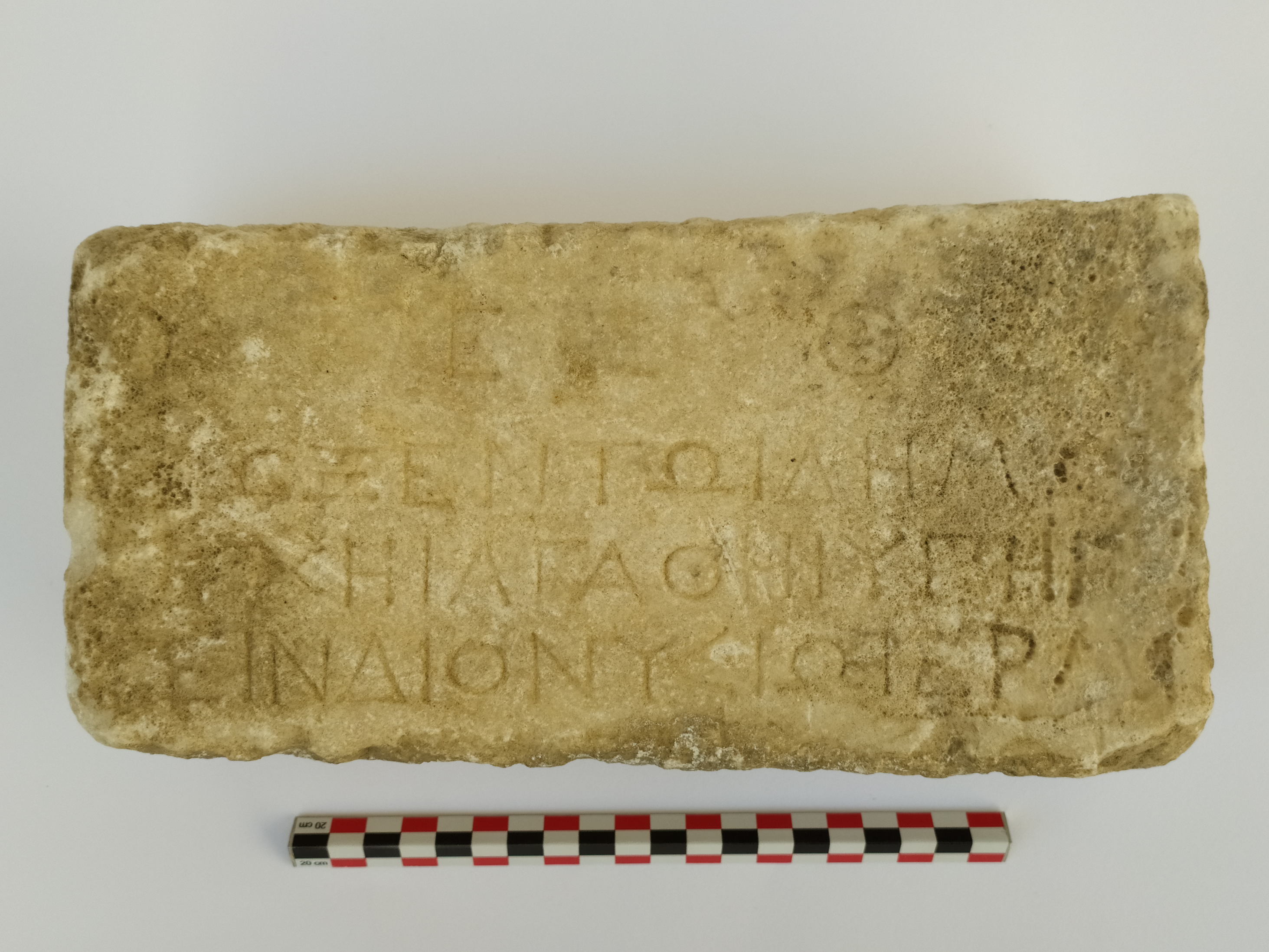

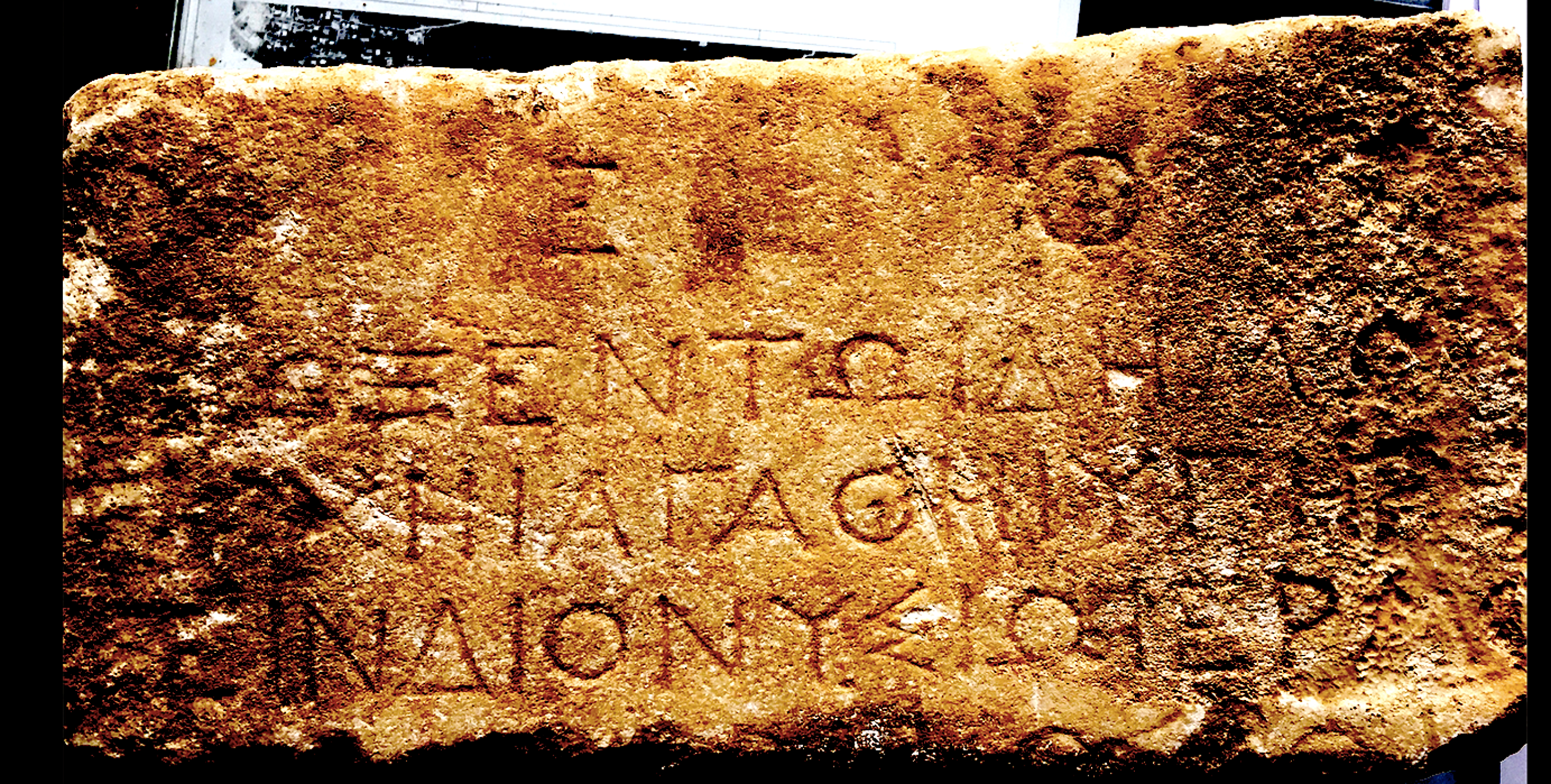

I. The inscribed decree: Paros Museum AK 2126

Discovered in the area of Tholakia Paroikias, the decree was presented to the Paros Museum on 18 May 2018 by N. Kalantzes. It is now held in the museum’s storeroom. Part of a stele of white marble which appears complete on its left- and right-hand sides, it is broken at the bottom and perhaps the top; the front face is worn, especially on the left- and right-hand sides. Only the front face is inscribed; the sides are smoothly finished and the back is worked to create a dappled surface. Preserved dimensions: h. 120mm (left) – 130mm (right); w. 263mm; th. 75mm. Letter heights: l. 1: 15mm (omicron; epsilon); ll. 2–5: 11mm (omicron) – 14mm (alpha). Autopsy: Constantakopoulou, Kourayos, Liddel 2018. See figs 1 and 2.

Fig. 1. Paros Museum AK 2126.

Fig. 2. Paros Museum AK 2126 (digitally enhanced).

ll. 4–5: alt. Ἑρμο[δώρου]; Ἑρμο[γένου]; Ἑρμο[κράτους]

l. 5: Only remnants of the tops of letters are visible

Gods! It was resolved by the people, with good fortune, to serve/take care of [something] for Dionysios, son of Hermo[kritos?], the Syracusan.

