Introduction

Many people wear what Kolinsky and Morais (Reference Kolinsky and Morais2018) call “literate glasses”: they are so accustomed to being able to read and write that they cannot imagine what it is like not to be able to do so. Yet, literacy positively impacts a variety of individual and societal outcomes from labor market participation to self-reported health and several other domains (OECD, 2025). Being literate has many implications for human cognition too, also beyond the mere ability to process written text. Research on the cognitive implications of literacy has consistently shown that learning to read and write positively affects verbal working memory skills (Demoulin & Kolinsky, Reference Demoulin and Kolinsky2016; Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Zafiri and Politimou2011), and literacy likely also allows people to develop awareness of a wide variety of linguistic structures (Homer, Reference Homer, Olsen and Torrance2009; Kurvers et al., Reference Kurvers, van Hout, Vallen, van de Craats, Kurvers and Young-Scholten2006). Several studies support what we might call the literacy hypothesis: verbal working memory and meta-linguistic awareness improve because of the development of reading and writing skills (Demoulin & Kolinsky, Reference Demoulin and Kolinsky2016; Huettig & Mishra, Reference Huettig and Mishra2014; Kolinsky & Morais, Reference Kolinsky and Morais2018). Becoming literate changes people’s linguistic representations and, as a result, their auditory language processing (Nation & Hulme, Reference Nation and Hulme2011; Rosenthal & Ehri, Reference Rosenthal and Ehri2008). Studies on adult emergent readers, who have not learned to read and write at a young age, support the idea that becoming literate has a fundamental impact on someone’s cognitive abilities (e.g., Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Zafiri and Politimou2011; Kurvers et al., Reference Kurvers, van Hout, Vallen, van de Craats, Kurvers and Young-Scholten2006; Morais et al., Reference Morais, Cary, Alegria and Bertelson1979).

Sometimes, becoming literate might coincide with learning a new language. While there is substantial evidence that becoming literate has an impact on general cognition, it is relatively unclear what effect being able to read and write has on learning a new language. There is likely some effect of becoming literate when acquiring a second or additional language, so the question is rather what the nature of this effect is exactly. In this study, we try to tease apart two possible ways through which literacy could affect second-language acquisition: a restructuring effect and a modality effect (see, for a comparable distinction, for example, Demoulin & Kolinsky, Reference Demoulin and Kolinsky2016). The restructuring effect entails that becoming literate leads to altered linguistic representations, which influences how emergent readers learn a new language. The modality effect implies that literacy offers an additional input modality for the target language, which may accelerate the language learning process. In the remainder of the text, we will first discuss each of these effects, which are not mutually exclusive and can co-occur, in more detail. Next, we describe our word learning experiment in which we test second-language learners who vary in their degree of literacy in their first and second languages. In the experiment, half of the participants received only auditory input to learn the words, whereas the other half was aided by written input. Using this setup, we could get a better idea of when and how the restructuring and modality effects play a role in the second-language acquisition process.

Restructuring, meta-linguistic awareness, and SLA

Since most of our knowledge about second-language acquisition comes from studies with highly educated participants who do not vary much in their literacy skills (Andringa & Godfroid, Reference Andringa and Godfroid2020), most of our theoretical knowledge about the effect of literacy on linguistic representation comes from the child language literature. For example, the Lexical Restructuring Hypothesis argues that as the child’s lexicon grows, their lexical representations are updated with additional information about the linguistic structure of the words (Metsala & Walley, Reference Metsala, Walley, Metsala and Ehri1998; Krenca et al., Reference Krenca, Segers, Verhoeven, Steele, Shakory and Chen2023). This gradual restructuring allows for more phonemic awareness, which in turn facilitates learning to read and write (e.g., Furnes & Samuelsson, Reference Furnes and Samuelsson2011; Johnson & Goswami, Reference Johnson and Goswami2010; Saygin et al., Reference Saygin, Norton, Osher, Beach, Cyr, Ozernov-Palchik, Yendiki, Fischl, Gaab and Gabrieli2013).

Restructured linguistic representations do not only influence one’s ability to read and write; becoming literate can also affect linguistic processing the other way around. A good example of how this mechanism operates in adult emergent readers can be observed in Huettig et al. (Reference Huettig, Singh and Mishra2011). In this study, a group of low literates and a group of high literates, both from India speaking Hindi, participated in an eye-tracking experiment. During the experiment, the participants heard sentences like “Aaj usne magar dekha hai” (Today he saw a crocodile) and saw four pictures on a screen, of which none actually showed a crocodile. One of the pictures, however, was a sea turtle, which is semantically close to the crocodile. Another picture represented peas (“matar” in Hindi), which is phonetically close to the Hindi word for crocodile (“magar”). While hearing the sentence and the onset of the word “magar,” high literates tended to look at both the sea turtle and the peas, whereas low literates did not look at the picture of the peas, which suggests that low literates do not break words down into syllables (needed to detect the overlap between “magar” and “matar”). Likely, the ability to read and write has played a crucial role in high literate participants’ restructuring of their linguistic representations and thus how they process language in real time.

One could argue that such literacy-induced restructuring opens the path to meta-linguistic awareness when readers become more experienced: more fine-grained linguistic representations allow for more sophisticated use of these representations (Homer, Reference Homer, Olsen and Torrance2009; Morais et al., Reference Morais, Cary, Alegria and Bertelson1979). Kurvers et al. (Reference Kurvers, van Hout, Vallen, van de Craats, Kurvers and Young-Scholten2006), for example, compared 25 illiterate adults in the Netherlands with various non-Dutch first languages to a comparable group of literate non-Dutch adults. Results showed that the literate group outperformed the group who was illiterate (in both their L1 and L2) in tasks measuring phonological, lexical, semantic, and text awareness. In these tasks, participants had to judge whether words rhymed or whether particular sound strings were words. The fact that the illiterate participants were less able to do this can be seen as evidence that a certain amount of literacy-induced restructuring is necessary to develop meta-linguistic awareness in several linguistic domains. Note, however, that tasks measuring meta-linguistic awareness often use abstract notions of language, with little attention being paid in the design to ensure that they are truly inclusive (Siekman et al., Reference Siekman, Spit, Verhagen and Andringa2025). One can, for example, wonder how universal the term “word” is (Haspelmath, Reference Haspelmath2023) and whether this is a suitable term to use in an experimental setup that targets emergent readers. Traditional meta-linguistic awareness tasks might thus not always allow emergent readers to show the meta-linguistic awareness they possess. Emergent readers would perhaps perform better on such tasks if meta-linguistic awareness were operationalized in a manner that relates better to participants’ reading experiences and language background.

Nevertheless, developing meta-linguistic awareness as a result of becoming literate can be seen as an advantage in itself, but restructured representations will likely also have an (indirect) effect on language learning as a whole. The influence of (meta-linguistic) awareness on language learning has been studied extensively in the field of second-language acquisition (see Andringa & Rebuschat, Reference Andringa and Rebuschat2015 for an overview). Although the studies and results are diverse, most studies suggest that awareness of the target linguistic structures facilitates the acquisition process at the very least (Ellis, Reference Ellis, Doughty and Long2003) but might even be a necessary component (DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser, Doughty and Long2003; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1990). In all, we might thus observe a causal chain that goes as follows: learning to read and write restructures linguistic representations; these representations allow for more meta-linguistic awareness; and this meta-linguistic awareness is beneficial (or even necessary) for acquiring a new language. In line with this, it is not surprising that we expect to find evidence for the restructuring effect in our study. This restructuring effect implies that experienced readers will be better able to learn components of a new language than emergent readers because they have developed more meta-linguistic awareness as a result of their literacy-induced restructured linguistic representations. The question is whether restructuring, and the meta-linguistic awareness that comes with it, is the only way in which literacy aids learning a new language, or whether some kind of modality effect is also at play.

