In September 1859, a man identified only as “Ned” in British records left his temporary home in the Sheffield/Rotherham area in the north of England. Ned was later identified as a Zulu man who had fled the Zulu Kingdom during its 1856 civil war, arriving in neighboring British-colonized Natal. Here, Ned was employed by Thomas Handley, who was born near Rotherham and emigrated to Natal in 1849–50. Handley had married a Scottish-born woman and set up the firm Handley & Dixon in Pietermaritzburg before settling in Greytown.Footnote 1 The family returned temporarily to the Sheffield area in 1859, with Ned accompanying them as a caregiver to their children. After Ned's disappearance a few months into their stay, a manhunt ensued. Although slavery was illegal throughout the British empire, locals ruminated on Ned's possible status as a “slave”; and the case thus attracted the interest of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and that of its secretary, Louis Alexis Chamerovzow. Toward the end of October, Ned was “captured” and taken to London and housed in the Strangers’ Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders. Ned's repeated escapes and his trials for sheep theft transfixed the public and resulted in detailed press coverage in Britain. Eventually, the various individuals and organizations that involved themselves with Ned's case appear to have determined that he should be returned to Natal, despite his protestations. Ned's untimely death in January 1860 meant this plan was never enacted.

While Ned's case is more or less unknown, historians have long debated the British reception and treatment of people of color, including those from Africa and the African diaspora, during the Victorian period and beyond.Footnote 2 Many scholars have cautioned against presuming racial intolerance was a fixed, innate, or timeless feature of British society.Footnote 3 Because historical subjects’ “race” is often unmarked in sources, and sources such as newspapers tend to emphasize more remarkable (and perhaps less common) instances of hostility and discrimination, interpretations of race relations risk overstating conflict and polarization.Footnote 4 As Paul Gilroy writes, people of color were not “only unwanted alien intruders without substantive historical, political, or cultural connections to the collective life of their fellow subjects.”Footnote 5 Careful fine-grained analysis of communities in specific periods seems to show degrees of integration. Recent initiatives to uncover local histories of people of color underscore both diversity of experience and the difficulties in drawing conclusions from limited source material.Footnote 6

The nineteenth century saw, in many ways, a hardening of racist attitudes, in relation to a range of imperial crises and in part as a backlash against the emancipation of enslaved African and African-descended peoples in many parts of the world. This was both reflected in and furthered by the rise of racial science.Footnote 7 Post-emancipation Britons may have taken pride in aiding those persecuted under what they labeled “thoroughly un-British forms of governance,” but maintained strong ideas about racial hierarchies.Footnote 8 In practice, responses to people of color arriving in Britain during the period depended on the particular configuration of the newcomer's own identity (their nationality, class, and heritage, among other characteristics), the place of their arrival/settling, and the particular historical moment. As the historical geographer Caroline Bressey suggests, there may have been a “spatial geography at work” that considered people differently depending on their particular origins. For instance, in certain situations Black people settled in Britain may have been distinguished from Black people in Africa, the Caribbean, and other parts of the empire.Footnote 9

Ned's short time in Britain allows us to chart the journey and reception of one particular African man in the mid-nineteenth century in some detail. Ned's appearance and then disappearance in the Sheffield area was a “sensation.” He thus provides an example of an individual whose “race” and therefore presence was far from “unremarkable.” The extensive newspaper coverage and correspondence with the Anti-Slavery Society's Louis Alexis Chamerovzow provide insights into how a Zulu man was received into Britain at this moment in time. By taking a microhistorical approach, we are able to trace the ways in which one individual's belonging or non-belonging was determined in conjunction with their racialization. Instead of focusing on nineteenth-century racial “theorists,” here we draw attention to the “practitioners” of racialization.Footnote 10 Placing Ned's time in England within the contexts of enslavement, indenture, colonization, and the exhibition of African people reveals the discourses and processes that shaped how Ned was treated, interpreted, and represented. Equally, it enables us to “illuminate the meanings of these large, impersonal forces for individuals.”Footnote 11 From the dense thicket of (mis)information that debated and sensationalized Ned's situation and his identity, we are able to ask questions about Ned's own experience, even if not all of these questions can be answered. Ned was a non-elite southern African who spent a significant part of his time in Britain outside London. His case thus contributes to the growing scholarship on the presence and experiences of African and African-descended people in Britain beyond the “popular geographical imagination” that typically places them in port areas, cities, or aristocratic houses.Footnote 12

Close examination of Ned's case reveals an eagerness by Britons from a range of backgrounds and in several geographical locations to “properly” identify someone whose identity was initially ambiguous and then assign him his “place.” Identified as a possible “slave” and a “poor African,” Ned's situation first generated a kind of British saviorism that cast him as a “victim.” These discourses waned as more was learned about Ned's status and his employer, and became based on judgments around his behavior and identity, all of which were repeatedly used to assign him his “correct” “place” outside Britain. Writing about the figure of “the stranger,” the literary scholar Kristen Pond describes how “the permeable boundaries that define a stranger require constant negotiation, and this negotiation often focuses on elements of collective identity.”Footnote 13 In Ned's case, we see how many people participated in this “constant negotiation,” the flexible construction and reconstruction of Ned's position, and how commentary on everything from criminality to language usage was used to portray someone as fundamentally at odds with British life. Caroline Shaw has argued that refugees, which Ned at times was identified as, “could be European or African, so long as the persecuted exemplified British ideals.” The “deserving refugee” was innocent, a “model liberal individual willing to work hard,” and their story both emphasized the “continuing tragedy facing those left behind” and “highlighted and welcomed British support.”Footnote 14 While Ned's case confirms that support for some arrivals was certainly dependent on their adherence to a “refugee” narrative, it also demonstrates how readily ideas of “race” could be utilized to accentuate a presumed inability to embody “British ideals.” In one sense, Ned's case demonstrates a “hardening” of attitudes to race on a personal scale, reflecting a shift from “saving” him to stressing his unsuitability to living in Britain.

In 2022, a short play based on Ned's life used creative storytelling to provoke audiences to consider how Ned might have experienced not only these tumultuous months in Britain, but his life before this.Footnote 15 This is one important strategy in decentering the colonial account of Ned's life, in which much is said about Ned but his perspective is recorded in print only through a couple of comments he purportedly made to individuals he met during his time in Britain. Here, while we are interested in representations of Ned, we also attempt to reflect on his lived experience in 1859 and trace some of his volition through his actions—not least his refusal to be returned to Natal—as an active participant in the attempts to decide his “place.”

