1. Introduction

The interaction between the judiciary and social governance has long stood at the core of both legal theory and judicial practice. In the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law, courts are conceived as independent, passive, and neutral adjudicators, whose decisions are expected to remain insulated from administrative power and political agendas. By contrast, Chinese judicial policy situates courts as institutional actors; judicial decision-making is shaped not solely by legal rules but also by governance mechanisms and administrative rationalities. As China shifts towards a more “collaborative” model of governance, the function of courts has evolved correspondingly. In recent years, the Supreme People’s Court has emphasised that judicial work must “serve the broader goals of economic and social development(服务经济社会发展大局)” and “integrate into grassroots governance (融入基层治理体系).” Courts are in part a government bureaucracy and in part a professional judicial institution; thus, they are no longer confined to being passive end points of adjudication but are increasingly emerging as active participants within a system of multi-actor governance. This raises a question: whether courts are capable of performing such governance tasks. Furthermore, how do courts balance their adjudicative functions with evolving governance demands?

To address this question, it is essential to examine how courts are structured and operate within China’s governance model. Scholars have introduced the concept of the “embedded courts” to offer a crucial perspective on how the judiciary operates within local bureaucratic organisation (Ng and He, Reference Ng and He2017). Embeddedness in Chinese courts is manifested along four key dimensions: administrative, political, social, and economic. Administrative embeddedness manifests as courts operate under a vertically structured hierarchy of internal control. Political embeddedness means that courts function, in part, as stability maintenance agencies, aligning their actions to respond to a range of policy goals set out by the party-state. Social embeddedness highlights that courts, as organisational entities, operate under the influence of both internal and external social networks. Economic embeddedness refers to the fact that, like other government bureaus, courts are grant-funded. Under the embedded courts’ distinctive organisational structure and operational logic, the courts function as a component of local governance. Existing research has revealed the dual effects of this embeddedness. On one hand, judicial participation in social governance has improved the efficiency of dispute resolution and contributed positively to local order and stability (Zuo, Reference Zuo2020, p. 96). On the other hand, some scholars argue that this collaboration between courts and local governments often functions as a formal response to party-state mandates; it may even increase the administrative burden on the judiciary and limit its capacity to pursue independent legal reasoning (Zheng, Reference Zheng2017, p. 34).

Within China’s embedded judicial system, how courts balance adjudicative functions with local governance demands remains a continuing challenge in judicial practice. Some scholars argue that it is difficult for courts to reconcile the demands of local governance with the requirements of impartial adjudication. Some have even proposed that courts may prioritise regional interests, potentially resulting in local protectionism. To explore this question, this article analyses trademark infringement litigation in China, drawing on a dataset of 47,641 first-instance judgments issued between 2014 and 2021, sourced from the China Judgments Online platform.Footnote 1 We evaluate two key outcomes: whether plaintiffs succeed and the compensation amounts, using multiple regression analysis. Trademark litigation offers a suitable setting for this inquiry for three main reasons. First, trademark protection is often regarded by local governments as a means of demonstrating a favourable business environment and promoting economic growth. Intellectual property disputes—especially trademark cases—are closely tied to economic interests and development. Moreover, attitudes towards trademark protection reflect the underlying logic of local governance. Second, trademark litigation frequently involves parties from different regions, offering a valuable perspective for observing how courts adjust between judicial decision and local governance objectives, and then we can test whether the embedded courts lead to local protectionism. Third, the compensation amounts in trademark infringement cases largely depend on judicial discretion rather than the plaintiff’s claim, making the variable of compensation amounts a clear and quantifiable indicator of judicial attitudes related to the preferences of the courts, to answer the question of how the courts satisfy the objectives of local bureaucratic organisation.

The findings reveal a phenomenon: non-local plaintiffs are more likely to win but tend to receive lower compensation amounts. In cases involving corporate defendants, the likelihood of a defence victory is generally higher, but losing defendants face significantly higher damages. This phenomenon suggests a strategic judicial response to local governance objectives. Further heterogeneity analysis reveals that in some provinces, local plaintiffs and holders of well-known trademarks receive lower success and reduced compensation awards. To better capture regional variation in adjudicative practices, we construct a Judicial Behavior Index (JBI) to quantify provincial-level differences in judicial results. Based on the JBI, Henan Province is selected as a case study. The analysis shows that courts act as strategic institutional actors embedded in specific governance environments, strategically adapting to institutional expectations within the bounds of lawful discretion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Embedded courts

The concept of “embeddedness” in the social sciences, originating from economic sociology and new institutional economics, emphasises that no institution can operate in isolation from its surrounding social context (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985, p. 481). In the legal field, scholars have observed that legal regulation often takes place within so-called semi-autonomous social fields, where it is mediated through social relations and networks, illustrating that legal practice is itself a deeply embedded social phenomenon (Moore, Reference Moore1973). It has also been emphasised that law is not confined to state institutions or legal professionals but is “embedded in everyday social practices,” articulated and negotiated through the lived experiences of ordinary people (Ewick and Silbey, Reference Ewick and Silbey1998, p. 21).

In China, scholars have begun integrating the theory of embeddedness with local governance practices, developing the concept of “embedded courts” to describe the complex interplay between local political, social, and economic structures and courts. For instance, researchers have identified four key dimensions—administrative, political, social, and economic—through which local courts’ decision-making in contemporary China is structurally embedded (Ng and He, Reference Ng and He2017, p. 16). Research shows that the localised selection of judges may lead judicial decisions to be influenced by local policy priorities (Chen, Reference Chen2014, p. 60). Political embeddedness may give rise to judicial avoidance, whereby sensitive cases are diverted away from the formal court system to avert political conflict (He, Reference He2012, p. 89). In terms of social embeddedness, judges may be influenced by local social relations, public opinion, and the imperative of maintaining stability, often preferring mediated settlements over adversarial rulings to promote “harmony” (Ng and He, Reference Ng and He2017, p. 22). Economically, when local governments regard particular firms as pillars of the regional economy, courts may adopt lenient approaches or delay enforcement actions to mitigate negative economic impacts (Ng and He, Reference Ng and He2017, p. 24). In addition, not only is the court’s behaviour structurally constrained, but legal professionals such as lawyers also exhibit strategic self-restraint in response to political uncertainties, consciously limiting their own behaviour to avoid risk (Stern and Hassid, Reference Stern and Hassid2012, p. 1236).

Since 2012, China has implemented a series of judicial reforms aimed at reducing unintended consequences of embeddedness—particularly excessive administrative and political interference that may arise during implementation. China launched “de-localisation” judicial reforms in 2014. These reforms removed local government control over court personnel and finances, and transferred judicial administration to the provincial level, with the aim of weakening local administrative influence over the courts. Empirical studies suggest that these reforms significantly reduced local protectionism and facilitated regional economic integration (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lu, Peng and Wang2022, p. 4).

