Introduction

In many scenarios, controlling Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) requires solving planning problems for complex rule-based tasks. Linear temporal logic (LTL) (Pnueli, Reference Pnueli1977) is a symbolic language for specifying such objectives. When a CPS can be modeled by Markov decision processes (MDPs), the planning problems of finding the optimal policy to maximize the probability of achieving an LTL objective can be solved by model-checking techniques (Baier and Katoen, Reference Baier and Katoen2008; Fainekos et al., Reference Fainekos, Kress-Gazit and Pappas2005; Kress-Gazit et al., Reference Kress-Gazit, Fainekos and Pappas2009).

However, LTL planning techniques such as model checking are limited when the transition probabilities of the underlying MDP are unknown. A promising alternative in such cases is reinforcement learning (RL) (Sutton and Barto, Reference Sutton and Barto2018), which finds the optimal policy through sampling. Early efforts in this direction have been confined to particular subsets of LTL (e.g. Cohen and Belta, Reference Cohen, Belta, Cohen and Belta2023; Li and Belta, Reference Li and Belta2019; Li, Vasile et al., Reference Li, Vasile and Belta2017), relied restricted semantics (e.g. Littman et al., Reference Littman, Topcu, Fu, Isbell, Wen and MacGlashan2017), or assumed prior knowledge of the MDP’s topology (e.g. Fu and Topcu, Reference Fu and Topcu2014) – understanding the presence or absence of transitions between any two given states. Model-based RL methods have also been applied by first estimating all the transitions of the MDP and applying model checking with a consideration on the estimation error (Brázdil et al., Reference Brázdil, Chatterjee, Chmelík, Forejt, Křetínský, Kwiatkowska, Parker, Ujma, Cassez and Raskin2014). However, the computation complexity can be unnecessarily high since not all transitions are equally relevant (Ashok et al., Reference Ashok, Křetínský, Weininger, Dillig and Tasiran2019).

Recent works have used model-free RL for LTL objectives on MDPs with unknown transition probabilities (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Wang, Zavlanos and Pajic2020; Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Perez, Schewe, Somenzi, Trivedi and Wojtczak2020; M Hasanbeig et al., Reference Hasanbeig, Kantaros, Abate, Kroening, Pappas and Lee2019; Sadigh et al., Reference Sadigh, Kim, Coogan, Sastry and Seshia2014). These approaches are all based on constructing

![]() $\omega$

-regular automata for the LTL objectives and translating the LTL objective into surrogate rewards within the product of the MDP and the automaton. The surrogate rewards yield the Bellman equations for the satisfaction probability of the LTL objective for a given policy, which can be solved via RL through sampling.

$\omega$

-regular automata for the LTL objectives and translating the LTL objective into surrogate rewards within the product of the MDP and the automaton. The surrogate rewards yield the Bellman equations for the satisfaction probability of the LTL objective for a given policy, which can be solved via RL through sampling.

The first approach (Sadigh et al., Reference Sadigh, Kim, Coogan, Sastry and Seshia2014) employs Rabin automata to transform LTL objectives into Rabin objectives, which are then translated into surrogate rewards, assigning constant positive rewards to certain “good” states and negative rewards to “bad” states. However, this surrogate reward function is not technically correct, as demonstrated in (Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Perez, Schewe, Somenzi, Trivedi, Wojtczak, Vojnar and Zhang2019). The second approach (M Hasanbeig et al., Reference Hasanbeig, Kantaros, Abate, Kroening, Pappas and Lee2019) employs limit-deterministic Büchi automata to translate LTL objectives into surrogate rewards that assign a constant reward for “good” states with a constant discount factor. This approach is also technically flawed, as demonstrated by (Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Perez, Schewe, Somenzi, Trivedi and Wojtczak2020). The third method (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Wang, Zavlanos and Pajic2020) also utilizes limit-deterministic Büchi automata but introduces surrogate rewards featuring a constant reward for “good” states and two discount factors that are constants but very close to 1.

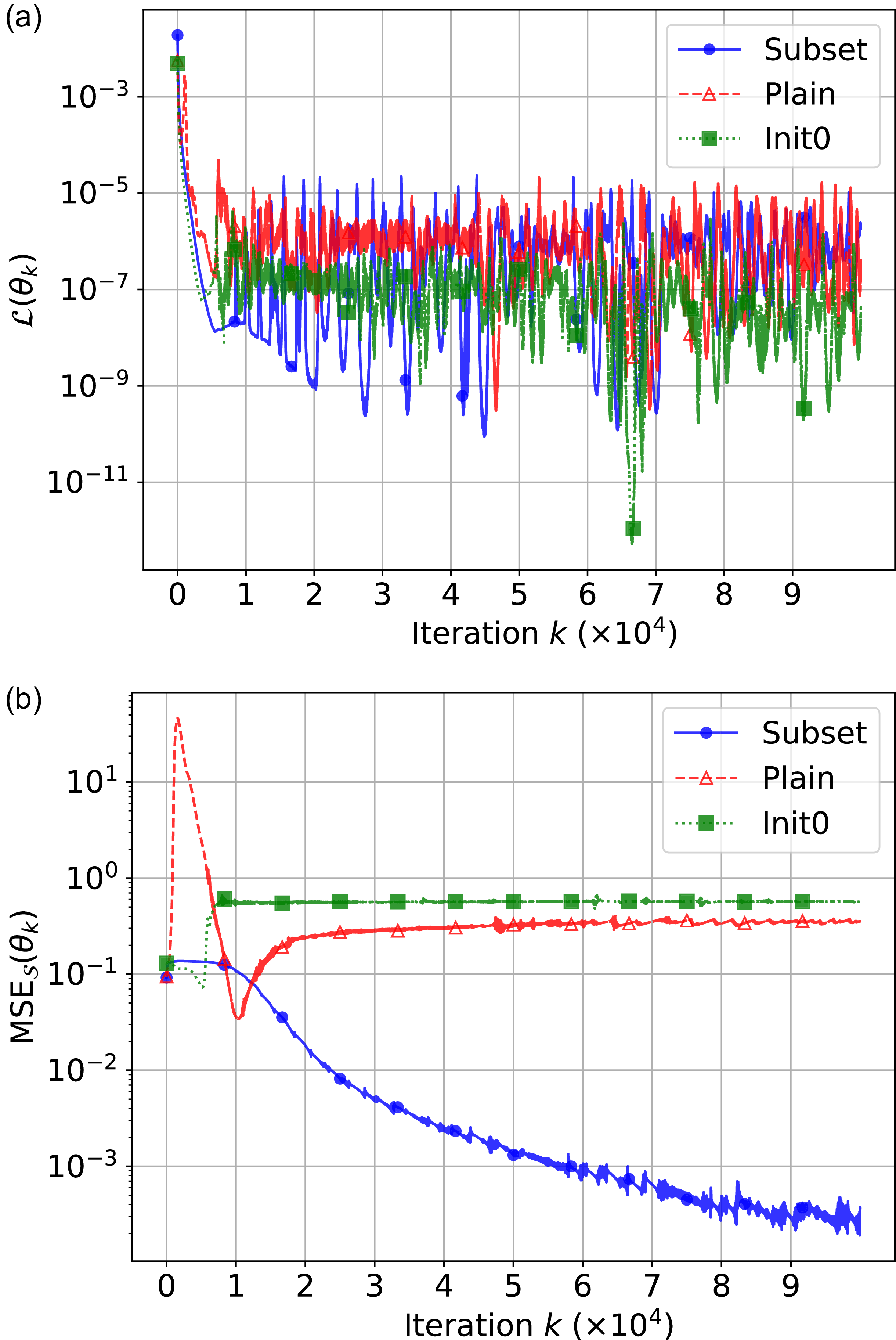

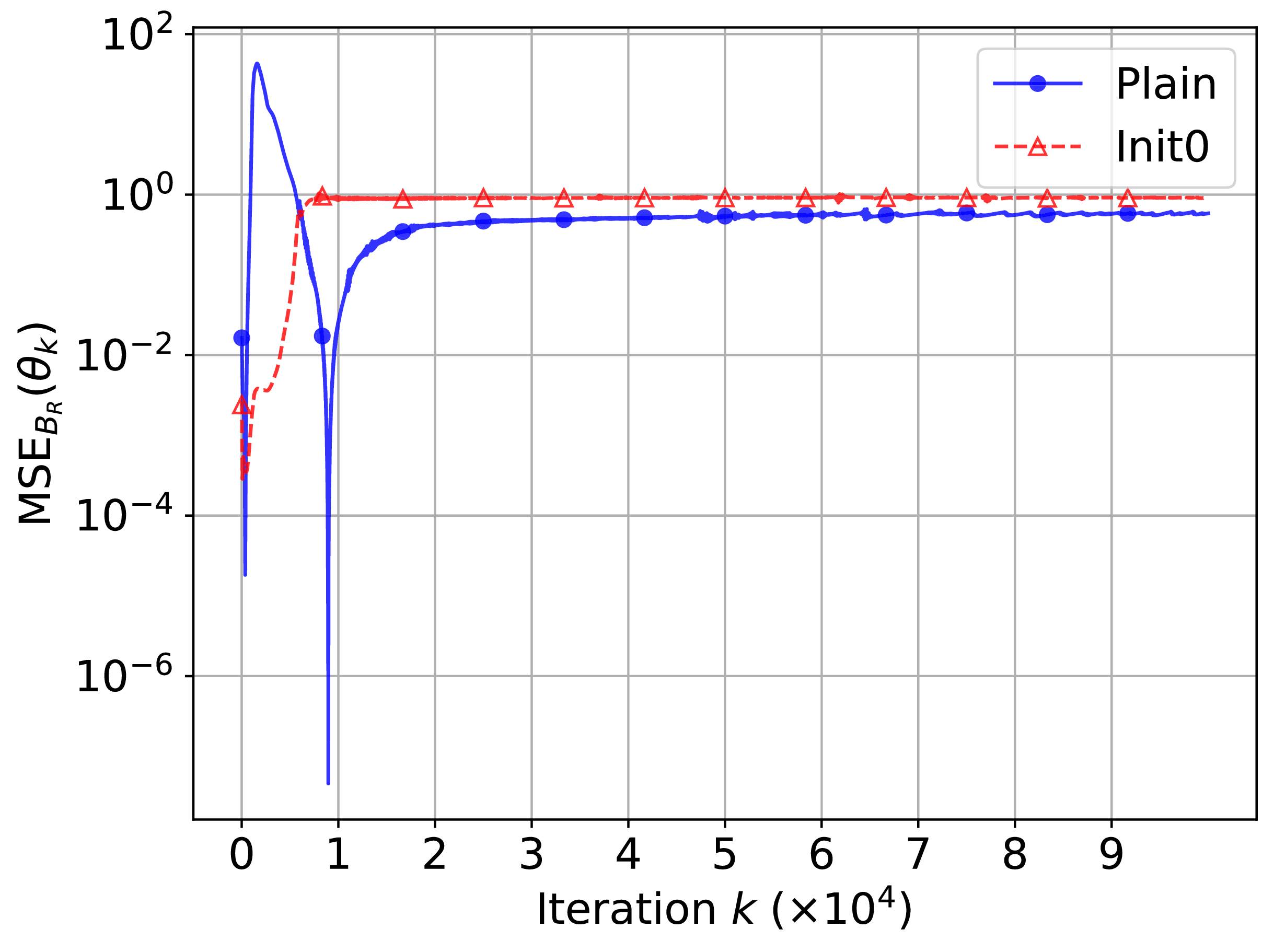

In more recent works (Cai, M Hasanbeig et al., Reference Cai, Hasanbeig, Xiao, Abate and Kan2021; H Hasanbeig et al., Reference Hasanbeig, Kroening and Abate2023; Shao and Kwiatkowska, Reference Shao and Kwiatkowska2023; Voloshin et al., Reference Voloshin, Verma and Yue2023), the surrogate reward with two discount factors from (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Wang, Zavlanos and Pajic2020) was used while allowing one discount factor to be equal to 1. We noticed that in this case, the Bellman equation may have multiple solutions, as that discount factor of 1 does not provide contraction in many states for the Bellman operator. Consequently, the RL algorithm may fail to converge or may converge to a solution that deviates from the satisfaction probabilities of the LTL objective, resulting in suboptimal policies. To illustrate this, we present a concrete example. To correctly identify the satisfaction probabilities from the multiple solutions, we propose a sufficient condition that ensures uniqueness: the solution of the Bellman equation must be 0 for all states within rejecting bottom strongly connected components (BSCCs).

