Introduction

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller health disparities

The term ‘Gypsy, Roma and Traveller’ (GRT) is commonly used in legislation and research in the UK. This term encapsulates a range of ethnic groups and traditionally nomadic communities including, but not limited to, Roma, English Gypsies, Welsh Gypsies, Scottish Gypsies or Travellers, Boaters, Showpeople, and Irish Travellers. Irish Travellers are an ethnic minority group in the UK with protection under the Equality Act since 2000. While the terminology ‘GRT’ aims to recognise these minority groups facing similar disadvantages, it also carries the risk of oversimplifying and grouping together a diverse array of communities, each with their own unique heritage, experiences and challenges. There is a clear need for research studies that focus on these groups separately to address this issue more effectively.

Irish Travellers and English, Scottish and Welsh Gypsy populations have significantly poorer physical and mental health compared with the general population (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Wayne, Valentine, Lessios and Yeh2013), even when socioeconomic status and ethnicity are controlled for (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Van Cleemput, Peters, Walters, Thomas and Cooper2007). Chronic respiratory conditions including asthma and bronchitis are far more prevalent in Irish Travellers and English, Scottish and Welsh Gypsies, with nearly five times as many bronchitis cases compared with the general population (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Van Cleemput, Peters, Walters, Thomas and Cooper2007). A national survey (Finney et al., Reference Finney, Nazroo, Becares, Kapadia and Shlomo2023) suggested that the pandemic may have worsened the social, economic and health situation for Roma, Gypsy and Irish Traveller populations. High levels of racial assaults, socio-economic deprivation and poor health were reported, with 62% having experienced a racial assault which was higher than any other ethnic group, one in three a physical assault, and Gypsy and Irish Traveller men were 12.4 times more likely to suffer from two or more health conditions than white British men. Compared with the general population, Irish Travellers have an estimated 11–15 year reduced life expectancy, a greater prevalence of co-morbidities, higher rates of alcohol and substance misuse (O’Donovan, Reference O’Donovan2016) and are more vulnerable in older age Coates et al. (Reference Coates, Anand and Norris2015). Research from Ireland indicates that the male Traveller suicide rate is seven times greater than the non-Traveller male population (All Ireland Traveller Health Study, 2010), with several factors implicated in this including experiences of racism and discrimination, social disadvantage, and community held beliefs about mental health and masculinity (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, McDonnell, Carroll and O’Donnell2023). A review of positive health in older Irish Travellers (Cush et al., Reference Cush, Walsh, Carroll, O’Donovan, Keogh, Scharf, MacFarlane and O’Shea2020) suggested cultural belonging and values, health awareness, accommodation circumstances, and culturally and need appropriate services contributed to positive health.

Depression in older adults and COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the second most common lung condition in the UK, following asthma, affecting approximately 1.3 million people in the UK (Asthma & Lung UK, 2023). The frequency and severity of COPD rises markedly with advancing age. Rates of depression and anxiety are significantly higher in adults with COPD (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Jick, Bothner and Meier2010; Yohannes et al., Reference Yohannes, Murri, Hanania, Regan, Iyer, Bhatt, Kim, Kinney, Wise, Eakin and Hoth2022). The exact reason for the increased prevalence of depression is unclear, but it is likely the result of a combination of factors such as illness chronicity, limited physical activity, social isolation and physiological effects of COPD contributing to a loss of self-efficacy and feelings of demoralisation (Yohannes et al., Reference Yohannes, Murri, Hanania, Regan, Iyer, Bhatt, Kim, Kinney, Wise, Eakin and Hoth2022). There is also evidence of a bi-directional relationship between symptoms of anxiety, depression and COPD, whereby symptoms of each illness can exacerbate the other (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Zhang, Kuo and Sharma2016; Yohannes and Alexopoulos, Reference Yohannes and Alexopoulos2014). Depression and anxiety in COPD patients contribute to decreased physical activity, worsening quality of life, reduced treatment adherence and increased risk of COPD exacerbations and hospitalisations (Atlantis et al., Reference Atlantis, Fahey, Cochrane and Smith2013; Lou et al., Reference Lou, Zhu, Chen, Zhang, Yu, Zhang, Chen, Zhang, Wu and Zhao2012; Yohannes et al., Reference Yohannes, Willgoss, Baldwin and Connolly2010).

Traveller health beliefs

Traveller and Gypsy communities are greatly under-represented in mental health research. As a result, findings often lack generalisability due to small sample sizes involving individuals from various subgroups (e.g. English Gypsies, Irish Travellers, Welsh Gypsies), which are unlikely to adequately represent the diversity of views and experiences within this heterogeneous community.

Research indicates that some Gypsies and Irish Travellers hold unique beliefs concerning health compared with non-Travellers, which can impact help-seeking, such as acceptance of ill health as part of life, stoicism in the face of adversity, and fatalistic attitudes to diagnoses like cancer (Van Cleemput et al., Reference Van Cleemput, Parry, Thomas, Peters and Cooper2007). Despite depression being common in these traditionally nomadic communities, Parry et al. (Reference Parry, Van Cleemput, Peters, Walters, Thomas and Cooper2007) found that Irish Travellers and Gypsies often consider it to be shameful to be discussed and that the stigma of having a mental illness not only affects the individual, but also negatively affects the way their whole family is viewed by the wider community (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Stone and Tyson2021).

Unexpected, preventable and traumatic deaths are common in the English Gypsy and Irish Traveller community (Rogers and Greenfields, Reference Rogers and Greenfields2017). Additionally, research has found that English Gypsy and Irish Travellers commonly normalise grief reactions that would be considered ‘pathological’ in other contexts (Shear et al., Reference Shear, Simon, Wall, Zisook, Neimeyer, Duan, Reynolds, Lebowitz, Sung, Ghesquiere, Gorscak, Clayton, Ito, Nakajima, Konishi, Melhem, Meert, Schiff, O’Connor and Keshaviah2011), by encouraging strong continuing bonds and heightened respect for the deceased, and avoiding discussion of their death (Rogers and Greenfields, Reference Rogers and Greenfields2017). Subsequently, bereavement is frequently a precipitating factor to depression, with the cultural normalisation of prolonged and profound grief in these communities (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Van Cleemput, Peters, Walters, Thomas and Cooper2007; Rogers and Greenfields, Reference Rogers and Greenfields2017).

