1. Introduction

Altruistic behavior can be defined as a costly action taken by an actor to benefit a recipient (Fehr and Fischbacher, Reference Fehr and Fischbacher2003). This definition includes two key aspects: the benefit to the recipient (Schroeder and Graziano, Reference Schroeder, Graziano, Schroeder and Graziano2015) and the cost, in terms of resources or fitness, that the actor incurs to achieve it (Eisenberg and Miller, Reference Eisenberg and Miller1987; West et al., Reference West, El Mouden and Gardner2011). The latter aspect, involving the individual’s willingness to sacrifice personal resources, has puzzled scholars for centuries and sparked debates about the core of human nature. When evaluated according to the rational principles of neoclassical economic models (Luce, Reference Luce2012; Von Neumann and Morgenstern, Reference Von Neumann and Morgenstern1947), altruistic behaviors appear as irrational incongruities difficult to understand (Fehr and Fischbacher, Reference Fehr and Fischbacher2003; Halfpenny, Reference Halfpenny1999). However, despite their apparent irrationality (Mukherjee, Reference Mukherjee2013), selfless acts are abundant in our society, ranging from philanthropy and charitable giving to organ donations and acts of heroism. This enigma is further highlighted by numerous well-established experiments involving economic games, which have proved that individuals often engage in prosocial behaviors even in single, anonymous interactions (Camerer, Reference Camerer2011). Nevertheless, the challenge of understanding why unrelated individuals act fairly persists.

The Dictator Game (DG) has been widely used to investigate the mechanisms behind the evolution of altruistic behaviors (Forsythe et al., Reference Forsythe, Horowitz, Savin and Sefton1994; Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1986). This asymmetric game involves 2 participants: a dictator and a recipient. The dictator is given a specified amount (typically $10) and decides how much to share with the recipient, who cannot refuse the allocation. Typically, dictator and recipient remain unaware of each other’s identity and never interact directly throughout the game. Due to the game’s structure, reputational concerns, costly signaling, and punishments are not expected to play a role (Forsythe et al., Reference Forsythe, Horowitz, Savin and Sefton1994; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, McCabe, Shachat and Smith1994), enabling researchers to isolate the dictator’s unincentivized preferences toward fairness and generosity. In a world where dictators acted solely to maximize economic profit, one would expect them to keep the entire reward and give nothing to the other player. Yet, experiments conducted mostly with Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic participants report average transfers of approximately 28% (Engel, Reference Engel2011). This figure, however, is far from universal. DG behavior varies substantially both across and within societies, ranging from subsistence-based to industrialized contexts, and from what the literature labels as ‘primitive’, ‘developing’, or ‘Western’ (Engel, Reference Engel2011; Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Camerer, Fehr, Gintis, McElreath, Alvard, Barr, Ensminger, Henrich, Hill, Gil-White, Gurven, Marlowe, Patton and Tracer2005). In small-scale societies, average transfers have been found to range from approximately 20% to over 45%, with marked variation even within the same cultural group (Gurven et al., Reference Gurven, Zanolini and Schniter2008; Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Camerer, Fehr, Gintis, McElreath, Alvard, Barr, Ensminger, Henrich, Hill, Gil-White, Gurven, Marlowe, Patton and Tracer2005, Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010). Similar contrasts appear in industrialized settings. In Las Vegas, laboratory participants handed over 27%, whereas passers-by exposed to a natural-field version of the game gave nothing at all (Winking and Mizer, Reference Winking and Mizer2013). This evidence challenges the notion of humans as purely rational economic agents who behave purely according to traditional utility-maximization principles and instead points to a variable but recurring concern for fairness and aversion to inequality, shaped by cultural and contextual factors (Feigin et al., Reference Feigin, Owens and Goodyear-Smith2014).

These cross-cultural findings in the DG invite an evolutionary explanation centered on social norms. Gene-culture co-evolutionary models of strong reciprocity propose that our species evolved to reward others for norm-abiding behaviors and to punish norm violators (Fehr and Fischbacher, Reference Fehr and Fischbacher2003; Gintis, Reference Gintis2003), with respect to norms that were advantageous for the group—for example, those based on fairness, equity, and reciprocity (Feigin et al., Reference Feigin, Owens and Goodyear-Smith2014). The extended social control that resulted has helped humans maintain order and mitigate biological selfishness, laying the foundation for the development of modern society (Melis and Semmann, Reference Melis and Semmann2010). Building on this framework, evolutionary perspectives argue that, because deliberation is costly and social problems recur, selection has favored the emergence of fast, intuitive, non-deliberative routines for key moral domains (Krebs, Reference Krebs2008). Consistent with this, research shows that fairness-related judgments can be produced quickly and with limited deliberation, especially under time pressure (TP; Cummins and Cummins, Reference Cummins and Cummins2012; Haidt, Reference Haidt2001). Studies on DG under TP have tested this hypothesis. TP, defined as the imposition of a restricted time frame for participants to respond, is a common method used to elicit intuitive rather than deliberate responses (Tinghög et al., Reference Tinghög, Andersson, Bonn, Böttiger, Josephson, Lundgren, Västfjäll, Kirchler and Johannesson2013). In the context of DGs, TP is used to evaluate the automaticity of prosocial behavior (Fromell et al., Reference Fromell, Nosenzo and Owens2020; Rand et al., Reference Rand, Greene and Nowak2012; Rand et al., Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016). One prevailing view suggests that TP fosters prosocial behavior by engaging fast, intuitive processes that can draw either on strongly endorsed social norms or on experience-based heuristics (Capraro and Cococcioni, Reference Capraro and Cococcioni2015; Cone and Rand, Reference Cone and Rand2014; Rand et al., Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016). When a fairness-related norm is salient or deeply ingrained through social learning, limited time may increase the likelihood of a rapid, norm-congruent response (Bicchieri, Reference Bicchieri2005 ). From a heuristic perspective, individuals may rely on behavioral patterns that tend to be advantageous in everyday, repeated interactions, as formalized by the Social Heuristics Hypothesis (Rand et al., Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016), or on other simple decision rules. Because many social environments emphasize fairness and cooperation, the norms highlighted and the heuristics triggered under TP are often prosocial; however, this is not always the case, as heuristic responding may sometimes yield more self-serving choices. Conversely, an opposing perspective suggests that time delay and reflection may instead elicit more costly giving (Mrkva, Reference Mrkva2017) by encouraging a balance between the ‘should self’ and the ‘want self’ (Milkman et al., Reference Milkman, Rogers and Bazerman2008) and reducing egocentrism (Epley et al., Reference Epley, Keysar, Van Boven and Gilovich2004). Similarly, some studies have also demonstrated increased selfish behavior under TP (Krawczyk and Sylwestrzak, Reference Krawczyk and Sylwestrzak2018; Teoh et al., Reference Teoh, Yao, Cunningham and Hutcherson2020). To date, results on the impact of TP on prosocial behavior are mixed and do not consistently validate only one perspective (see Capraro, Reference Capraro2024, for a review).

