As a result of the treaties of World War I, Romania doubled in size, both geographically and demographically. The Regat (the principalities of Wallachia and Moldova), Transylvania, Bessarabia, and Bukovina were among the territories that comprised Greater Romania.Footnote 1 Each of these regions was distinctly unique in its blend of traditions, languages, and social customs; and each had a vibrant Jewish population of vital social, political, and economic importance (Janowski et al Reference Janowski, Iordachi and Trencsényi2005). However, Romanian Jews differed as much, if not more, than the ethnic Romanians in each of the country’s regions.

The newly annexed region of Bessarabia in the east had a Jewish population of seven percent in the 1930 census. These communities, previously under Tsarist rule, were traditionally involved in agriculture and experienced more restrictions regarding property ownership, trade, and cultural institutions than those in Bukovina. Bessarabia was also regarded as a “breeding ground” for modern Jewish politics, with a significant number of Zionists as well as communist groups (Vago Reference Vago1994, 31). Exaggerated claims of Bessarabian Jews supporting Soviet Russia was a reason Antonescu enacted stricter measures to eradicate their communities during the war. Bukovina, along with Banat and Transylvania, were zones of multi-ethnic contact between Germans, Hungarians, Jews, Roma, Romanians, and Ukrainians, among others. These regions, in contrast to Bessarabia, were previously part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which provided a greater degree of political and economic freedom for minorities and, unlike Romania, had granted citizenship rights to all Jews. The Jewish community in 1930 reached eleven percent of Bukovina’s population and Czernowitz, the region’s capitol, depended heavily on Jewish individuals in the political, economic, and social spheres of the city. Statistics from 1930 show Jews held 79.3% of commerce, 66.4% of credit, and 35.3% of industry in Bukovina, similar to figures in Bessarabia, where Jews held 77.4% of commerce, 54.8% of credit, and 42.3% of industry (Solonari Reference Solonari2010, 222).

Jewish communities in Romanian lands experienced difficulties throughout the interwar years as ultra-nationalist politicians sought to deprive them of their rights. Various influential Jewish representatives, such as lawyer Wilhelm Filderman, attempted to offer protection to Romanian Jews no matter their residence and place of origin.Footnote 2 In June 1940, the Soviet Union conquered Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, separating the Jewish communities there from the rest of Romania until Romanian forces reconquered the regions in July 1941. The year of Soviet occupation also had a weakening affect on the Jewish communities in these territories. Many Jewish institutions were closed and leaders and intellectuals exiled (Levin Reference Levin1995, 37–39). The return of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to Romanian authority in 1941 only worsened the situation of these communities, where they were now viewed by Romanian leader Marshal Ion Antonescu as former Soviet citizens and communist sympathizers.

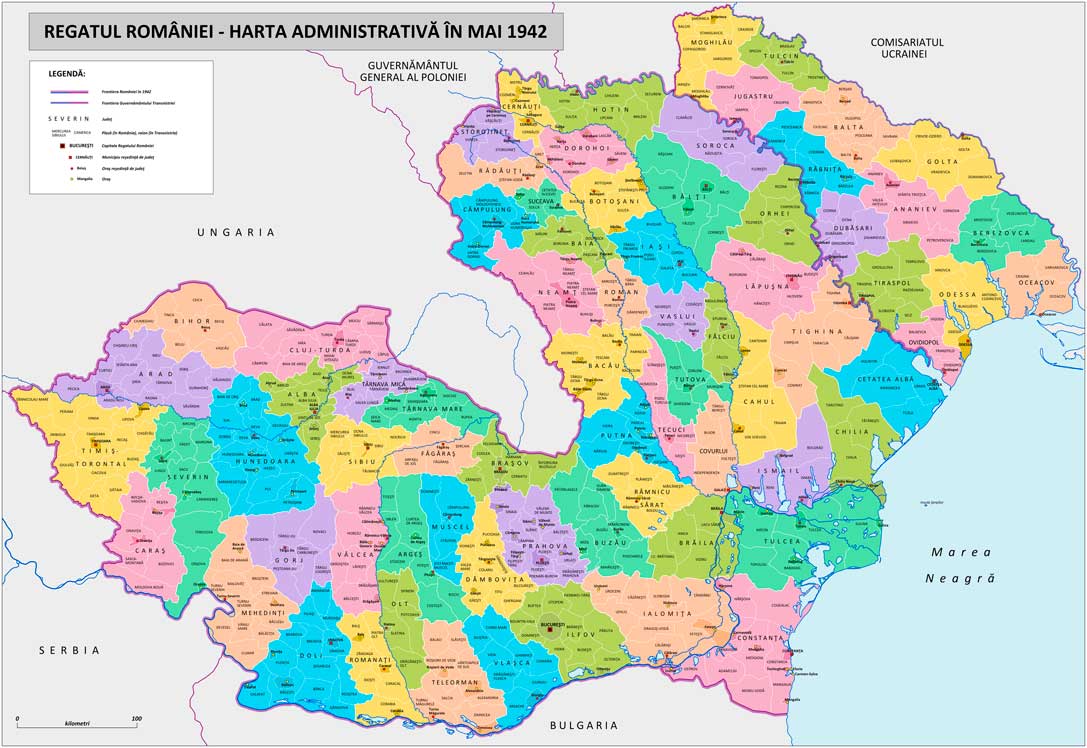

Less than two months later on August 30, 1941, the Nazi-German government ceded the region of Transnistria—the land between the Dniester River and the Bug River—to its Romanian ally through the signing of the Tighina Agreement (Ofer Reference Ofer2009, 32; see Figure 1).Footnote 3 Prior to German occupation, Transnistria was part of the Soviet Union, where great effort was placed toward integrating Jews into Soviet society and presenting anti-Semitism as archaic and bourgeois (Dumitru Reference Dumitru2016, 93–138). Nevertheless, leaders had been purged during the interwar period and Jewish institutions shut down, such that the German occupational forces often appointed any Jewish men, many without leadership experience, to head the newly formed wartime Jewish councils (Altshuler Reference Altshuler2012, 252–253; Arad Reference Arad2009, 118). Unlike Romania’s other territories, Transnistria did not have a large ethnic Romanian population nor was it of great political or sentimental significance. The land became for Antonescu a dumping ground for Romania’s Jews.