2.2. Trademark infringement litigation and judicial practice in China

Selecting an ideal empirical setting is essential for examining how courts adjudicate under conditions of local embeddedness. Compared with other civil disputes, trademark infringement litigation offers a particularly suitable context for observing judicial behaviour. It is closely tied to economic interests and regional development, frequently involves parties from different localities, and features compensation decisions that depend heavily on judicial discretion, providing a quantifiable indicator of adjudicative tendencies.

At its core, trademark rights are a form of property rights, and the strength of their legal protection is closely intertwined with broader economic conditions and the underlying social fabric (Heath and Christopher, Reference Heath and Christopher2020, p. 1849). Both insufficient and excessive protection can pose challenges to balanced social and economic development. In the embedded courts, this balancing act is particularly complex: how to strike an appropriate balance between enforcing trademark rights and supporting local economic development—too much may hinder business flexibility, while too little may erode the credibility of legal enforcement.

As embedded institutions, local courts in China are deeply integrated into the bureaucratic organisation and play an active role in regional governance. This institutional arrangement has also raised concerns among scholars about potential threats to judicial neutrality. Such concerns are particularly salient in trademark litigation, a domain closely linked to local economic interests and developmental priorities. Recent high-profile cases alleged to exhibit local protectionism have further intensified public scrutiny. Internet catchphrases such as the “Nanshan Sure-Winner (南山必胜客),”Footnote 2 “Longgang Undefeated (龙岗无敌手),”Footnote 3 and “ Haidian Never Loses (海淀不倒翁)”Footnote 4 have become symbolic of perceived judicial favouritism in certain jurisdictions. While these labels may exaggerate the underlying realities, they raise scholarly concerns about whether embedded courts—especially in trademark disputes—demonstrate bias and whether such bias is entangled with local governments’ economic interests. Existing research has primarily focused on two aspects: (1) whether systematic regional disparities exist in judicial decision-making and (2) how litigant characteristics—such as firm size, political connections, and ownership structure—affect case outcomes.

An accumulating body of research suggests that geographic factors may play a significant role in shaping legal outcomes. Courts have been shown to exhibit a tendency to protect local economic interests and favour local firms (Zhang and Ke, Reference Zhang and Ke2002, p. 61). Further empirical studies have demonstrated that plaintiffs who reside in the same jurisdiction as the court are significantly more likely to receive favourable rulings (Long and Wang, Reference Long and Wang2015, p. 54). Based on courtroom observations and interviews, some studies have found that judges tend to exercise caution when determining compensation, out of concern that excessive awards may disrupt local economic stability or market order (Zhan, Reference Zhan2020, p. 196).

An expanding literature also highlights the role of litigant characteristics in influencing judicial decisions. The “scale advantage” of large firms has emerged as a key variable influencing judicial outcomes (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Kang, Kim, Lee and Park2016, p. 86). Moreover, the proportion of politically connected members on a company’s board has been identified as a significant predictor of litigation outcomes, highlighting the potent influence of political capital on judicial decision-making (Xu, Reference Xu2020, p. 2321). However, resource asymmetry is not limited to large firms. A growing strand of research has turned attention to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), noting that due to their limited managerial and legal capacities, some states have introduced institutional accommodations that offer legal flexibility or labour protections, reflecting broader commitments to fairness and social equity (Hanifah et al., Reference Hanifah, Purba and Fajar P.2023, p. 4). Multinational corporations operating in China have also drawn scholarly attention. Evidence suggests that forming joint ventures with state-owned enterprises can enhance foreign firms’ chances of obtaining higher monetary compensation in litigation, indicating that corporate ownership structures may substantially affect judicial outcomes (Chen and Xu, Reference Chen and Xu2023, p. 144).

While some empirical studies have identified possible deviations from judicial decisions, other research suggests that such concerns may be overstated. An empirical analysis of judgments involving Tencent at the Nanshan District People’s Court in Shenzhen, for example, found no conclusive evidence supporting the existence of “capital-captured” local protectionism (Chen, Reference Chen2023, p. 117). Empirical analysis based on data from 2014 to 2016 indicates that courts in Shenzhen did not exhibit significant local protectionism in terms of judgment outcomes, settlement rates, or damages awarded in IP cases (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Crupi and Di Minin2020, p. 614). Further studies have also shown that specialised IP courts did not display a systematic bias towards stronger patent protection in patent litigation (Zhang, Li, and Xu, Reference Zhang, Li and Xu2022, p. 1).

In summary, existing studies have made valuable contributions to understanding judicial decision-making tendencies. He (Reference He2024) conducted a systematic analysis of Chinese courts since Xi Jinping’s judicial reform and proposed a governance model for understanding the operation of the Chinese court system, based on the two dimensions of policy implementation and legitimacy enhancement. This article attempts to further explore its mechanism from an empirical perspective based on real judgments data, focusing on the judicial decision-making of embedded courts, and using civil trademark infringement cases as the empirical context to examine how courts engage in the regulation of social order through adjudication.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data and processing

The data used in this work were obtained from the official online database of the China Judgments Online platform. We focused on first-instance civil trademark infringement judgments issued between 2014 and 2021. Following data retrieval, a series of preprocessing steps were conducted, including deduplication and the exclusion of ineligible judgments, specifically those involving unrelated charges or lacking full texts. Post-cleaning, a total of 47,641 judgments were retained for empirical analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of judgments across provinces.

Figure 1. Distribution of cases by province

3.2. Dependent variables

(1) Win: A binary indicator that takes the value 1 if the plaintiff wins the case, and 0 otherwise. There is no universally accepted standard for defining “win” in civil litigation. Existing scholarship offers several approaches, including partial acceptance of the plaintiff’s claims (Long and Wang, Reference Long and Wang2014, p. 9), the ratio of awarded-to-claimed compensation (Zhang, Reference Zhan2020, p. 622), whether an appeal was filed (Long and Wang, Reference Long and Wang2015, p. 52), and cost-sharing of court fees (Huang, Reference Huang2012, p. 640). However, due to difficulties in reliably linking first-instance judgments to their corresponding appellate rulings in trademark cases, the appeal-based criterion was deemed inapplicable in this study. While China formally adheres to the “loser pays” rule in court fee allocation, in practice, judges often consider other factors—such as the administrative burden of fee reimbursement or parties’ financial capacities. Analysis of the dataset revealed that, in some cases, even when courts clearly found the defendant liable for infringement, court fees were still shared between the plaintiff and the defendant. Given these considerations, this study adopts a conservative and consistent criterion: a plaintiff is considered to have “win” (binary variable = 1) if any of their claims was upheld by the court.

