Introduction

During the last decades, issues related to nativism – the ideology which holds that the interests and the will of ‘the native people’ should enjoy absolute priority and that non‐native elements are fundamentally threatening the homogenous nations state (Betz, Reference Betz2017, p. 171; Mudde, Reference Mudde2010, p. 1173) – have become more salient in liberal democracies. In growing numbers, citizens who are strongly concerned about immigration (henceforth: ‘nativists’) have turned their back on established parties all over the Western world. Instead, they are flocking to populist radical right parties and leaders, which usually are critical of the existing democratic political system. Some are even turning to violence, as illustrated by the storming of Capitol Hill. However, only a small fraction of nativists has turned to undemocratic actions and violence, and populist radical right parties usually criticize representative democracy for its lack of democracy and not because it is too democratic (Müller, Reference Müller2016). Still, from a democratic viewpoint, there are reasons to be concerned about the growing political importance of nativism.

Several studies suggest that nativists are more politically discontent than are citizens with a more positive outlook on immigration (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Levy and Wright2014; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021; McLaren, Reference McLaren2012a, Reference McLaren2012b, Reference McLaren2015, Reference McLaren2017; Pennings, Reference Pennings2017). Within political support research, it has been shown that longer periods of such discontent (i.e., low specific support) affect citizens’ more general legitimacy beliefs negatively (Claassen & Magalhães, Reference Claassen and Magalhães2021). Recently, it has also been demonstrated that West European nativists differ from non‐nativists in their views on democracy. For example, there is a strong correlation between nativism and support for ‘unconstrained’ forms of democratic decision making, and a nativist reluctance to perceive liberal democratic majority constraints as important to democracy in general (Kokkonen & Linde, Reference Kokkonen and Linde2021).

What we do not know, however, is whether nativists’ observed reluctance towards – and discontent with the functioning of – liberal democracy spills over into a more general scepticism about democracy as a system of government and may eventually attract nativists to non‐democratic alternatives. Indeed, the lack of research on the relationship between nativist attitudes and diffuse support is surprising, given how salient issues related to immigration have become in recent years. Using data from the European Social Survey (ESS) and the European Values Study (EVS), we make a first attempt to systematically examine the relationship between nativism and diffuse support for democracy, or what Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a) has termed the ‘democratic mood’.

Nativist attitudes, democratic discontent and diffuse support

Earlier findings on nativists’ democratic discontent indicate that people with strong nativist attitudes are discontent because they perceive the political system to be malfunctioning, particularly when it comes to policy‐areas nativists perceive as most important. In a series of studies, McLaren has argued that people with strong anti‐immigration views have lost their trust in the political system due to perceptions of unresponsiveness, caused by feelings of betrayal by the political elites who nativists believe have sold out the public by not protecting the national community and the interests of the native population from large‐scale, and increasing, immigration (McLaren, Reference McLaren2012a, Reference McLaren2012b, Reference McLaren2015). This interpretation is supported by the fact that the relationship between nativist attitudes and political distrust is particularly strong in countries that have been more welcoming of immigrant incorporation (McLaren, Reference McLaren2017), have a long history of immigration (McLaren, Reference McLaren2012a, Reference McLaren2015) and that have implemented multicultural policies (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Levy and Wright2014). Is there reason to expect that this negative association between nativist attitudes and specific support found in earlier research should spill over to more diffuse types of support?

It has for long been assumed that longer periods of perceived poor performance affect citizens’ more general legitimacy beliefs negatively, an argument that recently also has been empirically verified (Claassen & Magalhães, Reference Claassen and Magalhães2021). People harbouring strong anti‐immigrant sentiments have for long been on the ‘losing’ side policy‐wise, at least in Western Europe, where levels of immigration have been steadily increasing in the last decades (McLaren, Reference McLaren2015). From a performance perspective, nativist concerns about lacking responsiveness and representation are likely to affect not only satisfaction with the way democracy works and political trust, but also more diffuse support for democracy as a system of government. Thus, taking conventional models of political support as a point of departure (Easton, Reference Easton1975; Norris, Reference Norris1999, Reference Norris2011), we expect that the negative relationship between nativist attitudes and specific support found in earlier research will affect also diffuse support for democracy. Eventually it may even make nativists ponder alternatives to democracy – even undemocratic ones.

