1 Introduction

Text classification is widely used in various applications (Minaee et al. Reference Minaee, Kalchbrenner, Cambria, Nikzad, Chenaghlu and Gao2021),Footnote 1 and conventionally required both a significant amount of manual labeling and a strong understanding of machine learning methods. Recently, large language models (LLMs), like ChatGPT, have all but eliminated this barrier to entry due to their ability to label documents without additional training, an ability known as zero-shot classification (Burnham Reference Burnham2025; Gilardi, Alizadeh, and Kubli Reference Gilardi, Alizadeh and Kubli2023; Rytting et al. Reference Rytting2023; Ziems et al. Reference Ziems, Held, Shaikh, Chen, Zhang and Yang2024). LLMs have thus received widespread adoption within political and other social sciences.

Yet, despite their convenience, there are strong reasons why researchers should hesitate to use LLMs. The most widely used and best-performing models are proprietary, closed models. Historical versions of the models are not archived for replication purposes, and the training data is not publicly released. This puts their use at odds with open science standards. Further, these models have large compute requirements, and also charge for their use, making labeling datasets of any significant size expensive. We echo the sentiments of Palmer, Smith, and Spirling (Reference Palmer, Smith and Spirling2024): Researchers should strive to use open-source models and provide compelling justification when using closed models. However, even among open models, such as Llama 3 (AI@Meta 2024), the compute and storage requirements make them unwieldy for archiving and journal replication.

We aim to narrow this gap between the advantages of state-of-the-art LLMs and the best practices of accessible and open science. Accordingly, we present the Political Domain Enhanced BERT-based Algorithm for Textual Entailment (DEBATE) family of language models. The models are trained specifically for zero- and few-shot classification of political text. With only 150–435 million parameters, the DEBATE models are not only a fraction of the size of proprietary models with tens of billions of parameters, such as Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic 2024), but are comparable zero-shot classifiers of political documents. We further demonstrate that the DEBATE models are few-shot learners without any active learning scheme: A simple random sample of only 10–25 labeled documents is sufficient to teach the models complex labeling tasks when necessary.

We accomplish this in two ways: First, we adopt the natural language inference (NLI) classification framework. This allows us to train encoder or embedding models (e.g., BERT) for zero-shot and few-shot classification. Using these models for classification tasks is advantageous because they are more efficient at creating semantic representations of text than generative models (Neelakantan et al. Reference Neelakantan2022). Second, we use domain-specific training with tightly controlled data quality. By focusing on a specific domain, the model size necessary for high performance is significantly reduced.

This approach is not without drawbacks. NLI classifiers do not offer the same flexibility of an LLM that can follow detailed instructions and provide exposition justifying its classification. Further, the massive model size and training corpus of LLMs mean they will generalize to a wider set of tasks. However, researchers often need to classify documents for relatively simple, well-defined concepts or train a supervised classifier. In such instances, the DEBATE models can be highly effective zero-shot classifiers, or foundation models for few-shot and supervised classification.

Additionally, we release the PolNLI dataset used to train and benchmark the models. The dataset contains over 200,000 English language political documents with high-quality labels from a wide variety of sources across all sub-fields of political science. Finally, in the interests of open science, we commit to versioning both the models and datasets and maintaining historical versions for replication purposes. We outline the details of both the data and the NLI framework in the following sections.

2 Natural Language Inference: What and Why

NLI (also known as textual entailment) is a universal classification framework. A document of interest, known as the “premise,” is paired with a user-generated statement, known as the “hypothesis.” Given a document and hypothesis pair, an NLI classifier is trained to determine if the hypothesis is true, given the content of the document. For example, we might pair a tweet from Donald Trump: “It’s freezing and snowing in New York—we need global warming!” with the hypothesis “Donald Trump supports global warming.” The model then returns a true or false classification for the hypothesis—in this case, true. Because most classification tasks can be framed in this structure, a single language model trained for NLI can be a universal classifier and label documents for many tasks without additional training.

NLI classifiers have recently gained traction among political scientists. Laurer et al. (Reference Laurer, Van Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2024) demonstrated their efficiency and superior performance in supervised settings. Earlier, Halterman et al. (Reference Halterman, Keith, Sarwar and O’Connor2021) and Lefebvre and Stoehr (Reference Lefebvre and Stoehr2023) showed their effectiveness for zero-shot event classification. However, the general-purpose NLI classifiers developed by Laurer et al. (Reference Laurer, van Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2023) and others are relatively less accurate than state-of-the-art generative LLMs (Burnham Reference Burnham2025). Our work demonstrates that, when trained on domain-specific data and tasks, NLI classifiers can achieve state-of-the-art performance in a zero- and few-shot contexts.

The advantage of the NLI framework is that it can be done with an “encoder” or an embedding model. These are fundamentally more efficient classifiers than the “decoder” architectures used by generative LLMs. Encoders, such as BERT and the DeBERTa architecture that DEBATE leverages,Footnote 2 are trained for a single task: to “encode” a representation of a word or document’s semantics in a dense vector known as an embedding (Neelakantan et al. Reference Neelakantan2022). Smaller neural networks are then appended on top of encoders so that the embeddings they produce can be used for classification or other tasks. When fine-tuned, encoders are taught to make more accurate semantic representations for the domain or task they are trained on.

Decoders that generate text, however, serve the opposite function. Rather than encoding semantics into a vector, they start with vectors from an embedding model and use those vectors to predict the next word. This process of using vectors to generate text is known as decoding. To be useful, a decoder must be able to respond to complex prompts that specify the task and the range of acceptable responses. They are therefore trained on a wide variety of tasks (e.g., classification, summarizing, and programming) and domains (e.g., politics, medicine, history, and pop-culture). This makes them flexible models, but much of the knowledge contained in their weights is superfluous to a particular request and very large models are required to follow an arbitrary range of prompt instructions consistently (Burnham Reference Burnham2025). Although LLMs have impressive capabilities in zero-shot settings (Ziems et al. Reference Ziems, Held, Shaikh, Chen, Zhang and Yang2024), they are inherently inefficient for any particular classification task. Thus, while an encoder model with 150 million parameters can be trained for zero-shot classification by learning NLI, decoder language models achieve zero-shot classification by learning hundreds or thousands of tasks and the smallest capable models have 7–8 billion parameters (e.g., Burnham Reference Burnham2025; Wei et al. Reference Wei2022). In practical terms, this is the difference between a model that can classify hundreds of documents per second on a modern laptop, and one that can classify ten documents per second on a discrete GPU.

