Introduction

On 1 July 1992, Senderistas – members of the rebel Partido Comunista del Perú–Sendero Luminoso (Communist Party of Peru–Shining Path) – killed 18 Indigenous men and cut off the braids (plaits) of their female kin in Huamanquiquia, an Andean village of about 422 residents at that time, located 60 km south of the city of Ayacucho, also known as Huamanga.Footnote 1 The Senderistas had entered the village in two groups. The first arrived around 3.00 p.m., dressed in military fatigues, heavily armed. They were pretending to be soldiers of the Peruvian military in order to seek out those villagers who, along with the army, had confronted five guerrillas on 5 June 1992, killing four of them and letting one (later referred to as ‘Americano’)Footnote 2 escape. To carry out this deception, the guerrilla leaders chose two Senderistas, including Americano, to act as prisoners, dressed in plain clothes. They accompanied the guerrillas, their heads dirty, faces bloodied and hands bound. After summoning the villagers to the main square, the intruders asked them to identify the supposed prisoners. A total of 19 men and 17 women admitted to recognising the one who had escaped. The intruders took these 36 individuals into the courtyard of a local kindergarten, supposedly to receive official congratulations and gifts. They then ordered the other villagers to return to their homes. Believing that their visitors were indeed soldiers, local leaders directed some women to cook for them. About 40 villagers, including the women who were to prepare a meal for the intruders, gathered in the courtyard of the kindergarten. Most were married couples; some women carried small children or newborns, and a few were pregnant.

At sunset, the intruders split the roughly 40 villagers – those who admitted to recognising the prisoner and those who were cooking – by gender. Another group of dozens of men and women in plain clothes arrived at that moment and surrounded the kindergarten. It turned out that the intruders were not soldiers but Shining Path insurgents. Fear, terror and panic ensued. The Senderistas, including those in military fatigues and the supposed prisoners, began slaughtering the male villagers with sticks, stones, machetes, knives and axes. The unarmed men could not defend themselves. Some perished quickly, and others suffered in agony. The Senderistas hacked 18 men to death in front of their wives and children, who attempted to defend them, crying desperately, as two widowed survivors later declared at a public hearing of Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación, CVR) in Huamanga on 9 April 2002.Footnote 3

The Senderistas then turned on the women. The commanding guerrilla leader ordered a young female guerrilla (later referred to as ‘Mariela’) to kill them. She refused to carry out the order and looked to the second-in-command for support. Following an altercation between the two guerrilla leaders, they agreed to punish the women by cutting off their long braids instead. After hitting, kicking and beating the women, the Senderistas cut off their hair using knives and machetes. They then locked the women and their children in a classroom. The Senderistas spoke of setting fire to the victims and ordered a guerrilla to look for kerosene or petrol. At this point, the women broke a window in an escape attempt. Most got away, but the elderly and those with children remained behind. A man who had hidden among the women when the guerrillas began to separate their victims by gender also escaped. Once the Senderistas noticed the women’s escape, they threatened to kill the remaining women unless they paid for their lives with chickens and other goods. While some Senderistas went to pick up the payment, others looted the dead men’s houses. Finally, they left the village, shouting ‘Long live Chairman Gonzalo’, referring to Abimael Guzmán, the Shining Path’s founding leader, who led the 1980–92 Maoist-inspired insurgency against the Peruvian state.

This article examines this massacre as a local case study of an atrocity against Indigenous Quechua-speaking peasants in Huamanquiquia. Based on first-hand accounts by Indigenous survivors and former Shining Path guerrilla fighters, I assess how this incident targeted Indigenous men and women differently and what the haircutting incident meant for the guerrilla fighters and their victims. The nature of this massacre follows the most common pattern of armed conflicts, where men are the primary targets, whereas women are often victims of rape and sexual violence.Footnote 4 In Huamanquiquia, the men were the primary targets, and concurrently, the women became, by extension, victims of the haircut punishment amid terror and the killing of their husbands. In this case of a gendered atrocity experienced differently by men and women, this article demonstrates the different lenses of gendered violence and how the Senderistas knew about the symbolic dimensions of haircutting but underplayed them. While this atrocity reflects some well-known patterns seen in other armed conflicts, it is shaped by two key factors specific to the time and place: first, particular understandings of the significance of hair within broader Andean cosmologies; second, tensions within the Shining Path movement at a key juncture in the war.

I argue that women experienced haircutting violence as a crime against their human body–soul integrity, one that is understood to provoke endless suffering in the afterlife, according to their Andean worldview. Most of the Senderistas who perpetrated the massacre were from nearby communities; they spoke Quechua and, as such, understood this worldview enough to intend the haircutting as something that could disturb these women even after death – not counting the physical, social and moral impacts and disruptive legacies of trauma and stigma resulting from the actual act.Footnote 5 Yet the rebels underplayed the symbolic power of haircutting when they cut off the women’s braids. Tension arose between the guerrilla leaders, as to whether or not to kill the women. Though in the end allowing the women to survive prevailed, enforced haircutting was a symbolic way of killing them.

The article is structured as follows: I start with contextual, theoretical and methodological considerations before examining the understanding of haircutting in the Andean context. I then provide some background on the Senderistas involved in the massacre in order to counterpose their explanations and contradictions against the experiences and perspectives of their female victims, particularly regarding the enforced haircutting. I close by summarising the case study.

The Shining Path Insurgency in Context

The Shining Path arose in Ayacucho as a small splinter Maoist party in the 1960s that started its armed struggle in the town of Chuschi, not far from Huamanquiquia, by burning ballot boxes on election day in May 1980, just as the country returned to democracy after 12 years of military dictatorship.Footnote 6 From Ayacucho, it expanded across the Andes and the Amazon basin, from where it sought to encircle Lima and other cities in its campaign to force ‘the collapse of the state’.Footnote 7 The party leaders were mainly educated, middle- and upper-class mestizos from urban centres, while the rank and file comprised urban labourers and rural Indigenous peasants.Footnote 8 The first offered the second an armed rebellion in order to take power, correct economic disparities and create an egalitarian society. The leaders also offered a gendered message for the inclusion of women in leadership roles and amongst the rank and file.Footnote 9 Women comprised about 40 per cent of Shining Path militants and 50 per cent of its Central Committee.Footnote 10 Nonetheless, women and girls faced numerous barriers inside the movement, including patriarchy, misogyny and sexual abuse by male guerrilla leaders.Footnote 11

Huamanquiquia and many other highland communities around the basin of the Pampas and Qaracha rivers in south-central Ayacucho region became the main theatre of the Shining Path’s early guerrilla actions. Located on the southwest bank of the lower Qaracha river, Huamanquiquia is a peasant community and district in Fajardo province. It comprises three localidades: Tinca, Patara and Uchu. The village of Huamanquiquia itself has about 700 inhabitants today. They speak Quechua (some are bilingual Quechua/Spanish speakers) and support their families by farming, trading and temporary wage labouring. Before the government sent its security forces to oppose the guerrillas in January 1983, the Shining Path had varying support in Huamanquiquia, from passive endorsement to active support. Notably, the young supported the rebels by joining their guerrilla army. Local experience of state neglect, fear and intimidation provide the motivating factors for their support.Footnote 12 However, the Shining Path’s increasing authoritarianism, such as the killing of local representatives, prompted a growing rejection of the insurgents. In February 1983, the Huamanquiquia villagers agreed in a meeting to reject the Maoists; they recorded their decision in their Libros de Actas (Community Minute Books).Footnote 13 The rebels retaliated by killing the four representatives who wrote the agreement. Huamanquiquia mobilised neighbouring communities to establish an anti-guerrilla resistance coalition called the ‘Pacto de Alianza entre Pueblos’ (People’s Alliance Pact). This Alliance was in operation from 1983 to 1986, and resulted in the Shining Path’s expulsion from the area.Footnote 14 The Alliance was then suspended until its reactivation in 1992 (see below).Footnote 15