The stone appears to preserve its original left- and right-hand sides. Wear to the face means that the beginning and end of some lines are unclear. The size of the letters is paralleled in other (fragmentary) fourth-century decrees of Paros including IG XII.5 116, which features letter heights of 12–13mm.Footnote 1 The letters of l. 1 are broadly but evenly spaced and are spread, as a heading, across the whole breadth of the text. The readings of the first four lines of the text are very clear; only the tops of a number of letters of l. 5 are preserved, but enough remains to provide clear evidence for the letters outside square brackets in this edition. The letter forms are very tidy; they feature distinctive sigmas with splayed top and bottom diagonals, epsilons with a shorter middle horizontal and mus with slightly curved outer uprights; they are plausibly those of an early or mid-fourth-century Parian decree.Footnote 2 The width of the stone, 263mm (its original width), is compatible with a much taller stele than that preserved here.Footnote 3 But, it is impossible to tell how much of the upper or lower portions of the stone has been lost and, therefore, the original length of the inscribed decree.

This text appears to be a decree of a dēmos, probably, given the discovery, that of the Parians. It opens with an imprecation to the gods, paralleled in Parian inscriptions (IG XII 5.110, 116, 185).Footnote 4 In this case, as in the others, the four letters of θϵο[ί] are spread across the full width of the inscribed text;Footnote 5 this perhaps reflects both the religious context of the enactment of the decree (such as the prayers with which a meeting of an assembly commenced) as well as invoking divine agency in protecting the decree or assuring its success.Footnote 6 The text also invokes ‘good fortune’ at the end of the enactment statement, perhaps a reference to the cult of Good Fortune at Paros.Footnote 7 The decree lacks the name of a proposer (known in other Parian decrees, for example, IG XII 5.110 l. 3, 111 l. 2). The enactment formula ἔδοξϵν τῶι δήμωι (‘it was resolved by the people’) is striking as the formula ἔδοξϵν τῆι βολῆι καὶ τῶι δήμωι (‘it was resolved by the council and the people’) is more common in Parian inscriptions (IG XII 5.110 ll. 2–3 and 111 l. 1).Footnote 8 Parallels from Athens allow us to assess the significance of this formula. ἔδοξϵν τῶι δήμωι is known in the earliest Athenian decrees:Footnote 9 in the fourth century, the Athenians used it when the assembly was enacting a decree which did not directly approve the recommendation of the council (non-probouleumatic decrees).Footnote 10 This occurred, P.J. Rhodes and Robin Osborne surmise, ‘either because the council made a recommendation which it rejected or because the council made no recommendation’.Footnote 11 This might include circumstances where the people enacted a decree that was proposed from the floor of the assembly in the course of a discussion of a probouleuma sent to it by the council or where the assembly passed measures that were separate from, but supplementary to, a previous probouleumatic decree. Indeed, in the present case it might be that the extant decree of the dēmos alone made arrangements for the inscription of a previously enacted but uninscribed decree of the council and dēmos (for development of this suggestion, see below). Accordingly, it does not necessarily indicate any particular constitutional configuration (though the formula suggests that the Parian dēmos was functioning as a sovereign body at this point) but rather the procedure of enactment: in this case, all we can say with relative certainty is that this decree derived from a proposal made from the floor of the Parian assembly.

The reading in l. 4 of ‘Dionysios Hermo-’ is secure. Restorations of the patronymic might include common names such as ‘Hermo[doros]’, ‘Hermo[genes]’ or Hermo[krates]’. Indeed, the online LGPN database has 32 attestations of names with Hermo- as the first element of the theophoric name in the region of the Aegean Islands and 61 overall attestations.Footnote 12 However, the reading ‘Syr[a]kos[i]ōi’ in l. 5 makes it attractive to restore ‘Hermo[kritos]’: Dionysios son of Hermokritos (sometimes known in the literary tradition as son of Hermokrates)Footnote 13 the Syracusan was, of course, the famous tyrant of Syracuse (ca. 430–367 BCE). When the Athenians developed relations with Syracuse in the 390s and 360s, they honoured (RO 10), negotiated with (RO 33) and established an alliance with (RO 34) Dionysios, whom they described as the ‘archon’ of Sicily, which was evidently acceptable to him and in tune with Athenian political designations;Footnote 14 on the other hand, the Parian decree gives no indication of his political position but rather mentions his patronymic and ethnic, the absolutely standard way of referring to an individual.

