The recent global surge in women attaining high-ranking political positions marks a significant shift in political landscapes (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 Notably, European nations such as Denmark, Germany, Finland, Iceland, Sweden, and Norway have embraced female leadership since 2000, culminating in every Nordic nation boasting a female prime minister by 2021. In Asia, despite stringent gender norms, female leaders like Yingluck Shinawatra in Thailand, Park Geun-hye in South Korea, and Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar have risen to prominence. Latin America has witnessed a similar evolution, with figures like Michelle Bachelet in Chile, Cristina Kirchner in Argentina, and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil leading the way. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was elected as Liberia’s first female president in Africa in 2005. Since then, countries such as Malawi, Senegal, Gabon, and Togo have also seen the rise of female executive leaders. This trend extends to female cabinet representation, with Michelle Bachelet forming the world’s first gender-balanced cabinet in 2006. By 2015, Finland, Iceland, Sweden, and Spain achieved equal gender representation in their cabinets, with Ethiopia and Rwanda leading Africa’s strides in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Women increasingly occupy traditionally male-dominated high-prestige portfolios like finance, defense, and foreign affairs.

Figure 1. Worldwide female executive leaders and cabinet members,1966-2021.

Source: Authors’ calculation, based on Archigos, WhoGov dataset, and self-collected data.

The rising prominence of female leaders in executive roles has piqued scholarly interest in their impact on the gender composition of cabinets (Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). This interest revolves around whether female leaders, often viewed as trailblazers breaking gender norms, actively advocate for increased female representation in government (Davis Reference Davis1997; Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014). Scholars argue that the ascendancy of women in power not only signals societal acceptance of women in authoritative roles (Alexander and Jalalzai Reference Alexander and Jalalzai2020), but also sets an expectation for these leaders to champion more inclusive cabinet appointments (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009). Studies suggest that female leaders often cultivate networks with other women, which could potentially influence cabinet appointments (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Kenny Reference Kenny2013; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016). However, the influence of female leaders on cabinet composition is nuanced. Some research indicates that factors like government form and legislative control might condition their impact (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009; Field Reference Field2021; Krook and O’Brien 2012). There is even a suggestion that some female leaders might adhere to existing male-dominated structures, “shutting the door” behind them and limiting female cabinet appointments (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015).

Despite this burgeoning interest, a critical gap in this area of study is the role of family ties in female leaders’ cabinet appointments. Considering the significant number of female leaders ascending through familial connections (Genovese and Steckenrider Reference Genovese and Steckenrider2013; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016; Jalalzai and Rincker Reference Jalalzai and Rincker2018), the absence of empirical research exploring the effect of these ties on cabinet composition is striking. Previous studies indicate that family ties can serve either as informal constraints (Derichs and Thompson Reference Derichs and Thompson2013; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013) or sources of political capital (Besley and Reynal-Querol Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2017; Folke et al. Reference Folke, Rickne and Smith2021), influencing cabinet choices.

This study addresses this gap by providing the first empirical analysis of how various family ties affect female leaders’ cabinet appointments. Using an original dataset encompassing information on family ties of chief executives from 160 countries between 1966 and 2021, we examine the effects of family ties, categorizing them as ties to former executive leaders, non-executive-leader political figures, or the absence of political family ties. We find that (1) female leaders tend to appoint more women to their cabinets and high-prestige positions within these cabinets; (2) leaders’ family ties exhibit a significant “Goldilocks (inverted-U) effect” on female representation in cabinets; and (3) there exists a significant nonlinear interaction effect between leaders’ gender and the nature of family ties – female leaders with moderate family ties – neither too deeply entrenched in political dynasties nor completely devoid of political lineage – are optimally positioned to advance women’s representation in cabinets. This study also explores why female leaders with non-executive-leader family ties are more inclined to appoint women, suggesting that their moderate political inheritance, higher educational achievements, and global exposure may drive this tendency.

This study contributes to the research on women in executive politics and political dynasties. By assembling a comprehensive and current dataset, we demonstrate a global trend where the rise of female leaders correlates with increased appointments of women to cabinet and high-prestige roles. We delve into the distinct “Goldilocks effect” of different types of familial ties on gendered cabinet appointments, offering new insights into the literature on hereditary rule. This aspect of our research also highlights the need to further examine the varied effects of various family ties. Our findings challenge the notion that women’s reliance on family ties for political ascension diminishes in the face of their growing political participation. By presenting the latest data, our study underscores the ongoing significance of family ties in shaping gendered leadership and executive politics.

Female Leaders: Catalyst or Barrier for Women in Cabinet Roles

The “girls help girls” hypothesis suggests that women in legislative and governmental roles often favor women-focused policies (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Osborn Reference Osborn2012). This study explores whether this trend extends to female leaders’ cabinet appointments. Though region- or regime-bounded, several cross-national studies have indicated that female leaders often facilitate the inclusion of women in cabinets (Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016, Reference Reyes-Housholder2019), including high-profile roles like defense and diplomacy (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Erlandsen et al. Reference Erlandsen, Hernández-Garza and Schulz2022).

Female leaders may prefer appointing women to cabinet roles due to greater familiarity with competent and loyal female colleagues, as they often engage more with other women during their political ascent (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Kenny Reference Kenny2013). They might also view female candidates as more aligned with their perspectives, influencing their appointment decisions (Dewan and Myatt Reference Dewan and Myatt2010; Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015). This is supported by findings that female local party leaders are likelier than males to recruit female candidates (Cheng and Tavits Reference Cheng and Tavits2011; Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013). Empirical evidence from Latin America shows female leaders are more likely to appoint women to cabinets, especially in systems where they have greater appointment autonomy (i.e., in a presidential system, Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016). Additionally, the presence of female leaders may inspire current female politicians to actively pursue higher offices, such as cabinet roles, effectively expanding the candidate pool. Historical biases in executive institutions have traditionally favored men, resulting in fewer female cabinet candidates and limited appointment opportunities (O’Brien and Reyes-Housholder Reference O’Brien, Reyes-Housholder and Andeweg2020; Sjoberg Reference Sjoberg, ‘t Hart and Rhodes2014). As role models, however, female leaders can immediately spark political ambitions among existing female politicians and gradually enhance the pipeline of women entering politics (Atkeson Reference Atkeson2003; Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Ladam et al. Reference Ladam, Harden and Windett2018), ultimately increasing female representation in the cabinet.

Furthermore, the emergence of female leaders has the potential to challenge male-dominated portfolios and traditional gender norms, thereby fostering acceptance, if not demand among voters and elites, for more women in cabinet roles. Long-standing all-male governments often reflect entrenched gender norms that confine women to the private sphere and restrict their entry into traditionally masculine roles such as defense, economic affairs, and budgeting (Davis Reference Davis1997; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009). However, the ascent of female leaders disrupts these norms, increasing acceptance of female representation in high-prestige governmental positions (Alexander and Jalalzai Reference Alexander and Jalalzai2020; Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014). Their presence normalizes women in leadership, enhances perceptions of women’s capabilities, and underscores their suitability for prominent positions (Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013), thus opening opportunities for roles traditionally dominated by men, such as ministers of defense and ambassadors (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Erlandsen et al. Reference Erlandsen, Hernández-Garza and Schulz2022). Literature on symbolic representation supports that the visibility of female leaders increases public acceptance of women in power (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006), progressively altering societal norms and perceptions about women in prominent political roles (O’Brien and Rickne Reference O’Brien and Rickne2016). Additionally, female leaders might demonstrate confidence and assertiveness—qualities traditionally coded as masculine—by promoting other women to top posts, thereby challenging gender norms and showcasing their leadership strength (Dolan Reference Dolan2005; Kanter Reference Kanter1977).Footnote 2

