Introduction

In recent years, there has been a continuous expansion of the literature on the significant role of religion in international relations (Sandal and Fox, Reference Sandal and Fox2013). One area in which an effort to integrate religion into IR was made is the emerging concept of religious soft power. Soft power, initially coined by Joseph Nye in the 1990s, refers to the power that states can acquire through their culture, political values, and foreign policy. However, the theory has since been expanded by Nye and others to include various other sources of soft power, including religion. The body of literature focusing on religious soft power has developed substantially in the last decade (Haynes, Reference Haynes2021).

Yet, there are two gaps in the existing literature. First, most of the research has primarily focused on the actors who possess soft power, neglecting the impact of that power on the audiences affected. Second, the limited number of scholars who did study the audiences mainly analyzed their attitudes toward the influencers rather than their own actions and behaviors. This paper aims to address these gaps by focusing on the actions of individuals and groups influenced by religious soft power. The research question guiding this paper is: What courses of action targeted individuals of religious soft power take and why? Using three illustrative cases, the Catholic Church and its believers, ISIS and its followers, and Israel and the Evangelicals, I develop a new typology to better understand the types of actions of individuals and groups affected by religious soft power.

The paper is structured as follows: first, a literature review summarizes the development of the concept of religious soft power. Next, the typology of actions and behaviors by affected audiences is developed and elaborated upon, including disruptive, reformative, and independent courses of action. Subsequently, historical case studies are presented and analyzed to illustrate these three courses of action. Following that, the findings of the analysis are discussed, and possible explanations for the observed actions are suggested. Lastly, the conclusion section emphasizes the contributions of the paper and outlines potential avenues for future research.

Literature review

In 1990, Joseph Nye introduced the concept of soft power to the field of international relations. Power, as defined by Dahl (Reference Dahl1957), refers to the ability of A to influence B to undertake an action they otherwise wouldn't. Traditionally in international relations, these outcomes were believed to be achieved through either coercion or payments, commonly referred to as “sticks and carrots.” Nye proposed a third avenue for achieving desired outcomes: soft power. Soft power is “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments. […] It arises from the attractiveness of a country's culture, political ideals, and policies” (Nye, Reference Nye2004a, 256).

While Nye was the main scholar to popularize the concept, its intellectual roots go as far as to Edward H. Carr and Hans Morgenthau (Fan, Reference Fan2008). Carr noticed that power over opinion is “not less essential for political purposes than military and economic power” (Carr, Reference Carr1964, 132). Morgenthau, in his descriptions of the different elements of state power, indicates “national morale, national character, and quality of government and diplomacy” (Morgenthau, Reference Morgenthau1967). These elements of national power are very similar to what Nye identified as sources of soft power several decades later.

Since its introduction in 1990, the concept of soft power was further developed. Nye expanded and diversified the sources contributing to soft power, encompassing foreign immigrants, international students, tourists, Nobel Prize winners, life expectancy, foreign aid, and spending on public diplomacy (Fan, Reference Fan2008). Other scholars have also identified elements of popular culture, such as movies, books, computer games, and sports, as potential sources of soft power (Press-Barnathan, Reference Press-Barnathan2017). The application of the soft power concept has been also broadened to encompass international organizations (Jones, Reference Jones2010), multilateral/collective soft power (Gallarotti, Reference Gallarotti2016), transnational movements (Haynes, Reference Haynes2016; Crespo and Gregory, Reference Crespo and Gregory2020), and even individuals (Nye, Reference Nye2021).

Recently, scholars have begun investigating the concept of religious soft power. The concept itself is not new, as Nye noted: “For centuries, organized religious movements have possessed soft power” (Reference Nye2004b, 98). Although Nye did not further develop this concept, religion can be easily integrated into its basic definition of soft power as a pillar of the state's culture, history, values system, and even its political structure. As Jödicke (Reference Jödicke and Jödicke2017, 2) puts it, religion can function as a “cultural force that—without restriction to national territories—supports attraction, identification, and solidarity” (Reference Jödicke and Jödicke2017, 2).

As in other types of soft power, religious influencers' ability to control the interpretations of their messages and the resulting actions is limited. Soft power is disseminated through various channels, many of which are not directly controlled by the government (Rothman, Reference Rothman2011). Consequently, complete alignment in objectives or means of action among targeted audiences should not be expected. Furthermore, certain messages may have different effects on diverse audiences due to cultural, religious, and historical differences (Nye, Reference Nye2004b).

The concept of soft power has attracted much criticism over the years for its ambiguity and vagueness (see Fan, Reference Fan2008), and religious soft power is susceptible to the same lines of criticism (Haynes, Reference Haynes2021). Indeed, different scholars suggested various definitions for the concept and applied it in many different ways. In his edited book, Jödicke (Reference Jödicke and Jödicke2017, 2) notes that the concept of religious soft power is used in the book “in an investigative sense and with a heuristic purpose, to identify a variety of constellations in which religions play a political role in transnational relations.” Mandaville and Hamid (Reference Mandaville and Hamid2018, 6) used the term “to thematize the phenomenon whereby states incorporate the promotion of religion into their broader foreign policy conduct.” Bettiza (Reference Bettiza2020, 2) highlighted the importance of “sacred capital” (religious resources) that “can generate particular forms of international power and influence,” including religious soft power. Haynes (Reference Haynes2021, 13) defined it as “the capacity to encourage an actor to behave in a certain way because of their religious beliefs.” In this study, I follow Haynes' definition. It is important to emphasize, though, that the entities influenced by religious soft power do not have to be sovereign states. They can be, as I will shortly demonstrate, individuals or groups that in turn influence their governments to behave in a way that better suits the interests of the possessor of the religious soft power.

