1. IntroductionFootnote 1

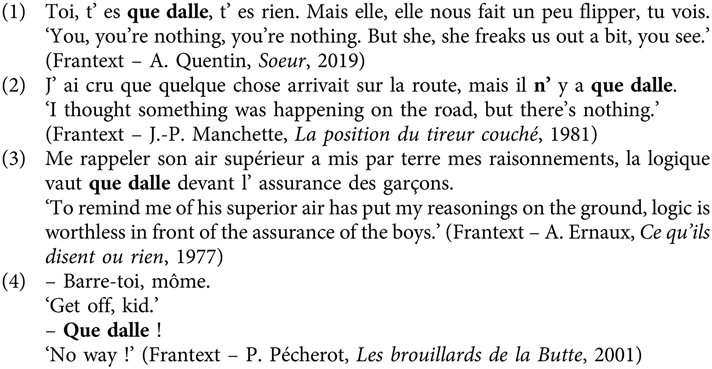

The French expression que dalle, a colloquial synonym of the n(egation)-wordFootnote 2 rien ‘nothing’ (1), offers a wide variety of interesting perspectives. Morphologically, the composition of que dalle is complex in relation to rien since it contains two morphemes: a qu- word followed by a noun. Different que constructions can be distinguished in French, i.a. “que jonctif” (Pusch Reference Pusch2015), “que médiatif” (Anscombre Reference Anscombre2018), but there seems to exist no other que + N constructions in the dictionary (Robert et al. Reference Robert, Rey-Debove and Rey2018) beside some variants of que dalle (i.e. que couic, que fifre, que pouic, que tchi) which we will not discuss further in this article. On the syntactic level, the expression que dalle functions as a negative indefinite pronoun and can occur with (2) or without (3) the preverbal particle ne. It can also appear as a word phrase (4) and represents different but closely related semantisms : a negative pronoun (= rien) in (2)–(3), a refusal (= non) in (4).

On the etymological level, the only level at which que dalle has been described to our knowledge, many hypotheses about its origin have been suggested. The Französisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (von Wartburg Reference von Wartburg1948) links the expression to the word dalle ‘(floor)tile’, which is difficult to explain from a semantic point of view. Others perceive a Breton origin (dall ‘blind’ i.e. seeing nothing, Lebesque Reference Lebesque1970), an Occitan one (coa d’ala ‘the tip of the wing’, i.e. nothing to eat, Vernet Reference Vernet2007), a Lorraine origin (dail ‘joke’, Cellard and Rey Reference Cellard and Rey1991) or a Romani one (dail ‘nothing’, Duneton Reference Duneton2014). For the Petit Robert (Robert et al. Reference Robert, Rey-Debove and Rey2018) que dalle can be traced back to the word daye ‘chorus of song’. Still others (George Reference George1970; Gaston Reference Gaston2016) give a numismatic interpretation to dalle, denoting an ancient Swedish (dahler) or Dutch (daalder) currency. This explanation seems plausible given the existence of a fundamental metaphor that identifies the name of a small coin and the notion ‘little thing, nothing’. Whatever the case, the different hypotheses show that the etymology of que dalle is no longer transparent because of several linguistic and historical influences. The common point of most explanations is that they express a small amount, a negligible or worthless thing. The different perspectives and in particular the role of the element que raise different research questions about the use of que dalle both in synchrony and in diachrony:

-

RQ1: What is the distribution of the different structures?

-

RQ2: To what extent do the structures of que dalle diverge from those of rien?

-

RQ3: How do the different structures evolve in time?

-

RQ4: Can we observe any kind of regular patterns in the development of que dalle which could document a possible lexicalization and/or grammaticalization process?

The article is organized as follows. The next section presents the background literature and the hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the data and the corpus-based methodology. The findings for the different structures of que dalle (RQ1) are described in section 4 while section 5 discusses the main synchronic differences with rien (RQ2). The diachronic analysis in section 6 deals with the specific properties and the semantic-pragmatic development of que dalle (RQ3 and RQ4). In section 7, we address some methodological and theoretical issues in relation to the evolution of que dalle. Finally, conclusions are presented in section 8.

2. Background literature and hypotheses

The literature on que dalle is limited to a few observations. First attested in 1829 and of debated etymological origin (see section 1), que dalle most often occurs with verbs of cognition, such as entraver ‘to understand’ or piger ‘to grasp’(Von Wartburg 1948:XV/2, p. 50; Esnault Reference Esnault1966:221; Cellard and Rey Reference Cellard and Rey1991:263). Muller (Reference Muller1991:54) describes que dalle as being close to standard negation, of which it is a slang variant, particularly suited for dialogue and especially for quantified negation. The absence of an in-depth study on que dalle, both synchronically and diachronically, and its proximity to rien, leads us to analyse the latter first. In this section, we briefly present the different functions of rien, discuss its evolution and end up with some assumptions for the study of que dalle.

