Introduction

Along with social class, religion has been one of the most important factors structuring major divisions in societies and is known to shape voting behaviour in important ways (Lazarsfeld et al. Reference Lazarsfeld, Berelson and Gaudet1944; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1979). However, over the course of the twentieth and early twenty-first century, the presence and importance of religion in social life has strongly decreased (Bruce Reference Bruce2011). Across established democracies, citizens’ membership in churches and their attendance of religious services have plummeted (see, e.g., Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff, Roßteutscher, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis-Beck2017a; Wilkins-Laflamme Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016a), and the decline has been argued to have further accelerated in the past twenty years (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2021).

The secularisation observed in Western societies has motivated scholars to examine whether religion is still influencing citizens’ vote choices (Elff Reference Elff2007; Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff, Roßteutscher, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis-Beck2017a; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2020; Raymond Reference Raymond2011; Tilley Reference Tilley2015). This literature usually analyses one of three aspects of this change. The first aspect is the decline in size of the religious section of the population, the second aspect is a (potential) change in the vote choices of those who are (still) religious, and the third aspect is a (potential) change in turnout among religious citizens (Best Reference Best2011; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2020; Knutsen Reference Knutsen2004). However, change in the divide between religious and non-religious voters is less often analysed. A rare exception is Putnam and Campbell (Reference Putnam and Campbell2012), who argue that in the US bonds between specific religious denominations and specific parties have weakened over time and been replaced by an opposition between secular and religious sections of society. Along the same lines, Wilkins-Laflamme (Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016b) shows evidence of a growing attitudinal polarisation between the religiously affiliated and the unaffiliated in Great Britain. If such changes characterise modern democracies more broadly, it is likely that the divisions between different denominational groups weaken while at the same time the opposition between religious and non-religious individuals grows stronger. In this paper, we examine whether there is evidence of polarisation in the electoral behaviour of religious and non-religious voters in Western Europe.

We pursue a systematic and comparative analysis of the transformation of religious cleavages in a broad set of West European countries over the last two decades. To this purpose, we combine individual-level data from the European Social Survey (ESS) about voters’ social characteristics and their party choices (European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure Consortium 2025), with party-level data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) about parties’ political positions relevant to religious-secular cleavages (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). Even though these data sources cover a wider set of countries, we focus on Western Europe because that is the region where most of the evidence about the importance of religious denomination for explaining voters’ choices originates (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2004; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967). Instead of relying on a fixed classification of parties into party families, we use the CHES data to characterise parties in terms of their political positions with regard to traditional values and religious principles. This allows to disentangle changes in citizens’ political preferences from changes in the political ‘supply-side’, i.e., changes in the positions of political parties.

Our results show that changes in of the relation between religion and voting are quite multifaceted: We find an increased polarisation between Christians and the non-religious, but we also find that voting patterns of non-Christians religious voters become more similar to those of the non-religious. Furthermore, we find that Catholics become less inclined to vote for parties that emphasise religious principles than Protestants.

Change in religious cleavages?

Studying party systems and voting behaviour in established democracies in the 1960s, Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) posited that individuals’ choices were to a large extent driven by their positions on social cleavages, such as their place of living, their social class, or their religious denomination. The observation that election outcomes are increasingly volatile (Chiaramonte and Emanuele Reference Chiaramonte and Emanuele2017), however, has led scholars to argue that social cleavages are no longer structuring voters’ choices to the same extent (Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992).

Scholars who have more specifically focused on the effect of religion over time, however, have nuanced the idea of a strong across-the board decline of its impact on the vote. Knutsen (Reference Knutsen2004, p. 108), who studies the impact of religious denomination on the vote choice in Western Europe between 1970 and 1997, finds that the association between religious denomination and the vote choice is ‘fairly stable’. Elff (Reference Elff2007, p. 281), who analyses over-time change in the role of class and religious cleavages in Western Europe, concludes that the latter are ‘more stable’ than the former. Work analysing the role of religion in single countries or a smaller set of countries similarly concludes that religion continues to structure voters’ electoral choices in important ways (Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2011; Raymond Reference Raymond2011; Tilley Reference Tilley2015).

Such findings, however, should not be taken to imply that religion still structures voting in exactly the same way as it did in the 1960s. Best (Reference Best2011) has drawn attention to a distinction between changes in terms of the number of religious individuals and changes in how religious voters choose parties. The process of secularisation has led to a decline in the number of citizens who still consider themselves religious or attend church regularly (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2021). As a result, even if the effect of religion on the vote among religious voters has persisted, the decline in the number of religious voters has reduced the extent to which parties can draw on the support of a religious base. Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2020) makes a similar distinction between structural and behavioural effects, and adds that changes in the role of cleavages can also be driven by different mobilisation patterns. Regarding the religious cleavages, Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2020, pp. 72–73) argues that the broadening up of religious parties has ‘weakened their religious profile’Footnote 1 , which ‘may result in a feeling among religious people that their values and opinions are less represented, which eventually may lead them to abstain.’ That is, parties’ reactions to the change in their electoral fortunes as a result of secularisation may lead them to take positions that further diminish the influence of religion on politics.

The transformation of religious cleavages cannot be fully understood without taking into account parties’ ideological positions. After all, for group voting to occur, it is essential that parties differ in their issue positions and ideological outlooks and therefore in their attractiveness for different groups (Elff Reference Elff2009; Thau Reference Thau2019). A number of contributions already provide evidence that the positions taken by parties shape the strength of the effect of religion on the vote. For example, Jansen et al. (Reference Jansen, De Graaf and Need2012) show that the strength of the effect of church membership on the vote in the Netherlands is conditioned by parties’ positions on traditional and moral issues. Combining data from the Eurobarometer with data from the Comparative Manifesto Project, Elff (Reference Elff2009) provides evidence that positions on traditional ways of life condition the influence of church attendance on voting in many West European countries. Gomez (Reference Gomez2022) furthermore shows that the divergence in parties’ positions on moral issues can have long-term effects. In particular, he finds that the effect of religiosity on vote choice is stronger for individuals who were politically socialised at a time when parties took clearly distinct positions on moral issues. Finally, the contributors to Political Choice Matters (Evans and De Graaf Reference Evans and De Graaf2013) provide evidence that changes in the relation between religious (non-)membership and voting can be explained by changes in parties’ political positions.

To summarise, previous work provides important insights into the complexity of the political consequences of secularisation. However, one important type of change has not received much attention in the comparative political science literature on the topic: the possibility that differences based on religious denomination are disappearing while those between religious and non-religious individuals gain importance. In the US context, Putnam and Campbell (Reference Putnam and Campbell2012) point to the fact that distinctions between Protestants and Catholics have given way to a growing opposition between those who are religious and those who are not. Here, we aim to test whether a similar trend of a growing a religious/non-religious divide is visible in Western Europe during the past two decades. To this purpose, we consider changes in the impact of religious denomination and differences between denominational groups, as well as changes in the role that religiosity has on the choices of Christian voters.

In the next section, we discuss the theoretical possibility of a polarisation between religious and non-religious voters in Western Europe in more length, and present the hypotheses that follow from this theoretical discussion.

Theory and hypotheses

Even though the possibility of a polarisation between religious and non-religious voters has not received much attention in the literature on voting behaviour, a number of sociological studies indicate that the trend of secularisation has coincided with a polarisation in public opinion in Western-Europe over questions of morality.

