Introduction

Rebetiko is generally considered to be an urban musical genre that originated during the interwar period from a broad urban network spanning the contemporary Greek nation-state (Athens, Piraeus), the Ottoman Empire (Smyrna, Istanbul, Salonica), and the USA (New York, Chicago) as a migration destination from those regions. However, it was the Greek ethnic group, albeit frequently in interplay with others (Turkish, Armenian, Jewish, etc.), that was the common element to varying degrees in all of these settings, and thus rebetiko has been ascribed to the category of Greek urban popular music. Nevertheless, the term rebetiko has been used commercially in multiple ways (Pennanen Reference Pennanen2004:18–9; Gauntlett Reference Gauntlett, Close, Tsianikas and Frazis2005:182–4; Fabbri Reference Fabbri, Plastino and Sciorra2016:30–1), merging several styles such as makam-based melodies, songs in kantada style (serenades), operettas, Balkan hora and sîrba dance pieces (2/4 rhythms), tunes influenced by Greek rural music, and so on (Delegos Reference Delegos2018:10). Within this context, the main body of the so-called rebetiko repertoire was created in the Greek nation-state and the USA after the Greco-Turkish war (1919–1922) and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, under the defining impact of the forced emigration of over one million Ottoman Greeks after their expulsion in the wake of the momentous Treaty of Lausanne (1923).

In the open and complex multi-ethnic Ottoman domain, consisting of various musico-cultural traditions, makam modality evolved in a spirit of reciprocity between Ottoman court music (see Feldman Reference Feldman1996) and Ottoman urban music in its popular vein (see Pennanen Reference Pennanen2004:2–4). As such, makam was a musical mode operating as an expressive compositional tool in music-making among the diverse ethnic communities within the empire and beyond. The European impact on the cosmopolitan Ottoman urban musical world (see Karadağlı Reference Karadağlı2020), which became more profound in the nineteenth century, led to the gradual characteristic intermingling of makam modality with chordal harmonyFootnote 1; for instance, Smyrna, largely populated by Greeks, was influenced by Italian, mostly Neapolitan, models.Footnote 2 By chordal harmony, I refer to the expression of harmonisation through chords/triads originating from the pertinent tonal theory (see Piston Reference Piston and Devoto1978). Thanks to more open-minded performing in multi-stylistic contexts and the impact of recording technology, the ideas emanating from this amalgamation also permeated the practices of Greek musicians, not only in the Ottoman Empire but also in the Greek state, Egypt, and the USA, thereby contributing to the development of interwar rebetiko tunes.

In rebetiko, the fundamental theoretical concepts of makam modality and chordal harmony have been discussed, either separately or jointly, to varying degrees in the academic and non-academic musical spheres (indicatively: Holst [Reference Holst1977]1991:72–6; Payatis [Reference Payatis1987]1992; Manuel Reference Manuel1988:126–36, Reference Manuel1989:75–80, 82–3; Jouste Reference Jouste, Elsner and Pennanen1997; Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999, Reference Pennanen2004, Reference Pennanen2008; Voulgaris and Vantarakis Reference Voulgaris and Vantarakis2006; Andrikos Reference Andrikos2010, Reference Andrikos2018; Ordoulidis Reference Ordoulidis2012, Reference Ordoulidis2017:100–7; Mystakidis Reference Mystakidis2013; Fabbri Reference Fabbri, Plastino and Sciorra2016; Delegos Reference Delegos2018, Reference Delegos2021). In most of those studies, the East-West divide is, either explicitly or implicitly, taken for granted, pervading as it does their vocabulary/terminology and, to a greater or lesser extent, their thinking as a whole. Some conclude that rebetiko is syncretic (e.g. Manuel Reference Manuel1989:75–83; Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999:7, 15, 50). Thus, the genre has been described as resulting from a combination of musico-cultural elements from the Orient and/or the Occident, with makam modality and chordal harmony being acutely attuned to this distinction and serving as connotations of these two poles. However, could rebetiko be viewed as a musically amalgamated wholeFootnote 3 beyond the East–West dipole narrative? Might probing and rethinking the fundamental theoretical concepts of makam modality and chordal harmony in interwar rebetiko provide such a new perspective?

My article draws upon the theoretical background of historical ethnomusicology (Widdess Reference Widdess and Myers1992; Hapsoulas Reference Hapsoulas2010; McCollum and Hebert Reference McCollum and eds2014), including musical analysis, from an open interdisciplinary and critical perspective. I conduct a case study of makam Sabâ (Sabâ makamı in Turkish) phraseology and melodic behaviour and examine the related forms of harmonisation on the guitar, analysing two representative historical rebetiko recordings of the 1930s and interpreting them within the contemporaneous musico-cultural context of the relevant actors. The selection of the makam Sabâ pertains to the fact that its scale, unencountered theoretically in the world of chordal harmony, is extremely dissimilar to those of major and minor modes.

I also employ the Foucauldian concept of heterotopia (1986)Footnote 4 as an analytical tool to argue that expressions of modal heterotopia emerge within interwar rebetiko, in the sense of an unconventional synthesis leading to a musically amalgamated whole wherein all the initially incompatible musico-cultural elements—beyond their ideological negotiation—are “represented,” “contested,” and, as such, transformed or in some way “inverted.” In this regard, my study innovatively explicates the transcendence of the theoretical incompatibility of makam modality and chordal harmony beyond the East–West dichotomy.

From a general and critical standpoint, positions predicated on the East-West dichotomy are largely ideologically inspired, and as such they are disconcerting. The concepts of East and West are founded not so much on geographical as ideological-cultural grounds, implicitly expressing a political orientation and thus demonstrating inherent fluidity. In fact, the Orient and the Occident are shifting entities with an imaginary relationship (cf. Scott Reference Scott, Kurkela and Mantere2015:142), nurturing cultural preconceptions, prejudices, and biases in a context of diverse ideological-cultural claims and the Western/Eastern gaze. Therefore, despite the establishment of the relevant hegemonic narratives and their extensive invocation, the use of these concepts is stereotypical and obsolete in light of today’s critical ethnomusicological perspective, which attempts, as far as possible, to uproot the ideological “weeds” from the analytical and interpretive tools employed in the music cultures under examination.

To deconstruct the East-West dichotomy-based representations of the melodic and harmonic ontology in interwar rebetiko, chiefly expressed either through pure makams or heptatonic scales—connotations of the Orient and the Occident respectively—I introduce the terms “equal-tempered makam” (a musically amalgamated and secondary form of modality) and “idiosyncratic harmonisation,” both of which mirror expressions of modal heterotopia. These concepts offer an innovative and insightful perspective on the transformation of the Ottoman makam into its popular version within rebetiko music. The phenomenon is primarily defined by the gradual appearance of chordal harmony in a distinct and theoretically unconventional manner, coupled with an array of factors related to the organology—mostly to the three-course bouzouki and the guitar—and the instrumentation of the repertoire.

