1. Introduction

As an important aspect of economic growth and social well-being, living standards have always been a significant topic in economic history. Both real wages and probate inventories have been used widely to measure living standards in the early modern period. Real wages are calculated by dividing monetary wages by the cost of living, with the basic premise that the purchasing power of monetary wages reflects living standards.Footnote 1 Probate inventories, on the other hand, record goods owned by individuals and their values, providing evidence of household production and consumption. The value of household goods has also been used to measure material standards of living.Footnote 2 However, since wage data are collected from various account books and inventories were recorded after the testators died, these two source types offer only an incomplete picture of wage-earners’ lives during a specific period of their life cycle.

This article explores the living standards of wage-workers using three types of sources: a sample of Lancashire probate inventories made by people with wage-earning occupations; the wage accounts of the Shuttleworths, a Lancashire gentry family, from 1582 to 1621; and wills and inventories made by the Shuttleworth employees. These are used to compare the Shuttleworth employees’ inventories with those made by other Lancashire people with the occupation ‘labourer’, and the wage-earnings of the Shuttleworth employees with the material wealth values of their inventories.Footnote 3 Combining these sources can help us move beyond the snapshots provided by traditional economic analysis and incorporate life-cycle changes into the study of living standards.

While Lancashire has long been known as a poor and conservative county in early modern England, it witnessed some major changes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 4 The population of Lancashire increased from 82,371 in 1563 to 141,641 in 1664, although the demographic growth was uneven across the county.Footnote 5 In contrast to the situation in South-East England, family farms dominated in the North-West at least until the later eighteenth century.Footnote 6 In addition, the conversion of common fields and wastes into enclosed fields and subdivision of landholdings during the Tudor and Stuart periods offered a multitude of smallholdings for Lancashire inhabitants.Footnote 7 Even if these small landholdings were insufficient to support a family without other sources of income, they remained widespread and available to many people in Lancashire. This enabled wage-earning to be combined with access to land, unlike many areas of Southern England.

The household and farm accounts of the Shuttleworths of Smithills and Gawthorpe Hall have been well known to historians since the publication of excerpts by John Harland in the mid-nineteenth century. However, the full record provided by the original manuscript documents has rarely been consulted.Footnote 8 As the accounts were recorded during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, a period identified as one of economic crisis, and few similarly detailed records are available for other countries, they provide a unique window into the lives of rural wage-workers during this difficult time.Footnote 9

This study is unique in connecting two stages of some real rural wage-earners’ life experiences, to contribute to the current debate on living standards. On the one hand, it shows that consulting only inventories left by people with the occupation ‘labourer’ underestimates the living standards of some early modern wage-earners; on the other, relying solely on real wages overestimates the significance of money wages in changing living standards. As not all early modern rural wage-earners were landless people, tracking their changing living standards during the life cycle, and distinguishing the extent of reliance on monetary wages among different groups of wage-workers, is essential.

After Section 2 presents an overview of current research on living standards, Section 3 introduces the landholdings of the Shuttleworths between 1582 and 1621 and their employment of wage-workers. Section 4 discusses the data and methodology. It introduces the inventories left by 169 Lancashire labourers, building craftsmen and servants between 1550 and 1650, and outlines the methodologies adopted to identify inventories left by 51 wage-workers hired by the Shuttleworths during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote 10 Focusing on household production and consumption, Sections 5 and 6 compare the percentages of items recorded in inventories left by the Shuttleworth employees and other Lancashire wage-workers. The findings show that relying solely on the inventories of those with the occupation ‘labourer’ underestimates real wage-earners’ (those recorded in the accounts) diverse sources of income and material living standards. Section 7 turns to life-cycle changes in living standards by comparing wage levels with the material wealth values of inventories, and exploring the impact of different family structures. This suggests that, while the significance of money wages varied among different groups of wage-workers and at different stages of their lives, more attention should be paid to other factors such as household formation and access to land. Current reliance on either inventories or real wages oversimplifies the picture, ignoring some workers’ abilities to live more prosperous lives later in their life cycles. In fact, both the diverse backgrounds of wage-earners and the endeavours made by them and their families to survive need to be examined carefully.

2. Real wages and inventoried goods in measuring living standards

In the nineteenth century, James Thorold Rogers used statistics about wages and prices to argue that the fifteenth century was the ‘Golden Age’ of farm labourers, and since then economic historians have used the same approach to analyse living standards.Footnote 11 Real wages are valuable for explaining long-term economic changes, but the data used have some serious drawbacks.Footnote 12

When measuring the cost of living, scholars tend to use various budgets, or different ‘baskets of consumables’. The basket of consumables is composed of different items, such as food, clothing and fuel, and the cost of living fluctuates as the prices of these items change over time. While Robert Allen’s baskets of consumables have been widely used, his main sources of prices were collected from the work of Thorold Rogers and William Beveridge, which were mainly taken from Southern England.Footnote 13 In fact, scholars have questioned the representativeness of fixed compositions within the baskets.Footnote 14 In addition to variations in consumables, scholars also employ different proxies for assessing wage-earners’ nutritional needs. The ‘respectability budget’ and the ‘bare bones subsistence budget’ constructed by Allen, for example, provide a male adult worker with 2,500 and 2,100 calories per day, respectively, while Donald Woodward’s budget allows for 2,850 calories per day.Footnote 15 Since the diet varied regionally and employees received cash wages with or without food and drink during employment, as discussed in Section 7, assuming a uniform proxy for wage-workers’ cost of living across the whole nation is problematic.

Current analysis of wage data is problematic as well. Scholars adopt different methods to analyse daily wage rates of single occupations, collected either from Southern England or from urban areas. Concentrating on the wage data of male building workers, for instance, E. H. Phelps Brown and S. V. Hopkins collected data from Southern England, whereas Donald Woodward selected a range of daily wage rates to construct wage series for Northern urban building workers.Footnote 16 Although Gregory Clark collected builders’ wages from five regions, he used urban data to construct national wage series.Footnote 17 In addition to the omission of wage data from rural Northern England, the impact of adopting different methods of using wage rates to calculate real wages is often overlooked, leading to varying conclusions about economic changes.Footnote 18

Attention has also been paid to unskilled English wage-workers. Clark used both day-wage rates and threshing piece-rate payments to calculate average day-wage rates of agricultural labourers. However, he excluded servants in husbandry, an important part of the agricultural labour force, owing to uncertainty about in-kind payments.Footnote 19 This research gap was addressed by Jane Humphries and Jacob Weisdorf, who investigated male servants’ wages and agricultural workers’ living standards by creating an annual income series.Footnote 20 This was the first time that male servants had been discussed systematically alongside unskilled male day workers, although the authors did not track the actual working days per year undertaken by individual workers.Footnote 21 Humphries and Weisdorf also offered the first long-term studies of unskilled women’s wage rates.Footnote 22 However, their analysis of non-harvest wages of female workers has been questioned recently by Jane Whittle and Li Jiang, whose findings show that women’s work was not only highly seasonal but also concentrated in three types of task: weeding, haymaking and harvesting grain.Footnote 23

