Introduction

The works of prominent contemporary Iranian composers Hossein Alīzādeh and Parvīz Meshkātīān demonstrate a novel approach to the text-music relationship, characterized by a new understanding of the interaction between music's internal syntax and structure and the external world. This innovative approach, which can be described as “musical realism,” strives to represent textual meanings through musical gestures, particularly within the tasnīf genre, a metrical, pre-composed song with a pre-determined way of accompaniment, which developed over the past century.Footnote 1 This approach, emerging primarily in contemporary compositions, is exemplified by the above two composers, who illustrate textual meaning through the intricate utilization of innovative treatments of modes, rhythm, melody, and texture relying on the potentials of the core of Persian musical tradition, the radīf – a collection of traditional Iranian melodic figures passed down orally through generations and serving as the foundational framework for improvisation and composition.Footnote 2 By examining select instances from these composers’ works, I highlight the growing emphasis on a realist music-text relationship and its interplay with both the inner structures of Persian classical music and the broader context of Iran's modern position in the world.

While this shift might be considered merely stylistic, I argue that it signifies a deeper paradigmatic transformation. My stylistic analysis of these two composers’ innovative approach contributes to a musico-philosophical narrative of Persian music, exploring the historical possibility of a shift in its objectives. In doing so, I draw on musicological approaches used to examine what is often termed musical modernity in Europe, a significant shift in the creation, performance, and perception of music, typically associated with the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Although this approach carries potential biases – ranging from the interpretation of historical materials to comparative analysis between two distinct musical cultures – my primary goal is to explore the possibility of a Persian musical modernity in contrast to prevailing Western narratives of musical modernity. This challenges the dominant discourse within Iranian music scholarship, which often defines modernity and innovation strictly according to Western musical principles. By reviewing various accounts of European musical modernity, I contend that this concept cannot be unconditionally applied to Persian music, as its relevance hinges on a recalibration, reevaluation, and modification that aligns with the unique attributes of Persian music and its historical trajectory.

This article is divided into two main sections. The first section presents the theoretical framework, introducing a common discourse of musical modernity within Persian musical scholarship and examining its reliance on the development of Western musical thought, particularly the romantic ideology of the 19th century. To unpack the assumptions underlying this discourse, I explore the major theories of musical modernity and notions of paradigm shifts in Western music history, generally structured around explaining the emergence of an autonomous understanding of music. Finally, I argue that transformations evident in contemporary Persian music, especially in the text-music relationship as demonstrated in the works of Alīzādeh and Meshkātīān, cannot be adequately explained using the framework of Western musical modernity and require a different theoretical approach that, instead of focusing on musical autonomy, welcomes the opposite: music's engagement with the external world. The second section is dedicated to the manifestation of this unique notion of musical modernity within the context of Persian music, examining three musical cases in which the relationship between music and text showcases a type of musical modernity rooted in music's engagement with the external world, rather than its abstraction from the so-called extra-musical. This section leads to and closes with a brief discussion of the political significance of realism in Persian music.

Throughout this article, I use concepts that require clear definitions. I use “modernity” to refer to paradigm shifts embodying deep transformations in values, goals, methods, etc. that emerge from internal structures of the phenomenon, but are often influenced by external factors. In contrast, I use the term “modernization” to denote efforts at mimicking or adapting European modernity within societies with distinct historical backgrounds, in this case Iran. For instance, the establishment of a new educational system and universities in Iran modeled after 18th and 19th-century European institutions (themselves the result of modernity emerging from within), without engaging with traditional Iranian educational structures, exemplifies modernization rather than modernity. Finally, I use the term “modern” to denote the outcome of either modernity or modernization: new practices, states, ideologies, technologies, and social structures, whether originating from internal evolutions or efforts to adopt or replicate Western advancements.

Accounts of Persian musical modernity

While concerns regarding modernity in Iranian music have been prevalent among many musicians and music writers, only a few have scrutinized the issue from a more foundational perspective. In an essay critiquing the recent state of Iranian art music (Persian classical music) over the past few decades, Hūmān Asadī focuses on not only identifying but also prescribing a path towards a modernity in Iranian music.Footnote 3 Drawing on the theories of contemporary Iranian political philosopher Javād Tabātabāee regarding modernity in Iran and its associated challenges, Asadī proposes that the realization of such a modernity is contingent upon the “condensation” (taghlīz) and activation of the potentials inherent in tradition.Footnote 4 For Iranian music, this tradition is embodied in the radīf repertoire. Asadī contends that over the last century, musicians have veered off course: rather than innovating within the radīf or even developing new modes and maghāms, they have treated the radīf as an unchanging repertoire, basing compositions exclusively on it. This approach has not only led to the stagnation of tradition, symbolized by the solidification of the radīf, but also to the production of repetitive and unoriginal works even within the so-called compositional repertoire. While Asadī places a strong emphasis on creativity, he does not specify the specific definition and ultimate purpose of creativity in Persian music. In other words, he does not introduce the fundamental objective to which the means (“loosening the rigidity of tradition”) will ultimately lead. Moreover, Asadī's emphasis on creativity assumes its necessity without examining the historical biases underlying this necessity, particularly those rooted in the 19th-century European understanding of art and music and their relationship with creativity.

The presumption of a so-called Romantic notion of music is more evident in the writings of Sāsān Fātemī, who offers a distinct perspective on the current state and future trajectory of Persian classical music, particularly in an article critiquing the approaches of composers from the 1960s to the present towards the relationship between text and music. Fātemī introduces two contrasting extremes: one advocating that music should primarily serve the text, and another positing that the text should conform to the internal structure of the music. He advocates for a “point of balance” as the “ideal” scenario, where music and text “mutually complement and serve each other.”Footnote 5 Fātemī acknowledges the evolutionary nature of the text-music relationship over time, discussing two approaches to the Persian tasnīf – the more recent one, according to which music must serve poetry, and the older one holding the opposite view – as two theories offered in two different time periods. However, he does not attempt to contextualize these approaches within broader historical shifts or objectives in the evolution of Persian music. It appears that these approaches possess aesthetic merits that transcend historical context and were not themselves shaped in an interaction with historical forces.Footnote 6