About Heterotopia

…[Heterotopias are] counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality

(Foucault Reference Foucault1986:24).Foucault perceives heterotopia mostly as a spatial concept wherein the terms of existence of certain other sites are represented, contested, and ultimately inverted. He exemplifies heterotopia by variously invoking a host of cases, such as prisons, brothels, colonies, a ship at sea, cemeteries, and so on (Reference Foucault1986:25, 27). For instance, in brothels, the prevailing social codes and values of sexuality and morality are instantly questioned and transformed into those characterising the venue as a counter-site. In general, heterotopia can be understood to have an unconventional character as an entity outside of the other conventional entities represented within it by means of processes wherein contestation and inversion are fundamental.

In Greek urban music-related studies, there have been three cases of the use of heterotopia that differ from my viewpoint as described below. Tragaki introduced heterotopia for the first time; she considered the rebetiko revival performances of the previous decades in Thessaloniki to be musical heterotopias that formulate the corresponding urban spaces and the ways people develop their musicality in a spirit of otherness (cf. Reference Tragaki2007:xviii, 299–309). Erez views the space of Israeli Jaffa in Tel Aviv as a heterotopia with regard to the political order and social topography (cf. Reference Erez2016:6), where Greek popular music after the 1960s becomes a vehicle for ethnic identification in Israel. Boutsioulis (Reference Boutsioulis2020) utilises heterotopia to analyse the new aesthetic contexts of rebetiko arrangements (1954–2015) by Greek composers educated in classical music.

In my case study, in which I interpret the word “site” in a more general sense as a context, an entity, or an element and contextualising it within the musico-cultural sphere, I argue that musico-cultural elements such as makam modality and chordal harmony are reflected and, in a sense, contested in the historical rebetiko performance, as their blending and transformation lead to a musically amalgamated whole with its own idiosyncrasy; thus, a modal heterotopia emerges in interwar rebetiko.

Furthermore, according to Foucault (Reference Foucault1986:25): “The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible.” Hence, heterotopia can include inconsistent sites or spaces, meaning in a broader sense a synthesis of a variety of incompatible contexts or elements. In this respect, I also apply heterotopia to the rebetiko field, invoking theoretically contradictory elements of music theory such as chordal harmony and equal temperament versus makam modality, juxtaposed in one amalgamated modal entity. In other words, I explicate the amalgamation of these theoretically incompatible elements in interwar rebetiko as a modal heterotopia.

Consequently, heterotopia serves as a critical and deconstructive device by virtue of its basic attributes, those of contestation and inversion (that is, transformation). Its creation can be viewed as a three-phase process: representation ➔ contestation ➔ inversion. Thus, the result is described in terms of its components and the relationships between them. Simultaneously, heterotopia can be utilised for the examination of music cultures as an ideologically neutral analytical/interpretive tool owing to the fact that it is not associated with any common ideological narrative.

Chordal Harmony and Ottoman Makam

In memory-based and non-literate musical cultures, music actors usually make selective and partial use of attributes of theoretical musical systems (cf. Hapsoulas Reference Hapsoulas2010:60) that have been experienced in a broader socio-cultural context; the functionality and thus the character of a musical genre/culture define the parameters of the above phenomenon.

Chordal harmony is a practice derived from the theory of Tonal Harmony and involves the harmonisation of a melody, that is, the selection and sequence of chords as well as the way they are connected to one another in a process that acts upon a certain melody. The case of rebetiko falls into the category of makam-related musical traditions, where the impact of chordal harmony leads to a form of musical amalgamation (cf. Manuel Reference Manuel1988:132–3, Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999:72–3; cf. Delegos Reference Delegos2021:335).

At the turn of the twentieth century, the harmonisation of traditional melodies, mostly in the framework of more literate approaches by Europeans, was already being practised in large Ottoman and Greek urban areas, especially in the performance contexts of opera, operetta, mandolinata (mandolin ensemble), choirs, and venues such as nightclubs and coffeehouses (e.g. gazinos [Istanbul] and café-amans [Athens]); for example, the Italian Donizzeti’s harmonisation of Turkish pieces in Istanbul from 1832 (Karadağlı Reference Karadağlı2020:22) and the Frenchman Bourgault-Ducoudray’s harmonisation of Greek pieces in Athens and Smyrna in 1877 (Kokkonis Reference Kokkonis2017:16–8, 21, 24). During the Europe-influenced reforms of the Tanzimat era (1839–1876) in the Ottoman Empire, many mostly Catholic Europeans—the so-called Levantines—were naturalised in cosmopolitan urban centres such as Istanbul, Smyrna, and Salonica, which were already populated by Turks, Greeks, Jews, Armenians, and so on (e.g. about Smyrna, see Schmitt Reference Schmitt, Smyrneli and Kourezi2008:129–45). The prevalence of Europe-oriented musical educationFootnote 5 (Kalyviotis Reference Kalyviotis2002:39–40; Karadağlı Reference Karadağlı2020:20, 21) and the Italian vogue accordingly cultivated musicality on a wider social and ethnic level (cf. Ünlü Reference Ünlü2004:166–8).

In the Greek state, during the first decades of the twentieth century, the music of domestic operettas (e.g. by Nikos Hatziapostolou) and the so-called elafra or “light music” (e.g. by Attic)—both related to European composers that had been educated in classical music through local and foreign conservatories—in conjunction with the kantada from the Ionian Islands (influenced by the neighbouring Italian model, Manuel Reference Manuel1989:79; Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999:26) planted the seeds of harmonisation in rebetiko. After the 1923 compulsory exchange of populations according to the Treaty of Lausanne, Greek musicians from the Ottoman Empire (e.g. Kostas Karipis from Istanbul and Spiros Peristeris from Smyrna, the latter with an Italian mother and education) employed the practice of chordal harmony on the guitar in rebetiko performance, shaping a distinctive guitarscape.Footnote 6 This environment where musico-cultural practices amongst the rebetiko guitarists take place, the “rebetiko guitarscape,” reflected the values of the cultures of their provenance within a new amalgamated aesthetic result.

Chordal harmony in interwar rebetiko, which was largely practised in an idiosyncratic way, was a “bottom-up” process, from the melody to its tonal centres, reaching beyond vertical developments and the established theoretical scale-centric harmonisations exclusively predicated on the scale degrees. Pennanen (Reference Pennanen1999:77) encapsulates this modal harmonisation with the term “traditional” as a theoretically non-classical process, but I suggest the term “idiosyncratic harmonisation” from its harmonic uniqueness, and because the meaning of “traditional” could characterise any musical world, whether art or folk, despite their sometimes vague boundaries. Frequently invoking the European music-related modal scales (Dorian, Phrygian, etc.) without paying appropriate attention to the Ottoman affinity in melodic development, Manuel (Reference Manuel1989:83) portrays this amalgamated phenomenon as the coexistence of “…modal ‘Mediterranean’ harmony…with Western common practice”, that is, an ideologically inspired interpretation, illustrative of the hegemonic narratives of Mediterraneanism and Westernism. Nevertheless, the key elements to understanding this sort of modal harmony are analysis of the modal melodic development (to highlight the related tonal centres) in relation to the Ottoman modes and their derivatives, and analysis of the relevant musical instruments. The leading role for the harmonisation is taken mostly by the guitar, and less by the baglamas, although both provide rhythmic accompaniment by means of chords, triads, and at times droning.