Another way to explore why altruistic behavior appears is to focus on its ontogenetic development during an individual’s lifetime. DG experiments conducted in early childhood suggest that even young infants share more than expected by classic economic models (Gummerum et al., Reference Gummerum, Hanoch and Keller2008). Specifically, even though children are more selfish compared with adults, with generosity increasing with age, they still choose to allocate resources to the recipient from a very young age (Gummerum et al., Reference Gummerum, Hanoch, Keller, Parsons and Hummel2010). A study by Benenson et al. (Reference Benenson, Pascoe and Radmore2007) found that 9-year-old children were more generous in sharing stickers with unknown classmates than 4-year-olds. Similarly, research by Harbaugh et al. (Reference Harbaugh, Krause and Liday2003) reported that young children shared less than older children, adolescents, and adults. However, even though they share less, the fact that young children still engage in sharing behaviors (despite their limited life experience and underdeveloped cognitive abilities) suggests an innate basis for altruism (Warneken, Reference Warneken2013). As Warneken and Tomasello (Reference Warneken and Tomasello2006) noted, young children, not yet fully socialized, approach decisions without strategic thinking or consideration of potential consequences. This suggests that their spontaneous altruistic behavior may be rooted in innate tendencies rather than purely learned social norms.

Recently, some studies have combined the study of altruism in children with TP to understand how spontaneous versus deliberative processes influence altruistic behavior from an early age (Margoni et al., Reference Margoni, Nava, Sotis, Levy, Capraro and Nava2025; Plötner et al., Reference Plötner, Hepach, Over, Carpenter and Tomasello2021; Teoh and Hutcherson, Reference Teoh and Hutcherson2022). The aim was to examine whether acting quickly versus deliberatively changes giving. Since young children have had less exposure to social norms and expectations, their behavior provides valuable insights into early emerging patterns of altruism. Findings from these studies consistently show that TP increases the amount of resources that dictators decide to share with recipients, whereas giving more time to deliberate tends to decrease altruistic behavior.

However, studies involving TP face several methodological challenges in determining whether observed behavioral effects genuinely reflect intuitive preferences or merely experimental artifacts. For instance, TP might merely lead to increased random choices (Olschewski and Rieskamp, Reference Olschewski and Rieskamp2021; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schulz, Pleskac and Speekenbrink2022), meaning that any apparent increase in altruism during DG could simply reflect a higher rate of random allocation rather than true generosity. Here, we use random allocation to describe choices made without any deliberate decision rule. When TP prevents reflection, a child may simply pick a quantity without considering its consequences; the same nonstrategic pattern can occur when the child has no clear preference or when a minor motor slip alters the intended transfer. Such behavior contrasts with systematic strategies, such as always splitting equally or always keeping the larger share. Moreover, TP might exacerbate status quo bias—a tendency to leave the initial allocation unchanged rather than actively redistributing resources (Samuelson and Zeckhauser, Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988). The default option may serve as an easily accessible anchor, reducing the need for deliberate thinking (Capraro, Reference Capraro2024), which could result in behaviors appearing more egoistic due to a reduced tendency to share. Finally, TP might trigger more instinctive and heuristic-based reasoning (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley1972; Hockey, Reference Hockey, Baddeley and Weiskrantz1993), which, in line with the Social Heuristics Hypothesis (Rand, Reference Rand2016), can foster prosocial resource sharing as children draw on cooperative rules learned from everyday interactions. Nevertheless, other simple heuristics, such as sharing nothing and taking everything, cannot be completely excluded. To sum up, TP can lead to noisier, unstructured choices, may reinforce inertia toward the default (status quo bias), and may elicit intuitive prosociality that increases sharing. Crucially, these accounts make opposing predictions once the task is presented as ‘giving’ to or ‘taking’ from another, which reverses the operational default while keeping incentives constant. Under a random-responding account, TP should increase giving in a Give frame but also increase taking in a Take frame, thereby reducing the resources left to the recipient in the latter. Under a status quo account, TP should reduce both giving (in the Give condition) and taking (in the Take condition), implying that the recipient benefits only in the Take frame where the default favors them. Under an intuitive-prosociality account, TP should increase the resources left to the recipient in both frames. Thus, examining children’s behavior under TP in both Give and Take scenarios is necessary to empirically distinguish among these mechanisms.

The ‘Give’ and ‘Take’ frames refer to different versions of the DG designed to address criticisms that DG may not comprehensively measure altruism (Cappelen et al., Reference Cappelen, Nielsen, Sørensen, Tungodden and Tyran2013). Critics argued that DG oversimplifies real-life scenarios and ultimately lacks ecological validity (Franzen and Pointner, Reference Franzen and Pointner2013; Pisor et al., Reference Pisor, Gervais, Purzycki and Ross2020), with experimental findings potentially influenced more by the specific design rather than genuinely measuring altruistic behaviors (Bardsley, Reference Bardsley2008; Chlaß and Moffatt, Reference Chlaß and Moffatt2012). For example, depending on how resources are initially allocated and property rights perceived, participants may adhere to perceived social norms or behave in ways that enhance their self-image (Bardsley, Reference Bardsley2008; List, Reference List2007). This is particularly evident in the fact that slight changes in instructions can significantly alter dictators’ behavior due to unintended framing effects (Bergh and Wichardt, Reference Bergh and Wichardt2022).

One approach to addressing this inconsistency has been to develop alternative versions of the DG that manipulate legitimacy and property rights by allocating the total amount (or a portion of it) to the recipient, allowing the dictator to freely either take a fraction or give a portion of it (Eichenberger and Oberholzer-Gee, Reference Eichenberger and Oberholzer-Gee1998). Recent studies that included the take option reported a drastic reduction in the percentage of the resources left to the recipient. Similarly, some studies observed dictators taking resources from recipients who had a lower initial stake (Bardsley, Reference Bardsley2008; Cappelen et al., Reference Cappelen, Nielsen, Sørensen, Tungodden and Tyran2013; List, Reference List2007).

Despite the insights gained from these studies, few scholars have explored scenarios where the initial allocation of resources is completely reversed. In a ‘take-only’ version of the DG, the entire initial stake is assigned to the recipient, with the dictator having the option to choose how much to take from the recipient’s endowment. While from a purely economic perspective, the give-only and take-only versions are identical in terms of incentives, they differ significantly in framing, activated norms, and perceptions of ownership (Cox et al., Reference Cox, List, Price, Sadiraj and Samek2016). In the take-only variation, property rights are implicitly assigned to the recipient, potentially activating different norms (i.e., equity, equality, efficiency, or need; Konow, Reference Konow2023). Krupka and Weber (Reference Krupka and Weber2013) argue that such framing changes account for much of the variation in behavior across these DG variants, highlighting the role of perceptions of possession and social norms in influencing decision-making.

