Introduction

Negative symptoms have been recognized as a key component of schizophrenia since its first descriptions [Reference Bleuler1–Reference Kraepelin3].

The conceptualization and descriptions of negative symptoms proposed by the 20th-century classic scholars [Reference Bleuler1–Reference Kraepelin3] included two aspects: loss of motivation and reduction of emotional expression. The introduction of classification systems and operational criteria for diagnosis in psychiatry contributed to de-emphasizing the role of negative symptoms as a core aspect of schizophrenia, most likely due to a poorer inter-rater reliability in their assessment, as compared to positive symptoms. In spite of the predominant trend, the focus on negative symptoms kept alive by few research groups enabled further progress in the field [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4–Reference Dollfus and Lyne6]. The last decades witnessed a huge increase in the attention on negative symptom conceptualization. Main driver of the growing interest for negative symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia has been the evidence of their frequent occurrence and strong relationship with low remission rates, poor real-life functioning, and quality of life [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Marder and Galderisi5]. Large cross-sectional studies demonstrated that 50–60% of patients with schizophrenia have at least one negative symptom of moderate severity and approximately 10–30% of them experienced two or more, often enduring negative symptoms [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Bobes, Arango, Garcia-Garcia and Rejas7–Reference Stauffer, Song, Kinon, Ascher-Svanum, Chen and Feldman11]. Furthermore, 50–90% of subjects with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders show negative symptoms during their first episode of the illness [Reference Lyne, O’Donoghue, Owens, Renwick, Madigan and Kinsella12,Reference Lyne, Renwick, O’Donoghue, Kinsella, Malone and Turner13].

In the light of the strong impact on functional outcome and of the burden on patients, relatives, and health care systems, negative symptoms have become a key target of the search for new therapeutic tools. However, so far, progress in the development of innovative treatments has been slow and negative symptoms often represent an unmet need in the care of subjects with schizophrenia [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Dollfus and Lyne6,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Schooler, Buchanan, Laughren, Leucht, Nasrallah and Potkin15].

In 2005, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) developed the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) initiative, which promoted a consensus conference aimed to review data on the existence of separate domains within negative symptoms and initiated a process for the development of evidence-based measures to improve their assessment. After 15 years from the consensus statement, negative symptoms are still poorly assessed and even when they are caused by known and treatable factors, such as extrapyramidal side effects, they are rarely recognized and properly treated.

To fill in this gap, the Schizophrenia Section of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) proposed the development of a guidance paper aimed to provide recommendations for the assessment of negative symptoms in clinical trials and practice. The proposal was approved by the EPA Guidance Committee.

Methodology

Systematic literature search

The development of EPA guidance on the assessment of negative symptoms followed the standardized methods, according to the European Guidance Project of the EPA and to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), as described in previous publications [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rossler16–Reference Gaebel and Moller20].