We prove that, under this sufficient condition, the Bellman equation has a unique solution that approximates the satisfaction probabilities of LTL objectives by the following procedure. When one of the discount factors equals 1, we partition the state space into states with discounting and states without discounting based on surrogate reward. In this case, We first establish the relationships among all states with discounting and show that their solution is unique since the Bellman operator remains contractive in these states. Then, we show that the entire solution is unique since the solution on states without discounting is uniquely determined by states with discounting.

Finally, we present a case study demonstrating that correctly solving the Bellman equation requires the uniqueness condition. We further show that when neural networks are used to approximate the Bellman equation’s solution, as is common in deep RL for LTL objectives, this condition is automatically violated.

Related works

We study a special form of the Bellman equation encoutered in LTL planning problem that may admit multiple solutions. In contrast, prior works have primarily analyzed the accuracy of solving a Bellman equation with a unique solution. The relationship between the accuracy of solving the Bellman equation with respect to the Bellman equation residuals has been discussed by many works (Bertsekas, Reference Bertsekas, Floudas and Pardalos2001; Heger, Reference Heger1996; Munos, Reference Munos2003, Reference Munos2007; Singh and Yee, Reference Singh and Yee1994). Later work exposes several limits when solving Bellman equation via samples. Off-policy training can be unstable and depends on the sampling distribution (Geist et al., Reference Geist, Piot and Pietquin2017; Kolter, Reference Kolter, Shawe-Taylor, Zemel, Bartlett, Pereira and Weinberger2011). Under aliasing, the Bellman residual may be unlearnable (Sutton and Barto, Reference Sutton and Barto2018). In offline RL, Bellman error has weak correspondence to value accuracy and control performance (Fujimoto et al., Reference Fujimoto, Meger, Precup, Nachum and Gu2022). These results assume a unique fixed point. In contrast, we show that in the LTL surrogate reward setting the Bellman equation can be non-contractive on parts of the state space, so Bellman equation may have multiple solutions.

Part of the theoretical results have appeared in our previous paper (Xuan, Bozkurt et al., Reference Xuan, Bozkurt, Pajic and Wang2024) without proofs and demonstration on case studies.

Preliminaries

This section introduces preliminaries on labeled Markov decision processes, linear temporal logic, and probabilistic model checking.

Labeled Markov decision processes

Labeled Markov decision processes (LMDPs) are used to model planning problems where each decision has a potentially probabilistic outcome. LMDPs augment standard Markov decision processes (Baier and Katoen, Reference Baier and Katoen2008) with state labels, allowing properties such as safety and liveness to be assigned to a sequences of states.

Definition 1. A labeled Markov decision process is a tuple

![]() ${\mathcal{M}} = (S, A, P, s_{\rm init}, \Lambda, L)$

where

${\mathcal{M}} = (S, A, P, s_{\rm init}, \Lambda, L)$

where

-

S is a finite set of states and

$s_{\rm init}\,\in\, S$

is the initial state,

$s_{\rm init}\,\in\, S$

is the initial state,

-

A is a finite set of actions where A(s) denotes the set of allowed actions in state

$s\in S$

,

$s\in S$

, -

$P: S \times A \times S \to [0,1]$

is the transition probability function such that for all

$P: S \times A \times S \to [0,1]$

is the transition probability function such that for all

$s\in S$

,

$s\in S$

, $$ \sum\limits_{s' \in S} P (s,a,s') = \left\{ {\matrix{ {1,} \hfill & {a \in A(s)} \hfill \cr {0,} \hfill & {a \; \notin \; A(s)} \hfill \cr } } \right.,$$

$$ \sum\limits_{s' \in S} P (s,a,s') = \left\{ {\matrix{ {1,} \hfill & {a \in A(s)} \hfill \cr {0,} \hfill & {a \; \notin \; A(s)} \hfill \cr } } \right.,$$

-

$\Lambda$

is a finite set of atomic propositions,

$\Lambda$

is a finite set of atomic propositions, -

$L: S \to 2^{\Lambda}$

is a labeling function.

$L: S \to 2^{\Lambda}$

is a labeling function.

A path of the LMDP

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}$

is an infinite state sequence

${\mathcal{M}}$

is an infinite state sequence

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}} = s_0 s_1 s_2 \cdots$

such that for all

${\unicode{x03C3}} = s_0 s_1 s_2 \cdots$

such that for all

![]() $i \ge 0$

, there exists

$i \ge 0$

, there exists

![]() $a_i\,\in\, A(s)$

and

$a_i\,\in\, A(s)$

and

![]() $s_{i}, s_{i+1}\,\in\, S$

with

$s_{i}, s_{i+1}\,\in\, S$

with

![]() $P(s_i,a_i,s_{i+1}) \gt 0$

. The semantic path corresponding to

$P(s_i,a_i,s_{i+1}) \gt 0$

. The semantic path corresponding to

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

is given by

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

is given by

![]() $L({\unicode{x03C3}}) = L(s_0)L( s_1)\cdots$

, derived using the labeling function L(s). Given a path

$L({\unicode{x03C3}}) = L(s_0)L( s_1)\cdots$

, derived using the labeling function L(s). Given a path

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

, the ith state is denoted by

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

, the ith state is denoted by

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}[i] = s_i$

. We denote the prefix by

${\unicode{x03C3}}[i] = s_i$

. We denote the prefix by

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}[{:}i] = s_0 s_1\cdots s_i$

and suffix by

${\unicode{x03C3}}[{:}i] = s_0 s_1\cdots s_i$

and suffix by

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}[i{+}1{:}] = s_{i+1} s_{i+2}\cdots$

.

${\unicode{x03C3}}[i{+}1{:}] = s_{i+1} s_{i+2}\cdots$

.

LTL and limit-deterministic Büchi automata

In an LMDP

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}$

, whether a given semantic path

${\mathcal{M}}$

, whether a given semantic path

![]() $L({\unicode{x03C3}})$

satisfies a property such as avoiding unsafe states can be expressed using LTL. LTL can specify the change of labels along the path by connecting Boolean variables over the labels with two propositional operators, negation

$L({\unicode{x03C3}})$

satisfies a property such as avoiding unsafe states can be expressed using LTL. LTL can specify the change of labels along the path by connecting Boolean variables over the labels with two propositional operators, negation

![]() $(\neg)$

and conjunction

$(\neg)$

and conjunction

![]() $(\wedge)$

, and two temporal operators, next

$(\wedge)$

, and two temporal operators, next

![]() $(\bigcirc)$

and until

$(\bigcirc)$

and until

![]() $(\cup)$

.

$(\cup)$

.

Definition 2. The LTL formula is defined by the syntax

Satisfaction of an LTL formula

![]() ${\unicode{x03C6}}$

on a path

${\unicode{x03C6}}$

on a path

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

of an MDP (denoted by

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

of an MDP (denoted by

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\unicode{x03C6}}$

) is defined as,

${\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\unicode{x03C6}}$

) is defined as,

![]() $\alpha\in \Lambda$

is satisfied on

$\alpha\in \Lambda$

is satisfied on

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

if

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

if

![]() $\alpha\in L({\unicode{x03C3}}[1])$

,

$\alpha\in L({\unicode{x03C3}}[1])$

,

![]() $\bigcirc {\unicode{x03C6}}$

is satisfied on

$\bigcirc {\unicode{x03C6}}$

is satisfied on

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

if

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

if

![]() ${\unicode{x03C6}}$

is satisfied on

${\unicode{x03C6}}$

is satisfied on

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}[1{:}]$

,

${\unicode{x03C3}}[1{:}]$

,

![]() ${\unicode{x03C6}}_1 \cup {\unicode{x03C6}}_2$

is satisfied on

${\unicode{x03C6}}_1 \cup {\unicode{x03C6}}_2$

is satisfied on

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

if there exists i such that

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

if there exists i such that

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}[i{:}] \models {\unicode{x03C6}}_2$

and for all

${\unicode{x03C3}}[i{:}] \models {\unicode{x03C6}}_2$

and for all

![]() $j \lt i,{\mkern 1mu} {\unicode{x03C3}} [j:] \models {{\unicode{x03C6}} _1}$

.

$j \lt i,{\mkern 1mu} {\unicode{x03C3}} [j:] \models {{\unicode{x03C6}} _1}$

.

Other propositional and temporal operators can be derived from previous operators, e.g., (or)

![]() ${\unicode{x03C6}}_1 \vee {\unicode{x03C6}}_2 := \neg(\neg {\unicode{x03C6}}_1 \wedge \neg {\unicode{x03C6}}_2)$

, (eventually)

${\unicode{x03C6}}_1 \vee {\unicode{x03C6}}_2 := \neg(\neg {\unicode{x03C6}}_1 \wedge \neg {\unicode{x03C6}}_2)$

, (eventually)

![]() $\lozenge {\unicode{x03C6}} := {\rm true} \cup {\unicode{x03C6}}$

and (always)

$\lozenge {\unicode{x03C6}} := {\rm true} \cup {\unicode{x03C6}}$

and (always)

![]() $ \square {\unicode{x03C6}} := \neg \lozenge \neg {\unicode{x03C6}}$

.

$ \square {\unicode{x03C6}} := \neg \lozenge \neg {\unicode{x03C6}}$

.

We can use Limit-Deterministic Büchi Automata (LDBA) to check the satisfaction of an LTL formula on a path.