Modality effects in SLA

The benefits of literacy for learning a second language probably not only come through fine-grained representations and the resulting meta-linguistic awareness that are helpful in the learning process. The availability of written input to the language learner, in addition to aural input, might also be helpful when acquiring the target language. A classic take on this idea is Paivio’s (Reference Paivio1986) Dual Coding Theory, which is a general cognitive theory that argues that learning happens best when both verbal and nonverbal (i.e., visual) inputs are combined. There are good reasons to assume that there is a positive effect of combining visual and verbal input for learning more generally (Rosenthal and Ehri, Reference Rosenthal and Ehri2008; Schüler et al., Reference Schüler, Arndt and Scheiter2015), and multimodal learning theories have also been applied to second-language acquisition in particular (Suvorov, Reference Suvorov2022), often in the context of using subtitles as an additional tool to enhance learning (Kannelopoulou et al., Reference Kanellopoulou, Kermanidis and Giannakoulopoulos2019; Wei & Fan, Reference Wei and Fan2022).

Modality effects might also come into play when acquiring very specific linguistic components in more experimental settings. In Escudero et al. (Reference Escudero, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer2008), 50 Dutch participants had to learn novel non-words that followed English phonotactic rules. The authors were interested in the acquisition of the vowel contrast /ɛ/ and /æ/, which is present in English but difficult to acquire for Dutch learners. The target words in the experiment were pairs of words that started with a syllable that only differed with regard to this vowel contrast. Target words were, for example, /tɛnzə/ or /tændək/, which were each accompanied by a picture of a unique nonobject. To test whether participants acquired the contrast, their eye movements were measured while they heard a word like /tɛnzə/ and saw the nonobjects that matched the words /tɛnzə/ and /tændək/. If participants would have learned the vowel contrast, they should already look toward the picture that was associated with the word /tɛnzə/ upon hearing just the first syllable of the word (/tɛn/). Results showed, however, that in the absence of orthographic input, learners equally often looked toward the pictures that were associated with /tɛnzə/ and /tændək/ when hearing /tɛn/, indicating they were not sensitive to the vowel contrast between /æ/ and /ɛ/. Crucially, learners that were aided by written input (i.e., <tenze> for the word /tɛnzə/ and <tandek> for the word /tændək/) were able to learn the contrast between /ɛ/ and /æ/. Thus, it seems that written input is not only beneficial for learning lexical items. The outcomes from Escudero et al. (Reference Escudero, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer2008) show that written input can play a crucial role in acquiring phonological contrasts in a second language as well.

Other studies provide comparable results: printed text that accompanies auditory linguistic input aids learning particular phonological features in a new language, with the effect being especially strong when there are transparent and congruent orthography–phonology mappings (Escudero et al. Reference Escudero, Simon and Mulak2014; Escudero & Wanrooij, Reference Escudero and Wanrooij2010). Interestingly, the presence of written input that is unfamiliar to learners could also bolster learning, as a study by Showalter and Hayes-Harb (Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2013) shows. In their experiment, they investigated English speakers who did not speak Mandarin and had to learn non-words following the Mandarin language system. For all participants, the words were accompanied by orthographic forms in pinyin—a phonetic writing system for modern Chinese. For one group, the orthographic forms also contained tone marks, which were unfamiliar for the participants, whereas this was not the case for the other group. At the test, participants would see a picture of a nonobject that was associated with /gi-tone1/ (written as <gī>), but hear /gi-tone2/ (written as <gí>). They then had to indicate whether this match was correct or not. Participants who were exposed to the <gī> and <gí> during training were outperforming the participants who were exposed to only the written form <gi> for the two phonological variants. These results indicate that a cue that signals learners that they need to pay attention to a particular feature of the auditory input can already aid language acquisition, even when the learners are unfamiliar with this cue and do not know what it means.

Outcomes like those from Showalter & Hayes-Harb (Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2013) warrant the question whether a printed form of language might be useful to emergent readers. Studies on subtitles (e.g., Kannelopoulou et al., Reference Kanellopoulou, Kermanidis and Giannakoulopoulos2019) but also more experimental work (e.g., Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer2008) provide ample evidence that a modality effect is present for experienced readers. Written input in combination with auditory input is thus greatly beneficial when acquiring a second language, but whether such an effect is also present when second-language learners are not able to read yet is hitherto unknown. It is not unreasonable to assume that the modality effect might already be observed in emergent readers: it could well be the case that the written input provides a cueing effect, even when this input is not properly understood or decoded, and when there is no established mapping between certain sounds and symbols for the learners, as was shown in the experiment by Showalter and Hayes-Harb (Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2013). If emergent readers are indeed aided by written input, it would mean that the modality effect is not necessarily a literacy effect, because one does not need to be literate to make use of written text as an aid in acquiring a second language.

Current study

The underlying question in the present paper is not necessarily whether the restructuring and modality effects play a role in second-language acquisition, but rather when and for which groups of learners. Is a certain amount of literacy-induced restructuring necessary before participants are aided by written input when acquiring a second language? Or can the modality effect actually help in restructuring emergent readers’ mental representations? To investigate these questions, we focus on emergent and more experienced readers when they acquire phonological contrasts and lexical elements in an exploratory study. These learners learn either through auditory input only or by means of both auditory and written input in a word learning experiment. If a modality effect is also available for emergent readers, we should observe that the additional presentation of written input leads to more learning. If we do not observe learning differences between situations with or without the presence of written input, this suggests that a certain amount of literacy-induced restructuring is necessary before a modality effect comes into play.

Since we target participants with a broad range of literacy skills, a substantial part of our sample will consist of what are often referred to as LESLLA (Literacy Education and Second Language Learning for Adults) learners, which also has consequences for our experimental setup. LESLLA learners are learners of a new language who are preliterate in their first language and might not have reached the A1 level in their L2 (Minuz & Kurvers, Reference Minuz and Kurvers2021). There are good practical and theoretical reasons to focus on these participants. On the one hand, our knowledge of Second Langauge Acquisition (SLA) is largely based on highly educated participants, which hampers our theoretical understanding of the topic (Andringa & Godfroid, Reference Andringa and Godfroid2020; Tarone & Bigelow, Reference Tarone and Bigelow2012). If we want to get a better understanding of the cognitive processes involved in learning a second language, it is crucial to investigate a more varied population. In this study, investigating emergent readers allowed us to consider how developing literacy affects SLA. On the other hand, the outcomes might ultimately be of practical interest in the classroom setting. Improving second-language teaching for LESLLA learners is important for many reasons (Council of Europe, 2022), but the ways to do so are perhaps less clear-cut than for literate adults. Providing a script when learning the basic components of a new language is common practice in many educational contexts but intuitively seems unhelpful for this group of learners. Our study might contribute to a better understanding of how and when written text might be a helpful tool for LESLLA learners when they are acquiring components of a new language.

Method

Participants

For this experiment, we tested 166 adults with Levantine or Maghrebi Arabic as their first language and who were learning Dutch as their second (or third, etc.) language. Eighty-four of these participants were emergent readers in Dutch (and sometimes also in Arabic), and 82 were more experienced readers in Dutch (and often also in Arabic). This classification was based on a literacy task described below. The majority of the participants came from Syria (N = 136), with other participants coming from a variety of other countries (China, Dubai, Eritrea, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan, Turkey, and Yemen). Although all participants were taking Dutch language courses, their educational background was diverse: some held a university degree, whereas others had not learned to read and write (in both L1 and L2) until they were adults.

