Introduction

The Street-Level Bureaucracy (SLB) framework, as introduced by Lipsky (Reference Lipsky1980), examines how public policies – particularly in sectors like social welfare, education, health care, and labor – are implemented by frontline workers who directly engage with the public (Brodkin Reference Brodkin2011). This framework is grounded in the idea that there is often a gap between “policy as written” and “policy as implemented” (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980), emphasizing SLB’s discretion exercised in this process. Discretion is especially evident in how these workers manage individual cases and navigate complex decision-making tasks. Research has explored how this discretionary space is reshaped by various factors, such as accountability (Brodkin Reference Brodkin2008), digital standardization (Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Davis and Rummery1999), and collaborative work models (Grote Reference Grote2012). These transformations (Reddick Reference Reddick2005) occur across macro, meso, and micro levels. At the macro level, broader societal trends and changes – referred to as megatrends (European Commission 2022) – shape public administration, introducing challenges like digital transformation, social inequality, education diversity, evolving work patterns, new governance models, and demographic shifts. The meso and micro levels involve vertical tensions between management and SLBs and horizontal tensions among peers within interdisciplinary teams. These dynamics continuously redefine SLBs’ discretion, redefining their role as “de facto policy makers” (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980).

In recent years, there has been a growing focus on the organizational dimension as a key analytical perspective (Tummers and Bekkers Reference Tummers and Bekkers2014). This shift responds to the significant changes within public policy frameworks, particularly the welfare mix, which now involves collaboration between public, private, and third-sector actors (Giullari and Lucciarini Reference Giullari and Lucciarini2024), as well as the integration and hybridization of policy areas like health, social care, and employment (Rizza and Lucciarini Reference Rizza and Lucciarini2021). These developments, which have reshaped welfare systems and modes of policy delivery, are particularly evident in the Italian context, where scholars have emphasized the growing role of the third sector in welfare provision (Ascoli and Ranci Reference Ascoli and Ranci2002), the integration of policy areas following the reorganization of the socio-health and social assistance sectors (Law No. 328/2000), and the introduction of measures, such as the citizenship income, which merges elements of labor market policy and social assistance.

Amidst this shift towards a stronger welfare mix and the rise of public procurement in social services, which has led to significant outsourcing (Caselli et al. Reference Caselli, De Angelis, De Vita, Giullari, Lucciarini, Rimano, Fiorentino and La Chimia2021), there remains a gap in comparative analyses of how different organizational frameworks influence SLBs’ discretion. Aligning with recent scholarship on embedded agency in public policy implementation (Castles Reference Castles1981; Grin and Loeber Reference Grin, Loeber, Fischer, Miller and Sidney2007; Kontopoulos Reference Kontopoulos1993), this study explores how organizational rules, cultures, and constraints mediate the discretionary practices of frontline workers. Using a case study from Rome, which categorizes organizations into local health authorities Aziende Sanitarie Locali (ASLs), municipal agencies (social assistance offices), and third-sector organizations managing services through public tenders, this research examines how different organizational settings shape the discretionary practices of social workers (SWs). This approach highlights the central role that organizations play in producing differentiated policy implementation outcomes, moving beyond traditional individualistic views of discretion and contributing to broader discussions on the interplay between structure and agency in governance and public administration.

We administered a survey to 72 SWs, focusing on key aspects of discretion, such as autonomy, job satisfaction, and professional ethics (Hupe Reference Hupe2013) – elements that are central to Lipsky’s theory. These factors directly influence how workers manage tensions through their actions, thereby defining their discretionary space and decision-making processes. While these strategies may at first appear “fractal” (Wagner Reference Wagner, Godelier and Strathern1991), they reveal coherent patterns when viewed through the lens of discretion (Kjaerulff Reference Kjaerulff2020). Indeed, this study does not address the value orientations typically analyzed when comparing workers’ attitudes toward specific policies. Instead, it focuses on the relationship between organizational structure and discretion. The main hypothesis, supported by the survey findings, is that discretion is significantly influenced by the organizational context in which SWs operate, suggesting that it is more organizationally driven rather than merely subjective.

The paper is organized into the following sections. Discretion in organizations section provides an overview of the theoretical aspects of SLB, with a particular focus on the organizational dimension, and identifies gaps in existing research. Data and methods section outlines the data and methods used. Key empirical findings and Cross-organizational comparison sections present and analyze the empirical findings in relation to the research questions and theoretical context. Finally, the conclusion offers reflections on potential areas for future research.

Discretion in organizations

The discretion exercised by street-level bureaucrats is not determined solely by their personal characteristics or subjective attitudes, but is strongly influenced by the organizational context in which they operate (Cohen Reference Cohen2018). Organizational culture, managerial practices, and resource availability can significantly expand or constrain the actual discretionary space available to frontline workers (Brodkin Reference Brodkin2011; May and Winter Reference May and Winter2009). Evelyn Brodkin has made substantial contributions to understanding the organizational dynamics within SLB, introducing the concept of street-level organizations (Brodkin Reference Brodkin2011, Reference Brodkin2021). This conceptual shift reflects the increasing involvement of diverse actors – such as private for-profit and non-profit organizations – in delivering social services. Rather than replacing Lipsky’s original SLB framework, Brodkin’s approach builds on it by focusing on how individual workers operate within specific organizational settings. This interaction involves a continuous process of negotiation and redefinition of beliefs, practices, and objectives, shaping how SLBs perform their roles.

The literature on street-level organizations has explored the tension between individual agency and organizational structure, particularly regarding how it influences SLBs’ discretionary power (Vohnsen Reference Vohnsen2017; Andreotti et al. Reference Andreotti, Coletto and Rio2024), across both vertical and horizontal dimensions. Vertically, this involves examining the relationships among policy mandates set by institutions, the organizational management, and the frontline workers. The path from policy design to implementation is mediated by multiple interpretive layers, with organizational management playing a pivotal role in translating general directives into operational practice. In this regard, higher-level SLBs are described by some authors as “policy entrepreneurs” (Rizza and Lucciarini Reference Rizza and Lucciarini2021), since they interpret and shape policies in ways that influence organizational direction. Their effectiveness often depends on fostering “organizational sensemaking” (Weick Reference Weick1995), aligned with shared values and supported by stable systems of practices (Orr Reference Orr, Middleton and Edwards1990), providing stability and consistency amid internal and external changes.