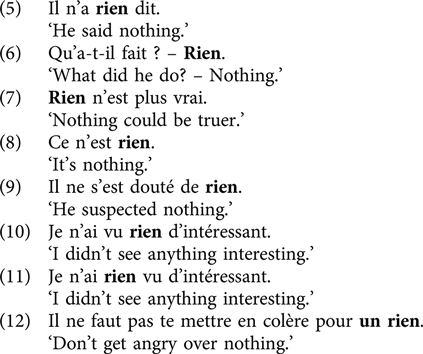

The indefinite pronoun rien belongs, together with personne (‘nobody’), the determiner aucun (‘non’), and the adverbs nulle part (‘nowhere’) and jamais (‘never’), to the class of n-words. All these words semantically combine a negation and an existential quantification but they differ in the domain of quantification, i.e. in their ontological category (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997:21). As such rien indicates zero quantification in the domain of things. Denying the existence of a non-animated referent in a given domain of reference, it has the status of negativeFootnote 3 element either with or without the particle ne (5) and in an autonomous use as word-phrase (6). Depending on its use, this pronoun is deictic, anaphoric or generic (Riegel et al., Reference Riegel, Pellat and Rioul1994:211). Functionally, rien can be direct object (5), subject (7), subject complement (8) or prepositional phrase (9). Rien can be completed by a partitive complement, viz a post-determination by a noun or an adjective (10) introduced by de.

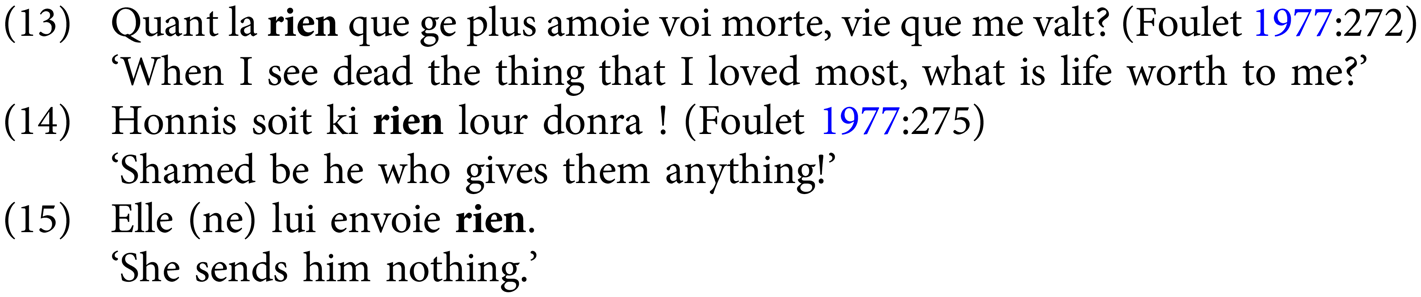

Rien generally follows the placement rules for other indefinite pronouns, i.e. it occupies the place of the noun phrase in the sentence. Sometimes the pronoun rien has a specific behaviour. When the verb is constructed directly, rien is inserted between the auxiliary and the past participle (5). On the other hand, it is placed after the past participle in the case of a prepositional phrase (9). Another peculiarity is that when rien is completed by an adjective, to which it is linked by de, either it remains in its place after the auxiliary (11), or (less frequently) it is placed, with the adjective, after the main verb (10). A final use of rien is as a masculine noun (12). The grammaticalization of rien (from Latin rem accusative of res ‘thing’) into a pronoun is completed in the second half of the 12th century when it has ceased, in subject use, to agree with the feminine which was the gender of the noun rien (Marchello-Nizia et al. Reference Marchello-Nizia, Combettes, Prévost and Scheer2020:719–720).Footnote 4 As several studies have shown (Bréal Reference Bréal1904; Martin Reference Martin1966; Sarré Reference Sarré2003; Martineau and Déprez Reference Martineau and Déprez2004; Labelle and Espinal Reference Labelle and Espinal2014; Hansen Reference Hansen, Marchello-Nizia, Combettes, Prévost and Scheer2020, Larrivée and Kallel Reference Larrivée and Kallel2020; among others), rien initially had a positive value in Old French and has gradually adopted a negative connotation in combination with the particle ne. On the pathway from positive to negative, three variants can be distinguished: rien as a noun (13), as a Negative Polarity ItemFootnote 5 (14), and as an n-word (15).Footnote 6 Unlike NPIs, n-words can be diagnosed by use in fragment answers, constituent negation and double negation readings.Footnote 7 Moreover, they can be used preverbally which is hardly the case for NPIs (Larrivée and Kallel Reference Larrivée and Kallel2020:431).

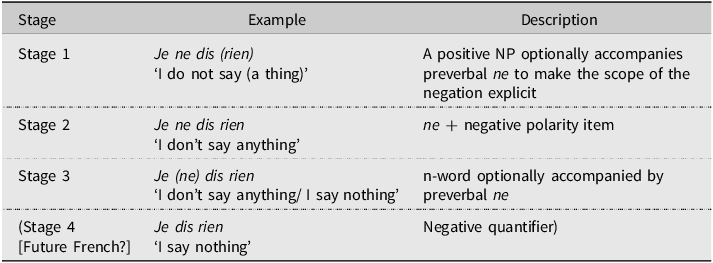

In Contemporary French, rien is essentially an n-word. The masculine noun rien survives in a few expressions and the polarity use, attested until the 19th century, is considered an archaism (Labelle and Espinal Reference Labelle and Espinal2014:216). According to Hansen (Reference Hansen2013), it can be assumed that the evolution of French clause negation with rien, but also other quantifiers (e.g. personne ‘nobody’, jamais ‘never’ …), is largely parallel to the grammatical change observed in the standard negation ne…pas, a process commonly referred to as Jespersen’s Cycle (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1917; Dahl Reference Dahl1979). Table 1 summarizes this cycle for the quantifier rien.