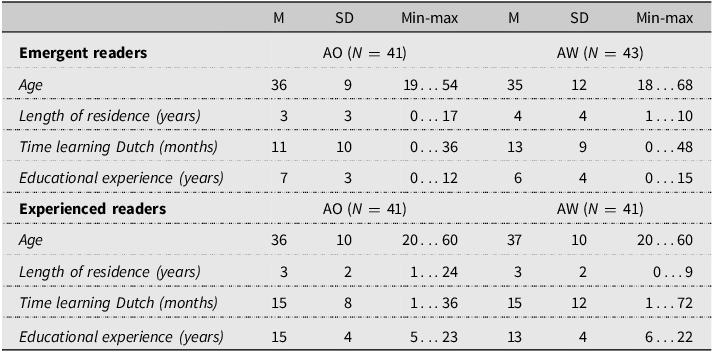

From both groups of readers, approximately half of the participants were exposed to the auditory input only during the experiment (AO; 41 emergent readers, 16 females; 41 experienced readers, 18 females), whereas the other half of the group were exposed to the auditory and written input (AW; 43 emergent readers, 16 females; 41 experienced readers, 18 females). Apart from literacy skills, we also collected data on age, length of residence in the Netherlands (through year of arrival), time spent learning Dutch (in months), and prior educational experience (in years). Descriptives of these background variables for each subgroup can be observed in Table 1.

Table 1. Background descriptives for participants in different subgroups of the experiment

Participants were recruited through language schools. Since there are no prior studies investigating this type of learning effect, we preregistered to test 30 participants per group based on convenience. However, in many of the classes where we conducted the experiment, it was possible to test more participants within the time window in which the study could take place (October 2024–February 2025), and so we adjusted the sample size upward to at least 40 participants per group.

Literacy task

To classify learners as emergent or experienced readers, we used a literacy task, for which the full materials in Dutch can be found on our Open Science Framework (OSF) page: https://osf.io/qf7nh/. The literacy task provides an estimation of participants’ literacy skills and is divided into three sections: a reading section, a timed reading section, and a writing section. Behavior during reading and writing may also be indicative of the level of literacy skills of individuals. Emergent readers often have different orientations to text, for instance, writing outside the margins of paper, and may demonstrate lower self-confidence while reading and writing (see Bigelow & Schwarz, Reference Bigelow and Schwarz2010 for an overview). Hence, we also scored participants on behaviors that reflect deviant text orientation and low self-confidence, as well as a lack of automatization. We scored these behaviors while they were performing the reading and writing sections of the task, but not during the timed reading task. To this end, we included performance behaviors that were part of other literacy screenings (e.g., King & Bigelow, Reference King and Bigelow2022) and relate to text orientation (e.g., not writing on the lines), self-confidence (e.g., seeking confirmation from the experimenter), or automatization (e.g., reading letter by letter). See the sections below for a description of those behaviors.

Reading section

For the first section of the literacy task which measures reading, participants participated in four series of read-aloud tasks. The first series consisted of five words and five non-words in Arabic. The real words were common words (e.g., <الله>, “Allah”), and the non-words were simple monosyllabic words (e.g., <اق>, “aq”). For the second series, participants were asked to read 10 graphemes in Arabic, which could be both numbers (e.g., <٨>, “8”) or letters (e.g., <ا>), to which they could reply with both the way it is pronounced (/a/) or with the symbol’s name (“alif”). After the two Arabic series, this section continued with two similar Dutch series. First, a series consisting of common real words (e.g., <waar>, “where”) and non-words (<taaf>), which was followed by a series of numbers (<2>) and letters (<P>). A series was terminated when the participant did not respond to two consecutive items to avoid frustration on behalf of the participant (e.g., when items 3 and 4 could not be read aloud).

The performance behaviors observed during both the Arabic and the Dutch reading series were 1) whether participants trace the text to be read with their hands/fingers, 2) whether the participant changes body posture by moving closer to the screen to read more attentively, 3) whether the participant seeks confirmation for their response (verbally or nonverbally) from the experimenter, 4) whether the participant does not immediately start reading the text that is on the screen, 5) whether the participant reads letter by letter, 6) whether the participant reads inarticulately, and 7) whether the participant reads with a lower volume. All scoring was done separately for Arabic and Dutch. During the task, audio recordings were made, allowing to score performance behaviors 4 to 7 afterward as well.

Timed reading section

If the reading section was not terminated beforehand, participants would participate in the timed reading section of the literacy task. In this section, participants would be subject to a one-minute reading task in which they had to read aloud as many words as possible from a given list of words. The Dutch one-minute reading task was based on Brus and Voeten (Reference Brus and Voeten1991), and the Arabic version was based on Hassanein et al. (Reference Hassanein, Johnson, Ibrahim and Alshaboul2023). When a participant was able to complete the reading section but indicated they were uncomfortable doing so, the experimenter also did not proceed with the timed reading section. The Dutch timed reading section would always be conducted immediately after the Dutch reading section, and the Arabic timed reading section was always conducted after the Arabic reading section.

Writing section

The third part of the literacy task was a writing section. This section consisted of eight questions, for which participants needed to write down an answer. These questions were alternatingly formulated in Dutch and Arabic. The first four questions asked participants to write down their name and age, both in Arabic and in Dutch. The following four questions asked participants about their favorite food, what they do in their free time, what kind of work they have, and about their house. Participants were always asked to write their name and age, but this section of the task was terminated when a participant was unable to write down answers for any of the other questions.

During the writing section, the experimenter observed performance behaviors and indicated 1) whether participants trace the question they have to answer with their hands/fingers, 2) whether the participant changes body posture by moving closer to the screen to read the questions they have to answer more attentively, 3) whether the participant seeks confirmation (verbally or nonverbally) from the experimenter, 4) whether the participant delays writing down an answer after the text is presented on the screen, 5) whether the participant writes without fluidity, 6) whether the participant stops while writing down their answer to double-check the correctness of individual letters, 7) whether the participant vocalizes while reading the question they have to answer, 8) whether the participant writes down their answer in the opposite direction of the conventions of the language (from left to right for Arabic questions, or from right to left for Dutch questions), and 9) whether the answers are written outside of the lines. Scoring for this section was based on the full set of writing items. For each of these performance behaviors, the experimenter indicated whether the participant did not show this behavior at all, showed this behavior during a part of the writing items, or showed this behavior during all of the writing items. During this section, audio recordings were made, allowing to score performance behavior 7 afterward. Since performance behaviors 8 and 9 relate to the written output of the participant, we could score these behaviors afterward as well.

Reader groups

Participants were classified as emergent or experienced readers based on their overall performance on these three sections. Because most emergent readers have some (although sometimes very little) experience in reading and writing, we did not expect participants to be fully preliterate. We therefore expected them to be able to read most of the words correctly but also thought they would show some of the performance behaviors described above that indicate they are not so experienced in reading and writing. Showing a single performance behavior is not necessarily indicative of being an emergent reader. However, when a certain number of these performance behaviors are shown by a participant, this can be taken as an indication that they are emergent readers. We therefore classified readers as emergent readers in a given language if they did not read aloud all of the items or if they showed at least three of the performance behaviors during some or all of the test items in either the reading section and/or the writing section. Participants were also classified as emergent readers if they could not read more than 15 words during the timed reading section. Participants were classified as experienced readers when they provided an answer to all the writing questions, only showed two or fewer of the performance behaviors during the reading section and the writing section, and read more than 15 words during the timed reading section.

