Introduction

James Scott's The Moral Economy of the Peasant is a classic study of the politics of Asia's subsistence-oriented peasantry. The book opens with a graphic quotation from the historian Richard Tawney, describing the fate of peasants in China in the 1930s: “There are districts in which the position of the rural population is that of a man standing permanently up to the neck in water, so that even a ripple is sufficient to drown him” (Scott Reference Scott1976: 1). This precarious situation, Scott argues, informs a “subsistence ethic” which underpins peasant politics. A core component of this ethic is an aversion to the state, because its inflexible claims on peasant resources threaten to push rural households below the fluctuating water level of subsistence crisis. States are hungry for reliable sources of revenue and have little sympathy for the regular variations in hardship experienced by rural tax-payers. Peasants have a life-and-death interest in securing a minimum level of output for their own consumption and they regularly try to temper government demands through evasion, petition, protest and crime. They sing songs and recount tales that mock the greed of government officials. And when the pressures on their subsistence ethic become too intense, they rebel.

This underlying tension between peasant livelihood and state taxation is a prominent theme in Scott's subsequent work. In Seeing Like a State (Reference Scott1998) he explores the techniques that the modern state uses to make society fiscally legible. Modern systems of surveying and land tenure, for example, create a standardised and clearly demarcated rural landscape in which taxation responsibilities can be readily allocated to individual farmers and specific plots of land. Peasant modes of land management are, by contrast, multi-layered, overlapping and locally specific, bamboozling to administrators. In The Art of Not Being Governed (Reference Scott2009), Scott develops the argument further, adding a strong spatial dimension. He asserts that the uplands of Southeast Asia have been settled by people who have escaped from the fiscally accessible state space of the lowlands. Upland social organisation, settlement patterns, cultivation systems and non-literate culture all function to keep the state at a distance and avoid the lowland state-making projects of “slavery, conscription, taxes, corvée labor, epidemics, and warfare” (Scott Reference Scott2009: ix).

Scott's seminal work on state-society relations has been enormously influential, generating a rich array of studies on the strategies rural people have used in their struggles against extractive states. The concept of rural resistance remains influential, informing analyses of the political action of rural people against the combined threats of globalisation, neoliberalism and authoritarianism. However, in this article I argue that the relation between rural people and the state in Asia is no longer usefully understood in the terms that James Scott has so elegantly presented. There have been two fundamentally important changes that have transformed the peasantry and produced a very different relationship between peasants and the state. First, a large and growing number of peasants in Asia now stand well above the water level of subsistence crisis. Economic growth and livelihood diversification mean that rural poverty is declining rapidly throughout the region. This has created new political ethics, focused on productivity challenges and economic disparity rather than on securing a minimum standard of living. Second, the relationship with the state has shifted from taxation to subsidy. On balance, the state no longer makes demands on the farming economy; rather it subsidises it, helping to maintain rural livelihoods as the relative size of agriculture in the overall economy shrinks. Rather than being a threat to peasant livelihood, the state is increasingly a guarantor of it. Peasants no longer struggle to avoid the fiscal gaze of the state; instead they attempt to position themselves as favourably as they can as recipients of government largesse. The politics of legibility has been replaced by the politics of eligibility.

These are profoundly important changes, but they are often overlooked, especially when rural people themselves deploy the traditional rhetoric of exploitation in their political action. The central purpose of this article is to explore this fundamental transformation in state-society relations in rural Asia and reflect on some of its political implications. Whereas James Scott placed subsistence at the heart of the rural political dynamic, my principal emphasis is on productivity. As this paper demonstrates, the volume of produce or money entering or leaving the rural economy (via subsidy or taxation) is important, but in terms of the long term trajectory of the rural political-economy it is less important than the effect of this flow on agricultural productivity. I explore this intersection between taxation, subsidy and productivity by means of a comparative historical study of Thailand and the Republic of Korea (hereafter South Korea). This comparison is useful for two main reasons. First, the broad trajectories of change have been similar in both countries but the intensity of transformation has been very different. Like many other countries, both Thailand and South Korea have followed the path from taxation to subsidy but Thailand has never successfully addressed its legacy of low agricultural productivity. Contemporary South Korean agriculture, by contrast, is a result of a century-long investment in productivity improvement, in both its taxation and subsidy phases. Second, whereas South Korea has made a successful democratic transition, Thailand is experiencing a resurgence in authoritarian rule. A comparison of the similarities and differences in the political economy of their agricultural sectors suggests that one important reason for this difference in political outcomes is Thailand's inability to achieve a successful agricultural transition. Unlike South Korea, Thailand has failed to effectively manage the contemporary dilemmas of exchange between rural people and the state.

From Taxation to Subsidy

The work of agricultural economist Yujiro Hayami (Reference Hayami2007) provides an important framework for the argument I present in this paper and highlights the specificity of the rural situation described by James Scott. Hayami sets out three different agricultural problems, each characteristic of a different phase of economic development (Figure 1). Poor countries confront a “food problem”. Despite the large proportion of economic activity that is devoted to the production of food, low agricultural productivity, high population growth, and rapid urbanisation combine to create food shortages, driving up the cost of living, increasing wages and slowing industrialisation. The challenges of the food problem are often met by government intervention to lower the price of agricultural products. Export taxes are a common strategy, pushing domestic food prices below what is on offer on the international market. A more direct intervention is to force farmers to sell output to the government below market prices. Food aid provided by foreign governments or international agencies may also help to boost domestic supply and lower the prices local farmers receive. The net result is a transfer of value from the agricultural sector to other parts of the economy. The political dynamic in this stage of agricultural development is similar to that described by James Scott, with an extractive state exploiting peasant farmers in order to support industrial development.

Figure 1. The three stages of agricultural development (After Hayami Reference Hayami2007).

As countries develop, the food problem is gradually replaced by the disparity problem, introducing a very different political dynamic to that described by James Scott. Disparity emerges because productivity growth in agriculture is much slower than productivity growth in other parts of the economy. Agricultural productivity is constrained by ecological and climatic factors, whereas industry can benefit from the development and importation of transformational technology. Economies of scale are also much harder to achieve in agriculture, especially where small-holder farming predominates. The result is that “farmers' income level tends to decline relative to non-farmers’ corresponding to the widening inter-sectoral productivity gap” (Hayami Reference Hayami2007: 4). As inter-sectoral mobility increases, and modern communication systems become widespread, farmers become increasingly aware that they are being left behind and this “often becomes a significant source of social instability” (Hayami Reference Hayami2007: 4). In the disparity phase, governments are forced to recognise the political dangers of rural discontent and attempt to provide support to the agricultural sector rather than taxing it. However this fiscal transformation can be challenging in both economic and political terms. Governments in developing countries often lack the revenue to provide sufficient support to a still substantial agricultural sector in which economic and social aspirations have been awakened by modernisation. At the same time, efforts to direct funding into rural areas may be resisted by the expanding urban middle class who see agricultural subsidy as an illegitimate diversion of the taxes they pay.

The third problem is the “protection problem”. In advanced economies there can be a tendency for food over-supply, as population growth slows and “food consumption is saturated” (Hayami Reference Hayami2007: 3). International trade opens up new sources of food and traditional consumption items, such as rice, become less attractive to modern consumers. The result is downward pressure on farm income and further rural discontent. Governments are pressured to actively protect a rural economy under siege. On the positive side, the challenge of supporting agriculture can become easier to address as the relative size of agriculture in the total economy shrinks. Put simply, in high income countries, taxes collected from the large and expanding industrial and service sectors can be diverted to support the livelihoods of a diminishing population of farmers: “high-income consumers are lenient to high food prices and farm subsidies” (Hayami Reference Hayami2007: 3).