To date, findings on whether framing the decision as taking from (rather than giving to) the recipient affects the dictator’s behavior remain mixed. On the one hand, research by Dreber et al. (Reference Dreber, Ellingsen, Johannesson and Rand2013), Grossman and Eckel (Reference Grossman and Eckel2015), and Chowdhury et al. (Reference Chowdhury, Jeon and Saha2017) found no significant framing effects, suggesting that the way the decision was framed did not alter the dictators’ behavior. On the other hand, studies by Cox et al. (Reference Cox, List, Price, Sadiraj and Samek2016), Korenok et al. (Reference Korenok, Millner and Razzolini2014, Reference Korenok, Millner and Razzolini2017), and Kettner and Ceccato (Reference Kettner and Ceccato2014) observed differences in resource allocation depending on the initial endowment. Specifically, these studies found that dictators allocated more resources to the receiver in the taking condition compared with the giving framing. While the earlier studies attributed the null effect of framing to the activation of a social responsibility norm when interacting with a powerless opponent, the latter studies propose that both the endowment effect and a greater moral cost associated with taking resources contributed to higher allocation of resources to recipients in the taking condition (Korenok et al., Reference Korenok, Millner and Razzolini2018).

Previous literature has shown that TP can increase sharing in adults in ‘give’ scenarios, where resources are donated. However, there is limited or no research on (i) how TP affects children in DG and (ii) how TP modulates dictators’ behavior of any age in ‘take’ scenarios, where resources are withdrawn. This study aims to fill this gap by examining how 4- and 5-year-old children respond to both ‘give’ and ‘take’ conditions under TP. The study makes 2 significant contributions to the literature. First, it examines the behavior of the youngest participants eligible for these economic games, providing insights into their decision-making processes. In particular, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare children’s behavior across both ‘give’ and ‘take’ conditions, shedding light on whether the framing of a decision influences their sharing behavior. This comparison is crucial for understanding whether children act differently depending on whether they believe they are donating or taking resources. Second, by introducing TP in both conditions, this study addresses a notable gap in existing research. While TP is known to increase sharing in giving scenarios, it remains unclear whether this effect extends to taking scenarios. This research aims to clarify whether TP encourages sharing in both contexts or whether its impact differs based on the type of decision, thus supporting alternative explanations (i.e., status quo bias or random choice effects).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A sample of 124 children from 6 kindergartens participated in this experiment. Ethics approval for the experimental procedures was granted by the Ethics Committee of the IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca (53/2023). The study also received approval from the administration of the involved schools. Data collection took place at school, during regular days from October to December 2024. In each experimental session, a clinical psychologist was present to oversee the emotional well-being of the participants. Only children whose parents provided written informed consent in the days prior to the experiment were included in the study. The sample size was determined prior to the data collection and was established based on the typical sample size in this research domain, as suggested by Plötner et al. (Reference Plötner, Hepach, Over, Carpenter and Tomasello2021). The sample size from each kindergarten ranged from 14 to 41 children. After data collection, 9 participants were excluded based on the following criteria: 1 participant had a diagnosis of ASD, 5 participants did not complete the experimental task due to difficulty understanding the instructions, and 3 participants exhibited high levels of anxiety, which were addressed by the experimenter to facilitate their participation. All remaining participants (N = 115) were Italian native speakers aged 4 (38%) and 5 (62%) years (F = 50%). Participants were assigned to 1 of the 2 groups, resulting in 57 children in the Free group and 58 in the TP group. All children completed 2 experimental sessions about 2 weeks apart.

2.2. Procedure and measures

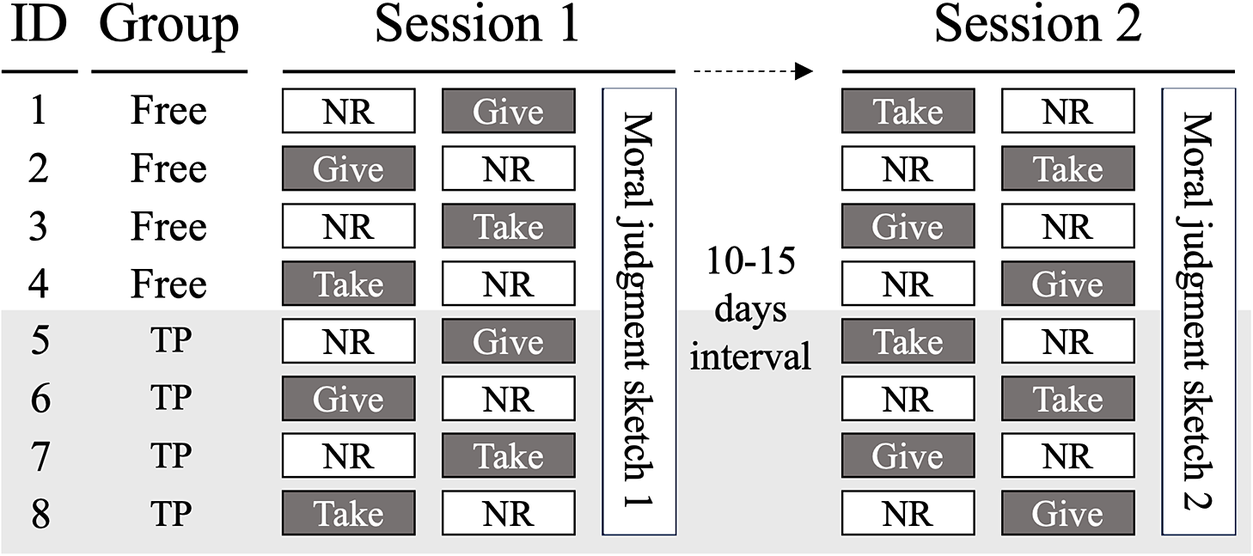

The experimental procedure was a revised adaptation of the traditional DG (Engel, Reference Engel2011). Each session was conducted by a female experimenter with many years of experience working with preschool-age children. Participants were accompanied by the preschool teacher and the experimenter to a separate room specifically arranged for the experiment. Afterward, the teacher left the room. The child was seated at one end of a table, facing a small box labeled with their name. On the opposite side of the table, there was another box of a different color with no name on it. First, the experimenter introduced the game to the child and assessed their willingness to participate. Subsequently, the experimenter presented the child with 4 types of stickers to play with (i.e., Astronauts, Pirates, Mermaids, and Unicorns). The child was asked to indicate their preferred type of sticker and which one they would most like to take home. Once the choice was made, in each session, the child participated in 2 of the following experimental conditions in a counterbalanced order. Half of the children were first presented with a neutral round (NR), whereas the other half first participated in 1 of the 2 experimental conditions (Give and Take). See Figures 1 and 2 for a graphical description of the experimental paradigm.

