The heterosexual, White man [has it] worst. […] And the Black lesbian woman, she's doing the best.

Interviewee 5 (man, 34)INTRODUCTION

The rise of the radical right has sparked an increased research interest in radical right voters. There is a consensus that these voters share cultural grievances, mostly related to immigration, race, or ethnicity (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008). In addition, recent research demonstrates radical right voters' grievances over advances for women and LGBTQI+ people (Anduiza & Rico, Reference Anduiza and Rico2022; Christley, Reference Christley2021; Green & Shorrocks, Reference Green and Shorrocks2021; Ralph‐Morrow, Reference Ralph‐Morrow2020; Off, Reference Off2022). Further, studies on the so‐called ‘angry white man’ highlight the joint race and gender dimensions of cultural grievances (Ford & Goodwin, Reference Ford and Goodwin2010; Kimmel, Reference Kimmel2017). In contrast, other studies illustrate how radical right voters combine immigration grievances with stances in favour of women's and LGBQT+ rights (Farris, Reference Farris2017; Lancaster, Reference Lancaster2019; Spierings, Reference Spierings2020). To make sense of this partly contradictory evidence, this paper jointly studies radical right voters' grievances over immigration, gender and sexuality.

Previous research lacks an understanding of how cultural grievances over immigration, gender and sexuality compare. However, theoretically, ingroup–outgroup dynamics between natives and immigrants, men and women and cis‐hetero and LGBTQI+ peopleFootnote 1 should differ, for instance, regarding their relative ingroup and outgroup sizes and socioeconomic status, their levels of intergroup contact and cultural differences. These factors have been shown to affect intergroup relations between natives and immigrants (Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Quillian, Reference Quillian1995; Schneider, Reference Schneider2008; Zárate et al., Reference Zárate, Garcia, Garza and Hitlan2004). Yet, we know less about factors influencing men–women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations and, consequently, grievances related to women's and LGBTQI+ advances.

Methodologically, relative to the extensive quantitative research on radical right voters, with some exceptions (Ammassari, Reference Ammassari2023; Damhuis, Reference Damhuis2020; Kemmers, Reference Kemmers2017; Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2010; Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2014; Versteegen, Reference Versteegen2023), qualitative interview studies with radical right voters are scarce. In light of the contradictory evidence on radical right voters' gender and sexuality grievances, qualitative interviews can contribute to understanding different kinds of cultural grievances.

To address these theoretical and methodological shortcomings in the literature, this study analyses 28 semi‐structured interviews with voters of the German radical right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) for how radical right voters perceive and argue about discrimination, and advantages and disadvantages of natives versus immigrants, men versus women and cis‐hetero versus LGBTQI+ people.Footnote 2 It particularly focuses on the similarities and variations in arguments made in relation to the different social groups in question.

Corroborating previous research, the interviews show that unifying features of cultural grievances over immigration, gender and sexuality are the non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination against immigrants, women and LGBTQI+ people. Further, the interviewees perceive zero‐sum dynamics between advances for outgroups and losses for ingroups. Given these perceptions, advances for outgroups are associated with unfair disadvantages for ingroups. Inductive findings further reveal partly different perceptions of the kinds of gains or losses that are at stake in different ingroup–outgroup relations, resulting in arguments about material, symbolic and legal advantages. Perceptions of material (dis)advantages consider group members' socioeconomic and legal status and arguments about symbolic advantages refer to outgroups' public visibility. I further find a hitherto underresearched legal dimension of perceived (dis)advantages: Interviewees tend to perceive some outgroups as legally advantaged.

Further inductive analysis reveals an expression of what I label ‘multidimensional cultural grievances’: Some interviewees express grievances over immigration, gender and sexuality in the same argument about outgroup advantages and ingroup advantages, illustrating a joint consideration of these different cultural grievances. Finally, I find what I describe as ‘intersectional cultural grievances’. Some interviewees acknowledge that different ingroup and outgroup identities intersect and determine how (dis)advantaged a person will ultimately be. However, in their view, a person of colour (POC) and immigrant lesbian woman or trans person will be most advantaged, while a (white) German cis‐hetero man will be most disadvantaged.Footnote 3

This study illustrates parallels and differences in arguments as well as multidimensional and intersectional arguments made about grievances over immigration, gender and sexuality. By demonstrating voters' joint consideration of these grievances, the study highlights the value and need of jointly studying different cultural grievances. Based on the study's inductive findings, future research on cultural grievances may consider legal dimensions of ingroup–outgroup resentment as well as the multidimensionality and intersectionality of immigration, gender and sexuality grievances. Finally, the study contributes to the largely quantitative research on radical right voters by capturing voters' reasoning beyond what can be understood through survey data, enabled by qualitative interviews with this relatively hard‐to‐reach population.

Radical right voters' cultural grievances

Radical right voters' grievances are often explained by the feeling of being politically, culturally or socioeconomically left‐behind or worse off than others (Goodwin & Heath, Reference Goodwin and Heath2016; Hochschild, Reference Hochschild2016; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2005; Versteegen, Reference Versteegen2024; Weisskircher, Reference Weisskircher2020), the fear of falling behind in the future (Dehdari, Reference Dehdari2022; Engler & Weisstanner, Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021; Magni, Reference Magni2017; Mutz, Reference Mutz2018) or cultural threat perceptions related to immigration (Lucassen & Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). While socioeconomic and cultural grievances are often understood as separate, a growing literature recognizes their interconnections (Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017).

A number of in‐depth qualitative studies on the U.S. context illustrate the complexity of the left‐behind hypothesis. For instance, Wuthnow (Reference Wuthnow2018) describes rural U.S. communities as places where people live as ‘moral communities’ with ‘an obligation to uphold the local ways of being that govern their expectations about ordinary life’ (p. 4). The protectionism of the local community is also apparent in Hochschild's Reference Hochschild2016 study of Tea Party voters who mourn changes to their environment. On a more individual level, status loss and status protection are prominent themes in Kimmel's Reference Kimmel2017 analysis of the so‐called ‘angry white man,’ which highlights the joint race and gender dimensions of cultural grievances.