In particular, Achterberg et al. (Reference Achterberg, Houtman, Aupers, Koster, Mascini and van der Waal2009) show that as the number of faithful has decreased, public attitudes about the role of religion in public life have become more polarised. Wilkins-Laflamme (Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016b, p. 649) observes a similar pattern in Britain, where the ‘population does appear to be cleaving more and more into two distinct groups when it comes to religion: an unaffiliated majority characterised by very low levels of beliefs and an actively religious minority generally more fervent in its beliefs and views’. Studying the gap in personal religious beliefs between the religious unaffiliated and affiliated in a large set of Western democracies Wilkins-Laflamme (Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016c) furthermore finds evidence that this gap is wider in countries where secularisation is more advanced. In a similar vein, various authors point to the growing opposition between the religious and the non-religious over moral and cultural issues such as abortion and homosexuality in Europe (Achterberg et al. Reference Achterberg, Houtman, Aupers, Koster, Mascini and van der Waal2009) and the United States (Putnam and Campbell Reference Putnam and Campbell2012). Studying differences in ‘family values’ – which include attitudes on sexuality, abortion, and gender equality, Wilkins-Laflamme (Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016c) also documents that the opinions of the religiously unaffiliated and affiliated differ more strongly in settings that are more secularised. As an important nuance, her findings indicate that polarised public opinion in contexts of secularisation is mostly due to the unaffiliated being less religious and more liberal, and not due to the affiliated being more religious and more conservative. Such findings indicate that secularisation can be a breeding ground for a polarisation between religious and secular people. As traditional religious values and beliefs lose their dominance in society and politics, and as government policies and public institutions become more tolerant towards post-traditional lifestyles (e.g., by allowing divorce, pre-marital sex, and homosexual partnerships or marriages; Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff, Roßteutscher, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis-Beck2017a), religious people may become more opposed to such societal change. In terms of voting behaviour more specifically, work from the Canadian context provides some evidence of polarisation between the religious and the non-religious. In particular, the importance that individuals attach to religion in their lives is increasingly connected to their vote choice – with those for whom religion is very important increasingly supporting the Conservative party (Wilkins-Laflamme Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016a).

It is important to keep in mind that religious cleavages in Europe take two major forms: (1) as an opposition between religious and secular segments of society and (2) as divisions between different denominational groups (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1979), in Western Europe mostly between Catholics and Protestants or between mainline Protestants and revivalist movements. Historically, countries with a predominantly Catholic population were characterised by cleavages between a nation-building secular elite and the transnational organisation of the Catholic Church. This divide did not develop in countries where (Lutheran) Protestantism was dominant, since the Reformation led the monarchs of these countries to become the heads of the (Lutheran) church. In countries where neither Catholicism nor Protestantism could assert dominance, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, nation-building was mostly driven forward by Protestant elites who faced a Catholic opposition, similar to the secularist nation-builders in Catholic countries (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967; Madeley Reference Madeley1982; Madeley Reference Madeley2003).

In terms of the differences between religious and secular segments of the population, the literature argues that secularisation can either lead to a narrowing or to a widening of these divisions. In contrast, the expectations about divisions between denominational groups are quite uniform. The divisions within the religious segment should weaken (see, e.g., Jansen et al. Reference Jansen, De Graaf and Need2012; Knutsen Reference Knutsen2004), irrespective of whether religion becomes less important or whether there is religious-secular polarisation. The idea behind this expectation is that Catholics and Protestants have become allies in a struggle with their secular opponents.

The relation between social cleavages and voting is commonly conceived as an association between voters’ social characteristics or group memberships and their vote choice. For religious voting, research often examines support for the party families of Christian Democratic parties, confessional parties, or of conservative parties (e.g., Elff Reference Elff2007). Yet, the ideological positions of parties within the same family may vary, and individual parties may also change their stances over time in order to adapt to a changing composition of the electorate or as a means to attract new voters (Elff Reference Elff2009; Gomez Reference Gomez2022). To account for such positional changes, we frame our hypotheses not in terms of party families but in terms of ideological dimensions.

Our first pair of hypotheses concerns divisions between members of any Christian church and religious non-members, i.e., those who are not members of any religious group. We thus focus on Christian religious individuals, which we distinguish from members of non-Christian religious communities. Parties in Western Europe with conservative positions with regard to religious principles usually do so by explicitly espousing Christian values. It is therefore possible that these two groups differ in their preferences for these parties. The common expectation in research on changes in religious voting in Western Europe holds that secularisation contributes to the general decline of social cleavages. This expectation leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (Religious-secular convergence) Christian voters and non-religious voters become similar in terms of their preferences for parties with conservative positions or positions that emphasise religious principles.

If instead, as found in the US context (Putnam and Campbell Reference Putnam and Campbell2012), secularisation in Western Europe leads to an increase in religious-secular polarisation, we should observe the opposite pattern. The hypothesis thus reads as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (Religious-secular polarisation) Christian voters and non-religious voters become more different in terms of their preferences for parties with conservative positions or positions that emphasise religious principles, where the support among Christians increases and/or the support among the non-religious decreases.

It should be noted that while the confirmation of one of these two hypotheses implies the refutation of the other, this does not mean that H1 is the null hypothesis with respect to H2 or vice versa. There is a single null hypothesis with respect to both of these two, i.e., that no trend occurs in the religious-secular divides, and its rejection still leaves open the direction of the change.

Our third hypothesis concerns divisions between the main Christian Denominations in Western Europe, i.e., the Catholics and the Protestants. We have a single hypothesis here because the only prediction that we can derive from the literature is that Catholic–Protestant differences have been waning over time (if not disappeared altogether):

Hypothesis 3 (Catholic-protestant convergence) Catholic and Protestant voters become more similar in terms of their preferences for parties with conservative positions or positions that emphasise religious principles.

The idea behind this hypothesis is that Catholics and Protestants may have become allies in the struggle with their secular opponents. There already is some evidence that differences in voting behaviour of different denominational groups are diminishing in Canada. In particular, the analyses of Wilkins-Laflamme (Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016a) indicate that differences in the party preferences of Catholics and mainline Protestants have grown smaller over time (for evidence on the Netherlands, see De Graaf et al. Reference De Graaf, Heath and Need2001; Jansen et al. Reference Jansen, De Graaf and Need2012 for Germany, see Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2011; Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2017b).

The hypotheses discussed so far concern only one of the three dimensions of religion (Olson and Warber Reference Olson and Warber2008) – belonging. The second dimension – which captures believing – is quite difficult to measure reliably. However, the third dimension of behaving can well be examined using survey data. More precisely, it is possible to examine reported behaviour, either with respect to the frequency of religious attendance (or church attendance for Christians) or with respect to the frequency of prayer. With respect to this dimension of religious behaviour, we can also formulate a convergence and a polarisation hypothesis. The convergence hypothesis rests on the notion that secularisation not only implies that the religious segment of society is shrinking (i.e., those who belong), but also that religion becomes less salient for those who are religious (i.e., those who behave religiously):

Hypothesis 4 (Convergence in terms of religious behaviour) The level of religious behaviour becomes less consequential for voters’ preferences for parties with conservative positions or positions that emphasise religious principles.