-

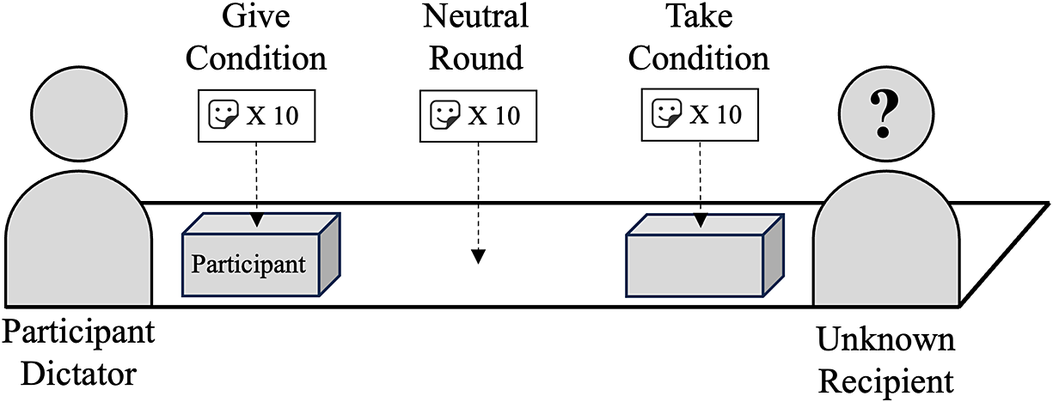

• Neutral Round (NR): In the NR, 10 of the stickers selected by the child were placed at the center of the table by the experimenter. The child was told that they were free to distribute the stickers between themselves, and another child from the same school, who was not present in the room at that moment but would come to collect them at the end of the school day, long after the participant had left the room. Once ready, the child had to pick up the stickers from the center of the table, place in their box (the one on their side of the table with their name written on it) the stickers they wanted to take home immediately after the session, and place in the box at the opposite end of the table the stickers they wanted to assign to the receiving child, who was currently not present in the room. At the end of the explanation, the experimenter reiterated that the child could choose to donate any number of their stickers to a receiving child if they wished, but they were in no way obligated to do so.

-

• Give Condition (Give): In the ‘Give’ experimental condition, after the child had chosen the stickers, the experimenter allocated 10 of them to the child’s box with their name on it. The child was informed that those stickers belonged to them, and they could take them home immediately after the session. However, they could choose to donate some stickers to another child from the same school who was not present in the room at that moment but would come to collect them at the end of the school day, long after the participant had left the room. At the end of the explanation, the experimenter reiterated that the child could choose to donate any number of their stickers to a receiving child if they wished, but they were in no way obligated to do so.

-

• Take Condition (Take): In the ‘Take’ experimental condition, once the child had made their sticker selections, the experimenter placed all of them in the box located at the opposite end of the table. The experimenter then informed the child that these stickers now belonged to another child from the same school who was not present in the room at that moment but would come to collect them at the end of the school day, long after the participant had left the room. However, at that moment, the participant had the option to take some or all the stickers belonging to the other child, move them to their own box, and take them home immediately after the session. At the end of the explanation, the experimenter reiterated that they were free to take any number of the other child’s stickers if they desired, but they were in no way obligated to take any at all.

Figure 1 Experimental procedure.

Note: Preschoolers were randomly allocated to 1 of 2 between-subjects groups (Free vs. TP). Participants took part in 2 experimental sessions approximately 15 days apart, where they completed 1 NR and 1 experimental condition in a counterbalanced order.

Figure 2 The children were seated at one end of a table with a box labeled with their names. The stickers were placed in 1 of 3 experimental positions: (1) Give: inside the participant’s box; (2) Take: inside the box of the absent recipient child; or (3) Neutral Round: at the center of the table.

Before each condition, the children were informed that while they were making their choices, the experimenter would turn their back. Moreover, the children were assured that the receiving child would never discover their identity. When children appeared uncertain or asked questions during the instructions, the experimenter offered further verbal explanations tailored to the child’s needs. This flexible approach helped ensure that each participant fully understood the task and felt comfortable throughout the session, which is particularly important when working with young children. These instructions involved a minimal form of deception (approved by the institutional ethics committee) used to maintain the perceived anonymity of the allocation.

The experimental procedure was repeated identically 10–15 days later. Each child made, in counterbalanced order, 2 new choices: one in the NR and the other in the experimental condition they did not play in the previous session. In this way, all children participated in both experimental conditions (Give and Take) approximately 2 weeks apart. Because the task was fully counterbalanced across the 2 sessions (order of frames and order of rounds), this structure naturally resulted in 2 NRs and 2 framed rounds per child, one in the Give frame and one in the Take frame. Each framed decision (Give and Take) was implemented as a single one-shot allocation per child, in line with standard developmental DG paradigms designed to minimize fatigue and maintain full comprehension in preschoolers.

The NR was included to provide a measure of children’s sharing behavior in the absence of ownership cues. In this condition, stickers were not assigned to either child, allowing us to assess how children allocate resources when no initial entitlement is implied. These trials help contextualize behavior in the Give and Take frames, where ownership and property-rights cues are central, and ensure that children understand the basic allocation task independently of framing.

Additionally, the children were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 between-subjects experimental groups: a free group (Free) and a time pressure group (TP). The 2 groups were balanced in terms of Gender, Age, and School.

-

• Free group (Free): In the ‘Free’ condition, children had all the time they needed to make their choice. During the explanations, the experimenter emphasized that there was no rush, and children could make their choice calmly. Only when they had finished dividing the stickers, closed the boxes, and were satisfied with their decision, the children were to invite the experimenter to turn around.

-

• Time Pressure group (TP): Children participating in the TP condition were prompted by the experimenter to make their choice quickly, within 10 seconds. They were informed that the experimenter would turn around once the game began, and they had to make their choice before the countdown initiated by the experimenter reached zero. If a child failed to make their choice, divide the stickers, and close the boxes in time, they would not receive any stickers. When the experimenter turned around, a 10-second countdown started. However, the experimenter covertly monitored the participant’s actions and adjusted the countdown speed based on the child’s needs. This procedure ensured that all children perceived TP without employing predefined thresholds and ensured that all children received a reward.

After each choice, the experimenter administered a comprehension check, asking who would receive the stickers in the participant’s box and who would receive the stickers in the recipient’s box. Only participants who demonstrated a correct understanding of the instructions were included in the analyses. The dependent variable was the quantity of stickers in the recipient child’s box after the DG decisions were made.

