Introduction

As political support erodes across democracies (Dalton Reference Dalton2004; OECD 2024), democratic innovations (DIs) have emerged as a response to rebuild public confidence in political institutions. Defined as ‘processes or institutions that are new to a policy issue, policy role, or level of governance, and developed to reimagine and deepen the role of citizens in governance processes by increasing opportunities for participation, deliberation, and influence’ (Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub and Escobar2019: 28), DIs aim to empower citizens in policy making through various participatory instruments such as deliberative mini-publics (citizens’ assemblies, forums, or juries), referenda, or participatory budgeting. Normative expectations suggest that these mechanisms could help address the crises and deficiencies of liberal democracy by narrowing the gap between citizens and representative institutions.

By strengthening citizen involvement beyond elections, DIs are expected to enhance both public confidence in decision-making and the legitimacy of policies. This has sparked growing research on public attitudes towards these innovations. While the public generally supports greater participation in policy making, this support is not evenly distributed (Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015). Those who feel politically marginalized – such as socio-economically disadvantaged and politically disaffected citizens – tend to be more favourable towards DIs, viewing them as a means to amplify their voices. Support also comes from politically engaged individuals who see participation as an opportunity rather than a necessity (Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2024b, Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Talukder and Pilet Reference Talukder and Pilet2021; Walsh and Elkink Reference Walsh and Elkink2021).

While prior studies focus on individual-level factors, this study advances the literature by integrating regional economic conditions into the analysis of public support for DIs. Regions vary widely in economic productivity, infrastructure, public services, and labour markets – factors that shape citizens’ democratic demands and may amplify or mitigate socio-economic and political disparities. Indeed, socio-economic disadvantages and political disaffection are rooted in the places where citizens live, reflecting broader structural inequalities that emerge where governing institutions struggle to address economic and political challenges. Political discontent, for instance, is more pronounced in peripheral and economically declining regions (de Lange et al. Reference de Lange, van der Brug and Harteveld2022; Munis Reference Munis2022; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018). However, comparative public opinion research on DIs has yet to systematically account for how structural inequalities influence public support. At the same time, regional studies have long analysed the implications of regional-level socio-economic disparities on voting behaviour but have not yet considered how it might relate to citizens’ willingness to change the democratic status quo and preferences for certain democratic reforms. By bridging these research streams, this study offers a novel perspective: citizens’ democratic demands are not only shaped by their individual attitudes but also by the structural environment in which they live. Specifically, we ask how regional economic conditions affect public support for DIs, but also whether these conditions affect the relationship with individual-level socio-economic (economic deprivation) and political (political disaffection and political engagement) predictors.

To address these questions, we take a regional science approach and adopt a multilevel analytical framework. Our dataset – one of the first of its kind – combines individual-level survey data from over 16,000 citizens (N = 16,109) with regional-level (NUTSFootnote 1 1 and 2) economic indicators, covering ninety-one regions across thirteen European countries over a period of up to ten years before the survey. This subnational granularity allows for a genuine multilevel analysis of public support for DIs, moving beyond the country-level focus of most existing studies (for example, Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023, Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2024b; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015). By providing a more detailed spatial perspective, this study not only improves our understanding of regional variations in DI support but also lays the groundwork for future research on the intersection of economic decline and democratic aspirations.

Our findings reveal that citizens in poorer regions are slightly more supportive of DIs. Moreover, economically deprived and politically disaffected citizens are more strongly affected by low economic performance: the poorer the region, the greater the effect of individual-level deprivation and disaffection. Meanwhile, political engagement has a more uniform effect across regions, with politically engaged citizens supporting DIs regardless of economic context. However, in poorer regions, even politically disengaged citizens show increased support for participatory mechanisms. These results suggest that public support for DIs is partially rooted in structural economic conditions. When traditional governance structures fail to deliver economic outcomes, demand for democratic alternatives intensifies – especially among underprivileged groups (economically deprived, politically disaffected, and politically disengaged). In other words, citizens in left-behind regions do not just seek ‘revenge by the ballot box’ (Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018); they also show a willingness to engage in policy making through participatory mechanisms. This study contributes to broader debates on structural inequalities and democratic legitimacy by demonstrating that public support for DIs is partly context-dependent. For policy makers and practitioners, this underscores the need for tailored approaches: in economically disadvantaged regions, DIs may serve as compensatory mechanisms to restore trust and inclusion, but their success depends on addressing underlying economic grievances. In wealthier regions, the challenge lies in fostering meaningful engagement among politically interested citizens while avoiding the alienation of disengaged groups. By integrating regional economic conditions into the study of democratic reforms, this research offers a more nuanced understanding of when and why citizens demand institutional change, paving the way for more context-sensitive participatory policies.

Theoretical Framework

Public Opinion Research and DIs: Individual-Level Drivers

Like in political theory, there has been a huge ‘participatory turn’ in democratic practices over the past few decades. In Europe, all levels of governance have increasingly experimented with DIs (Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub and Escobar2019), like referenda (Hollander Reference Hollander2019) and deliberative mini-publics (Curato et al. Reference Curato, Farrell, Geissel, Grönlund, Mockler, Pilet, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021; Paulis et al. Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2020). DIs are often presented as participatory instruments likely to increase the legitimacy of the decision-making processes by involving citizens more directly, outside elections. However, they may also challenge and reshape the representation relationships between citizens and elected politicians. Scholars have therefore focused on why DIs are perceived as legitimate policy-making instruments and who supports them in the population.

This literature on public support for DIs can be subdivided into three main elements: procedural fairness, outcome favourability, and citizens’ characteristics (both in terms of social attributes and political attitudes). The first research strand shows that citizens support DIs when they perceive these instruments as promoting procedural fairness and inclusiveness (Christensen Reference Christensen2020; Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2012; Paulis et al. Reference Pilet, Vittori, Paulis and Rojon2024; Pow et al. Reference Pow, van Dijk and Marien2020; van der Eijk and Rose Reference Van der Eijk and Rose2021), especially when elections and representative democracy (the ‘status quo’) are used as benchmarks (Werner and Marien Reference Werner and Marien2022). Another line of research demonstrates that there is an instrumental link between the issue at stake and the outcomes of DIs. Citizens adopt more positive attitudes when they anticipate or realise that using DIs will lead to favourable results aligned with their opinions and policy preferences (Arnesen Reference Arnesen2017; Brummel Reference Brummel2020; Werner Reference Werner2020; Werner and Marien Reference Werner and Marien2022). To capture these findings and ensure causality, scholars have typically embedded experiments in surveys conducted in one or a small number of countries.