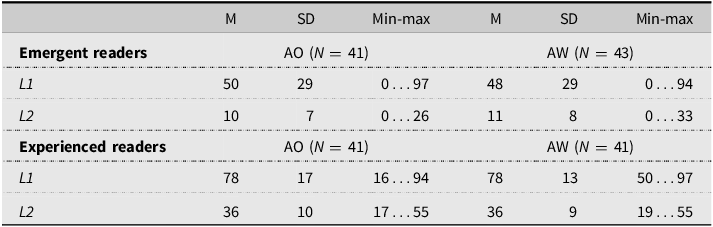

For the word learning experiment, participants were grouped in the emergent or experienced reader group based on their literacy skills in Dutch. Because it is conceivable that emergent readers were also emergent readers in Arabic, we also collected information on reading skills in Arabic. This literacy task was not a prevalidated test, and cutoff criteria were established on the basis of small-scale pilots and criteria that are used in participating language schools. Table 2 shows the number of words participants in the four experimental groups were able to read during the one-minute reading task in Arabic (L1) and Dutch (L2). A full breakdown of which performance behaviors participants showed during other sections of the task can be consulted in our supplementary materials on OSF.

Table 2. Descriptives for the number of words participants read during the one-minute reading task

Word learning experiment

To assess whether written input enhances word learning and the acquisition of phonological contrasts in emergent readers, we used a word learning task in which participants had to learn eight non-words. Four of the words were bisyllabic words and did not share any structural properties between them: /bIspɐk/, /densIm/, /hIftɐm/, and /sertɐt/. Orthographically, these words are denoted as <bispak>, <densim>, <hiftam>, and <sertat>, which are non-words in both Dutch and Arabic. All bisyllabic nouns can be written down with six letters following Dutch writing conventions. The other four words were monosyllabic, and all had a comparable consonant–vowel–consonant structure. The monosyllabic words are all minimal pairs, with only the vowel alternating between the different words: /fɛf/, /fæf/, /fIf/, and /fʏf/. Orthographically, these words are denoted as <fef>, <faf>, <fif>, and <fuf>. The vowel contrasts in these words are contrasts that are not present in Arabic (/ɛ/ & /æ/ and /I/ & /ʏ/; Holes, Reference Holes2004). None of the resulting four non-words exist in Dutch and Arabic. We did not include more than eight words in the experiment, as a small-scale pilot study showed that including more words to be learned was an unrealistic target for many emergent readers. This is probably due to the little experience that emergent readers have with participating in experimental research.

