Feminist foreign policies have recently been adopted by numerous nation-states around the globe (Haastrup et al. 2025; Sikkink and Clapp Reference Sikkink and Clapp2024) yet there is no clear consensus on qualifying criteria. The initial declaration in 2014 by Sweden’s Foreign Minister Margot Wallstrom that the country would practice an explicit “feminist foreign policy” triggered an international conversation amongst government officials, activists, and academics on what the concept of feminist foreign policy could entail and how other global conversations on human rights, women’s rights, global hierarchies, and the contentious cultural contexts of gender and sexuality might inform this practice (Robinson Reference Robinson2021). A recurring theme in the emerging feminist political science literature on this topic is the importance of recognizing the domestic environment under which any feminist foreign policy emerges (Achilleos-Sarll et al. Reference Achilleos-Sarll, Thomson, Haastrup, Färber, Cohn and Kirby2023; Aggestam, Rosamond, and Kronsell Reference Aggestam, Rosamond and Kronsell2019; Aggestam and True Reference Aggestam and True2024) and the strategic power considerations that inform this public proclamation (Thomson Reference Thomson2022; Zhukova, Sundström, and Elgström Reference Zhukova, Sundström and Elgström2022).

Feminist foreign policies coexist, however, with a rising global backlash against gender equality. Some foreign policies can even be explicitly anti-feminist, seeking to restrict women’s rights in other parts of the world. While much research highlights certain feminist aspects of recent American foreign policy (Angevine Reference Angevine2021a; Hudson and Leidl Reference Hudson and Leidl2015; Saiya, Zaihra, and Fidler Reference Saiya, Zaihra and Fidler2017), I suggest that U.S. foreign policy has long been anti-feminist, at least in relation to one highly salient, specific feminist policy issue: legal access to abortion. For more than 50 years, restrictions established by the U.S. Congress, as well as the actions of Republican presidential administrations, have prevented the use of U.S. foreign aid to fund abortions — or even discussion of abortion as an option within health care settings — with devastating implications for the lives of women across the Global South (Skuster, Khanal, and Nyamoto Reference Skuster, Khanal and Nyamato2020).

Academic research investigating the relationship between abortion politics and American foreign policy is limited, as most scholars focus on abortion politics in U.S. domestic policy (Ainsworth and Hall Reference Ainsworth and Hall2010; Dodson Reference Dodson2006). This article maps and analyzes this anti-feminist dimension of American foreign policy in four parts. In the first section, I briefly discuss how foreign policy is constructed in the United States. In the second section, I present an overview of the history of abortion in U.S. foreign policy (“abortion foreign policy”) from 1973 to the present. Many of the most visible and substantive changes occur via executive orders issued by the U.S. President. Yet Congress also plays an important role in developing foreign policy.

In the third section, I explore a less visible aspect of foreign policymaking by conducting a content analysis of all House foreign policy bills introduced between 1973 and 2022 with the word “abortion” in its Congressional Research Service summary, comparing if these bills seek to expand or restrict women’s access to abortion and their overall legislative success. In the fourth section, I draw on 15 interviews with legislative staff and issue advocates, as well as media, congressional hearings, and press releases, to explore how anti-abortion forces informed American foreign policy related to women’s rights during the 115th Congress (2017-2018), when Republicans were in the numeric majority.

This study suggests that there are important relationships between domestic and foreign policymaking on abortion in the U.S. Over the last 50 years, feminist mobilization has played a key role in constraining efforts to restrict abortion at the federal level, where members of Congress must take into account their constituents’ preferences (Mayhew Reference Mayhew2004). This is less so when making foreign policy, explaining why anti-abortion forces have found greater success in this policymaking space. The impact of this advocacy has had damaging effects on women’s reproductive health worldwide, particularly under Republican administrations. It has also helped strengthen anti-abortion groups at home, leading to tangible rollbacks in recent years in women’s reproductive rights at the domestic level. The U.S. case thus not only helps us understand the causes and consequences of anti-feminist foreign policy but also how the dynamics of domestic and foreign policymaking interact, adding further nuance to current understandings of feminist foreign policy, international relations, and domestic gender politics.

Investigating Abortion Politics in American Foreign Policy

Understanding dynamics of foreign policymaking in the U.S. requires attention to both the executive and legislative branches. The president serves as commander-in-chief of the U.S. armed forces and the top diplomat in foreign relations, controls the U.S. Department of State and U.S. Department of Defense, and has authority over international trade agreements. These visible aspects of American foreign policy pull attention and explain the focus on the role of the president when it comes to external relations. Further, U.S. Presidents themselves have extended foreign policy powers beyond what was intended by the framers of the U.S. Constitution. Although Article 1 serves to check the power of the executive, the American foreign policy bureaucracy has expanded and the speed of warfare has accelerated over time, leading the power of the executive (Article 2) to stretch beyond these original parameters.

Despite these changes, the U.S. Congress does — and will continue to — play a major role in shaping American foreign policy. Perhaps most significantly, legislators have the “power of the purse,” with decision-making authority over all foreign policy funding. Additionally, there are numerous important ways that Congress can shape the broader foreign policy agenda: through the ability to exercise oversight over other agencies; the power to ratify international trade and treaty agreements; and the opportunity to pass laws related to U.S. foreign policy decisions (Carter and Scott Reference Carter and Scott2009). Congress matters for setting the U.S. foreign policy agenda.

Theories of congressional motivation suggest that there are important differences in how legislators approach foreign compared to domestic policymaking. On foreign policy issues, members of Congress are often driven less by the concerns of their constituents and more by their desire to gain status in the institution and/or to make good policy (Lindsay Reference Lindsay1994). This is because, outside of the few significant foreign policy decisions that directly affect the U.S. electorate, the average voter is less concerned about the details of American foreign policy decisions (Holsti Reference Holsti2004). As a result, voters carry less influence on how congressmembers make these types of decisions (Jacobs and Page Reference Jacobs and Page2005).

Abortion politics is an exception to these general trends. Abortion policy is one of the most divisive policy issues in the U.S. electorate and in the halls of the U.S. Congress (Ainsworth and Hall Reference Ainsworth and Hall2010; Norris Reference Norris2022). The issue of abortion, indeed, has arguably realigned the American political parties at the elite and mass levels (Adams Reference Adams1997; Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Kreitzer, Osborn and Swers2021; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000; Ziegler Reference Ziegler2022). As a high-profile divisive policy issue, abortion represents an opportunity for some members of Congress to advocate for their position and gain support from the electorate. This matters from the perspective of feminist and anti-feminist foreign policy because the question of legal abortion access is a key, if not the key, dividing line between feminists and anti-feminists in Congress (Swers Reference Swers2002).

Moreover, the topic of abortion challenges the reigning theory of policy incrementalism and punctuated equilibrium (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010). Rather than remaining in one policy domain, abortion politics plays out across many different issue areas and congressional committees, crossing many programs and budgets (Ainsworth and Hall Reference Ainsworth and Hall2010). Frictions in one area or on one committee may lead to efforts to alter abortion policy in other venues, as legislators may move their legislative efforts from committee to committee until they find the right internal environment. Members of Congress may act strategically by introducing abortion politics into numerous policy domains. For example, anti-feminist Representative Christopher Smith (R-NJ), Chair of the House Pro-Life Caucus, worked across policy domains, including foreign policy, to prevent abortion access (Ainsworth and Hall Reference Ainsworth and Hall2010; Carter and Scott Reference Carter and Scott2009).