When calculating the annual wage income, apart from some scattered evidence concerning the actual number of working days per year, current discussion of days worked per year focuses on either comparisons with servants’ annual wages or estimations of fixed working days per year, such as 250–260 days per year.Footnote 24 Stephen Broadberry et al. presented an alternative output-based estimation, arguing that increasing labour input over time could reconcile the divergence between real day-wage rates and output-based measures of gross domestic product per head, but their argument lacks robust empirical support.Footnote 25 Here we argue that factors such as the availability of employment opportunities and access to land influenced the number of days labourers worked for wages per year, and thus the actual number of days worked and how this changed over time need to be examined carefully.

The income contribution made by wives and children has been gradually recognized in recent research, and attention has been paid to the economic value of their wage labour.Footnote 26 Humphries, Weisdorf and Sara Horrell, for example, have taken life-cycle conditions and family structures into consideration to discuss the living standards of family units.Footnote 27 However, as their work is built on previous studies of single wage-workers’ wage series, some fundamental issues related to the wage series still need to be addressed. Recently, in agreement with this article, Joyce Burnette explored family living standards by including the non-market production for household use in the nineteenth century, concluding that using real male wages alone fails to measure the real standards of living.Footnote 28

Long-term real wage series provide a broad perspective on economic growth, allowing for historical analysis from a global viewpoint. However, since early modern wage-earners were not the same as modern full-time wage-workers, the estimated purchasing power of money wages offers only a proxy of real living standards and needs to be thoroughly interrogated with other approaches, such as that set out here. In fact, the production items, occupations and social status recorded in probate records indicate that some early modern rural wage-workers had diverse sources of income, as discussed in Section 5.

Probate inventories are another valuable source used to assess living standards, although they are more commonly discussed in the context of household production and consumption in early modern England.Footnote 29 Since Alan Everitt’s analysis of ‘farm labourers’, inventories left by labourers have been widely used in larger samples, although they typically account for less than 5 per cent of the total.Footnote 30 Lorna Weatherill, for example, used 28 labourers’ inventories out of 2,902 inventories taken from 8 parts of England in her study of consumer behaviour between 1675 and 1725.Footnote 31 Mark Overton et al. examined 8,098 inventories collected from Kent and Cornwall between 1600 and 1750, of which only 129 were labourers’ inventories.Footnote 32 In their recent research on the consumer revolution, Joanne Sear and Ken Sneath collected 7,440 inventories spanning 1551 to 1800, 353 of which were left by labourers.Footnote 33 While investigating rural by-employment in early eighteenth-century Cheshire and Lancashire, Sebastian A. J. Keibek and Leigh Shaw-Taylor used 25 labourers’ inventories, out of a sample of 543.Footnote 34 The only study to focus on agricultural labourers alone, by Craig Muldrew, used the largest sample of labourers’ inventories, 972 collected from 6 counties between 1550 and 1800, to analyse their household goods over time.Footnote 35 However, none of these studies have attempted to link inventories to wage accounts to explore the background of these inventories.

When measuring the material living standards of agricultural labourers with inventories, a key question arises: who qualifies as a ‘labourer’? Scholars have used different methods to identify labourers. The term ‘peasant labourers’ used by Everitt included ‘those workers whose livelihood was based partly on their holdings and who were wealthy enough to leave inventories’.Footnote 36 In his selection of approximately 300 labourers’ inventories, Everitt used different thresholds of inventoried wealth to identify labourers: under £5 before 1570, under £10 in the 1590s and under £15 during 1610–1640.Footnote 37 Despite noting lower monetary values in the North-West and fewer labourers there, Everitt did not strictly apply these criteria to that region. Instead, he excluded ‘some inventories of small value [that] evidently belonged to retired yeomen or others living with their family’.Footnote 38 More recently, using the occupational label ‘labourer’ recorded in inventories has been preferred as a means to select inventory samples.Footnote 39 To examine the representativeness of these inventories in terms of comparative wealth, Muldrew matched inventories left by labourers with hearth-tax entries for Cambridgeshire, Hampshire and Kent between 1664 and 1678.Footnote 40

However, both methods have their limitations. Owing to the wealth bias inherent in inventories, it is plausible that some labourers who primarily worked as wage-earners throughout their lives may have been too poor to leave inventories. It is also possible that some labourers either did not have occupations recorded in their inventories or were labelled with other occupations.Footnote 41 As working for wages was often still a life-cycle phase during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the representativeness of inventories left by labourers whose occupations were documented at death needs to be examined carefully.

In fact, some scholars have delved into the intricate household economies of early modern English wage-earners by integrating household accounts with other original documents. For instance, A. Hassell Smith examined the profiles of the labouring families in Stiffkey, a parish of Norfolk, between 1587 and 1598, and concluded that they opted for a ‘multi-faceted means of subsistence’ owing to the irregular employment opportunities.Footnote 42 While discussing the relationship between wealthy gentry landlords, the Le Stranges, and the local community at Hunstanton, Norfolk, Jane Whittle and Elizabeth Griffiths identified the diverse backgrounds of wage-earners including six tenant families, a lesser gentry family, two yeomen, a labourer and husbandman, a poorer labourer and smallholder, and a thatcher and smallholder.Footnote 43 This research is inspired by these approaches that cross-reference local documents and aims to provide the first systematic analysis of life-cycle changes in the living standards of individual wage-workers by using both household accounts and probate inventories.