In search of: “the runaway […] slave” in England

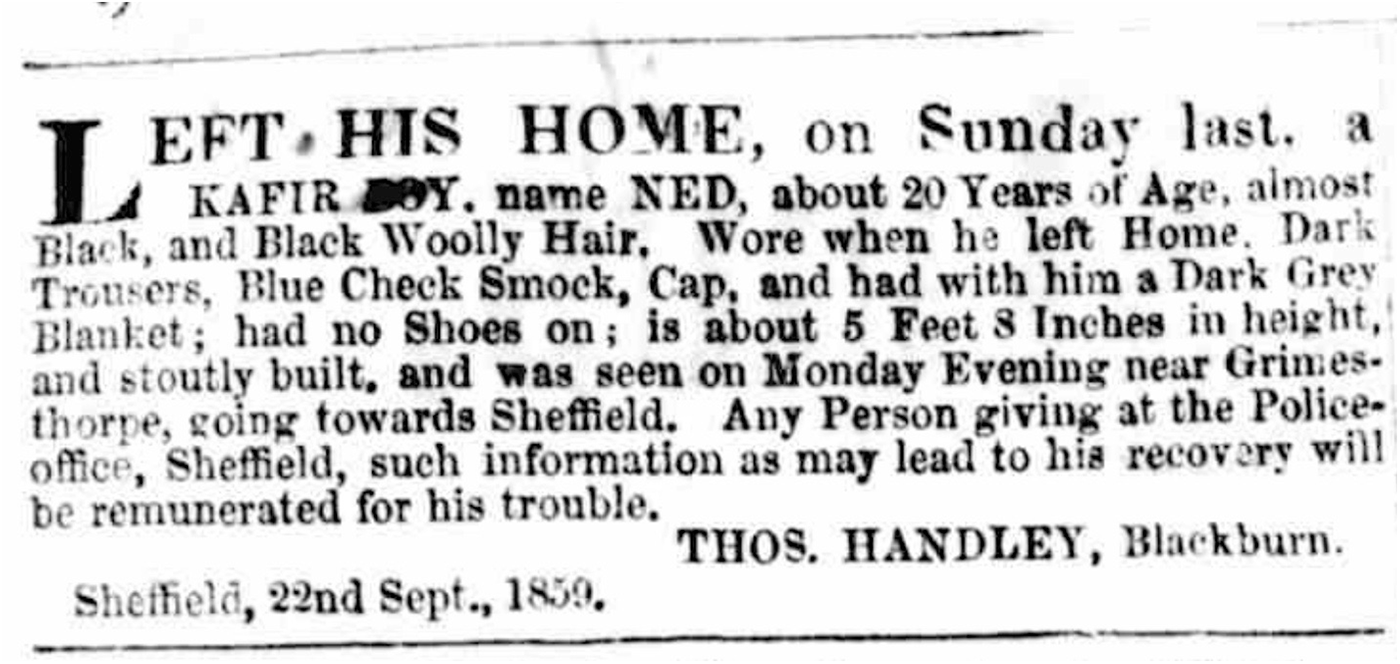

On 22 September 1859 a notice appeared in the Sheffield Daily News (Figure 1):

LEFT HIS HOME, on Sunday last, a KAFIR BOY, named NED, about 20 Years of Age, almost Black, and Black Woolly Hair. Wore when he left Home, Dark Trousers, Blue Check Smock, Cap, and had with him a Dark Grey Blanket; had no Shoes on; is about 5 Feet 8 Inches in height, and stoutly built, and was seen on Monday Evening near Grimesthorpe, going toward Sheffield. Any Person giving at the Police-office, Sheffield, such information as may lead to his recovery will be remunerated for his trouble.Footnote 16

The notice gave a striking image: a young Black man, barefoot, leaving “his home,” most likely through the wooded areas north of Sheffield. Handley's notice drew readers’ attention not least because of its resemblance to what commentators asserted was “one of those advertisements common in slaveholding America, but very unusual in free England.”Footnote 17 The similarities are clear: it provided a detailed physical description of the “runaway” that drew on racial tropes, details around his movements, offered a reward for his “recovery,” labeled him by the single name “Ned” (itself likely an Anglicization), and infantilized him by demoting him from man to “boy.” Simon Newman has shown how such advertisements were first created and used in Restoration London, demonstrating the long history of racial slavery and freedom-seeking on English soil.Footnote 18 But by 1859, the Black freedom-seeker clearly connoted US slavery. This association likely reflected popular interest in the “slave narrative” and the activities of visiting self-emancipated African Americans, such as Frederick Douglass who toured Britain in the 1840s and 1850s.Footnote 19 Moreover, particularly since the highly contested abolition of slavery in the British empire in the 1830s, anti-slavery was co-opted into ideas about Britishness. Shortly after Ned's disappearance, the Sheffield Independent reported the story that “the runaway African is a slave” brought to England “under the guise of a servant,” and dubbed the manhunt “a piece of ‘slave-hunting’ in the very heart of that country in which ‘slaves cannot breathe.’”Footnote 20

Figure 1. Notice in the Sheffield Daily News. The British newspaper archive.

The paper noted that “Mr. Handley has for a number of years been residing in some part of Africa not under English dominion, and, like other Europeans there, has had his slaves.”Footnote 21 In Britain, enslavement in southern Africa was frequently cast as a practice linked with the “Boer” population. In the claim that Handley had “evidently resided much abroad,” it is hinted that he has been “tainted” by his long residence in this particular space of empire. Despite Britain's pivotal and very recent part in Atlantic slavery, enslavement was constructed here as a foreign practice—American, African, and European. This commentary revealed Britons’ ability to deny Britain's own role in slavery. Yet Ned's case also troubled Victorians’ “spatial containment” of slavery and appeared to speak to Britons’ sense of their responsibilities over those instances of enslavement “inflicted by the British state, under its laws or by its subjects.”Footnote 22 Handley was seen to have transgressed not only the spatial expectation that England was a place of freedom but that slaveholding was contrary to British ideals and practices: “it seems improbable that a slave-holder,” argued the Sheffield Independent, “especially an Englishman, would have the audacity to bring a slave to this country.”Footnote 23

However, as early as 1 October, the Sheffield Independent declared Ned's rumored enslavement to be “injurious supposition” and reassured its readers that Handley was “an inhabitant of the British colony of Natal, where, of course, slavery is as unlawful as in England itself.” We don’t know whether this statement was due to Handley’s convincing “explanation” to the newspaper’s proprietor or his apparent litigiousness.Footnote 24 But, as opposed to representing him as a “Kafir,” which Handley had deployed in his advertisement, the newspaper now identified him specifically as a “one of these Zooloo refugees” who had escaped a civil war and entered “the service of a settler” in Pietermaritzburg, Natal, before being employed by Handley.Footnote 25 This appears to refer to the succession struggle in the Zulu Kingdom between the King Mpande's sons, Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi. In December 1856, Cetshwayo's forces had attacked Mbuyazi's, who found themselves trapped in the Thukela river basin. Thousands were massacred, or drowned attempting to escape, with a small number reaching neighboring Natal.Footnote 26 Zulu refugees in Natal were apprenticed to European colonist-settlers. Commentators emphasized Ned as the beneficiary of British benevolence. Natal legislative council member Jonas Bergtheil, who was temporarily staying in London, later described how orphaned Zulus, or those “too young to take care of themselves,” benefited from “certain protective and restrictive laws” that bound Zulus to “such Europeans as it is expected will take care of them.”Footnote 27 The traumatic and coercive conditions of Ned's recent years were, unsurprisingly, glossed over.