At the conclusion of each session, the experimenter administered a moral rules (MR) interview, adapted from Ball et al. (Reference Ball, Smetana, Sturge-Apple, Suor and Skibo2017). Children assessed the severity and deserved punishment for 2 moral transgressions related to unfairness (food and toy), one per experimental session, counterbalanced across participants. Pictorial stimuli depicted a scenario where a child stole an object from a friend. Initial questions explored the acceptability and punishability of the transgression. If the misbehavior was deemed unacceptable or punishable, subsequent questions assessed the severity (not much/a lot). This procedure yielded an acceptable/punishment scale ranging from 1 (acceptable/no punishment) to 3 (very unacceptable/severe punishment). We included the MR interview as a control measure to ensure that children recognized the transgressions as morally wrong and to verify that the 2 experimental groups (Free vs. TP) were comparable in their baseline moral evaluations. Establishing this equivalence helps ensure that any differences in DG allocations reflect the effects of TP and framing rather than pre-existing differences in how strongly children moralize unfair behavior.

2.3. Research questions

The present study addresses 3 research questions concerning how framing and TP shape children’s sharing behavior in the DG.

Framing effect: the first research question examines whether children share differently when the task is framed as giving versus taking. Specifically, we ask whether children allocate more resources in the Take condition than in the Give condition (RQ 1 ). This question is motivated by classic work on status quo bias and ownership framing, which suggests that individuals tend to preserve the default allocation established at the outset of the decision. In our paradigm, the default was the allocation initially set by the experimenter: in the Give frame, keeping all 10 stickers; in the Take frame, leaving the recipient’s 10 stickers untouched. According to the standard formulation of status quo bias (Samuelson and Zeckhauser, Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988), preserving this default requires no active redistribution and therefore incurs lower cognitive and social costs for the child.

Time pressure: a second research question explores whether TP influences children’s sharing across the 2 framing conditions. We ask whether children under TP allocate more stickers to the recipient than children in the Free condition, in both the Give and Take frames (RQ 2 ). This question derives from accounts suggesting that TP may heighten reliance on fast, intuitive processes that can promote prosocial responding (Cummins and Cummins, Reference Cummins and Cummins2012; Engel, Reference Engel2011).

Gender differences in response to framing: The third research question concerns whether gender moderates children’s responses to the Give and Take frames (RQ 3 ). Prior work suggests that males may be more sensitive to ownership and entitlement cues, whereas females may adhere more strongly to equity-oriented norms (Chowdhury et al., Reference Chowdhury, Jeon and Saha2017; Doñate-Buendía et al., Reference Doñate-Buendía, García-Gallego and Petrović2022). We therefore ask whether boys show greater sensitivity to the initial resource allocation (i.e., showing stronger responses to ownership rules), whereas girls demonstrate a greater adherence to equity norms (i.e., displaying more consistent sharing across conditions). This question allows us to investigate whether gendered patterns observed in adults have early developmental roots.

3. Results

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.3; R Project for Statistical Computing) and Jamovi software (version 2.3; The Jamovi Project, 2022).

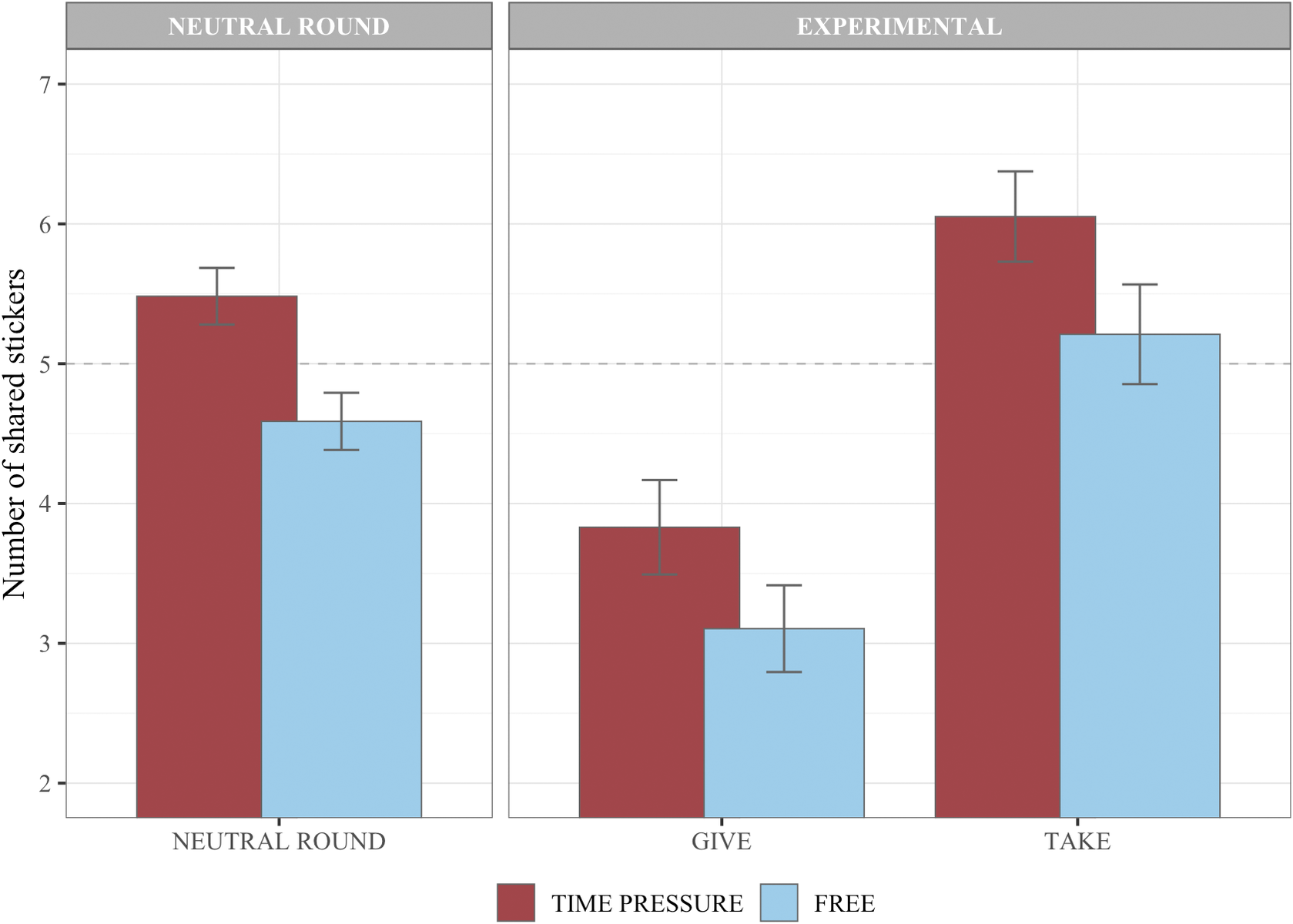

Preliminary analyses on the NRs showed that children displayed a clear tendency toward equitable allocations (overall M = 5.04; SD = 2.22). Children in the Free group left, on average, 4.59 (SD = 2.18) stickers to the other child, whereas those in the TP group left, on average, 5.41 (SD = 2.13) stickers. Because each child completed 2 NRs, we tested the group difference using a linear mixed-effects model that included a random intercept for participants and school. This analysis confirmed that children in the NRs subjected to TP left more stickers to the recipient (β = 0.90; 95%CI [0.22, 1.57]; p = .010, d = .41) (Figure 3). We also verified that adding age and gender to the model does not change the effect of TP (β = 0.89; p = .011); the results remain fully stable. Both predictors were nonsignificant (Gender p = 839; age p = .514).