Research further suggests that radical right voters' cultural grievances go beyond anti‐immigration attitudes and include gender and sexuality dimensions. Various studies show that conservative gender and LGBTQI+ attitudes can predict radical right voting (Anduiza & Rico, Reference Anduiza and Rico2022; Christley, Reference Christley2021; Coffe et al., Reference Coffe, Fraile, Alexander, Fortin‐Rittberger and Banducci2023; Off, Reference Off2022), as well as 2016 Trump votes (Dignam & Rohlinger, Reference Dignam and Rohlinger2019; Deckman & Cassese, Reference Deckman and Cassese2019; Ratliff et al., Reference Ratliff, Redford, Conway and Smith2019; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018), and votes to ‘Leave’ in the Brexit referendum (Green & Shorrocks, Reference Green and Shorrocks2021). The grievances of ‘Leave’ and Trump voters have in turn been compared to West European radical right voters' grievances (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). According to Olsson Gardell et al. (Reference Olsson Gardell, Wagnsson and Wallenius2022), radical right Swedes perceive both immigration and feminism as threats to society. Ralph‐Morrow (Reference Ralph‐Morrow2020) illustrates that the English radical right's practices of masculinity explain its disproportionately high appeal to men. These studies suggest that gender and sexuality constitute important dimensions of radical right voters' cultural grievances that remain largely overlooked in the cultural grievances literature.

However, other research suggests that radical right voters advocate in favour of women's and gay rights and use this argument to portray immigrants as a threat to women, gays and national values of gender equality and sexual freedom (Farris, Reference Farris2017; Spierings, Reference Spierings2020). Lancaster (Reference Lancaster2019) shows that radical right voters share the attitude of nativism but hold more diverse cultural attitudes, and increasingly progressive attitudes related to sexuality. Given the contradictory evidence on radical right voters' gender and sexuality attitudes, more research is required to explain voters' gender and sexuality grievances, and how they relate to immigration grievances.

Methodologically, most studies on radical right voters use quantitative data. Yet, qualitative interviews may help scholars ‘understand complex, individual motivations’ of these voters (Damhuis & de Jonge, Reference Damhuis and de Jonge2022, p. 1). Few qualitative interview studies with radical right voters exist, which focus on voters' trajectories to the radical right (Damhuis, Reference Damhuis2020; Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2014), their channelling of political discontent (Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2010) and their experiences of stigma (Ammassari, Reference Ammassari2023). Other interview studies with (radical) right voters and activists investigate their perceptions of white people's and natives' social exclusion (Kemmers, Reference Kemmers2017; Versteegen, Reference Versteegen2023) and emphasize the role of masculinity in their beliefs (Ralph‐Morrow, Reference Ralph‐Morrow2020). This study extends this literature.

Understanding immigration, gender and sexuality grievances

This paper builds on intergroup conflict and prejudice research to understand radical right voters' cultural grievances beyond immigration and including gender and sexuality grievances. It understands cultural grievances as a result of two underlying perceptions: first, a non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination; and second, a perception of zero‐sum dynamics between ingroups and outgroups. As a result of these two perceptions, advances for outgroups in society are perceived as unfairly harmful to ingroups. In addition to native–immigrant relations, the patterns may apply to relations between men and women and cis‐hetero and LGBTQI+ people. This section outlines this framework, building on the literature on modern racism, modern sexism, post‐feminism and integrated group threat and realistic group conflict theory.

Non‐perception and justification of structural discrimination

Research shows that cultural grievances are based on a non‐perception or justification of discrimination. Bridges (Reference Bridges2021) argues that, because ‘structurally privileged groups often do not perceive themselves as privileged […], cisgender, white, middle class, heterosexual men […] all experience the stigma [of being part of these groups] as real’ (p. 684). This non‐perception of structural discrimination stands in contrast to common understandings of existing structural discrimination against POC, immigrants, women and LGBTQI+ people, amongst others. Bridges (Reference Bridges2021) thus suggests that cultural grievances emerge when people's (non‐)perceptions of structural discrimination clash with common understandings of structural discrimination.

As regards racial intergroup relations, this phenomenon is described as symbolic or modern racism (Sears, Reference Sears1988; Swim et al., Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995), which implies the belief that Black people no longer face discrimination, and/or discrimination is justified by their ‘unwillingness to work hard enough’ (Sears & Henry, Reference Sears and Henry2003, p. 260). With regard to women's discrimination, modern sexism (Swim et al., Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995) and post‐feminism (Anderson, Reference Anderson2014) entail the beliefs that discrimination against women no longer exists and society has reached gender equality (Swim et al., Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995). Consequently, post‐feminists believe ‘that the new victims of sexism are men’ (Anderson, Reference Anderson2014, p. xiii). As a result of modern racism and modern sexism, Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2014) argues that ‘the white male […] has become an injured party in national discourses […], as the one who has been ‘hurt’ by the opening up of the nation to others’ (p. 33). Scholars thus agree that a non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination can underlie cultural grievances.

Zero‐sum dynamics

Another perception underlying cultural grievances regards zero‐sum dynamics in social group relations. This perception implies that one group's gains equal another group's losses. Integrated group threat theory (Stephan & Stephan, Reference Stephan, Stephan and Oskamp2000) and realistic group conflict theory (Jackson, Reference Jackson1993; Sherif et al., Reference Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood and Sherif1961) explain inter‐group prejudice by threat perceptions, which partly derive from perceived competition. They explain racial and anti‐immigrant prejudice by dominant groups perceiving outgroups as threatening to their prerogatives: ‘Prejudice is a defensive reaction against explicit (or usually) implicit challenges to the dominant group's exclusive claim to privileges’ (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995, p. 588). Ingroup members fear to lose as outgroups win, that is, they perceive zero‐sum dynamics between their ingroup and the outgroup (Bobo & Hutchings, Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Jackson, Reference Jackson1993).

The types of perceived threats have been described as material or symbolic, where material threats concern resources or safety, and symbolic threats regard the ‘integrity or validity of the ingroup's meaning system’ (Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Ybarra, Rios and Nelson2009, pp. 43–44). For instance, studying the example of symbolic threats related to racism in the USA, Norton and Sommers (Reference Norton and Sommers2011) show that white people associate decreasing anti‐Black bias with increasing anti‐white bias, exemplifying symbolic zero‐sum perceptions.

While group threat and realistic group conflict theory are mostly applied to anti‐immigration and racial prejudice, the sexism literature suggests that similar dynamics may be at play between men and women. Off et al. (Reference Off, Charron and Alexander2022) argue that perceived competition between men and women drives young men to perceive advances in women's rights as threatening to men's opportunities. Similarly, studies find that men who perform poorly relative to women and experience personal relative deprivation are more likely to be sexist (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Harell, Thomas and Gosselin2022; Teng et al., Reference Teng, Wang, Li, Zhang and Lei2023). Further, Ruthig et al. (Reference Ruthig, Kehn, Gamblin, Vanderzanden and Jones2017) show that sexism predicts agreement with the zero‐sum notion that ‘declines in discrimination against women are directly related to increased discrimination against men’ (p. 18), and Kehn and Ruthig (Reference Kehn and Ruthig2013) find that men perceive women's status gains as coming at their own expense. Finally, Kim and Kweon (Reference Kim and Kweon2022) find that young men are particularly likely to oppose gender quotas when they have been primed to think about women's advances in the labour market as threatening. People's opposition to advances for discriminated groups may thus stem from a perception of zero‐sum dynamics between outgroups' gains and ingroups' losses.

