Introduction

Textual sources suggest that monasteries and the clergy were influential in the agricultural flourishing in the Negev Desert between the fifth and sixth centuries AD (e.g. Kraemer Reference Kraemer1958). Communal winepresses in proximity to urban monasteries (Bucking & Erickson-Gini Reference Bucking and Erickson-Gini2020) indicate that monastic institutions had prime access to the region's major cash crop of grapes and monitored its production into wine. Gradual decline of agriculture is evident between the mid-sixth and seventh centuries AD. A variety of factors including decadal scale climatic changes and contracting international markets caused the commercial system to revert to a subsistence scale that supported smaller Islamic settlements (Avni et al. Reference Avni, Bar-Oz and Gambash2023). Some monastic institutions survived as pilgrim tourism flourished and monasteries pursued the Byzantine viniculture tradition well into Islamic times (Bucking & Erickson-Gini Reference Bucking and Erickson-Gini2020; Avni et al. Reference Avni, Bar-Oz and Gambash2023). However, archaeological approaches that explore the role of monasteries as repositories of agricultural knowledge and resilience are still sparse. It remains unclear how monasteries subsisted alongside a changing urban and agricultural environment and whether pilgrimage acted as a driver of economic growth and agricultural durability. Research at Mitzpe Shivta offers new ways to approach these questions.

The site is located in the northern Negev which formed part of an extensive holy-land pilgrimage network connecting Jerusalem and Gaza on the Mediterranean shore, Mount Sinai and Egypt (Figure 1). It is on a hilltop surrounded by areas that are dotted with Byzantine agricultural relics.

Figure 1. Byzantine settlements in the Negev (figure by the authors).

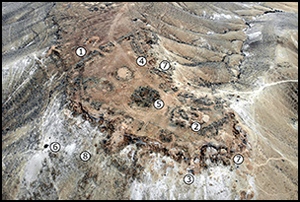

The site's main features (Figure 2) include a perimeter wall, a church, a chapel, domestic units, a courtyard house, a cistern, and rock-hewn rooms with built and natural façades. Entrances and interiors of the rooms are covered with well-preserved Byzantine inscriptions and paintings.

Figure 2. Aerial view of the site and numbers indicating main features. 1) fortification; 2) church; 3) chapel; 4) residential units; 5) caravanserai; 6) cistern; 7) rock-cut rooms; 8) garbage dump (photograph by Arne Schröder).

Mitzpe Shivta was described by Palmer (Reference Palmer1871) as a fort and was later identified as a Byzantine monastery by Lawrence and Woolley (Reference Lawrence and Woolley1914). Baumgarten (Reference Baumgarten and Stern1993) conducted an excavation in 1979 which concentrated on the church. Figueras (Reference Figueras2007) published details of three Byzantine inscriptions found on an entrance arch leading to a rock-hewn room, one of which includes the date AD 577/8. He employed another inscription to identify Mitzpe Shivta as a xenodochium (guesthouse/hostel) for pilgrims, perhaps matching the one mentioned by the Piacenza Pilgrim who travelled the Negev between c. 551 and 570 (PP Itin. 35; Caner Reference Caner2010). Radiocarbon dating from our test excavations and dated inscriptions point to an occupation of Mitzpe Shivta between the mid-sixth and mid-seventh centuries AD. Our project seeks to verify the monastic function of the site and to fill in lacunae in our knowledge of the character and role of monasticism and pilgrimage in times of economic and cultural upheaval.