The idea that secularisation leads to a religious-secular polarisation can also be adapted to the dimension of religious behaviour: Those who are more engaged in religious behaviour may react more strongly to politics becoming more secular and social morals becoming more permissive, or, conversely, those who are less engaged in religion may be less averse to a secular society. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (Polarisation in terms of religious behaviour) The level of religious behaviour becomes more consequential for voters’ preferences for parties with conservative positions or positions that emphasise religious principles. The support among those with high level of religious behaviour increases and/or the support among those with low level of religious behaviour decreases.

Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we combine individual-level data on political preferences, religious/secular orientations and social characteristics with data on parties’ political positions. The individual-level data come from round 1 through 10 of the ESS (European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure Consortium 2025). The party level data come from the CHES 1999–2019 Trend File (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022).

Individual-level data

The ESS consists of several waves of multinational surveys that are organised in so-called rounds (European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure Consortium 2025). There is a core questionnaire shared by all rounds, but each round contains an additional set of survey questions. Surveys are conducted every two years, the first starting in 2002. It should be noted, however, that the year of fieldwork varies a bit between countries so that some samples are from even-numbered years and others are from odd-numbered years. The latest year of field work of Round 10 of the ESS, which is the last one included in the analyses of the paper, is 2022.

By using the ESS data, we can study changes in religious voting for a period of two decades. Even though the secularisation of Western Europe has arguably started long before 2002, descriptive analyses that are reported in the Online Appendix show not only that the process of secularisation continues during the time period covered by the data, but also that countries differ in their levels of secularisation. The core questionnaire of all ESS rounds includes information relevant for our hypotheses, namely their religious memberships, behaviour, as well as party preferences. Furthermore, it includes information about occupational class and year of birth, which are important confounders.

Our operationalisation of religious membership rests on the responses to two questions asked in the ESS surveys: (1) a yes-no question whether respondents belong to any religion or denomination and (2) a follow-up question about which religious denomination or community respondents belong to, asked only of those who gave a positive answer to the first question. From the responses of these questions we construct two variables: (1) a dichotomous variable that contrasts Catholics and Protestants and (2) a variable with the three categories ‘Christian’ [denomination or religious group], ‘Non-Christian’ [religious group or denomination], and ‘No religion’ (i.e., no membership in any religious group or denomination).Footnote 2

The ESS provides two behavioural measures of religious behaviour: One measure rests on answers to a question about how often respondents attend religious services apart from special occasions (i.e., about church attendance for members of a Christian denomination). Another measure uses answers to the question about how often respondents pray apart from religious services. The response categories for both questions are identical: (1) ‘Every day’, (2) ‘More than once a week’, (3) ‘Once a week’, (4) ‘At least once a month’, (5) ‘Only on special holy days’, (6) ‘Less often’, and (7) ‘Never’. We collapse attendance of religious services into the five categories (1) ‘Never’, (2) ‘Rarely’, (3) ‘Holidays’, (4) ‘Monthly’, and (5) ‘Weekly (or more)’ to avoid problems for quantitative analysis created by sparsely filled categories. We collapse the frequency of prayer into the five categories (1) ‘Never’, (2) ‘Less often’, (3) ‘Every Month’, (4) ‘Every week’, and (5) ‘Every day’.

As an indicator of party preferences, we use the answer to the question about respondents’ vote choice in the last election. For obvious reasons, the response categories of vote choice recall vary between country samples and ESS rounds. We refrain from collapsing these categories into a general scheme. Instead, we retain the original response categories and bring the data in a ‘stacked’ format, where each combination of respondent and party corresponds to a different row in the dataset. Recalled vote choice in this stacked dataset is represented by a binary variable that equals 1 if the respondent recalls to have voted for the party relevant for the dataset row, and 0 otherwise. Retaining the original party codes allows us to merge the individual-level data with the party-level data discussed in the next section and analyse these combined data using discrete-choice models.

Given that class is historically a key determinant of the vote choice in Western Europe, and still shapes voting in important ways (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018; Langsaether Reference Langsæther2019), we include socio-economic class as an individual-level control variable. To construct this variable, we use the ISCO-88 encoded answers to questions about respondents’ and their partners’ occupations, as well as about their status of being self-employed and the number of employees. To achieve the best balance between detail and parsimony, we use an 8-category variant created by collapsing the two categories of self-employed in the 9-category Oesch class schema (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). We use either respondents’ own occupation, if they are economically active, or their partners’ occupation, otherwise. The resulting class schema has the categories (1) production workers, (2) service workers, (3) clerks, (4) socio-cultural experts and professionals, (5) technical experts and professionals, (6) managers and administrators, (7) self-employed, and (8) farmers and primary sector labourers.

Party positions

The Chapel Hill Experts Survey (CHES) is our source of data on parties’ political positions, in particular its 1999–2019 trend file (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). The CHES provides expert-based estimates of parties’ positions on a variety of dimensions. Of these, the GAL–TAN dimension, religious principles dimension and Social Lifestyle dimension are the relevant ones for our hypotheses, while the economic Left–Right dimension and the immigration policy dimension are control variables.

The GAL–TAN dimension is most often discussed as the major political dimension beside economic left–right (see e.g., Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). On the GAL–TAN-scale, the value 0 corresponds to a ‘Libertarian/Post-materialist’ position, while the value 10 corresponds to a ‘Traditional/Authoritarian’ position.Footnote 3 While this dimension has the advantage of being available for the whole time range from 1999 to 2019, it combines traditionalist versus permissive positions with regard to social ways of life and authoritarian/nationalist versus libertarian positions with regard to political rights and civil liberties – two dimensions that affect religious voters differently (Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022).

For our hypotheses, the Religious Principles dimensionFootnote 4 is obviously the most relevant one. Yet, while it matches our purposes much better than the GAL–TAN dimension, it is only available from 2006 to 2019. On the Religious Principles scale, the value 0 indicates that a party ‘[s]trongly opposes religious principles in politics’, while the value 10 indicates that a party ‘[s]trongly supports religious principles in politics’ (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). Since religion is typically invoked to justify traditionalist restrictions on the way of life, the Social Lifestyle dimensionFootnote 5 is also relevant for our hypotheses. It is also only available for the time range from 2006 to 2019. The value 0 on the Social Lifestyle scale indicates that a party ‘[s]trongly supports liberal policies’ while the value 10 indicates that a party ‘[s]trongly opposes liberal policies’ (where ‘liberal’ is to be understood in the US American sense of supporting permissive lifestyles).

In estimating the connection between religion and party positions on the Religious Principles dimension, we also account for the positions that parties take on other dimensions. Positions on the Economic Left–Right dimension are available for the same time range as positions on the GAL–TAN dimension. On the Economic Left–Right scale, a value of 0 indicates an ‘extreme left’ position, a value of 5 indicates a ‘centre’ position, while the value of 10 indicates an ‘extreme right’ position. Positions on the Immigration Policy dimension are available in the same restricted time range as positions on the Religious Principles dimension.Footnote 6 On the Immigration scale, the value 0 indicates that the party ‘[s]trongly favo[u]rs a liberal policy on immigration’, while a value of 10 indicates that it ‘[s]trongly favo[u]rs a restrictive policy on immigration’. All political position scales just discussed allow us to include 12 West European countries into our analysis: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, (West) Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden.Footnote 7

The CHES data file contains a classification of the parties into party families, which allows us to examine how well the various political dimensions are able to capture what distinguishes parties which traditionally target Christian religious voters from other parties. We focus on the four right-of-centre families distinguished in the CHES: confessional parties, the Christian democratic parties, conservative parties and radical right parties, and combine all other party families in the category of ‘other parties’. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the positions of parties from the confessional, Christian democratic, conservative and radical right families as well of the remaining party families on the GAL–TAN, Religious Principles, Social Lifestyle, Economic Left–Right, and Immigration dimensions in the form of box plots.Footnote 8

Figure 1. Distribution of political positions of party families on the Economic Left–Right, GAL–TAN, Religious Principles, Social Lifestyle, and Immigration positions.