3 The PolNLI Dataset

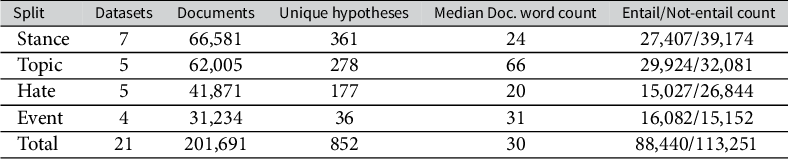

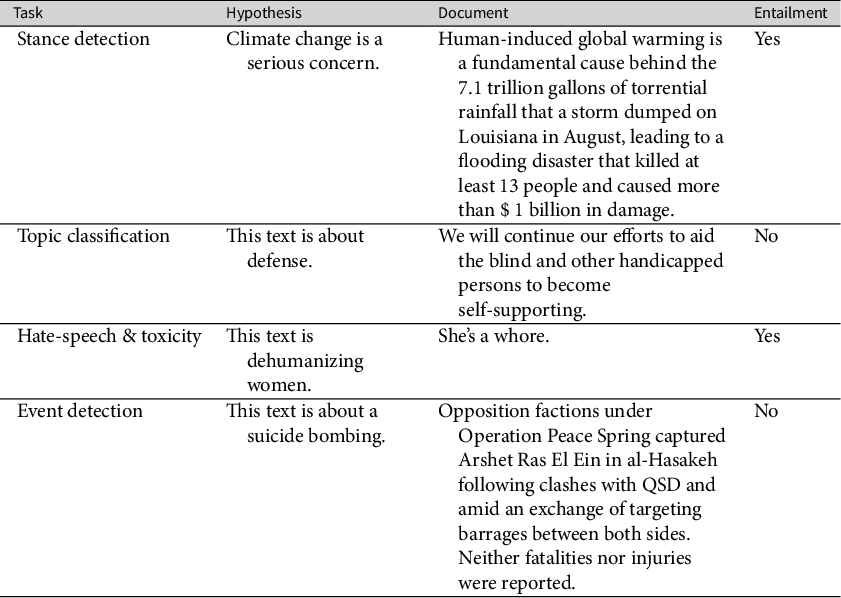

To train our models, we compiled the PolNLI dataset—a corpus of 201,691 English documents and 852 unique entailment hypotheses. The dataset contains four classification task categories: stance detection (or opinion classification), topic classification, hate-speech and toxicity detection, and event detection. Table 1 presents the number of datasets, unique hypotheses, and documents collected for each task. PolNLI contains a wide variety of sources, including social media, news articles, congressional newsletters, legislation, crowd-sourced responses, and more. We also adapted several multi-use datasets, such as the Supreme Court Database (Spaeth et al. Reference Spaeth, Epstein, Martin, Segal, Ruger and Benesh2023), by attaching case summaries to the dataset’s topic labels. In constructing the dataset, we prioritized both the quality of labels and the diversity of data sources. Our data construction process is described in the next sections.

Table 1 Dataset statistics across different tasks.

3.1 Collecting and Vetting Datasets

We identified 48 potential datasets from replication archives, the Hugging Face hub, academic projects, and government documents. Section A of the Supplementary Material contains a complete list of datasets. Several were compiled by authors for research projects, while others—like the Global Terrorism Database (START 2022) and the Supreme Court Database (Spaeth et al. Reference Spaeth, Epstein, Martin, Segal, Ruger and Benesh2023)—were adapted from public datasets. We also compiled several new datasets to address gaps in the training data. We qualitatively assessed each dataset by reviewing the scope of its documents and the collection and labeling process. We then omitted datasets based on assessments of quality and redundancy with other sources.

3.2 Cleaning and Preparing Data

To clean the data, we removed superfluous information from documents that the models might learn to associate with a particular label. This includes aspects like news outlet identifiers in article headings or event records that start each entry with a date. No edits were made to document formatting, capitalization, or punctuation in order to maintain variety in the training data.

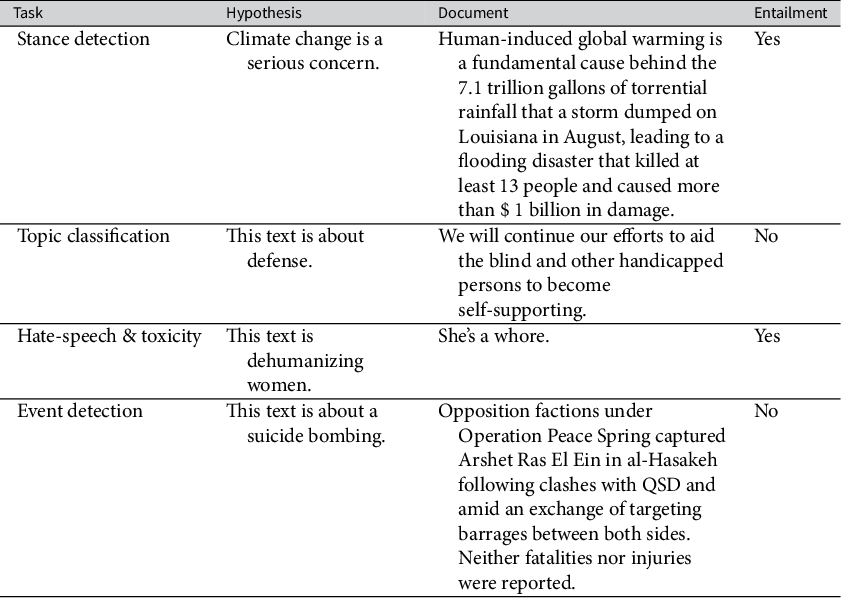

For each unique label in the data, we manually created a hypothesis that correlated with that label. For example, documents labeled for topics or events might be paired with the hypothesis “This text is about (topic/event type)” and documents labeled for stance might be paired with the hypothesis “The author of this document supports (stance)” or “(Topic) is a serious concern.”

Finally, each document–hypothesis pair was assigned an entail/not entail label based on the label from the original dataset. For example, a document labeled as expressing concern over global warming could be paired with the hypothesis “Climate change is a serious concern” and be assigned the “entail” label.Footnote 3

One challenge with this approach is that the topic and event data only contained positive entailment labels—datasets we adapted contain labels for what documents are about, not what they are not about. For example, an event summary labeled as a terrorist attack might be paired with the hypothesis “This document is about a terrorist attack,” and this would be true for all documents paired with this hypothesis. However, we also wanted to train the model to recognize what is not a terrorist attack. To accomplish this, if a dataset needed negative cases, we duplicated the documents and randomly assigned one of the other topic or event hypotheses, and then assigned a “not entail” label. One concern is that documents can contain multiple topics, and might be assigned a topic they are related to by chance. This is addressed through the validation process outlined in the next section. Table 2 shows example hypotheses for each task.

Table 2 Example hypotheses and documents for each task.

3.3 Validating Labels

The accuracy of labels is critically important to training and validating models. Because the collected datasets used many labeling approaches with varying levels of rigor, we wanted to take additional validation steps to ensure high-quality labels were retained in our data. To meet this objective, we leveraged the much larger language models, GPT-4 and GPT-4o (OpenAI 2023).

Recent research has shown that LLMs are as good, or better, than human coders for similar classification tasks (Burnham Reference Burnham2025; Chang et al. Reference Chang2024; Gilardi et al. Reference Gilardi, Alizadeh and Kubli2023). We therefore used these LLMs to reclassify each collected document with a prompt containing an explanation of the task and the entailment hypotheses we generated. A template for the prompt is contained in Section H of the Supplementary Material. We then removed documents where the human labelers and the LLM disagreed.Footnote 4 To ensure the LLMs generated high-quality labels, we took a random sample of 400 documents labeled by GPT-4o and manually reviewed them. We agreed with the GPT-4o labels 92.5% of the time, with a Cohen’s

![]() $\kappa $

of 0.85. Of the 30 documents where there was disagreement, 16 were judged to be reasonable disagreements where the document could be interpreted either way. The remaining 14, or 3.5% of documents, were labeled incorrectly by the LLM.

$\kappa $

of 0.85. Of the 30 documents where there was disagreement, 16 were judged to be reasonable disagreements where the document could be interpreted either way. The remaining 14, or 3.5% of documents, were labeled incorrectly by the LLM.

3.4 Hypothesis Augmentation

An ideal NLI classifier will produce identical labels if a document is paired with synonymous hypotheses (e.g., “This document is about Trump” and “This text discusses Trump” should yield similar classifications). To make our model more robust to various phrasings researchers might use, we presented each hypothesis to GPT-4o and prompted it to write three synonymous sentences. We manually reviewed the generated hypotheses and removed any insufficiently similar in meaning. Each document was then randomly assigned an “augmented hypothesis” from a set containing the original hypothesis and the generated alternatives. Finally, we manually varied hypotheses by randomly substituting a few common words with synonymous words (e.g., text/document and supports/endorses). This increased the number of unique entailment phrases to 2,834.

3.5 Splitting the Data

To split the data into training, validation, and test sets, we proportionally sampled from each of the four tasks to construct testing and validation sets of roughly 15,000 documents each. The rest of the data were allocated to the training set. The validation set consists of roughly 10,000 documents with hypotheses that are not in the training set and 5,000 documents with hypotheses that are in the training set. To ensure the test-set evaluates zero-shot classification performance, it only contains documents where neither the original hypothesis nor their synonymous LLM-generated variants, are in the training and evaluation sets.Footnote 5 These splits allow us to both estimate the model’s zero-shot capabilities during testing, and accurately track performance during training.

