7.1 Introduction

The Indian and Pakistani Acts provide for three-tiered, linear competition enforcement systems. If these systems work as envisaged in the competition legislations then only the specialist members of the first tier competition authorities, the CCI and CCP, will take cognisance of and evlauate anti-competitive practices as defined in the Indian and Pakistani Acts and in doing so will interpret and enforce the provisions of these Acts. Appeals from orders of the CCI or CCP will lie to the Indian and Pakistani Tribunals, also established under the Indian and Pakistani Acts, where these orders will be examined jointly by competition and judicial experts. Finally, appeals from orders of the Tribunals will lie to the Supreme Courts of the countries, where generalist judges sitting in their competition appellate jurisdiction, will assess these orders against norms prevalent in the country’s pre-existing legal system. It may be expected that as successive competition matters will proceed from the first to the third tiers of the competition enforcement system a dialogue between the authorities will emerge which in time will would not only bring these authorities into greater alignment with each other but also allow the competition enforcement systems, to be shaped by the principles and norms of the pre-existing legal systems which will facilitate the gradual integration of the competition law into these systems .

In actual fact, however, competition matters do not proceed along the linear competition enforcement pathways envisaged in the competition legislations and frequently depart from it to interact with the general courts in the two countries. The manner in which the general courts react to these competition matters determines when and whether the matters are returned to the competition enforcement pathways to finally move towards their conclusions. However, in focusing on the relationship of the three competition authorities with each other without reference to possible interference from the general courts pre-existing in the countries, the Indian and Pakistani Acts underplay the significance or impact of such interventions. In doing so these Acts suggest that interventions from the general courts are either likely to be infrequent or even if not infrequent, are likely to be easily addressed so that they cause little or no disruption to the competition enforcement systems. This chapter explores this implicit assumption by examining the extent and nature of interactions between the competition enforcement systems established in pursuance of the adopted competition legislations and pre-existing legal systems in India and Pakistan. It argues that not only are the interactions between the Indian and Pakistani Acts and the pre-existing legal systems in the two countries largely shaped by the strategies, mechanisms, and institutions through which the countries had initially adopted their respective competition legislations, but also that the nature and quality of these interactions has a discernible and significant impact on competition enforcement in these countries.

To this end the chapter is organised as follows: Section 7.2 maps the competition enforcement pathways established under the Indian and Pakistani Acts and identifies the likely points of interaction between the competition enforcement systems and pre-existing legal systems in these countries; Section 7.3 examines and compares interactions that emanate from interim orders of the CCI and CCP and explores reasons for the divergence between the two; Section 7.4 compares the interactions in India and Pakistan with the aim of understanding these in the context of the strategies, mechanisms, and institutions through which they had adopted their respective competition legislations; Section 7.5 considers the effects of these interactions on the enforcement and evolution of the competition legislations and the pace at and extent to which these legislations are likely to integrate into the pre-existing legal systems of their countries.

7.2 Mapping the ‘Interactions’ in the Indian and Pakistani Contexts

The interaction between adopted competition legislations in India and Pakistan and their pre-existing legal systems takes place through the competition authorities established under the Indian and Pakistani Acts – the CCI, the CCP, and the Indian and Pakistani Tribunals – and the pre-existing general courts established under their respective Constitutions. In both India and Pakistan general courts mean the high courts, hearing and deciding petitions in their inherent constitutional jurisdiction and the Supreme Courts hearing appeals from these matters also in their constitutional rather than competition jurisdictions.