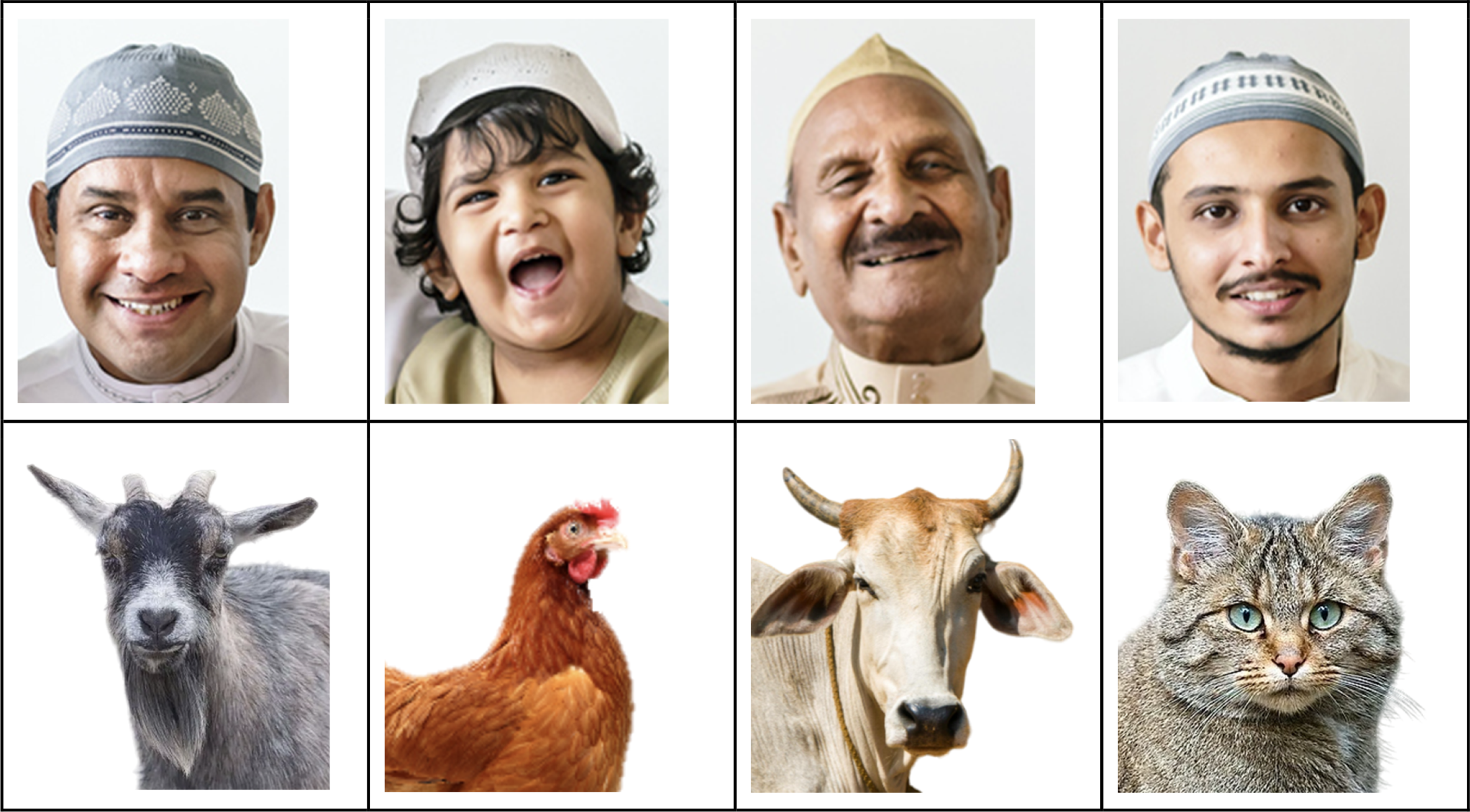

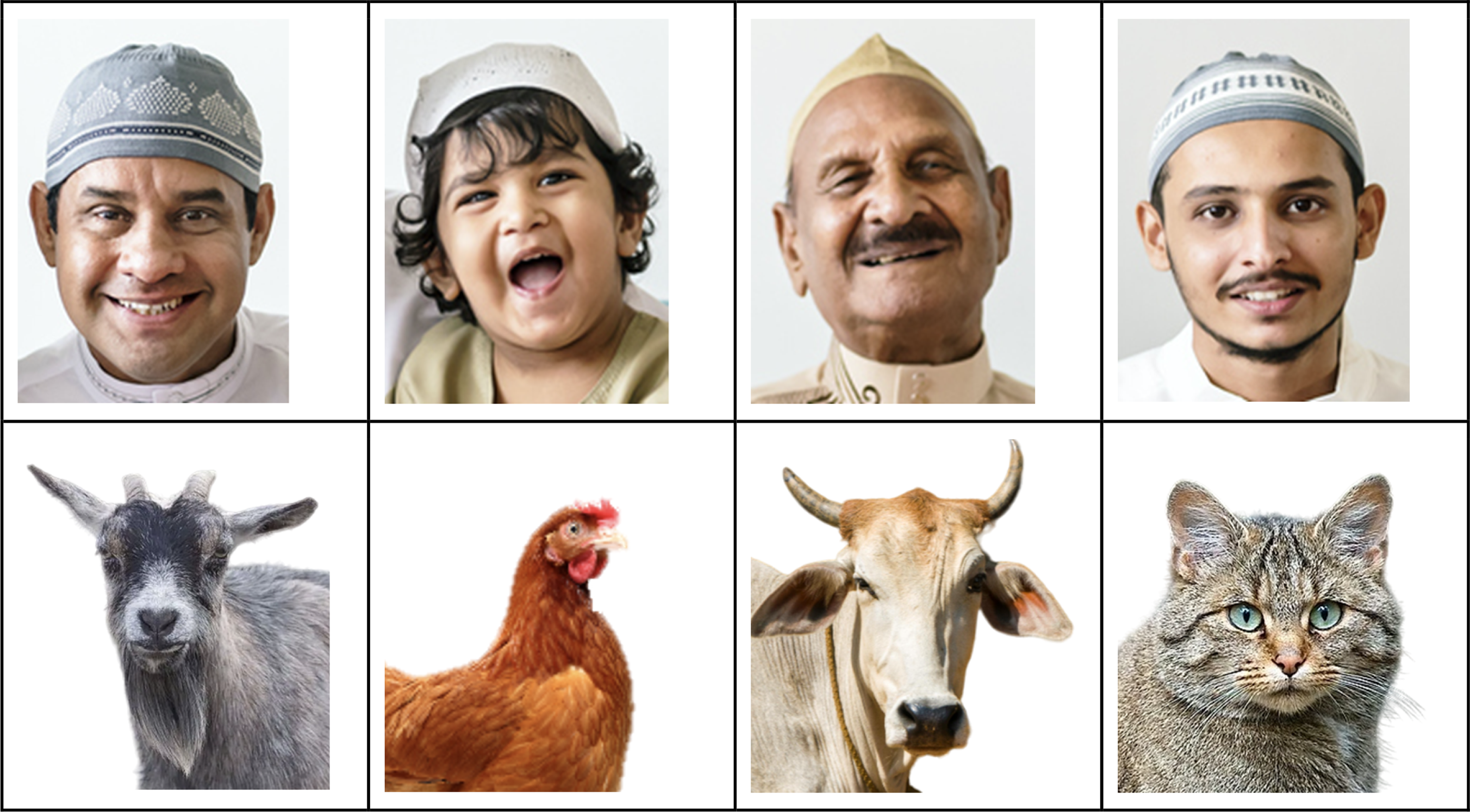

Participants learned these non-words as names of people and pet animals. We choose this setup because for many preliterate language learners it might be conflicting to acquire novel labels for existing objects when they already might have difficulties acquiring the labels for these objects in the actual language (in this case Dutch) they are acquiring. To learn these words, participants were introduced to Mirjam who has four male family members and four pet animals. Participants saw pictures of these family members and animals on a screen and heard their names when the pictures were shown. Participants were asked by Mirjam to remember the names of her family members and her animals. Pictures of the family members and animals are shown in Figure 1. All pictures in the experiment were taken from Unsplash and fall under the Unsplash + license (https://unsplash.com/plus/license). The four bisyllabic words were the names of the family members, and the four monosyllabic words were the names of the pet animals. For each participant, the mapping between the names and the pictures within each of these two groups of names was randomly generated.

Figure 1. Figures of family members and animals that participants had to learn the names of.

The experiment started with an explanation of the procedure, followed by a learning phase during which participants learned the bisyllabic names of the family members. Next, they were tested on their knowledge of these words. The experiment then proceeded with a second learning phase, during which participants learned the monosyllabic names of the animals, which in turn was followed by a test measuring their knowledge of this set of words. The test finished with a test phase in which participants saw pictures of both family members and pet animals and had to match the name to the right family member or animal.

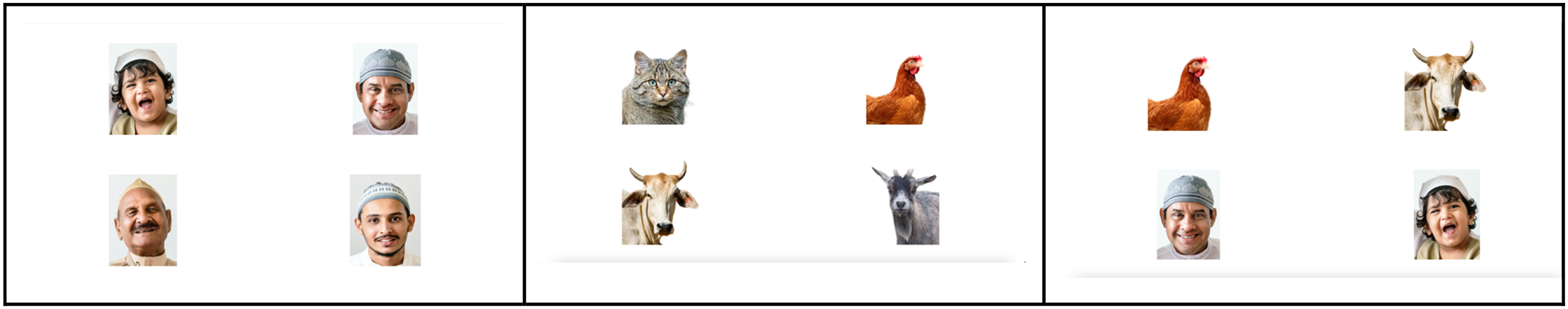

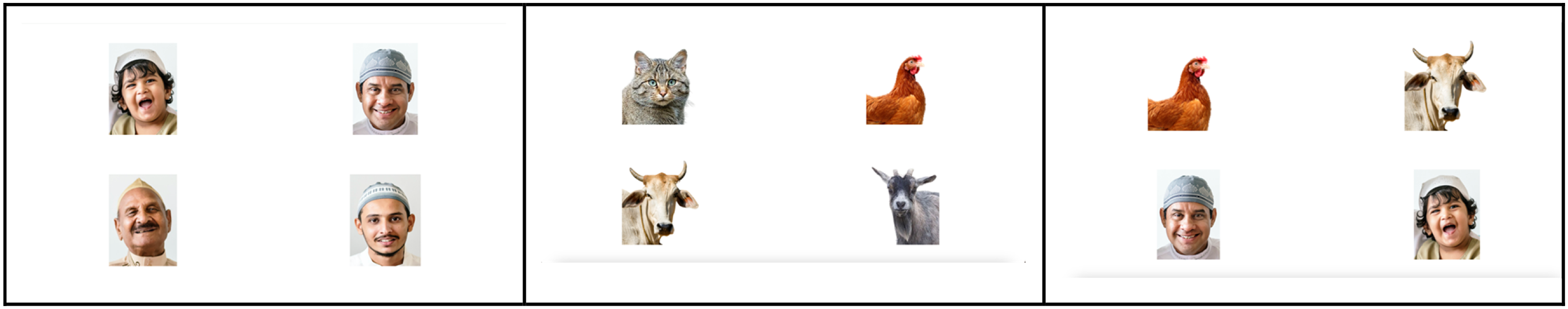

During each of the learning phases, participants saw pictures and heard sentences describing the pictures. These sentences were spoken in Arabic and always took the same form (هذا ال X, “This is X”). Participants simply sat and watched during this part of the experiment. Each word was presented six times, leading to 24 learning trials for each of the two learning phases. In the AO condition, participants received only auditory input to learn the words; in the AW condition, a written form of each name was presented below the picture in Roman script in addition to the auditory input. All test phases consisted of a picture matching task with 12 trials. For each trial, participants saw four pictures of the family members or animals they encountered during the learning phase and were asked to point toward the target picture when asked where they saw the target (أين ترى واحدة X, “where do you see X”). Each of the test phases measured word learning through a picture matching task, which highlighted a specific component of the words. See Figure 2 for an example of a test item for each of the three phases.

