersonic boundary-layer transition studies (Fedorov et al. Reference Fedorov, Malmuth and Rasheed2001; Möser & Michael Reference Möser2009), which means that they are not suitable for transition considering broadband disturbances. In this study, a multi-pole broadband impedance model with a piecewise linear recursive convolution technique proposed by Fung & Ju (Reference Fung and Ju2004) will be revised and incorporated into the current DNS code afterwards. This embedded boundary condition enables efficient simulations of broadband-disturbance propagation by transforming the acoustic IBC from the frequency domain into the time domain.

The reflective coefficient

![]() $\tilde R$

in the frequency domain is defined as

$\tilde R$

in the frequency domain is defined as

where

![]() $\omega$

is the angular frequency,

$\omega$

is the angular frequency,

![]() ${A^{\textit {in}}}$

and

${A^{\textit {in}}}$

and

![]() ${A^{\textit {out}}}$

are the amplitudes of ingoing and outgoing waves, respectively. The ingoing and outgoing waves are related to the physical variables of the flow field (pressure and velocity) at the wall (Fung & Ju Reference Fung and Ju2004). Their amplitudes are defined as

${A^{\textit {out}}}$

are the amplitudes of ingoing and outgoing waves, respectively. The ingoing and outgoing waves are related to the physical variables of the flow field (pressure and velocity) at the wall (Fung & Ju Reference Fung and Ju2004). Their amplitudes are defined as

where

![]() $\textit{Ma}$

is the Mach number and

$\textit{Ma}$

is the Mach number and

![]() $p$

is the pressure. The wall softness

$p$

is the pressure. The wall softness

![]() $\tilde S$

is given by

$\tilde S$

is given by

Physically

![]() $\tilde S$

= 2 and

$\tilde S$

= 2 and

![]() $\tilde S$

= 1 when the wall is totally reflective (rigid wall) and absorptive (soft wall), respectively. Combining (2.3) and (2.5) gives rise to

$\tilde S$

= 1 when the wall is totally reflective (rigid wall) and absorptive (soft wall), respectively. Combining (2.3) and (2.5) gives rise to

The softness can be approximated by a multi-oscillator model proposed by Fung & Ju (Reference Fung and Ju2004)

\begin{align} \tilde S(s) = \mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \left [ {\frac {{{\mu _k}}}{{s - {p_k}}} + \frac {{\mu _k^\dagger }}{{s - p_k^\dagger }}} \right ] + {C_0},\: s = {\textrm {i}}\omega , \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde S(s) = \mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \left [ {\frac {{{\mu _k}}}{{s - {p_k}}} + \frac {{\mu _k^\dagger }}{{s - p_k^\dagger }}} \right ] + {C_0},\: s = {\textrm {i}}\omega , \end{align}

where

![]() $p_k$

and

$p_k$

and

![]() $p_k^\dagger$

are poles of pole base function, and

$p_k^\dagger$

are poles of pole base function, and

![]() ${\mu _k} = {\textrm {i}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\textrm {Residue}} [ {\tilde S(s),{p_k}} ]$

. The superscript

${\mu _k} = {\textrm {i}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\textrm {Residue}} [ {\tilde S(s),{p_k}} ]$

. The superscript

![]() $\dagger$

refers to complex conjugate, and

$\dagger$

refers to complex conjugate, and

![]() $n_0$

is the total number of pole pairs. In addition,

$n_0$

is the total number of pole pairs. In addition,

![]() $C_0$

is a constant real number. The utilisation of this constant number to improve the accuracy of the model was also reported by Fiévet et al. (Reference Fiévet, Deniau, Brazier and Piot2021). Due to the requirement of the reality of the signal (Rienstra Reference Rienstra2006), the softness in the time domain must be real and

$C_0$

is a constant real number. The utilisation of this constant number to improve the accuracy of the model was also reported by Fiévet et al. (Reference Fiévet, Deniau, Brazier and Piot2021). Due to the requirement of the reality of the signal (Rienstra Reference Rienstra2006), the softness in the time domain must be real and

![]() ${\tilde S^\dagger }(s) = \tilde S( - s)$

. The values of poles and residue are obtained from a nonlinear fitting process (Douasbin et al. Reference Douasbin, Scalo, Selle and Poinsot2018) to approximate the softness calculated from a well-validated impedance model, which considers the effect of high-order diffraction (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Liu, Wen and Cheng2018a

). The authors have fully validated the impedance model by comparing it with the DNS result over meshed metasurface (Zhao, Wen & Long Reference Zhao, Wen, Long, Tian, Zhou and Wu2019; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Zhao, Hao and Wen2023b

). Then, the softness in the time domain can be obtained using the inverse Fourier transform

${\tilde S^\dagger }(s) = \tilde S( - s)$

. The values of poles and residue are obtained from a nonlinear fitting process (Douasbin et al. Reference Douasbin, Scalo, Selle and Poinsot2018) to approximate the softness calculated from a well-validated impedance model, which considers the effect of high-order diffraction (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Liu, Wen and Cheng2018a

). The authors have fully validated the impedance model by comparing it with the DNS result over meshed metasurface (Zhao, Wen & Long Reference Zhao, Wen, Long, Tian, Zhou and Wu2019; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Zhao, Hao and Wen2023b

). Then, the softness in the time domain can be obtained using the inverse Fourier transform

Using the Residue theorem, one may obtain

\begin{align} \tilde S(t) = \left ( {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} {\mu _k}{e^{{p_k}t}} + \mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \mu _k^\dagger {e^{p_k^\dagger t}}} \right )H(t) + {C_0}\delta (t). \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde S(t) = \left ( {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} {\mu _k}{e^{{p_k}t}} + \mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \mu _k^\dagger {e^{p_k^\dagger t}}} \right )H(t) + {C_0}\delta (t). \end{align}

Here, the Heaviside function

![]() $H$

(

$H$

(

![]() $t$

) indicates that the causality condition is satisfied, and

$t$

) indicates that the causality condition is satisfied, and

![]() $\delta$

is the Dirac delta function. Taking the inverse Fourier transform of (2.6), one may obtain

$\delta$

is the Dirac delta function. Taking the inverse Fourier transform of (2.6), one may obtain

where

![]() $\tau$

is the dummy integration variable representing time. Substituting (2.9) into (2.10) yields

$\tau$

is the dummy integration variable representing time. Substituting (2.9) into (2.10) yields

\begin{align} {A^{\textit {out}}}(t) = ({C_0} - 1){A^{\textit {in}}}(t) + \int _0^\infty {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \left({\mu _k}{e^{{p_k}\tau }} + \mu _k^\dagger {e^{p_k^\dagger \tau }} \right){A^{\textit {in}}}(t - \tau )} {\rm d}\tau . \end{align}

\begin{align} {A^{\textit {out}}}(t) = ({C_0} - 1){A^{\textit {in}}}(t) + \int _0^\infty {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \left({\mu _k}{e^{{p_k}\tau }} + \mu _k^\dagger {e^{p_k^\dagger \tau }} \right){A^{\textit {in}}}(t - \tau )} {\rm d}\tau . \end{align}

For the next time at step

![]() $t + \Delta t$

, (2.11) can be written as

$t + \Delta t$

, (2.11) can be written as

\begin{align} {A^{\textit {out}}}(t + \Delta t) = ({C_0} - 1){A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t) + \int _0^\infty {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \left({\mu _k}{e^{{p_k}\tau }} + \mu _k^\dagger {e^{p_k^\dagger \tau }}\right){A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t - \tau )} {\rm d}\tau . \end{align}

\begin{align} {A^{\textit {out}}}(t + \Delta t) = ({C_0} - 1){A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t) + \int _0^\infty {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} \left({\mu _k}{e^{{p_k}\tau }} + \mu _k^\dagger {e^{p_k^\dagger \tau }}\right){A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t - \tau )} {\rm d}\tau . \end{align}

Here, the convolution in (2.12) can be written as

![]() $G_k^{\textit {in}}$

, that is

$G_k^{\textit {in}}$

, that is

According to Fung & Ju (Reference Fung and Ju2004), (2.13) can be calculated by a recursive scheme

Here,

![]() ${z_k} = {e^{{p_k}\Delta t}}$

, and

${z_k} = {e^{{p_k}\Delta t}}$

, and

\begin{align} \left \{ \begin{aligned} w_{k0} &= \frac {z_k - 1}{p_k^2 \Delta t^2} - \frac {1}{p_k \Delta t}, \\ w_{k1} &= -\frac {z_k - 1}{p_k^2 \Delta t^2} + \frac {z_k}{p_k \Delta t}. \end{aligned} \right . \end{align}

\begin{align} \left \{ \begin{aligned} w_{k0} &= \frac {z_k - 1}{p_k^2 \Delta t^2} - \frac {1}{p_k \Delta t}, \\ w_{k1} &= -\frac {z_k - 1}{p_k^2 \Delta t^2} + \frac {z_k}{p_k \Delta t}. \end{aligned} \right . \end{align}

With a first-order approximation (Scalo et al. Reference Scalo, Bodart and Lele2015), the ingoing wave at

![]() $t + \Delta t$

can be expressed by

$t + \Delta t$

can be expressed by

Then, combining (2.12) and (2.16) gives rise to the fluctuating wall-normal velocity at

![]() $t + \Delta t$

$t + \Delta t$

\begin{align} v'(t + \Delta t) & = \big ( {{A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t) + {A^{out}}(t + \Delta t)} \big )/2 \nonumber \\ & = {\textrm {Re}}\left ( {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} G_k^{\textit {in}}(t + \Delta t)} \right ) + {C_0}{A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t). \end{align}

\begin{align} v'(t + \Delta t) & = \big ( {{A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t) + {A^{out}}(t + \Delta t)} \big )/2 \nonumber \\ & = {\textrm {Re}}\left ( {\mathop \sum \limits _{k = 1}^{{n_0}} G_k^{\textit {in}}(t + \Delta t)} \right ) + {C_0}{A^{\textit {in}}}(t + \Delta t). \end{align}

Finally, the pressure fluctuation at

![]() $t + \Delta t$

is

$t + \Delta t$

is

In the simulation where the metasurface exists locally, the pressure and normal velocity on the wall are updated based on (2.17) and (2.18) at each time step, and the incoming wave amplitude

![]() ${A^{\textit {in}}}(t)$

is initialised using (2.4). The density is calculated by the updated pressure from the equation of state for perfect gases. Although the TDIBC was derived from linear approximations, it remains valid for the nonlinear disturbance dynamics in our system due to the strongly viscous-dominated regime inside the porous medium (Chen & Scalo Reference Chen and Scalo2021a

; Sousa et al. Reference Sousa, Wartemann and Wagner2024).