Fātemī's discussion largely responds to The Link Between Poetry and Vocal Music (1998), an influential book by Iranian composer Hossein Dehlavī on the text-music relationship in Persian music, which aimed to provide a systematic theory for setting Persian poetry to music in a “natural” way aligning with the inherent musicality of the Persian language.Footnote 7 Melodies to which the text flows smoothly and intelligibly are the outcomes of Dehlavī's approach. Part of this involves examining the rhythmic organization of poems’ syllables, accentuation for clarity, and considerations of phrasing and formal structure. Fātemī challenges the notion that music should be molded to suit the readability of poetry and questions Dehlavī's view that music should follow the natural declamation of the text. Fātemī critiques what he terms “figuralism” in Western music history, arguing that an excessive emphasis on word representation in music has led to chaos and a loss of meaning in the overall historical trajectory of Western music.Footnote 8

While one can engage in a debate over Fātemī's generalization of the development of the text-music relationship in Western music history, the key point here is the ahistorical, non-contextual nature of the assertion, which overlooks the nuanced evolution of this relationship and seeks to label specific approaches as right or wrong.Footnote 9 Fātemī contends that the post-revolutionary (post-1979) approach to the text-music relationship, wherein music consistently serves the text, has led to monotonous and repetitive melodies. Highlighting the autonomous and enigmatic nature of musical sounds, and raising skepticism about the feasibility of any form of musical representation (music serving the meaning of the text), Fātemī argues that the most effective relationship allows both arts to function within their independent domains without interfering with one another.Footnote 10 Drawing on Nicolas Ruwet, Fātemī suggests that the ideal state arises when the distinctive attributes of these two arts (music and poetry) converge to create a new entity.Footnote 11

While Asadī and Fātemī's accounts serve as two examples within the discourse of musical modernity in the Persian tradition, they are central to broader conversations about creativity and innovation in Iranian music. These ideas and perspectives largely emphasize a modern Western aesthetic ideal, often perceived as transcending historical and cultural contingence. This aesthetic, rooted in an autonomous understanding of music, is historically conditioned and influenced by the romanticism of late 18th and early 19th-century European music history. To examine the historicity of some of the ideologies of Western music often perceived as ahistorical, I explore several recent, influential accounts of musical modernity in European music history. This exploration enables us to not only identify what I call “comparison slides” – instances in which examples, patterns, or developments from another culture (usually Western) are copied without considering the complexity of the historical context – but also consider alternative narratives of modernity in order to understand the unique historical trajectories of Iranian music.

Western European musical modernity

Western music scholarship has approached the concept of musical modernity as a comprehensive framework that goes beyond the stylistic categorization of music. This relatively recent concept aims to transcend conventional style-based periods and instead identify and elucidate pivotal, epoch-making transformations in Western musical thought and practice. Accounts of Western musical modernity often propose that the entire realm of Western music's creation and experience underwent a paradigmatic shift primarily attributable to the significant transformations that took place around the year 1800.Footnote 12 This narrative of musical modernity highlights the historical ruptures that unfolded during the late 18th and wearly 19th centuries – the Enlightenment, French Revolution, and their subsequent social, political, and intellectual developments – presuming that the current world continues to be constrained by fundamentally similar conditions. A common theme of this narrative is the emergence of an autonomous understanding of music, which is believed to construct a conceptual severance between the musical and the so-called extra-musical, corresponding with the rise of extensive philosophical, political, social, and aesthetic concepts that contributed to the establishment of a modern notion of the human subject as an autonomous being.Footnote 13

Karol Berger's account of musical modernity highlights the shift from a cyclical to linear conception of time in the decades surrounding the French Revolution, alongside the construction of a distanced notion of the past as a result of massive transformations in Europe's lifestyles and ways of thinking. This shift in the conception of time aligned with the new approach to music-making that took the temporal order in which events occur seriously. Exemplified in the Viennese sonata genres, Berger argues, the temporal organization of sonata events, i.e., exposition, development, recapitulation, and their inner temporal structures, became essential to the meaning of the work. This new notion of musical time conditioned our expectations and understanding of any music we encounter, attributing “time's arrow,” a linear progressive notion of musical movement, to the essential quality of music.Footnote 14

Lydia Goehr identified musical modernity with the development of a regulatory work-based notion of music. Historicizing music ontology, Goehr states that music was defined in terms of extra-musical ideals prior to 1800, and understood in terms of its own inner rules and structure thereafter.Footnote 15 This shift created a chasm in the regulative forces of music: whereas the pre-modern notion of music underlined performing extra-musical functions either as an “homage to God” or obedience to “the wishes of employers,” modern music was considered autonomous, serious, and centered around a regulative, objectified notion of musical compositions embodied in musical works. Music as a process or performative activity was replaced by music as a product free of an Aristotelian notion of final causality.Footnote 16 As an object, music stood beyond everyday use or function, a paradoxical situation socially responded to by the emergence of the concert hall, a space detached from the everyday life and world. Similar to plastic artworks’ situation in museums and art galleries, concert halls “framed” musical works and “stripped” them of their “local, historical, and worldly origins, even [their] human origins.”Footnote 17 Since there was no tangible thing in music that could be placed in musical museums, it “had to find a plastic or equivalent commodity, [. . .] a permanently existing product” that could be turned into an aesthetic object: an object, called the work, that “could be divorced from everyday contexts [. . .] and be contemplated purely aesthetically.”Footnote 18

Unlike Berger and Goehr, who emphasize a shift in the concept of music itself, Mark Evan Bonds highlights a paradigm shift in music listening, focusing on the experience of music.Footnote 19 According to him, the rise of a new philosophy of perception also revolutionized the act of listening, which gave rise to a new approach to the experience of instrumental music in general and symphonic works in particular –exemplified in, but not limited to, the perception of Beethoven's music.Footnote 20 This shift was equally reliant on the new understanding of all arts around 1800, influenced by emerging aesthetic thought. Kant's emphasis on human subjectivity in shaping both general and aesthetic experience marked a significant move from a passive to active role for the beholder in art and the listener in music. Within this intellectual context, Bonds underlines the role of listeners and “the premises of perception rather than on the work themselves” in the “transformation of attitudes toward instrumental music.”Footnote 21 It is listeners who must understand the work in order to experientially unveil its truth and therefore – as romantics such as E.T.A. Hoffmann insisted – if a listener cannot perceive the sublime in music, it is the former's “fault alone.”Footnote 22

Questioning the “comparison slides”