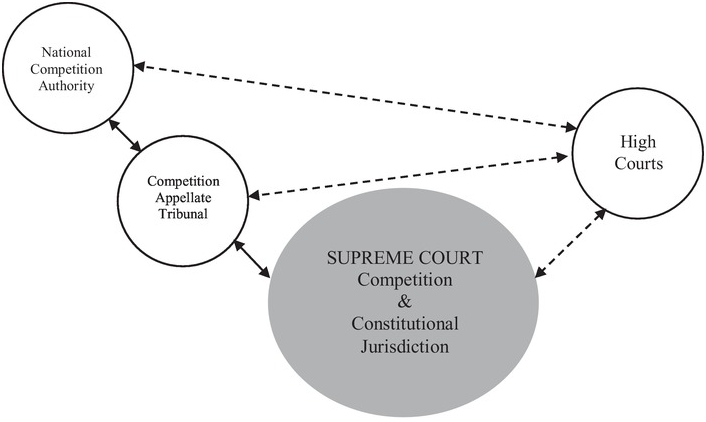

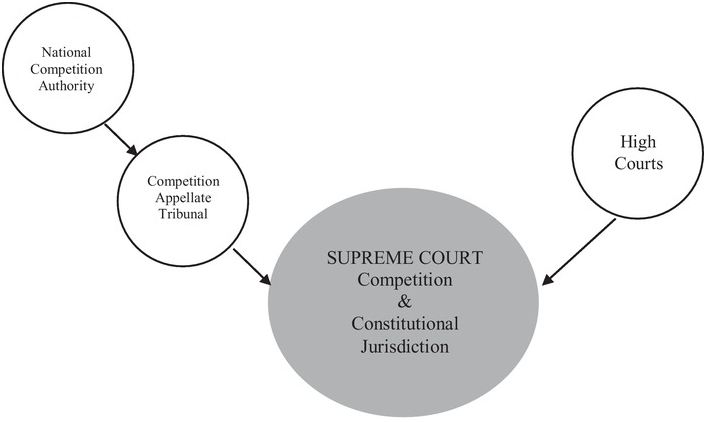

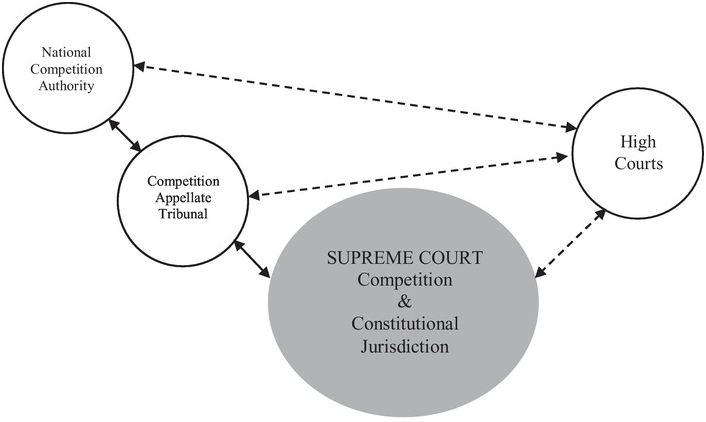

The competition enforcement pathways envisaged under the Indian and Pakistani Acts begins with the national competition authorities, the CCI and CCP, proceed to the Indian and Pakistani Tribunals that are mandated to hear appeals from decisions of the CCI and CCP, and culminate in the Indian and Pakistani Supreme Courts sitting in their specially conferred competition appellate jurisdictions.Footnote 1 According to this pathway, the competition enforcement systems and the pre-existing legal systems interact at one point only: when the Supreme Court sitting in its competition appellate jurisdiction hears appeals from orders of the Tribunals and then too on limited grounds arising from the appealed orders (Figure 7.1).Footnote 2

Figure 7.1. Competition enforcement and the constitutional pathways

In both India and Pakistan, in addition to their competition appellate jurisdiction, the Supreme Courts also exercise constitutional and general appellate jurisdictions, and the competition enforcement systems also come into contact with the pre-existing systems when the high courts hear writ petitions from persons aggrieved by the actions or orders of the tier (the CCI and the CCP) and second tier (Indian and Pakistani Tribunals) competition authorities in exercise of their inherent constitutional jurisdictions.Footnote 3

Aggrieved parties may file petitions against proceedings pending before the CCI, the CCP, or the Indian and Pakistani Tribunals before the high courts under Article 226 of the Indian Constitution and Article 199 of the Pakistani Constitution. These nearly identical Articles allow persons aggrieved by the orders or actions of the government or of any natural or legal persons performing functions in connection with governmental affairs, to challenge these orders or actions before the relevant court on the ground that these infringe one or more of the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Indian or Pakistani Constitutions.Footnote 4 If, upon hearing a petition, the general court is satisfied that fundamental rights have been violated, it may, in exercise of its inherent constitutional jurisdiction, issue one or more of the following writs: (a) writ of mandamus and prohibition directing a person carrying out a function in connection with the affairs of the federation to refrain from doing anything he is not permitted to do or to do anything he is required to do; (b) writ of certiorari declaring that any act or proceeding performed by a person in connection with the affairs of the federation has been done without lawful authority and is without legal effect; (c) writ of habeas corpus directing that a person held in custody within the jurisdiction of the court may be presented in court; (d) writ of quo warranto requiring a person holding public office to show the authority of law under which he claims to hold that office. The high court may also issue interim restraining orders while these petitions remain pending.Footnote 5 The orders of both the CCI and the CCP qualify as functions in connection with the affairs of the Union or federation (in the case of India and Pakistan respectively) and the high courts in both countries have the power to issue one or more of these writs as may be appropriate (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2. Points of interaction between competition enforcement and pre-existing legal systems

The possibility of challenging the orders and actions of the first- and second-tier competition authorities before the general courts gives rise to two further possible points of interaction between the competition enforcement and constitutional systems: one between the first-tier competition authorities, ie the CCI and CCP and the high courts and the other between the second-tier competition authorities, ie the Indian and Pakistani Tribunals, and the high courts. There is no direct point of interaction with the Supreme Courts and they only hear appeals from orders of the high courts in these petitions. Although both these points of interaction are of interest, this chapter focuses only on the first (between the CCI and CCP and the high courts) due to the very limited available data for the Pakistani Tribunal which prevents a comparative analysis with orders from the Indian Tribunal.Footnote 6

The interaction between the first-tier competition authorities, the CCI and CCP, and the general courts in India and Pakistan is initiated when a person files a petition before a general court alleging a violation of its constitutional rights in the proceedings before the CCI or CCP, as the case may be. In hearing this petition in exercise of its inherent constitutional jurisdiction the court has the option to either immediately decide the matter by passing a final order or to allow further time for hearing and issue an interim restraining order for such time as the petition remains pending before it. If the general court issues an order deciding and disposing of the petition the matter may either be returned to the CCI or the CCP, where it may proceed along the competition enforcement pathway, or the order of the general court may be appealed to the Supreme Court in its constitutional jurisdiction, whereby it still remains in the constitutional system and the competition system remains suspended most in compliance with a restraining order issued by the high courts. The Supreme Court, sitting in its constitutional jurisdiction, also has the option to decide the matter and to either return it to the high court for further action, thereby retaining it within the pre-existing legal system, or to the CCI or CCP directly from where it may proceed along the competition enforcement pathway. If, instead of issuing an order deciding and disposing of the petition, the general court issues an interim restraining order the matter may still be returned to the CCI and CCP, albeit with restrictions on how they may proceed. The CCI or the CCP as the case may be, then have the option to comply with the interim order of the general court or appeal it to the Supreme Court in its constitutional jurisdiction. In either case the matter remains in the pre-existing legal system and is not returned to the competition enforcement system until such time as it is finally decided by the general courts.

This discussion suggests that as important as the number of orders or actions of the CCI or the CCP that are challenged before the general courts, is the response of the general courts to these challenges. While filing a petition is a constitutional right, the response of the courts is a reflection of judicial discretion and capacity and impacts the nature, quality, and speed of competition enforcement in India or Pakistan, and the pace at and extent to which the Indian and Pakistani Acts integrate into their respective pre-existing legal systems. If the general court issues a final decision disposing of the petition before it – regardless of whether it decides in favour of the competition authority or the aggrieved party – and if the parties refrain from appealing the order in the constitutional jurisdiction, the matter is returned to the competition authority and proceeds along the competition enforcement pathway, albeit in the manner directed by the courts. In such a situation, the interaction between the competition enforcement systems and pre-existing systems supports competition enforcement by providing guidance and clarity and thereby enhancing its compatibility with the context and its legitimacy in it. If, however, the general court issues an interim order simply restraining or restricting the competition authority, it not only fails to provide clarity and guidance but also suspends competition enforcement. The longer such a restraining order remains in place the greater the erosion not only of the effectiveness of competition enforcement but also the legitimacy of the entire competition enforcement system.