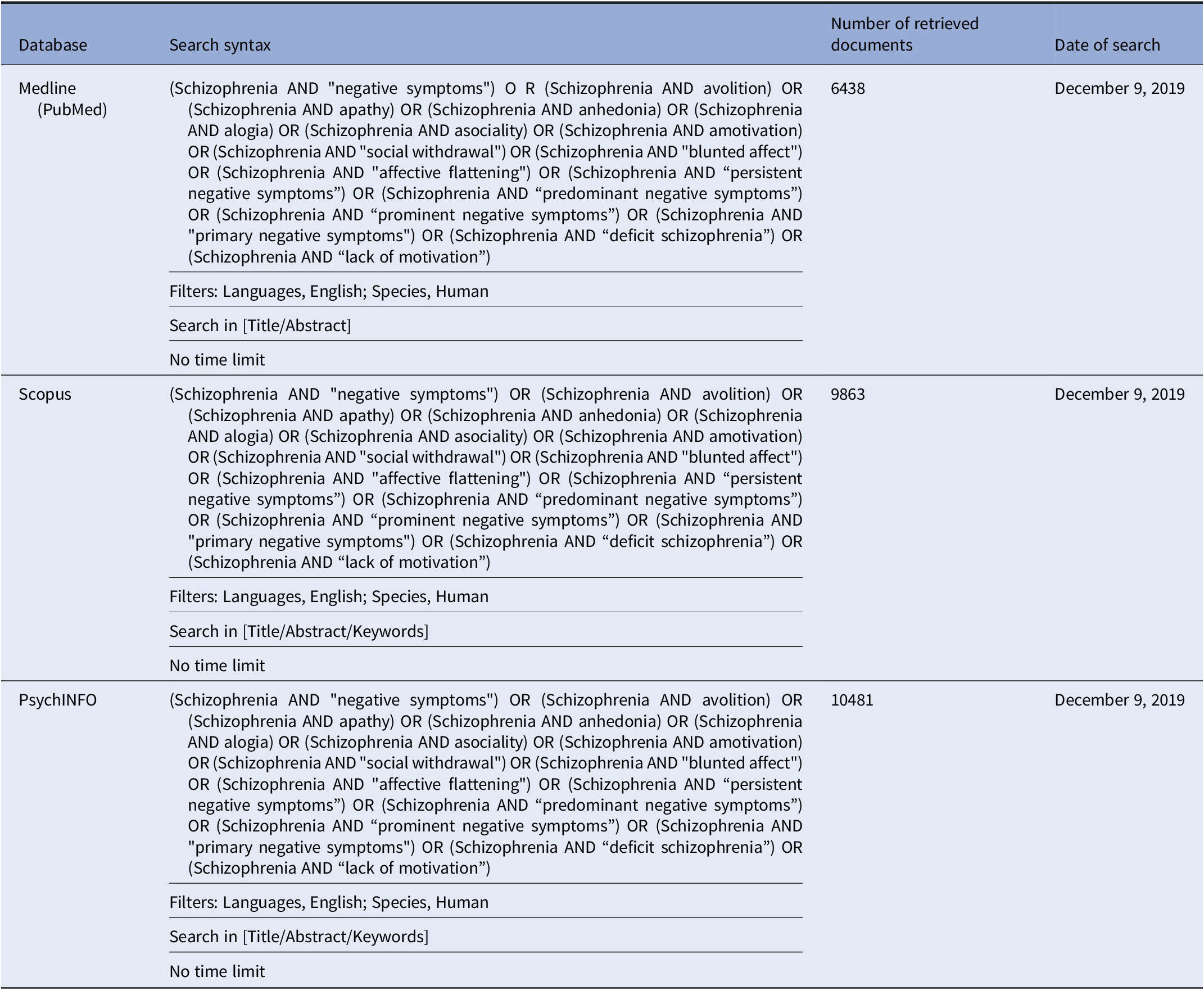

In brief, we performed a comprehensive literature search on the assessment of negative symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia. The search has been run in three electronic databases: Medline (PubMed), Scopus, and PsycINFO with no time limit, in order to ensure that it was as comprehensive as possible (Table 1).

Table 1. Systematic search strategies.

Studies were selected according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria as follows:

Inclusion criteria

1. meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, cohort study, open study, descriptive study, expert opinion, concerning conceptualization, and assessment of negative symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia according to the search terms cited in Table 1;

2. studies published in English;

3. studies carried out in humans;

4. studies published in journals indexed in Embase or Medline.

Exclusion criteria

1. duplicates, comments, editorials, case reports/ case series, theses, proceedings, letters, short surveys, and notes;

2. studies irrelevant for the topic, including studies relevant to the treatment of negative symptoms;

3. studies concerning exclusively pathophysiological mechanisms of negative symptoms (those reporting imaging or electrophysiological or other biomarker correlates of negative symptoms);

4. unavailable full-text;

5. studies that do not meet inclusion criteria.

Discrepancies in the selection and any change in methodology have been discussed in advance with the whole group. In particular, a deviation from the methodology has been taken for the following sections: “Assessment of negative symptoms in first episode psychosis (FEP) patients” and “Assessment of negative symptoms in clinical high risk (CHR) individuals”.

With regard to FEP studies, an additional search on Medline was performed on December 18, 2019 following the search strategy described in Table 1 and the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above, replacing the term “schizophrenia” with the term “first episode schizophrenia”. The literature was then screened focusing on the topic “assessment” in FEP. Due to the enormous amount of literature using the original summed scores of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), these studies have been excluded and have been represented by meta-analyses only. Studies described individually in paragraph 4.2 used factor models or sub-scores from PANSS or SANS, or other assessment instruments, or focused on primary negative symptoms, persistent negative symptoms, or deficit syndrome (DS). Of the relevant references for this topic, 23 studies had been already included in the original search.

With regard to CHR studies, an additional search on Medline was performed on December 16 and 17, 2019 following the search strategy described in Table 1 and the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above, replacing the term “schizophrenia” with the terms “ultra-high risk psychosis”; “clinical high risk psychosis”; “prodromal psychosis”. To narrow the search, only intervention studies using a negative symptom outcome were included. Of the relevant references for this topic, 17 studies had been already included in the original search.