Different groups, same grievances?

While zero‐sum perceptions may generally underlie cultural grievances related to different ingroup–outgroup relations, different ingroups and outgroups have different group characteristics. The literature considers characteristics including relative group size, socioeconomic status, the extent of intergroup contact and ethnic differences.

Group threat theory argues that group size and socioeconomic status influence natives' threat perceptions of (POC) immigrants: The larger the share of (POC) immigrants, and the higher their socioeconomic status, the more likely (white) natives perceive them as threatening (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995; Schneider, Reference Schneider2008). This is in line with realistic group conflict theory's focus on socioeconomic competition (Zárate et al., Reference Zárate, Garcia, Garza and Hitlan2004). Accordingly, relative ingroup–outgroup size and socioeconomic status should particularly affect material threat perceptions.

While these mechanisms may apply to native–immigrant relations, men–women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations are marked by different characteristics. As regards group size, women constitute roughly half of the population. In many Western European societies, foreign‐born immigrants and descendants of immigrants make up around a quarter of the population. In comparison, a small share of Western populations identifies as LGBTQI+.Footnote 4 While I do not assume that voters know the exact ingroup and outgroup sizes, the relative ingroup–outgroup sizes differ between native–immigrant, men–women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations, which may result in different perceptions of material intergroup competition. With respect to socioeconomic status, (POC) immigrants tend to have an, on average, lower socioeconomic status than (white) natives in Western societies. In comparison, women and men, and cis‐hetero and LGBTQI+ people, should have a rather similar socioeconomic status, which may lead to different material competition perceptions.

The contact hypothesis further argues that intergroup contact between natives and immigrants should decrease natives' threat perceptions (Andersson & Dehdari, Reference Andersson and Dehdari2021; Biggs & Knauss, Reference Biggs and Knauss2012), which has also been shown to hold for relations between heterosexuals and gay people (Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006). Regarding intergroup contact, while natives may not have regular contact with immigrants, and cis‐hetero people may not regularly encounter LGBTQI+ people, men and women tend to regularly be in contact. If intergroup contact reduces conflict, men–women relations should thus be marked by different dynamics than native–immigrants and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations.

Finally, ethnic differences can increase natives' prejudices towards immigrants (Laurence et al., Reference Laurence, Schmid and Hewstone2019). However, ethnic differences should not affect men–women or cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations. In contrast, in a patriarchal society (Manne, Reference Manne2017), men may perceive women's advances as threatening to the social order, resulting in symbolic threat perceptions. Similarly, LGBTQI+ people may be perceived as threatening to the heteronormative norm. While all considered group relations entail potential challenges to the predominant value system and social order, the nature of these challenges differs, which may result in different symbolic threat perceptions.

In light of these differences between intergroup relations, cultural grievances over immigration, gender and sexuality may rest on different perceptions and arguments, with implications for potential measures to address these grievances. Given the focus of previous research on native–immigrant and interracial relations, the dynamics behind grievances over gender and sexuality, and how they compare to grievances over immigration, remain under‐researched.

Multidimensional and intersectional cultural grievances

The above theoretical considerations and much literature on intergroup relations treat native–immigrant, men–women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations separately. In contrast, the intersectionality literature (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1989; Collins & Bilge, Reference Collins and Bilge2016) emphasizes the intersections of various axes of social divisions, resulting in complex assessments of power relations and discrimination. A person's race, citizenship, gender, sexuality and other attributes do not operate in separate, mutually exclusive ways. Rather, these categories jointly shape a person's experience in society. As such, societal developments regarding native–immigrant, men–women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations may also simultaneously affect a person's experience in society. I therefore argue that a person's cultural grievances are multidimensional, that is people simultaneously grieve societal changes across different cultural dimensions, and jointly make sense of their different cultural grievances rather than considering them separately.

Building on the notion of multidimensional cultural grievances, as well as the intersectionality literature and the below empirical analysis, I further introduce the notion of intersectional cultural grievances. People may not only jointly grieve societal changes across different cultural dimensions but also consider intersections between different group identities in their grievances. I define intersectional cultural grievances as perceptions of injustice that take into account intersections of different perceived ingroup disadvantages and/or outgroup advantages. Intersectional grievances mirror the argument of intersectionality scholars that different discrimination bases intersect in determining a person's experience in society. However, such grievances build on the above‐outlined perceptions underlying cultural grievances: the perceptions that outgroup discrimination does not exist in contemporary society and any advances for outgroups constitute unfair advantages over ingroups. In an intersectional approach, the more outgroups a person is part of, the more this person is perceived as advantaged. In the below analysis, I illustrate multidimensional and intersectional cultural grievances in radical right voters' arguments.Footnote 5

Case, data and method

To analyse how radical right voters perceive and argue about discrimination, and advantages and disadvantages of natives versus immigrants, men versus women and cis‐hetero versus LGBTQI+ people, I use qualitative data from 28 semi‐structured interviews with voters of Germany's most powerful radical right party, the AfD.Footnote 6,Footnote 7 Similar to other radical right parties (Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015; Alonso & Espinosa‐Fajardo, Reference Alonso and Espinosa‐Fajardo2021; De Lange & Mügge, Reference De Lange and Mügge2015), the AfD not only represents grievances over immigration but also grievances related to gender and sexuality. For instance, the party opposes gender studies, abortion and liberal sex education and emphasizes the traditional family (Berg, Reference Berg, Fielitz and Thurston2019; Doerr, Reference Doerr2021; Fangen & Lichtenberg, Reference Fangen and Lichtenberg2021). In contrast, the AfD also argues in favour of women's rights and against sexual violence, which it associates with immigration (Berg, Reference Berg, Fielitz and Thurston2019; Doerr, Reference Doerr2021; Fangen & Lichtenberg, Reference Fangen and Lichtenberg2021). While its voters should be particularly likely to hold cultural grievances related to immigration, gender and sexuality, the analysed perceptions and arguments may apply to mainstream conservative voters, too.

