1. Introduction

Particle-laden jets often arise in nature in the form of volcanic plumes (Kieffer & Sturtevant Reference Kieffer and Sturtevant1984; Viggiano et al. Reference Viggiano, Gish, Solovitz and Cal2024) and hydrothermal eruptions (McKibbin, Smith & Fullard Reference McKibbin, Smith and Fullard2009). Likewise, particle-laden jet flows can be found in numerous advanced engineering applications such as cold spray manufacturing (Alkhimov et al. Reference Alkhimov, Papyrin, Kosarev, Nesterovich and Shushpanov1994; Herman & Sampath Reference Herman and Sampath1996), metallurgy (Wei et al. Reference Wei, Zhu, Yang, Hu, Yang and Chen2020), nanothermite combustion for propulsion applications (Apperson et al. Reference Apperson, Bezmelnitsyn, Thiruvengadathan, Gangopadhyay, Gangopadhyay, Balas, Anderson and Nicolich2009), targeted drug delivery (Arora et al. Reference Arora, Hakim, Baxter, Rathnasingham, Srinivasan, Fletcher and Mitragotri2007; Kleinstreuer, Zhang & Donohue Reference Kleinstreuer, Zhang and Donohue2008), transmission of diseases through sneezing and coughing (Mittal, Ni & Seo Reference Mittal, Ni and Seo2020; Bourouiba Reference Bourouiba2021) and particle entrainment in jets used in the final approach of lander modules to the surface of extraterrestrial bodies (Jaffe Reference Jaffe1971; Sengupta et al. Reference Sengupta, Kulleck, Sell, Van Norman, Mehta and Pokora2009). Regardless of the nature of these jets, the particle distribution in such flows has been a source of long-standing questions that have motivated numerous research campaigns in this field. To fully grasp particle dispersion in a jet, three main aspects of particle–fluid interaction require understanding. These are discussed in the following subsections.

1.1. Particle clustering

Generally, in turbulent flows, particles are known to be ejected from vortices based on their inertia, and cluster where vorticity is low (Squires & Eaton Reference Squires and Eaton1991) or in locations where their net acceleration is zero (Goto & Vassilicos Reference Goto and Vassilicos2008). The mechanism of particle clustering in low vorticity (high strain-rate) regions due to the centrifugal force exerted on the particles by coherent turbulent structures is called preferential concentration (PC), and it is the most widely accepted explanation for turbulence-induced particle clustering. Furthermore, it has been reported that, in jet flows, particles preferentially gather in the regions with a local streamwise velocity higher than the mean velocity (Li et al. Reference Li, Fan, Luo and Cen2011). Moreover, in general, compressibility and shear play a significant role in the particle dynamics, where, apart from PC (which is still blamed for clustering Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Liu, Ma and Xiao2016), particle clustering intensifies with the increase in compressibility (Pérez-Munuzuri Reference Pérez-Munuzuri2015). This is particularly important for high-speed jet flows which involve significant compressibility and shear.

Regardless of the particle clustering mechanism, clustering is driven by turbulent eddies and the particles’ response to these eddies based on their inertia. In homogeneous isotropic turbulence (HIT), tracer particles with virtually no inertia can closely follow the coherent turbulent structures (Bec et al. Reference Bec, Biferale, Cencini, Lanotte and Toschi2006). Therefore, tracer-like particles are often used in experimental techniques such as particle image velocimetry for measuring flow parameters (Adrian Reference Adrian1984). On the contrary, heavy particles tend to be ballistic, and thus their motion is weakly influenced by local eddies (Balachandar & Eaton Reference Balachandar and Eaton2010). A dimensionless parameter called the Stokes number (

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

) is typically used to characterise the inertia-based correlation between the particles and turbulence, as discussed later in this section.

${\textit{St}}$

) is typically used to characterise the inertia-based correlation between the particles and turbulence, as discussed later in this section.

1.2. Particle transport

In the context of jets, apart from clustering, particle inertia also determines particle trajectories as the jet develops (Casciola et al. Reference Casciola, Gualtieri, Picano, Sardina and Troiani2010); whether particles travel within the jet or are dispersed away from the jet centreline. Predicting particle trajectories is critical for numerous applications. For example, in cold spray advanced manufacturing techniques, the goal is to keep the particle inside the high-speed jet, as particle dispersion drops coating efficiency (Meyer, Yin & Lupoi Reference Meyer, Yin and Lupoi2017). Favourably, the presence of particles narrows the spreading of the jet and enhances the centreline velocity as particle motion is governed by the kinetic energy of the gas (Hetsroni & Sokolov Reference Hetsroni and Sokolov1971). This effect is desirable for cold sprays. On the other hand, in combustion applications, efficient combustion relies on higher radial dispersion of the fuel droplets (Basu et al. Reference Basu, Agarwal, Mukhopadhyay and Patel2018), considering that these droplets can coalesce, which can greatly limit their dispersion by increasing the droplet size (Gopireddy, Humza & Gutheil Reference Gopireddy, Humza and Gutheil2012). Hence, to manage the radial dispersion of particles based on the application, there is a pressing need to delineate the mechanisms that lead to this dispersion.

For estimating the dispersion of particles inside a jet, the Stokes number (

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

) (Crowe, Gore & Troutt Reference Crowe, Gore and Troutt1985) has been extensively used, which is the ratio of particle momentum response time (

${\textit{St}}$

) (Crowe, Gore & Troutt Reference Crowe, Gore and Troutt1985) has been extensively used, which is the ratio of particle momentum response time (

![]() $\tau _{\!p}$

) to a characteristic turbulent time scale (

$\tau _{\!p}$

) to a characteristic turbulent time scale (

![]() $\tau$

). In jet flows, it is reported that the integral/convective time scale (

$\tau$

). In jet flows, it is reported that the integral/convective time scale (

![]() $\tau _c$

) of the jet governs particle dispersion (Hardalupas, Taylor & Whitelaw Reference Hardalupas, Taylor and Whitelaw1989; Picano et al. Reference Picano, Sardina, Gualtieri and Casciola2010). Hence,

$\tau _c$

) of the jet governs particle dispersion (Hardalupas, Taylor & Whitelaw Reference Hardalupas, Taylor and Whitelaw1989; Picano et al. Reference Picano, Sardina, Gualtieri and Casciola2010). Hence,

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

can be written as

${\textit{St}}$

can be written as

\begin{equation} St = \frac {\tau _{\!p}}{\tau _c} = \frac { \dfrac {\rho _{\!p}\ d_{\!p}^2} {18 \rho _g \nu _g}} {\dfrac {r_{1/2}} {u_c}} .\end{equation}

\begin{equation} St = \frac {\tau _{\!p}}{\tau _c} = \frac { \dfrac {\rho _{\!p}\ d_{\!p}^2} {18 \rho _g \nu _g}} {\dfrac {r_{1/2}} {u_c}} .\end{equation}

In (1.1),

![]() $\rho$

,

$\rho$

,

![]() $\nu$

,

$\nu$

,

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $d$

and

$d$

and

![]() $r_{1/2}$

represent density, kinematic viscosity, flow velocity, diameter and jet half-width, respectively. The subscripts

$r_{1/2}$

represent density, kinematic viscosity, flow velocity, diameter and jet half-width, respectively. The subscripts

![]() $c$

,

$c$

,

![]() $g$

and

$g$

and

![]() $p$

denote jet convective/centreline, gas and particle parameters. The value of

$p$

denote jet convective/centreline, gas and particle parameters. The value of

![]() $\tau _c$

increases with the axial distance from the jet inlet due to the concurrent effect of increasing

$\tau _c$

increases with the axial distance from the jet inlet due to the concurrent effect of increasing

![]() $r_{1/2}$

and decreasing

$r_{1/2}$

and decreasing

![]() $u_c$

. Hence, the local particle

$u_c$

. Hence, the local particle

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

decreases quadratically along the jet centreline (Picano et al. Reference Picano, Sardina, Gualtieri and Casciola2011). Note that

${\textit{St}}$

decreases quadratically along the jet centreline (Picano et al. Reference Picano, Sardina, Gualtieri and Casciola2011). Note that

![]() $\tau _c$

is analogous to the integral time scale (

$\tau _c$

is analogous to the integral time scale (

![]() $\tau _l$

) and at the inlet it is given as

$\tau _l$

) and at the inlet it is given as

![]() $\tau _l = r_{\!j} / u_{\!j}$

, where

$\tau _l = r_{\!j} / u_{\!j}$

, where

![]() $r_{\!j}$

and

$r_{\!j}$

and

![]() $u_{\!j}$

are the jet radius and inlet velocity, respectively. Thus, the initial integral length scale is

$u_{\!j}$

are the jet radius and inlet velocity, respectively. Thus, the initial integral length scale is

![]() $L = r_{\!j}$

.

$L = r_{\!j}$

.