In reality, the apprenticeship system devised in Natal looked very different. By the 1850s, British settlers in Natal faced a “manpower crisis” as they failed to transform the growing local African population into the compliant labor force they desired.Footnote 28 Refugees offered part of a solution the British devised to this “problem.” This highlights Ned's belonging to one of the many post-slavery coercive labor systems in the British empire, alongside the 1834–38 apprenticeship system in the Caribbean and the use of laborers from South Asia in the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa. Under the 1854 Refugee Regulations, male Zulu refugees were required to enter into “apprenticeships” with European colonists. Border agents conveyed Zulu refugees to the local magistracy, and they were then “inspected by prospective employers with whom they were obliged to enter into three-year indentures at wage rates well below the market level.”Footnote 29

Against this background, colonizers’ “campaign of public vilification” characterized local Africans as the cause of the labor problem, and the deeply offensive trope of the “lazy Kafir” gained widespread popularity.Footnote 30 If Handley's advertisement had primarily connoted slavery to its local readership, something viewed as thoroughly un-British, his use of this epithet and the later identification of Ned as an apprenticed refugee, betrayed different forms of racialization and exposed coercive labor relations that could not be distanced from Britain. In fact, according to Keletso Atkins, “British Natal's earliest system of African servitude bore striking resemblance to the institution of bondage for which they had so severely criticized the Transvaal Boers.”Footnote 31 Yet, initially there was seemingly little interest in Ned as a refugee or colonial subject, something that may have raised deeper and wider questions about the treatment of such individuals and their rights in the metropole. Questions around and interest in Ned's possible enslavement persisted. Besides the advertisement, these appear to have originated with Rotherham surveyor Thomas Brady. After a “casual conversation” with Ned, Brady “believe[d] him to be a slave,” and reported that Ned had run away when he learned he was due to return to Natal. Brady communicated his suspicions to the Sheffield police, something he considered “following a dictate of humanity,” and encouraged an investigation into Ned's relationship with Handley. He also contacted the London-based British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Appealing to the Society to “interfere,” Brady hoped they would “look after the missing man” and shield Brady from the legal action Handley had threatened against him for slander.Footnote 32

Ned's case quickly gathered attention beyond the local area. On 15 October the East Suffolk Mercury was among several papers reporting that Louis Alexis Chamerovzow, the Society's secretary, “calls the attention of the public to a case of what he deems ‘slave-hunting in England,’” and dubbed Handley an “alleged slave-hunter.”Footnote 33 The Society felt that “if not slave-hunting in this country” Ned's case was “so suspicious as to warrant the Society's immediate interference.”Footnote 34 Chamerovzow quickly developed a network of informants to assist in ascertaining Ned's “condition.” The abolitionist Edward Smith advised Chamerovzow there was “no time to be lost interfering” but also stressed the difficulty in determining whether Ned was a “hired servant” or an “actual bondsman.”Footnote 35 The Anti-Slavery Society nevertheless moved to ensure that Ned was not taken to Natal against his will, having Metropolitan Police officers observe the Handleys’ embarkation without Ned and threatening proceedings against the ship's captain should Ned accompany them.Footnote 36 All the while, Ned remained missing in the Sheffield area, having “secreted himself in the woods” and “baffled every attempt to capture him.”Footnote 37

How did Ned interpret his situation? Initially, newspapers reported that “the general impression” was that Ned ran away “because he considered himself his master's slave,” and “had no desire to return to Africa with Mr Handley.”Footnote 38 As the Independent attempted to redress the slavery theory, it contested this, suggesting that Ned had wandered off in a “low and melancholy” state because he feared “he should not see Africa again,” positioning Ned as homesick.Footnote 39 Others pointed to conflict in the Handley household. In the periphrastic manner consistent across discussions of Ned, a local clergyman who had obtained information about Ned from an associate of Handley claimed a fellow servant had unjustly accused Ned of stealing, and he “feared his master would have him punished.”Footnote 40

Some weeks later, a woman who claimed to have stayed in the same inn as Ned and the Handleys stated his disappearance owed to a dispute over pay: “he had some high words with his mistress” and through tears told her that Mr. Handley had a “bad heart, bad heart.” She claimed that Ned had said that “Mr. Handley was to give him 10s. to come to England to nurse Tom and Harry [Handley], but he had not given him anything.”Footnote 41 It is notable that this is one of few sources where the author claimed to be giving Ned's account (and to be directly quoting him). The second was Bergtheil's letter to the editor of London's Daily Telegraph, which professed to give Ned's perspective of his situation predominantly based on their November 1859 conversation at Clerkenwell prison. Bergtheil claimed that Ned had experienced seasickness so severe “that he declared he would for no consideration ever again venture on board a ship,” and upon learning that the Handleys were due to return to Natal, had fled.Footnote 42

For the Anti-Slavery Society, Bergtheil's allegedly authoritative account, and that Ned claimed wages of Handley, would later “set at rest” the legal question of his enslavement.Footnote 43 But enslavement as a legal status could not, and cannot, necessarily encapsulate Ned's condition nor his perspective on his condition. If Ned was articulating that he was working for the Handleys without payment or discussed other aspects of his situation as a refugee/apprentice/servant, he may well have believed himself enslaved and/or given this impression to others. It is ultimately unclear whether Ned was (still) apprenticed, and whether he traveled to the country under some degree of coercion—Bergtheil claimed Ned “was apprenticed to Mr Handley [..] and finally agreed to accompany him and his family to England.”Footnote 44 His reasons for departing the household are also unclear. But it is possible that whatever Ned had related after his departure, others were quick to read this through the lens of enslavement, as their first encounter with the case was via an advertisement for a “runaway” Black man.

The Natal context offers other perspectives. Keletso Atkins’ work makes clear that labor relations between Africans and colonists in Natal were extremely fraught, and disputes over wages and terms of employment were endemic.Footnote 45 If Ned did willingly travel to England under the promise of payment, departed the household, and later (according to Bergtheil) looked to find another kind of employment in England, the events of 1859 may reflect Ned's attempt to assert control over his own labor. He may also have had other motives for traveling to Britain. Bergtheil claimed that Ned was “highly pleased with the prospect of seeing Europe.”Footnote 46 A number of Zulu people had traveled to Europe and returned to Natal in the 1850s, and accounts of their experiences may have been widely known. One published account of a Zulu traveler who had visited Europe for around a year as part of an “exhibition” appeared in the Natal Journal in 1858, the year before Ned left for England.Footnote 47 As the historian Sadiah Qureshi highlights, this could “taken to be the words of the Zulu or the missionary who transcribed his words and subsequently arranged for their publication.”Footnote 48 Though the account stressed the interest in exploring features of the colonizers’ country, like Bergtheil claimed, its characterization of the journey, place, and people would have also likely have created a lot of trepidation. It also suggested that the Zulu travelers had used the trip to investigate certain claims the English were making in Natal; and that the experience had given the returning travelers some status. In other words, such a trip could offer opportunities for personal and community gain.