Figure 1 Romania including the regions of Bukovina, Bessarabia, and Transnistria, 1942 (Andrein Reference Andrein2011).

Shargorod

Between 1940 and 1945, Jews deported from Bukovina, Bessarabia, and the Regat, as well as local Transnistrian Jews, were lumped together and forced to depend on one another for survival. One such place of Jewish conglomeration in Transnistria was the Shargorod ghetto. I use the more common spelling of Shargorod for the town; variants include Șargorod, Sargorot, and Sharhorod. The town of Shargorod can be studied as a microcosm to better understand what occurred in the majority of ghettos in Transnistria.Footnote 4 Shargorod had been a thriving shtetl in the late 18th and early 19th century: an important center of trade as well as Jewish culture and religious life in the Podolia region (Petrovsky-Shtern Reference Petrovsky-Shtern2014). During the Soviet years, a local stated, “If there were any expressions of anti-Semitism before the war, they would elicit nothing but surprise or bewilderment, so strange they would seem” (Ivankovitser Reference Ivankovitser2002). The changing politics of the region—growing anti-Semitism under tsarist rule and then Sovietization after 1917—transformed Jewish life in Shargorod and the Jewish character of the town.

In November 1941, about 5,000 Jewish deportees from Bessarabia and Bukovina arrived in Shargorod. These were added to the approximately 2,000 remaining local Jews (Teich Reference Teich1958, 232; Inspectoratul General al Jandarmeriei, Direcțiunea Siguranței și Ord. Publice, September 1, 1943, in Carp Reference Carp1996, 207, 334, 457).Footnote 5 The majority of deportees originated from the Southern Bukovinan city of Suceava with groups from Căuşeni, Vatra Dornei, Câmpulung, Vijnița, Czernowitz, and Dorohoi. Deportees in general tried to reach fellow deportees from their hometowns. Jews from Șiret (Southern Bukovina) bribed officials to reach the Djurin ghetto where their neighbors had been sent (Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 187). In Moghilev there were many from Rădăuți or Czernowitz, while the Jews of Suceava largely made it to Shargorod. However, there was always a mix of deportees and locals within the ghetto which produced tension, exacerbating difficulties while at other times ameliorating them.

How, then, did the individuals interred in ghettos from different social, economic, and political backgrounds focus their tactics for survival? Jewish locals and deportees in Shargorod, one of the largest ghettos in Romanian-occupied Transnistria, were faced with overcoming the limitations of regional loyalties or identities, and redefining their notions of belonging through building institutions that would lead to survival for a portion of the ghetto inhabitants.

By identity, I refer to the loyalty toward certain ideas, claims to ancestry, and adherence to a system of mores that an individual or group internalizes, as well as the characteristics they exhibit, which enable others to recognize the individual or group (Rotenstreich Reference Rotenstreich1993, 50). Historian Leon J. Goldstein reveals the complexities of Jewish identity or identities—a glimpse of what Jews faced in Shargorod and in other ghettos and camps during the Holocaust:

“When we realize how dispersed over natural and social space the Jewish people are, how differently Jews are affected by social, cultural, and intellectual elements, the variability in their conceptions of themselves is hardly to be wondered at. Even within the same highly complex societies, different Jews are affected by different sets of circumstances, and so a variety of different kinds of reshaping occurs. There is, to be sure, a sense of awareness, the recognition that, for better or for worse, all are Jews, the understanding of which is so variable as to be dazzling” (Goldstein Reference Goldstein1993, 90). Jewish communities in the territories under Romanian rule provide a great example of the reshaping mentioned above.

This microstudy of the Shargorod ghetto provides a “thick description” of this particular ghetto and thus contributes to the study of the Holocaust in Romania and Holocaust studies in general. When possible, the situation in Shargorod is compared with that of other Transnistrian or Nazi-occupied ghettos to provide a wider historical context. The article uses a majority of published sources, including Benjamin M. Grilj, Sergij Osatschuk, and Dmytro Zhmundyljak’s 2013 collection of wartime letters from Transnistrian deportees, in an attempt to understand the fierce struggle of Shargorod’s victims and survivors and to open the field to more research on the topic of regional identity in Romania and across Europe. The methods of survival in Shargorod are best analyzed through the ghetto inhabitants’ selection of leadership, the entrepreneurial and aid actions that arose, and the format and agenda adopted by the ghetto cultural institutions.

Choosing leadership

Establishing something akin to the kahals of former Jewish communities was not only a necessity for cohesion and efficiency, but also a requirement by the occupying Romanian and German powers. However, choosing a committee simultaneously protected and tore down the ghetto communities. The regions’ different histories of Tsarist/Soviet, Romanian, and Austrian rule created communities with varying ideologies, traditions, economies, and governing and administrative styles. Prior to such issues of organization was the burden of survival. Ideal leaders, whether appointed by the state or self-appointed, had to be aware of the desperate situation of all Jews.