The protagonist in the rebetiko guitarscape is the contemporaneous equal-tempered acoustic guitar, commonly played with a plectrum and with standard tuning (E2-A2-D3-G3-B3-E4),Footnote 7 and demonstrating a dual identity: firstly, it functions as a solo instrument for the main melody in the high strings; secondly, and prevalently, it rhythmically accompanies the melody through the playing of chords, drones, or at times producing bass melodic lines between the rhythmic accompaniment in a sense of heterophony. The second identity is a kind of plectrum style that could be called basokitharo Footnote 8 (“bass-guitar” in English), an idiomatic playing of individual low notes on the strong beats and of the chords or triads on the weak ones, with picking starting from the middle to the high strings with one staccato stroke (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Playing d minor chord in the Basokitharo style. Zeimpekikos is a typical rebetiko dance rhythm in 9/4 (by author).

Guitar in the basokitharo style exhibits three roles. Firstly, it is the main rhythmic instrument of the rebetiko band, resembling a percussion instrument in the technique of the picking hand (see below Example 2). Secondly, it imitates the character of a double bass in the melodic phrases and the individual notes (on the strong beats) in the low strings (see below Example 2); less frequently, it resembles an oud performing large melodic parts in low octave, but in an equal-tempered manner by nature (see below Example 1 in canto B). Thirdly, it is the basic instrument for producing chords, thus offering the sense of harmony (see below Example 2). Under the prism of this multiplicity and beyond the melody-harmony dualism, the function of the guitar is to contribute significantly to the aesthetic result by accompanying rhythmically, offering bass melodic lines and either plain or more sophisticated influential harmonisation in melody, and strongly generating low mid-range frequencies, thereby giving new character to the main melody. The instrumentation is an additional crucial factor for the final aesthetic outcome.

In interwar rebetiko, while the violin, largely related to the Ottoman Greek music style, is one of the main solo instruments—among the oud, kemençe (kind of lyre), mandolin, and others—the organological emblem is the fretted plucked string three-course bouzouki. Its standard tuning is D3D4–A3A3–D4D4, although there are alternative tunings, the so-called douzenia or kourdismata in Greek, encountered in some interwar rebetiko recordings (Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999:156). The rebetiko baglamas is similar to the three-course bouzouki, but much smaller, tuned an octave higher (D4D5–A4A4–D5D5) and producing a strident sound (Figure 2). Its role in a rebetiko band is distinct and differs to a large degree from that of the bouzouki, mainly accompanying with triads and producing melody or drones. The baglamas either follows the rhythmic approach of the guitar or traces the rhythm in shorter note values played continuously.

Figure 2. From the left, seated on the floor: two unknown figures next to Yiannis Soulis (oud). At the top: Giorgos Batis (baglamas) and Nikos Karydakias (three-course bouzouki), 1938? (Petropoulos [1979]1991:448).

Concerning the Ottoman makam, it is historically associated with court music, also known as Ottoman classical/art music, the majority of which was renamed “Turkish art music” as a result of the Turkish nationalisation of Ottoman music in the context of the relevant modernity project, and despite political and ideological opposition to Ottoman culture from Republican Turkish governments between Kemal Atatürk’s death in 1938 and the 1970s (cf. Feldman Reference Feldman1996:16).

In contrast with court tradition, popular music exhibited inherently more limited musical forms, and hence the relevant musicians employed makams in a more condensed manner: that is, with a more restricted seyir (melodic progression/unfolding/behaviour) and range (cf. Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999:31, 78–9; Delegos Reference Delegos2018:34, Reference Delegos2021:330), with fewer melodic movements and fewer or even no modulations. This treatment could be interpreted as a result of the more hedonistic functionality of Ottoman popular music, in contrast to the backdrop of social elitism and solemnity of court music with its stricter obedience to the established “makam rules.” For instance, in an entertainment context for dancing, large and more sophisticated makam forms like peşrev (instrumental classical form) would hardly be attractive.

Nonetheless, several composers inhabited both traditions, vacillating over the stereotype of vertical social mobility and essentially deconstructing the Art-Popular dualism; for example, the renowned Rum composer Kemençeci Vasilaki Efendi (1845–1907) would perform at village fairs, meyhaneler (a refined musical tavern), and musical cafés (in ince saz ensembles), among other venues. Vasilakis’ famous kemençe pupils were Cemil Bey (1873–1916) and Anastasios Leontaridis, father of Lambros Leontaridis (1898–1965). The latter was known for his interwar kemençe recordings of rebetiko-related Istanbul style in Greece (cf. Tsiamoulis and Erevnidis Reference Tsiamoulis and Erevnidis1998:34–7).

Although Feldman (Reference Feldman1996:504) directly links the core of Ottoman music culture with the Ottoman Turks, it would be more appropriate to note that the Ottoman makam—whether popular or classical—demonstrated a transnational character, and its sound pervaded most ethnic groups of the empire without being exclusive to any one of them (cf. Zannos Reference Zannos1990:4; cf. Aksoy Reference Aksoy1996). For instance, even in Ottoman court music, key figures had roots beyond the Turkish community; Kemanî Tatyos Efendi (1858–1913), Lavtacı Andon (nineteenth century), and Tanbûrî İsak (1745–1814)—from the Armenian, Rum, and Jewish millet, respectively—were also influential personalities. Nevertheless, the above facts did not prevent the subsequent nationalisation of Ottoman music, whether partial or total, by related nation-states (Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, etc.).Footnote 9