So much had happened in the few years preceding Ned's time in England—with his flight from the Zulu Kingdom, employment in Natal, and long journey still, presumably, fresh in his mind. Although different accounts of Ned's situation and his motives emerged, their limitations in explaining Ned's disappearance are self-evident. But if none can speak for Ned, he made one thing clear: his determination not to be captured.

In search of: “the lost African” in Sheffield and beyond

Having run away mid-September, Ned was still “missing” by late October. The newspapers related that Ned was “supposed to be hiding in some of the woods in the neighbourhood of Grimesthorpe.”Footnote 49 He was sighted or encountered in various locations, and it was reported that for “several weeks” Ned had “taken up his quarters in the woods at Norton, from whence he ventured to emerge occasionally in the day-time, in quest of food.”Footnote 50 Ned was in the village of Thorpe Salvin, more than ten miles from Grimesthorpe, when he was eventually taken into police custody, after over a month “missing.”Footnote 51 This period raises questions both about Ned's experience, and local responses, during this time. The tone of the local newspapers’ reports on Ned was, if heavily patronizing, fairly sympathetic. Newspapers reported “severe frosts.” Ned had left with no shoes and minimal clothing. There was “great reason to fear that [Ned] may perish from the weather and lack of food.”Footnote 52 In an article entitled “The Lost African,” Sheffield's Independent stressed:

The African is perfectly harmless and inoffensive, so that no person need feel any fear of him, and it will be a real act of humanity to the poor creature to allay his alarm, and give him food and shelter till he can be properly provided for. We hope this explanation will [..] induce persons to interest themselves in saving the poor man from perishing by cold and hunger.Footnote 53

As the newspaper encouraged, Ned received considerable support from locals, and allegedly he was supplied with food and “charity.”Footnote 54 It was also noted that Ned was “subsisting on blackberries and such other wild fruits.” The newspaper elaborated that this was “a mode of living which of itself indicates no small amount of determination not to return,” but the image of Ned subsisting on wild fruit would also have resonated with this familiar trope in constructions of “savagery” in general and of southern African hunter-gatherers in particular.Footnote 55 Sheffield's Independent wrote: “The wild but harmless demeanour of the man excited strong feelings of compassion whenever he occasionally presented himself.”Footnote 56 If Ned was not dangerous, he was nevertheless “wild,” a “poor creature” whose vulnerability should, these newspaper reports emphasized, provoke Britons to rescue him and provide aid.

Ned was not universally perceived in this way. The sources also point to more negative experiences. The Independent reported that he had been “abused and beaten by some persons, and had dogs set upon him by others,” and was “so much alarmed as to hide himself as closely as possible.”Footnote 57 Brady claimed to have cautioned “police and peasantry” to “beware of hunting Ned or using violence,” though Brady himself was also participating in this pursuit.Footnote 58 It is unsurprising, then, that according to one commentator, “[Ned] has a real fear of being taken.”Footnote 59

In defying capture, Ned apparently defended himself in numerous encounters. Soon after he left the Handleys, when “seized by two men in a wood near Grimesthorpe,” Ned “offered so energetic a resistance that they were quite unable to detain him.”Footnote 60 When disturbed on another occasion, sleeping under a “wrapper or rug,” Ned communicated “his displeasure” and “the men, therefore, left him.”Footnote 61 And when two agricultural workers attempted to capture him, “he resisted, and adroitly seizing hold of one, threw him over the adjoining hedge.”Footnote 62 Ned also resisted persuasion. In mid-October, Ned was supplied with food and spent some time with the male servants at Thomas Jones's farmhouse. Ned “appeared quite harmless, made himself intelligible in broken English, and seemed to perfectly understand what was said to him.”Footnote 63 But when the men attempted to “induce” Ned to return to “his master,” Ned purportedly quickly “showed symptoms of fear [..] and all further efforts to prevail on him to go to Sheffield were fruitless.”Footnote 64 The pattern of interactions with Ned attest to his terror of recapture and his vulnerability, but at the same time show his resilience, resourcefulness, and determination.

Ned also had to sustain himself over this period—and reportedly appeared “haggard,” “emaciated,” and “worn out.”Footnote 65 An outcome of this hunger, Ned was allegedly seen by Hackenthorpe farmer George Hellewell with a slaughtered lamb. Hellewell explained that he had identified Ned from the newspaper coverage, and when he called him “by his name,” Ned approached Hellewell, laid his hand on his shoulder, and “motioned him to pass on.” Hellewell gave up persuading Ned to go with him, given he carried the knife used to kill the sheep.Footnote 66 The Independent speculated that “he may even be guilty of some more dangerous crime,” and characterized him as a “wild looking” “character armed with a knife.”Footnote 67 Although still describing him as a “poor fellow,” the threatening characterization was a notable shift from initial portrayals of Ned as—if not the fugitive slave—the lost, harmless African.

At daybreak, Hanging Lea Wood was “thoroughly searched” “surrounded and scoured” by “officers and some hundreds of people from the village.”Footnote 68 Long searches by “hundreds of workmen and other people in the village … proved in vain,” and locals were left to ruminate on Ned's direction of travel from footsteps in the dew.Footnote 69 Ned was captured shortly after the sheep-stealing incident, eventually “induced” to a household in Thorpe Salvin. These high levels of public involvement in the search for Ned perhaps reflected the appeal of the rewards allegedly offered for Ned's capture, or eagerness to participate in anti-slavery activity, but ultimately speak to the excitement and “spectacle” of an African man in the local area.

Many variable racializing terms were used to refer to Ned: he was described as both a “Kaffir” and a Zulu man. By the end of the eighteenth century, European commentators defined a range of southern African groups as belonging to a “race” of “Kaffirs” (or “Caffres”), and over the nineteenth century, colonists imbued this term with negative meanings “in order to legitimise the dispossession of the indigenous population.”Footnote 70 But this was not homogenous. Although their use of terminology was inconsistent, many Europeans in Natal “insisted on a distinction between Zulus and ‘Natal Natives’” for their own reasons; not least in efforts to dissuade “black racial unity” during this time.Footnote 71 Of course, Africans did not identify themselves in these terms. Historian Michael Mahoney argues that “antagonism and lack of identification” between Natal Africans and Zulus were mutual, and “People's ethnic identification would remain with their chiefdoms” until colonialism later provoked Africans in Natal “into embracing a new identity.”Footnote 72