4 Training

The foundation models used as the starting point for training were four language models fine-tuned for general-purpose NLI classification by Laurer et al. (Reference Laurer, van Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2023). The models were trained in two different sizes (base and large) and two different architectures (DeBERTa V3 and ModernBERT) (He et al. Reference He, Liu, Gao and Chen2021; Warner et al. Reference Warner2025). Our results in the main paper focus on the DeBERTa models because they perform better and work with a wider variety of hardware and software environments. However, for those with access to an Nvidia GPU and a Linux environment, the ModernBERT models offer a 2–5 times speed increase. Benchmarks for ModernBERT models are in Section B of the Supplementary Material.

We used these models for a number of reasons: First, the DeBERTa V3 architecture performs best on NLI tasks among transformer language models of this size (Wang et al. Reference Wang2019), and the ModernBERT architecture offers unparalleled speed and memory efficiency for large datasets (Warner et al. Reference Warner2025). Second, using models already trained for general-purpose NLI classification efficiently leverages transfer learning. Before we re-trained the model, they were trained on five large NLI datasets, and 28 smaller text classification datasets. This means the models already understood the NLI framework and general classification tasks, allowing it to more quickly adapt to the specific task of classifying political texts (Laurer et al. Reference Laurer, Van Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2024).

We used the Transformers library (Wolf et al. Reference Wolf2020) to train the models and monitored progress with the Weights and Biases library (Biewald Reference Biewald2020). After each epoch (an entire pass through the training data), model performance was evaluated on the validation set and a checkpoint of the model was saved. We selected the best model from these checkpoints using both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The model’s training loss, validation loss, F1, accuracy, and hypothesis stability (see Section E.3 of the Supplementary Material) were reported for each checkpoint. We tested the best models according to these metrics by examining performance on the validation set for each of the four classification tasks, and across each of the datasets.

Finally, we qualitatively assessed the models by examining their behavior on individual documents. This included introducing minor edits or rephrasings of the documents or hypotheses so that we could identify models with stable performance that were less sensitive to arbitrary changes to features like punctuation, capitalization, or synonymous word choice. Hyperparameters used during training are in Section I of the Supplementary Material.

5 Zero-Shot Classification

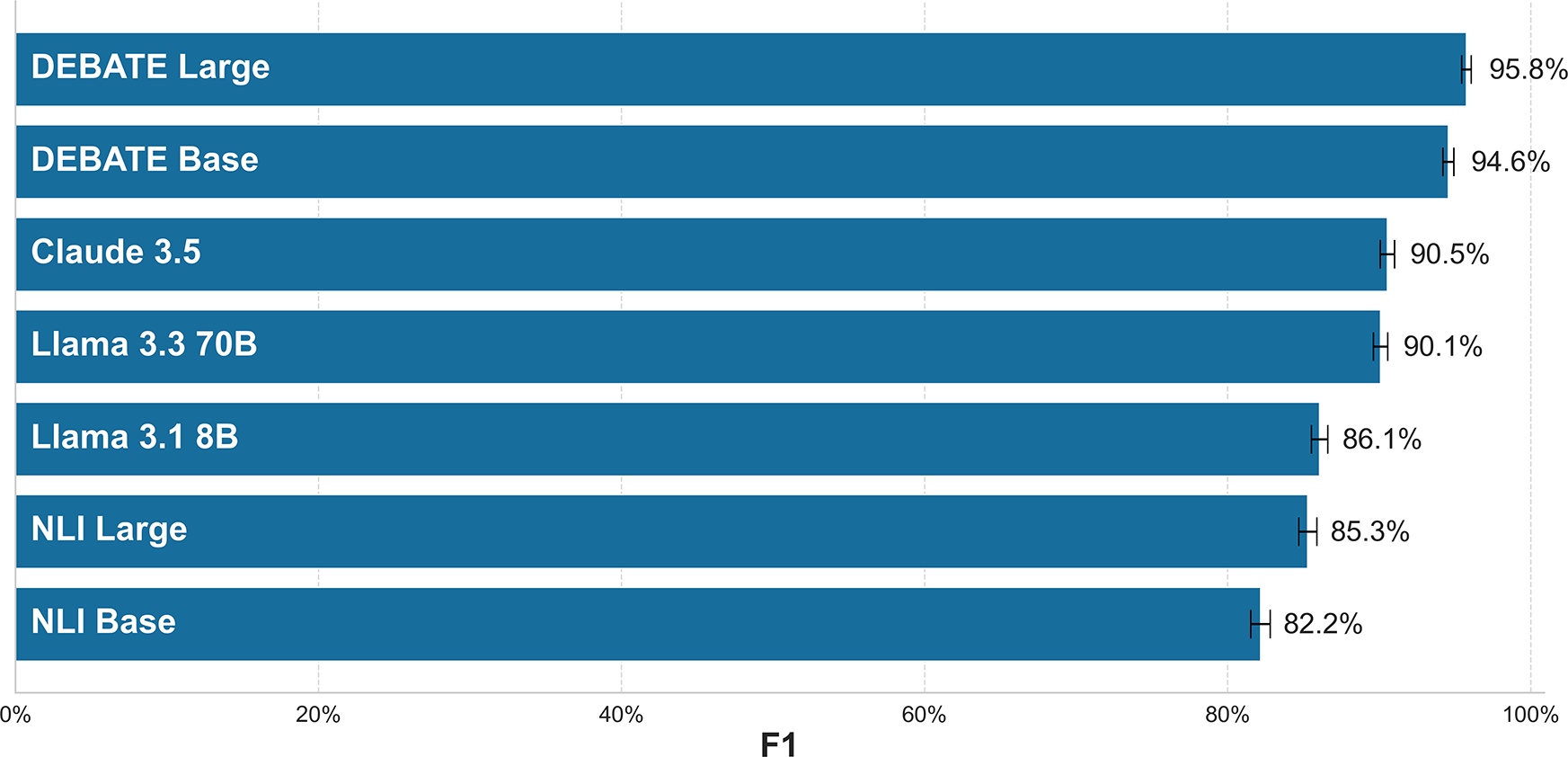

We benchmark our models on the PolNLI test set against five other models representing a range of options for zero-shot classification. The first two models are the DeBERTa base and DeBERTa large general-purpose NLI classifiers, which are currently the best NLI classifiers publicly available (Laurer et al. Reference Laurer, van Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2023). We also test Llama 3.1 8B, an open-source generative LLM (AI@Meta 2024). This is the smallest version of Llama 3.1 released and represents a generative LLM that can feasibly be run on a single local GPU while maintaining good classification performance. Finally, we benchmark two LLMs that are too large to run on local hardware: Llama 3.3 70B and Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic 2024). The former is an open-source LLM that is both affordable and near state-of-the-art, and the latter is a proprietary LLM that is widely considered among the best models available (Syed et al. Reference Syed, Light, Guo, Huan Zhanga, Ouyang and Hu2024). Notably, we do not include GPT-4o in our benchmark as it was used in the validation process from which the final labels were derived. We use weighted F1, expressed as a percentage, as our primary performance metric.

In addition to the results shown here, we present additional benchmarks in the appendices. This includes performance on four datasets of political documents omitted entirely from the PolNLI data (Section E.1 of the Supplementary Material) and performance on non-political documents (Section E.2 of the Supplementary Material). We find broadly similar results across tasks.