Tales of Western musical modernity are numerous, and the above accounts are just a few examples of typical narratives. Despite vigorous debate over the aesthetic, political, social, and philosophical significance and extent of paradigm shifts in Western music history, as mentioned earlier, there is consensus on the emergence of a novel conception of music as an autonomous art around 1800. This shift, reflected in music's independence from its extra-musical (religious, social, and political) functions, led to – in Adorno's words – music's “disavowal of magical practices … [and] participation in rationality.”Footnote 23 But if European music modernity is perceived as a move from a representational (non-autonomous) model towards musical self-determination – embraced by the increasing interest in pure, functionless instrumental music – the study of other musical modernities requires an examination of their unique historical trajectories, contexts, and dynamics. In this respect, Persian musical modernity seems to be taking a different path. For many centuries, the main space for the creation and performance of Persian classical music was the secular court of kings and nobles, where instrumental music was accepted as a complete form of musical expression not necessarily reliant on dance or other social functions. Aesthetic approaches to music shaped and influenced by Iranian mysticism meant that elite listeners of Persian classical music (and some regional music) never questioned the necessity and meaning of pure instrumental music.Footnote 24 The modern move towards representation in music and its engagement with life, exemplified in the tasnīfs discussed in this article, contrasts with the more established abstract approach to music in Iran and the common practice of solo instrumental performances of the radīf tradition.Footnote 25 The fact that the main repertoire of Persian music, which fosters creativity, includes both sāzī (instrumental) and āvāzī (vocal) versions – with an even greater emphasis on radīfe sāzī (instrumental radīf) – demonstrates the comfortable place of untexted music in Persian classical music.Footnote 26

To address this peculiarity within Persian music history and explore a more inclusive possibility of musical modernity, Gary Tomlinson's suggestion is invaluable. Instead of seeking a specific shift in music history, Tomlinson, drawing on Slavoj Žižek, views musical modernity as “a moment when music restructured its endeavor to provoke the answer of the other.”Footnote 27 This restructuring signifies “the mutation of one symbolic order into another.”Footnote 28 This framework avoids reifying historical processes as ahistorical truths, allowing us to identify several restructuring periods in Western music, including the shift toward drama in music around 1600, the move toward musical autonomy around 1800, the innovations of Schoenberg around 1900, and the introduction of noise and music's emancipation from tone as the most recent potential restructuring.

Given Persian music's conventional “structure of endeavor,” the autonomous restructuring of music – or the restructuring of musical symbolic order around music's inner rules within a tradition – seemed unnecessary, as pure instrumental music was not problematic within Persian music and the conundrum of musical meaning was responded to half aesthetically and half mystically through the long history of music's connection to erfān (mysticism), leading to an ethereal and abstract understanding of music as the most unworldly art. Efforts beginning with Alī-Naghī Vazīrī and Abu'l-Hasan Sabā, especially in programmatic instrumental works (musical pieces such as “dokhtarake jhūlideh”, “kārevān”, etc.), and continued by others – including Alīzādeh and Meshkātiān in their vocal compositions – aimed to restructure music to be more worldly, less mystical and abstract. This restructuring seemed necessary in the context of Persian music history and, as discussed below, its entanglement with contemporary politics.

Music representation has frequently been undervalued, seen as reliant on “external” and ostensibly “non-musical” variables for its referential meaning. This ideology, based on 19th-century romantic thought and its underlying assumptions and values, has not only maintained the myth of musical autonomy but also led to misconceptions about the true nature of musical representation. Lawrence Kramer offers a more nuanced, “deconstructed” notion of music representation, extending the notion beyond a simple sign-referent relationship. According to Kramer, music representation exists within a metaphorical tropological domain, creating a “hermeneutic window” that allows for the possibility of musical meaning. Drawing on Derrida, Kramer emphasizes that “the trope ‘opens the wandering of the semantic’ by placing the representation in the thick of the communicative economy, affiliating it with a wide variety of discourses and their social, historical, ideological, psychical, and rhetorical forces.”Footnote 29 This dynamic account of music representation surpasses a static, one-way conveyance of meaning through an arbitrary sign. Instead, representation becomes a space of interactive exchange, which “condenses the discursive field into the music” while simultaneously reinterpreting the discourse through the music: “The music and the discourse do not enter into a text-context relationship, but rather into a relationship of dialogical exchange.”Footnote 30

Emphasizing this relationship of dialogical exchange, I examine musical pieces that showcase a restructuring of musical symbolic order towards representation, or the active engagement of musical sound with the world. In the conventional approach to Persian classical music, reflected in the vocal versions of the radīf or other old vocal pieces, the relationship between music and text is not realistic or representational. As briefly mentioned at the outset of this article, the creation of Persian classical music relies on the radīf, a collection of melodies known as gūsheh organized based on their modal properties (or their maghāms) in groups called dastgāh. In this music tradition, the melodies or melodic units created for the text usually receive their modal properties from the pre-given structure of the modes or maghāms and the rhythmic properties from the text. Therefore, the main concern for improvisers or composers of vocal music in this musical tradition is usually how the music should fit the rhythm; of less concern is the meaning of the text, which in almost all cases (except in some recent experimentations) is chosen from the vast repertoire of Persian classical poetry. This poetic tradition is based on specific rhythmic modes or formulas that follow a quantitative system known as arūz (عروض ). These patterns of long and short syllables in Persian poetry not only shape the way a poem is recited but also condition the phrasing and rhythmic structure of the music created for the verses. As reflected in example one, the opening verse of a tasnīf composed by Meshkātīān and sung by Mohammad-Rezā Shajarīān in 1986 (“Jāne Jahān” in the album Navā: Morakabkhāni) shows a text-music relationship strongly shaped by two things: the metrical structure of the poem (_UU_ _UU_ _U_), which conditions the way it would be “naturally” recited, and the modal language of the dastgāh navā's opening maghām, known as darāmad. Here, while the other melodic behaviors of the line follows the modal framework of the dastgāh navā, the rhythm of the melodic line responds naturally to the meter of the poem:

In this conventional approach, the text's rhythm is the main aspect that needs to be reflected in its musical setting, leading to a natural declamation of the text. This could be sacrificed in some cases, however, if a stronger expression of the mode necessitates. A notable example from a classic composition is the heroic and patriotic tasnīf composed by poet and composer Abolghāsem Āref Ghazvīnī on lyrics he wrote himself. Titled “From the Blood of Homeland's Youth,” the tasnīf begins with a melodic phrase that is precisely repeated in the second half of the verse (Example 1):

