Introduction

The start of Donald Trump’s second term as US president signalled a new and more dangerous phase of global democratic decline and the unravelling of the liberal international order. It continues an entrenched pattern where authoritarian, populist, and conservative religious actors mount a backlash against what they see as the elitist and intrusive core of the global liberal agenda.Footnote 1 Gender equality and women’s rights have been key targets of this backlash. The attacks have occurred not only at regional and national levels, as seen in the EU and the United States, but also increasingly on the global stage, within the United Nations.Footnote 2 Leading this effort are conservative religious NGOs, primarily from the United States and Western Europe – notably the Heritage Foundation, whose Project 2025 is widely seen as the blueprint for Trump’s second administration. Alongside alliances with certain post-Soviet, Islamic, and postcolonial states – as well as the United States under Trump – these organisations have invested substantial resources into reshaping the UN’s normative framework.Footnote 3 Despite differences, they are united in resisting ‘gender ideology’ and promoting traditional values, particularly the notion of ‘the natural family’.Footnote 4 Their efforts have yielded results, such as introducing ‘family rights’ language into several Human Rights Council resolutions and removing references to sexual and reproductive health from Security Council Resolution 2467 on women, peace, and security in 2019.Footnote 5

The rise of the conservative religious bloc within the UN has significantly challenged feminist and feminist-informed NGOs. While feminism at the UN has always been diverse and internally contested, ideological differences have not prevented feminists from seizing opportunities and shaping the UN’s agenda. Since its early days, feminists have influenced key UN institutions and policies, from establishing the Commission on the Status of Women to advancing the term ‘gender’ at the 1995 Beijing Conference and drafting Resolution 1325 on women in conflict. These efforts have fostered a sense of feminist ownership over the UN and, although much remains to be done, have helped establish it as a central platform for advancing gender equality and women’s rights globally. Any rollback would threaten these achievements and undermine decades of advocacy. While feminist and feminist-informed NGOs within the UN do not yet constitute a unified feminist front, they are part of a broader resistance network against the growing influence of anti-gender forces.Footnote 6

As a result, the UN has become a battleground for two opposing NGO networks with radically different views on gender equality and women’s rights: feminist and feminist-informed NGOs, who advocate for comprehensive gender equality – including reproductive autonomy and protection from discrimination and violence – and conservative NGOs, who promote traditional gender roles and strongly oppose reproductive rights, particularly abortion.

Multiple studies have already documented this new normative and advocacy dynamic. They also draw on multiple strands of literature, ranging from norms and international organisations (IO) politicisation research in International Relations (IR) to social movement studies in political science and sociology. Earlier studies have been mostly empirical, identifying key conservative actors and mapping their organisational strategies, coordination efforts, and the spaces where they mobilised.Footnote 7 More recent scholarship has placed greater emphasis on conceptualisation. Sanders introduces the concept of norm spoiling, describing how conservative actors actively work to delegitimise established international norms on women’s rights by portraying them as ideological impositions or threats to national sovereignty.Footnote 8 Counter-norming, as developed by Roggeband, explains how these actors do not merely oppose existing norms but actively construct and promote alternative frameworks rooted in traditional, nationalist, or religious values.Footnote 9 Voss conceptualises norm contestation as the process through which conservative NGOs engage in struggles over the interpretation and application of gender norms.Footnote 10 Finally, backlash advocacy, as explored by Cupać and Ebetürk, captures the broader mobilisation efforts of conservative NGOs to roll back feminist gains, while employing legal, political, and institutional strategies to entrench conservative agendas at the UN.Footnote 11

However, with few exceptions, existing research has devoted little attention to comparing feminist and feminist-informed NGOs with conservative NGOs.Footnote 12 Beyond comparing aspects such as their networks and modes of institutional engagement, one important dimension – examined in this paper – is how these NGOs perceive the UN, a key arena for their normative conflicts. This comparative angle follows from IR literature on the legitimacy and authority of IOs. Legitimacy perceptions shape how actors engage with IOs, influencing whether they support, contest, or disengage from them. If, for example, feminist NGOs view the UN as a progressive actor, they may seek deeper cooperation, whereas if they see it as unresponsive or co-opted by conservative forces, they might seek alternative venues for action. At the same time, legitimacy perceptions influence the UN’s effectiveness in a given issue area by defining the conditions for its ability to establish norms and enforce compliance. This is evident, for example, in the case of feminist actors within the UN not daring to organise the Fifth World Conference on Women, often attributed to fears that ideological polarisation would cause setbacks rather than progress in women’s rights.

However, beyond analysing the implications of feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs’ legitimacy perceptions and assessments of the UN, it is equally important to examine the underlying beliefs that shape these perceptions. Understanding these beliefs not only clarifies whether these NGOs view the UN as more or less legitimate but also reveals the reasons behind their perspectives. This approach enables a deeper analysis of the political, institutional, and normative dynamics influencing NGO–UN relations – without the immediate pressure of establishing causal links between perception and action. Nonetheless, future research can build on this foundation to explore how legitimacy perceptions shape NGO strategies and the UN’s responses amid ideological polarisation. Against this background, this paper asks: Under what circumstances, and based on which legitimacy beliefs, are feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs inclined to evaluate the UN along a spectrum from more positive to more negative?

To answer this question, we proceed in five steps. First, we delve into the theory of IO legitimacy, particularly its interplay with (1) IO authority, (2) the audience’s legitimacy evaluations, and (3) the beliefs shaping them. We argue that legitimacy evaluations consist of an audience’s assessments – ranging on a continuum from more positive to more negative – of whether an IO exercises its authority within a given domain appropriately. These evaluations, we posit, stem from prior ideas, norms, and values – what we term sources of legitimacy beliefs. We then apply these theoretical propositions to analyse how feminist, feminist-informed NGOs, and conservative NGOs perceive the UN. We first show that both groups recognise the UN’s authority. Then, using automated text analysis – semantic role labelling and sentiment analysis on 23,747 NGO documents – we examine their legitimacy evaluations of the UN over time. Plotting these reveals when the NGOs viewed the UN most positively and most negatively. Finally, we qualitatively analyse sixty sampled documents from these inflection points to infer the sources of legitimacy beliefs shaping their evaluations.

Our findings show that while the UN is central to feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs, it features more prominently in feminist communication. These NGOs consistently view the UN more positively, particularly when it champions feminist causes (IO performance and ideology as a source of legitimacy beliefs) and fosters institutional access (IO procedure as a source of legitimacy beliefs). Conservative NGOs evaluate the UN most positively when promoting an ‘originalist’ interpretation of its founding documents – an overlooked legitimacy source tied to ownership over an IO’s normative outputs. This finding is particularly striking, as it diverges from established sources of legitimacy beliefs in the literature. Instead, it suggests an overlooked dimension: legitimacy perceptions rooted in a sense of ownership over an IO’s normative outputs. This insight opens a promising avenue for further research, including comparisons with feminist claims of ownership over the UN. Conservative NGOs also rate the UN highly when allied with conservative states (IO procedure as a source of legitimacy beliefs) but most negatively when perceiving UN agencies as advancing a progressive agenda through misleading methods (IO procedure as a source of legitimacy beliefs).

The paper contributes to two strands of literature – IO legitimacy and the global anti-feminist backlash – which intersect as backlash studies draw from multiple scholarly traditions. It makes three key contributions. First, it shows that in polarised settings, legitimacy perceptions are also shaped by oppositional dynamics. Conservative NGO influence leads feminists to view the UN less positively, making it vulnerable to contestation from both liberal and illiberal forces, thus complicating simple distinctions between supporters and challengers of the tenets of the liberal international order. Second, it introduces normative ownership as a potential new source of legitimacy, showing that conservatives, while rejecting the UN’s liberal framework, seek to claim ideological and historical stakes in the institution rather than abandon it. Third, it challenges the view of illiberal backlash as purely reactionary by highlighting conservative norm-building. Further research should explore these areas and the link between legitimacy, NGO actions, and UN responses.