The dispersion rate of particles with

![]() ${\textit{St}} \ll 1$

is similar to the turbulence dispersion, which causes particles to spread evenly within the jet: particles with

${\textit{St}} \ll 1$

is similar to the turbulence dispersion, which causes particles to spread evenly within the jet: particles with

![]() ${\textit{St}} \gg 1$

travel along the jet centreline with minimum radial dispersion; particles with

${\textit{St}} \gg 1$

travel along the jet centreline with minimum radial dispersion; particles with

![]() ${\textit{St}} \approx 1$

depict higher dispersion than the turbulent eddies due to the local vortex-based centrifugal force exerted on them, and they can be completely ejected out of the jet (Chung & Troutt Reference Chung and Troutt1988). These three dispersion mechanisms are termed the vortex, inertial and centrifugal mechanisms (Uthuppan et al. Reference Uthuppan, Aggarwal, Grinstein and Kailasanath1994). Furthermore, since

${\textit{St}} \approx 1$

depict higher dispersion than the turbulent eddies due to the local vortex-based centrifugal force exerted on them, and they can be completely ejected out of the jet (Chung & Troutt Reference Chung and Troutt1988). These three dispersion mechanisms are termed the vortex, inertial and centrifugal mechanisms (Uthuppan et al. Reference Uthuppan, Aggarwal, Grinstein and Kailasanath1994). Furthermore, since

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

decreases axially, a higher local concentration is observed in the jet where the local

${\textit{St}}$

decreases axially, a higher local concentration is observed in the jet where the local

![]() ${\textit{St}} \approx 1$

(Picano et al. Reference Picano, Sardina, Gualtieri and Casciola2011). But eventually, in the far field, particles start behaving as tracers with respect to the large-scale structures, whereas they are ballistic for small-scale velocity fluctuations (Casciola et al. Reference Casciola, Gualtieri, Picano, Sardina and Troiani2010). Hence, as stated earlier, overall in free-shear flows, the dispersion of particles is driven by large-scale vortex structures generated in these flows (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Wen, Yang, Crowe, Chung and Troutt1992). Even in compressible particle-laden flows, which typically involve a larger number of turbulent scales than incompressible flows (Capecelatro & Wagner Reference Capecelatro and Wagner2024), particle clustering is characterised by the large scales and the corresponding

${\textit{St}} \approx 1$

(Picano et al. Reference Picano, Sardina, Gualtieri and Casciola2011). But eventually, in the far field, particles start behaving as tracers with respect to the large-scale structures, whereas they are ballistic for small-scale velocity fluctuations (Casciola et al. Reference Casciola, Gualtieri, Picano, Sardina and Troiani2010). Hence, as stated earlier, overall in free-shear flows, the dispersion of particles is driven by large-scale vortex structures generated in these flows (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Wen, Yang, Crowe, Chung and Troutt1992). Even in compressible particle-laden flows, which typically involve a larger number of turbulent scales than incompressible flows (Capecelatro & Wagner Reference Capecelatro and Wagner2024), particle clustering is characterised by the large scales and the corresponding

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

.

${\textit{St}}$

.

1.3. Particle–turbulence interaction

Although particle transport is governed by the local mean and fluctuating fluid velocity, the presence of particles modulates the local turbulent flow field. The overarching mechanism is that particles act as a medium for augmenting the transport of energy (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Tang, Shen and Dong2017) and momentum (Richter & Sullivan Reference Richter and Sullivan2013) between different regions of the flow. Consequently, as compared with a single-phase jet, particles reduce turbulent intensity by up to

![]() $50\,\%$

(Yuu, Ikeda & Umekage Reference Yuu, Ikeda and Umekage1996). This jet modulation is a function of the particle loading density (Levy & Lockwood Reference Levy and Lockwood1981; Tsuji et al. Reference Tsuji, Morikawa, Tanaka, Karimine and Nishida1988),

$50\,\%$

(Yuu, Ikeda & Umekage Reference Yuu, Ikeda and Umekage1996). This jet modulation is a function of the particle loading density (Levy & Lockwood Reference Levy and Lockwood1981; Tsuji et al. Reference Tsuji, Morikawa, Tanaka, Karimine and Nishida1988),

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

(Kulick, Fessler & Eaton Reference Kulick, Fessler and Eaton1994), particle-to-fluid density ratio, particle diameter to turbulent eddy diameter ratio and the Reynolds number of the particles (

${\textit{St}}$

(Kulick, Fessler & Eaton Reference Kulick, Fessler and Eaton1994), particle-to-fluid density ratio, particle diameter to turbulent eddy diameter ratio and the Reynolds number of the particles (

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

) (Yarin & Hetsroni Reference Yarin and Hetsroni1994). Such interaction between the two phases creates a feedback loop, making this a compounding problem. Thus, to complete the scope of this issue, it is essential to comprehend the particle-based modulation of a jet flow.

${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

) (Yarin & Hetsroni Reference Yarin and Hetsroni1994). Such interaction between the two phases creates a feedback loop, making this a compounding problem. Thus, to complete the scope of this issue, it is essential to comprehend the particle-based modulation of a jet flow.

In the case of supersonic jet flows, smaller particles have been reported to produce a more pronounced modulation of the jet structure as compared with larger particles (Sommerfeld Reference Sommerfeld1994). This is due to the higher specific surface area (ratio of particle surface area to volume) of the smaller particles, which results in stronger fluid–particle momentum exchange at constant particle loading density (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Zhang, Li, Wu and Zou2020). Moreover, even at minimal particle loading, particles have been found to move the Mach disk upstream in supersonic jet flows (Patel et al. Reference Patel, Rubio, Shekhtman, Parziale, Rabinovitch, Ni and Capecelatro2024). This effect further enhances with the increase in particle loading (Lewis Jr & Carlson Reference Lewis and Carlson1964; Jarvinen & Draper Reference Jarvinen and Draper1967). Additionally, phenomena such as attenuation of dilatation, turbulent Mach number, turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation increase with the density of the particles (Xia et al. Reference Xia, Shi, Zhang and Chen2016), further making the fluid–particle interaction in compressible flows perplexing. The transfer of gas kinetic energy to particles restricts the gas expansion, which decreases the gas density and dynamic pressure in the direction of the flow (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Yang, Hu and Wang2023). In supersonic jets, particles also weaken the pressure functions radiated by a supersonic jet, by substantially altering the development of turbulent structures (Greska Reference Greska2005). Consequently, the root-mean-square jet axial (radial) velocity drops by

![]() $10 \,\%$

(

$10 \,\%$

(

![]() $30 \,\%$

), as compared with an unladen jet (Krothapalli et al. Reference Krothapalli, Venkatakrishnan, Lourenco, Greska and Elavarasan2003). This effect is also a function of particle mass loading, such that these pressure fluctuations decrease with the increase in mass loading (Buchta, Shallcross & Capecelatro Reference Buchta, Shallcross and Capecelatro2019).

$30 \,\%$

), as compared with an unladen jet (Krothapalli et al. Reference Krothapalli, Venkatakrishnan, Lourenco, Greska and Elavarasan2003). This effect is also a function of particle mass loading, such that these pressure fluctuations decrease with the increase in mass loading (Buchta, Shallcross & Capecelatro Reference Buchta, Shallcross and Capecelatro2019).

As stated in the discussion above, particle dispersion is primarily credited to the centrifugal force acting on the particles based on particle inertia, even in supersonic flows (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Shao, Li, Zou and Li2021). Here, PC in the axial direction is attributed to the particle–gas momentum transfer, while radial dispersion is credited to the radial inter-phase velocity difference. Note that, in a jet flow in which the particle velocity is less than the fluid velocity at the inlet, particles keep accelerating after leaving the nozzle, consuming the kinetic energy of the supersonic gas. Since the major component of particle inertia is in the streamwise direction, a question arises: Why do particles start travelling in the radial direction in the first place? It is understood that a jet inherently spreads, creating a radial velocity difference between the inertial particle and the local gas. But the particle–gas axial velocity difference is higher in the streamwise direction (up to four times in the present study), and hence particles should keep travelling within the jet centre. We hypothesise that there must be an organised turbulent motion that pushes particles out of the central region of the jet. Local kinematic and thermodynamic aspects, especially fluid viscosity, have been reported to considerably alter the particle distribution in HIT (Saieed & Hickey Reference Saieed and Hickey2022, Reference Saieed and Hickey2023, Reference Saieed and Hickey2024; Saieed, Rahman & Hickey Reference Saieed, Rahman and Hickey2022). In supersonic jet flows, although the local thermodynamic properties of the fluid will change as the jet evolves, these local thermodynamic properties, particularly the fluid viscosity, are assumed to have a minor effect on particle dispersion. In a supersonic jet flow, the variation in density and fluid compressibility governs the fluid–particle interaction, as discussed earlier in this section. Thus, in this contribution, we probe the dispersion of four particle sizes in a supersonic jet flow using direct numerical simulations (DNS). We aim to investigate the local turbulent eddy-based effects that govern the transition of the particles’ motion from axial to radial downstream of the inlet. In the rest of this article, we discuss the methodology of our numerical experiments along with the model validation in § 2, the obtained results in § 3 and the drawn conclusions are reported in § 5.

2. Methodology

We carried out DNS to simulate a spatially developing, polydispersed particle-laden perfectly expanded (shock-free) (Andrews Jr et al. Reference Andrews, Craidon, Dennard and Vick1964; Hinh, Martinuzzi & Johansen Reference Hinh, Martinuzzi and Johansen2025) supersonic jet flow using an in-house version of an effectively parallelised, open-source, high-order finite difference code, known as Pencil-Code (Brandenburg et al. Reference Brandenburg2020). A sixth-order scheme is used for spatial derivatives, and a third-order Runge–Kutta scheme is employed for time integration. To stabilise our sixth-order spatial scheme, which is inherently unstable with finite difference, a hyperdiffusion term was used. The domain pressure was matched with the inlet pressure of the jet to avoid the formation of large-scale shocks. In other words, the ratio of jet exit to domain pressure is maintained at unity (nozzle pressure ratio,

![]() $\mathrm{NPR}= 1$

). These simulations are carried out in a rectangular domain with a periodic boundary condition (BC) in the lateral direction to eliminate wall effects, which are not of interest in the present study. Four particle sizes are considered with two-way coupling using the Lagrangian point-particle tracking scheme, where a tri-linear interpolation method is used for resolving particle trajectories. In this case, the undisturbed local fluid velocity is required to compute the drag force on the particles. However, it is intrinsically unavailable in two-way momentum coupling as particles influence the local flow field (Horwitz & Mani Reference Horwitz and Mani2016, Reference Horwitz and Mani2018). As a result, the Stokes drag on the particles can be underestimated. Thus, the use of the tri-linear interpolation method can be problematic, especially in supersonic flows, and may require a correction to capture the particle trajectories accurately. A metric for estimating the error due to this scheme is the ratio of particle diameter to grid cell length