Figure 3 Number of shared stickers (stickers in the recipient child’s box after Dictator Game decisions are made) in different framings under time pressure (TP) and no TP (free) conditions.

Note: This figure shows that, across all conditions, the number of shared stickers was higher under TP. The initial allocation of stickers influenced the number of shared stickers, with the Take condition showing the highest number of shared stickers. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The dotted line represents a fair distribution of resources.

In addition, we verified that the children possessed a clear concept of moral violation. In the presented scenarios, participants deemed both transgressions (the theft of the apple and of the toy robot) as highly unacceptable acts (M = 2.67; SD = .53), worthy of punishment to a large extent (M = 2.17; SD = .66). Furthermore, a Mann–Whitney test confirmed that the 2 experimental groups (Free; TP) were comparable in terms of perceived acceptability (U = 5,830; p = .071; MD = −.12) and severity of punishment (U = 6,386; p = .642; MD = −.03) in the 2 scenarios.

To assess the effectiveness of the time-pressure manipulation, we first examined the descriptive statistics of the response times. Children in the Free group took substantially longer to complete their choices (M = 31.6; SD = 16.1) than those in the TP group (M = 18.4; SD = 10.3). Because response times were positively skewed, all analyses were conducted on log-transformed response times.

We then fitted a linear mixed-effects model predicting log-RT from Group (Free vs. TP), including random intercepts for participants and schools. This model showed a clear main effect of Group: children under TP responded significantly faster than those in the free group condition (β = −.56; 95%CI [−.72, −.39]; SE = .08; p < .001). Next, we added Condition (Give vs. Take) and the Group × Condition interaction to the model. The main effect of Condition was not significant (p = .656), and neither was the interaction (p = .983). Thus, the time-pressure manipulation reliably reduced response times, and there was no statistical evidence that this effect differed between the Give and Take frames.

A linear mixed-effects modelFootnote 1 was used to analyze the number of shared stickers (DV). Descriptive statistics showed the expected framing and time-pressure patterns. In the Give frame, children shared, on average, 3.11 (SD = 2.34) stickers in the Free group and 3.83 (SD = 3.83) stickers in the TP group; in the Take frame, the corresponding means were 5.21 (SD = 2.69) and 6.05 (SD = 2.44) stickers.

We first estimated a model that included only the 2 experimental factors. This analysis revealed clear main effects of both Condition and TP. (RQ 1 ) Children shared more in the Take condition than in the Give condition (β = 2.16; 95%CI [1.59, 2.73]; p < .001),Footnote 2 and (RQ 2 ) children under TP shared more stickers than those in the free-choice group (β = .76; 95%CI [.09, 1.43]; p = .021). We then added the Time Pressure × Condition interaction to the model. The interaction was not significant (p = .858), indicating no statistical evidence that TP differentially affected sharing in the 2 frames (Figure 3).