Definition 3. An LDBA is a tuple

![]() $\mathcal{A} = ({\mathcal Q},\Sigma,{\rm\delta},{\rm q_0},B)$

where

$\mathcal{A} = ({\mathcal Q},\Sigma,{\rm\delta},{\rm q_0},B)$

where

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

is a finite set of automaton states,

$\mathcal{Q}$

is a finite set of automaton states,

![]() $\Sigma$

is a finite alphabet,

$\Sigma$

is a finite alphabet,

![]() ${\rm\delta}:{\mathcal Q}\times (\Sigma \cup \{\epsilon\})\to {2}^{\mathcal{Q}}$

is a (partial) transition function,

${\rm\delta}:{\mathcal Q}\times (\Sigma \cup \{\epsilon\})\to {2}^{\mathcal{Q}}$

is a (partial) transition function,

![]() $q_0$

is an initial state, and B is a set of accepting states,

$q_0$

is an initial state, and B is a set of accepting states,

![]() ${\rm\delta}$

is total except for the

${\rm\delta}$

is total except for the

![]() $\epsilon$

-transitions (

$\epsilon$

-transitions (

![]() $|{\rm\delta}(q,\alpha)|=1$

for all

$|{\rm\delta}(q,\alpha)|=1$

for all

![]() $q\in {\mathcal{Q}}, \alpha\,\in\, \Sigma$

), and there exists a bipartition of

$q\in {\mathcal{Q}}, \alpha\,\in\, \Sigma$

), and there exists a bipartition of

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

to an initial and an accepting component

$\mathcal{Q}$

to an initial and an accepting component

![]() ${\mathcal{Q}}_{{ini}}\cup {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}} = {\mathcal{Q}}$

such that

${\mathcal{Q}}_{{ini}}\cup {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}} = {\mathcal{Q}}$

such that

-

there is no transition from

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{acc}}$

to

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{acc}}$

to

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{ini}}$

, i.e., for any

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{ini}}$

, i.e., for any

$q\in {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}, v\in \Sigma, {\rm\delta}( q,v)\subseteq {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}$

,

$q\in {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}, v\in \Sigma, {\rm\delta}( q,v)\subseteq {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}$

, -

all the accepting states are in

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{acc}}$

, i.e.,

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{acc}}$

, i.e.,

$B\subseteq {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}$

,

$B\subseteq {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}$

, -

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{acc}}$

does not have any outgoing

$\mathcal{Q}_{\it{acc}}$

does not have any outgoing

$\epsilon$

-transitions, i.e.,

$\epsilon$

-transitions, i.e.,

${\rm\delta}(q,\epsilon)=\emptyset$

for any

${\rm\delta}(q,\epsilon)=\emptyset$

for any

$q\in {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}$

.

$q\in {\mathcal{Q}}_{\it{acc}}$

.

A run is an infinite sequence of transitions

![]() ${\unicode{x03C1}} = (q_0,w_0,q_1), (q_1,w_1, q_2) \cdots$

such that for all

${\unicode{x03C1}} = (q_0,w_0,q_1), (q_1,w_1, q_2) \cdots$

such that for all

![]() $i \ge 0$

,

$i \ge 0$

,

![]() $q_{i+1}\,\in\, {\rm\delta}(q_i, w_i)$

. The run

$q_{i+1}\,\in\, {\rm\delta}(q_i, w_i)$

. The run

![]() ${\unicode{x03C1}}$

is accepted by the LDBA if it satisfies the Büchi condition, i.e.,

${\unicode{x03C1}}$

is accepted by the LDBA if it satisfies the Büchi condition, i.e.,

![]() ${\rm inf}(\rm {\unicode{x03C1}}) \cap B \ne \emptyset$

, where

${\rm inf}(\rm {\unicode{x03C1}}) \cap B \ne \emptyset$

, where

![]() ${\rm inf}(\rm {\unicode{x03C1}})$

denotes the set of automaton states visited by

${\rm inf}(\rm {\unicode{x03C1}})$

denotes the set of automaton states visited by

![]() ${\unicode{x03C1}}$

infinitely many times.

${\unicode{x03C1}}$

infinitely many times.

A path

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}=s_0s_1\dots$

of an LMDP

${\unicode{x03C3}}=s_0s_1\dots$

of an LMDP

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}$

is considered accepted by an LDBA

${\mathcal{M}}$

is considered accepted by an LDBA

![]() $\mathcal{A}$

if the semantic path

$\mathcal{A}$

if the semantic path

![]() $L({\unicode{x03C3}})$

is the corresponding word w of an accepting run

$L({\unicode{x03C3}})$

is the corresponding word w of an accepting run

![]() ${\unicode{x03C1}}$

after elimination of

${\unicode{x03C1}}$

after elimination of

![]() $\epsilon$

-transitions.

$\epsilon$

-transitions.

Lemma 1. (Sickert et al., Reference Sickert, Esparza, Jaax and Křetínský2016, Theorem 1

) Given an LTL objective

![]() ${\varphi}$

, there exists an LDBA

${\varphi}$

, there exists an LDBA

![]() $\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

(with labels

$\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

(with labels

![]() $\Sigma=2^{\Lambda}$

) such that a path

$\Sigma=2^{\Lambda}$

) such that a path

![]() ${\sigma} \models {\varphi}$

if and only if

${\sigma} \models {\varphi}$

if and only if

![]() ${\sigma}$

is accepted by the LDBA

${\sigma}$

is accepted by the LDBA

![]() $\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

.

$\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

.

Product MDP

Planning problems for LTL objectives typically requires a (history-dependent) policy, which determines the current action based on all previous state visits.

Definition 4. A policy

![]() $\pi$

is a function

$\pi$

is a function

![]() $\pi:S^+ \to {A}$

such that

$\pi:S^+ \to {A}$

such that

![]() $\pi({\sigma}[{:}n])\in {A}({\sigma}[n])$

, where

$\pi({\sigma}[{:}n])\in {A}({\sigma}[n])$

, where

![]() $S^+$

stands for the set all non-empty finite sequences taken from S. A memoryless policy is a policy that only depends on the current state

$S^+$

stands for the set all non-empty finite sequences taken from S. A memoryless policy is a policy that only depends on the current state

![]() $\pi:S \to {A}$

. Given a LMDP

$\pi:S \to {A}$

. Given a LMDP

![]() ${\mathcal{M}} = ({ \mathcal{S, A, P}}, s_{\rm 0}, \Lambda, {\mathcal{L}})$

and a memoryless policy

${\mathcal{M}} = ({ \mathcal{S, A, P}}, s_{\rm 0}, \Lambda, {\mathcal{L}})$

and a memoryless policy

![]() $\pi$

, the Markov chain (MC) induced by policy

$\pi$

, the Markov chain (MC) induced by policy

![]() $\pi$

is a tuple

$\pi$

is a tuple

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}_\pi=(S, P_\pi,s_{\rm 0},\Lambda,L)$

where

${\mathcal{M}}_\pi=(S, P_\pi,s_{\rm 0},\Lambda,L)$

where

![]() $P_\pi(s,s')=P(s,\pi(s),s')$

for all

$P_\pi(s,s')=P(s,\pi(s),s')$

for all

![]() $s,s'\in S$

.

$s,s'\in S$

.

Using the LDBA, we construct a product MDP that augments the MDP state space along with the automaton state space. The state of the product MDP encodes both the physical state and the progression of the LTL objective. In this manner, we “lift” the planning problem to the product MDP. Given that the state of the product MDP now encodes all the information necessary for planning, the action can be determined by the current state of the product MDP, resulting in memoryless policies. Formally, the product MDP is defined as follows:

Definition 5. A product MDP

![]() $ {\mathcal{M}}^{\times} = ( S^{\times}, A^{\times}, P^{\times},{\it s}_{\rm 0}^{\times}, B^{\times})$

of an LMDP

$ {\mathcal{M}}^{\times} = ( S^{\times}, A^{\times}, P^{\times},{\it s}_{\rm 0}^{\times}, B^{\times})$

of an LMDP

![]() $ {\mathcal{M}} = ( S, A, P, {\it s}_{\rm 0}, \Lambda, L)$

and an LDBA

$ {\mathcal{M}} = ( S, A, P, {\it s}_{\rm 0}, \Lambda, L)$

and an LDBA

![]() ${\mathcal{A}}= (\mathcal{Q}, \Sigma,{\rm\delta},{\it q}_{\rm 0},B)$

is defined by the set of states

${\mathcal{A}}= (\mathcal{Q}, \Sigma,{\rm\delta},{\it q}_{\rm 0},B)$

is defined by the set of states

![]() $S^\times = S \times {\mathcal{Q}}$

, the set of actions

$S^\times = S \times {\mathcal{Q}}$

, the set of actions

![]() ${A}^\times = { {A}} \cup \{\epsilon_q|q\in {\mathcal{Q}}\}$

, the transition probability function

${A}^\times = { {A}} \cup \{\epsilon_q|q\in {\mathcal{Q}}\}$

, the transition probability function

$${P^ \times }(\langle s,q\rangle, a,\langle s',q'\rangle ) = \left\{ {\matrix{ {P(s,a,s')} \hfill & \!\! {q' = {\rm\delta} (q,L(s)),a \,\notin\, {A^{\rm\epsilon}}} \hfill \cr 1 \hfill & {a = {{\rm\epsilon}_{q'}},q'\,\in\, {\rm\delta} (q,),s = s'} \hfill \cr 0 \hfill & {{\rm{otherwise}}} \hfill \cr } } \right.,$$

$${P^ \times }(\langle s,q\rangle, a,\langle s',q'\rangle ) = \left\{ {\matrix{ {P(s,a,s')} \hfill & \!\! {q' = {\rm\delta} (q,L(s)),a \,\notin\, {A^{\rm\epsilon}}} \hfill \cr 1 \hfill & {a = {{\rm\epsilon}_{q'}},q'\,\in\, {\rm\delta} (q,),s = s'} \hfill \cr 0 \hfill & {{\rm{otherwise}}} \hfill \cr } } \right.,$$

the initial state

![]() $s_0^\times=\langle s_0,q_0 \rangle$

, and the set of accepting states

$s_0^\times=\langle s_0,q_0 \rangle$

, and the set of accepting states

![]() $B^\times=\{\langle s,q \rangle\,\in\, S^\times |q\in B\}$

. We say a path

$B^\times=\{\langle s,q \rangle\,\in\, S^\times |q\in B\}$

. We say a path

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

satisfies the Büchi condition

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

satisfies the Büchi condition

![]() ${\unicode{x03C6}}_B$

if

${\unicode{x03C6}}_B$

if

![]() ${\rm inf}({\unicode{x03C3}})\cap B^\times\ne\emptyset$

. Here,

${\rm inf}({\unicode{x03C3}})\cap B^\times\ne\emptyset$

. Here,

![]() ${\rm inf}({\unicode{x03C3}})$

denotes the set of states visited infinitely many times on

${\rm inf}({\unicode{x03C3}})$

denotes the set of states visited infinitely many times on

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}$

.

${\unicode{x03C3}}$

.