Furthermore, Gypsies and Irish Travellers report fear and distrust of services and professionals due to personal and community experiences of racism and discrimination, for example fears of their children being removed if they disclose mental health issues (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Stone and Tyson2021; Van Cleemput et al., Reference Van Cleemput, Parry, Thomas, Peters and Cooper2007). The stigma associated with mental health difficulties, and fear of discrimination from services, are considered to contribute to avoidance of help-seeking by Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Stone and Tyson2021). Additionally, Gypsies and Irish Travellers reportedly face practical barriers to accessing health services such as GP surgeries requiring a fixed address, and completion of lengthy paperwork requiring a certain degree of written literacy (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Van Cleemput, Peters, Walters, Thomas and Cooper2007).

Higher rates of physical health conditions, internalised stigma, social deprivation, and poor access to healthcare may contribute to the reduced life expectancies seen across these traditionally nomadic communities. The cumulative effect any of the factors explored also puts Gypsies and Irish Travellers at increased risk of mental health difficulties (Cemlyn et al., Reference Cemlyn, Greenfields, Burnett, Matthews and Whitwell2010; Simko and Ginter, Reference Simko and Ginter2010; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Stone and Tyson2021). There are no specific guidelines for adapting therapy to meet Travellers and Gypsies’ needs; however, some individuals have indicated a desire for clinicians to be sensitive to their cultural beliefs, language and practices and adapt to their needs, for example by considering poorer literacy skills (Gavin, Reference Gavin2014).

Current best practice for depression and chronic physical health problems

To identify the most appropriate depression treatment for adults of any age with a chronic physical health problem, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2009) recommend following a 4–step model. At step 3, for moderate to severe depression, individual or group high-intensity CBT is recommended. The efficacy of CBT for depression in older adults has been demonstrated through randomised controlled trials (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Coulson and Howard2012). A meta-analysis found no significant differences in treatment outcomes from CBT between older adults (d=0.67) and working-age adults (d=0.74; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Straten, Smit and Andersson2009). Laidlaw and colleagues (Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2004) propose that age-specific adaptations to Beck et al.’s (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) model are required for optimal treatment outcomes in older adults, and developed an adapted CBT model that accounted for differences seen between older and younger adults (cohort beliefs, transitions in role investments, sociocultural context, physical health and intergenerational linkages). Furthermore, research has demonstrated that executive dysfunction commonly seen in older adults may reduce the benefits obtained from CBT (Mohlman and Gorman, Reference Mohlman and Gorman2005), therefore behavioural activation is encouraged in early treatment stages due to being less cognitively demanding and easily applied in everyday life, which may aid clients to experience benefits of therapy before moving towards cognitive approaches (Bilbrey et al., Reference Bilbrey, Laidlaw, Cassidy-Eagle, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2022).

Although there is less evidence for CBT in treating individuals with COPD than in older adults more generally, literature indicates that CBT is an effective treatment for reducing anxiety and depression symptoms in these patients. In a randomised controlled trial of 279 patients, with a mean age of 66.5, CBT led to significantly larger improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms, compared with self-help leaflets. Individuals who received CBT also had fewer respiratory admissions and emergency department attendances in the following 12 months, compared with the self-help group (Heslop-Marshall et al., Reference Heslop-Marshall, Baker, Carrick-Sen, Newton, Echevarria, Stenton, Jambon, Gray, Pearce, Burns and Soyza2018). A review by Williams and colleagues (Reference Williams, Johnston and Paquet2020) concluded that there is growing evidence indicating that high-intensity CBT leads to small but significant reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms and improvements in quality of life for people with COPD.

However, little research has investigated the efficacy of CBT for depression in older adults from diverse cultural backgrounds (Bilbrey et al., Reference Bilbrey, Laidlaw, Cassidy-Eagle, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2022), and none has considered the efficacy of CBT for depression in older adults from a Traveller community. Culturally adapted CBT has been defined as ‘making adjustments in how therapy is delivered, through the acquisition of awareness, knowledge, and skills related to a given culture, without compromising on theoretical underpinning of CBT’ (Naeem, Reference Naeem2011). Culturally adapted CBT has proven efficacious with Tamil refugees and asylum seekers, through use of cultural understanding of panic and anxiety, and culturally adapted metaphors, activities and stories. Furthermore, a systematic review of culturally adapted CBT for social anxiety disorder found that only modest culturally relevant modifications to existing treatment models was needed (e.g. therapists having good cultural knowledge, using the client’s preferred language where possible, focusing on psychoeducation initially and paying attention to culturally specific values, norms and beliefs) to garner positive outcomes for patients from minority groups (Jankowska, Reference Jankowska2019).

In the case of Travellers, adjusting for level of literacy and adapting use of written forms could be an appropriate adjustment as Finney et al. (Reference Finney, Nazroo, Becares, Kapadia and Shlomo2023) report that 51% of Gypsy Travellers have no educational qualifications. This case report examines the use of a short course of CBT in treating co-morbid depression and anxiety in an older adult with COPD, who identified as an Irish Traveller. It hopes to demonstrate the effectiveness of a culturally adapted, individualised formulation driven CBT intervention, and provide some suggestions for adaptations to consider when working with this community.

Presenting problem

John (pseudonym) was an 80-year-old male with COPD, who identified as an Irish Traveller. He was referred for CBT to a psychology service integrated within the respiratory team. In recent years, the exacerbation of his COPD, multiple bereavements (loss of son and wife in past two years to lung cancer), and social isolation due to COVID-19 resulted in John experiencing low mood and anxiety. At assessment, John’s Generalised Anxiety score (GAD–7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) was 21 (severe anxiety) and his Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) score was 20 (severe depression). At the assessment, John described a lack of motivation to engage with social or domestic activities, due to low mood and anxiety about doing things alone since his wife’s death. His daily routine was extremely repetitive and unstimulating. He would not leave the static mobile home alone due to fear of having panic attacks. John also described significant sleep interference due to worries and nightmares. He expressed a desire to be dead so he could be with his wife but explained that he did not believe in suicide. John expressed that the low mood was causing the most distress at the time.

He had previously been referred for low-intensity CBT through IAPT but reported finding it difficult to engage with the therapy over the ’phone, yet was unable to have face-to-face appointments due to his physical health difficulties. John had been prescribed a low dose of flupentixol for anxiety for over 20 years and reported feeling no noticeable benefits or side-effects from this.