Table 1. The evolution of French clause negation with quantifiers (Hansen Reference Hansen2013:67)

The diachronic sources for the modern quantifiers were, for the most part, originally positive in meaning, like postverbal pas ‘step’, mie ‘crumb’, point ‘dot’Footnote 8 and were used as negation reinforcer in connection with preverbal ne (Stage 1). Over time, the second element of the bipartite negation took on negative polarity uses (Stage 2), and in the end, the original preverbal element becomes optional (Stage 3) or is lost altogether and the postverbal element comes to carry negative meaning on its own (Stage 4). Several studies (Ashby Reference Ashby1981; Coveney Reference Coveney1996; Armstrong and Smith Reference Armstrong and Smith2002; Hansen and Malderez Reference Hansen and Malderez2004; Meisner Reference Meisner2016) have shown that ne-deletion has been steadily increasing and today there is a clear tendency to drop ne in modern spoken French.

Hansen (Reference Hansen2013), however, notes that the suggested cycle is highly simplified because individual quantifiers differ significantly in nature and follow distinct diachronic paths. Indeed, it should already be noticed that there’s an important difference between both: there’s one word for rien, two words for que dalle. This morphological difference between rien and que dalle could have important diachronic consequences, i.e. the development of que dalle may not necessarily proceed like that of rien. With regard to the development of rien, we can observe some common effects of grammaticalizationFootnote 9 (Hopper and Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott2003; Narrog and Heine Reference Narrog and Heine2011; Lehmann Reference Lehmann2015). First, rien loses its original lexical meaning and its meaning becomes functionally dependent on its host constituent, i.e. the development from a positive noun (‘thing’) towards a negative polarity item and n-word (‘nothing’).Footnote 10 Second, there is the loss of morphosyntactic features (decategorialization): the noun grammaticalizing into a pronoun cannot be directly modified by an adjective (10).

In sum, we aim to test the following hypotheses in this study:

-

1. In spite of their different diaphasic distribution, que dalle functions in much the same way as rien.

-

2. Que dalle follows the evolution of the other quantifiers, in particular that of rien as presented in Table 1.

3. Data and methodology

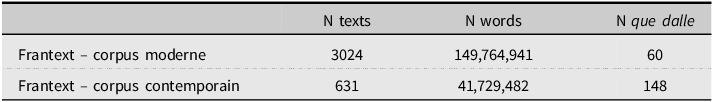

Our data sample is drawn from the electronic literary database Frantext from which we have selected the subcorpus corpus moderne (1800–1979) and the subcorpus corpus contemporain (1980–present). We haven’t found any attestations of que dalle or graphic variants beyond the selected period (see §6). In total, we collected and analysed all 208 observations across the two corpora (Table 2).

Table 2. Frantext corpus sample

In order to compare with rien (§ 5) and to investigate the evolution of que dalle (§6), we will first analyze the syntactic structures into which the expression fits (§4). For that purpose, every case in our corpus sample was annotated in a systematic way for the following variables:

-

1. Structure : dependent ; autonomous (word phrase)

-

2. Ne-deletion: According to several empirical studies (Ashby Reference Ashby1981: 678, Coveney Reference Coveney1996: 76, Hansen and Malderez Reference Hansen and Malderez2004: 23; Meisner Reference Meisner2016:180) ne-deletion is less often present in negative sentences with quantifiers than in standard negative clauses with pas, and the different quantifiers do not all appear to favour ne-deletion to the same extent. With regard to the exceptive structure ne…que (‘only’), the proportion of ne attested in spoken language is 35 to 40% (Blanche-Benveniste et al. Reference Blanche-Benveniste, Bilger, Rouget, Mertens and Willems1990:189).

-

3. Lexical verb type : According to Esnault (Reference Esnault1966:221) and Cellard and Rey (Reference Cellard and Rey1991: 263), the expression que dalle is frequent with il y a (‘there is/are’), valoir ‘to be worth’, cognition verbs (comprendre ‘to understand’; entraver, piger ‘to get’), and verbs of perception (voir ‘to see’ ; entendre ‘to hear’ or their equivalents).

Since the Frantext data serves in the first place to map out the diachronic evolution of que dalle, it seems useful to supplement it with online data in order to capture the latest trends. As such, the Frantext dataset will be completed with data from the French Ten Ten Corpus (15683 que dalle tokens) but the latter is not quantified in a systematic way. The French Ten Ten Corpus, version 2.0. [2012] (Kilgarriff et al. Reference Kilgarriff, Baisa, Bušta, Jakubíček, Kovář, Michelfeit, Rychlý and Suchomel2014), is a web corpus searchable through the Sketch Engine interface and includes a wide range of web data: journalistic texts, Wikipedia, forums, etc. The total number of words amounts to almost ten billion.