${A^{\textit {in}}}(t)$

is initialised using (2.4). The density is calculated by the updated pressure from the equation of state for perfect gases. Although the TDIBC was derived from linear approximations, it remains valid for the nonlinear disturbance dynamics in our system due to the strongly viscous-dominated regime inside the porous medium (Chen & Scalo Reference Chen and Scalo2021a

; Sousa et al. Reference Sousa, Wartemann and Wagner2024).

2.3. Resolvent analysis

The resolvent analysis provides the most energetic response of the flow field due to per unit energy of external forcing. Substituting (2.2) into (2.1), and subtracting the base-flow equation yield the following form:

Considering a small-amplitude forcing term to study the instability, one may obtain

where matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D63C}$

is the Jacobian matrix constituted by the base-flow variables. The harmonic assumption is utilised for the small-amplitude perturbation vector

$\unicode{x1D63C}$

is the Jacobian matrix constituted by the base-flow variables. The harmonic assumption is utilised for the small-amplitude perturbation vector

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat U}$

is the complex eigenfunction,

$\boldsymbol{\hat U}$

is the complex eigenfunction,

![]() $\beta$

is the spanwise wavenumber,

$\beta$

is the spanwise wavenumber,

![]() $\omega$

is the angular frequency and

$\omega$

is the angular frequency and

![]() ${\textrm {c}}{\textrm {.c}}.$

denotes complex conjugate. Similarly, the harmonic forcing can be written as

${\textrm {c}}{\textrm {.c}}.$

denotes complex conjugate. Similarly, the harmonic forcing can be written as

Substituting (2.21) and (2.22) into (2.20) gives

where

![]() $\unicode{x1D64D}$

represents the response matrix, indicating the relationship between the external forcing and the linear response of the system. Here, the identity operator is represented by

$\unicode{x1D64D}$

represents the response matrix, indicating the relationship between the external forcing and the linear response of the system. Here, the identity operator is represented by

![]() $\unicode{x1D644}$

. In resolvent analysis, the maximal amplification of the energy, i.e. the optimal gain

$\unicode{x1D644}$

. In resolvent analysis, the maximal amplification of the energy, i.e. the optimal gain

![]() $\sigma ^2$

, is sought in the parameter space of (

$\sigma ^2$

, is sought in the parameter space of (

![]() $\omega$

,

$\omega$

,

![]() $\beta$

). The optimal gain is defined by the energy ratio of the output (response) to the input (forcing) of the system

$\beta$

). The optimal gain is defined by the energy ratio of the output (response) to the input (forcing) of the system

\begin{align} {\sigma ^2}(\beta ,\omega ) = \mathop {\max }\limits _{{\boldsymbol{\hat f}}} \frac {{{{\big \| {{\boldsymbol{\hat U}}} \big \|}_E}}}{{{{\big \| {{\unicode{x1D63D}\boldsymbol{\hat f}}} \big \|}_E}}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} {\sigma ^2}(\beta ,\omega ) = \mathop {\max }\limits _{{\boldsymbol{\hat f}}} \frac {{{{\big \| {{\boldsymbol{\hat U}}} \big \|}_E}}}{{{{\big \| {{\unicode{x1D63D}\boldsymbol{\hat f}}} \big \|}_E}}}. \end{align}

In this study, Chu’s energy (Chu & Kovasznay Reference Chu and Kovásznay1958) is employed to calculate the energy norm

\begin{align} {\big \| {{\boldsymbol{\hat U}}} \big \|_E} = \iint \limits _{\varOmega } {{{\boldsymbol{U}}^\bot }{\unicode{x1D648}\boldsymbol{\hat U}}}{\rm d}x{\rm d}y, \end{align}

\begin{align} {\big \| {{\boldsymbol{\hat U}}} \big \|_E} = \iint \limits _{\varOmega } {{{\boldsymbol{U}}^\bot }{\unicode{x1D648}\boldsymbol{\hat U}}}{\rm d}x{\rm d}y, \end{align}

where

![]() $\varOmega$

represents the computational domain for resolvent analysis, the superscript

$\varOmega$

represents the computational domain for resolvent analysis, the superscript

![]() $ \bot$

refers to the conjugate transpose and

$ \bot$

refers to the conjugate transpose and

![]() $\unicode{x1D648}$

is the weight operator given by Bugeat et al. (Reference Bugeat, Chassaing, Robinet and Sagaut2019). A local energy integral in a dimensionless form is defined by

$\unicode{x1D648}$

is the weight operator given by Bugeat et al. (Reference Bugeat, Chassaing, Robinet and Sagaut2019). A local energy integral in a dimensionless form is defined by

The optimisation problem in (2.24) can be transformed into an eigenvalue problem with respect to

![]() $\sigma ^2$

, as demonstrated by Sipp & Marquet (Reference Sipp and Marquet2013). The resulting discrete eigenvalue problem is solved using ARPACK software for given values of

$\sigma ^2$

, as demonstrated by Sipp & Marquet (Reference Sipp and Marquet2013). The resulting discrete eigenvalue problem is solved using ARPACK software for given values of

![]() $\beta$

and

$\beta$

and

![]() $\omega$

associated with the regular mode (Sorensen et al. Reference Sorensen, Lehoucq, Yang and Maschhoff1996). Additional details regarding the resolvent analysis solver and the associated validation cases can be found in Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Cao and Guo2023) and Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Liu, Zhao, Hao and Wen2023b

).

$\omega$

associated with the regular mode (Sorensen et al. Reference Sorensen, Lehoucq, Yang and Maschhoff1996). Additional details regarding the resolvent analysis solver and the associated validation cases can be found in Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Cao and Guo2023) and Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Liu, Zhao, Hao and Wen2023b

).

2.4. Linear stability theory and parabolised stability equation

To identify transient growth and modal growth captured by resolvent analysis, LST and parabolised stability equation (PSE) are employed. The PSE further considers the non-parallel effect compared with LST. Specifically, the LST provides the initial inlet profiles (eigenfunctions) for the PSE, and the PSE can obtain the non-local evolution of eigenmodes, including the first and second modes of interest here. In PSE, the disturbance

![]() $\boldsymbol{\psi '}$

is expressed by

$\boldsymbol{\psi '}$

is expressed by

where the vector

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\psi }} = {(\rho ,u,v,w,T)^{\textrm {T}}}$

,

${\boldsymbol{\psi }} = {(\rho ,u,v,w,T)^{\textrm {T}}}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\hat \psi }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\hat \psi }$

and

![]() $\alpha$

are the shape function and the complex streamwise wavenumber, respectively, and

$\alpha$

are the shape function and the complex streamwise wavenumber, respectively, and

![]() $x_0$

is the initialisation location of PSE marching. Substituting (2.27) into (2.19) and dropping the forcing terms give rise to the PSE governing equation

$x_0$

is the initialisation location of PSE marching. Substituting (2.27) into (2.19) and dropping the forcing terms give rise to the PSE governing equation

The effects of the locally parallel flow, the non-parallel base flow, the non-local shape function and the streamwise-varying wavenumber are absorbed in the base-flow-related operators

![]() ${\unicode{x1D647}}_0$

,

${\unicode{x1D647}}_0$

,

![]() ${\unicode{x1D647}}_1$

,

${\unicode{x1D647}}_1$

,

![]() ${\unicode{x1D647}}_2$

and

${\unicode{x1D647}}_2$

and

![]() ${\unicode{x1D647}}_3$

, respectively. Detailed expressions of these operators can be found in Paredes (Reference Paredes2014). An eigenvalue problem is solved in LST when keeping only the local operator

${\unicode{x1D647}}_3$

, respectively. Detailed expressions of these operators can be found in Paredes (Reference Paredes2014). An eigenvalue problem is solved in LST when keeping only the local operator

![]() ${\unicode{x1D647}}_0$

in (2.28). The calculation is performed by an in-house code CHASES, which integrates the LST, linear parabolised stability equation (LPSE), nonlinear parabolised stability equation and sensitivity analyses. The code has been validated by a series of cases for LST and LPSE compared with both theoretical (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Gao and Jiang2020, Guo et al. Reference Guo, Gao and Jiang2021, Guo et al. Reference Guo, Shi, Gao, Jiang, Lee and Wen2022b) and DNS (Cao, Hao & Guo Reference Cao, Hao, Guo, Wen and Klioutchnikov2023; Hao et al. Reference Hao, Cao and Guo2023; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

) results. The detailed formulation and the numerical method can be found in the references (Paredes Reference Paredes2014; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

).

${\unicode{x1D647}}_0$

in (2.28). The calculation is performed by an in-house code CHASES, which integrates the LST, linear parabolised stability equation (LPSE), nonlinear parabolised stability equation and sensitivity analyses. The code has been validated by a series of cases for LST and LPSE compared with both theoretical (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Gao and Jiang2020, Guo et al. Reference Guo, Gao and Jiang2021, Guo et al. Reference Guo, Shi, Gao, Jiang, Lee and Wen2022b) and DNS (Cao, Hao & Guo Reference Cao, Hao, Guo, Wen and Klioutchnikov2023; Hao et al. Reference Hao, Cao and Guo2023; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

) results. The detailed formulation and the numerical method can be found in the references (Paredes Reference Paredes2014; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

).