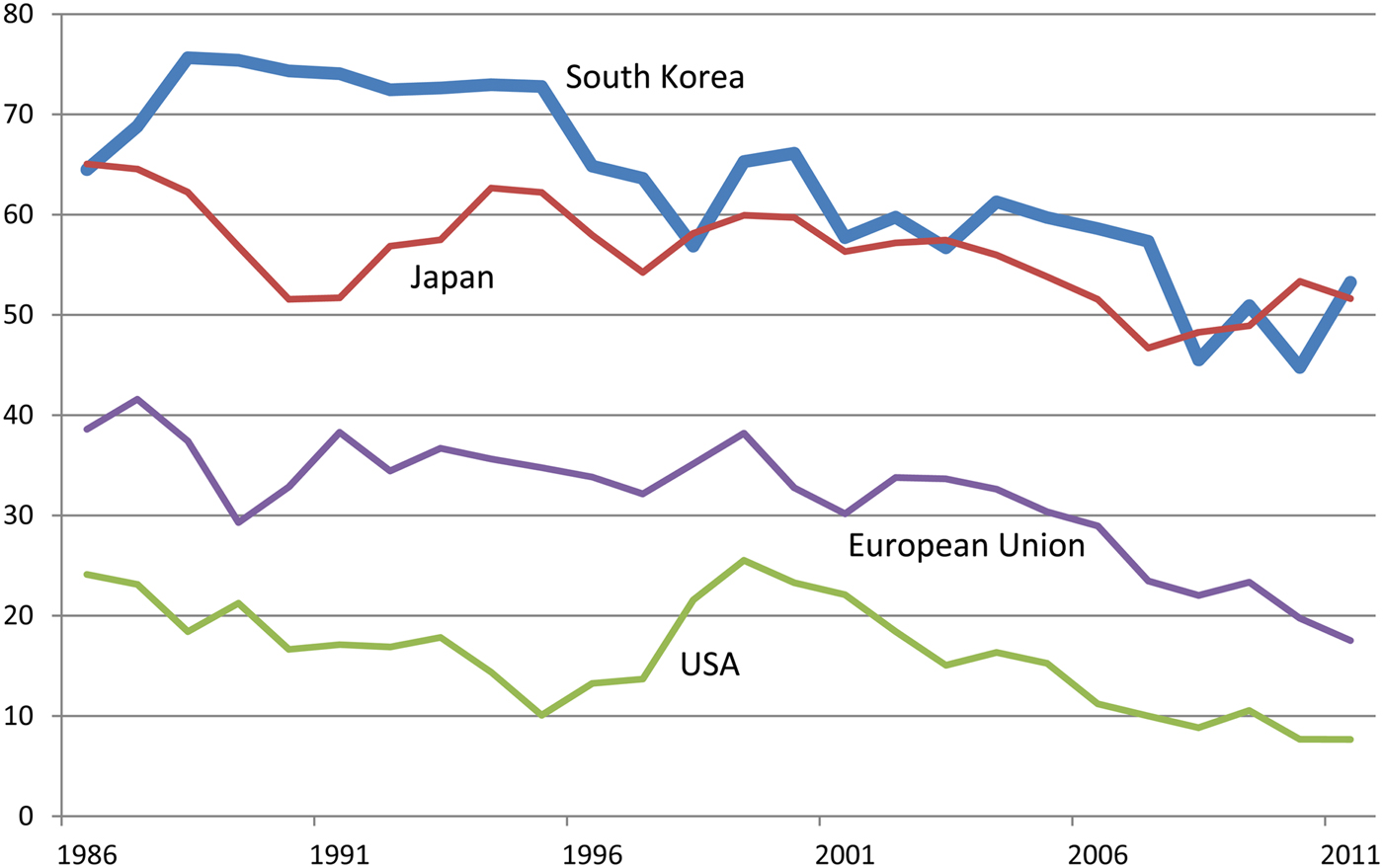

The net effect of these challenges, and government responses to them, is a long-term trend from taxing the agricultural sector to subsidising it. This trend has been observed throughout the world, and it is clearly present in Asian economies, albeit with different timing, pace and intensity. Table 1 is drawn from a major World Bank study of agricultural incentives, and sets out the nominal rates of assistance for agriculture in Asia. The nominal rate of assistance measures the extent to which the prices received by farmers for their products are higher (or lower) than the prices they would receive in the absence of any government intervention. Price support has been one of the most important ways in which Asian governments have assisted the agricultural sector. The overall picture is clear: in the 1950s, farmers in developing Asian countries received 27 per cent less for their crops than they would have without government intervention. This persisted into the 1980s, but started to shift in a much more benign direction. By the late 1990s, the average rate of assistance was positive, at 7.5 per cent. By the early 2000s this had increased to 12 per cent. Of course, there is significant variation within Asia. The advanced northeast Asian economies of South Korea and Japan are, by far, the most generous to their farmers having made the shift to subsidy much earlier than other countries in the region. China is much less generous, but has made a dramatic move from very heavy taxation to a modest level of support. In Southeast Asia there is a mixed picture, with Vietnam and the Philippines the most supportive of farmers, but all countries following a similar trajectory. South Asia demonstrates similar diversity in the extent of support to farmers but, again, the overall trend away from taxation is clear. Across the region, the politics of agricultural taxation has been superseded by the politics of subsidy.

Table 1. Nominal rates of assistance to agriculture (per cent) (Anderson Reference Anderson2008: Table 5).

In the following sections I explore this agricultural transformation in both Thailand and South Korea, focusing on the intersection between taxation, subsidy and agricultural productivity. These historical sketches draw attention to three important points. First, the economic conditions that gave rise to the subsistence ethic which Scott describes as underpinning peasant political action have been superseded. The majority of rural producers now sit well above the water-level of subsistence failure. Second, both Thailand and South Korea illustrate the region-wide trend from rural taxation to rural subsidy. This is dramatically evident in South Korea but the trajectory is also clear in Thailand. The political dynamic described by James Scott, based on state extractions from a subsistence-oriented peasantry, is no longer relevant. Third, and most important, the two histories show that while the shift from taxation to subsidy is politically important, what is more important is the intersection between government policy and agricultural productivity. In Thailand increases in agricultural subsidy have had the effect of maintaining a large and relatively unproductive rural sector, contributing to political instability and, ultimately, a reversion to authoritarian rule. South Korea's agricultural transition has been much more successful.

Thailand

The Origins of Low Productivity

In contrast to the colonial regimes in Burma and Indochina, on which James Scott based his analysis of peasant political action, the relationship between the Thai state and the rural economy during the first half of the twentieth century was one of benign neglect. The Thai state did not engage in concerted exploitation of the rural economy until the middle of the century. Before this, farmers were lightly taxed and peasant politics were relatively uncontentious. In the early 1900s, corvée requirements were abolished and replaced with a standard head tax (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 58). This caused some discontent, especially when local officials abused their position to extract excessive payment or labour service, but pre-modern flexibility and leniency in the collection of taxes persisted well into the modern era (Seksan Reference Prasertkul1989: 405). Farmers paid a combination of head tax and land tax, the mix changing over time and varying considerably throughout the country. Land tax was more prevalent in the central areas; head tax more common in the outlying provinces. Overall, the impact on farmers was modest. Carle Zimmerman's (Reference Zimmerman1931: 78) economic survey in 1930–31 found that tax payments represented only 5–7 per cent of rural household expenditure. The land tax was lowered by 20 per cent in 1932, given royal concerns about the impact of the depression (Seksan Reference Prasertkul1989: 478). Following the People's Party revolution in 1932, which brought the absolute monarchy to an end, rural taxes and charges were reduced even further in order to “make the farmers’ position easier” and abolished completely in 1939 (Hewison Reference Hewison1986: 42). Between 1900 and 1938 the land tax and head tax raised, on average, 20 per cent of the revenue of a fiscally weak state, declining to 13 per cent in the latter years (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 185).