An organizational culture oriented towards professional learning and peer support is crucial for discretion to be exercised according to professional values, up-to-date knowledge and ethical standards, rather than individual preferences or established routines (Sandfort Reference Sandfort2000; Virtanen et al. Reference Virtanen, Laitinen and Stenvall2018). In this sense, an organization’s capacity for learning – its ability to learn from experience and transmit knowledge over time – plays a decisive role in strengthening the quality of discretionary decision-making (Goh and Richards Reference Goh and Richards1997; Lavee and Strier Reference Lavee and Strier2019). Organizational theory has shifted away from the earlier modernist assumptions linking organizational stability with success and effectiveness (Hatch and Schulz Reference Hatch and Schultz2002), moving toward more dynamic conceptions that acknowledge the continuous pressures and changes organizations face. These approaches emphasize the need to identify factors that ensure stability through adaptable practices and processes, balancing continuity and flexibility. In this framework, Brodkin argues that routines should not be seen as constraints on discretion but rather as its manifestations (Brodkin Reference Brodkin2011). Accountability mechanisms and organizing practices grounded in an organization’s internal logic do not undermine discretion; instead, they provide a stable framework of norms, values, and practices within which SLBs operate. These insights reveal how discretion is shaped not only by individual orientation but also by the broader organizational environment and its relationship with frontline workers. Discretion, to be effectively exercised and aligned with public interest, therefore requires not only individual autonomy but also an enabling organizational context, that invests in continuous training, peer supervision, and structured professional dialog (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980; Riccucci Reference Riccucci2005b). Transformational leadership can further enhance this context by fostering work environments that support critical thinking and ongoing improvement (Keulemans and Groeneveld Reference Keulemans and Groeneveld2020).

This perspective is particularly relevant in settings characterized by increasing diversity in organizational models involving SWs. Despite strong national path dependencies, the implementation of social policies increasingly relies on a mix of public, private, and third-sector providers and a deeper integration of policy areas. These shifts in both actor involvement and policy boundaries have largely been driven by financial constraints and the need to reformulate welfare policies in response to austerity. In decentralized systems, local decision-making – shaped by region-specific priorities – has led some authors to discuss the “territorialization” of social policies (Kazepov Reference Kazepov2010). Furthermore, administrative responsibilities are split among different entities: municipal agencies are responsible for social assistance and socio-educational services, while regions manage socio-health services. Fiscal constraints and local conditions have led to diverse welfare arrangements and hybrid provider “mixes”. This complex system of relationships – spanning co-design, delegation, contracting out, and other contractual arrangements – reflects a broader strategy to downsize the state’s role in social service delivery.

Within this intricate and localized landscape, SLBs operate under a variety of working conditions, across standard and non-standard contracts, in public, private, for-profit, and non-profit sectors. Their discretionary behavior reflects the dynamic interaction between individual agency and organizational structure (Hupe and Buffat Reference Hupe and Buffat2014). Underestimating the structuring role of the organizational context risks misrepresenting the actual mechanisms through which public policy is implemented (Brodkin Reference Brodkin2011; Cohen Reference Cohen2018, Lucciarini et al. Reference Lucciarini, Rimano and Michele2024). While these organizations formally adhere to public service principles, they function under varied logics. For instance, cooperatives operate in a competitive environment where minimizing labor costs is a primary strategy to secure public procurement contracts (Celata et al. Reference Celata, La Chimia and Lucciarini2024; Giullari and Lucciarini Reference Giullari and Lucciarini2024). This dynamic often leads to cost-driven service models that strain frontline workers, who are already under pressure due to the relational demands of their roles (Giullari and Lucciarini Reference Giullari and Lucciarini2024; Tummers and Bekkers Reference Tummers and Bekkers2014). Municipal agencies, meanwhile, suffer from chronic understaffing and wide discrepancies in engagement between junior and senior staff, due to rigid contractual frameworks that hinder career advancement and salary progression (Giullari and Lucciarini Reference Giullari and Lucciarini2024). At the same time, increasing reliance on experimental rather than structural interventions creates further ambiguity for SLBs, who must navigate overlaps and gaps in service delivery. Lastly, workers in ASLs operate in more standardized and bureaucratic environments, marked by formal procedures and accountability requirements. However, they also face challenges related to multidisciplinary teamwork and complex case-management responsibilities.

Ultimately, what is essential in the relationship between SWs and their organization is not only the organizational setting, but also the strategies adopted to manage internal and external pressures. These strategies distinguish adaptive and learning-oriented organizations from those more resistant to change. The extent to which professional discretion is enabled or constrained depends largely on an organization’s capacity to evolve and respond to the shifting demands of public service delivery (Cohen Reference Cohen2021).

Data and methods

The survey was conducted in a metropolitan area due to the diverse organizational forms present: public socio-assistance (municipal agencies), public socio-health (local health authorities), and the third sector (cooperatives engaged in outsourced service provision by public authorities). Given the research question and practical considerations (time and cost of data collection), we employed a non-probabilistic purposive sampling method. This approach enabled the recruitment of respondents who, besides having specific socio-demographic characteristics, were willing to participate in the study (van Engen Reference van Engen and Hupe2019).

Non-probabilistic quota sampling has certain limitations compared to probabilistic techniques: it does not allow for probability estimates, making it impossible to assess the margin of error; if the information for quota determination is inaccurate, the resulting sample may not accurately reflect the population structure under investigation; and while the sample may be representative for the control characteristics used, it may not represent other key attributes (attitudes, values, opinions, behaviors, etc.), which are the study’s main focus (Di Franco Reference Di Franco2010; Gobo Reference Gobo, Seale and Giampietro Gobo2004b).

Since the research aimed to analyze the relationships between the variables of interest rather than infer results to the entire population, the first two limitations were not problematic. The issue of representativeness in social research samples is a broader concern that affects all samples, including probabilistic ones (Marradi Reference Marradi and Ceri1997). In their influential paper on the representativeness of case studies in organizational analysis, Seawright and Gerring (Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) describe the effort to generalize results as “heroic”. This challenge has been addressed across various disciplines, given that this type of research often relies on a limited number of interviews (Langley and Royer Reference Langley and Royer2006).