The third and final line of research focuses on citizens’ social characteristics and political attributes. While most empirical evidence suggests that most of the population is favourable to DIs and increased citizen involvement, these opinions are not evenly distributed across the various social and political groups in society. On the one hand, some studies show that socio-demographic profiles matter. DIs are positively evaluated by citizens from disadvantaged social groups, which are generally less descriptively represented in elected institutions. As DIs promote inclusiveness and fairness, these groups view them as good opportunities for their voices to be heard and represented in policy making. For example, women and younger citizens show higher levels of support for deliberative mini-publics (Talukder and Pilet Reference Talukder and Pilet2021; Walsh and Elkink Reference Walsh and Elkink2021) or referenda (Rojon and Rijken Reference Rojon and Rijken2021; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015) compared to the rest of the population. Moreover, beyond these objective characteristics, studies highlight the importance of the subjective assessment of citizens’ economic well-being and their feelings of economic deprivation. For instance, Walsh and Elkink (Reference Walsh and Elkink2021) found that the perception of thinking one is worse off now compared to last year is positively correlated with support for deliberative assemblies. Similarly, Pilet et al. (Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2024b, Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023) revealed that the more insecure people feel about their household’s income, the more positively they view citizens’ assemblies. This self-oriented (pocketbook) perspective is also relevant when it comes to participating in referenda (Meya et al. Reference Meya, Poutvaara and Schwager2017) or supporting their organization (Rojon and Rijken Reference Rojon and Rijken2021).

Along with social attributes, political attitudes also play an important role in shaping support for DIs at the individual level. The ‘political disaffection’ hypothesis suggests that DIs such as referenda and deliberative mini-publics are particularly supported by citizens who feel ‘enraged’ and are critical of traditional party politics. For these citizens, DIs represent alternative ways of expressing themselves politically, processes that they trust more than traditional ones, in which they have lost confidence. Empirical evidence supporting this view has grown over the last decade. Many studies have shown that people tend to support DIs more when they distrust politicians and traditional political institutions or are dissatisfied with the democratic performance of their country or government (Bedock and Pilet Reference Bedock and Pilet2020a; Bengtsson and Mattila Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Goldberg and Bächtiger Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2023; Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2024b, Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Rojon and Rijken Reference Rojon and Rijken2021; Schuck and de Vreese Reference Schuck and de Vreese2015; Walsh and Elkink Reference Walsh and Elkink2021). Therefore, based on these earlier contributions, we formulate a baseline expectation that aligns with previous individual-level findings and the ‘enraged’ theory of support:

Hypothesis 1: Support for DIs will be higher among (a) economically deprived or (b) politically disaffected citizens.

At the same time, existing research has also supported the ‘political engagement’ hypothesis, which argues that democratic reforms advocating for more referenda (Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007) or deliberative mini-publics (Bedock and Pilet Reference Bedock and Pilet2020a; Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Walsh and Elkink Reference Walsh and Elkink2021) may appeal to politically engaged citizens – those who are interested in politics or feel efficacious and capable of handling complex political tasks. This access to greater political resources could make them more positive about these participatory policy-making instruments because they feel both interested and skilled enough to influence politics beyond the mere act of voting in elections. From this, we establish a second, baseline expectation and the ‘engaged’ theory of support:

Hypothesis 2: Support for DIs will be higher among politically engaged citizens.

Structural Economic Inequalities and DIs: Regional-Level Factors and Their Moderating Role

Previous studies have examined most of the factors associated with public support for DIs at the individual level. To the best of our knowledge, no study has focused on structural-level factors or the cross-level interactions. There are yet strong reasons to explore these aspects. DIs’ evaluations are not homogeneous: they vary both across and within countries, as do perceptions of economic well-being or evaluations of political institutions. Indeed, we know from regional studies that economic deprivation and political disaffection are strongly spatially concentrated, particularly in regions with significant structural economic inequalities (De Dominicis et al. Reference De Dominicis, Dijkstra and Pontarollo2022; Munis Reference Munis2022; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer2020).

Recent regional studies have traced the roots of discontent to continued episodes of economic and demographic stagnation in regions that have struggled to adapt to growing challenges brought by globalization, trade integration, and, more recently, the green and digital transitions (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2016; Rodríguez-Pose and Bartalucci Reference Rodríguez-Pose, Dijkstra and Poelman2024; Rodríguez-Pose et al. Reference Rodríguez-Pose, Dijkstra and Poelman2024). Studies have shown how structural socio-economic and demographic changes have contributed to increasing geographical disparities within countries, with some regions attracting economic development, skilled workers, and capital, while others are left behind, facing economic and demographic decline (Blažek et al. Reference Blažek, Květoň, Baumgartinger-Seiringer and Trippl2020; Johnson and Lichter Reference Johnson and Lichter2019). Scholars have focused on the economic decline of former industrial hubs due to increasing competition from emerging economies and changes in the economic structure, as well as demographic decline, which have caused the erosion of basic public and private services and economic opportunities (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2016; Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer Reference Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer2020). Several reasons are developed by the literature to explain economic decline. They usually pertain to insufficient institutional and public support both from national governments and EU cohesion policies (Rodríguez-Pose et al. Reference Rodríguez-Pose, Dijkstra and Poelman2024) or the challenges posed by globalization and the modern economy (De Dominicis et al. Reference De Dominicis, Dijkstra and Pontarollo2022; Diemer et al. Reference Diemer, Iammarino, Rodríguez-Pose and Storper2022). The development of these ‘left-behind’ areas (McKay Reference McKay2019) and ‘places that don’t matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018, Reference Rodríguez-Pose2022) has thus been identified as a driver of a ‘geography of discontent’ (Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Poelman and Rodríguez-Pose2020). Due to their loss of economic growth, industrial production, and significant employment, along with demographic decline, these places are particularly receptive to feelings of economic deprivation and political discontent (Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Poelman and Rodríguez-Pose2020).

Looking at the consequences, several studies have demonstrated that these regional socio-economic disparities contribute to widening the gap in political attitudes and voting behaviours. In particular, structural inequalities have been primarily linked to lower electoral turnout (Bartle et al. Reference Bartle, Birch and Skirmuntt2017; Jöst Reference Jöst2023; Solt Reference Solt2010), as well as to the expression of radical, anti-system, populist, and Eurosceptic attitudes and voting behaviours in elections or contentious referenda (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Fetzer and Novy2017; Bin Zaid and Joshi Reference Bin Zaid and Joshi2018; Chaykina et al. Reference Chaykina, Cuccu and Pontarollo2022; Dvořák et al. Reference Dvořák, Zouhar and Treib2024; Fiorentino et al. Reference Fiorentino, Glasmeier, Lobao, Martin and Tyler2024; Greve et al. Reference Greve, Fritsch and Wyrwich2023; Han Reference Han2016; Jennings and Stoker Reference Jennings and Stoker2016; Rehák et al. Reference Rehák, Rafaj and Černěnko2021; Rickardsson Reference Rickardsson2021; Rodríguez-Pose et al. Reference Rodríguez-Pose, Lee and Lipp2021, Reference Rodríguez-Pose, Terrero-Dávila and Lee2023, Reference Rodríguez-Pose, Dijkstra and Poelman2024; Van Hauwaert et al. Reference Van Hauwaert, Schimpf and Dandoy2019; van Leeuwen and Vega Reference van Leeuwen and Vega2021; Vasilopoulou and Talving Reference Vasilopoulou and Talving2024). In addition, others have connected regional inequalities to higher political polarization (Bettarelli and Van Haute Reference Bettarelli and Van Haute2022).