Source: Chapel Hill Expert Survey data, 1999–2019 edition.

Figure 1 clarifies that the Religious Principles dimension performs best in distinguishing the confessional and Christian democratic parties from the other right-of-centre parties as well as from other parties. On all other dimensions, there is at least one party family other than these two that has an equally conservative position. On the GAL–TAN dimension, the radical right family is about equally conservative as the confessional party family, and on the Social Lifestyle dimension the radical right family takes similarly conservative positions as the family of confessional parties. The Christian democratic parties, on the other hand, appear more liberal than confessional or radical right parties, and are on par with the conservative party family.

On the Economic Left–Right dimension, the conservative party family takes more pronounced right-of-centre positions than any of the other party families, followed closely by the party of the radical right, while the confessional and Christian democratic party families take positions that are situated between the radical right family and the other party families. A similar pattern can be observed when looking at the positions of the party families on the Immigration dimension, though in this case, it is the radical right family that takes positions distinct from those of the other parties. Only the Religious Principles dimension orders the party families in a way that is consistent with common understanding of the nature of these party families. The confessional parties, which were usually formed in opposition to a secularised society and polity and appeal to the most devout Christian voters, take the most conservative position on the Religious Principles dimension, followed by the Christian democratic parties, which, as the name of the party family (and of many of its members) suggests, appeal to Christian voters, though by taking less extreme positions. Conservative and radical right parties take fairly centrist positions on this dimension, while all other parties are placed towards the progressive end of this dimension.

While both confessional and radical right parties tend to have ‘conservative’ positions on the Social Lifestyle dimension, the Religious Principles dimension is able to distinguish between these two party families in so far as only the confessional parties have the most religious positions on the Religious Principles dimension. This descriptive analysis of parties’ positions on different dimensionsFootnote 9 motivates us to focus mostly on the Religious Principles dimension in our analyses.

The CHES is not the only source from which parties’ political positions can be derived. The most notable alternative is the MarPor dataset (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024), which is based on the electoral manifestos of most if not all important parties in Western democracies that were published since the end of World War II. It offers the advantage to be based on political texts rather than more or less subjective assessments by experts. However, the standard coding schema used by the MarPor project and its predecessor, the Comparative Manifesto Project (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001), does not make it easy to disentangle the Religious Principles dimension from other political dimensions such as those related to immigration.Footnote 10

Combining individual-level data with party-level data

The ESS and CHES data use different codes to identify parties, and for some of the smaller parties, the ESS and the CHES data even use different labels. Furthermore, in the ESS data, the responses to the vote recall question are collected into country-specific variables. For example, in the ESS round 1 dataset, there is a variable named prtvtat that contains the coded responses on the vote recall question from Austria, a variable prtvtbe that contains responses from Belgium, and further variables for each of the other countries included in this ESS round. For each of these variables, codes for the parties start with the number one. In order to be able to join the CHES data with the cumulated ESS data, we manually created a dataset with a correspondence between the party identifiers used in the CHES and the combination of ESS round number, country, and party code for each of the ESS datasets.Footnote 11

Before joining the ESS data with the CHES data, we combined the datasets of the individual ESS rounds (after harmonising the coding of several variables across ESS rounds) and reshaped into a ‘stacked’ or ‘long’ format. In this format, each respondent is represented by several rows, with a row for each party he or she could have voted for. We then joined this long format ESS data with the correspondence table for party codes. In the merged dataset, each row contains a respondent identifier, the individual-level variables of interest from the ESS, a party identifier, and the political positions of the parties – taken from the CHES. Thus, we made sure that the recalled votes are matched with the political positions of the parties that the respondents faced in the last election before fieldwork.Footnote 12

Modelling the impact of religion and religiosity on voting

Our hypotheses involve changes in the effects of religious denomination and/or religiosity on vote choice. To model the effects of religious cleavages, we rely on discrete choice modelling (for a detailed description of the approach, see Elff Reference Elff2009). This has two main advantages. First, the approach allows us to compare patterns of voting between countries and over time. The alternatives from which voters choose in elections vary between countries for obvious reasons; no party organisation runs candidates in more than a single country. And in some cases there are even parties that compete only in a part of the country, e.g., the SNP (only in Scotland, but not in the rest of the Britain) or the CSU (only in Bavaria, but not in the rest of Germany). Furthermore, the set of alternatives often changes over time within countries, e.g., when new parties emerge, established parties decline into obscurity, or are outright dissolved (such as the Italian Democrazia Cristiana) or when former competitors join forces through party merger (such as the Dutch ARP, CHU, and KVP). A traditional way of dealing with this variation in the sets of alternatives that voters are faced with, is to group parties into party families. Thus, for an analysis of religious voting one could use a classification in Christian and religious parties, on the one hand, and secular parties, on the other hand. As Figure 1 has clarified, however, there is much variation in parties’ positions on relevant dimensions within party families. Discrete choice analysis does not necessitate an a priori categorisation of parties, and instead focuses on what attributes of the parties are relevant for voters’ choice between them (Elff Reference Elff2009).

The second advantage of our modelling strategy is that we can take over-time changes in the ideological profiles of parties into account (Elff Reference Elff2009). A religious conservative party of the past may transform itself into a more moderate one, or a moderate party into a conservative one. Such changes may occur gradually, so that working with fixed party family memberships may lead to erroneous conclusions regarding voters’ changing preferences when the parties rather than the voters change, while a re-classification of a party may exaggerate the pace of an ideological change.

What creates the link between parties’ positions and their electoral choices in our modelling strategy is the idea that a voter will choose the party with the highest utility, where the utility of a party for the voter depends on how close or distant the party’s position is from the voter’s position. While we only know the positions of the parties and not of the voters, we can estimate the average position of members of a particular group, which is enough for our purposes. For example, if there is a position on the Religious Principles dimension such that the probability of a party being chosen by Catholic voters decreases with the party’s distance from this position, we use this as an estimate of the average position of Catholic voters on the Religious Principles dimension.

We base our modelling strategy on McFadden’s conditional logit model, which has the advantage of admitting the sets of alternatives to vary between contexts and thus making a comparative analysis possible (McFadden Reference McFadden and Zarembka1974). We use conditional logit models extended by nested random effects at the party level and the level of the time points of the surveys, to account for differences between parties that affect choice probabilities apart from parties’ positions, e.g., the attractiveness of their candidates.Footnote 13

Results

Having described the data and introduced our estimation strategy, we now turn to the tests of the hypotheses introduced in Section 3. We first examine whether Christian voters and non-religious voters converge in terms of their preference for parties with religiously conservative or secular positions (Hypothesis 1) or whether there is evidence of polarisation between them (Hypothesis 2). We then examine whether differences between Catholics and Protestants are (also) declining (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we examine whether the influence of religious behaviour on voting declines among Christians (Hypothesis 4) or whether a polarisation between religiously active and inactive Christians occurs (Hypothesis 5).