There are various reasons why the Thai state was reluctant, or unable, to challenge farmers' subsistence ethic by imposing more exploitative rural polices. The outbreak of rebellions in both the north and northeast in the early 1900s – partly motivated by the new head tax and the abuses of officials – made the government cautious about increasing burdens on the peasantry (Seksan Reference Prasertkul1989: 406–7). Apart from internal security concerns, the royal government was well aware that neighbouring colonial powers may use rural uprisings as a basis for intervention and further territorial encroachment. Moreover, the French had no qualms about offering favourable tax treatment to attract settlers to move into the sparsely settled Lao territories. Within Thailand, treaty agreements placed limits on the level of land tax the government could charge, in order to protect British commercial interests (Larsson Reference Larsson2012: 38). The government also confronted the practical challenges of tax collection in a large country with an open land frontier. While reforms implemented in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century had created a nation-wide network of administration, the local reach of the state was still very limited. Tax evasion was widespread, and well into the second half of the twentieth century the government faced the challenge of “widely dispersed distribution and production units, lack of honest administration, and a general unwillingness on the part of the population toward voluntary compliance to tax laws” (Bertrand Reference Bertrand1969: 179). Confronted with the challenges of rural taxation, the government resorted to a readily available alternative: the expanding urban population, fuelled by the influx of Chinese immigrants. Government controlled opium sales were a particularly important source of revenue, generating about as much as the land tax and head tax combined between 1900 and 1940. In the mid-1940s, after the main rural taxes had been abolished, opium sales generated 21 per cent of government revenue (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 185). Other government charges – the gambling tax, the lottery tax, liquor excise – also fell heavily on the growing Chinese population: “The fact that the state's revenue could not be obtained mainly from the peasantry meant it had to rely on the economic activities of other classes in order to survive” (Seksan Reference Prasertkul1989: 409).

This benign fiscal relationship had a long-lasting effect on Thailand's rural political-economy. On the bright side, the Thai state succeeded in preventing rural unrest. Following the rebellions of the early 1900s there were no substantial uprisings until the communist insurgency of the 1960s and 1970s. Thailand experienced none of the Great Depression rural upheaval that arose in other countries in Asia (Brown Reference Brown2005: 112–3). There were, of course, the usual forms of evasion and protest. Regular representations were made by farmers to lower government imposts in times of natural disaster and to remove corrupt officials (Hewison Reference Hewison1986), but these expressions of discontent never coalesced into broad based movements for change. The government regularly responded to farmers' representations with welfare measures and concessions on tax collection. However the flip side of this fiscal leniency was the government's failure to improve agricultural productivity, positioning Thai agriculture on a low productivity trajectory that it has never escaped. In the first half of the twentieth century, Thailand achieved rapid growth in rice production – exports increased 140 per cent and local consumption more than doubled (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 38, 46, 53) – but this was achieved by means of a massive increase in the area cultivated, rather than by any improvement in production techniques. In fact, agricultural productivity went backwards: average yields declined by 30 per cent between 1906 and 1950. The decrease was most dramatic in the northeast (42 per cent between 1920 and 1950), as a result of the massive expansion of cultivation onto less fertile land (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 48–50). Labour productivity also went backwards, with per-capita rice production declining 1.36 per cent per year between 1921 and 1941 (Feeny Reference Feeny1982: 24).

Thailand's low level of investment in irrigation was an important reason for its poor performance on agricultural productivity. In the early 1900s a major irrigation expansion program was shelved because railway construction, in the interests of military and administrative consolidation, took priority: “irrigation may have been very desirable, but it was not absolutely critical to the maintenance of the established order in early twentieth-century Siam” (Brown Reference Brown1988: 41). Reluctance to levy additional charges on farmers and treaty limits on land tax constrained both the funding available for irrigation works and the additional revenue that could be derived from them (Brown Reference Brown1988: 39; Larsson Reference Larsson2012: 38–9). By the late 1940s, only about 12 per cent of Thailand's rice growing land was irrigated (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 44, 276). Investment in other aspects of productivity improvement was also unimpressive (Feeny Reference Feeny1982: Chapter 4). The end result of the state's disinterest was that cultivation techniques in Thailand were much the same in the 1950s as they were in 1900:

“It is certainly true that the government did not give enough active and constructive attention to the problem of agriculture. It did little or nothing to improve the methods of cultivation and seed selection; it did nothing to improve the marketing structure or to standardize the quality of the grades of rice; it did not study soils and crops; nor did it effectively perform the function of informing the farmers about prices and marketing alternatives. Much more could have been accomplished in all these things, and without very large expenditures, too.” (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 87, emphasis in the original)

In brief, the political dynamic described by James Scott took on a particular form in Thailand in the first half of the twentieth century. The subsistence ethic was largely unchallenged and state extractions were relatively benign. As a result, subsistence agriculture was preserved, state intervention was very modest, and agricultural productivity declined. State action didn't push farmers below the water level of subsistence failure but, at the same time, it did little to improve the standard of rural livelihoods.

The Shift to Rural Taxation

As a major exporter of rice since the mid-nineteenth century, Thailand has never faced an extended food problem in the simple sense of food shortage. Consistent production surpluses have meant that Thailand has been a major rice exporter since the second half of the nineteenth century. However, around the middle of the twentieth century, rice pricing became a focus of government policy in order to meet two basic objectives: to increase government revenue and “to hold down the cost of living in urban areas” in order to secure low wages in the “infant industrial sector” (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 255). Starting in the 1950s, these linked policy objectives were achieved by placing a heavy tax burden on the country's farmers, moving Thailand into the first of Hayami's three phases of agricultural political-economy.

Following World War II, direct government intervention in the rice trading system had the effect of “reversing the pre-war policy of reducing the tax on the farmer” and placed an “extremely heavy” tax burden on them (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 92). The rice premium introduced in 1955 was the most important and long-lasting intervention. The premium was an export tax on rice which generated government revenue, lowered the domestic price of rice and reduced the returns received by farmers. During the 1950s it comprised between 11 per cent and 17 per cent of total government revenue (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 246). In 1966 it cost farmers 13 times as much as their direct tax commitments (Bertrand Reference Bertrand1969: 179). One study from 1965 suggested that the farm gate price of rice would increase by up to 80 per cent if the premium was abolished (Usher Reference Usher and Silcock1967: 220–223) while another suggested a more modest rise of between 23 and 59 per cent for the decade leading up to 1972 (Feeny Reference Feeny1982: 113). This was a politically attractive ‘tax’ for the government to impose because it operated indirectly and the disproportionate tax burden on farmers was virtually invisible. While it generated considerable debate among Thai economists, there is no evidence that it encouraged any sustained protest from farmers despite the significant effect it had on their levels of income.