However, although authors have acknowledged that the erosion of the economic and social fabric associated with declining regions has led people to express their dissatisfaction through the ballot box, little is known about its implications for democratic reforms and innovations. Past research has not yet explored the possibility that public support for DIs is influenced by structural economic context and that these alternative policy-making instruments may be particularly appealing to citizens living in regions where governing institutions face significant challenges in ensuring economic dynamism and prosperity for their residents. Indeed, structural economic decline may lead citizens in those disadvantaged regions to be more dissatisfied with and distrustful towards representative institutions, perceiving them as responsible for the situation and feeling politically unheard and disregarded. As a result of this, the support for democratic renewal and changing the status quo may increase – potentially through reforms that grant citizens greater influence over policy decisions, sometimes at the expense of representative actors. Additionally, while we know that populist and radical voters concentrate in left-behind places, it might not be surprising to see that DIs receive a higher level of support there, as those voters are particularly people-centric and supportive of participatory reforms (Heinisch and Wegscheider Reference Heinisch and Wegscheider2020; van Dijk et al. Reference van Dijk, Legein, Pilet and Marien2020; Zaslove et al. Reference Zaslove, Geurkink, Jacobs and Akkerman2021). By contrast, in more economically successful regions, citizens tend to have greater confidence in their institutions and to be more satisfied, reducing structural incentives for reforms and leading to lower support for DIs. Based on this reasoning, our third hypothesis contends:

Hypothesis 3: Support for DIs will be higher in poorer regions.

Extending this logic, if support for DIs in a negative economic environment stems from economic deprivation or political disaffection, we can expect to find an interaction effect between individual and regional-level factors. More specifically, the impact of the regional economic context should be twofold. First, a weak economic context should reinforce the effects of individual-level economic deprivation and political disaffection (Hypothesis 4). Second, it should mitigate the effect of individual-level political engagement (Hypothesis 5).

On the one hand, we expect economic deprivation and political disaffection to affect citizens’ support for DIs more in poorer regions. As suggested by economic voting theories (see, for example, Anderson Reference Anderson2007; Lewis-Beck and Nadeau Reference Lewis-Beck and Nadeau2011), economic conditions influence how voters assess political institutions and the performance of political actors. Consequently, incumbent parties are expected to lose votes in times of economic hardship because they are electorally punished for bad performances. Applying this logic to attitudes towards democratic innovations, when economic inequality and instability are prevalent in a given region, citizens are more likely to link their own economic insecurity or political dissatisfaction with overall regional economic performance. As a result, they may be even more inclined to support policy-making alternatives that enhance their representation and ensure their voices are considered in public policies. By contrast, in more prosperous regions, support for DIs among economically deprived and politically disaffected citizens should be lower, as there is less structural incentive to challenge governing institutions. If a region is relatively thriving and the incumbent government effectively addresses citizens’ needs in this area, economic deprivation and political disaffection are less likely to translate into support for DIs. Thus, the effect of those two individual-level drivers should be weaker in prosperous regions. This leads to the following cross-level interaction hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: In poorer regions, the effect of (a) economic deprivation and (b) political disaffection on support for DIs is stronger.

On the other hand, according to the political engagement hypothesis, DIs such as deliberative mini-publics (DMPs) and referenda are particularly appealing to those interested in politics and confident in their ability to participate. In contrast, disengaged citizens are assumed to oppose increased citizen participation, viewing it as a burden due to their lack of interest in political matters and feeling unprepared to contribute to policy making. They tend to believe politicians are elected to handle these responsibilities. However, we expect this gap to be smaller in poorer regions, a weak economic environment mitigating the relationship between political engagement and support for DIs. When political institutions consistently fail to meet citizens’ expectations and economic needs in a given region, disengaged citizens may also become more willing to support alternative forms of governance that challenge existing structures and enhance their representation, even if this requires their participation. This dynamic could help bridge the gap between engaged and disengaged citizens in terms of DI support. By contrast, in more prosperous regions, support for DIs is expected to come primarily from engaged citizens, driven by a desire for greater participation rather than a need for improved representation. Disengaged citizens, facing fewer structural incentives for institutional change, are less likely to turn towards DIs. In a positive economic environment, they may not perceive a need for greater involvement or for disrupting the current system. As a result, the gap in support for DIs is likely to remain significant, with engaged citizens showing stronger support. This leads to our last hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: In poorer regions, the effect of political engagement on support for DIs is weaker.

Synthesizing these arguments, Figure 1 encapsulates our main theoretical expectations, which aim to capture how the regional-level economic context directly affects support for DIs, but also interacts with the power of three key individual-level drivers.

Figure 1. Theoretical model.

Data and Methods

Data

The survey data were collected as part of the POLITICIZE project,Footnote 2 which examines citizens’ preferences for non-elected forms of politics. The project conducted a comparative survey of fifteen countries, outsourced to Qualtrics, and programmed in two rounds. The first round was fielded online (CAWI) in July 2021 for France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, and the United Kingdom, followed by a second round in January 2022 in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Ireland, and the Netherlands. As detailed in Appendix 1, this selection of countries ensures the contextual diversity needed for generalization, especially in terms of experience with democratic innovations and political power granted to regions. Qualtrics provided country samples of at least 1,500 respondents, ensuring they were representative of the national population in age, gender, education, and, crucially for this study, region of residence.Footnote 3 Respondents’ regional location was essential to incorporate relevant structural variables from public EU databases and build a unique dataset, allowing for a novel multilevel analysis of public support for DIs, considering both the direct and interaction effects of the structural economic context of the region where respondents resided.