Nativist ideology and diffuse support for democracy

There are also reasons to expect a negative relationship between nativism and support for democracy due to nativist ideology, and thus independent of perceptions of poor performance and feelings of losing out politically. A recent study indicates that nativists are sceptical of democracy even when they are electoral winners (Bartels, Reference Bartels2020). Drawing on a large survey of US Republicans carried out in January 2020, while Donald Trump was still president and had relatively high approval rates, Bartels finds ‘ethnic antagonism’ – a concept closely related to our operationalisation of nativism – to be a powerful predictor of non‐democratic sentiments. Thus, nativists seem to be less supportive of democracy also when they are electoral winners when their levels of specific support should reasonably be high. This suggests a more fundamental conflict between nativism and diffuse support for democracy. However, it remains an open question whether Bartels’ findings travel to Europe, given that the US context is very specific, which Bartels also acknowledges. In this study, we therefore shift focus to the relationship between nativist attitudes and more diffuse support for democracy in a West European setting.

Is there a more fundamental difference between nativists and non‐nativists that warrants us to expect a similar relationship in Europe? Previous research has shown that nativists tend to support more “unconstrained” forms of democratic decision making, and are reluctant to perceive liberal democratic majority constraints as important to democracy in general (Kokkonen & Linde, Reference Kokkonen and Linde2021). This indicates that nativists have a different view of democracy than non‐nativists. It does, however, not necessarily mean that nativists do not support democracy. Rather, it indicates that they have a different opinion of what democracy is and should be. Therefore, it is not clear from the limited body of previous research what we should expect of the relationship between nativism and diffuse support when it is not founded by citizens’ discontent.

There is, however, one factor that may turn nativists away from democracy as it functions today – the fact that the composition of the people has changed over time. Even though a ‘pure native people’ might never have existed outside the minds of nativists, it is a fact that most West European populations have become more diverse in the last decades. Today, immigrants, and descendants of immigrants, make up a large percentage in most West European countries. From a nativist perspective that is problematic, as such ‘foreign elements’ are not part of, but constitute a threat to, the native people. As a consequence, it would not be farfetched to assume that nativists start to oppose a political system which gives foreigners influence over what (in their mind) is rightly the native people's country. In short, a system (as democracy) that gives everyone an equal voice in politics is an abhorrence to those who believe that not everyone should have an equal voice in politics. Instead, they could see a strong leader and/or expert and army rule as more attractive alternatives. Parallels to this line of reasoning can been seen in White supremacists’ attitudes to the political system during the Segregation Era in the United States, and under Apartheid in South Africa. If we are right, there is a more fundamental opposition between nativism and diffuse support for democracy than the literature on anti‐immigration attitudes and specific support suggests. At least in multicultural societies.

In the empirical analysis we use indicators that arguably tap different aspects of (diffuse) political support. The first, is asking respondents to assess ‘how democratic’ they perceive their country to be. This indicator is admittedly more evaluative and experiential than principled and diffuse in nature. However, it does not ask respondents to evaluate how democracy works in practice but rather to assess the general ‘democraticness’ of the current political system. In the light of the most frequently applied analytical frameworks in political support studies (Easton, Reference Easton1975; Norris, Reference Norris1999), this indicator is clearly more diffuse in character than, for example, the satisfaction with democracy item, which has been employed in earlier studies assessing the importance of anti‐immigration attitudes (McLaren, Reference McLaren2015; Pennings, Reference Pennings2017). Recognising the multidimensionality of political support, it would clearly be possible to be dissatisfied with the way democracy works in practice, while at the same time assessing the political system to be highly democratic. The remaining indicators used in the analysis are explicitly asking respondents about their approval of democratic values and rejection of authoritarian alternatives and have been used in numerous studies of diffuse support for democracy (e.g., Norris, Reference Norris2011; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Mishler and Haerpfer1998).

We thus propose the following hypotheses to be tested in the empirical section:

H1. Nativists perceive their national democracy to be less democratic than do non‐nativists.

H2. Nativists express lower levels of diffuse support for democracy as a system of government than do non‐nativists.

H3. Nativists express lower levels of diffuse support for democracy as a system of government than do non‐nativists also after controlling for political discontent (i.e., their specific support).

We test our hypotheses using data from the European Social Survey (2012) and the European Values Study (2017). In the analyses, we regress our indicators of support for democracy on nativism in models also including a battery of control variables shown to be important for political support. We include all West European countries that are available in the two surveys.