7.3 ‘Interactions’ in India and Pakistan

Parties aggrieved by orders or actions of the CCI and CCP in both India and Pakistan have filed petitions before the general courts. While in India these petitions have generally been filed against interim orders of the CCI, in Pakistan challenges have historically been brought against final as well as interim orders of the CCP. This section compares the challenges brought against the interim orders of the CCI and CCPFootnote 7 and explores reasons for the divergence between the Indian and Pakistani experience.Footnote 8

7.3.1 Interaction between CCI and the General Courts

In the majority of petitions filed against the CCI’s interim orders, aggrieved parties sought from the general courts writs of mandamus and prohibition, certiorari and quo warranto, ie they requested the courts to direct that the CCI should refrain from doing something it was not permitted to do or to do something it was required to do; declare that an act or proceeding performed by the CCI had been performed without lawful authority and was therefore, without legal effect; or require the CCI to show the legal authority for its actions.Footnote 9

One ground repeatedly raised before the general courts was that the CCI did not have the jurisdiction to hear matters that had been commenced before its predecessor anti-monopoly authority, particularly if the anti-monopoly authority had initiated an investigation but failed to complete it. In response, several general courts unequivocally declared this ground to be without merit and directed the petitioners to submit to the CCI’s jurisdiction.Footnote 10 A further related point raised before the general courts was that the CCI did not have the authority to exercise its jurisdiction in respect of practices that had commenced before the relevant provisions of the Indian Act had been brought into force. In responding to all petitions in which this ground was raised, the general courts clarified that the CCI did indeed have the jurisdiction to examine conduct that had commenced prior to the relevant provisions coming into force, provided such conduct had continued even after the coming into force of these provisions.Footnote 11 In at least one case, the aggrieved party challenged the CCI’s power to issue a show-cause notice on the ground that doing so was tantamount to the CCI pre-judging the case. In this matter the general court clarified that the CCI had the jurisdiction and the responsibility to form a preliminary view of a case and therefore the show cause notice was valid.Footnote 12 In certain other cases, parties challenged the CCI’s jurisdiction to initiate investigations, however, the general courts did not entertain these petitions or others filed on similar grounds.Footnote 13

In a few of its orders, in which the CCI records petitions filed in relation to the order, the CCI has recorded only the response of the general courts rather than the grounds on which the petitions had been filed. Regardless however, a review of the responses of the high courts as recorded in these orders suggests that the courts’ responses have varied according to the facts and circumstances of the case. In certain matters, the court expressly endorsed the CCI while in others it directed the CCI to take certain actions; in some cases, the courts restrained the CCI from pursuing one or more of the parties to the proceedings, and, in very rare instances, they restrained the CCI from continuing with the proceedings altogether. Importantly, in matters where the courts restrained the CCI from proceeding altogether they did so for a limited period only.Footnote 14

In certain proceedings pending before the CCI the complainant itself approached the courts. For instance, in one matter the complainant approached the court for interim relief against the defendants, while the matter was still pending before the CCI, however, the court dismissed the petition and directed the complainant to approach the CCI instead.Footnote 15 In another matter the complainant asked the court to direct the CCI to hear an application on an urgent basisFootnote 16 and in at least one recent case, rather than waiting for the court to issue an order in a petition brought against its proceedings, the CCI voluntarily gave an undertaking that it would not to take adverse action against the defendants while the petitions remained pending before the court.Footnote 17

Overall, the responses of the general courts to petitions from proceedings pending before the CCI suggest that in issuing more final rather than interim orders, the courts have dealt decisively with the objections raised against the CCI, and in deciding these petitions relatively soon after these were filed they have also dealt with these with reasonable alacrity.Footnote 18 It is also evident that decisions of the courts throughout India have formed valuable precedents for the CCI in subsequent proceedings. For instance, the CCI has cited Delhi High Court’s decision in the Interglobe and the Gujarat Guardian petitionsFootnote 19 in several later orders, including its orders in Varca Druggist & Chemist and others v Chemists & Druggists Association Goa;Footnote 20 In re Cartelization by Cement Manufacturers case,Footnote 21 and Re Alleged Cartelization by Cement Manufacturers v Shree Cement Limited and others.Footnote 22 Similarly, the CCI has cited the order of the Bombay High Court in the Kingfisher caseFootnote 23 in a number of its subsequent orders, including its order in Chemists & Druggists Association Goa case;Footnote 24 In re Cartelization by Cement Manufacturers case;Footnote 25 Shree Cement case;Footnote 26 Shri Sonam Sharma v Apple Inc. USA & others;Footnote 27 In re Alleged cartelisation by steel producers;Footnote 28 Shri Sunil Bansal & others v Jaiprakash Associates Ltd and others;Footnote 29 and Builders Association of India v Cement Manufacturers Association and others.Footnote 30

7.3.2 CCP’s Interim Orders and Challenges before the General Courts in Pakistan

Unlike India where petitions were primarily filed against orders issued by the CCI in the course of proceedings, in Pakistan petitions were filed to challenge show-cause notices and interim orders issued by the CCP as well as to challenge its final orders. However, for the purpose of comparison with India, this section only considers petitions filed against the CCP’s show-cause notices or interim orders.Footnote 31 These petitions may be further divided into two groups: the first comprising petitions filed in the period when the 2007 Ordinance was in force (‘the first group of petitions’) and the second comprising petitions filed after the 2009 and 2010 Ordinances were brought into force and includes the period up to and after the enactment of the Pakistani Act (‘the second group of petitions’). In both the first and second group of petitions, parties approached the general courts to seek writs directing the CCP to refrain from doing what it was not permitted to do or to do what it is required to do (writs of mandamus and prohibition); writs declaring that the CCP’s given act or proceeding was without lawful authority and without legal effect (writs of certiorari); or writs requiring the CCP or its officers to show the authority under which they claimed to hold office (writs of quo warranto).Footnote 32