Dependent Variable: Support for DIs (Referenda and Deliberative Mini-Publics)

In our analysis, we rely on three dependent variables. The first DV measures the level of support for a vote-centric DI, specifically referenda. The survey replicated the wording from the European Social Survey, asking respondents to rate their agreement with the statement: ‘It is important for democracy that citizens have the final say on political issues by voting in referenda’. Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (‘Fully disagree’) to 5 (‘Fully agree’). This question is widely accepted for studying public preference for referenda (Paulis and Rangoni Reference Paulis and Rangoni2023; Rojon and Rijken Reference Rojon and Rijken2021; Werner and Marien Reference Werner and Marien2022). As shown in Figure 2, most Europeans support referenda, though it varies by country.

Figure 2. Mean support for DIs by country.

The second DV measures agreement with a talk-centric DIs, specifically DMPs. Unlike referenda, DMPs are newer DIs, so there is less consensus on question-wording. Given the novelty of DMPs and the public’s unfamiliarity with them, the survey included a brief description to ensure understanding,Footnote 4 replicating existing wording (Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023): ‘People sometimes talk about the possibility of letting a group of citizens decide instead of politicians. These citizens will be selected by lot within the population and would then gather and deliberate for several days to make policy decisions like politicians do in Parliament’. Respondents were then asked about their level of agreement with the proposal on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (‘Fully disagree’) to 5 (‘Fully agree’). Figure 2 shows that respondents have a relatively neutral view of DMPs (slightly less positive than for referenda), with some variations across countries.

Given the positive correlation (r = 0.36), the third DV combines both into the average support for DIs. Appendix 5 shows support for DIs across regions. While regional differences exist and are more pronounced than across countries, the regional-level variance is relatively low. Thus, different types of individuals are likely support democratic innovations across regions with various economic contexts, as our interaction hypotheses suggest.

Independent Variables

To test Hypothesis 1, two individual-level independent variables were examined: economic deprivation and political disaffection. Economic deprivation refers to a condition in which individuals or households struggle to meet their basic needs (Wong, Reference Wong, Leal Filho, Marisa Azul, Brandli, Lange Salvia, Özuyar and Wall2021) and is measured by perceived household income security, using a question worded similarly to the European Social Survey: ‘Which of the descriptions below comes closest to how you feel about your household’s income nowadays?’ Respondents chose from a five-point scale ranging from ‘Living very comfortably on present income’ to ‘Very difficult on present income’. This subjective measurement avoids missing values associated with objective salary questions, is comparable across regions with varying living costs, and aligns with the micro-level deprivation concept of our theoretical framework. Political disaffection is understood as sceptical attitudes towards political process, politicians, and democratic institutions (Di Palma Reference Di Palma1970; Van Wessel Reference Van Wessel2010), which is operationalized via trust in representative institutions, using wording similar to the European Social Survey: ‘How much trust you have in each of the following institutions and actors: the parliament, political parties, politicians?’ This question is a benchmark in the field (Joxhe Reference Joxhe2023; Turper and Aarts Reference Turper and Aarts2017) and ensures relatively good equivalence across regime types (Schneider Reference Schneider2017). Respondents rated their trust on a scale from 1 (‘No trust at all’) to 5 (‘High trust’). Given the high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91), we created a mean scale from these three items. For Hypothesis 2, political engagement is measured through political interest. Respondents answered ‘How interested would you say you are in politics’ on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (‘Not interested at all’) to 4 (‘Very interested’).

Regarding regional-level predictors, to test Hypothesis 3 to Hypothesis 5, ‘poorer regions’ are defined as those with weak economic structural conditions, reflecting a greater difficulty for institutions to ensure economic growth and development. We use a key structural economic metric, gross domestic product per capita, which measures economic productivity (the value added, created through the production of goods and services during the year 2021, divided by mid-year population). This metric is commonly included in studies examining the relationship between contextual economic conditions and political behaviours (see, for example, Sipma and Lubbers Reference Sipma and Lubbers2020). GDP/capita correlates with other economic indicators and strongly with a measure of democratic performances (see Appendix 4), making it a reliable indicator of a region’s overall state. Additionally, we include dynamic measures of GDP/capita regional changes (over one, five, and ten years before the survey data were collected in 2021) for running robustness checks (see Appendix 8) while considering the long-term nature of economic decline in certain regions, which is central to regional studies on ‘left-behind places’ and ‘places that don’t matter’. Lastly, we include a regional-level dummy for ‘political importance’, indicating whether the country’s capital and government are located in the region. Regional-level data were retrieved from Eurostat and integrated into our survey dataset, matching the NUTS level of the respondent’s region of residence. We use NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 regional levels (see the table in Appendix 3 for a summary). In Ireland and Poland, we could not match individual-level survey data with NUTS levels due to the survey company’s reliance on former NUTS classifications. Therefore, we excluded these countries from the original sample. While the inclusion of regional economic indicators is a key strength of this study, we acknowledge the limitations associated with using NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 classifications. The definition of ‘regions’ varies significantly across countries, with some NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 units covering large and economically diverse areas. This may limit the ability of our analysis to capture localized economic conditions and micro-level variations in political attitudes. In smaller or more centralized countries, regional classifications may align more closely with meaningful subnational political and economic divisions, whereas in larger countries, NUTS 2 regions may aggregate diverse economic realities into a single category. Nonetheless, there is significant regional economic variation in our dataset (see the maps in Appendix 3).

Analytical Strategy

The lack of theoretical and empirical attention to the structural context in the study of public support for DIs can likely be attributed to certain methodological shortcomings. Previous studies typically rely on comparative surveys conducted across multiple countries, which report individual-level effects based on pooled sample analyses. Using countries as the geographical unit of reference often means that scholars lack sufficient observations at this level to effectively perform multilevel models capable of exploring structural factors. Therefore, we decided to scale down to the regional level to capture potential contextual effects.

We estimated multilevel linear regression models with respondents (N = 16,109) nested within regions (N = 91), using country dummies (N = 13). By including these dummies, we account for all country-level variance, eliminating the need to control for other country-level variables. Additionally, we controlled for a few other control variables in our regression models. At the individual level, in line with standard practices, we included socio-demographic variables as well as political attitudes that, according to existing literature, are associated with support for DIs. These variables included age, gender (0 male, 1 female), employment status (0 unemployed, 1 employed), educational attainment (following the International Standard Classification of Education [ISCED]), urbanity (1 living on a farm or home in the countryside, 5 living in a big city), self-reported left–right position (0 extreme left, 10 extreme right), and internal efficacy, measured through reversed responses on a scale of 1 (‘Fully disagree’) to 5 (‘Fully agree’) to the statement ‘Politics is too complicated for people like me’.