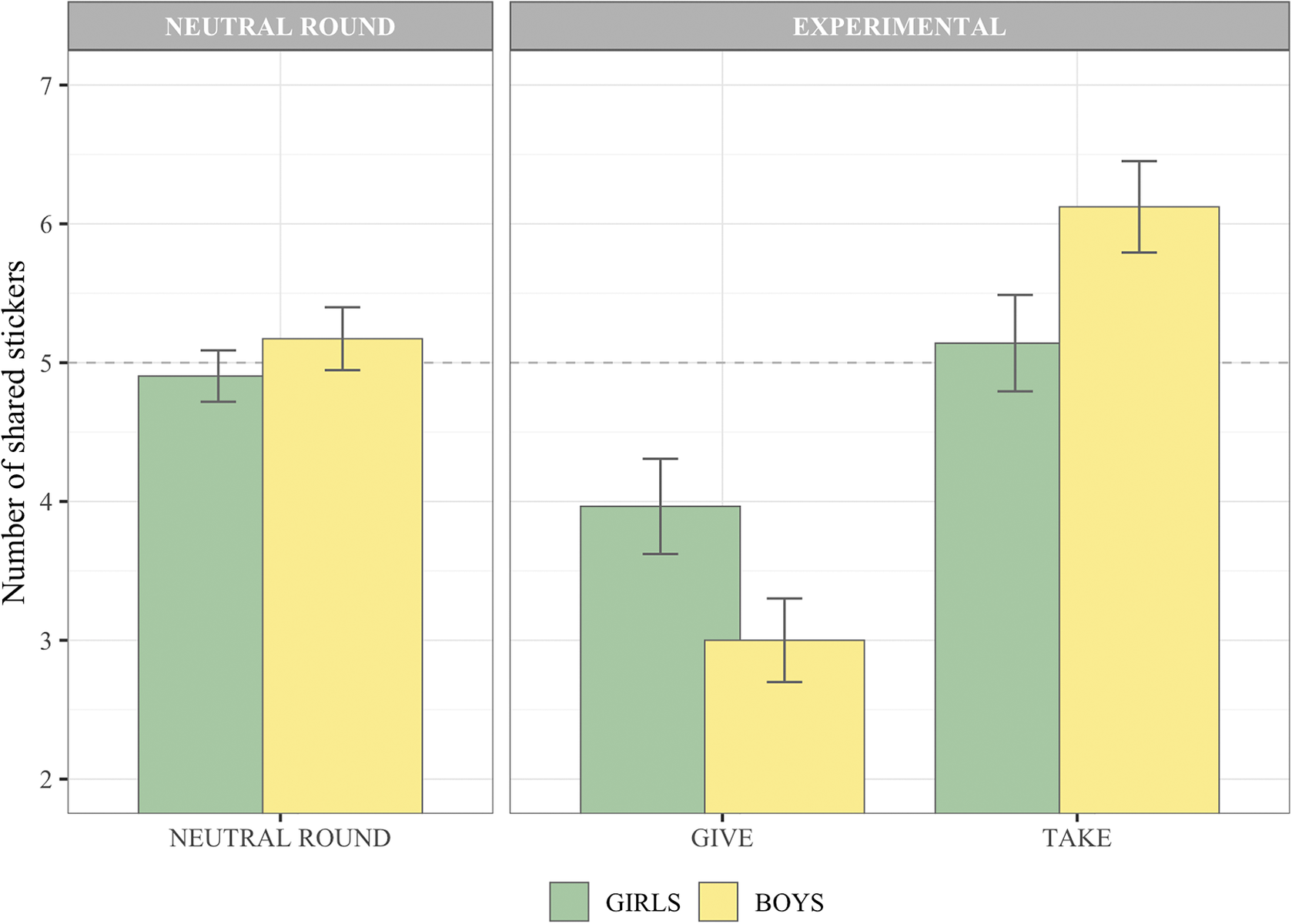

Because gender effects were of theoretical interest, we next estimated a third model that included the Condition × Gender interaction. Gender did not show a main effect (p = .999), but the Condition × Gender interaction was significant (F(1, 113) = 12.05; p < .001). Simple-effect analyses showed that the framing effect was smaller for girls (β = 1.17; 95%CI [.39, 1.96]; p = .004) and substantially larger for boys (β = 3.12; 95%CI [2.34, 3.91]; p < .001), consistent with the interpretation that boys were more sensitive to initial ownership, whereas girls behaved more equitably across frames (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Number of shared stickers (stickers in the recipient child’s box after Dictator Game decisions are made) in different conditions by gender.

Note: This figure shows the average number of stickers shared by female (Girls) and male (Boys) children in the neutral round and experimental conditions (Give and Take). The interaction between gender and the experimental conditions (Give and Take) reveals that girls shared more stickers than boys in the Give condition, whereas boys shared more stickers than girls in the Take condition. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The dotted line represents a fair distribution of resources.

As a robustness check, we tested Trial (p = .847), Session (p = .117), Age (p = .607), and the moral-evaluation scores (acceptability: p = .757; punishability: p = .423) in separate models. None of these predictors was associated with sharing and was not included in the main analyses.

Lastly, we examined the ‘Moved Stickers’ measure, defined as the number of stickers children actively changed from the initial allocation. Children moved significantly more stickers in the Take condition (M = 4.37; SD = 2.59) than in the Give condition (M = 3.47, SD = 2.50), t(114) = −2.43, p = .017 (MD = −.91), d = .23, consistent with an endowment effect whereby children altered the initial allocation more when the stickers were initially assigned to the other child rather than to themselves.

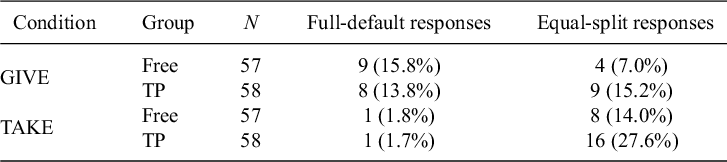

To further contextualize children’s allocation patterns, we report in Table 1 the frequency of status quo responses (i.e., Full-default: moving 0 stickers) and equality responses (i.e., Equal-split: moving exactly 5 stickers) across the 4 experimental cells (Give vs. Take × Free vs. TP). These descriptive counts provide additional insight into how children approached the task. As reported in Table 1, status quo responses were markedly more frequent in the Give frame, whereas equality responses were more common in the Take frame, patterns consistent with the endowment and ownership effects identified in the main analyses.

Table 1 Frequencies and percentages of full-default responses (no change from the initial allocation) and equal-split responses (5–5 allocations) across framing conditions and groups

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the behavior of preschoolers aged 4–5 years in a DG in which they determined the number of stickers to allocate to anonymized schoolmates. The experimental paradigm involved 2 main manipulations: TP (Free vs. TP) and Framing (Give vs. Take). Our objective was to explore how TP and framing jointly shape sharing decisions, with the goal of examining whether prosocial behavior operates automatically at this early age.

We found that children allocated, on average, approximately half of their endowment (Figure 3), which supports previous research indicating that prosocial behaviors are evident from a very young age (Warneken, Reference Warneken2013). Such a high level of sharing challenges the notion that children are less altruistic than adults (Engel, Reference Engel2011; Harbaugh et al., Reference Harbaugh, Krause and Liday2003), as the observed percentage of allocated resources exceeds the mean percentage typically shared by adults in DGs, which is approximately 30% (Engel, Reference Engel2011).

Contrary to classical economic theory, which posits that altruism should manifest equally in both giving and taking scenarios if driven solely by fairness considerations, our results revealed that children exhibited relatively low sharing behavior when the resources were initially allocated to them, while they demonstrated limited appropriation behavior (and thus a greater number of allocated resources) when the endowment was initially assigned to the other child (Figure 3). This pattern suggests that the initial allocation of resources can significantly influence sharing behavior, supporting the idea that children are sensitive to the status quo bias, where individuals prefer to maintain the current situation and avoid strong changes (Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1991). More generally, our results challenge the notion of altruism as a ‘rational’ choice in the classical economic sense—that is, a decision driven by stable preferences and utility maximization, independent of framing or context. Instead, we observe that children’s sharing is highly sensitive to how the decision is presented (Give vs. Take), time constraints, and gendered responses. These patterns suggest that prosocial behavior in young children is shaped not by abstract cost–benefit reasoning, but by a set of psychological mechanisms such as status quo bias, endowment effects, internalized fairness norms, and socially acquired heuristics. Rather than opposing rationality per se, these factors reflect a broader conception of human decision-making in which context-sensitive, norm-guided processes can override purely self-interested strategies.

Moreover, our results showed that children donated fewer stickers in the Give condition compared with the number of stickers they took in the Take condition. This result suggests an additional influence of the endowment effect in sharing behavior, over and beyond status quo bias and equity considerations: in fact, the endowment effect posits that ownership increases the perceived value of an object, making individuals more reluctant to part with it (Marzilli Ericson and Fuster, Reference Marzilli Ericson and Fuster2014). Conversely, when the stickers were perceived as belonging to another child, the children displayed less attachment and were more willing to take them, thereby increasing the number of stickers taken compared with those given away. In short, these discrepancies highlight the subtle nature of DG’s prosocial behavior, in which framing effects may activate distinct social norms and judgments of what is considered fair or acceptable (i.e., fairness, property rights, or compensation; Bilancini et al., Reference Bilancini, Boncinelli, Guarnieri and Spadoni2023; Cappelen et al., Reference Cappelen, Hole, Sørensen and Tungodden2007).

In addition to examining the impact of resource allocation on sharing behavior, we explored how TP influenced children’s decisions. Our results revealed that children allocated to the recipient a greater number of stickers under TP, suggesting that the perception of TP—rather than a strictly enforced limit—can enhance prosocial behavior (Figure 3). This pattern is consistent with the idea that TP increases reliance on fast, intuitive processes that can favor prosocial behavior, either by activating strongly learned fairness norms or by eliciting simple heuristics that often lead to generous responses (Cone and Rand, Reference Cone and Rand2014; Rand et al., Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016). At the same time, under TP, children may be less likely to engage in deliberative considerations about ownership or strategic self-maximization, and more likely to default to these intuitive responses. Consistent with this interpretation, children making quick decisions were less likely to leave the initial allocation unchanged and more likely to produce equal splits (Table 1). This interpretation is consistent with recent developmental evidence showing that prosocial behavior in early childhood is largely intuitive and becomes more frequent under TP (Margoni et al., Reference Margoni, Nava, Sotis, Levy, Capraro and Nava2025).

