Junior doctors working within in-patient mental health settings are often required to assess self-harm injuries and wounds sustained from unintentional accidents. Such superficial wounds are encountered frequently by trainees in surgery and emergency medicine, but less commonly by junior trainees in psychiatry. National clinical guidelines advise that all clinical staff involved in the treatment of self-harm should have appropriate training in the treatment and management of superficial uncomplicated injuries.1 However, we noted that there was no provision in our department for this kind of tailored teaching. In our methods, we describe a retrospective audit which revealed 18 episodes in 6 months where a patient was transferred to the emergency department for simple wound management. As a result, it was hypothesised that significant savings could be made by training junior doctors in psychiatry in the recognition of wounds that could be treated without transfer to the emergency department. Furthermore, this could reduce the stress and perceived stigma that patients experience when attending the emergency department for self-inflicted wounds. We identified two key interventions that could be made: first, compiling a suturing kit box to be kept available on site; and, second, providing a suturing and wound management workshop for trainees. In this paper, we describe the process of designing a workshop, compiling a kit box and evaluating the effect of this teaching programme using Kirkpatrick's Hierarchy of Learning.Reference Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick2

Methods

Wound management workshop design

A 1-h workshop was designed by two psychiatry trainees, a surgical trainee and a consultant in emergency medicine. This was offered to all trainees working in adult, intellectual disabilities, adolescent and elderly care psychiatry at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital (REH). It was advertised by email at the time of trainee induction, and an emphasis was placed on making the workshop accessible to all (it was run in two separate time-slots in an afternoon session reserved for trainee teaching). Our learning objectives were to: manage common wounds, safely use local anaesthetic, select an appropriate treatment for a wound, demonstrate correct handling of suture and instruments, and perform interrupted sutures. An example lesson plan is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 The structure of our workshop, showing topics covered and the time taken

Suturing kit box design

We compiled a list of equipment required for closing wounds with either sutures or steri-strips. The equipment was stored in a portable plastic box and kept on site at REH. In order to keep track of stock, all items were photographed and displayed along with their order codes on the lid of the box (Fig. 1). We purposefully included only the equipment required for simple suturing. This included 3-0 or 4-0 non-absorbable suture, a basic instrument pack, a sterile dressing pack, lidocaine without adrenaline, and needles for drawing up and injecting. In choosing this limited range we hoped that trainees would not treat wounds beyond their level of competence.

Fig. 1 Suturing kit box.