2.5. Case initialisation for direct numerical simulation

To explore the effect of the acoustic metasurface in hypersonic transitional flows, three cases subject to the same forcing yet different wall boundary conditions are considered here. In the present Mach 6 state, Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a ) reported two dominant optimal disturbances: a low-frequency oblique wave and a high-frequency planar wave. These two types of forcing are considered in the transition simulation. The mathematical form of the forcing in DNS is given by

where

![]() $x_0$

= 0.04 m is the specified forcing location, and subscripts ‘

$x_0$

= 0.04 m is the specified forcing location, and subscripts ‘

![]() $p$

’ and ‘

$p$

’ and ‘

![]() $o$

’ represent the optimal planar wave and oblique wave obtained by resolvent analysis, respectively. According to our previous study (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

), the additional background noise term produces a neglectable effect on the flow field, which is thus not considered here. The planar-wave forcing is detailed as

$o$

’ represent the optimal planar wave and oblique wave obtained by resolvent analysis, respectively. According to our previous study (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

), the additional background noise term produces a neglectable effect on the flow field, which is thus not considered here. The planar-wave forcing is detailed as

where

![]() $\varepsilon$

is the amplitude coefficient, and

$\varepsilon$

is the amplitude coefficient, and

![]() $\beta _p = 0$

for the planar wave employed . A pair of oblique waves with an opposite spanwise wavenumber is employed, which is expressed by

$\beta _p = 0$

for the planar wave employed . A pair of oblique waves with an opposite spanwise wavenumber is employed, which is expressed by

In all transition simulation cases, the initial amplitude

![]() $(\rho u)'_{\textit{max}}$

= 0.002 remains the same for planar wave

$(\rho u)'_{\textit{max}}$

= 0.002 remains the same for planar wave

![]() $({\omega _p},{\beta _p})$

and a pair of oblique waves

$({\omega _p},{\beta _p})$

and a pair of oblique waves

![]() $({\omega _o}, \pm {\beta _o})$

at

$({\omega _o}, \pm {\beta _o})$

at

![]() $x$

= 0.045 m. This set-up excites the first mode and second mode of equal importance near the forcing. In this case, strong mutual interactions can occur with the presence of two primary instabilities. As reported by Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

), the resulting nonlinear mechanism (combination resonance) is independent of both the initial amplitude ratio and the absolute amplitude of the oblique and planar waves. Therefore, this study focuses on one specified set-up of wave amplitudes without loss of generality.

$x$

= 0.045 m. This set-up excites the first mode and second mode of equal importance near the forcing. In this case, strong mutual interactions can occur with the presence of two primary instabilities. As reported by Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

), the resulting nonlinear mechanism (combination resonance) is independent of both the initial amplitude ratio and the absolute amplitude of the oblique and planar waves. Therefore, this study focuses on one specified set-up of wave amplitudes without loss of generality.

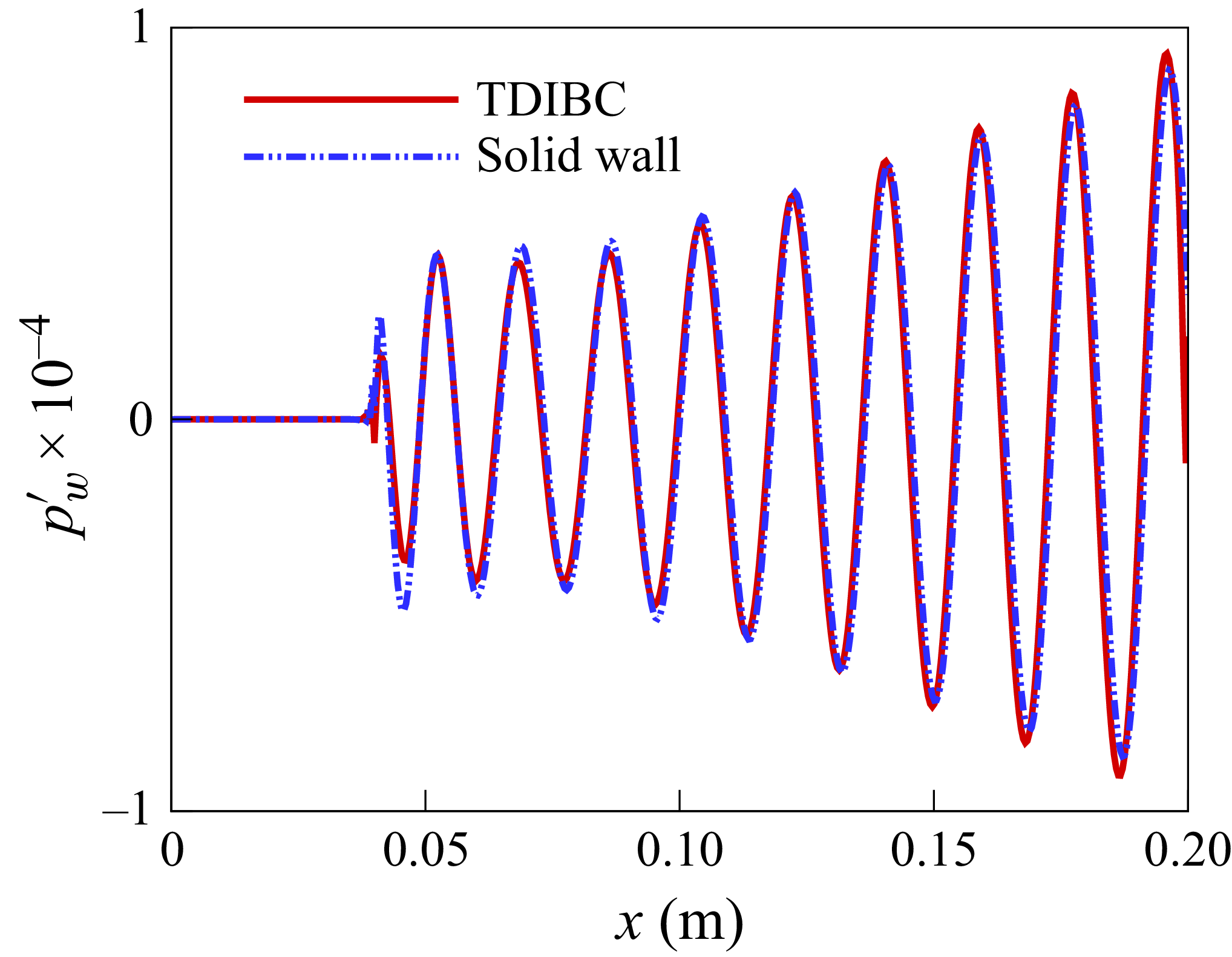

The wall boundary conditions for DNS cases are presented in table 1. The boundary condition is of primary interest in this study. In case 1, only the solid-wall boundary condition is employed. For case 2 with the acoustic metasurface, TDIBC is employed starting from

![]() $x$

= 0.115 m to the end of the computational domain, i.e.

$x$

= 0.115 m to the end of the computational domain, i.e.

![]() $x$

= 0.6 m. It is important to note that

$x$

= 0.6 m. It is important to note that

![]() $x = 0.115$

m corresponds to the neutral point of the optimal plane wave (10, 0), downstream of which the modal growth begins. In case 3, during the late stage of the transitional flow (

$x = 0.115$

m corresponds to the neutral point of the optimal plane wave (10, 0), downstream of which the modal growth begins. In case 3, during the late stage of the transitional flow (

![]() $x$

>0.34m), the TDIBC is replaced by solid walls to mitigate undesirable higher wall friction and flux in the late transitional stage. The selection of

$x$

>0.34m), the TDIBC is replaced by solid walls to mitigate undesirable higher wall friction and flux in the late transitional stage. The selection of

![]() $x$

= 0.34 m in case 3 also considers the modal growth region of the second mode. As illustrated in figure 2 (

$x$

= 0.34 m in case 3 also considers the modal growth region of the second mode. As illustrated in figure 2 (

![]() $b$

), the modal growth of the optimal plane wave (10, 0) terminates at approximately

$b$

), the modal growth of the optimal plane wave (10, 0) terminates at approximately

![]() $x$

= 0.34 m. A detailed discussion and explanation will be provided in the subsequent sections.

$x$

= 0.34 m. A detailed discussion and explanation will be provided in the subsequent sections.

Table 1. Streamwise range of different wall boundary conditions for transitional DNS cases.

In the DNS, the computational domain ranges from

![]() $x$

= 0 to

$x$

= 0 to

![]() $x$

= 0.6 m. The number of the grid points is

$x$

= 0.6 m. The number of the grid points is

![]() $3060 \times 260 \times 60$

, denoting the grid numbers in the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively. The corresponding dimensionless grid spacings are

$3060 \times 260 \times 60$

, denoting the grid numbers in the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively. The corresponding dimensionless grid spacings are

![]() $\Delta {x^ + \approx }$

3.13,

$\Delta {x^ + \approx }$

3.13,

![]() $\Delta z^ + \approx$

5.9 and

$\Delta z^ + \approx$

5.9 and

![]() $\Delta y_{\textit{min}}^ + \approx$

0.30, which are evaluated based on the procedure described by Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Shi, Gao, Jiang, Lee and Wen2022a

, Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

). Grid convergence of the amplitude evolution of the optimal disturbances has been confirmed (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

). A good agreement is also reached between the DNS and the stability analysis.

$\Delta y_{\textit{min}}^ + \approx$

0.30, which are evaluated based on the procedure described by Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Shi, Gao, Jiang, Lee and Wen2022a

, Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

). Grid convergence of the amplitude evolution of the optimal disturbances has been confirmed (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

). A good agreement is also reached between the DNS and the stability analysis.