The rice premium was not politically volatile in the short term but it had long-term political implications because it compounded Thailand's core agricultural problem: low productivity. As a result of the artificially low rice price many farmers were discouraged from investing in new production technology. This is particularly evident in relation to fertiliser use which remained extremely low, well into the 1960s. Under the price structure created by the rice premium “the application of fertilizer [was] simply uneconomical” (Bertrand Reference Bertrand1969: 181). In Thailand, one kilogram of nitrogen fertiliser cost the equivalent of 6.7 kilograms of un-milled rice whereas in Japan it cost only 1.4 kilograms of rice (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 256). As a result, Thailand had one of the lowest rates of fertiliser use in Asia. Of course, during this period there were some improvements in agricultural technology. These included expanded irrigation, greater use of farm machinery, and modest uptake of improved rice varieties. However, Thailand's overall performance was lacklustre. Between 1960 and 1975, Thailand's rice yield increased by only 10 per cent, compared to 26 per cent in Malaysia, 28 per cent in South Korea, 34 per cent in the Philippines and 49 per cent in Indonesia.Footnote 1

Tackling the Disparity Challenge

During the 1960s in Thailand there was growing concern that communist insurgencies in neighbouring Indochina would spill over into Thailand. An impoverished rural population was seen as being vulnerable to communist influence, a fear compounded by the presence of active rebel groups in some parts of the country. Fearing an outbreak of active peasant resistance, the government started to invest in building up the peasantry as the “backbone of the nation” (Haberkorn Reference Haberkorn2011: 52). The first National Social and Economic Development Plan (1961–1966) set out a programme of investment in rural infrastructure, research, extension, and credit that would “improve the social system of farmers so that they have a higher standard of living and better welfare, are unified, industrious and cooperate more with the government.” (National Economic Development Board 1964: Chapter 6). National commitment to investment in rural development was further encouraged by the brief period of open democratic government and political polarisation in the first half of the 1970s. Politically assertive farmers' organisations, including the Peasants' Federation of Thailand, moved onto the national stage campaigning for debt relief, rent control and land redistribution. Backed by student groups, political organisation among the peasantry flourished. Communist successes in Indochina, and an upsurge of clashes with insurgents in Thailand itself, made the Thai state even more determined to win over rural hearts and minds.

This increase in rural activism, of the sort that Scott and other scholars of rural resistance have documented, drove a fundamental change in the fiscal relationship between the state and rural society, quickly shifting the actions of the Thai state in a more supportive direction. As a result of changes implemented since the 1970s, government tax and trade policies no longer significantly reduce the crop prices received by farmers. They now operate to raise farmer income above the level they would receive in an unregulated market. In 1974 the impact of the rice premium meant that farmers received about half of what they would have received for their rice on the open market. Since then, the impact of the premium has declined steadily. By the early 1980s it made a negligible contribution to government revenue and in 1986 it was abolished completely (Walker Reference Walker2012: 50). Around this time the government introduced the first of its rice ‘mortgage’ schemes under which farmers could receive income by pledging their rice to the government rather than having to sell it for low post-harvest prices. If the market price rose above the pledging price, farmers could then sell for the higher amount. These schemes have become a central feature of modern Thailand's politics of agricultural subsidy. They expanded greatly, and became much more generous, under the administration of Thaksin Shinawatra (2001–2006) when the government-supported price was often set 20 or 30 per cent higher than the prevailing market price (Benchaphun et al. Reference Ekasingh, Sungkapitux, Kitchaicharoen and Suebpongsang2007: 47). The most generous price-support scheme was introduced by Thaksin's sister, Yingluck Shinawatra, after her election in 2011. Under this very controversial scheme – which contributed to the anti-Thaksin military coup of May 2014 – the government paid farmers up to 50 per cent above the market price for their rice. The subsidy was reported to represent about 10 per cent of government expenditure, amounting to 1.8 per cent of GDP (Warr Reference Warr2013). Price support is also provided for some other important crops (Anderson and Valenzuela Reference Anderson and Valenzuela2008). Since the early 1990s, import restrictions have meant that farmers receive a 30 per cent premium on soybeans. This is particularly important for lower income farmers for whom soybeans are a relatively inexpensive, low maintenance and soil-restoring cash crop. Sugar prices are also supported, averaging around 10 per cent higher than free market prices since the 1980s and peaking at 80 per cent under the Thaksin government.

Over the past four decades, government action on a range of other fronts has directed resources into rural areas. Direct government spending on agriculture has increased more than fifteen-fold in real terms since 1960, more than half of it in a belated effort to expand irrigation. In the 1960s, government spending on agriculture represented about 4 per cent of agricultural GDP, while in the 1990s it averaged 14 per cent, falling back to 11 per cent in the 2000s (Alpha Research, various years; National Statistics Office, various years). Rural development schemes have also played an important role in supporting the rural economy. The Accelerated Rural Development Program was established in 1966 with an initial focus on irrigation and highway construction, especially in the northeast, in order to prevent the spread of communism. It developed into a wide-ranging and well-resourced rural development programme. In 1975 the Subdistrict Development Program was established to distribute infrastructure budgets directly to local government units, “permanently and significantly alter[ing] government-village relations in Thailand” (Fry Reference Fry1983: 51). This scheme was expanded in the 1980s and others followed, some of them locally coordinated by a nationwide network of community development offices established in 1977. Major schemes included the Rural Development Fund (1984), the Poverty Alleviation Project (1993), and the so-called Miyazawa Scheme (1999), funded by the Japanese government to help mitigate the impacts of the Asian financial crisis. Funding for the long-standing Accelerated Rural Development Program tripled during the 1990s (National Statistics Office, various years). The Thaksin government's high profile and brilliantly marketed local development schemes were a continuation of this long established trend of state investment in the rural economy.

These initiatives – alongside substantial government investment in agricultural credit, rural infrastructure, health and education – have made an important contribution to reducing absolute poverty in rural Thailand. State action has raised agricultural prices, supported diversification into higher-value crops, improved market access, and provided a wide array of employment opportunities in state-funded infrastructure and rural development projects. The impact on poverty has been dramatic. In Thailand in the 1960s, poverty was near universal, with an estimated 96 per cent of the rural population living below the poverty line (Warr Reference Warr and Warr2004: 49). Now, the percentage living below the nationally defined rural poverty line is about 17 per cent (with only 4 per cent living below US$2 per day) (World Bank 2013). In rural Thailand, average incomes in 2007 were 3.2 times the national poverty line; for landowning farmers the ratio was 2.8; for tenants it was 2.7 and for agricultural workers, the most vulnerable group in the rural economy, it was 2.2 (Walker Reference Walker2012: 41). Thailand's performance on other indicators is equally impressive: infant mortality has declined from about 10 per cent in 1960 to about 1 per cent; secondary school enrolment has increased from 18 per cent (1971) to 72 per cent; and about 95 per cent of the rural population have access to clean drinking water (World Bank 2013). Most farmers in Thailand are now living well above the subsistence margin.

However, to the extent that the shift from taxation to subsidy has been aimed at addressing disparity (that is, relatively poverty rather than absolute poverty) it has been much less successful. As Hayami's model suggests, many developing countries face the challenge of a widening gap between rich and poor, but Thailand's performance is particularly bad and shows little sign of improving. Since the mid-1980s, Thailand has been more unequal than its main regional neighbours. The United Nations Development Program 2010 report, Human Security, Today and Tomorrow: Thailand Human Development Report 2009, highlights the regional dimensions of this inequality, which extends well beyond income. According to a range of human development indicators of income, health, education, and housing, Bangkok and its hinterland perform very strongly whereas the worst performers are predominantly rural provinces in the northeast, north, and far south. Average household income in Bangkok is about three times higher than in the rural north and northeast. The Human Development Report shows that, compared to those in and around Bangkok, residents of rural provinces are significantly more likely to be sick or disabled, have much less access to health services, attend school for about three years less, have lower standards of housing, and have less access to mobile phones and the Internet. Although the national (and rural) poverty rate has declined dramatically, poverty is still about ten times more prevalent in the north and northeast than it is in Bangkok.