In Huamanquiquia, the government also had blood on its hands, given that its security forces carried out their own reign of terror against anyone suspected of sympathising with the Shining Path. In August 1984, the army committed the gruesome massacre of at least 30 detainees from Huamanquiquia and its localidades. The military burned the bodies of some of the detainees and disappeared others while keeping two girls alive in order to rape them before killing them.Footnote 16

During the Shining Path’s first wave of violence (1983–4), the rebels and the military targeted Indigenous, poor and rural peasants, resulting in thousands of fatalities, mainly from Ayacucho. By 1989, the army had changed its strategy by allying with the peasantry instead of committing random violence against locals, quickly reducing the guerrilla movement in Ayacucho. In response, Guzmán called on his followers to achieve ‘strategic equilibrium’, the theoretical stage before the final offensive in Mao’s theory of ‘people’s war’, by increasing guerrilla actions across the country to seize cities. That campaign prompted a second wave of violence (1989–92). The Maoists terrorised Lima by bombing and killing political rivals and residents, while, in rural Ayacucho, they continued to kill local representatives and intimidate villagers.

Defeated in 1992 with the capture of Guzmán, the Shining Path declined rapidly. President, then dictator, Alberto Fujimori (1990–2000) took credit for this military victory. However, Fujimori’s trial over charges ranging from corruption, abuse of power and human rights violations showed that the rondas campesinas (community self-defence patrols) played a crucial role in the guerrillas’ demise.Footnote 17 Upon Fujimori’s resignation, a transitional government established the CVR (2001–3) to investigate past human rights abuses committed by the state and the two rebel groups, the Shining Path and the Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru (Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, MRTA), during the two decades of Peru’s internal armed conflict (1980–2000).Footnote 18 In its Informe Final the CVR estimated that 69,280 Peruvians had been killed or disappeared during the conflict, mainly poor, rural and Quechua-speaking people. Over 40 per cent of the victims were from Ayacucho, the conflict’s epicentre. The Informe concluded that the Shining Path was responsible for over half the killings and the government for over a third, while the remainder of the dead were victims of local militias or MRTA rebels.Footnote 19 Killings by the Shining Path are at the highest level of guerrilla culpability for violence found by any truth commission report for any of Latin America’s Cold War-era conflicts. The 1992 massacre and haircutting punishment in Huamanquiquia are the most notorious examples of its brutality.

Mass Atrocity and Forcibly Cutting Off Women’s Hair in Armed Conflicts

Much has been written about the Shining Path’s atrocities, but mainly taken from its leadership’s discourses and its victims’ accounts.Footnote 20 To understand the Senderistas’ violence and its aftermath, the sources analysed must encompass the perspectives of the guerrilla militants and their local supporters.Footnote 21 They also need to incorporate Indigenous cultural understandings of mass violence and its effect on the Indigenous people. This research builds on these sources by explaining what happened in the 1992 massacre and its aftermath – as a historical process – and how both victims and victimisers remember it – as a historical narrative. As Michel-Rolph Trouillot states, human beings are always both actors and narrators in the overlap between the historical process and historical narrative in the production of history.Footnote 22 By bringing together Indigenous and Senderista perspectives, I examine the massacre in Huamanquiquia as a gendered atrocity that impacted differently on men and women.

The task of trying to understand the Senderistas’ decisions and actions is impossible if our attention is focused on the fact of their savagery, such as that practised in Huamanquiquia, where a massacre and mass violence were perpetrated. Jacques Sémelin proposes a ‘rational approach’ to understanding massacres and thinks of them as a ‘process’ and not as ‘insane’ actions.Footnote 23 The author argues that massacres involve an organised method of ‘destruction for submission’ or ‘destruction for eradication’ of civilians and their properties, which is liable to change according to the circumstances and perpetrators’ will in a particular cultural context. This argument leads him to define the ‘massacre as a form of action that is most often collective and aimed at destroying non-combatants’ (emphasis in original).Footnote 24

The massacre in Huamanquiquia constitutes an example of Sémelin’s notion of the destruction process because the perpetrators targeted non-combatants and their properties by looting them. This massacre also had a theatrical/performative dimension on two levels. On the first level, the guerrillas entered the village camouflaged in military uniform acting as army patrols and, after being selected for the operation, followed a previously prepared script/plan. The Shining Path had used this tactic against civilians since the early years of its insurgency to identify and punish individuals who had betrayed them or collaborated with government security forces. On the second level, the massacre in Huamanquiquia represents what Philip Dwyer and Lyndall Ryan suggest as ‘public, performative acts in which the body serves as a kind of stage on which suffering is inflicted. The victim thus becomes part of a perverse morality play, of sorts, in which the mutilated body serves as a warning to others.’Footnote 25 Rather than mere retaliation, the Senderistas aimed to impose their political power by inflicting terror on those who survived and witnessed the slaughter of their loved ones, so that nobody would rise against the movement.

Additionally, the massacre in Huamanquiquia involved the forcible cutting off of women’s hair. Forcibly cutting off women’s hair is often understood as punishment, oppression and public humiliation in opposition to women’s gender, social status, or religious beliefs.Footnote 26 Most studies on the gendered dimension of the Peruvian conflict focus on sexual and gendered-based violence against women perpetrated primarily by government security forces.Footnote 27 The Shining Path also committed violence against women and girls, but this still requires further research.Footnote 28 For instance, the use and practice of the forcible cutting off of women’s hair remains understudied. The CVR barely mentions this case as a humiliating punishment inflicted by the Shining Path.Footnote 29

In other armed conflicts, scholars have explored how armed and non-armed actors shaved the heads of women who collaborated with the enemy as a method of punishment, degradation and even dehumanisation of victims. During the Irish War of Independence, both sides to the conflict carried out violent haircutting assaults on Irish women for their indiscretion or disloyalty, thereby sanctioning and dishonouring them in the context of the patriarchal practices of the period.Footnote 30 Throughout and following the Spanish Civil War, women who resisted Franco’s Nationalist forces faced the systematic brutality of having their heads shaved and being forced to ingest castor oil – so that they would soil themselves – in order to be seen as transgressors of public and private morality according to Catholic traditions.Footnote 31 At the end of World War II, French women accused of sexual involvement with the occupying Germans endured a humiliating act of head-shaving in public as a violent and punitive act that damaged their physical integrity and provoked psychological suffering.Footnote 32 As in Franco’s Spain, the violent, sexual and public humiliation of women was a ritual process of cleansing the nation of its immoralities and restating the virtues of a virile and regenerated France.Footnote 33

The haircut punishment in Huamanquiquia was not a public spectacle as it had been in early twentieth-century Spain and France. However, it was not an isolated event: the Shining Path publicly cut off the hair of adulterous women – and even men – during its early insurgency campaign, as explained below, with similar effects, including humiliation and trauma. The Huamanquiquia case-study explains the haircutting punishment as a result of tension between guerrilla leaders amid the massacre. Based on interviews with male and female Senderistas, including Mariela, who disobeyed her commander’s order to kill the women, I argue that they display contradictions about their actions and responsibilities; some denied punishing women by cutting off their hair, while others admitted it, arguing in justification that they deserved it for collaborating with the enemy. From this viewpoint, the Senderistas approved of sanctioning and dishonouring women. The interviews show the division between the lower- and middle-ranking militants, between the leadership and grassroots. For instance, Mariela’s decision to disobey her commander displayed her pragmatism and humane consideration within an authoritarian project like the Maoist insurgency. Yet she played down her action, reasoning that hair grows back, and that these women would be able to continue with their lives. However, the victims understood the event differently, and their experiences were painful.