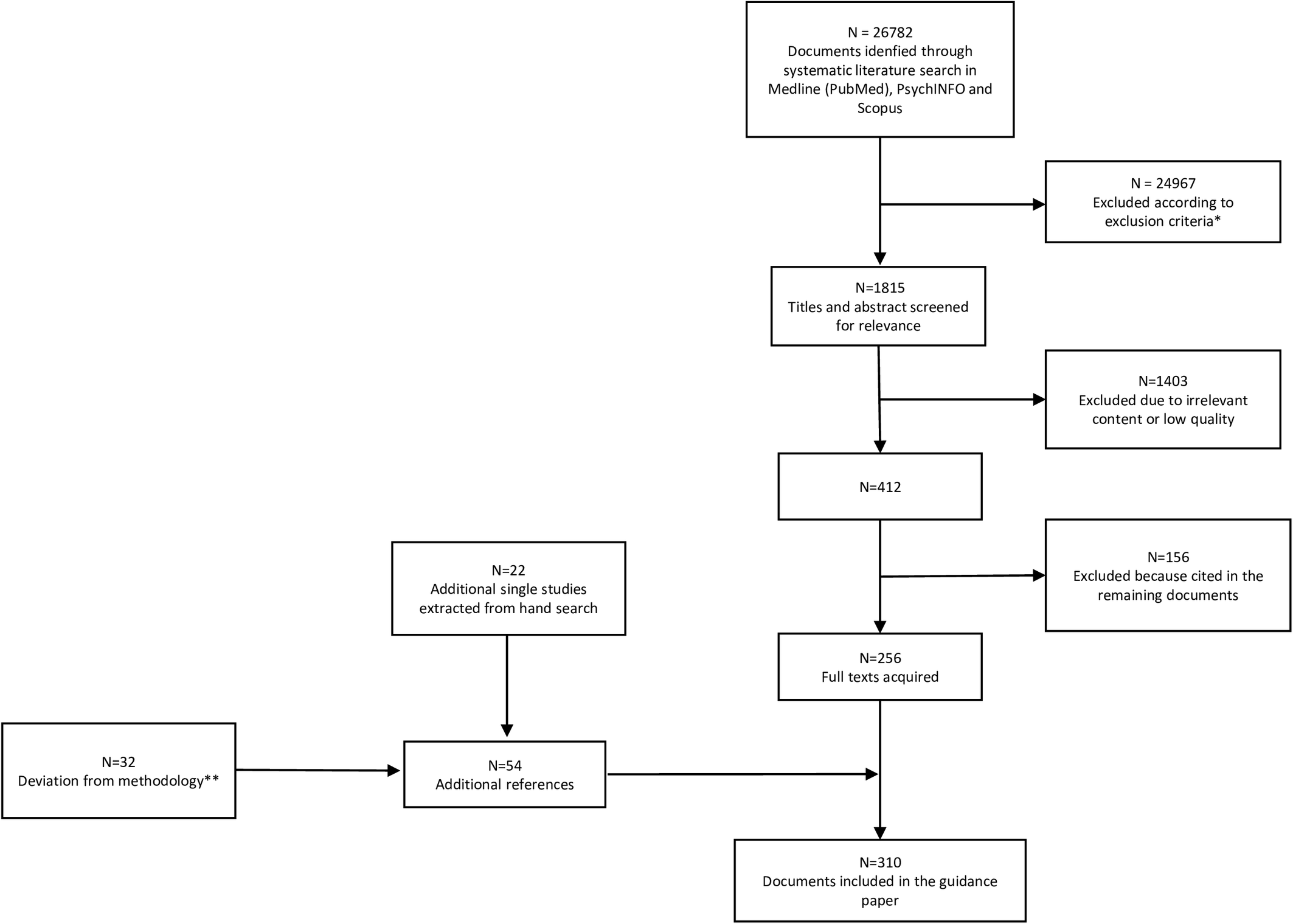

Details of the selection process are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of studies retrieved in the systematic literature search.

*11905 duplicates; 1826 studies other than meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, cohort study, open study, descriptive study, expert opinion; 843 studies published in journal not indexed in Embase or Medline; 2895 studies on pathophysiological mechanisms of negative symptoms; 5813 articles not related to any topic; 1527 articles related to the treatment of negative symptoms; 158 studies conducted in animals.

**The deviation from the original search regarded the Sections: “Assessment of negative symptoms in First Episode Psychosis patients” (N = 8; the other 23 had been already included in the 256 documents of the original search) and “Assessment of negative symptoms in clinical high risk individuals” (N = 24; the other 17 had been already included in the 256 documents of the original search).