The literature on religious soft power has rapidly increased in the last few years. While some scholars, such as Haynes (Reference Haynes2016), provided a wide overview of the religious soft power of non-state actors, most of the scholarship remained focused on the religious soft power of sovereign states. Köse et al. (Reference Köse, Özcan and Karakoç2016) assessed the soft power of Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia among Middle Eastern populations; Ciftci and Tezcür (Reference Ciftci and Tezcür2016) conducted a similar analysis on the soft power of these states among Egyptians and Iranians; Al-Filali and Gallarotti (Reference Al-Filali and Gallarotti2012) focused on the soft power of Saudi Arabia; Roberts (Reference Roberts2019) reflected on Qatar's “Islamic soft power.” In Jödicke's (Reference Jödicke and Jödicke2017) edited book the religious soft power influences of Russia, Turkey, Iran, and the European Union in the Caucasus were further investigated; Solik and Baar (Reference Solik and Baar2019) have argued that Russia uses the soft power of the Orthodox Church to maintain its influence in the post-Soviet area; Henne (Reference Henne2019) argued that although commonly neglected, the United States has a religious soft power that is “persisted and even expanded”; Ozturk (Reference Ozturk2021) shed light on the many ways Turkey uses religion in its foreign policy including in the form of soft power; and Ganguly (Reference Ganguly2020) investigated India's use of religious soft power in its diplomatic relations.

Most studies above share one pattern in common: they all concentrate on the actor who possesses religious soft power (whether state or non-state) and not the targeted audiences who are affected by that power. The handful of scholars who focused on the targeted side usually analyzed its attitudes toward the influencer rather than its follow-up actions and behavior (e.g., Ciftci and Tezcür, Reference Ciftci and Tezcür2016; Köse et al., Reference Köse, Özcan and Karakoç2016).

This paper takes a different course. First, it focuses on those affected by the exertion of religious soft power (the “targeted”). Second, it investigates the effect on individuals and groups and not states.Footnote 1 Third, it analyzes the actions taken by those individuals and groups and not only their preferences. In this analysis, the word “actor” refers to the entity that exercises religious soft power, whether a state or non-state actor. “Targeted audiences” refers to individuals and groups affected by the actor's soft power. “Home state” refers to the state of citizenship of the targeted audiences.

To answer the question of what courses of action targeted individuals of religious soft power can take and why, I offer a new typology of actions individuals affected by religious soft power can take regarding their home state's foreign policy: disruptive, reformative, and independent.

To illustrate how the different courses of action take place in reality, I use three historical examples: Israel and the Evangelicals, the Pope and its Catholic believers, and ISIS and its Sunni followers. The Catholic Church, ISIS, and Israel are the “actors” (i.e., the entities possessing religious soft power) and the “home states” are the states of citizenship of the individuals who were affected by the religious soft power of the actors and in which they try to promote the interest of the relevant actor (which might be the United States, Latin American States, European states, Middle Eastern states, etc.).

I selected these cases for several reasons: first, they represent three of the largest religions in the world: Catholics, Sunni Muslims, and Christian Evangelicals. Together they constitute about 40–50% of the world population. (This is not to say that most Sunnis support ISIS or its practices or that most Evangelicals are actively supporting Israel.) Second, the cases cover a wide geographical scope of action, of either the religious actor or its followers, ranging from the Middle East and Africa to Europe, North America, and Latin America. Lastly, in the case of the Catholic Church, I also include one example from the Middle Ages, in addition to instances from the Modern Era, to provide a variation not only in space but also in time. This, however, may rightly raise questions regarding temporality and the relevance of Nye's concept to pre-modern times. Although Nye developed his concept around the American case in the 20th century, this type of power did not begin with Nye nor with Carr. It is perhaps as old as international politics is. The Catholic Church's influence over its believers in the 11th and 12th Centuries is relevant for our discussion as it represents a pre-state system example of a usage of religious soft power.

A typology of courses of action

The presented typology delineates the spectrum of actions accessible to individuals influenced by religious soft power as they seek to advance the interests of the influencing actor. Two options within this typology involve influencing a change in their home state's foreign policy, while the third is not contingent upon altering its behavior.

Disruptive action: A disruptive action is characterized by violent or other forms of subversive behavior, taken by individuals and groups who are influenced by religious soft power, aiming at changing the foreign and domestic policies of their home state to fit the interests of the influencer. These actions can be taken to alter a specific policy, the entire approach of the government toward the influencer, or simply to harm and weaken the home state for the benefit of the influencer. These goals can be achieved by a variety of means and tactics that include violent attacks on governmental assets or civilians, an armed overthrow of the government, or spying on behalf of the influencing actor. These types of activities represent an instance in which religious soft power undermines the legitimacy and the sovereignty of home states.

Reformative action: A reformative action is characterized by legal and non-violent behavior. Its objectives are identical to those of a disruptive course of action, but the measures taken are drastically different. This strategy aims at changing the state's foreign and domestic policies through legitimate political measures. These can vary based on the political structure and political culture of the home state. In democratic states, such actions may include influencing public opinion, protesting, lobbying, voting, and donating money to candidates who run for office and support the influencing actor. In authoritarian states, individuals and groups may develop interpersonal relations with leaders or elite members and even use bribery in order to influence policymakers. A reformative action is thus a legitimate participation in the political game. As such, it does not undermine nor challenge the sovereignty of the home state.

Independent action: This type of behavior is different from the previous two in one major feature: An independent course of action does not aim at changing the home state's foreign or domestic policy, by legitimate or illegitimate means. Rather, it aims to promote the interests of the influencer directly. This course of action is more prevalent than one may think. It can take many shapes and forms, such as working through non-governmental organizations, volunteering at the influencer territory, donating money to the influencer, and even joining a military campaign overseas.