Much of our understanding of this new decree hinges on the interpretation of ὑπηρε̣[τ]ϵῖν. One possible translation is ‘to serve someone (dat.) with something (acc.)’: this is one meaning of the verb + dative offered in LSJ (s.v. ὑπηρϵτέω, II.2–3). ὑπηρϵτϵῖν may be used in the specific sense of military service or the provision of naval personnel.Footnote 15

A fragmentary fifth-century Athenian inscribed decree regulating Milesian affairs includes the word in restored form,Footnote 16 and Thucydides’ statement that the Milesians actively participated in the Athenian army (4.42.1) might support the inference that military services were specified. Therefore, an explanation of ὑπηρϵτϵῖν as referring to an offer of military or some other kind of subservience seems plausible for the Parian decree. In that case we would have to presume that an accusative subject of the infinitive ὑπηρϵτϵῖν would have followed in a portion of the decree now lost: this subject would have indicated who would serve Dionysios. Possibilities include the citizens (τοὺς πολίτας), ‘the Parians’ (τοὺς Παρίους), mercenaries (τοὺς ξένους) or even particular magistracies, such as the polemarchoi or stratēgoi.Footnote 17 Against this interpretation, however, is the fact that decrees which directly concern the dispatch of troops on specific occasions are, like other decrees concerning ephemeral matters, not usually physically inscribed. ὑπηρϵτϵῖν might still refer to some kind of subservience rather than specifically military service (cf. Dem. 18.138; [Dem.] 59.35), but it is doubtful that the Parians would have wanted to record subordination to a tyrant in stone.

There are alternative, better, translations which are more sensitive to the type of provisions that are regularly inscribed in the fourth century BCE and later. At Samos, Priene and Minoa (Amorgos) in the third century BCE, ὑπηρϵτϵῖν is used in instructions to magistrates organizing financial arrangements related to the publication of an inscription (IG XII 6.95 ll. 42–43: τὸν δὲ ταμίαν ϵἰς τὸ ἀνάλωμα τῆς στήλης καὶ τῆς ἀναγραφῆς ὑπηρϵτϵῖν; IG XII 7.221b ll. 25–26: τοὺς δὲ ταμίας ϵἰς ταῦτα ὑπηρϵτϵῖν δανϵισαμένου; IPriene 29 ll. 18–19: τὰ δὲ ἀναλώματα τὰ γϵνόμϵνα ὑπηρϵτϵῖν τοὺς οἰκονόμους). Using these texts as parallels, one way of interpreting the lack of probouleusis in this Parian inscription is that its extant portions record a supplementary decree providing for the publication on stone of, say, an earlier honorific decree for Dionysios which would have been reproduced beneath the supplementary decree. In that case we would translate along the lines of ‘the dēmos decided to take care (or that a later-specified magistrate should take care) [of the inscription (ἀναγραφή) of the decree] for Dionysios’.

A third possible interpretation draws upon a contemporary (369 BCE) use of ὑπηρϵτϵῖν from Troezen (IG IV 748 ll. 6–7: ὁ δᾶμος ὁ Τροζανίων ὑπηρέτηκϵ πάντα) in a reference to services performed by the polis on behalf of an honorand at their request. Indeed, in a Delian decree of 300–250 BCE ὑπηρϵτϵῖν is used to refer to the taking care of future requests by an honorand (IG XI 4.562 ll. 22–25: ἐπιμϵλϵῖσθαι δ’ αὐτῶν τὴμ βουλὴν τὴν ἀϵὶ βουλϵύουσαν καὶ ὑπηρϵτϵῖν ἐάν του δέωνται). So, following this parallel, the implication could be that the decree is made ‘to take care of, for Dionysios, [the requests which he made/which he might make…]’. Below we offer a possible context for those services or Dionysios’ request.

We have suggested three possible interpretations of the meaning of ὑπηρϵτϵῖν so far. These interpretations vary in how they substantiate the relations between the Parians and Dionysios, ranging from the subordination to Dionysios of Parians dispatched to ensuring the inscription of a decree, to making provisions for current or future requests. All three possibilities indicate interaction between the two parties. Notwithstanding the uncertainty surrounding the precise nature of this interaction, we now turn to exploring the historical implications of this relationship. We propose that the inscription should be placed in the period between 385 (on the basis of Diodorus’ dating of the foundation of Pharos by the Parians and Dionysios to 385/4, 15.13.4–14.2) and 367 BCE (the death of Dionysios of Syracuse).

II. Historical context: interactions between Parians and Dionysios in the Adriatic

At first glance, what we have is a decree of the Parian people appearing to issue an order (directed at a group of people now lost) to ‘serve’ Dionysios of Syracuse or ‘take care’ of something for him. It is possible to explain this by reference to the historical context of associations between Parians and Dionysios in the first half of the fourth century BCE and their shared interest in the Adriatic.

Ancient sources reveal connections between the Parians and the court of Dionysios of Syracuse. The historian Philistos of Syracuse (an associate of Dionysios: see Diod. Sic. 13.91.4) was said to have been a pupil of the elegiac poet Euenos of Paros (Suda φ 361, 365). An anecdote preserved in Polyainos’ Stratēgēmata records how a group of Parian Pythagoreans residing in Metapontum challenged Dionysios when he addressed the people there. This specific anecdote has been discussed in scholarship with various degrees of belief in its historicity.Footnote 18 While it is difficult to establish with certainty that Polyainos recorded an actual historical confrontation, the preservation of the anecdote implies that an association between the tyrant and the Parians meant that the story appeared convincing to its contemporary audience.