From Indigenous perspectives, i.e. Indigenous people’s ways of knowing and being, the haircutting incident had cultural and religious implications. In the Andean Indigenous worldview, the whole human being (mind, body, spirit and emotion) is considered interconnected to the family, community, land, territory and all living entities; therefore, cutting off people’s hair entails a crime against the integrity of the human body–soul, provoking endless suffering in the journey to the afterlife.Footnote 34 Based on this viewpoint, I argue that the forcible cutting off of women’s hair entailed the mutilation of their physical bodies and that it had social, gender, moral and psychological effects because it happened amid the terror and fear that they experienced during the killing of their male kin, which they witnessed. The haircutting thus involved different forms of physical attack, including torture,Footnote 35 beatings, kickings and injuries inflicted with sticks, knives and other weapons. It was also an act of humiliating and sexualising assaults against women. All of the above resulted in psychological impacts on the women, with trauma that extending to their children.

Sources and Methods

This article calls primarily on oral history interviews with former Senderistas involved in the massacre and Indigenous women who survived it. I carried out archival research at the CIMCDH-DP, Lima (see note 3), which preserves the archive produced by the CVR. The CVR’s team gathered 16,917 testimonies, mainly from victims, throughout the country. They collected dozens of testimonies in Huamanquiquia and coastal cities, where some villagers fled before and soon after the massacre. I visited Huamanquiquia repeatedly for over a decade, from 2008 to 2018, to complete shorter research trips and carry out extensive fieldwork for my doctoral dissertation on Indigenous peasant resistance to the Shining Path. I have a special relationship with Huamanquiquia because I grew up amid the conflict in one of its neighbouring communities. This connection and my fluency in Quechua helped me to conduct long-term ethnographic fieldwork in Huamanquiquia and oral history interviews with about 15 Indigenous women who were victims of the haircutting punishment during the massacre. These women were primarily Quechua speakers who became widows after losing their husbands. I refer to them indiscriminately as ‘widowed women’ or ‘widows’.

The CVR also collected testimonies of imprisoned Senderistas, including of Mariela, introduced earlier. She gave her testimony from Ayacucho’s Yanamilla prison in 2002. In her account, Mariela introduced herself as a repentant guerrilla who had not killed anyone during her time as a militant and revealed her involvement in cutting off the women’s hair during the massacre. After her release from prison in 2008, I had the chance to interview her. Over the following decade, she introduced me to her brother Fernando and other former comrades. I interviewed seven former guerrilla militants, four of whom participated in the massacre. Most of the seven Senderistas spent years in prison, and only Americano, who survived the confrontation on 5 June 1992, remains in hiding.

Interviewing former Shining Path guerrillas requires the rejection of demonisation if we are to try to understand them in human terms. In this way, I developed a certain degree of empathy with them, which is inherent to understanding them. An objection may arise about empathy for the perpetrators. ‘Explaining is not excusing; understanding is not forgiving’, Christopher Browning states in his work on transforming German police officers into mass murderers of Polish Jews in 1942. Browning then suggests understanding the perpetrators in human terms in order to construct a complete picture.Footnote 36 Of course, a humane approach to understanding Shining Path perpetrators does not mean exonerating them or failing to condemn their brutality. Instead, I traced how former guerrillas acknowledged their decisions and actions over time without defending or denying their atrocity. It is in that spirit that I interviewed those who were involved in the massacre in Huamanquiquia. From Shining Path bottom-up perspectives, the interviews illuminate tensions between personal and ‘party line’ assessments and provide a comprehensive understanding of why and how the mass violence had different effects on men and women, as in Huamanquiquia, particularly in respect of the haircutting punishment against women.

Hair and Punishment in Andean Society

In the Andean cosmovision, hair is not just a natural extension of the living body; it has implications in life after death that differ from Christian ideas. To explain this in detail requires understanding the relationship between body and soul in the Andean notion of living and dying. As Catherine Allen argues, unlike in the Western life–death and body–soul dichotomies, ‘for Andeans, all matter is in some sense alive, and conversely, all life has a material base’.Footnote 37 The souls of ancestors interact reciprocally and indirectly with living humans: the former attempt to protect the latter, even intercede with deities on their behalf; conversely, the latter need to care for the former in their perilous journey to find their ancestral origin. The journey can be unsuccessful for individuals who have committed hucha, the Quechua word for ‘sin’, which is ‘a burden that the soul must cast off before it can leave this life properly’, or it would continue to animate the rotting body.Footnote 38 Unlike in the Christian belief system, hucha is dense, heavy energy that constantly interchanges with sami, light and refined energy. The runakuna, meaning human beings, maintain balance and harmony between these opposing energies through reciprocal practices between social, natural and supernatural forces. Runakuna only exist because of their kinship with their environment, transcending the nature–culture dichotomy. Both human beings and non-human entities, such as places and objects, have their own animu, meaning soul, spirit, mood, energy, vitality and encouragement.Footnote 39

In this worldview, hair has symbolic power in the living body and endures beyond death. ‘Hair, growing spontaneously from our bodies’, Allen argues, ‘is another manifestation of the life force and should not be discarded indiscriminately’.Footnote 40 Doing this is a hucha for Quechua speakers. To prevent committing this sin, they carefully save and burn their hair and nails, too, to avoid regretting it later by being forced to search for pieces of their body after death. Not taking care of lost hair can also affect people in their lifetime, such as when somebody – a sorcerer, lover or envious neighbour – takes someone’s hair for malicious purposes. Animals like birds can also collect hair for their nests; someone whose hair has been used in this way can experience headaches and dizziness.Footnote 41 In accordance with all these beliefs, the morning after the massacre, the shorn women collected their hair and then burned it. In this way, they saved their hair from risky situations and from hucha.

In the past, a salient example of punishing women by cutting off their hair was for the crime of adultery. In Sarhua, a village neighbouring Huamanquiquia, the leaders carried out symbolic penalties against adulterers and other offenders by whipping them and cutting off their hair. As Olga González says, ‘Although cutting hair off, as a punishment for adultery, was not practiced anymore, older Sarhuinos remember it had been.’Footnote 42 However, the Shining Path revived and even expanded corporal punishment (whippings and haircuts) as part of its moralising campaign in Andean communities.Footnote 43

From its inception and as part of this moralising campaign, the Shining Path aimed to create a new order by applying punitive justice against its enemies, including corrupt leaders, cattle rustlers, wife-beaters, womanisers, adulterers and others they considered social miscreants.Footnote 44 The Senderistas started with a warning, followed by enforced haircutting and other physical punishments,Footnote 45 eventually ending with execution. The rebels usually gathered locals together in the village square and held ad hoc trials in public to try the defendants. Andean peasants often approved of non-fatal punishments of defendants but never agreed to their murder; their approval was further evidence of their active participation in the Shining Path’s ‘popular justice’. Testimonies collected by Peruvian anthropologists confirm these shared practices between the locals and the Maoists.Footnote 46 Once the Maoists started killing, however, locals became disenchanted, prompting them to reject the insurgents. In reaction, the Shining Path began to kill anyone who opposed the revolution.

The insurgents punished victims with whipping and haircutting, sometimes before killing them. Many of the testimonies recorded by the CVR described how the Maoists killed women by shooting, hanging and even attempting to set them on fire after cutting off their hair.Footnote 47 They used the haircutting punishment due to its impact on women’s sexuality and gender identity. As I expand on later with Mariela’s testimony, the Senderistas understood the symbolic power and sociocultural value of women’s hair. Like other Andean women, Mariela wears her hair long as a gender expression of her female and sexual identity, and she acknowledged that most Andean women of all ages wear their hair long and in braids.Footnote 48 Indeed, this is not just a hairstyle: it primarily represents a woman’s marital status. Married women usually wear two braids, while single women are more open to wearing only one braid, more than two braids, or indeed no braids at all. An older woman, as she starts losing her hair due to aging, incorporates yarn into her braids to lengthen and thicken the hair. Forcibly cutting off women’s hair attacks their social and gender status in a violent and punitive demeaning action.