The inclusion of the disruptive action category might raise questions regarding the distinction between soft and hard power, as soft power traditionally excludes coercive methods such as violence or threats (Nye, Reference Nye2004b). For instance, if a state possessing religious soft power, like Iran, employs military threats to compel a neighboring state to alter its behavior, it is not a soft power exertion. However, the utilization of religious authority by Iran to influence Shiite groups in Iraq, leading them to support Iran and advance its interests, exemplifies a case of soft power, even when the Shiite groups employ violent means to alter their governments’ attitudes toward Iran.

As is the case with any typology, the one proposed here is not flawless and the line separating the different categories may be blurred to some extent, so the different actions traced are not mutually exclusive. For example, enlisting in the military force of another actor might be construed as an independent act, yet it could also be deemed illegal (disruptive). This is especially relevant if one is fighting alongside an adversary of their home state and against its military forces, as observed in instances with groups like ISIS. Despite the potential overlap, this typology remains valuable and can contribute to a more thorough analysis and understanding of the phenomenon of religious soft power and its impact.

Moreover, these courses of action can be used simultaneously by some individuals. For instance, individuals may engage in both independent actions, such as making a direct money transfer to the actor, and reformative actions, such as advocating for the actor's sake in their home state. Alternatively, one might simultaneously support a terrorist organization by assisting volunteers to travel overseas to join its military campaign and to carry out a terrorist attack aiming at changing the action the home state takes against that terrorist organization.

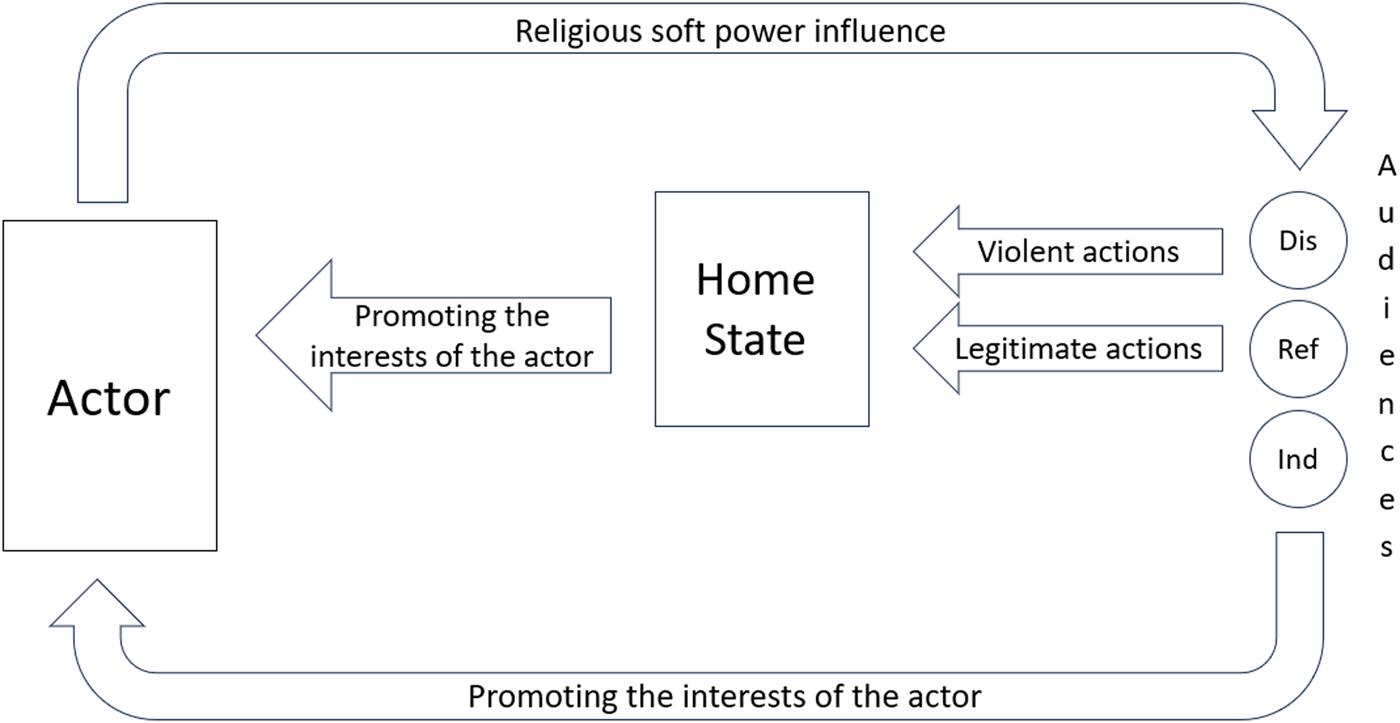

Figure 1 outlines the process of religious soft power effects. As previously explained, disruptive and reformative courses of action aim to influence changes in the foreign and domestic policies of home states. In contrast, independent actions bypass the home state and are aimed at directly assisting the actor beyond its borders. The following section explains each actor's religious soft power, followed by an illustration of the varied courses of action taken by individuals under its influence.

Figure 1. Religious soft power at work

Israel and the Evangelical movement (21st century)

When assessing Israel's soft power, scholars usually tend to point to Israel's remarkable high-tech and research achievements (Gerstenfeld, Reference Gerstenfeld2021) and rarely mention the other source of soft power Israel embodies—religious soft power. Israel, as the Jewish state or the state of “the chosen people,” has a unique religious position that leads some Christian individuals and groups to support it out of religious convictions. This Christian empathy toward the Jewish people and later toward the Jewish state is commonly known as “Christian Zionism.” This phenomenon has its roots in the 19th century and perhaps even earlier when several different branches of Protestants exercised the first instances of Christian Zionism (Williams, Reference Williams2015). Over the past few decades, Christian Zionism has gradually become predominantly an Evangelical phenomenon.