In Britain, the term “Zulu” certainly had its distinct connotations. As historian Catherine Anderson notes, British representations of the Zulu people characterized them as “noble savages,” and emphasis on the Zulus's purportedly “martial demeanor” meant that “to many Britons of the mid-nineteenth century, Zulus [..] constituted a race of heroic warriors.”Footnote 73 British interest in the peoples of southern Africa only heightened in the mid-century. The Eighth Xhosa War (1850–53), referred to in Britain as the “Kaffir War,” drew the public's attention to the Cape Colony and the violence that British colonialism engendered. New exhibitions highlighted “tales of violence, border conflict, and British military activity,” and were “among some of the most popular forms of metropolitan entertainment.”Footnote 74 Charles Caldecott's 1853 “exhibition” of “Native Zulu Kafirs” claimed to be the first of its kind, and these spectacles remained popular throughout the nineteenth century. Zulu men, described as the “wild men of Africa,” were exhibited at the Royal Windsor Castle Menagerie during Ned's time in England.Footnote 75 Britons consumed Zulus in the 1850s as “wild men,” “novel amusements,” and “specimens” for the examination of alleged human differences.Footnote 76

The identification of Ned as a Zulu thus surely generated additional interest in his appearance in the area and added drama to his disappearance. Newspapers reported that “a ‘wild man’ had been caught”; after Ned's capture, “crowds of rustics and others thronged the premises […] in order to get a sight of the stranger.” Ned was “an object of extraordinary curiosity” and amongst his “hundreds” of “visitors” came those bearing “ordinary victuals, confectionery and sweetmeats.”Footnote 77 The Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald set out that “several people have so far sympathised with him that they will take him into their employ if allowed to do so.”Footnote 78 But, after Ned's capture, local magistrate Thomas Need wrote to Chamerovzow that:

As to an engagement in our neighbourhood I am very much opposed to any thing of the sort, because I am convinced that those who wish to engage him are influenced by very unworthy motives & would keep “Ned” as an object likely to attract customers. There are many other objections, & I quite agree with you that the best way to dispose of him is to send him back to his own country.Footnote 79

From Need's perspective, at least a degree of this public interest thus reflected an objectifying interest in Ned as a spectacle of racial “otherness”.

Despite this, the question of his condition remained important. When Ned was taken into custody by the county constabulary, “the strongest determination was shown by the crowd to resist his removal, they being under the impression that the poor fellow had no right to be deprived of his liberty.”Footnote 80 Ned was nevertheless briefly incarcerated in Eckington, something framed as a “safe keeping” measure until the Anti-Slavery Society could “send down somebody to take charge of him.” Evidence was taken “simply to justify their detention of the man.”Footnote 81 Again, there seemed to be a degree of local support for Ned and “a sum of money was subscribed on his behalf.”Footnote 82 But there was little concern voiced about Ned's own wishes. Although allegedly not enslaved, it was taken for granted that the Anti-Slavery Society was the appropriate body to “care” for him. The extensive newspaper coverage of Ned's case both allowed and was enabled by public participation in his case, and it is clear that many people physically involved themselves by searching for Ned and attempting to see him. There appears to have been a sincere local commitment to ensuring Ned's freedom, from Brady's initial concerns about Ned's enslavement to the crowd's insistence on Ned's “liberty,” which could reflect popular enthusiasm to engage in anti-slavery activity. But public interest also reflected a wide and deep fascination with Ned as an African, and specifically a Zulu, or southern African, man. Whatever the locals’ motives, Ned was chased, hounded, bribed, captured, gawked at, imprisoned, and ultimately removed.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the Anti-Slavery Society became satisfied that Ned was not legally enslaved. It seems they still had work to do in investigating “the whole circumstances of the poor fellow's case” when newspapers reported that Ned would “be taken care of by the society, or permitted to go into the service of some trustworthy person.”Footnote 83 The Society's Reporter stated in November that “we are expecting him to be placed in our hands, and trust we may find a home for him.”Footnote 84 But Need's comment that he agreed with Chamerovzow “that the best way to dispose of him is to send him back to his own country” suggests Ned was beginning to be perceived as a “problem” and Chamerovzow was contemplating Ned's return to Natal. By this point, Handley had departed England and “forgoes all claims whatever upon [Ned].”Footnote 85

In search of a specific kind of African man: humanitarians and the question of race

On 1 November London's Daily News reported that Ned “left for the metropolis on Friday,” and alleged he was “very much improved in spirits and appearance.”Footnote 86 The Anti-Slavery Society arranged for Ned to be escorted from the Derbyshire village of Eckington to London's Strangers’ Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders on West India Dock Road. During his time in London we see repeated attempts to identify a specific kind of Black man, one that fitted with contemporary racial ideas and humanitarian ideals, a stereotype in which African people, particularly those who came under the influence of missionaries and humanitarians, were expected to act in a “grateful” (meaning “subordinate” or even “submissive”) way toward the Europeans positioned as their paternalistic benefactors. While under their “care,” Ned defied these hopes and aspirations as he did not conform to the passive stereotype they searched for and, as such, was found not to belong.

In mid-nineteenth-century Britain, attitudes toward race were in flux. After the abolition of slavery in the British empire, many came to believe that the “Great Experiment” had “failed.” Events overseas—including Xhosa resistance to colonization in southern Africa and the Indian Rebellion of 1857–58—were used by some critics as “evidence” that the humanitarian “project” of “civilisation” was impossible.Footnote 87 Racial science made hardening claims about the immutability of racial difference.Footnote 88 Nonetheless, many humanitarian-minded actors both in Britain and its empire continued to operate through missionary work and organizations such as the Aborigines’ Protection Society and the Strangers’ Home.Footnote 89 Darren Reid has recently demonstrated that “humanitarian decline” was far from straightforward: some humanitarian-minded people, including members of the Aborigines’ Protection Society, became more “entrenched” in their humanitarian beliefs at the same point that others became disillusioned.Footnote 90 It was in this charged atmosphere that Ned's case was heard.

The Strangers’ Home had opened in 1857, just a few years before Ned arrived in Britain. A center for Christian missionary work, missionaries played a central role in its founding and operation.Footnote 91 The home provided information, advice, accommodation, and food for sailors while they found their next job on a ship or engineered their passage home. Its intent was to alleviate the destitution, vagrancy, and vice believed to plague transient sea-faring populations in London.Footnote 92 The home hosted people of many different origins and the press reported that “natives of India, Arabia, Africa, the Straits of Malacca, the Mozambique, and the Islands of the Pacific, have been sheltered at the Home for periods varying from one week to three months.”Footnote 93 As much as this setting potentially provided opportunities to meet other people of color, and those with similar experiences of displacement, Ned was not a seaman. Rather than providing any comfort, his placement in the Strangers’ Home was more than likely terrifying, given his evident determination not to return to Natal. Colonel Hughes, the Home's honorary secretary, assured Chamerovzow that every effort would be made to make Ned “happy & comfortable.” But by Hughes's own admission, this had not been the case. Ned had related that he “felt he was in jail and not allowed to go where he wished.” Visited by two men who conversed with Ned “in his own language,” Hughes claimed Ned's “mind was set at rest & he now appears in a much happier state than previously.”Footnote 94 But he was mistaken, and Ned soon departed the Home. As Ned later allegedly explained to Jonas Bergtheil, the cause of this was “because all the people who came to see him talked about his being put on board ship, and sent back [..] to Natal.”Footnote 95 Ned continued to be steadfast in his determination to remain in England.