On the contrary, some studies suggest that female leaders may not necessarily appoint more women to their cabinets, particularly in high-prestige positions, and may even act as barriers to such appointments. Political leaders are often perceived as embodying masculine traits like decisiveness, toughness, and forcefulness (Alexander and Andersen Reference Alexander and Andersen1993; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Lawless Reference Lawless2004; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014; Sjoberg Reference Sjoberg, ‘t Hart and Rhodes2014), which can influence female leaders to conform to these stereotypes, creating inadvertent barriers for women in cabinet roles (Shvedova Reference Shvedova, Ballington and Karam2002; Sykes Reference Sykes, ‘t Hart and Rhodes2014). For instance, female defense ministers may increase military spending or engage more in international conflicts to mirror aggressiveness (Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011), and female foreign ministers might reduce foreign aid to showcase toughness (Lu and Breuning Reference Lu and Breuning2014). These actions suggest that some female leaders may deliberately exclude potential female cabinet members to authenticate their adherence to masculine leadership traits (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013; Michelle Heath et al. Reference Michelle Heath, Schwindt‐Bayer and Taylor‐Robinson2005), reinforcing their leadership suitability (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018). Particularly in high-profile roles, where appointments are heavily scrutinized and potentially face significant resistance from political elites or the public, female leaders may employ different considerations than in general cabinet appointments (Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Clayton and Zetterberg Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar‐Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson2005). This heightened scrutiny and the political sensitivity of these positions could influence a female leader’s decision-making process, leading to more conservative choices in cabinet appointments (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2016).

Furthermore, the potential costs of promoting women to cabinet positions might exceed the benefits, discouraging female leaders from appointing females to cabinet or top posts. Female leaders who prioritize gender representation might not receive commendation for their efforts; instead, they may face reproach for favoritism and promoting “identity politics,” perceived as prioritizing gender parity over the quality of the politicians (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). Moreover, female leaders may find themselves under pressure to mollify male colleagues to safeguard cabinet solidarity, particularly in parliamentary and semi-presidential democracies, where female leaders tend to have shorter tenures and are more likely to lose office following a decrease in their party’s vote share (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). Additionally, the role of female leaders as symbolic representations or tokens may create an illusion of fulfilled demands for equal representation (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2016; Kanter Reference Kanter1977). This can, in turn, exempt parties from the perceived obligation to nominate additional female cabinet members. When a woman occupies a pivotal political position, it becomes increasingly challenging for women to contend that they are systematically excluded from government roles. The presence of a female leader could paradoxically raise the entry bar for women seeking cabinet positions and traditionally prestigious posts.

Although both propositions have merit under specific conditions, existing research is often constrained by its geographical focus and temporal range. Prior studies have predominantly concentrated on specific regions such as Latin America (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016) and Europe (Davis Reference Davis1997), or on well-established democracies (Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015), with limited temporal coverage (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). This comprehensive analysis, however, spans 160 countries from 1966 to 2021, allowing us to conduct a global evaluation of the impact of female leadership on women’s inclusion in cabinets. This broad scope enables a thorough examination of the competing propositions: whether female leaders act as catalysts or barriers to appointing more women to cabinet positions. We begin by proposing a set of “catalyst” hypotheses as follows while remaining open to potential “barrier” findings:

H1a: Female leaders are more likely to appoint more women to their cabinets than their male counterparts.

H1b: Female leaders are more likely to appoint more women to high-prestige portfolios than their male counterparts.

Family Ties: Informal Constraints or Political Capital?

The debate over female leaders’ inclination toward fostering gender parity in cabinets hinges not merely on their gender, but rather on the incentives and discretion available to promote women. Feminist institutionalists argue that gendered institutions, including both formal and informal structures like party ideology, government systems, legislative control, and the prioritization of women’s equality, play a pivotal role in either facilitating or hindering their ability to appoint women to cabinet roles. For instance, in coalition governments, the limited number of ministerial positions per party may constrain female leaders’ ability to increase female representation in their cabinets (Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). Furthermore, the critical mass theory posits that a significant minority, or “critical mass,” of legislators is required for women to influence legislation effectively (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2006). Given the male-dominated composition of many legislatures, female leaders in countries with high legislative control might face limitations in nominating their preferred female candidates. Additionally, party ideology emerges as a crucial determinant, with evidence suggesting that female leaders from leftist parties tend to appoint more women (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015).

Although formal institutional factors indeed matter, it is notable that a significant portion of women leaders have historically leveraged their family’s political legacy as an informal institution to ascend to power (Genovese and Steckenrider Reference Genovese and Steckenrider2013; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016; Jalalzai and Rincker Reference Jalalzai and Rincker2018). Before 1995, 42% of women stepping into executive roles had politically significant husbands or fathers, with every female executive in Asia having a father or husband previously in office (Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Hughes and Barnes2021). Our data from 1996 to 2021 indicates that 24.29% of female leaders had dynastic ties, and 32.86% had non-executive ties. From 2000 to 2021, the proportion of female leaders with dynastic ties decreased to 21.15%, whereas those with non-executive ties increased to 34.62%. Male leaders from 1996 to 2021 had lower percentages of family ties, with 10.16% having dynastic ties and 15.53% non-executive ties. However, there was a noticeable increase in family ties among male leaders from 2000 to 2021, with dynastic ties rising to 11.15% and non-executive ties to 18.71%. These trends suggest family ties influence political leadership and their cabinet choices. Although the impact of hereditary rule on economic growth, democracy, and quality of governance has been explored (Besley Reference Besley2006; Besley and Reynal-Querol Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2017; Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007; Geys and Smith Reference Geys and Smith2017; Smith Reference Smith2018), its specific effect on cabinet gender composition is underresearched. Notably, hereditary rulers are typically seen as those with direct succession (Dal Bó et al. Reference Dal Bó, Bó and Snyder2009), but family ties in politics are multifaceted, with “hereditary (or dynastic)” being just one aspect.

In the present study, we categorize chief executive leaders based on their family ties into three groups: relatives of previous executive leaders (dynastic); relatives of non-executive-leader political figures, such as central and local government officials, military/police officials of at least second lieutenant rank, central and local legislative representatives, central and local judges/prosecutors, party leaders, religious leaders, and tribal leaders; and leaders without family ties. Dynastic family ties are especially noted for their role in elite power dynamics. Literature suggests that outgoing leaders might use personnel appointments to maintain influence post-tenure by placing allies in strategic positions (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Xi and Xie2024; Southall Reference Southall, Southall and Melber2006). Such practices are prominent in familial successions, with successors expected to perpetuate their family’s political legacy (Derichs and Thompson Reference Derichs and Thompson2013; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013), leading to stability in ally appointments. The historical male dominance in executive roles means that appointing more women could signify a break from tradition, potentially less frequent under dynastic leadership. Conversely, leaders with non-executive ties might experience fewer restrictions in their appointments, not bound by the same expectations to preserve legacy power structures.

Contrary to the perspectives that view family ties as constraints, other literature suggests these ties can serve as crucial political capital, enhancing a leader’s capacity to appoint more women to cabinets. This capability is supported by studies indicating that the reputation of a prominent political family can regulate a leader’s behavior, reduce moral hazard, and ensure good governance in the eyes of voters (Besley and Reynal-Querol Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2017; Myerson Reference Myerson2015). Family connections also function as quality signals to voters, effectively communicating a politician’s credibility and overcoming information asymmetries about their capabilities (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Rickne and Smith2021). Family connections, seen as significant symbolic capital (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986; Bourdieu et al. Reference Bourdieu, Wacquant and Farage1994), can transform into political capital, distinguishing these leaders from others during campaigns and increasing their chances of success (Spark et al. Reference Spark, Cox and Corbett2019). Politicians with family ties can more readily gain public trust and support. Extended tenure of family members in office can nurture political ambitions in successors and facilitate sharing networks or resources, cementing their political status (Dal Bó et al. Reference Dal Bó, Bó and Snyder2009; Smith Reference Smith2018; Querubin Reference Querubin2016). Since leaders tend to be conservative in policymaking and appointments when feeling insecure about support or power status (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015), they may be reluctant to challenge potential adversaries (Dowding and Dumont Reference Dowding and Dumont2007) or change the male-dominated cabinet status quo. Leaders backed by a family reputation and public trust may display greater confidence and risk tolerance in making unconventional appointments, such as increasing female representation in cabinets (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2016).