4. Analysis of que dalle

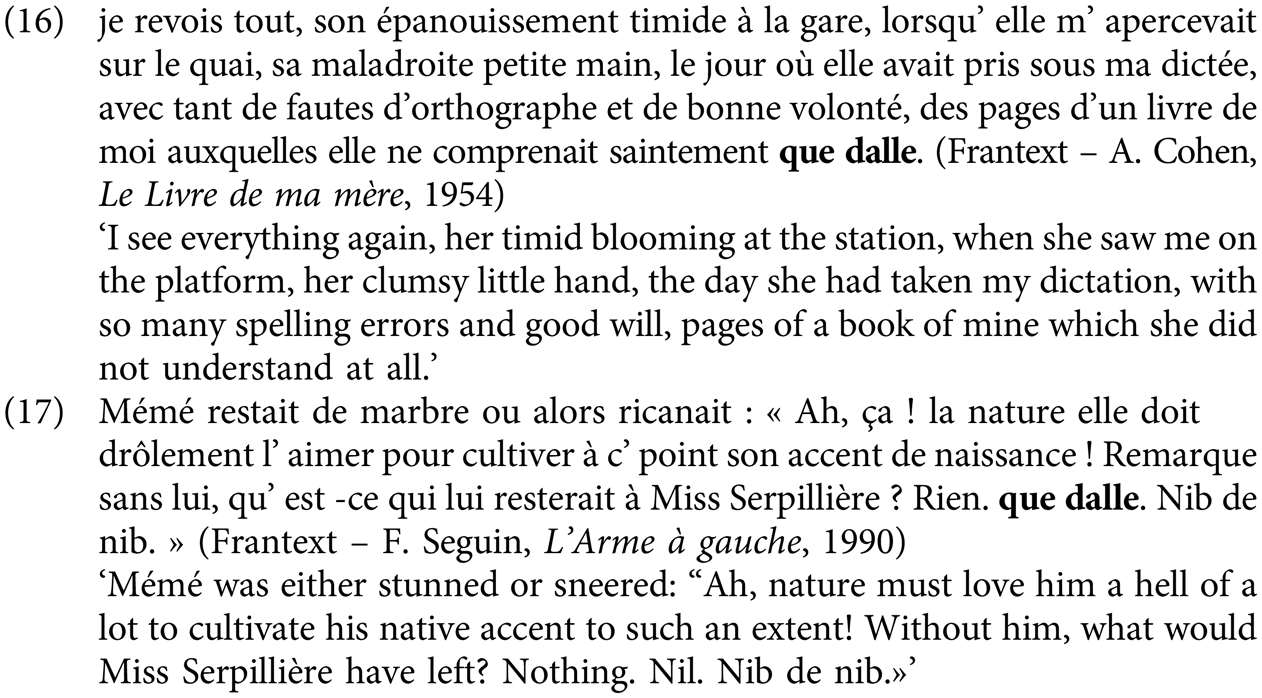

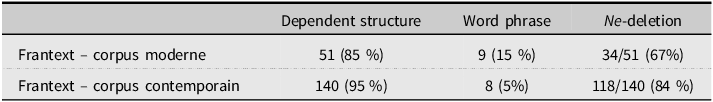

Table 3 shows that que dalle predominantly occurs in the dependent structure where it can be direct object (16) and subject albeit always in a repeated sequence (17).

Table 3. Distribution of the different structures with que dalle

Que dalle can also be used in a prepositional phrase (18), as subject complement (19) and can be post-determinated by a PP (19).Footnote 11 In contrast with rien, it functions also as an attributive adjective (20). Limited to the French Ten Ten Corpus corpus, and even there very rare, N= 12 out of 15683 que dalle tokens, it can also take the form of a masculine noun in un gros que dalle (21).

The meaning usually is that of a negation, i.e. a lack of quantity, nothing. Often, the shift from positive to zero quantification is emphasized by (ne)… plus (‘more’), like in (22). The French Ten Ten Corpus supplies also a few observations where the meaning of que dalle is close to the standard negation ne…pas (‘not’) (23). Que dalle can also appear in a double negation context (24).

The meaning is less transparent in elliptical constructions (25) or when que dalle is detached (26). The example (25) could be misleading at first sight, but que dalle is always non-animated, in (25) it means ‘nothing, no answer’. In (26), the meaning is closer to the pragmatic meaning of the word phrase structure, e.g. a refusal.

The word phrase structure (27) is already present in the corpus moderne but the frequency remains limited throughout both corpora (Table 3). When used in a separate utterance, or used prosodically independently from the rest of the sentence as in (26), que dalle behaves like a pragmatic marker as defined by Brinton (Reference Brinton2017:9). As pragmatic marker, que dalle does not have a textual usage but highlights instead the interpersonal connection and is polysemic: indignation/insultFootnote 12 (27), difference of opinion using negation in the sense of non! or pas du tout! (28),Footnote 13 but also zero quantification (= ‘nothing at all’) (29) as in the dependent structure.

Regarding the ne-deletion variable, we can keep it very short: ne-deletion is already present in the corpus moderne (67%) and today a clear tendency to drop ne can indeed be established (84% in corpus contemporain).