An important reason for Thailand's poor performance on disparity has been that the overall impact of state support for rural Thailand has been to help develop and maintain the rural sector rather than fundamentally transform it. This can be readily illustrated by examining some macroeconomic data. In the 1950s agriculture made up about 50 per cent of Thailand's GDP (Feeny Reference Feeny1982: 108). This has declined to about 12 per cent. Of course, this does not reflect an absolute decline in Thailand's agriculture (the value of overall production is now five times greater than it was in 1960); rather it is a reflection of much more rapid growth in the industrial and service sectors. The agricultural workforce has also declined, but much more slowly than agriculture's share of GDP. In the 1950s, about 80 per cent of the workforce was in agriculture (Feeny Reference Feeny1982: 22); by 2010 this had fallen to about 46 per cent. In short, Thailand now has more than 40 per cent of its workforce producing a little more than 10 per cent of its GDP. The large difference between these two figures shows that Thailand has failed to escape from the low productivity trajectory that it embarked on in the first half of the twentieth century and it demonstrates that improving productivity, rather than securing subsistence production, is now Thai agriculture's core challenges.

In terms of Hayami's three-stage agricultural development schema – whereby nations move from addressing the food problem to the disparity problem and then to the protection problem – Thailand remains stuck in the disparity phase. Large increases in government subsidy and support have certainly contributed to a massive reduction in absolute poverty in rural areas but successive regimes have struggled to deal effectively with economic disparity. Instead, government spending has helped to maintain a very large and unproductive rural sector. Since Thaksin Shinawatra came to power in 2001, government spending on agricultural support has become highly politically contentious. Thaksin and his allies achieved electoral dominance on the basis of support from the large rural population, but this shift in electoral weight and government spending towards rural areas has been bitterly contested by Thaksin's rivals in the elite who have successfully marshalled support in the urban middle class. This opposition culminated in military seizures of government in both 2006 and 2014. Achieving a political consensus on investment in protection for the agricultural sector is likely to be impossible while it remains so numerically large.

South Korea

The Origins of South Korea's Productivity Growth

South Korea's very different rural experience in the first half of the twentieth century goes a long way towards explaining why its modern agricultural development has been very different to that of Thailand. Geography is one reason for the difference: South Korea has a less favourable climate than Thailand and much less land that is suitable for agricultural cultivation. In the early 1900s population density in Korea was 147 per square kilometre and the mountainous terrain placed severe limitations on the area of arable land. By contrast, in land-rich Thailand there were 16 people per square kilometre in the early 1900s and the land frontier persisted into the early 1990s (Ingram Reference Ingram1971: 46; Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 40). The second important difference was political: after decades of growing Japanese influence, Korea became a formal colonial possession of Japan in 1910. Whereas in Thailand the effect of colonial pressures and constraints was to limit state extractions from the peasantry, in Korea, colonial exploitation was a defining feature of the rural political-economy.

In the period preceding colonial rule, Korea's ruling Choson dynasty had struggled to collect agrarian taxes, largely due to the power of local aristocrats (Kohli Reference Kohli and Woo-Cumings1999: 98). This quickly changed under the colonial administration. In the years leading up to formal annexation, the Japanese achieved early success in increasing revenue from land tax. With the addition of other new sources of revenue, government receipts jumped 300 per cent between 1905 and 1911 (Kohli Reference Kohli and Woo-Cumings1999: 109). Between 1910 and 1918 the Japanese put in place a comprehensive survey of agricultural land, rendering the landscape legible, to use Scott's term, in order to increase agricultural taxation, backed by an extensive enforcement apparatus. Land tax collection virtually doubled between 1910 and 1920 and, up until the 1930s when taxes from industry became rose rapidly, it contributed about 30 per cent of the colonial state's revenue (Shin Reference Gi-Wook1996: 42).

Even more important than rural taxation, was the re-orientation of Korean agriculture towards export. Thailand's position as a major rice exporter was well established in the 1870s, as a result of mid-nineteenth century treaty provisions with western powers. In Korea, the rice export boom started later. In 1918, food riots in Japan prompted the colonial administration to use Korea as a source of rice. Exports to Japan came to account for about forty per cent of Korean rice production (Shin Reference Gi-Wook1996: 93). Japanese agricultural policy relied heavily on landlords to drive increases in production and direct output into the export market. Colonial action reinforced unequal landlord-tenant relations and encouraged the acquisition of large holdings by Japanese investors (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 77–79). Rents were typically around one half of total output while in some major rice growing areas around eighty per cent of the crop was handed over to the landowners (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 82). The holdings of large landlords contributed about 60 per cent of Korea's rice exports (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 79). Despite increasing production, per-capita consumption of rice declined almost 30 per cent between 1915 and 1935 and more than 60 per cent of tenant farmers were regularly unable to meet basic subsistence requirements (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 83, 87). No wonder rice exports were sometimes referred to as “starvation exports” (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 88).

Unsurprisingly, given the profound challenges to farmers' subsistence ethic, rural politics in Korea was much more volatile during this period than it was in Thailand. Tenancy was the basic mechanism used to extract production from the peasantry, thus landlord-tenant relations were the most important axis of political action. In a detailed study of peasant protest in the colonial era, Gi-Wook Shin identifies three phases of conflict. From 1920 to 1926 tenant movements were “not simply defensive reactions of desperately poor tenants” (Shin Reference Gi-Wook1996: 64). Instead they reflected the desire of poor and more affluent tenant farmers to gain a better share of the rapidly expanding rice-trading economy. The depression-era disputes from 1927 to 1932 were much more similar to those described by James Scott: “defensive struggles by poor tenants to ward off starvation and landlord eviction – that is, to preserve subsistence” (Shin Reference Gi-Wook1996: 73). Following growing concern about the rural impoverishment, the colonial government moved to redress some of the imbalance in landlord-tenant relations (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 89). The Rural Revitalisation Campaign (1932–1940) which sought to improve tenant livelihoods and strengthen village level organisations was an important precursor to more farmer-friendly policies adopted by the South Korean government in the second half of the century (Shin and Han Reference Gi-Wook, Do-Hyun, Shin and Robinson2000). Shin argues that in the post-depression 1930s, many landlord-tenant disputes “resembled individual law suits” as tenants “exploited new colonial policy opportunities, particularly legal measures to protect tenant rights and reduce landlord power” (Shin Reference Gi-Wook1996: 131). Rural discontent become much less visible in the repressive years of the World War II and exploded in a series of brutally repressed outbursts following the defeat of the Japanese.

How did Korea's productivity performance compare with that of Thailand during the first half of the twentieth century? In the early colonial period, increases in production were achieved, as in Thailand, by increasing the area of cultivation. Irrigation and drainage facilities were improved and non-productive lands were brought under cultivation: “the first stage of developing in the Korean agriculture was to promote extensive farming” (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 74). Up until the mid-1920s there were only very modest improvements in yield. However from the mid-1920s, Japanese development efforts increasingly focused on technical improvement with the adoption of new forms of cultivation, improved varieties and an increase in fertiliser use (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 74). Agricultural techniques developed in Japan were introduced to Korea, in part to ensure that Korean rice was acceptable on the Japanese market (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 91). Between 1915 and 1940 the percentage of land using improved seed doubled (to 85 per cent) and there was a one-thousand per cent increase in fertiliser use (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 77). Subsidies and loans were provided to land-owners to undertake land improvements (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 74). The impact of this decade of investment in agricultural innovation was substantial: by the latter half of the 1930s land productivity had increased 54 per cent since 1915 and labour productivity had increased by 68 per cent (Suh Reference Sang-Chul1978: 73), a stark contrast to Thailand's history of productivity decline over a similar period.