(2) Compensation: This variable measures the amount of compensation awarded to the plaintiff by the court. Although the burden of proof in civil litigation formally lies with the claimant, trademark plaintiffs often face substantial evidentiary challenges. While they may secure evidence of infringement (e.g., notarised purchases), quantifying the volume and value of infringing goods remains difficult. In our dataset, courts relied on statutory damages in 97% of the cases—a figure consistent with previous findings that report similar proportions (e.g., 99.6% in Zhan, Reference Zhan2020, p. 193). Some prior studies use the “support rate of claimed damages” as a dependent variable. However, we opted not to use this measure for several reasons specific to our dataset: (1) certainty of infringement claims. Trademark plaintiffs usually have strong confidence in establishing infringement before filing suit. In our data, 91% of cases involved notarised evidence, demonstrating high evidentiary certainty. (2) Weakened link between claimed damages and litigation costs. In China, court fees are calculated based on the amount claimed. Yet there is often a large discrepancy between claimed and awarded amounts in trademark infringement cases. For example, in case (2019) Yue 03 Min Chu No. 1986, the plaintiff claimed RMB 40 million but was awarded only RMB 3 million, with litigation fees adjusted accordingly (plaintiff prepaid RMB 240,000 and ultimately bore RMB 210,000). (3) Strategic litigation behaviour. Plaintiffs in trademark cases are often well-resourced corporations with the capacity to absorb litigation costs and deploy specialised legal teams. As a result, the infringement determination rate is extremely high, and plaintiffs can often shift litigation costs onto the defendant. In some instances, judges chose not to award monetary compensation even when infringement was established, ordering only cessation of infringing activity. To assess judicial discretion more reliably, we use statutory damages awarded as the primary dependent variable in the main regression models. To test robustness, we also ran supplementary analyses using “support rate of claimed damages” as an alternative outcome variable. The results showed a negligible R2 value (0.003), indicating poor explanatory power. Taken together, these findings support the use of statutory compensation as a more valid and consistent measure of judicial decisions.

3.3. Independent variables

Referring to previous studies, we empirically test for judicial adjudication by focusing on two key dimensions: “local dimension,” which reflects mechanisms of territorial favouritism, and “capital dimension,” which captures potential pathways of economic influence on judicial outcomes. Corresponding independent variables are constructed to represent and evaluate these two dimensions within the regression framework.

3.3.1. Local dimension

This dimension emphasises the role of geographic proximity in judicial outcomes. We construct three mutually exclusive dummy variables to capture the relative geographic positions of the litigating parties:

Parties: N v.s. L: Equals 1 if a non-local plaintiff sues a local defendant.

Parties: L v.s. N: Equals 1 if a local plaintiff sues a non-local defendant.

Parties: L v.s. L: Equals 1 if both the plaintiff and the defendant are local.

In subsequent empirical models, “Parties: L v.s. L” is used as the baseline category (reference group) for comparison. These variables are designed to identify asymmetric judicial responses based on the geographic identity of litigants and to test for location-based biases in court decisions.

3.3.2. Capital dimension

This dimension assesses whether firms with stronger market positions or organisational capacity are more likely to receive favourable rulings. We construct two dummy variables:

Well-KnownTM: Equals 1 if the infringed trademark is officially recognised as well-known, indicating elevated brand value and reputational capital.

Corporate defendant: Equals 1 if the defendant is organised as a corporation (as opposed to sole proprietorships or individual business entities). Corporations typically possess stronger legal capacity, more robust institutional support, and greater litigation resources, which may influence both their risk tolerance and adjudication outcomes.

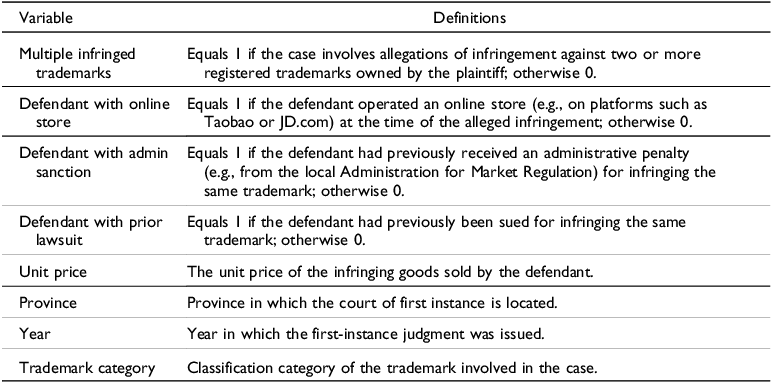

3.3.3. Control variables

The models also include a set of control variables capturing case-level, court-level, and party-level characteristics. Table 1 provides detailed definitions for all variables used in the analysis.

Table 1. Control variable definitions

4. Empirical analysis

4.1. Baseline regression results

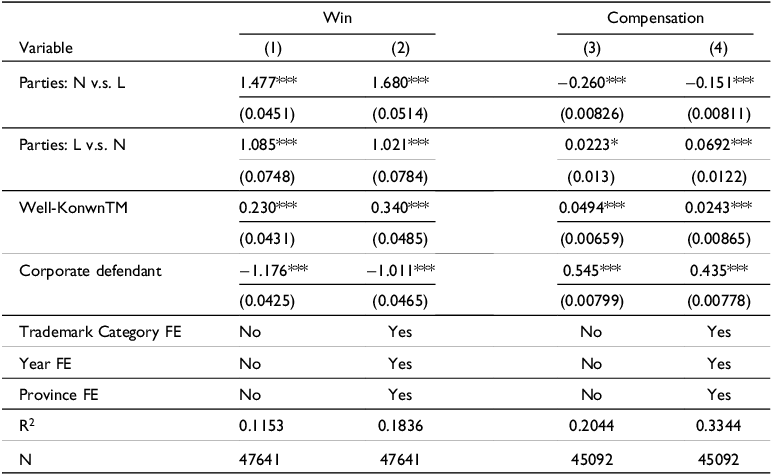

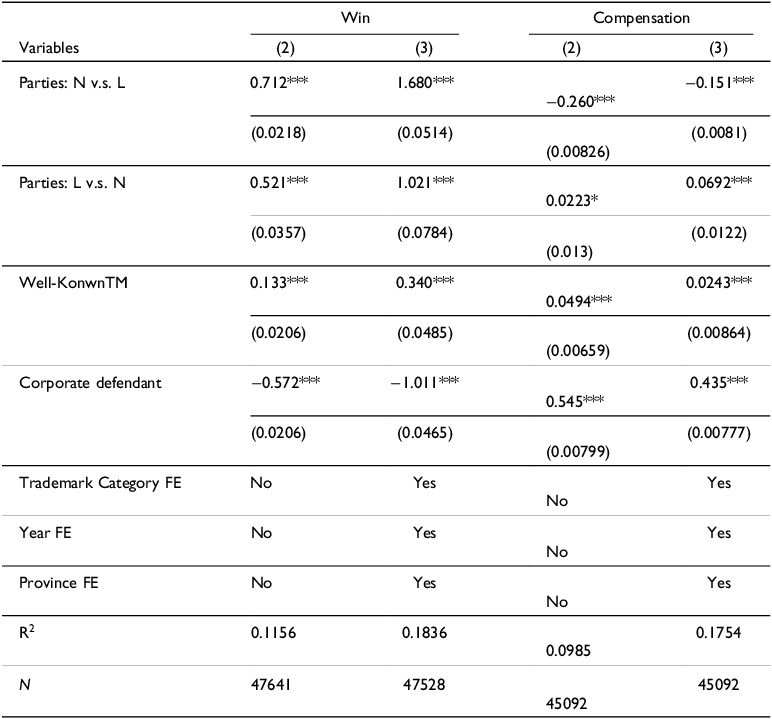

Table 2 reports the baseline empirical results for trademark infringement cases. Columns (1) and (2) use logistic regression to estimate the probability of plaintiff success (dependent variable: Win), while Columns (3) and (4) use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to analyse the log-transformed compensation amount (dependent variable: compensation). All columns add the control variables, while Columns (2) and (4) further add province fixed effects, year fixed effects, and trademark type fixed effects to account for unobserved heterogeneity.