The Senderistas in Huamanquiquia

The Shining Path suffered from significant internal tensions, which shaped incidents of mass violence, as illustrated by the 1 July 1992 massacre in Huamanquiquia. But before examining these tensions, background information about the Senderistas who led and/or were involved in this massacre is required. After being expelled from Huamanquiquia and nearby communities due to the 1983–6 successful anti-guerrilla coalition known as the Pacto de Alianza described above, a new generation of Senderistas returned to Huamanquiquia on 13 December 1989, slaughtered the village’s mayor Narciso Campos and prohibited villagers from burying his body.Footnote 49 This is further evidence of the Senderistas’ understanding of the Andean worldview of mortuary rituals, as they banned Narciso’s funeral in order to disturb his journey to the afterlife.

The local guerrilla leaders involved in Narciso’s murder were those who planned and led the 1992 massacre. Omar was the first-in-command, also known as the political commander, and Pablo was the second-in-command or military commander. Omar had completed only elementary school, and Pablo was an Economics student at a private university in Lima. Other middle-level and rank-and-file members were often less educated and Quechua descendants, like Riber, who, along with Omar, were first-generation militants from the Pampas river valley. Pablo was of a new generation of Senderistas who recruited many young students, including Mariela (the one who refused to kill women during the massacre). Before joining the movement, Mariela had been a high-school student in a small village near the Fajardo–Lucanas border. Pablo also recruited Mariela’s brother, Fernando, a former Physics teacher at Lima’s César Vallejo pre-university academy.

By 1992, Omar and Pablo had appointed Graciela and Mario, former university students in coastal cities, as the head of a guerrilla unit to regain peasant support in Huamanquiquia and nearby communities. The unit also included combatants Americano, mentioned above, Evelyn and teenage recruit Vilma. The latter five Senderistas were from nearby towns in Fajardo and Lucanas provinces. They had been campaigning at the recently established high school in Huamanquiquia to recruit students and regain local support until they left for a brief period of political and military training in April–May. However, given the Shining Path’s increasing incursion into Huamanquiquia and its localidades, the local leaders assembled to reactivate their People’s Alliance Pact on 31 May 1992. They agreed to reinforce their lookout system by alerting Alliance members via messenger runners called chaski to warn of guerrilla incursions.Footnote 50 At the end of the assembly, all the participants signed the agreement in their Minute Book – the leaders with their stamps and signatures and the illiterate with their fingerprints.Footnote 51 As the Huamanquiquia villagers expected, the five Senderistas returned to the high school a few days later. Immediately, two chaski runners left for the nearby military base to seek military support. Early the next day, an army patrol transported by helicopter landed in Huamanquiquia. A combined peasantry–military force confronted the five guerrillas, who had remained near the village. The soldiers killed Graciela with dynamite; her comrades had quickly hidden. Members of the Alliance found Mario and Evelyn within a few days and killed them, too. They also captured Vilma and handed her over to the military. Only Americano managed to escape; he later returned with his comrades to seek revenge.Footnote 52

To carry out their vengeance, the guerrilla commanders concocted a theatrical plan. First, they ambushed a convoy on 19 June 1992, killing an officer and some ten soldiers who were escorting five provincial politicians, who died by explosion or gunshot.Footnote 53 Next, the commanders chose their toughest-looking combatants. They dressed them in the military uniforms of the deceased, making them look like an army patrol in order to confuse the villagers and trick them into identifying those who had killed their comrades during the earlier confrontation. The chosen combatants rehearsed their military roles before entering Huamanquiquia. Among the first group of combatants dressed in military fatigues were Riber and Fernando, along with the two supposed prisoners, including Americano. Mariela and her commanders, Omar and Pablo, arrived in the second group, dressed as civilians.

The following section examines tensions between the Shining Path’s ideology and the Indigenous belief system, as well as contradictions within the guerrilla movement that resulted in the infliction of a gendered atrocity, i.e. the forcible cutting off of the women’s hair.

Hair Grows Back: The Senderistas’ Account

The Shining Path’s Maoist ideology was often discordant with the Andean people’s worldview. Even though the party’s principles claimed to fight for peasant liberation, in reality the Senderistas used their weapons against Indigenous peasants rather than protecting them from government security forces. The Shining Path’s class-struggle politics did not value the Andean people’s ethnicity or Indigeneity and often despised Indigenous politics, expectations and cultural practices. If they used the Quechua language and referred to Andean culture, it was mainly for political propaganda to gain peasant support. Nevertheless, lower-rank Andean Senderistas and their peasant supporters retained their Indigenous cultural understandings and practices or combined party principles and Andean religious/ritual practices in the daily life of guerrilla action and survival. The ideology was necessary but not as crucial as combatants’ pragmatism, kinship ties, friendship, humanity, solidarity and reciprocity, among other Andean practices. Maoist ideology may have performed well for the party leaders and middle-cadre militants but it gradually faded in significance as it descended to the lower-rank Senderistas and peasant supporters;Footnote 54 their ideological training and revolutionary commitment also changed over time.

According to Fernando, ‘Some combatants maintained traditional beliefs and customs from the old society that they were destroying but which were helpful in certain situations while building the new society.’Footnote 55 Likewise, Mariela said, ‘If some were faithful, they put their faith in God or the Pachamama [Mother Earth]; that belief would take care of them, and that would dispel their fear in certain actions like confrontations with the enemy.’Footnote 56 Native Quechua speakers, Fernando and Mariela grew up within an Indigenous agropastoral family and peasant community in southern highland Ayacucho. Despite being siblings, Fernando and Mariela followed different rural/urban bilingual Quechua–Spanish educational careers before joining the Shining Path; nevertheless, not only did they know the Andean belief system, but they also practised it at a young age. For instance, Fernando believed in coca leaf divination, an ancient Andean practice for providing guidance, clarity and healing, and Mariela recalled that she took care to keep her hair long in her childhood, following the Andean cosmovision explained earlier. Later, as guerrilla fighters, they understood these beliefs to be part of an immemorial oral tradition ‘without scientific support’, as Mariela’s Maoist commanders told her. Even Mariela embraced modern Maoist ideology; she combined it with her pragmatic and traditional values. She knew that cutting off hair was full of symbolic power, but downplayed it to save the lives of the women, disobeying her commander’s order to kill them.

Besides the tension between the Shining Path’s ideologies and Indigenous beliefs, an internal contradiction within the guerrilla group also prompted the gendered atrocity outcome. Interviews with former guerrillas reveal that cutting off the women’s hair was unplanned and had emerged amid the killings. Male insurgents, such as Riber or Fernando, denied cutting off women’s hair or justified it, playing down its impact on them. ‘We didn’t touch the women’, Riber said.Footnote 57 In the same way, Fernando told me that he remembers only separating victims by gender and locking women in the classroom. Both admitted that they shot a woman as she ran away from the classroom. ‘Only that woman died’, Fernando reported (though in fact she survived).Footnote 58 Even while insisting that they had not cut off the women’s hair, they argued that these women deserved such punishment for collaborating with the military. Mariela, the repentant female guerrilla who defied her commander Omar’s order to kill women, is the only person to admit to her actions and accept responsibility for cutting off the women’s hair.