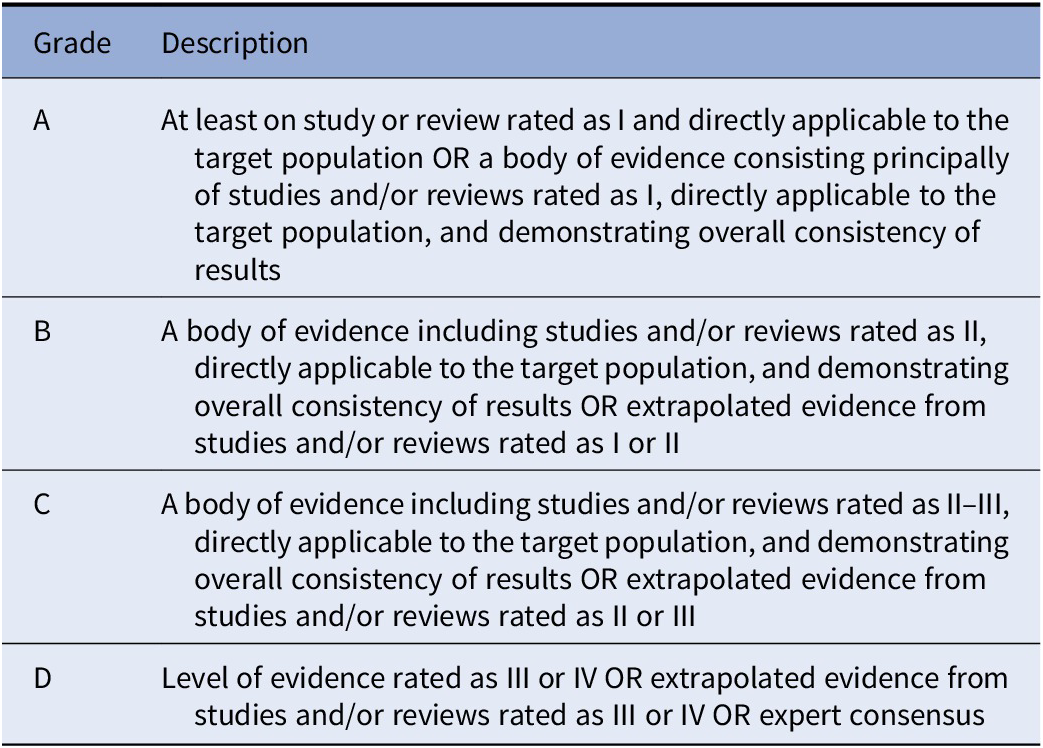

Included studies have been graded for the level of evidence, according to the previous literature [Reference Gaebel and Moller20].

For all documents, evidence grades were assigned according to Gaebel et al., 2017 [Reference Gaebel, Grossimlinghaus, Mucic, Maercker, Zielasek and Kerst21] (Table 2). Based on the evidence level of the included studies, recommendations were developed by three authors (SG, AM, and SD) and reviewed by all coauthors. Discrepancies in the ratings were resolved by discussion among all coauthors. Each recommendation level was then graded following Gaebel et al., 2017 [Reference Gaebel, Grossimlinghaus, Mucic, Maercker, Zielasek and Kerst21] (Table 3).

Table 2. Grading of evidence.

Note. Modified from Gaebel et al., 2017 [Reference Gaebel, Grossimlinghaus, Mucic, Maercker, Zielasek and Kerst21] .

Table 3. Grading of recommendations.

Note. Modified from Gaebel et al., 2017 [Reference Gaebel, Grossimlinghaus, Mucic, Maercker, Zielasek and Kerst21].

Conceptualization

Based on the review of data relevant to the construct validity of negative symptoms [Reference Blanchard and Cohen22], the NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms [Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23,Reference Kirkpatrick and Fischer24] identified five main domains of negative symptoms: anhedonia, avolition, blunted affect, alogia, and asociality [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Marder and Galderisi5,Reference Blanchard and Cohen22,Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23]. A brief description of each symptom domain according to the consensus statement is provided in Box 1.

Box 1. Definition of negative symptoms based on the NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement [Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23].

✓ Avolition: a reduction in the initiation and persistence of goal-directed activities due to a lack of motivation.

✓ Anhedonia: a reduction in the experience of pleasure during the activity (consummatory anhedonia) and for future anticipated activities (anticipatory anhedonia).

✓ Asociality: a reduction in social interactions due to a reduced drive to form and maintain relationships with others.

✓ Blunted affect: a reduction in the expression of emotion in terms of facial and vocal expression, as well as body gestures.

✓ Alogia: a reduction in quantity of words spoken and amount of spontaneous elaboration.

Understanding the possible associations between these domains has important implications in the design of clinical trials. For instance, if we assume that these domains represent a single construct with the same neurobiological underpinnings, they should respond to the same treatment, and a separate assessment of each of them would be redundant. On the contrary, if these domains are independent from each other or cluster into a limited number of factors, they might respond differently to treatment, and therefore a separate assessment of each of the domains or factors would be necessary [Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23]. The consensus statement suggested that, although the five negative symptom domains were interrelated, there was an important degree of independence between them. In the light of the definitions of the five domains, the development of new instruments that could properly assess them was recommended. In fact, the two most used scales, the SANS [Reference Andreasen25] and the PANSS [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler26], include aspects that are not part of negative symptom domains, do not allow the differentiation between anticipatory and consummatory anhedonia, and only focus on patient’s behavior, failing to assess subject’s internal experience, that is crucial for the evaluation of experiential deficits, such as anhedonia, avolition, and asociality [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Marder and Galderisi5,Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23,Reference Mucci, Galderisi, Merlotti, Rossi, Rocca and Bucci27–Reference Kring, Gur, Blanchard, Horan and Reise30]. Based on these recommendations, two new instruments were developed, the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS) and the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS) [Reference Kirkpatrick, Strauss, Nguyen, Fischer, Daniel and Cienfuegos28–Reference Kring, Gur, Blanchard, Horan and Reise30]. For a more detailed description of these instruments, please refer to the section on assessment.

Classification of negative symptoms

Negative symptoms represent a heterogeneous dimension, including symptoms with different causes and course, and, therefore, possibly requiring different treatment management [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Marder and Galderisi5,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Blanchard and Cohen22,Reference Carpenter, Heinrichs and Wagman31–Reference Moller41]. Different approaches to the negative symptom classification have been pursued in order to reduce their heterogeneity, not only in the research context, but also in the context of clinical trials.