The interviews were conducted in August and September 2021,Footnote 8 before the 2021 national elections, in which the AfD scored 10.3 per cent. Election campaigns were ongoing during this time period. Compared to the nationally salient and highly politicized issue of the Covid‐19 pandemic that dominated the public debate across the political spectrum, other issues including immigration were less salient. Still, the AfD nationally campaigned with conservative stances on gender and sexuality issues, for instance, in the form of election posters showing slogans against the use of gender‐inclusive language. The AfD's election campaign can have influenced interviewees' opinions and arguments about gender and sexuality issues and potentially raised the perceived importance of these issues. For logistical reasons, 25 out of 28 interviews were done with residents of East German post‐Socialist federal states, where AfD support is disproportionately high and the party scored between 18 and 24.6 per cent of the 2021 votes. However, some interviews took place via phone or video call, including three interviews with West Germans.Footnote 9

The East German focus biases the sample to a population that experienced an authoritarian regime until 1989 and severe economic crises and restructuring in the 1990s after German reunification. Consequently, East Germans tend to have lower political trust and lower socioeconomic status than West Germans,Footnote 10 which are considered important predictors of radical right voting. Further, immigration rates are relatively low in East GermanyFootnote 11 and the post‐Socialist legacy entails a more progressive understanding of gender equality in the labour market, early child care and abortion (Lippmann et al., Reference Lippmann, Georgieff and Senik2020; Rosenfeld et al., Reference Rosenfeld, Trappe and Gornick2004). These factors may influence how East Germans perceive immigration and gender equality, increase the salience of material threat perceptions and reduce their support for anti‐feminist radical right ideology. Since we interviewed only three West Germans, it is difficult to assess the applicability of the findings to West Germany. While the interviewed West Germans do not noticeably distinguish themselves in their answers relevant to this analysis, a cautious interpretation of this limitation would imply that the study's findings only apply to East Germany. Because radical right support is disproportionately high in East Germany, the findings are still relevant to understanding radical right support in Germany more generally.

Before recruitment, ethical approval was obtained from the responsible ethical review board. Making use of the important role that social media plays for the radical right (Carter, Reference Carter2020; Damhuis & de Jonge, Reference Damhuis and de Jonge2022), the interviewees were recruited via social media in Facebook groups, Telegram channels and via direct Twitter and Instagram messages. Relevant groups, channels and profiles were identified by their mentions of the AfD, opposition to immigration or local city names. To avoid potential interviewees feeling stigmatized for their political affiliation (Damhuis & de Jonge, Reference Damhuis and de Jonge2022), the recruitment messages used wording such as ‘conservative’ rather than ‘radical right’ or neutral descriptions such as ‘AfD voters’ when describing potential interviewees' profiles. Potential interviewees were asked to complete a Google survey asking for any contact details while allowing for anonymity, and a preferred place to meet. A second round of recruitment was done via snowballing, which allowed recruiting harder‐to‐reach people, including those who are less active on social media, less politically active or outspoken, and women. While we aimed at recruiting ‘mere’ AfD voters, half of the interviewees were more politically engaged, for instance as party members, local town council members or participants in demonstrations (Online Appendix C lists interviewees' political activity). The more active interviewees tended to be more open to participating in the interviews, given their already disclosed political affiliation. In some but far from all cases, politically active interviewees may have biased the interviews towards more sophisticated answers that align more closely with the AfD's party communication.

The sample was recruited with the aim to reach a gender balance and cover various age groups, given the available time and resources for fieldwork. Out of the resulting sample of 28 interviewees, 20 were men and eight were women,Footnote 12 since women were less likely to agree to an interview. The interviewees were aged 18–71 and had different socioeconomic backgrounds. All interviewees are white, and, to the best of my knowledge, German citizens and cis‐gender heterosexuals. The semi‐structured interviews took between 45 minutes and 3.5 hours, depending on interviewees' talkativeness and were fully recorded upon the interviewees' consent.Footnote 13 As regards the interviewers' identity, both are white, cis‐gender (one man, one woman), young, (recognizably) West German, well‐educated and living abroad. While the interviewers' nationality, ethnicity and cis‐gender identities may have increased interviewees' trust, there were no notable effects of the interviewers' genders on interviewees' responses. Some interviewees voiced initial scepticism regarding the interviewers' West German origin and foreign place of residence. Questions about the interviewers' political views were honestly answered after the interviews to not influence the interviews. Generally, the communication was neutral or friendly.

Analytical procedure

To analyse the data, all interviews were transcribed verbatim. I then applied thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), which allows me to analyse the data within the framework determined by my research question while leaving the possibility for inductive findings to be included in the analysis. Based on the coding process, and the fact that no new relevant codes emerged during the coding of the final interviews, I am confident about the inductive thematic saturation of the data (Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Sim, Kingstone, Baker, Waterfield, Bartlam, Burroughs and Jinks2018).

To analyse interviewees' non‐perception, justification or recognition of structural discrimination in society, I first coded all mentions of gender equality, LGBTQI+ equality and racial or ethnic equality (see Online Appendix D for the coding scheme). Herein, the unit of analysis (i.e. a mention) varies between single sentences and full responses to interview questions, depending on how thematically coherent the responses were. In the next round of coding on these mentions, I coded whether interviewees recognize that structural discrimination exists or not. To approximate notions of structural discrimination, I focused on mentions of discrimination in society in general rather than individual experiences. Finally, for those mentions that recognize the existence of structural discrimination, I coded whether interviewees consider this discrimination as justified or not. If they consider discrimination to be justified, I analyse how they justify discrimination. Based on this coding scheme, I argue that those interviewees who do not recognize the existence of structural discrimination, and those who recognize but justify structural discrimination, have a predisposition to perceive outgroup advances as unfairly harmful to ingroups.

To analyse the data for zero‐sum perceptions, I coded all mentions of social groups being advantaged or disadvantaged. In a second round of coding on the mentions of social groups being (dis)advantaged, I coded which social group the interviewees referred to in these accounts, and what kind of (dis)advantage they perceived. I was then able to identify whether the perceived (dis)advantage is symbolic or material. In addition, I inductively identified a third type during the coding process: legal (dis)advantages.

Based on the coding of mentioned social groups and the type of perceived (dis)advantages (symbolic, material or legal), I consider there to be a zero‐sum perception when the perceived disadvantage of one group is comparable to the perceived advantage of the respective ‘competing’ group. Herein, ‘competing’ groups are (1) (white) natives and (POC) immigrants, (2) men and women and (3) cis‐hetero and LGBTQI+ people. Nationality and ethnicity/race are theoretically and legally distinct categories that are usually distinguished in the literature. However, in this analysis, the relations between white people and POC are understood within the framework of native–immigrant relations because the interviewees equate whiteness with German nationality and being POC with being an immigrant. Analysing white–POC relations within the framework of native–immigrant relations captures the meaning that most interviewees tend to ascribe to these social groups. In my analysis, I thus pool these groups and analyse perceptions about the relations between (white) Germans and (POC) immigrants.