Musical Example 1. Āref Ghazvīni, “From the Blood of Homeland's Youth.”Footnote 31

The setting can be interpreted to show some instances of text-painting, a musical technique wherein the composition mirrors the text's literal meaning. While the repetition of the word lāleh (tulips) is painterly and responds to the meaning of the text (many young people have lost their lives), the repetition of the word vatan (homeland) has no clear function here. Vatan is one, unless we interpret it as a perceived danger of vatan becoming fragmented – a far-fetched interpretation that does not fit the entire work. Another instance of text-painting is the high note on the word sarv, which illustrates the height of the tree and, by extension, the height of the youth. However, Āref's strophic form for this tasnīf – where all stanzas of the text are set to the same melody – emphasizes the text's overall emotional content rather than the representation of individual word meanings. In this more conventional approach, which prioritizes the “perfect” and unwavering statement of the radīf's modal language, some phrasing divisions occur in the middle of words, and the repetition of several syllables serves primarily to reaffirm the modal structure of the āvāz dashtī. To sum up, the text-music relationship here mostly reflects a general connection between the lamentation in the mode dashtī and the text's mourning praise for those killed in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution.Footnote 32

Despite this conventional text-music relationship in Persian classical music, as previously discussed, recent tasnīf compositions demonstrate innovative approaches. These works, though partially reliant on a Western notion of text-painting or musical topics, are primarily built on the potentials within the Persian musical language.Footnote 33 They use the radīf's modality, with novel sensitivity to rhythm, melodic features, and texture to create a more representational music that realistically responds to the text's meaning. This is discussed further below.

Three representational tasnīfs

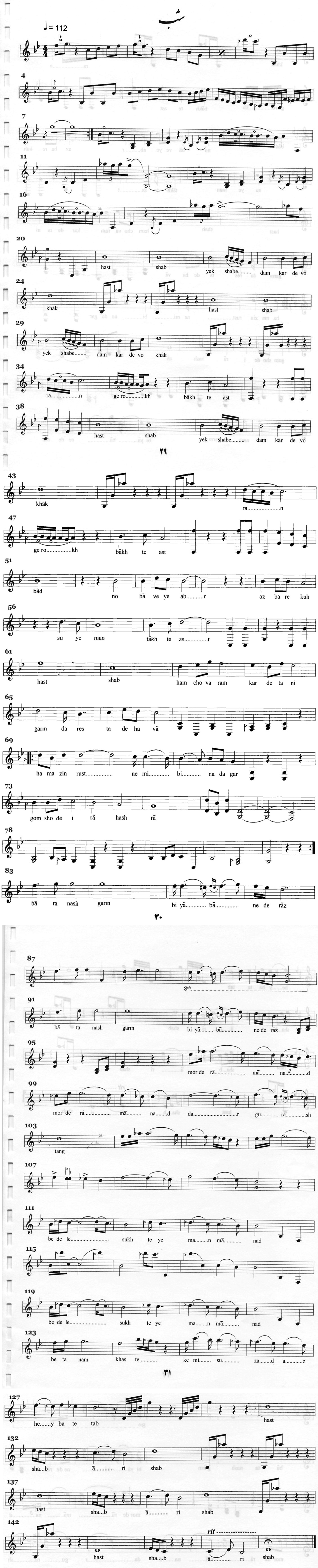

ONE: A realist link between the radīf and the extra-musical ideas presented in the text can be heard in Parvīz Meshkātiān's “Hast Shab” (Night Is), a tasnīf with strongly political text and innovative musical qualities that was performed and recorded in Paris in 1995, less than two decades after the 1979 Islamic Revolution of Iran. The text, written in pre-revolutionary Iran, is a poem by Nīmā Yūshīj (1897–1960), a prominent modern Iranian poet credited with inventing a new style of Persian poetry, She'r-e Nou.Footnote 34

The words can be interpreted as an expression of either inner suffering projected onto the outer nature or as a depiction of what Yūshīj perceived as the dark political atmosphere of 1950s Iran. The music, created decades later, in the post-revolutionary context of the 1980s, presents two distinct streams of musical ideas, which, while complementing each other and working together to depict this inner/outer darkness, characterize two distinct approaches to the radīf: a novel approach to instrumental accompaniment that integrates the radīf's melodic language with new techniques to depict darkness, and a more conventional, less adventurous treatment of the vocal line, which still attempts to activate a representational mood.

Meshkātiān's melody for the singing voice, while remaining mostly faithful to the rhythmic and melodic idiom of the radīf, draws on modal potentials to not only sound novel but also depict the meaning of the text. The vocal line opens with an emphasis on the third degree of the shūr scale by two whole notes of Bb in the lower register: “Night is” (Musical example 2, mm. 21–24). These two long notes are followed by a half-note Bb on the word yek (a/one) and then a quick descending figure that deepens the picture of the silent, ominous night – a stark contrast to the romantic notion of night. The 3rd degree is then repeated four more times with increasingly quicker notes, ascending to the 5th, the most prominent degree of the mode dashtī. This first half of the opening statement, from a rhythmic and motivic perspective, follows common gestures in the radīf, with strong references to the dastgāh shur and its two sub-modes of dashtī and bayāte-kord. However, the melody's reliance on the radīf's modality depicts both the dismal, bleak night and the vastness of the desert. This is achieved by moving to the 5th to convey the dreary feeling of being in this night/desert through the hesitations in the melodic motion upward – a hesitation grounded in the melodic behaviors of the related gūshehs from the radīf.

Musical Example 2. Parvīz Meshkātiān, “Hast Shab” (Night Is), transcribed by Alireza Javaheri.Footnote 36

A variation of this opening phrase is used for the second verse, where the descending stepwise motion from the 5th to the 3rd on the word sūye man (toward me) depicts the wind's approach: “Wind, the descendent of clouds gallops / down the mountainside toward me” (mm. 51–59). The second time the poetic motif “Night is” comes back, it is set to the same long notes but this time on the 7th and 4th, preparing for a descending sequence depicting the phrase “like a bloated body” twisting around 7th, 6th, 5th, and finally hanging on the 4th, which functions like a suspension in the mode dashtī to express “warm in the standing air” (mm. 61–66).