Formulation

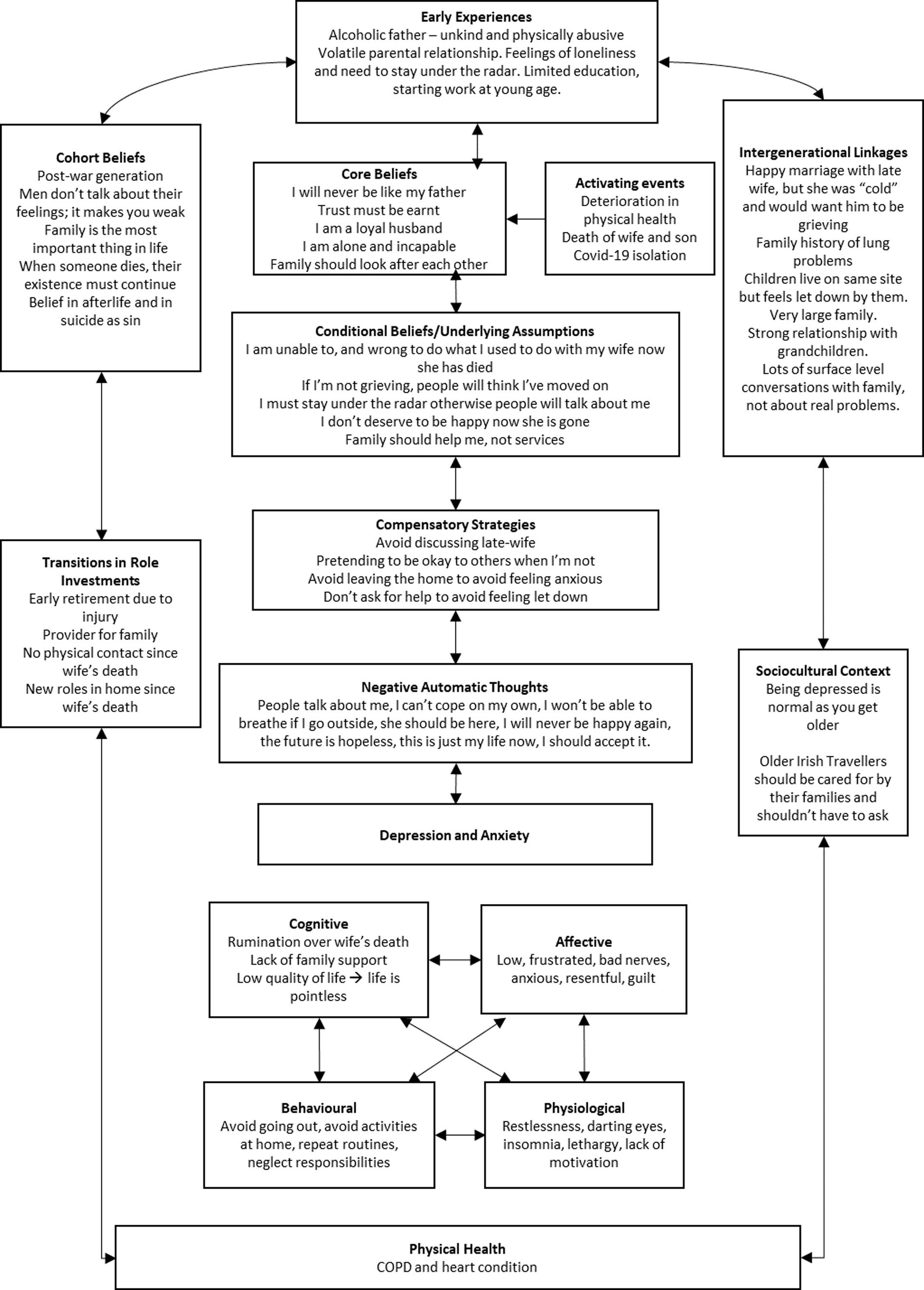

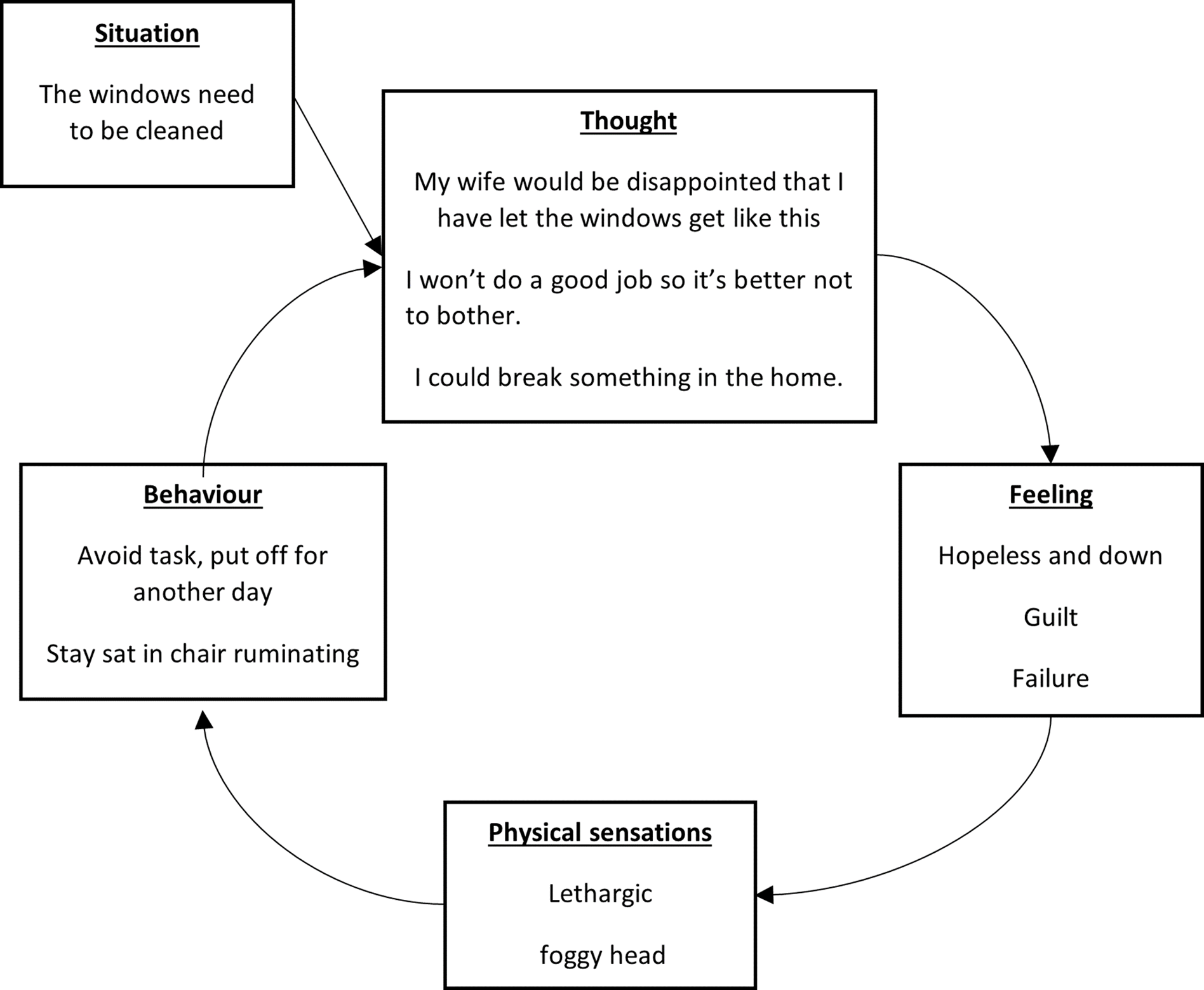

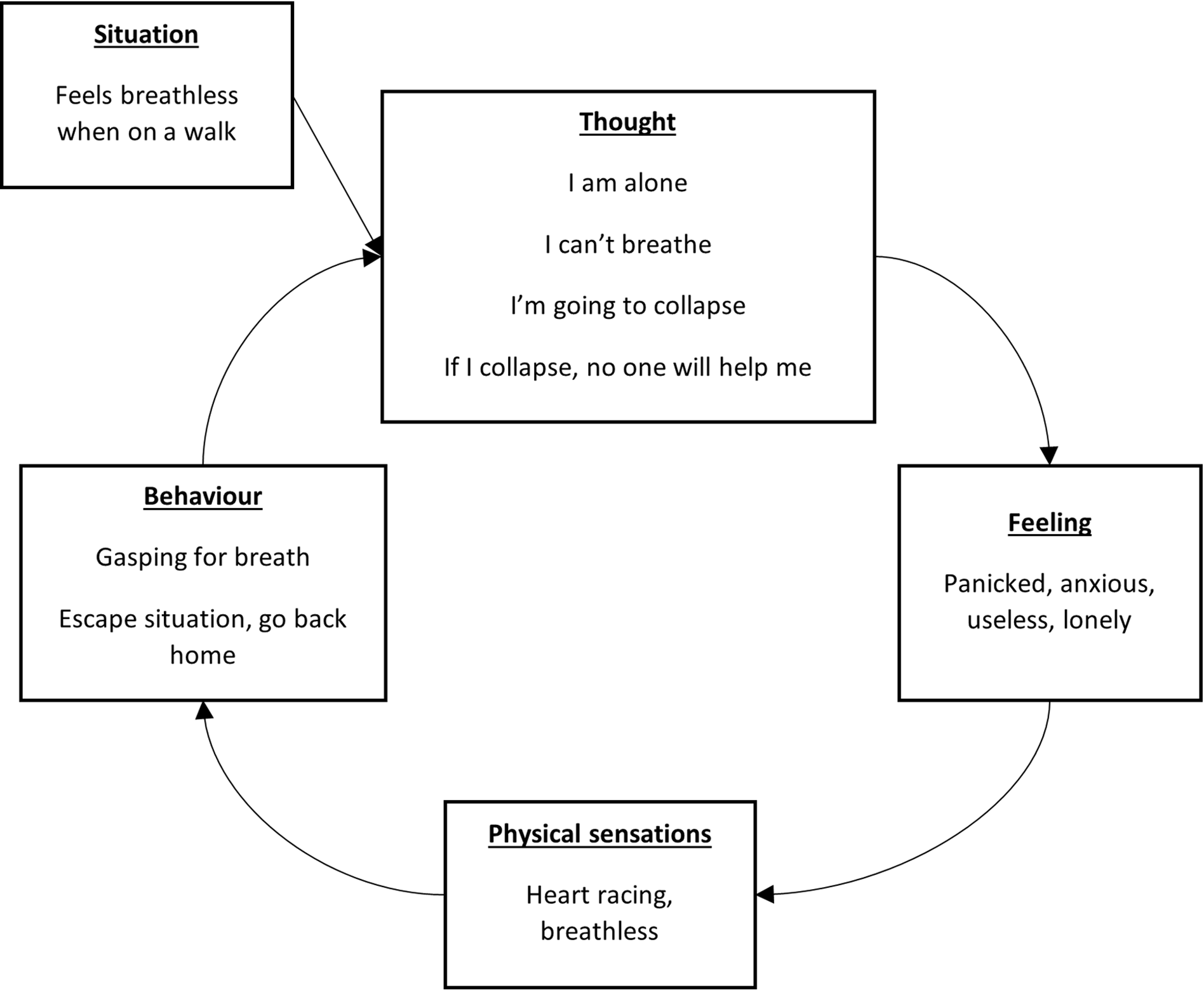

Using Laidlaw and colleagues’ (Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2004) comprehensive CBT model for older adults, the therapist and John developed a shared understanding of important contextual factors that the beliefs, behaviours and feelings that were maintaining John’s difficulties (Fig. 1). Padesky’s 5-aspects model of CBT (Figs 2 and 3) was used to formulate John’s recent difficulties in simple terms.

Figure 1. Beliefs, behaviours and feelings maintaining John’s difficulties.

Figure 2. Example of John’s recent difficulties in simple terms.

Figure 3. Example of John’s recent difficulties in simple terms.

The formulation suggested that John’s recent significant bereavements and decline in his physical health condition were the primary triggers for the current episode of low mood and anxiety. This experience was maintained by John’s beliefs about himself, his situation, and others, in addition to avoidance and use of safety behaviours. John had lost confidence in his ability to cope with daily tasks, while concurrently holding the belief that it is inappropriate to engage in activities that he previously did with his wife, which resulted in an over-generalised sense of helplessness and vulnerability, and decreased activity. Real symptoms of COPD (e.g. breathlessness) would be interpreted in a catastrophic fashion due to John’s beliefs of being incapable, resulting in fears of dying alone, which were reinforced by increased physiological and behaviour manifestations of anxiety. Subsequently, John would avoid activities that he previously enjoyed and would ruminate over his physical health and how much better life was before his wife passed away, resulting in low mood.