5.1 PolNLI Test Set

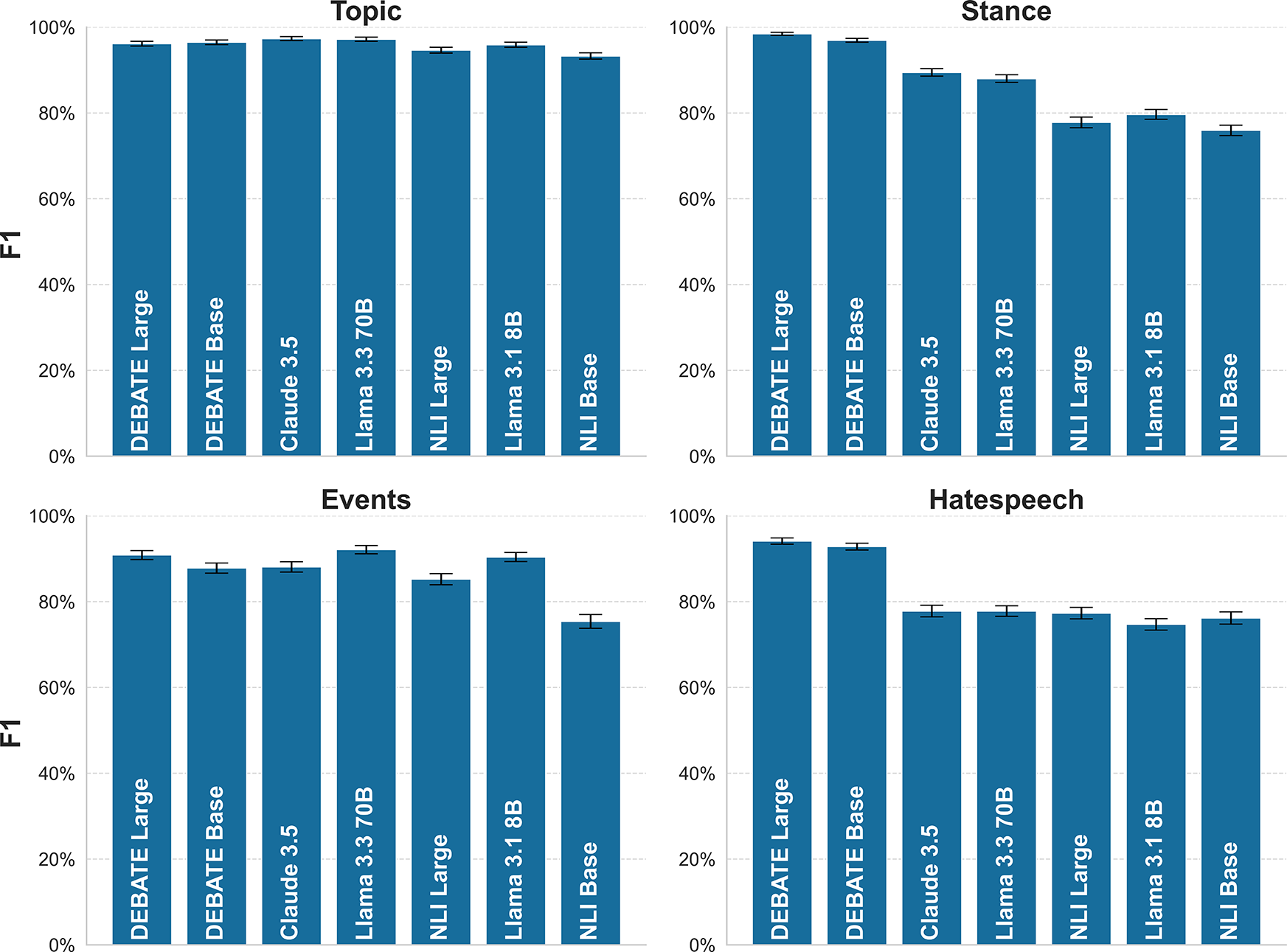

Figure 1 plots performance with bootstrapped standard errors across all four tasks for each model. We observe that the DEBATE models perform better than alternatives when all tasks and datasets are combined.

Figure 1 Zero-shot performance for all test set documents.

Figure 2 shows performance across our four tasks: topic classification, stance detection, event detection, and hate-speech identification. While all models perform well on topic classification, significant gaps emerge for other tasks. The DEBATE models perform significantly better than the other models on stance detection. On event detection tasks, we see comparable performance between the DEBATE models and the three generative LLMs, Claude, Llama 3.3, and Llama 3.1. Perhaps the most notable gap in performance is on the hate-speech detection task—the DEBATE models perform significantly better than the other models. We think this is likely because hate-speech is a highly subjective concept and our models are better tuned to the particular definitions used in the datasets we collected.

Figure 2 Zero-shot performance by task.