Table 2. Baseline regression results

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. The same notation applies throughout the paper.

The results in Column (2) show that, regardless of whether the plaintiff is a local or non-local company, courts are more likely to rule in favour of the plaintiff. However, non-local plaintiffs have a higher probability of success compared to their local counterparts. When the defendant is a corporation, the plaintiff’s odds of winning decrease by approximately 63.6% with a one-unit increase in the independent variable. These findings are statistically significant at the 1% level. Column (4) presents the results for awarded damages. When the litigation involves cross-provincial parties, local firms tend to obtain more favourable compensation outcomes. In terms of defendant characteristics, the results show that corporate defendants face stiffer penalties. Specifically, ceteris paribus, compensation awards are approximately 54.5% higher for corporate defendants compared to their non-corporate counterparts.

4.2. Endogeneity analysis

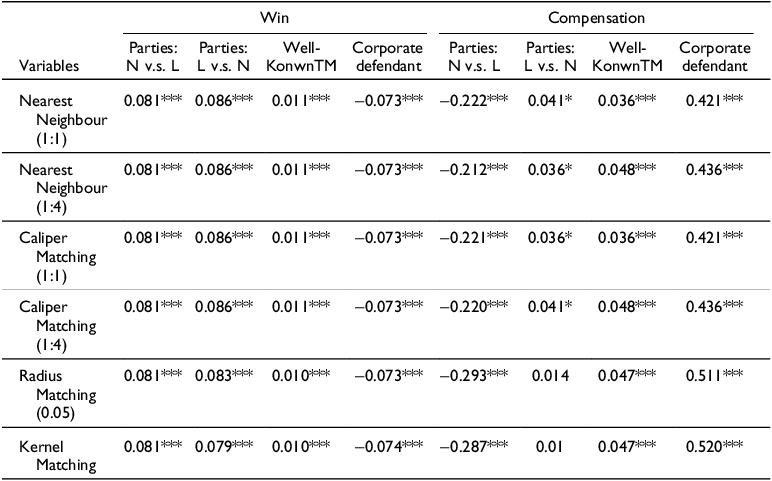

To address potential sample selection bias, we employ propensity score matching (PSM) as a robustness check. PSM mitigates selection effects by matching treated and control groups based on observable characteristics, thereby improving the comparability of the groups. Propensity scores are estimated using a logit model, with all control variables specified as covariates. The matching procedure is conducted within a common support region, ensuring that observations with similar propensity scores are retained. To enhance robustness, we implement multiple algorithms, including 1:1 and 1:4 nearest-neighbour matching, as well as radius and kernel matching. Across all specifications, the PSM estimates are consistent with the baseline findings (see Appendix Table A).

4.3. Robustness checks

To assess the robustness of the main findings, we re-estimate the models using alternative specifications. Specifically, we replace the logit model with a probit model for the binary outcome of plaintiff success, and substitute the OLS model with a Tobit model for the continuous outcome of compensation. Appendix Table B confirms the robustness of the preceding results.

Overall, the nationwide empirical results reveal a strategy behind the ideal of local bureaucratic organisation. On one hand, courts appear more likely to rule in favour of non-local plaintiffs, suggesting a degree of procedural neutrality or institutional respect for the claims of external litigants. On the other hand, the compensation in such cases is significantly lower, indicating a restrained approach to monetary awards. This combination of “high win—low compensation” may reflect a form of judicial strategy—a strategic balancing act employed by courts when adjudicating cases involving out-of-region parties. Conversely, cases involving corporate defendants exhibit a higher probability of defendant success. However, when infringement is established, the damages awarded against corporations are substantially higher, implying that courts adopt more punitive remedies once liability is determined. This dual tendency suggests a potential strategic allocation logic in judicial reasoning.

