Introduction: Landscape and Memory

Memory practices connected medieval sacred landscapes to embodied religious experience: monasteries were active in creating ritual landscapes as religious imaginaries, interweaving materiality, myth and hagiography. This chapter reviews recent approaches to the study of place and memory in the monastic landscape, before considering the biography of Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset) in detail. Physical space is transformed into social place through an ‘organised world of meaning’, combining topographical characteristics and physical features with the investment of social memory and individual experience (Tuan Reference Tuan2005: 179). A ‘sense of place’ develops through engagement with a landscape over time, connecting space with remembrance and emotional attachment to a specific locality (Feld and Basso Reference Feld and Basso1996). Medieval monasteries were spiritual centres for 500 years or more – for nearly a millennium, in the case of early medieval foundations like Iona, Whithorn and Glastonbury. The Dissolution was not an abrupt end to these deeply-held beliefs, but rather a long process of renegotiating the meanings of medieval religious landscapes and their value to early modern communities. Monastic memory was reworked to serve post-Reformation narratives that operated at both local and national scales. Former monastic landscapes became contested spaces, with opposing creeds competing to control sacred heritage (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 10). Social memory is based around collective ideas about the past: it is often used to legitimate authority and to reinforce the shared identity of communities. Ideological narratives around sacred heritage can also be used to emphasise differences between groups, serving as a tool of resistance or a weapon of conflict through the deliberate destruction of memory as an act of war or genocide (Bevan Reference Bevan2016).

Archaeological approaches to memory have focused principally on the ‘uses of the past in the past’, in other words, how ancient landscapes were invented, imagined and reimagined by successive generations (e.g. Borić Reference Borić2010; Van Dyke and Alcock Reference Van Dyke and Alcock2008). This approach is exemplified by Richard Bradley’s study of the use of the past in prehistory (Bradley Reference Bradley2002) and Sarah Semple’s examination of the Anglo-Saxon reuse of prehistoric ritual landscapes (Semple Reference Semple2013). In contrast, historical (post-medieval) archaeologists have focused particularly on memory in relation to contested landscapes such as battlefields, and on broader landscapes of conflict and loss, such as those associated with the Highland Clearances (Horning et al. 2015; Jones Reference Jones2012). There has been a strong emphasis in historical archaeology on the critical assessment and disruption of dominant narratives, to give voice to subaltern groups who were silenced by displacement, slavery and war (Orser Reference Orser2010). These approaches highlight power relations and representation in memory practices but generally neglect the role of landscape and memory in negotiating changes in religious belief and attitudes towards the dead (Holtorf and Williams Reference Holtorf, Williams, Hicks and Beaudry2006). These questions are particularly relevant to medieval and post-medieval religious transitions, such as the impact of Norman colonisation on Anglo-Saxon monasticism and the shift from Celtic to reformed monasticism in twelfth-century Scotland (see Chapter 2). The Dissolution is especially significant in terms of memorial practices and the multiple meanings that were projected on the ‘bare ruined quires’ of former monasteries. Dissolution landscapes can also be perceived in terms of conflict and collective loss: monastic ruins held particular fascination for early antiquaries, perhaps because of their shared sense of the deep culture shock of the Dissolution (Aston Reference Aston1973). Ruined monasteries served as mnemonic prompts but they also possessed active spiritual and political agency. Sacred heritage often serves an ideological purpose, stressing continuity or discontinuity, and harnessing material evidence to reinforce the authority of a particular version of the past (see Chapter 6).

Monastic ‘Biographies’

Monastic landscape archaeology has been dominated by economic approaches, focusing on discrete elements of technology and land management such as fisheries, milling and grange farming (e.g. Bond Reference Bond2004; Götlind Reference Götlind1993). However, recent work has examined two distinct aspects of place and memory in the monastic landscape. The first strand considers how medieval monastic communities actively shaped landscapes to forge collective institutional memories; the second addresses the memorialisation and reuse of monastic landscapes by post-Reformation communities. An excellent study of the monastic construction of memory is Paul Everson and David Stocker’s analysis of the Premonstratensian landscape of Barlings in the Witham Valley of Lincolnshire (Everson and Stocker Reference Everson and Stocker2011). They reject the functionalist approaches that dominate monastic landscape archaeology, typically comprising the cataloguing of separate components of the estate identified by documentary sources. Instead, they integrate economic, symbolic and ritual perspectives on the landscape in order to explore the social construction of ‘place’ rather than ‘space’. They consider how the Barlings monastic landscape related to the ritual landscapes that came before and after it. Their approach was prompted by the special character of the Witham Valley, which was the focus for the ritual deposition of weapons from the Bronze Age, right through monastic occupation, and up to the early modern period (Stocker and Everson Reference Stocker, Everson and Carver2003). Their theoretical framework is informed equally by post-processual approaches and Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC), a methodology developed as a tool for the management and planning of the modern landscape. HLC evaluates landscape morphology and character by compiling evidence such as historic maps, aerial photography and satellite imagery. This essentially morphological approach can be used alongside a more nuanced process of interpretation to consider how landscapes are shaped by power, belief and identity (for debates on HLC see: Austin and Stamper Reference Austin and Stamper2006; Rippon Reference Rippon2013).

Studies of monastic landscapes have moved towards a ‘biographical’ approach to consider long-term developments following the Dissolution. For example, in their study of Cluniac Monk Bretton in South Yorkshire, Hugh Willmott and Alan Bryson frame the Dissolution as the starting point for the creation of new and evolving roles for former monastic landscapes. They are critical of previous approaches that emphasise the Dissolution as the final event in the lifecycle of a monastery, drawing a sharp division between religious and secular phases (Willmott and Bryson Reference Willmott and Bryson2013). They focus on the micro-history of a single monastery which they describe as ‘fairly unremarkable’, reminding us that even minor monastic houses continued to reverberate on local landscape and memory. This point is demonstrated in David Austin’s research on the Cistercian monastery of Strata Florida in Wales. Austin explores the significance of former monasteries in structuring local biographies of place and he also situates these local stories within a national perspective. He contrasts dominant national narratives of triumphal Protestantism with local themes and specific biographies of place. These local stories might include continuity in ritual practices, such as the use of holy wells and patterns of burial; local sentiments surrounding mortality and loss at the Dissolution; and political feelings associated with religious dissent (Austin Reference Austin, Burton and Stöber2013: 4). In Austin’s study of Strata Florida, the writing of biography involves reconstructing the landscape from prehistory to the present day, to consider both the world that the monks inherited and the legacy that they left embedded in the landscape (Austin Reference Austin, Burton and Stöber2013: 11).

Monastic ruins continued to shape local and national stories into the modern period. In the first half of the nineteenth century they were integral to Romanticism, viewed by artists, writers and poets as a corrective to industrialisation and emblematic of the medieval ‘Golden Age’. Some were used as symbols of national identity; for example, the Cistercian Abbey of Villers (Belgium) had been suppressed and sold by the French in 1796. From 1830, it became an important symbol of the independent nation state of Belgium; its controversial restoration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was highly politicised and connected with the promotion of Catholic identity (Coomans Reference Coomans2005). In Britain, abbeys were used to bolster local identity and civic pride in the face of growing urbanisation and industrialisation. For example, the well-preserved ruins of Kirkstall Abbey in Leeds were developed as an amenity space in the 1880s, attracting tourism and artistic responses in the form of painting and poetry (Dellheim Reference Dellheim1982). The ruins of Reading Abbey (Berkshire) were incorporated into the Forbury Pleasure Gardens from 1856, connected by a tunnel to the garden, where some of the abbey’s carved stones were reused in gothic follies. At the turn of the twentieth century, a Reading doctor and antiquary, Jamieson Boyd Hurry (1857–1930), encouraged civic pride by commissioning a series of ten oil paintings depicting Reading Abbey’s most illustrious moments (Baxter Reference Baxter2016: 163). At the national level, concern for the conservation of medieval abbeys was key to the preservation ethic that fuelled the development of ancient monuments legislation in England (Emerick Reference Emerick2014: 42). The protection of England’s medieval abbeys was regarded as an urgent priority in the first decades of the twentieth century: many monastic ruins were in danger of collapse, while others were at risk from wealthy American collectors who dismantled medieval buildings and shipped them to the United States as cultural booty (Emerick Reference Emerick2014: 72–5).