A more expressive and intense variation of the same sequence ascending as high as the flat 9th, subtly resembling the original motif, responds to the second phrase of the next line, where the poet describes the desert: “The warm body of the desert extends / like a corpse tight in its grave.” This leads to the highest pitch in the vocal line (m. 125), reaching the 11th degree of the scale on the word “burning,” with a descending four-note figure struggling and finally descending to the 5th (mm. 125–8), where we hear the mode dashtī in its more stable stance for the first time, signifying a self-awareness about the presence of outer and inner night: “like the charred heart in my tired body burning feverishly. There is night. Yes. Night.”

The closing section, setting the last line of the poem (“There is night. Yes. Night.”), introduces a lamenting phrase in dashtī beginning on the 5th, the shāhed note – a recurring recitation tone usually other than the tonic and an equally expressive and highly important characteristic feature of a mode – that, although appears many times in the vocal line, never solidifies as a stable moment (mm. 131–46). The line set to one melodic unit and repeated three times is now a complete rendition of the mode dashtī by reciting the 5th (shāhed) with its characteristic pauses on the 4th and 3rd. The singing voice takes refuge in the secure realm of dashtī, so to speak, which seems to become possible by achieving the more stable version of the 5th only after feeling the intensity of the high cry of “burning from the fever” on the 11th. The contrast between the high and lower octave repetitions of the same ending motif, which brings together the inner and outer darkness, is bracketed by the expressive santūr gesture, which acts like an arpeggio emphasizing the 9th (mm. 135–6 and 141–2). This gesture, associated with the ominous night and silence, is constructed on a foundational two-note figure explored in more detail below. Its importance lies in the variations of this figure, evident in both vocal and instrumental parts, serving as a cohesive element binding the entire piece together.

The santūr accompaniment offers a novel approach to instrumental music throughout the work. Departing from the typical unison – heterophonic in some cases – accompaniment prevalent in this musical tradition, the santūr takes on a dynamic role by engaging in a dialogue with and providing commentary on the vocal line. Achieving this by presenting melodies and fragmentary ideas that juxtapose standard phrases of the radīf with innovative motives or figures, the santūr's interaction serves to reinterpret the text within a new political context. The santūr prelude introduces a figure that develops multiple times in the opening measures and recurs alongside variations throughout the entire song – a two-note gesture comprising a sixteenth followed by a dotted eighth (mm. 1–4). While this figure, a common element in the context of melodic phrases in the radīf due to its basic short-long construction, typically serves auxiliary roles, it is notably emphasized here, drawing attention to its expressive potential rather than its usual supporting function. Throughout the prelude, this figure is interwoven with attempts to form more conventional melodic phrases (m. 10). However, these efforts intentionally remain incomplete, voicing the tension between modernity and tradition and rendering the prelude more atmospheric than melodic.

Another instance of the santūr challenging conventional expectations in Persian music is when it initiates a phrase resembling the beginning of an elaborate response to the vocal line but is abruptly interrupted by the vocal line itself singing: “Night is!” This interruption occurs twice after the opening phrases. This innovative accompaniment style not only introduces a new sonic environment but also adopts a dramatic, representational approach to the text-music relationship. Combined with a melody deeply rooted in the grammar of the radīf, yet approached with expressive creativity, this accompaniment style uniquely blends the old and new, seeking to connect with the external world. Specifically, the style engages with the somber atmosphere and political oppression of post-revolutionary Iran.

A noteworthy aspect of the innovative sonic environment crafted by Meshkātiān in this tasnīf is the strategic use of silence, a feature not commonly found in traditional tasnīfs. Meshkātiān harnesses the inherent potential of pauses present in the traditional performance of āvāzī, the non-metrical type of music-making in this tradition. These pauses, characterized by their reference to non-metrical structures and free rhythmic articulations, often entail extended breaks in exchanges between the singer and accompanist, employed adeptly to evoke the essence of night.Footnote 37