The relations between Israel and the Evangelicals attracted significant scholarly attention lately (Mayer, Reference Mayer2004; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Francia and Morris2008; Gries, Reference Gries2015; Inbari and Bumin, Reference Inbari and Bumin2020; Ziv, Reference Ziv2022). All the current research has reached a similar conclusion: Evangelicals are very supportive of the State of Israel compared to other religious groups. Various justifications for this strong support are indicated in the literature. Firstly, the Evangelical adherence to a literal interpretation of the Bible according to which the Jews are God's chosen people, and the Land of Israel was promised to them (Miller, Reference Miller2014). Another rationale stems from the biblical promise in Genesis 12:3, wherein God pledges to bless those who aid the Jewish people and curse those who do not (Spector, Reference Spector2009). Additional justifications include gratitude for Judaism's contributions to Christianity (Hagee, Reference Hagee2006) and eschatological beliefs positing the return of the Jews to the Land of Israel and the establishment of the Temple as prerequisites for the second coming of Christ (Kilde, Reference Kilde, Bruce David and Kilde2004). The Evangelical support for the State of Israel, therefore, primarily emanates from Israel's religious and cultural heritage, making it a manifestation of Israel's religious soft power.

Reformative action

The relocation of the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in 2018, by former President Donald Trump, made headlines and attracted many scholars and pundits mainly for its geopolitical consequences. However, the origins of the decision and the forces behind it are no less important to discuss. It was a very successful example of a reformative action taken by U.S. Evangelicals on behalf of the State of Israel.

For years, Israel has sought international recognition of Jerusalem as its capital and the relocation of foreign embassies to the city. The United States, despite promises from several presidents, had refrained from making this move due to concerns about security and geopolitical implications. However, in 2018, the Trump administration opened the new U.S. embassy in Jerusalem. This decision was largely influenced by an Evangelical-led campaign (Borger, Reference Borger2019).

One of the Evangelical organizations that were the spearhead of this campaign is Christian United for Israel (CUFI). This organization with its nine million members, lobbies for pro-Israel policies in both Congress and the White House. This organization's campaign for the relocation of the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem was a crucial factor leading to President Trump's announcement to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Months before his announcement, “Some 135,000 members of CUFI […] reportedly sent emails to the White House urging the president to move the embassy” (Spector, Reference Spector2019). Evangelical prominent figures had pressured Trump daily to fulfill his promise. Mike Evans, who was Trump's advisory council, asserted that the White House's decision on Jerusalem “100% happened because of the Evangelicals. No question” (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Boorstein and Eglash2018).

In Latin America, an organization called the Latino Coalition for Israel (LCI) is also pursuing similar objectives. In 2018, it launched the Latin American Jerusalem Task Force that promoted the declaration of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and the transfer of Latin American embassies to the city. As Lourdes Aguirre, LCI director declared: “It is our desire to see other Latin American nations follow the bold decision and leadership of President Trump and President Morales [in Guatemala]” (Aguirre, Reference Aguirre2018). The decision made by President Morales to relocate Guatemala's embassy to Jerusalem was influenced, to some extent, by Evangelical lobbying and personal relations with the president (Noack, Reference Noack2018). In other Latin American countries, Evangelical leaders have been urging their governments to move their embassies to Jerusalem (Martínez, Reference Martínez2020).

In Africa, influential Nigerian pastors such as Chris Oyakhilome, T. B. Joshua, and Enoch Adeboye regularly express their support for Israel and advocate for diplomatic support from the Nigerian government. Charismatic leaders like Duncan Williams in Ghana and Pastor Robert Kayanja in Uganda are frequently engaged by Israeli diplomats to endorse Israel's public relations campaigns and advocacy efforts (Gidron, Reference Gidron2022).

Independent action

The relations between Evangelical groups and individuals and Israel offer various examples of independent actions. These encompass financial contributions to Israel, volunteering in the country, and collaborating with international non-governmental organizations to improve Israel's image.

The International Fellowship of Christians and Jews (IFCJ) is a non-profit organization, founded in 1983 by American Jews and Evangelical Christians aiming at “building bridges between Christians and Jews, blessing Israel and the Jewish people around the world with humanitarian care and life-saving aid” (IFCJ, a). The organization focuses on assisting Israel and Jews in the diaspora through humanitarian, educational, and security projects. Since its beginning, it collected around two billion dollars from Evangelical Christians for Israel (IFCJ, b). The U.S.-based CUFI is a Christian organization, funded by Pastor John Hagee, which donated throughout the years more than one hundred million dollars to Israel and Jewish Charities (CUFI). Other organizations such as Christian Friends of Israel, Christ Church Jerusalem, and HaYovel assist Christians to volunteer in Israel in hospitals, agriculture, fire departments, humanitarian projects, IDF bases, and more.

The International Christian Embassy of Jerusalem (ICEJ) is an international Evangelical organization established in 1980 that advocates for Israel worldwide. With delegations in over 90 countries, the organization engages in various activities to support Israel. These include donating funds for welfare projects in Israel, aiding Jews who wish to relocate to Israel, contributing over 150 bomb shelters to protect Israeli civilians, supporting Holocaust survivors, and facilitating Christian tourism to Israel. In response to the BDS movement in 2014, the ICEJ initiated a campaign promoting the purchase of Israeli products (ICEJ, 2014).

The Pope and Catholic believers

Catholicism is currently the largest religious movement in the world (Pew, 2013). Unlike Protestantism, the Roman Catholic Church operates as a strictly hierarchical organization in which the highest authority is held by the Bishop of Rome, the Pope. The Pope, as the head of the Catholic Church, has a significant amount of religious soft power over Catholic believers. This power stems from the Pope's moral position and due to Papal infallibility and the monopoly it has over the interpretation of the Holy Scriptures (Crespo and Gregory, Reference Crespo and Gregory2020). This power is what Chong (Reference Chong2013) described as the Church's power of “spiritual persuasion.” Crespo and Gregory (Reference Crespo and Gregory2020) regarded this power as the Church's “moral authority” while Byrnes (Reference Byrnes2017) described the Church as a “moral megaphone.” Throughout the years, the Roman Catholic Church has used its religious soft power to promote different moral and political agendas such as human rights, religious freedom, democratization, refugee policies, anti-communism, and even environmental policies.