In the first group of petitions, the grounds on which parties sought these writs included that the show-cause notice issued by the CCP was not in accordance with the law; certain sections of the 2007 Ordinance, and, therefore, the CCP’s actions in exercise of its powers under these sections, were ultra vires the Pakistani ConstitutionFootnote 33 and contrary to the fundamental rights guaranteed under it;Footnote 34 the subject of competition was not listed in the Pakistani Constitution’s Federal Legislative List and, therefore, the president was not competent to promulgate the 2007 Ordinance; and that the CCP did not have the jurisdiction under the 2007 Ordinance to initiate proceedings against the petitioners.Footnote 35 In the majority of instances, the courts simply accepted the petitions for hearing and issued interim orders restraining the CCP from proceeding until the next date of hearing, without scrutinising the grounds on which these had been filed. On subsequent hearings the court simply extended the restraining order until the next hearing and allowed the status quo to continue still without scrutinising the grounds on which the petitions had been filed. A ground raised repeatedly in the second group of petitions, particularly in the period in which the 2007 Ordinance had lapsed and the Pakistani Act was still to be enacted (ie in the period in which the 2009 and 2010 Ordinances were in force), was that the CCP did not have the legal competence to issue show-cause notices until such time as the legislature had ratified the Ordinances in compliance with the Pakistani Supreme Court’s order in Sindh High Court Bar Association v Federation of Pakistan.Footnote 36

Perhaps the most important petition in the first group of petitions was filed by the Liquefied Petroleum Gas Association of Pakistan (LPGAP) in which the LPGAP challenged the show-cause notice issued by the CCP to the LPGAP and its members and sought a restraining order from the court. The high court allowed the petition and restrained the CCP from acting on its show-cause notice. The CCP challenged the high court’s decision before the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court set aside the restraining order of the high court and directed the CCP to first decide the issue of jurisdiction. The Supreme Court also directed the CCP to ‘voluntarily’ commit to the court that it would not take any adverse action against LPGAP until such time as the petition remained pending. This meant that although the CCP could continue hearing the matter to issue a final order, it could not recover the penalty it had imposed as doing so would be tantamount to taking ‘an adverse action’ contrary to the undertaking it had given to the Supreme Court.Footnote 37 In October 2020, nearly eleven years after the petitions were filed the Lahore High Court finally decided the LPGAP petition along with ninety-two others in sectors as diverse as accountancy, automobiles, cement, dairy, developers, education, fertiliser, healthcare, food, oil and refineries, paints, power, real estate, sugar, and telecom.Footnote 38 However, both the CCP and the original petitioners appealed the order before the Pakistani Supreme Court and remain pending at the time of writing.

Another important petition from the first group of petitions that also qualifies as a second group petition relates to the CCP’s proceedings against the All Pakistan Cement Manufacturers’ Association (APCMA). On 28 October 2008 the CCP had issued a show-cause notice to APCMA and its members which the parties had then challenged before the Islamabad High Court. Although at first the court by its order dated 10 November 2008 restrained the CCP from passing a final order against the defendants, by a further order dated 5 December 2008 it dismissed the petitions as ‘premature’ and allowed the CCP to continue with the hearings. Given this reprieve from the high court, the CCP scheduled a hearing for APCMA and its members for 3 August 2009. In the meantime, however, the parties approached the Lahore High Court and obtained yet another injunction against the CCP. The Lahore High Court vacated this second injunction on 24 August 2009 and allowed the CCP to continue with its hearings which culminated in the CCP issuing its final order on 27 August 2009.Footnote 39 However, on 31 August 2009, before the CCP could take any steps to enforce its order, the Lahore High Court issued yet another interim order, this time restraining the CCP from taking any adverse action against APCMA and its members.Footnote 40 The petitions filed in the APCMA matter have also been decided by the Lahore High Court’s October 2020 order in the LPGAP petitions, and the member cement companies of the APCMA have also challenged the Lahore High Court’s order to the Supreme Court where it presently remains pending.Footnote 41

The nature and quality of the interactions between the CCP and the general courts in Pakistan has had a considerable impact on subsequent proceedings before the CCP, however, unlike India, this impact has been largely obstructive rather than supportive. Instead of clarifying the CCP’s position and thereby providing it guidance in issuing its subsequent orders, the orders of the high courts provided grounds for other parties aggrieved by the actions and orders of the CCP to launch further petitions against the CCP. For example, when the CCP initiated proceedings against the Pakistan Sugar Mills Association (PSMA) and its members the PSMA and its members relied on Sindh High Court’s interim order in the Mirpurkhas Sugar Mills petitionFootnote 42 to obtain further restraining orders against the CCP.Footnote 43 Similarly, the Lahore High Court’s decision in the LPGAP caseFootnote 44 opened floodgates of interim injunctions against show-cause notices issued by the CCP. Often, the high courts granted these injunctions at the first hearing mostly because ‘other constitutional petitions raising similar issues have already been heard by [the] Court’ and without any scrutiny of the grounds on which the petition had been filed.Footnote 45 Although the CCP challenged a number of such interim injunctions before the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court mostly preferred to mediate between the CCP and the high courts rather than taking decisive action and allowed the CCP to continue with the proceedings while restraining it (or asking it ‘voluntarily’ restrain) from taking any adverse action against the petitioners, while directing the high courts to hear and expeditiously decide the pending petitions.Footnote 46

7.3.3 The Divergence in the Indian and Pakistani Experience: Are Court Systems Responsible?

Notwithstanding that only a comparably small proportion of orders of the CCI and CCP were challenged in writ petitions before the general courts in India and Pakistan and sought nearly identical writs from the courts, the interactions between the competition enforcement systems (as represented by the CCI and CCP respectively) and the pre-existing legal systems of the countries (as represented by their general courts) differ on two important counts: first, the grounds on which the aggrieved parties brought these petitions, and second, the manner in which the courts responded to these challenges.