As indicated previously, the Religious Principles dimension appears best suited to distinguish parties that appeal to (Christian) religious voters and parties that appeal to more secular voters, which is why we present results on this dimension only.Footnote 14

Within our discrete choice modelling framework, the group differences in voting behaviour are expressed by (first-order) interaction coefficients of dummy variables (that correspond to differences in group membership) with parties’ relevant political positions. Changes in these group differences then are expressed by (second-order) interaction coefficients of political position variables, group membership dummies, and a time variable. To better disentangle first-order from second-order interaction effects and to avoid numerical problems, we centre the time variable at the year 2010. For the same reason, we use deviation regressor coding for group memberships instead of dummy coding (Fox Reference Fox2008, 145). That is, observations in the baseline category receive a code of

![]() $ - 1$

instead of

$ - 1$

instead of

![]() $0$

.Footnote

15

$0$

.Footnote

15

Since we mostly distinguish between more than two groups, an interaction effect that corresponds to our hypotheses is represented by more than a single coefficient. We therefore rely on multi-parameter Wald tests in our analyses. These Wald tests can only uncover whether a change occurs, but not which direction it takes. Since coefficients of discrete choice models are difficult to interpret, we use visualisations instead of tables of coefficients to clarify the implications of the estimated models for our hypotheses.Footnote 16

Religious membership and voting

Our first two hypotheses state that as secularisation progresses, differences between members of a Christian religious group and non-members of any religious group (i.e., neither a Christian nor a non-Christian group) will either decline (Hypothesis 1) or increase (Hypothesis 2). If secularisation has been an ongoing process in most countries during our period of observation, we should find a three-way interaction effect of parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension, voters’ religious membership or non-membership, and time.

However, there is variation between countries in the level of secularisation.Footnote 17 One may thus argue like Franklin et al. (Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992) that some countries may be forerunners and others laggards in a general process. Following this argument, Hypothesis 1 implies that the more secular a country is, the smaller the voting differences related to religious membership are, while Hypothesis 2 implies that the voting differences related to religious membership increase with the level of secularisation. Instead of classifying countries as forerunners or laggards in the process of secularisation, we focus on the degree to which a country is secularised. As a measure of this degree, we use the proportion of people who are not members of any religious group. Both hypotheses then imply a three-way interaction of parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension, religious (non-)membership, and our measure of secularisation, however, with different signs of this interaction effect.

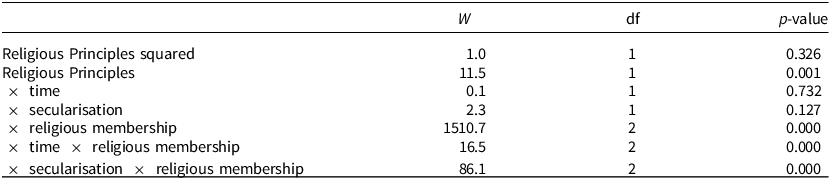

For an initial round of Wald tests, we constructed a model that contains not only the three-way interaction effects of parties’ positions and voters’ religious (non-)membership with time and with the level of secularisation, respectively. We also include the four-way interaction effect of all four of these variables to allow for the pace of change to vary with the level of secularisation.Footnote 18 The Wald tests for this full model (reported in the Online Appendix) indicate that the pace of change does not vary with the level of interaction.Footnote 19 Based on these results, we focus on a more parsimonious model excluding this four-way interaction. The results of the Wald tests for this more parsimonious model are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Wald tests of the effects of interactions of parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension with religious (non-)membership

Note: Tests conducted while controlling for parties’ positions on the Immigration and Economic Left–Right dimensions, respondents’ class positions, and the degree of secularisation of the countries.

Table 1 shows the results of Wald tests for the main effect and the interaction effects of parties’ positions on the Religious Principles with religious membership and time and with religious membership and the degree of secularisation. It indicates that positions on the Religious Principles dimension have a (statistically significant) main effect on the vote (

![]() $p = 0.001$

). This indicates that, net of group differences based on religious membership, voters either prefer more religiously conservative or more secular parties.Footnote

20

We do not obtain a statistically significant result for the test of the interaction of positions on this dimension with time or with the level of secularisation, suggesting that there is no general trend across groups in either direction. Much more important for our hypotheses are the results of the last three Wald tests: the test concerning the interaction of party positions on the Religious Principles dimension with religious membership and the test concerning the three-way interaction of party positions with religious membership and time and with religious membership and the level of secularisation. All these three tests result in a rejection of the null hypothesis (

$p = 0.001$

). This indicates that, net of group differences based on religious membership, voters either prefer more religiously conservative or more secular parties.Footnote

20

We do not obtain a statistically significant result for the test of the interaction of positions on this dimension with time or with the level of secularisation, suggesting that there is no general trend across groups in either direction. Much more important for our hypotheses are the results of the last three Wald tests: the test concerning the interaction of party positions on the Religious Principles dimension with religious membership and the test concerning the three-way interaction of party positions with religious membership and time and with religious membership and the level of secularisation. All these three tests result in a rejection of the null hypothesis (

![]() $p \lt.001$

). The results of our Wald tests thus indicate that there is a change in the relation between religious membership and voting, both over time and with different levels of secularisation. The tests do not indicate the direction of this change, however. Since the interpretation of coefficients in a complex discrete choice model is not straightforward, we use, in the following, illustrative diagrams to highlight the direction of change.

$p \lt.001$

). The results of our Wald tests thus indicate that there is a change in the relation between religious membership and voting, both over time and with different levels of secularisation. The tests do not indicate the direction of this change, however. Since the interpretation of coefficients in a complex discrete choice model is not straightforward, we use, in the following, illustrative diagrams to highlight the direction of change.

Figure 2a illustrates how a hypothetical party’s position on the Religious Principles dimension affects its chances to be chosen by Christian, non-Christian, and non-religious voters if it competes with another party with a centrist position (scale value 5) on this dimension, at different settings and at different times.Footnote 21 The top panels (Figure 2a) show the predicted probabilities of voting for a party with different positions at the midpoint of the period of observation (the year 2014) in three hypothetical countries with low, medium, and high levels of secularisation (with 10 percent, 50 percent, and 90 percent of the population without a religious membership). The bottom panels (2b) show the predicted probabilities for different points in time of a party with a moderately conservative position on the Religious membership dimension. Thus, Figure 2a illustrates how the groups defined in terms of religious (non-)membership differ in the way they evaluate parties positions on the Religious Principles dimension, and how these differences vary with the level of secularisation, while Figure 2b illustrates whether and in what direction these group differences change over time.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of Christian, non-Christian, and non-religious voters to choose a party depending on its position on the Religious Principles dimension.

Note: The predicted probabilities are computed from a conditional logit form for a hypothetical two party system, where the position of one party varies, while the position of the other party is fixed at the centre (scale value 5), and both parties have centrist positions on the Immigration and Economic Left–Right dimension. The voters’ occupational class is fixed to the class of clerks.

