Research

The archaeological site of ‘Marea’/Philoxenite is in northern Egypt, on the southern shore of Lake Mareotis, 40km south-west of Alexandria (Figure 1). The town developed with the growth of the pilgrimage centre at Abu Mena, located 17km to the south. Under Emperor Justinian (reigned AD 527–565), it became one of the most important pilgrimage sites of the empire, attracting visitors from across the Roman world, for whom the most convenient route was by sea to the port of Alexandria, and then via the lake to Philoxenite, before completing the final stage either on foot or riding on an animal.

Figure 1. Map of the Mareotis region (figure by J. Kaniszewski & M. Gwiazda).

Church N1 was situated on the outskirts of the town, approximately 250m from the main public square (Figure 2). The structure, originally L-shaped (9.60 × 27.23m), underwent several phases of construction (Figure 3: phase I). Excavations indicate that the site first underwent substantial earthworks, levelling the area and covering it with a thick layer of clay that contained broken pottery. Only after this was the foundation for the church built. Notably, the foundations were raised with free access around them during the time of construction, rather than being constructed in pits. While this method was time-consuming, it allowed for a more precise fit of the stones. The foundations consisted of well-worked ashlar limestone blocks (Figure 4a), with the upper level featuring a slight offset, showing mortar traces. On the exterior, beginning at the foundation level, semi-rounded buttresses (Figure 4b) supported the wall corners (‘angled buttresses’).

Figure 2. Orthophotogrametric image of the remains of Church N1 with inset location (figure by M. Gwiazda & P. Zakrzewski).

Figure 3. N1 plan with construction phases (figure by A.B. Kutiak & P. Zakrzewski).

Figure 4. Architectural design of Church N1 and related features: a) wall facing with foundation level documented in the baptistery (Room 4); b) angled buttress in the southern part of the building; c) southern anta and threshold between Room 1 and 2; d) fragment of marble slab on a socket made in the floor pavement (Room 1); e) construction of the stylobate; f) anastilosis of the pseudo-column (Room 5) (photographs by M. Gwiazda & P. Zakrzewski).

The church superstructure was constructed in a manner similar to the foundations. The limestone blocks used in the walls were mostly uniform. The mortar binding the stones, as well as the plaster applied to both the interior and exterior walls, consisted of lime, sand and gravel, sometimes mixed with burnt organic material. The floors, laid before plastering, were primarily stone pavement, with selected areas featuring inlaid patterns (opus sectile). Most slabs were oriented along the east–west axis; however, in Room 1, they were rotated 90°, which may indicate its distinctiveness.

The initial layout of the church comprised four rooms (Figure 3, nos. 1–4). Room 1 served as a narthex, or more precisely an esonarthex (inner narthex), as it was not the main entrance but was accessible only from the nave. This type of church space was typically accompanied by an exonarthex, located at the main entrance, usually sheltered by a portico (Grossmann Reference Grossmann2002: 101–102). Its separation from the nave is emphasised by antae (two side piers) in the passageway and a threshold, both bearing traces of door or screen fittings (Figure 4c).

