No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

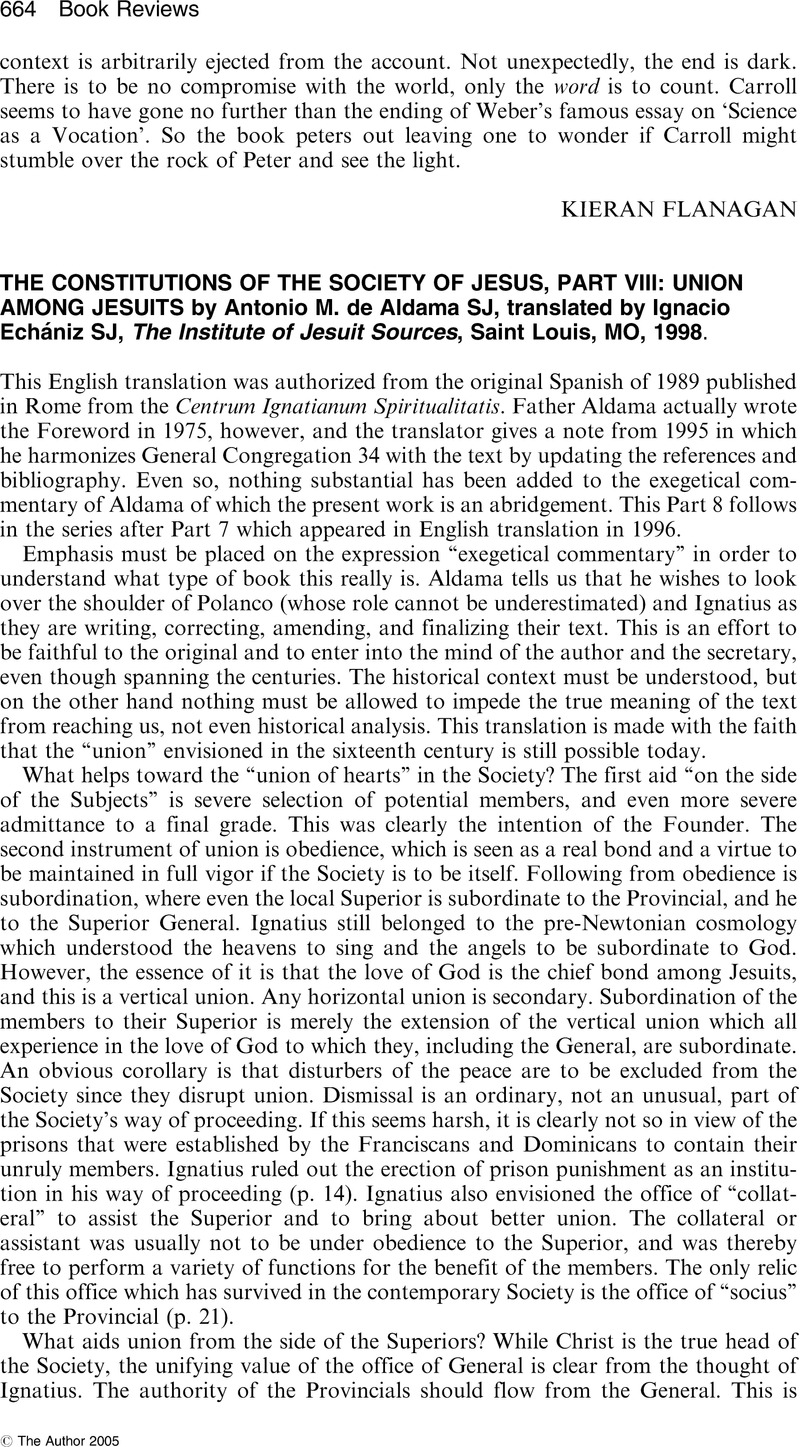

The Constitutions of the Society of Jesus, Part VIII: Union Among Jesuits by Antonio M. de Aldama SJ, translated by Ignacio Echániz SJ, The Institute of Jesuit Sources, Saint Louis, MO, 1998.

Review products

The Constitutions of the Society of Jesus, Part VIII: Union Among Jesuits by Antonio M. de AldamaSJ, translated by Ignacio EchánizSJ, The Institute of Jesuit Sources, Saint Louis, MO, 1998.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2024

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

Information

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author 2005