4.4. Heterogeneity analysis

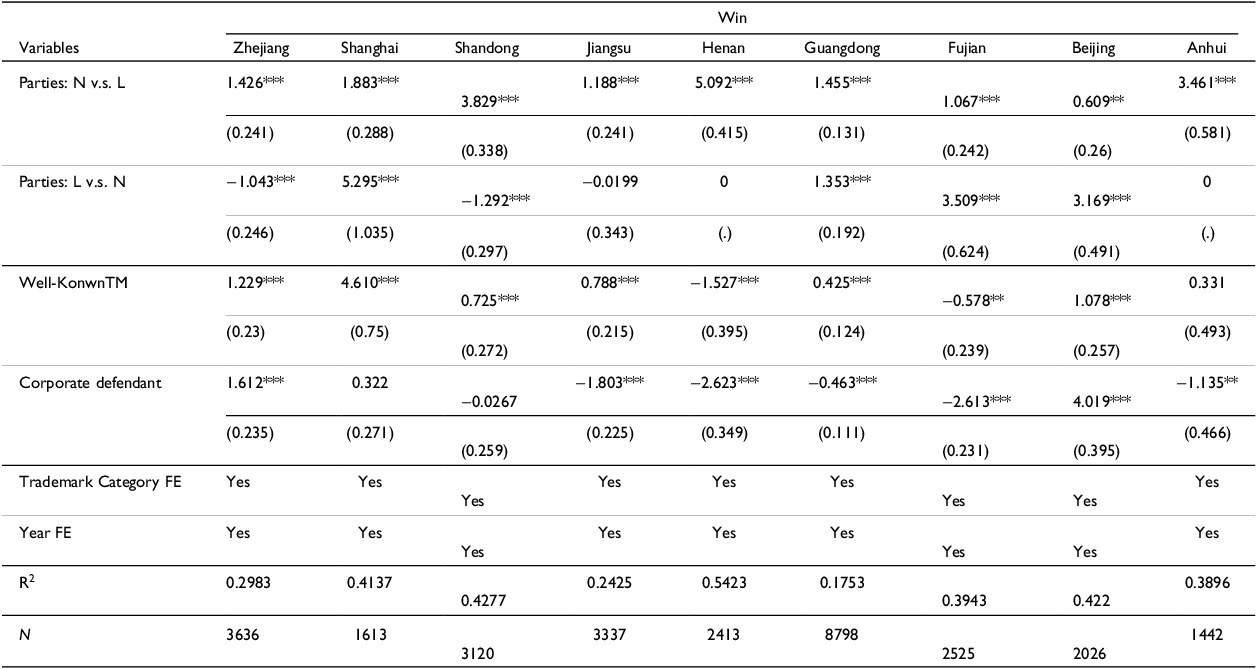

Regional policy priorities and industrial structures may influence judicial behaviour in different ways. To further assess the robustness and conditionality of our main findings, we conduct subgroup analysis. This section reports the results of province-specific heterogeneity analyses. While the baseline regressions provide estimates of average nationwide effects, this section disaggregates the analysis by province. Specifically, we restrict the sample to provinces with over 1,000 observations and re-estimate the empirical models. Appendix Tables C and D report the regression results for “win” and “compensation,” respectively. The results reveal substantial geographic variation in judicial behaviour. For instance, lawsuits filed by non-local corporate plaintiffs against local companies show a strong positive effect in Henan Province (β = 5.092) and Anhui Province (β = 3.461), suggesting pronounced support for external plaintiffs. In contrast, Zhejiang (β = −1.043) and Shandong (β = −1.292) exhibit significant negative coefficients in cases where local plaintiffs sue non-local defendants, a pattern that diverges from the national average trend. Similarly, well-known trademarks show unexpected negative effects in Henan (β = −1.527) and Fujian (β = −0.578), contradicting the generally positive relationship observed at the national level. Moreover, courts in Zhejiang (β = 1.612) and Beijing (β = 4.019) show positive and significant effects for the variable capturing corporate defendant status, while courts in Henan (β = −2.623) and Fujian (β = −2.613) show the opposite. These findings suggest that courts in different provinces may adopt differentiated adjudicative standards when dealing with corporate defendants, pointing to a nuanced and context-specific form of judicial heterogeneity.

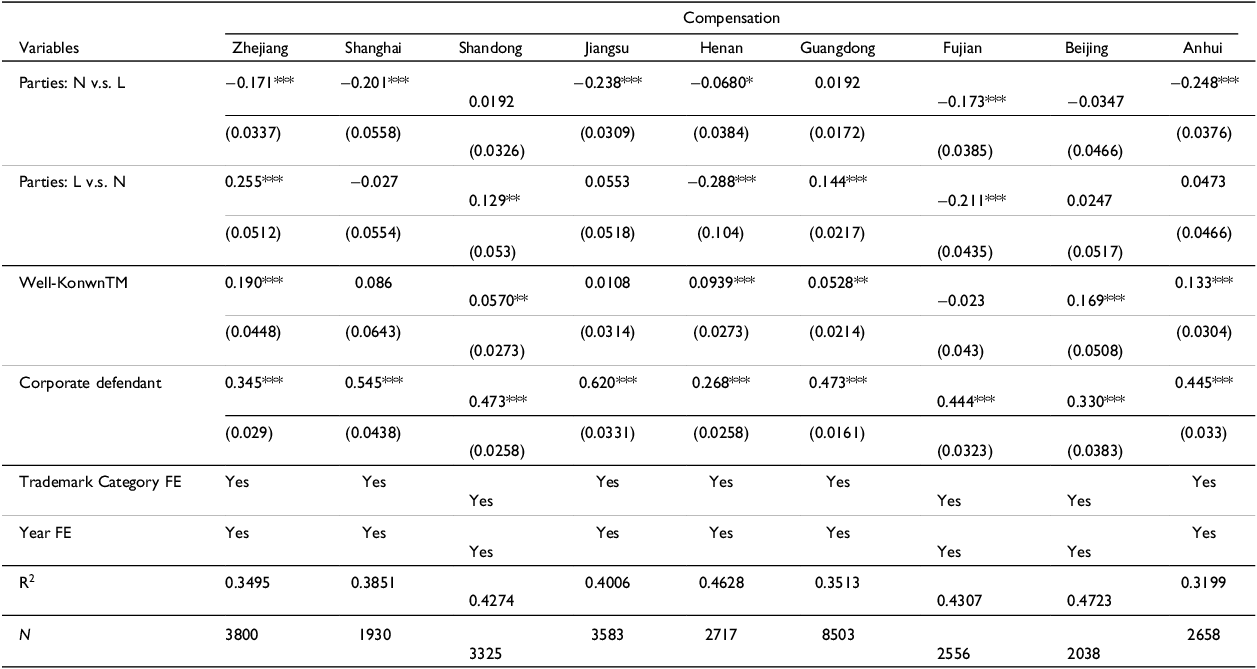

In terms of “compensation,” lawsuits filed by local plaintiffs against non-local defendants in Henan (β = −0.288) and Fujian (β = −0.211) exhibit negative effects in contrast to the generally positive coefficients observed at the national level and in most other provinces.

5. Findings

5.1. Finding 1: High plaintiff success, low compensation for non-local parties

The empirical results provide support for this finding: Non-local plaintiffs are more likely to win but receive lower compensation. The results of the baseline regression, the robustness tests, and the endogeneity analysis indicate that this finding is robust. This finding shows a potentially dual-track logic in judicial adjudication: courts may apply more neutral or even favourable standards when determining liability in favour of non-local plaintiffs but simultaneously adopt a more conservative stance in the determination of damages, possibly as a way to balance judicial function with local economic demands. This logic challenges the assumption of local protectionism and instead points to a more nuanced adjudicative phenomenon, in which geographic factors may influence judicial decisions, but rather than outright protectionism or favouritism, they reflect the embedded courts’ strategic considerations for local development.

5.2. Finding 2: Corporate defendants win more but pay more when they lose

The empirical results show that corporate defendants are more likely to prevail in trademark infringement cases. However, when infringement is established, these defendants tend to face significantly higher compensation amounts compared to non-corporate defendants. This finding is consistently supported by baseline regression results and robustness checks. This pattern suggests that courts may be more cautious in assigning liability to corporate entities—potentially due to their greater legal resources or perceived legitimacy. On the other hand, once liability is confirmed, courts appear to adopt a more stringent approach towards corporate defendants, possibly reflecting heightened expectations of legal compliance or social responsibility from such entities.

5.3. Finding 3: Less favourable treatment of local plaintiffs and well-known trademarks

The regional heterogeneity analysis revealed that some courts exhibited what may be described as a “negative preference” towards local plaintiffs and well-known trademarks—not only failing to offer preferential treatment, but at times adopting more conservative adjudicative stances. In this context, local status or trademark fame may trigger heightened judicial scrutiny, resulting in more restrained remedies or stricter evidentiary thresholds. Based on this finding, we distinguish between well-known trademarks: local well-known trademarks and non-local well-known trademarks. Empirical analysis found that the “negative bias” towards well-known trademarks can be further explained along two dimensions: First, a local factor: local well-known trademarks are subject to stricter judicial scrutiny, which lowers their success rate not only compared to the national average but also relative to non-local plaintiffs. Second, the attribute of a well-known trademark, which reduces the success rate of non-local well-known trademarks relative to national performance. The empirical data are consistent with earlier findings. At the national level, plaintiffs with local well-known trademarks have a slightly higher success rate (96%) than those with non-local well-known trademarks (95%), and their average compensation (67,500 RMB) is more than double that of non-local ones (28,400 RMB). By contrast, in the two provinces where a “negative bias” is observed (Henan and Fujian), the pattern is reversed: plaintiffs with local well-known trademarks have a lower success rate (90%) than non-local ones (94%), while their average compensation (47,600 RMB) remains higher than that of non-local plaintiffs (19,200 RMB).