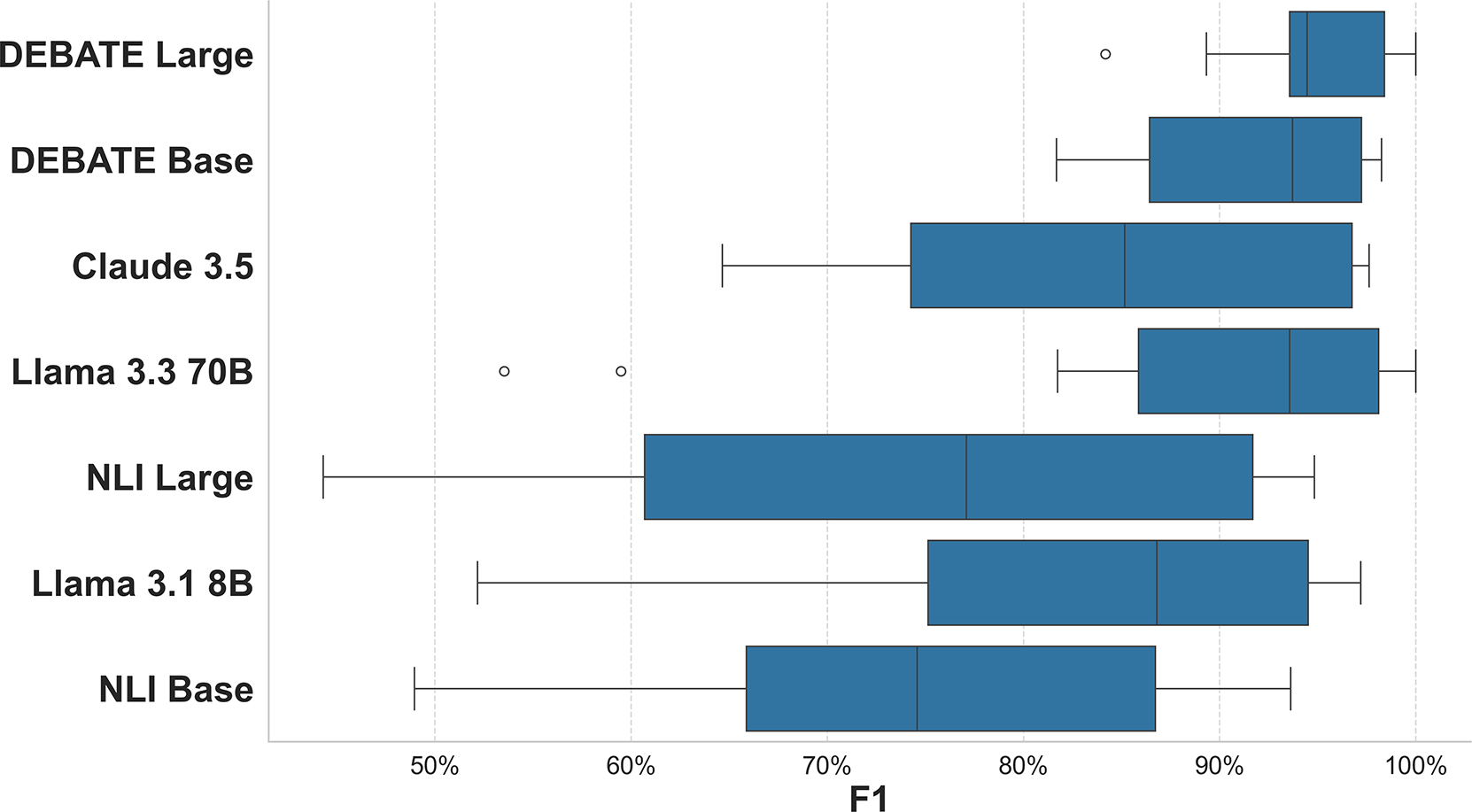

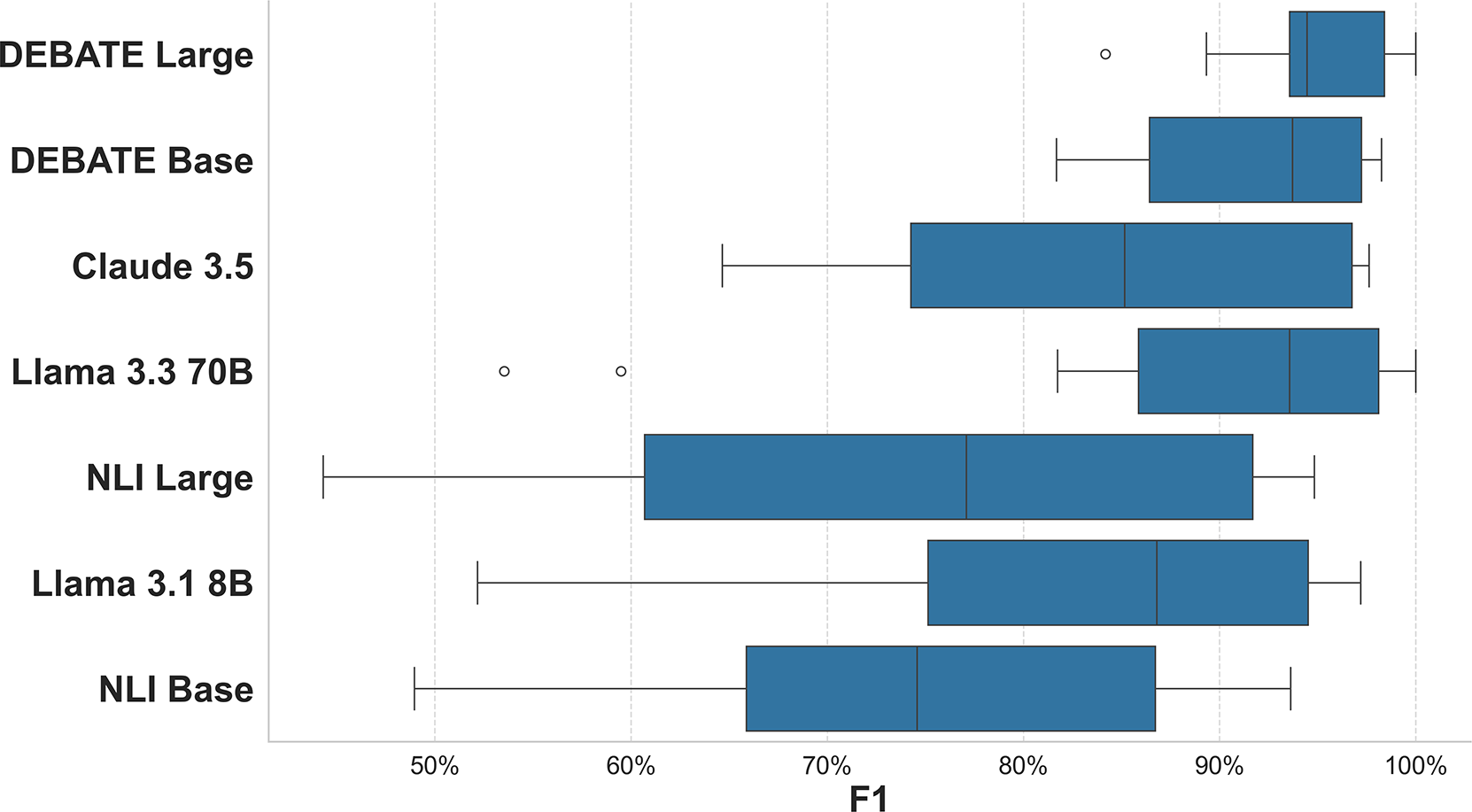

Finally, Figure 3 shows the distribution of performance across all datasets in the test set. We again observe that the DEBATE models consistently perform better than alternatives. For most models, the Polistance Quote Tweets dataset was the most challenging. This dataset measures stance detection and is particularly challenging because quote tweets often contain two opinions from two different people. The model must parse both of these opinions and correctly attribute stances to the right authors. Even the state-of-the-art Claude 3.5 had an F1 of only 67.1%. However, because the DEBATE models were explicitly trained to parse such documents, the base and large models achieve F1 scores of 84.7% and 92.7%, respectively.Footnote 6

Figure 3 Distribution of F1 across all datasets for zero-shot classification.

6 Few-Shot Classification

Few-shot classification refers to learning a new task with only a few examples rather than the hundreds or thousands conventionally required for supervised training. This can be accomplished in multiple ways. With LLMs, few-shot learning is commonly done by providing some examples in a prompt (Brown et al. Reference Brown2020). However, it can also be done by re-training the model on a very small training set. We demonstrate that the DEBATE models are efficient few-shot learners by training them on a simple random sample of documents. With only a few seconds of training on a modern laptop and no active learning scheme, the models are able to learn new tasks much more effectively than generative LLMs.

With few-shot learning, there is a concern that the learning schemes are prone to over-fitting on a non-representative training sample (Parnami and Lee Reference Parnami and Lee2022). While our results here and in Section E.4 of the Supplementary Material demonstrate that the DEBATE models are relatively reliable few-shot classifiers, we do not claim immunity to this concern. Thus, we emphasize that few-shot learning works best when a small number of samples can reasonably represent the data’s population distribution.

To illustrate this capability, we test data from two other research projects. Our primary example presented here is from Block Jr. et al. (Reference Block, Burnham, Kahn, Peng, Seeman and Seto2022), who trained a transformer model on roughly 2,000 tweets to identify posts that minimize the threat of COVID-19. A second example, presented in Section F of the Supplementary Material, comes from the Mood of the Nation poll—a regular poll with open-text survey questions issued by the McCourtney Institute for Democracy (Berkman and Plutzer Reference Berkman and Plutzer2024).