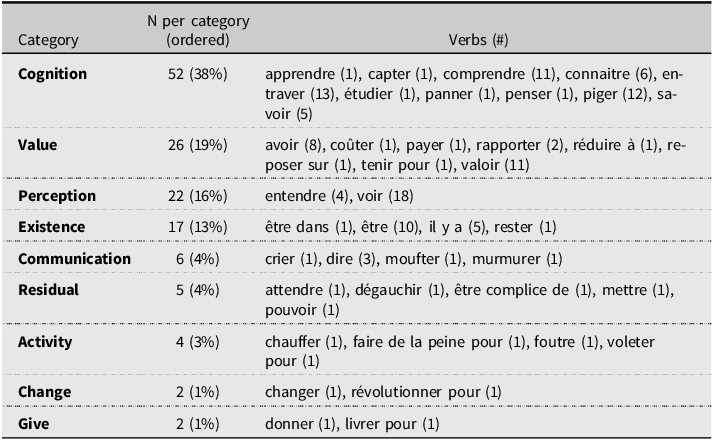

Finally, the analysis of the lexical verb confirms that the expression que dalle is particularly frequent with cognition verbs, value verbs, verbs of perception and existence (Esnault Reference Esnault1966:221; Cellard and Rey Reference Cellard and Rey1991:263). Table 4 presents the complete listFootnote 14 of verbs with que dalle, grouped by lexical field. The residual category contains verbs that occur only once and could not be placed anywhere else. The analysis nevertheless shows that the paradigm of the lexical verb is much richer and cannot be limited to the verbs expressing the forementioned categories. Verbs belonging to other lexical fields, i.e. Communication, Activity, Change, Give can also cooccur with que dalle.

Table 4 : Verb categories cooccurring with que dalle

5. Comparison between que dalle and rien

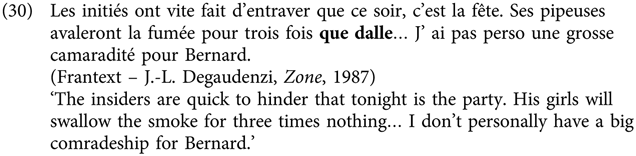

Now that we have described the different structures of que dalle we can examine in more detail the possible substitutions and combinations compared to rien. On the paradigmatic axis, we note that que dalle can replace rien in most distributional contexts, even in the most idiomatic ones like in (30). In the expression trois fois rien/ que dalle, nothing becomes something you can buy at a low price.

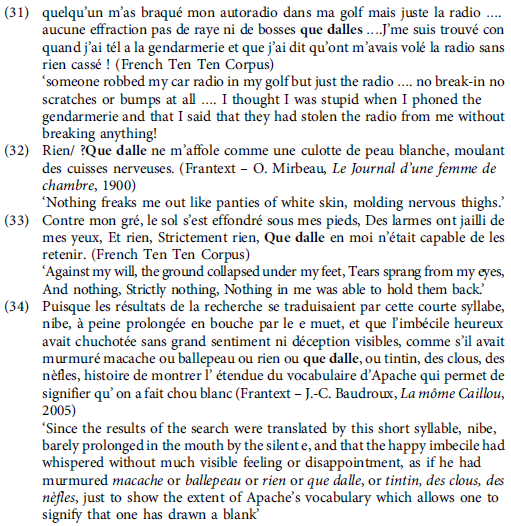

On the syntagmatic axis, we observe that unlike rien, que dalle can function as an adjective (31). As a subject, it cannot occur in sentence-initial position (32) and appears always in a repeated sequence with synonyms (33). Multiple synonyms, also in object NPs, can cooccur with que dalle: rien, nib, nib de nib (17), zéro, foutu, macache, walou, nada, papate, schnoll, que couic, que fifre, que nenni, que pouic, que tchi, peau de balle among others (34)Footnote 15 . Reduplication is typical of oral discourse and reinforces the intended meaning of zero quantification.

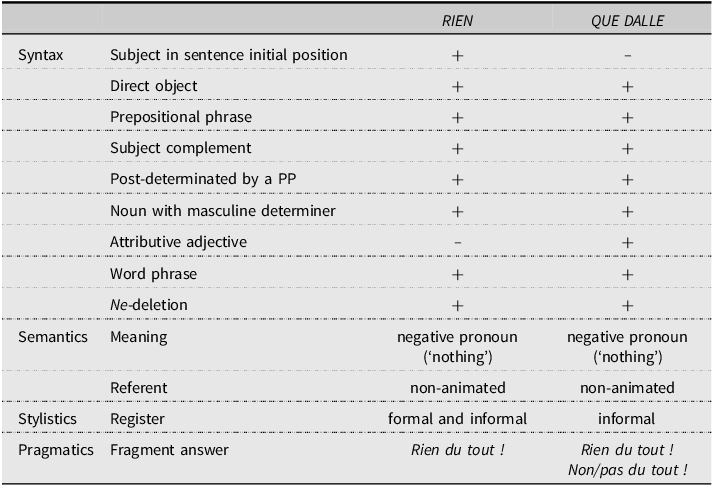

Semantically, que dalle denotes a strong sense of zero quantification. As a pragmatic marker, que dalle is used in vernacular language for emphasis conveying a sense of informality and making the speaker’s tone more conversational or expressive. As such, it often carries a connotation of indignation (27), refusal, or emphasis of zero quantification (29). Rien can also relate to this but not to negation in terms of ‘non/ pas du tout!’ as que dalle does in (28). Table 5 summarizes the functions of rien versus que dalle in modern French. A lot of functions agree, but que dalle differs from rien in terms of syntax (subject position, attributive adjective), stylistics and pragmatics.

Table 5. Functions of rien vs. que dalle

6. The evolution of que dalle

Our analysis has shown so far that there is a clear functional convergence between que dalle and rien but there exist also some substantial differences between both. Before analysing the evolution of que dalle, we discuss some important observations in what follows.