Nativism: Conceptualization and measurement

Although the studies of concern about immigration and political trust/support referred to above do not explicitly use the concept of nativism, the operationalisation and measures they use strongly overlap both with definitions and measurements of nativism. Within comparative politics, nativism has frequently been defined in accordance with Mudde's definition as an ‘ideology which holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (“the nation”) and that non‐native elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threating the homogenous nation state’ (Mudde, Reference Mudde2010, p. 1173).

The latter part of this definition points to the conclusion that nativists perceive immigrants to be a threat to their country (Kokkonen & Linde, Reference Kokkonen and Linde2021). The measures of nativist attitudes we use tap into this dimension of nativism. In the ESS we use three items, concerning attitudes toward immigrants, to construct an index of nativism: ‘Would you say it is generally bad or good for [country's] economy that people come to live here from other countries?’ (0 = bad, 10 = good), ‘Would you say that [country's] cultural life is generally undermined or enriched by people coming to live here from other countries?’ (0 = undermined, 10 = enriched), and ‘Is [country] made a worse or a better place to live by people coming to live here from other countries?’ (0 = worse, 10 = better). The scales are recoded so that higher scores denote stronger anti‐immigration sentiments. The resulting index varies from 0 to 10 (Cronbach's alpha = 0.85).

The measure in the EVS analyses includes three similar items: ‘Immigrants take (1), or do not take (10), jobs away from [nationality]’, ‘Immigrants make (1), or do not make (10), crime problems worse’, and ‘Immigrants are (1), or are not (10), a strain on the country's welfare system’. The resulting index varies from 1 to 10 (Cronbach's alpha = 0.79). In the analyses we follow Gelman (Reference Gelman2008) and standardize these indexes (and all control variables, except for dummy variables), by dividing them with two standard deviations. This means that the coefficient of nativism (and the other independent variables) should be interpreted as the change that takes place when moving from one standard deviation below the mean of nativism to one standard deviation above the mean. In the discussion of the results, we speak of this as the difference between strong nativists and strong non‐nativists.

Control variables

The control variables account for factors that may influence both nativism and our dependent variables. Since we expect that the potential effect of nativism on support for democracy is due to both perceptions of democratic performance and nativist ideology, we include respondents’ satisfaction with the way democracy works in the main analyses. To separate nativism from populism and authoritarianism – the other main ingredients in the populist radical right ideology – we include a dummy variable for voting for a populist radical right party and an index of authoritarian values, where the latter is an individual predisposition for order, security, conformity, and certainty, that is, values without explicit regime connotations (see Arikan & Sekercioglu, Reference Arikan and Sekercioglu2019; Tillman, Reference Tillman2013). We also control for respondents’ self‐positioning on the left‐right scale, voting for a ‘winning’ party, political interest, household income, social trust, education, age, gender and employment. The ESS models include satisfaction with the economic situation of the country. A similar measure is lacking in the EVS. More information on all variables can be found in the Supporting Information Appendix.

We run three types of models. A first with only nativism and no controls. A second with all controls, except satisfaction with democracy. And finally, one with all controls. We do so to illustrate how the association between nativism and diffuse support changes when controlling for the various factors. We graphically present the results using the full models. All other models are available in the Supporting Information Appendix.

Results

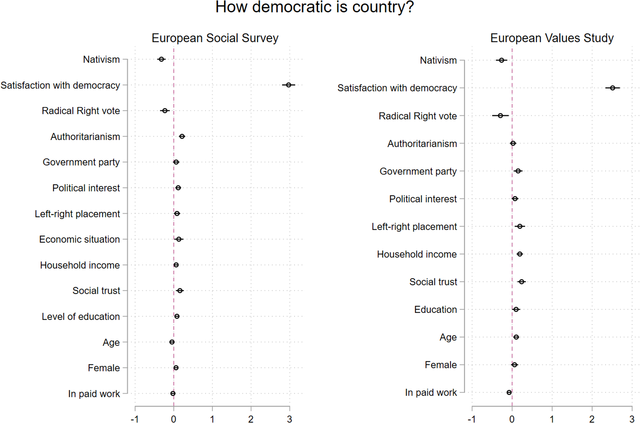

We start by examining whether the relative democratic discontent among nativists found in earlier research is reflected in their perceptions of the ‘democraticness’ of their country. Both the ESS and the EVS examine citizens’ evaluations of how democratically their country is being governed today, on a scale from ‘not at all democratic’ to ‘completely democratic’. In the ESS the scale runs from 0 to 10, and in the EVS from 1 to 10. As already discussed, this question could be viewed as the most evaluative, or experiential, item among those included in this study. Respondents’ assessments of how democratically their country is governed should obviously be based on their own experiences and evaluations of the democratic system rather than on abstract ideas about democracy.