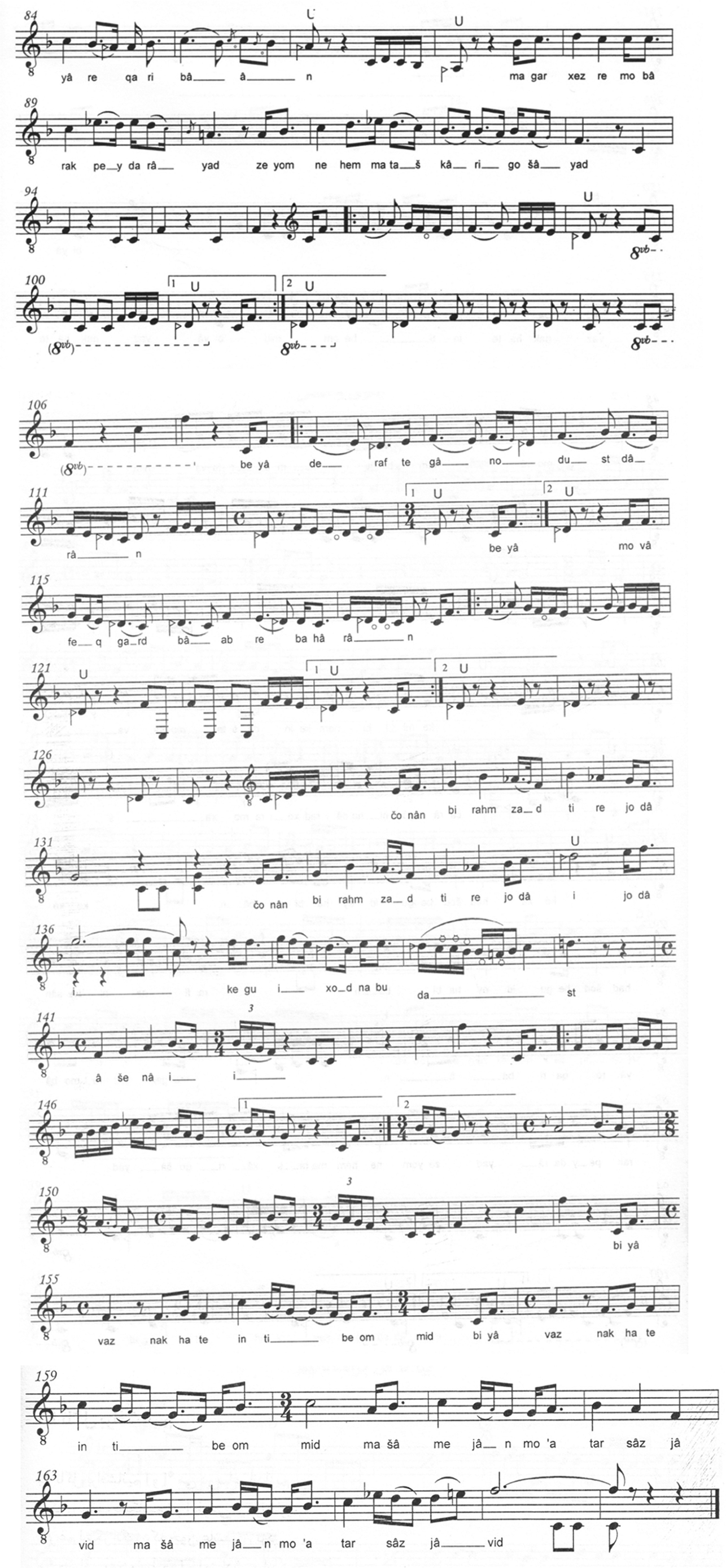

TWO: In Hossein Alīzādeh's tasnīf setting of Hāfez's renowned masnavī, “āhuye vahshī” (Wild Gazelle), almost halfway through the piece, the initially soft and almost carefree coy of the mode rāst-panjgāh suddenly shifts into an intense and lengthy section in the lamenting mood of the mode shūshtarī (Example 3: mm. 96–140).Footnote 38 Before this shift, there is a hopeful expression of a wish for the entrance of Khezr – an obscure mythical folklore figure, a prophet believed to bring fertility – with his “feet graced with luck” (Musical example 3: mm. 87–93).Footnote 40 However, the mood changes as the poet recalls the departed, urging listeners to “harmonize with the Spring-clouds” to shed tears, remembering departed loved ones. This emotional transition is expressed through a brief instrumental section, which restates the joyful opening motif yet modulated to the nostalgic mode shūshtarī, turning the melody's emotional content inside out and evoking a sense of longing and melancholy (mm. 96–107).

Musical Example 3. “Āhuye Vahshī,” Hossein Alīzādeh, mm. 84–167.Footnote 39

Alīzādeh's illustrative setting of selected verses of Hāfez's poem can be especially heard in the return to the mode rāst-panjgāh after the long lamentation, reaching the highest note of the song in shūshtarī. Here, after the moment highlights the verse's complex emotions, Hāfez combines the sorrowful illustration of separation. Using the simile of a “blade/sword,” three iterations of the word “separation” ascend in pitch by leaps, each time evoking the fierce, slicing motion of a sword and culminating in the piece's most intense and vehement moment. Then, suddenly, a swift shift occurs into the sarcastic and bitterly humorous complaints about the unfair treatment of friendship (mm. 132–142):

The first mesrā (hemistich) achieves the peak of shūshtarī's expressive force, completed by the opening phrase of the second. However, the mood rapidly shifts back to the playful melodic formula of rāst-panjgāh as the last syllable of “nabūdast” (has not been) is reached. This transition involves a quick tahrīr on a stepwise descending fourth, leading to the khātemeh (final) on the last syllable of “āshenāī” (acquaintance).Footnote 41 Notably, the word āshenāī was previously heard at the end of the tasnīf's opening verse, where it rhymed with the question “kojāī?” (where are you?); in this instance, it rhymes with “jodāī” (separation). The same melodic formula on the same word serves as a connection between the two verses: while the opening verse confirms the long history of acquaintance, the second appearance of āshenāī with the same musical figure emphasizes the intensity of the separation that has almost eradicated the memory of āshenāī with the “wild gazelle,” the beautiful beloved that we now understand has run away. It is at this point, and only in retrospect, that we realize the main issue likely lies not with the wild gazelle's decision to flee, but rather with the external world that has lost its charm and greenery. The world is no longer pleasant. The implication becomes clear that one must cry, akin to clouds that are probably absent, unable to compensate for the lack of rain – the absence of which has caused both the separation and a barren desert.

The final verse is skillfully set to a triumphant musical closure, which subtly hints at a glimmer of hope. However, this hope is peculiar in nature, as it beckons us to infuse our soul with the “aroma of hope” eternally! The word “eternally” resonates with the high final note, but this resonance, like the fragrance of hope, is transient. The paradox lies in the fact that it is precisely through the fleeting essence of fragrance and sonic memory that one must maintain hope (mm. 154–167).Footnote 42

It is through this “external” resonance of hope that the tasnīf's opening verse can be heard from a new perspective. The opening verse introduces a playful demeanor, with notes leaping unpredictably, a vibrant and unconventional melodic pattern that deviates from the usual gestures in Persian music (Musical example 4, mm. 14–20). This jagged, meandering melodic progression—shifting between duple/quadruple and triple metres to accommodate both the cadential formula of the mode rāst-panjgāh and the rhythmic necessities of the text—alludes to the quest for the āhuye vahshī, while adeptly employing the coy playfulness of rāst-panjgāh, particularly the darāmad gūsheh. The rhythmic activity further contributes to depicting a lover engaged in a hide-and-seek pursuit of their beloved. The fact that this lighthearted game gradually takes on a serious tone, as illustrated above in the discussion of the song's modulation to the mode shūshtarī, leads us to reinterpret the opening verse, wondering maybe the āhuye vahshī is the poetic voice herself – a wanderer akin to the wild gazelle, in search of individuals she has lost. From this perspective, the abrupt surge of nostalgic recollection of departed companions is profoundly intertwined with the unearthing of a novel musical territory, one fraught with pain, concealed emotions, and the subconscious. Alīzādeh's selection of Hāfez's verses aligns with the musical narrative – namely, the modality's inherent capacities, the transitions between diverse modes – alongside melodic motion and rhythm, amplifying the existing storytelling aspect within rāst-panjgāh. In this context, it is the modality's inherent capacities, the transitions between diverse modes, that chiefly underpin the textual significance and its conveyed emotions. Crafting moments of such strong impact, where a profound interplay between musical and textual shifts resonates in alignment with the syntax of the radīf, represents an unconventional approach within the context of the text-music relationship in Persian classical music.

Musical Example 4. “Āhuye Vahshī,” Hossein Alīzādeh, mm. 10–23.