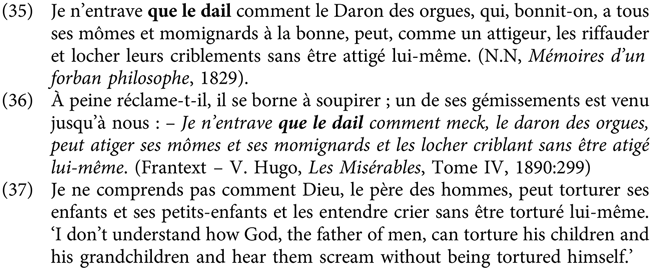

A first observation is that the earliest attestation of que dalle is a fairly recent phenomenon. According to Esnault (Reference Esnault1966:221), the expression que dalle is derived from que le dail of which the first attestation dates from 1829 (35). Coincidentally, the first example in the Frantext dataset is the same (36)Footnote 16 since Victor Hugo integrates this first attestation in Les Misérables six decades later. V. Hugo himself supplies the translation of the direct speech/argot part in standard French in note on the same page (37). Note that que le dail is already translated as a standard negation (ne…pas). We haven’t found any attestation with bare noun dail in our corpus.

Unlike the expression rien which goes back to the old French period, it seems that the first attestation of the form que dalle does not take place until the 20th century.Footnote 17 Although some works already mention the form (Feist Reference Feist1916:109; Leroy Reference Leroy1922:65), the first attestation in Frantext only dates from 1942. In Table 2, we see that the ratio in the contemporary corpus is very different to that of the modern corpus. The frequency of que dalle has considerably increased and it is nowadays a common informal n-word for which we can currently find numerous spellings on the internet: que dal, que dale, quedalle, quedal, queud, queude, qu’dalle, keud, keude, keudalle, kedal, dalle, dal.

A second point concerns the origin of the element que. It seems obvious that que dalle originates in the exceptiveFootnote 18 structure ne…que (‘only’), exemplified in (38). In this structure, the element que can introduce different post-verbal constituents, i.e. object, subject complement, PP, sequence of a presentative construction, and sequence of an impersonal construction (Riegel et al. Reference Riegel, Pellat and Rioul1994:413). Semantically, the exceptive combines a positive meaning made possible by the conjunction que (equivalent to uniquement ‘except’) and a negative meaning carried by the element ne. Footnote 19

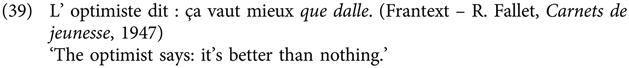

However, the corpus lacks examples indicating a first phase with dalle and an exceptive structure. In (39), the element que is functional but for another reason.

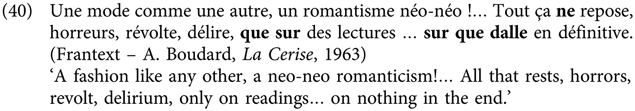

In theory, the structure should be *ça vaut mieux que que dalle with the first que as functional part of the comparative mieux que ‘better than’ and the second as the empty que of lexicalized que dalle. However, this structure is ungrammatical and we note that they both have fused into one que, probably for reasons of economy or euphony. Today, the que element in que dalle has completely lost its grammatical function as part of an exceptive structure. The contrast between the ne…que structure and que dalle is reflected in (40). It has been widely assumed in the literature (e.g. Gross Reference Gross1977:90; Gaatone Reference Gaatone1999:106) that exceptive que can never follow a preposition (ne…*prep. que + NP) unlike the structure with que dalle which forms a lexicalized entity.

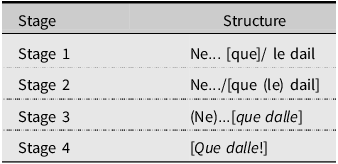

If, for the time being, we nevertheless retain the hypothesis that que dalle originates in the exceptive structure, how do we get from a ne…que dalle with exceptive meaning to ne…que dalle as n-word? Based on Table 1, i.e. the evolution of French clause negation with quantifiers (Hansen, Reference Hansen2013:67), the development of que dalle would follow a similar pathway (Table 6) where the element que is an exceptive conjunction in the beginning: ne…que le dail. Through reanalysis the element que is no longer associated to the preverbal particle ne, but to the noun that follows. The meaning evolves from positive (restriction) to negative (‘nothing’).

Table 6. The evolution of que dalle

The application of Table 1 presented in Table 6 looks pretty artificial because of the focus on form rather than on meaning. With a focus on meaning, the evolution of the expression que dalle can be refined as follows:

-

1. The exceptive meaning (ne.que) is accompanied by a positive NP with determiner (le dail) designating a small quantity or insignificant thing.

-

2. Reanalysis of que which agglutinates to the noun that follows and loses its autonomous function and its meaning.

-

3. Lexicalization of que with the bare modified noun dalle into que dalle. At the same time, the entire structure que dalle is recategorized as an indefinite pronoun with a negative meaning (‘nothing’). The status is now this of an n-word which is optionally accompanied by preverbal ne.