$\mathrm{NPR}= 1$

). These simulations are carried out in a rectangular domain with a periodic boundary condition (BC) in the lateral direction to eliminate wall effects, which are not of interest in the present study. Four particle sizes are considered with two-way coupling using the Lagrangian point-particle tracking scheme, where a tri-linear interpolation method is used for resolving particle trajectories. In this case, the undisturbed local fluid velocity is required to compute the drag force on the particles. However, it is intrinsically unavailable in two-way momentum coupling as particles influence the local flow field (Horwitz & Mani Reference Horwitz and Mani2016, Reference Horwitz and Mani2018). As a result, the Stokes drag on the particles can be underestimated. Thus, the use of the tri-linear interpolation method can be problematic, especially in supersonic flows, and may require a correction to capture the particle trajectories accurately. A metric for estimating the error due to this scheme is the ratio of particle diameter to grid cell length

![]() $d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}}$

. Since our cell length along

$d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}}$

. Since our cell length along

![]() $x$

is less than in the

$x$

is less than in the

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

directions (

$z$

directions (

![]() $\Delta x \lt \Delta y = \Delta z$

), we define

$\Delta x \lt \Delta y = \Delta z$

), we define

![]() $l_{\textit{cell}} = V_{\textit{cell}}^{1/3}$

, where

$l_{\textit{cell}} = V_{\textit{cell}}^{1/3}$

, where

![]() $V_{\textit{cell}} = \Delta x \times \Delta y \times \Delta z$

is the cell volume. Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Li, Liu, Sun, Yang, Wang, Wang and Li2024) found the tri-linear interpolation method to be invalid if

$V_{\textit{cell}} = \Delta x \times \Delta y \times \Delta z$

is the cell volume. Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Li, Liu, Sun, Yang, Wang, Wang and Li2024) found the tri-linear interpolation method to be invalid if

![]() $d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}}$

is large (

$d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}}$

is large (

![]() $O(10^0)$

). Moreover, Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Rubio, Shekhtman, Parziale, Rabinovitch, Ni and Capecelatro2024) suggested the use of an optimised two-way momentum coupling approach for larger

$O(10^0)$

). Moreover, Patel et al. (Reference Patel, Rubio, Shekhtman, Parziale, Rabinovitch, Ni and Capecelatro2024) suggested the use of an optimised two-way momentum coupling approach for larger

![]() $d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}}$

and shock–particle interaction. However, in our case, the highest

$d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}}$

and shock–particle interaction. However, in our case, the highest

![]() $d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}} = 0.18$

, which is fairly small, and our jet is shock free. Hence, we expect the impact of local disturbed fluid velocity on Stokes drag to be minimal.

$d_{\!p} / l_{\textit{cell}} = 0.18$

, which is fairly small, and our jet is shock free. Hence, we expect the impact of local disturbed fluid velocity on Stokes drag to be minimal.

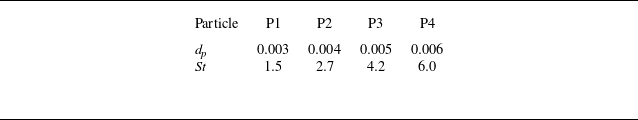

On the other hand, the diameters and initial

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

of these particles are presented in table 1. As seen in table 1, we will refer to these particles with increasing diameter as

${\textit{St}}$

of these particles are presented in table 1. As seen in table 1, we will refer to these particles with increasing diameter as

![]() $\mathrm{P1}$

,

$\mathrm{P1}$

,

![]() $\mathrm{P2}$

,

$\mathrm{P2}$

,

![]() $\mathrm{P3}$

and

$\mathrm{P3}$

and

![]() $\mathrm{P4}$

, for brevity. The constant density of these particles is

$\mathrm{P4}$

, for brevity. The constant density of these particles is

![]() $\rho _{\!p} = 1500$

. In light of our hypothesis, the use of different particle sizes will enable us to probe the local mechanisms that cause particles to start travelling laterally at different downstream locations. For the continuum phase, the gas with a density of

$\rho _{\!p} = 1500$

. In light of our hypothesis, the use of different particle sizes will enable us to probe the local mechanisms that cause particles to start travelling laterally at different downstream locations. For the continuum phase, the gas with a density of

![]() $\rho _g = 1$

is simulated with an Eulerian specification. Our DNS consists of three sub-simulations, as discussed in the following subsections.

$\rho _g = 1$

is simulated with an Eulerian specification. Our DNS consists of three sub-simulations, as discussed in the following subsections.

Table 1. Diameters (

![]() $d_{\!p}$

) and Stokes number (

$d_{\!p}$

) and Stokes number (

![]() ${\textit{St}}$

) at the jet inlet, of the four particle species (denoted

${\textit{St}}$

) at the jet inlet, of the four particle species (denoted

![]() $\mathrm{P1}$

to

$\mathrm{P1}$

to

![]() $\mathrm{P4}$

).

$\mathrm{P4}$

).

2.1. Simulation set-up

2.1.1. Development of HIT

The simulation set-up is depicted in figure 1. Firstly, HIT is generated in a triply periodic box of

![]() $9 d_{\!j}$

characteristic length discretised into a

$9 d_{\!j}$

characteristic length discretised into a

![]() $256^3$

mesh, where

$256^3$

mesh, where

![]() $d_{\!j}$

is the jet diameter. This simulation is conducted without particles and resulted in a Taylor Reynolds number of

$d_{\!j}$

is the jet diameter. This simulation is conducted without particles and resulted in a Taylor Reynolds number of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_\varLambda = \rho _g u_{\textit{rms}} \varLambda / \mu _g = 77$

, where

${\textit{Re}}_\varLambda = \rho _g u_{\textit{rms}} \varLambda / \mu _g = 77$

, where

![]() $\varLambda$

,

$\varLambda$

,

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

and

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

and

![]() $\mu _g$

are the Taylor microscale, fluid root-mean-square velocity and dynamic viscosity, respectively. For HIT development, a solenoidal forcing function is used (Brandenburg Reference Brandenburg2001). This forcing scheme is such that, at any given instance, the random points of energy addition are correlated, but these points vary in time. This simulation is carried out until an equilibrium is established between energy addition and energy dissipation at high wavenumbers (

$\mu _g$

are the Taylor microscale, fluid root-mean-square velocity and dynamic viscosity, respectively. For HIT development, a solenoidal forcing function is used (Brandenburg Reference Brandenburg2001). This forcing scheme is such that, at any given instance, the random points of energy addition are correlated, but these points vary in time. This simulation is carried out until an equilibrium is established between energy addition and energy dissipation at high wavenumbers (

![]() $k$

). This is determined by the fact that the temporal evolution of turbulence statistics such as turbulent kinetic energy (

$k$

). This is determined by the fact that the temporal evolution of turbulence statistics such as turbulent kinetic energy (

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

) starts fluctuating about a steady mean value. Note that, regardless of the forcing scheme used (linear (Rosales & Meneveau Reference Rosales and Meneveau2005; Bassenne et al. Reference Bassenne, Urzay, Park and Moin2016) or spectral (Overholt & Pope Reference Overholt and Pope1998)), turbulence statistics, especially

$\mathrm{TKE}$

) starts fluctuating about a steady mean value. Note that, regardless of the forcing scheme used (linear (Rosales & Meneveau Reference Rosales and Meneveau2005; Bassenne et al. Reference Bassenne, Urzay, Park and Moin2016) or spectral (Overholt & Pope Reference Overholt and Pope1998)), turbulence statistics, especially

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

, depict noticeable fluctuations about a mean value even after the aforementioned equilibrium is established. Since these fluctuations eventually oscillate about a constant mean value, we consider the HIT to be fully developed. This simulation is conducted for approximately

$\mathrm{TKE}$

, depict noticeable fluctuations about a mean value even after the aforementioned equilibrium is established. Since these fluctuations eventually oscillate about a constant mean value, we consider the HIT to be fully developed. This simulation is conducted for approximately

![]() $200$

integral time scales (

$200$

integral time scales (

![]() $\tau _l = r_{\!j} / u_{\!j}$

) computed at the inlet of the jet.

$\tau _l = r_{\!j} / u_{\!j}$

) computed at the inlet of the jet.

Figure 1. Simulation set-up depicting three sub-simulations.

2.1.2. Jet development

Once the HIT is fully developed, three-dimensional (3-D) snapshots of the mean velocity field from the HIT simulation are cyclically introduced at the inlet of a rectangular domain with dimensions

![]() $14 d_{\!j} \times 9 d_{\!j} \times 9 d_{\!j}$

. This domain is meshed into

$14 d_{\!j} \times 9 d_{\!j} \times 9 d_{\!j}$

. This domain is meshed into

![]() $512 \times 256 \times 256$

cells in the

$512 \times 256 \times 256$

cells in the

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

directions. This resulted in grid cells that are longer in the lateral direction, however, all cells in the domain have the same dimensions. The streamwise mesh has more grid points compared with the lateral directions, as our domain is longer in the axial direction. At the inlet of the jet, a top-hat mean flow profile is assumed. This mean flow is superimposed by the turbulence fluctuations generated by the HIT simulation. The 3-D HIT snapshots of the turbulence fluctuations are convected into the domain, which ensures realistic turbulence characteristics within the compressible jet. The pressure at the inlet is set equal to the domain pressure to get a perfectly expanded jet, thus minimising any shocks or large expansion waves. This was done to avoid shock formation, as the interaction of particles with a shock wave will further complicate our model, and it is not in the scope of this analysis.

$z$

directions. This resulted in grid cells that are longer in the lateral direction, however, all cells in the domain have the same dimensions. The streamwise mesh has more grid points compared with the lateral directions, as our domain is longer in the axial direction. At the inlet of the jet, a top-hat mean flow profile is assumed. This mean flow is superimposed by the turbulence fluctuations generated by the HIT simulation. The 3-D HIT snapshots of the turbulence fluctuations are convected into the domain, which ensures realistic turbulence characteristics within the compressible jet. The pressure at the inlet is set equal to the domain pressure to get a perfectly expanded jet, thus minimising any shocks or large expansion waves. This was done to avoid shock formation, as the interaction of particles with a shock wave will further complicate our model, and it is not in the scope of this analysis.