Relying on a few interviews for a case study, often due to the small number of workers in an organization, follows an “intrinsic” logic (Guba and Lincoln Reference Guba and Lincoln1989) aimed at understanding the dominant and latent aspects of the specific “organizational culture” (Hofstede Reference Hofstede1991). In this approach, the organizational culture is seen as the main mechanism that shapes workers’ ways of thinking and acting, and researchers look to respondents’ answers for insights into this culture. A recent contribution to this literature has enriched the discussion on the use of surveys in organizations, suggesting that researchers should exercise greater control over the sample of respondents in order to capture diverse perspectives of key roles within an organizational unit (see Verleye Reference Verleye2019).

The institutional structure of Rome has a dual configuration: centralized for the planning bodies of social policies – under the direction of the V Department of the City of Rome – and decentralized for implementation, with the municipal agencies – 15 first-level subdivisions with managerial, financial, and accounting autonomy – having the freedom to design specific area-based projects. This structure is important in defining certain value orientations and professional commitments at the central level, a factor considered valuable for comparing the different organizations selected across the city.

The decision was made to administer the questionnaire solely to SWs registered with the professional order, as they constitute a qualified professional bureaucracy (Mintzberg Reference Mintzberg1979) with unifying elements such as professional and ethical codes. The SLB perspective tends to reduce not only professional differences but also the distinction between different regulatory figures like professionals (in the strict sense) and non-recognized or generic figures (non-professionals). All those who interact with citizens to provide services, benefits, or sanctions on behalf of the state, regardless of their professionalism, share a certain discretionary power that can influence the processes and outcomes of implementation. This point is critical in SLB literature, as frontline workers are not elected but still exercise “political” power (Peeters and Campos Reference Peeters and Campos2022).

Focusing on discretion as a cross-cutting analytical concept might be limiting, as it does not reveal the differences in the complexity of street-level functions and the types of professions assigned to manage them, nor the different ways they act and interact in their roles and the resulting effects. Specifically, it does not distinguish between professional bureaucracy, which is regulated by identity, ethical codes, and institutionalized qualifications, and specific control mechanisms – organized to manage complex discretion – and so-called “machine bureaucracy” (Mintzberg Reference Mintzberg1983), composed of personnel without formal status and specialized training.