Primary and secondary negative symptoms

The distinction between primary and secondary negative symptoms has important research and clinical implications [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Carpenter, Heinrichs and Alphs33,Reference Kirschner, Aleman and Kaiser35,Reference Kirkpatrick39,Reference Moller41]. Primary negative symptoms are thought to stem from the pathophysiological substrate underlying schizophrenia, while secondary negative symptoms might be caused by positive symptoms, depression, medication side effects, social deprivation, and substance abuse [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Carpenter, Heinrichs and Alphs33,Reference Kirschner, Aleman and Kaiser35,Reference Kirkpatrick39,Reference Moller41]. Secondary negative symptoms might be responsive to the treatment of the underpinning causes. For instance, negative symptoms secondary to depression or to positive symptoms might be responsive to antidepressant and antipsychotic treatments, respectively. In addition, the failure to differentiate primary from secondary negative symptoms is likely to hinder progress in innovative treatment discoveries [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4]. For a detailed description of differential diagnosis between primary negative symptoms and secondary ones, please consult the dedicated section.

The Deficit Syndrome

In 1988, Carpenter and colleagues introduced the concept of DS to characterize schizophrenia with primary and enduring negative symptoms [Reference Carpenter, Heinrichs and Wagman31]. The diagnostic criteria for the DS are reported in Box 2.

Box 2. Diagnostic criteria for the Deficit Syndrome [Reference Carpenter, Heinrichs and Wagman31, Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, McKenney, Alphs and Carpenter42].

(A) Presence of at least two out of the following six negative symptoms:

• Restricted affect: expressionless face, reduced expressive gestures, and diminished modulation of the voice.

• Diminished emotional range: the intensity and range of a person’s (subjective) emotional experience.

• Poverty of speech: reduced number of words used and the amount of information conveyed.

• Curbing of interests: the degree to which the person is interested in the world around him or her, both ideas and events.

• Diminished sense of purpose: the degree to which the person posits goals for his/her life; the extent to which the person fails to initiate or sustain goal-directed activity due to inadequate drive; the amount of time passed in aimless inactivity.

• Diminished social drive: degree to which the person seeks or wishes for social interaction.

(B) Presence of the above symptoms for at least 12 months including periods of clinical stability.

(C) The above symptoms are primary and not secondary to factors such as anxiety, drug effect, positive symptoms, mental retardation, and depression.

(D) The patient meets DSM (third or later edition) criteria for schizophrenia.

To date, the validity of this construct is supported by data collected in nine reviews [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, Ross and Carpenter32,Reference Galderisi and Maj34,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Kirkpatrick, Mucci and Galderisi38,Reference Kirkpatrick39,Reference Kirkpatrick and Galderisi43,Reference Buchanan44] (Table e1). The first review [Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, Ross and Carpenter32] supported the construct validity of the diagnosis, based on the cohesiveness of the symptoms used for its definition. Evidence was also provided that DS may represent a separate disease entity with respect to non-deficit schizophrenia (NDS), as the two entities differ in terms of signs and symptoms, course of illness, risk factors, biological correlates, and treatment response. These differences are not confounded by demographic features, antipsychotic treatment, severity of psychotic symptoms, or drug abuse. The review also supports the view that DS is not just a more severe form of the disease, as its characteristics and correlates are not just more of the same observed in NDS. The construct validity of the DS and the distinction between DS and NDS were also supported by subsequent reviews [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Galderisi and Maj34,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Kirkpatrick, Mucci and Galderisi38,Reference Kirkpatrick39,Reference Kirkpatrick and Galderisi43,Reference Buchanan44]. Notwithstanding the large consensus on the validity of this construct, some studies reported discrepant findings regarding differences between DS and NDS in terms of clinical and neurobiological features [Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Galderisi and Maj34,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Kirkpatrick, Mucci and Galderisi38,Reference Kirkpatrick and Galderisi43]. Three reviews [Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Kirkpatrick, Mucci and Galderisi38,Reference Kirkpatrick and Galderisi43] suggested that heterogeneity within the DS might complicate the diagnosis of DS.

The gold standard instrument to assess DS is the Schedule of Deficit Syndrome (SDS) [Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, McKenney, Alphs and Carpenter42]. The correspondence between negative symptoms included in the SDS with the MATRICS domains, as well as the assessment procedures are reported in Box 3.

Box 3. Negative symptoms included in the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS): correspondence with the MATRICS domains and assessment procedures [Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, McKenney, Alphs and Carpenter42].

SDS has a good inter-rater reliability within research groups, but requires extensive training, the use of different sources of information, and a careful longitudinal clinical evaluation to judge whether the observed negative symptoms are primary or secondary [Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, Ross and Carpenter32,Reference Galderisi and Maj34,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Kirkpatrick, Mucci and Galderisi38, 44]. The last information is not always available, especially in first episode patients [Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Galderisi and Maj34,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Buchanan44].