Abortion policy has long been central to the American feminist movement and a driver of passionate advocacy. When access to abortion health care is prohibited, women are more likely to risk harm or death by seeking unregulated care or to be forced to carry and raise an unplanned child (Howard Reference Howard2024; Stetson Reference Stetson2001). Consequently, guaranteeing legal, safe access to abortion — commonly framed as “pro-choice” — is a core platform for many feminist political groups, including the National Organization for Women, Feminist Majority Foundation, Planned Parenthood, and the National Association to Repeal Abortion Laws, as wsell as for supportive elected leaders (Burrell Reference Burrell1996; Freeman Reference Freeman2000; Swers Reference Swers2002). One of the largest political action committees, EMILY’S List, exclusively supports pro-choice Democratic women candidates as part of its strategy to push the party toward a pro-abortion-rights position (Pimlott Reference Pimlott2010).

Feminist and anti-feminist actors in the U.S. have formed advocacy coalitions around abortion, primarily along party lines (Freeman Reference Freeman2000; Swers Reference Swers2002). Sabatier (Reference Sabatier1988, 139) defines advocacy coalitions as “people from a variety of positions (elected and agency officials, interest group leaders, researchers) who share a particular belief system—that is, a set of basic values, causal assumptions, and problem perceptions—and who show a nontrivial degree of coordinated activity over time.” In the case of abortion, these coalitions of policy entrepreneurs and interest groups fall into two camps: a pro-abortion-access advocacy coalition (feminists) and an anti-abortion-access advocacy coalition (anti-feminists).

In this context, the fact that members of Congress have greater leeway in crafting foreign policy legislation has crucial implications for creating both feminist and anti-feminist foreign policy in the U.S. When members seek to promote global women’s rights, Congress can provide a space for feminist ideas to be imagined, operationalized, and debated. These policies can, in turn, be taken up by the president. For example, in 2006 Congress passed the International Violence Against Women Act, making violence against women a foreign policy concern of the U.S. government. Two years later President Obama announced the appointment of a new ambassador-at-large for global women’s issues, designating gender equality as a central aspect of U.S. foreign policy (Angevine Reference Angevine2014).

Anti-feminist policymaking is also possible, however, if opponents of women’s rights use Congress and the presidency to roll back earlier rights or to advance an anti-equality policy agenda. Understanding these dynamics, especially in relation to abortion policy, is crucial because their impact is not simply domestic. The United States, for example, is the largest single donor to international family-planning assistance (Cincotta and Crane Reference Cincotta and Crane2001). Disputes between political elites and advocacy groups in American foreign policy have major implications for advances and setbacks in women’s rights worldwide.

Abortion and U.S. Foreign Policy Via Executive Orders

A timeline of significant moments in abortion and American foreign policy begins in January 1973 with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, which legalized American women’s access to abortion. In response, anti-abortion actors sought other ways to restrict abortion access. In December 1973 Senator Jesse Helms (R-SC) succeeded in passing an amendment to the U.S. Foreign Assistance Act of 1961. The 1973 Helms Amendment “prohibits the use of foreign assistance to pay for the performance of abortion as a method of family planning or to motivate or coerce any person to practice abortion” (sec. 104(f), as amended). In other words, this policy blocked U.S. funding for abortion services in foreign countries even when abortion itself was legal in those countries.

Outside of the Helms Amendment and its subsequent modifications, most changes in abortion foreign policy have occurred via presidential executive orders along partisan lines. In 1985 President Ronald Reagan established what became known as the Mexico City Policy — more commonly called the “Global Gag Rule” in feminist policy circles. First articulated by Reagan at a United Nations population conference in Mexico City in 1984, the policy blocked U.S. federal funding for any nongovernmental organization in a foreign country that provided abortion counseling or referrals. Subsequent presidents have followed Reagan’s lead by announcing their stance on the Global Gag Rule near the January 20 presidential inauguration — which falls just two days before the January 22 anniversary of Roe v. Wade — to signal to domestic advocacy coalitions whether they oppose or support women’s access to abortion.

Republican President George H. W. Bush continued to enforce the Mexico City Policy when he took office on January 20, 1989. Four years later, newly elected Democratic President Bill Clinton issued a memorandum on January 22, 1993 — the 20th anniversary of Roe v. Wade — repealing the policy. The anti-abortion-rights advocacy coalition was incensed by Clinton’s executive order to end the Global Gag Rule and mustered significant congressional resistance. Representative Chris Smith (R-NJ) held up the entire U.S. foreign aid bill (worth $12.1 billion) to satisfy his anti-abortion policy objectives. Reportedly, even members of his own party were unwilling to press him to concede, fearing retaliation from the anti-abortion advocacy coalition (CQ Almanac 1996).

The anti-abortion advocacy coalition proved more successful in the late 1990s at reinstating the Mexico City Policy after Republicans retook Congress in 1996. Clinton had taken numerous steps in his foreign policy administration to prioritize global women’s rights and protect access to abortion (Garner Reference Garner2013), gaining wider support from the pro-abortion-rights advocacy coalition and angering the anti-abortion faction. Although Clinton won reelection in 1996, the new Republican majority in Congress increased their anti-abortion pressure. In 1999, Clinton opted to compromise on abortion in American foreign policy and reinstated a temporary, one-year obligation to return to the Mexico City Policy as part of a broader deal to pay the U.S. debt to the United Nations.

Soon thereafter, Republican George W. Bush won the 2000 presidential election. Like his predecessors, Bush reinstated the Mexico City Policy on January 22, 2001 — the 28th anniversary of Roe v. Wade. Global feminist advocates in Congress rallied in response, led by Representative Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), then a member of the House Appropriations Foreign Operations Subcommittee. Pelosi, in a press release, criticized the influence of anti-abortion advocacy groups on American foreign policy, noting that abortion was legal in the United States:

President Bush will punish the poorest women in the world to satisfy an extreme right-wing constituency. I hope that President Bush will reconsider this ill-advised action which will have a chilling impact on international family planning… If the U.S. government tried to impose similar restrictions on U.S.-based organizations, they would, without a doubt, be unconstitutional. (Pelosi 2001)

Despite their disappointment, global feminist advocates were unable to build the congressional and broader political support needed to overturn these executive decisions. Bush was reelected in 2004, and the Republican Party retained — and slightly expanded — its majorities in both chambers for the 109th Congress (2005–07). Anti-abortion policy advocates continued to achieve anti-feminist policy success in foreign policy until Democrats regained control of the House and Senate in the 2006 midterms.

Democrats regained the U.S. presidency in 2008 with the election of Barack Obama and expanded their congressional majority. On January 23, 2009, one day after the 36th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, Obama rescinded the Mexico City Policy and called for an end to using international family planning assistance as a partisan wedge issue. On January 28, 2009, four members of Congress — Chris Smith (R-NJ), Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI), Bart Stupak (D-MI), and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL) — introduced House Resolution 708, a bill to restore the Mexico City Policy, but the bill did not pass.