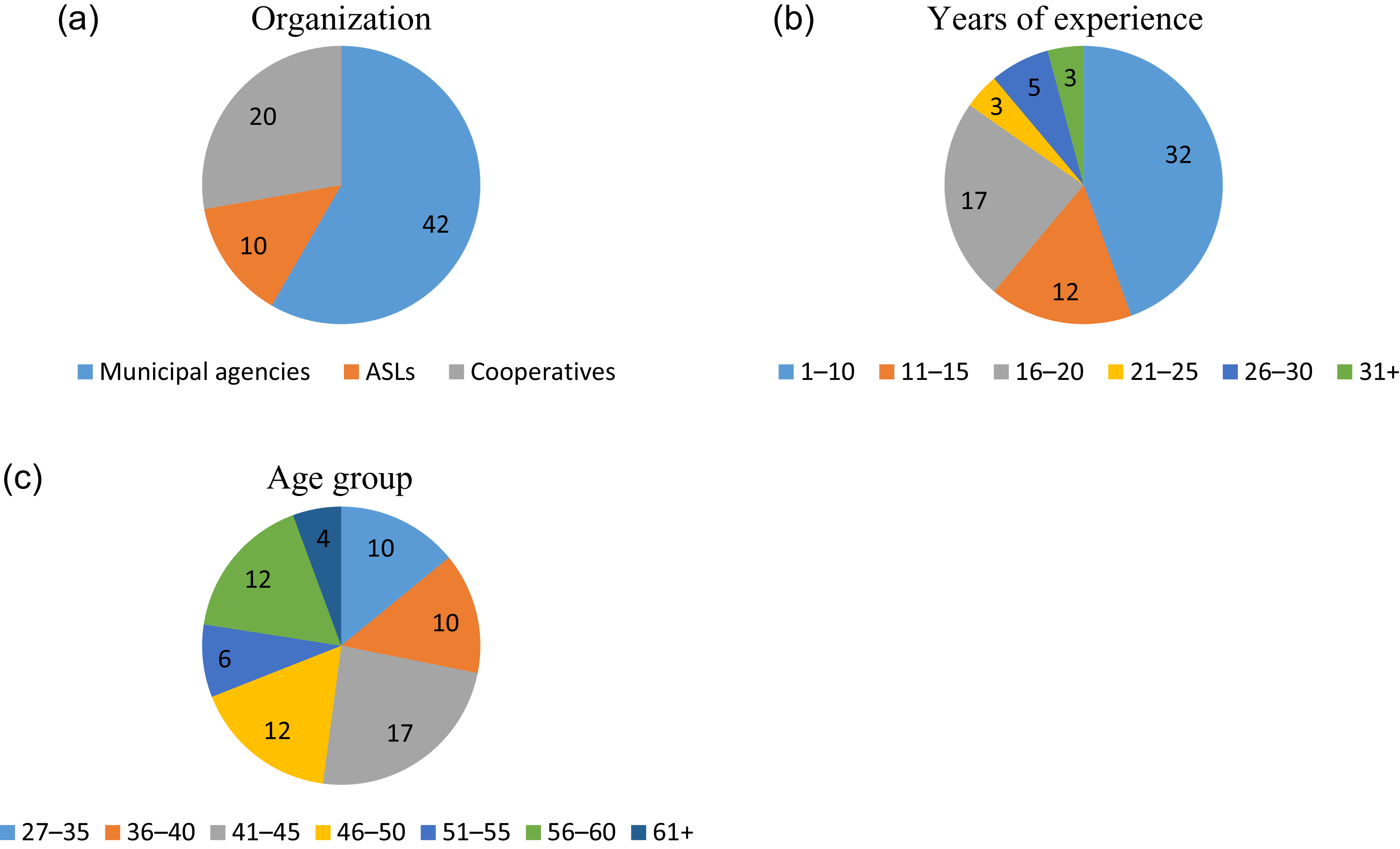

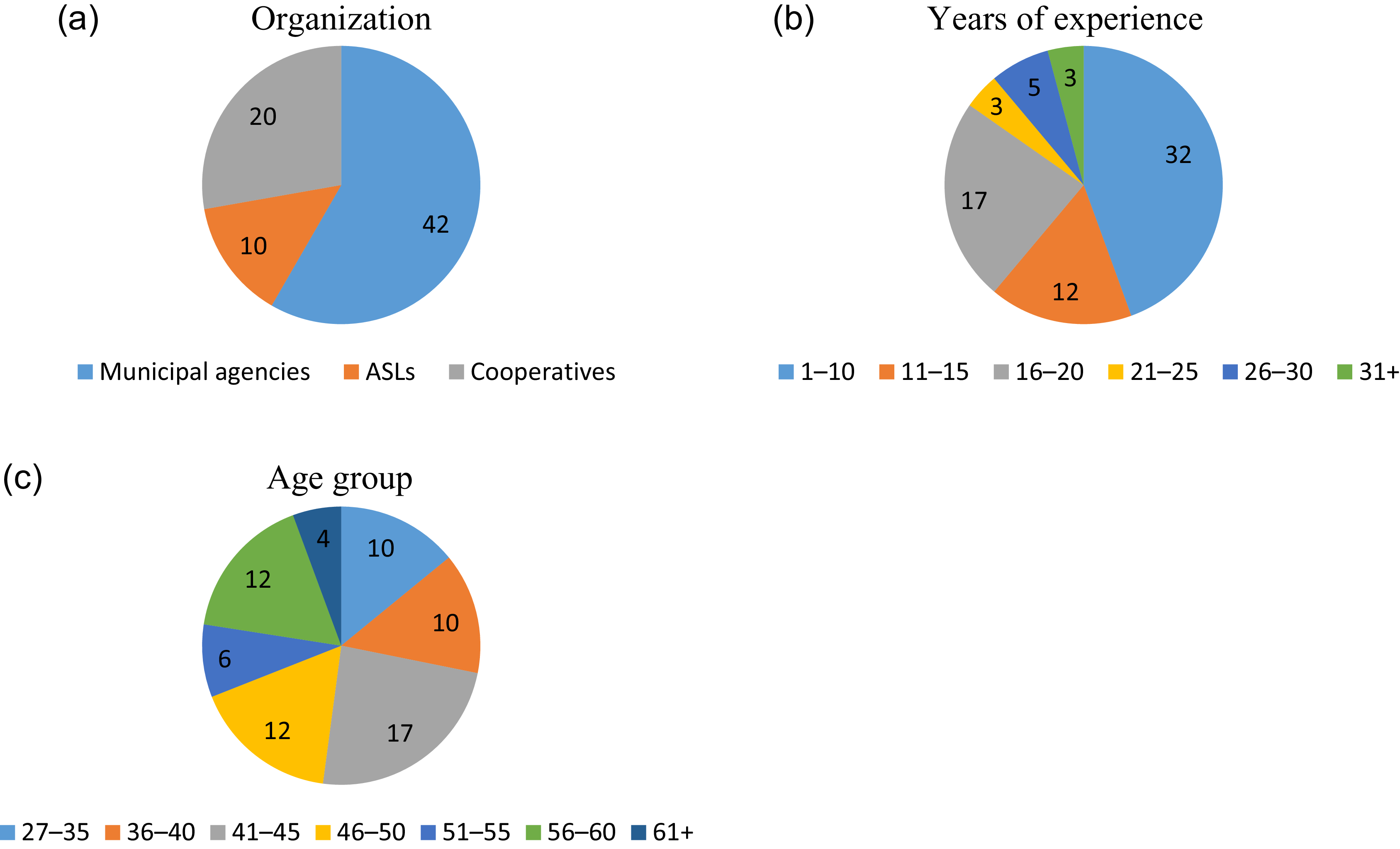

The individuals in the target population were identified among professionals employed in the three organizational settings described (ASLs, municipal bodies, and third-sector cooperatives) who met the selection criteria. In detail, as part of the study, 72 SWs participated in face-to-face interviews, with a pre-coded questionnaire administered by the interviewers (PAPI mode). The composition of the sample is detailed in Figure 1a–1c.

Figure 1. (a–c) Distribution of interviews by sampling criteria. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Since their establishment, organizational studies have grown significantly, developing a multi-paradigmatic profile and demonstrating considerable creativity in data collection methods, similar to other fields of social research. The increasing popularity of mixed methods research has complicated the relationship between research and inferential statistics, reducing the focus and concern for this connection (Teddlie and Tashakkori Reference Teddlie and Tashakkori2009). Nowadays, data collection methods are increasingly embedded within broad and fluid currents of thought, discouraging rigid adherence to specific epistemological positions and instead promoting a pragmatic approach in method selection (Buchanan and Bryman Reference Buchanan and Bryman2007). Traditional concerns about representative sampling and statistical generalization have long been complemented by arguments highlighting the value of small sample studies and the epistemology of the particular, based on naturalistic (Stake Reference Stake, George, Michael and Daniel1983) and analytical generalization (Yin Reference Yin2018).

It is important to note that in any type of design, representativeness, even if established for certain attributes, does not automatically extend to other properties. The assumption that a sample representative of certain socio-demographic characteristics will also be representative of attitudinal characteristics is problematic and should be carefully assessed (Marradi Reference Marradi and Mannheimer1989). For these reasons, and those previously discussed, we opted for purposive sampling rather than a probabilistic-random sample. The research strategy we employed can be described as “exploratory” or “heuristic” (McNabb Reference McNabb2018). Research using small samples goes beyond the traditional questions of “how many cases?” and “with what results?” to explore questions of “who?” and “why?”.

This approach allows researchers to combine the advantages of a detailed understanding of the case study with the robustness and rigor of statistical techniques (Goggin Reference Goggin1986). It is not necessarily a matter of choosing between conducting research with an (approximately) random sample or a completely subjective sample; between a (even partially) probabilistic sample and a sample whose representativeness cannot be asserted. Bridging the gap between orthodox rationalism and postmodern nihilism underlying these two positions, the researcher can tackle the issue of representativeness in practical terms, considering the nature of the units of analysis rather than adhering to standard procedural rules.