These biographical perspectives situate monastic archaeology within wider theoretical debates on landscape and memory, exploring themes of identity and cohesion, appropriation and legitimation, and contested and alternative readings of landscapes (e.g. Holtorf and Williams Reference Holtorf, Williams, Hicks and Beaudry2006). Historical studies of religious belief have also shifted towards long-term perspectives on landscape and memory. The contribution of Alexandra Walsham has been especially ground-breaking, tracing the broad canvass of changing perceptions of the landscape and the natural world at the Reformation and how relics of pre-Reformation belief structured new myths that transformed social memory (Walsham Reference Walsham2004, Reference Walsham2011, Reference Walsham2012).

Monastic Memory Practices

How were material and embodied practices used to imprint monastic memory on the landscape? Monks were the memory specialists of the medieval world – they developed cognitive memory training, were ritual experts in commemorating the dead and designed architecture to monumentalise the Christian past. Monastic memory was ‘locational’, prompted by specific places and topographical markers, with architecture and landscape serving a cognitive purpose. Mary Carruthers has described monastic meditation as a form of ‘craft knowledge’, learned through imitation and practice, and prompted by constant recollection and memory (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2000). It followed the Roman tradition of rhetoric and drew upon mental images such as architecture in order to stimulate memory (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2000: 16). But monastic memory practices were not merely rhetorical, they were deeply material, performative and ‘procedural’ (Mohan and Warnier Reference Mohan and Warnier2017). This point can be further elucidated with reference to Paul Connerton’s classic study of memory and identity formation (Connerton Reference Connerton1989). Connerton was interested in how identity and memory were created through three types of bodily techniques or performance – calendrical, verbal and gestural. He proposed that the impact of these performances could be extended in time and space through memory practices that he distinguished as ‘inscription’ and ‘incorporation’ (Connerton Reference Connerton1989: 72–3). Practices of inscription include writing and other forms of recording which trap and hold ritual information. For example, inscription could include practices of naming, such as the dedication of monasteries to specific saints and the naming of places in the landscape. Naming is an active process in place-making: local stories are imprinted on physical terrain through names that fix collective memory in the landscape (Gardiner Reference Gardiner, Jones and Semple2012). Practices of incorporation are more procedural and transient, and would include monastic liturgy and meditation, as well as ritual acts performed by the laity, such as grave-side rituals or pilgrimage to holy wells.

A key element of inscription was the writing of monastic chronicles and foundation narratives. It was not uncommon for these to be written over several generations: they represent a palimpsest of collective memory and often connected the identity of a monastic community to its founding saint and local topography. For example, the history of Selby Abbey in North Yorkshire, completed in 1174, claimed that its origins were divinely inspired by visions of St Germanus: the saint appeared to a monk in the French abbey of Auxerre and told him to travel to Selby to build an abbey in the saint’s honour (Burton with Lockyer Reference Burton and Lockyer2013). Selby’s foundation legend claims that the monk Benedict left France to travel to Yorkshire in 1067, at the height of the uprising by the northern earls against William the Conqueror. He carried a relic of St Germain’s finger in a golden box, a material vestige that connected Selby’s origin story to the landscape of Auxerre. David Harvey describes monastic hagiography as ‘profoundly geographical’, a means of binding together real and imagined landscapes in order to create a sense of place and to shape collective memory (Harvey Reference Harvey2002). He argues that hagiography represents a selected version of monastic heritage that stressed continuity with a specific past; in other words, a carefully controlled and authoritative message of how a particular monastery or religious order wished its origins and allegiances to be perceived.

Dedications to saints represent a major source for investigating local memory, identity and patronage in the medieval landscape. Recent research has reassessed the religious landscape of medieval Scotland through dedications and place names. The evidence for Scottish saints’ dedications has been critically assessed in a wider European context, demonstrating that devotion to insular saints such as Ninian, Kentigern and Columba was not incompatible with universal cults such as the Virgin Mary and English saints including Thomas Becket (Boardman and Williamson Reference Boardman and Williamson2010). Place name evidence can be used to investigate how the cults of early medieval saints were perpetuated in the later Middle Ages. However, Thomas Clancy reminds us that place names are not ‘fossil records of cult and church development’; instead, they are a vital source of evidence for the cult and ‘afterlife’ of a saint (Clancy Reference Clancy, Boardman and Williamson2010: 3). For example, he notes that most dedications to the fifth-century St Ninian actually post-date the twelfth century, coinciding with the period when Scottish clergy had increased access to Bede to inform their knowledge of Ninian’s life (Clancy Reference Clancy, Boardman and Williamson2010: 8). Matthew Hammond has considered the dedications of Scottish monasteries in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, which demonstrate a strong current of support for universal cults such the Virgin Mary and the Holy Trinity. He suggests that aristocratic foundations were more likely to favour insular saints while royal foundations supported universal saints. It has previously been argued that the popularity of insular Scottish saints in the later Middle Ages represents a ‘nationalist’ or anti-English sentiment (McRoberts Reference McRoberts1968). David Ditchburn argues that their popularity is instead consistent with a wider trend common throughout Western Europe for devotion to local cults and their landscapes (Ditchburn Reference Ditchburn, Boardman and Williamson2010).

Choices in architectural form and style were also active in constructing social memory. The iconographical form of a building was used to signal sacred archetypes and religious allegiances. For example, the cylindrical piers in the nave at Dunfermline Abbey (Fife) have spiral and zigzag patterns that may have marked the location of the nave altar and possibly the original burial place of St Margaret (Figure 5.1). They are also part of a wider pattern in which spiral piers were used to highlight important locations at major churches in the late eleventh century, including Canterbury Cathedral crypt (begun 1096) and the nave altar at Durham Cathedral (begun 1093). Dunfermline was founded in 1070 by Queen Margaret to celebrate her marriage to Malcolm I. The abbey had close connections with both Canterbury and Durham: the first monks were sent to Dunfermline from Canterbury by Archbishop Lanfranc to establish the first Benedictine community in Scotland; Turgot (d. 1115), the prior of Durham, was Margaret’s confessor and hagiographer, and was later appointed bishop of St Andrews (Bartlett Reference Bartlett2003: xxix). Richard Fawcett dates the piers to after 1128 and suggests that the master mason may have come from Durham (Fawcett Reference Fawcett2002: 165). In addition to signalling alliance to Benedictine Durham and Canterbury, the piers may have provided an iconographic reference to Old St Peter’s in Rome. Eric Fernie has argued that spiral piers represented the ancient columns that marked the apse of the fourth-century basilica in Rome (Fernie Reference Fernie, Coldstream and Draper1980), a reference that would have emphasised the close link to the Roman church that Margaret and her sons promoted (see Chapter 2).

In his study of English Benedictine architecture, Julian Luxford emphasised the importance that the Benedictines placed on demonstrating the ancient origins of individual monasteries. This included the deliberate retention of Saxon fabric in twelfth-century programmes of rebuilding at the West Country churches of Winchester, Malmesbury (Wiltshire), Tewkesbury (Gloucestershire) and Gloucester (Luxford Reference Luxford2005: 145–7). The practice continued into the later Middle Ages at Glastonbury Abbey, where twelfth-century fabric was re-incorporated in the choir extension dating to the mid-fourteenth century (Sampson Reference Sampson, Gilchrist and Green2015) and durable blue glass dating to the twelfth century was integrated in sixteenth-century glazing schemes (Graves Reference Graves, Gilchrist and Green2015) (Figure 5.2). These incorporations may have been intended to reference the abbey’s florescence under Abbot Henry of Blois, grandson of William I, nephew of Henry I and brother of King Stephen. Henry remodelled Glastonbury and commissioned sculpture that placed the abbey in the artistic context of European court culture. The Cistercians of northern England also used archaic style in architecture, manuscripts and material culture to bolster Cistercian identity and privileges in the later Middle Ages (Carter Reference Carter2015b). Archaic style was used more widely in ecclesiastical architecture to convey a sense of antiquity and to legitimate selected, authoritative messages of monastic heritage. For instance, the friars harnessed the ideological potential of architecture to signal their commitment to monastic reform and their return to the apostolic origins of monasticism. An example is Santa Maria in Aracoeli in Rome, where a late thirteenth-century nave was created with columns and round arches to mimic the appearance of an early Christian basilica (Bruzelius Reference Bruzelius2014: 189). The political use of archaic style can also be found in later medieval Scotland: Ian Campbell has suggested that Romanesque style was re-adopted in Scottish churches in the fifteenth century to evoke the ‘Golden Age’ of the Canmore dynasty (Campbell Reference Campbell1995). Round arches and cylindrical piers were incorporated in the rebuilding of Melrose Abbey (Scottish Borders), Dunkeld Cathedral (Perth and Kinross), St Machar’s in Haddington (East Lothian) and the Church of the Holy Rood at Stirling.