Eight years later, the Republican Party regained control of both the executive and legislative branches. On January 23, 2017, President Donald Trump reinstated the Mexico City Policy, one day after the 44th anniversary of Roe v. Wade. In May 2017, Trump expanded the policy’s scope to cover any foreign NGO receiving foreign assistance, not just programs specifically focused on family planning. He renamed the policy the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (PLGHA) to signal its broader scope and underscore his anti-abortion stance. In May 2019, Trump went further, applying restrictions to foreign NGOs that received no U.S. funding themselves by prohibiting U.S.-funded NGOs from working with any foreign NGO that provides family planning services (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2020).

The policy direction changed again in 2021, when Democratic candidate Joe Biden was sworn in as president. On January 28, 2021, he rescinded the Mexico City Policy and ended Trump’s modifications to the Global Gag Rule. As a result, the United States restored financial support for numerous international family-planning health clinics worldwide. Despite these positive foreign-policy actions, U.S. domestic abortion politics soon changed dramatically. On June 24, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court in a 6–3 vote overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Court returned authority to regulate abortion to the individual states. Following the decision, numerous states took explicit policy measures to restrict abortion access. At the time of writing, 12 states have effectively banned or severely restricted legal abortion access: Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia (Guttmacher Institute 2025).

Looking at shifts in abortion foreign policy over the years, U.S. presidents have clearly used their support for or opposition to the Mexico City Policy as a signal to their respective domestic constituencies. Since the Reagan administration, Republican presidents have conveyed their anti-abortion position by restricting abortion rights in U.S. foreign policy. Democratic presidents, responsive to the pro-abortion-rights feminist faction in their party, have always rescinded these anti-feminist policies. Consequently, foreign women’s reproductive health has been subject to a game of partisan football, undermining the stability of health clinics that serve vulnerable populations and the women who rely on them for care. Moreover, as Crane and Dusenberry (Reference Crane and Dusenberry2004) find, the Global Gag Rule has not reduced the number of abortions in foreign countries. Rather, it has increased the health risks for the women who have them. In their view, anti-abortion foreign policy seeks “to limit the resources and influence of USAID’s international family planning program,” out of “a set of beliefs about the role of modern contraception in promoting promiscuity, moral breakdown, and the weakening of the traditional male-dominated family structure” (2004, 130). This salient domestic policy division clearly has global impact.

Congressional Foreign Policy Legislation on Abortion

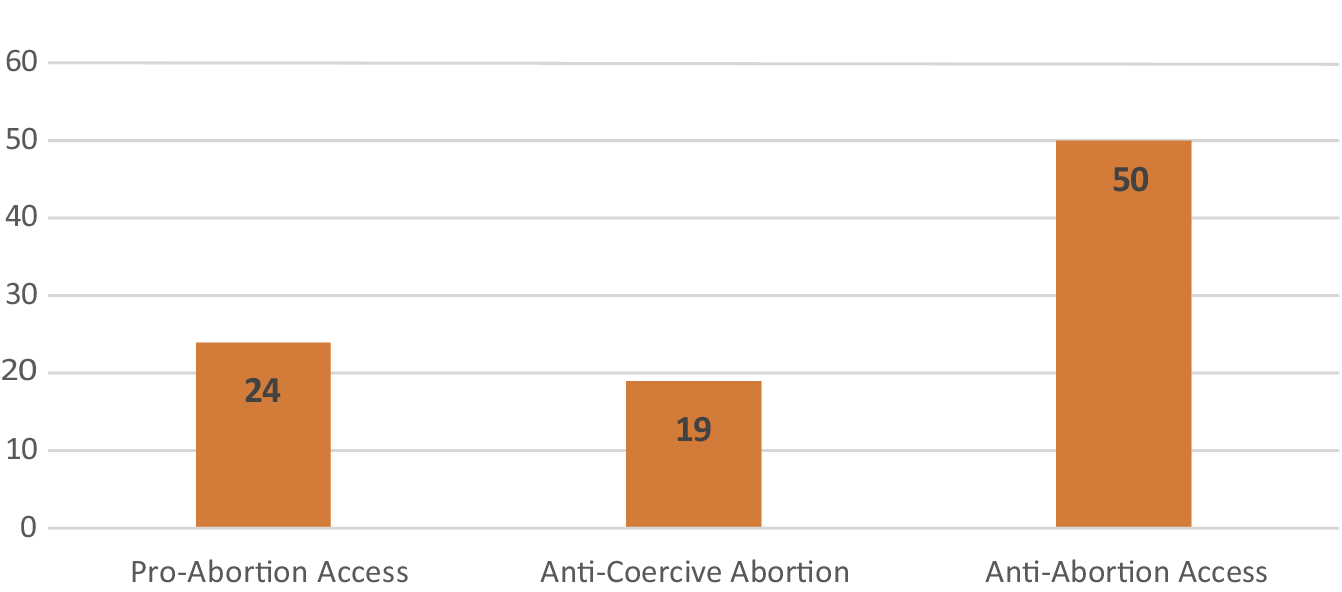

Although most attention to anti-abortion foreign policy in the U.S. focuses on the role of the president, members of Congress have written abortion into proposed American foreign policy legislation. I identify and analyze 93 bills introduced in Congress between 1973 and 2022 that include the word “abortion” in their Congressional Research Service summary and were referred to the House Foreign Affairs Committee. A content analysis of the policy position of abortion-related foreign-policy bills reveals three broad forms: those that expand access to abortion (feminist bills), those that restrict access to abortion (anti-feminist bills), and those that focus on the issue of coerced abortion — practices opposed by both global feminists and anti-choice advocates as violations of human rights. As you can see in Figure 1, of these 93 bills, 50 aimed to prohibit abortion access, 24 sought to expand abortion access, and 19 addressed coercive abortion, mostly in China.

Figure 1. Dominance and direction of U.S. Foreign Policy Bills that mention “abortion,” U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee, 1973–2022.

(Source: www.congress.gov, coding by the author)

The importance of abortion within broader foreign-policy legislation varied: in some bills it was the sole focus; in others it appeared only as a short clause. Over 14,000 foreign-policy bills were introduced during this period, so the vast majority of proposed American foreign-policy actions did not explicitly mention abortion. Nevertheless, some abortion clauses appeared in major pieces of American foreign policy, such as the 1996 foreign aid appropriations bill, and helped shape broader foreign-policy positions. Notably, most of the bills mentioning abortion aimed at restricting abortion access.

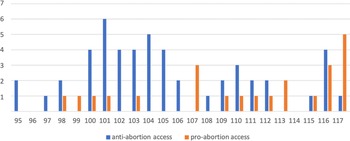

Figure 2 shows how U.S. foreign-policy attention to abortion has shifted over time. The greatest number of anti-abortion-access bills were introduced in the 101st Congress (1989–90), and the greatest number of pro-abortion-access bills were introduced in the 117th Congress (2021–22). During the 101st Congress, President George H. W. Bush, a first-term Republican, served while the Democratic Party held majorities in both the House and Senate. In the 117th Congress, President Joseph Biden, a first-term Democrat, served while Democrats controlled the House and Republicans held the Senate majority. The total number of foreign-policy bills proposed has remained relatively steady, with slightly more activity in the 1990s, while pro-abortion-access bills increased substantially in the 2020s. These data suggest that members of Congress primarily respond to executive decisions that threaten their foreign-policy goals — either feminist or anti-feminist.