Interim results

Our epigraphic survey of the Mitzpe Shivta site documented 17 newly found Greek inscriptions and Christian symbols. They are more densely located in the north and southeast areas (Figure 3), which are at the same time characterised by rock-cut architecture and good organic preservation of anthropogenic sediments. We selected three rock-cut spaces for test excavation, radiocarbon dating and microgeoarchaeological sampling (Figure 4). Area A is a unit of three contiguous rock-cut rooms on the lower northern terrace of the site. The walls of the first room contain a Christogram with remnants of white plaster and red ink, which emphasises use by Christian residents. Measurements revealed that it was carved out into a square, but its actual function is difficult to determine because rock-cut rooms in the Negev had various uses as monks’ cells, tombs, stables and storerooms (Bucking & Erickson-Gini Reference Bucking and Erickson-Gini2020). Excavation and 14C dating (Figure 5) reveal that the dung-, straw- and plant-rich sediment covering the bedrock represents the accumulation of a later Ottoman-era use of the compound as an animal stable (1484–1644 AD), which emphasises the re-use of rock-cut spaces for different purposes over time. Area B is a small rock-cut niche that connects a circular mud brick structure with a rock-hewn building; 14C dates indicate a use of the niche during the later phase of the Byzantine period (AD 562–648). The bricks and lining with white plaster could point to its function as a cistern or storage space. Microgeoarchaeological sampling revealed typical elements of the Byzantine Negev food package: grains, grapes, olives and fish bones. These finds could further support the view that the structure was used for storage. Ongoing archaeobotanical research and ancient DNA analysis may provide further clues to the cultivation strategies of the inhabitants. Area C is a three-room rock-cut complex with two entrance arches built of ashlar stones. The arches are decorated with plaster and exhibit incised and painted inscriptions. The 14C dating of organic inclusions in the plaster showed that it was made between AD 562 and 648, which is chronologically close to the inscription published by Figueras (Reference Figueras2007). Both dates coincide with the architectural expansion of the St Catherine monastery at Mount Sinai (AD 548–565) as a major pilgrim magnet. Mitzpe Shivta is in an area that boasted major traffic routes to the Sinai Peninsula during the sixth/seventh centuries (Paprocki Reference Paprocki2019: 97), so these findings may emphasise a connection between activity at the site and an increased stream of pilgrims passing by. The mention of St George in another published inscription points to the veneration of soldier saints, which was typical for Negev monasteries. Another inscription (Gambash et al. Reference Gambash, Pestarino, Lehnig and Bar-Ozin press), engraved on a lintel, may be dated to the fifth/sixth centuries AD according to palaeographic analysis. It demonstrates literacy and familiarity with ligatures from cursive scripts and refers to the book of the living, known from the Scriptures. The author of the inscription is designated as a writer accompanied by a title indicating a high ecclesiastical rank. It might represent a clue to the presence of a writing society, most likely of monks or other clergy. Further discoveries include an area containing multiple aligned stone mounds, potentially a necropolis approximately 370m from the site, which may have served as a burial place of the settlers of Mitzpe Shivta (Figure 6).

Figure 3. Preliminary map of Mitzpe Shivta based on a historic aerial photograph by Theodor Wiegand (DAI-Z-AdZ-NL-Luftbild-322-1, Mishrefe) and a map of Ya‘aqov Baumgarten (Reference Baumgarten and Stern1993) (figure by the authors).

Figure 4. Locations of the three selected study areas: Area A) three continuous rock-cut rooms on the lower northern terrace; Area B) a small rock-cut niche that connects a mud brick structure with a rock-hewn building; Area C) a rock-cut complex with two entrance arches (figure by the authors).

Figure 5. Excavation and sampling areas with finds (figure by the authors).

Figure 6. Location of the possible necropolis (figure by the authors).

Plans for the future

We intend to continue verifying the monastic identification of Mitzpe Shivta. Considering the diversity of forms of early monastic life, an architectural survey and comparison with known monasteries in the Negev, Judea and Egypt are intended to augment the previous findings at Mitzpe Shivta. Epigraphic research and excavations together with botanical, zoological and DNA analyses should help reveal cultivation strategies and the site's economic model. The project will investigate whether Byzantine agricultural knowledge was preserved in monasteries such as Mitzpe Shivta into Islamic times and if increasing pilgrimage occupied a newly evolved economic niche in places where commercial agricultural activity declined. Excavations and 14C dating in the necropolis will examine whether it was connected to the settlement. Genetic investigations of the burials, paired with an analysis of the numerous names in the inscriptions, are expected to provide clues to the genetic roots and identity of the residents and visitors of Mitzpe Shivta.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by Gerda Henkel Stiftung and Minerva Stiftung. Excavation was conducted under the license of the Israel Antiquities Authority (G-69/2022).