5.2 Durable blue glass from Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset) dated to the 12th century.

Memory and the Reformation: Remembering and Forgetting

Studies of the Reformation by historians including Andrew Spicer and Alexandra Walsham have highlighted complexities and contradictions in the treatment of sacred space and landscapes (Spicer Reference Spicer, Coster and Spicer2005; Walsham Reference Walsham2011). These tensions are particularly evident in Scotland’s ‘long Reformation’, which was an extended process that began twenty years after the final suppression of monastic houses in England, Wales and Ireland. The Scottish Reformation was launched in 1560 with ‘rage and furie’, when the preaching of John Knox inspired the lords of the Congregation and their followers to wreak havoc on monasteries and churches in the north and east of Scotland. It took just two days to gut the Carthusian, Dominican and Franciscan monasteries in Perth; and at St Andrews (Fife), the iconoclasts destroyed monastic gardens and orchards as well as religious buildings, statues and shrines (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 100). The urban friaries were the main target for the reformers, with around half sacked and burnt (Randla Reference Randla and Sarnowsky1999). However, the majority of Scottish monasteries were never formally suppressed. Although churches were cleansed of Catholic fittings, many monks and nuns were allowed to live out their lives peacefully in the monastic cloister for decades after the suppression (Fawcett Reference Fawcett1994a: 120). Excavations at the sites of former monasteries such as Dundrennan (Dumfries and Galloway) confirm that limited occupation continued in the cloister up to c.1600 (Ewart Reference Ewart2001: 31).

In contrast, the typical treatment of English monasteries at the Dissolution involved the immediate demolition of the church, chapter house and cloister. This targeted the overtly sacred space of the church; the chapter house as the site of institutional memory; and the domestic space of the dormitory, to ensure that former monks and nuns could not re-occupy the ruins (Howard Reference Howard, Gaimster and Gilchrist2003). There were deliberate attempts to conceal religious artefacts in the grounds of monasteries, suggesting that monastic communities may have anticipated their eventual reinstatement: concealed sculptures have been recorded at Cistercian abbeys including Fountains, Byland (North Yorkshire) and Hailes (Gloucestershire) (Carter Reference Carter2015a). The buildings most likely to be retained at the Dissolution were the gatehouse and the abbot’s or prior’s lodgings: these self-contained chambers suited conversion to new courtier houses and domestic uses (Phillpots Reference Phillpots, Gaimster and Gilchrist2003). The comparatively gentle treatment of many monastic sites in Scotland may suggest that by 1560 they were already regarded as having been secularised. At some Scottish monasteries, the monks were allowed to live in individual houses outside the monastic cloister. For example, the monks of Pittenweem (Fife) had small houses in the priory garden, and at Crossraguel (South Ayrshire) a series of small houses survives along the perimeter wall of the inner court to the south of the cloister, possibly private residences for monks (Fawcett Reference Fawcett1994b: 109). The final phase of monastic Scotland saw the introduction of commendators, lay administrators appointed by the king, a system unknown in England but more common in Europe. These men built large mansions in monastic precincts, some of which were converted at the Reformation, such as the surviving example at Melrose, rebuilt at the end of the sixteenth century.

Paradoxically, the Scottish Dissolution combined localised, ruthless iconoclasm with a remarkably tolerant attitude towards the majority of former monasteries and their inhabitants. I would like to explore this contradiction through brief consideration of two specific material practices: the continued use of dissolved monastic sites for burial and the sustained use of holy wells for popular ritual use. There is archaeological evidence to confirm that monastic cemeteries in the west and north of Britain continued to be used for burial after the Dissolution. For example, excavations at Carmarthen Greyfriars revealed at least five graves to the north of the choir, cut through demolition deposits of the friary (James Reference James1997: 191). Burial continued at the Carmelite Friaries of Aberdeen, Linlithgow and Perth well into the seventeenth century: at Linlithgow, there were six infant burials interred in the nave and chancel in the late sixteenth to seventeenth century (Stones Reference Stones1989). At Inchmarnock (Argyll and Bute), the disused church continued as a burial ground in the sixteenth to seventeenth century, with the graves of perinatal infants dug into the ruined nave (Lowe Reference Lowe2008: 90–1). This pattern of reuse extended to disused parish churches and chapels. At Auldhame (East Lothian), an infant burial was inserted into the decayed west gable wall of the chapel, which had been abandoned around 1400 and left to tumble down and decay (Crone et al. Reference Crone, Hindmarch and Woolf2016: 51). A similar case was recorded at the disused chapel on St Ninian’s Isle (Shetland), where a neonate was interred close to the chancel wall (Barrowman Reference Barrowman2011). The sites of former monasteries were sometimes used for the burial of Catholics (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 181) but the archaeological evidence suggests a more select pattern of social use. At Aberdeen, Linlithgow, Perth and Inchmarnock, a high proportion of the post-Reformation burials are those of women and children (Stones Reference Stones1989: 111, 42, 44, 114). Burial of children continued on the sites of some former Irish monasteries up to the nineteenth century (Hamlin and Brannon Reference Hamlin, Brannon, Gaimster and Gilchrist2003), and on Iona (Scottish Inner Hebrides), women and children were interred at the site of the nunnery into the eighteenth century (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan1994). Post-medieval burials at Iona continued the traditional rite of placing quartz pebbles with the corpse (see Chapter 4). Similar practices took place at former parish churches: excavation at the burial aisle established in the sixteenth century at Auldhame suggests that the site was reserved for the burial of juveniles, and that the rite of placing quartz pebbles continued into the post-medieval period (Crone et al. Reference Crone, Hindmarch and Woolf2016: 52). Continuity of burial within suppressed churches and monasteries is a clear expression of the sustained belief in the sanctity of a consecrated site, despite repeated attempts by the Kirk to outlaw the custom (Spicer Reference Spicer, Gordon and Marshall2000; Reference Spicer, Coster and Spicer2005: 89).

Following the Reformation, people continued to visit sacred natural locations in the landscape such as springs, wells and trees. In Ireland, ruined monasteries remained significant places of pilgrimage, with some friaries in the west of Ireland continuing to operate well into the seventeenth century (Harbison Reference Harbison1991: 111–36; Moss Reference Moss2008: 70). Pilgrims gathered at holy sites to perform the same embodied acts that they had rehearsed throughout the Middle Ages (Bugslag Reference Bugslag, Bowers and Keyser2016), including circumambulation in the direction of the sun, sprinkling of water over infants and leaving offerings of scraps of cloth, pins and coins (Walsham Reference Walsham2012). Pilgrims also gathered stones and created cairns at Scottish sites including St Fillan’s Well (Stirling) (Donoho Reference Donoho2014) (Figure 5.3), much as they had done at early medieval pilgrimage sites such as Iona and the Isle of May (Fife) (Yeoman Reference Yeoman1999). The intensity of interest in these sites led to legislation by the Scottish Parliament in 1581, prohibiting pilgrimage to chapels and springs to perform illicit devotions. Heavy fines were imposed for the first offence and death for the second, although most found guilty of this offence were instead ordered to perform humiliating acts of public penance (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 106). Legislation against such practices continued into the seventeenth century; nevertheless, rites of healing and pilgrimage continued at hundreds of sites throughout Scotland for centuries after the Reformation (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 171; Donoho Reference Donoho2014). While some kirk sessions were determined to stamp out superstitious practices, many others were tolerant of pilgrimage to sacred sites in the landscape (Todd Reference Todd2000). In Ireland, devotion at crosses and holy wells intensified in the seventeenth century, with the construction of new well-houses that incorporated Romanesque carvings taken from ruined churches and monasteries. These carvings may have been selected for their association with particular saints and sacred places, rather than for their style or antiquity (Moss Reference Moss2008: 75).