Figure 2. Number of pro-abortion access and anti-abortion access U.S. Foreign Policy Bills introduced by Congress, 1973–2022.

(Source: www.congress.gov, coding by the author)

Though abortion-policy positions are generally entrenched in partisan divisions, this has not always been the case. Historically, foreign-policy leaders in Congress have taken divergent positions. The first foreign-policy bill to include an anti-abortion-access clause was the International Development Cooperation Act, introduced on February 2, 1975, by Representative Clement Zablocki (D-WI). One of the bill’s goals was to study factors affecting population growth, with an emphasis on promoting small families and family planning. However, the bill prohibited the funds available for such assistance from being used for abortions or involuntary sterilizations and is therefore coded here as anti-abortion access. The first foreign-policy bill to include a pro-abortion-access clause was the Reproductive Health Equity Act, introduced on May 30, 1984, by Representative R. William Green (R-NY). The goal of this bill was to ensure that all U.S. federal employees—particularly those in the U.S. armed forces and the U.S. Peace Corps—received health care benefits that included abortion access and reproductive health care. Green, a pro-abortion-access Republican, sponsored this bill in each Congress through 1991. In the next Congress, Democratic Representative Vic Fazio (D-CA) reintroduced the bill in 1993, and no member subsequently reintroduced it.

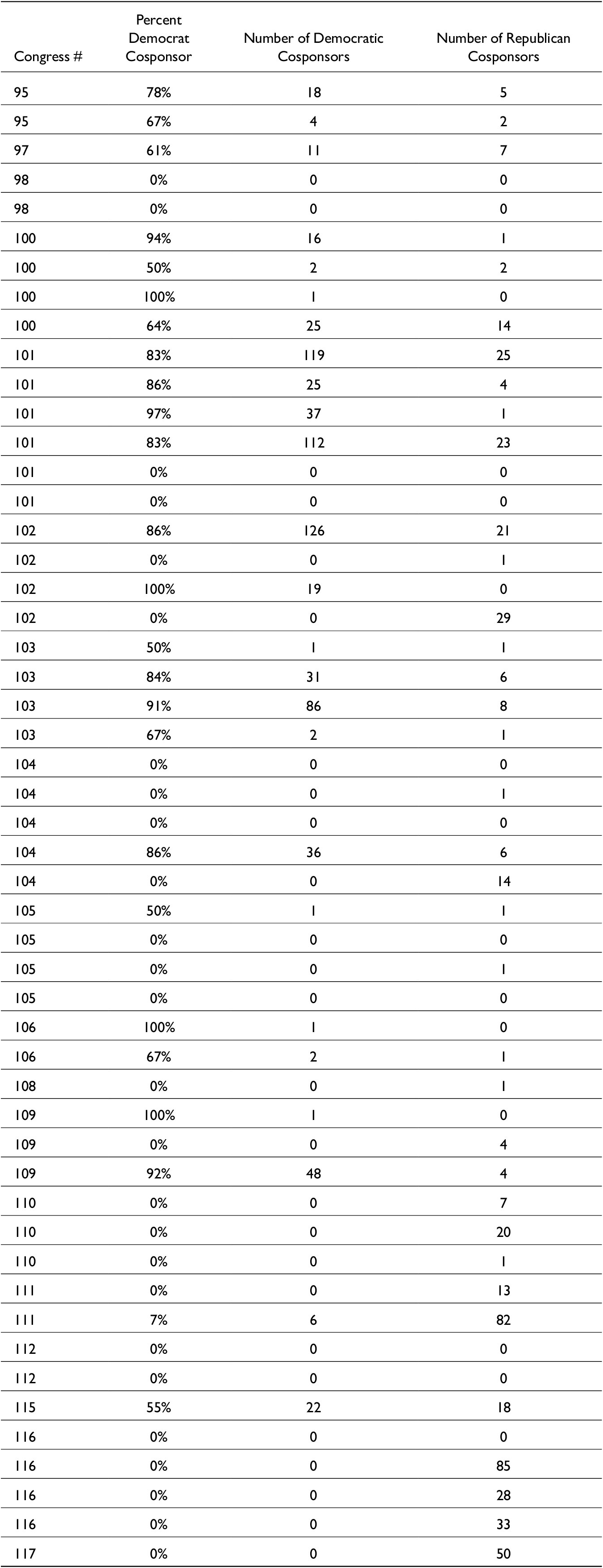

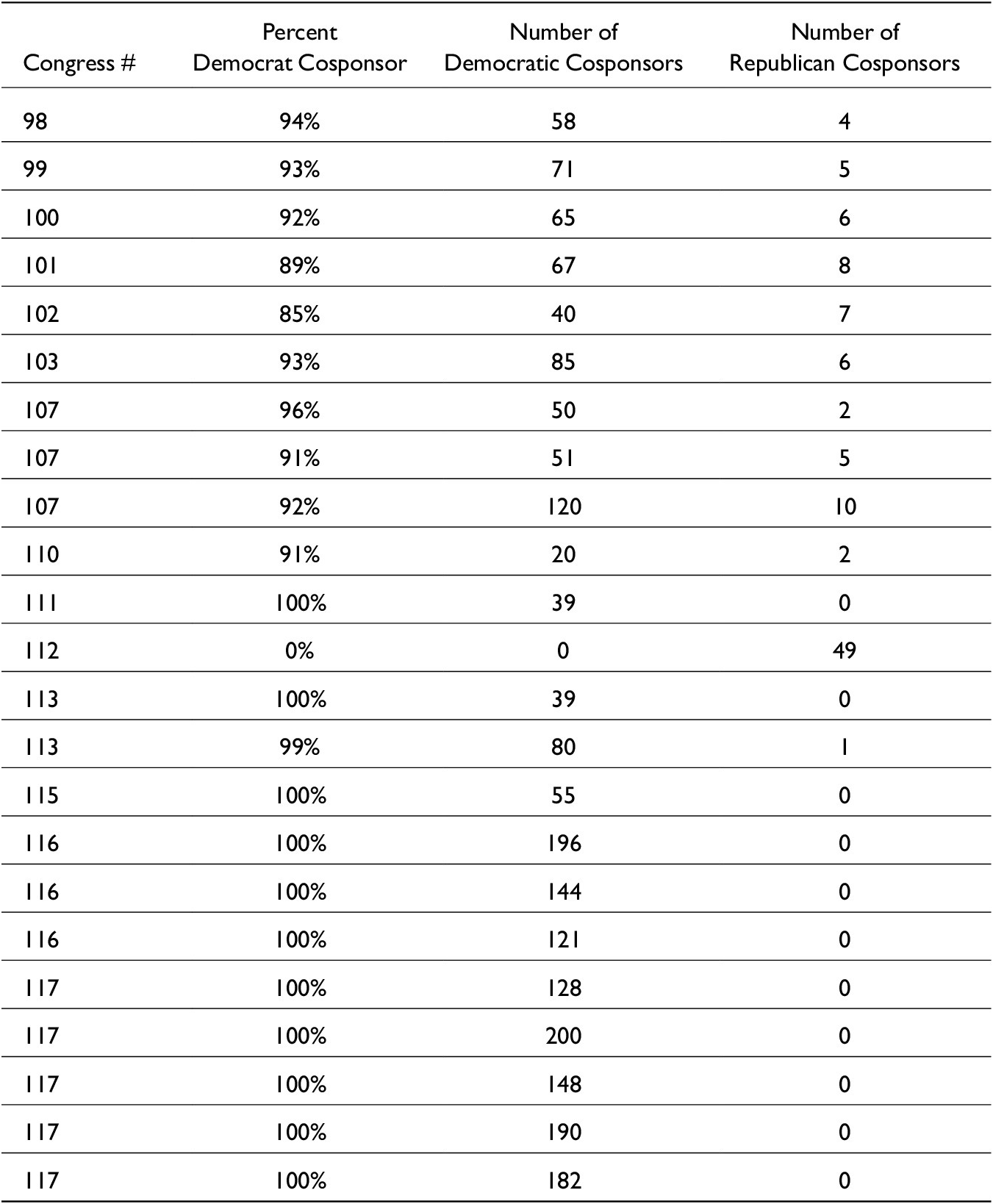

To best understand how these pro-abortion access and anti-abortion access positions become owned by the political parties, I look at bill sponsorship and cosponsorship. Tables 1 and 2 compare the number and party affiliation of U.S. foreign-policy bill cosponsors over time, showing patterns for anti- and pro-abortion-access bills, respectively. Table 1 reveals—surprisingly—that Democratic members of Congress made up a substantial share of the cosponsors of anti-abortion-access foreign policy bills in the earlier Congresses. Republicans did not dominate as cosponsors of such bills until after the 104th Congress.

Table 1. Support for anti-feminist foreign policy: anti-abortion access U.S. Foreign Policy Bill cosponsorship by Congress and political party, 1977–2022