Legitimacy as a lens for analysing perceptions of international organisations

IO authority and legitimacy evaluations

IO legitimacy has long been a theme in IR, but it has only recently garnered more focused attention from scholars in the field.Footnote 13 The trend has also been accompanied by a more extensive empirical analysis of the phenomenon.Footnote 14 Following the sociological definition of IO legitimacy proposed by Jonas Tallberg and Michael Zürn, a definition that has recently come into the spotlight and been widely adopted, we characterise legitimacy as ‘beliefs within a given constituency or other relevant audience that a political institution’s exercise of authority is appropriate’.Footnote 15

This definition stands out for not only making IO legitimacy dependent on organisational authority but also the unique way in which it establishes this link: Authority is understood as the recognition of an organisation’s right to make norms, decisions, and interpretations within a particular social domain or issue area, while legitimacy concerns the audience’s evaluation of whether this right is exercised appropriately.Footnote 16 To illustrate, consider the World Health Organization (WHO) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The audience might recognise the WHO as the leading authority on global public health. Yet, while some might support the WHO’s decisions, others could question their fairness, impartiality, or impact. Put differently, the WHO’s exercise of authority could be viewed positively by some and negatively by others. We refer to these assessments as legitimacy evaluations. Collectively, they contribute to an IO’s legitimacy, a phenomenon that is, therefore, best understood in relational terms rather than as an inherent IO characteristic.

Legitimacy evaluations of an IO do not materialise in isolation; instead, they are rooted in distinct legitimacy beliefs originating from the socially constructed framework of ideas, norms, and values embraced by a specific audience, referred to as sources of legitimacy beliefs.Footnote 17 When evaluating an IO, some may, therefore, prioritise democratic principles like openness, transparency, and accountability, while others may choose a neoliberal approach that favours efficiency and problem-solving.Footnote 18 The sources of legitimacy beliefs a specific audience relies on when evaluating an IO are not fixed but vary over time and across contexts. They constitute an integral part of the dynamic politics of legitimation that surrounds IOs. In this context, IOs endeavour to secure approval from their audience by crafting legitimisation narratives that validate their authority, actions, and decisions. Simultaneously, the audience observes these actions and justifications, evaluating them against their own set of values, norms, ideas, and objectives.Footnote 19

The sources of legitimacy beliefs are, therefore, a subject for empirical inquiry. They can be accessed by examining an audience’s legitimacy evaluations, communicated in written, spoken, or enacted forms (see Figure 1). In written and spoken form, these evaluations appear in an audience’s public statements across traditional and digital media, as well as on their websites. In an enacted form, an audience may express support or disapproval of IOs through actions such as collaborating with them as experts, participating in protests, or signing petitions. In this paper, we focus on feminist and conservative written communication. While this approach may sacrifice comprehensiveness, it is important to note that written communication still encodes spoken and enacted communication, such as when it refers to a particular speech, protest, or participation in IO spaces. Therefore, the study of written communication should enable us to gain a relatively robust understanding of the feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs’ evaluations of the UN and the legitimacy beliefs they are based on.

Figure 1. The relationship between legitimacy communication, legitimacy evaluations, and the sources of legitimacy beliefs.

Before discussing sources of legitimacy beliefs, a caveat is needed. Following Tallberg and Zürn, we classify feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs as part of the UN’s constituent audience – an audience that acknowledges its authority while also seeking to influence it.Footnote 20 However, while their engagement and evaluations matter for the UN’s legitimacy, they are not the sole measure of it. IO legitimacy is a complex aggregate of multiple audiences and the IO’s own legitimisation efforts. Nevertheless, examining these NGOs’ legitimacy beliefs can offer insight into the boundaries within which the UN is expected to set gender equality norms and ensure adherence.

Sources of legitimacy beliefs

As previously noted, the beliefs shaping legitimacy evaluations of IOs can originate from diverse sources. Within this section, we delve into those most frequently referenced within the IO legitimacy, social movements, and international NGO literature: IO procedure, IO performance, the audience’s ideology, access to resources, and the boomerang effect.Footnote 21 The literature generally treats these sources as distinct analytical categories. In reality, they often overlap. For instance, disentangling the ideologies of feminist and conservative NGOs from their assessments of the UN’s performance is not always a straightforward task, given that their ideologies typically inform these assessments. This intersection will be apparent in our empirical analysis. In this section, however, we address the sources of legitimacy beliefs as they are commonly described in the literature.

Procedure as a source of IO legitimacy beliefs

Max Weber was one of the first to highlight the importance of procedure in legitimacy, emphasising the proper administration of rules by authoritative figures through his concept of rational-legal authority.Footnote 22 Nowadays, the concept is given renewed importance through an emphasis on democratic procedural standards such as access, representation, participation, transparency, legality, and impartiality. Against the background of their rising authority, IOs are increasingly expected to uphold these standards.Footnote 23 Failing to do so opens the door for critics to question the validity of their actions and decisions, leading to negative evaluations of their legitimacy. Social movements criticising large economic IOs for being closed, opaque, and undemocratic are a case in point.Footnote 24 The same applies to state and non-state critics who have highlighted the EU’s democracy deficit or the UN’s inability to accurately represent global power distribution.

Performance as a source of IO legitimacy beliefs

The link between performance and legitimacy is a widely recognised topic in the study of domestic political institutions. The premise is simple: if a government performs well, it will likely earn the trust and support of its citizens, but if it performs poorly, it will likely provoke distrust and criticism. Similarly, it is now widely recognised that IOs acquire a portion of their legitimacy by delivering collective benefits to states and societies. Research on IOs such as the UN, WTO, IMF, and EU shows that an IO’s perceived ability to address issues is key to shaping positive legitimacy evaluations across different audiences.Footnote 25 Social movements protesting the mixed results of IMF adjustment programmes, and African governments opposing the International Criminal Court for its high prosecution rate of Africans, exemplify the negative relationship between organisational performance and legitimacy evaluations.Footnote 26

Ideology as a source of IO legitimacy beliefs

Liesbet Hooghe and colleagues highlight that legitimacy beliefs can also emerge from domestic contestation of IOs, driven by leftist and right-wing nationalist ideologies.Footnote 27 Leftist views vary depending on the specific organisation and its policies. Some leftist groups oppose IOs they perceive as promoting capitalist economic policies, such as austerity measures and free trade agreements, which they argue harm workers and the poor. They may also criticise IOs they see as serving the interests of powerful countries and corporations. However, some leftist groups support IOs that promote social justice, human rights, and environmental protection, viewing them as instruments for advancing progressive goals and holding powerful actors accountable.

As for right-wing and nationalist groups, they typically challenge IOs because they believe in promoting and protecting the interests, sovereignty, and independence of their nation above all else. They view IOs as threats to the autonomy of their nation and as forces that limit their ability to decide independently on issues such as immigration, trade, and security. They fear that IOs can dilute the power and influence of individual nations by pooling resources and decision-making authority. In their view, the important consequence of all these processes is the erosion of national identity and cultural heritage. Nationalists thus frequently point to the EU and the UN as IOs that interfere in domestic matters and erode sovereignty. Many also see NATO as an alliance that pressures nations into conflicts that do not serve their national interests.

Sources of legitimacy beliefs specific to NGO participation in IOs: Access to resources and the boomerang effect

Access to IOs alone can serve as a source of IO legitimacy beliefs among NGOs. However, the link between access and legitimacy becomes clearer when examining two key perspectives on NGO–IO relationships: the resource-based approach and the boomerang effect.Footnote 28 The resource-based approach to IO–NGO relations holds that NGOs enter IOs to ensure their own survival. By engaging with non-state actors, IOs benefit from NGOs’ policy expertise, agenda-setting capabilities, policy implementation support, and role in monitoring rule compliance.Footnote 29 For many NGOs, this creates an opportunity to exchange policy expertise for resources that many need to continue functioning. The more such resources are available, the more positively certain NGOs tend to evaluate an IO.

Developed by Margaret Keck and Katheryn Sikkink, the boomerang effect stands as one of the most influential approaches in the study of the IO–NGO relationship.Footnote 30 Sociologically rather than instrumentally inclined, the logic of the boomerang effect rests on the specific configuration of domestic and international opportunity structures. Simply put, it refers to a situation in which an NGO coming from a closed and potentially repressive domestic arena must seek allies at the international level if it wishes to achieve its aims. This strategy’s ultimate goal is to produce external pressure on the domestic arena, hence the use of the term boomerang. For certain NGOs, the existence of this opportunity structure will lead to a positive evaluation of an IO.