The most apparent links between Paros and Dionysios, however, are those concerning their shared interest in the region of the Adriatic Sea. A number of ancient sources record that the Parians established a settlement on Pharos, an island in the Adriatic, identified with modern Hvar, off the coast of Illyria; research has located the settlement on the Stari Grad plain.Footnote 19 Archaeological evidence shows that the settlements there were at locations where trading posts had developed over the course of the fifth century. Evidence from Hvar, in particular, points to the existence of archaic trade with settlements in the Ionian Sea.Footnote 20 The sources differ as to who established the settlement. The longest and most detailed account is that of Diodorus (15.13.4–14.2), who places it in 385/4 and presents it as a joint operation between the Parians and Dionysios (συμπράξαντος αὐτοῖς Διονυσίου, 15.13.4).Footnote 21 Other sources mention Paros alone as the metropolis of Pharos.Footnote 22 Indeed, Strabo tells us that originally the toponym of Pharos was Paros (Φάρος ἡ πρότϵρον Πάρος, Παρίων κτίσμα, ἐξ ἧς Δημήτριος ὁ Φάριος, 7.5.5).

Diodorus narrates that the establishment of the settlement of Pharos by the Parians was the result of an oracle (Πάριοι κατά τινα χρησμὸν ἀποικίαν ἐκπέμψαντϵς ϵἰς τὸν Ἀδρίαν ἔκτισαν ἐν αὐτῷ νῆσον τὴν ὀνομαζομένην Φάρον, 15.13.4), perhaps Delphi, which played a key role throughout Greek history in colonial contexts; Dodona is another possibility.Footnote 23 Diodorus places the reference to the establishment of the settlement on Pharos within the larger narrative of Dionysios’ interests in the Adriatic. His ‘co-operation’ (συμπράξαντος) with the Parians was not his only foundation in the area; before Pharos, Diodorus tells us, he ‘had already dispatched an apoikia in the Adriatic … and he had built a city called Lissos’ (οὗτος γὰρ ἀποικίαν ἀπϵσταλκὼς ϵἰς τὸν Ἀδρίαν οὐ πολλοῖς πρότϵρον ἔτϵσιν ἐκτικὼς ἦν τὴν πόλιν τὴν ὀνομαζομένην Λίσσον, 15.13.4).Footnote 24 Where or what Lissos was, is difficult to establish. It is likely, as P.J. Stylianou suggested, that the Syracusan settlement there was extremely short-lived.Footnote 25 It is unclear whether the establishment of Lissos was indicative of co-operation or rivalry between Dionysios and the Parians; however, later developments (see below) suggest that it gave rise to a context for co-operation.

Our knowledge of Greek interest in the Adriatic through the foundation of settlements is enriched by the information provided in lead tablets from Dodona. A number of tablets record the oracular consultations at Dodona related to the joining of the settlement at Pharos. Nine are dated to the period between the early fourth (the date of the settlement of Pharos) and second century BCE, and another (3030A DVC) is dated to the end of the fifth century.Footnote 26 These nine tablets reflect an active interest in Pharos, for commercial reasons (such as 3030A and 3517A DVC), or are related to safety (2762A DVC). The ethnicity of those who consulted the oracle is difficult to establish, as few of the tablets record names and even those recorded are inconclusive.Footnote 27 The tablets mentioning Pharos reflect typical anxieties expressed by individuals related to safety and travel, as well as concerns about prosperity. More specifically, LOD 6B records the following question: ‘Is it better and more good for me to live among the Parians in Paros by the Ionian Gulf?’ Such an enquiry highlights that the Parians’ settlement on Pharos (which must be what is referred to as ‘Paros by the Ionian Gulf’) created a potentially favourable context for other Greeks to consider relocating there. In other words, the Dodona tablets, and specifically those dated to the fourth century and therefore attesting to the initial stages of the Parian settlement, complement Diodorus’ narrative on it.