Meier Teich, who would become the committee leader of the Shargorod ghetto, described the arrival of his group in the crowded transit ghetto of Atachi, en route to Transnistria, as a sign of impending doom for the Jews already in the town. These Jews would be deported to the work camps across the Dniester to make room for even more arrivals. Teich wrote that the previous groups considered his party their enemies despite their similar plight (Carp Reference Carp1996, 323).Footnote 6 It was difficult to build strong and fair leadership in such hostile and uncertain situations. This carried over into the new settlements as poverty-stricken local Jews had to make room in their ghettos for beleaguered deportees.

Strong leadership was vital for the survival of both groups: local and deportee. Vadim Altskan’s analysis of the Zhmerinka ghetto reveals a conglomeration of Jewish communities similar to the situation in Shargorod and most of the other Transnistrian ghettos. The Romanian Jewish deportees provided leaders who could interact with the occupying authorities due to their linguistic skills and their Romanian administrative and economic savvy. However, the local Ukrainian Jews knew the physical and social terrain of Shargorod. They had contacts with former neighbors and knew where to gain access to much needed resources, such as food and clothing (Altskan Reference Altskan2012, 12; Dumitru Reference Dumitru2009, 43). Shared knowledge of Yiddish enabled ghetto residents to communicate among themselves, but this did not always mean rapport, as each regional group had different priorities and opinions. Many Transnistrian Jews may have only known Ukrainian or Russian, making communication more difficult.

In Shargorod, as in many of the other Transnistrian ghettos, it was the deportees from Bukovina who took leadership positions. These communities came by train and were often accompanied by their leaders along with some possessions, unlike the Bessarabian Jews. Priority was placed on a leader who could speak to the authorities in German or Romanian. The Shargorod County governor initially appointed Max Rosenrauch, from Suceava, as chairman of the ghetto. Moshe Katz from Rădăuți was assigned as his deputy. They were described as having the trust and admiration of the deportees. However, the representatives of the different community councils within the ghetto soon reached a consensus to form a central council composed of 25 delegates from among the deportee communities, including four Jewish locals. On November 17, 1941, these appointed Meier Teich as chairman and Abraham Reicher as deputy, with an inner council of eight men (Berthold Sponder Testimony, 27/PKR, Yad Vashem, in Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 236).

Teich was experienced in dealing with the Romanian authorities due to his previous position as president of a cooperative in Suceava and as former chairman of the Suceava Jewish Council (“Rumanian Jews,” July 15, 1943, The Canadian Jewish Review, 7; Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei, Bucharest, Romania, County Directory Suceava; 425, fond 4, inventory 4 and 387, folder 14/1937). Teich also had ties to international Jewish communities (Resolutions of the 16th Zionist Conference 1930, 69). In his analysis of the ghetto’s self-administration, Teich claimed that Bucharest lawyer and advocate Wilhelm Filderman also supported him by sending a telegram to local Jews in Mogilev, instructing them to assist Teich (Teich Reference Teich1958, 227). The election of leadership in Shargorod seemed to have occurred smoothly.

By contrast, in the Zhmerinka ghetto, clear animosity existed between Berl Ochakovskiy, the former local Ukrainian Jewish head of the ghetto labor department, and new leader Adolph Herschmann, a deportee from Czernowitz. Their disagreement led to the death of Ochakovskiy (Altskan Reference Altskan2012, 15). Teich’s appointment showed that the inhabitants of Shargorod took initiative to choose their own leader rather than the one chosen by the Romanian authorities, and they did so within days after the arrival of the deportees. Teich claimed that the directors of the provisional Jewish community (the Obcina), which included two Bessarabian deportees, received him warmly on his arrival in Shargorod and sought to assist him in any way possible. It was at their initiative that Teich took advantage of the tension between the Ukrainian and the Romanian authorities in the town to the benefit of the ghetto residents. Teich must have also had help from local leadership to draw up for the authorities his authorization as the new ghetto head, written in Ukrainian (and Romanian; Teich Reference Teich1958, 229). Unfortunately, there is little evidence from local Jews on their opinion of the leadership selection process. Bukovina Jews remained, as in most Transnistrian ghettos, at the forefront of ghetto organization, but valuable information continued to come from the Jewish locals.

An important criticism of Teich was that his ghetto council was composed of members with Suceava origins and, similarly, those from Suceava mostly received clerical jobs rather than manual labor (Deletant Reference Deletant2005, 26). The same thing occurred in Mogilev and other ghettos. However, according to Marusia Cirstea’s archival research, Teich was beaten by Jewish residents on his return to Suceava because of “abusive and inhuman treatment” of fellow Suceavans in the Shargorod ghetto (Cîrstea Reference Cîrstea, Liviu Damean and Liciu2011, 447; Arhivele Nationale Istorice Centrale, Bucharest, Romania, fond Directia Generala a Poliției, dosar 4/1946, Buletinul Informative al Direcției Generale a Poliției, nr. 160, 11 noiembrie 1946). The identity of the attackers and a description of the abusive treatment claimed are not provided. The strongest complaints against Teich, likely concerning the issue of forced labor, seemed to come from Bukovinians and, specifically, fellow Suceava Jews rather than from the locals. Zechariah Pitaru, a deportee from Dorohoi, was another opponent of Teich for what he saw as favoritism toward southern Bukovina Jews and resentful for his son being sent to forced labor. Pitaru created his own Jewish committee and police force in nearby Capușterna, similar in structure to the organization in Sharogord (Tibon Reference Tibon2016a, 162–163, 168). Forced labor and the committee members who compiled such lists were a source of consternation in the ghetto community and of great controversy among survivors after the war.