The grounds on which parties to proceedings pending before the CCI invoked the inherent constitutional jurisdiction of the Indian general courts are primarily procedural in nature. For instance, the petitions call into question the CCI’s authority to take notice of certain allegedly anti-competitive practices or the manner in which the CCI takes such notice. On the other hand, grounds on which aggrieved parties in Pakistan approached the Pakistani general courts are both procedural and substantive. While the procedural grounds raised in petitions filed before the Pakistani courts are comparable to those raised before the Indian courts, the substantive grounds are linked to the circumstances in and mechanisms through which the Pakistani competition legislations were promulgated. Some of the most repeated substantive grounds in the Pakistani petitions include calling into question the constitutionality of the Pakistani competition legislation; the validity and legitimacy of the CCP; and the legality of its power to initiate and pursue proceedings against the petitioning entities. It is further interesting to note that in the Pakistani context substantive grounds appear more frequently than procedural grounds in petitions filed from proceedings of the CCP.

An important aspect of the response of the general courts to petitions filed before them is the speed with which they delivered their response. The Indian general courts have mostly responded to the petitions stemming from proceedings pending before the CCI with reasonable alacrity and clarity and have utilised a relatively wide range of legal tools available to them rather than simply restraining the CCI indefinitely from continuing with the proceedings. In doing so the Indian general courts have supported the CCI’s operations and have helped bring the competition enforcement system into alignment internally with its successive tiers as well as externally with India’s pre-existing legal system by enhancing its compatibility and legitimacy in the Indian context. In comparison, the response of the Pakistani general courts to the petitions filed before them appears largely hesitant, and has the effect of impeding rather than facilitating the operation of the CCP. The most common response of the Pakistani general courts to the petitions coming before them has been to issue a restraining order at the very first hearing often without providing the CCP an opportunity to present its case. In nearly all matters in which they have issued ex parte restraining orders, the courts have simply extended the restraint at subsequent hearings rather than engaging with the petition on its merits. The reluctance of the Pakistani general courts to decide the petitions on their merits and their tendency to easily restrain the CCP led to more and more petitions being brought before the courts and more damagingly, left the CCP in a state of legal uncertainty which cast a long shadow not only on the CCP’s ability to enforce its orders but also made it hesitant about initiating proceedings against the most powerful business actors in the country who had easy recourse to the general courts. In 2020, after avoiding competition petititions for nearly eleven years the general courts took the first decisive steps in issuing an orders in the LPG Association of Pakistan v.Federation of Pakistan and others (2021 C L D 214) and in Islamabad Feeds (Private) Limited and others v. Federation of Pakistan, however, these matters are still pending before the Supreme Court and it is likely that the time lost due to the intitial delay has adversely and to some extent irreversibly impacted the CCP’s domestic legitimacy which may continue to hinder meaningful competition enforcement in the country.

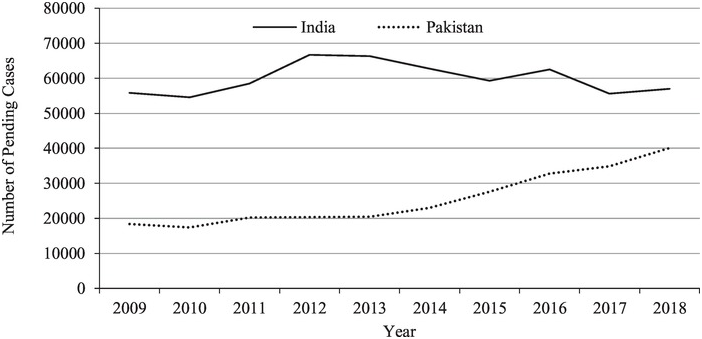

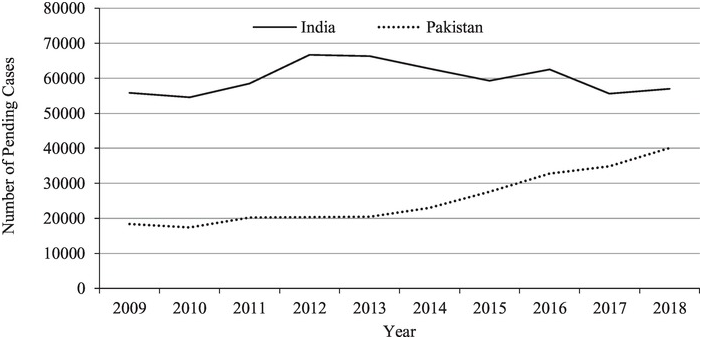

It is often argued that the delay on the part of the Pakistani general courts in responding to the competition matters is simply another manifestation of the general problem of endemic delay in the Pakistani legal system. However, the problem of delay is not unique to Pakistan and it is undisputable that both the Indian and Pakistani legal systems keep cases pending for inordinately long periods of time is.Footnote 47 According to the Annual Reports of the Indian and Pakistani Supreme Courts, regardless of the number of cases instituted or disposed of by the Supreme Courts in a given year, the number of cases pending before them remains relatively constant over time.Footnote 48 Given that the Indian and Pakistani Supreme Courts are the apex judicial bodies and responsible for monitoring the operations of the high courts in their respective countries, the delay at the Supreme Court level is likely to be replicated in the high courts (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3. Comparison of cases pending before the Supreme Courts of India and Pakistan (2009–18)

If, as is commonly suggested, the delayed response of the Pakistani general courts to competition-related petitions filed before them is due to the endemic delay inherent in Pakistan’s pre-existing legal system, then such a delay in disposing of competition matters would also have been evident in India which suffers from the same problem, and Indian general courts would not have disposed of a higher proportion of competition-related challenges filed before them than their Pakistani counterparts. The disparity in the rates of disposal of competition-related petitions in the two countries suggests it is important to look beyond the endemic delay argument to discover another more plausible explanation for the attitude of the courts towards competition petitions in the two countries.