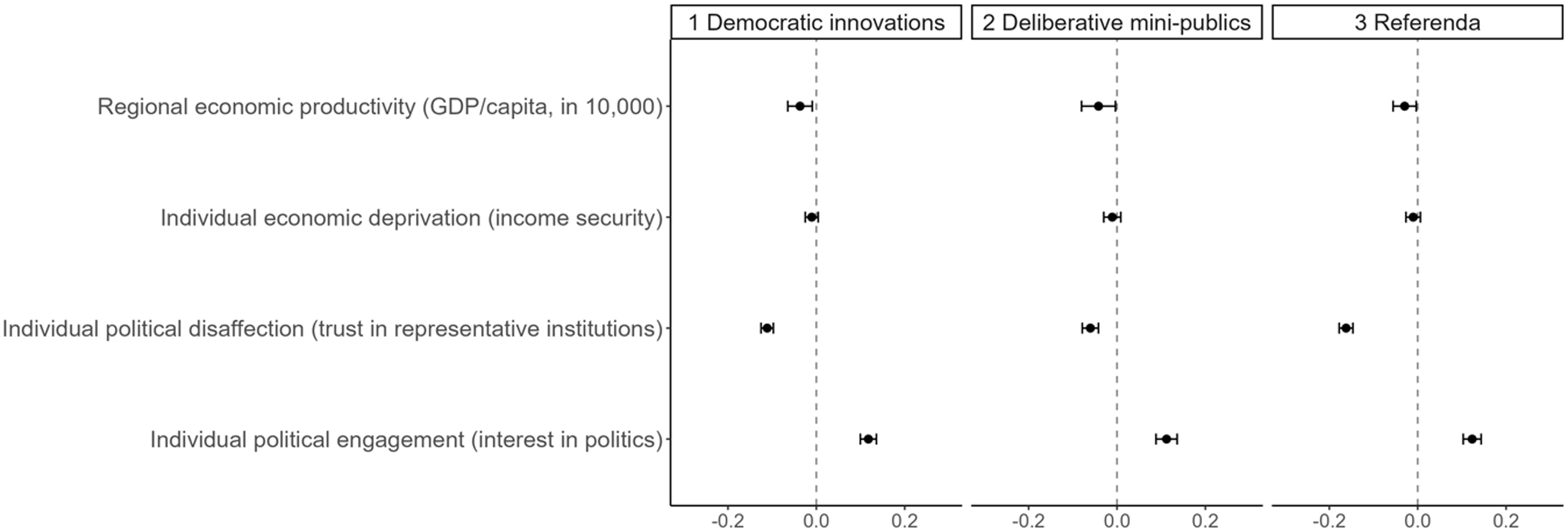

Our first estimation is a multilevel linear regression model with random intercepts, including all individual- and regional-level variables, to test Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2, and Hypothesis 3 (Figure 3). To test the cross-level interaction effects (Hypothesis 4 and Hypothesis 5), we estimated models with random intercept and random slopes for economic deprivation, political disaffection, and political engagement respectively (Figures 4 to 6). The full models are presented in Appendix 6.

Figure 3. Coefficient plots of support for DIs by regional and individual variables.

Note: the three models control for political efficacy, left–right self-placement, urbanity, education, employment status, gender, age, political importance of the region, and country dummies (see full specification in Appendix 6 Table A).

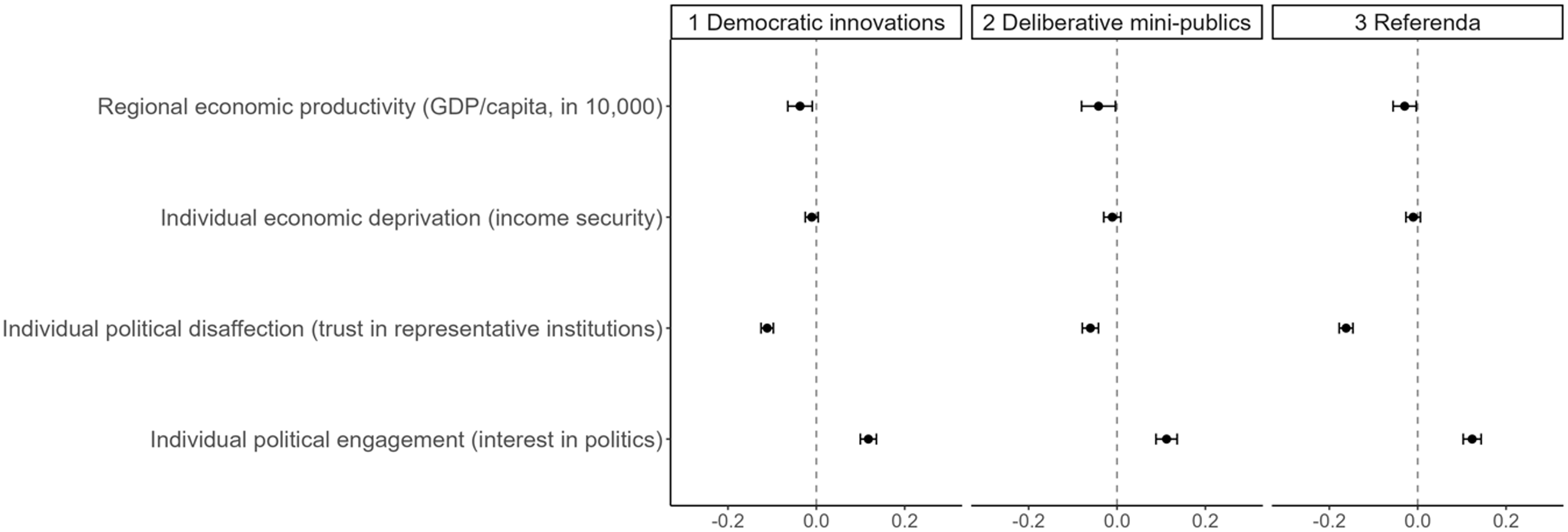

Figure 4. Effect of economic deprivation (income security) on support for DIs by GDP per capita (min/max).