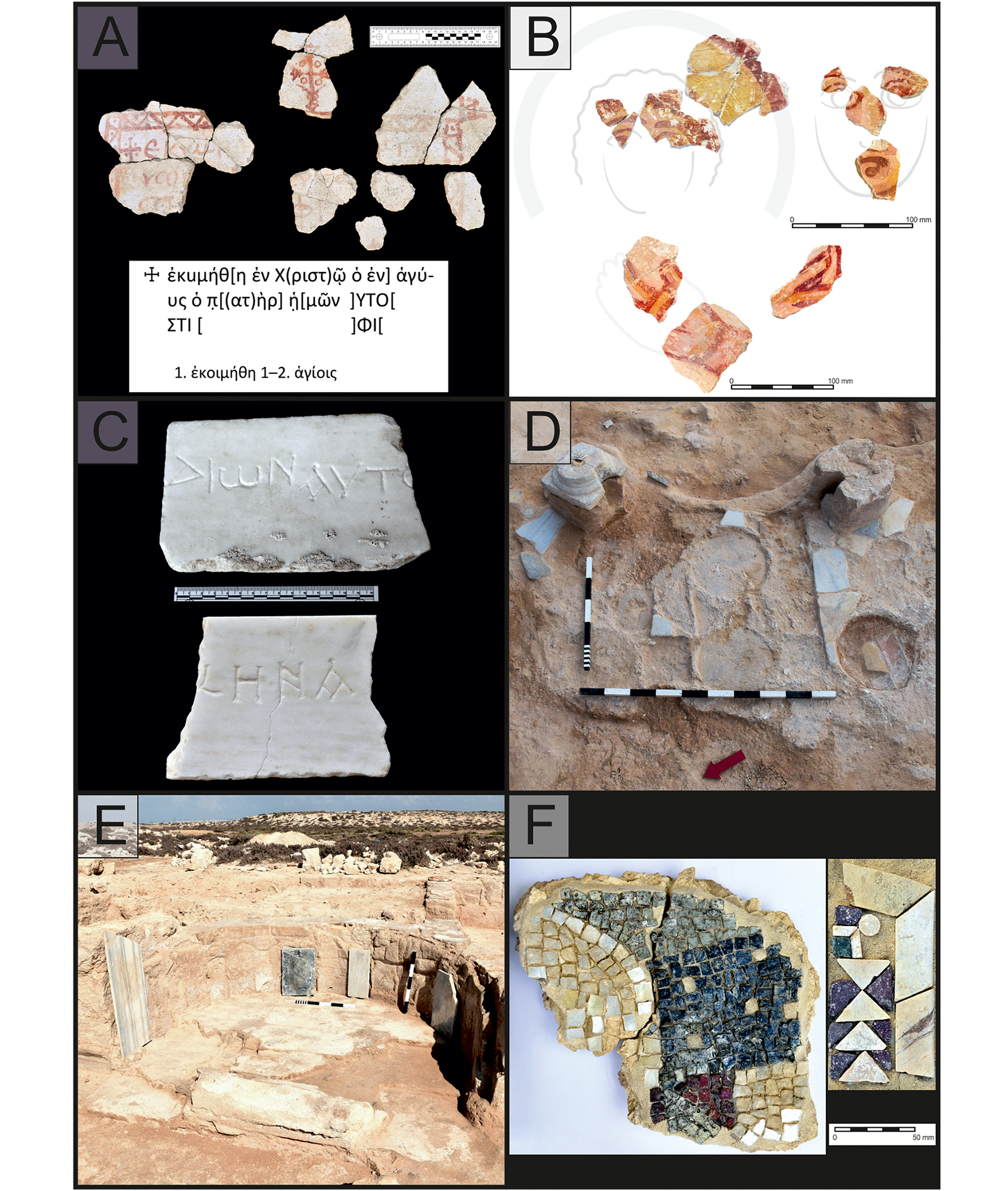

Room 1 also featured wall decoration. Excavations in the southern part of the room revealed a figural depiction of a woman (Figure 5b), the halo and orans pose probably indicating a saint (Gwiazda et al. Reference Gwiazda, Derda and Barański2022), fragments of a painted Greek funerary inscription (Figure 5a) also suggest the presence of a grave, although no such grave was actually discovered here. The sculpture of a lion or lioness, found reused in the neighbouring Room 7, suggests that the female figure could be Saint Thecla, who is directly associated with the cult of Saint Menas (Wipszycka Reference Wipszycka, Connor, Dijkstra and Hoogendijk2024). Two marble plaques were also discovered, one of which bears the name of Menas (Figure 5c). On the opposite side of the esonarthex, a marble slab was set into a socket carved in the floor pavement (Figure 4d), possibly marking a relic repository. However, despite careful exploration, no evidence was found to support this hypothesis.