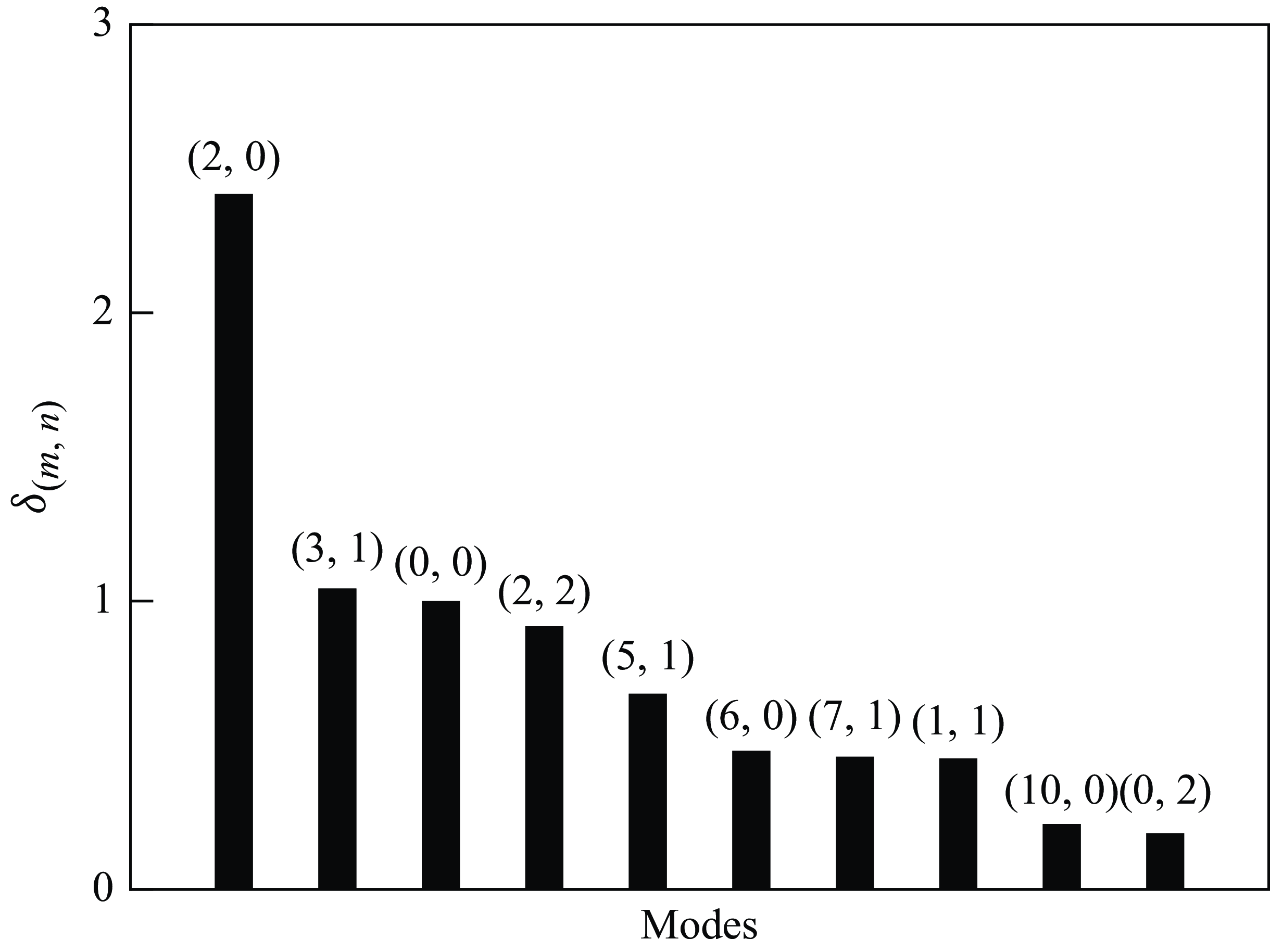

2.6. Bispectral mode decomposition

Based on the DNS data, bi-Fourier analysis and bispectral analysis are performed. Bi-Fourier analysis demonstrates the significant amplitude evolution for multiple disturbances, while bi-spectral decomposition reveals the energy-transfer mechanism. The BMD method developed by Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2020) is employed to elucidate the triadic interactions arising from quadratic nonlinearities in the Navier–Stokes equations, which govern energy transfer between scales in the flow. As shown in Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2020), BMD examines triadic interactions originating from the quadratic nonlinearity inherent in the Navier–Stokes equations. The perturbation dynamics about a base flow is governed by

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{q}'(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

represents the flow perturbation (typically velocity components or pressure fluctuations),

$\boldsymbol{q}'(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

represents the flow perturbation (typically velocity components or pressure fluctuations),

![]() $\unicode{x1D647}$

is the linear operator and

$\unicode{x1D647}$

is the linear operator and

![]() $\unicode{x1D64C}(\boldsymbol{\cdot },\boldsymbol{\cdot })$

denotes the quadratic nonlinearity arising from terms like

$\unicode{x1D64C}(\boldsymbol{\cdot },\boldsymbol{\cdot })$

denotes the quadratic nonlinearity arising from terms like

![]() $(\boldsymbol{u}' \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla })\boldsymbol{u}'$

in the convective term.

$(\boldsymbol{u}' \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla })\boldsymbol{u}'$

in the convective term.

The expectation operator

![]() $E[\boldsymbol{\cdot }]$

, central to BMD’s statistical formulation, performs ensemble averaging over independent flow realisations. Specifically, BMD identifies phase-coupled frequency triads

$E[\boldsymbol{\cdot }]$

, central to BMD’s statistical formulation, performs ensemble averaging over independent flow realisations. Specifically, BMD identifies phase-coupled frequency triads

![]() $\{f_k, f_l, f_m\}$

satisfying

$\{f_k, f_l, f_m\}$

satisfying

![]() $f_m = f_k \pm f_l$

through the bispectrum. The bispectrum is defined as the double Fourier transform of the third-order moment

$f_m = f_k \pm f_l$

through the bispectrum. The bispectrum is defined as the double Fourier transform of the third-order moment

![]() $E[q(t)q(t-{\tau _k})q(t-{\tau _l})]$

$E[q(t)q(t-{\tau _k})q(t-{\tau _l})]$

where

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}(\boldsymbol{x},f)$

is the Fourier transform of

$\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}(\boldsymbol{x},f)$

is the Fourier transform of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{q}}(\boldsymbol{x},f)$

and

${\boldsymbol{q}}(\boldsymbol{x},f)$

and

![]() $\dagger$

indicates complex conjugate. The classical bispectrum

$\dagger$

indicates complex conjugate. The classical bispectrum

![]() $S_{\textit{qqq}}$

serves as a conceptual foundation for detecting quadratic phase coupling. Its spatial generalisation, the mode bispectrum

$S_{\textit{qqq}}$

serves as a conceptual foundation for detecting quadratic phase coupling. Its spatial generalisation, the mode bispectrum

![]() $\phi$

, is achieved by replacing the temporal expectation

$\phi$

, is achieved by replacing the temporal expectation

![]() $E[\boldsymbol{\cdot }]$

with a spatially weighted ensemble average over Fourier realisations, thereby extending pointwise statistics to coherent structures. For multidimensional datasets, BMD constructs the bispectral density tensor

$E[\boldsymbol{\cdot }]$

with a spatially weighted ensemble average over Fourier realisations, thereby extending pointwise statistics to coherent structures. For multidimensional datasets, BMD constructs the bispectral density tensor

with

![]() $\unicode{x1D652}$

containing spatial quadrature weights,

$\unicode{x1D652}$

containing spatial quadrature weights,

![]() $N_{\textit{blk}}$

the number of data blocks and

$N_{\textit{blk}}$

the number of data blocks and

![]() $\hat {\unicode{x1D64C}}_{k \circ l} = \hat {\unicode{x1D64C}}_k \circ \hat {\unicode{x1D64C}}_l$

being the Hadamard product of Fourier realisations. Here, superscript

$\hat {\unicode{x1D64C}}_{k \circ l} = \hat {\unicode{x1D64C}}_k \circ \hat {\unicode{x1D64C}}_l$

being the Hadamard product of Fourier realisations. Here, superscript

![]() $H$

denotes the Hermitian transpose (conjugate transpose). The matrix

$H$

denotes the Hermitian transpose (conjugate transpose). The matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D64C}$

organises the Fourier coefficients of

$\unicode{x1D64C}$

organises the Fourier coefficients of

![]() $\boldsymbol{q}'(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

in a block form, where each column contains a realisation of

$\boldsymbol{q}'(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

in a block form, where each column contains a realisation of

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}(\boldsymbol{x},f)$

for spectral estimation. The dominant triadic interactions are identified by maximising the numerical radius of

$\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}(\boldsymbol{x},f)$

for spectral estimation. The dominant triadic interactions are identified by maximising the numerical radius of

![]() $\unicode{x1D63F}$

, which involves solving the eigenvalue problem for the Hermitian matrix

$\unicode{x1D63F}$

, which involves solving the eigenvalue problem for the Hermitian matrix

![]() $\unicode{x1D643}(\theta ) = {1}/{2}(e^{i\theta } \unicode{x1D63F} + e^{-i\theta } \unicode{x1D63F}^H)$

.The complex mode bispectrum

$\unicode{x1D643}(\theta ) = {1}/{2}(e^{i\theta } \unicode{x1D63F} + e^{-i\theta } \unicode{x1D63F}^H)$

.The complex mode bispectrum

![]() $\phi (f_k, f_l)$

, which is defined as the maximum numerical radius of

$\phi (f_k, f_l)$

, which is defined as the maximum numerical radius of

![]() $\unicode{x1D63F}$

, quantifies the triad interaction strength through its magnitude

$\unicode{x1D63F}$

, quantifies the triad interaction strength through its magnitude

![]() $|\phi |$

. The magnitude of the mode bispectrum scales with the product of the absolute amplitudes of the triad components. This preserves the energy-transfer scaling inherent to quadratic nonlinearities.

$|\phi |$

. The magnitude of the mode bispectrum scales with the product of the absolute amplitudes of the triad components. This preserves the energy-transfer scaling inherent to quadratic nonlinearities.

The BMD method and open-source code proposed by Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2020) were employed in this study, and a detailed introduction for the formulation and definition can be found in Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2020).