John identified that Irish Travellers place importance on continued bonds and respect for the deceased and was therefore fearful of judgement from his community if he re-engaged with life following his wife’s passing. His core beliefs of being a loyal and kind husband, unlike his father, strengthened his conviction that it would be ‘wrong’ to pursue activities without his wife. Furthermore, John’s Irish Traveller identity strongly influenced his beliefs about masculinity and the roles of family and non-Travellers, which prevented him from help-seeking sooner. The stigma associated with talking about mental health in the Irish Traveller community influenced John’s belief that men should be tough and not talk about their feelings. Therefore, John struggled to express his difficulties and needs to loved ones. Yet, John also held the belief that it was his family’s duty (rather than services) to notice his needs and help, inevitably resulting in him feeling disappointed, and increasingly lonely when these were not met. This rigid ‘should’ assumption resulted in him avoiding help-seeking from relatives, which compounded his sense of loneliness and disappointment. John’s belief that the Irish Traveller community are responsible for helping each other may have resulted in delayed professional help-seeking and progression of his difficulties.

Although John had fleeting thoughts that he would rather be dead as he could be in heaven with his wife, his strongly held Catholic belief that suicide is a sin, coupled with his remaining family members’ support, prevented him from reporting any intent to act on these thoughts.

Course of therapy

John received CBT sessions through the Psychological Interventions in Nursing and Community (PINC) service, within Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. This service places psychology staff within specialist physical health services to offer individual, transdiagnostic CBT (tCBT) (Mohlman and Gorman, Reference Mohlman and Gorman2005) to housebound patients. John was referred by a specialist respiratory nurse who identified that he may benefit from psychological therapy for anxiety and depression. John’s sessions were delivered by a trainee clinical psychologist under the supervision of a consultant clinical psychologist. Sessions were one hour long, delivered one-to-one in the patient’s home, and followed a transdiagnostic treatment approach. John received 10 sessions of CBT weekly, based on Beck et al.’s depression theory (1979), Clark’s (Reference Clark1986) cognitive theory of panic, and Mohlman and Gorman’s (Reference Mohlman and Gorman2005) tCBT. Relevant homework was set weekly in a collaborative manner. Depressive symptoms and risk to self were regularly assessed using the PHQ-9. A safety plan was created to help John manage these thoughts, although no significant concerns arose. Anxiety symptoms were assessed regularly using the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006).

Assessment and goal-setting

At assessment, John described feeling unmotivated (‘I don’t want to do nothing, I can’t seem to do nothing’) and hopeless. A typical morning involved looking at the chair his late wife (Margaret, pseudonym) used to sit in while thinking about her, and feeling lonely, resentful and depressed. He had the same lunch and watched the same films each day, while continuously thinking about Margaret. John had not been to the shops in over two years since soon after Margaret’s death, due to having a panic attack in which he was searching for her, felt distressed, struggled breathing, and left the shop. Since then, John had avoided doing activities alone due to thinking he could not cope and that he might collapse due to breathlessness. He also described that returning to activities he used to do with Margaret would be ‘wrong’ and disrespectful to his late wife. Therefore, John only left the house on rare occasions in the company of relatives. John reported feeling particularly lonely and more anxious about leaving the house due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This was because family members were visiting less due to his vulnerable health status, and leaving the home was a risk to his health. John described significant sleep interference with approximately three hours of sleep a night, which was often interrupted by nightmares. He found it very difficult to ‘switch his brain off’ before bed due to thoughts of his wife and her physical absence in bed. John viewed his situation as an inevitable outcome of loss and old age. He felt hopeless and had accepted that his situation could not improve. Thoughts about his wife made him upset every day and think he could not ‘carry on’.

John presented with depression, prolonged grief, and sleep and anxiety difficulties. However, he expressed that the low mood was causing him the most distress. It was also felt that John’s anxiety could be linked to his lack of confidence and sense of hopelessness. Additionally, John’s reluctance to discuss his late wife at the outset of therapy ruled out direct therapy for grief. It was decided that CBT for depression focused on improving mood through increased activity, and later reducing anxiety when out and about would be appropriate. The trainee predicted that disruption to ruminative thinking could also lead to secondary improvements in grief and sleep.

The therapist and John spent some time considering realistic goals for therapy, given his physical health difficulties. These were to:

-

Re-engage in activities that John used to enjoy;

-

Go to a shop alone;

-

Practise asking for, and allowing others to help.

Formulation

The trainee socialised John to the CBT model using a formulation of a recent depressive episode to help John to understand the vicious cycles of thoughts, feelings and safety behaviours that were maintaining his distress. The trainee provided psychoeducation about depression, anxiety and COPD throughout therapy to help normalise John’s experiences. Guided discovery facilitated John’s understanding of the overlap in COPD and anxiety symptoms, which helped restore a sense of control over his physical sensations.

Active intervention

In line with recommendations in older adults, early sessions focused on behavioural activation (Bilbrey et al., Reference Bilbrey, Laidlaw, Cassidy-Eagle, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2022), specifically within the home. This helped John to notice patterns between his mood state and his pleasure ratings when keeping active. Behavioural activation was successful at disrupting his ruminative thinking and increasing his mood. Graded task assignments and the five-minute rule were effective in providing John with a sense of achievement and increased his motivation to complete more challenging tasks. Achieving tasks helped to increase his confidence and challenge his core belief of being incapable, which positively reinforced further behaviours.

We then moved onto cognitive restructuring using thought records to identify negative automatic thoughts and unhelpful thinking patterns. Thought challenging John’s over-generalised memory and black and white thinking helped him to notice that he often achieved more than he thought he had in a day. He linked this change in perspective to feeling better about himself, which motivated him to continue challenging himself. With practice, John increasingly challenged his unhelpful thinking patterns independently.

John’s expectancy of others to mind-read his problem and offer help was challenged using theory A and theory B. Theory A was ‘others know I need support and choose not to give it, so they don’t care’. Theory B was ‘others don’t know I need help and if I ask them, they will help’. Through testing each theory by practising help-seeking, John was able to identify more evidence for theory B, which helped him to feel less lonely and more willing to seek help.

Behavioural experiments were used to test John’s belief that breathlessness would cause him to collapse. The trainee and John’s grandson carried out an over-breathing experiment to test John’s prediction. Through this, John learnt that over-breathing is an unhelpful safety behaviour that exacerbates symptoms of breathlessness and anxiety, but does not lead to collapse. This led John to feel less fearful of sensations of breathlessness, attributing them to harmless COPD and/or anxiety symptoms.