Nevertheless, Teich’s account provided a balanced analysis of Jewish leadership with its many nuances and circumstances, which faced similar problems across Nazi-occupied and Nazi-allied Europe. He admitted to strict regulations regarding forced labor selections and his denial of showing favoritism holds some truth if, as Cirstea argues, even some from his native Suceava found reasons to blame him. The following section will go into more detail on how ghetto leaders dealt with forced labor lists in Shargorod. It is important to note that unlike Zmerinka’s Adolph Herschmann, Djurin’s Max Rosenrauch, or even Mogilev’s resourceful Siegfried Jagendorf, Teich sought to transcend regional loyalties. As an example, he put his own life in jeopardy in an attempt to save six Jews from Dorohoi and from Rădăuți caught outside permissible areas on the road between the ghettos of Shargorod and Djurin. On March 20, 1942, Teich, along with Leib Goldschläger, called for a just trial for Strul and Smil Ceauș from Dorohoi, and Marcus Rauchman, Simeon Goldenberg, Roza Goldenberg, and Mina Wainiș from Rădăuți, but they were seconds too late as the six were shot in the Polish cemetary of Shargorod. When he failed to reach the executioner, Sergeant Major Florian, in time, he asked for documentation to be provided regarding the process of indictment, arguing that more papers were involved in burying a horse a few days earlier (Teich, “Masacru la Sargorod,” in Carp Reference Carp1996, 350). Teich fought for his coreligionists, not only the ones from Suceava, even after their deaths, knowing that if such injustice went unaddressed it would encourage more impunity on the part of the gendarmes.

The formation of the Shargorod Jewish police force further reveals the breaking of regional barriers in choosing leadership. Unlike the dreaded ghetto police in Lodz, Warsaw, Lublin, and Nowy Dwor, who collaborated ruthlessly with the Nazi regime, the Jewish police in Shargorod were often remembered with appreciation (Trunk Reference Trunk1972, 480, 492; Weiss Reference Weiss1979, 201–217, 228–233). Initially set up for self-defense against local police, the Shargorod ghetto police was headed by Bruno Koch of Câmpulung, a former reserve officer in the Romanian army. It was comprised of seventeen men, including two Jewish locals. The ghetto police managed to stop the assaults committed by mostly young local Ukrainian townspeople and Romanian gendarmes and was soon called upon to settle internal disputes. By their efforts the Ukrainian municipal militia was disbanded, but they faced much initial abuse by gendarmes until their authority was accepted (Peninah-Faina Pollack, 03/1220/Peh, Yad Vashem, in Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 269; Teich Reference Teich1958, 230–231).

The participation of ghetto policemen in the communist partisan movement, with the approval of Teich and Koch, made Shargorod an even more interesting case of deportee-local cooperation. By spring 1943, Teich and others helped hide partisan commanders and met secretly with a Russian general to gain his support should the ghetto be in danger of liquidation (Carp Reference Carp1996, 290, 306; Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 362). Shargorod police and committee leaders took great risks in protecting partisans, among them many local Jews. In other ghettos, such as Bershad, leaders discovered to be in contact with partisans were shot (Teich Reference Teich1958, 247). Despite the threat of death, Shargorod leaders bypassed regional loyalties to help the local Jewish partisans. The ghetto police sought to protect and provide justice regardless of a ghetto member’s origin.

Meier Teich remains the central figure of the Shargorod ghetto. Analyzing his leadership reveals the difficulties that many in his position faced. It is telling however, that when the Russian NKVD units arrested him upon their reoccupation of the region, it was the outcry of Shargorod’s united Jewish community that saved him from sharing the same fate of execution as Zmerinka ghetto’s Adolph Herschmann (Vynokurova Reference Vynokurova2010, 26). Teich remains a controversial figure. Though the evidence shows that Shargorod’s leadership was comprised mostly of deportees from Bukovina (perhaps as much as 21 out of 25 committee members), such a decision was likely reached with the approval of Jews both local and from Romania.

They seemed to agree that the Bukovinians were best suited for resolving issues of finagling through administrative barriers and of maintaining cordial relationships with Romanian, Ukrainian, and Russian authorities. Unfortunately, most accounts are from the point of view of the leading deportees, marginalizing the local Jewish voices. The following sections will attempt to bring them in as much as possible to reveal the establishment of other vital institutions in the ghetto.

Making a livable ghetto: entrepreneur actions and aid

On arrival, a majority of deportees recalled their impressions of Shargorod as a town with small, old, clay houses (Baruch Reference Baruch2017, 63–72). There were about 337 of these houses, poorly constructed and with little ventilation, according to the account of Marcu Rozen, who was deported to Shargorod from Dorohoi at age eleven (Rozen Reference Rozen2004, 8). Approximately 7,000 ghetto inhabitants (deportees and locals) had to house themselves in these. One Suceavan deportee wrote home that up to 20 people lived in a single room (Doc. 201, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 979–983; Teich Reference Teich1958, 232).Footnote 7 During the first months, the deportees organized themselves according to place of origin, attracted to what was, naturally, more familiar.

The Jews from Suceava arrived with the most resources, and they were the first to set up a soup kitchen, a bakery, and a small store. However, these were for the exclusive use of deportees from Suceava. The Jews from Câmpulung managed to open a store and sold food at a low cost to fellow Câmpulung deportees. By contrast, those who came from Dorohoi, Vijnița, Vatra Dornei, and Czernowitz arrived in winter with few belongings and received very little initial support. The majority survived by eating potato peelings, similar to the situation in Kopaigorod and other Transnistrian ghettos, as described by survivor Ietti Leibovici from Vatra Dornei (Leibovici Reference Leibovici2008).Footnote 8 Survivor Zecharyah Petru recalled the heartbreaking story of a mother who sought aid for her starving daughter but was refused because the money sent to the council was to be used only for those from a specific community of origin (Zecharyah Petru, Yad Vashem in Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 251). In the Djurin ghetto, committee secretary Lipman Konstadt from Radauți condemned ghetto head Max Rosenrauch, from Suceava, for his refusal to give equal care to local Jews (Ofer Reference Ofer1996, 270–271; Ofer Reference Ofer2009, 38). Konstadt stands out among Bukovinian deportee leaders in Transnistria for his early support of locals and as an example of how difficult it was to create solidarity among the various Jewish deportee and local groups.