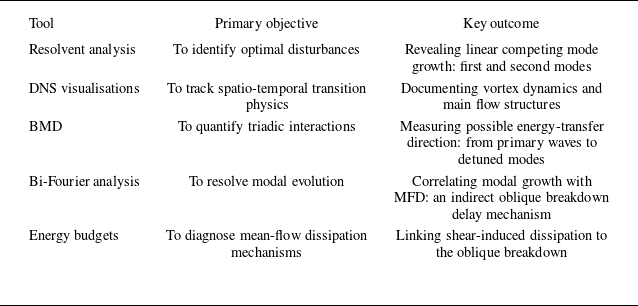

2.7. A summary of analytical techniques

The present analysis framework systematically combines existing techniques to elucidate the effects of the metasurface across different transition stages. The investigation progresses from linear mechanisms, in which the resolvent analysis identifies optimal disturbances and LST/PSE quantifies modal growth rates, to the nonlinear transition dynamics captured via DNS visualisations of vortex formation and bi-Fourier quantifications of mode evolutions with or without the metasurface. The complete energy pathway is resolved through BMD of triadic interactions and energy budget diagnosis of dissipation mechanisms. Crucially, DNS visualisations provide physical grounding for spectral analyses, with instantaneous flow structures associated with BMD-detected triadic interactions and streak spacing matching bi-Fourier analysis. This represents the first coupled application of BMD and hypersonic DNS to resolve metasurface-modified triads while maintaining a direct correlation between flow structures and spectral-space dynamics.

3. Linear instability stage

In this section, the linear stage of the dominant primary instabilities and the effect of the acoustic metasurface are of interest. The multi-pole fitting result is used in the TDIBC to model the acoustic metasurface. The correctness of the embedded TDIBC code is examined in comparison with the result obtained by directly meshing the cavities. The resolvent analysis is employed to capture the optimal response of the boundary layer. The effect of the metasurface on single-frequency disturbances in the low- and high-frequency ranges is demonstrated. The preferred starting location of TDIBC is further discussed.

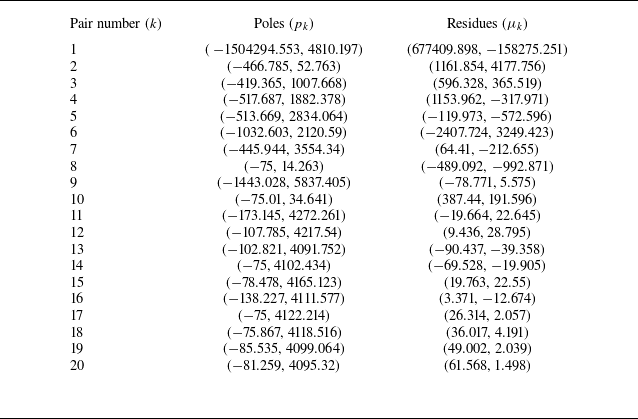

3.1. Fitting result of softness and validation of TDIBC

In this study, the acoustic metasurface consists of uniformly distributed spanwise rectangular cavities. The geometric parameters of these cavities were optimised (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Liu, Wen and Cheng2018a

) to maximise acoustic absorption performance. Regarding the parameters employed, the dimensionless half-width

![]() $b/{L_{\textit {ref}}} = 0.196$

, the unit-cell periods are

$b/{L_{\textit {ref}}} = 0.196$

, the unit-cell periods are

![]() $s/{L_{\textit {ref}}} = 0.52$

and depth

$s/{L_{\textit {ref}}} = 0.52$

and depth

![]() $H/{L_{\textit {ref}}} = 1.642$

are all consistent with those in Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Wen, Long, Tian, Zhou and Wu2019). The geometric setting corresponds to a porosity of

$H/{L_{\textit {ref}}} = 1.642$

are all consistent with those in Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Wen, Long, Tian, Zhou and Wu2019). The geometric setting corresponds to a porosity of

![]() $\varphi = {{2b} \mathord {\left /{\vphantom {{2b} s}} \right .} s} = 0.75$

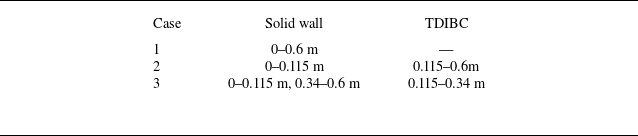

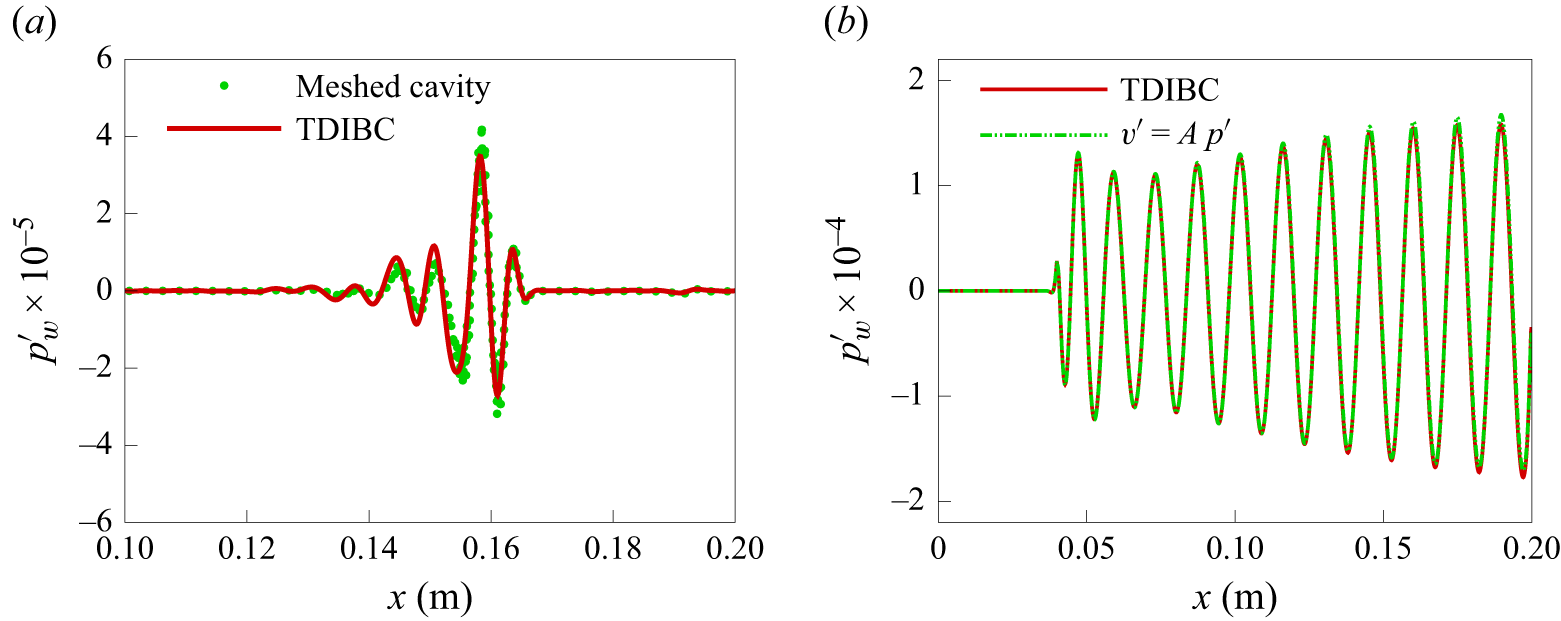

. These parameters were designed to control the second mode and have demonstrated their evident effectiveness in both LST and two-dimensional DNS (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wen, Long, Tian, Zhou and Wu2019). Figure 1 compares the softness derived from a fitting procedure based on the theoretical model, which considers high-order diffraction (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Liu, Wen and Cheng2018a

). The fitting result was based on the method proposed by Douasbin et al. (Reference Douasbin, Scalo, Selle and Poinsot2018) using (2.7), which employs

$\varphi = {{2b} \mathord {\left /{\vphantom {{2b} s}} \right .} s} = 0.75$

. These parameters were designed to control the second mode and have demonstrated their evident effectiveness in both LST and two-dimensional DNS (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wen, Long, Tian, Zhou and Wu2019). Figure 1 compares the softness derived from a fitting procedure based on the theoretical model, which considers high-order diffraction (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Liu, Wen and Cheng2018a

). The fitting result was based on the method proposed by Douasbin et al. (Reference Douasbin, Scalo, Selle and Poinsot2018) using (2.7), which employs

![]() $C_0$

= −0.05 and the poles and residues shown in Appendix A. It is indicated that the fitting result agrees well with the theoretical model within a broadband frequency domain. This agreement enables the accurate simulation subject to both high- and low-frequency disturbances using the acoustic metasurface. The comparison among the cases with TDIBC, with meshed cavities and with a constant wall impedance model (

$C_0$

= −0.05 and the poles and residues shown in Appendix A. It is indicated that the fitting result agrees well with the theoretical model within a broadband frequency domain. This agreement enables the accurate simulation subject to both high- and low-frequency disturbances using the acoustic metasurface. The comparison among the cases with TDIBC, with meshed cavities and with a constant wall impedance model (

![]() $v' = Ap'$

, and

$v' = Ap'$

, and

![]() $A$

is a constant acoustic admittance), can be found in Appendix B. A good agreement is reached, validating the reliability of the TDIBC code in this study.

$A$

is a constant acoustic admittance), can be found in Appendix B. A good agreement is reached, validating the reliability of the TDIBC code in this study.

Figure 1. Comparison of wall softness between the reference impedance model (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Liu, Wen and Cheng2018a ) and the multi-pole fitting results (present).

Figure 2. (

![]() $a$

) Contours of optimal gain in the parameter space of the spanwise wavenumber and the angular frequency, where

$a$

) Contours of optimal gain in the parameter space of the spanwise wavenumber and the angular frequency, where

![]() ${\omega _0}{L_{\textit {ref}}}/{u_\infty }$

= 0.1 and

${\omega _0}{L_{\textit {ref}}}/{u_\infty }$

= 0.1 and

![]() ${\beta _0}{L_{\textit {ref}}}$

= 0.8. (

${\beta _0}{L_{\textit {ref}}}$

= 0.8. (

![]() $b$

) Comparison of

$b$

) Comparison of

![]() $N$

-factors between PSE and resolvent analysis. Here,

$N$

-factors between PSE and resolvent analysis. Here,

![]() $N$

-factor curves of PSE are shifted to be compared with resolvent analysis.

$N$

-factor curves of PSE are shifted to be compared with resolvent analysis.