At the inlet and outlet of this domain, inflow and outflow BCs are imposed, respectively. The fluid is allowed to enter the domain only through the jet inlet with a diameter

![]() $d_{\!j} = 1$

, and the rest of the inlet is modelled as a wall. The inlet and outlet boundaries suffered from spurious reflections, however, these reflections at the inlet (Lodato, Domingo & Vervisch Reference Lodato, Domingo and Vervisch2008) and outlet (Poinsot & Lelef Reference Poinsot and Lelef1992) are attenuated with a Navier–Stokes Characteristic Boundary Condition.

$d_{\!j} = 1$

, and the rest of the inlet is modelled as a wall. The inlet and outlet boundaries suffered from spurious reflections, however, these reflections at the inlet (Lodato, Domingo & Vervisch Reference Lodato, Domingo and Vervisch2008) and outlet (Poinsot & Lelef Reference Poinsot and Lelef1992) are attenuated with a Navier–Stokes Characteristic Boundary Condition.

A periodic BC is prescribed in the two lateral directions (

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

). This is done to deal with a limitation of Pencil-Code; where if outflow BC is imposed on the

$z$

). This is done to deal with a limitation of Pencil-Code; where if outflow BC is imposed on the

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

boundaries, the reflections from the edges between these boundaries result in discontinuities. This simulation is run for roughly

$z$

boundaries, the reflections from the edges between these boundaries result in discontinuities. This simulation is run for roughly

![]() $7$

flow through times (FTT), such that the initial transience caused by the jet development diminishes and a stable jet flow is established. For assessing this state of the jet, self-similarly of the classical flow statistics is analysed in § 2.4.

$7$

flow through times (FTT), such that the initial transience caused by the jet development diminishes and a stable jet flow is established. For assessing this state of the jet, self-similarly of the classical flow statistics is analysed in § 2.4.

2.1.3. Particle-laden jet

From the last state of the jet development simulation, a third simulation is initiated, which is run for an additional

![]() $5$

FTT. In total,

$5$

FTT. In total,

![]() $200\,000$

adiabatic particles equally divided into four particle species are released within the jet diameter at the inlet with a steady rate of approximately

$200\,000$

adiabatic particles equally divided into four particle species are released within the jet diameter at the inlet with a steady rate of approximately

![]() $1300$

particles/

$1300$

particles/

![]() $\tau _l$

. These particles are introduced with a random velocity in the

$\tau _l$

. These particles are introduced with a random velocity in the

![]() $x$

-direction such that at the inlet, the particle velocity (

$x$

-direction such that at the inlet, the particle velocity (

![]() $u_{\!p}$

) is less than the local gas velocity (

$u_{\!p}$

) is less than the local gas velocity (

![]() $u_g (x_{\!p})$

). To avoid shock formation at the particle surface, the particle velocity at the inlet is never below half of the local fluid velocity. Consequently, particles are accelerated by the gas via drag force, as viscous drag is the only force acting on the particles, considering

$u_g (x_{\!p})$

). To avoid shock formation at the particle surface, the particle velocity at the inlet is never below half of the local fluid velocity. Consequently, particles are accelerated by the gas via drag force, as viscous drag is the only force acting on the particles, considering

![]() $\rho _{\!p} / \rho _g \gg 1$

(Maxey & Riley Reference Maxey and Riley1983). Moreover, the gravitational force is also neglected for simplicity.

$\rho _{\!p} / \rho _g \gg 1$

(Maxey & Riley Reference Maxey and Riley1983). Moreover, the gravitational force is also neglected for simplicity.

In this simulation, the first

![]() $3$

FTT are to stabilise the particle-laden jet flow, as the introduction of particles modulates the jet flow due to two-way momentum coupling. The following

$3$

FTT are to stabilise the particle-laden jet flow, as the introduction of particles modulates the jet flow due to two-way momentum coupling. The following

![]() $2$

FTT are used for collecting the results presented in this paper. Note that all the statistics discussed in this paper are temporally averaged unless stated otherwise. Considering the particle loading density, the maximum instantaneous volume fraction in the overall domain is

$2$

FTT are used for collecting the results presented in this paper. Note that all the statistics discussed in this paper are temporally averaged unless stated otherwise. Considering the particle loading density, the maximum instantaneous volume fraction in the overall domain is

![]() $ \theta _{\!p} \approx O(10^{-6})$

, which is within the one-way coupling regime (Elghobashi Reference Elghobashi1994). But, because particles are released within the narrow region of

$ \theta _{\!p} \approx O(10^{-6})$

, which is within the one-way coupling regime (Elghobashi Reference Elghobashi1994). But, because particles are released within the narrow region of

![]() $d_{\!j} = 1$

and in the supersonic flow, particles travel within the central region of the jet for a considerable distance. This causes the local

$d_{\!j} = 1$

and in the supersonic flow, particles travel within the central region of the jet for a considerable distance. This causes the local

![]() $\theta _{\!p}$

within the core of the jet to be as high as

$\theta _{\!p}$

within the core of the jet to be as high as

![]() $O(10^{-4})$

, which is within the two-way coupled regime. Moreover, PC in the jet can also result in higher local

$O(10^{-4})$

, which is within the two-way coupled regime. Moreover, PC in the jet can also result in higher local

![]() $\theta _{\!p}$

, even though the global

$\theta _{\!p}$

, even though the global

![]() $\theta _{\!p}$

is in the dilute regime (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Shao, Li, Zou and Li2021). Hence, two-way momentum coupling is employed in the present study.

$\theta _{\!p}$

is in the dilute regime (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Shao, Li, Zou and Li2021). Hence, two-way momentum coupling is employed in the present study.

2.2. Continuum phase

The non-dimensional equation set for the gaseous phase is given as

where the variables

![]() $T$

,

$T$

,

![]() $P$

,

$P$

,

![]() $\kappa$

,

$\kappa$

,

![]() $s$

,

$s$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}$

and

$\boldsymbol{S}$

and

![]() $\zeta$

depict temperature, pressure, thermal conductivity, entropy, shear-rate tensor and bulk viscosity (

$\zeta$

depict temperature, pressure, thermal conductivity, entropy, shear-rate tensor and bulk viscosity (

![]() $\zeta = 0.0006$

), respectively. Here,

$\zeta = 0.0006$

), respectively. Here,

![]() $\kappa$

was kept constant. In (2.3), typically a particle-based work term (

$\kappa$

was kept constant. In (2.3), typically a particle-based work term (

![]() $F_{\!p} \boldsymbol{\cdot }u_{\!p}$

) is included on the right-hand side. In our study, this term is ignored as it is found to be much smaller (not shown here) than the dissipation term in (2.3). Furthermore, this term becomes significant at high particle loading density, which is not the case in the present simulation. Therefore, neglecting its contribution to the entropy equation has a negligible effect on the results.

$F_{\!p} \boldsymbol{\cdot }u_{\!p}$

) is included on the right-hand side. In our study, this term is ignored as it is found to be much smaller (not shown here) than the dissipation term in (2.3). Furthermore, this term becomes significant at high particle loading density, which is not the case in the present simulation. Therefore, neglecting its contribution to the entropy equation has a negligible effect on the results.

The gas dynamic viscosity is modelled with a power law

where subscript

![]() $0$

represents the initial/reference state and

$0$

represents the initial/reference state and

![]() $\mu _{g,0} = 0.001$

is the initial/reference gas dynamic viscosity. The initial temperature of both particles and gas is

$\mu _{g,0} = 0.001$

is the initial/reference gas dynamic viscosity. The initial temperature of both particles and gas is

![]() $T_0 = 1$

.

$T_0 = 1$

.

2.3. Particulate phase

The non-dimensional Lagrangian equations for particle transport are

In (2.6), the particle drag coefficient

![]() $C_{\!D}$

is adopted from Carlson & Hoglund (Reference Carlson and Hoglund1964)

$C_{\!D}$

is adopted from Carlson & Hoglund (Reference Carlson and Hoglund1964)

\begin{equation} C_{\!D} = \frac {24}{{\textit{Re}}_{\!p}} \left [ \frac {\big (1+0.15 {\textit{Re}}_{\!p}^{0.687}\big) \big (1 + \exp {\big(0.427/{\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}^{4.63} \big ) - \big (3/{\textit{Re}}_{\!p}^{0.88} \big )} \big )} {1 + (1/\alpha ) (3.82 + 1.28 \exp {(-1.25 \alpha )} ) } \right ]\! ,\end{equation}

\begin{equation} C_{\!D} = \frac {24}{{\textit{Re}}_{\!p}} \left [ \frac {\big (1+0.15 {\textit{Re}}_{\!p}^{0.687}\big) \big (1 + \exp {\big(0.427/{\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}^{4.63} \big ) - \big (3/{\textit{Re}}_{\!p}^{0.88} \big )} \big )} {1 + (1/\alpha ) (3.82 + 1.28 \exp {(-1.25 \alpha )} ) } \right ]\! ,\end{equation}

where

![]() $\alpha$

is the ratio of the Reynolds and Mach numbers (

$\alpha$

is the ratio of the Reynolds and Mach numbers (

![]() $\alpha = {\textit{Re}}_{\!p}/{\textit{Ma}}_{\!P}$

) of the particles. The parameters

$\alpha = {\textit{Re}}_{\!p}/{\textit{Ma}}_{\!P}$

) of the particles. The parameters

![]() ${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

and

${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

are expressed as

${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

are expressed as

where

![]() $c$

is the speed of sound. We chose this expression for

$c$

is the speed of sound. We chose this expression for

![]() $C_{\!D}$

as it incorporates inertial, compressibility and rarefaction effects. Also, it is valid for particle Mach numbers

$C_{\!D}$

as it incorporates inertial, compressibility and rarefaction effects. Also, it is valid for particle Mach numbers

![]() ${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p} \lt 2$

and particle Reynolds numbers

${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p} \lt 2$

and particle Reynolds numbers

![]() $O(10^{-1}) \leqslant {\textit{Re}}_{\!p} \leqslant O(10^{2})$

. In our case, the average

$O(10^{-1}) \leqslant {\textit{Re}}_{\!p} \leqslant O(10^{2})$

. In our case, the average

![]() ${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

in the first

${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

in the first

![]() $0.5 d_{\!j}$

of the domain is

$0.5 d_{\!j}$

of the domain is

![]() ${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p} \approx 0.45$

, and the corresponding particle Reynolds number is

${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p} \approx 0.45$

, and the corresponding particle Reynolds number is

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\!p} \approx 0.64$

. Note that particles are introduced with random velocity in the

${\textit{Re}}_{\!p} \approx 0.64$

. Note that particles are introduced with random velocity in the

![]() $x$

-direction, and the gas velocity is the highest close to the inlet. Thus, our

$x$

-direction, and the gas velocity is the highest close to the inlet. Thus, our

![]() ${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

and

${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

values are maximum at the start of the domain. Beyond this, gas decelerates and the particles’ velocity approaches the gas velocity, causing

${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

values are maximum at the start of the domain. Beyond this, gas decelerates and the particles’ velocity approaches the gas velocity, causing

![]() ${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

and

${\textit{Ma}}_{\!p}$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

to drop.