5.3 St Fillan’s Holy Well (Stirling).

Women and children seem to have been closely connected with rites at holy wells, mirroring the pattern noted above for the continued use of monastic cemeteries after the Reformation for the burial of women and children. This may signal some degree of continuity with earlier practice: the dedications of medieval holy wells are predominantly to the Virgin Mary and female saints including Bridget, perhaps indicating a female preference for devotion at holy wells (Clancy Reference Clancy2013: 31). It is also striking that the objects left at holy wells and springs – such as coins, pins and headlaces (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 107, 171, 457) – were similar to those placed with the medieval dead. Where pins and lace ends have been found in medieval graves, for example in association with children’s graves at Linlithgow Carmelite Friary, they have been explained as shroud fixings (Standley Reference Standley2013: 106). Pins continued to be used as offerings at wells throughout Britain into the nineteenth century, often bent before they were deposited, just as medieval pilgrims crumpled their badges before throwing them into rivers (Merrifield Reference Merrifield1987: 112). The sustained use of such objects as offerings at holy wells suggests that even the most mundane objects found in medieval graves may have been placed with ritual intent.

This brief overview of two rites in the post-Reformation landscape questions two prevailing assumptions about early Protestantism: first, that it was intrinsically antagonistic to ritual and second, that it rejected the concept of sacred space. The idea that supernatural power was invested in sacred places remained an important element of popular Protestant religion (Walsham Reference Walsham2011; Spicer Reference Spicer, Coster and Spicer2005), compelling burial at former monasteries and continued rites of pilgrimage in the landscape.

Myth and Memory: Arthur and Arimathea at Glastonbury Abbey

I will turn now to Glastonbury Abbey, an iconic landscape where myth has played a unique role in connecting the medieval monastery to broader discourses surrounding English cultural identity. In addition to its reputed association with King Arthur, the abbey cultivated an origin story to proclaim its historical and spiritual pre-eminence among English monasteries. The history, archaeology and ethnography of Glastonbury are complex and still evolving, particularly in relation to New Age re-imaginings of its past, a theme that will be picked up in the final chapter. The well-documented case of Glastonbury vividly demonstrates how material practices were employed by medieval monastic and later Protestant communities to fix religious memory in the landscape. I will focus here on two key narratives in the medieval abbey’s biography: its beginning and ending and how these stories were re-imagined by subsequent generations. Detailed archaeological appraisal of Glastonbury Abbey can be consulted in a publication that reassesses thirty-six seasons of antiquarian excavations that were conducted at the site throughout the twentieth century (Gilchrist and Green Reference Gilchrist and Green2015).

Memory practice documented at Glastonbury begins with the origin story that was recorded in the tenth century and further embellished from the twelfth century onwards. A series of accumulated tales linked Glastonbury Abbey to biblical and apocryphal characters and ultimately to the life of Christ. As was common elsewhere, Glastonbury’s monastic heritage was projected through the medium of hagiography and the writing of chronicles. The abbey promoted its association with St Dunstan, abbot of Glastonbury 940–57 CE and later archbishop of Canterbury, who played a pivotal role in the reform of Benedictine monasticism in the tenth century (Brooks Reference Brooks, Ramsay, Sparks and Brown1992). The Life of St Dunstan was written c.995 CE by a monk known only as ‘B’, drawing on his earlier memories of the community from around the mid-tenth century. As well as recounting Dunstan’s life, the vita places the abbey in its social and topographical context; it refers to the buildings constructed by Dunstan and presents Glastonbury in the tenth century as a place of great learning. It describes an ancient church, the vetusta ecclesia, and attributes its construction to divine agency: ‘For it was in this island that, by God’s guidance, the first novices of the catholic law discovered an ancient church, not built or dedicated to the memory of man’ (Winterbottom and Lapidge Reference Winterbottom and Lapidge2012: 13).

This narrative was further developed two centuries later by the respected historian William of Malmesbury, a monk of St Albans Abbey, in his history of Glastonbury Abbey, dated 1129–30 and commissioned by Henry of Blois. The primary motivation was to prove the great antiquity and unbroken history of the monastery at Glastonbury. At the end of the eleventh century, Osbern of Canterbury had claimed that St Dunstan had been the first abbot of Glastonbury (Foot Reference Foot, Abrams and Carley1991: 163). The reputation of the monastery therefore depended on authenticating its early origin: William asserted that the monastery had been founded before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in Somerset and even hinted that Glastonbury originated in an apostolic foundation. He claimed that the ancient church had been built in the second century by missionaries sent by Pope Eleutherius in 166 CE. He cautiously noted a story that the church may have been founded even earlier, by the Disciples of Christ, and provided an eye-witness account of the ancient ‘brushwood’ church that they had allegedly constructed.

The church at Glastonbury … is the oldest of all those that I know of in England … In it are preserved the bodily remains of many saints, and there is no part of the church that is without the ashes of the blessed. The stone-paved floor, the sides of the altar, the very altar itself, above and within, are filled with relics close-packed. Deservedly indeed is the repository of so many saints said to be a heavenly shrine on earth.

The salient point in William’s account is that a timber church of some antiquity existed on the site in the early twelfth century and that it was preserved as a relic of the early monastery and its founders.

Many Christians today believe that Glastonbury’s Lady Chapel (consecrated 1186) was built on the site of this very early church, dating to the first or second century and founded by Joseph of Arimathea. Recent study of the archaeological archive has confirmed that there was indeed occupation on the site before the foundation of the Anglo-Saxon monastery. Fragments of late Roman amphorae imported from the eastern Mediterranean (LRA1) were associated with a roughly trodden floor and post-pits connected with one or more timber structures within the bounds of the early cemetery (Figure 5.4). In the southwest of Britain, this pottery occurs in contexts dating c.450–550 CE. A radiocarbon date from one of the post-pits dates the demolition of the timber building to the eighth or ninth century (Gilchrist and Green Reference Gilchrist and Green2015: 131, 385, 416). It is possible that this structure was in use for a long period extending from the pre-Saxon occupation of the site c 500 CE, into the period of the Saxon monastery, for potentially up to 300 years. This would have required cyclical repair and renewal of the timber building once in each generation – the typical use-life of Anglo-Saxon earthfast structures is estimated to be around forty years (Hamerow Reference Hamerow2012: 34–5). This new archaeological evidence does not prove the presence of an early church, but it does confirm that the Anglo-Saxon monastery was preceded by a high-status settlement dating to the fifth or sixth century. It may also suggest that the Saxon monastery ‘curated’ timber buildings that represented this antecedent community, just as the later medieval monks curated vestiges of their monastic heritage. Cycles of monument construction and reconstruction were employed by the Anglo-Saxons at secular elite complexes – such as Sutton Hoo (Suffolk) – to create social memory and forge connections to origin myths and genealogies (Williams Reference Williams2006: 161).