The last deportees to arrive in Shargoord on November 16, 1941 were the 900 Dorohoi Jews. Saved from almost certain death through the intervention of Shargorod’s Ukrainian peasant women, the ghetto had little room for them (Carp Reference Carp1996, 276, 334; Teich Reference Teich1958, 231–232). A deportee from Rădăuți wrote in a personal letter dated November 1941 that the Dorohoi Jews were suffering worst among the ghetto inhabitants and that their community leaders back home should send them money. This is another example of ghetto inhabitants relying on exclusivist aid based on place of origins to survive. Every community was expected to fend for its own members (Tibon Reference Tibon2016b). However, the same letter described Teich as doing all he could for those from Dorohoi despite being the “leader of those from Suceava” (Doc. 194, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 931).

Money was, in fact, sent to the Dorohoi Jews and to others, but it was often lost on the way (Iancu Reference Iancu2008, 345–351; Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 298).Footnote 9 This left the Dorohoi deportees at the mercy of others. Simon Meer, from Suceava, but living with an aunt in Dorohoi when he was deported to Shargorod in November 1941, recalled the situation differently in a 2008 interview. He said that the Bucovinians in Shargorod worked with the gendarme commandant to move his group of around 500 Dorohoi deportees to the village of Capușterna in 1943 until repatriated to Romania (Meer Reference Meer2008). By this time the danger from the Romanian and German armies and administration had subsided, making such a move a hygienic benefit for all. Historian Gali Tibon clarifies the reasons behind the move of Dorohoi deportees from Shargorod to Capușterna as in part initiated by a Dorohoi deportee (Reference Tibon2016a, 162). Fellow ghetto dwellers continued to mention in their letters the particular plight of those from Dorohoi (Doc. 5, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 58–63).

However, even within the same community of origin, not everyone benefitted equally. A deportee from Suceava wrote that those who came to Shargorod from Bukovina in the third transport with Teich were better off than his family, who came in the second transport and had lost much of their luggage due to the many stops made in other localities (Doc. 201, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 979–983). Others remarked that, though they were happy to be surrounded by acquaintances, regrettably, people could not help each other, but instead had to look out for themselves (Doc. 124, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 606–609). Those who did try to help found that some abused their charity. Gusta, at an unknown ghetto in Transnistria, wrote to relatives that she gave money to a fellow Jew from Radauți who returned soon after, claiming she was to give him 5,000 more Lei. She wrote to her family: “My darlings, nowadays, you shouldn’t get too involved with other people because time has stopped people [from] being ashamed and made them think others are required to help them” (Doc. 189, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 893). Even the tie of community origin was not strong enough to procure aid or was used to harass people into giving money. Identity in such cases did not surpass the individual’s physical needs.

Some deportees recorded that they received more help from those outside of their communities of origin. In Mogilev, Ruth and Fritz wrote to their parents in Cernowitz that their acquaintances from home, living in the room adjacent to theirs in the ghetto, would have nothing to do with them. They said strangers were more willing to help them than their own family (Doc. 99, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 470–474). Anna Dahl wrote that the people with whom she stayed in Mogilev (locals and fellow deportees) were nice and helpful (Doc. 156, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 738–741). A Bessarabian deportee to Mogilev recalled that on their arrival they were met with two kinds of people. The Jews from Suceava and Rădăuți, who still had suitcases and clothes, either refused to let the Bessarabian Jews into their dewllings due to fear of disease or, the second type, took pity on them, fed, and clothed them (Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 188). In Djurin, the local rabbi, Hershel Karalnik, ensured the majority of deportees were placed in the homes of local Jews. One thousand were lodged in stables outside of town, but he provided them with blankets and other necessities (Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 280).

In Shargorod also, the local Jews were described as opening up their homes to the deportees. A deportee family in Shargorod wrote in early December 1941 that all deportees lived in homes of local Jews who had taken them in. Ichel Pogranichny, a local Shargorod survivor, recalled that deportees from Romania lived in their home, making it a total of 20 in the house (Doc. 213, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 1067; Pogranichny, “I Witnessed It All,” in Zabarko Reference Zabarko2005, 209). Letters confiscated from couriers coming from Transnistria reveal that even non-Jewish locals took in Jews, despite the illegality. A deportee, likely from Câmpulung, wrote of staying with her child in the home of a local Christian woman (Doc. 118, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 580–584). She may have had money or things to trade, which would more likely allow such a situation. It was, nevertheless, risky on the part of the local Ukrainian woman. Local Jews often had no choice but to house the deportees since there was limited housing in the ghetto. However, there was seldom evidence of refusal or hostility on their part.

The different interactions described above show that strict isolationism by region of origin, as originally intended, was not sustainable. The Jews in the Shargorod ghetto first attempted to dismiss regional barriers for hygienic reasons. Various letters and survivors mentioned that there were no toilets in Shargorod. The new committee organized the construction of six public bathrooms. Teich wrote that there was tension with the locals regarding this because they thought energy and resources were better used elsewhere (Doc. 201, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 983; Carp Reference Carp1996, 334). Faina Vynokurova, in her study of the Bukovinian Jews in Transnistria, argues that they taught the local Jews the organization of a daily routine, observance and presevation of religious traditions, as well as craftsman skills, things lost during the two decades of Soviet propaganda (2010, 23; Rechter in Cohen et al Reference Cohen, Frankel and Hoffman2010, 211).Footnote 10 However, firsthand accounts show a sharing of resources and skills, though the Bukovinians indeed had more at their disposal due to their previous financial state and the nature of their deportations.