3. The Shuttleworths and their employees, 1582–1621

The Shuttleworth family has a long history dating back to the thirteenth century.Footnote 44 In the period 1550–1650, the three sons of Hugh Shuttleworth, Sir Richard Shuttleworth, Lawrence Shuttleworth and Thomas Shuttleworth, as well as the eldest son of Thomas Shuttleworth, Col. Richard Shuttleworth, inherited and operated the family’s estate between September 1582 and October 1621, when the Shuttleworth household accounts were written. Currently, nine volumes of these accounts are preserved at the Lancashire Record Office (LRO), although three of the original volumes are missing.Footnote 45

The accounts record in detail the activities associated with two different estates in Lancashire: Smithills near Bolton in 1582–1599 and Gawthorpe near Padiham and Burnley in 1600–1621. Compared to the ancestral property of Gawthorpe, which was inherited by Sir Richard Shuttleworth in 1596 and covered only 170.5 statute acres, the estate of Smithills was more extensive. It comprised two parts: Smithills Hall and its demesne lands totalling 1,096 statute acres; and three other manors ranging in size from 100 to 300 acres, with demesne lands and tenants. These manors were located at Lostock, Tingreave (Eccleston) and Much Hoole.Footnote 46 Smithills and Lostock were situated in the northwest of Salford hundred, while Tingreave and Much Hoole were located in the middle and the northwest of Leyland hundred, respectively. Sir Richard Shuttleworth acquired temporary ownership of the Smithills estate through his marriage to Margery, the youngest daughter of Sir Peter Legh of Lyme, Cheshire, and of Haydock and Bradley, Lancashire. As the Smithills estate originally belonged to the Barton family, after years of lawsuits, Sir Richard Shuttleworth agreed that the estate would revert to the Bartons upon his death. Thus, the Shuttleworths held ownership of this estate only from 1582 to 1599.Footnote 47

Nevertheless, other land transfers meant that the quantity of land owned by this family varied widely over time. When the Shuttleworths acquired the lease of Ightenhill Manor Park in 1580, for example, they owned most of the land in the Padiham, Simonstone, Higham, Ightenhill and Habergham area, which allowed them to become one of the most influential gentry families in the locality.Footnote 48 During the period when the Shuttleworth accounts were recorded, the family also purchased land elsewhere in Lancashire and Yorkshire.Footnote 49

Although the missing and faded sections as well as unnamed workers make it difficult to track every employee from 1582 to 1621, the number of wage-earners hired during some specific periods can be calculated. Generally, this gentry household had a clear record of employing more male than female workers. For example, while the total number of female servants was 75 in 1582–1606 and 1616–1621, that of male servants was 160.Footnote 50 However, between 1600 and 1606, the construction of Gawthorpe Hall attracted a large workforce, including at least 206 male building workers. During this period, the demand for female agricultural labourers increased dramatically. For instance, in 1605 the number of female harvesters peaked at 33, equalling the number of male harvesters employed that year.Footnote 51

Regarding wage levels, although they were influenced by diverse factors such as gender, age and skills, some general features can be summarized here. Generally, Shuttleworth employees received lower daily wage rates than their Southern counterparts.Footnote 52 For example, while the Shuttleworths paid their labourers less than 3 pence (d.) per day with food and drink provided for hedging and ditching between 1615 and 1621, the Le Stranges in Norfolk paid 6d. per day for the same tasks during the same period.Footnote 53 While the yearly money wage received by best-paid male servants increased from £2 16 shillings 8 pence (£2 16s. 8d.) in the 1580s to £4 in the 1620s, daily wage rates received either by agricultural labourers or by builders overlapped and did not change too much during the same period.Footnote 54 As most Shuttleworth employees were fed during their employment, combined with their relatively stable cash wages, it appears that the monetary inflation had very limited impact on Shuttleworth employees’ money earnings.Footnote 55

4. Data and methodology

The data used in this article are composed of three parts: inventories left by 169 Lancashire wage-workers between 1550 and 1650; identified wills and inventories left by 51 employees who once worked for the Shuttleworths from 1582 to 1621; and the wage records from the original Shuttleworth accounts.

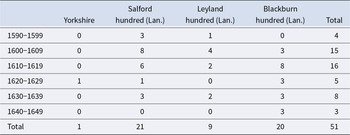

Table 1 presents the distribution of 169 inventories left by Lancashire labourers, building craftsmen and servants, whose occupations were recorded in probates between 1550 and 1650. To make the data comparable with Shuttleworth employees’ inventories, six types of craftsman – carpenter, mason, joiner, waller, plasterer and wright – were included when collecting inventories. Appendix 1 lists the number of inventories left by these craftsmen. Labourers and building craftsmen came from the area between the north of the River Mersey and the south of the River Ribble, where the Shuttleworths owned farmland in Lancashire from 1582 to 1621. However, the servants came from a broader range of locations, including Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cumberland and Westmorland. As the sample of servants is limited, this diversity has minimal impact on the subsequent comparison.

Table 1. Decadal number of probates left by Lancashire labourers, building craftsmen and servants, 1550–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, Lancashire Record Office, UK (hereafter LRO).

a Note: Building craftsmen include carpenter, mason, joiner, plasterer, waller and wright.

Tables 2 and 3 present the distribution of 51 Shuttleworth employees’ probates by decade and by the occupation or social status of these employees. Most of them came from the Salford and Blackburn hundreds of Lancashire, where the Shuttleworths lived during the research period. Although both male and female employees were tracked, no women’s inventories were found. As wives’ belongings were normally represented in their husbands’ inventories, it is possible that many female wage-earners did not leave inventories. Although not every wage-worker had a clear occupation or status recorded in their probates, the sample shows that more than half of the 51 Shuttleworth employees were husbandmen and yeomen.

Table 2. Decadal distribution of the Shuttleworth employees’ probates, 1590–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

Table 3. Occupation/social status of the Shuttleworth employees

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

To track inventories left by Shuttleworth employees, more than 1,000 full names were collected from the original accounts. Owing to variations in spelling, family names were clarified using the index of names published by John Harland and the parish registers of Bolton, Padiham and Burnley.Footnote 56 These employees’ names were then compared with indexes of Lancashire wills and inventories left between 1545 and 1650, and the LRO online catalogue.Footnote 57 Some wage-workers with distinctive surnames could be easily identified this way. For instance, John Baxsenden, a waller employed by the Shuttleworths for building Gawthorpe Hall, worked 43.5 days between August and October 1600. He was identified as the same person whose occupation was recorded as ‘rough waller’ in a will of 28 July 1614.Footnote 58

In addition to this simple comparison, both the Shuttleworth accounts and the inventories provide solid evidence for further identification. Firstly, the recorded locations of employees’ residence in the accounts can be used to track their inventories. John Prescot, for example, a labourer from Eccleston who did diverse tasks for the Shuttleworths between 1591 and 1594, such as ‘leading hay and corn’, threshing and thatching, was assumed to be the same person who left an inventory at Heskin, Eccleston, in 1616.Footnote 59 Secondly, occupations recorded in inventories can help distinguish individuals with common names. Richard Ryley, for example, a mason hired for building Gawthorpe Hall, was assumed to be the same man, Richard Ryley, whose occupation was listed as ‘freemason’ in his will of 1619.Footnote 60 Thirdly, recorded debts provide valuable information as well. For example, Ryley’s will recorded a debt of £5 owed by Richard Shuttleworth to the testator for unpaid walling.Footnote 61

To ensure data accuracy, certain steps were taken to process the samples that remained unmatched. After excluding inventories that could match more than one possible employee, reasonable estimations were made according to details found in both the accounts and the inventories. For instance, when wage-earners worked as both servants and labourers for the Shuttleworths, and when wives of wage-workers also did agricultural tasks for this gentry family, it was assumed that these workers were likely local or nearby residents. In addition, some Shuttleworth employees were assumed to reside close to the named farmlands if they received task payments and/or day wages ‘on their own tables’.