5.4 Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset): excavated evidence for a post-Roman timber structure and the location of LRA1 pottery, dated c.450–550 CE

Archaeological evidence for the earliest monastic occupation at Glastonbury comprises three phases of Anglo-Saxon stone churches, excavated 1926–9, when the entire width of the western area of the medieval nave was excavated. These were located to the east of the Lady Chapel and the presumed site of the old church. The churches can confidently be assigned a pre-Norman date on stratigraphic evidence: fragments of twelfth-century masonry sealed the Saxon remains. Three phases of church building were recognised on the basis of stratigraphic relationships and mortars characteristic to successive phases. The earliest phase can now be dated by radiocarbon dates associated with glass-working furnaces that provided glass for the windows of the first stone church. Bayesian analysis of the radiocarbon dates by Peter Marshall supports the proposal that the glass-making was a short-lived ‘single-event’, likely dating to the late seventh or early eighth century (Gilchrist and Green Reference Gilchrist and Green2015: 131–46). This evidence complements recent historical analysis of the charter material by Susan Kelly which confirmed that the earliest charters from Glastonbury date to the final decades of the seventh century (Kelly Reference Kelly2012).

The old timber church described by William of Malmesbury was destroyed by fire in 1184 and the medieval Lady Chapel was rapidly erected on the same site. It was consecrated in 1186, just two years after the fire, and survives largely intact today (Figure 5.5). The Lady Chapel reflects the abbey’s overall dedication to the Virgin and its strong promotion of her cult, which was strengthened by the story of a miraculous statue of the Virgin and Christ Child which survived the burning of the old church. An interpolated passage in William of Malmesbury describes how the statue was damaged: ‘Yet because of the fire heat blisters, like those on a living man, arose on its face and remained visible for a long time to all who looked, testifying to a divine miracle’ (Hopkinson-Ball Reference Hopkinson-Ball2012: 15). The spiritual significance and location of the Lady Chapel resulted in an unusual arrangement of sacred space at Glastonbury. The focal point for pilgrimage was located at the west end of the abbey church in the Lady Chapel, the site of the former old timber church. Devotion to the Virgin was also reflected in material culture excavated in the twentieth century, including a copper-alloy plaque and a foil medallion, the latter possibly from Walsingham (Courtney et al. Reference Courtney, Egan, Gilchrist, Gilchrist and Green2015: 294–5, Fig. 8.39: 7, Fig. 8.40: 9) (Figure 5.11).

5.5 The Lady Chapel at Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset) consecrated 1186.

The new Lady Chapel came to embody the collective memory and sacred heritage of the monastic community. It has been suggested that its form and decoration were deliberately archaic in order to recall Glastonbury’s antiquity, perhaps modelled to resemble a contemporary reliquary, to contain and represent the saintly relics of Glastonbury’s ancient past (Thurlby Reference Thurlby1995). Despite its late twelfth-century date, the Lady Chapel is Romanesque in its proportions and exhibits distinctively archaic elements, including round-headed windows with chevron decoration and intersecting blind arcading of round-headed arches with chevrons (Sampson Reference Sampson, Gilchrist and Green2015) (Figure 5.6). Fragments of a sumptuous scheme of painted polychromy survive on the upper parts of the internal wall faces (Sampson Reference Sampson1995). The iconography of the door carvings represents the Life of the Virgin on the north side and an unfinished cycle of the Creation on the south side. The act of rebuilding a church is another form of monastic memory practice, particularly where fabric from the predecessor is incorporated in the new build. In writing about churches in early medieval Ireland, Tomas Ó Carragáin has described the act of rebuilding as the creation of an associative relic (Ó Carragáin Reference Ó Carragáin2010: 165). A useful comparison with Glastonbury can be made with contemporary practice at Iona (see Figure 2.10), where fabric of the shrine of St Columba was incorporated into the new Benedictine complex, built c.1200 by Ranald Somhairle (Ritchie Reference Ritchie1997: 98). At both Glastonbury and Iona, relics of the early monastic community were retained to the west of the rebuilt Benedictine churches and would have served as the main ritual foci for pilgrimage.

5.6 Photograph of Glastonbury Abbey’s Lady Chapel (Somerset) showing elements in the Romanesque style: round-headed windows with chevron decoration and intersecting blind arcading of round-headed arches with chevrons.

The fire that destroyed Glastonbury’s old church in 1184 also set the scene for Glastonbury’s role in the Arthurian myth. The monks claimed the discovery in 1191 of the shared grave of Arthur and Guinevere, famously recorded by Gerald of Wales in 1193, two years after the exhumation.

Now the body of King Arthur … was found in our own days at Glastonbury, deep down in the earth and encoffined in a hollow oak between two stone pyramids … In the grave was a cross of lead, placed under a stone … I have felt the letters engraved thereon … They run as follows: “Here lies buried the renowned King Arthur, with Guinevere his second wife, in the isle of Avalon …”.

Gerald went on to explain that King Henry II had informed the monks where to dig, having received the information himself from ‘an ancient Welsh bard’. The historian Antonia Gransden argued that the monks staged a bogus exhumation in their desperate bid to attract funds to rebuild the abbey after the disastrous fire of 1184 (Gransden Reference Gransden and Carley2001). Indeed, there was reason to despair: Glastonbury had no major saint or cult of relics to attract pilgrims and they had recently lost their royal patron, Henry II, who died in 1189.

The account of Gerald of Wales described important material evidence which bolstered the monks’ claims (Figures 5.7 and 5.8). The two ‘pyramids’ flanking the alleged grave were first described by William of Malmesbury in c.1130, who noted their great age and stated that they bore carved figures and names; these ‘pyramids’ were perhaps late Saxon cross shafts. The lead cross supposedly found in the grave is highly significant: it was probably a twelfth-century forgery of an earlier item, such as the mortuary crosses found in eleventh-century graves at St Augustine’s, Canterbury (Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 90). Gerald emphasises the materiality of the lead cross and the authenticity of its message: ‘I have felt the letters engraved thereon’. The Glastonbury lead cross survived up to the seventeenth century and was published in the 1607 edition of Britannia, by the antiquary William Camden. Arthur was known to have been taken to the Isle of Avalon after being mortally wounded, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (c.1136). The lead cross associated with the exhumation of 1191 named Glastonbury as ‘the isle of Avalon’: this was the first explicit connection between Arthur’s Avalon and the Glastonbury landscape.

5.8 ‘Pyramids’ at Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset). Henry Spelman’s 17th-century reconstruction based on William of Malmesbury’s description (c.1130).

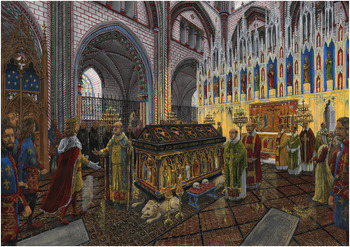

Following the exhumation in 1191, the remains of Arthur and Guinevere were translated to a tomb in the abbey church. Contemporary chroniclers of the abbey, Adam of Damerham and John of Glastonbury, confirm that this was located ‘in the choir, before the high altar’. The tomb of Arthur was placed in the most sacred space at the heart of the monastery, one reserved for burials of founders and patrons of the highest status. Julian Luxford has argued that Arthur was treated as the monastery’s founder: a Saxon royal mausoleum was created in the choir, with Arthur’s tomb flanked by those of Edmund the Elder to the north and Edmund Ironside to the south. In the later Middle Ages, Arthurian objects were displayed alongside saints’ relics on a tomb to the north of the high altar (Luxford Reference Luxford2005: 170). The cult of Arthur brought international notoriety and royal patronage to Glastonbury Abbey, including royal visits to exhume and view Arthur’s remains by Edward I in 1278 and Edward III in 1331.

Arthur’s tomb was described by the antiquary John Leland in the 1530s, shortly before the Dissolution. Philip Lindley has suggested a possible reconstruction of the appearance of the tomb based on Leland’s brief description, together with evidence in the Glastonbury chronicles and comparable examples of funerary monuments. The tomb was of black marble with four lions at its base (two at the head and two at the foot), a crucifix at the head (west) and an image of Arthur carved in relief at the foot (east). Lindley argues convincingly that the tomb described by Leland was the original monument constructed before 1200. Tomb-chests were unusual in England at the end of the twelfth century, making Arthur’s tomb one of a small number of English monuments modelled on classical sarcophagi. The form and material were deliberately archaic, selected to place Arthur in a long line of ancient Saxon kings (Lindley Reference Lindley2007). An artist’s drawing was recently commissioned to depict the choir of Glastonbury Abbey as it would have appeared in 1331 (Figure 5.9), for the visit of Edward III, based on archaeological evidence and ecclesiastical furnishings of contemporary date (see Chapter 6 for further discussion). The tomb reconstruction is inspired by Lindley’s analysis and also draws on contemporary examples such as those in Córdoba Mezquita-Catedral (Andalusia, Spain).