The relationship between the Catholic Church and its believers spans nearly two thousand years, providing a unique opportunity to expand the dimension of time. The Catholic Church has employed soft power throughout its history, even predating the modern era of the state system since Westphalia (1648). In this case, I will provide three examples—one from the pre-modern era and two from the modern era—to illustrate various instances of the Church's utilization of religious soft power.

11th and 12th centuries

Independent action

One of the most notable instances of the deployment of Papal soft power to influence world politics occurred during the First Crusade and the People's Crusade in the 11th and 12th centuries. In November 1095, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II issued a call for a Crusade to reclaim the Holy Land and liberate the Holy Sites from the Seljuk Turks. This call was a response to a plea for assistance from the Byzantine Emperor, Alexios I Komnenos, whose empire had lost significant territories to the Seljuks. Scholars are debating on whether the primary aim of the First Crusade was to aid the Byzantine Empire, to recapture Jerusalem, or a combination of both. However, for our analysis, this question holds less relevance.

What is interesting for our purposes is the actual call of Pope Urban II and the ways it was received by European Christians. In his address at Clermont, Urban used religious terms and justifications to persuade individuals to promote the international agenda of the Catholic Church. Urban called to “deliver the Holy city of Jerusalem from pagan domination” (Cowdrey, Reference Cowdrey1970, 177). He preached for an armed pilgrimage that would “serve as penance for those who participated” (Bull, Reference Bull1993, 99).

The call for a holy war was answered, and the First Crusade began in the summer of 1096. The force departing from Western Europe, which included knights and notable European princes, numbered approximately 100,000. This campaign proved highly successful, resulting in the capture of Jerusalem in 1099. However, an earlier attempt of that Crusade was even more intriguing. It began before the official Crusade embarked and involved tens of thousands of untrained, impoverished European peasants who voluntarily organized into small groups. Usually inspired by local preachers such as Peter the Hermit, they initiated a journey to the Holy Land, later named the “People's Crusade” (Asbridge, Reference Asbridge2004). Although this campaign was a complete failure in military terms, it vividly demonstrated the “spiritual power” the Pope had over laymen in Western Europe. Christian believers left everything behind and joined a very dangerous journey, which many of them did not survive, to comply with the Pope's request. These people saw themselves as “knights of God” (Riley-Smith, Reference Riley-Smith2003).

Individuals from across the European continent responded to the call of a religious actor and, lacking the requisite skills or equipment for such a challenge, ventured overseas to engage in a religious war. Instead of attempting to influence their kings, whether legitimately or illegitimately, to align with the Pope's call, they acted independently of their rulers. The answer to the famous question asked by Joseph Stalin—The Pope, how many divisions has he got?—is thus, “it depends,” but at some point in history, it is “more than you think.”

20th and 21st centuries

Reformative action

In 1978, Karol Wojtyla, the Bishop of Krakow, was elected as Pope and became Pope John Paul II. One of his primary global objectives was to promote the spread of democracy (Barrett, Reference Barrett2010). He began to advance his vision in Poland, which was then under communist rule. His first visit to his homeland in 1979 played a significant role in the emergence of the Solidarity movement, which eventually led to the downfall of the communist government in Poland. As Alexander Kwasniewski, the former President of Poland, aptly phrased it: “We wouldn't have had a free Poland without him” (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein2005).

During his nine-day visit to Poland on June 2, 1979, the Pope delivered speeches that directly confronted communism and the control it exerted over the Polish people (Kraszewski, Reference Kraszewski2012). His objective was to awaken Polish religious beliefs and national sentiment. Although he did not explicitly call for the overthrow of the communist government, he cultivated the spiritual and mental groundwork upon which local resistance could flourish.

In a speech in Warsaw on June 2, 1979, he affirmed the loyalty of the Polish people to the Church rather than to a specific government. This notion directly contradicted the Soviet ideology, which viewed religious loyalty as an impediment to a communist revolution. A day later, he proclaimed that Poland, with its rich religious history, was “spiritually independent” and possessed a unique culture, implying that no imperial bloc could assimilate Poland into its territory or dissolve Polish identity, which was deeply intertwined with the Church. In an important speech he gave to students of Krakow he said: “You must carry into the future the whole of the experience of history that is called “Poland”. It is a difficult experience, perhaps one of the most difficult in the world, in Europe, and in the Church. Do not be afraid of the toil.”

According to Bronislaw Geremek, a former foreign minister of Poland, when the pope visited in 1979, he brought “a very simple message […]. He said, ‘Don't be afraid.’” There were attempts for democratic uprisings before 1979, Geremek continued, but John Paul II helped the people understand that a communist regime cannot work without social approval, and simply told them: “Don't approve” (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein2005).

Although the Pope did not explicitly call for rebellion against the communist government, his implicit message was clear to his audience and played a vital role in encouraging the Polish people to stand up for their country, their history, and their freedom. The Pope's call reverberated a year later. On August 14, 1980, the Solidarity movement was founded when 17,000 workers went on strike at the Lenin Shipyards (Kubow, Reference Kubow2013). One of the iconic symbols of the strike was a picture of the Pope that was displayed on the shipyard gates (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein2005). In its early stages, the Pope was the most “influential and empowering symbol of the upcoming Solidarity movement” (Kubow, Reference Kubow2013, 10).