Furthermore, it appears that Pharos was not the only Parian settlement in the Adriatic: there is a single reference in Stephanos Byzantios to Anchiale which identifies it as a Parian settlement: ἔστι δὲ και Ἰλλυρίας ἄλλη, κτίσμα Παρίων, παρ᾽ ᾗ κόλπος Ἐνϵστηδὼν λϵγόμϵνος, ἐν ᾧ ἡ Σχϵρία (Ethnika23.21 Meineike). This appears to have been an earlier endeavour which must have disappeared by the fourth century.Footnote 28 Thasos, too, another Parian colony, had a non-negligible presence in the Adriatic in the fifth and fourth centuries.Footnote 29 Indeed, an inscription from the sanctuary of the Patrooi on Thasos, dated to the third quarter of the fifth century, records a dedication to Zeus Ktesios and Patroos by a group called Anchialideis.Footnote 30 Could this be a reference to the Parians settled in Anchiale, who maintained connections with Thasos before disappearing? It is likely, but we cannot be certain. At any rate, the disappearance of Anchiale from our sources is not unique: an Athenian decree of 325/4 regulates the execution of a previous decision to found a colony in the Adriatic (IG II3 1.370 = RO 100; see below). No trace of such an Athenian settlement has been found, perhaps because it was unsuccessful.Footnote 31

The reference to an earlier Parian settlement at Anchiale reveals the deep roots of Parian involvement in the Adriatic. The foundation of Pharos in 385, with or without Syracusan assistance, should be viewed exactly in this context of Greek, and specifically Parian, engagement with the networks of communication and exchange in the Adriatic. The Dodona tablets, as we have seen, include a late fifth-century enquiry about ‘sailing to Pharos’.Footnote 32 Theokleidas, who consulted the deity at Dodona on this point, may have been undertaking this journey for the sake of trade and commercial activity. We know now that the establishment of settlements normally followed a sometimes substantial period of mostly peaceful interaction in the region. Pharos is no exception to this: the presence of archaic Greek pottery on Hvar indicates active networks of exchange and possibly the presence of a Greek trading post.Footnote 33 Parian interest in the Adriatic, therefore, predates the establishment of Pharos.

Why did the Parians establish a settlement on Pharos? The answer is certainly complex. The very foundation of Pharos shows that the Parians already had an excellent knowledge of the region, which was enhanced by the, probably failed, earlier foundation of Anchiale. A foothold in the Adriatic offered access to substantial networks of exchange related to a number of important products, such as timber (the mountains along the east coast of the Adriatic being incredibly rich sources),Footnote 34 corn or even dogs, such as the renowned Molossian breed.Footnote 35 Additionally, the agricultural productivity of the island itself must have been appealing.Footnote 36 Considering the importance of marble for the Parian economy throughout the ages,Footnote 37 it is likely that establishing a foothold in the Adriatic would greatly enhance the potential for exports of Parian marble and sculpture distribution in that region.Footnote 38 Control of piratical activity in the area would have been another important parameter. Indeed, the Athenian decree of 325/4 can be used here as an indicative parallel (IG II3 1.370 = RO 100; see above).

The Athenian decree is inscribed on the same stone as an account of the naval epimelētai; it regulates the effective management and execution of a decision taken in a previous decree that concerns the establishment of a colony (apoikia) in the Adriatic. The measures included in this decree are characterized by urgency: this must be done ‘as swiftly as possible’ (ὅπως ἂν τὴν [ταχίσ]την πράττηται, ll. 4–5). The rationale behind this decree is also spelt out: ‘in order that the People may have for all time their own markets (emporia) and grain transport (sitopompia), and by the establishment of their own naval station (naustathmos) may have protection against the Tyrrhenians … those Greeks and barbarians who sail the sea may sail [safely?] to the Athenian [market bringing grain?] and other things’ (ll. 48–54, 57–62; tr. AIO, adapted). The original decree regulating the foundation of the colony is not extant, but the preserved decree clearly highlights security against the Tyrrhenians, commerce and grain transport as key parameters in the decision process. The three benefactors of the establishment of an Athenian naval station in the region is also worth highlighting: the decree specifically mentions that this will secure not just the ‘people’ (i.e. the Athenians), but also the Greeks and barbarians who sail the sea.Footnote 39 It is perhaps not unreasonable to see parallels behind the historical context of this Athenian decree and the Parian settlement as much as 60 years before. Access to grain, facilitation of commerce (including, possibly, that of marble, the best-known Parian product in antiquity) and an effective way of dealing with the threat of Tyrrhenian pirates in the Adriatic may have all played a role in the Parian decision to found a colony on Pharos. Indeed, the Parian settlement on Pharos is part of a larger Greek drive to establish footholds in the Adriatic.Footnote 40 We could even view Pharos as a ‘threshold’ location in the larger region, that is a zone mediating contact between different regions and their respective cultures.Footnote 41

Let us return to Diodorus’ account. Diodorus goes on to say that during the following year, that is 384/3 BCE, the Parians, who had built a city by the sea and constructed a wall around it,Footnote 42 were attacked by the ‘barbarian’ inhabitants of the island, who called on the Illyrians on the mainland for assistance; more than 10,000 of these crossed over to Pharos in small boats and killed many Greeks (15.14.1–2). However, the Dionysios-appointed governor (eparchos) of another Syracusan settlement, Lissos (see above), responded and assisted the Parians by sending ‘many triremes’ against the Illyrians’ boats; in the process 5,000 were slaughtered and 2,000 taken prisoner (15.14.2).Footnote 43 After this, Dionysios made war on Tyrrhenia in an operation aimed at plundering the land with a view to preparing for war against the Carthaginians (15.14.3–4).