By working together, and for the benefit of the new community, an electrical plant was set up in Shargorod and some local factories reopened. The dirt roads were turned into cobblestone streets and cleaned daily (Carp Reference Carp1996, 294; Teich Reference Teich1958, 235, 240). The issue of forced labor lists (and lists in general), a painful subject in Holocaust studies due to the controversy regarding ghetto leadership, seemed to have been dealt with fairly in Shargorod. Testimonies of local Jewish survivors reveal that in some ghettos they were the first listed for forced labor across the Bug River because they did not have leaders to intercede for them as had the deportees (Ofer Reference Ofer1996, 252).

More research needs to be done on corroborating Teich’s testimony, but evidence presented earlier in the article, regarding Suceavans on labor lists, point to a more impartial situation in Shargorod. “There was no favoritism before misery and death,” claimed Teich. The council appointed a recruiting commission of three doctors known for their impartiality to say who would be listed for heavy labor. While lighter work could be paid off, and the funds would go to those willing to do the work in their place, hard labor could not be avoided (Teich Reference Teich1958, 236–239). Regardless of social status, wealth, or place of origin, those listed for hard labor had to comply due to the shortage of man power for the tasks assigned. In such cases there were no Bukovinian, Bessarabian, or Ukranian Jews, but stronger men who had to go work for the sake of the weaker community members.

Other important community insitutions were the soup kitchens, which ceased their exclusiveness and provided for the benefit of the needy regardless of place of origin. Filderman wrote to the Jewish ghetto leaders in Transnistria that “the kitchens are to be for the benefit of all who are needy regardless of whether they were born in the Rădăuți, Dorohoi, or Chișinău districts” (Filderman Archive File 45, 163, in Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 254). The Shargorod committee managed to organize the serving of 1,500 people per day and though the soup was far from nutritious, one survivor claimed it was worth the line nonetheless (Peninah Pollack, 03/1220/Peh; Moshe Dor, 93/1908, Yad Vashem, in Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 252). The thousands who could afford food were dependent on trade with the local Ukrainians and used the savvy of local Jews. A family from Suceava wrote they were lucky their landlady did not keep kosher so they could borrow her pots and plates. In what seems to be a sign of pure gratefulness they lamented that they did not have something to give to the landlady’s 5-year-old daughter (Doc. 202, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 997–1001). They found a point of commonality in their degree of assimilation. There were also observant Jews who managed to keep kosher, but more research is required to see how each group helped or hindered the other in Shargorod (Kermish Reference Kermish1986, 417; Baruch Reference Baruch2017). Food was the most important resource and procuring it for the vast amount of ghetto inhabitants meant appealing to fellow deportees of similar origin or breaking regional identity barriers; the two options were not exclusive.

Along with the soup kitchens, the ghetto inhabitants worked together to organize the running of the second and third most important institutions in the ghetto: the hospital and the orphanage. Overcrowding, the lack of nutritious food, and the inability to maintain good hygiene led to dysentery and jaundice, but the most dangerous disease was typhus. The Shargorod ghetto was among the ghettos most affected by the typhus epidemic, along with Bershad and Mogilev, during the winter of 1941 to 1942.

According to historian Jean Ancel, typhus killed 4,000 people in Shargorod. Teich writes of 1,500 victims of typhus, but he may not have included those Jews housed in villages nearby nor did he have the archival evidence that Ancel more recently procured (Ancel Reference Ancel2011, 400, 415; Carp Reference Carp1996, 281; Teich Reference Teich1958, 235). The committee organized a health service department along with a technical department, headed by deportees. The hospital for infectious diseases set up by the committee initially had 25 beds, but in February 1942, a second hospital was opened with 100 beds (Teich, “Excerpt from Monograph Composed for Romanian Social Institute, 15 January 1944,” in Carp Reference Carp1996, 334). Ghetto inhabitants worked together with committee supervision to block up contaminated streams and to fence off wells to avoid water contamination. They set up public toilets, shower and bath houses, and two disinfection ovens. Four hundred people would be disinfected daily. A soap factory was also organized, to manufacture soap for ghetto residents as well as to sell to the local Ukrainian population.

The epidemic died down in April due in large part to the dedicated doctors, all of whom were deportees, and to the aid dispersed by the committee’s sanitation department (Baur Reference Baur2014, 490–491; Carp Reference Carp1996, 282–283; Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 266–267; Teich Reference Teich1958, 234). In Djurin, the ghetto similarly had doctors from Bukovina while in Oglopol there were two local doctors and one doctor from Bessarabia (Korber Reference Korber2009). However, 12 of the 27 doctors in Shargorod died while treating typhus victims. Teich’s son was also among the victims (Teich Reference Teich1958, 232–234). Maria Averbuch, a local of Shargorod, who had 11 deportees join her house of five, described the locals as stronger than the deportees during the epidemic (Maria Averbuch, “We Were in Distress All the Time,” in Zabarko Reference Zabarko2005, 24).

The resilience of the locals and the resources and ingenuity of the deportees allowed for the strategy of containment described above. The ghetto was also divided into regions in May 1942, each region with its own doctor and trained staff. When an epidemic broke out in October, they were ready to deal with it. By 1943 the medicine arrived from the Autonomous Committee of Assistance in Bucharest, allowing the ghetto council to set up a pharmacy to provide medicine free of charge for the needy and at a small price for those who could afford it (Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 267).