Figure 1 presents one analysis based on the ESS and one on the EVS. Since the ‘democraticness’ item is more specific in nature, it is not surprising that respondents’ satisfaction with the way democracy works comes out as the most important predictor. However, in both surveys we observe a statistically significant negative relationship between nativism and perceived democraticness, which should arguably mean that nativists’ tendency to rate their country as less democratic is not only due to discontent with the way democracy works. The effect sizes are quite small. A change from strong non‐nativism to strong nativism generates a change of 0.32 points on the 11‐point ESS scale and 0.26 on the 10‐point EVS scale. It should however be noted that – apart from satisfaction with democracy – only the populist radical right vote in the EVS analysis has a stronger effect than nativism. If we exclude satisfaction with democracy, the coefficients of nativism increase considerably, to 0.78 in the ESS and 0.57 in the EVS.

Figure 1. Nativism and perceptions of how democratic the respondent's country is. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: European Social Survey round 6 (2012), European Values Study wave 5 (2017).

Note: Standardised regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors are clustered by country. Country dummies are included but not shown. Full models are presented in Tables A1 and A2 in the Supporting Information Appendix. For country specific effects of nativism see Figures A1 and A2 in the Supporting Information Appendix.

Interestingly, authoritarian values are positively related to evaluations of the degree of democraticness in the ESS, while not statistically significant in the EVS analysis. Moreover, electoral ‘winners’ – those who voted for a party that ended up in government – are not more likely to view the country as more democratic than are ‘losers’. Taken together, the findings provide support for our first hypothesis stating that nativists perceive their democracy to be less democratic than do non‐nativists.

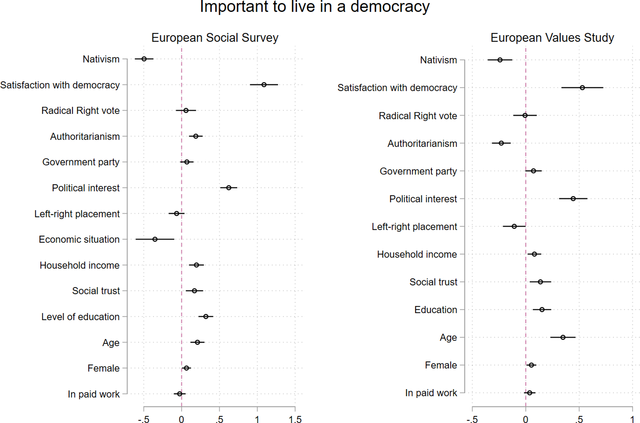

An intriguing question that follows from this is whether it may be that it is not so important for nativists that their country is democratically governed. We explore this question using two items asking how important it is for the respondents ‘to live in a democratically governed country’. The scale in the ESS runs from 0 (‘not at all important’) to 10 (‘extremely important’). The EVS uses an almost identical question with a response scale ranging from 1(‘not at all important’) to 10 (‘absolutely important’).

Figure 2 presents the main results. Interestingly, when applying the same model to this dependent variable, which is clearly more diffuse in nature, the effects of nativism come out as stronger compared to the more specific type of support examined above. Also here, the effect sizes are moderate but the strength of the association between nativism and perceived importance of living in a democracy trumps most other variables. In the ESS, only satisfaction with democracy and political interest are more important, while in the EVS age also comes out as slightly more important. The coefficients of nativism also increase by more than 25 per cent if satisfaction with democracy is excluded from the models.

Figure 2. Nativism and perceived importance of living in a democracy. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: European Social Survey round 6 (2012), European Values Study wave 5 (2017).

Note: Standardised regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors are clustered by country. Country dummies are included but not shown. Full models are presented in Tables A1 and A2 in the Supporting Information Appendix. For country specific effects of nativism see Figures A3 and A4 in the Supporting Information Appendix

Populist radical right voting is not significantly associated with less importance attached to living in a democracy. If we are allowed to speculate, this might be an indication that such parties first and foremost cater to voters that are discontented with the way liberal democracy works but still believe democracy to be better than non‐democratic alternatives. It should however be pointed out that also a majority of the more extreme nativists think that it is important to live in a democracy. So, it is not as if they all reject democracy, or think it is unimportant. Far from it. But democracy is clearly less important for some nativists.