${\textit{Re}}_{\!p}$

to drop.

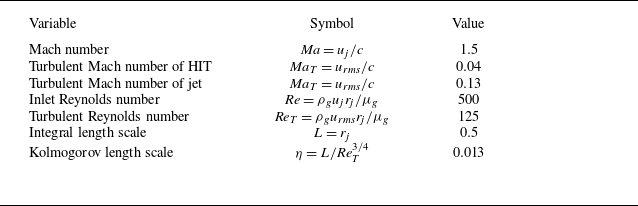

Considering the discussion above, the turbulence parameters of the particle-laden jet flow simulation are given in table 2. Note that, in table 2, for computing

![]() ${\textit{Ma}}_T$

the average

${\textit{Ma}}_T$

the average

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

of the entire domain is used, while

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

of the entire domain is used, while

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_T$

is computed with the maximum

${\textit{Re}}_T$

is computed with the maximum

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

. For all four particle species

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

. For all four particle species

![]() $\rho _{\!p} / \rho _g \gg 1$

,

$\rho _{\!p} / \rho _g \gg 1$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\!p} \leqslant 1$

and

${\textit{Re}}_{\!p} \leqslant 1$

and

![]() $d_{\!j} \lt \eta$

, where

$d_{\!j} \lt \eta$

, where

![]() $\eta$

represent the Kolmogorov length scale. Based on these criteria, the use of the point-particle scheme is justified (Balachandar & Eaton Reference Balachandar and Eaton2010).

$\eta$

represent the Kolmogorov length scale. Based on these criteria, the use of the point-particle scheme is justified (Balachandar & Eaton Reference Balachandar and Eaton2010).

Table 2. Turbulence characteristics of the supersonic jet flow.

The drag force on the particles (

![]() $F_{\!D}$

) is given as

$F_{\!D}$

) is given as

where

![]() $u_{\!p}$

is the particle velocity and

$u_{\!p}$

is the particle velocity and

![]() $u_g (x_{\!p})$

is the gas velocity at the particle’s position. Similarly, in (2.2), the term

$u_g (x_{\!p})$

is the gas velocity at the particle’s position. Similarly, in (2.2), the term

![]() $F_{\!p}$

accounts for the back-reaction force on the local gas by the particles due to two-way momentum coupling. This force is defined as

$F_{\!p}$

accounts for the back-reaction force on the local gas by the particles due to two-way momentum coupling. This force is defined as

\begin{equation} F_{\!p} = \sum _i^{N_{\!p}} W_{\!p} (x - x_{p,i}) F_{\!D} ,\end{equation}

\begin{equation} F_{\!p} = \sum _i^{N_{\!p}} W_{\!p} (x - x_{p,i}) F_{\!D} ,\end{equation}

where

![]() $N_{\!p}$

is the total number of particles in a given cell. The term

$N_{\!p}$

is the total number of particles in a given cell. The term

![]() $W_{\!p} (x - x_{p,i} )$

is the weighing function for the triangular-shaped cloud (TSC) approach, which is employed for modelling the two-way fluid–particle interaction (Hockney & Eastwood Reference Hockney and Eastwood2021). In TSC, a second-order spline interpolation is carried out on

$W_{\!p} (x - x_{p,i} )$

is the weighing function for the triangular-shaped cloud (TSC) approach, which is employed for modelling the two-way fluid–particle interaction (Hockney & Eastwood Reference Hockney and Eastwood2021). In TSC, a second-order spline interpolation is carried out on

![]() $27$

neighbouring points on the Cartesian grid. In this approach, a weight function is used to project particle properties onto a grid point, such that this weight function depends on the proximity of a grid point to the particle. The grid point closer to a particle gets a higher weight and vice versa. Thus, in a 3-D grid, fluid–particle interaction is projected on

$27$

neighbouring points on the Cartesian grid. In this approach, a weight function is used to project particle properties onto a grid point, such that this weight function depends on the proximity of a grid point to the particle. The grid point closer to a particle gets a higher weight and vice versa. Thus, in a 3-D grid, fluid–particle interaction is projected on

![]() $3 \times 3 \times 3$

grid points. In this case, even if two particles are present within the same cell, their proximity to the nearest

$3 \times 3 \times 3$

grid points. In this case, even if two particles are present within the same cell, their proximity to the nearest

![]() $27$

points will be different. This results in a smooth interaction between the two phases.

$27$

points will be different. This results in a smooth interaction between the two phases.

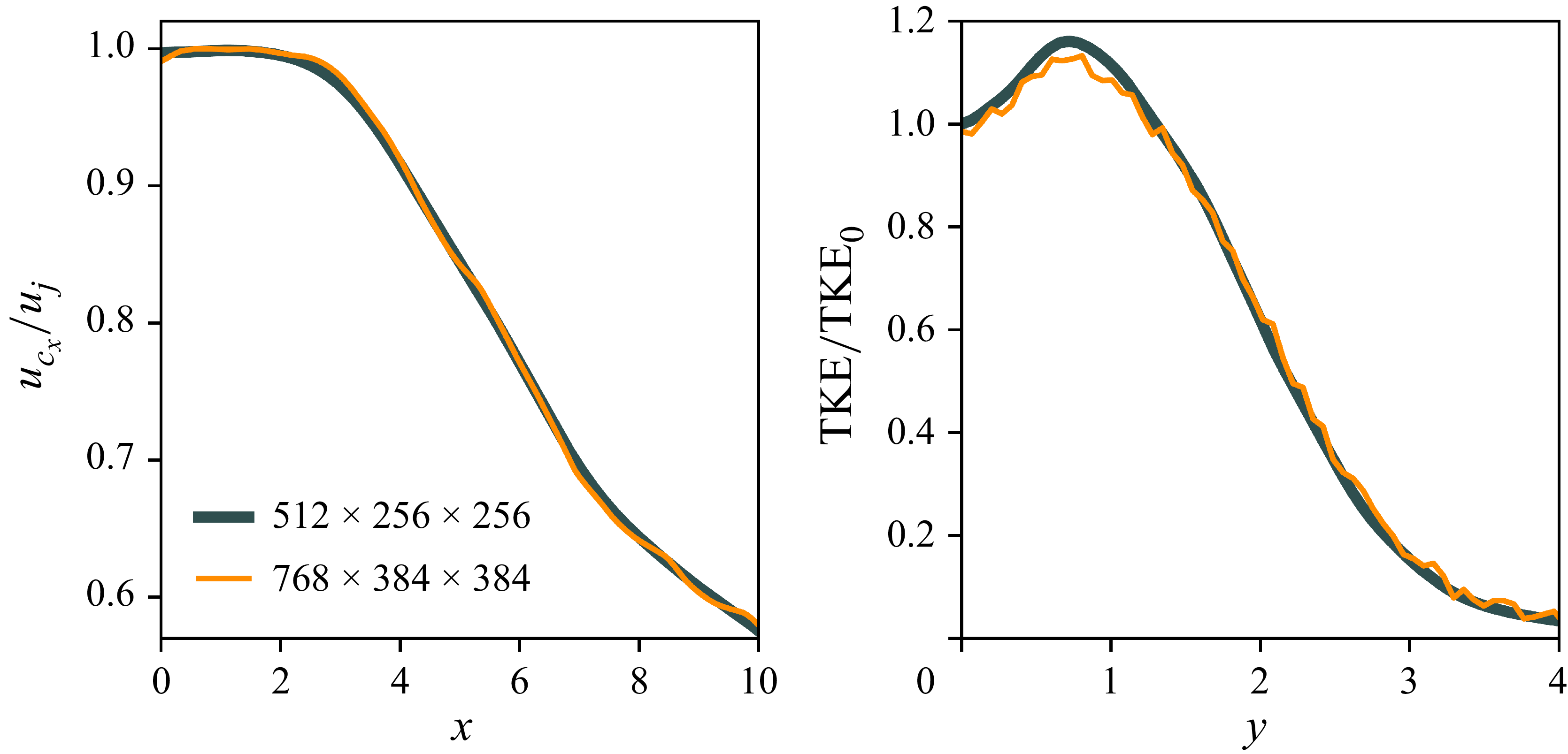

2.4. Validation

To validate the present simulation set-up, we run the jet simulation at the same conditions but without particles, for approximately

![]() $7$

FTT. First, we assess whether our

$7$

FTT. First, we assess whether our

![]() $512 \times 256 \times 256$

mesh is grid converged. For this purpose, we run another simulation with a

$512 \times 256 \times 256$

mesh is grid converged. For this purpose, we run another simulation with a

![]() $768 \times 384 \times 384$

mesh without particles for

$768 \times 384 \times 384$

mesh without particles for

![]() $3$

FTT. The resulting radial profiles of the axial component of the jet centreline velocity (