Mariela’s decision to defy Omar was an unexpected moment of disobedience and occurred as he tested her willingness to kill in action. Such a decision differs from how media and some scholars represent the role of women in the Shining Path: as self-disciplined militants who often fired the coup de grâce and killed without mercy.Footnote 59 In contrast, Mariela’s role in the massacre sheds light on her pragmatic and perhaps more humane decision. She saved the women from death, but she still had to take action to appease Omar. Mariela then cut off the women’s braids, which, for the victims, had a devastating impact on their lives.

According to Mariela’s testimony to the CVR, the women had participated only indirectly in the previous confrontation between the guerrilla unit and the peasant–military alliance force; thus, they would be punished but not killed. She then explained why the Shining Path had tried to kill the women. After her arrest in 1995, Mariela declared to the police that the party had wanted to kill the women because they were soplonas, snitches or police informers.Footnote 60 In her 2002 CVR testimony, she also spoke of the women collaborating with the army in providing food. Furthermore, in her interviews with me, she said that the women collaborated with the military by revealing the guerrilla unit’s hiding place and preparing food for soldiers. Mariela added that although the women had agreed to oppose the Shining Path, they had not participated in a military confrontation. She said the guerrilla leaders believed that women should die or be punished for their support for the uprising against the Shining Path. Indeed, in other situations the Shining Path selectively executed women considered soplonas, and those who provided food, water and lodging to counter-insurgent forces.Footnote 61

Mariela explained how the women had cooked for the army after the confrontation during which her comrades had died. ‘It wasn’t that they [the women] should have to pay with their lives, because if we arrived and said, “You know what, make some food for us” they would make it’, Mariela declared to her CVR interviewers. She defied the order arguing, ‘I’m not going to do it. I’m not going to carry out that order, unless it’s some sanction or punishment, I don’t know, maybe whip them, I don’t know, but they don’t need to pay with their lives.’Footnote 62 For her, these women were humble peasants who had prepared food out of fear or compassion. Omar swore at her for not obeying his orders. She then went to Pablo, the second-in-command, who agreed with her. According to Mariela, Pablo supported her because he also did not want to kill the women. She mentioned that it was his humanity that ultimately prompted him to oppose Omar’s decision to kill the women. A dispute between the two guerrilla commanders erupted. The victims heard part of their discussion. They panicked and tried to escape. In the end, Pablo prevailed and said to Mariela, ‘Just do whatever you want!’Footnote 63

After getting support from Pablo, Mariela went to the women and at first frightened them: ‘He told me to kill you, and I’m going to kill you.’ The women screamed in desperation, pleading, ‘No …!’ But she told them, ‘I’m going to save you; I’m not going to kill you.’ Mariela was the first to start cutting off women’s hair, followed by her comrades; they used mainly with knives and machetes. ‘On some, I cut off one braid; on others, two’, she said. ‘Well, their hair would grow back … I basically gave them back their life’, she said in her CVR testimony. Finally, she thanked Pablo and reproached Omar: ‘I was lucky that the military commander was a good person; he wasn’t like many whom I’ve seen who were brutal, practically bloodthirsty.’Footnote 64

However, the tension between the two guerrilla commanders was not just about their humane or bellicose personalities. They had political and ideological differences as well. Fernando said, ‘Omar was not very interested in ideological training; he was guided by his own ideas to a certain extent. Pablo, on the other hand, studied and tried to apply more Marxist principles. That was the origin of their differences. Omar was not concerned with conceiving things scientifically; sometimes, he saw things as distorted, but he was good militarily.’Footnote 65 Even his military skill was significant: ‘He needed ideological and partisan understanding’ because ‘the party commands the rifle, the rifle must never be allowed to command the party’, Fernando stated, rephrasing Maoist principles.Footnote 66

Returning to Mariela, it had not been part of the plan to kill the women, much less cut off their braids. Instead, this was a way to assuage Omar’s anger, and she had to cut off the women’s braids to prevent him or someone else from killing them. As explained earlier, Mariela recognised the cultural, symbolic and gendered value of women’s hair in Andean society, as did both the other perpetrators and the victims. However, the Senderistas downplayed the haircut punishment that took place during a mass atrocity because they thought that this kind of punishment was a symbolic way of ‘killing’ women. In the end, Mariela’s proposal prevailed, though she underlined that in no way was it her intention to humiliate or dishonour women. ‘It was simply an action to protect them, to get out of that altercation between the two commanders’, she said. Mariela focused on the physical punishment and played down the haircutting as ‘something that was not going to hurt them’.Footnote 67 Still, as I will explain later, the impact of this action on the women was devastating.

Furthermore, Mariela blamed Omar for all the atrocities, exculpating Pablo. Like Fernando, she elucidated the difference between the two commanders. ‘Omar was more militarejo [bellicose], while Pablo was the opposite’, she said. As a former Indigenous peasant from Ayacucho, ‘Omar felt a little discomfited by Pablo’s theoretical knowledge. Omar felt like he was less, felt jealous of Pablo.’ As a former university student educated in Lima, Pablo was better educated, politically and ideologically, than Omar. Officially, Omar was the political commander but, in reality, Pablo did the political work because he was closer to the so-called ‘masses’, and was able to politicise them. ‘When Omar was with the masses, they didn’t give all their attention to him; instead, they welcomed Pablo.’ The masses recognised Omar’s bellicosity, and sometimes his presence frightened them. Conversely, ‘when Pablo stood before the masses, he was charismatic, and Omar wasn’t’.Footnote 68

Mariela said that there was a power struggle going on between the two commanders over who had more authority in the party: ‘They did not get along very well.’ She guessed that ‘Omar was afraid of losing power’, and sometimes ‘they looked like enemies’. Their dispute about killing the women in the massacre illustrates this power struggle. Omar insisted on killing all the women for having fed the soldiers. Pablo opposed the killing by arguing, ‘Show me a document, a quote, where Marx, Lenin or Chairman Mao states that people have to die for feeding the enemy.’ Omar had no grounds to argue otherwise: ‘Despite everything, Pablo won the argument.’Footnote 69

As Mariela understood the Shining Path’s ideology, a struggle was taking place between two ideological directions regarding the decision whether or not to kill the women, the right direction and the wrong one. The correct direction meant the party line, depicted by Pablo, who challenged the bellicose attitude exemplified by Omar. ‘If the wrong decision had prevailed, the lives of 17 women would have ended’, she reasoned.Footnote 70 In brief, Mariela argued that the reason for the cutting off of the women’s braids rather than killing them lay in the contradictions between the commanders in the immediate context of the massacre and her intention to save the women’s lives.

In this situation, the guerrilla commanders’ disagreements were displaying the internal contradictions within the middle- and rank-and-file members of the Shining Path. Miguel La Serna and Orin Starn shed light on how these militants challenged the absolute power of Abimael Guzmán.Footnote 71 Equally, lower-rank members did the same against their guerrilla commanders, as Mariela’s actions illustrate.

I tried to contact Pablo, through Mariela, to talk about his point of view on the massacre, but he refused to speak with me. She told me that Pablo blamed Omar for all the atrocities. ‘That savage must be asked, why has he done that atrocity?’, Pablo said to Mariela. ‘That bastard who has destroyed everything. The outcome today could have been otherwise.’ She said that he was angry and left her saying, ‘I don’t want to know or hear anything about this ever again.’Footnote 72 Pablo condemned Omar’s atrocities but refused to countenance his own responsibility. I also asked Mariela how to contact Omar. She told me that he had died shortly after his release from prison in 2008.

In the end, I asked Mariela: What happened to her after the massacre? Was there any disciplinary sanction? Did she criticise herself for having disobeyed her first-in-command? What did her comrades say about her decision and action? Did they agree with her or criticise her? She said that she had not been sanctioned, but there had been some criticism by comrades because of her inability to kill the women. She explained that some militants carried out indiscriminate killing following the orders of their commanders.