We find conflicting associations between authoritarianism and perceived importance of democracy in both surveys. This is probably due to the difference in the indicators making up the two different indexes of authoritarianism (see the Supporting Information Appendix for information on index construction).

The results confirm Pennings’ (Reference Pennings2017) findings, using ESS data, showing that anti‐immigration attitudes are negatively correlated with both specific and diffuse regime support, even though we can show that the negative correlation with diffuse regime support persists also after controlling for the negative correlation with specific regime support.

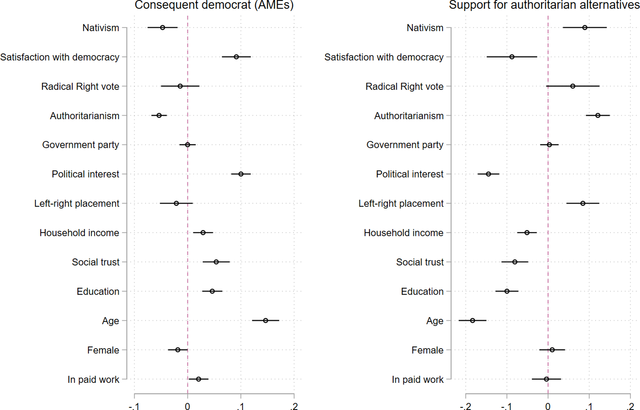

Potentially, nativists’ relatively lukewarm feelings for democracy may go hand in hand with a more positive view of alternatives to democracy. Unfortunately, the ESS does not contain any questions that allow us to test to what extent nativists ponder alternatives to democracy. However, the EVS includes a series of questions tapping support for democracy and alternative forms of government. We use these items to construct a measure of principled support for democracy which is based on rejection of non‐democratic alternatives and support for democracy (see e.g., Claassen, Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Mishler and Haerpfer1998).

The questions ask the respondents about their thoughts on different political regimes in the following way: ‘I'm going to describe various types of political systems and ask what you think about each as a way of governing this country. For each one, would you say it is a very good, fairly good, fairly bad or very bad way of governing this country?’ Respondents are then faced with the following forms of government: (1) ‘Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections’, (2) ‘Having experts, not government, make decisions according to what they think is best for the country’, (3) ‘Having the army rule’ and (4) ‘Having a democratic political system’. We single out respondents who, at the same time, rate democracy positively and all three non‐democratic alternatives negatively. Those respondents are given the value 1, and all others 0. The result is a dichotomous variable measuring principled support for democracy, or denoting respondents that are ‘consequent democrats’ (i.e., supporting democracy and rejecting authoritarian alternatives).

The results from a logit regression, presented in Figure 3 (left panel) show once again a negative relationship between nativism and support for democracy. The association is statistically significant but not very strong. The predicted probability of being a principled supporter of democracy is about 9 percentage points lower for the strongest nativists than for the strongest non‐nativists. The most non‐nativist respondents are thus about 23 per cent more likely than the most nativist respondents to be such principled supporters (0.48 vs 0.39). It is also important to remember that this is in the EVS, which, as we have seen, for the most part shows much smaller differences between nativists and non‐nativists than the ESS. The analysis also demonstrates that people with authoritarian values are less likely to be principled supporters of democracy, while there is no significant difference between people voting for the populist radical right and other parties. Once again, the coefficient of nativism increases somewhat if satisfaction with democracy is left out of the models.

Figure 3. Nativism and consequent support for democracy. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: European Values Study wave 5 (2017).

Note: Left panel presents average marginal effects from a logistic regression. The right panel presents standardized coefficients with 95% confidence intervals from an OLS regression. Standard errors are clustered by country. Country dummies are included but not shown. Based on Table A3 in the Supporting Information Appendix. For country specific effects see Figures A5 and A6 in the Supporting Information Appendix.

Since it has been argued and shown that survey questions that explicitly mention ‘democracy’ are problematic due to social desirability bias and interviewer effects (e.g., Ariely & Davidov, Reference Ariely and Davidov2011), the right‐hand panel in Figure 3 presents a corresponding analysis of nativism and support for authoritarian alternatives (strong leader, military rule and expert rule) as the dependent variable (ranging from 1 to 4, see Supporting Information Appendix for more information about the index). Dropping the democracy item does not substantially affect the results, as they appear more or less as a mirror image of the ‘consequent democrat’ analysis.