Lastly, recent research has identified several wage-workers employed by the Shuttleworths, providing further insights into their inventories. For example, Anthony Whythead, the principal mason who supervised the building of Gawthorpe Hall, later worked on Haigh Hall near Wigan and died at Emmott near Colne in January 1607–1608.Footnote 62 Whythead worked for the Shuttleworths from March 1600 to June 1603, when he received 30s. per quarter and was recorded as both ‘mason’ and ‘servant’ in the accounts.

The wealth bias of inventories mentioned in Section 2 means that it is possible that these 51 employees were wealthier than their colleagues who did not leave inventories. Nevertheless, as the inventory sample used in this article was left by identified early modern employees, the recorded information still provides firm and unique evidence for exploring a group of rural wage-workers’ changing living standards.

5. Household economies

Production goods recorded in inventories reflect how early modern wage-workers and their families made a living with diverse forms of activity. Inventories left by 93 building craftsmen, 54 labourers, 8 servants and 48 Shuttleworth employees were sufficiently detailed and complete to allow three types of production activity – arable farming, pastoral farming and textile production – to be explored. Comparisons drawn from these activities show that Shuttleworth wage-workers had higher participation in farming and textile production than men described as ‘labourers’ in their inventories in early modern rural England.

5.1 Arable farming

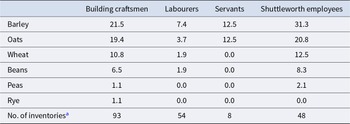

Both arable crops and agricultural tools listed in inventories indicate the involvement of arable farming. Since inventories were made year-round, it is common to find crops at various stages of growth.Footnote 63 Sometimes, the locations of these crops, such as in the ground, the house and the barn, were listed as well. Table 4 presents the percentage of 203 inventories that recorded arable crops among different types of wage-workers between 1550 and 1650.

Table 4. Percentage of inventories recording arable crops, 1550–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

a Note: The number of inventories used here is less as some testators left only wills.

Generally, Shuttleworth employees’ inventories had higher percentages of arable crops than other groups of workers. While the percentages of building craftsmen who owned oats, wheat and beans were slightly less than those of the Shuttleworth employees who did so, there is a notable difference in the percentage of barley ownership, at 21.5 per cent and 31.3 per cent, respectively. Nevertheless, the gap between labourers and Shuttleworth employees is bigger: while barley was the most commonly recorded arable crop among labourers, found in 7.4 per cent of inventories, it was still less than the percentage of Shuttleworth employees who owned beans (8.3 per cent). John Postlethwait of Kirkby Ireleth was the only servant in the sample whose inventory recorded oats and barley between 1550 and 1650. His inventory on 12 August 1616 detailed six bushels of oats and six pecks of barley, valued at 16s. and 6s., respectively.Footnote 64

While some inventories did not list arable crops, other terms indicate related goods. Firstly, it is common to find ‘corn’ used in inventories. In February 1632–1633, Henry Amond, a carpenter of Clubmere, West Derby, left ‘corn of all sorts’ valued at £3.Footnote 65 Sometimes, ‘corn’ was recorded together with other items. The inventory of James Smith, for example, a servant of Droylesden, Manchester, recorded ‘corne and haye’ valued at £9 on 8 August 1587.Footnote 66 In addition, milled or ground grain, recorded as either ‘groat’ or ‘meal/oat meal’, appeared in inventories as well. While 29.6 per cent of labourers left ground grain in their inventories, the proportions for building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees were higher, at 36.6 per cent and 45.8 per cent, respectively.

The ownership of agricultural or outdoor tools such as ploughs, harrows, scythes and sickles also indicates involvement in arable farming. While James Smith was the only servant whose inventory recorded tools (a harrow), the proportions of building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees who owned agricultural tools were high, at 61.3 per cent and 68.8 per cent, respectively. In contrast, only 29.6 per cent of labourers’ inventories listed agricultural tools, although it is possible that these labourers borrowed or shared tools with others.

5.2 Pastoral farming

Compared with arable farming, pastoral farming played a more dominant role in Lancashire. Table 5 presents the percentages of 195 inventories recording livestock among different groups of wage-workers from 1550 to 1650. Servants are excluded as only two servants’ inventories recorded livestock: the inventory of Anthony Robinson listed one stag and five sheep on 15 March 1643/1644, while James Smith, mentioned earlier, owned a range of livestock, including four keye, two twinters, two stirks, one calf, one nag, one colt and one swine.Footnote 67

Table 5. Percentage of inventories recording livestock, 1550–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

a Note: Cattle includes cows.

The general comparison shows that the animal ownership was quite similar between building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees: the dominant role of cattle was followed by horses, poultry and pigs, while sheep were found in fewer than 36 per cent of inventories in each group. In contrast, only 7.4 per cent of labourers owned pigs, and their percentages of horses, poultry and sheep were all below 21 per cent. However, more than half of the inventory samples in each group listed cows. Dairying equipment, such as churns, cheese presses, cheese moulds and cheese vats, was also recorded in inventories, indicating related production activities.

A further comparison can be made on the total value of livestock owned by different groups of wage-workers. Table 6 presents the average and median total values of animals owned by 67 Lancashire building craftsmen, 30 labourers and 36 Shuttleworth employees between 1550 and 1650. While the average total value of animals owned by Shuttleworth employees was £19.1, higher than that of building craftsmen (£14 8s.), their median values were closer, at £14 2s. and £12 10s. In contrast, both the average and the median total values of animals owned by labourers were the lowest.

Table 6. Total values of animals in wage-workers’ inventories, 1550–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

a Note: Inventories with group items are excluded.