7.4 Adoption Processes: Another Explanation for the Interactions

An important explanation for the differing responses of the Indian and Pakistani general courts to competition-related petitions filed before them lies in the very different processes through which the countries had adopted the competition legislations and the institutions they had engaged in this regard. It has already been discussed (in Chapter 2) that in India the adoption was carried out through a reasonably wide range of bottom-up, participatory and inclusive institutions, while Pakistan relied almost exclusively on a limited number of top-down, exclusive institutions. This section builds on this discussion to examine the extent to which India and Pakistan engaged their respective judiciary along with the executive and the legislature at the adoption stage and evaluates how this may have affected the subsequent interactions between the competition enforcement and pre-existing legal systems in the two countries.

7.4.1 Engagement of the Judiciary in the Indian and Pakistani Adoption Processes

The judiciary’s understanding of the context and aims of the competition legislation is commensurate with the phase of the adoption process at which it engages with the competition legislation and on the nature and extent of this engagement. In turn the level of the judiciary’s understanding of the competition legislation influences its attitude towards it and its interest in deciding petitions arising from or in relation to it.

The Indian judiciary first engaged with the Indian Act when the Brahm Dutt petition challenging the constitutionality of the Indian Act was brought before the Supreme Court immediately after the first round of deliberation and enactment at the adoption stage had been completed but before the commencement of the implementation stage of the Indian Act.Footnote 49 The petition required the Supreme Court to evaluate the scheme of the Act particularly the provisions relating to the competition authority acting as an adjudicatory body. in light of the Indian Constitution and tasked the Supreme Court to direct the government to appropriately amend the Act to ensure its compliance with the principle of separation of powers enshrined in the Indian Constitution.

Although the Indian Supreme Court disposed of this appeal on the basis of an undertaking given by the government its early engagement with the Act had a three-pronged effect: in requiring the government to amend the Indian Act to bring it in conformity with the Indian Constitution, the Supreme Court generated a second round of deliberation and enactment which helped enhance the Indian Act’s compatibility with India’s pre-existing legal system; in considering the scheme and substance of the Indian Act the Supreme Court generated awareness not only in the public but also within the superior judiciary of the rationale of the Act and the manner in which it was to be enforced; and, most importantly, by allowing the Act to continue its operations (albeit after necessary amendments) the Supreme Court endorsed and bolstered its domestic legitimacy. The enhanced compatibility and legitimacy of the Act subsequently contributed to a more productive interaction between the Act and the general courts.

In Pakistan, as in India, the judiciary engaged with the competition legislation after it had been through the first round of deliberation and enactment. In the case of Pakistan, however, this engagement came more than a year after the competition legislation had entered the implementation stage. Although the World Bank team, that had led the deliberation of the 2007 Ordinance, had met with one or two judges in the course of its discussions it had done so in their private rather than institutional capacity.Footnote 50 The judiciary as an institution first formally engaged with the competition legislation when the validity of the 2007 Ordinance was challenged before the Supreme Court.Footnote 51 However, unlike the Brahm Dutt petition in India, the petition brought before the Supreme Court of Pakistan did not address the scheme or provisions of the Pakistani competition legislation but only the circumstances and instruments through which it had been promulgated and saved. The core aim of the petition was to seek the annulment of the declaration of emergency which had allowed the 2007 Ordinance among several other ordinances to remain valid beyond the 120 days permitted by the Pakistani Constitution.Footnote 52 Consequently, in deciding this petition the Supreme Court addressed the 2007 Ordinance in the broader constitutional perspective only rather than on its substantive merits or demerits.

Another factor that further complicated the attitude of the Pakistani judiciary towards the 2007 Ordinance (and by extension, towards the competition legislation that followed) was that at the time of its promulgation the Pakistani judiciary was locked in an unprecedented battle with the executive and was also facing disturbance in its own ranks: the superior judiciary in Pakistan had refused to endorse the November 2007 declaration of emergency and barring a few exceptions, had opted to resign from office instead. In 2008 the judges that had resigned in protest against the emergency were restored to office, however, the relationship between the judiciary and the executive remained strained for some time especially as the elected government resisted compliance with the order of the Supreme Court in the Sindh High Court Bar Association matter.Footnote 53

The strained relationship between the executive and the judiciary in Pakistan and the failure of the government to provide permanent legal cover to the 2007 Ordinance had a negative effect on subsequent interactions between the CCP and the Pakistani general courts in at least three ways: first, the judiciary remained oblivious to the rationale for a competition law, of the core principles of competition, and the enforcement pathway envisaged in the 2007 Ordinance; second, although the engagement with the judiciary did provide an opportunity for further deliberation, the judiciary did not avail of this opportunity and therefore did not meaningfully enhance the compatibility and legitimacy of the competition legislation; and finally, and most damagingly, the judiciary remained hesitant to take decisive action in respect of competition matters either because it was reluctant to legitimise actions that were in any way connected with the declaration of emergency or because it simply wanted the government to resolve the legal foundations of its competition legislation before it decided these matters. The fact that the courts continued to restrain the CCP at the very first hearing of the petition even after the enactment of the Pakistani Act suggests that the initial hesitation had only compounded over time even when the reasons that had given rise to it in the first place, had long ceased to exist.Footnote 54

7.4.2 The Interplay of the Executive and the Legislature in the Adoption Process

In addition to the engagement of the judiciary in the adoption process, the interactions between the adopted competition legislations and the pre-existing legal systems of India and Pakistan have also been shaped by the extent to which the legislature and the executive have assumed ownership of these legislations and have taken an interest in and accepted responsibility for establishing the necessary infrastructure for the competition enforcement systems envisaged in the competition legislation.