3.2. Result of stability analysis

In resolvent analysis, the interval 0–0.5 m is utilised for the optimisation problem, and the forcing is introduced at

![]() $x_0$

= 0.04 m. The

$x_0$

= 0.04 m. The

![]() $N$

-factor is defined by

$N$

-factor is defined by

![]() $N = 0.5\log ({{{E_{\textit{Chu}}}} \mathord {\left /{\vphantom {{{E_{\textit{Chu}}}} {{E_{\textit {Chu,0}}}}}} \right .} {{E_{Chu,0}}}})$

, where

$N = 0.5\log ({{{E_{\textit{Chu}}}} \mathord {\left /{\vphantom {{{E_{\textit{Chu}}}} {{E_{\textit {Chu,0}}}}}} \right .} {{E_{Chu,0}}}})$

, where

![]() ${E_{\textit {Chu,0}}}$

is measured at

${E_{\textit {Chu,0}}}$

is measured at

![]() $x$

=

$x$

=

![]() $x_0$

and

$x_0$

and

![]() $N$

is 0 at

$N$

is 0 at

![]() $x_0$

.

$x_0$

.

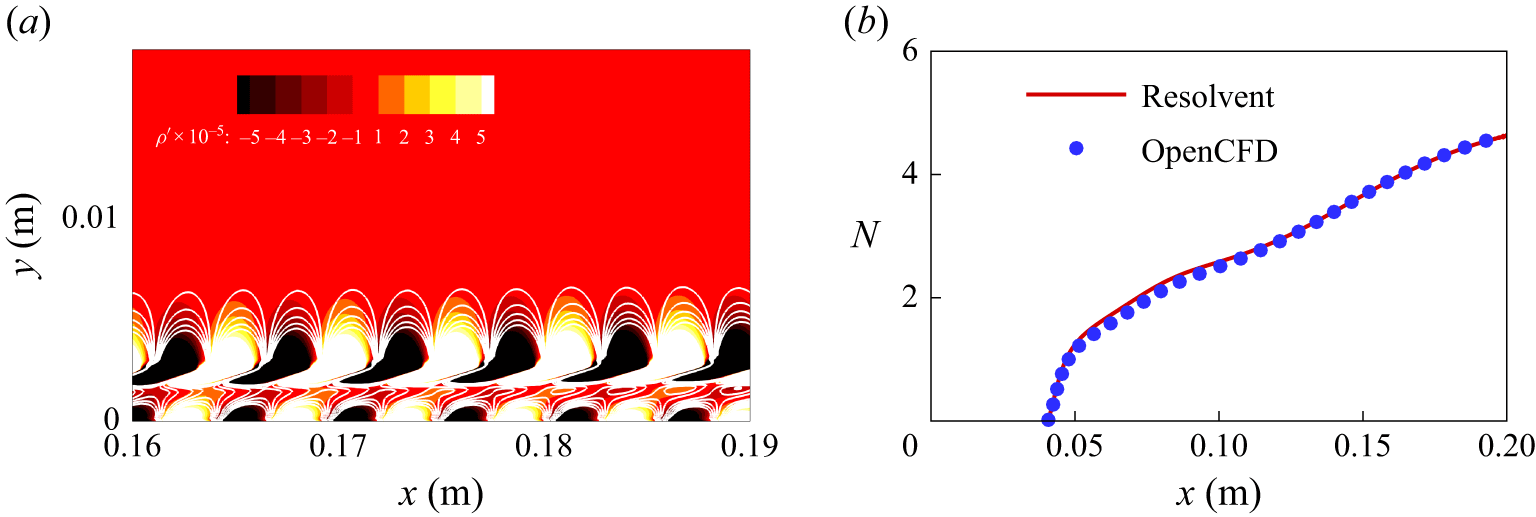

The gain contour for a wide range of spanwise wavenumbers and angular frequencies is shown in figure 2(

![]() $a$

). Clearly, the low-frequency oblique wave related to the first mode (

$a$

). Clearly, the low-frequency oblique wave related to the first mode (

![]() $\omega /{\omega _0}$

,

$\omega /{\omega _0}$

,

![]() $\beta /{\beta _0}$

) = (3, 1) and the high-frequency planar wave related to the second mode (

$\beta /{\beta _0}$

) = (3, 1) and the high-frequency planar wave related to the second mode (

![]() $\omega /{\omega _0}$

,

$\omega /{\omega _0}$

,

![]() $\beta /{\beta _0}$

) = (10, 0) are prominent in the gain contour. In this study,

$\beta /{\beta _0}$

) = (10, 0) are prominent in the gain contour. In this study,

![]() $\omega /{\omega _0}$

= 10 corresponds to a dimensional frequency of 125.8 kHz, which has also been shown to be the peak frequency in the energy spectrum under the considered experiment condition (Bountin, Chimitov & Maslov Reference Bountin, Chimitov, Maslov, Novikov, Egorov, Fedorov and Utyuzhnikov2013). For brevity, the optimal response for a Fourier mode with

$\omega /{\omega _0}$

= 10 corresponds to a dimensional frequency of 125.8 kHz, which has also been shown to be the peak frequency in the energy spectrum under the considered experiment condition (Bountin, Chimitov & Maslov Reference Bountin, Chimitov, Maslov, Novikov, Egorov, Fedorov and Utyuzhnikov2013). For brevity, the optimal response for a Fourier mode with

![]() $\omega /{\omega _0}$

= 10 and

$\omega /{\omega _0}$

= 10 and

![]() $\beta /{\beta _0}$

= 0 is referred to as mode (10, 0), and the same applies to other optimal disturbances. In the following DNS, the three-dimensional transition to turbulence will be initiated using the optimal forcings determined by resolvent analysis. As shown in figure 2(

$\beta /{\beta _0}$

= 0 is referred to as mode (10, 0), and the same applies to other optimal disturbances. In the following DNS, the three-dimensional transition to turbulence will be initiated using the optimal forcings determined by resolvent analysis. As shown in figure 2(

![]() $b$

), the optimal response captured by resolvent analysis undergoes a transient growth downstream of the forcing location, which cannot be captured in PSE when a purely modal profile is introduced at the inlet. The transient-growth region is between the forcing location and the position where the growth rate

$b$

), the optimal response captured by resolvent analysis undergoes a transient growth downstream of the forcing location, which cannot be captured in PSE when a purely modal profile is introduced at the inlet. The transient-growth region is between the forcing location and the position where the growth rate

![]() ${{\rm d}N} \mathord {\left /{\vphantom {{{\rm d}N} {{\rm d}x}}} \right .} {{\rm d}x}$

from the resolvent analysis converges with that from the PSE. For instance, the interval

${{\rm d}N} \mathord {\left /{\vphantom {{{\rm d}N} {{\rm d}x}}} \right .} {{\rm d}x}$

from the resolvent analysis converges with that from the PSE. For instance, the interval

![]() $x$

$x$

![]() $ \in$

[0.04 m, 0.115 m] corresponds to the transient-growth region of Fourier mode (10, 0). The PSE results indicate that modal growth begins at approximately

$ \in$

[0.04 m, 0.115 m] corresponds to the transient-growth region of Fourier mode (10, 0). The PSE results indicate that modal growth begins at approximately

![]() $x$

= 0.115 m and ends at approximately

$x$

= 0.115 m and ends at approximately

![]() $x$

= 0.34 m for (10, 0), as shown in figure 2(

$x$

= 0.34 m for (10, 0), as shown in figure 2(

![]() $b$

). As for the optimal oblique wave (3, 1), its

$b$

). As for the optimal oblique wave (3, 1), its

![]() $N$

-factor exceeds that of the planar wave (10, 0) downstream. This is due to a longer growth region of (3, 1), despite a lower maximum growth rate.

$N$

-factor exceeds that of the planar wave (10, 0) downstream. This is due to a longer growth region of (3, 1), despite a lower maximum growth rate.

In the numerical simulation, both modal and non-modal growths are included. Given the broadband nature of free-stream disturbances in wind tunnels and at realistic flight conditions, both the first and second modes should be considered in the investigation of hypersonic boundary-layer instability and transition. In this study, optimal disturbances

![]() $({\omega _p}, {\beta _p})$

= (10, 0) and

$({\omega _p}, {\beta _p})$

= (10, 0) and

![]() $({\omega _o}, {\beta _o})$

= (3, 1) were utilised to initiate the unsteady flow for cases listed in table 1. These disturbances enable complicated nonlinear mode–mode interactions and spectral broadening rapidly (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

). The two are also representative building blocks of the various primary instabilities with different frequencies and wavenumbers. The selection of only two of them enables the fundamental observation of the excited secondary instabilities downstream.

$({\omega _o}, {\beta _o})$

= (3, 1) were utilised to initiate the unsteady flow for cases listed in table 1. These disturbances enable complicated nonlinear mode–mode interactions and spectral broadening rapidly (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

). The two are also representative building blocks of the various primary instabilities with different frequencies and wavenumbers. The selection of only two of them enables the fundamental observation of the excited secondary instabilities downstream.

3.3. The TDIBC for single-frequency disturbance

In this section, a single-frequency disturbance with small amplitude is introduced in a precursor simulation to study its linear evolution individually. The verification of initialisation for the optimal forcing in the DNS is depicted in Appendix C.