Figure 2. Examples of test items from phase 1 (left), phase 2 (middle), and phase 3 (right). For each test item, participants heard the question “where do you see X” and had to point toward the picture of X.

In the first test phase, participants saw four pictures of family members and heard a bisyllabic word describing one of these family members. This test measured whether or not participants learned the word-to-picture mappings: test trials only tap into participants’ lexical knowledge. Each word was tested three times, and all four pictures were placed in the same order for all test items for a single participant. This order was randomly generated per participant.

In the second test phase, participants saw four pictures of animals and heard a monosyllabic word. In this phase, the vowel contrast was essential for choosing the right picture. This test thus measured whether written input enhances learning a phonological contrast. Again, each word was tested three times, and all four pictures of the animals were placed in the same order for all test items which were randomly generated per participant.

In the third test phase, participants saw four pictures of a mixture of family members and animals (two each) and heard both monosyllabic and bisyllabic names. A random set of six monosyllabic and six bisyllabic words was tested in this phase, and for each item a novel set of four pictures was shown on the screen. These test items could be used to assess participants’ structural knowledge: did they map bisyllabic words to the family members and monosyllabic words to the animal? When participants hear /fɛf/ and consistently map this to an animal (either the target or a competitor), this can be taken as an indication that participants possess some meta-lexical knowledge about word length and that they developed awareness of the structural aspects of the words.

Procedure

The task was administered at schools where participants were following language classes. A group of four experimenters tested all participants. Prior to testing participants, the experimenters would join as co-teachers for 1–3 lessons, as part of the collaboration with the language schools, but also to gain trust from participants that often did not have much experience with participating in scientific research.

Both the literacy task and the word learning task were presented on a laptop using Experiment Designer. Participants always first participated in the literacy task and then in the word learning task. For the literacy task, all items from the reading section were shown on the screen. Words that were included in the timed reading section were presented on a sheet of paper. Voice recordings were registered automatically for each word. The experimenter guided the participant through the task by pressing a button to indicate whether a word or grapheme was read aloud correctly. While doing so, the experiment would automatically move to the next section based on the cutoff criteria described above. For the writing section of the literacy task, the questions were presented on screen, but participants were asked to write down their answers using pen and paper. The complete literacy task took approximately 10 minutes when fully completed.

For the word learning experiment, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions. During the learning phases of the experiment, words and their accompanying pictures were presented for 3 seconds before automatically moving to the next word. For the test items, participants heard a test sentence and were asked to point toward the picture they think matches the novel word. The experimenter then pressed a button that corresponds to the answer the participant gives. Scores from this phase were registered by the software. The full word learning experiment also took approximately 10 minutes.

We obtained ethical approval for this study from the University of Amsterdam Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Humanities, and we obtained active consent from participants before the start of the study. All participants were explained the procedures through a video recording in their first language and were asked to give their consent through a voice recording. Instruction for both experiments was also prerecorded in Arabic. Explaining the procedure and conducting the literacy task and the word learning task together lasted 20–25 minutes per participant. Full materials can be found on our OSF page.

Analyses

To investigate whether participants acquired particular components of the language, we calculated the number of target items that participants gave separately for each of the three test phases. For the first test phase, the target answer is simply the picture that matches the non-word. A higher number of target answers indicates better learning of these words. For the second test phase, the target answer is also the picture that matches the non-word. Again, a higher number of target answers indicates better learning of these words and also means that participants acquired the phonological contrast. For the third test phase, the target answer is produced when participants point toward a family member when they hear a bisyllabic word or when they point toward an animal when they hear a monosyllabic word. In this case, a higher number of target answers indicates that they have been able to match the structure of the word to the right class of pictures.

To inferentially test whether there is a modality effect or only a literacy effect at play, we ran three Bayesian logistic regression models (see Geambașu et al., Reference Geambașu, Spit, van Renswoude, Blom, Fikkert, Hunnius, Junge, Verhagen, Visser, Wijnen and Levelt2023; Spit et al., Reference Spit, Geambașu, Renswoude, Blom, Fikkert, Hunnius, Junge, Verhagen, Visser, Wijnen and Levelt2023; for other examples), one for each of the three learning phases. Each of these three models took the target answer (1 for a target answer and 0 for a non-target answer) as the dependent variable, reader group (emergent/experienced reader) and modality (AO/AW) as between-participants fixed effects, participant as between-participants random effects, and all unique non-word-to-picture mappings that could be learned as a within-participants random effect.

In general, we expected a main effect of literacy, with the experienced readers performing better in each of the three test phases than the emergent learners. This would indicate that experienced learners have undergone literacy-induced restructuring. The main effect of modality and the interaction between reader group and modality, however, are the effects that were of more interest to see whether preliterate learners might also make use of the written input. If we observe a main effect of modality but no interaction between reader group and modality, this can be taken as an indication that written input is useful, regardless of the level of literacy that participants have. This suggests that a modality effect is also available for emergent readers. If we observe a main effect of modality, and an interaction between reader group and modality (where the effect of reader group is stronger for experienced readers), this can be taken as an indication that both emergent and experienced readers use the written input, but that experienced readers use it more than emergent readers. If, however, we observe no main effect of modality but do observe an interaction, this could be seen as an indication that only emergent readers use the written input to acquire components of the language, and this would suggest that the modality effect only comes into play after readers have undergone sufficient literacy-induced restructuring. These possible outcomes apply to each of the three distinct test phases.

For all three models, orthogonal sum-to-zero contrast coding was applied to the binary fixed effects (i.e., group and modality; Baguley, Reference Baguley2012, pp. 590–621; Schad et al., Reference Schad, Vasishth, Hohenstein and Kliegl2020). We kept the models as fully specified as possible (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013) by including random intercepts for participant and non-word and by including random slopes for group and modality per non-word, as these both vary per non-word that could be learned. We used the R-package brms (Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2021) to fit these models and included generic weakly informative priors for all fixed effects (Gelman et al., Reference Gelman, Jakulin, Pittau and Su2008; Gelman, Reference Gelman2020). We conducted Bayesian analyses because this allowed us to calculate a Bayes factor (BF) for each of the three models. The BF makes it possible to differentiate between evidence for the null hypothesis, evidence for the alternative hypothesis, and lack of evidence altogether, which proves especially useful when interpreting the outcomes of studies with relatively small sample sizes.

Although literacy is likely to be a continuous construct on which participants can vary in degree, we preregistered to binarize literacy in our models by identifying emergent and experienced reader groups. However, our data allow for including literacy as a continuous predictor in our models if we take the one-minute reading task as a proxy of literacy. Therefore, we also ran a series of exploratory analyses, which were not preregistered. These analyses showed a similar pattern to our preregistered analyses (although BFs are sometimes a bit more pronounced), and we present the outcomes on our OSF page. Code for all preregistered analyses can also be consulted on this OSF page.