Following this, John tested his belief that when alone in a shop, he wouldn’t cope, would get breathless, collapse and nobody would help him. The task was to visit a charity shop on his own for 10 minutes with his grandson waiting outside (as a rescue factor). Instead, John took himself to the shop and spent over 15 minutes inside. He discovered that his prediction was incorrect; he didn’t collapse despite fear of breathlessness and coped well with the situation, reporting minimal anxiety. He repeated this experiment several times with increasing difficulty, which increased his confidence and broke the avoidance cycle in Fig. 3.

Cultural therapy adaptations

The therapist was aware of the possible taboo nature of mental health issues in Irish Traveller communities. Therefore, pathologising terms such as anxiety and depression were avoided and a shared understanding of John’s difficulties using his language (e.g. ‘my nerves are bad’) was used where possible. It is understood that ‘nerves’ is an accepted term used by many Irish Travellers to describe a range of mental health difficulties (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Stone and Tyson2021).

Beliefs held by John and his community about Irish Travellers not mixing with non-Travellers in social situations provided a challenge to therapy progress. John was not confident enough to practise behavioural exposure or behavioural experiments outside of the home alone but held a rigid belief that he couldn’t be seen outside with the trainee, as this would put them both at risk of ridicule from the community. Therefore, the therapist respected this boundary and explored John’s family structure to identify any family members who might be understanding of his difficulties and willing to support the therapy process. Research into culturally adapted CBT indicates that it can be beneficial to treatment and homework engagement if a family member is involved as a ‘co-therapist’ (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019). Therefore, John’s grandson (who also experienced anxiety) was invited to join the therapy sessions and helped to support John with activities outside of the home. This helped John to realise that his loved ones would help if he asked them to, in addition to enabling him to test out his fears in the real world.

A further barrier to therapy progress surfaced when attempts at cognitive restructuring through general population surveys and alternative perspectives offered by the therapist failed to improve John’s black and white thinking. John stated on several occasions that Irish Travellers ‘think differently’ to non-Travellers and that this was a fact that could not be disputed. Furthermore, John did not think it would be appropriate to administer a survey to an Irish Traveller community because he believed they would perceive this as intrusive, particularly in a community where discussion of mental health is taboo. Therefore, involvement of John’s family members was also crucial to gently challenging John’s beliefs and helping him to realise that while cultural beliefs did exist about certain topics (e.g. grief rituals, help-seeking, depression), his were often held more rigidly and strongly than those of family members. As a therapist not from this cultural background, it was imperative to respect cultural differences in beliefs and practices, and to allow the client to take the lead with whom and to what extent his difficulties were shared.

Research in Gypsies, Roma and Travellers indicates that they often share a collectivist culture, leading individuals to seek high levels of involvement in the care of their family members. However, experiences of healthcare professionals perceiving this to be disruptive can increase reluctance among these communities to engage with healthcare services (Atterbury, Reference Atterbury2010; Roman et al., Reference Roman, Gramma, Enache, Pârvu, Ioan, Moisa, Dumitraş and Chirita2014). A part of developing mutual respect with John’s family members involved being respectful of this cultural norm, while also ensuring John’s rights to privacy and confidentiality were recognised by all involved. John lived on the same mobile home site as several family members, and in a community where everybody knew each other. Family members would frequently walk into John’s home unannounced during therapy sessions, sit down and start conversation. John reported that this was due to them wanting to assess who the therapist was and to ensure their loved one was safe. John reported that this was normal and although he understood his right to a confidential space, he was comfortable with certain family members being present. The therapist used interruptions in therapy by family members as small behavioural experiments, for John to test out beliefs about help-seeking and ‘normal’ grief. Furthermore, John reported that everyone would notice the therapist’s arrival on the mobile home site and that wearing a lanyard when outside was important to ensure that others knew he was being visited by a professional, rather than a female friend.