In other words, between distributive generalization, involving estimates on the distribution of a phenomenon in the population based on the sample results, and theoretical generalization, pertaining solely to the relationships between variables present in the sample (Gobo Reference Gobo2004a), our work will focus on the latter.

Measuring organizational effects on street-level bureaucrats’ discretion

Discretion is a core element in the study of SLB, but it remains a complex and often ambiguous concept that many scholars find difficult to measure. Some researchers suggest an integrated approach from various theoretical perspectives to unpack its main dimensions. For instance, Hupe (Reference Hupe2013) differentiates between legal, economic, sociological, and political approaches, both from a theoretical perspective and in terms of the roles that discretionary actors play. Hupe’s work also provides a comprehensive review of studies that have made discretion their primary focus of research. Building on the works of Soss et al. (Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011), Brodkin (Reference Brodkin2011), and Dubois (Reference Dubois2010), discretion is viewed as a relative concept and operationalized according to the specific goals of the research. Some studies have centered on comparing SLBs within the same organization, emphasizing divergence, by employing techniques like “vignettes” to identify typical user profiles and better understand the decision-making processes of SLBs (Gofen Reference Gofen2014). Other scholars have explored discretion from a professional standpoint (Evans Reference Evans2010), distinguishing between the legal autonomy granted by regulations (de jure) and the actual autonomy exercised in practice (de facto). The diversity of these approaches suggests that discretion should be understood as a multi-dimensional concept (Hupe Reference Hupe2013), requiring a pluralistic approach that can capture its various facets in different organizational settings.

These varied perspectives converge on identifying three fundamental frameworks that SLBs use to guide their actions: rational choice (e.g., Brehm and Gates Reference Brehm and Gates1997; Brodkin Reference Brodkin2011; Riccucci Reference Riccucci2005a), ethical choice (e.g., Kaptein and van Reenen Reference Kaptein and van Reenen2001; Loyens and Maesschalck Reference Loyens and Maesschalck2010), and professional choice (e.g., Maynard-Moody and Musheno Reference Maynard-Moody and Musheno2003). These frameworks form the foundation for SLBs’ decision-making processes and are central to understanding how discretion is exercised (Gofen Reference Gofen2014). Regarding these choice frameworks, three key dimensions have been identified: autonomy (aligned with rational choice), professional satisfaction (linked to professional choice), and adherence to ethical standards (connected to ethical choice). These dimensions resonate with long-standing debates on the motivations and behaviors of street-level bureaucrats. As Lipsky (Reference Lipsky1980) emphasized, autonomy is central to the discretionary power that bureaucrats exercise in managing complex and ambiguous policy environments. Professional satisfaction, on the other hand, reflects the role of internalized professional norms and the pursuit of competence and efficiency, as discussed by Tummers et al. (Reference Tummers, Bekkers, Vink and Musheno2015). Finally, adherence to ethical standards aligns with the idea that public servants frame their decisions within a moral reasoning structure, guided by values of fairness, equity, and justice (Maynard-Moody and Musheno Reference Maynard-Moody and Musheno2003). This tripartite distinction offers a heuristic lens for analyzing how different logics – instrumental, normative, and ethical – guide decision-making processes in frontline public service.

In our study we examined these dimensions using three different sets of variables, with twenty items per dimension. The operationalization of the three core dimensions was informed by established theoretical and empirical literature in the fields of social work and organizational studies. The dimension of professional autonomy was measured through a set of items capturing the respondent’s perceived capacity for independent decision-making, discretionary use of professional judgment, and the extent to which their practice is influenced or constrained by organizational or bureaucratic structures (Evans and Harris Reference Evans and Harris2004; Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980). Job satisfaction was assessed using items reflecting key aspects of professional experience, such as workload manageability, recognition from colleagues and supervisors, and an overall sense of fulfillment and engagement in one’s role. The dimension of adherence to ethical standards was measured through items designed to assess the perceived ability to uphold core ethical principles of the profession – such as respect for clients’ rights, confidentiality, and commitment to social justice – even in complex or adverse organizational contexts. This included respondents’ self-assessed capacity to resist pressures that might lead to ethical compromises and to act consistently with the values articulated in professional codes of ethics, despite potential institutional or systemic constraints.

All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strong disagreement to strong agreement. Internal consistency for each set of items was verified using Cronbach’s alpha, indicating satisfactory levels of reliability for all three dimensions.

The study focuses on analyzing how discretion is expressed through these dimensions – autonomy, ethical adherence, and professional satisfaction – within organizations that have distinct structures and organizational forms. It compares third-sector cooperatives, which tend to have less rigid procedures and emphasize collaboration over hierarchical control, with ASLs (public health), which are characterized by more standardized procedures and greater control over workers’ activities. Municipal agencies occupy an intermediate position between these two extremes, offering a mix of structured and flexible approaches (Rossi Reference Rossi2024). This comparison aims to highlight how different organizational contexts shape the way SLBs exercise discretion, reflecting varied balances between autonomy, ethical considerations, and professional satisfaction across different organizational environments.

Key empirical findings

The data clearly show differentiated experiences of discretion among SWs across various organizational settings – cooperatives, municipal agencies, and ASLs – highlighting differences not only in autonomy, adherence to ethical codes, and job satisfaction, but also in how vertical and horizontal relationships affect these dimensions.

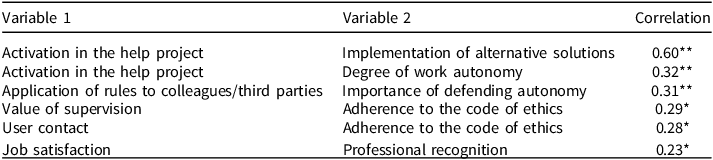

In terms of technical-professional autonomy, SWs in cooperatives report the highest levels, with 91.6% feeling “quite” to “very much” autonomous. This autonomy is often supported by horizontal relationships within the organization, where collaboration and peer trust enhance discretionary capacity. It is worth noting that autonomy correlates strongly with the ability to provide flexible, personalized responses to users’ needs (r = 0.60), underscoring the centrality of discretion in enabling tailored interventions. However, the level of public recognition – understood here as both organizational feedback and user acknowledgment of professional value – is considerably lower (r = 0.23). This disconnect highlights a tension between the quality of professional practice and the visibility or appreciation of SWs’ work, particularly in settings where interactions with users are less visible or institutionally valued. By contrast, SWs in municipal agencies report substantially lower autonomy: only 28.6% feel “very much” autonomous, while 71.4% report moderate to low levels. This is partially explained by stronger vertical controls and hierarchical oversight, which limit discretionary room. ASLs’ SWs report intermediate levels (70% sufficient), but face pressures both vertically – from management demanding rule compliance – and horizontally – from colleagues, due to coordination and role negotiation within teams.