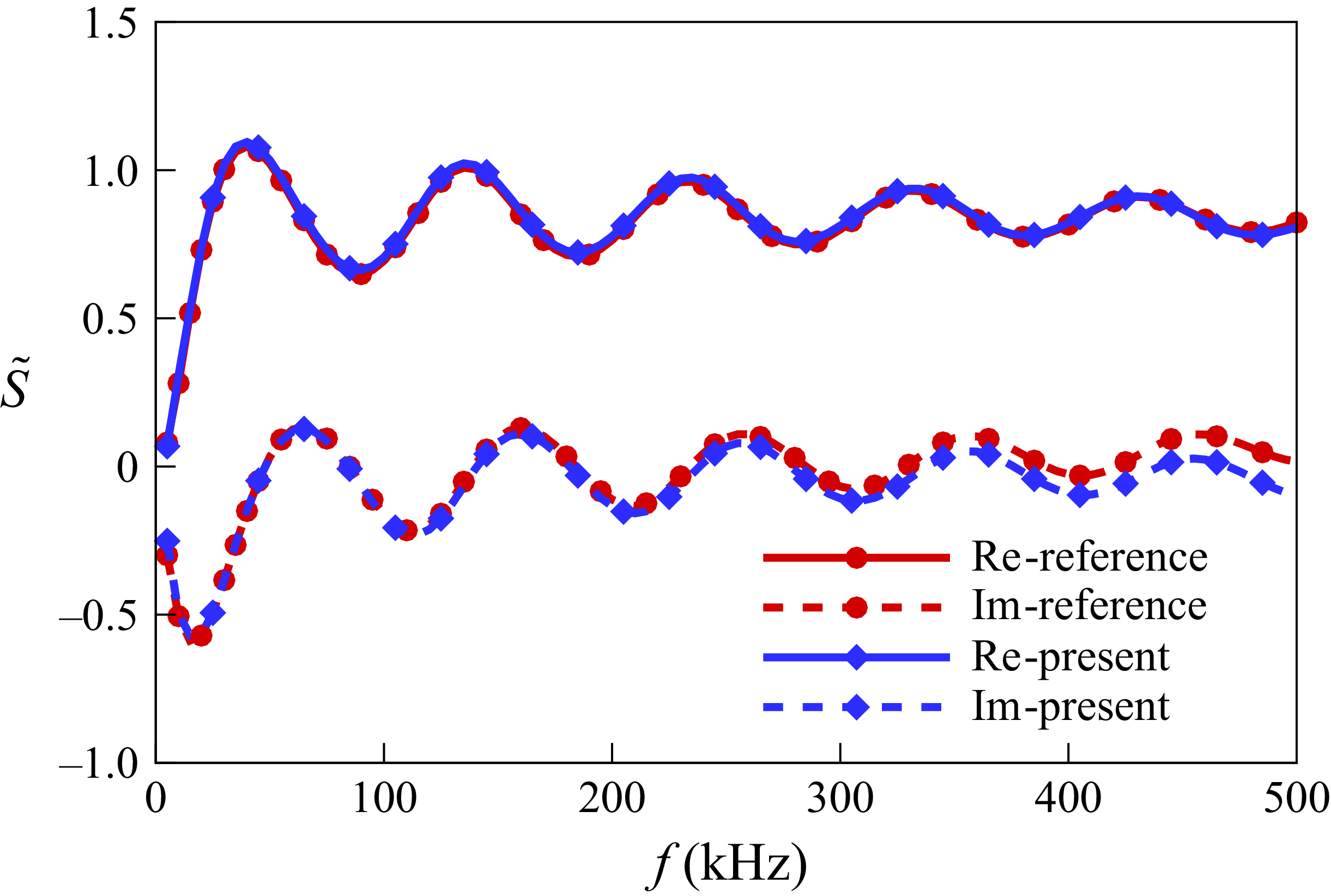

Figure 3 compares the evolution of the Fourier modes (10, 0) with a solid wall and TDIBC, starting from

![]() $x$

= 0.04 or

$x$

= 0.04 or

![]() $x$

= 0.115 m. The acoustic metasurface is observed to suppress the modal growth of the second mode while enhancing the transient growth, based on the definitions of transient-growth regions in § 3.2. Note that

$x$

= 0.115 m. The acoustic metasurface is observed to suppress the modal growth of the second mode while enhancing the transient growth, based on the definitions of transient-growth regions in § 3.2. Note that

![]() $x$

= 0.115 m is the starting point of the modal growth of Fourier mode (10, 0), according to the PSE result in figure 2(

$x$

= 0.115 m is the starting point of the modal growth of Fourier mode (10, 0), according to the PSE result in figure 2(

![]() $b$

). When TDIBC is employed in the range of 0.04–0.2 m, the total Chu’s energy is augmented at around

$b$

). When TDIBC is employed in the range of 0.04–0.2 m, the total Chu’s energy is augmented at around

![]() $x$

= 0.1m, while the wall pressure fluctuation is suppressed there in figure 3(

$x$

= 0.1m, while the wall pressure fluctuation is suppressed there in figure 3(

![]() $b$

). This indicates that the wall pressure fluctuation may not reflect the overall impact of the metasurface. The result agrees with the numerical simulation of Wang & Zhong (Reference Wang and Zhong2012) and the wind tunnel experiment of Lukashevich et al. (Reference Lukashevich, Morozov and Shiplyuk2016), which reported that the acoustic metasurface is effective only within the unstable region of the second mode. The detailed effect of the acoustic metasurface on each primitive variable downstream and upstream of the synchronisation point of the second mode is compared in figure 4.

$b$

). This indicates that the wall pressure fluctuation may not reflect the overall impact of the metasurface. The result agrees with the numerical simulation of Wang & Zhong (Reference Wang and Zhong2012) and the wind tunnel experiment of Lukashevich et al. (Reference Lukashevich, Morozov and Shiplyuk2016), which reported that the acoustic metasurface is effective only within the unstable region of the second mode. The detailed effect of the acoustic metasurface on each primitive variable downstream and upstream of the synchronisation point of the second mode is compared in figure 4.

Figure 3. (

![]() $a$

) The

$a$

) The

![]() $N$

-factor evolution and (

$N$

-factor evolution and (

![]() $b$

) dimensionless wall pressure fluctuation for different wall boundary conditions subject to the optimal forcing of mode (10, 0).

$b$

) dimensionless wall pressure fluctuation for different wall boundary conditions subject to the optimal forcing of mode (10, 0).

Figure 4. Comparison of dimensionless r.m.s. magnitude between linear-stage cases using solid wall (solid line) and TDIBC (dash dot-dot line) at (

![]() $a$

)

$a$

)

![]() $x$

= 0.08 m and (

$x$

= 0.08 m and (

![]() $b$

)

$b$

)

![]() $x$

= 0.16 m initialised by optimal mode (10, 0). The TDIBC is applied within the range of 0.04–0.2 m.

$x$

= 0.16 m initialised by optimal mode (10, 0). The TDIBC is applied within the range of 0.04–0.2 m.

Figure 4 compares the root-mean-square (r.m.s.) values of primitive variables between the results with a solid wall and the acoustic metasurface (realised by TDIBC). It illustrates that the r.m.s. of the wall pressure fluctuation is lower with TDIBC at

![]() $x$

= 0.08 m, which agrees with figure 3(

$x$

= 0.08 m, which agrees with figure 3(

![]() $b$

). However, the density and temperature are significantly enhanced near the boundary-layer edge (around

$b$

). However, the density and temperature are significantly enhanced near the boundary-layer edge (around

![]() $y/{L_{\textit {ref}}}$

= 2). This leads to a higher total energy of the planar wave (10, 0) in this region, namely a larger

$y/{L_{\textit {ref}}}$

= 2). This leads to a higher total energy of the planar wave (10, 0) in this region, namely a larger

![]() $N$

-factor shown in figure 3(

$N$

-factor shown in figure 3(

![]() $a$

). Downstream of the neutral point of the second mode, the disturbances are completely suppressed regarding both the total energy and the wall pressure fluctuation, as shown in figure 4(

$a$

). Downstream of the neutral point of the second mode, the disturbances are completely suppressed regarding both the total energy and the wall pressure fluctuation, as shown in figure 4(

![]() $b$

).

$b$

).

On the contrary, the acoustic metasurface slightly destabilises the oblique optimal disturbance (3, 1), as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5. Comparison of dimensionless pressure fluctuation at the wall for the optimal wave (3, 1) between solid-wall condition and TDIBC in the linear stage.

Based on the above finding, the starting location of TDIBC for both case 2 and case 3 was selected as

![]() $x$

= 0.115 m to avoid unnecessary amplification of unstable waves. Besides, TDIBC ends at

$x$

= 0.115 m to avoid unnecessary amplification of unstable waves. Besides, TDIBC ends at

![]() $x$

= 0.34 m in case 3 because the second mode is stable downstream of

$x$

= 0.34 m in case 3 because the second mode is stable downstream of

![]() $x$

= 0.34 m (see figure 2

$x$

= 0.34 m (see figure 2

![]() $b$

). It should be noted that no prior reports have examined the impact of the metasurface in the transient-growth stage. More research is necessary to determine how the metasurface affects the Orr/lift-up processes that underpin the transient growth. More importantly, it is not yet understood how the transition initiated by the first and second modes responds to the acoustic metasurface. In the next section, the effect of the acoustic metasurface in combination resonance (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

) is focused on, which requires the involvement of both first and second modes.

$b$

). It should be noted that no prior reports have examined the impact of the metasurface in the transient-growth stage. More research is necessary to determine how the metasurface affects the Orr/lift-up processes that underpin the transient growth. More importantly, it is not yet understood how the transition initiated by the first and second modes responds to the acoustic metasurface. In the next section, the effect of the acoustic metasurface in combination resonance (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023a

) is focused on, which requires the involvement of both first and second modes.