Some interviewees explicitly mention several in‐ and outgroups in the same argument about perceived (dis)advantages, or generally talk about the (dis)advantages of ‘minorities’ and ‘non‐minorities’. I inductively coded these mentions as arguments about minorities or non‐minority members and analysed them as evidence for the multidimensionality of cultural grievances. Additionally, in a more developed type of argument, some interviewees consider the intersections of several in‐ and outgroup identities in determining a person's (dis)advantages in society. I inductively coded this type of argument as ‘intersectional’ and analysed these mentions to develop the notion of intersectional cultural grievances.

Overall, this study is both deductive and inductive. The analysis of interviewees' (non‐)perception and/or justification of structural discrimination, as well as whether they perceive zero‐sum dynamics in ingroup–outgroup relations constitute the deductive parts. Inductive analysis of the arguments made in relation to different ingroup–outgroup relations allowed me to analyse the similarities and differences between how the interviewees perceive the different analysed group relations. Further, the finding of a legal dimension of perceived (dis)advantages is inductive. Finally, I developed the notions of multidimensional and intersectional grievances through inductive analysis of statements that combine mentions of various ‘competing’ social groups in the same argument about advantages and disadvantages in society.

Analysis

How do the interviewees perceive and argue about discrimination, and the advantages and disadvantages of natives versus immigrants, men versus women, and cis‐hetero versus LGBTQI+ people? Overall, most interviewees do not recognize the existence of structural discrimination of various outgroups, and some justify discrimination. Further, they portray (white) Germans, men and cis‐hetero people as disadvantaged. On the contrary, (POC) immigrants, women and LGBTQI+ people are perceived as advantaged in symbolic, material and legal ways. The perceived types of ingroup disadvantages largely correspond to the perceived types of the respective ‘competing’ outgroup's advantages, illustrating zero‐sum perceptions. Some interviewees make multidimensional arguments that consider several ingroup–outgroup relations in the same line of argument. Further, some argue that different grounds of being (dis)advantaged intersect, resulting in what I describe as intersectional cultural grievances. The parallels between how interviewees perceive different ingroup–outgroup relations, and the multidimensional and intersectional ways of arguing about them, highlight the importance of jointly studying different kinds of cultural grievances.

Non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination

As above‐theorized, the non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination can set the basis for the perception of discriminated groups' advances as harmful or unfair to dominant groups. Indeed, the non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination on the basis of gender, sexuality, race or immigration background is a common theme in the interviews and similarly applies to the different kinds of discrimination.

Illustrating the non‐perception of discrimination, interviewee 20 (man, 66) states that ‘we were glad in Germany to finally have achieved gender equality, and now the women want to abolish gender equality to the disadvantage of men’.Footnote 14 Similarly, interviewee 1 (man, 60) argues about women's rights that ‘when they didn't have the right to vote yet […], they still had a reason to take to the streets, but [nowadays] gender equality has long been achieved’, again illustrating the non‐perception of gender inequalities and reflecting modern sexist and postfeminist attitudes (Anderson, Reference Anderson2014; Swim et al., Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995).

As regards intergroup relations between whites and Blacks, interviewee 24 (woman, 35+) argues that Germany has ‘other problems’ than those addressed by the Black Lives Matter movement: ‘I have never experienced that somebody was [treated] more [harshly] by the police because of their skin colour’. Considering both gender and race dimensions, interviewee 5 (man, 34) claims that ‘I am unaware of any time period […] in which a Black young woman would not be allowed to become something [in Germany]. That didn't exist. Ever’. Being asked whether Black people are discriminated against in Germany, interviewee 25 (woman, 26) answers that ‘No, I don't think so. […] Don't portray yourself as a victim. Same for the gender quota. […] People are bored, that's why they invent this. I don't think that anyone is being discriminated against’. These statements express symbolic racism (Sears & Henry, Reference Sears and Henry2003), and the latter two statements combine symbolic racist and modern sexist views.

As regards LGBTQI+ discrimination, interviewee 30 (woman, 18) claims that ‘gays, lesbians, they have always existed […] and everyone can be whoever they want to be. But if they ask for extra rights […], that clearly goes too far’. In line with Bridges (Reference Bridges2021) and Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2014), the quote illustrates that a non‐perception of discrimination sets the basis for the opposition towards measures to advance discriminated groups – a theme that is common to (POC) immigrant, gender‐ and sexuality‐based grievances. For the investigated kinds of discrimination, the perception that discrimination does not exist is most common in the interview material, compared to the justification of discrimination or the recognition of unfair discrimination (see Online Appendix D for more details on prevalence).

In addition to the non‐perception of discrimination, and corroborating the symbolic racism literature (Sears & Henry, Reference Sears and Henry2003), the interviews reveal justifications of discrimination. Some interviewees recognize the existence of (POC) immigrant and women's discrimination, albeit not LGBTQI+ discrimination. Yet, rather than considering discrimination as unfair, they partly justify it. The justifications for women's discrimination differ from the justifications for (POC) immigrants' discrimination. Women's discrimination is commonly justified by biological gender differences. For instance, interviewee 23 (woman, 34) states that

men and women are never equal, so you can never give them equal rights […]. Because a man can't breastfeed, so he can't be equal to a woman, and a woman can't work as hard as a man, physically, so they can't be equal either. A woman should be a woman and do what nature gave her.

In contrast, (POC) immigrant discrimination is justified by claims about immigrants' behaviour, for instance regarding their work ethic or criminal activities. Interviewee 3 (man, 46) recognizes that racial or ethnic discrimination exists in the housing market, as landlords tend to prefer (white) German tenants. However, he argues that

this is not as much a problem of skin color but rather a problem of personal experiences with these groups. […] If you've had problems with Black Africans in your life, you will react differently. Nobody is born racist […]. You are the sum of your lived experiences.

This quote justifies (POC) immigrant discrimination by perceptions of this group's behaviour as inadequate.

While there generally is a non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination, some interviewees recognize the existence of some discrimination as unfair. As regards women's discrimination, they acknowledge that equal pay and equal career opportunities in the labour market are not yet achieved. For instance, interviewee 18 (man, 50) states that men and women ‘are equal in many ways, but as regards their pay, there are large differences between men and women […], and that's […] not okay’. While some interviewees recognize POC discrimination as unjust, they do not refer to a specific type of discrimination. For instance, interviewee 20 (man, 66) generally claims that he is ‘glad to be white because the discrimination is smaller for a white than a Black’.

Overall, corroborating previous research, interviewees' non‐perception or justification of discrimination in society sets the basis for them to perceive advances for discriminated groups as unfair. While this is common to all analysed group relations, there are differences between them. Interviewees do not recognize discrimination against LGBTQI+ people, independent of whether they talk about homosexual, transgender or other queer people. However, they do partly recognize women's and (POC) immigrants' discrimination and partly justify it by women's biological features and their perceptions of (POC) immigrants' behaviour.