Ten years later, after a decade of political unrest, economic crises, and numerous strikes and demonstrations led by Solidarity and its allies, the communist government permitted relatively free elections in Poland—the first free elections in any Soviet bloc country. Solidarity won the elections, and a coalition government led by Solidarity was formed in 1989. In 1990, Lech Walesa, the leader of Solidarity, was elected as the President of Poland. These elections ultimately marked the end of the communist regime, and Poland transitioned to democracy. In 1991, Walesa addressed the Pope, stating: “Without your work and prayer … there would be no ‘Solidarity’… there would be no Polish August and no victory of freedom” (Withers, Reference Withers1991).

Interestingly, Solidarity was careful not to employ force or violence (Burgess and Burgess, Reference Burgess, Burgess, Wehr, Burgess and Burgess1994). Strikes and demonstrations were their primary means of challenging the government. From the perspective of the typology proposed in this article, this case is of particular interest. On the one hand, Solidarity's methods were non-violent (reformative). On the other hand, their objective was to bring about a change in the regime in Poland (which could be regarded as a disruptive aim). Nonetheless, since the means of action were non-violent, I consider instances like this to fall under the reformative category. Therefore, despite posing a serious challenge to the communist government and eventually leading to its downfall, I still regard this case as an example of reformative action.

Independent action

In 2015, Pope Francis released his encyclical Laudato Si’, with the title “On Care of Our Common Home.” In this document, Francis articulated his environmental vision, focusing on the impact of global warming. He emphasized the need for changes in lifestyle, production, and consumption to combat global warming, advocating for reduced greenhouse gas emissions and the development of a waste disposal and recycling economy. He established a link between our responsibility for the environment and justice for the poor, connecting it to traditional Catholic social teaching (Buckley, Reference Buckley2022). The environment became a prominent aspect of Pope Francis's foreign policy (Crespo and Gregory, Reference Crespo and Gregory2020), and he has addressed this issue on numerous occasions.

Since the publication of Laudato Si’, several studies have demonstrated its impact on Catholic believers' perception of global warming (Maibach, Reference Maibach2015; Gray, Reference Gray2016). Myers et al. (Reference Myers, Roser-Renouf, Maibach and Leiserowitz2017) went even further and found that exposure to Francis's message not only heightened Catholic concerns about the environment but also correlated with actions taken to address global warming. Numerous instances exist of individual Catholics and groups responding to Pope Francis's call and taking action or intensifying their efforts to promote his environmental vision.

For example, the Archdiocese of Atlanta launched the “Laudato Si’ Action Plan,” which offers various options for parishes and parishioners to contribute to reversing the threats of global climate change and environmental degradation. Pope Francis's call served as the primary justification for this publication, which highlights changes in consumption habits, water preservation, greenhouse gas reduction, and recycling. As of 2020, the Archdiocese of Atlanta had 1,200,000 registered members (ARCHATL, 2021).

In 2021, The Catholic Church Bishops' Conference of England and Wales published guidelines to help Catholic dioceses achieve net zero carbon. Father Dominic Howarth of the Diocese of Brentwood stated that the document “is leading the Catholic Church nationally in helping us to implement Pope Francis’ call to action in Laudato Si” (CBCEW, 2021).

By 2018, almost 600 Catholic institutions in the United States signed the Catholic Climate Declaration. The declaration calls for action on climate change that “threatens our common home and future and impacts our poor and vulnerable neighbors the most.” According to the authors of the declaration it is the most “significant expression of support for climate action by the Catholic Church in the United States since Pope Francis’ encyclical, Laudato Si’ in 2015” (Roewe, 2018). On a different front, many Catholic institutions including dioceses, universities, and banks are divesting from fossil fuels. These organizations manage billions of dollars that will not be invested in fossil fuels companies any more (CBCEW, 2023; Roewe, 2023).

Islamic State (ISIS) and Sunni believers (2010s)

When thinking about terrorist organizations, one rarely links them with soft power. Therefore, the ability of these organizations to use soft power is “too frequently ignored” (Voll, Reference Voll and Banchoff2008, 262). However, for such fundamentalist groups, this is an important source of power, especially because they lack the hard power abilities of modern states. This power of attraction is crucial for terrorist organizations, as Nye (Reference Nye2004b, 25) puts it: “It is through soft power that terrorists gain general support as well as new recruits.” ISIS, like other Muslim terror organizations, subscribes to ideas such as religious terrorism, Jihadism, and radical Islam. These Islamist ideas are very important as a tool to attract potential supporters. As Tella (Reference Tella2018, 816) puts it: These “brands of Islam that emphasize the embrace of Sharia law, and the literal interpretation of the Quran are appealing to many Muslims that have lost faith in the government of the day and find solace in religion.”

Although ISIS started as a relatively centralized group that originated in Iraq in 2003, after it conquered parts of Iraq and Syria, many Islamist groups pledged allegiance to ISIS's leader. ISIS, at some periods, had branches (Islamist groups that pledged allegiance to ISIS) in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Libya, Afghanistan, Yemen, Algeria, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the Caucasus, Somalia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Congo, Mozambique, India, Bangladesh, Azerbaijan, and Turkey (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2021). This development has expanded the ISIS threat globally, but turned the organization into a “Medusa, […] with semi-independent branches operating all over the world” (Khatib, Reference Khatib2015). As such a loose organization, its leadership couldn't directly control many entities that perceived themselves as part of the new Calipha.

Moreover, many Muslim individuals, who were not affiliated with any ISIS branch, were inspired by its message and committed terrorist attacks against governments and civilians. These “lone wolves” claimed to act in the name of ISIS, and the organization gladly claimed credit for their actions as it strengthened its image as a global power. However, it is hard to determine whether ISIS had anything to do with the attacks (Kearns, Reference Kearns2021). Nevertheless, when thinking about religious soft power, a direct link between ISIS and the terror attack is not necessary. If the attacker was inspired by ISIS, it can be considered an instance of soft power at work.