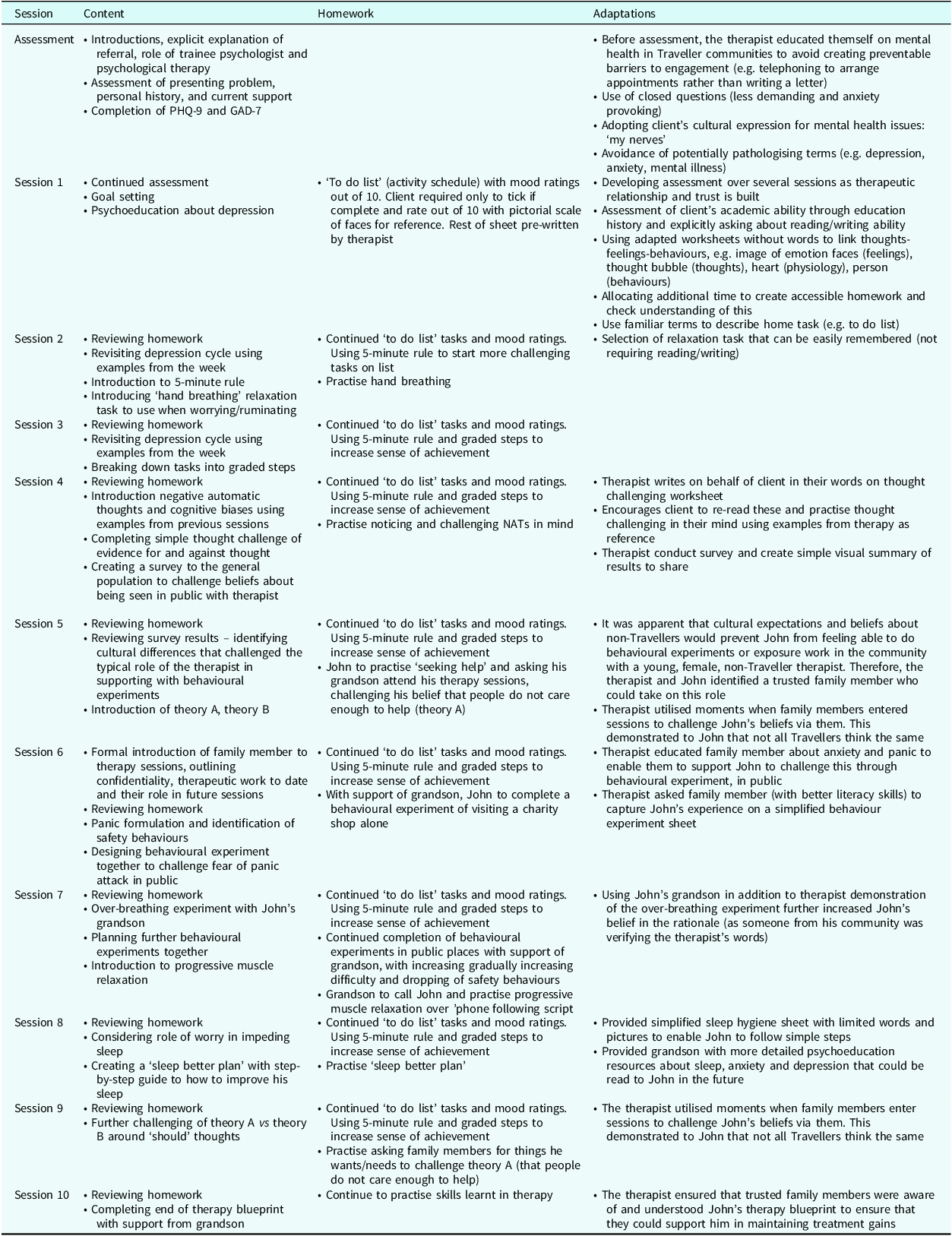

As is common with Irish Travellers (due to factors including racism and marginalisation in the education system and travelling lifestyle; Lloyd and McCluskey, Reference Lloyd and McCluskey2008), John left school at a very young age, with limited literacy skills. His subsequent career in manual labour did not require him to develop these skills further. His reading skills were superior to his writing skills. Previous research has found that lower literacy skills can result in difficulties with engaging in health-related activities such as completing questionnaires and therapeutic homework (Atterbury, 2010). Therefore, careful consideration of how to provide appropriate therapy resources (e.g. thought records, psychoeducation sheets, activity scheduling) was needed to ensure John would feel engaged and not threatened by the process. All worksheets were adapted to be made as simple as possible and didn’t require John to write any words. Wherever possible, pictures and icons were used to represent language, e.g. heart shapes and arrows represented increased heart rate. Behavioural experiment sheets included images in addition to words to act as prompts for tasks set for homework. Extra time was provided in sessions to ensure complete understanding of homework tasks and to review John’s experience of completing homework, troubleshooting difficulties along the way. Once the therapist had built trust with John, they involved a trusted loved one with higher education level to support with consolidation of John’s learning by reading him psychoeducation resources between sessions and relaxation scripts. For a summary of session content and adaptations, see Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of session content, homework and adaptations made

Outcome

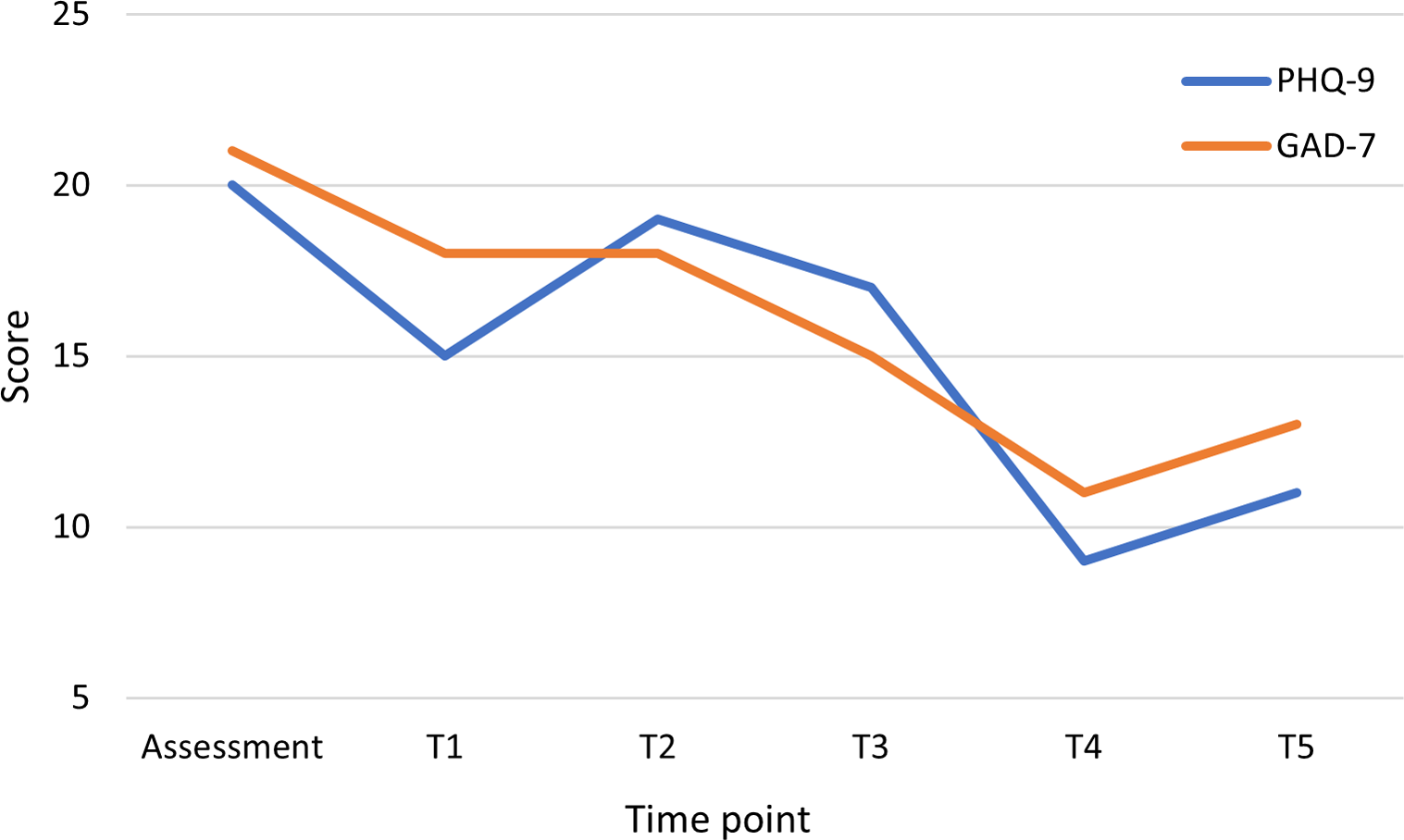

Figure 4 shows John’s scores on the outcome measures throughout therapy. At the start of therapy, he was experiencing severe anxiety and depression. His anxiety scores showed a reduction in symptoms, from severe anxiety to moderate anxiety. John attributed this to being busier and spending less time worrying. His depression scores fluctuated throughout weeks but showed an overall reduction from severe to mild depressive symptoms. The peak at T3 was attributed to being just after Christmas, where John had been alone and spent much time ruminating on his losses. The client and therapist also acknowledged that the remaining depressive symptoms at the end of treatment were likely attributable to unresolved grief that the client chose not to address in therapy.