Based on these theoretical propositions, we proceed to our empirical analysis. First, we examine how feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs view the UN’s authority on women’s rights and gender equality. Consistent with our definition of IO legitimacy, we posit that recognising this authority is a first step in shaping their legitimacy perceptions of the UN. In this section, we mostly rely on secondary literature. To explore under what circumstances and based on which legitimacy beliefs these NGOs evaluate the UN more positively or more negatively, we take two additional empirical steps: one based on automated text analysis and the other on qualitative examination of selected texts.

Feminist and conservative NGOs’ perception of the UN’s authority

Feminist NGOs and the UN’s authority

Feminists have never represented a unified ideological bloc at the UN. According to Arat, they can be historically categorised into roughly seven broad groups.Footnote 31 During the early Cold War, liberal feminists prioritised individual rights and sought gender equality through legal and institutional reforms, while Marxist feminists opposed this approach, arguing that capitalism was the root of women’s oppression. In the 1970s, radical feminists carved out space to argue that patriarchy was the primary system of oppression, whereas socialist feminists linked gender inequality primarily to class exploitation. In the 1980s and 1990s, women of colour and postcolonial feminists further challenged neoliberal policies by connecting them to global structures of power and privilege. They also criticised mainstream liberal feminism for its cultural imperialism and its tendency to overlook cultural differences and local contexts.Footnote 32 These ideological debates ultimately paved the way for intersectional feminism in the 2000s, which analyses oppression through interconnected systems of race, class, gender, and other social hierarchies.

Over the years, each of these feminist actors has left its mark on the UN’s gender equality and women’s rights norms and policies. Yet, their overarching framework remains largely grounded in liberal feminism – a recurring point of contention and critique within feminist circles.Footnote 33 Nevertheless, the history of feminism at the UN is one of sustained engagement and meaningful influence. Following World War II, feminists pressured state delegations at the UN to secure recognition of ‘the equal rights of men and women’ in the UN Charter.Footnote 34 Furthermore, in 1946, they helped establish the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), the primary UN body promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment. During the Cold War’s ideological divide, international feminists faced challenges, but their movement grew in the 1970s. The UN responded by designating 1975 as International Women’s Year and hosting the inaugural World Conference on Women in Mexico City. This, in turn, led to the Decade for Women, marked by the adoption of the landmark Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Feminist groups contributed by offering expertise, raising awareness, and advocating for the ratification and implementation of CEDAW. Subsequently, the UN organised three more women’s conferences in Copenhagen (1980), Nairobi (1985), and Beijing (1995), drawing thousands of women’s rights activists.Footnote 35 These conferences, although convened by states, played a crucial role in amplifying feminist movements and advancing their agenda on the global stage.Footnote 36 They provided feminists with opportunities to strategically frame their issues, forge coalitions, and exert incremental influence within the UN system.Footnote 37

The 1990s were a particularly transformative period for transnational feminism, with the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995) as a pivotal moment. Over 4,000 NGO representatives united to champion gender equality, sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), and women’s empowerment.Footnote 38 Beijing showcased the potential of organised advocacy at the UN, leading to landmark achievements such as the inclusion of gender-based violence in the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and the 2000 adoption of Security Council Resolution 1325, recognising the disproportionate impact of armed conflict on women and girls.

Building on these achievements, feminist NGOs have cultivated a strong sense of ownership of the UN, viewing it as an essential platform for advancing their causes, regardless of ideological differences. Many feminist NGOs, therefore, recognise the UN’s authority, defined here as the acceptance of its right to establish norms, make decisions, and interpret policies in the area of gender equality and women’s rights. However, far less is known about their legitimacy evaluations of the UN, the beliefs that shape these evaluations, their consistency over time, the patterns of their variation, and how they compare to the legitimacy evaluations and beliefs held by conservative NGOs.

Conservative NGOs and the UN’s authority

Unlike women’s rights activists, anti-feminist NGOs have not traditionally embraced transnational organising and advocacy within the UN. One of the reasons has been their profound scepticism of the UN’s authority. The Christian right in the United States has gone so far as to portray it as an agent of the Antichrist, actively working to consolidate global power into a single governing body, ultimately bringing about the apocalypse.Footnote 39 They have perceived the UN as vulnerable to infiltration by ‘radical’ progressive NGOs and staffed by democratically unaccountable bureaucrats. They also view it as a feminised institution, susceptible to pro-abortion and anti-family influences. Multiple UN agencies, but most prominently the WHO and UNPFA, have been on the receiving end of this critique.

In the past decades, however, conservative NGOs have undergone a notable transformation in their perception of the UN’s authority. As Buss and Herman detail in their in-depth study of how the Christian right perceives the UN, particularly within leading organisations such as the Center for Family and Human Rights (C-Fam), a new perspective has emerged, one portraying the UN as a fundamentally virtuous organisation that aligns with Christian values.Footnote 40 However, this viewpoint comes with a twist: while the UN is seen as a force for good, it is believed to have been infiltrated by progressive influences, particularly those supporting anti-family agendas. It is depicted as teetering on the edge of secularist dominance, prompting a call to rescue the organisation from this fate. Their goal is, therefore, no longer the abolition of the UN but rather its transformation in line with conservative values and what they perceive as its original purpose. As a result, in the past decade, the number of conservative NGOs in the UN has steadily increased. They now form part of a broader alliance that spans many Islamic and post-Soviet states as well as the United States during Donald Trump’s administration, and occasionally includes groups like the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the League of Arab States, the UN Africa Group, and the G77.Footnote 41 They are united by their opposition to ‘gender ideology’ and desire to restore traditional values, particularly ‘the natural family’.Footnote 42 Importantly, their efforts have already influenced the UN’s normative framework. The Human Rights Council adopted pro-family resolutions annually from 2014 to 2017, while ‘parental rights’ appeared in three General Assembly resolutions on children in 2017. At the same time, conservative NGOs and sympathetic states actively block and weaken progressive language in UN documents. A key victory was the 2019 removal of ‘sexual and reproductive health’ from the Women, Peace, and Security resolution, reflecting broader opposition to terms like ‘safe abortion’, ‘sexual orientation and gender identity’, and ‘women in all their diversity’ in key UN bodies, including the Commission on the Status of Women, the General Assembly, and the Human Rights Committee.Footnote 43 In sum, while many conservative NGOs now accept the UN authority, as in the case of feminist NGOs, questions remain about the variation of their legitimacy evaluations and underpinning legitimacy beliefs.

Feminist and conservative NGOs’ legitimacy evaluations of the UN

To discern feminist and conservative NGOs’ legitimacy evaluations of the UN and the sources of legitimacy beliefs on which they are based, we rely on a mixture of methods. We utilise the strengths of automated methods that are able to deal with large amounts of data to display overarching trends across time. This is important, since we are interested in connecting changes with external factors, such as changes at the UN level. First, to handle extensive data and track trends over time, we utilise automated content analysis. This approach serves two main purposes: first, it helps us gauge the UN’s visibility in the communications of these NGOs, and second, it enables us to estimate sentiment towards the UN, serving as a proxy for legitimacy evaluations. Although this method allows us to cover vast data sets and an extended time frame, it only quantifies a proxy measure without further contextualising patterns. To reveal the sources of legitimacy beliefs shaping these evaluations and provide information on the textual content beyond trends, we additionally make use of the advantages of qualitative techniques. With an in-depth analysis of exemplary documents from key time frames, we are able to contextualise patterns, connecting them to events or dynamics at the UN level. Combining these methods, we create an analysis pipeline that first uncovers dynamics in a large corpus through the automated approach, exposing important time frames to ascertain the sources of legitimacy beliefs of NGOs. Second, through qualitative examination of sampled key documents from these decisive time points, we are able to conduct an in-depth analysis of the sources of legitimacy beliefs and the contexts in which they are discussed.

Data and methods

Data. For the analysis, we selected NGOs that hold an active status in ECOSOC and have a proven record of advocacy around gender equality and women’s rights. To identify such NGOs, we primarily relied on programmes from CSW NGO side events. Additionally, we consulted reports such as the 2021 ‘Rights at Risk: Time for Action’ by AWID. This approach led us to select ten NGOs we classified as conservative and eleven as feminist and feminist-informed, ensuring ideological diversity to reflect real-world variety (see Table 1). The feminist NGOs we selected represent a wide range of different strands of feminism currently informing the UN. Some are also large organisations where feminist issues are just one part of their broader agenda, hence the feminist-informed label rather than strictly feminist. Conservative NGOs are more uniform ideologically, although they differ in religious affiliation and operational reach. They also skew Western and US-based. Although this may introduce bias into our sample, it reflects the reality that Western groups hold the most resources for transnational advocacy.