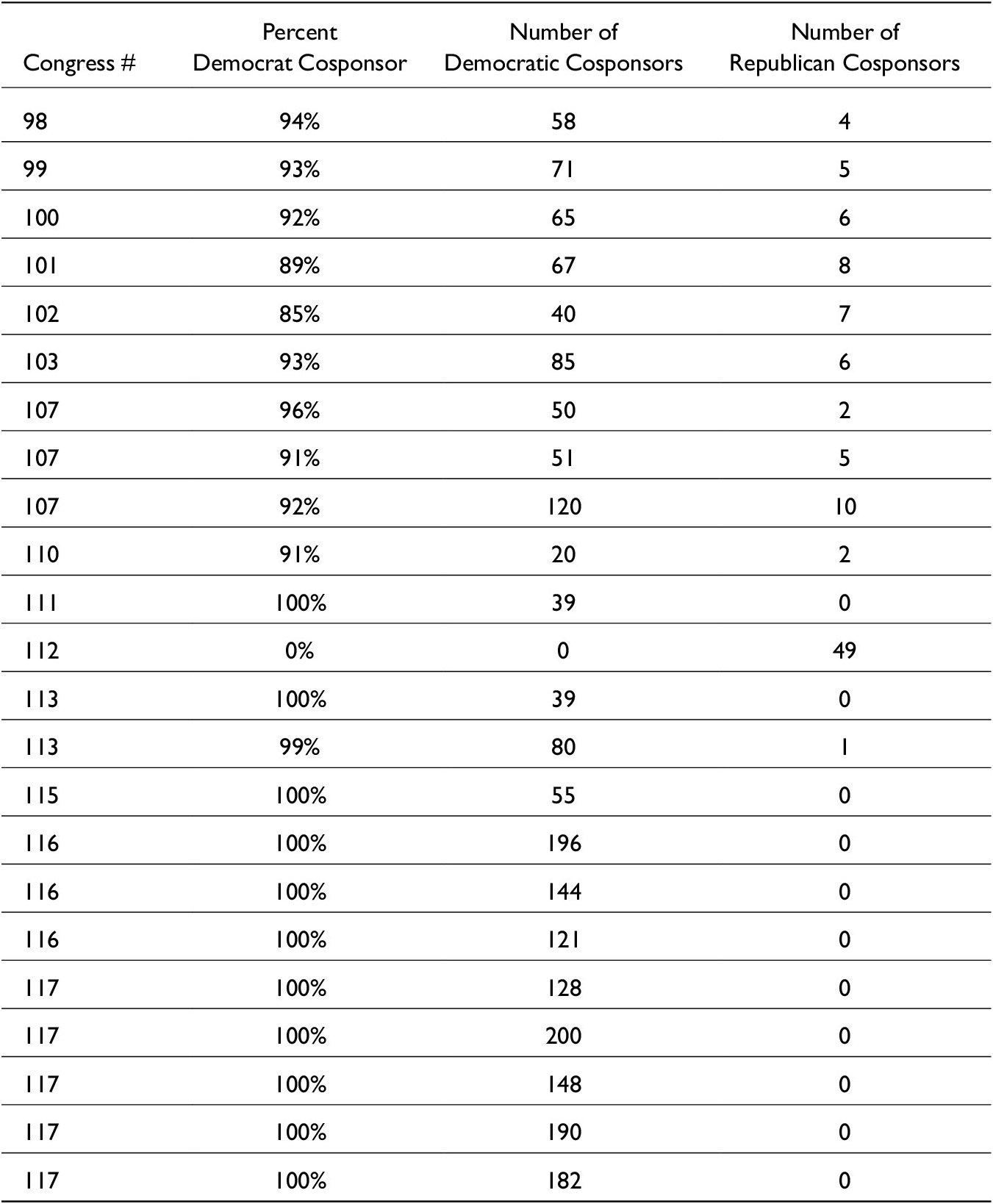

Table 2. Support for Feminist Foreign Policy: pro-abortion access U.S. Foreign Policy Bill cosponsorship by Congress and party, 1983–2022

Table 2 shows that, for pro-abortion-access foreign policy bills, House Republicans continued crossing the aisle as cosponsors somewhat longer than Democrats did on anti-abortion-access bills. Before the 111th Congress (2007–08), a few Republicans frequently signed on to support pro-abortion-access foreign policy bills. After the 111th Congress, however, only one such bill attracted a Republican cosponsor. For roughly the last fifteen years, pro-abortion-access foreign policy bills have been cosponsored almost exclusively by Democratic members of Congress.

Importantly, support for pro-abortion-access bills has built over the years as the number of Democratic cosponsors has increased. More members of the Democratic Party support these American feminist foreign policy bills as a policy priority. In the 98th Congress (1983–84), only fifty-eight Democratic House members signed on in support of pro-abortion-access foreign policy bills. Beginning with the 116th Congress (2019–20), the number of Democratic cosponsors has consistently exceeded 100, ranging from a low of 121 to a high of 200 in the 117th. Yet despite this widening support in Congress, none of the pro-abortion-access bills has passed the U.S. House of Representatives.

This analysis highlights several patterns in American foreign policy legislation. First, relatively few bills directly mention “abortion.” Of those that do, roughly half seek to restrict abortion access, one quarter aim to expand it, and one quarter focus on ending practices of coercive abortion. Second, partisan divisions have deepened over time. Democrats have expanded their support for these bills — from fifty-eight cosponsors in the 98th Congress to an average of 163 in the 117th. The Republican Party has not drawn comparable numerical support for its anti-abortion initiatives. Finally, the number of pro-abortion-access bills has risen in recent years, outpacing anti-abortion bills and suggesting that the overturning of Roe v. Wade has heightened Democratic enthusiasm for pro-abortion-access foreign policies.