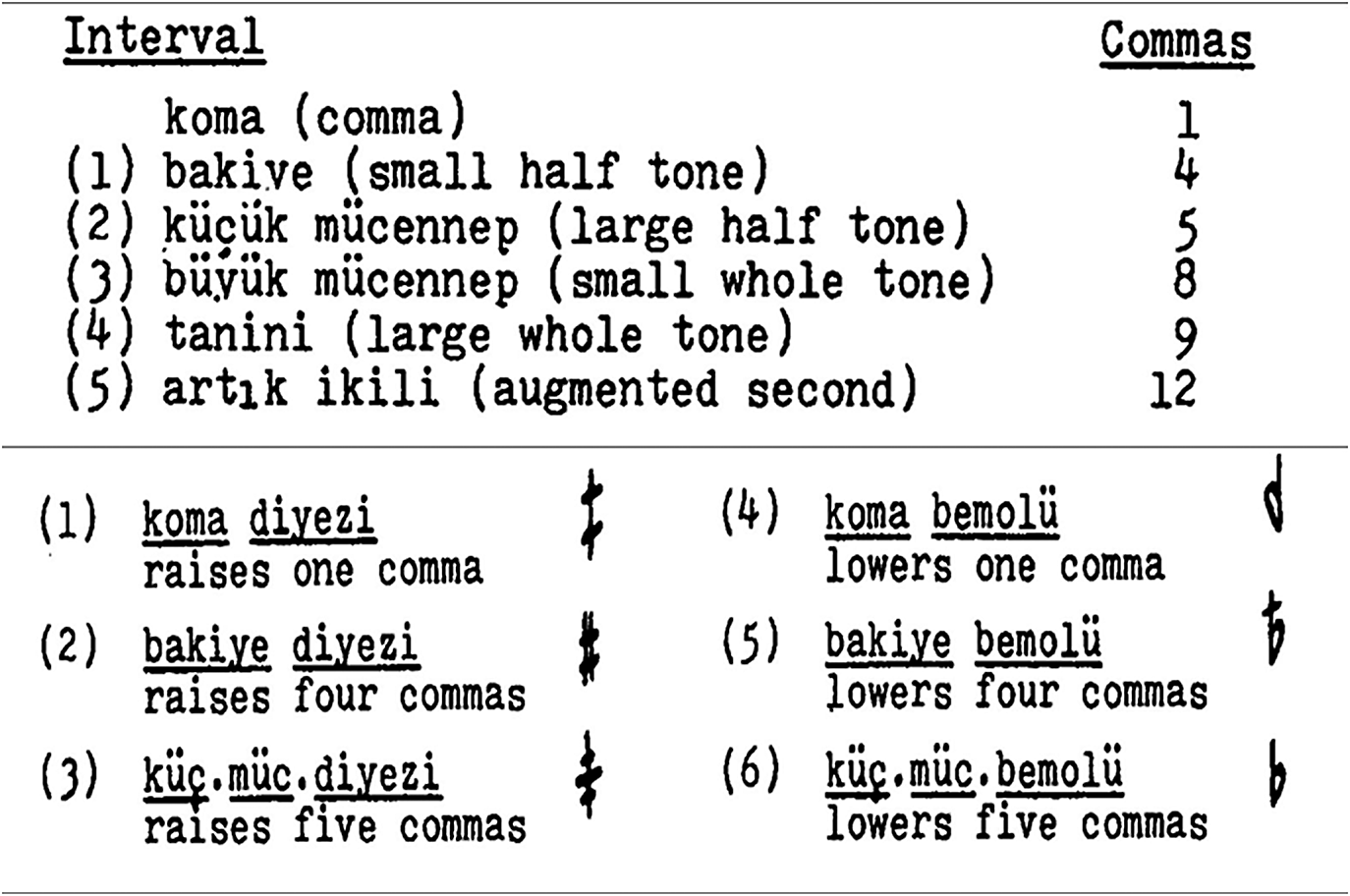

In both theory and practice, makam is closely tied to microintervals, that is, with non-equal temperament. After the epistemology of the Arabo-Persian Systematist school during the Middle Ages, the prevalence of orality from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century reflected the dearth of makam theory books on comma intervals (cf. Feldman Reference Feldman1996:221–2; cf. Behar Reference Behar2017:75–6; cf. Öztürk Reference Öztürk2018:1772). The theoretical issues of the accurate size of intervals, the intonation, and the attendant accidentals (Figure 3; see also Aydemir Reference Aydemir2010:23–4) were broached afresh in Turkish modern musicological discourse, initially by Rauf Yekta (1871–1935) and subsequently by Suphi Ezgi (1869–1962) and Saadettin Arel (1880–1955) in a neo-systematist spirit (cf. Signell Reference Signell1986:22–4; see also Öztürk Reference Öztürk, Komsuoğlu, Toker and Nardella2021:53–6, 64–7, 69–71). Nonetheless, the historical performance practice of intonation did not adhere to these theories, which crystallised the intervals in a static mathematical way utilising Pythagorean or Holderian-Mercator commas; instead, it exhibited a polymorphous intervallic character as one of the fruits of orality. Essentially, Yekta’s seminal lemma La musique turque [The Turkish music] in the Lavignac Encyclopedia (1922) was an occidentalistic, positivistic endeavour inspired by the contemporaneous European musicology as manifested in the context of the Turkish modernity project (see Öztürk Reference Öztürk, Komsuoğlu, Toker and Nardella2021). In a sense, this is an analogue of Marcus’ description (Reference Marcus1989:45) of the attitude of Arab researchers from the 1930s to 1970s, with a terminology based on East-West dualism: “As Westerners came to study the maqam system, wanting to focus on melodic movement, Arab theorists were looking to the West, fascinated by the static elements of Western music theory, especially scale.”

Figure 3. Theoretical intervals and the six accidentals according to the Ezgi-Arel notation system (Signell Reference Signell1986:23–24).

This fluidity in terms of the rendering of microintervals suggests that the issue of intonation, especially in Ottoman popular makam, was and still is inherently open, but without creating problems for musicians (cf. Signell Reference Signell1986:44; cf. Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999:29–31, Delegos Reference Delegos2018:41–8). Historically, the intervallic diversity depends on location, culture, genre, musical style, the performer’s personal style, and so on (Signell Reference Signell1986:44). In fact, this intonational polymorphy is phonetic, lying as it does in the size of intervals, and not phonemic, that is, without changing the meaning of intervals.

Other attributes of makam include scale—not strictly in an octave sense but mostly in pentachords, tetrachords, and trichords (melodic structures of five, four, and three successive degrees respectively, as parts of the broader melodic body of a makam)—seyir, modulations, idiomatic phraseology, and so on (cf. Yekta Reference Yekta and Lavignac1922:2995–6; cf. Signell Reference Signell, Danielson, Reynolds and Marcus2002:48; cf. Aydemir Reference Aydemir2010:23–30). Yekta claims that without melodic movement and stops makam (“mode”) would be “a body without soul” (Reference Yekta and Lavignac1922:2996); similarly, Signell (Reference Signell1986:48) argues that “the mere scale of makam is like a lifeless skeleton. The life-giving force, the forward impetus of the melody is supplied by the seyir (progression).” From this perspective, seyir acts as the overarching attribute of makam.Footnote 10

Ottoman makam obviously continued to exist even after the end of the Ottoman Empire as marked by the Greco-Turkish war (1919–1922), whose last phase is known by Greeks as the “1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe.” The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne provided for a compulsory population exchange, based on religion, between the two nation-states. Thereafter, Ottoman Greek musicians of various genres (Panagiotis Toundas, Ioannis Constantinidis, etc.) became refugees, forced to migrate mostly to Greece or the USA. As bearers of Ottoman repertoires and styles, and frequently with extensive experience in corresponding recordings (cf. Ünlü Reference Ünlü2004:170–4), the majority of these influential musicians de-territorialised/re-territorialised and revived this music culture in Greece (frequently in new arrangements), grafting their rich musical experience onto contemporary Greek urban popular music and paving the way for the establishment of what is generally called rebetiko. In this manner, as well as through the performances and recordings of the Greek diaspora in the USA, Ottoman makam modality, either individually or in concert with chordal harmony, contributed to the development of rebetiko tunes. Moreover, in a spirit of acculturation, other smaller ethnic groups such as the Vlachs and Gipsies were also bearers of modal musics within the broader Greek context (Manuel Reference Manuel1988:126–7).