Private-sector SWs (cooperatives) more frequently report the need (65%) to defend their autonomy from external pressures, likely reflecting their greater independence combined with weaker institutional protection. Conversely, 42.9% of municipal SWs feel “very much” protected from interference, reflecting how low autonomy may coincide with more rigid control structures that paradoxically reduce external exposure while constraining internal discretion.

Regarding the ethical code, almost all SWs (95.8%) affirm its importance. Nonetheless, organizational and relational dynamics affect levels of compliance. Municipal SWs are the only group reporting some “little” compliance (4.8%), likely reflecting tensions in supervisory expectations or ambiguity around institutional ethics. Cooperatives show the highest “very much” compliance (65%), suggesting that peer-based environments may better support mutual accountability and ethical alignment.

When it comes to applying the ethical code in peer relationships, compliance varies more widely. Overall, 26.4% report low enforcement among colleagues, with ASLs leading in ethical peer behavior (80%), followed by cooperatives (75%) and municipal agencies (71.4%). These differences appear more related to challenges in coordination than to deliberate ethical lapses.

Professional satisfaction mirrors these organizational and relational specificities. SWs in cooperatives express higher satisfaction and recognition, supported by flatter hierarchies and stronger peer collaboration. In contrast, municipal SWs report the highest dissatisfaction (21.4% “slightly” satisfied), with none reporting maximum satisfaction. This may stem from constrained roles, limited user visibility, and a lack of meaningful recognition. ASLs fall between these extremes, with more balanced levels of satisfaction and recognition.

Importantly, recognition is not merely internal or organizational, but it is also shaped by the quality of relational work with users and peers. When SWs can act autonomously and cultivate meaningful user engagement, public recognition appears more likely. Where discretion is constrained and relational work perceived as devalued or proceduralized, recognition tends to diminish, regardless of performance.

Finally, the data reveal that networking capacity emerges as a further layer of discretion. SWs often operate beyond formal job boundaries, mobilizing professional networks and contextual knowledge to bridge service gaps. This highlights how discretion increasingly involves managing inter-organizational cooperation and adapting to complex, fragmented welfare systems.

Overall, these findings underscore how vertical (managerial) and horizontal (peer and user-facing) dynamics structure SWs’ discretionary space. Cooperatives, with more collegial settings, enable broader discretion, stronger ethical commitment, and more relationally anchored forms of recognition. In contrast, municipal agencies’ hierarchical systems and limited user engagement restrict discretionary capacity and reduce both internal and public appreciation of professional value. ASLs remain a hybrid case.

Cross-organizational comparison

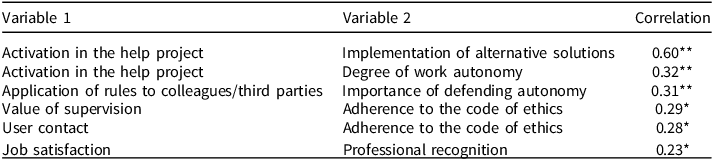

When analyzing the dimensions of discretion across the various types of organizations in which SWs operate, a complex and nuanced picture emerges (see tab.1). There are significant correlations that illustrate how SWs often exercise their discretion outside the boundaries of conventional intervention frameworks. This is particularly evident in the strong correlation (r = 0.60) between the degree of autonomy afforded to SWs and their ability to adapt flexibly to address the diverse and multi-dimensional needs of their clients. Autonomy allows SWs to deviate from standard practices to create individualized strategies that cater specifically to the complexities faced by the users. The flexibility required for such individualized approaches often leads to the process of defining intervention objectives diverging into a range of distinct strategies that are molded by the SW’s discretion and judgment (r = 0.32). This divergence underscores a critical point: the need for SWs to continuously adapt both to the rigid structures of institutional frameworks and the ever-changing needs of the users they serve.

Table 1. Main correlations between social workers’ job characteristics

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed); * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

A key insight from our analysis is the intrinsic link between autonomy and innovation. We operationalized autonomy through items that captured the degree of discretion SWs perceive in adapting or bypassing standard protocols, while innovation was measured through the frequency and extent of newly adopted intervention methods not formally codified by organizational guidelines. Autonomy is not merely a passive attribute but is closely tied to the ability of SWs to develop new, creative, and effective approaches and solutions within their professional roles. In environments that are highly formalized, where rules and protocols dominate, greater autonomy can foster stable inter-organizational exchanges and relationships that enhance the clarity and coherence of service delivery (sense-making), thereby promoting innovative practices. Conversely, in less standardized environments, where the space for maneuvering is inherently broader, autonomy allows SWs to experiment with new methods and processes (r = 0.31).

These characteristics of adaptability and openness to innovation, supported by an autonomous working culture, are more evident among SWs in the private sector, where collaboration within teams or across different sectors is more prominent. Here, networking and collective resource pooling are favored over rigid hierarchical structures. This preference for networking clearly distinguishes private sector SWs from their counterparts in public settings like ASLs (public health) and municipal agencies, where a more hierarchical conception of collaboration prevails (r = 0.29).

Across all organizational contexts, the dimension of ethical conduct remains a fundamental aspect of SW practice. SWs consistently highlight the importance of fairness, transparency, and the need for building strong, knowledge-based relationships with their clients as essential for developing personalized care plans that are responsive to individual needs (r = 0.28). This ethical orientation is not merely a formal adherence to the code of ethics but involves a deeper commitment to understanding and responding to the unique situations of users. This aspect is particularly pronounced among private sector SWs, who are generally more inclined to prioritize personalized approaches than their colleagues in the public sector. This finding may reflect the different incentive structures and service cultures in the private sector, where responsiveness and personalization are often strongly emphasized, sometimes in connection with client satisfaction or contractual flexibility. However, as noted in the literature, the opposite reasoning can also be valid: public sector workers, less constrained by reimbursement logic and profit metrics, may in fact have more space to broaden services over longer timeframes. The data thus highlight a tension that deserves further exploration, rather than a definitive causal claim. This divergence may stem from the more flexible and less bureaucratic environment in which private sector SWs operate, granting them more freedom to exercise their professional judgment in shaping tailored interventions.