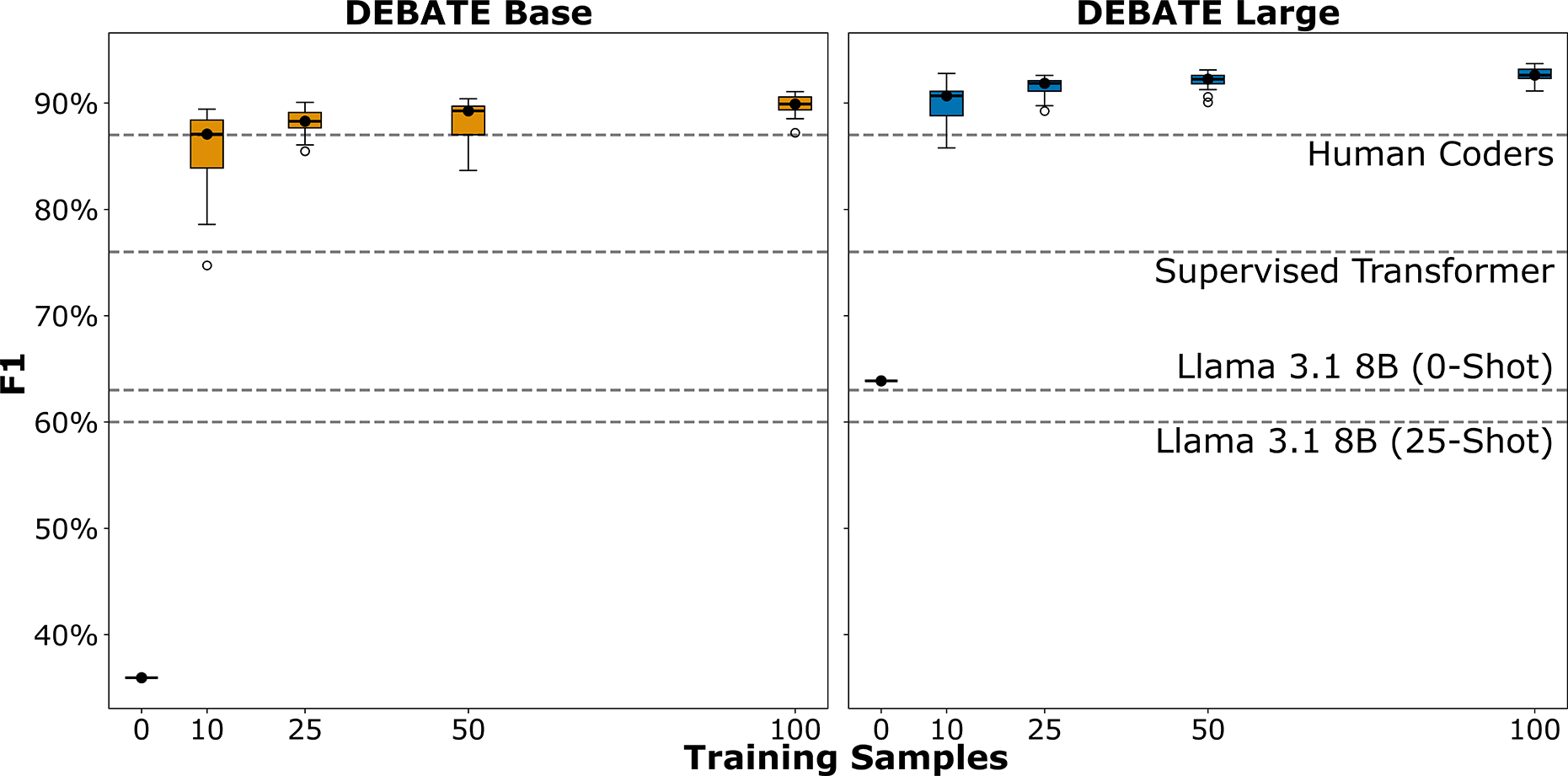

For our testing procedure, we first use both DEBATE models and Llama 3.1 8B to classify the documents zero-shot. To estimate few-shot performance with the DEBATE models, we take simple random samples of 10, 25, 50, and 100 documents, train the DEBATE models on these samples, and then estimate performance for the respective sample size on the rest of the labeled documents. We repeat this 20 times for each training sample size. To test the Llama model’s few-shot capabilities, we used parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) to train the model on 25 random examples and repeated this 30 times. PEFT is a process where only a small portion of a model’s weights are trained and the rest are frozen (Liu et al. Reference Liu2022). We use this approach for a number of reasons. First, fine tuning has generally superior performance to simply providing examples in the prompt (Liu et al. Reference Liu2022).Footnote 7 Second, we use PEFT because training a Llama model without PEFT requires too much compute to be done in a local environment, and is thus beyond the scope of our objectives. Finally, we do not test the Llama model across as many sample sizes because it requires far more resources to train, even when using PEFT.

As a practical point, we note that few-shot classification with the DEBATE models and a local LLM like Llama are not comparable processes. Longer prompts and PEFT can significantly increase the required memory and decrease the inference speed of LLMs. We found that PEFT took roughly 17 minutes to train on a discrete GPU while training the DEBATE models on identical samples took 5–10 seconds on a laptop. The Llama model was also more sensitive to hyperparameters, requiring additional time from researchers to identify parameters that work. For the DEBATE models, we did not search for the best-performing hypothesis statements or parameters. Instead, we used the default hyperparameters and simply trained the model for 5 epochs. Few-shot classification assumes researchers do not have a large testing set to search for the best parameters. To be useful, few-shot learning should work out-of-the-box.

6.1 COVID-19 Threat Minimization

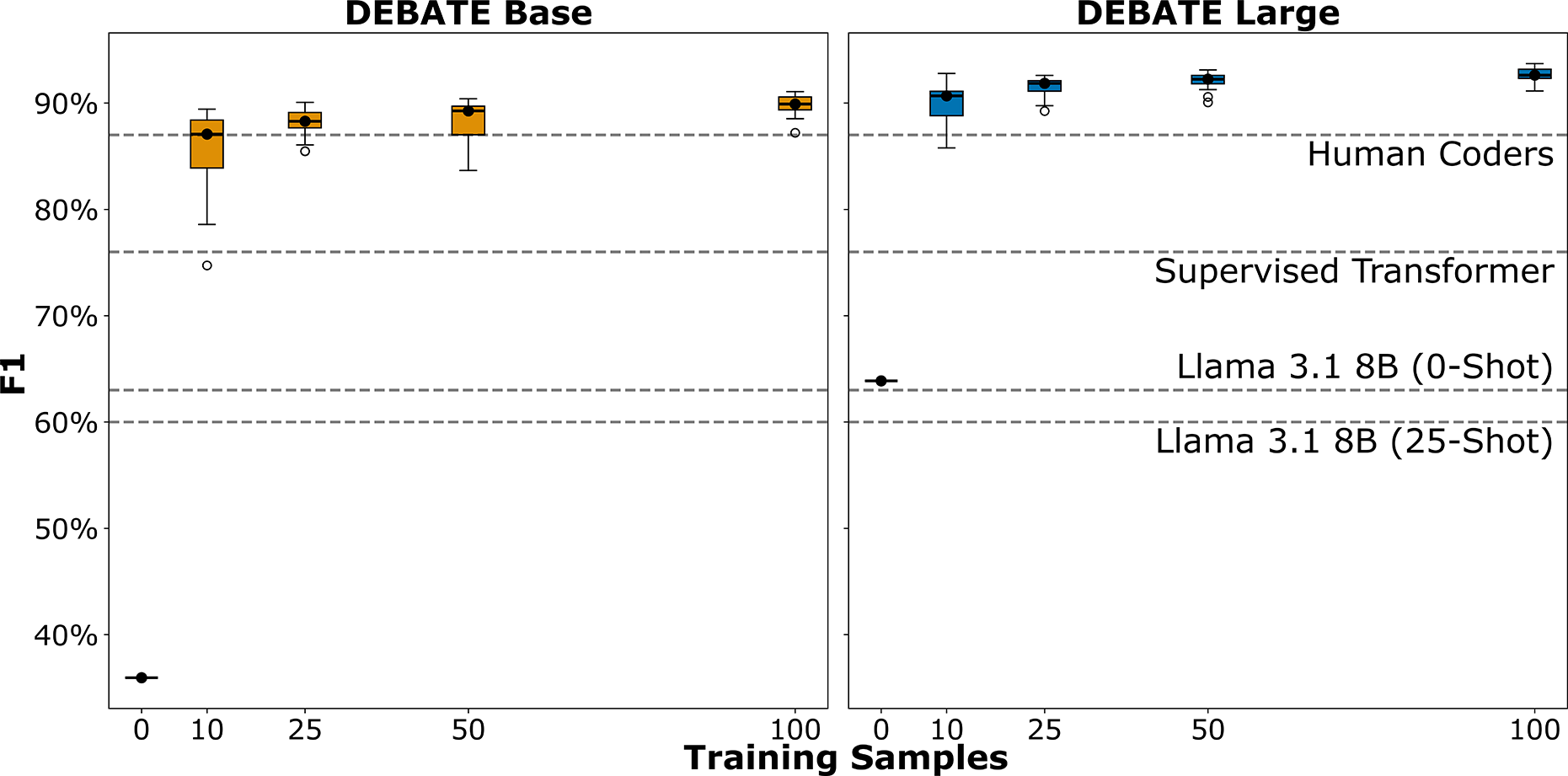

Block Jr. et al. (Reference Block, Burnham, Kahn, Peng, Seeman and Seto2022) classified Twitter posts about COVID-19 based on whether they minimized the threat of COVID-19. They defined threat minimization as anti-vaccination or anti-masking rhetoric, flu comparisons, statements against stay-at-home orders, claims that COVID-19 death counts were fake, or general rhetoric that the disease did not pose a significant health threat. Block Jr. et al. (Reference Block, Burnham, Kahn, Peng, Seeman and Seto2022) trained an Electra transformer on 2,000 tweets with a Bayesian sweep of the hyperparameter space. This process trained 30 iterations of the model to find the best-performing hyperparameters. Figure 4 illustrates that this is a particularly difficult classification task. Even a well-trained supervised classifier falls well below human performance.

Figure 4 Classification of COVID-19 Tweets.

For an NLI classifier, few-shot learning provides an elegant solution to teaching the model exactly how the authors defined “threat minimization.” To test the models, we use the hypothesis “The author of this tweet does not believe COVID is dangerous.” Figure 4 shows that DEBATE Base largely fails at the task in a zero-shot context, while the large model falls well below the supervised classifier. However, at 25 training examples, both models consistently meet or exceed the human benchmark of

![]() $F1 = 87\%$

. Few-shot learning provided only a small performance gain for Llama 3.1.