Makam Sabâ

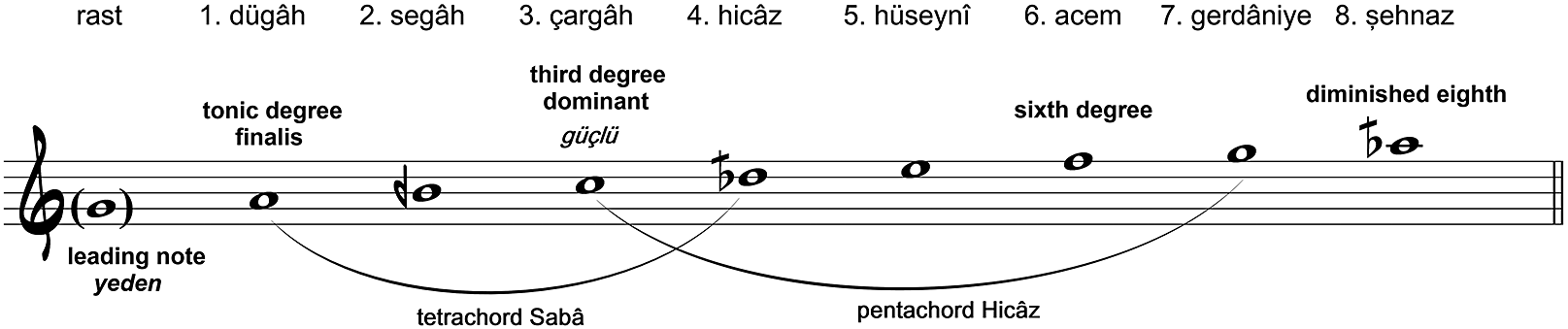

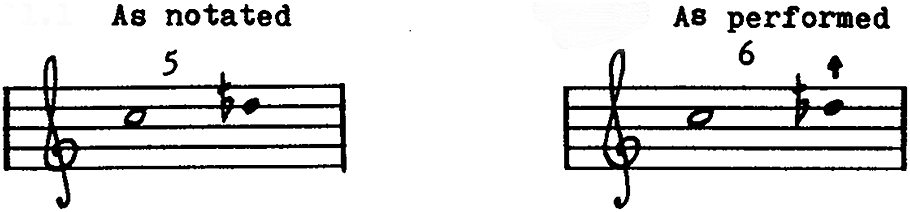

The makam Sabâ is one of the very distinctive Ottoman makams in terms of “sound colour,” and seems characteristically exotic to outsiders (Signell Reference Signell, Danielson, Reynolds and Marcus2002:49). Its main structure consists of a tetrachord Sabâ (or a trichord Uşşak according to Arel [Reference Arel1968]1993) on the first degree (dügâh perde)Footnote 11 and a chromatic pentachord of Hicâz character on the third degree (çargâh) (Figure 4). The intervals deriving from the second (segâh) and fourth degrees (hicâz, also known as sabâ perde nowadays) are not usually performed as notated (Figure 5). These irregularities between theory and practice have been underscored by pertinent researchers (Signell Reference Signell1986:37–8; cf. Feldman Reference Feldman1996:213–4; Pennanen Reference Pennanen1999:77–8; Aydemir Reference Aydemir2010:196).

Figure 4. The structure of makam Sabâ (cf. Aydemir Reference Aydemir2010:196).

Figure 5. The fourth degree of makam Sabâ (Signell Reference Signell1986:38).

In general, tonal centres during a melodic progression are notes on which the melody is in a sense of commencement, temporary rest (muvakkat kalışlar: temporary stops), and finality/completion. The tonal centres of the makam Sabâ are the dominant note (güçlü) on the third degree (çargah), whereas the entry note (giriş) is on the tonic (dügâh) or the third degree, and the final stop/finalis (tam karar) is always on the tonic. Temporary cadences on the base note (dügâh) and the dominant, known as yarım karar, are also possible. Additional active notes are on the sixth degree (acem) and less frequently on the leading note yeden (rast), the fifth (hüseynî), and seventh (gerdâniye), around which the melody revolves and stops (asma karar: suspended stops) (Aydemir Reference Aydemir2010:26–7, 196–7). Moreover, there is no symmetry in the octave: instead of an upper tonic, there is a diminished eighth, that is, a four-comma flat upper A note (şehnaz) (Figure 4). This phenomenon is characteristic of several Ottoman modal entities (Signell Reference Signell1986:43–4), unlike the well-known minor and major modes that demonstrate a completed octave in a scale-centric sense.