Figure 2a shows that while being more conservative on the Religious Principles dimension increases a party’s chances among Christians only slightly (other things being equal), while it decreases its chances among the non-religious considerably. Furthermore, it is also clear that the aversion of the non-religious towards parties with conservative positions on the Religious Principles dimension increases with the level of secularisation of a country: The downward slope of the probability curve for this group gets steeper as one moves from the left-hand panel (low level of secularisation) to the right-hand panel (high level of secularisation). It is remarkable how predicted voting tendencies change for those who are a member of a non-Christian religious group. When the level of secularisation is low, their voting patterns are indistinguishable from those of Christian voters. When the level of secularisation is high, however, they are even more averse to parties with conservative positions than the non-religious.

Figure 2b shows that the differences between Christian and non-religious voters increase over time, as do the differences between Christian and non-Christian religious voters. This dovetails with the finding that differences are larger in more secularised countries and is coherent with the notion that these changes are an outcome of a process of secularisation, in which different countries have attained different levels, but which is also still ongoing.

If one considers only the Christian and the non-religious voters, the results of this section indicate that the polarisation on religious-secular cleavages does not decline with secularisation. Quite the opposite, we find that polarisation increases on this type of cleavage. It should be noted, however, that the patterns of voting among those who are members of a non-Christian religion are more similar to those who are non-religious, which does not fit well with the notion of a general religious–secular cleavage. This is a quite surprising result, to which we give more consideration in the discussion section of this paper.

Catholic-Protestant differences and voting

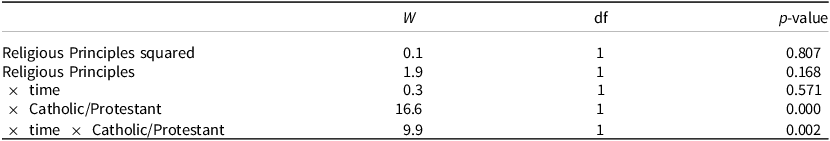

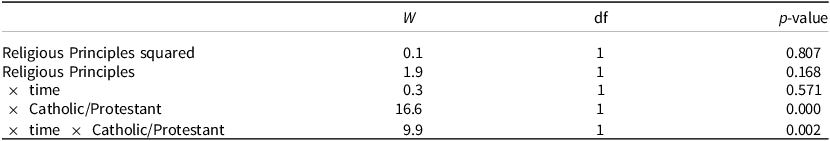

Hypothesis 3 states that Catholic–Protestant differences in Europe have been declining. To test this hypothesis, we look at the interactions of the membership in either the Catholic or Protestant churches with parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension, as well as the three-way interaction of Catholic/Protestant membership with party positions and time.

We conduct this test while controlling for respondents’ frequency of prayer as an indicator of the intensity of belief. The need for this control arises from differences between Catholics and Protestants to leave their respective churches if their faith weakens. If Protestants are more likely to leave, this group may end up being more religious and perhaps more conservative on aggregate.Footnote 22 In a first round of Wald tests we further control for the level of secularisation and the countries’ composition in terms of Catholics and Protestants.Footnote 23 We find that secularisation does not influence Catholic-Protestant differences (i.e., the pertaining interaction effect does not reach statistical significance), while the composition in terms of Catholics and Protestants does. We consequently drop the level of secularisation and conduct Wald tests for a more parsimonious model.

Table 2 shows the results of the Wald tests pertinent to Hypothesis 3.Footnote

24

The Catholic-Protestant difference in voting for parties regarding their positions on the Religious Principles dimension is highly statistically significant (

![]() $p \lt 0.001$

) as is the interaction of the Catholic-Protestant difference with time (

$p \lt 0.001$

) as is the interaction of the Catholic-Protestant difference with time (

![]() $\,\:p = 0.002$

). That is, we find strong evidence that differences between Catholics and Protestants change in their voting patterns. Figure 3 clarifies the direction of this change.

$\,\:p = 0.002$

). That is, we find strong evidence that differences between Catholics and Protestants change in their voting patterns. Figure 3 clarifies the direction of this change.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of Catholic and Protestant voters to choose a party depending on its position on the Religious Principles dimension.

Note: The predicted probabilities are computed from a conditional logit form for a hypothetical two party system, where the position of one party varies, while the position of the other party is fixed at the centre (scale value 5), and both parties have centrist positions on the Immigration and Economic Left–Right dimensions. The voters’ occupational class is fixed to the class of clerks, while their frequency of prayer is fixed to weekly.

Table 2. Wald tests of the effect of parties’ positions and their interaction with Catholic/Protestant church membership and time

Note: Tests conducted while controlling for parties’ positions on the Immigration and Economic Left–Right dimensions, respondents’ class positions, frequency of prayer, and the degree of secularisation of the countries.

The left-hand panel in Figure 3 illustrates how the predicted probability of voting for a party varies with its position on the Religious Principles dimension. The graph shows these probabilities for Catholics and Protestants who pray daily and are members of the occupational class of clerks. These probabilities are calculated for a hypothetical two-party system in which the second party is centrist. Furthermore, we specify that the parties compete in a country that is mixed, i.e., has equal proportions of Catholics and Protestants. It indicates that the predicted probability of a party decreases among Catholics the more conservative a party’s position on the Religious Principles dimension is, while it increases among Protestants.

The right-hand panel in Figure 3 illustrates how the chances of voting for a moderately conservative party (with a scale value of 7.5) change over time among Catholics and Protestants who pray daily and are members of the occupational class of clerks (the stage of secularisation and the denominational composition is the same as in the left-hand panel). The trajectories of the predicted probabilities indicate that the difference between Catholics and Protestants increases throughout the period of observation, instead of decreasing as posited by Hypothesis 3.

The results reported above are surprising in two ways: First, they contrast with the expectation – based on the historical fact that church – state cleavages emerged from conflicts between the Catholic Church and secular (or Protestant) nation-builders in Catholic or mixed countries (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967; Madeley Reference Madeley2003) – that Catholics will be more likely to oppose secular parties. Second, they contrast with the expectation derived from the usual interpretation of secularisation, namely that divisions based on religion (rather than divisions between the secular and the religious) would become weaker. We discuss possible interpretations of these findings in the Discussion section of this paper.

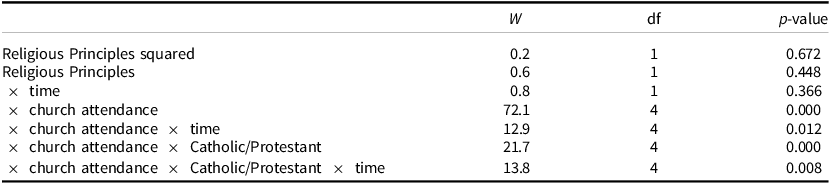

Church attendance and voting among Catholics and Protestants

Hypotheses 4 and 5 concern religious behaviour rather than religious membership (Hypotheses 1 through 3). Since Catholicism and Protestantism differ in the emphasis given to church attendance – with devout Catholics being expected to attend mass at least once a week – a proper analysis of the impact of church attendance needs to take Catholic-Protestant differences in this impact into account. For this reason, the model that we use for the analysis of the impact of church attendance includes not only interactions of church attendance with parties’ positions and time but also three-way interactions of Catholic-Protestant membership, church attendance, and time. Furthermore, as in previous analyses, we consider the level of secularisation, and the composition of the population in terms of Catholics and Protestants as contextual control variables. In a first round of Wald tests, we find that of the contextual control variables, only the countries’ heterogeneity in terms of Catholics and Protestants matters for voting. We therefore repeat the Wald tests with an appropriately simplified model.