Evaluation of teaching

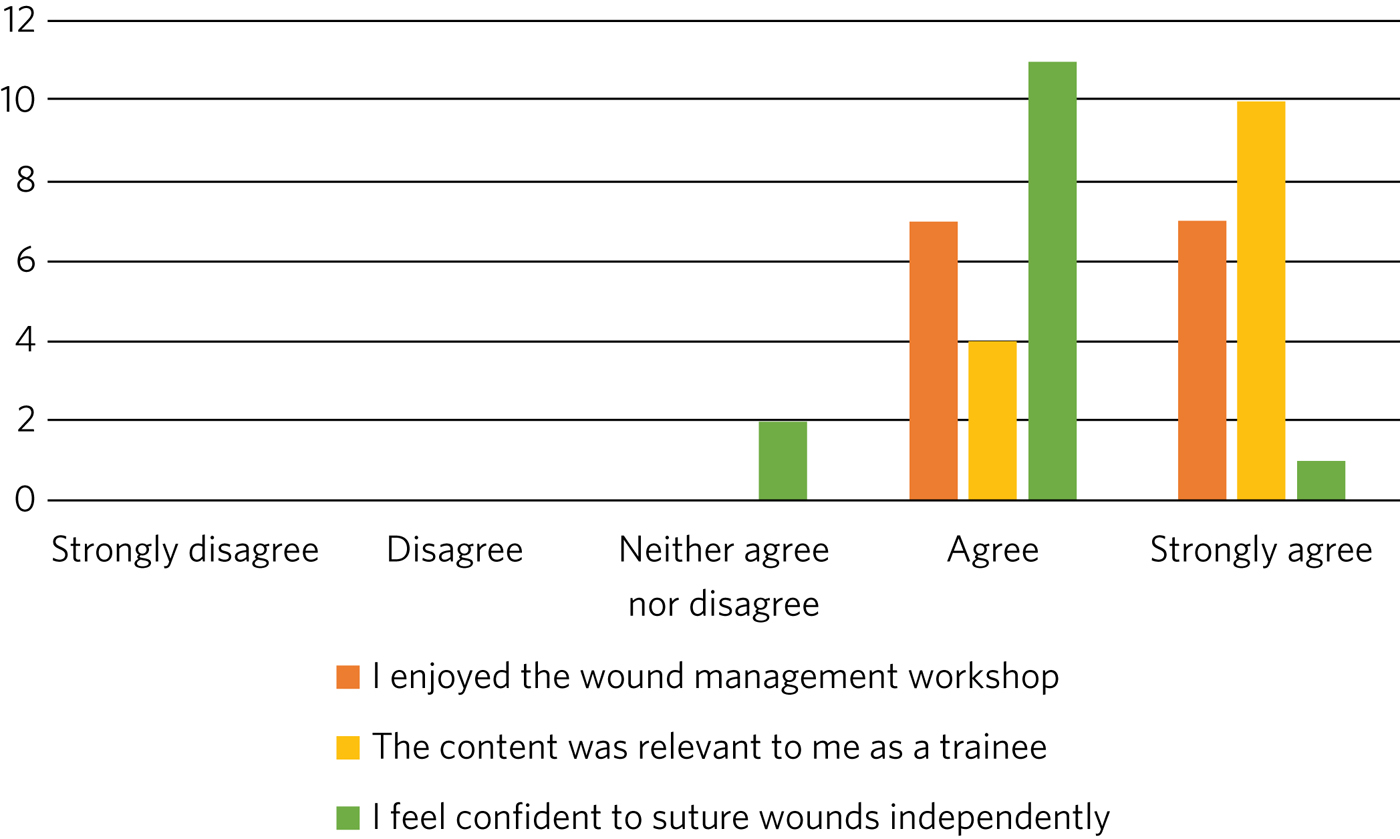

To assess engagement in teaching (Kirkpatrick level 1), attendees completed an online questionnaire with Likert-rated statements. This was emailed to attendees 1 week following the workshop, and a certificate of attendance was provided on completion of the questionnaire. These statements were: ‘I enjoyed the wound management workshop’, ‘The content was relevant to me as a trainee’ and ‘I feel confident to suture wounds independently’.

To assess knowledge and confidence acquisition (Kirkpatrick level 2), attendees completed a questionnaire prior to and following the workshop. In this questionnaire, they viewed two images of deep wounds (e.g. wrist laceration with tendon visible and deep laceration through muscle) and two images of superficial wounds (i.e. only through skin with subcutaneous fat showing). Trainees were blinded to whether a wound was deemed superficial or deep – they had to assess it by appearance alone with no other history provided. They were asked to view the images and respond on a Likert scale to the statement ‘I could manage this wound without referral to the emergency department’. An example of the wound images used is shown in Supplementary Appendix 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2018.41.

Collecting transfer data

In order to assess whether trainees displayed a behavioural change (Kirkpatrick level 3), we collected Datix (an online incident reporting system) reports from all in-patient psychiatric wards at REH. These are completed by nursing staff whenever there is a self-harm or wound incident. Datix reports were in an electronic SBAR (situation, background, assessment and recommendation) format which allowed free-text search. Incidents which mentioned ‘laceration’, ‘wound’, ‘doctor’ and ‘suture’ were identified and the individual entries reviewed. This allowed us to ascertain how many patients were treated on site with first aid or simple wound management (steri-strips, sutures and dressings).

To assess the effect on service delivery (Kirkpatrick level 4), we identified the number of patients transferred for superficial wound management to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE) emergency department over a 6 month period before and after the workshop. These data were collected retrospectively from August 2016 to August 2017. All patients transferred from REH to RIE were identified using the ‘Trak’ electronic healthcare record system, and the case notes for each patient were reviewed. In each case the documented presenting complaint was noted, along with any treatment provided. This allowed us to identify a subset of patients with superficial wounds which could have been managed without specialist input. Inclusion criteria were: (a) wounds documented as subcutaneous or superficial; (b) wounds closed by either a junior trainee or emergency nurse practitioner; (c) wounds which needed no treatment. Episodes where the wound was significant enough to be referred to a senior emergency department clinician or specialty doctor were excluded.

Calculating cost savings

We itemised the steps involved in patient transfer and requested a breakdown of cost from our hospital finance department. This included an estimate of the time an emergency department clinician spent assessing and treating the patient. The cost of treating a patient on site was estimated by summing the cost of raw materials required to close a wound (i.e. suture, local anaesthetic and dressings) and 30 min of clinician time. The cost of running the workshop in terms of materials, room booking and clinician time were also outlined.

Results

Evaluation of teaching

A total of 34 trainees attended two workshops in February (N = 14) and August 2017 (N = 20). Attendees were foundation year 2 (N = 17), general practice (N = 12) or core psychiatry (N = 5) trainees.

Level 1 – Engagement in teaching

Of the 34 trainees, 24 rated the statements in Fig. 2 – 91% of responses were ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’.

Fig. 2 Agreement of trainees attending the workshop to the statements illustrated.