The transitions of the product MDP

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}^\times $

are derived by combining the transitions of the MDP

${\mathcal{M}}^\times $

are derived by combining the transitions of the MDP

![]() $ {\mathcal{M}} $

and the LDBA

$ {\mathcal{M}} $

and the LDBA

![]() $ \mathcal{A} $

. Specifically, the multiple

$ \mathcal{A} $

. Specifically, the multiple

![]() $ \epsilon $

-transitions starting from the same states in the LDBA are differentiated by their respective end states q and are denoted as

$ \epsilon $

-transitions starting from the same states in the LDBA are differentiated by their respective end states q and are denoted as

![]() $ \epsilon_q$

. These

$ \epsilon_q$

. These

![]() $ \epsilon $

-transitions in the LDBA give rise to corresponding

$ \epsilon $

-transitions in the LDBA give rise to corresponding

![]() $ \epsilon $

-actions in the product MDP, each occurring with a probability of 1. The limit-deterministic nature of LDBAs ensures that the presence of these

$ \epsilon $

-actions in the product MDP, each occurring with a probability of 1. The limit-deterministic nature of LDBAs ensures that the presence of these

![]() $\epsilon$

-actions within the product MDPs does not prevent the quantitative analysis of the MDPs for planning. In other words, any optimal policy for a product MDP induces an optimal policy for the original MDP, as formally stated below.

$\epsilon$

-actions within the product MDPs does not prevent the quantitative analysis of the MDPs for planning. In other words, any optimal policy for a product MDP induces an optimal policy for the original MDP, as formally stated below.

Lemma 2. (Sickert et al., Reference Sickert, Esparza, Jaax and Křetínský2016). Given an LMDP

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}$

and an LTL objective

${\mathcal{M}}$

and an LTL objective

![]() ${\unicode{x03C6}}$

, let

${\unicode{x03C6}}$

, let

![]() $\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

be the LDBA derived from

$\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

be the LDBA derived from

![]() ${\unicode{x03C6}}$

and let

${\unicode{x03C6}}$

and let

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}^\times$

be the product MDP constructed from

${\mathcal{M}}^\times$

be the product MDP constructed from

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}$

and

${\mathcal{M}}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

, with the set of accepting states

$\mathcal{A}_{\unicode{x03C6}}$

, with the set of accepting states

![]() $B^\times$

. Then, a memoryless policy

$B^\times$

. Then, a memoryless policy

![]() $\pi^\times$

that maximizes the probability of satisfying the Büchi condition on

$\pi^\times$

that maximizes the probability of satisfying the Büchi condition on

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}^\times$

,

${\mathcal{M}}^\times$

,

![]() $P_{{\unicode{x03C3}}^\times} \big({\unicode{x03C3}}^\times \models \square \lozenge B^\times \big)$

where

$P_{{\unicode{x03C3}}^\times} \big({\unicode{x03C3}}^\times \models \square \lozenge B^\times \big)$

where

![]() ${\unicode{x03C3}}^\times {\sim} \mathcal{M}_{\pi^\times}^\times$

, induces a finite-memory policy

${\unicode{x03C3}}^\times {\sim} \mathcal{M}_{\pi^\times}^\times$

, induces a finite-memory policy

![]() $\pi$

that maximizes the satisfaction probability

$\pi$

that maximizes the satisfaction probability

![]() $P_{{\unicode{x03C3}} \sim \mathcal{M}_{\pi}} \big({\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\unicode{x03C6}} \big)$

on

$P_{{\unicode{x03C3}} \sim \mathcal{M}_{\pi}} \big({\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\unicode{x03C6}} \big)$

on

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}$

.

${\mathcal{M}}$

.

Problem formulation

In the previous section, we have shown LTL objectives on an LMDP can be converted into a Büchi condition on the Product MDP. In this section, we focus on a surrogate reward commonly used for Büchi condition proposed in (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Wang, Zavlanos and Pajic2020) and study the uniqueness of solution for the Bellman equation of this surrogate reward, which has not been sufficiently discussed in previous work (H Hasanbeig et al., Reference Hasanbeig, Kroening and Abate2023; Shao and Kwiatkowska, Reference Shao and Kwiatkowska2023; Voloshin et al., Reference Voloshin, Verma and Yue2023).

For simplicity, we drop

![]() $\times$

from the product MDP notation and define the satisfaction probability for the Büchi condition as

$\times$

from the product MDP notation and define the satisfaction probability for the Büchi condition as

When the product MDP model is unknown, the traditional model-based method through graph search (Baier and Katoen, Reference Baier and Katoen2008) is not applicable. Alternatively, we may use model-free RL with a two-discount-factor surrogate reward proposed by (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Wang, Zavlanos and Pajic2020), which has been widely adopted in (Cai, M Hasanbeig et al., Reference Cai, Hasanbeig, Xiao, Abate and Kan2021; Cai, Xiao et al., Reference Cai, Xiao, Li and Kan2023; H Hasanbeig et al., Reference Hasanbeig, Kroening and Abate2023; Shao and Kwiatkowska, Reference Shao and Kwiatkowska2023; Voloshin et al., Reference Voloshin, Verma and Yue2023). This approach involves a reward function

![]() $R: S\to\mathbb{R}$

and a state-dependent discount factor function

$R: S\to\mathbb{R}$

and a state-dependent discount factor function

![]() $\Gamma: S\to (0,1]$

with

$\Gamma: S\to (0,1]$

with

![]() $0 \lt {{\rm\gamma} _B} \lt {\rm\gamma} \le 1$

,

$0 \lt {{\rm\gamma} _B} \lt {\rm\gamma} \le 1$

,

A positive reward is collected only when an accepting state is visited along the path. The K-step return (

![]() $K\in \mathbb{N}$

or

$K\in \mathbb{N}$

or

![]() $K=\infty$

) of a path from time

$K=\infty$

) of a path from time

![]() $t\in \mathbb{N}$

is

$t\in \mathbb{N}$

is

$$\matrix{ \hfill {{G_{t:K}}({\unicode{x03C3}} )}\hskip-6pt & { = \sum\limits_{i = 0}^K R ({\unicode{x03C3}} [t + i]) \cdot \prod\limits_{j = 0}^{i - 1} \Gamma ({\unicode{x03C3}} [t + j]),} \hfill \cr \hfill {{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )} \hskip-6pt & { = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{K \to \infty } {G_{t:K}}({\unicode{x03C3}} ).} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ \hfill {{G_{t:K}}({\unicode{x03C3}} )}\hskip-6pt & { = \sum\limits_{i = 0}^K R ({\unicode{x03C3}} [t + i]) \cdot \prod\limits_{j = 0}^{i - 1} \Gamma ({\unicode{x03C3}} [t + j]),} \hfill \cr \hfill {{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )} \hskip-6pt & { = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{K \to \infty } {G_{t:K}}({\unicode{x03C3}} ).} \hfill \cr } $$

The definition is similar to standard discounted rewards (Sutton and Barto, Reference Sutton and Barto2018) but involves state-dependent discounting factors. If

![]() ${\rm\gamma}=1$

, then for a path that satisfies the Büchi objective, the return is the summation of a geometric series

${\rm\gamma}=1$

, then for a path that satisfies the Büchi objective, the return is the summation of a geometric series

![]() $\sum\nolimits_{i = 0}^\infty {(1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})} {\rm\gamma} _B^i = {{1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B}} \over {1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B}}} = 1$

.

$\sum\nolimits_{i = 0}^\infty {(1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})} {\rm\gamma} _B^i = {{1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B}} \over {1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B}}} = 1$

.

Accordingly, the value function

![]() $V_\pi(s)$

is the expected return conditional on the path starting at s under the policy

$V_\pi(s)$

is the expected return conditional on the path starting at s under the policy

![]() $\pi$

.

$\pi$

.

$$\matrix{ {{V_\pi }(s)} \hfill & \!\!\!\!{ = {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )|{\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!{ = {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] \cdot P(s \models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B)} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\! { + \,\, {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \mid\!=\!\!\!\!\!\!\!/\,\,\, {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] \cdot P(s \mid\!=\!\!\!\!\!\!\!/\,\,\, {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B),} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ {{V_\pi }(s)} \hfill & \!\!\!\!{ = {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )|{\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!{ = {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] \cdot P(s \models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B)} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\! { + \,\, {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \mid\!=\!\!\!\!\!\!\!/\,\,\, {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] \cdot P(s \mid\!=\!\!\!\!\!\!\!/\,\,\, {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B),} \hfill \cr } $$

where

![]() $P(s \not\models \square \lozenge B)$

stands for the probability of a path not satisfying the Büchi objective conditional on the path starting at s.

$P(s \not\models \square \lozenge B)$

stands for the probability of a path not satisfying the Büchi objective conditional on the path starting at s.

The value function approximates the satisfaction probability defined in (2) to guide the search for policy. As the value

![]() ${\rm\gamma}_B$

,

${\rm\gamma}_B$

,

![]() ${\rm\gamma}$

becomes close to 1, the value function becomes close to

${\rm\gamma}$

becomes close to 1, the value function becomes close to

![]() $P(s\models \square \lozenge B)$

as

$P(s\models \square \lozenge B)$

as

$$\eqalign{ & \mathop {\lim }\limits_{{\rm\gamma} \to {1^ - }} {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] = 1 \cr & \mathop {\lim }\limits_{{{\rm\gamma} _B} \to {1^ - }} {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \not\models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] = 0. \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{ & \mathop {\lim }\limits_{{\rm\gamma} \to {1^ - }} {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] = 1 \cr & \mathop {\lim }\limits_{{{\rm\gamma} _B} \to {1^ - }} {{\mathbb E}_\pi }[{G_t}({\unicode{x03C3}} )\mid {\unicode{x03C3}} [t] = s,{\unicode{x03C3}} \not\models {\rm{\square}}\lozenge B] = 0. \cr} $$

Given a policy, the value function satisfies the Bellman equation.Footnote 1 The Bellman equation is derived from the fact that the value of the current state is equal to the expectation of the current reward plus the discounted value of the next state. For the surrogate reward in the equation (3), the Bellman equation is given as follows:

Previous work (H Hasanbeig et al., Reference Hasanbeig, Kroening and Abate2023; Shao and Kwiatkowska, Reference Shao and Kwiatkowska2023; Voloshin et al., Reference Voloshin, Verma and Yue2023) allows

![]() ${\rm\gamma}=1$

. However, setting

${\rm\gamma}=1$

. However, setting

![]() ${\rm\gamma}=1$

can cause multiple solutions to the Bellman equations, raising concerns about applying model-free RL. This motivates us to study the following problem.

${\rm\gamma}=1$

can cause multiple solutions to the Bellman equations, raising concerns about applying model-free RL. This motivates us to study the following problem.

Problem Formulation

For a given (product) MDP

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}$

from Definition 5 and the surrogate reward from (3), and a policy

${\mathcal{M}}$

from Definition 5 and the surrogate reward from (3), and a policy

![]() $\pi$

, find the sufficient conditions under which the Bellman equation from (7) has a unique solution.

$\pi$

, find the sufficient conditions under which the Bellman equation from (7) has a unique solution.

The following example shows the Bellman equation (7) has multiple solutions when

![]() ${\rm\gamma} = 1$

(3). An incorrect solution, different than the expected return from (5), hinders accurate policy evaluation and restricts the application of RL and other optimization techniques.

${\rm\gamma} = 1$

(3). An incorrect solution, different than the expected return from (5), hinders accurate policy evaluation and restricts the application of RL and other optimization techniques.