If you kill without saying anything, then you are firm because you have a warrior spirit, but if you don’t do that, after all, in the [debriefing] meeting[s] they tell you that you have the soul of a rabbit, a heart of butter, I don’t know what else they say to you. So, if you are soft, you have no firmness, you are appeasing the enemy.Footnote 73

Mariela was thus seen as a ‘tender’ woman, with an ‘angelic’ soul, that ‘melted like butter’ when put to the killing test, all terms that ultimately referred to ‘tenderness’.

The narratives of Mariela and others shed light on how former Senderistas balance or negotiate personal and party-line explanations. Unlike the middle- and high-ranking Senderista leaders, who often provide ideological visions and political analyses of their guerrilla warfare, former grassroots supporters are likelier to tell their personal experiences, recognising or justifying their past violent actions. As in the case of Mariela, who acknowledged her decisions and actions in cutting off women’s hair, others, like Pablo, are still unable to talk willingly about their personal responsibilities and the crimes they committed, blaming instead, in the case of Pablo, his first-in-command, Omar. Occasionally, like Riber or Fernando, they justify their brutal actions as revenge before admitting their crimes in situations like cutting off women’s hair. By so doing, these militants followed their leadership’s rhetoric, while moving gradually from denial and justification to acceptance of the atrocities that they had committed.

It Is Not Just Hair: The Shorn Women’s Account

This section turns to the women’s accounts of how they experienced and understood the cutting off of their hair following the massacre of their loved ones. Mariela played down the impact of her actions with the argument that the women’s hair would grow back soon, and justified her role in arguing that she saved their lives; but it was not just a question of hair for the shorn women. As a gendered repression against women, the haircutting happened amidst terror and slaughter of their male kin, combined with torture and other forms of physical punishment and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, bringing about psychological and social impacts in them and their children. Of course, hair grows back, but such experiences persist throughout the women’s lives, visible in the scars of their bodies and living on in traumatic memories.

The Shining Path assaulted the women by cutting off their hair after killing their male kin. Men remain the primary breadwinners in agrarian societies like that of Huamanquiquia. Most women marry before the age of 20 and quickly have children. At the time of the massacre, the married women, anxious about the fate of their husbands, wanted to be with them when the first group of rebels, disguised in army patrol, picked their 36 victims in the village’s main square. When the intruders asked the villagers if they knew the supposed prisoners, most men admitted to this: they immediately recognised the man who had escaped the previous confrontation. While some women denied knowing him, others hesitated. Even so, the women (mainly the married ones) confirmed knowing the prisoners because they did not want to be separated from their husbands. ‘How can you separate me from my husband? I’m going to go with him to wherever it may be’, Alejandra told the rebels, as she testified at the CVR’s public hearing in Huamanga (see Figure 1).Footnote 74 She then held herself tightly to her husband, the president of Huamanquiquia’s Junta Directiva Comunal (Community Board of Directors). Even though he denied knowing the supposed prisoner, the rebels selected him as a local figure of authority. The couple had four children. She was four months pregnant at the time of her husband’s death, had a baby on her back and her two-year-old daughter in her arms. At age 33, Alejandra became a widow. She also was the first target of the haircutting punishment.

Figure 1. Alejandra, first on the right, at the CVR public hearing in Huamanga, 9 April 2002. Photo by the CVR.

Serafina clung to her oldest son, Doroteo, the breadwinner in the family. Serafina was already a widow; the Senderistas had killed her husband in 1981.Footnote 75 When Doroteo was included in the group of one of the 19 men who admitted to recognising the supposed prisoners, Serafina claimed also to know the supposed prisoner as an excuse to be with her son. In the courtyard to which the Senderistas had taken their victims Serafina was with her 11-year-old daughter, Mercedes, and her daughter-in-law, Benita, Doroteo’s wife, who was about to give birth to their first child. Benita pleaded for mercy for her husband when the rebels hit him with an axe. ‘They kicked me and threw me to the ground along with the other women; I watched my husband in agony as he lay on the ground and they slaughtered him with an axe’, she said.Footnote 76

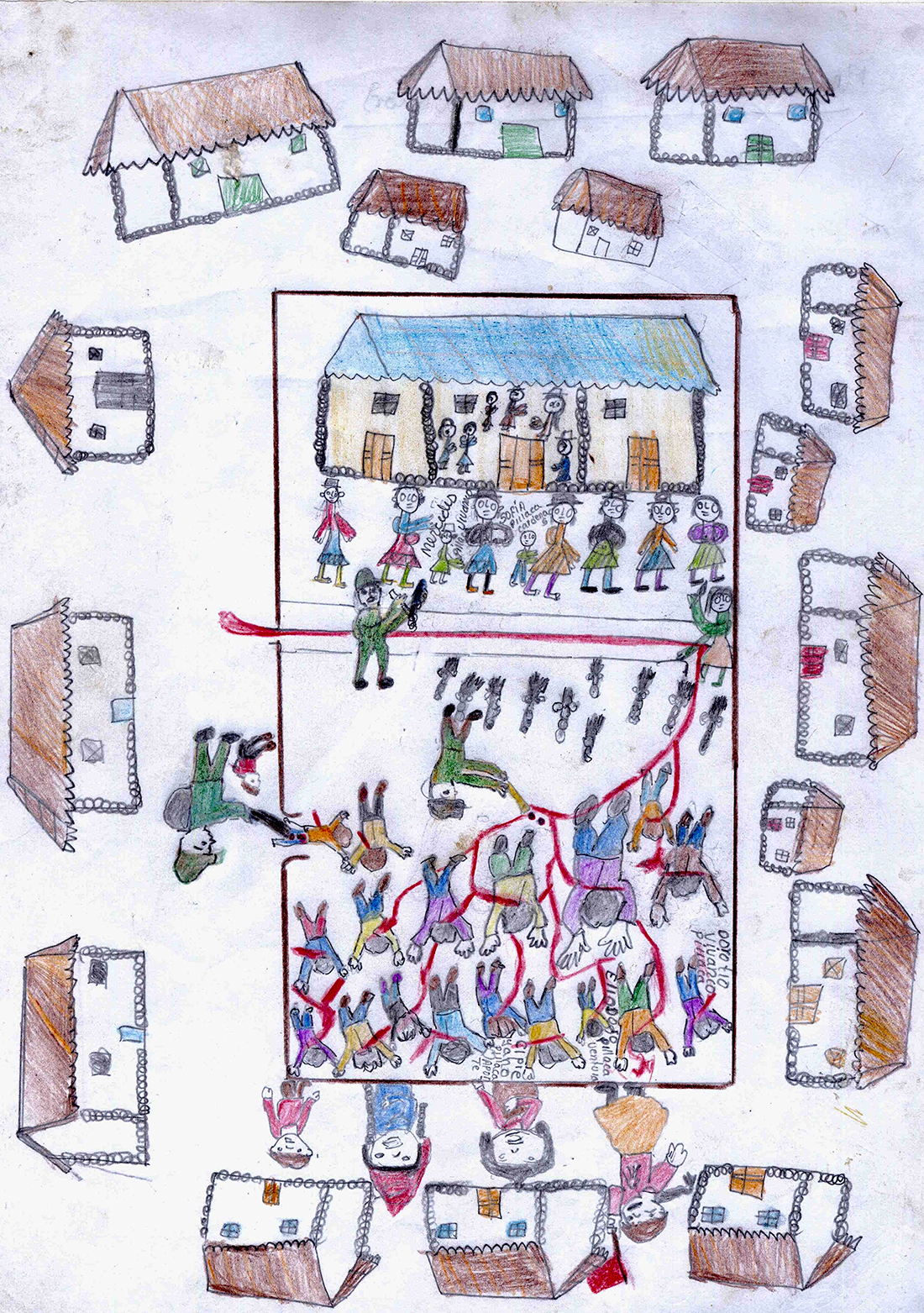

Mercedes ran up to her brother. ‘Do you want to die, too?’ The Senderistas assaulted her and beat her with a stick. ‘They hit my brother’s head until his eyes fell out’, she said. Because she was crying in despair, a male guerrilla told her: ‘Shut up! I’m going to kill your mother, too.’Footnote 77 He then attempted to cut Serafina’s throat with a knife, but in the end he cut off her braids. As Mercedes could remember clearly the bloody scene in the courtyard, during my fieldwork in 2008 I asked her to draw her childhood memory of that moment rather than narrate it (see Figure 2). In her drawing, the victims are divided by gender. The lower half shows the dead men face down and their blood flowing into the water channel that runs toward the square. The left-hand side shows the women, some in the classroom and others in the courtyard. The Maoists have already cut off their braids, which are on the ground. Mercedes also depicts herself in the drawing, writing her name and that of her family.