Zero‐sum dynamics

Corroborating previous research (Jackson, Reference Jackson1993; Norton & Sommers, Reference Norton and Sommers2011; Off et al., Reference Off, Charron and Alexander2022; Ruthig et al., Reference Ruthig, Kehn, Gamblin, Vanderzanden and Jones2017; Sherif et al., Reference Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood and Sherif1961), the interviews illustrate a zero‐sum perception of social group relations: If one social group wins (loses), the other group loses (wins), wherein the two groups are seen as competing. The perceived zero‐sum dynamics operate between (white) Germans and (POC) immigrants, men and women and cis‐hetero and LGBTQI+ people. The perceived advantages for one group are similar in type and substance to the perceived disadvantages of the respective ‘competing’ group. In addition to the above‐illustrated non‐perception or justification of discrimination, the zero‐sum reasoning illustrates another parallel between how interviewees view different social group relations.

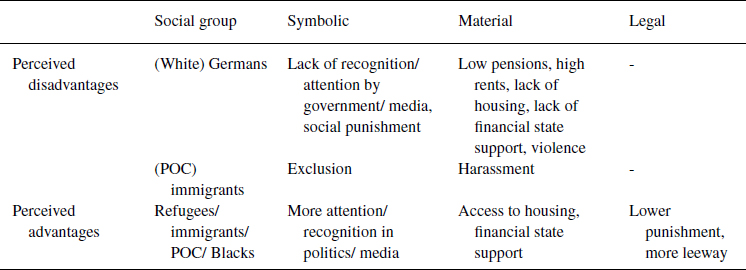

Table 1 shows how interviewees perceive (white) Germans as symbolically and materially disadvantaged, and (POC) immigrants as symbolically, materially and legally advantaged. As described in the previous section, few interviewees also recognize (POC) immigrants' discrimination. It is noteworthy that interviewees sometimes refer to (POC) immigrants in general, and sometimes only imply particular groups (e.g. refugees or Black people) in their argumentation. While these instances are sometimes difficult to distinguish, perceptions of material (dis)advantages more often refer to group relations between foreigners/refugees and Germans, while perceptions of symbolic (dis)advantages tend to refer to group relations between Blacks and whites (see Online Appendix D for more details on prevalence and social groups). This discrepancy suggests some consideration of these social groups' characteristics, in line with the propositions of group threat and realistic group conflict theory (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995; Schneider, Reference Schneider2008; Zárate et al., Reference Zárate, Garcia, Garza and Hitlan2004): Due to their legal status, refugees have had access to certain financial state support and housing that does not apply to German citizens.Footnote 15 As regards the Black population in Germany, it is impossible to pinpoint group characteristics in terms of legal or socioeconomic status. However, exemplifying a symbolic group threat (Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Ybarra, Rios and Nelson2009), the visibility of Black people and their concerns has increased in the public debate after the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. The fact that interviewees more commonly argue about foreigners' or refugees' material advantages and Black people's symbolic advantages indicates some consideration of these group characteristics.

Table 1. Native–immigrant zero‐sum perceptions

With respect to the symbolic dimension, interviewees refer to a lack of recognition and attention by the government and the media for (white) Germans and a disproportionate amount of attention given to (POC) immigrants. Referring to the relatively small outgroup of Black people, interviewee 33 (woman, 58) disapproves of Black visibility:

I have nothing against Black people […] but I would still like to see in Germany that not more Black people than white people are shown […] on advertising articles or so […]. Because I'm not racist, but I still say to myself that Germany is a country of […] predominantly white people. […] I really don't need to have that everywhere on the packaging, on baby nappies, on chocolate, or anywhere else.

As regards the material dimension, interviewees consider (POC) immigrants' access to financial state support and housing as unfair advantage, probably referring to refugees' access to such government support. For example, interviewee 10 (man, 66) complains that he ‘looked for another flat, which unfortunately the foreigner got and not [him]’. Similarly, interviewee 20 (man, 66) states that

if more is done for foreigners than for Germans, that's not okay. […] We live in an apartment with 54m2 for a rent of 650€. While the others [foreigners] live for free and receive unemployment benefits.

Further, corroborating realistic group conflict theory's propositions about safety threat perceptions (Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Ybarra, Rios and Nelson2009), some interviewees perceive violence against whites. Interviewee 1 (man, 60) perceives that ‘we are already experiencing a great deal of violence against whites in particular. And not only in the course of general crime, which of course exists everywhere, but precisely because they are white.'

In addition to symbolic and material dimensions, the interviewees perceive legal advantages for (POC) immigrants, who are perceived as having more legal leeway in breaching the law and expressing their opinions. For instance, interviewee 4 (man, 44) argues about Muslim migrants that ‘it doesn't matter what they do. They are always right’. Similarly, interviewee 5 (man, 34) claims that

I would like to be reborn as a man, but please as a dark‐skinned man. Not as a light‐skinned man. […] The doors are just open, you can behave in a completely different way. […] Even if the police stop you, you just say, ‘Are you racist?’ – ‘Nah, I'm not. Sorry. Okay, keep driving.

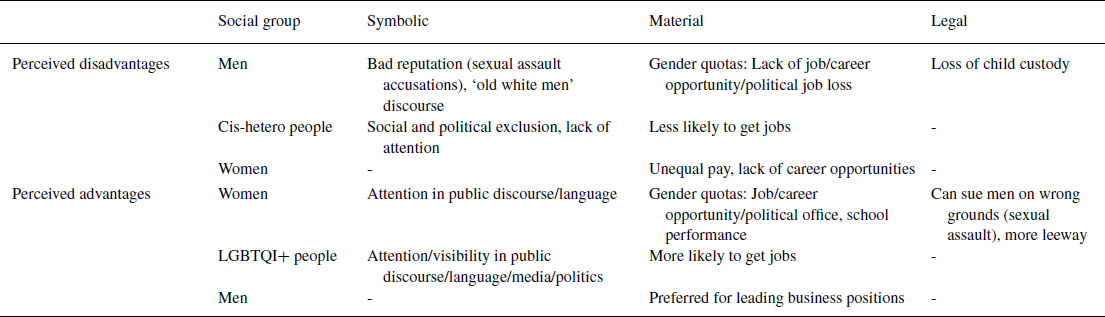

Regarding interviewees’ perceptions of men–women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ perceptions, Table 2 shows the symbolic and material and legal disadvantages that interviewees perceive for men and cis‐hetero people as well as the corresponding perceived advantages for women and LGBTQI+ people. The interviewees mostly perceive LGBTQI+ people as symbolically advantaged. Only few argue about LGBTQI+ people's material advantages (see Online Appendix D). Illustrating the perception of LGBTQI+ people's symbolic advantages, interviewee 3 (man, 46) claims

So if I now take the percentages in the population, […] and what is produced in the news […], then that is a thousandfold over‐representation. […] If I put all the non‐heterosexuals together, I get at most five percent nationwide and then that's already quite high, I think, […] but I don't have five percent of this gender news, I will soon have what feels like 60 percent that is about these topics.