Level 2 – Knowledge acquisition

Self-confidence rating was completed by 32 of the 34 attendees (94%) prior to the workshop and by 26 of the 34 attendees (76%) following the workshop. Figure 3 shows the Likert responses for wounds that could be managed by a novice trainee and those that should be referred. Responses of ‘agree’ and ‘disagree’ pre and post workshop were analysed with a chi-squared test in a 2 × 2 contingency table.

Fig. 3 Self-confidence rating of trainees before and after the workshop for (a) superficial wounds and (b) deep wounds which should be referred.

For simple superficial wounds, there was a significant increase (P = 0.001) in post-workshop confidence, with a reduction in ‘disagree’ responses and an increase in ‘agree’ responses (to the statement ‘I could manage this wound without referral to the emergency department’).

For complex deep wounds (which should be referred), there was an unexpected, significant increase in confidence. Following the workshop, several attendees changed their response, with 23% stating that they would be confident to manage these wounds without referral to the emergency department.

Levels 3 and 4 – Assessing behavioural change and effects on service

Combining data collected from emergency department referrals and review of Datix reports of in-patient self-harm, Fig. 4 outlines locations of treatment before and after the teaching workshop. Chi-squared analysis showed a significant difference between patients treated on site and those transferred to the emergency department (P = 0.0001).

Fig. 4 Data from Datix incident reports and emergency department case notes showing the number of wounds treated on site compared with those transferred in the 6 months before the workshop and 6 months after.

Calculating cost savings

Table 2 compares the itemised cost of transfer to the emergency department with treatment on site.

Table 2 Itemised costs involved in transferring a patient to the emergency department compared with the cost of raw materials required to treat on site and the cost of the teaching intervention

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study aiming to reduce the number of psychiatric in-patients transferred to the emergency department for treatment of minor wounds. Specifically, we were interested to know whether simple superficial wounds could be treated on site, negating the need for transfer and reducing the psychological distress to the patient.Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur3 Several studies have described the effects and cost to the emergency department of self-harm in general, but these primarily involve self-presentation rather than transfer from an in-patient setting.Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal and Park4–Reference James, Stewart, Wright and Bowers7 One study did describe psychiatric in-patient self-harm episodes and reported that 8% of these resulted in emergency department attendance, although the nature of treatment in the emergency department was not outlined.Reference James, Stewart, Wright and Bowers7

One possible reason for transferring such superficial wounds to the emergency department could be that our junior trainees lacked confidence and skills in managing simple wounds. This may be representative of national challenges in the UK: a recent national survey of undergraduate medical students suggested that most leave medical school lacking in confidence in basic suturing skills and knowledge of which suturing technique to deploy.Reference Rufai, Holland, Dimovska, Bing Chuo, Tilley and Ellis8 This is despite ‘skin suturing’ and ‘wound care and basic wound dressing’ being stipulated as expected outcomes for medical undergraduates by the end of their medical training within the UK.9 While junior doctors working in psychiatry may be expected to be less knowledgeable in wound management compared with those in surgical or emergency specialties, the Royal College of Psychiatrists expects core psychiatry trainees to be able to ‘Know the principles underlying management and prevention of … self harm’.10

Therefore, the first challenge of this study was to engage junior doctors working in psychiatry and empower them to manage simple wounds without transfer to the emergency department. We accomplished this by adopting a peer-led, multi-specialty approach. The workshop described above (Table 1) was facilitated by junior psychiatry trainees who had invited attendees via email. It was then taught by a surgical trainee who demonstrated practical suturing skills and an emergency medicine consultant who outlined general wound management principles. With this combined range of expertise, we found that most participants engaged positively (91%), agreeing that they enjoyed the workshop, felt more confident and that the teaching was relevant to their skill level (level 1 outcome, Fig. 2). Having input from a senior emergency department clinician was a crucial factor in this, as trainees often enquired as to what complexity of wound they should treat and what should be referred. This does raise the question of what level of wound management should be expected of a junior doctor in psychiatry. With reference to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance for self-harm,1 we suggest that skin lacerations greater than 5 cm in length which are deep enough to reveal underlying structures (not just subcutaneous fat) should always be discussed with the emergency department. We believe it is reasonable to expect a junior doctor working in psychiatry to manage a wound which is superficial and less than 5 cm in length, given the correct training. This was one of the key learning objectives in the workshop and was the rationale behind our evaluation of confidence change (level 2 outcome).