Table 1. Number of cases and sentences across NGOs.

Selected feminist and feminist-informed NGOs fall into four categories. Decolonial and intersectional feminists critique global inequalities by challenging power structures, capitalism, and patriarchy while examining race, gender, and class intersections. This group includes AWID, which coordinates the OURS Observatory monitoring anti-rights groups; DAWN, a feminist global south network that resists Western-dominated feminism while promoting SRHR, and economic and climate justice; ARROW, advocating for SRHR as part of locally driven policies; and Fòs Feminista, expanding access to sexual and reproductive health services. Liberal feminists focus on policy reform, legal advocacy, and gender mainstreaming, including EWL, Europe’s largest women’s NGO network; IAW, with suffragist roots; ISHR, promoting gender-sensitive human rights protections; and the Heinrich Böll Foundation, integrating gender equality and ecofeminism. Anti-militarist feminists critique patriarchy’s links to militarism, economic exploitation, and gender-based violence, with WILPF leading advocacy for disarmament, gender-sensitive peacebuilding, and bodily autonomy. Developmental feminist-informed organisations address gender justice in global development, with CARE International linking women’s issues to humanitarian aid, economic empowerment, and climate resilience, while Plan International prioritises girls’ rights, education, and protection from gender-based violence.

What justifies grouping and analysing these organisations as a single unit? There are two main reasons. First, despite ideological differences and varying scopes of action, all have a strong record of jointly advocating for gender equality and women’s rights at the UN. In different formations, they collaborate through actions such as coordinated advocacy campaigns, joint statements, and feminist coalitions. Many are part of the Women’s Rights Caucus, advocating for gender equality at the CSW, and contribute to Generation Equality, a UN initiative countering anti-feminist forces’ impact on gender justice. Second, they have increasingly mobilised directly in response to growing opposition from conservative religious groups. For example, in November 2024, AWID hosted the Rising Together forum in Bangkok, convening 3,500 feminists to strategise, among other things, on resisting conservative ideologies in global arenas like the UN.Footnote 44 In short, while these organisations do not yet form a unified feminist bloc within the UN, they are part of a broader feminist resistance network.

The conservative religious organisations selected for our analysis can be categorised into three broad groups based on their religious affiliation and strategic focus: evangelical Protestant groups, Catholic traditionalist organisations, and interfaith right-wing think tanks. Evangelical Protestant organisations (ADF, FRC, FWI, and UFI) push a Christian nationalist agenda through litigation, grassroots mobilisation, and policy lobbying. They frame gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights as threats to religious freedom and advocate for policies such as ‘parental rights’ to block sexuality education. Catholic traditionalist organisations (C-Fam, IYC, HLI, and PRI) promote anti-abortion, anti-contraception, and pro-family policies, often aligning with Vatican interests. Interfaith right-wing think tanks (including the Heritage Foundation and CitizenGO) function as policy influencers and digital mobilisation platforms. They blend evangelical and Catholic conservative agendas, producing reports, training leaders, and launching campaigns against gender justice and feminist movements.

We group these organisations under the broader category of conservative religious organisations because they not only share an anti-feminist and anti-gender agenda at the UN but also actively promote traditional patriarchal values. Moreover, they employ similar strategies, such as using shared talking points (e.g., ‘gender ideology’), frequently collaborate and coordinate, and participate in events like the World Congress of Families. They also form coalitions within UN spaces, such as the UN Family Rights Caucus and Civil Society for the Family.

Our data set consists of documents, such as press releases, blogs, or news updates, feminist and conservative NGOs published on their websites from 2012 to 2022. While we could examine direct NGO–UN communication and content from other sources, we contend that the documents from NGOs’ websites represent their public outreach to diverse stakeholders. Within this communication channel, they digest their exchange with the UN but are not restrained by ‘official language’ that might be used when submitting documents to UN bodies and meetings, potentially describing relations with the UN more openly. In addition, this form of communication provides details as documents are much longer compared to, for example, social media, not simplifying issues, which is vital to contextualise dynamics as we do in the in-depth part of the analysis. The timespan of ten years is motivated by two factors. First, it covers newly emerging dynamics between feminist and conservative NGOs within the UN. Second, it ensures a solid data basis since this time marks the period when these NGOs significantly intensified their use of websites for disseminating information.

For both groups of NGOs, we identified their websites and scraped all available content as of early 2022. After narrowing our timespan to the period between 2012 to 2022 and excluding all static documents such as ‘About us’ sections, we ended up with a corpus of 23,777 documents (16,477 for conservative NGOs and 7,300 for feminist and feminist-informed NGOs). In preparation for the analysis steps, we tokenise the data on the sentence level, yielding a corpus of n = 651.180 sentences (461,067 for conservative NGOs and 190,113 for feminist and feminist-informed NGOs; for a detailed overview, see Table 1).

Dictionary approach. A key step for our analysis is to automatically identify UN entities (i.e., mentions of the UN and its subsidiaries) within the documents. To achieve this, we constructed an extensive dictionary to measure occurrences. Being a bag-of-words approach, dictionaries are not interested in the grammatical structure of a text but in the mere presence and frequency of words from a predefined list, indicating the presence of a certain construct.Footnote 45 To compile the list of UN entities, we first drafted terms consisting of UN bodies and landmark documents based on our own expert assessment. In a second step, this list was refined in an iterative process of manual coding. Two independent coders were tasked with individually annotating a selection of texts from the corpus to identify and collect mentions of the UN. In three rounds, the coders worked their way through 700 documents, adding new keywords to the initial list. To validate the resulting list, a final round of manual coding using a fresh sample of 1,000 documents was implemented, with intercoder-reliability tests showing that both coders annotated with sufficient overlap, with Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.76. In this stage, no new terms were added to not risk overfitting the tool. According to the measures, the dictionary performs well with recall = 0.84, precision = 0.77, and F1 = 0.84. The complete list of keywords can be found in the Appendix.

Visibility. To confirm the significance of the UN in the communication of the NGOs, thereby also validating our sample selection, we assessed the UN’s visibility throughout the entire corpus using our dictionary. This approach yielded binary scores indicating the presence or absence of a UN entity. Investigating the salience over time, we calculated the share of documents mentioning the UN at least once each month, resulting in a visibility score that ranges from 0 (indicating that no document mentioned the UN) to 1 (indicating that all documents reference the UN in a given month).

Semantic role labelling. We further break down sentences that mention the UN and its subsidiaries into narratives, with the aim of identifying semantic roles within their grammatical structure. This approach, called semantic role labelling (SRL), allows us to identify an agent, meaning the acting entity, the verb, the action, and a patient, the affected party or an object.Footnote 46 Going beyond simple bag-of-words approaches, this technique examines words in their contexts. Using the pre-trained model AllenNLP, it leverages grammatical structures to infer semantic roles and relations.Footnote 47 Aggregated to the sentence level, this approach is used to identify whether the UN is referred to as an agent or patient, facilitating the measurement of sentiment expressed toward the UN.

Sentiment. We measured sentiment, serving as our proxy for legitimacy evaluations, using a semi-supervised scaling approach, namely latent semantic scaling (LSS).Footnote 48 This approach enables us to position sentences along a spectrum between negative and positive sentiment. By using a combination of predefined seed terms and word embeddings, this method permits a certain level of supervision with researchers being able to guide the process with available knowledge still considering the flexibility to deal with large amounts of data. The LSS approach implements word embeddings to represent text as ‘word vectors’, a low-dimensional representation of word semantics. Using the provided seed terms as starting points, this technique calculates the proximity (cosine similarity) of vector representations of other words in the documents to this initial selection, eventually yielding a polarity score that allows for locating a text unit on a scale.

The list of seed words was compiled with two considerations in mind. First, the terms should represent the target dimension meaningfully and be theoretically motivated. All terms presented in the upper section of Table 2 are drawn from the 2,858 negative and 1,709 positive words from the Lexicoder Sentiment Dictionary (LSD) – an established collection of words indicating negative and positive sentiment in political texts – and assessed for fit with our data.Footnote 49 Second, all seed terms should appear within the corpus. Since feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs employ different vocabularies, we designed two independent models, warranting reliable results. The approach was implemented on the sentence level, using the R package LSX.Footnote 50

Table 2. Sentiment scaling. Seed words and example sentences for both poles.