Inventories did not consistently record real property, but scattered evidence here supports the estimation of wage-workers’ access to pasture. Firstly, some inventories listed leaseholds. Among 93 building craftsmen’s inventories, 26 listed the tack of ground (a lease of land). Laurence Swainson, for example, a carpenter of Cartmel, left both hay ground and pasture ground on 10 June 1628, which were valued at 24s. and £11, respectively.Footnote 68 In addition, some wage-earners shared land and ownership of animals with others. On the one hand, certain testators’ livestock was kept on others’ properties. For example, John Edmondson, a labourer of Worsley, Eccles, owned 18 sheep, which were valued at £3 and were kept at his father’s house.Footnote 69 The inventory of Richard Marsden, a freemason of Sharples, Bolton, recorded that he owned three cows, two of which were housed by Ellis Houldens and Thomas Walshe.Footnote 70 On the other hand, the value of some animals was divided, indicating the shared ownership of livestock. Thomas Willisell, for instance, a bachelor whose inventory was made on 12 June 1610, owned ‘a mare the half price at 33s. 4d., 8 kyne and a half cow, a twinter heffer, a stirk and two calves the half price at £14 4s. 9d., 38 sheep and 11 lambs the half price at £3 8s. 10d.’.Footnote 71

Combined with the data from arable farming, it is possible to compare the percentages of wage-workers’ inventories that documented crops, livestock and leasehold land. As shown in Table 7, while the percentage of Lancashire labourers who left leaseland was close to that of Shuttleworth employees, at 13 per cent and 14.6 percent, respectively, it is considerably lower than that of building craftsmen who owned leaseland (28 per cent). By contrast, the percentage of building craftsmen who left crops was 65.6 per cent, higher than that of labourers (42.6 per cent) but lower than that of Shuttleworth employees (79.2 per cent). In addition, while the percentages of Shuttleworth employees and building craftsmen who owned livestock and any listed items were similar, the percentages of Shuttleworth employees’ inventories that recorded crops, livestock or any listed items exceeded those in labourers’ inventories. This indicates the greater agricultural engagement of Lancashire building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees and highlights the importance of access to land in their household economies.

Table 7. Percentage of inventories recording crops, livestock and leasehold land, 1550–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

a Note: Crops include oats, wheat, bean, peas, barley, rye, corn, groat and meal. Leaseland only counts those listed in inventories.

5.3 Textile production

Textile production was another significant economic activity in Lancashire.Footnote 72 Generally, textile processing can be divided into different stages, such as preparation, spinning and weaving, with a clear gender division of labour.Footnote 73 When the Shuttleworths lived at Smithills and Gawthorpe, their accounts recorded payments to both male and female labourers involved in textile processes. The analysis of inventories here suggests that textiles played a more important role in the family earnings of building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees than in those of labourers.Footnote 74

Table 8 presents the percentages of 195 inventories listing evidence of textile processing. While more than half of the inventories left by Lancashire building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees show evidence of textile production, less than one-third of labourers’ inventories indicate the same. However, the percentages of Lancashire labourers and Shuttleworth employees who owned preparation items such as wool combs and cards were similar, at 24.1 per cent and 25 per cent, respectively. In contrast, while inventories of building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees had higher proportions of spinning items, fewer than 30 per cent of labourers’ inventories listed any items related to spinning. In addition, the proportion of items related to weaving was around 10 per cent among these three groups of wage-earners, significantly less than the 48 per cent observed for farmers by Keibek and Shaw-Taylor, who analysed inventories from the northeast corner of Blackburn hundred, Lancashire, between 1558 and 1640.Footnote 75

Table 8. Percentage of inventories recording textile processing, 1550–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

a Note: Inventories listing ‘comb’ or ‘card’ are used to indicate the preparation of textiles.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the textile production presented here can only be regarded as a base line. The main reason is that some cheap items, such as heckles and hatchels related to linen production, might not have been recorded in inventories. It is also not uncommon to find inventories that only mention yarn. For example, Richard Sudell, a waller of Chorley, owned linen yarn valued at 23s. in his inventory of 1629.Footnote 76 The extent of textile processing within local families might have been greater than is indicated by the inventories.Footnote 77

6. Standards of living

To measure different levels of wealth, the value of inventories is generally divided by historians into three types: total value, material wealth and domestic wealth.Footnote 78 While domestic wealth is often used to measure material standards of living, the inventoried items were often grouped together in the current sample, making it challenging to quantify the value of individual household goods.Footnote 79 Therefore, this section focuses on the comparison of total and material wealth values of inventories as well as the categories of consumer goods recorded. The findings show that Shuttleworth employees were not only wealthier than labourers whose occupations were recorded in probates but also enjoyed better lives than the latter.

6.1 Inventoried wealth

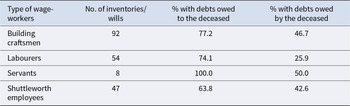

When analysing the value of inventories, one challenge is the omission of debts.Footnote 80 Debts had diverse forms. Based on Hampshire’s probate accounts recorded between 1623 and 1715, Muldrew listed different types of debt, such as sales credit, rents and mortgages.Footnote 81 While inventories sometimes listed debts owed to testators, it is less common to find debts owed by testators, as there was no requirement to record them. Instead, details of debts owed were more commonly found in wills or probate accounts, although the accounts of labourers rarely survived.Footnote 82 Nevertheless, all available wills, inventories and probate accounts are used to compare the values of 201 wage-workers’ debts.

Table 9 shows the percentages of probate documents recording debts. Compared to Shuttleworth employees, other Lancashire wage-workers were more likely to list debts owed to the deceased, with more than 70 per cent of their probates recording such debts. In particular, all servants’ inventories recorded debts. Conversely, while more than 40 per cent of servants, building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees owed debts to others, for Lancashire labourers the figure was only 25.9 per cent, indicating their lower ability to borrow money or participate in local credit transactions.Footnote 83 This, however, should not be overstated as some labourers were wealthy enough to leave substantial amounts of money. While three Lancashire labourers of the current sample left at least £17 in cash, Thomas Butterworth was a particularly notable case. Despite being titled as a labourer in his will, Butterworth left £224 13s. 4d. in cash in 1598.Footnote 84 His inventory indicates that he earnt cash income by leasing out land.

Table 9. Percentage of probate documents recording debts

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

Table 10 presents the total and material wealth values of Lancashire wage-workers’ inventories. The comparison shows that the values of Shuttleworth employees’ inventories were consistently the highest. The fact that more than half of these employees were described as husbandmen and yeomen could be a main reason for this wealth distribution. These were followed by the values of inventories left by building craftsmen and labourers, while servants’ inventories had the lowest values. The employment status of servants was an important reason why the values of their inventories were always low: most of them did not leave any goods because they had not yet set up independent households. For other types of wage-workers, the data indicate that Lancashire labourers were less wealthy than building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees.

Table 10. Value of inventories

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

a Note: Material wealth excludes the value of leases and debts, and includes only household goods, work-related goods and cash.