Disruptive action

As in the case of many other terrorist organizations, one of the most common strategies of ISIS followers was disruptive action. One of ISIS's main objectives was to prevent Western countries from fighting the organization and threatening its territorial achievements. In 2014 an international coalition led by the United States and other Western countries intervened in Syria and Iraq by launching an airstrike campaign against ISIS. As a response, ISIS spokesman Muhammad al Adnani issued a statement calling for ISIS supporters in their home states to kill any American, French, Australian, or Canadian in “any way possible” (Welch, Reference Welch2014). Since this call, many ISIS supporters have conducted terrorist attacks in their own countries.

Paris, London, Sydney, California, Orlando, Nice, Minnesota, Berlin, Manchester, North Carolina, Barcelona, Brussels, Marseille, and New York became the targets of several attacks that occurred during the operation of the coalition. ISIS, which claimed responsibility for many of these attacks, always linked the actions of its supporters to the Western campaign against the organization. After the Paris attack in November 2015, which led to 130 casualties, ISIS issued a statement describing the attack as a response to the French airstrike against ISIS in Syria. France, he added, will remain a key target as long as it operates against the organization (The Guardian, 2015). After the Christmas attack in Berlin in December 2016, a similar statement was issued by the organization's AMAQ news agency, saying the attack was a “response to calls to target nationals of the coalition countries” (Reuters, 2016). Similar statements were issued after attacks in London, Barcelona, New York, and elsewhere.

These events illuminated the relations between the actor and the targeted audiences in the case of ISIS and its supporters. ISIS's main area of action was the Middle East. Western governments and citizens, although being “infidels,” were not systematically targeted by the organization before the Western-dominated coalition began operating against the organization. Since then, ISIS shifted the focus of its calls to its supporters to act in ways that would change the policies and actions of their home state governments. Whether it was through acts of revenge or direct threats to continue targeting Westerns as long as Western governments operate against ISIS, the goal of ISIS and its supporters was a disruptive action aiming at changing the policy of their home state by violent means.

Independent action

The resemblance between the People's Crusade and ISIS recruitment for its campaigns in Syria and Iraq is clear. As of 2017, about 40,000 individuals from 110 countries have joined the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq (Barrett, Reference Barrett2017). Since 2014 ISIS has demonstrated a remarkable appeal to Sunni Muslims from all around the world (Mahood and Rane, Reference Mahood and Rane2017). That included Sunnis from Syria, Iraq, and other Muslim-majority countries in the region, but also Europe, Canada, and the United States.

ISIS propaganda tools, which combined pictures, videos, and preachings all in relatively high-quality production, have proved to be an extremely important mechanism for the recruitment of new members through the internet (Benmelech and Klor, Reference Benmelech and Klor2020). In a world in which borders do not pose any barrier to information anymore, young Sunnis could get a flood of information, which was carefully selected and orchestrated by ISIS, on its growing Khalifah, the advances in the battlefields, and the day-to-day life under the Islamic law (the Sharia) in ISIS-controlled territories.

The organization's messages included many Islamist ideas. One of them is the need to repel the “Crusaders,” the infidels who occupied Muslim territories (Mahood and Rane, Reference Mahood and Rane2017). The Concept of “hijra” (migration for the sake of Allah) was also used frequently in ISIS messages as they encouraged all Muslims to move to the territory controlled by the organization (Ozeren et al., Reference Ozeren, Hekim, Elmas and Canbegi2018). Another Islamist narrative that was prevalent in the ISIS message was the fight against “Hypocrites.” These are the people who “outwardly profess to be Muslims but secretly seek to undermine the Islamic State” (Mahood and Rane, Reference Mahood and Rane2017, 20). Abu Bakar al-Baghdadi summarized its religious message by saying that “there is no excuse for any Muslim not to migrate to the Islamic State. […] Joining [its fight] is a duty on every Muslim” (BBC, 2015).

His call was indeed answered. As mentioned, around 40,000 Sunni Muslims from all around the globe flew into ISIS territories and joined the fight. These new members came from different classes of society, and not mainly from the poorer and uneducated groups, as one may expect (Benmelech and Klor, Reference Benmelech and Klor2020). These young people left their sometimes comfortable lives behind and joined military campaigns after being persuaded by a religious actor that this is the “Muslim” thing to do. As in the case of the People's Crusade, these individuals did not attempt to influence their own home state's policy but rather acted independently to promote the interest of the religious entity that influenced them.

Reformative, disruptive, or independent: Why do individuals choose one course of action over the other?

In all three cases, individuals opted for independent actions. This, however, should not come as a surprise. When an individual seeks avenues to support an influential actor, opting for independent action might be a natural choice. Here, I do not suggest that it is the most effective one nor the cheapest in terms of personal resources and security. Rather, it is the natural choice because the individual is not reliant on their home state's cooperation to achieve their objectives. Individuals can contribute financially or join a military campaign, thereby directly assisting the actor independently and irrespective of their own governments' policies.

Interestingly, some individuals have employed reformative actions, as seen in the case of the Evangelicals and the Catholics in the modern era, while others used disruptive actions, as observed in the case of ISIS followers. This pattern raises an important question: when will individuals choose a reformative action and when will they take a disruptive one?

One can argue that the answer to this question lies in the different types of actors possessing religious soft power: state and non-state actors. These two types of actors should be analyzed separately as they have fundamentally different characteristics. Perhaps, the argument follows, the Evangelicals did not take disruptive actions to assist Israel only because Israel is a sovereign state, and its behavior and international actions are restricted by norms and rules that do not apply to non-state actors. ISIS has no such restrictions and therefore could encourage its supporters to take a disruptive path. States and non-state actors are indeed different entities and for many purposes should be analyzed separately. Yet, I contend that none of the three courses of action is limited to one type of actor or another.