Others at the Home had different explanations for Ned's refusal to stay in the Strangers’ Home. Its superintendent informed Chamerovzow that he felt “pretty well assured that [Ned] wishes to get amongst bad company in the public houses, and he has often begged for money, though none has been given him, but he has been supplied with tobacco.” The Home was “quite at a loss to imagine what has become of him.”Footnote 96 We do not know what Ned was feeling as he left the home, but it appears that he was becoming increasingly frustrated both with efforts to confine him against his will and the threats or plans to remove him to Natal. Evidently there was also a growing sense of frustration among those who had concerned themselves with Ned's case. Chamerovzow wrote critically that, since Ned's removal to London, his “conduct” had been

… far from what was desired, and notwithstanding every attempt that has been made to induce him to settle down to a civilised life, he has got worse and worse, and several times made his escape from the institution.

Ned's refusal to submit to the plans for his containment and removal were presented as a failure to adapt to either a “settled” or a “civilised” life, which may be situated in wider humanitarian narratives about the limits to which reforming those from backgrounds such as mobile pastoralists was possible. It also reflects both growing unease with the way in which Ned acted and wider patterns of the contemporaneous “disillusionment” of missionaries and humanitarians in southern Africa during this period.Footnote 97 Chamerovzow went on to express hope that, though “the man is again at large,” he might again be “captured” and returned “to his native country.”Footnote 98 Four days later, Chamerovzow appeared even more exercised by Ned, emphasizing that “notwithstanding all the precautions that were taken consistently with not placing him under bodily restraint to keep him at the ‘home,’ he has, after two disappearances, again made off.” Demonstrating a shift in Ned's representation, he continued that “He is quite wild, and the best thing that could be done with him would be to get him conveyed to Natal, and placed under the care of Mr. Shepstone, the protector of the aborigines.”Footnote 99 Chamerovzow portrayed Ned as unwilling, or unable, to respond to the many attempts to “induce him to settle down to a civilised life.” This was echoed in press coverage, which concluded that all the efforts made, “and the kindness which has [bee]n used, have, as it appears, failed to reconcile the poor [fello]w to the condition in which he was placed.”Footnote 100 Ned's refusal to be contained in the Strangers’ Home was rendered as proof of his insurmountably “wild” and “uncivilised” characteristics.

These representations of Ned's supposed lack of civilization were once again stressed during his final escape from the home, when he was eventually discovered in Highgate Wood, having again (allegedly) stolen and killed a sheep. By daybreak the “inhabitants of Highgate had got the information” about Ned's whereabouts and “a large number of people” joined the hunt for Ned in the woods. Ned was eventually “secured” by two constables “after a hard struggle.”Footnote 101 Newspapers drew attention to what one dubbed the capture of “A real live Kaffir … near Highgate” emphasizing through this degrading language the perceived extraordinary nature of Ned as a spectacle.Footnote 102 Ned was described in animalistic terms: “more like a wild monkey than a man” and almost in “a wild state of nature.”Footnote 103 This rhetoric drew on a lineage of linking African people explicitly to orangutans, current since the eighteenth century.Footnote 104 Emphasis on his agility was also used to animalize him, and also suggested his evasiveness as a criminal, now recharacterized by one commentator as “the terror of the neighbourhood” during his time in the Sheffield area.Footnote 105

After Ned was captured, he was taken to Clerkenwell House of Detention. During Ned's time here, Bergtheil visited him. As someone associated with Natal who could (reportedly) “converse with [Ned],” Bergtheil was contacted by the magisterial authorities and visited Ned at Clerkenwell “with a view of ascertaining any particulars with which I might be acquainted relative to him.”Footnote 106 Bergtheil provides the most detailed account of Ned's time in England, and authored one of the only sources professing to give us Ned's own perspective on some of the events that unfolded in 1859.Footnote 107

Bergtheil's account confirmed aspects of Ned's story already covered in the press. It reiterated that Ned was not enslaved but rather a Zulu refugee from the 1856 “sanguinary massacre” who had been apprenticed to Mr. Handley, and “finally agreed to accompany him and his family to England.” Bergtheil also made the novel claim that he had already met Ned in Durban, before his embarkation, where Ned appeared to be pleased with “the prospect of seeing Europe.” Bergtheil also reported the changed mental state Ned appeared to have undergone since then, recording that:

When I first entered his cell this morning, although he appeared to recognise me, he seemed terrified, and pretended not to understand the questions I addressed to him; but after recalling to his mind where I had originally seen him, telling him that I knew his master, explaining to him who I was, also that I knew Mr. [Shepstone], secretary to native affairs in Natal, and that if he required assistance I would properly represent his case, a broad grin stole over his countenance, and he freely answered all my enquiries I subsequently put to him.

It is notable here that Bergtheil describes that Ned “seemed terrified” in his cell, one of few statements that sheds light on what Ned might have been feeling during his time in Britain. It furthers the questions we already have about what Ned was experiencing. That Ned was allegedly “pretend[ing] not to understand” while he assessed the situation also suggests this was a tactic he deployed to navigate these situations, which he may have used in other stressful interactions such as in court and with locals. Bergtheil goes on to explain that Ned had been “horrified at finding himself chased by a number of ‘umlungas’ [white men] in uniform, who he supposed to be soldiers.” Bergtheil believed that Ned had “entirely [..] lost” his “confidence in Europeans,” who had pursued him and taken the money he was given.Footnote 108 In Bergtheil's characterization, Ned did not distinguish between the police, Anti-Slavery Society officials, or soldiers. If correct, we can imagine how Ned felt navigating the different people and organizations he encountered, who must have appeared as a host of undifferentiated “umlungas, or white people” claiming variably to help or apprehend him and all acting as obstacles to his objectives.

Although Bergtheil acknowledged these aspects of Ned's experience, and that the Handleys owed Ned wages, he alleged that Ned felt he had not been treated badly by his former master, nor at the Strangers’ Home, and he felt his crimes had been treated most leniently. According to Bergtheil, Ned's frustrations instead lay in one very particular place: his determination to avoid return to Natal owed to his terrible seasickness. When he learned he was due to return, “his fear of the voyage was so great that he abandoned his service without a single penny in his possession, without declaring his intention of leaving, or affording any trace of his whereabouts.” At the Strangers’ Home, Ned was horrified that “all the people who came to see him talked about his being put on board ship, and sent back across the sea to Natal.” According to Bergtheil, Ned felt that “everybody” was “in a conspiracy to send him—again across the sea.” Of course, Ned was correct about this; he was surrounded by other men who were also waiting to board a ship. Believing he would “be forcibly placed on board,” Ned again ran away.Footnote 109 His overriding objective was, according to Bergtheil, to stay and work in England.