$3$

FTT. The resulting radial profiles of the axial component of the jet centreline velocity (

![]() $u_{c_x}$

) and azimuthally averaged

$u_{c_x}$

) and azimuthally averaged

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

at the downstream location of

$\mathrm{TKE}$

at the downstream location of

![]() $x=8$

of these two cases are presented in figure 2. Note that in figure 2 and in the rest of the article, all the dimensions such as

$x=8$

of these two cases are presented in figure 2. Note that in figure 2 and in the rest of the article, all the dimensions such as

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

are normalised with

$y$

are normalised with

![]() $d_{\!j}$

, unless stated otherwise. Reynolds-averaged results are presented, instead of Favre averaging, as the density fluctuations are modest in the flow. It can be seen in figure 2 that both curves of the centreline velocity and

$d_{\!j}$

, unless stated otherwise. Reynolds-averaged results are presented, instead of Favre averaging, as the density fluctuations are modest in the flow. It can be seen in figure 2 that both curves of the centreline velocity and

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

overlap reasonably well, justifying our mesh selection. The

$\mathrm{TKE}$

overlap reasonably well, justifying our mesh selection. The

![]() $768 \times 384 \times 384$

results are not as smooth because they were averaged over fewer time frames as compared with the baseline mesh. It should be noted that, despite modelling a domain length of

$768 \times 384 \times 384$

results are not as smooth because they were averaged over fewer time frames as compared with the baseline mesh. It should be noted that, despite modelling a domain length of

![]() $14 d_{\!j}$

, we only show results up to

$14 d_{\!j}$

, we only show results up to

![]() $x = 10$

as the latter portion of the domain is influenced, to some extent, by the outflow BC. Since the simulations are conducted in Cartesian coordinates, the results are averaged in the azimuthal direction and in time. The grid independence analysis of our two-way coupling scheme is presented in Appendix A.

$x = 10$

as the latter portion of the domain is influenced, to some extent, by the outflow BC. Since the simulations are conducted in Cartesian coordinates, the results are averaged in the azimuthal direction and in time. The grid independence analysis of our two-way coupling scheme is presented in Appendix A.

Figure 2. Normalised axial component of the jet centreline velocity (

![]() $u_{c_x}$

), and azimuthally average

$u_{c_x}$

), and azimuthally average

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

at

$\mathrm{TKE}$

at

![]() $x=8$

of the

$x=8$

of the

![]() $512 \times 256 \times 256$

and

$512 \times 256 \times 256$

and

![]() $768 \times 384 \times 384$

meshes.

$768 \times 384 \times 384$

meshes.

Figure 3. Radial evolution of temporal and azimuthal mean axial velocity,

![]() $u_x$

(left), and root-mean-square gas velocity,

$u_x$

(left), and root-mean-square gas velocity,

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

(right), of the single-phase jet flow at five axial locations. In the left plot,

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

(right), of the single-phase jet flow at five axial locations. In the left plot,

![]() $\mathrm{TM}$

represents Troutt & McLaughlin (Reference Troutt and McLaughlin1982), particularly the solution of (2.11).

$\mathrm{TM}$

represents Troutt & McLaughlin (Reference Troutt and McLaughlin1982), particularly the solution of (2.11).

For the validation of our simulation, we first compare our axial velocity profile in the radial direction with that of Troutt & McLaughlin (Reference Troutt and McLaughlin1982) (TM), which is defined as

In (2.11),

![]() $\xi$

is given as

$\xi$

is given as

where

![]() $y$

is the value along the radial direction. Based on this normalisation, the mean axial velocity in the radial direction collapses reasonably well on the curve obtained from (2.11) from

$y$

is the value along the radial direction. Based on this normalisation, the mean axial velocity in the radial direction collapses reasonably well on the curve obtained from (2.11) from

![]() $x=6$

onward, see figure 3. This suggests that our first-order statistics become approximately self-similar around

$x=6$

onward, see figure 3. This suggests that our first-order statistics become approximately self-similar around

![]() $x=6$

, which is relatively short. This axial distance is a function of flow

$x=6$

, which is relatively short. This axial distance is a function of flow

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

, and for lower

${\textit{Re}}$

, and for lower

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

, self-similarity is achieved at a shorter axial distance (Bogey & Bailly Reference Bogey and Bailly2006); a short time evolution to reach first-order self-similarity was also shown in other free-shear flows (Hickey, Hussain & Wu Reference Hickey, Hussain and Wu2013). Note that Bogey & Bailly (Reference Bogey and Bailly2006) analysed transitional jets; the present jet flow lies between transitional and fully developed jets as we impose a turbulent plug flow at the inlet (from a separate HIT simulation). However, a similar effect of

${\textit{Re}}$

, self-similarity is achieved at a shorter axial distance (Bogey & Bailly Reference Bogey and Bailly2006); a short time evolution to reach first-order self-similarity was also shown in other free-shear flows (Hickey, Hussain & Wu Reference Hickey, Hussain and Wu2013). Note that Bogey & Bailly (Reference Bogey and Bailly2006) analysed transitional jets; the present jet flow lies between transitional and fully developed jets as we impose a turbulent plug flow at the inlet (from a separate HIT simulation). However, a similar effect of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

on self-similarity evolution is expected to hold in the present case. According to figure 3, the outer edge of the jet slightly departs from the self-similar curves defined in (2.11). This is due to the periodic BC on the lateral boundaries and the spatially evolving jet, which results in non-zero free-stream velocity; as this velocity remains small, it does not affect the analysis.

${\textit{Re}}$

on self-similarity evolution is expected to hold in the present case. According to figure 3, the outer edge of the jet slightly departs from the self-similar curves defined in (2.11). This is due to the periodic BC on the lateral boundaries and the spatially evolving jet, which results in non-zero free-stream velocity; as this velocity remains small, it does not affect the analysis.

It should be noted that higher-order statistics take longer to achieve self-similarity (Hickey et al. Reference Hickey, Hussain and Wu2013; Shin, Sandberg & Richardson Reference Shin, Sandberg and Richardson2017). This is because high-order self-similarity requires an equilibrium state to be reached within the turbulence. We can see this in the lateral evolution of the normalised root-mean-square velocity (

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

) of the jet, as shown in figure 3. To determine

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

) of the jet, as shown in figure 3. To determine

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

, we first temporally averaged the 3-D fluid velocity field. Then we estimated the fluid velocity fluctuations at each time instance by carrying out a Reynolds decomposition using the instantaneous and temporally averaged velocity fields. By averaging and computing the square root of this 3-D array of velocity fluctuations,

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

, we first temporally averaged the 3-D fluid velocity field. Then we estimated the fluid velocity fluctuations at each time instance by carrying out a Reynolds decomposition using the instantaneous and temporally averaged velocity fields. By averaging and computing the square root of this 3-D array of velocity fluctuations,

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

was determined. Figure 3 presents the characteristic

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

was determined. Figure 3 presents the characteristic

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

curves, with lower

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

curves, with lower

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

at the jet centre and higher values near the jet edge. To be precise, the curves of

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

at the jet centre and higher values near the jet edge. To be precise, the curves of

![]() $x=8$

and

$x=8$

and

![]() $10$

do not overlap close to the centre of the jet, which is not truly self-similar. A similar lack of self-similarity of higher-order statistics was also observed in the high-speed wake, despite a much longer flow evolution (Hickey, Hussain & Wu Reference Hickey, Hussain and Wu2016), which is tied to the strong memory effects in the free-shear flow’s evolution. Since our first-order statistics are self-similar and the second-order statistics show the expected behaviour for the considered domain length, our simulation model is acceptable for analysing the dispersion of inertial particles in a supersonic jet.

$10$

do not overlap close to the centre of the jet, which is not truly self-similar. A similar lack of self-similarity of higher-order statistics was also observed in the high-speed wake, despite a much longer flow evolution (Hickey, Hussain & Wu Reference Hickey, Hussain and Wu2016), which is tied to the strong memory effects in the free-shear flow’s evolution. Since our first-order statistics are self-similar and the second-order statistics show the expected behaviour for the considered domain length, our simulation model is acceptable for analysing the dispersion of inertial particles in a supersonic jet.

3. Results

In a supersonic jet, the highest velocity component is located along the jet centreline (recall figure 3), as observed in figure 4 in which vortices are depicted with the

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion (Hunt, Wray & Moin Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988) and particles are coloured with the local gas velocity (

$\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion (Hunt, Wray & Moin Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988) and particles are coloured with the local gas velocity (

![]() $u_g$

). The

$u_g$

). The

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion is mathematically defined as

$\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion is mathematically defined as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{\omega }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\omega }$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}$

are the rotational and strain-rate tensors, respectively. In (3.1),

$\boldsymbol{S}$

are the rotational and strain-rate tensors, respectively. In (3.1),

![]() $\Vert \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Vert$

represents the magnitude. Mathematically,

$\Vert \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Vert$

represents the magnitude. Mathematically,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\omega }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\omega }$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}$

are the anti-symmetric and symmetric components of the instantaneous velocity gradient tensor, such that

$\boldsymbol{S}$

are the anti-symmetric and symmetric components of the instantaneous velocity gradient tensor, such that

In (3.2) and (3.3), the superscript

![]() $\mathrm{T}$

represents the matrix transpose.

$\mathrm{T}$

represents the matrix transpose.

As

![]() $u_g$

is highest along the jet centreline (see figure 4), it follows that particles should travel along this centre axis due to the higher particle–fluid slip velocity, which governs the direction of the drag force experienced by the particles. However, figure 4 reveals that particles are dispersed away from the jet centreline at different streamwise locations based on their size. In this case, smaller particles are ejected radially from the central region of the jet at a shorter downstream distance as compared with their larger counterparts. As the characteristic size of the largest eddies grows with the streamwise evolution of the jet, it is plausible that the particles of different sizes are preferentially dispersed at distinct axial locations as the turbulent structures grow.