In contrast, the material dimension is more prominently mentioned with respect to men–women relations. Women are mainly seen as advantaged compared to men in the labour market. Interviewee 24 (woman, 35+) claims that ‘gender equality should not mean that the female sex is preferred, as it is demanded in gender quotas nowadays’. Similarly, interviewee 2 (man, 55) argues about gender quotas in politics that ‘if the reserved seats would not replace the other seats, things would be different’, thereby highlighting the zero‐sum dynamic of gender quotas.

Table 2. Men‐women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ zero‐sum perceptions

Fewer arguments are made about women's symbolic advantages (see Online Appendix D), illustrated by interviewee 13 (man, 71) arguing that ‘because there are significantly fewer [women in politics] […], she has a few bonus points, she is allowed on the speaker's platform’. He further complains about men's symbolic disadvantages due to ‘campaigns against the old white man who is to blame for everything’.

LGBTQI+ people are thus particularly perceived as symbolically advantaged, while women are largely perceived as materially advantaged. This distinction may reflect some consideration of certain group characteristics in interviewees’ argumentation, including group size and socioeconomic status. Women constitute a large group in society, while LGBTQI+ people are comparatively few. Further, despite the prevailing gender pay gap, women's socioeconomic status is rather similar to men's, and women tend to outperform men in schools and universities. The socioeconomic status of LGBTQI+ people is more difficult to pinpoint. Corroborating the propositions of group threat and realistic group conflict theory (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995; Schneider, Reference Schneider2008; Zárate et al., Reference Zárate, Garcia, Garza and Hitlan2004), women's large group size, almost equal socioeconomic status and strong school performance may particularly result in perceptions of material advantages, especially in light of public debates about gender quotas. In contrast, LGBTQI+ people's smaller group size and less clearly defined socioeconomic status may explain why they are not perceived as materially advantaged. Rather, representing a symbolic group threat (Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Ybarra, Rios and Nelson2009), the salience of public debates about LGBTQI+ issues may explain why LGBTQI+ people are particularly perceived as symbolically advantaged.

While there is a strong perception of women being materially advantaged due to gender quotas, as described in the previous section, some interviewees also recognize women's material disadvantages and men's corresponding advantages as regards unequal pay and career opportunities. Finally, as regards the legal dimension, interviewees perceive men's and particularly fathers', but not cis‐hetero people's disadvantages. Interviewee 4 (man, 44) describes the family law as ‘unfair. As a man. As a father. […] It already is a mass phenomenon: discrimination against fathers’, thereby referring to fathers' rights to child custody.

Overall, this section shows that the interviewees perceive zero‐sum dynamics between competing ingroups and outgroups, which take mostly symbolic or material and sometimes legal forms. The similarities between how interviewees argue about the different analysed intergroup relations illustrate that different kinds of cultural grievances are based on similar reasonings. In line with group threat and realistic group conflict theory, the interviews further suggest that these perceptions are based on different social group characteristics, resulting in partly different perceptions of native–immigrant, men–women and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations. Herein, legal and socioeconomic status and group size seem to influence perceptions of material (dis)advantages. Further, public visibility seems to affect perceptions of groups' symbolic (dis)advantages for smaller outgroups. Finally, the perception of foreigners' and women's unfair advantages due to legal leeway, to my knowledge, is under‐researched and may be of interest to the study of intergroup relations more generally.

Multidimensional and intersectional cultural grievances

The analysis has so far shown that the interviewees employ similar reasonings about different cultural grievances. They most prominently argue that structural discrimination does not exist in contemporary German society, and outgroups are advantaged and ingroups are disadvantaged in corresponding ways. In addition, this section proceeds to illustrate two ways in which some interviewees jointly argue about different cultural grievances: First, the multidimensional kind of argument considers various ingroups and outgroups within the same argument. Second, the intersectional kind of argument considers intersections between different social group identities. Together, these findings illustrate that the interviewees do not just reason about different cultural grievances separately but also simultaneously consider different cultural grievances, underlining the importance of jointly studying different cultural grievances.

The multidimensional kind of argument reflects different kinds of cultural grievances within the same argument. Some interviewees mention different outgroups and ingroups or summarize them as ‘minorities’ and ‘majority’, arguing that the same kinds of (dis)advantages apply across these out‐ and ingroups. Most often, multidimensional arguments refer to the symbolic dimension of (dis)advantages: Members of various outgroups are perceived as advantaged with regard to societal attention and recognition, while ingroup members are generally perceived as disadvantaged in this regard. For instance, interviewee 22 (man, 55) argues about ‘a distortion of normality into the abnormal’, explaining that ‘the rights of small groups, slash minorities, have been placed above the rights of the majority for decades’. Similarly, interviewee 33 (woman, 58) complains that ‘minorities are really being put first’ and gives examples of symbolic cultural grievances over immigration, gender and LGBTQI+ issues: the renaming of artwork and changes in children's books made to avoid ethnic or racial discrimination, gender‐inclusive language and third‐gender toilets.

Correspondingly, some interviewees argue that members of various ingroups are disadvantaged, especially in symbolic ways. Interviewee 3 (man, 46) claims that ‘there is a danger that the middle, the core that does not belong to a minority, will completely fall behind with regard to who is taken into consideration’. He concludes: ‘I have to raise my voice very loudly to be heard’. Similarly, interviewee 22 (man, 55) perceives ingroup members as less valued than outgroups in general, suggesting that the ‘ordinary’ family is less valued than outgroups: ‘A small family –is it being valued like this social group that thinks it's special?’ These quotes illustrate a joint, simultaneous consideration of symbolic advantages of various outgroups and disadvantages of various ingroups.

Finally, in addition to multidimensional considerations of different cultural grievances, a few interviewees understand social group relations in an intersectional way, considering intersections between race, nationality, gender and sexuality in assessing how (dis)advantaged an individual is. While the intersectional argument is rarely made in the interviews, it illustrates a more developed kind of joint consideration of different cultural grievances. It is noteworthy that intersectional arguments were made by interviewees who distinguished themselves by their rather strong political sophistication.