Note: The asterisks denotes a wild card, allowing the model to find words with varying endings.

To ensure valid implementation of the approach, two independent coders annotated 2,000 sentences (n = 1,000 for conservative NGOs and n = 1,000 for feminist and feminist-informed NGOs) regarding their sentiment (very negative (−2), negative (−1), neutral (0), positive (1), very positive (2)), reaching an intercoder-reliability score of Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.74. Comparing the manually coded material with the predictions of the LSS approach using the selection of seed words from Table 2, we find satisfactory levels of correlation on an aggregated level (r = 0.77 for conservative NGOs and r = 0.81 for feminist and feminist-informed NGOs), following the validation procedures implemented by earlier studies using LSS.Footnote 51 In the results, higher scores signify greater positive sentiment toward the UN, while lower scores indicate a more negative perspective. Example sentences for each group of NGOs are listed in the lower part of Table 2.

Analysis. In the following section, we present our analysis in three steps. First, we examine the UN’s visibility in the communication of feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs over time. Second, we present the sentiment expressed by these NGOs towards the UN over time, treating it as a proxy for their legitimacy evaluations. Third, we infer the primary sources of legitimacy beliefs underpinning these evaluations. To do so, we identify points in time depicting certain dynamics such as peaks, dips, or specific longer-lasting trends, and select exemplary documents for qualitative inspection. In total, a set of sixty documents was drawn based on the particular timeframe (for an overview, see Appendix) and distinct sentiment scores of single sentences within the documents. However, as many documents contain sentences with similar sentiment scores, our selection process was further influenced by the aggregated sentiment score at the document level. Additionally, we made sure to include documents crafted by various NGOs to ensure variation of sources, preventing this analytical step from being driven by a single NGO in our selection. Therefore, the resulting collection of documents showcases positive and negative communication of a diverse set of NGOs towards the UN during distinct time periods, communication that is instrumental in driving the dynamics observed in preceding steps. The analysis of the selected sixty documents eventually involved a thorough reading of each to establish two key aspects: firstly, the central subject or subjects of each document, such as the Millennium Development Goals, abortion, or a CSW meeting; and secondly, which legitimacy beliefs informed the document’s positive or negative evaluation of the topic and the UN, whether it was issues concerning performance, procedure, ideology, resources, or the boomerang effect.

Results

Visibility of the UN in feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs’ communication

Examining the monthly communication of feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs reveals that the UN holds not only theoretical significance for them but also plays a vital role in their interactions with the public. Figure 2 shows that for feminist and feminist-informed NGOs (dashed line), during certain months, more than half of the documents published on their websites relate to the UN, mentioning it at least once. Importantly, the importance grows across the entire time frame with a less steep increase following 2016 and a plateau-like pattern following 2020. In contrast, conservative NGOs (solid line) are less concerned with the UN; visibility remains, for most of the time, at around 20 per cent. A closer look reveals that they are oftentimes more concerned with national issues. Although there is a noticeable spike in attention toward the UN in 2016, possibly influenced by Donald Trump’s rise to power, there is a general, gradual decline in visibility over time. However, considering the diverse range of actors and issues involved, the UN remains a crucial component of conservative NGOs’ communication.

Figure 2. Visibility of the UN within feminist and feminist-informed and conservative NGOs’ communication over time.

Feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs’ legitimacy evaluations of the UN (sentiment analysis)

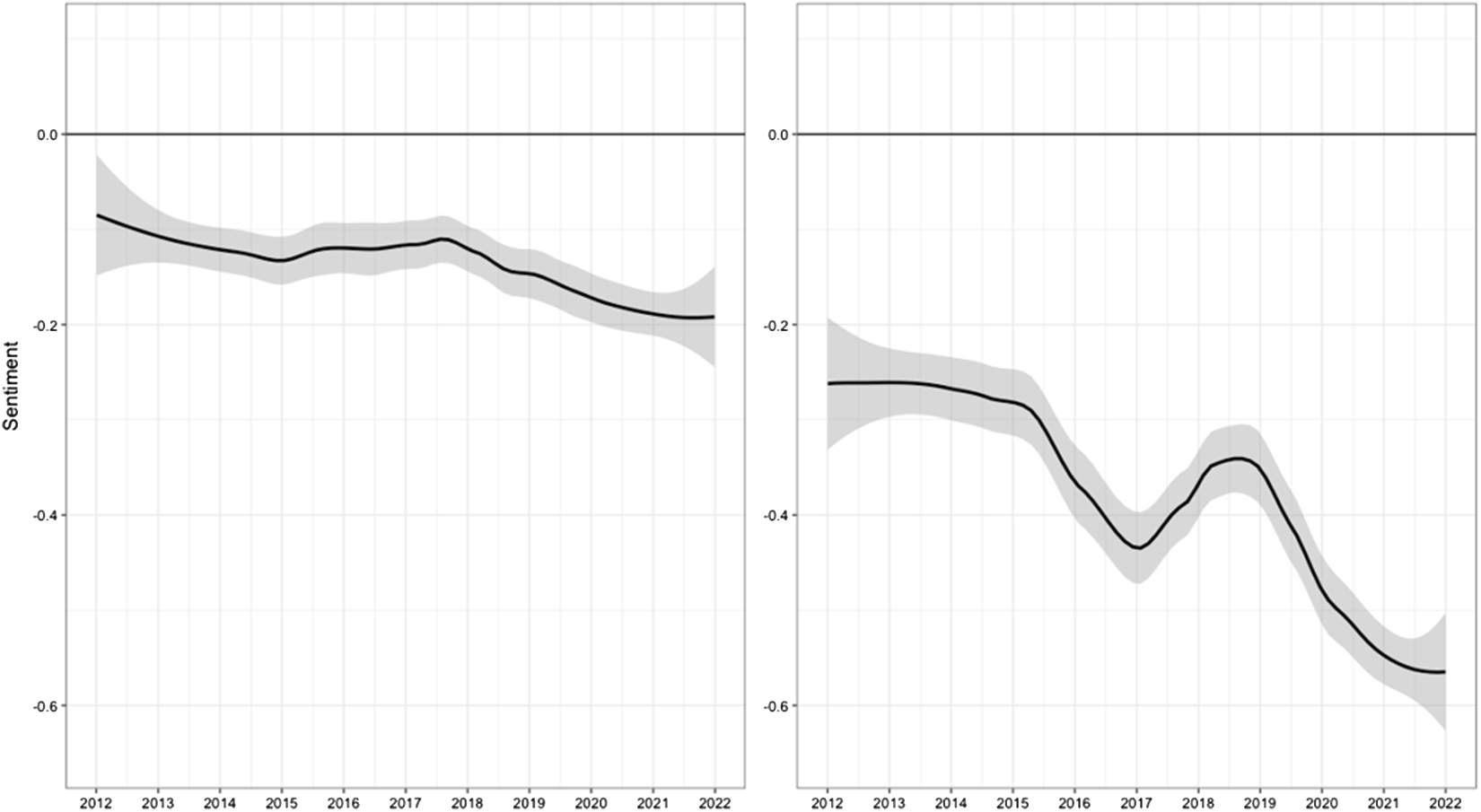

The two graphs presented in Figure 3 reveal a clear and compelling trend: feminist and feminist-informed NGOs, over the period spanning from 2012 to 2021, on average and at every point in time, are more positive when addressing the UN as compared to their conservative counterparts. We interpret this to indicate a prevailing tendency among feminists to regard the UN as a more legitimate organisation than conservatives do. However, for both camps, the sentiment expressed towards the UN remains below the level of the mean sentiment they express in their overall communication, as denoted by the horizontal lines in both graphs in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Sentiment expressed towards the UN by feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs over time. Notes. Smoothed time trends with 95 per cent confidence intervals for scaled sentences, where the UN is identified as the ‘agent’ or ‘patient’ within a sentence, are shown. Horizontal lines depict mean sentiment expressed by the respective group in their overall communication. N = 9.754 for conservative NGOs, N = 13.820 for feminist NGOs.