THREE: While both tasnīfs discussed above work through the potentials of the radīf and existing modes, treating them as means to new representational goals, Alīzādeh's tasnīf “falak,” on the Rāz-e Nō (Novel Mystery, 1998) album, goes beyond these in two ways: it introduces a new mode and explores the possibility of new textures through an original approach to polyphony in Persian music. The album, composed for four vocal lines, two percussions, and a melodic instrument (tār in one section and Kurdish tanbūr with intervallic modification in the other), can be examined from various compositional perspectives. In this article, however, I highlight the realistic approach to text-setting in “falak” shaped through both polyphonic gestures and novel modal properties.

Rāz-e Nō's sound was perceived by contemporary audiences, including myself, as simultaneously fresh and ancient, mostly because of its adherence to the foundations of the radīf while exploring new possibilities.Footnote 43 For example, to create his new mode, Alīzādeh combined two modes that already existed in Persian music: dād, a maghām within the dastgāh māhūr, which emphasizes (tonicizes) the second degree of the māhūr scale (similar to major); and bīdād, a maghām within the dastgāh homāyūn, which emphasizes the “same” note, the fifth degree in the context of homāyūn. The result is a new musical maghām, which Alīzādeh calls dād-o-bīdād.Footnote 44 The combination of emotional characters of dād with bīdād leads to unprecedented emotional content in this music tradition.

While Alīzādeh's combination of the two modes appears novel, his method is based on the radīf's own modal logic. There are two major ways in which non-scale tones are introduced in Persian maghāms. The first method, exemplified by modes such as afshārī and dashtī, is based on quite rapid coloristic shifts between a note's natural and quarter-tone lowered versions. The second method occurs in the context of transitions to other maghāms – exemplified in the shift from the main mode of māhūr to some of its sub-modes such as delkash or arāgh – which usually takes longer and requires much preparation. Alīzādeh's dād-o-bīdād appears to borrow from both of these methods. Thanks to its transient modulation-like gesture, it has the potential to quickly shift into another mode by switching from the whole-step second degree (similar to note mi in Dorian mode) to the second half-step (similar to fa in Phrygian mode), while having the potential to remain in the target mode. As a result, dād-o-bīdād is both flexible in its alternations between dād and bīdād and provides enough space for the stable expression of each mode and their contrasting moods and emotional states.Footnote 45

The second aspect of Alīzādeh's novelty, namely the polyphonic setting of the vocal lines, stands out more because its departure from the traditional approach to texture in Persian music appears to be more revolutionary. Four singers – and at times, five singers, most likely including Alīzādeh himself – sing contrapuntal lines that, while based on vocal techniques of Persian classical music, display the influence of Western polyphony.

Employing the two above-mentioned musical elements, Alīzādeh's music actively engages with the text, a poem written by the 18th-century poet Mīrzā Nasīr Esfahānī. The musical setting of the opening two verses seems to manifest Alīzādeh's “novel mystery,” sung in monophony and restated in polyphony, while both times introducing a taste of bīdād at the end of the final phrase through what I term “bīdād cadences.” The imitative polyphony through which all the words are repeated multiple times depicts the poem's meaning, which describes a tyrannical condition dominating the world:Footnote 46

While the monophonic setting shows how the entire chamber choir (likely representing society) is unified in its perception of tyranny, the polyphonic setting supports the same idea by depicting the magnitude and variety of pain as well as “unorthodox ways” of approaching life. In the second verse, where the words emphasize a situation in which all values have been turned upside down, the phrase “the Nightingale is chorusing with the Crow” is stressed by the musical disparity between the representation of these two birds: the contrast between the status of the nightingale and the crow is sonically depicted through an ascending leap on the word hazār and a twisted descending fast melisma (tahrīr) on the word zāgh, an intriguing attempt to mimic the sounds and statuses of these two birds using the established vocal techniques of Persian music.

While the contrast is emphasized on the words denoting each bird, the word “chorusing with” receives a limited, almost static, melodic motion showing how both words have found the same “register” and status among listeners, likely singing the same songs. The bīdād cadence in this verse is reserved for the moment when all singers lament the cruel destiny of the rose who has “suffered neglect” and, under the tyrannical condition, is nothing but “a thorn in the Garden.”

The effect of mixing monophony and polyphony is also used for the third verse. However, instead of a coloristic bīdād cadence, a complete shift to the mode bīdād happens. The lamenting emotion of the word “a thorn in the Garden,” heard at the end of the second verse, becomes a starting point, but only to reveal a new aspect of bīdād: anger at the state of injustice. The bīdād's lamentation and anger, which unfolds in the third verse, is indeed the emotional response to the tragedy described in the first two verses. The sorrowful scene is introduced briefly on the tār and then prepared in the bass by part of the choir singing in unison. While the same parts sing the same verse again (but this time not in unison), the soprano intensifies the feeling of anger and intolerance by singing the lower tetrachord of the bīdād in the higher octave. The closing textless melisma (tahrīr) expresses the complex feeling of bīdād through a rising sequence that simultaneously depicts increasing intolerance and anger while imitating the act of sobbing.

The sudden collapse, represented in a complete rest at the end of the third verse, is very effective. A feeling of hope emerges here and some kind of solution to the sorrow is offered in the following verses: wine and music.

This feeling of resolution is further strengthened by the last verse, an insight into the reason for all these hardships:

While, in the poem, this seems to be a relief, Alīzādeh's quasi-cyclic form, represented in the return to the polyphonic setting of the first two verses, appears to emphasize awareness of the perceived tyranny and injustice, as opposed to the relief offered by wine and music.

Persian musical modernity revisited

In a brief YouTube video, apparently an excerpt from a royal meeting in the decades before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Mohammad Rezā Shāh Pahlavī appears very engaged in what seems to be the last moments of a debate with Queen Farah Dībā, articulating his deep concerns around the political responsibilities of Persian music. While he expresses admiration for Iran's art, music, and culture, he voices dissatisfaction with the passive role musicians played during the country's occupation by Russian and British forces in the Second World War. His poignant query, “During the time when Iran was occupied by the Allied soldiers, what sāz [instrument/tune/mode] did we go to war with?” reflects a profound concern about Persian music's role in real-world politics, especially given Iran's situation in a world dominated by Western powers. This concern highlights the perceived necessity that music engage with the outer world, politics, and Iran's geopolitical landscape, which most musicians neither appreciated nor responded to at the time. The idea of musical realism, as conceptualized in the Shāh's question, serves as a form of resistance and means to engage with a modern world shaped both militarily and, more significantly, epistemologically and aesthetically by Western influences.Footnote 47

The anxiety around the missing social and political contributions of Persian music reflects deeper concerns about Iran's situation in the modern world. While never officially colonized, Iran nevertheless grappled with foreign invasions such as the Russo-Iranian wars (1804–13 and 1826–28) and the war with Britain (1856–57), leading to territorial losses and foreign interference. The Anglo-Russian agreement of 1907, for instance, “divided Iran into three zones: a British zone of influence in the south-west, a Russian zone in the north, and a neutral zone in the remaining part of the country,” so that Iran entered the modern world through its “traumatic discovery of the European ‘other’.”Footnote 48 The modernization efforts that followed the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–11) sought to address this “trauma” and facilitate political stability, economic growth, and national security through modernizing all sectors of Iranian society.Footnote 49 The significance of music's engagement with the external world must be understood within this historical anxiety about Iran's place in the modern world.