$u_g$

is highest along the jet centreline (see figure 4), it follows that particles should travel along this centre axis due to the higher particle–fluid slip velocity, which governs the direction of the drag force experienced by the particles. However, figure 4 reveals that particles are dispersed away from the jet centreline at different streamwise locations based on their size. In this case, smaller particles are ejected radially from the central region of the jet at a shorter downstream distance as compared with their larger counterparts. As the characteristic size of the largest eddies grows with the streamwise evolution of the jet, it is plausible that the particles of different sizes are preferentially dispersed at distinct axial locations as the turbulent structures grow.

Figure 4. Fluid vortices shown with

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion (top), overlaid with particles (bottom) of the considered four species as titled. The vortices in the top image and particles in the bottom four images are coloured with the gas velocity (

$\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion (top), overlaid with particles (bottom) of the considered four species as titled. The vortices in the top image and particles in the bottom four images are coloured with the gas velocity (

![]() $u_g$

). Recall that the particle size increases from

$u_g$

). Recall that the particle size increases from

![]() $\mathrm{P1}$

to

$\mathrm{P1}$

to

![]() $\mathrm{P4}$

.

$\mathrm{P4}$

.

Figure 5. Logarithmic correlation integral,

![]() $\mathrm{log} (C_l)$

(left), with respect to the inter-particle distance,

$\mathrm{log} (C_l)$

(left), with respect to the inter-particle distance,

![]() $l$

, normalised with the initial inter-particle distance,

$l$

, normalised with the initial inter-particle distance,

![]() $l_0$

. The correlation dimension (

$l_0$

. The correlation dimension (

![]() $D_2$

) of each curve is shown in the legend. The variation in

$D_2$

) of each curve is shown in the legend. The variation in

![]() $D_2$

with normalised cluster volume (

$D_2$

with normalised cluster volume (

![]() $V_c$

) is shown in the plot on the right. The grey-shaded area highlights the region containing the inflexion points.

$V_c$

) is shown in the plot on the right. The grey-shaded area highlights the region containing the inflexion points.

3.1. Fractal dimension analysis

To scrutinise the aforementioned hypothesis, we adopt the fractal dimension analysis, as particle dispersion is multi-fractal in nature (Bec Reference Bec2005). Here, particle clustering shows distinct fractal features at different turbulent scales, or, in other words, particles with different inertia primarily respond to eddies of different sizes (Eaton & Fessler Reference Eaton and Fessler1994). Thus, we perform the fractal dimension analysis on the global particle dispersion, as well as on the individual particle clusters. First, we compute the correlation dimension (

![]() $D_2$

) of each particle species, which characterises the dispersion pattern (chaotic or organised) of the particles (Grassberger & Procaccia Reference Grassberger and Procaccia1983). The parameter

$D_2$

) of each particle species, which characterises the dispersion pattern (chaotic or organised) of the particles (Grassberger & Procaccia Reference Grassberger and Procaccia1983). The parameter

![]() $D_2$

is expressed as

$D_2$

is expressed as

where

![]() $C_l = \sum p_i^2$

is the correlation integral, and

$C_l = \sum p_i^2$

is the correlation integral, and

![]() $p_i$

is the probability of finding a particle pair at an inter-particle distance less than

$p_i$

is the probability of finding a particle pair at an inter-particle distance less than

![]() $l$

. By plotting the logarithmic correlation integral (

$l$

. By plotting the logarithmic correlation integral (

![]() $\log (C_l)$

) against the log of the normalised separation distance,

$\log (C_l)$

) against the log of the normalised separation distance,

![]() $D_2$

can be approximated as the slope of the obtained curve. This is shown in figure 5 (a), and the corresponding

$D_2$

can be approximated as the slope of the obtained curve. This is shown in figure 5 (a), and the corresponding

![]() $D_2$

value of each particle species is shown in the legend, marked with the particle species number as a subscript. The fundamental benefit of using

$D_2$

value of each particle species is shown in the legend, marked with the particle species number as a subscript. The fundamental benefit of using

![]() $D_2$

to characterise the dispersion is that it is not dependent on the choice of the length scale. On the other hand, methods such as box counting depend on the box size (Borgani & Murante Reference Borgani and Murante1994) , and pair-correlation function is influenced by the radius (Monchaux, Bourgoin & Cartellier Reference Monchaux, Bourgoin and Cartellier2012) in which the number of particle pairs is counted.

$D_2$

to characterise the dispersion is that it is not dependent on the choice of the length scale. On the other hand, methods such as box counting depend on the box size (Borgani & Murante Reference Borgani and Murante1994) , and pair-correlation function is influenced by the radius (Monchaux, Bourgoin & Cartellier Reference Monchaux, Bourgoin and Cartellier2012) in which the number of particle pairs is counted.

For

![]() $D_2$

, a lower value depicts a more organised (clustered) dispersion of the particles; a higher value shows chaotic dispersion. As

$D_2$

, a lower value depicts a more organised (clustered) dispersion of the particles; a higher value shows chaotic dispersion. As

![]() $D_2$

decreases with the increase in particle size in figure 5, it validates the qualitative observations of figure 4, where smaller particles are more dispersed as they start spreading laterally after a short axial distance from the inlet, while larger particles primarily travel along the jet axis. Thus,

$D_2$

decreases with the increase in particle size in figure 5, it validates the qualitative observations of figure 4, where smaller particles are more dispersed as they start spreading laterally after a short axial distance from the inlet, while larger particles primarily travel along the jet axis. Thus,

![]() $\mathrm{P4}$

particles depict organised (clustered) dispersion.

$\mathrm{P4}$

particles depict organised (clustered) dispersion.

By analysing

![]() $D_2$

of the individual particle cluster, we can probe if the fractal dimension changes based on the cluster size. If it does, it would indicate that the cluster size varies based on the turbulent scale (since particle clustering is governed by particles’ dominant correspondence to a turbulent scale), which would hint at the mechanism that causes particles to spread laterally at different downstream distances. Note that

$D_2$

of the individual particle cluster, we can probe if the fractal dimension changes based on the cluster size. If it does, it would indicate that the cluster size varies based on the turbulent scale (since particle clustering is governed by particles’ dominant correspondence to a turbulent scale), which would hint at the mechanism that causes particles to spread laterally at different downstream distances. Note that

![]() $D_2$

indicates the scale of clustering, where a lower

$D_2$

indicates the scale of clustering, where a lower

![]() $D_2$

depicts clustering due to the larger scales, while a higher

$D_2$

depicts clustering due to the larger scales, while a higher

![]() $D_2$

relates clustering to the small-scale features (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Wen, Yang, Crowe, Chung and Troutt1992). Considering the visual observation in figure 4, the scale at which clustering occurs should increase with the increase in particle size. We witness this trend in figure 5 (b), where

$D_2$

relates clustering to the small-scale features (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Wen, Yang, Crowe, Chung and Troutt1992). Considering the visual observation in figure 4, the scale at which clustering occurs should increase with the increase in particle size. We witness this trend in figure 5 (b), where

![]() $D_2$

is plotted against the cluster volume (

$D_2$

is plotted against the cluster volume (

![]() $V_c$

). The dispersion dimensionality of these curves also verifies the qualitative observation of figure 4. Here,

$V_c$

). The dispersion dimensionality of these curves also verifies the qualitative observation of figure 4. Here,

![]() $V_c$

is determined by using the density-based spatial clustering of application with noise (DBSCAN) method (Ester et al. Reference Ester1996), which segregates clustered particles from noise/unclustered particles. By computing the convex hull using the

$V_c$

is determined by using the density-based spatial clustering of application with noise (DBSCAN) method (Ester et al. Reference Ester1996), which segregates clustered particles from noise/unclustered particles. By computing the convex hull using the

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

separations between particles in each cluster,

$z$

separations between particles in each cluster,

![]() $V_c$

is evaluated. The details of the DBSCAN method in the present context can be found in Saieed & Hickey (Reference Saieed and Hickey2024).

$V_c$

is evaluated. The details of the DBSCAN method in the present context can be found in Saieed & Hickey (Reference Saieed and Hickey2024).