Integrating insights that view family ties as both informal constraints and political capital, we posit that the nature of a leader’s family ties, irrespective of gender, exerts a consequential Goldilocks (inverted-U) effect on the representation of women in cabinets (Fig. 2). The Goldilocks effect posits that leaders with a moderate level of familial political ties – neither too deeply entrenched in political dynasties nor entirely devoid of such connections – are optimally positioned to enhance female representation in cabinets. Specifically, at one end of the spectrum, leaders from political dynasties, despite with political capital, encounter informal institutions that constrain their autonomy in cabinet appointment due to the weight of legacy and expectations (Besley and Reynal-Querol Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2011). On the other end, leaders without familial political ties often lack the necessary institutional support and networks for effective political maneuvering (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013; Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995). In contrast, leaders with moderate family ties benefit from enough political capital to influence appointments but are not restricted by the burdensome legacy of dynastic ties or completely shielded from external pressures for cabinet diversity. This balance is key to exercising political autonomy and meeting societal and political demands for inclusivity, like appointing more women to cabinets and high-prestige roles, without encountering the severe backlash or resistance that might constrain those with dynastic ties or those entirely outside the political lineage. Hence, leaders with the “just right amount” of political inheritance are most inclined to appoint more women to their cabinets and high-prestige portfolios:

H2a: Leaders with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures are most inclined to appoint more women to their cabinets, whereas dynastic leaders and leaders without familial connections are less prone to do so.

H2b: Leaders with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures are most inclined to appoint more women to high-prestige portfolios, whereas dynastic leaders and leaders without familial connections are less prone to do so.

Figure 2. Illustration of the “Goldilocks (inverted-U) effect” of family ties.

In executive politics, family ties emerge as a critical factor in shaping the pathways and decisions of leaders, particularly for female executives. Women, often possessing qualifications on par with or superior to their male counterparts, face unique barriers in the political landscape, including challenges in networking, fundraising, and overcoming gender biases. These obstacles are particularly pronounced for women without a political lineage, highlighting the significance of familial connections in facilitating access to political power (Conway Reference Conway2001; Phelps Reference Phelps2004). Political dynasties have historically been a common avenue for women to gain access to high-level political roles, with dynastic female leaders benefiting from the resources and networks established by their families (Baturo and Gray Reference Baturo and Gray2018). However, this dynastic advantage can also create a sense of obligation to uphold family legacies, potentially leading these leaders to maintain the status quo rather than promoting further female representation in cabinets.

Intriguingly, family ties often bestow greater advantages on women than men in the political arena, mitigating the perceived uncertainties and informational disadvantages women face in the eyes of political parties and voters. Research indicates a pervasive trend of uncertainty surrounding female candidates, even in contexts where they match or exceed the qualifications of their male counterparts. In the United States, central and local political elites exhibit more skepticism about female candidates than males (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2006). This trend extends to Canada, where female candidates with equivalent qualifications often receive fewer votes than their male counterparts (Black and Erickson Reference Black and Erickson2003). Similarly, in Sweden, party recruiters express heightened reservations about nominating women, particularly those with familial responsibilities (Widenstjerna Reference Widenstjerna2019). Therefore, the reputation associated with a political family becomes a pivotal asset for female leaders, offering a quality signal that can secure broader support and enable substantive changes in governmental gender composition. This dynamic places female leaders with moderate family ties in a position, allowing them to leverage their family connections for credibility and influence while maintaining enough autonomy to advance progressive gender policies within political institutions. Given these insights, the present study proposes a notable nonlinear interaction between a leader’s gender and their familial ties (Fig. 3):

H3a: Female leaders with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures are most inclined to appoint more women to their cabinets, whereas dynastic female leaders and female leaders without family ties are less inclined to do so.

H3b: Female leaders with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures are most inclined to appoint more women to high-prestige portfolios, whereas dynastic female leaders and female leaders without family ties are less inclined to do so.

Figure 3. Illustration of the nonlinear interaction effect between leaders’ sex and their kinship.

Empirics

Data and Variables

To test our three sets of hypotheses, we constructed a novel dataset of 8142 country-year observations nested in 160 countries worldwide from 1966 to 2021. Our independent variables are the gender of chief executive leaders, and their family ties to different political figures. Partial information on leaders’ names, genders, and family ties was obtained from the latest Archigos database, a dataset of political leaders (Goemans et al. Reference Goemans, Gleditsch and Chiozza2009).Footnote 3 Archigos identifies the “actual effective rulers” in each country,Footnote 4 aligning with our research purpose as only these leaders wield the decisive power to appoint cabinet members. The Archigos dataset only covers the period from 1875 to 2015 and only codes one type of family ties — whether a leader has any relationship with previous top leaders. We extended the data coverage to 2021 and gathered information on other types of family ties, including relationships to non-executive-leader political figures from various resources such as the Encyclopedia of Heads of States and Governments, Oxford Political Biography: Who is Who in the Twentieth Century World Politics, Encyclopedia Britannica, and other online sources, including Wikipedia.

In addition to dynastic family ties, we identified 10 types of non-executive-leader family ties, namely family ties to central government officials, local government officials, military/police officials of at least second lieutenant rank, representatives in central legislative bodies, representatives in local councils, judge/prosecutor in central courts, judge/prosecutor in local courts, party leaders, religious leaders, and tribal leaders.Footnote 5 In conjunction with family ties to former executive leaders, we identified and categorized 11 types of family ties. Our categorization of leaders’ family ties to people in different political positions is consistent with Besley and Reynal-Querol (Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2017). Still, it is more comprehensive and fine-grained to cover a broader range of family ties. To ensure precision, we include only familial ties within the same country and up to four generations back, and only those established before the leader’s ascent to power, thus mitigating the risk for reverse causality. Each family tie category is initially coded as count variables to tally the number of a leader’s relatives in a specified political position and then recoded as binary variables that signify whether a leader has at least one relative in a specified political position. Correlations among the 11 types of family ties show no significant interconnection (Appendix IV, Table 2). From these, we derived an ordinal variable, “position,” with a value of 3 for leaders with ties to former executive leaders, 2 for leaders connected to at least one non-executive-leader political figure across the 10 identified roles but not connected to former executives, and 1 for leaders without any familial connections.

Our primary dependent variables, “percentage of female cabinet members” and “percentage of female high-prestige cabinet members,” were derived from the WhoGov dataset (Nyrup and Bramwell Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020).Footnote 6 This dataset provides country-year data on the total numbers of female cabinet members and those holding high-prestige portfolios, alongside the total numbers of all cabinet members and core cabinet members with high-prestige portfolios. Consequently, the percentage of female cabinet members was calculated by dividing the total number of female cabinet members by the total number of all cabinet members. Similarly, the percentage of female high-prestige cabinet members was calculated by dividing the total number of female high-prestige portfolios by the total number of core cabinet members.