Moreover, job satisfaction among SWs is found to be intimately connected to the level of autonomy they experience in their work. Job satisfaction was measured using items related to the perceived alignment between professional values and organizational objectives, the emotional gratification of user feedback, and the perceived recognition of one’s work. Its connection to discretion was established through correlation with indicators of perceived freedom in choosing interventions and activating non-standard resources. Indeed, autonomy allows SWs to implement alternative solutions and respond directly and effectively to user needs, providing them not only with a sense of professional fulfillment but also with a degree of recognition for their efforts. However, while autonomy and job satisfaction are closely linked, the degree of recognition that SWs receive for their work is often only partially realized (r = 0.23). This partial fulfillment reflects a gap between the potential of SWs to make meaningful impacts through their work and the formal acknowledgment they receive from their organizations or peers.

Further analysis reveals that the discretion SWs exercise is heavily influenced by their ability to leverage a broad network of organizations and resources, as well as their understanding of the wider territorial context, including both its assets and vulnerabilities. This broader perspective is crucial, as it highlights how SWs’ decisions are shaped not only by internal processes and policies implemented within their own organizations but also by external organizational networks, as well as the socio-economic environment in which they operate. This is reflected in responses that highlight how inter-institutional partnerships (e.g., with NGOs or local associations), the availability of territorial resources (housing, labor services), and the socio-economic fragility of local communities influence both the scope and limits of discretionary actions. For example, SWs in under-resourced areas reported a greater reliance on informal networks to compensate for service gaps. The ability to navigate these multiple dimensions effectively is a key determinant of the degree of discretion that SWs can exercise in their roles.

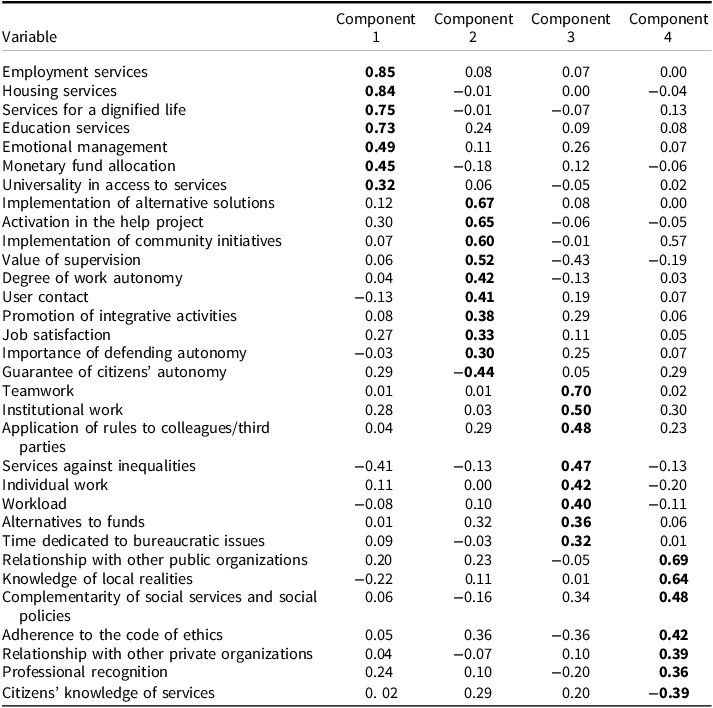

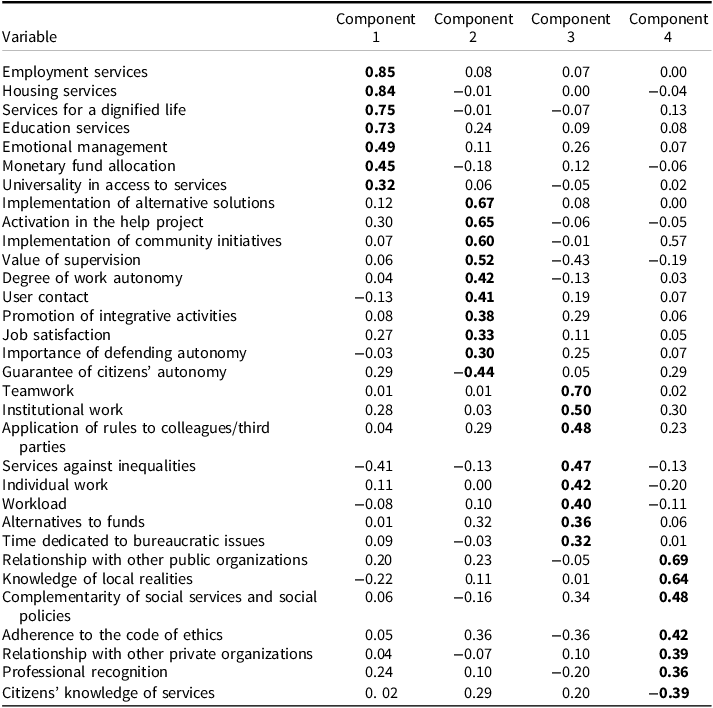

During the interviews, questions were posed about service characteristics, areas of SW intervention, and target categories. To assess the association between these data and the indicators used for discretion, and to better understand the broader cultural-normative space within which SWs operate, we submitted the items discussed thus far, along with the sociographic attributes of the respondents, to a principal component analysis, using a single large basket of variables. A fairly clear picture emerged, demonstrating coherence among the three identified dimensions of discretion and suggesting the inclusion of a fourth factor (see Table 2).

Table 2. First four components of social workers’ discretionary power

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis.

Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

Rotation converged in 6 iterations.