$F1 = 87\%$

. Few-shot learning provided only a small performance gain for Llama 3.1.

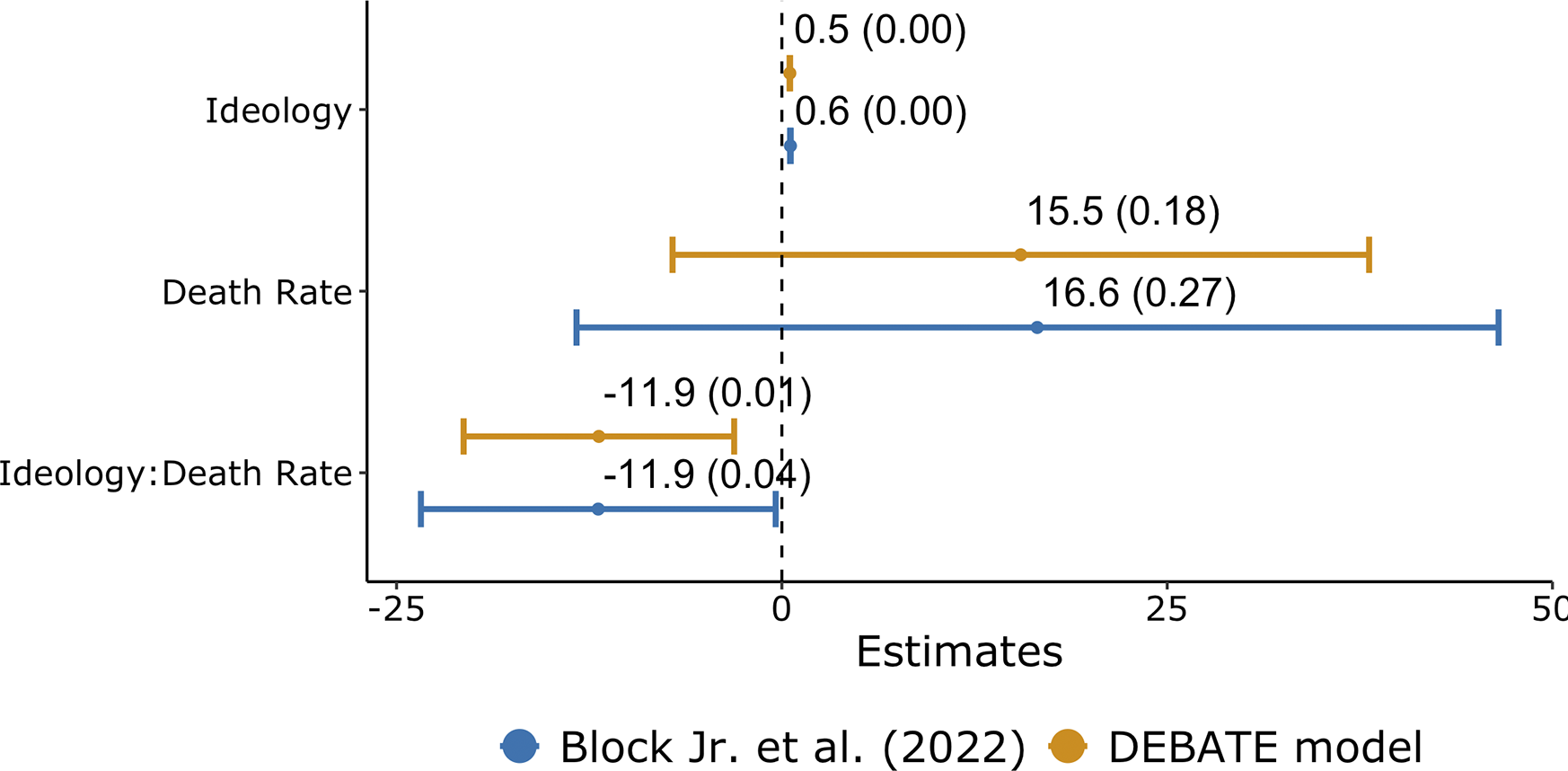

This ability to achieve human-like classification on very challenging tasks can have down-stream implications for statistical inference. To illustrate, we trained DEBATE large on a random set of 25 documents and then re-classified the entire corpus from Block Jr. et al. (Reference Block, Burnham, Kahn, Peng, Seeman and Seto2022). We then re-ran their main regression model—a negative binomial model where the dependent variable was the number of threat minimizing statements an individual made. Figure 5 compares our results to the original paper. The primary focus of their study is the interaction Ideology * Death Rate. The effect size shifted from

![]() $-$

11.9 to

$-$

11.9 to

![]() $-$

15.8, and the associated p-value moved from 0.045 to 0.010. In short, better text classifiers can uncover stronger and more robust effects.

$-$

15.8, and the associated p-value moved from 0.045 to 0.010. In short, better text classifiers can uncover stronger and more robust effects.

Figure 5 Comparison of regression estimates (with p-values) between the DEBATE model and Block Jr. et al. (Reference Block, Burnham, Kahn, Peng, Seeman and Seto2022).Note: In addition to the above variables, the model includes a vector of demographic and geographic controls.