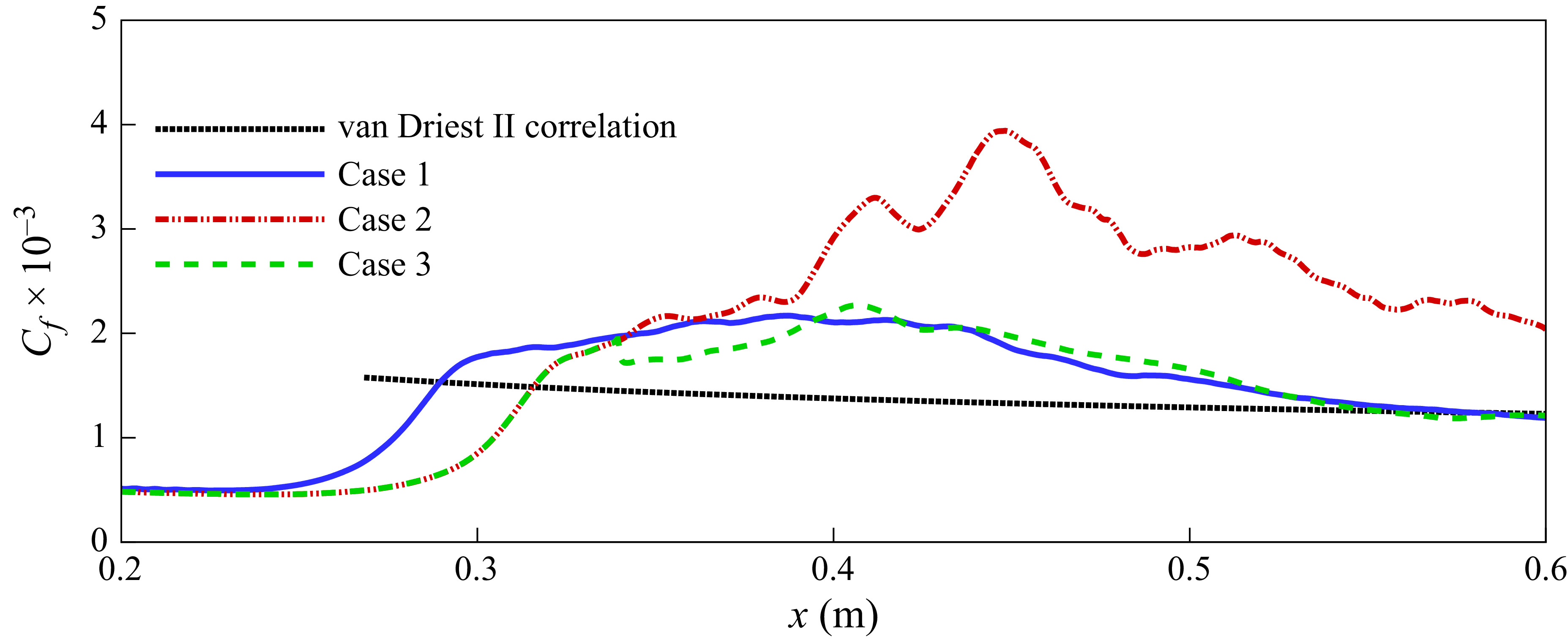

4. Three-dimensional flow field and mean statistics

Following the verification of the initialisation of optimal responses and the embedded TDIBC code, the nonlinear interaction between the low-frequency and high-frequency components and the resulting transition process with the acoustic metasurface are of concern. In this section, optimal disturbances with two prominent frequencies and the same amplitude are applied to initiate the transition. Three cases with different wall boundary conditions listed in table 1 are simulated and compared. The effect of the acoustic metasurface on the combination resonance will be evaluated in detail for statistical average and instantaneous flow fields, especially for mode–mode interaction mechanisms using bi-Fourier analysis and energy budget analysis.

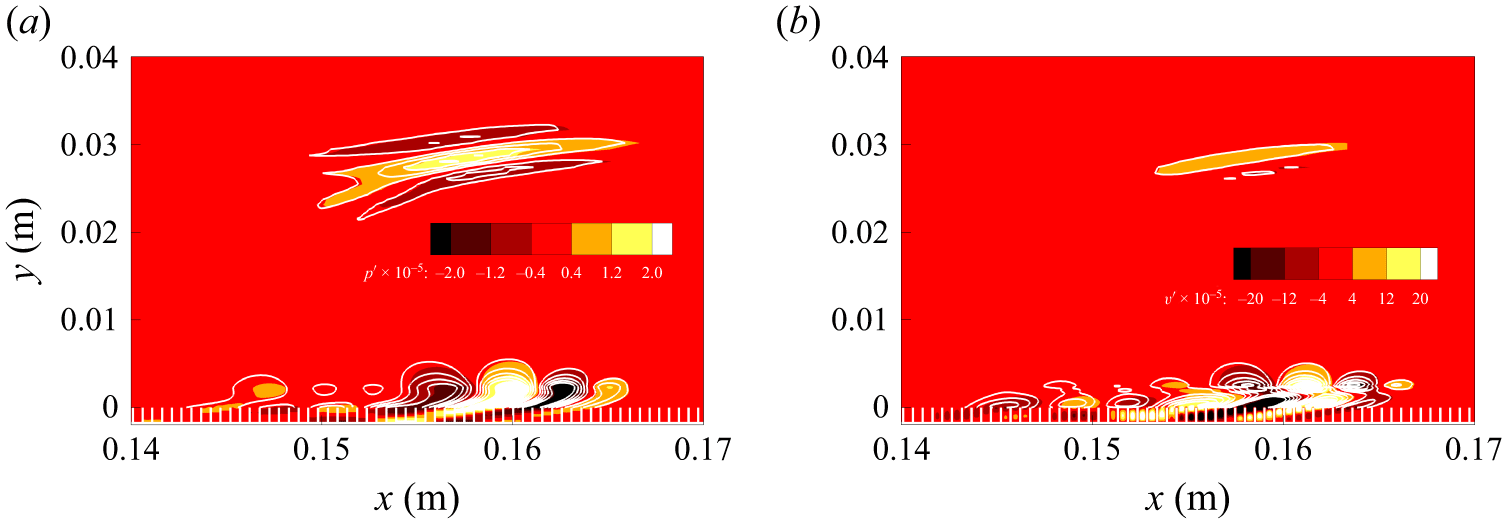

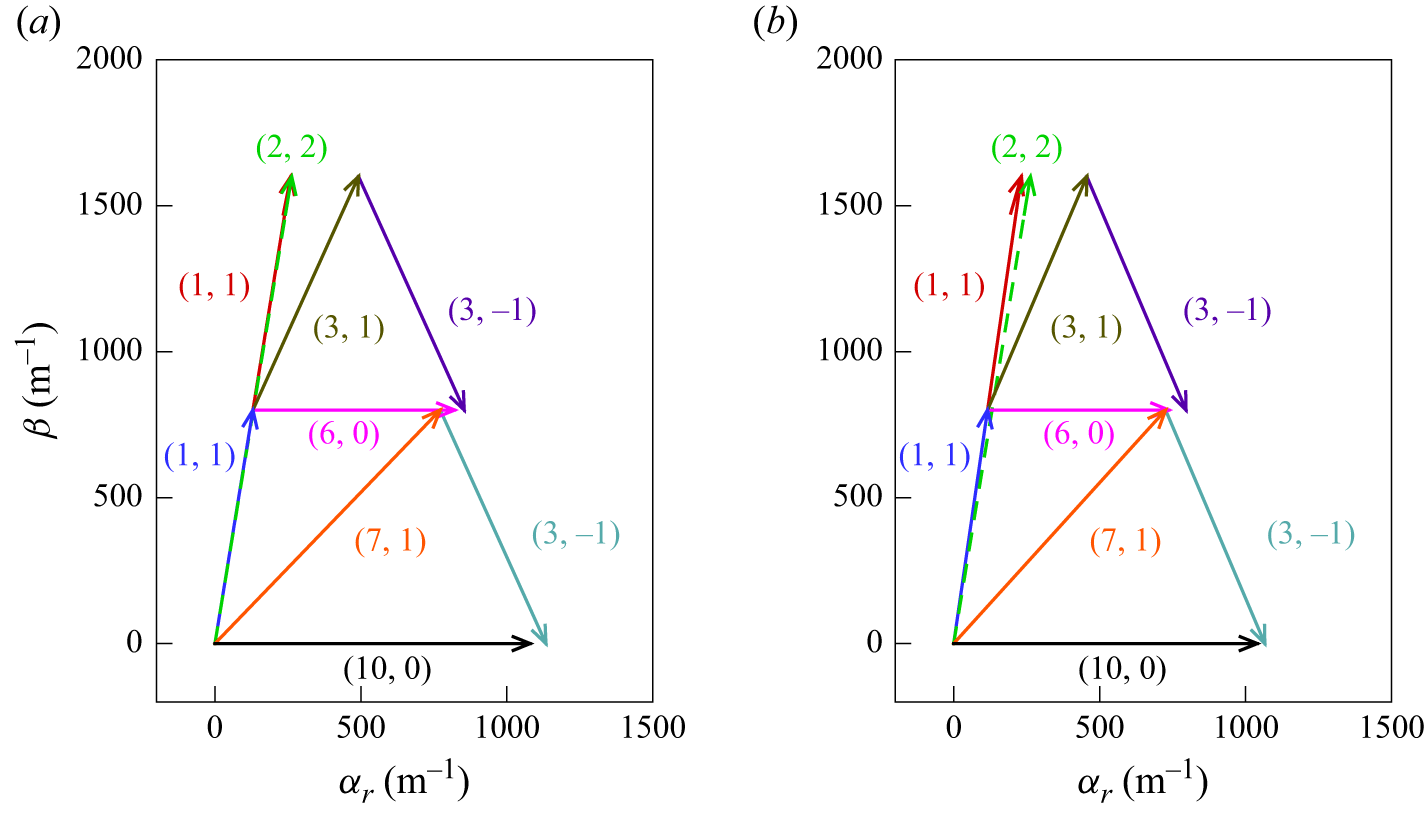

The comparison of vortex structures between case 1 and case 2 is depicted in figure 6. The spanwise-aligned structure observed in case 1 (figure 6

![]() $a$

), representing the planar-wave mode (10, 0), vanishes in case 2 (figure 6

$a$

), representing the planar-wave mode (10, 0), vanishes in case 2 (figure 6

![]() $b$

) due to the presence of the acoustic metasurface. This indicates that mode (10, 0) is highly suppressed by the acoustic metasurface. Further downstream, the staggered structure appears later in case 2 than in case 1, which is caused by the oblique wave

$b$

) due to the presence of the acoustic metasurface. This indicates that mode (10, 0) is highly suppressed by the acoustic metasurface. Further downstream, the staggered structure appears later in case 2 than in case 1, which is caused by the oblique wave

![]() $(3, \pm 1)$

. Additionally, the hairpin vortex, indicating the late stage of transition, is also delayed regarding its appearance in case 2 compared with case 1. By the end of the computational domain, the vortex structure in case 1 has broken down into small-scale structures, indicating fully developed turbulence. This is consistent with the result of the skin friction coefficient illustrated in figure 7, in which the curve of case 1 collapses into the van Driest correlation near the end of the computational domain.

$(3, \pm 1)$