Our models incorporate a suite of control variables that could potentially influence the presence of female cabinet members, ensuring unbiased estimations, and that may affect the presence of female executive leaders, partially addressing endogeneity concerns. An increased number of female legislators could shift both the supply and demand dynamics for female leaders and cabinet members (Bego Reference Bego2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson 2005; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). We sourced the “women in the legislature” data from the IPU dataset.Footnote 7 We also control for the number of parties in government, reflecting the increased likelihood of female leadership in coalition environments (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). Moreover, the ruling party’s ideology might sway the appointment of women to the cabinet, with left-leaning governments frequently showcasing more female cabinet members (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015; Bego Reference Bego2014). We gathered information on party ideology from the V-Dem Party-V2 dataset.Footnote 8

Previous literature suggests higher quality democracies foster women’s political empowerment (Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Alexander and Jalalzai Reference Alexander and Jalalzai2020; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2016; Neundorf and Shorrocks Reference Neundorf and Shorrocks2022). Hence, we control for democracy levels using Polity IV.Footnote 9 Beyond the realm of democracy, research indicates that institutional factors significantly influence women’s appointment to cabinets and high-prestige portfolios. For instance, a presidential system may promote women’s cabinet ascension (Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016), whereas military dictatorships may hinder women from securing high-prestige portfolios (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018). We incorporate controls for these two political system types to address these factors, sourcing the relevant data from the WhoGov dataset.Footnote 10

A strong anti-corruption stance is deemed crucial for female politicians’ rise to power, as women are often perceived as less corruptible (Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Barnes, O’Brien and Taylor-Robinson2022; Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014). Consequently, heightened political corruption may amplify the demand for female government officials within a nation (Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014; Thompson and Lennartz Reference Thompson and Lennartz2006). We procured the “Political Corruption Index” from the V-Dem dataset (v2x_corr) (McMann et al. Reference McMann, Pemstein, Seim, Teorell and Lindberg2016).Footnote 11 Moreover, numerous studies propose that “modernization” amplifies women’s access to politics. Widely accepted modernization indicators include the proportion of women with tertiary education (Bego Reference Bego2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson 2005; Neundorf and Shorrocks Reference Neundorf and Shorrocks2022), female labor force participation rate (Bego Reference Bego2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor‐Robinson 2005; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2008), gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, fertility rate, infant mortality rate, and life expectancy (Neundorf and Shorrocks Reference Neundorf and Shorrocks2022). We sourced data for these variables from the World Bank’s World Development IndicatorsFootnote 12 and Gender Statistics.Footnote 13 The pursuit of conflict resolution also catalyzes the emergence of female executive leaders, given their usual detachment from domestic fractions (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). We garnered data on civil wars, internal armed conflicts, and coups d’etat from the Armed Conflict Dataset (Harbom and Wallensteen Reference Harbom and Wallensteen2009) at the International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO)Footnote 14 and the Dyadic Inter-State War Dataset (Maoz et al. Reference Maoz, Johnson, Kaplan, Ogunkoya and Shreve2019) at the Correlates of War Project.Footnote 15 Women’s ascension to power can also be facilitated by social movements (Adams and Thomas Reference Adams, Thomas and Marlin-Bennett2018; Ferree and Tripp Reference Ferree and Tripp2006). We used the “Women Civil Society Participation Index” from the V-Dem dataset 16 (v2x_gencs) as a proxy. All control variables were lagged by 1 year to mitigate reverse causality in the analyses, and a continuous variable (t) was included to capture time trends. Regarding missing data, female enrollment rate in tertiary education and female labor force participation rate are the only two variables with a relatively large proportion of missing values (10.98% and 12.26%, respectively), for which we impute with mean values.Footnote 16 Table 1 in Appendix III summarize the descriptive statistics of independent variables, dependent variables, and control variables.

Estimation

Our empirical analysis first concentrates on the potential influence of female executive leaders on women’s ascent to cabinets and high-prestige portfolios. We employed time-fixed effects to control for time’s influence and country-fixed effects to account for the unobserved variables that might impact the results, considering the varied sociopolitical contexts across countries.Footnote 17 Our hypotheses H1a and H1b are tested based on the following equations:

where

![]() $ per\_{FEcabinet}_{i,t} $

and

$ per\_{FEcabinet}_{i,t} $

and

![]() $ per\_{FEhighportfolio}_{i,t} $

refers to the percentage of women in the cabinet and women in high-prestige portfolios in each country-year observation.

$ per\_{FEhighportfolio}_{i,t} $

refers to the percentage of women in the cabinet and women in high-prestige portfolios in each country-year observation.

![]() $ {gender}_{i,t} $

refers to the gender (0 if the leader is male and 1 if female) of chief executive leaders in each country-year observation.

$ {gender}_{i,t} $

refers to the gender (0 if the leader is male and 1 if female) of chief executive leaders in each country-year observation.

![]() $ {control\ variables}_{i,t} $

refers to the control variables listed in the “Data and Variables” section.

$ {control\ variables}_{i,t} $

refers to the control variables listed in the “Data and Variables” section.

![]() $ t $

refers to the trend over time.

$ t $

refers to the trend over time.

![]() $ ID $

and

$ ID $

and

![]() $ year $

are both dummy variables indicating the country and year-fixed effects. We use panel-correlated standard error (PCSE) in part to address groupwise heteroskedasticity and contemporaneous correlation issues in long panels.Footnote

18

$ year $

are both dummy variables indicating the country and year-fixed effects. We use panel-correlated standard error (PCSE) in part to address groupwise heteroskedasticity and contemporaneous correlation issues in long panels.Footnote

18

We also strive to demonstrate that executive leaders with familial connections to non-executive-leader political figures will most likely appoint more women to their cabinets and high-prestige portfolios. We proposed a Goldilocks effect; that is, leaders with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures and leaders without family ties may experience fewer informal constraints in personnel appointments compared to dynastic leaders. Conversely, compared with leaders without family ties, such familial connections may serve as political capital to support both dynastic leaders and those with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures in appointing women to cabinets. We created a new ordinal variable, “position,” based on 11 types of family ties to facilitate our research. Our hypotheses H2a and H2b are tested based on the following equations:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}per\_{FEcabinet}_{i,t}={\alpha}_1{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_1{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_1position\times {position}_{i,t}+{\sigma}_1{total}_{i,t}+\\ {}{\beta}_1{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_1t+{\delta}_1ID+{\theta}_1year+\varepsilon; \end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}per\_{FEcabinet}_{i,t}={\alpha}_1{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_1{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_1position\times {position}_{i,t}+{\sigma}_1{total}_{i,t}+\\ {}{\beta}_1{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_1t+{\delta}_1ID+{\theta}_1year+\varepsilon; \end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}per\_{FEhighportfolio}_{i,t}={\alpha}_2{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_2{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_2position\times {position}_{i,t}+\\ {}{\sigma}_2{total}_{i,t}+{\beta}_2{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_2t+{\delta}_2ID+{\theta}_2year+\varepsilon .\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}per\_{FEhighportfolio}_{i,t}={\alpha}_2{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_2{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_2position\times {position}_{i,t}+\\ {}{\sigma}_2{total}_{i,t}+{\beta}_2{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_2t+{\delta}_2ID+{\theta}_2year+\varepsilon .\end{array}} $$

In these equations, we also control the number of family ties a leader has (

![]() $ {total}_{i,t} $

).

$ {total}_{i,t} $

).