Ned's case was tried at Highgate Petty sessions in a courtroom “crowded to excess,” suggesting the general public had come to gawk at what may have been perceived as another form of exhibiting a Zulu man.Footnote 110 This was reflected in press coverage of the trial. In court Ned was described as behaving “in a very wild manner,” and “in a very wild state, and who could not speak one word of English.”Footnote 111 While it is very possible that Ned was showing signs of distress or frustration in this intimidating setting and his vulnerable circumstances, this shows the racialized way that his behavior and speech were interpreted and represented. The commentary here on Ned's language skills contrasts starkly with other evidence of his facility with English. In Ned's early encounters, commentators generally remarked on his ability to both understand and make himself understood. When hiding near Sheffield he is said to have “made himself intelligible in broken English, and seemed to perfectly understand what was said to him both by Mr Jones and his men.”Footnote 112 In October 1859 a different journalist noted that “though he cannot understand all that is said to him, yet he has a sufficient knowledge of the language to make himself understood.”Footnote 113 Similarly, in November 1859 the Sheffield Independent reported that Ned and Mr. Hellewell “talked for about ten minutes, trying to understand one another”—the emphasis here reflecting the two-way nature of comprehension and communication.Footnote 114 Yet, at his trial, Ned “addressed the magistrates in his native tongue.” These difficulties frustrated the trial, delaying it “till somebody acquainted with his language could attend.”Footnote 115 This may have been intentional on Ned's part—perhaps it served to buy him time, or to ensure that he could defend himself using words he had carefully chosen. Another informant to Chamerovzow, Rev. Richard Hartley, reported that Ned “had been much with other tribes, & that he spoke a ‘mongrel language.’” Hartley believed “This may account for the difficulty he & the man I brought for Sheffield had to understand each other, though there were several words common to both.”Footnote 116 Brady commented after Ned was “secured” that “None here to understand him” and he needed “to be examined per interpreter” in London.Footnote 117 Of course, there may be many reasons for inconsistency; comprehension and communication (not least in a second language) can indeed fluctuate depending on circumstance, mental state, and accent among other factors. But it is also possible that Ned was deliberate or strategic in his communication, as Bergtheil claimed, “pretend[ing] not to understand” Bergtheil's questions until he recalled their previous meeting, when he then “freely answered all [Bergtheil's] questions.”Footnote 118

Particularly after the relocation to London, though, emphasis seems to be placed on his complete lack of comprehension. It is possible that Ned was either less willing, or due to his circumstances, less able to communicate effectively. But for commentators, Ned's language (or lack thereof) was rendered further “proof” of his “incivility” and acted as an index of his perceived “savagery.” The Anti-Slavery Society stated that Ned's allegedly limited English language skills simply provided further evidence of his unsuitability for life in England as they served as “an additional obstacle to his obtaining employment.”Footnote 119 In December, London's Daily Telegraph described Ned as “only be[ing] made to understand by signs,” and wrote that he “kept grinning and dancing with the gaoler.”Footnote 120 Further afield, the Bury and Norwich Post also described Ned dancing and laughing at the bar, stating he was “obliged to be kept quiet by force.”Footnote 121 References to “dancing” were likely informed by the tropes of display so central to ethnographic exhibitions of Zulus and other Africans. Dancing was a central part of these spectacles and helped draw in crowds. Charles Dickens's well-known reflections on “The Noble Savage” in Household Words, prompted by the 1853 exhibition, represented the Zulu people “howling, whistling, clucking, stamping, jumping” and “tearing.”Footnote 122 Dickens's argument in this essay—that “savages” should be “civilised off the face of the earth” —points to the frightening ramifications of these depictions and the power of racializing exhibitions to excite extreme responses.

Ned's widely publicized court appearance also acted as a forum for debate about Ned's future. Bergtheil attended the court as Ned's interpreter and explained he was “taking up” Ned's case as a “man without means, without a friend [..] and—worst of all—unaccustomed to our habits.”Footnote 123 Bergtheil recommended Ned be “summarily convicted” to avoid association with criminals that might harm his chances at employment.Footnote 124 Bergtheil, as well as the missionary Charles Frederick Mackenzie who was also temporarily resident in London, claimed to seek employment for Ned, themselves unable to “take care of him.”Footnote 125 He stressed Ned's suitability for domestic service explicitly, and drew on his “long experience of the Zulu character,” “stating that he will make an admirable and faithful servant.” Bergtheil drew attention to Ned's “trustworthy,” “honest,” and “wholly inoffensive” character, seemingly seeking to circumvent British expectations that an African servant would be dishonest and inherently offensive.Footnote 126 Other commentators used their personal experiences with Ned to testify to his character. “M.E.B,” the woman who claimed to have stayed in the same inn as Ned and the Handleys, emphasized to a London newspaper both Ned's unfamiliarity with English culture (“he drank from a large basin of tea… like a horse”), and his diligence as a servant, in particular detailing his “tenderness and care of a mother” toward the Handley children.Footnote 127 At the very same time Ned was represented as performing the traits of a so-called “savage,” commentators argued for his suitability for servitude, and such accounts pointed to the possibility of Ned's employment in England. But they were also used by newspaper editors to evidence “the simple, harmless qualities of this untutored child of nature,” and to argue that Ned's return to “his own country” was “a step which, in his destitute and unenlightened condition, is absolutely necessary as regards both himself and others.”Footnote 128 Ned was figured both as harmless, through his portrayal as a child-like and a feminized nurturing figure, and at the same time as a possible threat. Racialization was a malleable discourse that could hold within it multiple, shifting contradictions and could thus be deployed strategically.

Those who involved themselves with Ned's case also concurred that some kind of punishment was necessary for his crime. Chamerovzow argued “a short imprisonment, for the sake of keeping him safe until means can be found to send him to Natal, would satisfy justice and be in accordance with humanity.”Footnote 129 Bergtheil thought punishment could serve other purposes too, and that “some nominal punishment … such as gentle exercise on the treadmill,” would make Ned understand that “he must not break the law with impunity.”Footnote 130 The magistrates declined to acquit Ned of the crime, and he was committed for trial at the Central Criminal Court. Ned was taken to Newgate prison and then stood trial again before being acquitted and discharged from custody.Footnote 131

The promotion of more forceful methods to control Ned's behavior and intensifying stress on his “necessary” removal reflects a sharper emphasis on his unsuitability to life in England. This is particularly clear in comments by Chamerovzow, who had become convinced that Ned “will never do any good in this country, owing to his wild habits and utter impatience of personal restraint.” Chamerovzow again stressed the insurmountable nature of Ned's “racial” characteristics:

He is quite uncivilised, and though he says he wants to stay in this country and work, it is clear to me that he would never live under the restraints of civilised life, but would take the first opportunity of again making for the woods and resuming in England the life of Kaffir.Footnote 132

This important statement again speaks to debates in Victorian Britain about the capacity of Indigenous people from various sites of empire to “become civilised”: Chamerovzow here appeared confident in asserting that Ned's behavior was due to his “race” and thus unchangeable.