The relationship between nativism and support for authoritarian rule is positive and statistically significant. So are also authoritarian values. Interestingly, people further to the right ideologically are more likely to support non‐democratic alternatives than are people on the left, while left–right ideology does not matter when it comes to consequent democracy support (left panel).Footnote 1

To conclude, nativists do indeed seem to be less supportive of democracy than non‐nativists, which provides strong support for H2.Footnote 2 Part of the gap in diffuse support between nativists and non‐nativists can be ascribed to differences in satisfaction with democracy, but most of it remains also after controlling for differences in specific support. Thus, we can also confirm H3. The differences in diffuse support are more pronounced in the ESS than in the EVS, even if they are substantial also in the EVS. As the questions in the ESS and the EVS are almost identical, the differences cannot be explained by differences in the wording of the questions. One potential explanation is that nativists have become more supportive of (and satisfied with) democracy over time (the EVS was carried out in 2017 and the ESS in 2012). However, when assessing time trends in specific support using the satisfaction with democracy question, which is available in all rounds of the ESS (2002–2018), that is not the case. Rather, nativists have become less satisfied over time (see Figure A10 and Table A4 in the Supporting Information Appendix). Thus, we cannot explain why the effects are stronger in the ESS.

Concluding remarks

The empirical evidence presented in this study suggests a strong nativist dimension in political support in general – at least in Western Europe. Nativist citizens are not only, as shown in earlier research, less politically trusting and more dissatisfied with the way democracy works – they also express lower levels of diffuse political support and are more likely to support non‐democratic alternatives. Given this, it seems somewhat surprising that anti‐immigration attitudes have been largely ignored as a predictor in mainstream research on support for democracy. In relation to the growing body of research dealing with the consequences of the electoral success of the populist radical right, and ‘democratic backsliding’, most of the attention has been on populism rather than on nativism (and authoritarianism). However, while recent research has established a positive association between populist attitudes and diffuse support for democracy, the present study demonstrates that the relationship between nativism – which is generally perceived as the most important ideological component of the populist radical right – and support for democracy is negative.

One potential explanation for this could be that nativists for quite some time, have come to perceive themselves to be losing out – both electorally and policy‐wise – in West European democracies (McLaren, Reference McLaren2015). Even though the populist radical right has been more electorally successful in the last decade it has only achieved executive power in a few cases (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021). Hence, it is possible that nativists’ perceived status as long‐term losers in European politics is responsible for their relatively weak support for democracy. Our analyses show some support for this hypothesis. However, nativists are still less supportive of democracy also after controlling for their levels of specific support. Consequently, there seems to be a more fundamental opposition between nativism and support for democracy than earlier research suggests.

In a time when nativist parties have become part of the political mainstream and nativists constitute a substantial share of the electorates in contemporary Europe (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021), our findings may have important implications for research trying to understand threats to liberal democracy and waning democratic legitimacy. Such research does not, generally, find that support for democracy has declined in Western Europe over time (e.g., Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2020). But parties mobilising on a nativist agenda are relatively recent phenomena in West European politics. Now, when they are part of mainstream politics in many countries, it is possible that the ‘nativist divide’ in political support we have identified will have consequences as time goes by. The findings presented here generate questions that beg for answers, and thus call for more research on the link between the ideological underpinnings of the populist radical right and political support that moves beyond the narrow focus on populism that currently dominates comparative research.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the editors and the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments. This research was made possible by grants from the Research Council of Norway (grant number 275308) and the Swedish Research Council (VR 2018‐01468).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1. ESS models (Figures 1‐2)

Table A2. EVS OLS models (Figures 1‐2)

Table A3. EVS logit and OLS models (Figure 3)

Figure A1. Effect of nativism on perceived democraticness by country (ESS)

Figure A2. Effect of nativism on perceived democraticness by country (EVS)

Figure A3. Effect of nativism on importance to live in a democracy by country (ESS)

Figure A4. Effect of nativism on importance to live in a democracy by country (EVS)

Figure A5. Nativism and consequent support for democracy (EVS)

Figure A6. Nativism and support for authoritarian alternatives by country

Figure A7. Nativism and support for a strong leader (EVS)

Figure A7. Nativism and support for army rule (EVS)

Figure A9. Nativism and support for expert rule (EVS)

Figure A10. The effect of nativism on satisfaction with democracy over time

Table A4. Nativism and satisfaction with democracy in different ESS rounds

Table A7. Summary statistics ESS.

Table A8. Summary statistics EVS.

Table A9. Summary statistics ESS (all rounds).