6.2 Consumer goods

Although labouring people were identified as the ‘meaner sort’, this does not mean that they were not consumers.Footnote 85 In fact, both paupers’ and labourers’ inventories listed a wide range of consumer goods.Footnote 86 In addition, Muldrew tracked the values of certain items owned by labourers such as linen, bedding and pewter, and found that they showed a rising trend between 1550 and 1650.Footnote 87 While the current sample did not allow for the values of inventoried goods to be tracked, a comparison of the ownership of consumer goods indicates that Shuttleworth employees enjoyed higher standards of living than those reflected in labourers’ inventories.

Table 11 presents the percentages of 195 inventories recording 13 types of household goods. Similar to the production goods discussed earlier, some categories here include a wide range of objects. The category of ‘bed’, for example, includes not only feather beds but also other types of bed such as ‘chaffe bed’, ‘truckle bed’ and ‘standing bed’. The category of ‘coverlet and blanket’ includes other coverings like caddow. The category of ‘chest and box’ also includes ‘coffer’ and ‘ark’. Some categories overlap: as ‘candlestick’ includes candlesticks made of pewter and brass, these are also counted in the category of ‘brass’ or ‘pewter’, accordingly. Regarding the ‘chimney’, this term referred to a fire-grate or fire-pan, and normally appeared together with other items such as tongs, spit and crow.

Table 11. Percentage of inventories listing various household goods, 1550–1650

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

The comparison shows that the percentages of Lancashire building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees who owned consumer goods were similar across a wide range of items. These items include beds and feather beds, cushions and pillows, chests and boxes, chairs and stools, brass, pewter and books, with these percentages clearly higher than those for labourers. Only in the category of coverlets and blankets can we find closer proportions among these three groups of wage-earners. In addition, while around eight per cent of building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees owned luxury goods such as silver spoons and glasses, fewer than four per cent of labourers did. Thus, depending solely on labourers’ inventories cannot fully present the actual material living standards of wage-earners between 1550 and 1650.

The analysis of inventories reveals that while the percentages of building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees who owned production items were similar from 1550 to 1650, Lancashire labourers owned fewer crops, agricultural tools and livestock. Only in the preparation and weaving stages of the textile processing can we find similar percentages of goods between labourers and Shuttleworth employees. A clear gap is also observed in debts, total and material wealth values, and the ownership of consumer goods. In fact, compared with those described as labourers in their inventories, Lancashire building craftsmen and Shuttleworth employees had more mixed household economies and enjoyed higher material standards of living. Therefore, inventoried labourers cannot be taken as representative of all wage-earners during this period. This can be further illuminated by examining life-cycle changes in standards of living.

7. Life-cycle changes in living standards

Wage-earning was often still a life-cycle phase during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Consequently, some wage-workers held different occupations or status over time. John Hajnal, for instance, argued that servants’ social class could be the same as their master’s before and after their service.Footnote 88 Concentrating on 51 Shuttleworth employees, this section compares their (maximum) annual wage-earnings during their employment with the material wealth values of their inventories, exploring the significance of monetary wages to different types of wage-worker throughout their life cycle. In addition, family structures are reconstructed using wills to examine the diverse wealth conditions among wage-workers of different marital status.

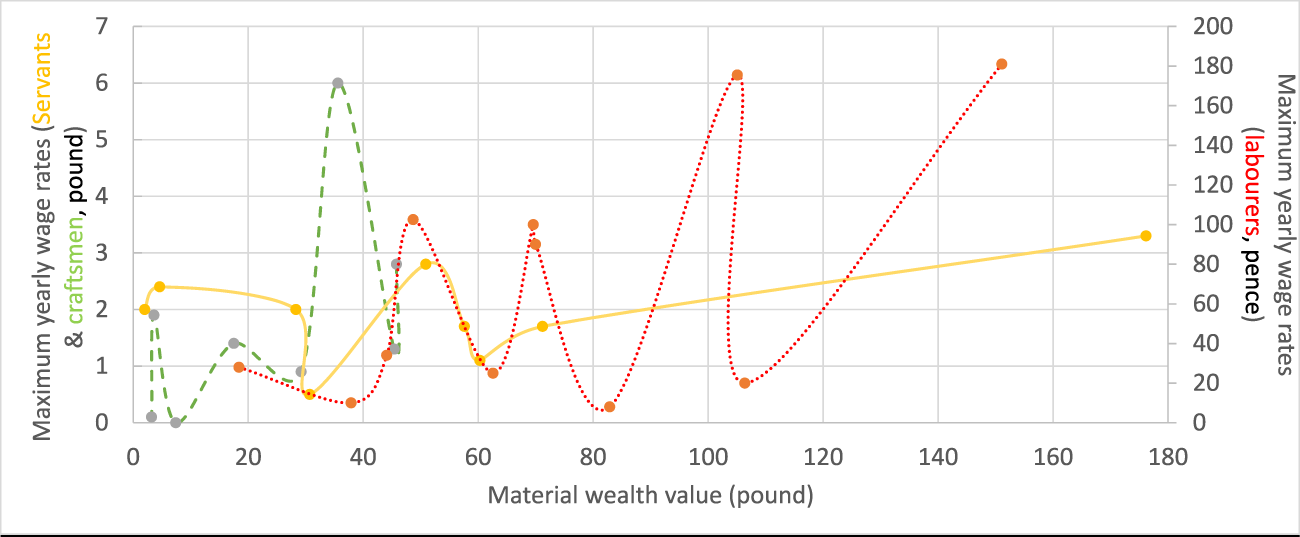

7.1 Servants, labourers and building craftsmen

As shown in Appendix 2, these 51 workers are divided for analysis into three groups: servants (9), labourers (building and agricultural labourers, 30) and craftsmen (12).Footnote 89 Owing to the diverse wage rates and mixed payments (by day or task), maximum wage rates are selected for comparisons. In addition, although the majority of Shuttleworth employees were provided with meals during their employment, while others covered their own food and drink, certain wage rates are marked with ‘own table’ in brackets. Based on these rules, Figure 1 presents the maximum yearly wage income and material wealth of 28 Shuttleworth employees whose two groups of data were well-preserved, namely, 9 servants (the solid line), 11 labourers (the dotted line) and 8 craftsmen (the dashed line) employed for building Gawthorpe Hall.

Figure 1. Maximum yearly wage income and material wealth value of 28 Shuttleworth employees. The solid line represents servants; the dashed line represents craftsmen; and the dotted line represents labourers.

Among nine servants, eight of them served between 1586 and 1598, with Thomas Yate being the only one employed after the family moved to Gawthorpe. As shown by the solid line, the living standards of wage-workers changed dramatically over time, and servants with lower wage rates often achieved higher wealth after they left service. Among five servants who earnt at least £2 per year during their employment, Thomas Yate and Peter Ashton ended their lives with a material wealth value exceeding £50. The material wealth value of the remaining four servants earning less than £2 annually was consistently higher than £30.