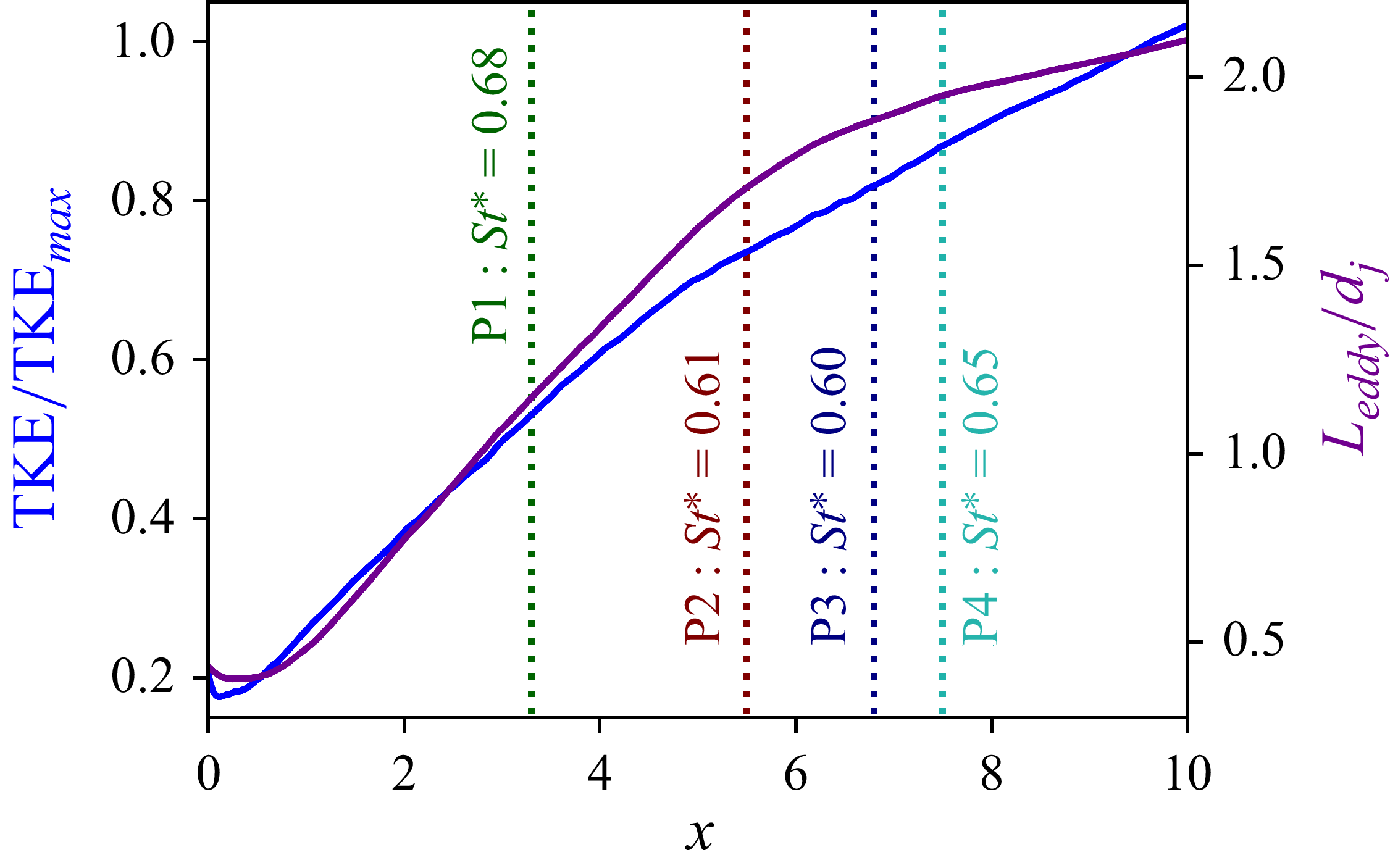

The downward curves in figure 5 (b) portray a critical observation: the

![]() $D_2$

rises quasi-linearly until it reaches an inflexion point. This inflexion point marks the boundary between chaotic (rising

$D_2$

rises quasi-linearly until it reaches an inflexion point. This inflexion point marks the boundary between chaotic (rising

![]() $D_2$

with respect to

$D_2$

with respect to

![]() $V_c$

) and organised (declining

$V_c$

) and organised (declining

![]() $D_2$

with respect to

$D_2$

with respect to

![]() $V_c$

) dispersion regimes; these inflexion points are approximately highlighted with a grey colour region. This trend, however, seems counterintuitive because the eddy size increases with the axial distance. But the rise in

$V_c$

) dispersion regimes; these inflexion points are approximately highlighted with a grey colour region. This trend, however, seems counterintuitive because the eddy size increases with the axial distance. But the rise in

![]() $D_2$

with

$D_2$

with

![]() $V_c$

on the left side of the grey region containing inflexion points means that particle clustering is governed by turbulence at smaller scales. This can be understood with the fact that, in the present

$V_c$

on the left side of the grey region containing inflexion points means that particle clustering is governed by turbulence at smaller scales. This can be understood with the fact that, in the present

![]() $10 d_{\!j}$

domain length, which is essentially the near-field region of the jet, the turbulent fluctuations and thus the averaged

$10 d_{\!j}$

domain length, which is essentially the near-field region of the jet, the turbulent fluctuations and thus the averaged

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

augments as the local eddy length scale (

$\mathrm{TKE}$

augments as the local eddy length scale (

![]() $L_{\textit{eddy}}$

) increases downstream, see figure 6. The rise in downstream turbulent fluctuations at the jet centreline can be witnessed in figure 3 (b). Additionally, the

$L_{\textit{eddy}}$

) increases downstream, see figure 6. The rise in downstream turbulent fluctuations at the jet centreline can be witnessed in figure 3 (b). Additionally, the

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

in figure 6 is the bulk

$\mathrm{TKE}$

in figure 6 is the bulk

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

of the flow, which is computed by averaging

$\mathrm{TKE}$

of the flow, which is computed by averaging

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

in the radial direction for each grid point along the

$\mathrm{TKE}$

in the radial direction for each grid point along the

![]() $x$

-axis. Therefore, because we are in the near-field region where shear is high at the inlet (shear layer is significant) and the jet is spreading, the bulk

$x$

-axis. Therefore, because we are in the near-field region where shear is high at the inlet (shear layer is significant) and the jet is spreading, the bulk

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

increases as the velocity fluctuations are high in this region (

$\mathrm{TKE}$

increases as the velocity fluctuations are high in this region (

![]() $x=10$

).

$x=10$

).

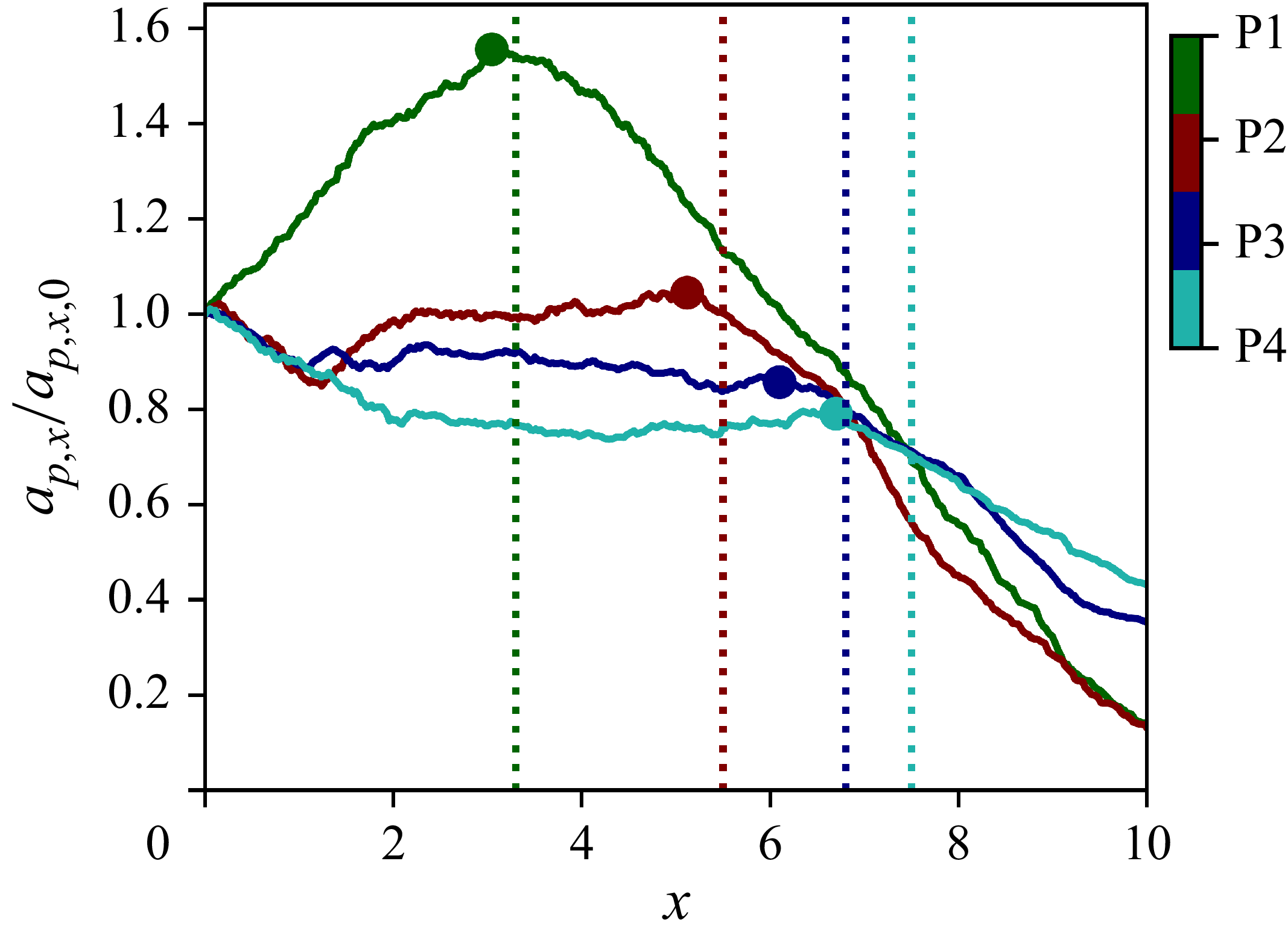

Figure 6. Evolution of temporally and spatially averaged

![]() $\mathrm{TKE}$

and eddy length scale (

$\mathrm{TKE}$

and eddy length scale (

![]() $L_{\textit{eddy}}$

). Here,

$L_{\textit{eddy}}$

). Here,

![]() $L_{\textit{eddy}}$

is normalised with jet diameter

$L_{\textit{eddy}}$

is normalised with jet diameter

![]() $d_{\!j}$

. The dotted vertical lines mark the axial location (

$d_{\!j}$

. The dotted vertical lines mark the axial location (

![]() $x_r$

) of the respective particle initial radial dispersion, where

$x_r$

) of the respective particle initial radial dispersion, where

![]() ${\textit{St}}^*$

is the local Stokes number of the particles at that location (discussed in § 3.3).

${\textit{St}}^*$

is the local Stokes number of the particles at that location (discussed in § 3.3).

In figure 6, the

![]() $L_{\textit{eddy}}$

is computed by identifying vortices with the

$L_{\textit{eddy}}$

is computed by identifying vortices with the

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion and labelling dominant vortices on the

$\mathcal{Q}$

-criterion and labelling dominant vortices on the

![]() $y$

-

$y$

-

![]() $z$

plane at each

$z$

plane at each

![]() $x$

position by applying an approximate threshold (

$x$

position by applying an approximate threshold (

![]() $\mathcal{Q} \gt \overline {\mathcal{Q}}$

). Each detected vortex has a peak value of

$\mathcal{Q} \gt \overline {\mathcal{Q}}$

). Each detected vortex has a peak value of

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$