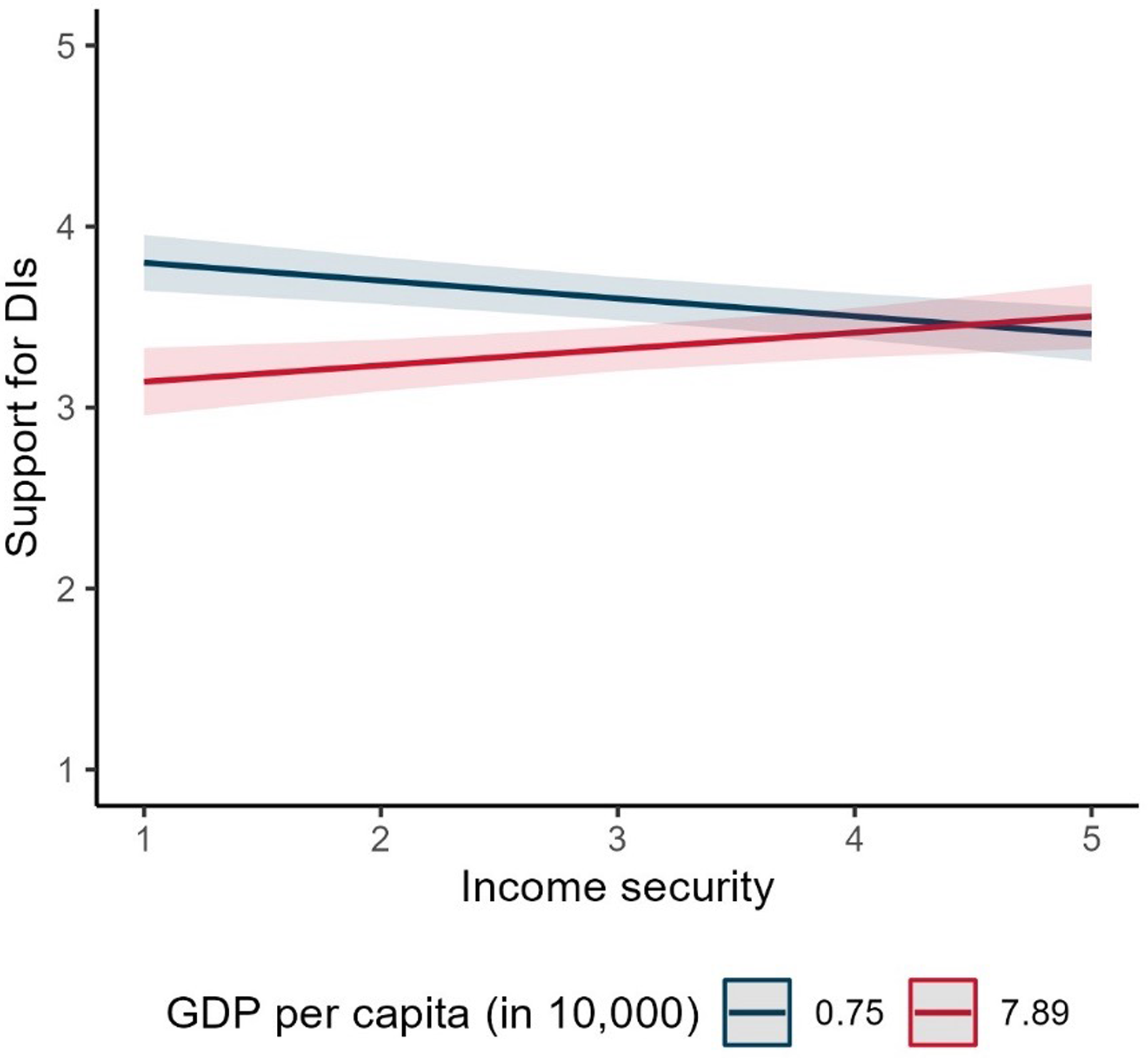

Figure 5. Effect of political disaffection (trust in representative institutions) on support for DIs by GDP per capita (min/max).

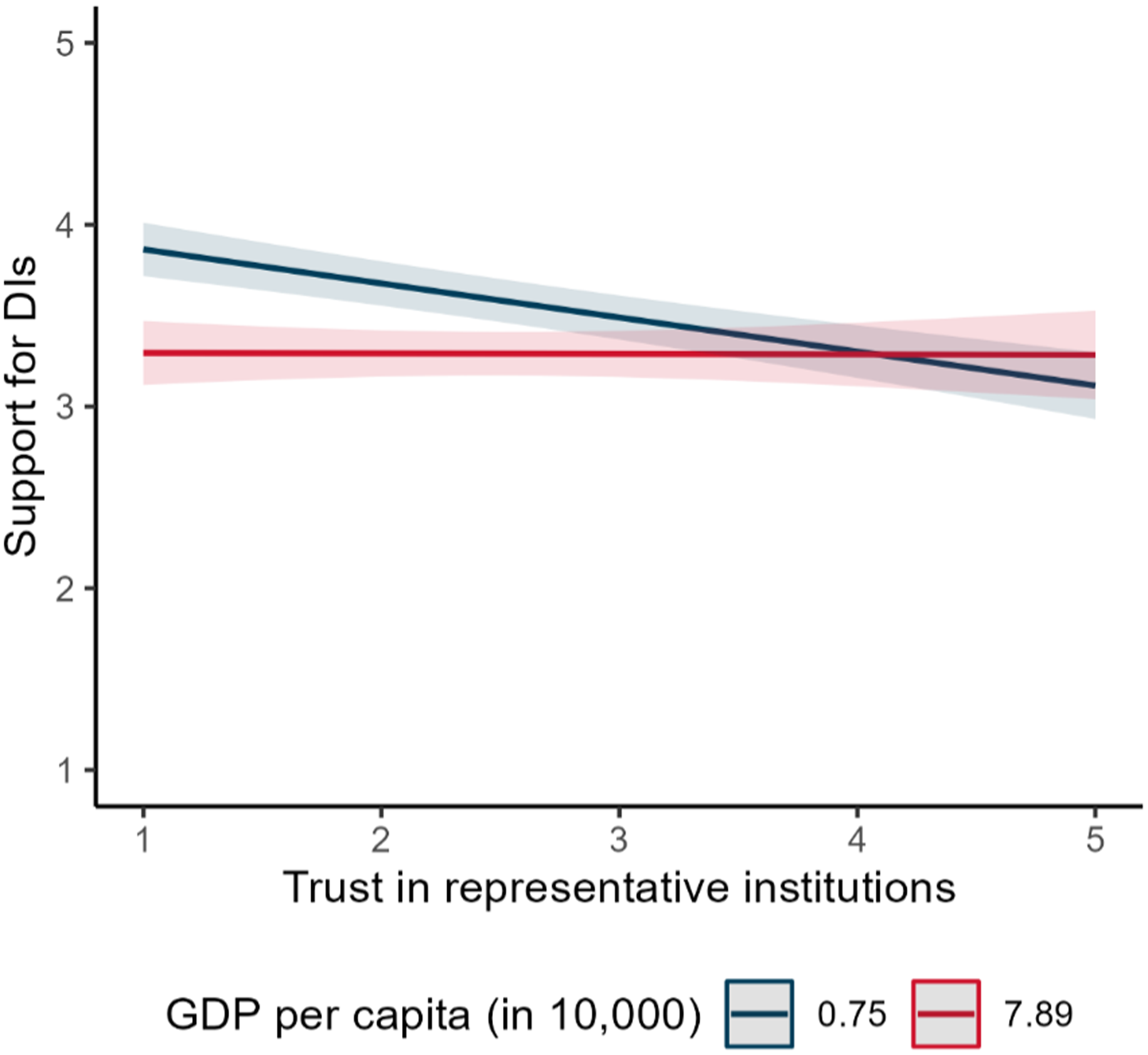

Figure 6. Effect of political engagement (interest in politics) on support for DIs by GDP per capita (min/max).