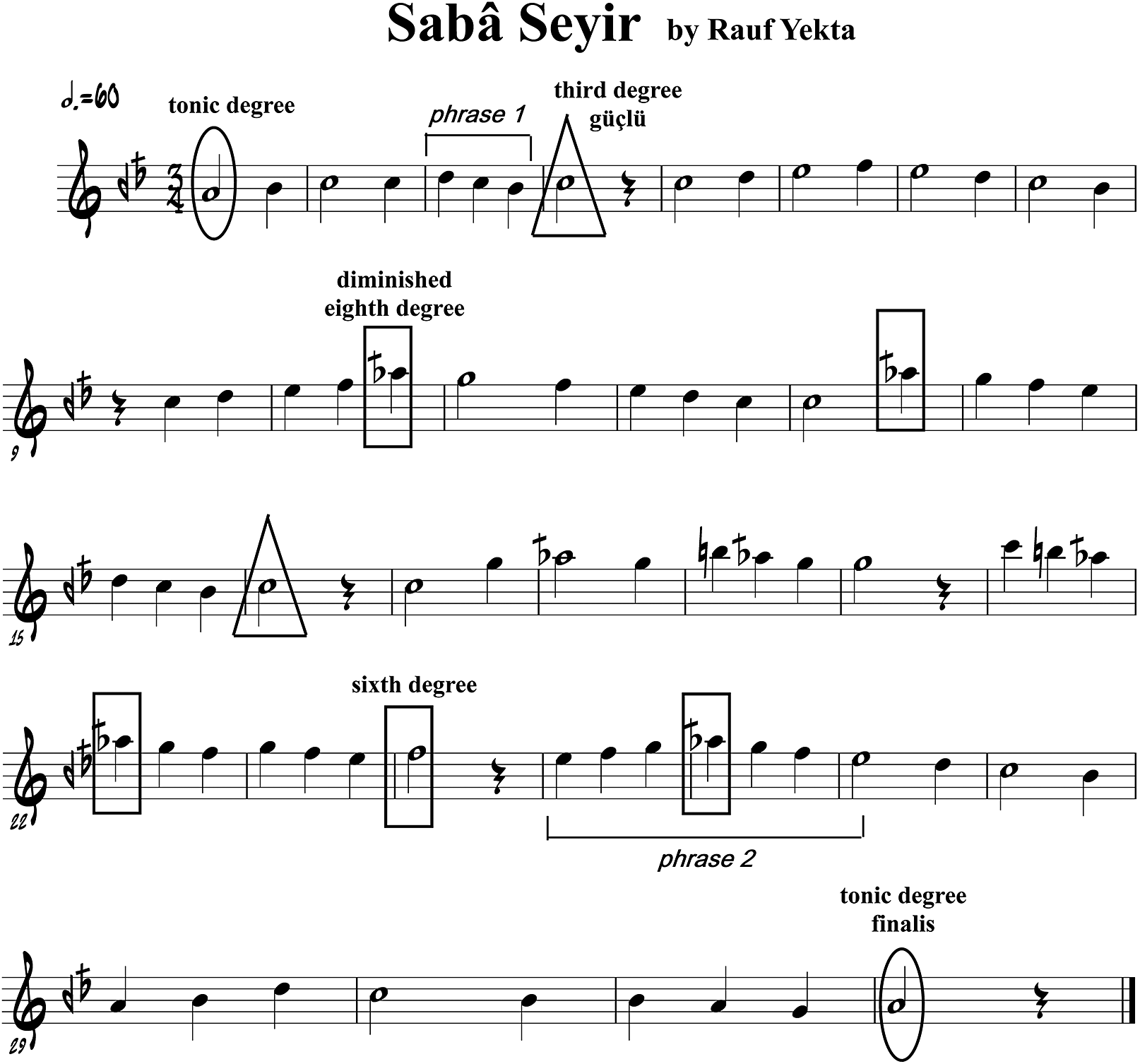

The sequence of the tonal centres in a melodic progression is vividly outlined by seyir. By definition, seyir is a brief melodic unfolding of the essentials of a makam, such as scale, typical phrases, tonal centres, melodic direction, range, and so on (cf. Signell Reference Signell1986:48, 51–2; cf. Aydemir Reference Aydemir2010:23–30; Öztürk Reference Öztürk2018:1772, 1778). Regarding the makam Sabâ, I present one typical version of seyir by Yekta published within the interwar period (Reference Yekta and Lavignac1922:2998; Signell Reference Signell1986:62) (Figure 6) and a stereotyped motive (Signell Reference Signell1986:127) (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Rauf Yekta’s Sabâ seyir (cf. Yekta Reference Yekta and Lavignac1922:2998; cf. Signell Reference Signell1986:62; comments by author).

Figure 7. Stereotyped motive in makam Sabâ (Signell Reference Signell1986:127).

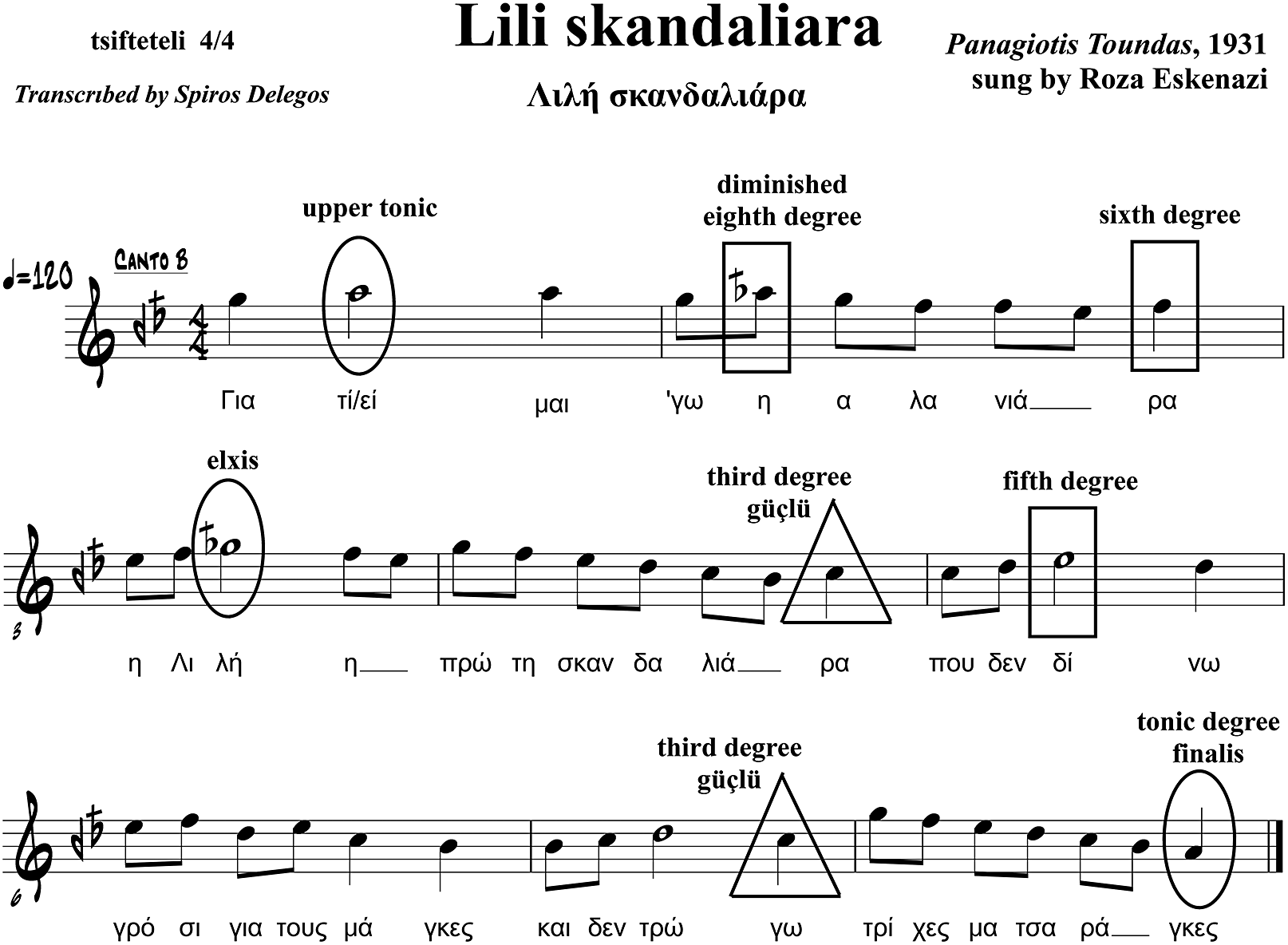

According to this version, the melodic direction is clearly ascending, meaning that the melody begins from the tonic, rises to the dominant, reaches the diminished eighth and finally returns to the tonic. The tonal centres, highlighted by the author in shapes, are the tonic degree (ovals), either as the entry note or the final stop (finalis), and the third degree (triangles) as dominant (güçlü), while active notes include the sixth and the diminished eighth, used as typical passing notes (rectangles).

Example 1: Makam-Based Music Style

After 1922—a turning point in Greek music history—the Ottoman Greek musicians arriving in Greece as refugees contributed greatly to the development of interwar rebetiko, importing a makam-based repertoire mostly performed on the violin. As an expression of agency, a number of them even became record company musical directors and producers.