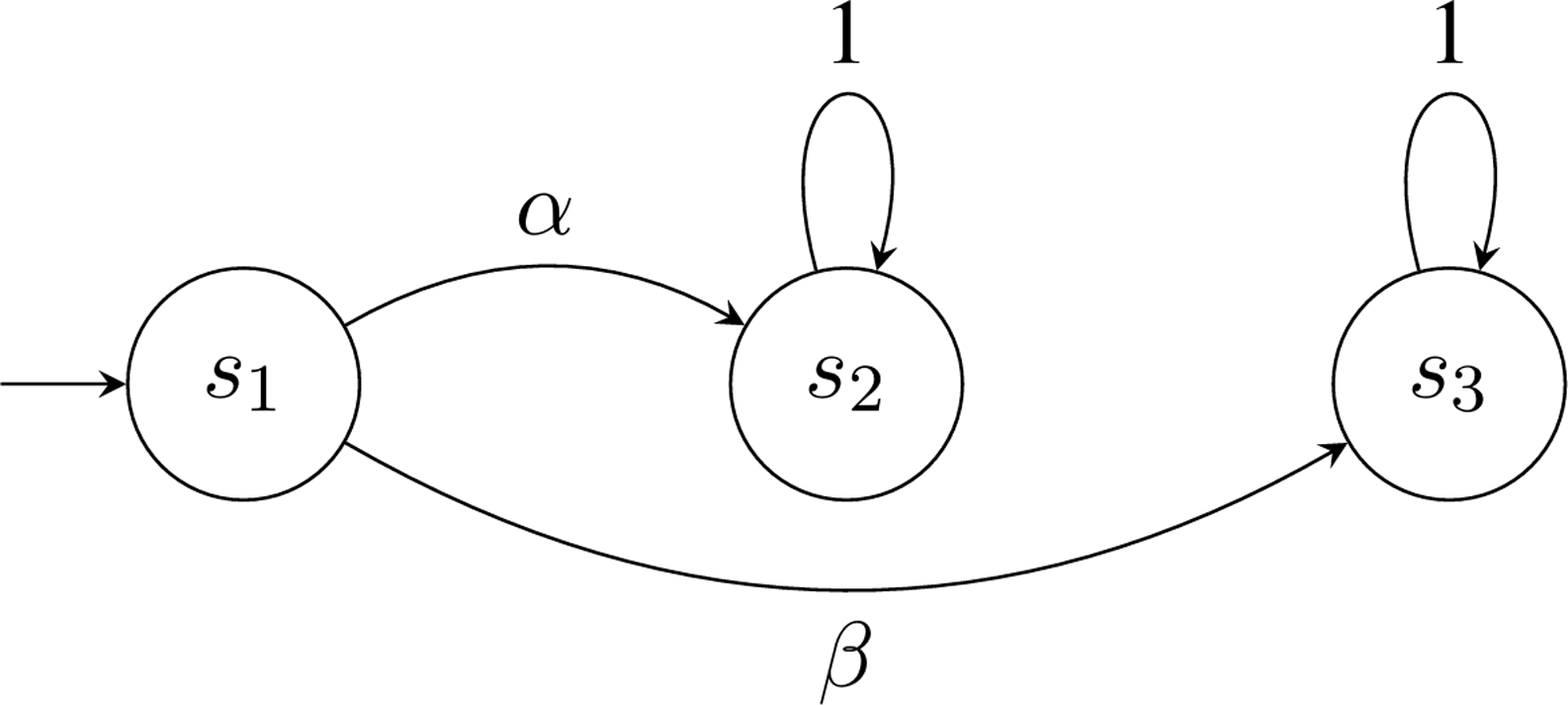

Example 1. Consider a (product) MDP with three states

![]() $S = \{s_1, s_2, s_3\}$

where

$S = \{s_1, s_2, s_3\}$

where

![]() $s_1$

is the initial state and

$s_1$

is the initial state and

![]() $B = \{s_2\}$

is the set of accepting states as shown in Figure 1. In

$B = \{s_2\}$

is the set of accepting states as shown in Figure 1. In

![]() $s_1$

, the action

$s_1$

, the action

![]() $\alpha$

leads to

$\alpha$

leads to

![]() $s_2$

and the action

$s_2$

and the action

![]() $\beta$

leads to

$\beta$

leads to

![]() $s_3$

. Since

$s_3$

. Since

![]() $s_2$

is the only accepting state,

$s_2$

is the only accepting state,

![]() $\alpha$

is the optimal action that maximizes the expected return. However, there exists a solution to the corresponding Bellman equation suggesting

$\alpha$

is the optimal action that maximizes the expected return. However, there exists a solution to the corresponding Bellman equation suggesting

![]() $\rm\beta$

is the optimal action, as follows:

$\rm\beta$

is the optimal action, as follows:

$$\matrix{ {{a^*}} \hfill & \!\!\!\! {:= \mathop {{\rm{argmax}}}\limits_{a\,\in\, \{ \alpha, \beta \} } \{ P(s,a,s')V(s')\} } \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\! { = \mathop {{\rm{argmax}}}\limits_{a\,\in\, \{ \alpha, \beta \} } \left\{ {\matrix{ {V({s_2})} \hfill & {{\rm{if }}\quad a = \alpha, } \hfill \cr {V({s_3})} \hfill & {{\rm{if }}\quad a = \beta, } \hfill \cr } } \right.} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ {{a^*}} \hfill & \!\!\!\! {:= \mathop {{\rm{argmax}}}\limits_{a\,\in\, \{ \alpha, \beta \} } \{ P(s,a,s')V(s')\} } \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\! { = \mathop {{\rm{argmax}}}\limits_{a\,\in\, \{ \alpha, \beta \} } \left\{ {\matrix{ {V({s_2})} \hfill & {{\rm{if }}\quad a = \alpha, } \hfill \cr {V({s_3})} \hfill & {{\rm{if }}\quad a = \beta, } \hfill \cr } } \right.} \hfill \cr } $$

where

![]() $V(s_2)$

and

$V(s_2)$

and

![]() $V(s_3)$

can be computed using the Bellman equation (7) as the following:

$V(s_3)$

can be computed using the Bellman equation (7) as the following:

yielding

![]() $V(s_2)=1$

and

$V(s_2)=1$

and

![]() $V(s_3)=c$

where

$V(s_3)=c$

where

![]() $c\in\mathbb{R}$

is an arbitrary constant. Suppose

$c\in\mathbb{R}$

is an arbitrary constant. Suppose

![]() $c=2$

is chosen as the solution, then the optimal action will be incorrectly identified as

$c=2$

is chosen as the solution, then the optimal action will be incorrectly identified as

![]() $\rm\beta$

by (8).

$\rm\beta$

by (8).

Overview of main results

Our work focuses on identifying the true value function among the multiple possible solutions of the Bellman equation. The Bellman equation provides a necessary condition for determining the value function. However, it can have several solutions, with only one being the true value function (for instance, the Bellman equation for reachability (Baier and Katoen, Reference Baier and Katoen2008, P851)).

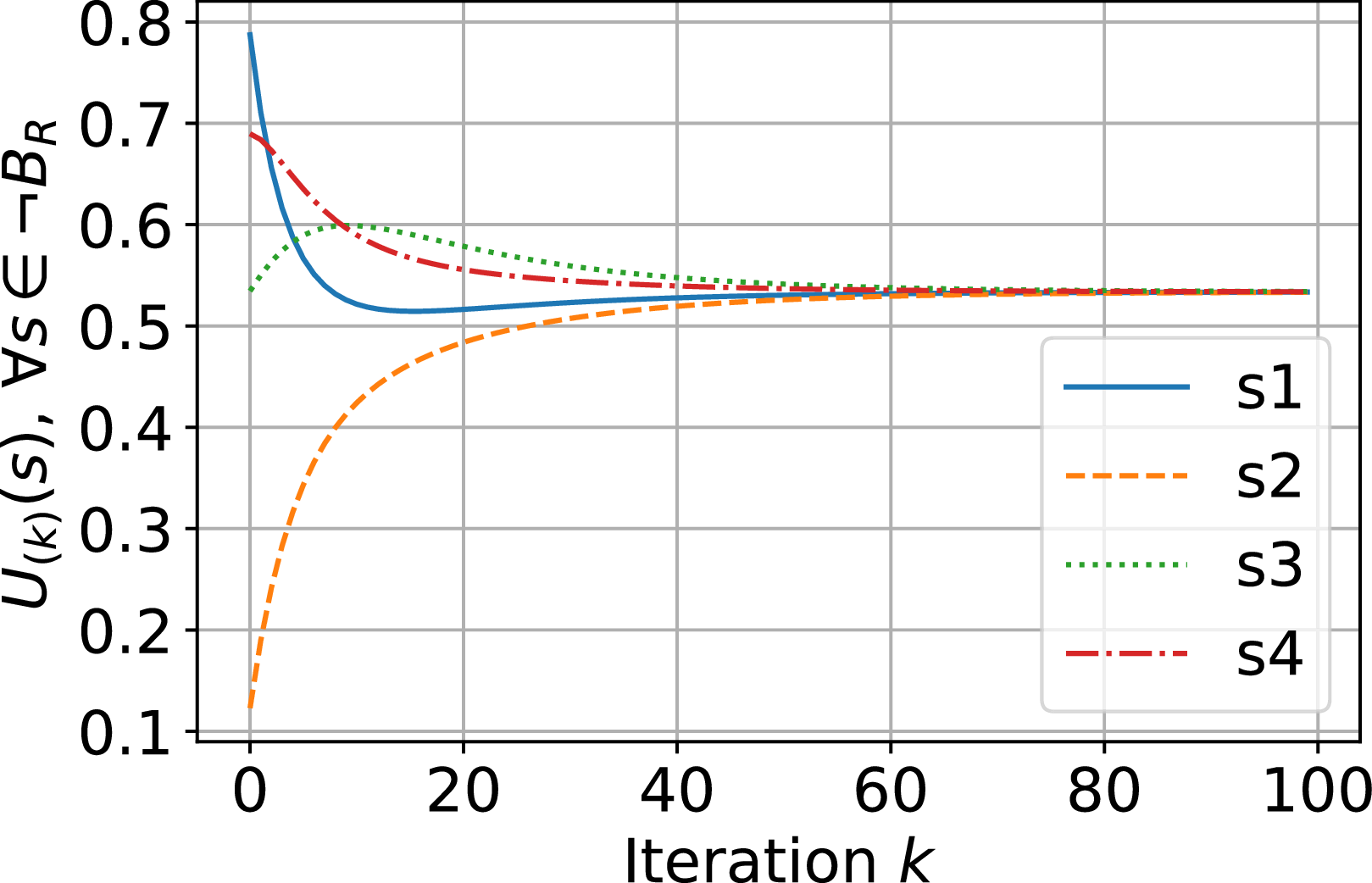

In Example 1, for

![]() $c=0$

, the solution for

$c=0$

, the solution for

![]() $V(s_3)$

is the value function equal to zero since no reward will be collected on this self-loop based on (3). Generally, the solution should be zero for all states in the rejecting BSCCs, as defined below.