This finding suggests that judicial behaviour is not uniformly influenced by geographic proximity or brand reputation. Instead, some courts may consciously avoid the appearance of local favouritism or bias, particularly in cases involving well-known marks or local parties. This challenges the assumption that courts naturally lean towards protecting local plantiffs or well-known brands and instead points to an adjudicative logic shaped by both judicial functions and local governance imperatives.

Furthermore, based on the earlier findings, we conducted semi-structured interviews with judges from the L Primary People’s Court of J City, the D Primary People’s Court of D City, and the S High People’s Court of S Province. The interviewed judges emphasised that courts are not merely adjudicatory bodies but also active participants in social governance. This participation is not the product of external pressure or institutional arrangements, but rather stems from the objectives of safeguarding fairness and justice, as well as promoting social harmony, with courts actively undertaking social responsibility through the approach of “promoting governance through adjudication.” In adjudication, judges focus not only on the facts of the case and the applicable law but also take into account the actual circumstances of the parties, so as to strike a balance of interests and achieve the unity of legal and social effects. Specifically:

First, protecting the economic vitality of SMEs. Under the commercialised intellectual property rights enforcement model, a large number of serial lawsuits may deal a fatal blow to small companies lacking IP awareness. When judging such cases, judges may appropriately reduce compensation in order to avoid excessive awards that could undermine the survival and development of local enterprises.

Second, strengthening the responsibility of corporate defendants. Corporate defendants generally possess stronger compliance mechanisms and greater litigation resources, which contribute to their relatively high overall success rate. However, once infringement is established, courts often impose higher compensations to reflect their greater social responsibility and a heightened duty of care, thereby encouraging them to strengthen risk management and internal compliance systems.

Third, exercising caution towards plaintiffs in a position of advantage. In trademark litigation, plaintiffs typically hold the initiative, and a number of cases can be characterised as commercialised IP litigation. For local plaintiffs or well-known trademark holders who already enjoy structural advantages, judges tend to adopt a more cautious approach so as to prevent reinforcing existing power imbalances, thereby safeguarding judicial impartiality and neutrality.

In sum, these findings suggest that courts in the adjudicatory process are not merely applying the law but also acting as active participants in social governance, with their adjudicative orientation often directed towards reconciling legal results with social consequences.

6. Further discussion

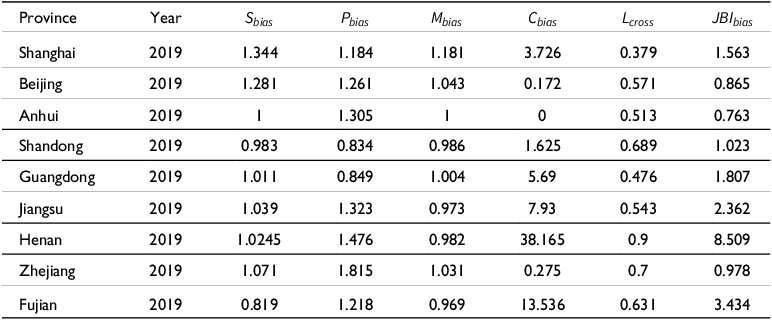

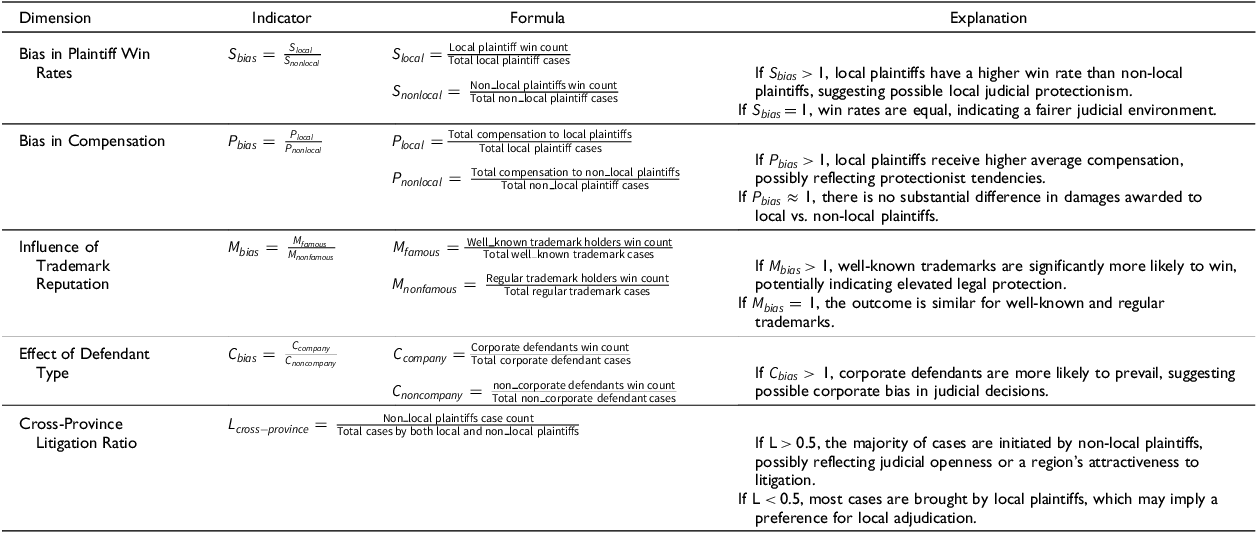

6.1. Judicial Behavior Index (JBI): Measuring regional judicial disparities

To more clearly illustrate regional disparities in judicial decision-making, we construct a JBI based on standardised measures of key adjudicative dimensions (see Appendix Table E). Using 2019 as the reference year, we develop the JBI from national datasets of first-instance trademark infringement judgments. The JBI incorporates multiple dimensions, including plaintiff win rates, compensation amounts, and variables related to party identity and trademark attributes. This composite index is designed to capture variations in judicial behaviour across regions. Importantly, the JBI is a descriptive and neutral indicator—it does not entail normative evaluation or value judgment. Rather, it serves as a tool to assess the relative salience or marginality of judicial behaviour in different provincial contexts, offering a complementary perspective on the institutional diversity of China’s legal landscape.

Furthermore, we construct a composite measure,

![]() $JB{I_{bias}}$

, by aggregating the earlier dimensions using an equal-weighted summation method. Each standardised variable contributes equally to the overall index, allowing us to integrate multiple adjudicative dimensions into a single, unified indicator of regional judicial behaviour.

$JB{I_{bias}}$

, by aggregating the earlier dimensions using an equal-weighted summation method. Each standardised variable contributes equally to the overall index, allowing us to integrate multiple adjudicative dimensions into a single, unified indicator of regional judicial behaviour.