It is, however, noteworthy that, even before 1922, Ottoman popular music and makam modality had already been introduced to the musical culture in Greece owing to the tours of several musical ensembles, mostly based in Istanbul and Smyrna. According to Hatzipantazis’ (cf. Reference Hatzipantazis1986:67–9, 88–9) research into café-aman in the Greek state, from at least the last quarter of the nineteenth century, musical ensembles of various ethnicities from Ottoman and ex-Ottoman territories in the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean had performed in Athens. Therefore, Ottoman popular music would have been in fashion in the Greek region. In fact, this is an umbrella-term that represents a type of multi-stylism including all the popular musical genres developed and/or localised in large urban centres, as hubs of a broader network wherein tunes and songs were in transit within and beyond the Ottoman ecumene. An additional important factor in these musico-cultural trajectories was the diffusion of the contemporaneous discography.

An example from the rebetiko repertoire involving the makam Sabâ is “Lili skandaliara” [Lili the Naughty] (Toundas Reference Toundas1931). The piece was recorded in 1931 in Athens, composed by Panagiotis Toundas (1886–1942) and sung by Roza Eskenazi (1897–1980) (Parlophon 101195/B. 21605-1) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Gramophone record of “Lili skandaliara”, composed by Panagiotis Toundas (Stavros Kourousis’ private archive).

Toundas, born in Smyrna, settled in Athens after 1922, where he lived the rest of his life. Exhibiting a multiplicity of cultural identities and an aesthetic openness stemming from his origins and rich experiences, Toundas was a musically literate personality with multi-faceted musicianship who composed in a variety of genres (zeimpekikos, tango, foxtrot, etc.). He had a profound knowledge of makam tradition, was considerably skilled on the mandolin, possibly participated in the so-called estudiantinas (a type of mandolin-based orchestra of European origin, mostly associated with Ottoman Greeks, performing various repertoires, see Kounadis Reference Kounadis2003:266–83, Ünlü Reference Ünlü2004:169–74, and Ordoulidis Reference Ordoulidis2017:102–4), and served as a record company promoter, producer, and director in Athens until 1940, when the Axis occupation of Greece began. According to unverified conjecture by Hatzidoulis (Reference Hatzidoulisn.d.:38), before 1922 Toundas had sojourned for years in Ethiopia and Egypt, where his teacher was said to be Kemençeci Vasilaki Efendi (1845–1907), a Rum composer of Ottoman classical music.

Musical Analysis

Theoretically, the makams Hicâz and Sabâ share the same base note A (dügâh).Footnote 12 Based on this principle, the melody initially follows the makam Hicâz, but in the second section of the vocal part (canto B, Figure 9) enters the Sabâ context from the upper tonic (muhayyer) and descends through the accidental of this note to a diminished eighth (şehnaz); due to the nature of the modulation, the melodic direction is descending. This treatment seems to be characteristic for Toundas: to enter the makam Sabâ from Hicâz, as in “Gia mia hira paihnidiara” [For a Naughty Widow], a 1935 recording (Odeon of Greece GO-2392/GA-1912).

Figure 9. Score for vocals (canto B), “Lili skandaliara”, composed by Panagiotis Toundas (transcribed by author).

The alternative use of high or low versions of some degrees can be described as a “melodic attraction” of one secondary note to another primary, also known as elxis, Footnote 13 an apt term from Greek Orthodox ecclesiastical music utilised in makam analysis in the current Greek context. According to Signell (Reference Signell1986:68), this phenomenon is recognised and characterised as “single note borrowing.” In the example, when an elxis of the seventh degree (gerdâniye) to the sixth degree (acem) occurs it results in the “borrowed note,” a four-comma flat G note (mâhûr). Moreover, the typical tonal centres of the makam Sabâ on the tonic (as finalis), third and sixth degrees are activated, while the intervals of the singing voice, the violin, and the kanun are rendered as described in the section “Makam Sabâ.”

This kind of melodic unfolding, which combines the makam Hicâz with a progression of Sabâ, is encountered in a quite rare Ottoman compound makam called Nevrûz-i Rûmî. Footnote 14 In all likelihood, Toundas was directly inspired by this makam, with an array of his compositions having this character (e.g. “Bida Yalla” (GO-1809/GA-1624/1933) and “Giafto foumaro kokaine” [That’s Why I’m Smoking Cocaine] (Columbia of Greece WG-376 / DG-279/1932).

In this Sabâ part (canto B), the guitarist in the second role of the basokitharo style, possibly Kostas Skarvelis (1880–1942) from Istanbul, does not offer harmony in the sense of playing chords, but mimics an oudist by ably performing the basic melodic line in the low strings in an equal-tempered manner due to the organological nature of the guitar. The low mid-range guitar in a supportive role, along with the high-frequency violin and kanun, all discreet in terms of sound volume, co-assist the singing voice heterophonically in octaves, thereby filling the frequency range—a main aspect of the final aesthetic result.

The bridging of the theoretically inconsistent worlds of the equal-temperament on the guitar and the non-equal tempered character of Ottoman makam, expressed on the other instruments and through voice, represents a first sign of the equal-tempered makam, an expression of modal heterotopia. This theoretical incompatibility is transcended in praxis, and such theoretically unorthodox and amalgamated practices result in an aesthetic synthesis that can be viewed outside the East-West dualism as a modal heterotopia; the initial theoretically incompatible elements (equal and non-equal tempered intervals, frequently seen as expressions of westernness and easternness, respectively) are expressed, then contested as blended, without preserving their original character, into the new amalgamated whole, the result of their inversion.

Example 2: Bouzouki-Based Style

A Catholic Greek musician from the Aegean island of Syra, Markos Vamvakaris (1905–1972), was to become the most emblematic rebetiko figure and the pioneer of the three-course bouzouki. Vamvakaris, a non-literate musician, that is, someone not musically educated who learned/played only by ear, first recorded in Athens in 1932Footnote 15 while working as a butcher. Two years later, in 1934, he started performing professionally at contemporaneous musical venues with the historic rebetiko band “Tetras e Xakousti tou Peiraios” [The Famous Piraeus Four], establishing a new style based on the three-course bouzouki.

Thus, a new generation of professionals gradually appeared who were simultaneously composers, lyricists, bouzouki performers, and singers (Anestis Delias, Stelios Keromitis, etc.). Their lifeworld was largely characterised by the condition of homology, a term (Negus Reference Negus1996:23) that refers to the consistent relationship between the meaning and the expressive means of a social group; in this case, between identity and style, as with Vamvakaris—a hash smoker who composed songs about hash smoking.