$V(s_3)$

is the value function equal to zero since no reward will be collected on this self-loop based on (3). Generally, the solution should be zero for all states in the rejecting BSCCs, as defined below.

Definition 6. A bottom strongly connected component (BSCC) of an MC is a strongly connected component without outgoing transitions (Baier and Katoen, Reference Baier and Katoen2008, P774). The states in and out of the BSCCs are also called recurrent and transient states, respectively. Let B denotes the set of accepting states of the product MDP. A BSCC is rejecting

Footnote

2

if all states

![]() $s \,\notin\, B$

. Otherwise, we call it an accepting BSCC.

$s \,\notin\, B$

. Otherwise, we call it an accepting BSCC.

By Definition 6, a path that starts in a rejecting BSCC never reaches an accepting state. Thus, the value function for all states in the rejecting BSCCs equals 0 based on (3). Setting the values for all states within a rejecting BSCC to zero is a sufficient condition for the Bellman equation to yield a unique value function, as stated below. (This value function approximates the satisfaction probability defined in (2) and is equal to it when

![]() ${\rm\gamma}_B \to 1$

.)

${\rm\gamma}_B \to 1$

.)

Theorem 1. The Bellman equation (7) has the value function as the unique solution, if and only if i) the discount factor

![]() ${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

or ii) the discount factor

${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

or ii) the discount factor

![]() ${\rm\gamma} = 1$

and the solution for any state in a rejecting BSCC is zero.

${\rm\gamma} = 1$

and the solution for any state in a rejecting BSCC is zero.

Methodology

We illustrate the proof of Theorem 1 in this section. Specifically, we first prove it for the case of

![]() ${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

and then move to the case of

${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

and then move to the case of

![]() ${\rm\gamma}=1$

. The surrogate reward (3) depends on whether a state is an accepting state or not. Thus, we split the state space S by the accepting states B and rejecting states

${\rm\gamma}=1$

. The surrogate reward (3) depends on whether a state is an accepting state or not. Thus, we split the state space S by the accepting states B and rejecting states

![]() $\neg B:=S\backslash{B}$

. The Bellman equation can be rewritten in the following form,

$\neg B:=S\backslash{B}$

. The Bellman equation can be rewritten in the following form,

$$\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{V^B}} \cr {{V^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_m}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_n}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\!\! + \underbrace {\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{m \times m}}} & {} \cr {} & {{\rm\gamma} {I_{n \times n}}} \cr } } \right]}_{{\Gamma _B}}\underbrace {\left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, B \to B}}} & {{P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}} \cr } } \right]}_{{P_\pi }}\left[ {\matrix{ {{V^B}} \cr {{V^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right],} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{V^B}} \cr {{V^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_m}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_n}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\!\! + \underbrace {\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{m \times m}}} & {} \cr {} & {{\rm\gamma} {I_{n \times n}}} \cr } } \right]}_{{\Gamma _B}}\underbrace {\left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, B \to B}}} & {{P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}} \cr } } \right]}_{{P_\pi }}\left[ {\matrix{ {{V^B}} \cr {{V^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right],} \hfill \cr } $$

where

![]() $m=\vert B\vert$

,

$m=\vert B\vert$

,

![]() $n=\vert \neg B \vert$

,

$n=\vert \neg B \vert$

,

![]() $V^{B}\in\mathbb{R}^{m}$

,

$V^{B}\in\mathbb{R}^{m}$

,

![]() $V^{\neg B}\in\mathbb{R}^n$

are the vectors listing the value function for all

$V^{\neg B}\in\mathbb{R}^n$

are the vectors listing the value function for all

![]() $s\in {B}$

and

$s\in {B}$

and

![]() $s\in {\neg B}$

, respectively.

$s\in {\neg B}$

, respectively.

![]() $\mathbb{I}$

and

$\mathbb{I}$

and

![]() $\mathbb{O}$

are column vectors with all 1 and 0 elements, respectively. Each of the matrices

$\mathbb{O}$

are column vectors with all 1 and 0 elements, respectively. Each of the matrices

![]() $P_{\pi,B\rightarrow B}$

,

$P_{\pi,B\rightarrow B}$

,

![]() $ P_{\pi,B\rightarrow \neg B}$

,

$ P_{\pi,B\rightarrow \neg B}$

,

![]() $P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow B}$

,

$P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow B}$

,

![]() $P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow \neg B}$

contains the transition probability from a set of states to a set of states, their combination is the transition matrix

$P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow \neg B}$

contains the transition probability from a set of states to a set of states, their combination is the transition matrix

![]() $P_\pi$

for the induced MC. In the following, we assume a fixed policy

$P_\pi$

for the induced MC. In the following, we assume a fixed policy

![]() $\pi$

, leading us to omit the

$\pi$

, leading us to omit the

![]() $\pi$

subscript from most notation when its implication is clear from the context.

$\pi$

subscript from most notation when its implication is clear from the context.

The case

${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

Proposition 1. If

![]() ${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

in the surrogate reward (3), then the Bellman equation (10) has the value function as the unique solution.

${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

in the surrogate reward (3), then the Bellman equation (10) has the value function as the unique solution.

As

![]() ${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

, the invertibility of

${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

, the invertibility of

![]() $(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

can be shown by applying Gershgorin circle theorem (Bell, Reference Bell1965, Theorem 0) to

$(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

can be shown by applying Gershgorin circle theorem (Bell, Reference Bell1965, Theorem 0) to

![]() $\Gamma_B P_\pi$

. Specifically, any eigenvalue

$\Gamma_B P_\pi$

. Specifically, any eigenvalue

![]() $\lambda$

of

$\lambda$

of

![]() $\Gamma_B P_\pi$

satisfies

$\Gamma_B P_\pi$

satisfies

![]() $|\lambda | \lt 1$

since each row sum of

$|\lambda | \lt 1$

since each row sum of

![]() $\Gamma_B P_\pi$

is strictly less than 1. Then, the solution for the Bellman equation (10) can be uniquely determined as

$\Gamma_B P_\pi$

is strictly less than 1. Then, the solution for the Bellman equation (10) can be uniquely determined as

Proof. The solution of the Bellman equation (10) can be determined uniquely by matrix operation (11) if

![]() $(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

is invertible. The invertibility is shown using the Gershgorin circle theorem (Bell, Reference Bell1965, Theorem 0), which claims the following. For a square matrix A, define the radius as

$(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

is invertible. The invertibility is shown using the Gershgorin circle theorem (Bell, Reference Bell1965, Theorem 0), which claims the following. For a square matrix A, define the radius as

![]() $r_i:=\sum_{j\ne i}{\vert A_{ij}\vert}$

. Then, each eigenvalue of A is in at least one of the Gershgorin disks

$r_i:=\sum_{j\ne i}{\vert A_{ij}\vert}$

. Then, each eigenvalue of A is in at least one of the Gershgorin disks

![]() ${\mathcal D}(A_{ii},r_i):=\{z:\vert z-A_{ii}\vert\le r_i\}$

.

${\mathcal D}(A_{ii},r_i):=\{z:\vert z-A_{ii}\vert\le r_i\}$

.

For the matrix

![]() $\Gamma_B P_\pi$

, at its i-th row, we have the center of the disk as

$\Gamma_B P_\pi$

, at its i-th row, we have the center of the disk as

![]() $(\Gamma_B P_\pi)_{ii}=(\Gamma_B)_{ii}{(P_\pi)}_{ii}$

, and the radius as

$(\Gamma_B P_\pi)_{ii}=(\Gamma_B)_{ii}{(P_\pi)}_{ii}$

, and the radius as

![]() $r_i=\sum_{j\ne i}{\vert (\Gamma_B P_\pi)_{ij}\vert} ={(\Gamma_B)}_{ii}(1-{(P_\pi)}_{ii})$

. We can upper bound the disk as

$r_i=\sum_{j\ne i}{\vert (\Gamma_B P_\pi)_{ij}\vert} ={(\Gamma_B)}_{ii}(1-{(P_\pi)}_{ii})$

. We can upper bound the disk as

$$\matrix{ {{\cal D}({{({\Gamma _B}{P_\pi })}_{ii}},{r_i})} \hfill & {\!\!\!\! = \{ z:|z - {{({\Gamma _B}{P_\pi })}_{ii}}| \le {r_i}\} } \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\! \!\!{ \subseteq \{ z:|z| \le {{({\Gamma _B}{P_\pi })}_{ii}} + {r_i}\} } \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\! \!\!{ \subseteq \{ z:|z| \le {\rm\gamma} \} .} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ {{\cal D}({{({\Gamma _B}{P_\pi })}_{ii}},{r_i})} \hfill & {\!\!\!\! = \{ z:|z - {{({\Gamma _B}{P_\pi })}_{ii}}| \le {r_i}\} } \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\! \!\!{ \subseteq \{ z:|z| \le {{({\Gamma _B}{P_\pi })}_{ii}} + {r_i}\} } \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\! \!\!{ \subseteq \{ z:|z| \le {\rm\gamma} \} .} \hfill \cr } $$

Since all Gershgorin disks share the same upper bound, the union of all disks is also bounded by

The inequality

![]() ${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

ensures that any eigenvalue

${\rm\gamma} \lt 1$

ensures that any eigenvalue

![]() $\lambda$

of

$\lambda$

of

![]() $\Gamma_B P$

satisfies

$\Gamma_B P$

satisfies

![]() $|\lambda | \lt 1$

. Thus

$|\lambda | \lt 1$

. Thus

![]() $(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

is invertible and the solution can be uniquely determined by (11). The value function satisfies the Bellman equation (10), which has a unique solution, which is the value function. Thus, the proposition holds.

$(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

is invertible and the solution can be uniquely determined by (11). The value function satisfies the Bellman equation (10), which has a unique solution, which is the value function. Thus, the proposition holds.

![]() $\square$

$\square$

The case

${\rm\gamma}=1$

${\rm\gamma}=1$

For

![]() ${\rm\gamma}=1$

, the matrix

${\rm\gamma}=1$

, the matrix

![]() $(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

may not be invertible, causing the Bellman equation (10) to have multiple solutions. Since the solution may not be the value function here, we use

$(I-\Gamma_B P_\pi)$

may not be invertible, causing the Bellman equation (10) to have multiple solutions. Since the solution may not be the value function here, we use

![]() $U^{B}\in \mathbb{R}^m$

and

$U^{B}\in \mathbb{R}^m$

and

![]() $U^{\neg B}\in \mathbb{R}^n$

to represent a solution on states in B and

$U^{\neg B}\in \mathbb{R}^n$

to represent a solution on states in B and

![]() $\neg B$

, respectively. In an induced MC, a path starts in an initial state, travels finite steps among the transient states, and eventually enters a BSCC. If the induced MC has only accepting BSCCs, the connection between all states in B can be captured by a new transition matrix, and the Bellman operator is contractive on the states in B. Thus, we can show the solution is unique in all the states in the following subsection. In the general case where rejecting BSCCs also exists, we introduce a sufficient condition of fixing all solutions within rejecting BSCCs to zero. We demonstrate the uniqueness of the solution under this condition first on

$\neg B$

, respectively. In an induced MC, a path starts in an initial state, travels finite steps among the transient states, and eventually enters a BSCC. If the induced MC has only accepting BSCCs, the connection between all states in B can be captured by a new transition matrix, and the Bellman operator is contractive on the states in B. Thus, we can show the solution is unique in all the states in the following subsection. In the general case where rejecting BSCCs also exists, we introduce a sufficient condition of fixing all solutions within rejecting BSCCs to zero. We demonstrate the uniqueness of the solution under this condition first on

![]() $U^{B}$

and then on

$U^{B}$

and then on

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

in the second part of this section.