The Post-War Food Problem

During the first half of the twentieth century Korea's food problem was a product of Japanese demand. The primary mechanism for addressing it was landlordism, with rice extracted from producers in the form of rent and directed to the export market. After liberation from the Japanese in 1945, both the nature of the food problem and the means of addressing it changed. Meeting domestic demand, at affordable prices, became the central preoccupation. Unlike Thailand, South Korea faced very real food supply challenges, especially given the post-war repatriation of more than one million Koreans, refugee inflows from the north and an increase in consumption following the relaxation of war-time controls (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 235). Like Thailand, the objective was to meet this supply challenge while maintaining low prices in order to keep wages in the expanding industrial sector low (Honma and Hayami Reference Honma, Hayami, Anderson and Martin2009). This low-price objective formed a central component of what has been described as an “industrialize first, invest in agriculture later” approach (Han Reference Seung-Mi2004: 73).

The comprehensive land reform of 1950 virtually eliminated the landlord class, meaning that new forms of intervention were required to meet the government's agricultural objectives. As in Thailand, the primary strategy pursued was direct government intervention into the rice market. Immediately after World War II the US Military Government experimented with a free market approach but this led to rising prices and supply bottlenecks. As a result, a system of compulsory rice collection was put in place, similar to a system adopted by the Japanese in the latter years of colonial rule (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 235–236). The Grain Management Law, introduced in 1950, reaffirmed the power of the new South Korean government to intervene in the market in order to obtain grain from farmers, manage supply and manipulate prices. During the 1950s, government purchases represented about 10 per cent of total grain sales, while in the 1960s the average level increased to 20–25 per cent (Honma and Hayami Reference Honma, Hayami, Anderson and Martin2009: 93–94). These government purchases represented a tax on farmers and “contributed in a major way to rural poverty,” as the prices paid to farmers were consistently lower than market prices and, up until the 1960s, even lower than the farmers' cost of production (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 239–240).

Of course, the downside of low prices was that farmers had little incentive to expand their production, potentially compounding the food problem and, ultimately, driving up prices. The South Korean government addressed this supply challenge by relying on grain imports. In the early 1950s substantial imports – approaching 20 per cent of domestic production in 1953 – increased local supply and suppressed prices paid to South Korean farmers (Moon Reference Moon1974: 389). In the mid-1950s, the ‘Public Law 480’ scheme was introduced whereby South Korea received food aid from the United States. This involved the substantial import of non-rice grains, amounting to almost 10 per cent of total grain production in the second half of the 1950s (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 239) and 15 per cent during the 1960s (Kim and Joo Reference Dong-hi and JooYong-jae1982: 32). These grain imports helped to keep domestic prices low and also reduced the pressure on the government to increase production by offering farmers higher prices.

Campaigning Against Disparity

South Korea's shift from preoccupation with the food problem to the disparity problem occurred at about the same time as in Thailand, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As early as 1961 the Farm Products Prices Maintenance Law had been passed in order “to maintain proper prices of agricultural products to insure the stability of agricultural production and the rural economy” (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 239–42) and it prompted some increase in government rice purchase prices. Soon after taking power in 1961, President Park Chung Hee also took action against ‘usurious’ debts in rural areas and in the First (1962 to 1966) and Second (1967 to 1971) Five Year Plans the government invested in rural support schemes such as land improvement, irrigation, mechanisation, and expanded fertiliser production. Generally, however, the policy settings adopted under Park's leadership during the 1960s were unfavourable to agriculture and industrialisation was the main priority. The 1967 presidential election was one trigger for change, with the unsuccessful opposition candidate winning a majority of votes in rural areas on the back of a promise of higher rice prices (Han Reference Seung-Mi2004: 73). At the same time, government concerns about possible reductions in food aid prompted the development of better incentives for farmers to increase production. In 1969 the “complete reversal in rural policy” (Moore Reference Moore1985: 585) from taxation to subsidy was clearly evident when Park's government adopted a dual pricing system, whereby rice and barley were purchased from farmers for a price higher than it was sold to consumers. Government prices paid to farmers increased more rapidly than the prices farmers paid for non-farm goods, and the percentage of rice acquired by the government also increased. In 1975 farmers were receiving 14 per cent more for their rice than consumers paid for it (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 243–247). The government covered the difference, as well as transportation and storage costs. This was an expensive scheme and by the mid-1970s “the expanding scale of the government deficit due to the two-price system has emerged as one of the serious constraints on farm price policy” (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 250). Nevertheless, the policy shift was successful in increasing production and “narrowing the income gap between the farm and the non-farm sectors” (Kim and Joo Reference Dong-hi and JooYong-jae1982: 32).

As in Thailand, the government combined price support with increasing investment in rural development. The Third Five Year Plan (1972–1976), which explicitly aimed to achieve “equitable income distribution” between urban and rural sectors, increased rural investment four-fold (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 188). It supported large-scale irrigation projects and land reclamation schemes, increased farm mechanisation and promoted new rice varieties (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 188–191). The highest profile initiative in this era was the Saemaul Undong (New Community) scheme which was put in place in 1973. Through a nationwide scheme of village-level mobilisation the government supported infrastructure construction, housing renewal, and the establishment of health and welfare programs. Farmers were supported with low-cost credit and generous subsidies for agricultural inputs, especially fertiliser. As critics have pointed out, Saemaul Undong had a strong ideological and propaganda component but it also succeeded in increasing the living standards of participating farmers, by one account lifting them to equivalence with urban areas (Douglass Reference Douglass2013: 3).

Maintaining Protection

As time went on, the government's shift from taxation to subsidy was combined with trade protection. In the 1980s, South Korean manufacturers were increasingly exposed to international trade, while protection for the agricultural sector – in the form of both tariffs and quotas – was increased: “The producer prices of farm products were raised far above border prices by means of quantitative import restrictions on most agricultural commodities” (Honma and Hayami Reference Honma, Hayami, Anderson and Martin2009: 95). This agricultural trade protection has become a central component of state-society relations and South Korean farmers are now amongst the most protected farmers in the world. Since the 1980s this has been achieved by limiting agricultural imports. An array of trade restrictions and tariffs have meant that South Korean farmers are paid much more for their crops than they would in an unregulated market (Anderson and Valenzuela Reference Anderson and Valenzuela2008). The impact of this has been dramatic: since 1990 rice farmers have received, on average, 260 per cent more for their rice than they would have without government protection. For beef, the protection premium has been 150 per cent, and for barley an astonishing 420 per cent. The average for all products over the period has been 170 per cent. On top of trade protections, South Korean farmers receive direct payments under a range of rural development, price support, income support, and disaster relief schemes (Il Jeong Jeong Reference Jeong2008).