Abortion in Foreign Policy Politics in the 115th Congress (2017–18)

Three case studies of American foreign policy bills that target global women’s rights, or “women’s foreign policy,” offer a unique perspective on the foreign policy legislative process, showing how partisan abortion politics shaped foreign policy outcomes, sometimes in surprising ways. In the 111th Congress (2007–08), under a Democratic Party majority Congress, three women’s foreign policy bills with widespread support all failed to pass (Angevine Reference Angevine2021b). In the 115th Congress (2017–18), in contrast, when Republicans held the majority, three women’s foreign policy bills were able to surmount this hurdle and pass into lasting statute. I focus on the activities of the women’s foreign policy entrepreneurs behind these bills, those in Congress working on their policy objectives that target the rights of women in foreign policy as policy entrepreneurs (Mintrom Reference Mintrom1997; Wawro Reference Wawro2010) and the respective issue advocates.

This qualitative case study analysis shows how the women’s foreign policy entrepreneurs were able to navigate the abortion politics labyrinth through two strategies: (1) adopting silo tactics on the representation of women’s interests (isolation) and (2) creating a Republican anti-abortion buffer zone through bill sponsorship (repudiation). The need for these strategies reveals that anti-abortion advocates hold pervasive power over women-related foreign policy in the U.S., even when the policies themselves — Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) Act of 2017, the Women’s Entrepreneurship and Economic Empowerment (WEEE) Act of 2018, and the Protecting Girls’ Access to Education in Vulnerable Settings Act of 2018 — do not explicitly include language about abortion.

Although women and men from both political parties were involved in these women’s foreign policy discussions during the 115th Congress, Republicans were the lead sponsors on all three bills that passed. Indeed, two of these sponsors were Republican men, historically a group that has been more active as anti-feminist policy entrepreneurs (Swers Reference Swers2002; Reference Swers2013). A closer look at the policy discussions leading up to the adoption of these laws, however, shows how concerns about abortion restrict and constrain feminist foreign policymaking in the U.S., with implications for women around the world.

The WPS Act of 2017 mandates the creation of a government-wide strategy to increase the participation of women as peacekeepers and negotiators. It stipulates training for diplomats, development professionals, and security personnel to support the inclusion of female negotiators, mediators, and peacekeepers. It also sets up reporting requirements related to women’s participation in federal agencies, including the Departments of State, Defense, Homeland Security, and USAID. At its core, the WPS Act fundamentally expands the U.S. security infrastructure to prioritize women’s participation.

In the 115th Congress, Representative Kristi Noem (R-SD) introduced the WPS Act on May 17, 2017, and garnered 16 cosponsors (11 Republicans —8 men and 3 women; 5 Democrats — 3 men and 2 women). Noem had sponsored the bill in the 114th Congress when it passed the House but not the Senate. Building on that success, the WPS Act of 2017 passed the House on June 20, 2017. On the Senate side, the lead sponsor of the WPS Act was Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), the only woman on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, joined by Senator Shelley Capito (R-WV). The Senate version was introduced on May 16, 2017, had four cosponsors (1 Republican woman, 1 Republican man, and 2 Democratic men), and passed on August 3, 2017. President Trump signed the WPS Act of 2017 into law on October 6, 2017.

The WEEE Act of 2018 had never been introduced in a prior congressional session. This bill required that 50 percent of all USAID funds for medium-sized businesses be allocated to women or to the very poor, moving far beyond micro-credit. In addition to directing millions of USAID dollars to women-owned businesses in foreign countries, the WEEE Act also specified requirements for comprehensive gender analysis of all USAID funding.

On the House side, the WEEE Act of 2018 was sponsored by House Foreign Affairs Committee Chair Edward Royce (R-CA), alongside Representative Lois Frankel (D-FL), co-chair of the bipartisan Congressional Caucus on Women’s Issues. The Act had 12 cosponsors in the House (6 Democrats — 4 women and 2 men; 6 Republicans — 3 women and 3 men). The WEEE Act was first introduced to the U.S. House on April 12, 2018, marked up in committee on April 17, and passed a few months later on July 17, 2018. The bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate on July 19, 2018, where it faced greater resistance. It was passed out at the end of the congressional session on December 21, 2018, and signed into law on January 9, 2019.

The Protecting Girls’ Access to Education in Vulnerable Settings Act of 2018 highlights the importance of girls’ education for advancing global development objectives — a long-standing focus of American foreign policy. Activist Malala Yousafzai amplified U.S. attention to this issue when she was shot in the head on October 9, 2012, by Pakistani militants for trying to take a test as a girl. At its core, this bill ensures adequate education provisions for girls and boys at refugee sites. According to Representative Bill Chabot (R-OH), lead sponsor of the bill, the Act “encourages the U.S. government to make the education of children in areas of conflict a priority in their assistance efforts and directs the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development to increase the access of displaced children, especially girls, to educational, economic, and entrepreneurial opportunities” (Press Release, May 15, 2017).

The bill was first introduced in the 114th Congress (2015–16) by Representative Chabot (R-OH) and did not pass. In the 115th Congress (2017–18), Chabot remained the principal author but teamed up with Democratic congresswoman Robin Kelley (D-IL) as the lead cosponsor. The Girl Up! UN campaign for girls’ access to education and other international NGOs, such as the Borgen Project and Catholic Relief Services, were the primary advocacy groups behind the bill. In the 115th Congress, fifty House members signed on in support of the bill as cosponsors (37 Democrats — 17 women and 20 men — and 13 Republicans — 4 women and 9 men). The House bill was introduced on May 11, 2017, marked up in committee on July 27, 2017, and passed on October 3, 2017.

Similar to the WEEE Act, the bill did not move as swiftly through the Senate as it did in the House. Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) was the lead sponsor, with Robert Menendez (D-NJ) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) as the lead cosponsors. The Senate version was introduced on July 19, 2017, but did not pass out of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC) until July 26, 2018. The Act then went to the Senate floor for a roll-call vote on December 12, 2018, where it passed 362–5. President Trump signed the Act into law on January 14, 2019. Like the House bill, the Senate bill cosponsors leaned Democratic (14 Democrats — 2 women and 12 men — and 2 Republicans — 1 woman and 1 man). Domestic abortion politics had long thwarted the legislative process surrounding all women’s foreign policy (Angevine Reference Angevine2021b). I suggest that these three bills be passed through this gender politics legislative labyrinth by adopting two strategic political tactics: isolation and repudiation.

Isolation: Silo from Reproductive Health

How did these women’s foreign policy bills pass during the first Trump administration, at a time when Republicans were a strong force in both houses of Congress? One explanation is that certain global women’s rights — such as the right to participate in peace talks, to be part of the market economy, and to have access to education — sare less controversial than reproductive health or abortion access. According to one issue advocate, such policy areas are “never going to be a political fight the same way fights on abortion are.”