7 Timing Benchmarks

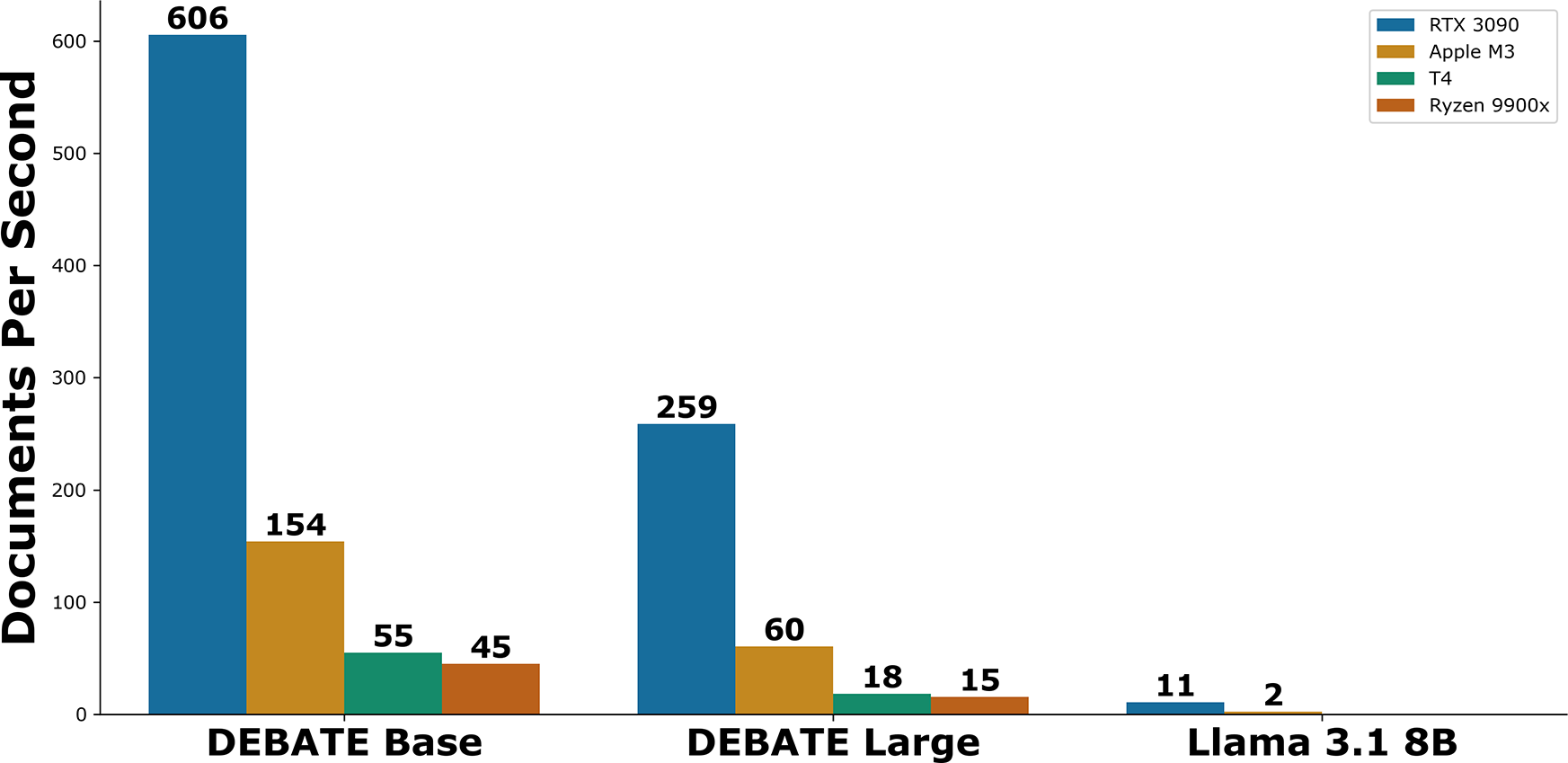

To assess efficiency, we tested our DEBATE models and Llama 3.1 on a range of hardware with a random sample of 5,000 documents from the PolNLI test set and the simple hypothesis “This text is about politics.”Footnote 8 We selected four different hardware platforms. First, the NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 tests a consumer grade GPU commonly used for language models. Second, the NVIDIA Tesla T4 is a lower-end GPU that is freely available through Google Colab. Third, we used a Macbook Pro with the M3 max chip. This is a common laptop with a built-in GPU. Finally, the AMD Ryzen 9 9900x CPU was utilized to evaluate performance on a general-purpose CPU.Footnote 9

Figure 6 The DEBATE models offer a massive efficiency advantage over generative language models.

We observe that the DEBATE models offer significant speed advantages over even small generative LLMs like Llama 3.1 8B. While discrete GPUs like the RTX 3090 offer a large performance advantage, documents can still be classified at a brisk pace with a laptop GPU or a cloud GPU like the T4 (Figure 6).

8 Limitations and Model Use

The model and dataset can be downloaded from the Hugging Face hub. We recommend using Python’s Transformers (Wolf et al. Reference Wolf2020) and Datasets (Lhoest et al. Reference Lhoest2021) libraries to use the models and data. We include boilerplate code for zero-shot and few-shot applications on the github repository for this article.

Our models can be used for both binary and multi-class classification. For multi-class tasks, the models can either provide a predicted probability for each class, or select the single most probable class if labels are mutually exclusive. Whenever possible, we suggest allowing for multiple labels. The approach used can be toggled in the software package and is outlined in the coding examples. While we offer brief advice on application here, for a more thorough exploration of best practices when using NLI classifiers, we defer to Burnham (Reference Burnham2025).

8.1 When Should I Consider Few-Shot Training?

Few-shot or supervised training should be considered if any of the following conditions are met:

-

• Labels cannot reasonably be derived from a document’s text alone and require meta-knowledge, such as who wrote the document and in what context.

-

• Labels are based on bespoke concepts for a particular project or require specialized domain knowledge (e.g., populism) rather than commonly understood concepts (e.g., support/opposition to a person or policy).

-

• Documents must meet any, all, or none of multiple conditions to be assigned a label (e.g., “threat minimization” of COVID-19). This can also be accomplished by using multiple hypothesis statements (e.g., one for anti-vaccination stances, one for anti-masking, etc.), and checking if any or all are satisfied. However, we generally recommend forming a single hypothesis and then few-shot training.

-

• Documents are longer than a couple of paragraphs and cannot be segmented.

Whether a condition is met is a qualitative judgment based on familiarity with the data and task. As with all classifications, always validate your results with manually labeled data.

8.2 Which Model Should I Use?

We offer the following guidelines for selecting a model:

-

• Use the large model for zero-shot classification.

-

• Use the large model for most few-shot applications.

-

• Use the base model for simple few-shot tasks or supervised classification.

Our extensive use of NLI models and previous research (Burnham Reference Burnham2025) indicates larger models generalize better to unseen tasks. However, for tasks more explicitly within the training distribution (e.g., hate-speech or approval of politicians), we expect comparable performance between large and base models, with the base model offering greater efficiency. In the few-shot context, the large model more quickly learns tasks and provides more consistent results.

8.3 How Should I Construct Hypotheses?

Researchers are not required to use hypotheses in the PolNLI dataset and are encouraged to draft their own. We recommend short, simple hypotheses similar to the templates in the training data. For example:

-

• “This text is about (topic or event).”

-

• “The author of this text supports (politician or policy position).”

-

• “This text is attacking (person or group).”

-

• “This document is hate-speech.”

Few-shot training may be appropriate for tasks that require long hypotheses with multiple conditions, or when researchers have multiple hypotheses for a single label.

8.4 Other Limitations

Despite the impressive benchmarks, we emphasize that researchers should not expect the DEBATE models to outperform large LLMs on all classification tasks. Because of their massive size and training corpora, LLMs can perform a wider variety of tasks. Accordingly, we expect LLMs will more robustly generalize in the zero-shot context for tasks less proximate to the PolNLI dataset. We recommend few-shot training for such tasks.

Notably absent from the PolNLI dataset are labels for broad ideological categories (e.g., conservative or liberal). We acknowledge that many researchers will want to utilize these categories, but intentionally omitted them because they can have different meanings in different political contexts. In such cases, we encourage researchers to break the task down into specific beliefs or train the models.

We also note that these models are trained exclusively for English documents, and it is unknown how they would perform if re-trained for non-English documents. With the extensive amount of data from the U.S. Congress and Supreme Court, we expect the models to have the most adept understanding of U.S. politics. We additionally note that the models were trained on contemporary documents, and it is unknown how they would perform on historical English.

A potential concern researchers should be aware of is using the models on datasets included in the training data. For example, the training data currently includes tweets from members of Congress that are labeled for whether or not they express support of President Trump. This does not include any Tweets from 2024 or later. If a researcher were to use our model to label support for President Trump on a dataset that includes tweets both in the training data as well as tweets posted after 2024, this would potentially introduce bias into the labels and may affect downstream statistical analysis. Researchers are encouraged to consult Section A of the Supplementary Material on the contents of the training data and adjust their research design accordingly.

Finally, although the PolNLI dataset covers a variety of demographic and ideological groups, these models may reflect biases in the training data like all language models. This is particularly relevant when analyzing politically sensitive topics or texts from underrepresented groups. In Section D of the Supplementary Material, we test potential demographic and political biases and find that the DEBATE models exhibit more consistency across groups than alternative models. However, we suggest practitioners be mindful of these potential biases when applying the models to sensitive contexts.

9 Conclusion and Future Work

The models presented in this article show immense potential for open, accessible, and reproducible text analysis in political science. We hope this is only the first step and think the following areas merit further research:

-

1. The PolNLI dataset can be expanded to cover multiple languages and more diverse political contexts. This would make text analysis more accessible to a wider group of researchers.

-

2. Political domain adapted embedding models have numerous potential applications beyond classification. This includes unsupervised tasks like clustering and information retrieval, but also regression models (Rodriguez, Spirling, and Stewart Reference Rodriguez, Spirling and Stewart2023) and applications of recent research on interpretable embeddings (O’Neill et al. Reference O’Neill, Ye, Iyer and Wu2024).

-

3. The recent ModernBERT architecture from Warner et al. (Reference Warner2025) shows promise for further pushing the boundaries of efficiency and overcoming the limitations of the NLI framework. While this article presents classifiers trained on their architecture, they can also be trained to construct document embeddings and are more adaptable to long documents and detailed instructions.

Domain adapted language models can be a public good for the research community. We hope others will join us in building these tools.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Nelson, Bruce Desmarais, and the three reviewers for their helpful feedback on this project. The authors would also like to thank Eric Plutzer for sharing access to the Mood of the Nation polling data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Center for Social Data Analytics at the Pennsylvania State University.

Data availability statement

Replication data and code for this article is available at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SV5VHH (Burnham et al. Reference Burnham, Kahn, Wang and Peng2025).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2025.10028.