Feminist NGOs, as shown in the left graph in Figure 3, are gradually seeing the UN more negatively. Exhibiting a slight dip in 2015 and a mild peak between 2017 and 2018, we observe a somewhat steeper decline in sentiment following 2019. All of these dynamics describe the patterns observed for these NGOs as a whole, as we cannot see any single NGO driving particular dips or peaks (see Figure A1 in the Appendix).Footnote 52 For conservative NGOs, on the other hand, we see distinctly more fluctuation. While more or less steady until 2015, the sentiment towards the UN gets significantly more negative with a clear dip in 2017. As the right graph in Figure 3 shows, texts touching upon UN matters get more positive afterwards with a distinct peak mid-2018, followed by a steep negative drift until the end of the investigated time period. For this group of NGOs, we similarly looked at the disaggregated scores (see Figure A2 in the Appendix),Footnote 53 indicating that, while overall dynamics describe patterns of most individual NGOs well, the peak in 2017 is particularly driven by the Heritage Foundation. The trends in the displayed sentiment scores raise questions about the sources of legitimacy beliefs driving these evaluation patterns. In order to delve more deeply into this issue, we focused on the distinct periods mentioned here. The results of this qualitative analysis are reported in the following section.

Feminist, feminist-informed, and conservative NGOs’ sources of legitimacy beliefs about the UN

Feminist and feminist-informed NGOs. In 2015, feminist and feminist-informed NGOs exhibited a minor negative shift in their evaluation of the UN. An examination of the documents they released during that time reveals that this change was principally driven by their discontent with the UN’s performance, interpreted through the lens of their ideology, and problems related to the UN’s procedures, particularly being denied access to significant UN forums.

The dissatisfaction of these NGOs with the UN’s performance was mainly focused on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). As the implementation of these goals was coming to a close and preparations were underway for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), feminists’ discontent centred on the numerous unmet targets. Essentially, they were more concerned with the UN’s inaction than its actions, with some even labelling the MDGs as a global failure that led to seven wasted years (ID: 5910).Footnote 54 They perceived the progress as sluggish and inconsistent across various countries and regions, with maternal and child mortality notably experiencing the least improvement (ID: 851). Consequently, they urged that the upcoming SDGs strengthen the connection between development and human rights, particularly women’s rights and sexual and reproductive health and rights (ID: 333, 5866).

A procedural reason for the negative evaluation of the UN by feminist and feminist-informed NGOs in 2015 was their exclusion from the CSW negotiations commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the Beijing Declaration (ID: 814, 823, 3576). States decided to draft a political declaration before civil society could convene in New York (ID: 823). Feminists found this exclusion deeply troubling, given their long history with the CSW and the fact that the Beijing Declaration, their brainchild and a major UN success, was at stake. Their concerns were further exacerbated by the content of the political declaration, which they saw as weak and ahistorical (ID: 823). The declaration not only failed to recognise the feminist contribution to the Beijing Declaration but also overlooked essential issues such as gender-based violence, an inclusive definition of women and girls, and sexual and reproductive health and rights (ID: 823). Feminists also noted that this development significantly empowered their opponents, conservative anti-rights groups (ID: 823).

In 2017, there was a slight improvement in the feminist perception of the UN compared to the previous period. This shift was also driven by their positive evaluation of the UN’s performance and procedures, particularly regarding its agencies and special representatives. Accordingly, the feminist and feminist-informed NGOs expressed approval for various actions within the UN, such as the Human Rights Council’s (HRC) decision to extend the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders (ID: 5060, 5020, 5093), the appointment of the UN’s first expert on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) (ID: 5029), the strengthening of the UN’s treaty bodies, particularly the one on CEDAW (ID: 4986), UNESCO’s initiatives in the realm of women and girl empowerment (ID: 9217), and the second High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) holding sexual and reproductive health and rights in high regard (ID: 183). Importantly, in all these instances, these NGOs positively assessed the willingness of the UN’s bureaucracy and special representatives to grant them access and foster collaboration. This, as we will show below, was a source of great irritation for conservative NGOs.

From 2020 to 2022, we observe a steady downtrend in the feminist evaluation of the UN. Understanding this decline requires noting the context of those years: the COVID pandemic, worsening climate change, and a worldwide strengthening of conservative and far-right groups. As before, the feminist critiques of the UN centred primarily on the organisation’s procedures and performance.

Regarding procedures, the COVID pandemic hindered the in-person attendance of feminist and feminist-informed NGOs at many crucial UN meetings. In their words, they were ‘locked out during lockdown’ (ID: 6283). They observed that, particularly in meetings related to human rights, disarmament, and peace and security, issues such as travel restrictions, the global south’s unstable internet access, time zone challenges, and other similar problems all impeded the meaningful participation of NGOs in UN processes (ID: 6283, 459). Adding to their frustration was the perceived hypocrisy, whereby, for example, in 2021, access to the Third Committee of the General Assembly was granted to member states, UN staff, and resident journalists but not to them (ID: 4190).

Besides fearing that the COVID pandemic was being leveraged as a pretext to marginalise civil society within the UN, feminists raised concerns about how this exclusion reflected in the UN’s performance. The outcome documents from numerous meetings and UN actions seemed to persistently overlook or advance a weaker understanding of gender equality and women’s rights. At the same time, concerns grew that anti-rights conservatives were gaining ground (ID: 1139), with funding being an important area of concern. They observed that, amid the COVID-induced setbacks in gender equality and women’s rights, ‘feminist funding pales in comparison to anti-feminist and anti-LGBT funding’ (ID: 451).

Conservative NGOs. In 2017, the conservative NGOs’ evaluation of the UN declined sharply, reaching its lowest point since 2012. This negative evaluation was based on the UN’s performance, interpreted through the lens of their ideology, as well as procedural matters that underscored this performance. Regarding the UN’s performance, conservatives’ main criticisms were aimed at various UN agencies, including the WHO, UNFPA, CCPR, and different UN-specialised representatives. They accused the WHO of promoting the use of contraceptives in sub-Saharan Africa that increased women’s risk of HIV and criticised UNFPA for supporting sterilisation and coercive abortion, especially in connection with China’s one-child policy (ID: 15658, 20040). They asserted that UNFPA claims to be a great champion of diversity, but it is the ‘greatest destroyer of cultures, customs, and faith of developing nations in existence today’ (ID: 29761). Furthermore, they blamed the WHO for attempting to establish a customary international right to abortion by publishing interactive databases on global laws and policies, a move they saw as an effort to pressure states to conform to the recommendations of UN agencies and bureaucracy (ID: 16009). Regarding the CCPR, they condemned it for pressuring Ireland, without legal grounds or a clear mandate, to legalise abortion (ID: 30798).

Herein also lies their procedure-based critique of the UN agencies. They assert that these agencies act without legal basis concerning abortion and related practices. No UN document, they maintain, establishes the right to abortion, and although phrases such as ‘sexual and reproductive health and rights’ are mentioned in several landmark documents, they argue that these cannot be used as a surrogate for this right. To them, these actions represent not merely an overreach but a malicious and biased expansion of the agencies’ mandates, constituting a clear deviation from what they believe should be the UN’s core principles and responsibilities.

In mid-2018, the public communication of conservative NGOs regarding the UN became significantly more positive, with two reasons standing out. The first is their attempt to claim ‘ownership’ over the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) on its seventieth anniversary (ID: 10158, 11961, 10126). Instead of rejecting the UDHR as a progressive and liberal human rights instrument, conservatives have embraced it, yet they sought to advance an originalist interpretation of this document (akin to their approach to the US Constitution). Consequently, they urge the UN to interpret the UDHR’s provisions – such as the right to life, the understanding of the family, and religious freedoms – in line with the conservative perspective.

The second reason for the more positive evaluation of the UN during this period stems from the increasingly fruitful collaboration between conservative NGOs and sympathetic UN member states, such as the Holy See and states belonging to the Group of Friends of the Family. Counterbalancing their conflicts with UN agencies and bureaucracy, conservative NGOs targeted their advocacy towards UN state actors. This strategic realignment proved successful in 2018, leading to strong opposition against feminist agendas in several UN fora (ID: 30209, 31595, 15958, 15961).