The legend of the old church continued to evolve in the later Middle Ages: a revision of William of Malmesbury’s history in 1247 attributed its foundation to Joseph of Arimathea (Carley Reference Carley1996). According to the Gospels, Joseph was the man who donated his own tomb for the body of Christ following the crucifixion. The Glastonbury legend claimed that Joseph had been sent to Britain from Gaul by Christ’s disciple, St Philip, together with twelve of his followers. A specific foundation date is stated for the old church as 63 CE and the dedication is noted as being in honour of the Virgin. However, the monks were not responsible for inventing the connection between Glastonbury and Arimathea. The link resulted indirectly from Glastonbury’s Arthurian story and the emergence of Arimathea in the Grail legends of French romance. Around the year 1200, the author Robert de Boron brought together a trilogy of romances featuring Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin and Perceval. Joseph of Arimathea was used as the vehicle to explain how the Grail was brought to Britain, the vessel used to collect Christ’s blood. He was cast as the guardian of the Grail and the father of English Christianity (Lyons Reference Lyons2014: 74–5).

By the mid-fourteenth century, the tradition had been established that Joseph came to Glastonbury and died there (Carley Reference Carley1996). Arimathea and the Grail were fully incorporated in the Glastonbury story by c.1340, when John of Glastonbury wrote the abbey’s chronicle. John quoted a pseudo seventh-century poem attributed to Melkin, claiming that Joseph is buried at Glastonbury and that in his sarcophagus are two cruets containing the blood and sweat of Jesus. Arimathea’s place in Glastonbury’s origin story was commemorated by an object known as the Magna Tabula, believed to date to the period of Abbot Chinnock (1382–1420). This still survives in the Bodleian Library: it is a hollow wooden box containing two hinged wooden leaves onto which parchment is pasted. It sets out the Glastonbury story from the foundation by Arimathea in 63 CE to the refurbishment of the abbey by Abbot Chinnock in 1382. Smoke stains indicate that it may have been displayed inside the church, perhaps attached to a pillar, and used to explain the sacred heritage of the site to pilgrims (Krochalis Reference Krochalis, Carley and Riddy1997).

The cult of Joseph of Arimathea was not fully developed at Glastonbury until the later Middle Ages, when the biblical association became more politically advantageous (Lagorio Reference Lagorio and Carley2001). In the fifteenth century, representation at international Church councils was based on the antiquity and precedence of ecclesiastical foundations. The significance of an apostolic foundation was enormous and material evidence was sought to verify the connection to Joseph of Arimathea. In 1419, the monks were even planning to announce the discovery at Glastonbury of the graves of Joseph and his followers, but they later retracted their claim (Carley Reference Carley and Carley2001b). The myth of Joseph of Arimathea was incorporated literally into the fabric of Glastonbury by Abbot Beere (1493–1524). He constructed a crypt chapel dedicated to Joseph beneath the east end of the Lady Chapel. The associated well of St Joseph was located to the south: the route for medieval pilgrims visiting the Chapel of St Joseph took them from the crypt to the well, via a stone passage. A brass plaque with early sixteenth-century lettering is likely to have been commissioned by Beere to explain its significance to pilgrims (Lindley Reference Lindley2007: 141; Goodall Reference Goodall1986).

Dissolution Stories: A Martyred Landscape

The events surrounding the suppression of the abbey in 1539 contributed a new narrative connected with sentiments of monastic loss and mortality. Glastonbury was one of the last monasteries to be dissolved: its enormous wealth proved irresistible to Henry VIII, valued in 1535 at £3301 17s 4d, second only to Westminster Abbey. The last abbot, Richard Whiting (1525–39), was arrested on a fabricated charge of treason in 1539 and found guilty of ‘robbery’ from his own church. He was hanged in front of the abbey gate and quartered on Glastonbury Tor, together with two of his monks, John Thorne, the treasurer, and Roger Wilfrid, one of the youngest monks. This level of violence was highly unusual: of approximately 220 Benedictine monasteries suppressed in England and Wales, only the abbots of Glastonbury, Reading and Colchester were executed. Their refusal to surrender their abbeys to the king was interpreted as a demonstration of loyalty to the Holy See of Rome.

Abbot Whiting’s death produced a monastic martyr to the Dissolution, while the manner of his execution linked monastic memory to the broader landscape. Whiting was attached to a hurdle at the abbey gate and dragged through the town and up Glastonbury Tor. A remarkably similar ritual was played out at Reading, where Abbot Hugh Farringdon was dragged through the town and executed at the gallows with two of his monks (Baxter Reference Baxter2016: 134). Abbot Whiting’s head was placed over the great gate of Glastonbury Abbey and the four quarters of his body were displayed at Wells, Ilchester, Bridgwater and near Bath (Carley Reference Carley1996: 80–3). Among its multiple meanings, Glastonbury Tor became a mnemonic for the martyrdom of Whiting (see Figure 6.13). It has been suggested that Glastonbury’s dissolution story also entered folklore through the nursery rhyme ‘Little Jack Horner’, a popular tale of opportunism. The earliest published version dates to 1735 (Opie and Opie Reference Opie and Opie1997: 234–7):

In the nineteenth century it was believed that this popular children’s rhyme had its origins in the story of Thomas Horner, steward to Abbot Richard Whiting. Folk memory suggests that Whiting sent Horner to London with a great pie for Henry VIII, which had lucrative deeds baked inside as an incentive to persuade the king not to suppress the abbey. Instead, the rhyme insinuates that Horner kept the deeds for himself, including Mells Manor, thus sealing the fate of the doomed abbey (Roberts Reference Roberts2004: 3).

Archaeological evidence suggests that Henry VIII singled out the monastic precinct at Glastonbury for special treatment at the Dissolution. It was retained by Henry until his death in 1547 and there is evidence that the buildings of Glastonbury Abbey remained intact for a decade or more after its suppression. Reading Abbey was treated similarly in this respect, as well as in the execution of its abbot: Reading’s cloister was not demolished until after Henry’s death and the site was retained subsequently for royal use (Baxter Reference Baxter2016: 141). This was in sharp contrast with the frenzy of salvage and conversion that took place at the majority of former English monasteries. Historical sources confirm that the lead was removed from the roof of Glastonbury’s chapter house in 1549 and the altars were removed from St Joseph’s Chapel in 1550 (Stout Reference Stout2012: 252). Study of the standing fabric and worked stone by Jerry Sampson has yielded evidence that the church may have been left standing and accessible after the departure of the monks. The rood beam was apparently removed from the eastern crossing piers and its sockets were repaired, implying that the work was done while the abbey church was still in use, or at least accessible to be visited (Sampson Reference Sampson, Gilchrist and Green2015).

The pattern of iconoclasm at Glastonbury may indicate that figurative sculpture was left in situ for a considerable time. The assemblage of sculpture from the abbey comprises detached heads or headless torsos, perhaps suggesting that systematic iconoclasm took place while the sculpture was still in situ. The nature of the damage is consistent with the wider pattern of iconoclasm that focused on the heads and hands of statues of the saints. Pam Graves has argued that the treatment of such images at the Reformation reveals that they were considered to have possessed conscious agency and that there was a desire to punish statues for their role in idolatry. The body parts selected for destruction – heads and hands – were the same as those targeted in cases of capital and corporal punishment. At the Reformation, these holy images were tried and held accountable for their false actions (Graves Reference Graves2008). What is exceptional in relation to Glastonbury is the chronological significance of this particular type of iconoclasm. The nature of damage caused to monasteries at the Dissolution typically comprised demolition and the salvage of stone for reuse (Morris Reference Morris, Gaimster and Gilchrist2003). The ideological attack on images did not gain momentum until the late 1540s and 1550s (Aston Reference Aston1988). The targeted attack on Glastonbury’s saints may therefore suggest that the sculpture remained in situ in the church for a decade or more after its dissolution in 1539.