-

4. Autonomous use of que dalle as pragmatic marker in the sense of ‘no, nothing at all’.

A first process of language change to be discussed is lexicalization, i.e. the process of adding new words or word patterns to the language’s lexicon as a result of various mechanisms, such as borrowing, compounding, abbreviation, blending, or conventionalization of phrases (Brinton and Traugott Reference Brinton and Traugott2005). The lexical structure dalle, belonging to the major category of nouns and having a general, almost generic (see introduction) semantics is predisposed to language change. As a matter of fact, the que loses its functional exceptive value and merges with the bare noun dalle to form the lexicalized expression que dalle. Lexicalized elements beginning with que are very rare in French and, to our knowledge, limited to a number of other colloquial expressions as que couic, que fifre, que pouic, Footnote 20 and que tchi. The expression que dalle is used from the start in rather conventionalized sequences with a reduced number of verb types, e.g. cognitive verbs (comprendre, entraver, piger, etc.).Footnote 21

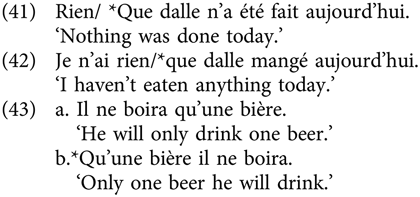

A second parallel process of language change is that of grammaticalization, i.e. the process of developing new grammatical elements or functions from existing words or phrases. It usually involves a shift from a more concrete and lexical meaning to a more abstract and grammatical one, as well as a reduction in form and autonomy. In this particular case, the bare noun dalle has lost its morphosyntactic features and is, together with que, grammaticalized into the pronoun que dalle. The desemanticization consists of the change from its original lexical meaning, i.e. a small quantity, to ‘nothing (at all)’. This process usually occurs with erosion, i.e. the loss of phonological substance. We can currently find several spellings on the internet which shows that the erosion is still continuing. The original preverbal element becomes optional (84% of ne-deletion in corpus contemporain) because its status is that of an agreement marker. The number of verb categories involved increases and other lexical fields like Change and Give are integrated into the paradigm. Based on the diachronic Frantext dataset we cannot state that the evolution of que dalle is identical to that of rien: (i) que dalle can be used as an adjective, e.g. (20); (ii) que dalle cannot be used as a noun. However, today’s TenTenCorpus might be indicative of a changing situation since there are already some attested instances of que dalle as a masculine noun, e.g. (21); (iii) as subject, que dalle only occurs in a post-verbal position, more precisely in a repetition, e.g. (17). As such, the absence of preverbal use could indicate that que dalle is less advanced on the path to becoming a negative word, as is the case for NPIs (Larrivée and Kallel Reference Larrivée and Kallel2020). Note that the positional difference between rien and que dalle is observed not only in sentence-initial position (41) but also in intermediate position (42). We argue that the limited syntactic mobility of que dalle is due to its lesser degree of grammaticalization. However, alternative explanations cannot be ruled out. The fact that que dalle cannot move to the sentence-initial position might also be explained by its historical origin in the exceptive structure (43), as the que must remain under the scope of sentential negation.Footnote 22 Finally, the mobility deficit could simply be a matter of the weight or length of the lexical unit que dalle, since French syntax generally disallows longer expressions from being inserted between the auxiliary and the participle.

Due to its grammaticalization, the frequency of que dalle is increasing, and its distribution is expanding to new contexts. As such the use of que dalle in contemporary discourse align with several features commonly attributed to pragmatic markers as outlined by Brinton (Reference Brinton2017:9). Syntactically, que dalle often operates outside the main syntactic structure, as in fragment answers or exclamations (Stage 4). Functionally, que dalle can be defined as multifunctional, i.e. it serves various pragmatic purposes. The pragmatic marker undergoes subjectificationFootnote 23 which leads to other more expressive meanings e.g. refusal, indignation. Detges and Waltereit (Reference Detges and Waltereit2002:178) suggest that the change from a noun denoting a small quantity functioning as a Negative Polarity Item to a marker of emphatic negation must have taken place in contexts such as “critical statements and accusations that the speaker has to counteract”, like it is the case in (27). Finally, que dalle also exhibits sociolinguistic and stylistic features associated with pragmatic markers (Brinton Reference Brinton2017:9). It is characteristic of spoken French and is rarely encountered in formal written texts, except when used for stylistic effect in dialogue, as seen in the Frantext corpus. The expression is salient in informal oral and online conversations (e.g., the TenTen Corpus), where its emphatic tone and colloquial flavour are especially prominent. Whether its use is age- or gender-specific remains to be investigated.