To increase the practicability of the DS diagnosis, a proxy [Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, Breier and Carpenter45–Reference Kirkpatrick, Amador, Flaum, Yale, Gorman and Carpenter47] was developed based on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) [Reference Overall and Gorham48], PANSS [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler26], or SANS [Reference Andreasen25]. The proxy allows the categorization of a large number of patients included in existing datasets in which the SDS was not used. However, in spite of its good sensitivity and specificity, several concerns on face validity of these measures have been raised [Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Strauss, Harrow, Grossman and Rosen49]. Another concern is relevant to the lack of temporal stability of the DS categorization made with the proxy, since a longitudinal study did not confirm the stability of the categorization (DS vs NDS) at 1-year follow-up [Reference Subotnik, Nuechterlein, Ventura, Green and Hwang50]. Given the above-mentioned limits, further studies are needed before the use of proxy measures can be recommended. These studies should assess negative symptoms with second-generation rating scales (BNSS and CAINS) and validate the specific cutoff for the DS/NDS categorization in different samples. The available evidence does not allow recommending the use of a proxy for the DS/NDS categorization.

Persistent, predominant, and prominent negative symptoms

In the light of the above observations, the consensus statement on negative symptoms suggested a focus on persistent negative symptoms, that is, negative symptoms that persist over time, including periods of clinical stability, despite an adequate antipsychotic drug treatment [Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23,Reference Buchanan44]. Criteria for persistent negative symptoms are reported in box 4.

Box 4. Criteria for “persistent negative symptoms” [Reference Buchanan44].

(A) Presence of at least moderate* for at least three negative symptoms, or at least moderately severe** for at least two negative symptoms.

(B) Defined threshold levels of positive symptoms, depression, and extrapyramidal symptoms on accepted and validated rating scales.

(C) Persistence of negative symptoms for at least 6 months.

*e.g., a score of 4 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) or a score of 3 on the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS); **e.g., a score of 5 on the PANSS or a score of 4 on the BNSS.

To date, the validity of this construct is supported by data collected in four reviews [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36,Reference Buchanan44] (Table e1), which suggest that the persistent negative symptom construct identifies a patient population larger than the one with DS and allows the control of potential sources of indirect changes of negative symptoms during the course of clinical trials. However, concerns on the persistent negative symptom construct have also been raised: the construct allows the use of any validated psychopathological rating scale, including those scales, such as SANS and PANSS, that include items not relevant to the negative symptom dimension; threshold for confounding factors (positive, depressive, and extrapyramidal symptoms) are not uniquely defined across studies [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36].

In clinical trials, as requested by regulatory agencies, in order to evaluate the efficacy of drugs for negative symptoms, other two concepts have been used: “predominant negative symptoms” and “prominent negative symptoms” (Boxes 5 and 6 for criteria). Neither construct included the evaluation of persistence over time of negative symptoms.

Box 5. Criteria for “predominant negative symptoms”

(A)

1. Presence of at least moderate* for at least three symptoms or at least moderately severe** for at least two symptoms [Reference Stauffer, Song, Kinon, Ascher-Svanum, Chen and Feldman51] or

2. Any score on PANSS negative subscale but at least 6 points greater than the PANSS positive subscale score [Reference Olie, Spina, Murray and Yang52] or

3. PANSS Negative subscale score of at least 21 and at least 1 point greater than the PANSS positive subscale score [Reference Riedel, Muller, Strassnig, Spellmann, Engel and Musil53] or

4. PANSS negative subscale score greater than the PANSS positive subscale score [Reference Rabinowitz, Werbeloff, Caers, Mandel, Stauffer and Menard54].

(B)

1. Positive PANSS subscale score less than 19, depressive and extrapyramidal symptoms lower than a defined threshold on a validated rating scale [Reference Stauffer, Song, Kinon, Ascher-Svanum, Chen and Feldman51] or

2. Severity of positive, depressive, and extrapyramidal symptoms not specified [Reference Olie, Spina, Murray and Yang52–Reference Rabinowitz, Werbeloff, Caers, Mandel, Stauffer and Menard54].

*e.g., a score of 4 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); **e.g., a score of 5 on the PANSS.

Box 6. Criteria for “prominent negative symptoms” [Reference Stauffer, Song, Kinon, Ascher-Svanum, Chen and Feldman51, Reference Rabinowitz, Werbeloff, Caers, Mandel, Stauffer and Menard54]

Presence of at least moderate* for at least three symptoms or at least moderately severe** for at least two symptoms on the PANSS negative subscale.

*e.g., a score of 4 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); **e.g., a score of 5 on the PANSS.

Three reviews [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36] analyzed data on “predominant negative symptoms” and only one of these reviews focused on “prominent negative symptoms” too [Reference Mucci, Merlotti, Ucok, Aleman and Galderisi36] (Table e1). These two concepts were also discussed during an international meeting, involving experts in the field, who did not reach an agreement on whether predominant or prominent negative symptoms should be considered in clinical trials [Reference Marder, Alphs, Anghelescu, Arango, Barnes and Caers55] (Table e1). Available evidence and expert opinions suggest the following: (a) both these concepts include a mixture of primary and secondary negative symptoms likely to fluctuate over time and possibly confounding the results of clinical trials; (b) no construct validity was supported; (c) no consensus was achieved on strategies to reduce the heterogeneity in the definition of predominant negative symptoms.