The analysis of inventories and wills further indicates that servants’ level of wealth was determined by different factors. Thomas Yate and Richard Longworth were the only two servants who left cash after they died. Yate’s inventories included money and gold valued at £165 4s. 3d., while Longworth left £40 in cash.Footnote 90 In addition, the probates of three lower-paid servants showed evidence of access to land. Oliver Stones’ inventory listed one close of land taken for one year.Footnote 91 The inventory of Thomas Longworth listed the value of one close, 13s., and his will recorded the bequest of two and a half acres of land to his son, Ralph Longworth.Footnote 92 Richard Stones’ will included the bequests of leasehold land and husbandry implements.Footnote 93 In fact, six out of nine servants were described as yeomen or husbandmen, indicating their involvement in farming. Thus, two stages of life-cycle wealth can be summarized here: monetary wages, together with board and lodging, decided servants’ living standards during their service; however, after leaving service, access to land, whether inherited from their families or rented from others, became the main factor determining their levels of wealth.

Regarding the 11 labourers, as shown by the dotted line, the comparison also supports the weak connection between wage levels and the material wealth values measured using inventories. While more than half of the 11 labourers earnt less than 3s. per year from the Shuttleworths, the material wealth values of their inventories ranged widely from £18 8s. to £106 8s. In fact, nine of them were husbandmen and yeomen, indicating that they worked on their own farmland. Owing to the gap between employment periods and probate dates, it is hard to identify when and how these testators obtained access to land. Nevertheless, current evidence supports the estimation that some of them must have been landholders while working for the Shuttleworths.Footnote 94 For example, Ferdinando Hetone, a yeoman, received the highest annual wage income, 15s. 1d.Footnote 95 Although Hetone was paid for keeping the tithe corn of Heaton at his house and barn, and leading and winnowing tithe corn of Heaton between 1583/1584 and 1593, it is very likely that he employed other labourers to complete these tasks. Hetone was probably a tenant farmer of the Shuttleworths.

John Hartley was described as a labourer in the accounts and worked 71 days in 1601, which is the highest number of working days per year in the sample. He earnt 14s. 7.5d. with food and drink provided for serving wallers and making mortar in that year, and his wife worked 11 days during the harvest season and received 1s. 11d. from the Shuttleworths. In fact, Hartley’s wife appeared in harvest months of the following years when her husband did not work for the same employer, although she worked fewer than ten days each year. If Hartley had worked 250 days per year for the Shuttleworths with diet provided, he could receive £2 12s. 1d. per year, which would be enough to feed his wife.Footnote 96 But he did not. As this was a period when the Shuttleworths had a great demand for wage labour, it can be assumed that either Hartley found higher wages elsewhere or he was busy working on his own farmland. As there is no evidence of any other high-paid work in the locality, the latter is the more reasonable explanation, particularly as Hartley was titled as husbandman in his inventory, which also listed agricultural implements, livestock, and wool combs and cards.

The comparison of eight building craftsmen’s data also reveals that material wealth values measured using inventories did not always correlate with wage levels during their employment. Daily wage rates received by these craftsmen were 4d. or 5d. per day with food provided. While the maximum annual income of John Haworth was higher than that of John Baxsenden, Richard Ryley and James Wood, the material wealth value of Haworth’s inventory was the lowest, at £3 12s. In addition, when Anthony Whythead received the highest annual wage (£6), more than double the annual wages of John Whythead and Christopher Hodgson, his material wealth value (£35 12s.) was less than that of the latter two craftsmen (£45 16s. and £45 8s.). Nevertheless, Anthony Whythead was owed £185 10s. by others. Thomas Grimshaw was another man whose inventory listed a large amount of debts owed to him (£41 14s.), although the material wealth value of his inventory was only £3 4s. While details of debts were not provided, these records indicate their active participation in local credit networks.

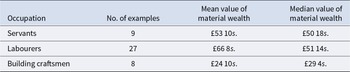

Owing to their specific skills, it is not surprising that building craftsmen received higher daily wage rates than labourers. If we use current estimations of the cost of diet and working days per year to calculate real wages, it is fair to conclude that building craftsmen enjoyed higher standards of living than labourers. However, the comparison of material wealth values here provides a different perspective. As shown in Table 12, both the mean and the median values of the material wealth of Shuttleworth building craftmen’s inventories were lower than those of the material wealth of Shuttleworth servants’ and labourers’ inventories.

Table 12. Material wealth value of the Shuttleworth employees

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

Note: Testators who did not leave inventories are excluded.

One explanation is that, compared with servants and labourers, building craftsmen were less likely to participate in agricultural activities, leading to the lower material wealth value. Since not every Shuttleworth employee listed land in their probate documents, here we select arable crops, livestock, agricultural implements and occupations (yeoman and husbandman) as proxies to measure self-employment in agriculture. While around 90 per cent of servants’ and labourers’ inventories showed evidence of agricultural activities, only 50 per cent of building craftsmen’s inventories did. Nevertheless, lower material wealth values do not necessarily mean that building craftsmen had lower standards of living. In fact, inventories of building craftsmen who did not leave any production items listed some luxury goods. For example, Anthony Whythead owned two feather beds and John Haworth left silk stockings, indicating that they enjoyed comfortable living standards at some point during their life cycle.Footnote 97

7.2 Family structures

As family size also influenced wage-workers’ dependence on money wages and their living standards, a further comparison can be made to explore this. At time of death, of the 51 Shuttleworth employees, 32 were married, 4 were unmarried and 15 did not leave wills providing this information. Married families can be further divided into three groups: families without children recorded in wills (2), families with children (23) and families with children and grandchildren (7). Richard Ryley was the only testator whose will left information about children’s ages. According to his will of 1619, his four children were all aged under 20 years.Footnote 98 Ryley worked 78 days for the Shuttleworths and earnt a total of £1 7s. 6d. in 1604. If we take the maximum daily cost of provided diet (5d. per day) into consideration, Ryley’s annual earnings from the Shuttleworths would be £3, which was enough to cover his own diet in that year, but inadequate to feed a family with children.Footnote 99

Table 13 compares the average total and material wealth values of inventories left by Shuttleworth employees according to their marital status. Although the average material wealth value of inventories left by two testators who were married without children, as recorded in their wills, was the lowest at £20 2s., their average total value was the highest at £112 18s. In families with evidence of two generations, both the average total and the material wealth values were lower. This type of family was probably the most sensitive to economic changes because they were engaged in raising children. By contrast, the average total and material wealth values of inventories left by unmarried testators and those who mentioned grandchildren in their wills were closer, although the latter always had higher figures. The long-term accumulation of wealth and the contribution made by older children are likely explanations.