This sense of ownership is generated by the engagement of a wide range of institutions from different branches of the state in the adoption process and is an aspect that the domestic legitimacy of the adopted legislation enjoys in its country. The adoption of the Indian Act through bottom-up, participatory, and inclusive institutions drawn from the executive, legislature, and, in the second round, also of the judiciary, meant that each branch of state accepted its own responsibility towards implementing the Indian Act which was an important factor in ensuring that the CCI and the Indian Tribunal were operationalised simultaneously.Footnote 55 The timely establishment of the Indian Tribunal ensured that parties aggrieved by actions or orders of the CCI had recourse to an independent, specialist appellate body. The Tribunal being operational not only reduced the numbers of constitutional petitions filed before general courts but also narrowed the grounds on which these were filed, as constitutional petitions are only maintainable if the aggrieved parties do not have an ‘an adequate alternate remedy’ available to them.Footnote 56 This also meant that matters brought before the general courts were largely within their competence and expertise further which facilitated their timely and clear resolution. This also meant that even if aggrieved parties invoked the jurisdiction of the general courts in matters that the general courts could not properly entertain, the general courts had the option and the clarity to direct the parties to file these before the Indian Tribunal.

Unlike India, Pakistan had first introduced its competition legislation through top-down, exclusive institutions drawn only from the executive. While doing so had the advantage of the legislation being promulgated swiftly and without interference particularly from the legislature, it also meant that the adopted legislation was not sufficiently adapted for the Pakistani context and lacked necessary domestic legitimacy. It also meant that there was limited institutional ownership of the competition legislation in the country: the Pakistani legislature only became aware of the rationale for and provisions of the competition legislation when it was finally placed before it in August 2010, after the legislation had already been in force for nearly three years. At this stage the legislature was neither interested in assuming ownership of the legislation nor in ensuring that the competition enforcement system envisaged in the legislation was fully and swiftly established. Further, even though the executive had been exclusively responsible for introducing competition legislation in the country, the fact that a particular government had taken the decision to do so in isolation from other organs of the state dampened the interest and ownership of the executive when a different government came into power. Therefore, even the executive did not feel any urgency to establish the necessary infrastructure to enforce the legislation.

The considerable delay on the part of the Pakistani government in operationalising the Tribunal led to a disconnect between the first and second tiers of the competition enforcement system in Pakistan and the subsequently established Pakistani Tribunal not only failed to engage meaningfully with the orders of the CCP but also remained deferential to it. This in turn prevented the third tier competition enforcement authority the Supreme Court – from playing its proper role as an appellate forum. The absence of an appropriate appellate remedy in the early years of competition enforcement meant that parties aggrieved by the CCP’s orders had no choice but to file petitions before the general courts whether they had a genuine grievance or simply wished to stall the CCP in particularly in the enforcement of its orders. This meant that at times these parties were constrained to manipulate the grounds on which the petitions were filed simply to meet the requirements of the constitutional jurisdiction of the courts. This not only increased the number of constitutional objections to the competition legislation and obfuscated the issues of real merit, but also increased manifold the number of petitions pending before the courts. Given that in Pakistan, like in India, general courts must entertain constitutional petitions if aggrieved parties do not have an adequate alternate remedy meant that the courts had no option but to admit these petitions because the Pakistani Tribunal had not been established and there was no option to redirect the petitions elsewhere.Footnote 57 The combination of a large number of petitions, some of which had been filed on spurious constitutional grounds, overwhelmed the courts and further contributed to the their hesitation to take decisive action in respect of the petitions filed before them.Footnote 58 As a result, no issues of real merit reached the Supreme Court and those that did had to be returned to the Tribunal for its consideration once it had been established and operationalised.

7.4.3 The Adoption Process and the Divergence in Interactions

The above discussion suggests that the adoption process impacts the interaction between the competition enforcement systems and the pre-existing legal systems of the adopting countries in complex and unexpected ways. It appears that obtaining feedback from a wider range of state institutions, particularly the judiciary, in deliberating the proposed legislation, and adapting the proposed legislation in light of the feedback received particularly from the judiciary, not only brings the legislation into alignment with the countries’ pre-existing legal systems and enhances its compatibility with the context but also generates broader-based acceptance and ownership for the legislation and thereby increases its domestic legitimacy.

For instance, in the case of India, the proposed competition legislation was deliberated and drafted primarily by the executive, however, rather than acting alone the executive consulted a wide range of stakeholders in this exercise. As the legislation progressed through the enactment phase it was first adapted in light of the feedback provided by the legislature and its standing committees (which also engaged with public stakeholders), and then according to the objections raised by the judiciary in respect of the structure and composition of the competition authorities proposed to be established by the Indian Act. Although this engagement with a wide range of institutions delayed the enforcement of the Indian Act from 2003 (when it was first enacted) to 2009 (when the CCI and the Tribunal were made operational), it provided the basis for a smoother, more productive interaction between the adopted competition legislation and the country’s pre-existing legal system. Given its early familiarity with and endorsement of the scheme and substance of the Indian Act, the judiciary in most instances was able to respond to the petitions filed before it on their merits rather than becoming embroiled in questions relating to the constitutionality of the Indian Act. Further, given its direct role in preparing the draft Act, the executive was also committed to establishing the competition enforcement system as envisaged in the Act and not only enjoyed the support of the legislature in doing so but also remained accountable to it.

The importance of a wide ranging and focused engagement with the proposed competition legislation is evident also in its absence in the Pakistani context. In Pakistan, as in India, the deliberation (including the drafting of the competition legislation) were led by the executive. However, unlike India, the Pakistani executive largely acted in isolation from other institutions and stakeholders and in fact outsourced the deliberation to a World Bank-led team and the drafting exercise to a European law firm. Also although the Pakistani legislature and judiciary also like its Indian counterparts engaged with the competition legislation, the legislature did so after the competition legislation had already been in force for three years and the judiciary only did so superficially and formally and that too only with the 2007 Ordinance. While the executive’s disproportionately larger role in the Pakistani adoption process had the important advantage of bringing the competition legislation into force without delay,Footnote 59 it also had the distinct disadvantage of weakening the compatibility and legitimacy of the adopted competition legislation, which in turn led to its constitutionality being called into question before the general courts and significantly complicating the interaction between the competition enforcement system and the country’s pre-existing legal system. The imbalance of power between the executive and the legislature also meant that the executive remained largely unaccountable for its acts and omissions.