Aware of these dynamics, numerous advocates detailed in the interviews how they worked to silo their targeted bills from the broader intersectional global women’s rights agenda. They felt that isolating the issue would increase the chance of bill passage in Congress. Yet this tactic had been attempted in the past with little success. In the 111th Congress (2009–10), anti-abortion advocates were effective at stopping any foreign policy bill that mentioned women by connecting the bill to abortion — even bills on preventing child marriage of girls (Angevine Reference Angevine2021b). However, in the Republican-majority 115th Congress, policy proponents were effective at divorcing abortion from other issues affecting women through consistent, explicit separation.

This was not easy. In reference to the WPS Act, one issue advocate described the difficulty of convincing some leaders of U.S. global feminist advocacy groups to refrain from pushing for the legislation. Their public feminist support, according to the respondent, could ignite anti-abortion advocates and prevent progress. The advocate explained:

We all just understood that’s just the name of the game… We all support international family planning, reproductive health. So, I spent a lot of time talking to Planned Parenthood and others also thinking through the bill. We don’t want to throw that agenda under the bus, but we also want to de-link the two (personal Interview with Author, 2018).

A legislative staffer echoed this sentiment, noting that they had to convince interest groups that many compromises were necessary for the legislation to move forward. According to the Democratic staffer, while advocates “didn’t love” separating WPS from reproductive health, they “understood that that was a hit that they had to take, in exchange for getting the bill passed… in exchange for the greater good, essentially” (Interview, 2018).

The threat of abortion politics also loomed in the background for other policy proponents. Referring to Mexico City, issue advocates expressed serious concern that anti-abortion members of Congress might try to add an anti-abortion amendment to the WPS Act as it advanced in Congress. One respondent shared:

I was worried about Mexico City… I was really worried about that being an amendment. We had some discussions about where we would come out on that. As an organization, we would not have supported the bill if it was attached… So fortunately, though, we had a lot of supportive Republicans interested in just keeping this separate. (Interview 2018)

Similarly, legislative staff members working on the WEEE Act lamented the pervasiveness of abortion politics in any policy conversation about foreign women. Unless one could silo off and isolate a specific women’s issue, all women’s issues would be conflated with abortion politics and thus caught in a gridlock between feminist and anti-feminist policy goals. In the words of one Democratic staffer:

There are a lot of people in the world, and to an extent in both parties, but more on the Republican side, who hear women’s issues as choice. Like women’s issues equals abortion, which is just [expletive] nonsense. (Interview 2018)

Another Republicans staffer observed:

Abortion, it’s like the elephant in the room. Every time you work on a women’s anything bill, which is ridiculous, but it’s reality. And it certainly was for this bill, the WEEE ACT that is. (Interview 2018)

Beyond concerns that policy references to gender-based violence would be interpreted as pro-abortion, a further anti-feminist objection emerged in the case of the WEEE Act, which explicitly calls for a “gender analysis” of U.S. foreign-aid spending. Some opponents of the bill used it as a platform to test anti-transgender policy language, seeking to replace the term “gender” with “biological sex defined as man and woman,” according to one Republican staffer.

In this instance, WEEE Act policy proponents again had to silo their objectives from the expanding anti-feminist, anti-abortion, and anti-transgender foreign-policy platform. A few Republican senators placed holds on the WEEE Act over these concerns about “gender analysis.” Ultimately, Special Adviser to the President Ivanka Trump persuaded these Republican legislators to lift their holds and allow the legislation to progress in the Senate as originally written (Saldinger Reference Saldinger2018).

Isolating the bill from anti-feminist, anti-abortion politics was important even for the U.S. foreign policy focused on girls and education. An issue advocate noted how, when working on the original bill language, they worked to steer clear from references to gender-based violence because the anti-abortion advocacy coalition had “created a narrative where response to gender-based violence includes backdoor authorization for abortion.” They noted how their explicit and direct emphasis on girls’ education meant that members of Congress were “more likely to take a look at it” (Interview, 2018).

In addition, policy proponents were aware of the need to separate their bills from any connection to the global women’s rights movement or the United Nations (UN). Even though many of the policy objectives for these bills were drawn from UN global women’s rights principles, my respondents claimed that any reference to the UN would threaten support from members of Congress. One advocate argued that support for these UN treaties could only occur after certain policy equilibria were reached internally: “I don’t think we would ever get to a point where we could ratify CEDAW [Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women], unless we definitively came to some kind of consensus on the abortion issues or violence issues” (Interview, 2018).

In sum, the policy language in each of these cases reflects strategic tactics to isolate the policy issue from any potential association with reproductive health and/or abortion access. Even though many of the policy advocates behind these bills believed in the necessity of global women’s access to abortion, they described the need to distance these bills from this polarizing, pervasive issue in order to gain bipartisan traction. Nonetheless, the siloed policy language alone did not catalyze political momentum: having anti-abortion Republican members of Congress as lead sponsors of these pieces of foreign policy legislation served as a buffer to quell doubts and improve their chances of success.

Repudiation: Anti-Abortion Lead Sponsors

The second tactic deployed by the women’s foreign-policy entrepreneurs of the 115th Congress to move their bills through the anti-abortion thicket was to secure leadership support from anti-abortion Republican members of Congress. In interviews, policy proponents noted that the congressional reputation of key sponsors and cosponsors affected their ability to advance the legislation. With anti-abortion Republicans as lead sponsors, other Republicans believed they could support this foreign-policy legislation on women without betraying their anti-abortion constituents.

The qualitative research revealed that anti-abortion members of Congress often used abortion policy to signal their opposition to — or support for — other policies, leveraging their positions on such bills to strengthen their abortion-policy scorecards. In their view, these calculations were vital for retaining the backing of anti-feminist constituents. As a result, Republican members of Congress (and some anti-abortion Democrats) showed a high degree of risk aversion toward any policy on women’s rights. Interviews suggested that an anti-abortion “buffer zone” of Republican sponsors was crucial for building the bipartisan support needed to pass each piece of women’s foreign-policy legislation.

One Republican legislative staff member recalled that other Republican staffers called their office to confirm that the proposed legislation — specifically the WPS Act — had nothing to do with abortion. The staffer explained that their boss’s anti-abortion reputation increased trust and support. Other staffers echoed this point about how to approach any policy issue touching on gender. As the Republican staff member recounted:

When we first introduced the bill, I got a call from [Member of Congress’s office], “Does it have anything to do with abortion?” We were like, “No, man, there’s no health care at all in here,” and they’re like, “Oh. Okay, yeah, it’s fine, man. That’s totally cool.” They couldn’t even wait; they had to call and find out immediately. (Interview 2018)

Respondents also noted the importance of having more than pro-abortion-access Republicans as cosponsors. Issue advocates working on the WPS Act explained how they were working to combat this apprehension from Republicans. According to one issue advocate:

If Susan Collins [R-ME] was the only Republican we have on board, that’s going to be really scary because she’s pro-choice. Now, one might say what does she have to do with the Women’s Security Act? But people fear women, and that’s what they think. And that was an issue. (Interview 2018)

Legislative staff and issue advocates working on the WEEE Act detailed how the anti-abortion advocacy coalition had managed to halt the legislative progress on a popular human trafficking bill. The trafficking bill had successfully passed out of committee by a positive vote of unanimous consent, with bill language “restricting U.S. funding for abortions,” according to Republican legislative staff. However, when the trafficking bill came to the general House floor for a vote, some Republican members wanted even stronger anti-abortion policy language added, which some Democratic members opposed. The bill then ended up failing to pass the chamber, having a chilling effect. As a Democratic staffer observed:

We didn’t pass the human trafficking bill and ever since then, all it takes is a whiff of healthcare or women’s issues and you get certain people who oppose it, it’s the same thing. (Interview, 2018)

Notably, the WPS Act was sponsored by Representative Kristi Noem (R-SD), who is staunchly anti-abortion. The WEEE Act was sponsored by Representative Ed Royce (R-CA), who is strongly anti-abortion. And the Protecting Girls’ Access to Education in Vulnerable Settings Act was sponsored by Representative Steve Chabot (R-OH), who is vehemently anti-abortion. As one Republican staffer mentioned, “I don’t think Chabot would have led the bill if there was any angle that touched on abortion or abortion access” (Interview, 2018).