The second issue that broke down regional loyalties and ensured survival was the need to care for the increasing number of orphans. A wagon load of salt, sent by the Autonomous Committee in Bucharest, was sold and the proceeds used to establish an orphanage in July 1942. The building housed 152 orphans and another 400 children with only one parent admitted later (Carp Reference Carp1996, 300; Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 260; Teich Reference Teich1958, 244). In the orphanage, the children were provided with food, clothes, schooling, and leisurely activities. Teich recounted the stories of several local Jewish orphans who came to Shargorod: Yosel Blech, Clara Moskal, and Leon Schuster from Kamenets, some from Kyiv, and others from different parts of Transnistria. Some of these children knew only Russian and the ghetto committee helped disguise them as Romanian Jewish children, teaching them critical phrases in Romanian. This way they could be taken to Romania during the early repatriations and would eventually immigrate to Israel (Teich Reference Teich1958, 242–243). Even in some of the most difficult ghettos, like that of Domanevka, the Jewish council sought to help orphans in the Akmechetka camp by sending them part of their meager food supply in October 1942. Some families were willing to take in the 16 of 28 that survived and reached Domanevka (Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 253). The Jews who found themselves in Shargorod in the first few months of ghetto settlement were wary to help the “strange” Jews who were now their neighbors, but it seems this attitude changed or did not apply in the same way to the children. Teich and others went to dangerous lengths to protect refugee orphans from the authorities. Orphans like Moskal and Schuster, who joined the partisans, and those in Shargorod and other ghettos who supported them, defied regional labels. The camaraderie instilled during Soviet years may have helped Transnistria, and Shargorod, in particular, be a place where nationalities were more easily set aside. The leadership seems to have done whatever possible to protect as many as possible in their new community, regardless of regional identity. This was done not only through the institutions described above, but also through cultural initiatives.

Maintaining culture

The development of social and cultural activities provided further means of survival. Shargorod had a history of Jewish observance, associated with the Bal Shem Tov and Hassidism. The sacred place in the synagogue attributed to him was revered and protected by the deportees (Carp Reference Carp1996, 8). The town had four synagogues, including the Great Synagogue, a large stone building built in 1589. These were turned into factories by the Soviet regime, but the Great Synagogue was reopened in the autumn of 1942. Once the typhus epidemic was under control, many in Shargorod returned to ritual observance. On the eve of Yom Kippur in 1942, the Jews gathered together for Kol Nidre, regardless of origin. A deportee from Câmpulung said a prayer in the memory of those who had died in Shargorod in pogroms of old (Weisbuch Reference Weisbuch2007).

Keeping the feast days and Sabbaths as best as they could was a form of resistance against their persecutors’ demonization of Jewish culture, uniting the deportees and the local Jews (Ofer Reference Ofer2014, 387). Wedding, circumcisions, and bar mitzvahs were celebrated, and people met to pray during the week and on the Sabbath. In their letters, deportees mentioned the hope that the first day of Chanukkah brought for them but, unfortunately, did not reveal how they celebrated (Doc. 189, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 893).Footnote 11 Nevertheless, the stories and meaning behind the holidays seems to have given them hope. Due to the lack of nutrition, some recorded how they were permitted not to fast on Yom Kippur (Doc. 208, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 1041). In Peciora, Transnistria, a survivor recalled the entire ghetto gathering to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, but on Yom Kippur there was a roundup of Jews for labor. The authorities tried to break community cohesion by conducting such aktions on holidays or on the Sabbath (R. Leshchinskaya, “These Were the First Living Jews They Met during the War,” in Zabarko Reference Zabarko2005, 162–163, 176; Korber Reference Korber2009).

People nevertheless continued to celebrate. Samuil Roitberg’s father, a local of Mogilev, gathered the ghetto dwellers for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur with the help of a local priest in 1942 (Samuil Roitberg, “It Is Impossible to Dissolve the Whole Period of Living in the Ghetto,” in Zabarko Reference Zabarko2005, 252). In Olgopol, communal prayers were held in two synagogues to accommodate the entire ghetto population in an attempt to remove the authorities’ suspicion of partisan collaboration—presenting themselves as observant Jews and not communists (Phillip Cohen, Yad Vashem interview, in Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 284). The Shargorod ghetto committee organized the repair and reopening of the communal baths, used also for ritual cleansing (Carp Reference Carp1996, 294). The orphaned nephew of Mottel Beinstein, a Shargorod Jewish local, was taken in by the orphanage and celebrated his bar mitzvah (Teich Reference Teich1958, 243). The encouragement offered through religious observance in the ghetto was influential especially for young survivors, many of whom would turn to an observant Jewish faith (Vynokurova Reference Vynokurova2010, 24).

In the larger ghettos of Poland and Germany, more is documented regarding how Jews viewed the holy days; similar hopes and difficulties surrounded Jewish holidays in Shargorod and other Transnistrian ghettos. Jean Améry, an Auschwitz survivor and a self-declared agnostic, argued that faith allowed people to transcend themselves and their reality. Those faithful to their religious traditions were not captives of their individuality—their own needs in the present time—but part of a spiritual continuity (Améry Reference Améry1980, 14). Religious observance in the ghetto was an important part of communal life and of understanding one’s identity as a Jew. It helped maintain a semblance of past joys and of hopes for the future.

Anna Ivankovitser, another local Shargorod survivor, remembered how they celebrated Pesach with a rabbi from Bukovina leading the Haggadah. They made matzah, the only traditional food available due to lack of resources. Anna wrote, “Of course this matzah was far from authentic matzo, but so was our life in the ghetto” (Ivankovitser Reference Ivankovitser2002). Despite working together across religious, cultural, and social barriers, the feeling remained of being forced into an inauthentic living situation by the occupying authorities. This inauthenticity was overcome by those who put all their energies into helping those in need, especially the orphans.