We may speculate whether the continued presence of the suppressed abbey was intended to be commemorative. The historian Margaret Aston highlighted the tendency for reformers to preserve evidence of broken images and ruined churches to serve as a visual reminder of the Protestant triumph over popery and superstition (Aston Reference Aston, Gaimster and Gilchrist2003). Did Glastonbury Abbey serve as a monument to the Dissolution – was Glastonbury intended as Henry’s memento mori of the monasteries and the inevitable fate of their corruption?

Post-Reformation Narratives: Glastonbury Abbey and Protestant Nationhood

Having set out the key stories of Glastonbury’s birth and death, it remains to consider which of these narratives were remembered, forgotten or reworked in the years following the Reformation. Monastic ruins and landscapes were reshaped in the latter part of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as part of a national narrative proclaiming the triumph of Protestantism, the English state and the English economy (Austin Reference Austin, Burton and Stöber2013: 3). While memory of the Catholic monastery of Glastonbury may have been suppressed, its mythical founder-saint was harnessed in the creation of English nationhood.

Following Henry’s death in 1547, the site and demesne were granted to Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. He chose the site of the former abbey for a Protestant social experiment, establishing a colony of 230 Walloon worsted weavers, French-speaking Protestant refugees from Flanders. The intention was that the Walloons would teach the craft of weaving to the local population, to create a centre of Protestant industry at Glastonbury. The weavers constructed houses within the precinct and their leader occupied the former abbot’s lodging. In March 1552, the community comprised forty-four families and four widows; four houses were completely built and another twenty-two lacked only doors and windows (Cowell Reference Cowell1928). The historian Adam Stout has suggested that the Duke of Somerset chose Glastonbury to showcase the new Protestant religion, based on its mythical status as the ‘cradle of English Christianity’ (Stout Reference Stout2014: 81). The Walloon community fled to Frankfurt following the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary in 1553. A number of small finds dating to the sixteenth century have their closest parallels in the Low Countries and could potentially be associated with the short-lived Walloon community (Courtney et al. Reference Courtney, Egan, Gilchrist, Gilchrist and Green2015: 310). In 1556, four former monks of Glastonbury petitioned Queen Mary to restore the abbey and a legacy was made to support the work, suggesting that habitable buildings were still in place (Stout Reference Stout2014: 79). Elsewhere, former monks and nuns were also hopeful that their monasteries would be restored: monks from Monk Bretton and nuns from Kirklees (West Yorkshire) continued to live communally in new secular surroundings, while the former abbeys of Roche (South Yorkshire) and Rufford (Nottinghamshire) anticipated full reinstatement under the Catholic queen (Carter Reference Carter2015a).

Glastonbury’s Arimathea legend was exploited by Archbishop Parker, John Foxe and Queen Elizabeth I to assert the independence of the English church from Rome. Elizabeth claimed Joseph of Arimathea as ‘the first preacher of the word of God in our realm’ (Stout Reference Stout2012: 254). Joseph’s foundation of Glastonbury’s old church in 63 CE was cited as proof of the antiquity of the English church; it was argued that its distinct and reformed character had been established before 597 CE, when Augustine imposed the Roman church on Britain (Lindley Reference Lindley2007: 141; Cunningham Reference Cunningham2009). A comparison can be made here with how the Presbyterian Church of Scotland claimed the early medieval culdees as its Protestant precursor. It was argued that the ancient and native church of Scotland did not have bishops and was therefore not truly Catholic (Hammond Reference Hammond2006: 26). The Anglican Church of Ireland used a similar argument in the nineteenth century, claiming that they were the true descendants of St Patrick, because Celtic Christianity had been corrupted by the Norman imposition of Roman Catholicism in the twelfth century (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson2001: 513). In all three cases, medieval sacred heritage was pressed into service to provide spiritual authority for the Protestant church.

At Glastonbury, the material practices of dismantling the abbey ruins respected these political narratives. From his study of the standing remains of the church, Jerry Sampson has concluded that the process of destruction was controlled and systematic. The abbey buildings were used as a quarry for materials and there seems to have been a deliberate plan to create a symmetrical ruin of the church as the focal point of the site of the former abbey (Sampson Reference Sampson, Gilchrist and Green2015). The significant survival of paint fragments in the Lady Chapel suggests that it was roofed for an extended period following the Dissolution. From documentary sources, Stout has argued that the main demolition took place in the later sixteenth and early seventeenth century, when the precinct was owned by the Earls of Sussex (Stout Reference Stout2014: 79). Further destruction took place throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century, but a process of selective preservation was clearly adopted (Figure 5.10). The Lady Chapel was left largely intact and survives to the present day – the memorial to the old church and the antiquity of Glastonbury’s foundation. By 1520, it was known as St Joseph’s Chapel, and its special treatment is likely to have resulted from the importance placed on the Arimathea legend by the emerging Protestant nation. St Joseph’s Chapel at Glastonbury was regarded as a Protestant shrine, for example, described in Camden’s Britannia (1610: 226) as ‘the beginning and fountain of all religion in England’ (Stout Reference Stout2012: 256). The abbey also continued to attract Catholic recusants well into the eighteenth century, some of whom created relics from the dense ivy thicket which had enveloped the chapel (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 167).

In stark contrast, the importance of Glastonbury’s Arthurian legend diminished after the Reformation. Arthur’s tomb had been of singular importance to the monastery: when the antiquary John Leland visited in the 1530s, he accepted it as the material proof that verified the existence of King Arthur and his association with Glastonbury (Lindley Reference Lindley2007: 139). Leland was determined to prove the historical veracity of Arthur, which had recently been called into question by the Italian humanist Polydore Vergil, who had been commissioned by Henry VII to write a history of England (Higham Reference Higham2002: 236). Leland used Glastonbury Abbey and the local landscape as material proof to authenticate the Arthurian connection. He recorded that Arthur had lived at Cadbury Castle and perpetuated the folklore belief that he remained asleep under the hill (Paphitis Reference Paphitis2013: 3). The process of the Dissolution stimulated the development of antiquarian scholarship and the recording of medieval monuments, most notably by the seventeenth-century antiquary, William Dugdale (Dugdale Reference Dugdale1817–30). And yet, Arthur’s tomb disappeared from Glastonbury without trace: there is no surviving fragment and no clue to its fate. It must have been destroyed sometime after Henry’s death in 1547, when demolition of the abbey began.

The ‘pyramids’ that marked Arthur’s grave-site were treated similarly: the precise date of their removal is unrecorded but they had disappeared by the early eighteenth century (Stout Reference Stout2014: 80). The lead cross that was allegedly found in the grave was held at the church of St John the Baptist, Glastonbury, for around 100 years after the Dissolution (Barber Reference Barber2016). The forged artefact disappeared during the seventeenth century and was the subject of a modern hoax in 1981, when the British Museum was approached with an object supposedly found in the bottom of the lake at Forty Hall Park, Enfield, the site of a Tudor palace. The hoaxer was a skilled lead pattern maker capable of producing a copy. He served a prison sentence after refusing to produce the artefact for examination, which is believed to have been hidden or destroyed (Mawrey Reference Mawrey2012). The failure to preserve Arthurian artefacts in the centuries immediately following the Dissolution suggests that the abbey’s Arthurian legends were forgotten for a time. There was increasing scepticism about Arthur in the English court from the later sixteenth century and the English Arthurian cult declined significantly in the seventeenth century. In contrast, the Arthurian myth became more important in Scotland under James VI: Arthur was used to demonstrate Britishness and the political argument for political union under James I (Higham Reference Higham2002: 238).