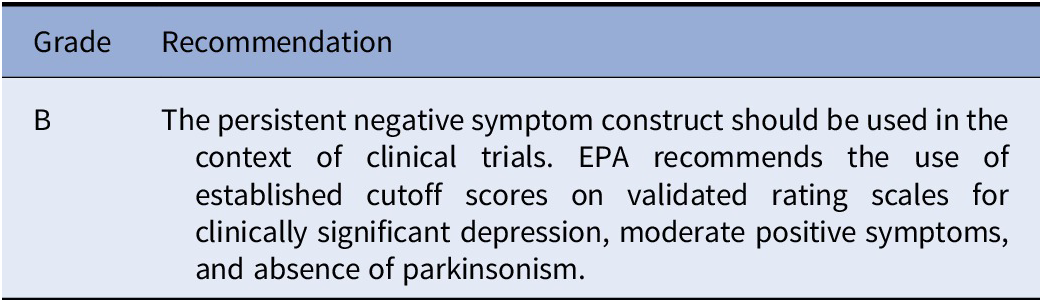

To conclude, available evidence shows that DS and persistent negative symptoms have construct validity and have several advantages over negative symptoms broadly defined for isolating those negative symptoms that still represent an unmet therapeutic need. Compared to the DS, the persistent negative symptom construct has the advantage to be more easily applicable in the context of clinical trials: (a) potential sources of secondary negative symptoms are not excluded as much as in DS, but the persistent negative symptom construct enables the control of the main confounding factors; (b) the construct includes secondary negative symptoms that have not responded to previous treatments; (c) persistent negative symptoms identify a patient population larger than the one with DS; (d) the identification of these symptoms requires less longitudinal observation than the DS categorization, is feasible in early intervention studies, and can be achieved by using assessment instruments such as the PANSS, SANS, BNSS, or CAINS, which are largely available and do not require an ad hoc training, as the SDS does. Therefore, the persistent negative symptom construct, compared to the DS one, represents a clear improvement in the definition of the target population for clinical trials focusing on negative symptoms. However, efforts are needed to make the definition of persistent negative symptoms consistent across studies. In particular, the definition seems to lack the standardization of thresholds of possible confounding factors (i.e., positive symptoms, depression, and extrapyramidal symptoms). Furthermore, the persistence may vary and is sometimes assessed prospectively, some others retrospectively. According to expert recommendation, clinical trials for negative symptoms should include clinically stable patients in the residual phase of their illness, with negative symptoms that persist despite an adequate antipsychotic treatment for a period of 4–6 months, as ascertained retrospectively and also confirmed prospectively for at least 4 weeks. The prospective evaluation of clinical stability is strongly recommended for negative symptoms, since they are difficult to assess retrospectively for many patients [Reference Marder, Alphs, Anghelescu, Arango, Barnes and Caers55].

Recommendation 1 (based on studies included in Table e1)

The EPA Guidance Group on Negative Symptoms considers the persistent negative symptom construct suitable for clinical trials based on available evidence. However, the construct has been heterogeneously applied as to the thresholds for depression, positive, and extrapyramidal symptoms. Therefore, the Group suggests the use of thresholds for clinically significant depression (e.g., 6 for Calgary Depression Scale; 17 for Hamilton Depression scale-17 items), for moderate severity of the positive symptoms (e.g., PANSS score ≤ 4) as well as absence of parkinsonism as assessed on validated scales.

Factor structures of negative symptom domains

Factor analytic studies on general psychopathological rating scales, such as the PANSS or SANS and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms or BPRS, identified items clustering in one or more negative symptom factor/s (Table e2). These studies identified items that do not cluster in the negative symptom factor/s, and provided evidence for excluding attentional impairment (SANS global rating of attention), inappropriate affect (SANS item 6), poverty of content of speech (SANS item 10), difficulty in abstract thinking (PANSS item N5), stereotyped thinking (PANSS item N7), mannerism and posturing (PANSS item G5; BPRS item 24), poor attention (PANSS item G11), and conceptual disorganization (PANSS item P2; BPRS item 15) from the negative symptom dimension (Table e2). Loadings of the items motor retardation (PANSS item G7; BPRS item 18), avolition (PANSS item G13), and active social avoidance (PANSS item G16) have been inconsistent (Table e2).

Based on the consensus initiative and on different factor analytic studies (Table e2) showing the inconsistent loadings of the items N5, N7, P2, G5, G7, G11, G13, and G16 (PANSS), items 6, 10, and the global rating of attention from SANS, as well as items 15, 18, and 24 (BPRS), these symptoms should not be included as negative symptoms in any summary score or subscale score of the negative dimension.