Diodorus’ description presents Dionysios’ assistance to the Parians on Pharos as part of a deliberate expansionist plan by the tyrant to control the Ionian Sea and to deal with the Illyrians causing trouble on Epirus and in the region more generally.Footnote 44 Co-operation between Dionysios and the Parians could very well offer a context for the new decree, in which the Parian dēmos appears to organize some form of service to the tyrant or make arrangements for him (perhaps after a request): it may be that, on the point of intervention against the Illyrians on Pharos, Dionysios expected some kind of support from the Parians before embarking on an expedition against the Illyrians on Pharos. Alternatively (or additionally), he may have demanded it (or the Parians offered it) in the aftermath of his intervention in return for his help in resisting the Illyrian attack. In the period from 384 to 379, Dionysios’ expansion in the Adriatic area stalled as he faced challenges in Sicily and Italy;Footnote 45 but his dispatch of ships to Corcyra in 372 suggests that his interests there continued in the 370s (Xen. Hell. 6.2.33–6; Diod. Sic. 15.47.7).Footnote 46 In the early 360s he dispatched troops to the Peloponnese (Xen. Hell. 7.1.20–2, 27–32; Diod. Sic. 15.70.1). It is possible to envisage, therefore, that he may have sought or received Parian service at any point during or after the colonization of Pharos; as already noted, his death in 367 forms a terminus ante quem for the new decree.

So far we have suggested that this decree indicates some kind of mutual (or reciprocal) activity between the Parians and Dionysios, perhaps related to settlement in the Adriatic, probably in the second half of the 380s BCE or some years later. These shared interests in the Adriatic and the collaboration between the Parians and Dionysios in the settlement of Pharos, as suggested by some of our sources, is but one aspect of a perhaps more complex relationship between the tyrant and the islanders. We must consider the domestic Parian context, too.

We do not know much about Paros in the early fourth century, and indeed it is not possible to establish with certainty the form of constitutional organization on the island.Footnote 47 Scholarship on the Parian political situation has envisaged upheaval on the island at various points during the first three decades of the fourth century BCE.Footnote 48 Isocrates’ Aeginetikos speech, dated to the late 390s,Footnote 49 makes reference to an otherwise unattested man, Pasinos, who is said to have taken Paros ‘long ago’ and seized property there (Isoc. 19.18); the events described in that passage are difficult to date, but would have taken place during the lifetime of the speaker; it is likely that he established a tyranny or oligarchy on the island.Footnote 50 Democracy was probably re-established shortly afterwards: Plato’s Menexenos (245b) makes reference to Athenian intervention on Paros probably around 393 BCE.Footnote 51 Eugenio Lanzillotta and Branko Kirigin hypothesize that there was stasis on Paros after the King’s Peace of 387 BCE and that in its aftermath the Parians were led by an oligarchic government with ‘Pythagorean’ interests with close ties to Dionysios and Sicily.Footnote 52 Such a ‘Pythagorean’ link may be exaggerated, but stasis on Paros fits rather tidily with Diodorus’ attestation of the Parians’ association with Dionysios in the mid-380s at the time of the settlement of Pharos. Yet this oligarchic regime may not have lasted long: the Parians appear to have joined the Second Athenian Confederacy in 377/6, and a democratic government seems to have operated on Paros at some point in the fourth century.Footnote 53

We have further information on a probable stasis on Paros in the early fourth century. An Athenian inscription (RO 29) recording an Athenian decree (ll. 1–14) and a decision of the Athenian allies of 373/2 (ll. 14–23) refers to a reconciliation between warring parties on Paros. The decree is perhaps best known for setting out the regulations about sending a cow and panoply to the Panathenaia and a cow and a phallus to the Dionysia, in accordance with the status of Parians as Athenian ‘colonists’ (apoikoi).Footnote 54 The decision of the sunedrion of Athenian allies takes measures so that ‘the Parians shall live in agreement and nothing violent shall happen’,Footnote 55 before decreeing procedures related to deaths and possibly exiles in the community. The substance of the allies’ decision implies a background of acute crisis within Paros, with a resolution making provisions that such a situation should not be repeated in the future. This strife has traditionally been interpreted as taking place between pro- and anti-Athenian parties:Footnote 56 Hans-Joachim Gehrke takes the view that the Parians had left the Athenian Confederacy during a period of pro-Spartan government and that the Athenian decree and decision of the allies marked their rejoining of it.Footnote 57 Martin Dreher suggested, instead, that the reconciliation implied in this inscription must have been between factions of Parians rather than between the Parians and Athenians.Footnote 58 Indeed, the language, and specifically the clause about exiles, resembles that of decrees related to internal reconciliation; it is, therefore, most likely that this reflects the end of a period of internal strife.

