Introduction

The Palestinian Tourism and Antiquities Police have played a crucial role in combating the looting and illegal trade of cultural heritage since the establishment of the Palestinian Authority. Tasked with protecting archaeological sites and historical artifacts, the force has focused on preventing illicit excavation, theft, and smuggling of antiquities. Their efforts extend to the protection of museums and archives, ensuring the proper management and conservation of historical materials. Through increased enforcement and public awareness, the Palestinian Tourism and Antiquities Police continue to be a vital force in safeguarding the nation’s archaeological treasures (DTAP Archive 2024).

Antiquities in the Middle East face numerous threats to their preservation due to various conflicts and instability. These challenges have contributed to the emergence of individuals involved in smuggling, theft, and forgery of antiquities for commercial and other purposes.

The forgery of manuscripts in the Middle East presents significant challenges to cultural heritage preservation, as fabricated documents often circulate for economic gain, complicating efforts to safeguard authentic artifacts. Manuscripts in the region hold deep historical, cultural, and religious significance, encompassing centuries-old religious texts, legal documents, and historical accounts written in Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew.

Many of these manuscripts are kept in private collections or institutions abroad, complicating efforts to catalog and protect them. Economic hardship, along with high demand from collectors, tourists, and museums, further fuels the black-market trade in forged manuscripts.

These forgeries are often crafted using traditional materials and techniques to imitate age and authenticity, sometimes incorporating fabricated historical details to increase their appeal. Commonly forged manuscripts include religious texts, land deeds, and personal letters, often altered with misleading dates, locations, or attributions.

The authentication of manuscripts is hampered by limited resources and restricted access to specialized equipment, enabling forgeries to circulate undetected. Although international collaborations with universities and museums have provided support through training and authentication resources, these efforts remain constrained by funding and logistical challenges.

The preservation and authentication of historical manuscripts is vital to understanding the cultural and historical heritage. However, the rise of forgeries poses significant challenges to scholars and heritage professionals working in the region. Among the many types of historical documents, leather-bound manuscripts, often seen as symbols of cultural identity, are particularly vulnerable to forgery. These manuscripts, when not properly authenticated, can distort historical narratives and mislead researchers about the past.

In response to this growing issue, scientific methods such as radiocarbon dating have become crucial tools in verifying the authenticity of ancient texts, including leather manuscripts. Radiocarbon dating, which measures the decay of carbon isotopes in organic materials, provides a reliable means of determining the age of a manuscript. However, when applied to forged manuscripts, especially those created using modern techniques or treated materials, this method faces significant challenges.

Forged manuscripts may contain contaminants, altered materials, or synthetic compounds that complicate the radiocarbon dating process. Additionally, variations in the tanning processes used in ancient leather preparation and modern forgeries may result in anomalous radiocarbon dates that require careful interpretation.

This research seeks to explore the specific challenges and limitations of applying radiocarbon dating to forged leather manuscripts from Palestine (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The leather manuscript, with color enhanced to show detail. (Courtesy of Hasan Jamal, Palestinian Tourism Police Department.)

Inscription reading

The transcription of the manuscript presents considerable challenges due to the falsification of its letters. The phrase ‘l ‘l, commonly found on sarcophagi as an absolute negation (“no no”), suggests an intention to replicate authentic texts of this type. However, closer examination reveals that the letters lack the authenticity of genuine Phoenician or Paleo-Hebrew inscriptions. Further analysis indicates that the letters were likely inscribed with a modern marker rather than traditional ancient tools, strongly pointing to a deliberate act of forgery (Figure 1).

The inclusion of symbols such as the Menorah and Shofar—distinctive elements of Jewish iconography—further highlights the artifact’s inconsistencies. This blending of cultural motifs, which is atypical and historically implausible for Phoenician or Hebrew texts of antiquity, strongly supports the conclusion that the manuscript is not authentic.

While attempting a full transcription is not possible due to the poor quality of the letters in the photographs, many characters appear unclear or completely erased. Additionally, a line may be missing at the end, though this is not visible in the available images. The repeated occurrence of ‘l ‘l—used as an absolute negation to discourage the opening of tombs or sarcophagi—is consistent with known inscriptions of this kind but does not validate the artifact’s authenticity.

It is evident that the script is neither Phoenician nor Paleo-Hebrew. In our evaluation, the manuscript is a crude forgery. The writing appears to have been executed with a modern marker on aged leather, rather than with traditional tools such as a pen or quill.

The forgery attempts to mimic ancient Phoenician letters from the 10th century BCE while incorporating elements from the 6th century BCE. However, the execution is rudimentary, and the inconsistencies are striking. This artifact stands as a clear example of an unsophisticated attempt to produce a counterfeit manuscript.