Results

The results of our analyses highlight several key findings (see Figure 3). Our first hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) expects support for DIs to be higher among citizens who feel (a) economically deprived (income insecurity) or (b) politically disaffected (distrust in representative actors). We found that subjective income is not significantly correlated with support for DIs. This finding thus contrasts with our expectations and previous studies (Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bedock, Talukder and Rangoni2024b, Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023; Walsh and Elkink Reference Walsh and Elkink2021), which did not consider regional-level economic indicators. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, political trust is significantly and negatively associated with support for DIs: the more trust in representative institutions, the less likely to support democratic instruments that would challenge the status quo and increase citizens’ power at the expense of politicians. Conversely, it means that DIs appeal to those who distrust representative actors, providing evidence for the political disaffection (or ‘enragement’) thesis. Overall, there is only partial support for Hypothesis 1: our results are inconclusive regarding economic deprivation but corroborate the positive relationship between political disaffection and support for DIs.

Simultaneously, the results presented in Figure 3 indicate that interest in politics is significantly and positively correlated to support for DIs: the higher the level of interest, the more support for DIs. This finding fully supports our second hypothesis (Hypothesis 2) and, more broadly, confirms the ‘political engagement’ thesis, which posits that participatory instruments such as DMPs and referenda are particularly valued by citizens who are politically interested and informed.

More importantly, our research aims to understand better the effect of the structural context on public support for DIs. The regression outcomes plotted in Figure 3 show a small but significant negative impact of GDP per capita, indicating that the higher the regional level of economic productivity, the lower the support for DIs. We thus find relatively modest evidence to support Hypothesis 3: support for DIs is slightly, though significantly, higher in poorer regions. As robustness checks (see Appendix 8), we also tested whether dynamic measures of regional economic productivity correlated with support for DIs, finding a similarly small but significant negative effect of the five-year change in regional GDP per capita.Footnote 5 Overall, our findings suggest that support for participatory policy-making instruments like DMPs and referenda is also rooted in the structural environment in which citizens live and depends on economic performances, with poorer contexts draining more positive attitudes towards DIs. Additionally, the results for the five-year change in regional economic performance may suggest that election cycles play a role, and, in particular, that citizens may be more favourable to DIs when the state of the regional economy has deteriorated over the last term. In other words, support for DIs may also arise as a sanction to ruling institutions that have failed to ensure economic growth in citizens’ regions.

Beyond the effect of the regional economic context in general, we are also interested in its interaction with individual-level predictors, assuming that the structural environment moderates the relationship between individual characteristics and support for DIs. Our results show a statistically significant, albeit modest, interaction between individual economic deprivation (income security) and regional GDP per capita in the full model (see Appendix 6 Table B). This interaction effect, plotted in Figure 4, suggests that support for DIs is higher among those who feel insecure and live in poor regions, compared to those living in richer regions. More importantly, the difference between rich and poor regions is no longer significant for individuals who feel financially comfortable. Supporting our expectations (Hypothesis 4a), the negative effect of individual economic deprivation on support for DIs is thus exacerbated in poorer regions, where economic productivity is lower. This observation holds also when using the five-year change in GDP per capita (see Appendix 8 Figure 1). This highlights how weak economic conditions reinforce the relationship between individual economic deprivation and support for DIs, strengthening economically deprived citizens’ positive opinions towards democratic reforms that ensure more power to citizens and decrease politicians’ influence, whom they likely perceive as responsible for the poor economic environment and less responsive to their needs.

We also examine the interaction between political disaffection and regional economic productivity (Figure 5). Fully supporting Hypothesis 4b, there is a significant interaction between individual trust in representative institutions and regional GDP per capita in the full model (see Appendix 6 Table C). In other words, people who distrust actors of representative democracy are relatively more likely to support DIs when they live in regions struggling to achieve economic performance. This structural context may strengthen their disaffection and hence its relationship to support for DIs, as it points towards institutional dysfunction and a failure of representative institutions to produce economic prosperity.

One interpretation of this first series of results is that the individual-level explanations of economic deprivation and political disaffection appear to fit better in poorer regions, with a weak structural economic context. In other words, DIs appeal to disadvantaged social and political groups only when they live in a poor structural environment, which suggests that elected politicians ‘do not do their job’. Once institutions are more efficient and achieve better economic performance, this difference seems to vanish, highlighting how improvement in structural conditions can lead people – despite negative views about their own economic situation or political institutions – to remain supportive of the democratic status quo and less attracted by participatory reforms. This is a crucial contribution to the study of public support for DIs as it nuances well-established findings.

To address Hypothesis 5, we explored the moderating effect of the structural context on the relationship between respondents’ political engagement and support for DIs. As illustrated in Figure 6, there is a significant interaction with political interest. Overall, politically interested citizens support DIs regardless of the regional economic context in which they reside. On the other hand, politically disinterested citizens are generally less favourable toward DIs, unless they live in a poor region. For those disengaged citizens, low economic productivity in their region drives an increased willingness to change the status quo by implementing participatory instruments like DMPs and referenda, which may offer them better representation and influence over public policies. Additionally, the results reveal again an important nuance to the existing literature, as the ‘political engagement’ thesis applies primarily to wealthier regions. Figure 6 shows that political interest explains differences in support for DIs only in regions with higher economic productivity – or that have significantly improved their economic productivity over the last five years (see Appendix 8 Figure 1).Footnote 6 These findings suggest that political engagement is more influential under these specific favourable economic circumstances and that citizens of regions that are efficiently governed may turn to new participatory opportunities not because they seek better representation and more efficient or responsive institutions, but simply because they wish to participate more.