The first component refers to the cross-cutting nature of SW interventions, linked to the ability to apply their expertise to respond to users – in terms of both technical-professional and psychosocial skills, such as stress and emotional burden coping. In particular, support to housing and a dignified life – through income support or integration of ordinary expenses – are the measures that SWs are most “satisfied” to activate. These measures yield better outcomes for organizations, enabling them to address and alleviate users’ temporary needs, while committing limited resources in both scope and duration. Temporary economic difficulties, which in North American literature are associated with the dimension of poverty and in European literature with the decrease in well-being (Nau and Soener Reference Nau and Soener2019), represent one of the most interesting phenomena in social sciences. They are linked to new forms of economic insecurity and help explain the recalibration of social policies towards a more transitory nature (on the topic, see Ranci et al. Reference Ranci, Beckfield, Bernardi and Parma2021). Such measures also enhance workers’ job satisfaction, as they are able to meet user needs, while adding an “extrinsic reward” (Kalleberg Reference Kalleberg1977) to their work, thereby aligning organizational outcomes with their professional and value-based mission.

The second component relates to the centrality of autonomy in exercising discretion to respond to user needs, particularly with respect to the ability to activate alternative measures, including supranational and/or complementary ones, by assembling a collage of different policy tools. These results underscore the link between autonomy and innovation: as several authors have shown, these elements are positively correlated. Autonomy indeed fosters innovation, both within highly formalized work contexts – where it facilitates stable inter-organizational exchanges and relationships that increase the level of sense-making – and in less standardized contexts, where the worker’s maneuvering space is inherently broader (see Pichault et al. Reference Pichault, Diochon and Nizet2020).

The third component elucidates the ethical dimension of discretion in its various aspects. This includes different modes of practice – team-based, collaborative, and individual as well as SWs’ relationship with their organization, particularly the time dedicated to institutional and/or bureaucratic tasks, perceived as a significant part of their responsibilities. Parallel to the link between autonomy and innovation, both in highly formalized and less formalized contexts, adherence to and invocation of the code of ethics reinforce sense-making within organizations, and connect discretion to how ethical norms are interpreted and applied within different settings.

Finally, a fourth component emerges, operationalizing an additional dimension of the discretion among social and labor assistants: the dimension of networking. A SW’ ability to mobilize a broad network, comprising other organizations, and to possess deep knowledge of the territory, its assets, and its vulnerabilities, constitutes a key structural factor along which discretion is exercised. This dimension, also identified in other research, confirms that SLBs’ decision-making is shaped not only by internal organizational elements, related to the services provided, but also by external ones (Rizza and Lucciarini Reference Rizza and Lucciarini2021).

The application of principal component analysis to the various items related to discretion offers a comprehensive and coherent picture, highlighting how autonomy, ethics, job satisfaction, and networking are interrelated and jointly define how discretion is exercised across different sectors. The multivariate analysis reveals that SWs’ discretion is not merely a matter of individual autonomy or professional independence; rather, it entails a complex interplay involving the understanding and management of both internal organizational processes and external environmental conditions. SWs must constantly negotiate their space for action, balancing the constraints imposed by organizational structures with the opportunities afforded by external partnerships and community networks. This points to a more holistic understanding of professional discretion, where autonomy is continually redefined through interactions occurring both within and beyond organizational boundaries, enabling SWs to pursue their mission of delivering comprehensive and effective social care.

Conclusions

In recent years, research on SLB has expanded significantly, incorporating a wider range of theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches (Tummers et al. Reference Tummers, Bekkers, Vink and Musheno2015). Brodkin’s (Reference Brodkin2011) influential call to move beyond traditional public agencies has encouraged scholars to include third-sector and non-state actors in their analyses of policy implementation. These actors, often operating at the frontline, play a central role in shaping public service delivery through their interactions with citizens. As a result, scholarly attention has increasingly turned toward how different organizational settings influence the exercise of discretion.

Discretion remains a cornerstone of SLB research, but it is now understood less as an individual attribute and more as a contested and negotiated practice shaped by organizational structures and managerial regimes (Destler Reference Destler2017; Jacobsson et al. Reference Jacobsson, Wallinder and Seing2020). In parallel, research on professional roles has examined how discretion is reconfigured in response to new organizational imperatives – such as performance management, digitalization, and collaborative work arrangements – highlighting its evolution within specific institutional environments (Gaeta et al. Reference Gaeta, Ghinoi, Silvestri and Trasciani2021).

Building on this evolving body of literature, the present study shows that discretion is deeply embedded in organizational settings. The findings reveal a strong “organizational effect” on how discretion is perceived and enacted by frontline workers. By comparing different types of organizations – local health authorities, municipal bodies, and third-sector cooperatives – the analysis illustrates how variations in structure, culture, and work conditions shape how SWs interpret and exercise discretion.

This meso-level perspective offers a valuable complement to those macro-institutional analyses (e.g., Trasciani et al. Reference Trasciani, Esposito, Petrella, Alfano and Gaeta2024) which show that institutional quality significantly influences third-sector behavior across Italian provinces. While their research highlights how organizations adapt to broader institutional environments, the present study reveals how internal organizational dynamics mediate frontline discretion. Taken together, these perspectives contribute to a multi-layered understanding of policy implementation, that spans institutional contexts, organizational mediation, and individual agency.

In this light, the paper contributes to current debates by advancing the concept of embedded agency, illustrating how discretion is not merely granted or possessed, but rather co-produced within everyday organizational routines, cultural norms, and professional relationships. Street-level actors are not passive implementers of top-down rules; instead, they are embedded agents whose practices reflect the interplay between institutional structures and the lived realities of organizational contexts.

Data availability statement

Lucciarini, Silvia; Santurro, Michele; Rimano, Alessandra, 2025, “Replication Data for: Measuring Organizational Effects on Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Discretionality: A Comparative Study of Three Italian Contexts”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZY6DGL, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project “Public Administration and Artificial Intelligence (PAIR)” (Major Research Projects – Major Projects 2024, grant no. RG1241909CBD96DD) and builds upon and extends the previous project “What Happens in the City? What Do Firms Seek from Public and Private Labour Intermediators in Urban Areas: A Street-Level Perspective” (Medium Research Projects, 2020; grant no. RM120172889E361C), both financed by Sapienza University of Rome and under Principal Investigator Silvia Lucciarini. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and valuable suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this paper.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.