![]() $ position\times {position}_{i,t} $

indicates the possible Goldilocks effect of leaders’ family ties on the gender composition of cabinets. Then, to examine the possible nonlinear interaction effect between leaders’ gender and leaders’ family ties, our hypotheses H3a and H3b are tested based on the following equations:

$ position\times {position}_{i,t} $

indicates the possible Goldilocks effect of leaders’ family ties on the gender composition of cabinets. Then, to examine the possible nonlinear interaction effect between leaders’ gender and leaders’ family ties, our hypotheses H3a and H3b are tested based on the following equations:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c} per\_{FEcabinet}_{i,t}={\alpha}_1{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_1{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_1 position\times {position}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\tau}_1 gender\times {position}_{i,t}+{\varphi}_1 gender\times position\times {position}_{i,t}+{\sigma}_1{total}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\beta}_1{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_1t+{\delta}_1 ID+{\theta}_1 year+\varepsilon; \end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c} per\_{FEcabinet}_{i,t}={\alpha}_1{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_1{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_1 position\times {position}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\tau}_1 gender\times {position}_{i,t}+{\varphi}_1 gender\times position\times {position}_{i,t}+{\sigma}_1{total}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\beta}_1{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_1t+{\delta}_1 ID+{\theta}_1 year+\varepsilon; \end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}per\_{FEhighportfolio}_{i,t}={\alpha}_2{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_2{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_2position\times {position}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\tau}_2gender\times {position}_{i,t}+{\varphi}_2gender\times position\times {position}_{i,t}+{\sigma}_2{total}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\beta}_2{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_2t+{\delta}_2ID+{\theta}_2year+\varepsilon .\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}per\_{FEhighportfolio}_{i,t}={\alpha}_2{gender}_{i,t}+{\mu}_2{position}_{i,t}+{\rho}_2position\times {position}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\tau}_2gender\times {position}_{i,t}+{\varphi}_2gender\times position\times {position}_{i,t}+{\sigma}_2{total}_{i,t}\\ {}+{\beta}_2{control\ variables}_{i,t}+{\gamma}_2t+{\delta}_2ID+{\theta}_2year+\varepsilon .\end{array}} $$

where

![]() $ gender\times {position}_{i,t} $

stands for the linear interaction between leaders’ gender and leaders’ family ties.

$ gender\times {position}_{i,t} $

stands for the linear interaction between leaders’ gender and leaders’ family ties.

![]() $ gender\times position\times {position}_{i,t} $

represents the nonlinear interaction between leaders’ gender and the Goldilocks effect of family ties.

$ gender\times position\times {position}_{i,t} $

represents the nonlinear interaction between leaders’ gender and the Goldilocks effect of family ties.

Results

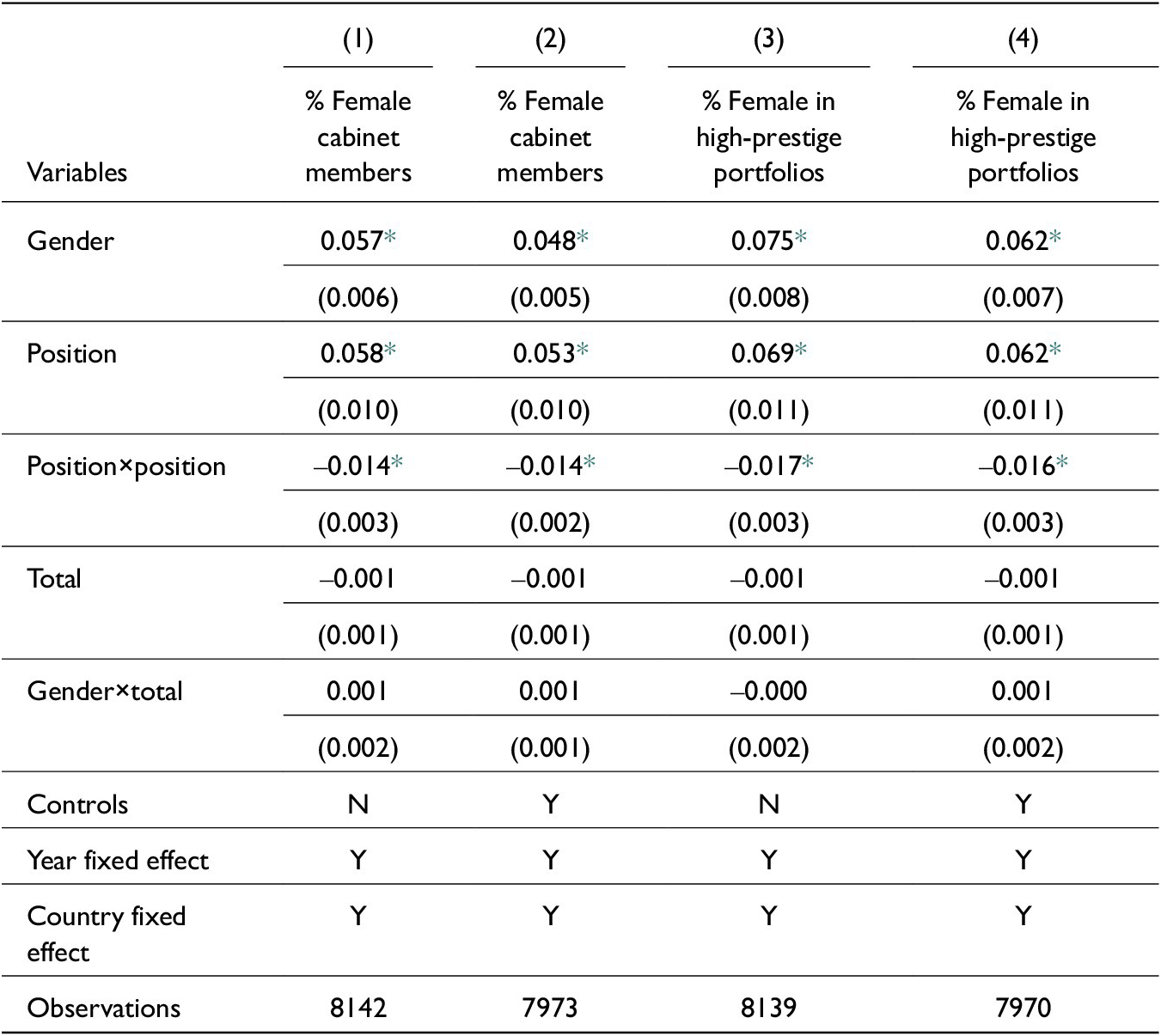

Table 1 presents the outcomes of our empirical scrutiny on the first series of hypotheses. On a global scale, our findings suggest that the rise of female leadership generally contributes significantly to the advancement of women in cabinet positions and high-prestige portfolios. This correlation remains robust even after considering control variables, whose influence does not alter the direction or significance of the independent variable.

Table 1. Female executive leaders, women’s ascension to cabinets and high-prestige portfolios

Note: Regression results are based on panel-correlated standard error model. Standard errors in parentheses.

* p <.001.

Table 2 delineates the correlation between leaders’ family ties and the allocation of portfolios to women. When family ties are included in equations, leaders’ gender is still positively associated with percentages of female cabinet members and high-prestige portfolios. Supporting our second set of hypotheses, the significant, negative coefficients of “position×position” in Table 2 confirm that leaders’ family ties exercise a Goldilocks effect on the representation of women in cabinets. Chief executive leaders with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures (coded as 2) are inclined to appoint more women to cabinets and high-prestige portfolios. Conversely, leaders with family members who have served as previous executive leaders (coded as 3), or those without family ties (coded as 1), are less likely to appoint women. As evidenced in these results, the total number of leaders’ familial connections does not significantly affect the representation of women in cabinets (p > .1), nor does it interact significantly with leaders’ gender (p > .1). This indicates that the quality of family ties, not the quantity, plays a pivotal role.

Table 2. Types of family ties, women’s ascension to cabinets and high-prestige portfolios

Note: Regression results are based on panel-correlated standard error model. Standard errors in parentheses.

* p<.001.

Moreover, further regression analyses on the subsample of male leaders show that this finding applies to them (Table 3). Male leaders can also face constraints or garner support from their familial connections when appointing more women to challenge the male-dominated political landscape. Altogether, these findings are consistent with our second set of hypotheses and the pattern depicted in Figure 2.