South Korea has been under international pressure to reduce the level of support it provides to farmers. Under the Uruguay round of international trade negotiations, South Korea agreed to replace quantitative import restrictions on agricultural products with tariffs by 1997. The one exception was rice, where South Korea agreed to gradually relax quantitative import restrictions (Il Jeong Jeong Reference Jeong2008: 24). South Korea also agreed to reduce tariffs from an average of about 60 per cent to below 40 per cent over 10 years (Honma and Hayami Reference Honma, Hayami, Anderson and Martin2009: 95). Alongside this multilateral reform, Korea has also pursued a series of free trade agreements, with eight currently in place (including, most notably, with the United States) and another ten or so in train. The effect of this trade liberalisation has been substantial with a clear downward trend in levels of support for agricultural products (Figure 2). Unsurprisingly this has generated very vigorous political opposition from South Korean farmers, who have staged regular high-profile protests against free trade arrangements. The government has responded to this new phase of rural political mobilisation with a series of expensive structural adjustment measures aimed at improving the competitiveness of South Korean agriculture and providing income support for farming households (Il Jeong Jeong Reference Jeong2008: 27–28). As a result, South Korea remains a world leader in protecting its farmers, consistently outstripping most other OECD countries (Figure 2), with government support contributing more than half of the gross receipts of farmers (OECD 2012a: 38).

Figure 2. Percentage of Producer Support to Agriculture (OECD 2012b).

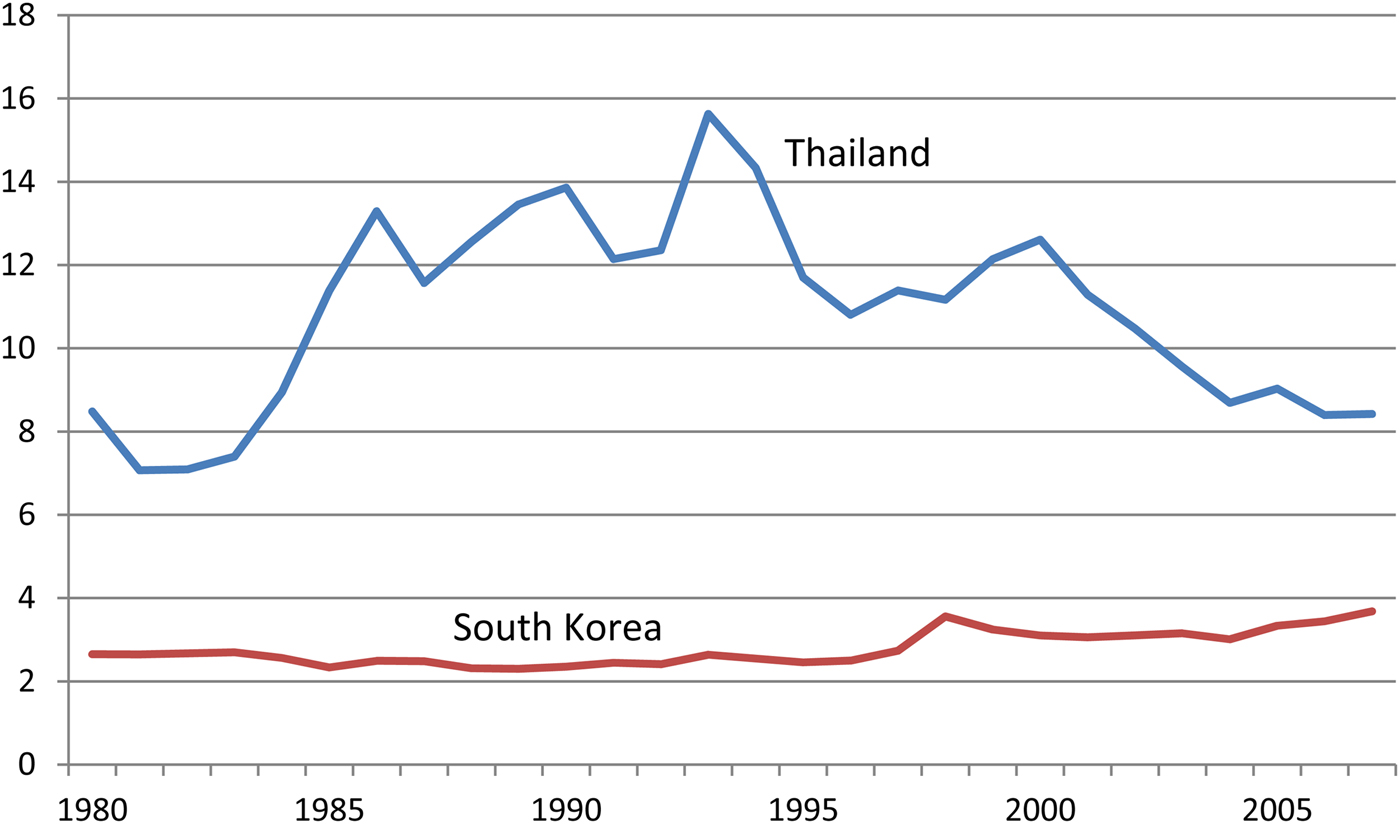

Thailand will never be able to offer this level of support to its agricultural sector without very substantial economic restructuring. When South Korea became a high income country in the mid-1990, agriculture represented about 6 per cent of its GDP and 12 per cent of its workforceFootnote 2 . This has since declined to 2.7 per cent of GDP and 6.6 per cent of the workforce. The contrast to Thailand – where about 10 percent of GDP is produced by more than 40 per cent of the workforce – is striking. It is about forty years since agriculture in South Korea accounted for such a large percentage of the workforce (Ban et al. Reference Hwan, Moon and Perkins1980: 14). In Thailand, the agricultural workforce was growing in absolute terms up until about 1990 whereas in South Korea it peaked in the mid-1960s. Importantly, South Korea's transition from agricultural taxation to agricultural subsidy has been accompanied by a dramatic improvement in agricultural productivity: labour productivity in agriculture increased by more than 800 per cent between 1980 and 2011. In Thailand, the increase over the same period was only 93 per cent. This is directly relevant to the issue of disparity. In South Korea, the ratio between labour productivity in industry and labour productivity in agriculture (a key driver of disparity, in Hayami's terms) has averaged about three in the period since 1980. In Thailand the disparity ratio has been much more dramatic, averaging more than eleven (Figure 3). In short, South Korea's very generous rates of agricultural subsidy have been possible given its creation of a small and productive agricultural sector, in the context of a rapid increase in national economic prosperity. South Korea's new agricultural challenge is to maintain productivity growth and workforce renewal in the face of a rapidly ageing rural population.

Figure 3. Ratio between GDP per worker in industry and GDP per worker in agriculture (derived from World Bank World Development Indicators).

Politics, Subsidy and Productivity

James Scott's influential account of rural political action in Southeast Asia placed peasants' subsistence ethic at the centre of analysis. Peasants living close to the subsistence margin were profoundly concerned with how much of their production was left over after landlords and state officials had taken their share. According to the subsistence ethic, demands by landlords or the state that left peasant households with insufficient food to survive in a socially acceptable manner were likely to generate resistance and rebellion. Rural politics was ultimately about the level of peasant production and how that production was shared between the peasant household and extractive outsiders.

This rural political dynamic has changed fundamentally. For a great many peasants, levels of production have increased to such a level that the subsistence ethic is no longer politically salient. At the same time, the state is now a source of subsidy rather than an enforcer of taxation. This is a much more affluent dynamic than Scott described but it is no less political. Indeed, there is good evidence that economic growth increases rural political vigour, as farmers make increasingly assertive demands on governments that are increasingly capable of responding to them (Anderson Reference Anderson, Anderson, Hayami and Mulgan1986). South Korea's high income farmers are regarded as some of the most radical and organised in the world, staging passionate protests to extract direct payments from government as trade protections are wound back. In Thailand, the middle-income rural population has relied heavily on electoral mobilisation and protest rallies to defend its populist relationship with the governments of Thaksin Shinawatra and his allies (Walker Reference Walker2012). Thaksin certainly did not invent rural subsidy, but his clever packaging of it attracted strong support from rural voters, securing six successive electoral victories for the Thaksin forces between 2001 and 2014. In both Thailand and South Korea protesting farmers invoke the imagery of pre-modern serfdom, but these are thoroughly modern political tussles, reflecting the long-term shift from taxation to subsidy. Rural politics is no longer principally about the sharing of production between the household and the tax collector; rather it is about how tax payers and consumers can supplement the incomes of rural producers.