Table 13. Average value of inventories left by the Shuttleworth employees with different marital status

Source: Probate inventory dataset, LRO.

a Note: This group includes testators who did not list wives and children in the wills; btestators who did not leave inventories are excluded.

This comparison is more suggestive than confirmative, as family structures could change over time. Nevertheless, it shows that, generally, families with younger children who could barely contribute to family income were more likely to suffer from economic crises. In contrast, adults without the heavy responsibility of feeding large families could enjoy better standards of living.

The provision of diet by the Shuttleworths meant that their employees took less cash back home. The correlation between maximum annual wages during the employment and material wealth values measured using inventories remains negative, even if the estimated 250 working days per year is factored into consideration. Nevertheless, some key points can be summarized here. Firstly, money wages mattered a lot among rural servants and building craftsmen during their employment. Accumulated wages laid the foundations for servants’ future lives and guaranteed building craftsmen’s comfortable lives by affording luxury goods. Secondly, the fact that some labourers were landholders during their employment means that they did not rely for a living solely on money wages earnt from the Shuttleworths. Access to land in fact mattered a great deal to the life-cycle changes in the living standards of early modern rural labourers, as well as servants who left service. Lastly, comparison of the values of Shuttleworth employees’ inventories indicates that families with two generations, namely, parents and children, were more vulnerable to misfortunes than other types of family.

8. Conclusion

This article uses the Shuttleworth accounts 1582–1621 and probate inventories left by both Shuttleworth employees and other Lancashire wage-workers whose occupations were recorded between 1550 and 1650 to explore life-cycle changes in the living standards of Northern rural wage-workers. The discussion concentrates on two main aspects: examining the representativeness of inventories left by labourers whose occupations were recorded, and exploring individual wage-workers’ living standards throughout their life cycle.

When using labourers’ inventories, Muldrew argues that ‘working for wage was something that individuals designated as “labourers” on documents did, or had done, and thus, using their inventories does give us a unified sample of labouring families’.Footnote 100 This approach, however, obscures the change of the labouring people’s status during their life cycle and their diverse backgrounds.Footnote 101 Robert Aspden, for example, was a loyal servant who worked for the Shuttleworths from at least 1583. He was titled as yeoman of Smithills in a deed of 1593, while his service lasted until 1596.Footnote 102 After that, Aspden became a tenant farmer of this family, as the accounts recorded that, on 1 February 1600–1601, the Shuttleworths received £9 16s. from Aspden for ‘the tithe of Heaton of the corn and grain there for one whole year ending the eighth of September last as it does and may appear by his lease’.Footnote 103 Thomas Yate was another servant who worked at least until 1621. Although he was titled as yeoman in his will of 1641, Yate expressed his gratitude towards his master, Richard Shuttleworth, indicating his continued service for this family.Footnote 104 Both Aspden and Yate were wage-earners whose experiences are hidden behind the simple analysis of labourers’ inventories.

The comparison of inventoried items also shows that we need to reconsider carefully how to use inventories to measure living standards. It is true that some wage-earners could be too poor to leave inventories, but it is also important to note the wide wealth distribution among the labouring people, as pointed out by Everitt.Footnote 105 The clear differences in the percentages of production and consumer goods, as well as inventoried wealth, between inventories left by Shuttleworth employees and Lancashire labourers whose occupations were recorded in probates show that using labourers’ inventories alone underestimates living standards of wage-earners between 1550 and 1650. In fact, some workers who lived during this period had diverse sources of income and could enjoy comfortable lives.

Using estimated ‘real’ annual incomes to measure standards of living presents an idealized model, which overemphasizes reliance on waged labour for a living. It suggests that increasing labour input becomes a reasonable solution in the face of economic crises, particularly for landless labourers. However, being recorded as labourers in accounts does not necessarily mean that these people relied solely on money wages for a living. In addition, irregular employment opportunities in the labour market made it hard to work 250–260 days per year. Whittle and Jiang, for example, find that despite a few male agricultural labourers working more than 200 days per year for wages in early seventeenth-century England, most of them worked fewer than 100 days.Footnote 106 The evidence from Shuttleworth employees’ inventories shows that using real wages alone not only overestimates some wage-workers’ dependence on money wages but also underestimates their abilities to survive during the difficult times of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries using other resources.

The comparison of Shuttleworth employees’ wage levels during their employment and the material wealth values of their inventories has further implications for understanding life-cycle changes in living standards. Firstly, it is important to recognize the impact of labouring people’s occupational distinctions on their changing living standards. While rural servants and building craftsmen could accumulate more money from their employment, some labourers relied less on money wages for a living. Instead, access to land played such a key role that even ‘unskilled’ agricultural labourers could enjoy reasonable standards of living without working full-time for wages.

Secondly, although rural building craftsmen had the ability to afford some luxury goods owing to their high wage rates, current evidence does not support the conclusion that these wage-earners worked harder to obtain consumer goods in the early seventeenth century. Jan de Vries argued that from the late seventeenth century onwards, increased wage-earning and industriousness was a response to the desire to own modest luxury goods.Footnote 107 The findings here suggest that in the early seventeenth century ownership of such goods correlated more strongly with certain occupations than with wage-earning more generally.

Lastly, while the family structure changed over time and its impact on individual wage-workers’ living standards remains to be explored further, this article suggests that labouring families with two generations were the most vulnerable to financial crises. This is particularly the case when wives had to look after young children at home, restricting their earning capacity.

As monetary wages can only be used to measure the purchasing power of wage-workers during a specific period of their life cycle, and did not have a positive correlation with wage-workers’ living standards at death measured using inventories, to understand the real living standards of early modern wage-workers, historians need to pay careful attention to how wage-earning was combined with other forms of income generation and how such incomes varied across the life cycle. In addition, more research into the actual circumstances of early modern wage-earning is needed for other localities and regions to confirm whether the findings of this study of late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Lancashire are duplicated elsewhere.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article (Appendix) can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0268416025000098.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the European Research Council (FORMSofLABOUR grant 834385) and the Economic History Society (Tawney fellowship 2023–2024; Research Fund for Graduate Students 2024). I appreciate the helpful comments and advice from the anonymous reviewers and editors. I would like to thank Jane Whittle, Henry French, Mark Hailwood and Taylor Aucoin for offering help and support. I am also grateful to the audience members of the Cambridge Early Modern Economic and Social History Seminar (2023), the Early Career Researcher Symposium of the Institute of Historical Research (2023) and the Economic History Society Annual Conference (2024) who commented on earlier versions of this research.