Conclusion

In a context of democratic erosion and challenges, several voices from academia, civil society, and even political parties have increasingly argued in favour of implementing democratic innovations. Crucial to their legitimacy, scholars have sought to understand why public opinion would support these novel participatory instruments and whom they might particularly appeal to. Our study contributes to this ongoing debate by addressing a specific gap. While most studies investigate individual-level determinants of support for DIs, to our best knowledge, our study is the first to examine the impact of structural factors. We know that support is not homogenously distributed in the population. Certain groups of citizens, for example, those who are economically deprived and politically disaffected – but also those politically engaged, tend to be more supportive. At the same time, regional studies emphasize that economic and political disadvantages are strongly rooted in the place where individuals live and in the presence of structural inequalities. This study, therefore, investigates how the regional economic context influences public support for DIs and how it mediates the well-established relationships between individual factors (economic deprivation, political disaffection, and political engagement) and preferences for participatory policy-making instruments that shift power from elected politicians to non-elected citizens, whether through referenda or deliberative mini-publics.

Building on a unique dataset combining individual-level survey data with short-term and long-term structural economic indicators captured at the regional level and developing a multilevel analytical strategy, our analysis allows us to underline several key findings. First, although individual drivers have a stronger impact, the economic context still plays a small yet meaningful role in public support for DIs. We demonstrate that weak economic structures foster public support for changing the status quo, encouraging positive views on democratic alternatives that will give more power to the citizenry. In other words, when traditional governance structures fail to deliver economic outcomes in their areas of residence, citizens are inclined to support reforming the current system through implementing more DIs. Second, we find that the structural economic context amplifies individual determinants of support for DIs. Citizens living in poorer regions, that is, with lower economic productivity, feel the effects of negative attitudes (economic deprivation, political disaffection, and political disengagement) more acutely, which strengthens their support for DIs. Feeling excluded from politics and finding political institutions not responsive to their economic needs, DIs are perceived by deprived, disaffected, and disengaged citizens as promising alternative channels to make their voices heard and foster their representation and influence in policy making when structural inequalities prevail. Yet, we also observe that politically engaged citizens are more likely to support DIs, particularly in wealthier regions with a better economic context. For this group of citizens, their attraction to DIs seems not to be driven by the need for representation and inclusion but rather by their willingness to participate more in politics.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that citizens’ support for DIs varies by context and is driven by different motivations. This adds important contextual nuance to two key theories explaining public support for DIs (Bedock and Pilet Reference Bedock and Pilet2020a; Bengtsson and Mattila 2009; Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Bol, Vittori and Paulis2023). On the one hand, the ‘enraged’ theory, which argues that DIs appeal to citizens with negative social attributes and political attitudes seeking better inclusion and representation, appears less universal than previously assumed, as it holds primarily in poorer regions. Under conditions of structural inequality, ‘enraged’ citizens support DIs to improve their representation and make the system more inclusive and effective. On the other hand, the ‘engaged’ theory, which suggests that DIs attract politically interested citizens, holds mainly in wealthier regions, where support for DIs likely stems from a desire for greater participation rather than institutional grievances. By highlighting the role of regional economic conditions in shaping who supports DIs and why, our study has important normative implications for policy makers, practitioners, and researchers. First, policy makers introducing DIs must recognize that public support depends not only on individual attitudes but also on regional economic conditions. In economically disadvantaged regions, DIs may help channel institutional grievances and enhance representation, but without substantive policies addressing economic inequalities, they risk reinforcing perceptions of political neglect. Second, these findings emphasize that organizers of participatory processes should be aware of different expectations of citizen participation depending on the regional context. In poorer regions, participation could be perceived as a way to counterbalance current policies. Outreach strategies may therefore focus on engaging economically and politically marginalized citizens. In wealthier regions, participation may be driven more by civic engagement than institutional distrust. Finally, from a theoretical perspective, these results call for greater attention to structural inequalities in democratic innovation research. While much of the literature focuses on individual preferences for participation, our study underscores that support for DIs is also embedded in the economic structures in which citizens live.

Our study also comes with limitations, which call for other interesting further research orientations. First, we examine concomitantly support for DMPs and referenda as support DIs, while they are based on a different logic. DMPs emphasize deliberation and consensus-seeking among a selected group of citizens, while referenda involve the entire electorate in producing a clear outcome. Although our results for both instruments generally point in the same direction, it would be worthwhile to further explore differences between these instruments and the underlying mechanisms of support. At the same time, the focus could expand to other types of DIs and forms of citizen participation. Second, the regional-level context is measured at the NUTS 1 or NUTS 2 level, and, for some countries, these are relatively large regions that are neither administrative units nor reflective of a strong regional identity. Future research could address this limitation by incorporating finer-grained data at the NUTS 3 level or supplementing regional indicators with geospatial economic measures that capture intraregional disparities more precisely. As a result, the effect size of regional-level factors may eventually increase. Third, regional studies often associate ‘places that don’t matter’ or ‘left-behind places’ with long-term structural decline. Given that we generally found similar relationships between static and dynamic economic structural metrics, we do believe that providing dynamic and longitudinal analyses could make the findings even more robust and advance the research agenda we put forward. There is a need to further investigate the long-term effects of economic decline on democratic attitudes and examine how regional governance structures shape public responses to participatory reforms. At the same time, incorporating other spatial indicators, and particularly the urban–periphery dimension, could probably further enrich the picture we aim to draw. Finally, economic factors reveal only one side of the coin; other individual and contextual elements also shape support for DIs. On the demand side, normative conceptions of democracy – such as populist attitudes, political cynicism, trust in fellow citizens, ideology, and party preferences – may play a significant role (Paulis and Rangoni Reference Paulis and Rangoni2023; Pilet et al. Reference Pilet, Vittori, Paulis and Rojon2024a), particularly in economically deprived regions. On the supply side, support for DIs may be influenced by political actors advocating for them (Gherghina Reference Gherghina2024; Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Pilet and Mitru2023; Ramis-Moyano et al. Reference Ramis-Moyano, Smith, Ganuza and Pogrebinschi2025), their institutionalization in certain regions (for example, Belgium) or major cities (Paris, Barcelona, Warsaw), and calls from civil society or academia. This research opens further avenues for comparative studies to systematically incorporate these elements.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425100549

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PYJZ0V

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the convenors of the ECPR Standing Group on Democratic Innovations for awarding this paper the ‘Best Paper Prize 2024’ at the 2024 ECPR General Conference. They also wish to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback. In addition, they would like to extend their gratitude to the PI of the POLITICIZE Project, Jean-Benoit Pilet.

Financial support

This study received financial support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 772695 – project Cure or Curse); the COST Action (CA22149 – CHANGECODE) ‘Research Network for Interdisciplinary Studies of Transhistorical Deliberative Democracy’; and the project ‘Revitalized democracy for resilient societies’, funded by the Dutch National Science Agenda and Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (grant number NWA.1292.19.048).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial, professional, or personal interests that might have influenced the performance or presentation of the work described in this manuscript.

Ethical standards

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) on 19 December 2020, and from the Data Protection Officer (N° R2019/001) on 23 September 2019.