Results

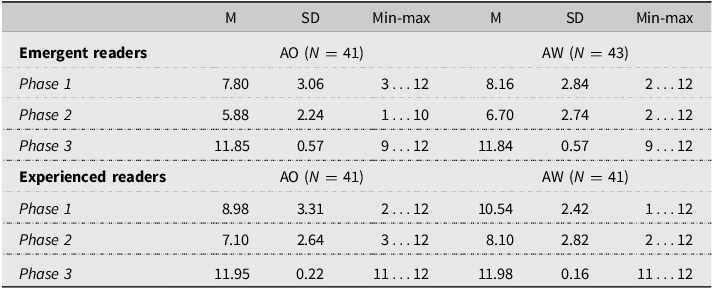

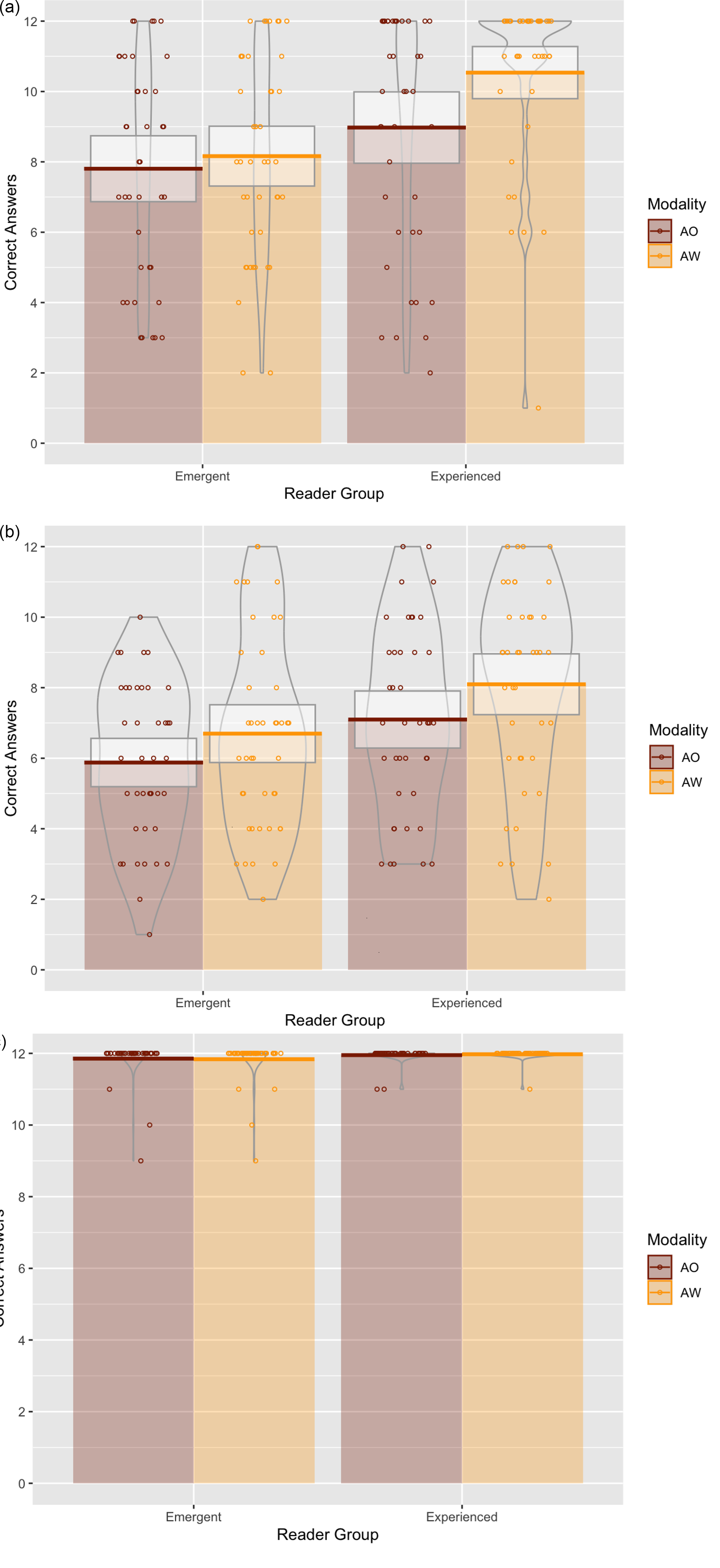

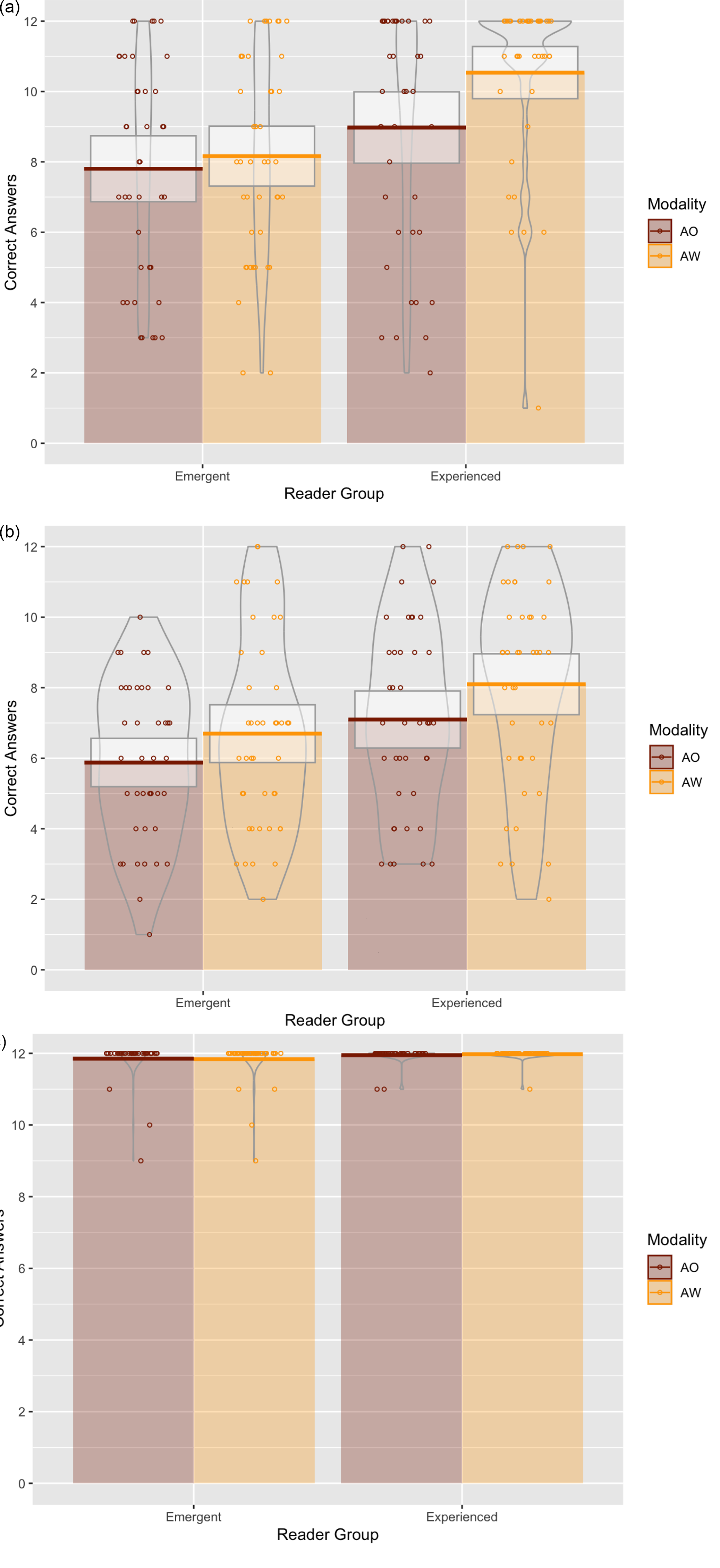

Table 3 shows descriptives of the number of correct responses per experimental group for each of the three test phases of the word learning task, which are visualized in Figure 3. As described in the analysis section, we fitted three Bayesian mixed-effects models to investigate the learning effects in each of the three test phases in more detail.