Figure 5. Examples of decorative elements: a) fragments of painted Greek inscription (Room 1), which translate as: ‘fell asleep in Christ our father, who is among the saints, [name]’; b) fragments of painted figural depiction (Room 1); c) two inscribed marble plaques; d) imprints and in situ fragments of opus sectile floor decoration in the baptistery (Room 4); e) hypothetical reconstruction of the apse decoration; f) fragments of opus tesselatum and opus sectile mosaics (photographs by J. Burdajewicz, T. Derda, M. Gwiazda & P. Zakrzewski).

The remaining rooms include the nave (Room 2), which ends with a presbytery and an apse, a pastophorium (Room 3) and a baptistery (Room 4). The absence of stone paving and the presence of numerous smaller imprints in the pastophorium suggest its floor was entirely covered with marble slabs. A similar, but slightly more elaborate, floor decoration was also found in the baptistery (Figure 5d).

The church had multiple entrances, two of which (I and II, 1.34 and 1.02m wide, respectively) led from the south into the nave. Two more entrances (III and IV, 1.28 and 1.01m wide, respectively) provided access to the baptistery, while an additional entrance, differing from the others by having a high threshold, led to the nave from the north (V, 1.07m wide). In later phases, three of these openings (III–V) were blocked as part of the building’s development, while two others (VI and VII) were added.

During the second construction phase, likely soon after the church’s initial erection, large, partially worked stones were placed in a deep foundation trench, forming the stylobate of a colonnaded portico (Figure 4e). A column shaft and the base of another were both discovered in situ. The intercolumniation measured approximately 3.09m. Repeating this measurement permits three additional columns, with the last aligning precisely with the church’s western wall. At the opposite end of the portico, a semi-open space was created, featuring pseudo-columns resting atop a wall on its southern side (Figure 4f).

Phase III marks a significant reconstruction of the southern part of the building. The western section of the colonnade was built over with two rooms (6 and 7), while Room 5 was closed off. These additions, constructed from smaller stones and reused materials, were of noticeably lower craftsmanship. By this time, the church was likely part of a larger complex with a central courtyard and a well.

Before abandonment, and immediately after ceasing its original function, most decorative elements were carefully removed. Some were deposited in a walled-up storage space discovered in the southern part of the baptistery, including mosaics in the opus sectile and tessellatum techniques, reflecting the high level of decoration (Figure 5e & f).

Discussion

Unlike some of the buildings in Philoxenite, Church N1 does not impress with its size, but stands out for its high-quality construction, especially in its first phase. Its ashlar construction appears characteristic of buildings in the northern part of the city, while in the southern part, Church N1 stands apart from the surrounding structures (Kutiak in press). This may suggest ashlar construction was employed in Philoxenite’s early development when its builders were not facing financial difficulties. Thus, Church N1 was likely built in this phase, slightly apart from contemporary structures, possibly as an extra-urban church and its free-standing location along the road leading pilgrims to Abu Mena was not accidental.

Without constraints from existing buildings, the church was built as a compact rectangular structure with a southern portico. In the first phase, likely carried out in the second half of the sixth century AD, a structure in the shape of an inverted L was created, with the baptistery extending to the south. Shortly after, a portico was added, enclosing the rectangular structure.

During Heraclius’s reign (phase III, indicated by a coin—Heraclius, 12-nummi, Alexandria mint, 613–618 AD, Obv.: to left bust of Heraclius, to right bust of Heraclius Constantine, Rev.: denomination mark-IB, cross on steps—found beneath entrance VII’s threshold), the church was integrated into a larger, yet unidentified, complex. It transitioned from a roadside sacred building into what was possibly a monastery or pilgrims’ hostel. This transformation resembles that of a large private house in the western part of the town, although the church there did not exist initially and was established by converting the southern wing of the house (Derda et al. Reference Derda, Gwiazda and Burdajewicz2023).

Funding statement

The Polish National Science Centre (grant 2023/49/B/HS3/00135) financed this project.