In this context, the expectation of fundamental reform or a restructuring of symbolic order in Iranian music parallels those sought in society at large. A belated musical response to modernizing efforts in society seems to be the realistic, representational approach to the text-music relationship that occurred in the existential despair of the post-Islamic Revolution moment, reflected in the works of Alīzādeh, Meshkātīān, and the next generation of tasnīf-makers influenced by them. This development in Persian music history is significant, as it offers a new relationship between “sāz” and the outer world. This representational turn is crucial, as it expands the music-world relationship from traditional roles, such as dance and rituals, to the more fundamental level of musical materials and sounds themselves, integrating these into life and the world. This is a significant way through which the musical and extra-musical blend, or, as Lawrence Kramer suggests, “culture enters music, and music enters culture, as communicative action.”Footnote 50 This integration allows music to reflect the communal, social, and political life, and this is why recent attempts to make Persian music more responsive to the external world can be considered the start of a shift in the meaning of Persian classical music.

Describing a similar shift towards worldly matters in Western music around 1600, Daniel Chua contends that this musical modernity brought a change in the nature of music, grounding it in the natural. Drawing on Max Weber, Chua sees modernity's identity intertwined with a “disenchanted,” desacralized world, and the naturalization of music as a symptom of this transformation.Footnote 51 The modern relationship between music and the external world – or, as Chua claims, the alliance of music and nature – marks a profound shift in music history and “lies at the epicenter of an epistemological earthquake” that no longer understood nature as confined within the bounds of the supernatural, but rather as a standard against which knowledge is assessed.Footnote 52

This representational shift is highly significant in Persian classical music, as it established a novel text-music relationship and emerged from a negotiation with the inner resources of the music tradition. This shift shows how musical materials, already enriched with cultural meanings, can engage with the external world and reflect a dynamic awareness of the historical contexts in which music is created. Such a transformation has been achieved not through static acceptance or outright rejection of tradition, but through a creative balance between the two. The creative negotiation has led to a strong determination to create deeper stylistic differences that – as exemplified in the three tasnīfs examined above – can redefine the conventional features of Persian music to meet modern expressive demands, adapt to contemporary contexts, and remain relevant to modern audiences.

Drawing on Tomlinson's perspective that European musical modernity entailed some “form of a certain deafness, of a framing of others’ answers as an expression of their inability to answer at all,” it can be posited that Persian musical modernity exhibits deep engagement with both the internal dynamics and external forces of its musical tradition.Footnote 53 This engagement is characterized by a deliberate redirection of symbolic orders towards a realism informed by Western musical developments such as text-painting, while simultaneously exploring the intrinsic potentials of its own heritage. Such reconfiguration of musical meaning is pivotal to the unfolding of modern subjectivity. McClary's insights on a parallel shift in Western music during the 16th century, particularly in the emergence of the madrigal (an originally Italian musical genre for polyphonic voices, with heightened sensitivity to musical realism) illustrate this transformation. The shift mirrors and amplifies the concept of subjectivity “verbally manifested” through the Cartesian Cogito: the emergence of a modern subject, one possessing a unique relationship with reality, wherein, as Descartes put it, human beings are “the masters and possessors of nature.”Footnote 54 In Chua's view, music was requisitioned to serve the “rhetorical will” of the modern human subject.Footnote 55 From this perspective, music's representational engagement with text, and thereby with the external world, signals a shift in both music's structure of meaning and the “self-conscious construction in music of subjectivities,” marking a profound philosophical shift in the understanding and expression of human experience through the medium of music.Footnote 56

Conclusion

Hossein Alīzādeh and Parvīz Meshkātīān's innovative approaches to the text-music relationship in Persian classical music represent a significant paradigmatic transformation. Characterized by “musical realism,” this transformation strived to engage with the external world through music, marking a departure from approaches prioritizing Western notions of musical autonomy by maintaining Persian music's commitment to its inner structure. This shift signifies a deeper engagement with the socio-political context of Iran, reflecting the anxieties and aspirations of a nation navigating its place in the modern world. Contrasting this development with Western narratives of musical modernity reveals that Persian musical modernity requires a unique framework that acknowledges its historical trajectory and cultural specificity. Analysis of representational tasnīfs by Alīzādeh and Meshkātīān illustrates how these composers draw on the rich traditions of the radīf while introducing novel elements to create music that realistically responds to textual meanings.

This new approach is not merely a stylistic innovation; it is a profound reconfiguration of the symbolic order of Persian music, reflecting a deliberate redirection towards realism and engaging with life and the world in a way that integrates cultural meanings with musical materials. This engagement opens a dialogue between music and its broader socio-political context, suggesting a new direction for Persian classical music that resonates with contemporary realities. In other words, the representational turn in Persian music, as exemplified in the works of Alīzādeh and Meshkātīān, offers a new relationship between “sāz” and the outer world, expanding the music-world relationship from traditional roles (ritual, dance, etc.) to the fundamental level of musical materials and sounds themselves.

In conclusion, this innovative engagement with the external world through music, drawing on both the inner resources of the Persian musical tradition and the influences of Western musical developments, signifies a shift in the understanding and expression of human experience through the medium of music. The vocal works of Alīzādeh and Meshkātīān thus herald a new phase of Persian classical music, one more deeply intertwined with the realities of the modern world.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Mary Ingraham, David Gramit, Michael Frishkopf, Mostafa Abedinifard, Behrang Nikaeen, and Katherine Brucher, and the reviewers of Iranian Studies for their invaluable comments and insights at various stages of writing this article. I also extend my thanks to Hadi Sepehri for assisting me with access to the notation for the musical examples discussed in this article.