Table 3. Descriptives for the number of words participants learned during the word learning experiment in the AO (auditory only) or AW (auditory and written) condition

Figure 3. a, b, c. Pirate plots visualizing the results from our word learning experiment for each of the three phases, split by the type of input (AO = auditory only, AW = auditory and written) participants received and the reader group they belonged to.

For phase 1, our analyses showed an effect of the reader group on word learning (β = 1.20, 95% Credible Interval (CI) [0.61, 1.80], BF10 > 100). The obtained BF indicates there is substantial evidence for the alternative hypothesis, which states that experienced learners learn more bisyllabic words than emergent readers. We also observed that participants in the AW condition were better able to learn the words than participants in the AO condition, but we cannot draw strong conclusions based on the BF (β = 0.61, 95% CI [0.00, 1.22], BF10 = 1.96). Furthermore, we observed an interaction between input type and reader group, with experienced readers benefiting more from receiving additional written input than emergent readers (β = 0.67, 95% CI [−0.52, 1.82], BF10 = 1.15), but we cannot draw any conclusions based on this outcome.

For phase 2, we observed a comparable main effect of reader group on acquiring the phonological contrast. Experienced learners learn more monosyllabic words than emergent readers too (β = 0.67, 95% CI [0.18, 1.18], BF10 = 8.33). We also obtained anecdotal evidence that participants in the AW condition were better able to learn these words than participants in the AO condition (β = 0.38, 95% CI [−0.00, 0.77], BF10 = 1.30). Furthermore, we observed moderate evidence that there is no interaction between input type and reading experience for the phonological contrast (β = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.67, 0.72], BF01 = 3.00).

For phase 3, we wanted to see whether we observed a comparable main effect of reader group on meta-lexical knowledge. In general, we observed quite strong ceiling performances on this part of the task, with nearly all participants being able to match names with the categories. Unsurprisingly, we did not find any strong evidence for any main effects of reading experience (β = 0.80, 95% CI [−0.64, 2.19], BF10 = 1.33), input condition (β = 0.16, 95% CI [−1.21, 1.62], BF01 = 1.40), or an interaction between those two (β = 0.15, 95% CI [−1.54, 1.88], BF01 = 1.08). An additional analysis, which took the actual correct answer as a dependent variable, can be consulted on our OSF page and does show effects that are comparable with the outcomes of the first two phases.

Discussion

In this study, we used a word learning experiment to see to what extent restructuring and modality effects might play a role when emergent and more experienced readers acquire specific components of a new language. The experiment targeted general word learning that included a phonological contrast and meta-lexical knowledge. When participants had to learn bisyllabic words and when they had to acquire monosyllabic words that only differed by a vowel, we observed a main effect of reader group. More experienced readers were better able to learn these items, regardless of the type of input they received. This could suggest that some literacy-induced restructuring plays a role when learning a novel language, although it is difficult to separate a possible literacy effect from other confounding effects (e.g., schooling education and language aptitude) in our experimental setup. Nevertheless, the observed effect is not surprising and is in line with earlier studies that found performance differences on various linguistic tasks between emergent and experienced readers (e.g., Kurvers et al., Reference Kurvers, van Hout, Vallen, van de Craats, Kurvers and Young-Scholten2006). One way to interpret these outcomes is that experienced readers would be better able to process new words they have to learn because of their reading ability and altered linguistic representations. What remains unclear from our experiment is whether this happens because of restructuring taking place in the L1 or the L2, since our more experienced readers in Dutch also tended to have a bit more experience in reading in Arabic. Again, we should stress that our method does not allow for strong causal claims, and we cannot rule out that other confounding factors might also drive (part of) the group differences we observed.

Although the evidence was not always substantial, we also observed main effects of modality in the first two test phases of the experiment. This suggests both groups of learners benefit to some extent from written input, and there might perhaps be a small modality effect even in emergent readers. This could indicate that indeed a form of written input could already be beneficial, even though this cannot be decoded properly at full speed (as we have seen in Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2013). However, upon a closer look into the emergent reader group, we can see the benefit of written input seems only very marginal. Furthermore, we also saw hints of an interaction between modality and reading experience when learning the bisyllabic words, indicating that more experienced readers benefit more from written input when words are very distinct. It is conceivable that the main effect of modality is in fact driven by the emergent readers who already possess some reading experience, but not enough to classify them as experienced readers—our exploratory analyses with the one-minute reading task score as a predictor are in line with this explanation. Even though the main effect of modality is very small, we should not rule out the idea that at least some written input might be of aid also for emergent readers. For classroom settings, it might however be more useful to know that providing this written input did not seem to do any harm. Participants were not performing worse on the learning task when provided with written input by, for example, being distracted.

When we look at the final part of the test that tapped into meta-lexical knowledge, we observed strong ceiling effects in this part of the test which does not allow for any conclusions for this particular component. The lack of ceiling performance by experienced readers in the first two phases of the experiment was unexpected however. Based on small-scale piloting, we were expecting that for experienced readers the task might be too easy: participants only had to learn four words in each phase, and especially words in the first phase were quite distinct from one another. This did not turn out to be the case, which might be explained by the fact that the group that was experienced in reading Dutch was still diverse in terms of educational background. As such, the group differs quite drastically from samples that are typically tested in SLA research (Andringa & Godfroid, Reference Andringa and Godfroid2020). Prior studies have shown that general educational experience greatly impacts performance in scientific experiments (Kosmidis, Reference Kosmidis2017). The lack of ceiling performances thus highlights the importance of including more diverse samples to get a better picture of what various language learners, other than the typical university student, are capable of.

Including more diverse populations in our research is, however, easier said than done. We learned some valuable lessons in how this can be achieved practically and how experimental procedures can be adapted to be more inclusive, even though this was not the main study objective. We did this in three ways. First, our experimenters joined as co-teacher, which allowed them to build a trust relationship with participants and made them at ease to participate in this study. Second, we gave the L1 of the participants a central role in the experimental procedure, not only by providing instructions and consent procedures in Arabic but also by having them read in their L1 first, before doing this in the L2. Many participants indicated uncertainties during testing about their Dutch literacy proficiency, as indicated by their observed performance behaviors during the literacy task, but they seemingly enjoyed being able to show their reading and writing abilities in Arabic. Finally, our word learning experiment was set up in such a way that it was a realistic scenario to learn new “words.” A scenario in which participants learned a small number of names of people and pets made sense to these participants with little experience taking part in experimental research. Moreover, learning these names also did not interfere with their real-life language learning process, which might be the case in an experiment where participants would acquire novel words for familiar objects.

In all, our study aimed to get a first grip on the effect of learning to read and write on acquiring a novel language. Results indicate that more experienced readers perform better in our word learning experiment than emergent readers, even though we should keep in mind that our experiment is only a stripped version of the natural language learning process. Unsurprisingly, our study also shows that experienced readers benefit more from written input, but it tentatively suggests such input might also be of use to emergent readers. Although our outcomes are not always clear-cut, this study highlights the importance of including language learners with various reading experiences in future work and teaches practical lessons on how to do so too. Only by investigating diverse populations can we get a full picture of how literacy contributes to the language learning process.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Dutch Research Council (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek), grant number 406.21.CTW.007. We would like to thank Bart Siekman, Daniela Sodde, and Jo-Ann le Gallais for their help in testing, Dirk Vet for his help in setting up the experiments, and all participants, schools, and teachers for their willingness to collaborate in this project.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Replication package

Full materials (in Dutch), code, and data can be found on our OSF page: https://osf.io/qf7nh/.

Accessible summary

A one-page Accessible Summary of this article in nontechnical language is freely available at https://oasis-database.org.