Similar to feminist NGOs, the period between 2020 and 2022 saw a steady downward trend in conservative evaluations of the UN. However, this decline was much steeper for conservatives. While the COVID-19 pandemic was also a focal point for them, the concerns of conservative NGOs were less about restricted access for civil society and more about the UN agencies’ performance during this time. Procedural issues were still pertinent but closely interwoven with performance-related critiques.

The central concern for conservative NGOs during this period was the way the UN and its agencies were categorising abortion and sexual and reproductive health and rights as essential healthcare issues, including them as part of their pandemic-related humanitarian assistance (ID: 28861, 15832, 19405). They staunchly argue that abortion is not the same as food or shelter, with one organisation asserting that the WHO, which should, by virtue of its name, be promoting health, has instead become one of the leading organisations promoting ‘the suppression of life’ rather than an ‘openness to life’ (ID: 28861). The WHO also faced accusations of collusion with China regarding an alleged cover-up of early pandemic warnings (ID: 26600).

Regarding procedural critique, much like in previous periods, conservatives accused UN agencies of deceptive tactics. They charged them with employing a ‘stacking’ strategy in their humanitarian assistance packages. Specifically, they claimed that humanitarian aid was made contingent on the target countries’ acceptance of sexual and reproductive health and rights provisions (ID: 19405). This was seen as a manipulative approach, leveraging essential aid to promote particular values or policies that were not universally accepted.

Discussion

Besides showing that feminist and feminist-informed NGOs on average view the UN more positively than conservative NGOs, our analysis revealed that, over the past decade, these NGOs have evaluated the UN most positively when its performance and procedures resonated with feminist ideological orientation. In terms of performance, this mainly relates to their appreciation of the UN’s bureaucracy, agencies, specialised bodies, and special representatives when promoting gender equality and women’s rights. On the procedural front, they underscore these actors’ readiness to engage in close collaboration with feminist and feminist-informed NGOs. Performance and procedure as sources of legitimacy belief have also been central to these NGOs’ most pronounced negative evaluation of the UN. Performance-wise, they fault the UN for not adequately implementing gender equality and women’s rights commitments and often overlooking these concerns in its critical human rights and developmental policies. In the last decade, this criticism has been especially pronounced in relation to the UN’s approach to MDGs and its COVID responses. On the procedural front, their primary grievance is their exclusion from key UN fora, which, they argue, does not just curtail their advocacy efforts but also weakens the UN’s transparency and accountability. They note that this sidelining has coincided with a rise in conservative voices. While feminist and feminist-informed NGOs, in principle, support diverse civil sector representation in the UN, they view the growing influence of conservative NGOs as a barrier to their goals, leading to a more negative evaluation of the UN. Instrumental concerns about resource availability have also influenced their criticism during the studied period. This criticism too is linked to the rise of conservative NGOs, perceived to have significantly greater access to funding. We found no evidence of the boomerang effect – an instance where engagement with the UN is explicitly connected to specific repressive contexts affecting local feminist activists – playing a role in feminists’ positive or negative evaluation of the UN.

Conservative NGOs evaluated the UN most positively when advancing the ‘originalist’ interpretation of its foundational texts, most prominently the UDHR. This cannot strictly be related to any of the sources of legitimacy beliefs we listed, pointing to a possible source of legitimacy beliefs that IO literature overlooks: one gained through asserting ownership over an IO’s normative outputs. While feminists can claim such ownership due to their pivotal role in shaping the UN’s key documents and feel snubbed when this contribution is ignored, conservatives lack such a historical claim. Instead, they position themselves as guardians of the original interpretations of the UN’s landmark human rights documents. The conservative NGOs’ more positive evaluation of the UN is further linked to procedural elements, such as their alliance with conservative states, which grants them access to and influence over UN decisions and performance. Procedural and performative issues, rooted in rigid ideological standpoints, emerge as the main drivers behind conservative NGOs’ most pointed critiques of the UN. Contrary to feminist and feminist-informed NGOs, conservative NGOs view the UN with particular disdain when its bureaucracy, agencies, and special representatives champion progressive views, notably on issues like abortion, sexual orientation and gender identity, and sexual and reproductive health and rights. While their criticisms are based on performance, they also carry significant procedural reservations. Yet, unlike feminists, their procedural concerns are not predominantly about participation, transparency, or accountability, though these matters are not trivial to them. Instead, they primarily criticise UN actors for maliciously and deceptively overstepping their mandates and deviating from the UN’s foundational principles. A particularly salient criticism accuses these actors of coercing developing nations into embracing progressive objectives.

Conclusion

Employing a mixed-method approach and making a conceptual distinction between sources of legitimacy beliefs and legitimacy evaluations, the paper has explored under what circumstances and holding which legitimacy beliefs feminist and feminist-informed NGOs, and conservative NGOs, are most inclined to evaluate the UN positively or negatively. The study was comparative in nature: it aimed to examine how feminist and conservative NGOs perceive and engage with the UN while confronting each other. As such, we aimed to provide a possible novel approach for studying IO legitimacy in the context of the ongoing illiberal backlash. Current literature often casts illiberal factions as the main challengers of the liberal international order. However, our findings indicate that while feminists generally view the UN more positively than conservatives, the presence and influence of conservative NGOs prompt them to also give a less positive evaluation, though not yet amounting to outright contestation. Conversely, conservative NGOs are not merely contesting the UN but also striving to claim ownership over it and its normative framework. While they reject the liberal normative framework, they nonetheless maintain a commitment to the UN itself. We believe this comparative and relational insight, which challenges black and white portrayals of liberal and illiberal factions, could serve as a foundation for further research into illiberal challenges to the liberal international order.

An important question for both future research and practice is: What does this mean for the UN and its ability to exercise authority on gender equality and women’s rights? The UN has to find a way of dealing with an ideological split that is becoming increasingly clearer. Feminist NGOs are becoming more vocal in their calls for the UN to take concrete actions that would support and encourage feminist engagement. They also advocate for the UN to actively combat conservative attacks rather than allowing them to go unchallenged or recognised as legitimate civil society participants. The primary targets of these calls are the UN bureaucracy, various UN mandate holders, and the states known for their progressive outlook – the very agents conservative NGOs associate with their negative evaluation of the UN. The consequence of this split is growing distrust in the UN on both the feminist and conservative sides and a diminishing overall legitimacy of the organisation, which hampers its capacity to establish new rules and norms regarding gender equality and women’s rights and to enforce those previously adopted. It remains to be seen and subject to further research what measures, if any, the UN can undertake to bolster its legitimacy in this domain while avoiding being accused of silencing the diversity of voices that it officially supports.