Meanwhile, the Arimathean legend continued to gather pace at Glastonbury during the seventeenth century, embodied by the Legend of the Holy Thorn. The story elaborates on Joseph’s arrival at Glastonbury after his long journey from the Holy Land. It claims that Joseph paused on his way up Wearyall Hill and thrust his staff into the ground, whereupon the staff sprouted into a thorn tree. This motif of germination was shared with other British saints: for example, both Ninian and Etheldreda were associated with sprouting staffs that grew into trees (Walsham Reference Walsham2012: 35). Glastonbury Abbey also celebrated the cult of St Benignus, a follower of St Patrick who was associated with a sprouting staff. The staff of Benignus is perhaps represented by a tiny artefact from the excavations at the abbey: a gilt copper alloy rod with foliate decoration (Courtney et al. Reference Courtney, Egan, Gilchrist, Gilchrist and Green2015: 294; Fig. 8.39: 4) (Figure 5.11). The Glastonbury Thorn and others grown from it was observed to blossom each year at Christmas. The thorn is a form of the Common Hawthorn, Crataegus monogyna ‘Biflora’, which flowers naturally twice a year, in winter and spring. In the local context of Glastonbury, the second flowering of the thorn was interpreted as commemorating Christ’s nativity. More widely, the Glastonbury Thorn is consistent with Protestant interest during the seventeenth century in the natural world and the miraculous properties of nature (Walsham Reference Walsham2012: 45).

5.11 Devotional objects excavated from Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset): 1. Terracotta medallion; 2. Lead amulet; 3. Gilt copper-alloy decorative mounts, possibly from reliquary cross, box or book; 4. Gilt copper-alloy rod, possibly representing sprouting staff associated with St Benignus; 5&6. Gilded wings; 7. Copper-alloy plaque inscribed with Marian inscription SICUT LILIUM INTER SPINAS SIC AMICA MEA INTER FILIAS ET SIC ROSA I JERCHO (‘As the lily among the thorns so is my love among the daughters and as a rose in Jericho’) (Gilchrist and Green Reference Gilchrist and Green2015: 294).

Walsham has explored Glastonbury’s Legend of the Holy Thorn and concluded that there is no evidence within medieval sources for the tradition (Walsham Reference Walsham2004). A flowering thorn is mentioned in the Life of St Joseph of Arimathea, 1520, but the specific link between the flowering thorn and the staff of Joseph did not emerge until the Jacobean period (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 492–7). Popular interest in the Thorn coincided with the period when the destruction of the abbeys began to be regretted in some quarters. The Thorn was employed as a device in anti-puritan narratives: in 1653, Bishop Godfrey Goodman suggested that the tree may have begun flowering as a sign of God’s anger against the ‘Barbarous inhumanity’ of the Henrician attack on the monasteries (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 495). It became explicitly linked with the Royalist cause: the tradition began for the monarch to be presented with a sprig of the Glastonbury Thorn on Christmas morning, a tradition reinvented in the 1920s (Lyons Reference Lyons2014: 101). Glastonbury’s Thorn was subject to iconoclasm by the Roundheads during the Civil War, prompted by both its Royalist associations and its connection with the celebration of Christmas, which was regarded as pagan by puritans (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 134). This evocative symbol was vulnerable to both souvenir-hunters and iconoclasts, while it was venerated at the same time by both Protestants and Catholics. Stories circulated of misfortune that befell those who attacked it, transforming Glastonbury’s Thorn into a Catholic symbol of resilience in the face of puritanism (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 205).

The Holy Thorn also connected the Arimathea legend to the natural world and to the local landscape around Glastonbury Abbey. Nearby Chalice Well was drawn into the abbey’s complex biography: this natural chalybeate spring was visited from Mesolithic times and became an important source of water supply to the medieval abbey. It was known in the Middle Ages simply as Chalkwell (Rahtz and Watts Reference Rahtz and Watts2003), but its iron-rich water produced a red stain which became associated symbolically with the blood of Christ and the Grail legend. The medieval abbey funded the erection of a cover for the well, perhaps signalling the emergence of the cult (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 56). It was popularly believed that Joseph of Arimathea had buried the sacred cruets near the spring and that the water had become tinged red by the healing blood of Christ (Mather Reference Mather2009). In the mid-eighteenth century, Glastonbury was briefly celebrated as a healing spa focused on Chalice Well (Stout Reference Stout2008). The Arimathea legend took on a new dimension in the nineteenth century, with the popular West Country story that Christ himself had come to England as a boy and had walked the Glastonbury landscape. The Bible gives no indication of where Jesus spent the majority of his life, from the age of twelve to thirty. This silence provided the opening for one of Glastonbury’s most powerful stories: the ‘Holy Legend of Glastonbury’ purported that Christ had been brought to Britain by his great uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, in pursuit of the tin trade (Smith Reference Smith1989). This folktale became associated with William Blake’s poem, ‘And did those feet in ancient time’ (c.1808), which contrasted the heavenly Jerusalem that was created by Christ’s visit to England with the ‘dark Satanic mills’ of the Industrial Revolution. The myth that Jesus visited Glastonbury remains significant for many English Christians today, immortalised in the country’s unofficial anthem: Sir Hubert Parry’s hymn, Jerusalem (1916).

Monastic Afterlives: The Biography of Place

Glastonbury’s stories demonstrate the highly stratified nature of monastic memory – how layers of meaning are added by successive generations to connect place with the past. The institutional identity of the abbey was commemorated both in hagiography and in the landscape – its birth and death were key themes in structuring the biography of place and fuelling later folklore, from the Holy Thorn to Little Jack Horner and the Holy Legend of Glastonbury. It is significant that the monks constructed legends of Arthur and Arimathea that included their interment at Glastonbury Abbey (Carley Reference Carley and Carley2001b; Gransden Reference Gransden and Carley2001). It was not sufficient for the abbey merely to be associated with legendary figures; it needed to possess their mortal remains. The key memorial function of a monastery was as a mortuary landscape: the abbey fashioned itself as a mausoleum and reliquary for its legendary founders, while the presence of their graves strengthened the sacred heritage of place, bringing both spiritual cachet and economic potential for attracting pilgrims and patrons.

Narratives of closure and the finality of death helped to fix memory in the monastic landscape. Past and place were structured at Glastonbury through a range of material practices: the archaic styles of the Lady Chapel and Arthur’s tomb, the use of ancient ‘pyramids’ to mark Arthur’s grave, the forged ‘antique’ lead cross that identified Glastonbury as Avalon, the brass plaque and the Magna Tabula that conveyed to pilgrims the story of Joseph’s foundation of the old church. Glastonbury’s Dissolution story contributed darker elements to the biography: by the mid-seventeenth century, the abbey precinct was regarded as cursed and the area of the former church was believed to be haunted. The antiquary William Stukeley reported a local belief that those who quarried stone from the abbey ruins suffered ill fortune, while the economic decline of the town’s market was blamed on the fact that the building in which it was held was constructed of abbey stone (Walsham Reference Walsham2011: 292). The monastery remained a key signifier of place, with these local tales resonating with monastic loss, betrayal and the ‘bad death’ of Abbot Whiting.

Post-Reformation narratives reworked the legend of Joseph of Arimathea, suppressing the Marian association of the Lady Chapel and its Catholic connotations. The Arthurian connection was eclipsed by the importance of Arimathea in providing spiritual authority for the Protestant nation. The monuments to Arthur, his tomb and grave-site, disappeared silently and without comment. In contrast, St Joseph’s Chapel, Glastonbury’s monument to the antiquity and purity of the English church, endured the ravages of the Dissolution and post-medieval speculators. The material practices of salvage and preservation were shaped both by national narratives and local sentiments. New connections were forged with the local landscape, grafting the biography of Glastonbury Abbey with elements of the natural world – the Tor, Chalice Well and the Holy Thorn (see Figure 6.14). These associations were consistent with wider Protestant practices in the seventeenth century, marking a return to the medieval view that certain places in the landscape possessed supernatural power (Walsham Reference Walsham2012: 35). Glastonbury’s story is exceptional, but the abbey was not unique in extending its biography beyond the Reformation. The complex and celebrated case of Glastonbury Abbey demonstrates the enduring legacy of monasteries, their continuing power to inspire cultural imagination and to shape biographies of place. Glastonbury reveals the contested nature of place – why some memories are perpetuated while others are forgotten or erased – and how monastic afterlives continue to shape new versions of the medieval past.