Table 3 presents the

![]() $JB{I_{bias}}$

values for selected representative provinces. The results indicate that Henan Province exhibits a notably higher

$JB{I_{bias}}$

values for selected representative provinces. The results indicate that Henan Province exhibits a notably higher

![]() $JB{I_{bias}}$

value compared to other regions, suggesting a pronounced divergence in judicial behaviour along key adjudicative dimensions. This finding aligns with earlier regression results, which revealed Henan’s distinctive pattern of negative preference, further supporting the presence of region-specific judicial tendencies.

$JB{I_{bias}}$

value compared to other regions, suggesting a pronounced divergence in judicial behaviour along key adjudicative dimensions. This finding aligns with earlier regression results, which revealed Henan’s distinctive pattern of negative preference, further supporting the presence of region-specific judicial tendencies.

Table 3. JBI in provinces

6.2. Case study of Henan: Understanding regional judicial strategy

To further interpret the empirical findings, this study conducts an in-depth case analysis of Henan Province. On the one hand, Henan’s judicial pattern broadly aligns with the national trends observed in the heterogeneity analysis, making it a representative case. On the other hand, through heterogeneity analysis, we find that courts in Henan exhibit a marked “negative preference” in cases involving well-known trademarks and local plaintiffs, and the JBI values also suggest that Henan displays a different performance from other provinces. Focusing on Henan not only contributes to a better understanding of regionally differentiated judicial behaviour but also provides theoretical insights into how local courts act and reason strategically in the field of intellectual property protection.

6.2.1. Policy implementation: Henan’s trademark strong province strategy

Since 2013, Henan Province has formally elevated its “trademark strategy” to the level of a provincial development policy, issuing a series of official documents such as the Opinions on Implementing the National IP Strategy and Promoting Trademark Strategy.Footnote 5 This agenda emphasises not only the quantity and visibility of registered trademarks but also their asset-oriented utilisation as a driver of local economic development. Within this policy framework, trademarks are understood not merely as an important part of intellectual property but as strategic assets that mediate industrial capital formation and regional competitiveness.

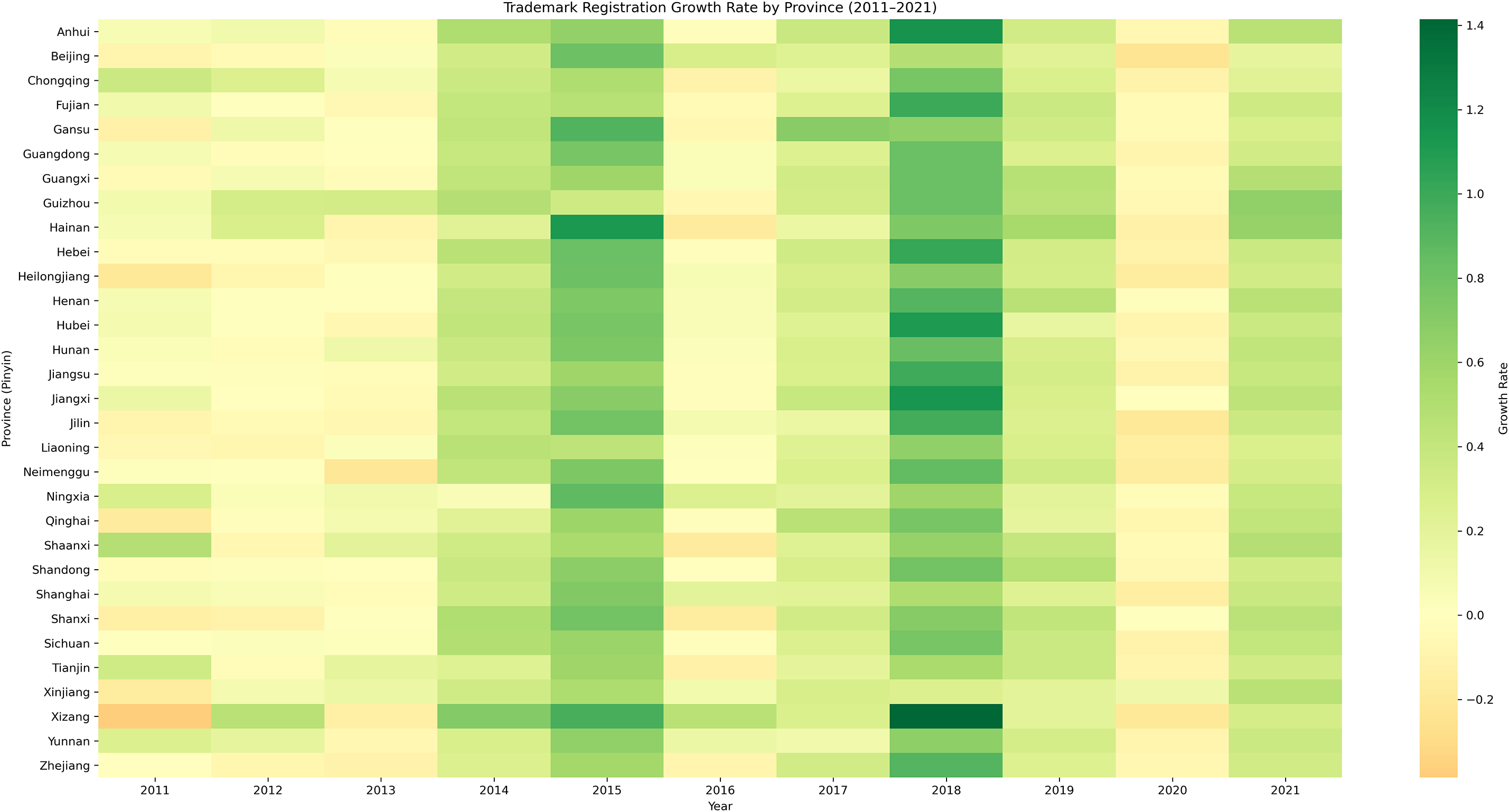

We compiled statistics on the annual number of trademark registrations in all provinces of China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) from 2010 to 2021 and generated a heatmap based on the year-on-year growth rate (see Figure 2). The number of trademark registrations in various provinces generally shows a trend of continuous growth. Focusing on Henan, we found that since the official implementation of the “Trademark Strong Province Strategy” in 2013, trademark registration growth has accelerated significantly. After 2013, Henan’s average annual growth rate reached 41.1%, ranking fourth among 31 provinces nationwide, indicating the obvious promotional effect of the strategy on the activity of trademark registration. More notably, during the 2019–2020 time window, Henan’s trademark registration growth rate reached 22.4%, ranking first nationwide. This result shows that before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the pace of trademark development in Henan had already reached a leading position in the country, thus fully demonstrating the practical effectiveness of the “Trademark Strong Province” strategy in promoting regional trademark development.

Figure 2. Provincial Trademark Registration Growth Heatmap (2010–2021). Data source: Trademark Office of the China National Intellectual Property Administration.