Figure 4. John’s scores on outcome measures throughout therapy.

In addition to measurable outcomes, John experienced much positive progress in his daily life and met his therapy goals. He re-engaged in rewarding and pleasurable activities that he had completely ceased following Margaret’s death, such as cooking traditional dishes for relatives, going to the shops, using the computer, and cleaning his windows. He reported feeling more comfortable asking for help when he wanted it and feeling more capable to cope on his own. As therapy progressed, John reported trusting the therapist and felt more comfortable to be emotionally vulnerable. Despite not focusing on grief, the client reported that therapy had helped him to finally accept that Margaret had died and that he needed to move forward.

At 4-month follow up, John reported that most of his therapeutic gains had been maintained, he had continued activities that he had restarted and was still using visual image worksheets. His anxiety score had increased but was still within the moderate range. He was offered top-up sessions but reported that he was supported by his family and felt he was coping.

Discussion

This case report demonstrates the successful use of CBT for depression and anxiety in an Irish Traveller client with COPD. It describes how simple CBT techniques can be used effectively for clients with complexities (e.g. physical health co-morbidities, literacy difficulties) if these are considered in a comprehensive formulation (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2004) and appropriate adaptations are made to maximise the possibility of therapeutic gains. Results indicated that this intervention led to positive treatment outcomes for John, including meeting all his therapy goals. However, his continued depressive and anxious symptoms at the end of therapy warrant consideration.

Firstly, the intervention was briefer than the NICE (2009) recommended duration of therapy for severe depression (16–20 sessions). Indeed, John’s difficulties with thought and emotional expression meant that cognitive restructuring occurred towards the end of therapy, where limited time was available to reinforce cognitive changes. Furthermore, due to John experiencing health problems during therapy that caused movement pains, behavioural experiments were not repeated as much as hoped to strengthen changes in beliefs and confidence, which could have contributed to continued anxiety symptoms. John’s outcomes might have improved further with more sessions; therefore, he was offered a follow-up appointment with the trainee’s supervisor to identify any further needs.

Despite the commonality of co-morbidity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in older adults (Beekman et al., Reference Beekman, de Beurs, van Balkom, Deeg, van Dyck and van Tilburg2000), there is limited research to indicate best practices for working with this co-morbidity. NICE (2009) guidelines recommend prioritising the treatment of depression but also treating anxiety if this could lead to an improvement in depressive symptoms. John’s outcomes may have improved if the trainee had focused on depression only, rather than using a transdiagnostic approach to help with panic, given the time-limited treatment and inability to complete either protocol fully. However, some research indicates that a transdiagnostic approach is necessary with older adults, where co–morbidities predict worse functional and psychological outcomes than either disorder alone (Wuthrich and Rapee, Reference Wuthrich and Rapee2013).

This case provides evidence to support Beck et al.’s (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) theory. Increasing positive activity and challenging maladaptive thinking styles indeed led to improvements in John’s thoughts, mood and behaviours. This case also highlighted the importance of adopting a tailored approach to therapy to enhance outcomes, which fully considers clients’ age-related specific needs (Bilbrey et al., Reference Bilbrey, Laidlaw, Cassidy-Eagle, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2022), and the influence of culture on their beliefs (Van Cleemput et al., Reference Van Cleemput, Parry, Thomas, Peters and Cooper2007). The adaptations made to suit this client’s education level and recognise his cultural identity were essential to therapeutic rapport, engagement, and meaningful clinical change.

The authors acknowledge that this research is not generalisable due to the single case study designed. They also note that it is important to consider that the Irish Traveller population, and broader Gypsy, Roma and Traveller population, is diverse in beliefs and practices, and it is essential to avoid homogenising these minoritised groups. However, there is scarce literature exploring mental health interventions for Irish Travellers and these findings could be informative in providing considerations for clinicians working with members of this community. Further research is necessary to identify how best to serve the psychological needs of this population, who are under-represented in clinical services and research.

Key practice points

-

(1) Psychological professionals should use a comprehensive formulation with their clients considering their complete identity, including cultural background, physical health needs, and education level, in addition to addressing their presenting problem.

-

(2) To facilitate good practice when engaging and working with Irish Travellers, healthcare professionals could consider the following factors:

-

(a) Understand beliefs: Take the time to understand their beliefs about mental health and avoid using pathologising language (e.g. depression). Address widely held maladaptive beliefs, such as the notion that individuals must simply ‘get on with’ their mental health difficulties.

-

(b) Assess literacy ability: Assess any challenges related to reading or writing to ensure the accessibility of interventions. Make adaptations if reading or writing challenges emerge (e.g. adapted worksheets).

-

(c) Flexibility with boundaries: Be flexible with boundaries that may create barriers to access, such as the location of appointments, number of appointments, or presence of family members, to accommodate the unique needs of clients.

-

(d) Respect cultural identity: Show respect for their cultural identity and personal boundaries. Acknowledge that clinical services may carry threatening or negative connotations for clients. Approach them with patience, gentleness, curiosity, and a non-judgmental attitude to establish trust effectively.

-

-

(3) While these recommendations provide helpful guidance for healthcare professionals working therapeutically with Irish Travellers, they are based on the insights of a single case study. Therefore, their generalisability to the wider Irish Traveller community (and other Gypsy, Roma and Traveller groups) may be limited, and individualised approaches are necessary to address the diverse needs and experiences within this community.

-

(4) Integrating psychology services into physical health services may improve access for groups such as Irish Travellers who have multi-morbidity to access psychological support.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.M., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank John for his participation in therapy and generosity in sharing his experiences for the benefit of others. We are grateful for the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback and to the charity for Gypsies, Roma and Travellers, whose lived experience perspective enriched the feedback process greatly.

Author contributions

Joanna Mitchell: Conceptualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal); Chris Allen: Conceptualization (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Informed consent to publish this case report was obtained from the client and agreed for this to go forward for publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.