Appendix

Dictionary UN actorsFootnote 55

united nation, un, unhq, security council, unsc, sc, p5, general assembly, unga, ga, first committee, second committee, third committee, human rights committee, fourth committee, fifth committee, sixth committee, 1st committee, 2nd committee, 3rd committee, 4th committee, 5th committee, 6th committee, department of economic and social affairs, desa, secretary general, sec gen, unsg, sg, usg, special envoy, sesg, economic and social council, ecosoc, commission on the status of women, csw, fourth world conference on women, beijing conference, beijing declaration, platform for action, beijing pfa, pfa?, beijing committee, beijing20, beijing + 20, bejing25, beijing + 25, beijing + 25, youth forum, committee on the elimination of discrimination against women, cedaw, entity for gender equality and the empowerment of women, unifem, civil society advisory, csag, trust fund, trust fund to end violence against women, women asia and the pacific, women office, international research and training institute for the advancement of women, international research and training institute, instraw, lgbtqi + core, commission for social development, csocd, commission on social development, economic and social commission, escap, economic commission, ece, unece, non-governmental liaison service, ngls, committee on non-governmental organizations, committee on ngo, ngo committee, human rights council, human right council, council of human rights, unhrc, hrc, human rights mechanisms, commission on human rights, unchr, chr, human rights commission, office of the high commissioner for human rights, ohchr, human rights office, high commission, working group on arbitrary detention, wgad, working group on business and human rights, wgbhr, committee on the elimination of racial discrimination, cerd, committee on economic, social and cultural rights, cescr, committee on the protection of the rights of all migrant workers and members of their families, cmw, committee on the rights of the child, child rights committee, crc, special rapporteur, human rights committee, committee on human rights, high commissioner for refugees, refugee agency, unhcr, international organi(z|s)ation for migration, iom, relief and works agency for palestine refugees in the near east, unrwa, unicef, children fund, world health organization, world health organisation, world health assembly, programme on hiv and aids, program on hiv and aids, unaids, hiv/aids agency, food and agriculture organi(z|s)ation, fao, international labor organi(z|s)ation, ilo, world food program, wfp, food system summit, industrial development organization, unido, world truism organi(z|s)ation, unwto, population fund, unfpa, fpa, population (agency|group|unit), population control agency, population control organi(z|s)ation, fund for population, family planning fund, reproductive health fund, icpd + 20, maternal and newborn health thematic fund, maternal health fund, mhtf, international conference on population and development, icpd, cairo international conference, cairo + 20, icpd, population division, commission on population and development, cpd, population and development commission, population information network, popin, undp, development program, development (fund|agenda|system|partner), conference on environment and development, unced, rio de janeiro earth summit, rio summit, rio conference, earth summit, world summit on sustainable development, rio +, conference on sustainable development, uncsd, earth summit 2012, sustainable development group, unsdg, undg, human development index, hdi, development cooperation forum, dcf, sustainable development group, development group, international fund for agricultural development, idaf, millennium summit, millennium declaration, millennium development goals, mdg, sustainable development goals, sdgs, agenda 2030, world summit, *educational, scientific and cultural organization, unesco, statistical commission, unsd, statistics division, undata, unu, research institute for social development, unrisd, interregional crime and justice research institute, unicri, human settlement program, habitat assembly, *tax committee, international civil service commission, icsc, department of public information, dpi, united nations universal periodic review, un universal periodic review, universal periodic review, upr, ocha, humanitarian air service, peacekeeping forces, appeals tribunal, unat, international law commission, law commission, ilc, trusteeship council, intergovernmental committee of experts on sustainable development financing, intergovernmental committee, economic commission for latin america and the caribbean, uneclac, eclac, office at geneva, unog, international criminal court, icc, icct, international criminal tribunal, ictr, icty, disarmament commission, undc, youth assembly, office on drugs and crime, unodc, environment programme, unep, international civil aviation organization, icao, intergovernmental panel on climate change, ipcc, convention on the rights of persons with disabilities, crpd, united nations convention on the rights of the child, uncrc, crc, united nations framework convention on climate change, unfccc, geneva convention, universal declaration of human rights, charter of the united nations, #charter, international convention on the elimination of all forms of racial discrimination, resolution 1325, standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners, smrs

Figure A1. Average sentiment over time for feminist NGOs.

Figure A2. Average sentiment over time for conservative NGOs.

ID: 183. ARROW (1 August 2017). ‘Taking stock of gains and losses – thoughts from the 2017 high-level political forum (HLPF)’. Retrieved from https://arrow.org.my/taking-stock-gains-losses-thoughts-2017-high-level-political-forum-hlpf/

ID: 333. ARROW (24 June 2015). ‘Sachini of ARROW at the 6th IGN at the United Nations’. Retrieved from https://arrow.org.my/arrow-sachini-ign-june/

ID: 357. ARROW (22 September 2014). ‘Siva of ARROW at the Special Session of the UN General Assembly on ICPD Beyond 2014’. Retrieved from https://arrow.org.my/arrow-siva-ungass-icpd-special-event/

ID: 451. AWID (15 December 2020). ‘Where is the money for feminist organising? New analysis finds that the answer is alarming’. Retrieved from https://www.awid.org//news-and-analysis/where-money-feminist-organising-new-analysis-finds-answer-alarming

ID: 459. AWID (14 October 2020). ‘We demand greater transparency and accountability from the Human Rights Council’. Retrieved from https://www.awid.org//news-and-analysis/we-demand-greater-transparency-and-accountability-human-rights-council

ID: 564. AWID (18 September 2017). ‘Raising women’s voices: Recommendations for the European Commission & United Nations’. Retrieved from https://www.awid.org//news-and-analysis/raising-womens-voices-recommendations-european-commission-united-nations

ID: 814. AWID (19 April 2015). ‘Challenging the power of the one percent’. Retrieved from https://www.awid.org//news-and-analysis/challenging-power-one-percent

ID: 823. AWID (20 March 2015). ‘CSW 59 – Beijing betrayed’. Retrieved from https://www.awid.org//news-and-analysis/csw-59-beijing-betrayed

ID: 851. AWID (3 October 2014). ‘Conflict, poverty and climate change remain challenges to achieving the MDGs In Ivory Coast, should be priorities post 2015’. Retrieved from https://www.awid.org//news-and-analysis/conflict-poverty-and-climate-change-remain-challenges-achieving-mdgs-ivory-coast

ID: 1139. AWID (15 June 2021). ‘Time for action: Stop the anti-rights infiltration of the UN!’. Retrieved from https://www.awid.org//publications/time-action-stop-anti-rights-infiltration-un

ID: 1418. CARE (13 November 2021). ‘No breakthrough in Glasgow: Developed countries do not take responsibility for damage done’. Retrieved from https://www.care-international.org/news/press-releases/no-breakthrough-in-glasgow-developed-countries-do-not-take-responsibility-for-damage-done-1

ID: 1492. CARE (3 March 2021). ‘CARE report reveals UN and wealthy nations’ lack of funding for women in emergencies’. Retrieved from https://www.care-international.org/news/press-releases/care-report-reveals-un-and-wealthy-nations-lack-of-funding-for-women-in-emergencies

ID: 1556. CARE (12 July 2020). ‘UN Security Council to further restrict humanitarian access to northwest Syria’. Retrieved from https://www.care-international.org/news/press-releases/un-security-council-to-further-restrict-humanitarian-access-to-northwest-syria

ID: 2000. CARE (11 March 2015). ‘JAPAN UN world conference on disaster risk reduction’. Retrieved from https://www.care-international.org/news/press-releases/japan-un-world-conference-on-disaster-risk-reduction.

ID: 3576. DAWN (12 March 2015). ‘CSW59 news release: Women’s voices shut out of UN political declaration on women’s rights’. Retrieved from https://dawnnet.org/2015/03/csw59-news-release-womens-voices-shut-out-of-un-political-declaration-on-womens-rights/

ID: 4190. ISHR (7 October 2021). ‘UNmute civil society say 61 states at the UN Third Committee’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/unmute-civil-society-say-61-states-at-the-un-third-committee/

ID: 4388. ISHR (5 October 2020). ‘Déjà vu all over again at the Human Rights Council’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/deja-vu-all-over-again-human-rights-council/

ID: 4454. ISHR (3 May 2020). ‘Reprisals | UN and States can and must do more to prevent and address reprisals’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/reprisals-un-and-states-can-and-must-do-more-prevent-and-address-reprisals-0/

ID: 4986. ISHR (5 September 2017). ‘Make no mistake | The dos and don’ts of treaty body strengthening’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/make-no-mistake-dos-and-donts-treaty-body-strengthening/

ID: 5020. ISHR (12 June 2017). ‘HRC35 | UN experts on business and human rights to develop guidance on supporting defenders’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/hrc35-un-experts-business-and-human-rights-develop-guidance-supporting-defenders/

ID: 5029. ISHR (29 May 2017). ‘LGBT rights | UN expert’s first report calls for global efforts to ensure universal application of human rights’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/lgbt-rights-un-experts-first-report-calls-global-efforts-ensure-universal-application-human/

ID: 5060. ISHR (27 March 2017). ‘HRC34 | Civil society presents key takeaways from Human Rights Council’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/hrc34-civil-society-presents-key-takeaways-human-rights-council/.

ID: 5093. ISHR (15 February 2017). ‘Corporate accountability | UN jurisprudence a key tool for protecting human rights defenders from business-related abuses’. Retrieved from https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/corporate-accountability-un-jurisprudence-key-tool-protecting-human-rights-defenders-business/

ID: 5815. Plan International (7 July 2017). ‘Better aid and solutions for refugees’. Retrieved from https://plan-international.org/blog/2017/07/better-aid-and-solutions-refugees

ID: 5866. Plan International (15 June 2015). ‘We cannot use old indicators to measure new ideas in SDGs’. Retrieved from https://plan-international.org/blog/2015/07/we-cannot-use-old-indicators-measure-new-ideas-sdgs

ID: 5910. Plan International (9 July 2014). ‘Education for all: Promises are not enough’. Retrieved from https://plan-international.org/blog/2015/05/education-all-promises-are-not-enough