6.2.2. Judicial responsiveness: Court reactions to trademark governance demands

Against this institutional backdrop, judicial practice may demonstrate heightened sensitivity to governance priorities and an active institutional response. In Henan, judicial practices in trademark infringement cases clearly reflect increased attention to the organisational form of market actors, and Henan courts exhibit a distinct strategic adjudication model in cases involving corporate defendants. When a corporate defendant is involved, the plaintiff is less likely to win the case, but once infringement liability is determined, the amount of compensation imposed on the corporate defendant is far higher than that of a non-corporate defendant. This phenomenon suggests that while courts focus on corporate entities, they also operate under a balancing act aimed at mitigating legal risks. By raising the threshold for success, courts seek to mitigate risk and stabilise the operations of corporate defendants. Furthermore, if infringement is found, higher compensation awards serve as a powerful deterrent to corporate infringement.

6.2.3. Market reactions and strategic adjudication: Courts improve the local business environment

If local policy influences judicial behaviour, then market actors are likely to respond strategically; in other words, firms and rights holders may make conscious litigation choices. Data from 2017 to 2019 show that Henan Province handled 3,886 trademark infringement cases, involving a total disputed amount of approximately 32.8 million RMB, reflecting a steady intensification of intellectual property enforcement.Footnote 6 Under the province’s “trademark-strengthening” strategy, Henan has not only reinforced coordination between administrative enforcement and judicial adjudication but also implemented multiple measures to improve the local business environment, thereby increasing its attractiveness to innovation-oriented enterprises. A striking outcome is that Henan has become a major litigation destination for non-local firms seeking trademark protection. In 2019, over 90% of trademark infringement cases in Henan involved non-local plaintiffs, primarily from Beijing, Shanghai, and Zhejiang—regions with high concentrations of intellectual property assets.

This shift in the structure of litigation sources places greater demands on local courts. The influx of non-local rights holders has significantly increased the complexity of cases, particularly when trademark disputes involve inter-regional markets or divergent legal expectations. In such contexts, courts must not only ensure the quality and consistency of their rulings but also navigate the delicate balance between policy responsiveness and judicial neutrality. In response to this dual pressure, courts have gradually developed a strategic adjudication logic with an implicit regulatory function—what can be described as a “high threshold + high compensation” model. By raising the bar for plaintiff success, courts deter frivolous litigation; yet when infringement is verified, they impose stringent monetary penalties to reinforce institutional deterrence and signal a pro-market orientation. This adjudicative strategy reflects a form of institutional adaptation, one that simultaneously responds to local government expectations for an improved business environment and stronger property rights protection, while also preserving judicial legitimacy and neutrality in the face of increasing litigation from external market actors.

In conclusion, Henan’s “Trademark Strong Province” strategy demonstrates distinctive characteristics: the implementation of the policy mobilised the joint participation and interaction of multiple forces, while judicial response and market feedback have together produced a unique pattern of strategic adjudication. The interaction and linkage among policy, judiciary, and market have strongly promoted the thorough implementation of Henan’s trademark brand strategy.

7. Conclusion

Whether embedded courts are capable of performing governance functions, and how they balance their adjudicative functions with evolving governance demands, has long been a central concern in socio-legal scholarship. In the Chinese context, where courts function both as administrative units and as professional judicial institutions, this article examines how Chinese courts, as embedded institutions within local bureaucratic systems, balance the dual imperatives of legal adjudication and governance responsiveness. Through an empirical analysis of 47,641 trademark infringement judgments, we find that courts in China operate not merely as neutral adjudicators but as strategic institutional actors embedded within specific governance environments. Their decisions reflect an adaptive logic—one that aligns with institutional expectations while remaining within the bounds of lawful discretion.

Looking ahead, as China’s collaborative governance model continues to evolve, courts will likely face sustained pressure to align their judicial functions with administrative and developmental objectives. While judgments alone cannot fully analyse the underlying reasoning processes of judges, future research could build on this foundation to examine the background causes and institutional logics that underlie these practices, for example, by combining large-scale judgment analysis with case studies and interviews. A deeper understanding of how courts negotiate this dual role will be crucial to evaluating the future trajectory of rule-of-law development within China’s governance framework.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 72371145 and T2293773) and the Special Funds for Taishan Scholars Project of Shandong Province, China (tsqn202211004).

Appendix Empirical Model

We estimate a logistic regression model for win, a binary outcome indicating whether the plaintiff prevailed. Logistic regression is well suited for modelling binary dependent variables and allows us to assess the likelihood of plaintiff success as a function of various explanatory factors. The model is specified as follows:

$${Prob\left( {{Y_{ij}} = 1{\rm{|}}{X_{ij}}} \right) = \;{{{\it exp} \left( {\alpha + {\beta _1}{X_{ij}} + {\beta _2}{S_{ij}}} \right)} \over {1 + {\it exp} \left( {\alpha + {\beta _1}{X_{ij}} + {\beta _2}{S_{ij}}} \right)}}}$$

$${Prob\left( {{Y_{ij}} = 1{\rm{|}}{X_{ij}}} \right) = \;{{{\it exp} \left( {\alpha + {\beta _1}{X_{ij}} + {\beta _2}{S_{ij}}} \right)} \over {1 + {\it exp} \left( {\alpha + {\beta _1}{X_{ij}} + {\beta _2}{S_{ij}}} \right)}}}$$

In the model,

![]() ${Y_{ij}} = 1$

indicates that the plaintiff prevailed in case

${Y_{ij}} = 1$

indicates that the plaintiff prevailed in case

![]() $i$

, where

$i$

, where

![]() $\;j$

denotes the region in which the adjudicating court is located.

$\;j$

denotes the region in which the adjudicating court is located.

![]() ${X_{ij}}\;$

represents the key variables used to measure judicial behaviour, including all variables from both the local and capital dimensions, while

${X_{ij}}\;$

represents the key variables used to measure judicial behaviour, including all variables from both the local and capital dimensions, while

![]() ${S_{ij}}$

includes control variables that may affect the probability that the plaintiff prevails.

${S_{ij}}$

includes control variables that may affect the probability that the plaintiff prevails.

For the continuous variable, compensation, we employ an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model.

In this model,

![]() ${Y_{ij}}\;$

denotes the compensation in case

${Y_{ij}}\;$

denotes the compensation in case

![]() $i$

, where

$i$

, where

![]() $j$

refers to the region in which the adjudicating court is located.

$j$

refers to the region in which the adjudicating court is located.

![]() ${X_{ij}}\;$

captures the key indicators of judicial behaviour, including all variables from both the local and capital dimensions, while

${X_{ij}}\;$

captures the key indicators of judicial behaviour, including all variables from both the local and capital dimensions, while

![]() $\;{S_{ij}}$

includes control variables that may influence the amount of compensation.

$\;{S_{ij}}$

includes control variables that may influence the amount of compensation.

![]() ${{\varepsilon _{ij}}}$

represents the random error term.

${{\varepsilon _{ij}}}$

represents the random error term.

Table A. PSM estimation results under different matching methods

Table B. Robustness checks (Probit and Tobit)

Table C. Heterogeneity analysis by province: regression results for win (plaintiff success)

Table D. Heterogeneity analysis by province: regression results for compensation

Table E. Judicial Behavior Index (JBI)