Previous literature has consistently reported a positive effect of TP on sharing behavior in the ‘give’ condition, suggesting that TP might enhance altruism (Cone and Rand, Reference Cone and Rand2014; Plötner et al., Reference Plötner, Hepach, Over, Carpenter and Tomasello2021). However, this observed increase could be attributed to several alternative explanations. Our study aimed to clarify these potential explanations and identify the underlying cause of the observed effect. Three key scenarios were considered to explain the effect of TP:

-

1. Random Response Hypothesis: TP could lead to more variable responses that are closer to random chance. In this scenario, TP should increase altruistic behavior in the ‘Give’ condition, while simultaneously decreasing it in the ‘Take’ framing.

-

2. Status Quo Bias Hypothesis: TP might simply reinforce the status quo, leading to reduced generosity in the ‘Give’ condition and diminished selfishness in the ‘Take’ condition.

-

3. Consistent Altruism Hypothesis: If TP consistently increases sharing behavior across both ‘Give’ and ‘Take’ conditions—resulting in more stickers being shared in the ‘Give’ condition and fewer stickers being taken in the ‘Take’ condition—this would support the idea that TP elicits fast, intuitive prosocial responses, independent of the initial allocation of resources or framing effects.

Our findings confirmed the latter hypothesis, indicating that TP consistently increases altruistic behavior across different framing conditions. Namely, the influence of TP on sharing behavior was positive across both experimental conditions (Give and Take). We believe that these results can be interpreted as supporting evidence for the automaticity and intuitiveness of prosocial behavior in humans.

However, the broader literature employs a wide array of countdown formats and penalty rules when imposing TP; this procedural heterogeneity could amplify, dampen, or even reverse the effect. Future work should therefore compare alternative implementations directly to map the phenomenon’s boundary conditions.

Additionally, our study revealed significant gender differences in response to framing conditions (Figure 4). Boys exhibited a stronger sensitivity to ownership rules, as evidenced by their heightened response to the initial allocation of resources. In contrast, girls demonstrated a greater adherence to equity norms, showing a more consistent pattern of sharing regardless of how the resources were framed. These findings align with previous research suggesting that boys and girls perceive entitlement effects and property rights differently (Chowdhury et al., Reference Chowdhury, Jeon and Saha2017). However, this result seems to contradict a broader body of literature indicating that women are generally more generous than men (see the meta-analysis by Doñate-Buendía et al., Reference Doñate-Buendía, García-Gallego and Petrović2022). While our findings support the notion that girls adhere more strongly to equity norms—resulting in greater sharing in the ‘Give’ condition—they also suggest that this pattern may reverse in the ‘Take’ condition. If future research corroborates this pattern, it could imply that women’s apparent higher generosity might not stem from an inherent altruism but rather from a heightened sensitivity to social norms related to fairness and equity. This sensitivity may lead women to share more in situations where sharing is emphasized (‘Give condition’) but also to appropriate more when resources are framed as belonging to others (‘Take condition’). Thus, the increased generosity observed in women might be more context-dependent than previously understood, potentially influenced by their responsiveness to normative frameworks rather than an intrinsic disposition toward altruism. Moreover, this divergence suggests that gender differences in prosocial behavior could be shaped by early socialization processes that reinforce different values and norms for boys and girls.

In light of the potential relevance of these findings, it is important to acknowledge that the current study presents limitations concerning sample representativeness: as noted, the results presented here refer to preschoolers living in the north of Italy. Past research has indicated that different contexts significantly differ from one another in terms of culture, fairness norms, and the development of advantageous inequity aversion (Corbit, Reference Corbit2024). It is reasonable to assume that such differences also result in different intuitions on fairness. Thus, to assess the generalizability of the current results and their stability across cultures, more studies should be conducted in the future, in a broader variety of cultural settings. Additionally, while we kept key wording consistent across conditions, we did not rely on a fully scripted or pre-recorded protocol. Although efforts were made to ensure symmetry in key expressions, future studies could further improve experimental control by adopting formalized scripts or audio delivery to avoid potential framing effects. Finally, although several precautions were taken to convey that children’s choices were anonymous (i.e., the experimenter turning away during allocation, the teacher’s absence, the child taking home their own box, and the recipient’s box being collected later), we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that some children believed the experimenter might eventually see the recipient’s box. Any such effect would likely have introduced a mild, uniform shift toward prosocial responding rather than selectively influencing specific conditions. Nonetheless, future studies should strengthen anonymity further, for example, by having allocations deposited without any adult present.

In conclusion, our study highlights that preschoolers exhibit robust tendencies toward sharing behavior, which are significantly influenced by initial resource allocation, TP, and gender. Children took less when resources were initially assigned to others, and less propensity to share when they were directly endowed with the reward. TP consistently increased altruistic behavior, indicating that children’s prosocial responses can operate in a fast, intuitive manner rather than simply reflecting respect for the status quo. Gender differences emerged, with males being more responsive to ownership rules and females adhering more to equity norms. In general, our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how young children’s altruistic behavior is shaped by psychological factors, such as ownership, framing, and TP, and highlight the importance of considering gender and social norms in interpreting prosocial behavior. Future research should continue to explore these dynamics across different cultures and developmental stages to further validate and expand upon these results.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework database at https://osf.io/uvdhg/?view_only=4a1686e14b12405db562a7a182338a81.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.C., M.M., F.P.; Data curation: M.M.; Formal analysis: M.M.; Funding acquisition: F.P.; Investigation: M.C.; Methodology: M.M., F.P.; Project administration: M.M.; Resources: M.C., M.M., S.M., F.P.; Software: M.M.; Validation: M.M.; Visualization: M.M.; Writing—original draft preparation: M.M., S.M., F.P.; Writing—review and editing: M.M., S.M., F.P.

Funding statement

Research conducted by M.M. and F.P. was supported by the PRIN 2022 PNRR research project ‘B-Hu-Well—Boosting human well-being with behavioral insights’ (PRIN 2022 PNRR, P202227LNS), funded by the European Union, Next Generation EU, Mission 4, Component 2, CUP B53D23030060001. Research conducted by S.M. was supported by the PRIN 2022 research project ‘COOPDEV—Cooperation nudges for sustainable development: leveraging behavioral insights to encourage cooperative behavior in environmental social dilemmas’ (PRIN 2022, 2022T43ACR), funded by the European Union, Next Generation EU, Mission 4, Component 2, CUP B53D23014840006.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.