Figure 2. Drawing by Mercedes. Huamanquiquia, February 2008.

The Senderistas also struck terror into the women by attempting to set fire to them. Once the rebels had finished cutting off the women’s hair, they locked them inside the classroom. Many women heard a man order that they be set on fire; he even sent guerrillas to look for kerosene and petrol.Footnote 78 I asked Mariela about the order to set the women on fire. ‘There was an order to kill the women, but I don’t remember if there was an additional order to set them on fire; it is possible that someone, out of anger, could have said that to scare the women, but I don’t know’, she said.Footnote 79 Nevertheless, the women believed that the rebels wanted to set them on fire as they shouted to each other outside: ‘Where are the kerosene and matches? Let’s burn them alive.’Footnote 80 Terrified by this prospect, some women escaped by breaking a classroom window. The first to escape was Benita, who recalled, ‘I was pregnant, and I don’t know how I broke the window; maybe God helped me. I went first, and I fell among thornbushes, but I didn’t even feel it. Some women followed me while others remained inside.’Footnote 81

Most of the women managed to escape; a few – the elderly and mothers with young children – did not. Some guerrillas ran after the escapees; on reaching them they took them back to the courtyard, all the while hitting and kicking them. Alejandra was the last woman to try to escape. With her two little children in tow, she could not get out fast. She climbed up to the window and ran away, leaving one child with an older woman; the other was on her back. ‘When I was running, they shot at me. The gunshot sounded. I looked to the side of my foot; the bullet kicked up dust. Now they’re going reach me, and they’re going to kill me’, Alejandra thought. She then hid in a ruin, but two Senderistas came in immediately and dragged her out, kicking her in the belly. They got her back into the courtyard, hitting her all the time. The Senderistas threw her on top of the corpses and then dragged her off them again, saying, ‘Finish cooking the food!’ Almost at death’s door, Alejandra finished cooking, just as the rebels reunited in the courtyard after looting the houses. They collected the food and left the village, forbidding the now-shorn women from burying the corpses.Footnote 82

At dawn the following day, however, the women returned to the courtyard to bury their loved ones and recover their braids. They covered their heads with sweaters or llikllas (Andean blankets) to hide the remains of their braids. The scene before them was unspeakable, a place of horror. ‘I was speechless, seeing so many people dead; most had had their heads destroyed by axes, some were missing their foreheads, tongues and eyes’, Dolores, who lost her father-in-law, told me. ‘They were unrecognisable; even animals don’t die this way.’ Dolores had her one-year-old son on her back when the rebels cut off her braids. They had no compassion for her baby, who was crying.Footnote 83 The women collected their braids and took them away and burned them. By retrieving and burning their hair, they were mitigating some of the dangers of the loss of the integrity of their body–soul, explained earlier.

These women’s stories show how the Senderistas cut off their hair during the massacre of their male kin and the concomitant fear and terror. Most women lost their husbands; others lost not only their husbands but their sons, brothers and fathers as well. Some became widows very young, and others were left with many children to raise alone.

The pregnant women suffered particularly badly. These women underlined the rebels’ cruelty towards their pregnant bodies, sometimes kicking them, causing anxiety about damage to their unborn babies. As Benita recalled, ‘I was pregnant, I felt that the baby had died because of the insurgents kicking me, I couldn’t get rid of that thought.’Footnote 84 Two weeks after the massacre, she gave birth to a baby girl. Although Benita’s delivery was trouble free, others had severe complications and some lost their babies. As Alejandra testified, ‘Wañusqatam wachakurani’ (‘I gave birth to a dead child’).Footnote 85 She was four months pregnant when the rebels kicked her in the belly several times. In the following months, she had suffered terrible pain and vaginal bleeding. On 5 October 1992, Alejandra miscarried. It was a girl, as her death certificate indicated.Footnote 86

Benita spoke for all the women when she recalled how the rebels tortured them. ‘They kept hitting us with sticks and the buttstocks of their guns. We were tortured and incapacitated’, she said.Footnote 87 These forms of physical violence, in addition to the haircutting, left marks – and not only scars – on the women’s bodies. The rebels struck Benita with a stick, injuring her hand. She recovered, but her hand remains scarred and too weak for work.

In the end, most of the women understood the cutting off of their hair as another way of killing them. As Alejandra said, ‘Wañuchiwanankupaqñamiki’ (‘It was just like killing us’).Footnote 88 The women explained that cutting off their hair was a crime because it was not only physically damaging to their body integrity but also a violation of their human dignity, and of their gender identity, social and cultural values, practices and beliefs, such as the journey to the afterlife that I discussed earlier. I now turn to the traumatic and stigmatising effects of the massacre and haircut punishment.

Psychological and Social Impacts on the Women and their Children

The forcible haircutting, along with other violent and punitive actions, had psychological effects on the women, including traumatic symptoms, which, they say, were passed on to their children. The women describe trauma, introduced into the village by external agents, as an emotional state of distress and abnormality caused by tragedy. They often used the word ‘traumada’, Spanish for ‘traumatised’. For instance, Benita said that the insurgents had left women ‘traumadaqina’, a combination of Spanish and Quechua words meaning ‘as if traumatised’.Footnote 89 She used trauma as a discourse to allege individual and collective sufferings, thus claiming compensation and government and non-government support for the surviving victims, widows and orphans who had lost their relatives.

In particular, the pregnant widows were concerned about the damage done to their unborn children because of their own llakiy, painful memories that fill the body and torment the soul, or susto, loss of the essential life force due to fright. These women explained that their children died because they had passed on to them their llakiy, susto and other sufferings either in utero or via their breastmilk.Footnote 90 Kimberly Theidon uses the term ‘mancharisqa ñuñu’ in Quechua or ‘teta asustada’ in Spanish (‘frightened breast’), to capture the meaning of that explanation, which ‘conveys how strong negative emotions and memories can alter the body and how a mother can transmit these harmful emotions to her baby’.Footnote 91

The women also mentioned how their children had become traumatised since they had witnessed the horror – not only of killings, but also of the haircuttings. A case in point is Mercedes, mentioned above: she and her mother returned to the courtyard to look for her brother. After witnessing the bloodshed, Mercedes trembled with fear. Her flip-flops – by now covered in blood – got sticky when she tried to move and she eventually fainted, as she recalled: ‘I went to look for my brother and saw so much blood and death; I fainted. When I came to, the people around me were looking at me and giving me air. I was covered in blood, my sweater, and my skirt, all covered in blood. From that date until now, I have remained sonsa.’Footnote 92 ‘Sonsa’ means senseless, shell-shocked and foolish. Her drawing (Figure 2) depicts a traumatic scene, offering personal and community experiences as realistic, testimonial and visual evidence. Children like Mercedes who had seen the horror were disturbed by the memory or image of their loved ones.