7. Discussion

The evolution of que dalle as outlined above is definitely a hypothetical one that involves a number of methodological and theoretical issues that warrant discussion. First, a methodological limitation is that there exists no evidence for stages 1 and 2 in the Frantext corpus. Perhaps it is possible that the first stages still took place in the oral register and that there is therefore no written proof at all. At the moment there is no certainty about that. Second, it turns out not to be a gradual process from start to finish, at least that is what we observe in our diachronic corpus. While we would expect stage 4 only after a period of conventionalization, it appears simultaneously with stage 3 in the corpus moderne (Table 3). We could hypothesize that the actualization process of que dalle as a pragmatic marker is ongoing and that would confirm the assumption that changes are always manifested in synchronic variation (i.e. in gradienceFootnote 24 ). However, the analysis is complicated by the fact that both structures arise at the same time and that the pragmatic marker is on the decrease in the Frantext corpus (Table 3). A reviewer rightly notes that the simultaneity observed in literary material does not necessarily reflect the occurrence of events in spoken language. Consequently, more data from other corpora is needed to further investigate the intersection between synchronic and diachronic variation. Third, on a theoretical level and in relation with typology, we know that indefinite pronouns can arise from different kinds of source constructions (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997; Breitbarth et al. Reference Breitbarth, Lucas and Willis2020). Many languages use generic nouns like ‘person’, ‘thing’, ‘place’, ‘time’, etc. to express notions like ‘someone’, ‘something’, ‘somewhere’, ‘sometime’, etc. and the diachronic process by which a generic noun is turned into an indefinite pronoun is quite straightforward. However, the evolution of an indefinite pronoun out of a noun with generic properties (defining a small quantity) in combination with an exceptive expression is a special phenomenon. We have seen (section 2) that rien evolves from polarity item to n-word. In a similar way and with respect to the exceptive expression ne…que, we hypothesize that dalle was initially an NPI which, in combination with que, formed the n-word que dalle, and now independently conveys negative meaning. As an n-word, que dalle corresponds to all the micro-steps defined by Larrivée (Reference Larrivée2021): que dalle functions in fragment answers (29), can be used in double negation (24), and in constituent negation contexts (18). The absence of preverbal use might be explained by the possibility that que dalle remains connected to its NPI origin. In his 2011 paper, Larrivée challenges the existence of a Jespersen’s cycle, arguing that most of the items in question do not follow a systematic syntactic evolution through successive stages leading back to an original non-negative state. Instead, these items transition along a continuum of ordered functions and possibly environments. This, he suggests, explains why individual items can combine multiple functions and why the back-formation of negative polarity functions is possible.

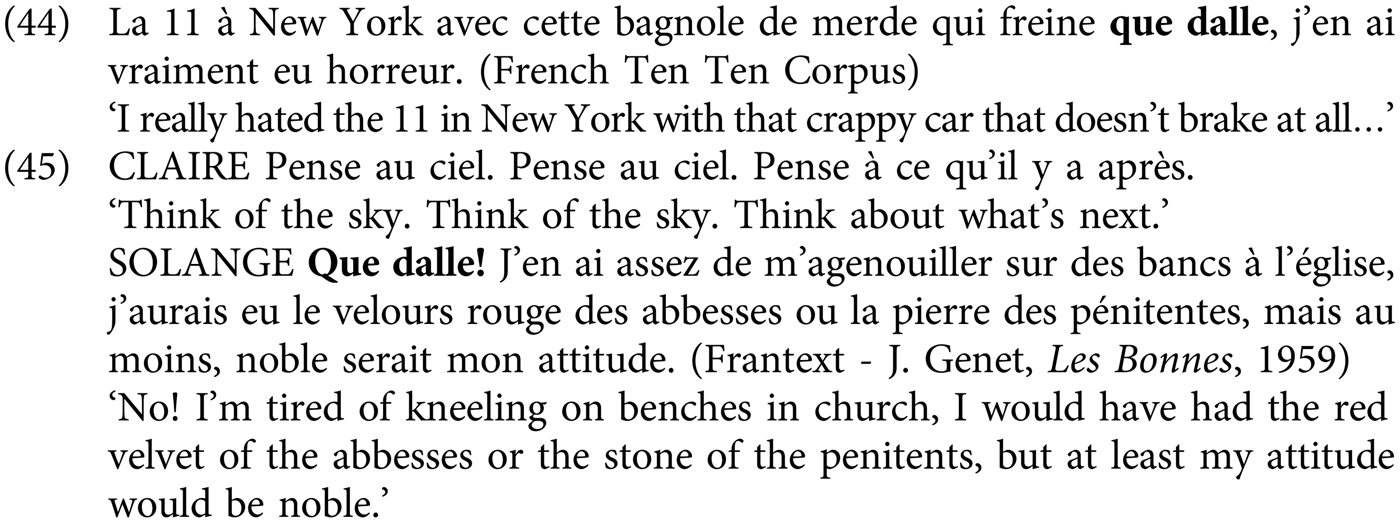

Finally, there is no doubt that the development of que dalle is different from that of rien in that it tends towards inherent negativity in fragment answers. Like rien, que dalle can be interpreted as a standard negation, meaning ne…pas, in a non-argumental use, e.g. example (23) repeated here in (44).Footnote 25 However, in contrast to rien, que dalle can also function as an adverb of negation in fragment answers, meaning non! or pas du tout!, e.g. examples (4), (28), and (45). This emphatic negation appears to represent an extension of its pragmatic use.

8. Conclusion

The present study constitutes a first contribution to the understanding of the French pronoun que dalle (‘nothing’). First, we looked at its syntactic flexibility, its semantic strength in conveying zero quantification, and its pragmatic role in informal language. Then we compared que dalle with its near synonym rien and analysed its development. The results can be summarized as follows. On a descriptive level, we can conclude that, in spite of their different diaphasic distribution, que dalle functions in much the same way as rien, but the former differs from the latter in terms of syntax (subject position, attributive adjective), stylistics and especially pragmatics. On a methodological level, we hypothesized that que dalle originates in the exceptive structure ne…que (‘only’) but the corpus data were insufficient to demonstrate this assumption. On a theoretical level, different processes, i.e. lexicalization and grammaticalization, could be distinguished. We acknowledge that individual quantifiers can be very different in nature and have different diachronic paths: the development of que dalle differs from that of rien in its postverbal use, and it tends toward inherent negativity in fragment answers. We can generally conclude that the past end of its evolution is still loose and in need of further investigation, whereas the current end is quite neat with already several differences in comparison to the path of its near synonym rien.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.