Assessing the competency of trainees in differentiating deep from superficial wounds was beyond the scope of this workshop. Equally, formally assessing the acquisition of technical suturing skills was not required, as this is an expected outcome of undergraduate medical education.9 Instead, in our level 2 outcome, we sought to measure the change in self-confidence rating following the workshop (Fig. 3). Confidence ratings are commonly used when evaluating surgical skill workshops. There is no relationship between confidence and competence prior to surgical skill teaching, but confidence does increase when a competency is gained.Reference Clanton, Gardner, Cheung, Mellert, Evancho-Chapman and George11 Since all attendees at our workshop had been taught suturing as undergraduates, we sought to enhance their confidence by focusing on re-teaching wound management and refreshing technical skills, rather than formally assessing technical competence. Trainees responded to an online questionnaire presenting them with a series of wound images. They were asked to rate the statement ‘I could manage this wound without referral to the emergency department’ on a five-point Likert scale. Prior to teaching, only 42% of trainees agreed with this statement, suggesting that they would be confident to treat the wound with their current skill set. Following teaching, this confidence was increased, with 71% of trainees agreeing with the statement. This increase was only true for wounds which were visibly superficial. When rating images of deep wounds (including those with visible tendon damage), there was an unexpected significant increase in trainee confidence (Fig. 3). Responses stating they would manage the wound without referral rose from 1.6 to 22.9%, suggesting that there is potential for trainees to treat wounds beyond their level of competence. Encouragingly, during the study period, there were no reported complications from the increased number of patients having their wounds managed at our psychiatric hospital, and no reports of inappropriate suturing attempts. We suggest that the change in confidence may reflect the challenge novice trainees encountered in determining the depth of deep wounds based only on a two-dimensional photograph.

As an objective measure of knowledge application (level 3), we collected Datix reports of in-patient self-harm episodes. Unfortunately, this is a free-text system based around an SBAR template; as a result, some incidents mentioned a laceration but did not outline how it was treated. In the remaining entries (where a treatment was recorded), we found a statistically significant increase in the number of wounds treated on site following our workshop. There was a corresponding decrease in the number of transfers to the emergency department in those same 6 months, as outlined in our level 4 outcome (Fig. 4).

The cost saving per patient is outlined in Table 2. This shows that a single transfer to the emergency department can cost a minimum of £200. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has investigated the costs of in-patient transfer to the emergency department for superficial wound management. One study estimated the cumulative cost from admission to discharge of a patient with self-harm presenting at the emergency department to be £425.24 per patient.Reference Yeo12 Another more recent study suggested the mean immediate cost to the hospital for each episode of self-harm to be £809.Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal and Park4 The latter estimate includes an average of £254 for psychosocial assessment. It also includes the costs of in-patient admission and medical treatment that would be required for certain types of self-harm, such as poisoning, trauma (e.g. fall from height, asphyxiation, jumping in front of a moving object) and drowning. These studies discuss self-harm which results in a superficial wound; however, the cost of treating this is not expanded on as a subcategory of self-harm. In our paper, we identify a very specific subset of self-harm patients that could benefit from on-site treatment. Such self-injury represents only 22% of emergency department presentations,Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal and Park4 and so it is likely that our estimated costs are considerably lower because they represent only the treatment of simple, superficial wounds.

There is a substantial difference in cost between treating the patient on site and transferring to the emergency department. Table 2 outlines the costs of treating on site, of treatment at the emergency department and of running the teaching workshop. A single, hour-long teaching workshop for 12 trainees cost an estimated £339.60. This included an hour of clinician time (two middle-grade trainees and a consultant), although in reality clinicians volunteered to teach in their spare time. Equally, we included an estimate of room booking cost, although this was provided to us free of charge as a departmental seminar room. Considering a single transfer costs £200 and treatment on site costs £16.24, it becomes cost-effective to run the workshop when the outcome is two or more patients being treated on site (this represents a potential £183.76 saving every time a patient is treated on site instead of being transferred to the emergency department).

This study was limited by being a small, single-centre study across two cohorts of junior doctors working in psychiatry. Data were collected retrospectively, and wounds documented in the emergency department notes were observer dependent. Equally, follow-up was limited to 6 months after teaching. A larger-scale study could more fully assess the effects of peer-led teaching interventions and could account for seasonal variation in patient transfer numbers. Additionally, future qualitative work should focus on the perspectives of patients and staff following such training.

This teaching evaluation showed that a peer-led workshop improves trainee self-confidence in managing superficial wounds. We have shown there was a significant reduction in transfers and considerable cost saving from two key interventions: providing training on wound management and making resources available on site. Combining these interventions had an effect on service delivery, and as a result more patients were treated without transfer to the emergency department. We hope that our findings illustrate a small but important improvement in the care we give to our patients, which could easily be replicated in other centres.

About the authors

T. A. Buick is a Core Surgical Trainee at NHS Lothian, UK; D. Hamilton and G. Weatherdon are Core Psychiatry Trainees at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital, UK; C. I. O'Shea is a Clinical Teaching Fellow at NHS Lothian, UK; and G. McAlpine is an Emergency Medicine Consultant at the Royal Infirmary Edinburgh, UK.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2018.41.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andy Johnston from eHealth analysis and our self-harm nurse Merrick Pope for their contributions to data acquisition in this study.

Ethics approval

We used the Health Research Authority ethics decision tool to confirm that this study did not require ethical approval.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.