The women and their children describe somatic complaints, vulnerability, isolation, detachment, reduced responsiveness, inability to feel safe or trusting, and other distressing symptoms. They struggled to recover from the pain, sometimes resorting to their traditional healing processes. In the Andean cosmovision, illness-like trauma symptoms result from an imbalance between the interchangeable energies of hucha and sami, explained above. To equalise these opposing energies, Quechua people consult local healers or ritual specialists who will bring balance and health to the individual and community by performing ritual ceremonies, removing blockages and restoring the flow of reciprocal exchanges between the various beings. For them, treating trauma does not just address a post-war psychological diagnosis but rather follows an Andean logic of restructuring a human way of living, feeling and healing alongside non-human living entities.

Turning to the social impacts, the women mentioned humiliation because the forcible haircutting left a mark on their bodies, a social stigma they carried for a while. Hair is a living extension of the body and represents women’s femininity, particularly in a patriarchal society like that of the Andes. The physical attack on the women’s hair represented the destruction of their bodies, a violent punishment for their betrayal in supporting the military. But it was not just a bodily attack; its meaning, as much as the massacre of the men, delivered a murderous message to the Shining Path’s enemies and to any villagers who rose against it.

The attack on the body included a sexual connotation as well. The Senderistas mistreated the women with sexualised verbal insults, such as ‘muru allqupa waynan’ (‘lover of the military’) and ‘china kuchi’ (‘female pig’).Footnote 93 The guerrillas labelled the military ‘muru allqu’ (‘mixed-breed spotted dog’) because of their multi-coloured camouflage uniforms. The term ‘china kuchi’ is a dreadful sexualised insult associated with prostitution in Andean society. The rebels were insinuating that the women had collaborated with the military not only by feeding them but also by providing them with sexual services. Even though this accusation was ridiculous, it lay behind the intended punishment based on women’s gender identity symbolised by their hair.

The insults and humiliation also extended to women’s gender relations with their fellow community members. The marks on their bodies provoked sexist and humorous comments among villagers. Although some had compassion for these women, others made fun of them by rudely calling them ‘cachimbas’ (Spanish) or ‘taka chukchas’ (Quechua) in reference to their shorn hair.Footnote 94 Meanwhile, the women who had lost their braids said that they had short hair, using the Quechua phrase ‘quru chukchas’.Footnote 95 Even though their hair grew back, it took roughly two years. During this time, the shorn women used headscarves or cloths to cover up their short hair and contend with the stigma.

The women were stigmatised even before the haircutting, when most of them were widowed following the killing of their husbands. With this change in their social status, they were no longer protected by their male kin. Being a widow is a social mark, and the one with the most vulnerability, in a male-dominated society like Huamanquiquia. The widows who lost their male kin, including fathers and brothers, felt orphaned as much as their children did. The remaining male family members left for Lima and other coastal cities to flee the ongoing violence. Adding to those who had been widowed in previous deadly events, the massacre meant that the village itself had become a ‘warmisapa llaqta’, meaning a ‘village of widows’ in Quechua, a significant stigma among rural society.

However, the widows overcame stigma and victimhood in the aftermath of the massacre. They redefined their roles to rebuild their lives and support their children, an immensely challenging task in the Andes. Wendy Coxshall, who has worked with widows in the community of Pallqa in northern Ayacucho, states that to understand their postwar experiences, ‘it is essential to situate them in the context of gendered and kin relations’. Like Huamanquiquia, Pallqa had the reputation of a ‘community of widows’. However, Coxshall challenges the feminist notion that such a community inherently fosters solidarity among women based on same-sex relationships and shared kin identities.Footnote 96 She argues that the widows of Pallqa often experience conflicts with one another and with various individuals and institutions, stemming from struggles over land, legitimacy and power in Peru’s racially stratified society.Footnote 97 Like those in Huamanquiquia, they navigate local tensions in a precarious patriarchal environment while engaging in a complex process of building memory and seeking justice, truth, and reparation.

The two leaders of the widows, Benita and Alejandra, became the protagonists of this story. After the massacre, they spearheaded the creation of a Comité de Mujeres (Women’s Committee) as a response to the suffering of widows. They established it to face up to, alleviate and solve the most urgent needs, such as food, medicine, housing and clothing for their children and families. In the early 2000s, as evidence was presented to the CVR, the widows struggled to testify about what had happened to their loved ones at the public hearings, when some villagers opposed them – arguing that they should not give evidence because of fear and because of the locals’ implication in the killing of Senderistas, among other things. Later, the Huamanquiquia widows founded the Asociación de Víctimas de Violencia Política en Huamanquiquia (Association of Victims of Political Violence in Huamanquiquia), and Benita and Alejandra became its president and vice-president, respectively. The organisation achieved a certain measure of justice, reparation and the recovery of persons disappeared during the conflict. During a long process of rebuilding their lives, the widows became political actors. They organised a community of victims to demand their rights. Finally, just as the violence was gendered and specifically targeted women, so these organisations fighting for justice and reparation are women-led.

Conclusion

In this article, I provide different perspectives on the 1992 massacre of 18 Indigenous men and the concurrent cutting of the hair of their wives and/or female kin by the Shining Path in Huamanquiquia. I frame these events as a local case study of gendered atrocity that was experienced differently by men and women. In my examination of the internal dynamics of this atrocity, I particularly counterpointed the first-hand accounts of the guerrilla militants and the Indigenous women who were widowed as a result of the massacre. My interviews with former guerrilla fighters revealed not only contradictions about their actions and responsibilities in killing men and cutting off women’s hair, but also the guerrilla commanders’ personal, political and ideological differences, displaying tensions between the middle-ranking and rank-and-file members of the Shining Path, as illustrated by Mariela’s actions and thoughts. A young female guerrilla, Mariela became the protagonist of these events and accounts by disobeying her guerrilla commander’s order to kill the women during the massacre and suggesting cutting off their hair instead.

The tensions also reflect a particular understanding of hair within broader Andean cosmologies. I explain that forcible haircutting constitutes a crime against the human body–soul integrity, damaging the journey to the afterlife in the Andean cosmovision. The Andean rank-and-file members of the Shining Path knew about these cosmological visions, even if they did not believe in them: they had practised or believed in them at an early age before becoming Maoists, and so were able to use haircutting to humiliate and punish the women for collaborating with the enemy. The Senderistas downplayed the haircutting because they, like their victims, understood it as a way of symbolically killing women in Andean society. For the victims, such action was a physical mutilation of their body parts, with the loss of their hair constituting a visible and considerably long-lasting mark on their bodies, a stigma. In addition, torture and other forms of cruel and degrading treatment accompanied this violence against the integrity of their bodies. A gendered atrocity, the haircutting resulted in shame, trauma and other psychological effects on the women, which extended to their children, as witnesses to the event. Compounding the fear and terror, the brutal action against the women took place during the murder of their husbands.

In conclusion, the haircutting incident against Indigenous women in the Andes is another form of symbolic violence that has been unaccounted for due to the Western-centric approach of the CVR. The Indigenous belief system is absent not only from the CVR but also from most academic reflections on the Peruvian internal armed conflict. Scholars on gender studies overlook this gendered atrocity, focusing more on sexual and gendered-based violence against girls and women. Haircutting violence is a further approach bringing Indigenous perspective and experiences to complete the picture of the gendered dimension of the Peruvian conflict.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to my colleagues Jelke Boesten, Rachel Nolan, Isabella Cosse, Zoila Mendoza, Sinclair Thomson, Charles F. Walker, the anonymous JLAS reviewers and the editors for their invaluable suggestions. The US-based Social Science Research Council (SSRC) funded my fieldwork for this research.