There are two aspects of this new political relationship that I want to highlight in this final section. The first is the shift in focus from legibility to eligibility. James Scott's work has powerfully documented the strategies used by the pre-modern and modern state to render the population and the landscape fiscally legible. He has also shown how rural populations resist this fiscal gaze by avoidance, subterfuge, outright cheating, and maintaining local arrangements that are difficult for the taxing state to understand. This is the contested politics of legibility.

A concern with eligibility, however, draws attention to very different forms of political behaviour motivated by an ethic of engagement with the state rather than avoidance of it. The new political objective for rural populations is to be highly visible to the gaze of the state in order to be recognised as legitimate recipients of state support. Modern rural populations are active participants in these projects of eligibility. This often alarms civil society commentators, who remain committed to a sense of autonomy from the state and who worry about the incorporation of rural people into the modern state's development agendas. Often, the rural development schemes that have been a key element in the shift from taxation to subsidy are interpreted as being part of the state's drive to create a manageable social and economic landscape, installing new forms of disciplinary power and surveillance into rural communities. Of course they are. But these schemes also provide rural people with the opportunity to present themselves as appropriate recipients of government support. Deploying new ethics of political engagement, rural people form committees, develop project proposals, perform public rituals, raise funds and mobilise labour. They do this in order to make themselves legible to the state and, more importantly, to demonstrate that they are eligible recipients of the state's financial support. In this process of mutual recognition, the rural community has been transformed from a site of resistance to a site of collaboration with the state in the implementation of its development agenda.

The second important element in this new rural political-economy is the shift in the focus of political contestation from production to productivity. In Hayami's terms this is the shift from the food problem to the disparity problem. The food problem is about the absolute level of production, and being able to supply urban consumers without forcing up prices. It's a national version of the peasant living up to his neck in water with fluctuations in supply or price having potentially dire political consequences. In Thailand this production challenge was met by using abundant land resources to expand production and using market intervention to suppress prices. In Korea, there was some expansion in the area of cultivation but, given limited land resources, increases in the productivity of land and labour also played a part. Most important in colonial-era Korea was the use of landlords to extract a substantial share of rice production, compromising peasant subsistence in order to meet metropolitan demand. In post-war South Korea, the response was similar to that of Thailand: government intervention in the market (combined with grain imports) meant that farmers received low prices for their production. In both Thailand and Korea the production of the peasant household was taxed in order to meet national food challenges.

The emergence of the disparity problem shifts attention away from the level of food production to the relative productivity of agriculture and other sectors of the economy. Disparity emerges as countries expand their overall production and rise above the water level of subsistence necessity. It results from the fact that productivity within agriculture increases more slowly than productivity in other sectors of the economy. This shifts the political dynamic away from the quite specific circumstances of exploitation that underpin Scott's accounts of the relationship between the state and rural society. Farmers become less concerned about how their produce is shared with the state, and much more preoccupied with their performance in relation to other sectors of the economy. As Partha Chatterjee (Reference Chatterjee2008: 125) notes, modern rural politics is preoccupied with discrimination rather than exploitation. At the same time, rising living standards and increasing tax revenue from industry mean that the government is less preoccupied with keeping food prices low and, at the same time, more able to provide support for the relatively unproductive farming sector. State-society tussles over the distribution of agricultural production are replaced by arguments about the best way to address productivity-driven disparity.

Despite following a broadly similar transition from taxation to subsidy, the records of Thailand and South Korea on agricultural productivity have been very different. To a significant extent, this is a legacy of their contrasting experiences in the first half of the twentieth century. In Thailand, agriculture was treated with benign neglect. There was a light taxation burden, very little political tension and limited state investment in improving agriculture. In Korea, exploitation, political unrest and state investment interacted much more productively, creating an agricultural sector in which output from both land and labour was considerably higher than it had been at the start of the century. In the second half of the century, Thailand achieved increases in production largely by increasing inputs, rather than by using them more productively. State investment has improved agricultural incomes and supported diversification but it has not been accompanied by a fundamental transformation in the agricultural sector. The result is a large agricultural workforce that is much less productive than the workforce in other sectors of the economy. South Korea's record on productivity in the second half of the twentieth century has been much more impressive. Building on the turbulent and exploitative productivity achievements in the first half of the century, state support for agriculture since the late 1960s has been accompanied by very rapid productivity growth and, most importantly, a dramatic transfer of labour out of the agricultural sector. As Hayami and others have shown, high levels of support for the agricultural sector are economically and politically possible when it has shrunk to be a modest proportion of the overall economy.

Thailand now finds itself in a difficult situation as a result of its lacklustre performance on rural transformation and agricultural productivity. It has a large and electorally powerful proportion of the population still engaged in the agricultural sector. The political dominance of Thaksin Shinawatra and his allies has been based on strong electoral support in the predominantly rural northeast and north of the country. Thaksin successfully targeted this large portion of the electorate with crop price support, low-cost credit, local economic development programs and affordable health care. In a context of relatively low productivity and limited economic opportunity, rural people value state subsidy and it forms an important component of rural livelihoods (Walker Reference Walker2012). Thaksin and his allies have been electorally rewarded for responding to rural aspirations, building a system of political dominance based on productivity disparity. The problem for Thailand is that this politics of rural eligibility has been more electorally compelling than longer term and transformational investments in productivity improvement and socio-economic restructuring. Yingluck Shinawatra's highly controversial, but electorally popular, rice price support scheme is a good example: it was a highly expensive program that encouraged investment in a relatively low value agricultural commodity. Although it came at a huge cost, it did nothing to transform the structure of the rural economy.

This subsidy-based symbiosis between elected governments and the rural electorate has become a destabilising force in Thai politics. Thaksin's rivals within the Thai elite have been threatened by the electoral power of rural voters and the fiscal impact of the subsidies directed towards them. Whereas in South Korea structural transformation has produced a broad political consensus in favour of protecting a small and relatively productive rural sector, the large size of Thailand agricultural population has generated a much more volatile political dynamic. Unable to defeat Thaksin's electorally dominant political machine, built on a foundation of rural disadvantage, his opponents have increasingly adopted non-democratic strategies. Tapping into middle-class discomfort about the level of government support for farmers, anti-Thaksin forces have been able to build a powerful oppositional discourse linking electoral politics with irresponsible populism, government corruption and money politics. This anti-electoral backlash to Thaksin's rural popularity culminated in electoral boycotts by the main opposition party in 2006 and 2014, delegitimising both elections. In both cases this paved the way for military intervention displacing Thaksin himself in 2006 and his sister's government in 2014. This cycle of instability and authoritarian revival is likely to continue as long as political parties can achieve electoral dominance on the basis of a large and relatively unproductive agricultural sector that makes only a modest contribution to Thailand's GDP. Transition to a more politically stable protection phase, as has been achieved in South Korea, will require sustained productivity growth and structural transformation.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the Institute of East Asian Studies at Sogang University for inviting me to the workshop (at which James Scott was the guest of honour) that inspired this Thailand-Korea comparison. I would also like to thank David Gilbert for assisting with the research for this paper. Michael Montesano provided very valuable comments on an earlier version of the paper, as did two anonymous referees.