$U^{\neg B}$

in the second part of this section.

When the MC only has accepting BSCCs

This section focuses on proving that the Bellman equation (10) has a unique solution when there are no rejecting BSCCs in the MC. The result is as follows,

Proposition 2. If the MC only has accepting BSCCs (i.e., no rejecting BSCCs) and

![]() ${\rm\gamma}=1$

in the surrogate reward (3), then the Bellman equation (10) has a unique solution

${\rm\gamma}=1$

in the surrogate reward (3), then the Bellman equation (10) has a unique solution

![]() $[{U^B}^T, {U^{\neg B}}^T]^T= \mathbb{I}$

.

$[{U^B}^T, {U^{\neg B}}^T]^T= \mathbb{I}$

.

The intuition behind the proof is to capture the connection between all states B by a new transition matrix

![]() $P_\pi^B$

in Lemma 3. Then, one can use

$P_\pi^B$

in Lemma 3. Then, one can use

![]() $I-{\rm\gamma}_B P_\pi^B$

is invertible to show the solutions

$I-{\rm\gamma}_B P_\pi^B$

is invertible to show the solutions

![]() $U_B$

is unique and furthermore, show

$U_B$

is unique and furthermore, show

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

is uniquely determined by

$U^{\neg B}$

is uniquely determined by

![]() $U^{B}$

in Lemma 4.

$U^{B}$

in Lemma 4.

Lemma 3. If the MC

![]() ${\mathcal{M}}_\pi=(S, P_\pi, s_{\rm 0},\Lambda, L)$

only has accepting BSCCs, one can represent the transitions between accepting states as an MC with only accepting states

${\mathcal{M}}_\pi=(S, P_\pi, s_{\rm 0},\Lambda, L)$

only has accepting BSCCs, one can represent the transitions between accepting states as an MC with only accepting states

![]() ${\mathcal M}_\pi^B:=(B, P_\pi^B,\mu,\Lambda, L)$

where

${\mathcal M}_\pi^B:=(B, P_\pi^B,\mu,\Lambda, L)$

where

-

B is the set of accepting states,

-

$P_\pi^B$

is the transition probability matrix defined by(14)

$P_\pi^B$

is the transition probability matrix defined by(14) $$P_\pi ^B: = {P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{(I - {P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}})^{ - 1}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}.$$

$$P_\pi ^B: = {P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{(I - {P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}})^{ - 1}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}.$$

-

$\mu\,\in\, \Delta(B)$

is the initial distribution and determined by

$\mu\,\in\, \Delta(B)$

is the initial distribution and determined by

$s_0$

as(15)where

$s_0$

as(15)where $$\eqalign{ & {\rm{if}}\;{\mkern 1mu} {s_0}\,\in\, B,\quad \mu (s) = \left\{ {\matrix{ 1 \hfill & {s = {s_0}} \hfill \cr 0 \hfill & {s \ne {s_0}} \hfill \cr } } \right., \cr & {\rm{if}}\;{\mkern 1mu} {s_0} \;\notin\; B,\quad \mu (s) = {({P_{init}})_{{s_0}s}} \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{ & {\rm{if}}\;{\mkern 1mu} {s_0}\,\in\, B,\quad \mu (s) = \left\{ {\matrix{ 1 \hfill & {s = {s_0}} \hfill \cr 0 \hfill & {s \ne {s_0}} \hfill \cr } } \right., \cr & {\rm{if}}\;{\mkern 1mu} {s_0} \;\notin\; B,\quad \mu (s) = {({P_{init}})_{{s_0}s}} \cr} $$

$P_{init} := (I-P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B})^{-1}P_{\pi,\neg B\to B}$

is a matrix. Each element

$P_{init} := (I-P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B})^{-1}P_{\pi,\neg B\to B}$

is a matrix. Each element

$(P_{init})_{ij}$

represents the probability of a path leaving the state

$(P_{init})_{ij}$

represents the probability of a path leaving the state

$i\in {\neg B}$

and visiting state

$i\in {\neg B}$

and visiting state

$j\in B$

without visiting any state in B between the leave and visit.

$j\in B$

without visiting any state in B between the leave and visit.

Proof. We start with constructing a transition matrix

![]() $P_\pi^B$

for the states in B whose (i, j)th element, denoted by

$P_\pi^B$

for the states in B whose (i, j)th element, denoted by

![]() $(P_\pi^B)_{ij}$

, is the probability of visiting jth state in B without visiting any state in B after leaving the ith state in B.

$(P_\pi^B)_{ij}$

, is the probability of visiting jth state in B without visiting any state in B after leaving the ith state in B.

In (16), the matrix element

![]() $(P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}^k)_{ij}$

represents the probability of a path leaving the state i and visiting state j after k steps without travelling through any states in B. However, the absence of rejecting BSCCs ensures that any path will visit a state in B in finite times with probability 1. Thus, for any

$(P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}^k)_{ij}$

represents the probability of a path leaving the state i and visiting state j after k steps without travelling through any states in B. However, the absence of rejecting BSCCs ensures that any path will visit a state in B in finite times with probability 1. Thus, for any

![]() $i, j\,\in\, \neg B$

,

$i, j\,\in\, \neg B$

,

![]() $\lim_{k\to \infty}(P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}^k)_{ij}=0$

. This limit implies any eigenvalue

$\lim_{k\to \infty}(P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}^k)_{ij}=0$

. This limit implies any eigenvalue

![]() $\lambda$

of

$\lambda$

of

![]() $P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}$

satisfies

$P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}$

satisfies

![]() $|\lambda | \lt 1$

and therefore

$|\lambda | \lt 1$

and therefore

![]() $\sum\nolimits_{k = 0}^\infty {P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^k} $

can be replaced by

$\sum\nolimits_{k = 0}^\infty {P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^k} $

can be replaced by

![]() $(I - P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow \neg B})^{-1}$

in (16),

$(I - P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow \neg B})^{-1}$

in (16),

Since all the elements on the right-hand side are greater or equal to zero, for any

![]() $i, j\,\in\, B$

,

$i, j\,\in\, B$

,

![]() $(P_\pi^B)_{ij}\ge 0$

. Since there are only accepting BSCCs in the MC, given a path starting from an arbitrary state in B, the path will visit an accepting state in finite steps with probability one, ensuring that for all

$(P_\pi^B)_{ij}\ge 0$

. Since there are only accepting BSCCs in the MC, given a path starting from an arbitrary state in B, the path will visit an accepting state in finite steps with probability one, ensuring that for all

![]() $i\in B$

,

$i\in B$

,

![]() $\sum_{j\in S} (P_\pi^B)_{ij}=1$

. Thus,

$\sum_{j\in S} (P_\pi^B)_{ij}=1$

. Thus,

![]() $P_\pi^B$

is a probability matrix that can be used to describe the behaviour of an MC with the state space as B only.

$P_\pi^B$

is a probability matrix that can be used to describe the behaviour of an MC with the state space as B only.

Lemma 4. Suppose there is no rejecting BSCC, for

![]() ${\rm\gamma} =1$

in (3), the Bellman equation (10) is equivalent to the following form,

${\rm\gamma} =1$

in (3), the Bellman equation (10) is equivalent to the following form,

$$\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^B}} \cr {{U^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_m}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_n}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\!\! + \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{m \times m}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{n \times n}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {P_\pi ^B} & {} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^B}} \cr {{U^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right].} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^B}} \cr {{U^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_m}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_n}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\!\! + \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{m \times m}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{n \times n}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {P_\pi ^B} & {} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^B}} \cr {{U^{\neg B}}} \cr } } \right].} \hfill \cr } $$

The equation (18) implies that the solution

![]() $U^{B}$

does not rely on the rejecting states

$U^{B}$

does not rely on the rejecting states

![]() $\neg B$

. Subsequently, we leverage the fact that

$\neg B$

. Subsequently, we leverage the fact that

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

is uniquely determined by

$U^{\neg B}$

is uniquely determined by

![]() $U^{B}$

to establish the uniqueness of the overall solution V.

$U^{B}$

to establish the uniqueness of the overall solution V.

Proof. We prove this lemma by showing the equivalence between

![]() $P_\pi^B U^{B}$

and

$P_\pi^B U^{B}$

and

![]() $P_{\pi,B\to B}U^{B} + P_{\pi,B\to\neg B}U^{\neg B}$

. From the Bellman equation (10), we have

$P_{\pi,B\to B}U^{B} + P_{\pi,B\to\neg B}U^{\neg B}$

. From the Bellman equation (10), we have

![]() $U^{\neg B}=P_{\pi,\neg B\to B} U^{B} + P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}U^{\neg B}$

$U^{\neg B}=P_{\pi,\neg B\to B} U^{B} + P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}U^{\neg B}$

$$\eqalign{ & {P_{\pi, B \to B}}{U^B} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{U^{\neg B}} \cr & \mathop = \limits^{\unicode{x24B6}} \left( {{P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}{U^{\neg B}} \cr & \mathop = \limits^{\unicode{x24B7}} \left( {{P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + \left( {{P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^2{U^{\neg B}} \cr & \vdots \cr & \mathop = \limits^{ \unicode{x24B8}} \mathop {{\rm{lim}}}\limits_{ K \to \infty } \Bigg(\left( {{P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}\mathop \sum \limits_{k = 0}^K P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^{k}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^{K + 1}{U^{\neg B}}\Bigg) \cr & \mathop = \limits^\unicode{x24B9} P_\pi ^B{U^B} \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{ & {P_{\pi, B \to B}}{U^B} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{U^{\neg B}} \cr & \mathop = \limits^{\unicode{x24B6}} \left( {{P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}{U^{\neg B}} \cr & \mathop = \limits^{\unicode{x24B7}} \left( {{P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + \left( {{P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^2{U^{\neg B}} \cr & \vdots \cr & \mathop = \limits^{ \unicode{x24B8}} \mathop {{\rm{lim}}}\limits_{ K \to \infty } \Bigg(\left( {{P_{\pi, B \to B}} + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}\mathop \sum \limits_{k = 0}^K P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^{k}{P_{\pi, \neg B \to B}}} \right){U^B} \cr & + {P_{\pi, B \to \neg B}}P_{\pi, \neg B \to \neg B}^{K + 1}{U^{\neg B}}\Bigg) \cr & \mathop = \limits^\unicode{x24B9} P_\pi ^B{U^B} \cr} $$

where the equality Ⓐ holds as we replace

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

in the last term

$U^{\neg B}$

in the last term

![]() $P_{\pi,B\to\neg B}U^{\neg B}$

by

$P_{\pi,B\to\neg B}U^{\neg B}$

by

![]() $P_{\pi,\neg B\to B} U^{B} + P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}U^{\neg B}$

. Similarily, the equalities Ⓑ and Ⓒ hold as we keep replacing

$P_{\pi,\neg B\to B} U^{B} + P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}U^{\neg B}$

. Similarily, the equalities Ⓑ and Ⓒ hold as we keep replacing

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

in the last term by

$U^{\neg B}$

in the last term by

![]() $P_{\pi,\neg B\to B} U^{B} + P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}U^{\neg B}$

. The equality Ⓓ holds by the definition of

$P_{\pi,\neg B\to B} U^{B} + P_{\pi,\neg B\to \neg B}U^{\neg B}$

. The equality Ⓓ holds by the definition of

![]() $P_\pi^B$

.