7.5 Competition Enforcement Systems, Interactions, and Enforcement

Clear, productive, and supportive interactions between the adopted competition legislation, as represented by the competition enforcement systems, and the pre-existing legal systems in the adopting countries, as represented by their general courts, are important, if not necessary, for the successful enforcement of the adopted laws. A productive interaction between the adopted legislation and pre-existing legal system gradually enhances its compatibility and legitimacy in the adopting country. This in turn, allows the adopted legislation to be more fully understood, utilised, and applied in its country and facilitates its steady integration into the country’s pre-existing legal system.

It is also important to understand that the interactions between the adopted and pre-existing systems are not accidental and are in fact shaped by the mechanisms, strategies, and institutions through which the countries adopt their competition legislations. The impact of the adoption process is two-fold: the first limb of the impact stems from the extent to which the judiciary formally engages with the adoption process which shapes its perception and understanding of the competition legislation which in turn influences its response to matters relating to or arising from this legislation. The second limb of the impact derives from the nature and extent of the engagement of the executive and the legislature in the course of adoption which affects their subsequent commitment to establishing the competition enforcement systems envisaged in the competition legislations. A country such as India, which employs the more inclusive, bottom-up mechanism of socialisation for adopting the Indian Act, succeeds in developing a productive interaction between the competition enforcement and pre-existing legal systems while a country like Pakistan, that adopts its competition legislation through top-down, exclusive coercion, which leaves out the judiciary, legislature, and in some ways, even the executive from the process, not only adversely affects the response of the general courts to competition related challenges filed before them but also the commitment of the executive to make available the necessary resources for establishing the competition enforcement system and the legislature to hold it accountable for failing to do so.

Further, the extent of compatibility and legitimacy generated in the course of adoption creates a virtuous cycle: the compatibility and legitimacy generated for the competition legislation at the adoption stage facilitates the interaction between the competition enforcement system and the general courts at the implementation stage and the quality of the interactions between the two systems. Over time these interactions bring the competition enforcement system into alignment wtih the pre-existing legal system and thereby further bolster their compatibility and legitimacy in their domestic contexts.

This is evident in the Indian context, where the timely setting up and operationalising of the Indian Tribunal meant that there was an opportunity for aggrieved parties to have the CCI’s orders examined by an independent appellate forum and thereby to clarify important procedural and substantive issues. In the event that the orders of the Tribunal were appealed before the Supreme Court, it also had the opportunity to provide its generalist expertise which led to clarity in competition enforcement across all tiers of the competition enforcement system and brought them into alignment with each other. For instance, the order of the Tribunal in the Excel Crop Care caseFootnote 60 and before that in the SAIL case,Footnote 61 provided the CCI an important opportunity to seek and obtain clarity from the Supreme Court with regard to its penal strategy and procedure. Having obtained this clarity, the CCI was able to respond appropriately to similar objections in subsequent cases and thereby to deter repetition of these grounds before appellate fora or before the general courts.Footnote 62

The orders of the Tribunal and of the Supreme Court hearing appeals from these orders narrowed the possible grounds on which the CCI’s interim orders or proceedings could be challenged before the general courts in their inherent constitutional jurisdictions, and aligned the CCI’s procedures with the norms prevailing in India’s pre-existing legal system. This played an important role in reducing the number of frivolous petitions filed before the general courts and allowed the courts to deal with such petitions as came before them more effectively and expeditiously, thereby providing increasing clarity to the CCI. In this way, each order of the Supreme Court, whether in its competition or constitutional jurisdiction, enhanced the compatibility and legitimacy of the Indian Act and facilitated its integration into the country’s pre-existing legal system.

Conversely, the absence of a functional Tribunal in the early crucial years of Pakistan’s competition enforcement, directed towards the general courts all challenges in respect of proceedings pending before or even concluded by the CCP and led to the Pakistani competition legislation itself being challenged on a number of the grounds including that the competition enforcement system envisaged in the 2007, 2009, and 2010 Ordinances was contrary to the country’s pre-existing legal system. The large number of petitions that reached the general courts and the range of constitutional grounds on which these petitions were filed compounded the difficulty of the general courts and perhaps contributed to their reluctance to respond to these petitions. The failure of the general courts to engage with competition matters even if just to confirm at best the constitutionality of the CCP and of the legislation under which it was established, not only prevented the CCP from enforcing its orders but also halted the development of competition jurisprudence in the country. This in turn meant that the compatibility and legitimacy of the Pakistani legislation, remained as weak and superficial as it was when the legislation was first adopted if not further deteriorating over time.

The interactions between the CCP and the courts were expected to improve when the Pakistani Act was enacted and later when the government first operationalised the Tribunal: some of the constitutional objections to the Act were automatically resolved, and parties aggrieved by the CCP’s orders now had the option of approaching the Tribunal and, therefore, addressing the orders of the CCP on their merits. It was further expected that the more productive interaction with the general courts would in turn bolster the compatibility and legitimacy of the Pakistani Act as well as the extent to which it was understood, utilised, and applied in the country and recognised as a part of the Pakistani legal system. Unfortunately however, the actual impact of the establishment of the Tribunal remains difficult to ascertain given that the Tribunal does not publish its orders and the few of its orders that are available deal either with deceptive marketing practices or only superficially with anti-competitive practices. So far, the Pakistani Supreme Court has not issued orders in any of the several appeals from orders of the Pakistani Tribunal and, more recently, in respect of orders of the Lahore and Islamabad High Courts that have been appealed before it.