Ottoman popular makam, as represented in the repertoire pertaining to the Ottoman Greeks (see Example 1) that prevailed in Greek discography until the establishment of bouzouki, impacted, wittingly or unwittingly, on the musical background of the bouzouki composers. Having grown up in such a musico-cultural context, this generation of bouzouki performers adapted the popular makam to the equal-tempered world of the three-course bouzouki. Vamvakaris (Reference Vamvakaris and Kail1978:271) often invoked the word makami (in fact the Ottoman Turkish “makamı,” frequently viewed as an expression of easternness nowadays), but essentially lent it new meaning imparted by the performance of an equal-tempered musical mode—the equal-tempered makam (see Delegos Reference Delegos2018).Footnote 16 It is no coincidence that all the bouzouki players of this generation also used the equivalent word dromos (“road” in English), not with the scale-centric meaning (a connotation of westernness) usually given by several current musicians and dromos-related book writers (e.g. Payatis [Reference Payatis1987]1992; Mystakidis Reference Mystakidis2013), but with a mode-oriented meaning, essentially introducing a secondary form of makam modality (cf. Delegos Reference Delegos2018:96–104). Hence, through the equal-tempered makam and its derivatives, a musical amalgamation emerged—an expression of modal heterotopia.

A representative example pertaining to the makam Sabâ in the bouzouki-based repertoire is “Soultana mavrofora” [Sultana Dressed in Black], recorded in 1939 in Athens, composed by Markos Vamvakaris and sung by Apostolos Hatzichristos (1901–1959) and the composer himself (Parlophone of Greece GO-3315/B.74010 II). Spiros Peristeris (1900–1966) performs on bouzouki, Kostas Skarvelis on guitar (Vamvakaris Reference Vamvakaris1939).

Musical Analysis

In the introduction, the melody on the bouzouki starts with the fifth degree (E note) as a passing note and descends through a diminished eighth (upper A flat) until the tonic (middle A), to stop temporarily on the dominant (Figure 10).Footnote 17 In the second bar, this progression is repeated, but the melody concludes on the tonic (middle A). In the vocal section (canto), in the third bar, the melody is around the dominant. Afterwards, it stops on the dominant, having passed through the tonic, and, repeating the first part of the fourth bar, concludes on the tonic.

Figure 10. Score for three-course bouzouki, vocals, and guitar, “Soultana mavrofora”, composed by Markos Vamvakaris (transcribed by author).

Therefore, the pioneer Vamvakaris apparently adheres to the main norms of the makam Sabâ behaviour, performs “phrase 1” and “phrase 2” such as in Yekta’s seyir, the “stereotyped motive,” and the activated tonal centres are in the same vein (see Figures 4, 6, 7, and 10), but all in the context of equal-temperament owing to his three-course bouzouki and the singing voices. Thus, the composer essentially employs an equal-tempered version of the makam Sabâ as an amalgamated modal form. The theoretically incompatible worlds of the makam and the equal-tempered bouzouki/singing are represented in this rebetiko performance, to be contested as they blend themselves, and finally to be transformed (“inverted”) into a new form of modality: the equal-tempered makam; in other words, a modal heterotopia, a concept outside the East–West dipole.

Harmonisation

Offering low mid-range frequencies, the guitarist follows the basokitharo style in its three roles: rhythmic accompaniment, bass melodic phrases, and chords (Figure 10). The A minor and C major chords derive from the main tonal centres of the melodic progression: the tonic and the dominant (third degree), which the melody emphasises. As the notes A and C are basic in the Sabâ scale, the character of the chord related to the A note is minor (A–C–E), also resulting from the base note of the tetrachord Sabâ. The C major chord is a product of the pentachord Hicâz on the third degree (see Figures 4 and 10).Footnote 18

The above is what I call “idiosyncratic harmonisation,” a practice which differs from the common theoretical harmonisations (scale-centric notion, symmetry in octaves, harmonic cadences, etc., all connotations of westernness), as the phenomenon demonstrates a distinct and theoretically unconventional character predicated on the modal melodic development and the corresponding “translation” of the activated tonal centres (A: base note of tetrachord Sabâ and C: base note of pentachord Hicâz) to chords (A minor and C major, respectively).

In a general sense, I portray such a harmonisation as a process whereby chords spring from the wish of the composer/arranger to “promote/translate” base notes of pentachords, tetrachords, trichords or their extensions—highlighted during the melodic unfolding—to a new activated tonal centre beyond the main one from the makam base note (cf. Delegos Reference Delegos2021:339). It is often possible to see one chord alone during the melodic progression, corresponding to the main tonal centre from the makam base note. In my example, the melody could be harmonised only with the A minor chord without seriously impacting the aesthetic outcome. Nevertheless, Vamvakaris or the relevant arranger decided to use the C major chord additionally as a “promotion” of the base note of pentachord Hicâz to a new activated tonal centre (Figure 10).

The above harmony does not totally follow the common theory (usually described as western), and essentially its representation in rebetiko performance questions its origin (contestation), but it appears idiosyncratically through a transformation where expressions of makam modality and chordal harmony are intermingled (inversion). This notably results in an amalgamated whole marking a sort of modal heterotopia, a concept lending a fresh, de-ideologised perspective beyond the East-West dichotomy.

Conclusion

The first example of makam-based music style represents a defining stage in the transformation of the Ottoman makam in rebetiko. This analysis explores the step from makam modality in Ottoman Court Music to makam in its popular vein within the environment of urban popular music in Greece. Toundas, a refugee from Smyrna, was inspired by a relatively uncommon Ottoman makam involving makam Sabâ: Nevrûz-i Rûmî. The basokitharo style guitarist defined the final aesthetic result through musical amalgamation, introducing a first sign of the equal-tempered makam as an expression of modal heterotopia.

In Example 2, the songwriter Vamvakaris essentially contests the theoretically inconsistent worlds of equal-temperament and makam as represented in bouzouki-based interwar rebetiko. He transcends this theoretical incompatibility and bridges these contradictory elements by transforming their initial identity into a new amalgamated whole. On the three-course bouzouki and with his voice, the composer Vamvakaris embraces attributes of Ottoman makam modality, adapting them to the context of equal temperament, while the guitarist Skarvelis adopts the basokitharo style in its wholeness (all three roles), reflecting the rebetiko guitarscape. The musical analysis sheds light on the concept of the “equal-tempered makam,” a secondary form of modality, and on a theoretically unconventional chordal harmony under the name of “idiosyncratic harmonisation,” thus contributing to the emergence of a modal heterotopia.

By theorising these phenomena as expressions of heterotopia, I also decolonise rebetiko in terms of the East–West hegemonic narratives that flood rebetiko-related discourse, where makam modality and chordal harmony appear as connotations of the Orient and the Occident respectively. By invoking heterotopia, which is essentially a non-ideologically charged device, there is no space for stances on rebetiko pertaining to the essentialised and imaginary concepts of the East and the West.

Finally, rethinking makam modality and chordal harmony in the context of interwar rebetiko through the prism of heterotopia deconstructs the typical theory-praxis dualism, an issue put tellingly, but in a more general framework, in the words of musicologist Harold Powers (Reference Powers1993:14–5): “Relationships between theory and practice are not a priori, they are ad hoc…”

Acknowledgements

I thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments as well as Risto Pekka Pennanen and Markus Mantere for their academic support. I am grateful to Stavros Kourousis for the Toundas gramophone record image and Philip Lauder for his advice on language issues. Thanks also to all who provided feedback at the DocMus Doctoral School, the Sibelius Academy, and conferences.