Mirroring the concept of intersectionality (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1989; Collins & Bilge, Reference Collins and Bilge2016), in the intersectional argumentation about cultural grievances, the more outgroups an individual belongs to, the more advantaged the individual is considered. Put simply, these interviewees perceive white, German, cis‐hetero men as least advantaged in society, while (POC) immigrant, queer women are perceived as most advantaged. To exemplify the notion of intersectional cultural grievances, talking about who has it worst in society, interviewee 5 (man, 34) claims that ‘the heterosexual, white man’ has it

worst. And then it's always reduced when one of these characteristics is gone. So the heterosexual white German woman, she's also doing badly, but a bit better. And then him [points to an immigrant man], an old, dark‐skinned man, he's also doing badly or well on about the same level. […] And the Black lesbian woman, she's doing best.

Similarly, interviewee 4 (man, 44) describes a ‘pyramid of victims’, in which those who can ‘portray’ themselves as victims of discrimination are most advantaged by measures to advance discriminated groups. Thus, interviewee 4 claims that old white men are at the bottom of this pyramid, being unable to claim measures to advance their group in society, and therefore most disadvantaged in society.

Intersectional arguments comprise symbolic, material and legal dimensions. Exemplifying the symbolic dimension, interviewee 5 (man, 34) argues that people combining outgroup identities are regarded as ‘divinity’ while white heterosexual men are considered less valuable in society. As regards the material dimension, interviewee 4 (man, 44) applies intersectional reasoning to resource allocation, arguing that economic success is no longer determined by individual effort but rather by how many outgroup identities a person can claim. For those who combine most outgroup identities, he further argues that ‘it doesn't matter what they do. They are always right’, expressing a perception of advantages based on greater leeway.

Multidimensional and intersectional arguments about cultural grievances illustrate a joint consideration of different cultural grievances, thereby highlighting the need to jointly study people's cultural grievances. Intersectional cultural grievances further illustrate that interviewees' zero‐sum perceptions go beyond dichotomous social group relations between (white) natives and (POC) immigrants, men and women or cis‐hetero and LGBTQI+ people. Some interviewees view these group relations as intersecting and therefore arrive at more complex assessments of who is (dis)advantaged.

Conclusion

This study has analysed how radical right voters perceive and argue about discrimination, and advantages and disadvantages of natives versus immigrants, men versus women, and cis‐hetero versus LGBTQI+ people. It contributes to understanding immigration, gender and sexuality dimensions in radical right voters' cultural grievances. Empirically contributing to the mostly quantitative literature on radical right voting, the study employs qualitative interviews with voters of the German radical right party AfD.

As theorized in previous research, the interviewees' cultural grievances over immigration, gender and sexuality are illustrated by two arguments: first, the non‐perception or justification of structural discrimination in society; and second, the perception of zero‐sum dynamics between outgroups' advances and ingroup losses. Given that many interviewees perceive zero‐sum dynamics in ingroup–outgroup relations, and either do not perceive or justify discrimination, they consider any outgroup advances as unfairly disadvantageous to ingroups. The fact that these grievances are based on either a non‐perception or a justification of discrimination implies different underlying rationales. Any measures aiming to address these grievances may thus engage with both rationales.

Corroborating previous research, the interviews suggest that radical right voters differentiate between social group relations between (white) natives and (POC) immigrants, men and women and cis‐hetero and LGBTQI+ people by considering certain group characteristics. Specifically, they seem to consider groups' size and socioeconomic and legal status in arguing about material (dis)advantages, and different groups' public visibility in arguing about symbolic (dis)advantages, resulting in partly different considerations for different ingroup–outgroup relations. Considering that interviewees' perceptions of men–women relations are similar to perceptions of native–immigrants and cis‐hetero–LGBTQI+ relations, the interviews do not provide evidence for an effect of intergroup contact on perceptions of ingroup–outgroup relations. Overall, the interviewees distinguish between symbolic, material and legal types of social groups' gains and losses. The perception of legal (dis)advantages remains underresearched and may be further explored in future research.

Building on the interviews, I propose the notions of multidimensional and intersectional cultural grievances. I demonstrate that voters jointly consider different cultural grievances in their argumentation rather than treating them separately, which I describe as an expression of multidimensional cultural grievances. Multidimensional arguments ascribe the same kinds of advantages to various outgroups and disadvantages to various ingroups, typically referring to symbolic (dis)advantages. Additionally, some voters consider the intersections of different social group identities, which I describe as an expression of intersectional cultural grievances. Some interviewees acknowledge that different ingroup and outgroup identities intersect and determine how (dis)advantaged a person will ultimately be. In their view, a (POC) immigrant lesbian cis‐woman or trans person will be most advantaged, while a German (white) cis‐hetero man will be most disadvantaged. Taken together, the multidimensionality and intersectionality of radical right voters' social group perceptions underline the importance of jointly studying immigration, gender and sexuality dimensions of cultural grievances.

This study contributes to the literature on radical right voters and cultural grievances. Understanding the multidimensionality and intersectionality of cultural grievances, as well as the parallels and differences between different cultural grievances may inform future research aiming at studying cultural grievances beyond anti‐immigration attitudes. Finally, by using qualitative interviews to study the relatively hard‐to‐reach population of radical right voters, the study empirically contributes to the largely quantitative field, thereby improving the understanding of complexities and nuances in these voters' perceptions. While this study comes with the shortcomings of most interview studies, namely the lack of representativeness and generalizability, it may thus inform future operationalizations of cultural grievances in the study of radical right voters.

Acknowledgements

I thank the interviewees for their generous time and trust. I am grateful to Luca Versteegen for his collaboration with the fieldwork and the brainstorming sessions that led to this paper. I further thank the editors and anonymous reviewers, Johanna Kantola, Amy Alexander, Nicholas Charron, Marta Fraile and other members of the CSIC‐IPP in Madrid, Eva Anduiza, Daniel Balinhas, Juan Pérez, Leire Rincón and other members of the Democracy, Elections and Citizenship research group at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Elin Naurin, Carolin Rapp, Jana Schwenk, Josefine Magnusson, Ann Towns, Andrej Kokkonen, Lena Wängnerud and Leon Küstermann for their very helpful comments at different stages of writing this paper.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of the data (i.e. transcripts from individual interviews), and due to the importance of preserving anonymity, supporting data cannot be made available.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table D1: Mentions of recognition, justification and non‐perception of structural discrimination

Table D2: Perceived grounds of disadvantages

Table D3: Perceived grounds of advantages

Table D4: Intersectional arguments about (dis)advantages

Table E1: Mentions of recognition, justification and non‐perception of structural discrimination by age and gender

Table E2: Perceived grounds of disadvantages by age and gender

Table E3: Perceived grounds of advantages by age and gender