Table 3. The “Goldilocks effect” of family ties in male executive leaders

Note: Regression results are based on ordinary least squares model. Standard errors in parentheses.

* p <.001.

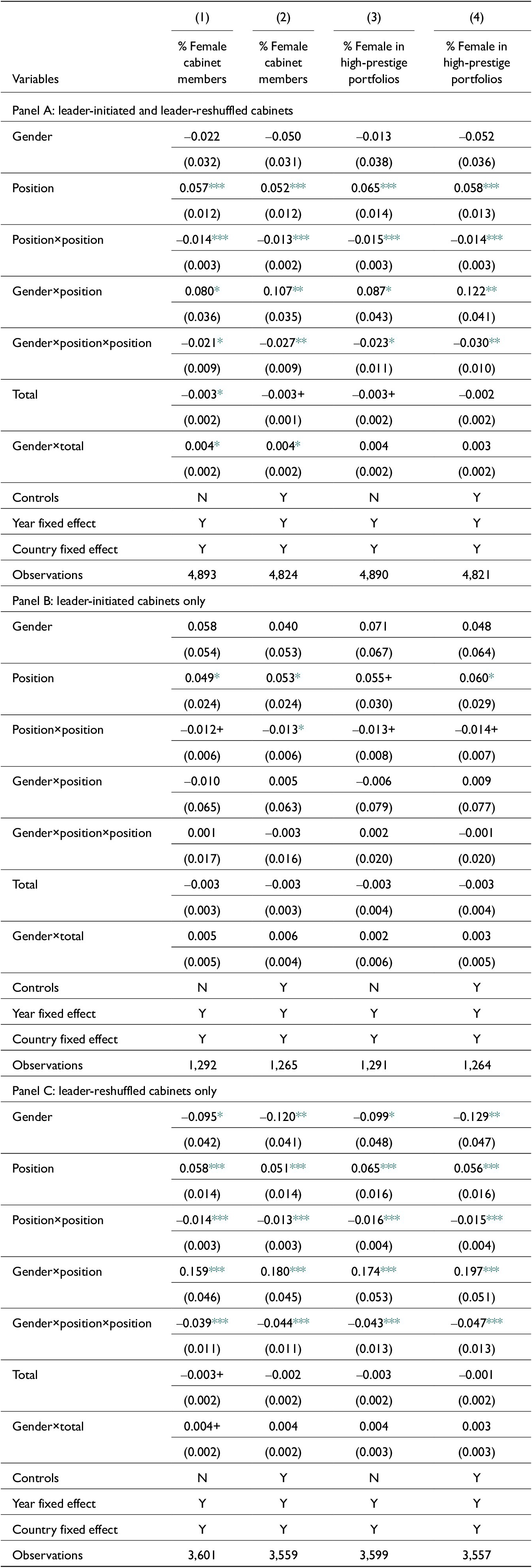

Table 4 assesses whether the Goldilocks effect of familial ties is especially noticeable in female leaders. Our findings support the third set of hypotheses, revealing a significant and negative nonlinear interaction effect between leaders’ gender and family ties. Specifically, the effect sizes of different types of family ties for female leaders (gender = 1 in models 2 and 4) are four times those for male leaders (gender = 0 in models 2 and 4), suggesting that female executive leaders may be more responsive to the influence of familial ties compared with their male counterparts. This aligns with our expectation that the Goldilocks effect of familial ties is more pronounced among female leaders, as evidenced by the steeper curve for female leaders than for all leaders. Further analysis reveals that female leaders with non-executive family ties see a 9.3% higher inclusion of women in cabinets than those with family ties to previous executive leaders, and a 0.5% increase over those without family ties (model 2 in Table 4). Likewise, female leaders with non-executive ties are associated with 11.2% more women in high-prestige portfolios than those with dynastic ties and a 0.2% increase than those without family ties (model 4 in Table 4). These results indicate that female leaders are most likely to appoint more women to cabinets and high-prestige portfolios when they inherit “just the right amount” of political legacies from their family members.

Table 4. Female executive leaders, family ties, women’s ascension to cabinets and high-prestige portfolios

Note: Regression results are based on panel-correlated standard error model. Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .1

** p < .05

*** p < .001.

Moreover, the influence of family ties is notably pronounced among female dynastic leaders, often restricting their ability to appoint more women to their cabinets than those without such ties. This effect becomes even more significant in high-prestige portfolio appointments, which aligns with our theoretical expectations. The marginal effect of non-executive-leader ties over dynastic ties is significantly larger (9.3% and 11.2%) than leaders without family ties (0.5% and 0.2%). Some factors may explain these subtle differences. Family ties to non-executive leaders may not enhance a leader’s political capital as much as dynastic ties, limiting their influence in decision making (Franceschet et al. Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013), or the burden of upholding a dynastic legacy and meeting patronage expectations (Besley and Reynal-Querol Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2011) may be too immense. Additionally, female leaders without family ties might compensate for this lack with personal achievements or party affiliations, affecting their ability to appoint more women to cabinets. The global trend of increasing women’s representation in politics (Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Hughes and Barnes2021) suggests a general baseline level of female appointments, which might diminish the relative impact of family ties.

Our initial use of a country-year data format in our empirical analyses may have inflated the observation count by including years without cabinet changes and lacking distinction between initial and reshuffled cabinets. To refine our analysis, we have switched to a country-cabinet data format, allowing for a more detailed examination of cabinet dynamics. This method helps determine whether our findings hold for leader-initiated and reshuffled cabinets. Notably, our analyses reveal that the observed gendered patterns in cabinet appointments are predominantly evident in reshuffled cabinets (Table 5, panel C), rather than initial ones. Additionally, in leader-initiated cabinets, the interaction effect between leaders’ gender and family ties proves insignificant (Table 5, panel B).

Table 5. Female executive leaders, family ties, women’s ascension to cabinets, and high-prestige portfolios in different cabinet types

Note: Regression results are based on ordinary least squares model. Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p <.001

** p <.01

* p <.05, + p <.1

Our research finds parallels in global female leadership dynamics, particularly in dynastic contexts. In Bangladesh, Khaleda Zia’s political ascent followed her husband’s assassination in 1982, rapidly rising to chair the Bangladesh Nationalist Party founded by him. Her swift promotion, unusual for a newcomer, indicates her role as a surrogate for her husband within the party. Her cabinets largely comprised her husband’s loyalists, maintaining a stable percentage of women compared to her predecessors. Sheikh Hasina, in contrast, had more political experience from an early age and was influenced by feminist Begum Rokeya during her time at Dhaka University’s Rokeya Hall. Despite these differences, both Zia and Hasina followed a similar path to power, succeeding in assassinating male family members and leading the parties they once headed. Consequently, their cabinets’ gender composition remained similar, adhering to political patronage norms. This pattern is echoed in Argentina with Isabel Peron and Cristina Kirchner, who followed in their husbands’ political footsteps. Isabel Peron, emblematic of “widows coming to power,” assumed the presidency following her husband’s death, inheriting his cabinet that perpetuated the existing gender composition. Cristina Kirchner, a formidable political figure in her own right and notably more prominent than her husband upon his presidential election in 2003, solidified her political influence in 2007, heavily reliant on her husband’s political network. As her husband vacated the presidency, he actively supported her candidacy within the Peronist party (Popper and Grazina Reference Popper and Grazina2011). In her tenure, Cristina preserved her husband’s political legacy by appointing his former subordinates to her cabinet, thus maintaining the gender balance established during his presidency. This included the notable appointment of her husband’s sister, which underscores the continuity of familial influence in her cabinet. Isabel and Cristina Kirchner’s experiences exemplify the nuanced role of dynastic familial ties in female presidential leadership in Argentina, particularly in how these ties influence cabinet composition and the perpetuation of gender norms within the highest echelons of political power.