There are several examples of sovereign states with a religious soft power that their targeted audiences choose to take a disruptive action. One example is Iran and its Shiite followers in the Middle East. Several Shiite groups in the region are affected by Iran's religious soft power in Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan, Bahrein, and elsewhere (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins, Akbarzadeh and Conduit2016). On several occasions, when the home state's attitude or policies contradicted Iran's interests, these groups did not hesitate to use disruptive actions. In Bahrain, Shiite terrorist organizations inspired by Iran have attempted several times to execute terrorist attacks in the kingdom in response to an Iranian demand (Al-Arabia, 2020). In Iraq, a Shiite militia used a drone attack to try to assassinate the re-elected Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi in November 2021. Al-Kadhimi is seen by Teheran as a supporter of Iran's arch-foe, the United States, and many claim the attack was an Iranian response to its re-election (Reuters, 2021).

Individual characteristics and traits may also be suggested to explain the variations. For instance, younger individuals may exhibit a greater propensity for adopting disruptive strategies, given their generally more radical nature and inclination toward revolutionary (violent) means. Conversely, individuals from higher socio-economic classes would tend to prefer reformative actions as they have more to lose from economic instability. Levels of religiosity can influence the levels of one's radicalism, and thus the more fundamentalist one is, the more he or she is expected to tilt toward violent actions.

Alternatively, the characteristics of the home state itself may shape one's choice of strategy. That includes the form of government, the demographics (whether the individual is part of an ethnic/religious minority or majority), or the level of trust in political institutions. For instance, in a democratic society, generally, we would expect to see more reformative actions than in non-democratic countries. If individuals perceive the political procedure as fair and legitimate, they will be less prone to try changing a policy violently. Conversely, individuals belonging to ethnic or religious minorities, who cannot see an avenue for a change in the existing political procedure, are more likely to take disruptive actions.

While these explanations are plausible, I find them insufficient and aim to propose a more comprehensive explanation. I contend that the answer to this question lies in the relationship between the influencing actor and the home state. Specifically, I argue that if an actor perceives the home state of the targeted individuals as illegitimate, it may lead the targeted audiences to pursue disruptive types of action. The rationale behind this assumption is straightforward: if the religious actor views the actions or existence of the home state government as illegitimate (or even as a “sin”), disruptive actions are not only acceptable but may also be perceived as a religious obligation. Consequently, the actor may encourage its followers to take such a path. Conversely, if the government of the home state is perceived as a legitimate authority by the religious actor, a specific policy disagreement is much less likely to evoke a disruptive action by the actor's followers.

In the 2010s, ISIS perceived Western states not only as an illegitimate force in the Middle East but also as “infidels.” Consequently, a strategy based on terrorist attacks on civilians and government assets was perceived as appropriate by its followers. In the case of Israel and the Evangelicals, Israel has never viewed the home states of the Evangelicals, whether in North or Latin America, as illegitimate, and it aspired to maintain good relations with their leaders. Thus, it has never encouraged any disruptive action as a means to influence the home states' behavior and policies even in countries like Bolivia or Venezuela, where their governments were, at times, hostile to the State of Israel. As mentioned earlier, the religious influencer cannot have complete control over the actions of the targeted audiences. However, it can define certain boundaries of what is considered appropriate and inappropriate, boundaries that are expected to be seriously taken into account by the audiences.

Conclusion

The primary contribution of this study lies in the typology it develops for the potential courses of action taken by individuals influenced by religious soft power. Their conceptualization into one scheme can assist us in better understanding and more accurately describing the phenomenon of religious soft power. The second contribution of this article is the proposed explanation for the question that arises from its findings: when do individuals choose reformative actions, and when do they opt for disruptive ones? This conjecture regarding the perceived legitimacy of the home state should be tested in future quantitative or qualitative research, in juxtaposition to other alternative explanations.

While this study focuses on religious soft power, the typology it suggests is not limited to this type of soft power alone. By adapting to other changing circumstances and contexts, these alternative courses of action can be applied to non-religious forms of soft power such as ideological (secular) soft power. One example of such a case is the former Soviet Union. Throughout the Cold War, many were drawn to the Marxist ideology and its main advocator, the Soviet Union. These individuals have employed different courses of action to promote the Soviets' interests. Just to mention a few, the political consolidation of numerous communist parties in the 1940s and 1950s in Europe exemplified a reformative type of action. These parties sought to distance their countries from the “capitalist United States” and adopt a more pro-Soviet stance (Wettig, Reference Wettig2008). An example of a disruptive type of action can be illustrated by individuals who decided to become spies and betrayed their home states to assist the Soviets during the Cold War (see Melman, Reference Melman2008).

However, it seems considerably less likely that a large-scale “crusade” of individuals—not as part of a state-level military alliance—would take place in the case of non-religious soft power. Future research, therefore, should, on the one hand, further adjust the typology presented in this study to non-religious soft power cases, while on the other hand, emphasizing the differences between the types. This will contribute to the integration of religion into the soft power framework while underlining its uniqueness.

This study adds another dimension to the understanding of soft power, shedding light on specific elements of its manifestation in the religious domain, with theoretical and practical implications. The research on soft power, which has seen renewed interest in recent years, should be continually developed, especially in our rapidly changing reality where states are faced with more international challenges and opportunities than ever before. In this reality, the use of soft power and smart power (the combination of soft power and hard power) may prove more valuable than scholars and decision-makers had estimated before (Gallarotti, Reference Gallarotti2015), including the religious dimension.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Arie Kacowicz for his guidance and advice.

Competing interest

I hereby declare that I am not aware of any conflict of interest associated with this submission.

Tom Ziv is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of International Relations at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research focuses on the relations between the State of Israel and Evangelical communities in Latin America and Africa. He is also interested in the fields of international relations theory and the intersection of religion and politics.