Further, respondents highlighted how having support from organizations that were anti-abortion, such as Catholic charities, signaled that the bill would not advance reproductive access. With anti-abortion members as the lead sponsors, Republicans were less wary of lending their support to the legislation, affecting who signed on as bill cosponsors as well as broader support for the proposed legislation in the chamber. The anti-feminist foreign policy position on abortion thus permeated any policy conversation on global women’s rights in the U.S. Congress.

Feminist Criticisms of Isolation and Repudiation

The tactics of isolation and repudiation were not always well received by the global feminist advocacy coalition in and beyond Congress. While they helped increase policy support from some Republicans, they also reduced support among some Democrats. Additionally, sectors of the broader global feminist community were uncomfortable with the siloing of select global women’s issues and rights, viewing this as a way to give Republicans victories on a policy terrain where Democrats typically held the advantage.

Within the global feminist policy community, according to numerous interviewees, the need to balance the global feminist and global anti-feminist constituencies reduced the focus on women’s human rights and underscored partisan competition. One issue advocate observed:

What folks in the community were saying, and in the public really was like, why would we give this administration a fig leaf to say, oh, they’re doing something good for women when they have a hundred different policies that are limiting women’s rights to abortion, to health care, to whatever. All of the crappy things that they’re doing, why would we give them this? (Interview, 2018)

Activists described, further, how they feared that drawing greater support for these policies could be more harmful than helpful. By way of example, one issue advocate detailed how they had to convince a grassroots feminist organization not to raise a particular policy issue when lobbying because they felt that it could alarm anti-abortion policy advocates. When asked if grassroots organizers “could be helpful,” their response was:

“Maybe, but maybe not. Why mess with a good thing right now?” And I didn’t want to make this bill a massive thing, because then it gets connected to Mexico City and family planning issues. And then it’s done. (Interview, 2018)

Despite these ongoing concerns, the strategic political tactics of isolation and repudiation helped circumvent the anti-abortion, anti-feminist policy blockade, opening the way for the passage of three women-related foreign policy bills into lasting statute.

Abortion Politics, Feminism, Anti-Feminism, and American Foreign Policy

In this article I analyze the political history of U.S. abortion foreign policy, showing how the U.S. President and Congress have shifted their positions over time. American politicians have used foreign policy as a venue to advance their ideological views on abortion with relative impunity. After presidents are inaugurated, they often act quickly on abortion access in U.S. foreign policy, gratifying their feminist or anti-feminist domestic audiences on this highly charged, foundational issue. As a result, presidents have destabilized funding sources for international reproductive health since 1984.

As for the legislative branch, efforts by anti-abortion policy entrepreneurs are well known to constrain the progress of feminist foreign-policy legislation. My analysis of congressional data shows that, of all U.S. foreign-policy bills targeting abortion between 1973 and 2022, the majority are anti-abortion. Only in the most recent Congresses has the number of proposed pro-abortion-access bills grown in U.S. foreign policy. None of these bills ever passed.

Additionally, my case studies of the three successful women’s foreign policy bills in the 115th Congress (2017–18) reveal that the anti-abortion advocacy community remains the most significant obstacle to advancing women’s foreign policy legislation. Even when Republicans — an arguably anti-abortion political party at the time of this study — held the majority in the U.S. House and Senate and controlled the presidency, women’s foreign policy entrepreneurs had to isolate their bills from anything that might be construed as pro-abortion access, even issues such as gender-based violence and economic development.

Furthermore, evidence suggests that these arguably “feminist” foreign-policy bills could not have advanced without lead sponsors who were vocally anti-abortion, thereby repudiating any connection to a comprehensive feminist political representation of global women’s interests. This invites a deeper investigation into the broader question of what counts as feminist foreign policy (Bergman Rosamond Reference Bergman Rosamond2020). These three successful women’s foreign-policy bills did not move the needle on abortion foreign policy in the United States, yet their passage came only through concessions to the powerful anti-abortion advocacy coalition.

When it comes to abortion access in U.S. domestic policy, the anti-abortion advocacy coalition has recently experienced significant success. The overturning of Roe v. Wade in the 2022 Dobbs decision facilitated waves of anti-abortion policies at the state level, with twelve states effectively banning abortion access outright (Guttmacher Institute 2025). Based on this study, I suggest that much of the domestic success of the anti-abortion advocacy coalition was sustained by its effective impact on American foreign-policy legislation, beginning with the Helms Amendment in 1973. The Helms Amendment, which prohibits the use of federal foreign aid for abortion in foreign countries, laid the policy groundwork for the Hyde Amendment of 1976, which prohibits the use of federal domestic aid for abortion in the United States. In other words, American foreign-policy legislation has served as a space where anti-feminist policy ideas can be tested with impunity.

My findings suggest a similar pattern began with anti-transgender legislation. In 2015, the Center for Family and Human Rights (CFAM) nearly succeeded in blocking the passage of the WEEE Act because they believed that the use of the term “gender” was transgender inclusive, which they opposed. Since this anti-transgender political move nearly worked, this perhaps signaled an effective future anti-feminist policy target: transgender rights. In 2015, according to the Human Rights Campaign, there were 19 anti-transgender bills introduced at the state level in the U.S. In 2022, only seven years later, there have been more than 520 anti-transgender bills introduced (Peele Reference Peele2023). The U.S. anti-feminist advocacy coalition continues to learn from their successes and failures in American foreign policy.

Moving forward, U.S. feminist scholars and activists must note the growth of anti-feminist practices in American foreign policy. The “Big Boy’s Playpen” of U.S. foreign policy (Freedman Reference Freedman2015) remains, and as Leatherman (Reference Leatherman, Sue and Josephson2005) argues, a domain hostile to feminist concerns and a favorable arena for testing anti-feminist policy goals, since relatively few in the U.S. electorate pay attention. Yet these feminist and anti-feminist foreign-policy ideas have real effects on women’s lives internationally and within the U.S. Moreover, the persistent success of the anti-feminist advocacy coalition in foreign policy has arguably helped sustain its momentum in domestic policy. The lesson is clear: future investigations of feminist foreign policy must account for the constraints of domestic politics and the pervasiveness of anti-feminist advocacy coalitions in both domestic and foreign policy. Those seeking to advance feminist policy concerns at home should pay close attention to abortion politics and other anti-feminist policy goals playing out in foreign policy. As the concept of women’s rights has crossed national boundaries, so have the passions to advance and restrict them.