In contrast to dynastic female leaders, those with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures tend to be more proactive in championing increased female representation in cabinet roles. A prominent example is Michelle Bachelet of Chile. Her father, Brigadier General Alberto Bachelet, held a distinguished position in the Chilean Air Force and was incarcerated for opposing Pinochet’s coup, later being hailed as a national hero. Inspired by her father’s legacy and aided by his political network, Michelle Bachelet made history as the first female Minister of Defense in Chile and Latin America during Ricardo Lagos’ presidency, who was a co-partisan and colleague of her father. Her ascent continued as she became Chile’s first female president, a victory underpinned by the trust and support of voters resonating with her father’s esteemed reputation. Bachelet’s tenure, marked by a popular mandate and bolstered by her influential network, was characterized by a steadfast commitment to enhancing women’s roles in the executive branch (Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2016). Skillfully maneuvering the political landscape with acumen inherited and developed beyond her family’s influence (Franceschet Reference Franceschet, Borzutzky and Weeks2010), Bachelet’s resolve culminated in establishing Chile’s inaugural gender-balanced cabinet during her first term as president. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia also shared a similar familial political legacy as her father was the first Indigenous Liberian elected to the national legislature. Sirleaf, influenced by her Americo-Liberian heritage and Western education, passionately championed the cause of gender equality. Her determination in this regard was so profound that she publicly expressed her aspiration to appoint an all-female cabinet. However, this was more of a symbolic declaration highlighting her commitment to women’s advancement (Koblanck 2005).Footnote 19 The leadership of Sirleaf and Bachelet, both of whom had non-executive family ties, is associated with increased female representation in cabinets.

The scenario becomes markedly more intricate for female leaders without any family ties. These leaders often aspire to increase female representation in cabinets, yet they confront numerous challenges that can dampen their aspirations. For example, Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff, who ascended to power without familial backing (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013), witnessed a rise in female cabinet representation in her initial cabinet, with 8 of 31 ministers being female. Although this percentage was low by regional standards, it was significantly higher than any of her predecessors. However, this representation decreased in her second year of presidency, falling to 4 of 25. Rousseff’s influence was largely confined to cabinet positions controlled by her party, and as Brazil faced economic challenges, she needed to form new political alliances to maintain her government (Dos Santos and Jalalzai Reference Dos Santos and Jalalazai2021). This situation illustrates that female leaders without familial political ties may be more vulnerable to uncertainties, thus potentially hesitating to appoint more women to the cabinet due to heightened political risks. For instance, Rousseff was compelled to incorporate more male politicians from other parties into her cabinets, likely as a compromise to secure coalition support. Had she had stronger family ties, preserving the initial higher proportion of women throughout her tenure might have been easier. This observation aligns with our empirical findings that differences in family ties significantly influence reshuffled cabinets more than initial ones. A similar complexity is evident in the tenure of New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. Ardern’s rise led to an increase in female cabinet appointments, but the extent of this increase was moderate, contradicting the expectations typically held for a youthful, Labor-party female leader. Several factors contributed to this outcome. Firstly, Ardern’s Labor Party finished second in the vote share, necessitating a tripartite coalition with a conservative center-right party not known for progressive feminist stances. Additionally, within the Labor Party, a gender divide existed in perceptions toward Ardern’s leadership. Male Labor voters were more likely to express discomfort and apprehension about her leadership, unlike female Labor voters who exhibited greater pride and optimism (Curtin and Greaves Reference Curtin, Greaves, Vowles and Curtin2020). This divergence necessitated a careful balancing act by Ardern, likely influencing her decision not to emphasize her gender identity in her political approach overly. Lacking the backing of established family ties, Ardern instead leveraged her youth as a political asset and adopted an inclusive populist rhetoric to enhance her appeal, especially among younger voters (Curtin and Greaves Reference Curtin, Greaves, Vowles and Curtin2020; Roughan Reference Roughan2017). This nuanced approach underlines the complex realities female leaders face without familial political support in their efforts to foster female representation in government.

Heterogeneity Analysis and Robustness Checks

We delve into the conditions that bound the applicability of our empirical findings. Considering the broad spectrum of heterogeneous units encapsulated in our analysis, it stands to reason whether our conclusions are universally applicable across diverse categories such as various regime types and temporal periods.

We explore the impact of family ties on women’s cabinet appointments across different regime types: democracies, anocracies, and autocracies. Our findings revealed that although the nonlinear interaction between leader gender and family ties holds in democracies and anocracies, it does not apply to autocracies (Appendix I, Table 1). We attribute this discrepancy in autocracies to the absence of competitive electoral processes, which diminishes the role of familial ties as signals of quality to selectorates. Interestingly, the prevalence of female leadership varies significantly across regimes: 8.11% in democracies, 1.28% in anocracies, and only 0.16% in autocracies. The scarcity of female leaders in autocratic contexts may challenge achieving statistically significant findings. Theoretically, the limited role of family ties in autocracies is consistent with observation and literature suggesting such ties may instead represent informal constraints imposed by predecessors or power consolidation tools within elite circles (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). In contrast, democracies and anocracies may interpret family ties as indicative of political competence or reliability, influencing both party selectorates and the electorate (Dal Bó et al. Reference Dal Bó, Bó and Snyder2009). The impact of family ties may be contingent on the political structures and processes of the regime in question. As a second measure, we adopted 1992 as the watershed marking the end of the Cold War, with many new nations surfacing after the Soviet Union’s collapse. Our results indicated the nonlinear interaction effect between leaders’ gender and family ties in the post-Cold War period (Appendix I, Table 2).

For the robustness assessment, we first changed the operationalization of our dependent and independent variables. We employed absolute numbers instead of percentages of women in cabinets and high-prestige portfolios for our dependent variables. Upon rerunning the analyses, our results remained stable (Appendix II, Table 1). We also excluded interim chief executive leaders with less than a full-year tenure, and no significant change was observed in our results (Appendix II, Table 2). We substituted the imputed data with nonimputed data, and our results persisted in their robustness (Appendix II, Table 3). Furthermore, we substituted our PCSE estimation models with baseline models leveraging ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation to demonstrate that our results were not model-dependent. Although OLS estimation might not be the most appropriate strategy compared with PCSE, our analyses upon repetition do not reflect any significant change in results (Appendix II, Table 4). Lastly, we introduced additional control variables to account for the potential influences of other variables. We first factored in a leader’s termFootnote 20 and tenure,Footnote 21 and their interactions with family ties as leaders’ influence may magnify with time in office, and family ties might experience a decay effect, and the results remained consistent (Appendix II, Table 5 and Table 6). We then accounted for the impact of ethnic fractionalization (Appendix II, Table 7), as there could be a correlation between ethnic representation and female representation (Perkins et al. Reference Perkins, Phillips and Pearce2013). The data was derived from the Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization Dataset (HIEF) (Drazanova Reference Drazanova2020).Footnote 22 We included the average percentage of women in cabinets and high-prestige portfolios within a regionFootnote 23 to control for diffusion effects (Appendix II, Table 8), as norms regarding women’s inclusion in executive office may percolate across countries (Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014; Bauer and Okpotor Reference Bauer and Okpotor2013). The addition of these variables did not change the results.