The confirmation of either Hypothesis 4 or 5 requires that the second-order interaction effect of parties’ positions with religious attendance and time is statistically significant. The results of the corresponding Wald-tests reported in Table 3 indicate that this is indeed the case. Not only is the interaction of parties’ positions with religious attendance and time statistically significant, but so are the interaction effects that involve the Catholic-Protestant difference. This means that the amount of change, or even the direction of change, may differ among Catholics and Protestants.

Table 3. Wald tests of the hypothesis of declining relevance of church attendance

Note: Tests conducted while controlling for parties’ positions on the Immigration and Economic Left–Right dimensions, respondents’ class positions, and the degree of secularisation of the countries.

Figure 4a clarifies how church attendance is related to the support for parties with different positions on the Religious Principles dimension among Catholics and Protestants. It shows that this relation indeed differs between Catholics and Protestants. In particular, Protestants who attend church weekly have a stronger tendency than Catholics to prefer parties that emphasise religious principles in politics.

Figure 4. Relation between church attendance, parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension, and voting among Catholics and Protestants.

Note: The predicted probabilities are computed from a conditional logit form for a hypothetical two party system, where the position of one party varies, while the position of the other party is fixed at the centre (scale value 5), and both parties have centrist positions on the Immigration and Economic Left–Right dimensions. The voter’s occupational class is fixed to the class of clerks.

The pattern observed in Figure 4a does not seem to change much over time, however. Figure 4b does not suggest any clear pattern of divergence or convergence between those who never attend religious services and those who attend church weekly. That Table 3 shows a statistically significant test result for the three-way and four-way interaction effects that involve positions on the Religious Principles dimension, church attendance, and time apparently may be a consequence of the fact that the differences between the middle categories of church attendance and the outer categories change, a pattern that neither confirms Hypothesis 4 nor Hypothesis 5. Instead, the influence of church attendance persists both among Catholics and Protestants.

Discussion

In this section, we expand on the results and what they imply. We do so with a focus on two aspects. First, we seek to better understand the importance of religious principles specifically, rather than other and related dimensions, for explaining the connection between religion and voting. Second, we elaborate on two somewhat surprising findings that we documented in the results section: that non-Christian religious voters also differ from Christian voters and that the divergence between Catholics and Protestants is growing larger over time.

First, as mentioned before, in addition to the Religious Principles dimension, the CHES also includes information on two other dimensions in which parties may differ and which also may be relevant for religious–secular cleavages: the GAL–TAN dimension and the Social Lifestyle dimension. By conception, the GAL–TAN dimension covers parties’ positions with respect to traditional or post-traditional morals, but it also covers their positions on other non-economic issues, namely those related to nationality and political and social authority. As a result, it probably captures voting differences between religious and secular voters less well as the Religious Principles dimension. The Social Lifestyle dimension could also be relevant for explaining religious–secular differences, perhaps even more so than the Religious Principles dimension, if religious and secular citizens disagree on questions related to gender roles and sexual morals at least as often as on questions explicitly related to the role of religion in politics.

One could therefore wonder if our conclusions hold when we used the GAL–TAN or Social Lifestyle dimension instead of the Religious Principles dimension. While there is not enough space to replicate all analyses with a focus on each of those alternative dimensions, Figure 5 provides insights in the effect of focusing on other dimensions.Footnote 25

Figure 5. A comparison of how Christian, non-Christian, and non-religious voters weigh parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension, Social Lifestyle dimension, and GAL–TAN positions.

Note: The predicted probabilities are computed from a conditional logit form for a hypothetical two party system, where the position of one party is moderately conservative (scale value 7.5), while the position of the other party is fixed at the centre (scale value 5), and both parties have centrist positions on the Immigration and Economic Left–Right dimensions. The voters’ occupational class is fixed to the class of clerks.

Specifically, Figure 5 shows the probability that a Christian, non-Christian, or non-religious voter from the clerks occupational class chooses a party with a scale value 7.5 (moderately conservative) over a centrist party at the midpoint of the period of analysis, i.e., in 2014.Footnote 26 Only with regard to the Religious Principles dimension are the non-religious voters less inclined to vote for a conservative party than the non-Christians. With regard to the Social Lifestyle dimension and the GAL–TAN dimension, non-Christians are even less inclined to vote for a conservative party than the non-religious voters.

Most importantly, however, the percentage points difference between Christian voters and non-religious voters is larger for the Religious Principles scale (

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }} = 16.4$

) than it is either for the Social Lifestyle scale (

${\rm{\Delta }} = 16.4$

) than it is either for the Social Lifestyle scale (

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }} = 13.3$

) or for the GAL–TAN scale (

${\rm{\Delta }} = 13.3$

) or for the GAL–TAN scale (

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }} = 8.3$

). Of the three dimensions, Religious Principles thus most clearly distinguish between the religious and the non-religious.

${\rm{\Delta }} = 8.3$

). Of the three dimensions, Religious Principles thus most clearly distinguish between the religious and the non-religious.

In the Online Appendix, we compare in a similar vein how occupational classes differ in voting regarding parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension. We also examine how both groups defined by religious membership and by occupational class differ in their voting regarding parties’ positions on the Economic Left–Right dimension and the Immigration dimension. These additional analyses clarify that Christian, non-Christian, and non-religious voters differ mainly in how they react to parties’ positions on the Religious Principles dimension and much less so on the Economic Left-Right dimension and the Immigration dimension. Conversely, occupational classes mainly differ in their reactions to positions on the latter two dimensions and hardly differ in their reactions to positions on the Religious Principles dimension.

Second, the results presented in this paper somewhat surprisingly indicate that not only non-religious voters, but also voters who are members of a non-Christian religious group differ from Christian voters. Before we attempt an interpretation, we should first consider whether this result is genuine or spurious. Since most members of non-Christian religions in Europe are immigrants or recent descendants of immigrants,Footnote 27 it could be expected that they are less inclined to support parties with conservative positions on the non-economic axis of electoral competition as these typically take positions less favourable to immigration and national minorities. This cannot explain away our finding because we control for parties’ positions on the immigration dimension. Neither does it make our finding spurious if voters with an immigrant background more often find themselves in disadvantaged socio-economic classes, which may predispose them to vote for left-of-centre parties because our analyses also control for the interaction of parties’ positions on the economic left-right dimension and socio-economic class. For these reasons, we believe that our finding of a divergence between members of a Christian church and of a non-Christian religious group is valid.

Another somewhat unexpected finding of the paper is that Catholics and Protestants diverge in terms of their support for parties with conservative positions on the Religious Principles dimension, with the Protestants – and not the Catholics – increasingly preferring parties with conservative positions. Again, we should consider whether this is a spurious finding. One possibility is that Protestants were more likely to leave their church than Catholics as their faith weakened. However, as can be seen from changes in the distribution of religious groups shown in the Online Appendix, this process of selective exit appears to have ceased before the onset of our period of observation. The proportion of the non-religious increases roughly as much in Catholic countries, such as Ireland, Portugal, and Spain, as it does in Protestant countries like Denmark, Norway, or Sweden. Nevertheless, to account for differences in the extent to which the less convinced have left the Catholic and Protestant churches, we control for the intensity of respondents’ religious beliefs. Doing so, we still find a divergence between Catholics and Protestants. However, as shown in the Online Appendix, the difference between Catholics and Protestants increases with the frequency of prayer. We discuss the implication of these findings in the Conclusion.