The orphanage was another important place of cultural activity where young people were helped, as mentioned previously, regardless of place of origin. Rosa Levi of Suceava headed the Shargorod orphanage’s activities and was remembered by survivors as a kind woman who created a homelike atmosphere. She ensured the orphans received the best possible healthcare, education, and training for various skills. Children put on plays with themes from their lives in the ghetto. They were taught Jewish history and Hebrew, among other subjects (Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 260; Teich Reference Teich1958, 241). Others like Anna Ivankovitser learned German from the Bukovinan boyfriend she met in the ghetto (Ivankovitser Reference Ivankovitser2002). There was reciprocity among the children in teaching language and sharing games and customs from their hometowns.

Marcu Rozen kept a small notebook from his time in the Shargorod orphanage and in an interview described with fondness the teachers and fellow orphans (Rozen Reference Rozen2004, 11). Children shared similar sufferings as well as hopes; it was in the orphanage that some made their first friends during the war. As the typhus epidemic had been indiscriminate with the parents of these children, those who survived the epidemic in the spring of 1942 also could not discriminate against the needy children.

Shargorod ghetto included Zionist activists, some of them from among the older orphans, who helped unite many in the ghetto under the common banner of emigration to Israel. Zionist youth secretly published a newspaper and were dedicated to educating the ghetto orphans. Similarly, in the Djurin ghetto, young people distributed a newspaper entitled Courier for a short time in 1943. In it were songs or poems that revealed the mix of Jews in the ghetto as well as articles describing social problems that arose from such a mix. One author claimed the ghetto was not a real community but a fictitious one (Litani Reference Litani1963, 40–43; M. Sherff, “The Youth Movement in Shargorod,” Masuah 4 [April 1976]: 212–214, quoted in Dobroszycki and Gurock Reference Dobroszycki and Gurock1993, 147–148). People hoped the situation would be temporary, and as repatriations to Romania began in 1943, they knew their living situation would change.

The inevitable disagreements regarding religious observance, schooling, youth movements, and other cultural activities due to different backgrounds as well as to fear of the authorities were nevertheless largely overcome in Shargorod due to the ghetto residents’ dedication to working together to survive. By rallying around the orphans and participating communally in various religious and cultural activities, they reinterpreted their entangled notions of belonging and used regional particularities and advantages for the benefit of all.

Authorities stated that 240 Bessarabian Jews and 2,731 Bukovinian Jews were alive in Shargorod in 1943, while Teich surmised a survival rate of 70–80% (Carp Reference Carp1996, 207, 334, 457; Teich Reference Teich1958, 251). The exact number is disputed due to inadequate documentation by Romanian wartime authorities and the movement of Jewish deportee groups through the ghetto at different times during the war. Nevertheless, the institutions described in this article were crucial to the survival of Shargorod’s remaining Jewish population at the end of the war.

Conclusion

The Shargorod ghetto was different from surrounding Transnistrian ghettos and from other ghettos in the west. Ghetto leaders were on better terms with the Romanian officials, whom they bribed; they also received more help from the local Ukrainian population, especially the local women whose husbands had been drafted into the Soviet army. The deportees managed to smuggle the Suceava Jewish community’s funds into the ghetto. This not only protected the Suceava Jews, but also allowed for the development of the institutions that came to benefit the entire ghetto community. The soap factory, school, and orphanage were well organized and interregional. Good relations with the local population and the reciprocal support of ghetto inhabitants and partisans also provided protection (Baur Reference Baur2014, 491). These could all be seen as a result of strong cooperation among Jews in the ghetto despite various origins.

Bessarabian survivor Avigdor Shachan claimed that the problem of deportees isolating themselves into communities of origin did not last long (Shachan Reference Shachan1996, 254). However, it lasted long enough to make Wilhelm Filderman address the situation in 1943 when the Autonomous Committee of Assistance in Bucharest began sending aid (Ancel Reference Ancel1986, vol. V, 390, 498). Shargorod Jews tried to overcome this dangerous tendency, and their leader Meier Teich received a more positive portrayal in postwar accounts than the Zmerinka ghetto’s Herschmann or even Mogilev’s Jagendorf.

Their ultimate appropriation of regional identity allowed for better cooperation and assistance among the diverse ghetto population. Those who put regional identity first faced grave moral questions, but they nevertheless benefitted from the inclusive institutions set up by the ghetto council. When struggling for survival, all inevitably faced difficult moral decisions, but how one identified themselves in such situations affected their course of action and how they were remembered. The difficult situation of the Jews in the Shargorod ghetto forced them to re-appropriate and reinterpret their traditions and beliefs—the foundations of their identity—and thereby strengthen it. Assimilated and observant Jews reassessed what it meant to be Jewish and, though no new universal definition was proposed, they came to better understand what the Torah meant by the commandment to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18). At this time, the majority of Romanians, who claimed to be devout Orthodox Christians, seem to have forgotten the teaching of Jesus on this commandment in the Gospel of Mark 12:30–31.

The Romanian officials attempted to place a new identity on the Jewish deportees and locals: they were now Transnistrians, with no ties to Romania, Ukraine, or the Soviet Union (Doc. 40, Grilj et al Reference Grilj, Osatschuk and Zhmundyljak2013, 204–210). This identity never held ground and was rejected as people hoped to return to their hometowns or considered themselves simply, or not so simply, Jews. Romanian Jewish identity, as well as that of Ukrainian Jews, took different forms and varied from individual to individual—from complete assimilationists to Hassidim. In the Shargorod ghetto, when forced into survival mode by an all-inclusive Jewish identity imposed from above, one which some initially resisted, the deportees and local Jews achieved an admirable level of solidarity. Spurred by their common human identity (refused to them by Nazi-allied governments) they strove for survival across political, economic, religious, and cultural lines.