Would a situation of acute civil strife explain the settlement on Pharos? Establishing settlements overseas was often a solution or response to internal strife. While it is not possible to establish the political affiliations of the settlers of Pharos in relation to the Parian strife, nor whether the settlement itself was a direct result of strife on Paros, it is likely that the political situation on Paros led directly or indirectly to the departure of a significant portion of that community for a settlement overseas. The relatively small population of Pharos occupying a relatively large area seems to imply that the settlers were probably wealthy.Footnote 59 Whether that makes them pro-oligarchy or indeed anti-Athenian is far more difficult to establish.Footnote 60 We suggest, therefore, that the settlement of Pharos was related, perhaps indirectly, to an internal stasis on Paros.

An acute period of civil strife could further enable us to understand the historical context for our decree. We might envisage that the enactment of a decree pledging to ‘serve’ or ‘take care of [something] for’ Dionysios expressed anti-Athenian sentiment, perhaps in the 380s or 370s. We know that Dionysios had been an ally of the Spartans against the Athenians for much of the period between the late 390s and the early 360s.Footnote 61 One view, therefore, is that rivalry between the Athenians and Dionysios of Syracuse was being played out in terms of influence over, or co-operation with, the Parians. It might even be the case, if the settlement of Pharos is relevant to the decree published here, that Parian settlers were fleeing upheaval. The assistance given to the Parians by Dionysios in the establishment of the settlement implies that the settlers were not pro-Athenian. Internal strife, as well as other reasons, such as an interest in getting a foothold in the Adriatic, created the necessary context for the Parians to settle Pharos. Dionysios’ aligned interests in the region, as well as a possible anti-Athenian stance, resulted in his offer of assistance to the settlement process. Our decree seems to belong to the same context of regional interests in the Adriatic, as well as anti-Athenian politics that played out on Paros in the first decades of the fourth century and until Paros joined the Second Athenian Confederacy in 377.

Finally, our new document might tentatively be held in support of Federica Cibin’s restoration of a Pharian inscribed decree of probably the late third century BCE.Footnote 62 In that text, the Pharians appeal to both the Parians and another community as their sungeneis, to help them in the rebuilding of their city after the Illyrian Wars (SEG 23.489a ll. 11–16; cf. Curty 37).Footnote 63 Cibin’s restoration of the text (reported in SEG 41.545[2]) revises that of l. 12:

Be it resolved by the dēmos to send out

three ambassadors to the Parians and their

sungeneis of the city the Syracusans.

If Cibin’s restoration of the text is correct (and it has been challenged by Alessandra Coppola),Footnote 64 then the Pharians sent three ambassadors to both the Parians and the Syracusans (as the Parians’ sungeneis); the ‘memory’ of the co-operation between the Parians and the Syracusans, therefore, was invoked some 150 years after its supposed establishment. Our decree shines new light upon the historical developments and the interaction between the Parians and Dionysios that lay behind the third-century memory of that event.

III. Conclusion

This new discovery offers the first contemporary evidence for Parian co-operation with Dionysiοs, and may relate to the dispatch of settlements to the Adriatic area in the early fourth century BCE. It indicates that the Sicilian tyrant’s networks of interaction extended as far as the Cyclades during this period. We have placed the decree in the context of the Parian settlement of Pharos and of the history of internal dispute on Paros in the early fourth century. The decree enhances our understanding of Parian involvement in the Adriatic, and showcases how political (and perhaps even military) alliances were forged as a result of regionally converging interests, in this case those of Paros and of Dionysios.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Polly Low for valuable comments on this article and the two anonymous readers for JHS for their helpful critical feedback.

Abbreviations

- AIO:

-

Attic Inscriptions Online, https://www.atticinscriptions.com/

- Curty:

-

Curty, O. (1995) Les parentés légendaires entre cités grecques: catalogue raisonné des inscriptions contenant le terme ‘syngeneia’ et analyse critique (Geneva)

- DVC:

-

Dakaris, S., Vokotopoulou, I. and Christidi, A.F. (2013) Τα χρηστήρια ϵλάσματα της Δωδώνης των ανασκαφών Δ. ευαγγϵλίδη (2 vols) (Athens)

- LOD:

-

Lhôte, E. (2006) Les lamelles oraculaires de Dodone (Geneva)