This Phoenician inscription is somewhat fragmented and contains some errors (as noted in Line 5). However, the author will attempt a reasonable translation based on the structure and known vocabulary:

Line-by-line translation:

-

1. ´l ´y/wg gpn ´l ḥrb → “To [the god] (Ay/Ywg?), the vineyard, to war”

-

2. dhb ´l ṭrd´ wbyr → “Gold to [the god] (ṭrd?) and bronze”

-

3. dh ´l ´ ´z → “This [is] for the mighty [god]”

-

4. d ´l m‘bd → “This [is] for the temple”

-

5. ´ly w´ ´ḥdr → “[—] and [—] the sanctuary” (Aleph letters noted as incorrect)

-

6. ´l ´l mpd rb´n → “To the god of the great temple”

-

7. mt ´sndm → “The deceased [person] (Sndm)”

-

8. dnz whdys → “Dnz and Hdis” (possibly names)

-

9. b‘d pm´l → “After the work/ritual”

Interpretation

The inscription appears to be a dedicatory text, possibly related to a temple offering or commemoration. It mentions a god, a temple, offerings of gold and bronze, and possibly a deceased individual. The names “Dnz” and “Hdis” might refer to donors or important figures related to the dedication.

AMS 14C dating analysis

The sample was submitted to the ISOTOPECH ZRT laboratory in Debrecen, Hungary for AMS radiocarbon analysis. It was given the lab code DeA-42822, sample number I/3380/1, and has been subject to their AMS 14C dating techniques (Major et al., Reference Major, Dani, Kiss, Melis, Patay, Szabó, Hubay, Túri, Futó, Huszánk, Jull and Molnár2019a, Reference Major, Futó, Dani, Cserpák-Laczi, Gasparik, Jull and Molnár2019b; Molnar et al. Reference Molnár, Janovics, Major, Orsovszki, Gönczi, Veres, Leonard, Castle, Lange, Wacker, Hajdas and Jull2013a, Reference Molnár, Rinyu, Veres, Seiler, Wacker and Synal2013b).

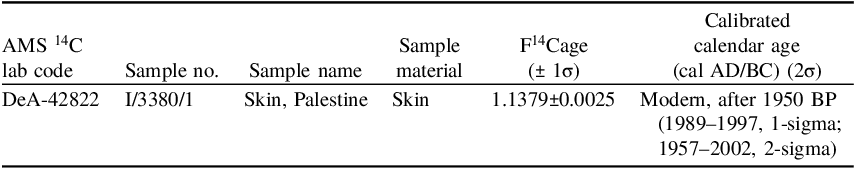

The 14C analysis results showed a conventional 14C age of 1.1379±0.0025BP, corresponding to a calibrated calendar date post-1950 (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1. Age range results summary of leather sample analysis.

Figure 2. Calibration of radiocarbon result obtained on sample from the manuscript.

Discussion and conclusion

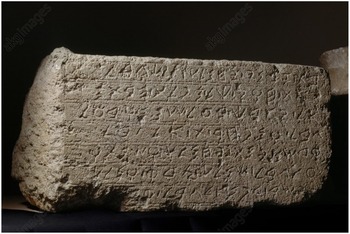

The manuscript is written in what appears to mimic ancient Phoenician script, resembling the style of the Yehimilk inscription (10th–9th centuries BCE). The Yehimilk inscription, a well-known Phoenician artifact (KAI 4 or TSSI III 6), was first published in 1930 and is currently housed in the museum of Byblos Castle (Figure 3). It was documented in Maurice Dunand’s Fouilles de Byblos (Dunand Reference Dunand1937–1939) as well as in other publications (Albright Reference Albright1947; Bonnet Reference Bonnet1993; Mazar Reference Mazar1986; Rollston Reference Rollston2008).

Figure 3. Yehimilk Phoenician inscription in the Byblos Castle Museum. (Courtesy of Philippe Maillard/akg-images.)

The results of radiocarbon analysis, combined with the stylistic and textual analysis, indicates that the manuscript is a modern forgery. As stated above, the combination of pagan Phoenician text with Jewish religious symbols is anachronistic and culturally inconsistent, as these traditions belong to distinct and unrelated historical contexts. Moreover, the text contains numerous grammatical errors, further discrediting its authenticity.

The content of the manuscript suggests it contains curse texts, possibly intended to enhance its perceived historical and ritualistic significance. The forgery was likely created for financial gain, targeting collectors or the antiquities market. These findings underline the complexity and motivations behind such forgeries and highlights the importance of scientific methods in uncovering the truth behind antiquities.