With Bergtheil's “narrative” seemingly disproving “the slavery theory,” Chamerovzow identified Handley as a “respectable trader,” reaffirmed Ned's refugee status, and explained that his claim of wages “is sufficient evidence of his having been a servant.”Footnote 133 Chamerovzow concluded from the Society's “inquiries” that “we are strongly inclined to believe that he never was so regarded.”Footnote 134 Ned was certainly not the only Black visitor from Britain's colonies who British anti-slavery activists looked to “return” when they did not behave in the desired way.Footnote 135 But strongly resonant here are the assumptions concerning “savages,” the inability of southern African peoples to “settle,” and the European characterizations of Natal's local African population as “fickle,” “fitful,” and reserving “the right to start off the kraals whenever the humor changed.”Footnote 136 Chamerovzow thus promoted the appropriate body for Ned's “care” as Natal's “protector of the aborigines,” asserting that his “proper” place of residence was Natal.

Ned's status as a refugee seemed to carry little weight in determining his possible future—he was a colonial subject (and a “troublesome” one), rather than a fugitive slave, and this led to a distinct shift in attitude. Isaac Land identifies that in the nineteenth century, Britain's “well-publicized openness to [European] political refugees” was balanced against a “quiet but vastly more interventionist approach toward seamen from Britain's own colonies.”Footnote 137 For Raminder K. Saini, certain colonial arrivals like destitute Indians “occupied an unclear space of belonging within Britain,” and revealed “contentious understandings of what rights were owed and by whom.”Footnote 138 Ned's case demonstrates an eagerness to—figuratively and literally—resolve such questions of belonging by assigning colonial subjects to their “proper” places and establishing them as both problematic and incompatible with life in Britain.

Conclusions

After his acquittal for sheep-stealing in late November, it seems that Ned went to work in Bergtheil's London household. Ned apparently “conducted himself in every way to the satisfaction of his new master.”Footnote 139 However, on 1 January 1860, a newspaper reported that Ned had once again gone missing.Footnote 140 Given that Bergtheil was “resident in London, but intends soon to return to the colony,” and Ned's well-established determination not to return to Natal, it is likely that he was reasserting his intention to remain in Britain.Footnote 141 Bergtheil had earlier stated that Ned was “utterly at a loss to understand” his position, denying Ned's clear assertion of agency over his own person. Indeed, it was Bergtheil who refused to understand that Ned was reacting to the prospect of his forcible return to Natal.Footnote 142 A few days after he left, Ned's life came to a tragic end: he was struck and killed by a train.

The Anti-Slavery Reporter claimed that the train had “pounded [Ned] to atoms.”Footnote 143 Other reports were similarly visceral and graphic.Footnote 144 Highly insensitive descriptions of Ned's tragic killing were yet another way he was made a spectacle, and news of his death was widely published. Both the popular and the anti-slavery press portrayed his death as an inevitable consequence of his racial “otherness”: it arose from “his aversion to confinement and restraint” that “prompted him to resume his wild and wandering habits of life,” and was the unfortunate but predictable outcome of “his ignorance of the perils to which he was exposed in the vicinity of a railroad.”Footnote 145 Ned's death was thus used to confirm his inability to integrate: as an African, this press coverage suggested, Ned was inherently a primitive savage and thus destined not to be able to assimilate into a rapidly modernizing and industrializing Britain.

The extant record of Ned's life leaves unanswerable questions. It is impossible to say how he experienced his departure from the Zulu Kingdom and his life in Natal, and how much choice he had in making the trip to England. Nor is it conclusive how he viewed his relationship with the Handleys, or why he left their household, and the other households and institutions he was placed in. We are left to speculate on how Ned experienced his time in the woods around Sheffield and London; his response to crowds that gathered to view him and pursue him; his encounters with the fellow inhabitants of the Strangers’ Home and his wanderings around West India Dock Road; his feelings when incarcerated in Eckington, Clerkenwell, and Newgate. We cannot know who missed him and who he missed as he traveled far from “home.” Readings of the record of his time in Britain could frame Ned as either an eager traveler to Britain who seized his opportunities to attempt to make a life for himself elsewhere, or a traumatized man experiencing coerced employment and forced movement compelled to run by fear or desperation.

What is clear is, however, is that once in Britain Ned was determined not to return to Natal. While there is nothing to suggest Ned identified with any notion of “Britishness” or staked any such claim, his experience of labor in Natal and in Britain certainly formed a basis for an attempt to remain, as did perhaps his anxieties about recrossing the ocean. The only statement that Ned (allegedly) made about what he was looking for was in regard to work and this seems to have been unequivocal: “If only the white people will take me and give me work, I do not care what wages I get!” Bergtheil claimed Ned was frustrated “that no white man will take him into his house, although he has, time after time, said that he will do any kind of work at nominal wages.”Footnote 146 If Bergtheil reported Ned’s perspective accurately, then Ned clearly longed for the economic security that would have allowed him to remain in Britain and provide him with a degree of freedom. At the same time, Ned would have been shrewdly aware that voicing his preparedness to work for “the white people” was necessary to assert his conformity to hierarchies of class, gender, and race. Isaac Land has shown that in Georgian London, “the Black Poor” resisted overseas “resettlement” projects, and adopted numerous strategies to assert both their belonging and their Britishness. Ned similarly participated in the debate over his future, making abundantly clear his determination not to return to Natal and his desire to live and work in England. But in this case, Ned's attempts to assert his belonging by working in the metropole were resoundingly rebuffed, stressing how difficult it was for individuals to “contest and reshape society's assumptions about who people are and who belongs where.”Footnote 147

Examining Ned's life helps us to understand more about British attitudes toward Black arrivals to Britain. Ned provoked a range of responses: paternalism and fascination, but also frustration, rejection, and a desire for removal. His case provides evidence of how processes of racialization were worked out on the ground in this crucial mid-nineteenth- century period, revealing the tensions and ambivalences inherent in racial ideologies and their enactment. In different situations, Ned was referred to as a “Kaffir,” “Black,” “Zooloo,” “darkie,” “Negro,” “African,” “black man,” “man of colour,’” and a “native of the tribe of the Zulu Kaffirs.” That these racial epithets, which had varied connotations and effects, were used to describe the same person over a period of a few months indicates the fluidity of “racial” difference in this period. It also demonstrates how easily Ned was cast and recast as alternately “runaway Negro,” “poor African,” or “wild Kafir” to serve a range of strategic ends, none of which was Ned's own.

R. J. Knight is a historian of slavery and Lecturer in American History in the School of History, Philosophy and Digital Humanities at the University of Sheffield, where she also leads the “Sheffield, Slavery, and its Legacies” project.

Esme Cleall is a Senior Lecturer in the History of the British Empire also at the University of Sheffield, where she works on histories of race, disability, and the body.

The authors are grateful to the reviewers and editors of this journal and their colleague Michael Bennett for their feedback, and to John Rwothomack for his important and thought-provoking work on Ned's life.