$P_\pi^B$

.

![]() $\square$

$\square$

Lemma 4 shows the uniqueness of the solution. Directly solving equation (18) completes the proof for Proposition 2.

Proof for Proposition 2. From equation (18), we obtain the expression for the MC with only accepting states,

Given that all the eigenvalues of

![]() $P_\pi^B$

are within the unit disk and

$P_\pi^B$

are within the unit disk and

![]() ${{\rm\gamma} _B} \lt 1$

, the matrix

${{\rm\gamma} _B} \lt 1$

, the matrix

![]() $(I-{\rm\gamma}_B P_\pi^B)$

is invertible.

$(I-{\rm\gamma}_B P_\pi^B)$

is invertible.

![]() $U^{B}$

is uniquely determined by

$U^{B}$

is uniquely determined by

Moving to the set of rejecting states

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

, from equation (18) we have,

$U^{\neg B}$

, from equation (18) we have,

Given the uniqueness of

![]() $U^{B}$

, and the invertibility of

$U^{B}$

, and the invertibility of

![]() $(I-P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow \neg B})$

, we conclude that

$(I-P_{\pi,\neg B\rightarrow \neg B})$

, we conclude that

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

is also unique.

$U^{\neg B}$

is also unique.

Let

![]() $U^{B}=\mathbb{I}_m$

and

$U^{B}=\mathbb{I}_m$

and

![]() $U^{\neg B}=\mathbb{I}_n$

, the Bellman equation (10) holds as the summation of each row of a probability matrix

$U^{\neg B}=\mathbb{I}_n$

, the Bellman equation (10) holds as the summation of each row of a probability matrix

![]() $P_B$

is always one,

$P_B$

is always one,

Therefore, in the absence of rejecting BSCCs, the unique solution to the Bellman equation (10) is

![]() $\mathbb{I}$

.

$\mathbb{I}$

.

![]() $\square$

$\square$

Proposition 2 shows the solutions for the states inside an accepting BSCC have to be 1. All states outside the BSCC cannot be reached from a state inside the BSCC, thus the solution for states outside this BSCC is not involved in the solution for states inside the BSCC. By Lemma 4, the Bellman equation for an accepting BSCC can be rewritten into the form of (18) where

![]() $U_B$

and

$U_B$

and

![]() $U_{\neg B}$

stands for the solution for accepting states and rejecting states inside this BSCC, and vector

$U_{\neg B}$

stands for the solution for accepting states and rejecting states inside this BSCC, and vector

![]() $\mathbb{I}$

is the unique solution.

$\mathbb{I}$

is the unique solution.

When accepting and rejecting BSCC both exist in the MC

Having established the uniqueness of solutions in the case of accepting BSCCs, we now shift our focus to the general case involving rejecting BSCCs. We state in Proposition 2 that the solutions for the states in the accepting BSCCs are unique and equal to

![]() $\mathbb{I}$

. We now demonstrate that setting the solutions for the states in rejecting BSCCs to

$\mathbb{I}$

. We now demonstrate that setting the solutions for the states in rejecting BSCCs to

![]() $\mathbb{O}$

ensures the uniqueness and correctness of the solutions for all states. We partition the state space further into

$\mathbb{O}$

ensures the uniqueness and correctness of the solutions for all states. We partition the state space further into

![]() $\{B_A, B_T, \neg B_A, \neg B_R, \neg B_T\}$

. Here the subscripts A and R denote accepting and rejecting (unrelated to the action set A or reward function R). Specifically,

$\{B_A, B_T, \neg B_A, \neg B_R, \neg B_T\}$

. Here the subscripts A and R denote accepting and rejecting (unrelated to the action set A or reward function R). Specifically,

-

$B_A$

is the set of accepting states in the BSCCs,

$B_A$

is the set of accepting states in the BSCCs, -

$B_T:=B\backslash B_A$

is the set of transient accepting states,

$B_T:=B\backslash B_A$

is the set of transient accepting states, -

$\neg B_A$

is the set of rejecting states in the accepting BSCCs,

$\neg B_A$

is the set of rejecting states in the accepting BSCCs, -

$\neg B_R$

is the set of rejecting states in the rejecting BSCCs,

$\neg B_R$

is the set of rejecting states in the rejecting BSCCs, -

$\neg B_T:=\neg B\backslash (\neg B_A \cup \neg B_R)$

is set of transient rejecting states.

$\neg B_T:=\neg B\backslash (\neg B_A \cup \neg B_R)$

is set of transient rejecting states.

We rewrite the Bellman equation (10) in the form of (24).

$${\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{{B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_R}}}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_m}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_n}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!\!\!{ + \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{m \times m}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{n \times n}}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!\!\!\!\times{\left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {} & {{P_{\pi, {B_A} \to {B_A}}}} & {} & {{P_{\pi, {B_A} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_A} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_A} \to {B_A}}}} & {} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_A} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_A} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {} & {} & {} & {} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_R} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!\!\times{\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{{B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_R}}}} \cr } } \right].} \hfill \cr }} $$

$${\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{{B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_R}}}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_m}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_n}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!\!\!{ + \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{m \times m}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{n \times n}}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!\!\!\!\times{\left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {} & {{P_{\pi, {B_A} \to {B_A}}}} & {} & {{P_{\pi, {B_A} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_A} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_A} \to {B_A}}}} & {} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_A} \to \neg {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_A} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr {} & {} & {} & {} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_R} \to \neg {B_R}}}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & \!\!\!\!\!\times{\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{{B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_A}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_R}}}} \cr } } \right].} \hfill \cr }} $$

The solution for states inside BSCCs has been fixed as

![]() $[{U^{B_A}}^T, {U^{\neg B_A}}^T]^T=\mathbb{I}$

and

$[{U^{B_A}}^T, {U^{\neg B_A}}^T]^T=\mathbb{I}$

and

![]() $U^{\neg B_R}=\mathbb{O}$

. The solution

$U^{\neg B_R}=\mathbb{O}$

. The solution

![]() $U^{B_T}$

and

$U^{B_T}$

and

![]() $U^{\neg B_T}$

for transient states remain to be shown as unique. We rewrite the Bellman equation (24) into the following form (25) where

$U^{\neg B_T}$

for transient states remain to be shown as unique. We rewrite the Bellman equation (24) into the following form (25) where

![]() $U^{B_T}$

and

$U^{B_T}$

and

![]() $U^{\neg B_T}$

are the only variables,

$U^{\neg B_T}$

are the only variables,

$$\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr } } \right] = \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{{m_1} \times {m_1}}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{{n_1} \times {n_1}}}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr } } \right] + \left[ {\matrix{ {{B_1}} \cr {{B_2}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr } } \right] = \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{{m_1} \times {m_1}}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{{n_1} \times {n_1}}}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_T}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {{U^{{B_T}}}} \cr {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \cr } } \right] + \left[ {\matrix{ {{B_1}} \cr {{B_2}} \cr } } \right]} \hfill \cr } $$

here

![]() $m_1=\vert U^{B_T}\vert$

,

$m_1=\vert U^{B_T}\vert$

,

![]() $m_2=\vert U^{B_A}\vert$

,

$m_2=\vert U^{B_A}\vert$

,

![]() $n_1=\vert U^{\neg B_T}\vert$

,

$n_1=\vert U^{\neg B_T}\vert$

,

![]() $n_2=\vert U^{\neg B_A}\vert$

, and

$n_2=\vert U^{\neg B_A}\vert$

, and

$$\eqalign{ & \left[ {\matrix{ {{B_1}} \cr {{B_2}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_{{m_1}}}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_{{n_1}}}} \cr } } \right] + \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{{m_1} \times {m_1}}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{{n_1} \times {n_1}}}} \cr } } \right] \cr & \left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_{{m_2}}}} \cr {{{\mathbb I}_{{n_2}}}} \cr } } \right]. \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{ & \left[ {\matrix{ {{B_1}} \cr {{B_2}} \cr } } \right] = (1 - {{\rm\gamma} _B})\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_{{m_1}}}} \cr {{{\mathbb O}_{{n_1}}}} \cr } } \right] + \left[ {\matrix{ {{{\rm\gamma} _B}{I_{{m_1} \times {m_1}}}} & {} \cr {} & {{I_{{n_1} \times {n_1}}}} \cr } } \right] \cr & \left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} \cr {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} \cr } } \right]\left[ {\matrix{ {{{\mathbb I}_{{m_2}}}} \cr {{{\mathbb I}_{{n_2}}}} \cr } } \right]. \cr} $$

Lemma 5. The equation (25) has a unique solution.

We demonstrate

![]() $U^{B_T}$

does not rely on states in

$U^{B_T}$

does not rely on states in

![]() $\neg B_T$

and

$\neg B_T$

and

![]() $U^{\neg B_T}$

is uniquely determined by

$U^{\neg B_T}$

is uniquely determined by

![]() $U^{B_T}$

. Then the uniqueness of

$U^{B_T}$

. Then the uniqueness of

![]() $U^{B_T}$

can be shown first, consequently, uniqueness of

$U^{B_T}$

can be shown first, consequently, uniqueness of

![]() $U^{\neg B_T}$

can be shown.

$U^{\neg B_T}$

can be shown.

Proof. First we show

![]() $U^{B_T}$

is unique since its calculation can exclude

$U^{B_T}$

is unique since its calculation can exclude

![]() $U^{\neg B}$

. By equation (25),

$U^{\neg B}$

. By equation (25),

$$\matrix{ {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \hfill & {\!\! \!\!= {P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_T}}}{U^{{B_T}}} + {P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \hfill \cr\cr {} \hfill & {\!\!\!\! + \left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} \cr } } \right]{\mathbb I}} \hfill \cr } $$

$$\matrix{ {{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \hfill & {\!\! \!\!= {P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_T}}}{U^{{B_T}}} + {P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_T}}}{U^{\neg {B_T}}}} \hfill \cr\cr {} \hfill & {\!\!\!\! + \left[ {\matrix{ {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to {B_A}}}} & {{P_{\pi, \neg {B_T} \to \neg {B_A}}}} \cr } } \right]{\mathbb I}} \hfill \cr } $$

The following equalities hold as we keep expanding

![]() $U^{\neg B_T}$

,

$U^{\neg B_T}$

,