An Exploration on Mechanism: Education Matters

Our analysis highlighted a complex interplay between a leader’s gender, family ties, and influence on women’s cabinet representation, yet the mechanisms remain untested due to data limitations. We suggest educational attainment as a potential explanatory mechanism, hypothesizing that it may shape leaders’ propensity to nominate more women to cabinet roles. Corroborating this, national data shows a correlation between higher female tertiary education enrollment and increased women’s ministerial presence (Bego Reference Bego2014; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson 2005; Neundorf and Shorrocks Reference Neundorf and Shorrocks2022). Education fosters gender egalitarian views (Bolzendahl and Myers Reference Bolzendahl and Myers2004; Cunningham Reference Cunningham2008; Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Beutel, Barber and Thornton2005; Davis and Robinson Reference Davis and Robinson1991), whereas international educational exposure, particularly from Western democratic countries, broadens cultural understanding and promotes liberal values (Rosiers Reference Rosiers and Deconinck2018; Hadis Reference Hadis2005), making them more likely to democratize their home countries (Gift and Krcmaric Reference Gift and Krcmaric2017) and less inclined to initiate militarized interstate disputes (Barceló Reference Barceló2020). Consequently, it is plausible that such experiences may influence leaders to advance gender parity in their cabinets.

The educational paths of leaders are distinctly shaped by their family ties. Daniele and Geys (Reference Daniele and Geys2014) highlight the “Carnegie effect,” in which political dynasties dampen the educational pursuits of their successors, who rely on inherited electoral advantage rather than personal merit. Besley and Reynal-Querol (Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2011) corroborate this, finding hereditary leaders often have fewer academic credentials. Geys (Reference Geys2017) observes a similar trend in Italian local elections, where dynastic politicians show little incentive to bolster their human capital. In stark contrast, leaders connected to non-executive-leader political figures, or those without any political lineage, are posited to have greater impetus to seek higher education, potentially compensating for their lack of family-derived political capital (Folke et al. Reference Folke, Rickne and Smith2021; Spark et al. Reference Spark, Cox and Corbett2019). Female leaders without such ties, aiming for high office, may particularly pursue advanced degrees to mitigate against voter bias.

Socioeconomic barriers, however, can significantly impede educational access for women without family ties. “Son preference” in resource-limited settings often leads to unequal educational investment between sons and daughters, stymieing women’s educational opportunities (Alderman and King Reference Alderman and King1998; Baker and Milligan Reference Baker and Milligan2016). Such disparities are even more pronounced for women from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, limiting their chances for international study and the broadening of perspectives that come with it (Bouoiyour and Miftah Reference Bouoiyour and Miftah2016; Hannum et al. Reference Hannum, Kong and Zhang2009). Conversely, those from affluent backgrounds, often with family members who value Western education, will likely receive the necessary financial and informational support to pursue such opportunities (Salisbury et al. Reference Salisbury, Umbach, Paulsen and Pascarella2009; Simon and Ainsworth Reference Simon and Ainsworth2012). Female politicians linked to non-executive-leader political figures typically come from these higher socioeconomic classes, giving them access to superior education, including the chance to study in progressive Western environments. This socioeconomic privilege broadens their educational horizons and incentivizes them to signal their competence and capacity through academic achievements more assertively than their dynastic peers. Consequently, we suggest that female leaders with non-executive-leader ties may be more likely to have higher levels of education and study abroad in Western countries, enhancing their leadership profiles and potential for promoting gender parity within political arenas.

We obtained the data of leaders’ educational backgrounds from the Technocratic and Educational Dataset (TED) (Flores et al. Reference Flores, Lloyd and Nooruddin2023).Footnote 24 The outcome variable “highest degree of education” was coded on an ordinal scale from 0 (none) to 4 (graduate). The outcome variable “study abroad in Western countries” was coded as 1 if the leader studied abroad and the university he or she enrolled in was located in North America or Western Europe; 0 if the leader didn’t study abroad or the university was located elsewhere. The outcome variable “party ideology” is a binary variable with 1 for the leftist party and 0 otherwise.

Table 6 corroborates our hypothesis, revealing a significant nonlinear negative interaction between a leader’s gender and family ties in model 1 and model 2: female leaders with family ties to non-executive-leader political figures more often have higher levels of education and study abroad than dynastic female leaders. These experiences may potentially foster liberal and feminist values that encourage gender-equitable policies (Besley and Reynal-Querol Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2011; Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2014; Daniele and Geys Reference Daniele and Geys2014; Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Hughes and Barnes2021; Schoon et al. Reference Schoon, Cheng, Gale, Batty and Deary2010; Scott Reference Scott2022). In contrast, dynastic leaders may not share the impetus, whereas those without family ties may be socioeconomically constrained for such educational pursuits. While we discussed earlier that family ties may increase political capital, giving women leaders the leverage to diversify their cabinets, data limitations precluded us from directly testing this alternative mechanism. We suggest that political capital and educational exposure, as mechanisms for diversifying cabinets, are complementary rather than mutually exclusive. Female leaders with moderate family ties benefit from political capital and normative exposure, aiding female appointments, whereas those without face dual constraints.

Table 6. Mechanism: education v. party ideology

Note: Regression results are based on panel-correlated standard error model. Standard errors are in parentheses. t refers to the time-trending effect on leaders’ education and party ideology.

* p < .05.

** p <.001

Beyond the educational mechanism, family plays a key role in political socialization among youth (Jennings and Niemi Reference Jennings and Niemi1974). The intergenerational transmission of partisanship and ideology within politically active families is well-documented (Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009). Variations in family ties may directly impart distinct gender norms across generations. Gender norms often align with party ideologies, where left-wing parties generally advocate for progressive women’s political roles (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Bego Reference Bego2014; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). Leaders from families with political ties, typically from higher socioeconomic strata, may gravitate toward right-wing party affiliations, whereas those without family ties may lean left. This dynamic raises the possibility that party ideology could eclipse educational factors in shaping female cabinet appointments. However, our analysis of this party-centric mechanism in model 3 of Table 6 revealed that family ties do not significantly sway female leaders’ partisanship. This finding reinforces the potential significance of education in guiding their decisions regarding cabinet appointments.

Conclusion

The present study provided a novel viewpoint on the growing body of research regarding the impact of female ascension to leadership roles on the increased representation of women in government cabinets. Central to our argument is the role of familial ties in shaping the leadership trajectory and governance approach of female leaders, an aspect informed by the commonality of women rising to power through family connections. Analyzing data from 160 countries from 1966 to 2021, our findings highlighted that female leaders generally favor the appointment of women. Yet, the nature of their family ties significantly influences this tendency — a concept we refer to as the Goldilocks effect. Family ties act as both a boon and a boundary to varying degrees, with female leaders associated with non-executive-leader political figures being more inclined to appoint women to their cabinets and high-profile positions than their dynastic counterparts or those without familial links. The Goldilocks effect has significant implications for understanding and fostering female political leadership. As women continue to break political glass ceilings, understanding the nuanced impact of family ties on their leadership styles and decision-making processes becomes increasingly vital. The principle offers a lens to critically evaluate and potentially guide the support structures and political strategies to empower future female leaders to promote gender equity in political representation.

Our findings lay a foundation for further exploration of the nexus of gender, family ties, and leadership. Questions remain about whether the Goldilocks effect extends to broader outcomes like economic progress, democratic evolution, and peace, and whether these outcomes are differentiated by gender. These areas represent untapped avenues for scholarly pursuit. Despite our exploratory analysis of educational attainment, we cannot empirically examine the mechanisms we theorize to drive these effects due to the limited availability of data on potential mediators. To fully unravel and validate the causal links, we will need to collect more detailed data and undertake additional qualitative and quantitative (e.g., experimental) work that evaluates the motivations and incentives of the electorate, as well as male and female leaders with different family ties across diverse sociopolitical contexts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X24000138.

Acknowledgments

The Institute of Public Governance at Peking University funded the research for this article (project IDs TDXM 202105 and YBXM 202210). The authors acknowledge Michelle Taylor-Robinson and other participants at the 80th MPSA Annual Conference “Women and Executive Politics” panel for their invaluable feedback on early drafts. They also acknowledge the editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.