Conclusion

The literature on the relation between religion and voting is mainly concerned with two types of cleavages: cleavages between voters with religious and with secular orientations and cleavages along those denominational differences created by the Reformation. In this paper, we formulated and tested hypotheses about the consequences of secularisation for both of these types.

Regarding the first type of cleavage, we find that voting differences between religious Christian and non-religious citizens in Western Europe are not declining, they even increase – in contrast to an idea often implicitly assumed or explicitly claimed in the literature (Best Reference Best2011; Dalton Reference Dalton2002; Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2020). We also find that the voting behaviour of members from non-Christian religious groups is more similar to that of non-religious voters than to that of Christian voters, and that no convergence between Christians and non-Christian occurs. That non-Christian religious voters are closer to the non-religious voters than to Christian voters in their appraisal of parties with conservative positions on the Religious Principles dimension, appears to fit well to the notion of a diverse electoral coalition that supports left-of-centre parties in European democracies – with new-left parties in particular valuing multiculturalism (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008), which can simultaneously appeal to non-religious voters and to voters with an immigrant background (who are well represented in the category of non-Christian religious individuals). This should hold in particular in the absence of competition from parties representing ethnic minorities (Lubbers et al. Reference Lubbers, Otjes and Spierings2024). While it is not novel to find that if non-Christian voters with an immigrant background gravitate to parties of a cultural left, thus forming an electoral alliance with the class of cultural specialists, it is remarkable that non-Christian voters are more similar to the non-religious voters than to the Christian voters on the Religious Principle dimension in particular.Footnote 28

The pattern of divergence cannot simply be understood as a backlash of Christian voters against an increasingly secular society (Achterberg et al. Reference Achterberg, Houtman, Aupers, Koster, Mascini and van der Waal2009). For this to be the case, we should only find a change among the Christian voters and not among the non-Christian voters. Instead, we find that non-Christian and non-religious voters change at least as much as Christian voters, with the latter moving in the opposite direction than the former (see Figure 2). Furthermore, we find that voting patterns among Christian voters differ little between countries with low, medium, or high levels of secularisation, while non-religious and in particular non-Christian voters are the less inclined to vote for parties with conservative positions on the Religious Principles dimension the more secularised a country is. This result fits with Wilkins-Laflamme’s (Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016a; Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016b) finding that highly secularised societies differ from less secularised ones by the stronger liberalism of the religiously unaffiliated. A potential interpretation of our result is that non-religious voters are more encouraged to express their secular orientation in the voting booth the more secular a country is, while the importance of Christian identity (rather than general religious conservatism) increases for Christian parties and their voters, the more secular a country is.

Another religious divide in Western Europe concerns differences between Catholics and Protestants. A common expectation derived from the process of secularisation is that these differences will disappear, either because religion loses its structuring role or because they are superseded by religious–secular cleavages (Achterberg et al. Reference Achterberg, Houtman, Aupers, Koster, Mascini and van der Waal2009; Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff, Roßteutscher, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis-Beck2017a; Jansen et al. Reference Jansen, De Graaf and Need2012; Knutsen Reference Knutsen2004). However, our finding contradicts this expectation. Instead, Catholics and Protestants, who were quite similar in their voting behaviour at the beginning of the time frame of our analysis, diverge from one another, with the Protestants becoming more conservative. Finally, we find that, among Christians, the relation between religious attendance and voting is quite stable: The more often people attend religious services, the more likely they are to vote for parties that emphasise religious principles. But we also find marked differences between Catholics and Protestants in this relation, as it is stronger among the latter than among the former.

While our study is not the first to explicitly include parties’ positions into the analysis of the relation between religion and voting, it differs in its approach from other comparative studies such as the edited volume by Evans and De Graaf (Reference Evans and De Graaf2013), in that we treat parties’ positions as an intrinsic aspect of the voting choice instead of considering them as a contextual factor. We also believe that our approach is better suited to uncover the divergence between Christian and religiously unaffiliated voters.

The results of the paper have several important implications. The first implication is that secularisation does not weaken religious–secular cleavages, but deepens and transforms them. The second implication is that parties that emphasise the role of religion in politics (i.e., Christian democratic and confessional parties) are not successful in expanding their appeal beyond their core constituency and reaching non-Christian religious voters. If forging alliances across the boundaries of religious groups was an option to stem the secularist tide, it has been forgone by these parties or not been available at all. A third implication is that the historical pattern of Catholic-Protestant differences in voting, with Catholics being more likely to vote for Christian parties than Protestants, has been reversed and that this reversed pattern is becoming more marked. A possible explanation is what could be called ‘selective exit’: Protestants are more likely to leave their church if their faith weakens, while Catholics are more likely to stay. As a consequence, the group of Protestants will increasingly be a distillation of more conservative Christians. But there is also another potential explanation for this reverse pattern: Conservative Christians of whatever denomination are increasingly drawn to fundamentalist or evangelical groups who are nominally Protestant.

The results of this paper and their implications lead to a range of intriguing research questions. The first question concerns the contributions of individual re-orientations and of changes in party positions to the changing patterns of voting. Discrete choice models so far treat parties’ positions as externally given and are hitherto unable to disentangle changes caused by voters switching between parties and changes brought about when parties change their positions while voters retain their allegiance to them. Answering this question is not easy: First, one would need to include the dynamics of parties’ positions into the discrete choice model and, secondly, one would need long-term panel data that allows to track how (or whether at all) individuals change their party choices if parties change their positions.

The second set of questions is perhaps a bit more speculative: Is it possible at all for Christian parties to broaden their appeal to socially conservative members of any religion? Is there a potential electorate for parties in Western Europe that could mobilise members of Muslim minorities? There is of course ample evidence that Muslim voters can be mobilised by Muslim parties in Muslim countries, but so far, Muslim parties have not or not yet emerged as a major competitor in West European party systems. Answering this question may require the use of vignettes with hypothetical parties in survey experiments.

The third question that could guide further research concerns the mechanisms behind the divergence between Catholics and Protestants. Investigating the consequences of what has been called ‘selective exit’ earlier in this paper would require panel data, as would an investigation of the political consequences of people shifting from Europe’s mainline denominations (Roman Catholics, Anglican, Calvinist, and Lutheran Protestants) to evangelical ‘free churches’ as well as to charismatic movements within the mainline denominations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100509.

Data availability statement

The Analyses reported in ‘After Secularization? A Comparative Analysis of Religious Cleavages in Western Europe’ were conducted using data from the European Social Survey (ESS) and the Chapel Hill Expert Survey.

Information about the European Social Survey can be obtained from https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/about/, while the ESS datasets used in the analyses for the paper can be downloaded from https://ess.sikt.no/.

Information about the Chapel Hill Expert Survey can be obtained from https://www.chesdata.eu/. The data used in the analyses for the paper are currently available from https://www.chesdata.eu/ches-europe.

R scripts for data preparation and replication of the analyses, as well as auxiliary data files, are available from the Zenodo repository located at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17545227 and from the corresponding author’s personal website.

Acknowledgements