Recommendation 2 (based on studies included in Table e2)

Results of studies comparing different negative symptom models (two-factor, three-factor, four-factor, and five-factor models) are described in the NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement [Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23], in four reviews [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Blanchard and Cohen22, Reference Strauss, Ahmed, Young and Kirkpatrick37], in a commentary [Reference Kirkpatrick and Fischer24], and in an expert opinion [Reference Marder and Galderisi5] (Table e3). The two-factor model, including the Experiential factor (avolition, asociality, and anhedonia) and the Expressive factor (blunted affect and alogia), has gained large consensus over the past decade [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Marder and Galderisi5,Reference Bucci and Galderisi14,Reference Blanchard and Cohen22–Reference Kirkpatrick and Fischer24]. Following the consensus statement on negative symptoms [Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23], the two-factor model was replicated by two studies using the SANS (excluding the Attention subscale) [Reference Strauss, Horan, Kirkpatrick, Fischer, Keller and Miski56,Reference Ergul and Ucok57] and by three studies using the PANSS [Reference Liemburg, Castelein, Stewart, van der Gaag, Aleman and Knegtering58–Reference Jang, Choi, Park, Jaekal, Lee and Cho60]. However, SANS [Reference Strauss, Horan, Kirkpatrick, Fischer, Keller and Miski56,Reference Ergul and Ucok57] and PANSS [58–60] only consider behavior even for the assessment of the experiential deficits (i.e., anhedonia). In addition, studies using the SANS included items that are not considered negative symptoms, such as inappropriate affect and poverty of content of speech [Reference Strauss, Horan, Kirkpatrick, Fischer, Keller and Miski56,Reference Ergul and Ucok57]. Likewise, studies using the PANSS [Reference Liemburg, Castelein, Stewart, van der Gaag, Aleman and Knegtering58–Reference Jang, Choi, Park, Jaekal, Lee and Cho60] included motor retardation, active social avoidance [Reference Liemburg, Castelein, Stewart, van der Gaag, Aleman and Knegtering58–Reference Jang, Choi, Park, Jaekal, Lee and Cho60], avolition, and mannerism and posturing [Reference Liemburg, Castelein, Stewart, van der Gaag, Aleman and Knegtering58,Reference Stiekema, Liemburg, van der Meer, Castelein, Stewart and van Weeghel59], which are not regarded as negative symptoms. Results of studies employing rating scales that assess negative symptoms in line with the consensus statement (SDS, CAINS, and BNSS) supported the two-factor model of negative symptoms [Reference Strauss, Horan, Kirkpatrick, Fischer, Keller and Miski56,Reference Kimhy, Yale, Goetz, McFarr and Malaspina61–Reference Peralta, Moreno-Izco, Sanchez-Torres, Garcia de Jalon, Campos and Cuesta64,Reference Horan, Kring, Gur, Reise and Blanchard29,Reference Kring, Gur, Blanchard, Horan and Reise30,Reference Engel, Fritzsche and Lincoln65,Reference Blanchard, Horan and Collins66,Reference Mucci, Galderisi, Merlotti, Rossi, Rocca and Bucci27,Reference Kirkpatrick, Strauss, Nguyen, Fischer, Daniel and Cienfuegos28,Reference Strauss, Hong, Gold, Buchanan, McMahon and Keller67,Reference de Medeiros, Vasconcelos, Elkis, Martins, de Alexandria Leite and de Albuquerque68]. Thus, the two-factor model seems to be more robust when items unrelated to negative symptoms are excluded. In addition, replications of the two factors were provided independently of treatment and were cross-culturally validated [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4]. The two-factor model has influenced the researchers in studying neurobiological underpinnings that could be targeted by different therapeutic options, with important implications in terms of prognosis and treatment [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4]. Although the two-factor model has been widely validated and is more robust when negative symptoms are assessed using second-generation rating scales, such as the BNSS and the CAINS, a three-factor model using the BNSS [Reference Garcia-Portilla, Garcia-Alvarez, Mane, Garcia-Rizo, Sugranyes and Berge69] and a four-factor model using the CAINS [Reference Rekhi, Ang, Yuen, Ng and Lee70] were also reported (Table e3).

Recently, a review by Strauss and colleagues (2019) [Reference Strauss, Ahmed, Young and Kirkpatrick37], which includes three more recent studies conducted by the same research group, has questioned the validity of the two-factor model [Reference Ahmed, Kirkpatrick, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bertolino71–Reference Strauss, Esfahlani, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bucci73]. The strengths of these studies are the followings: (a) they are multicenter studies with large sample size; (b) two studies [Reference Ahmed, Kirkpatrick, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bertolino71,Reference Strauss, Nunez, Ahmed, Barchard, Granholm and Kirkpatrick72] used the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA); (c) one study [Reference Strauss, Esfahlani, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bucci73] performed the network analysis to overcome the CFA limitations, in particular, the underestimation of the number of factors in the presence of high correlations between factors and small sample size; (d) these studies for the first time used CFA or network analyses of negative symptoms assessed with new-generation rating scales such as the BNSS and the CAINS [Reference Strauss, Ahmed, Young and Kirkpatrick37]. On the whole, the results of these studies showed that a five-factor model, with five factors reflecting the five domains identified by the NIMH-MATRICS Consensus statement, provided the best fit independently of cultures and languages, while a hierarchical model (five negative symptom domains as first-order factors, and the two factors, Experiential and Expressive factors, as second-order factors) showed a slightly worse fit. The results of these studies [Reference Ahmed, Kirkpatrick, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bertolino71,Reference Strauss, Nunez, Ahmed, Barchard, Granholm and Kirkpatrick72] were also replicated by an independent multicenter study [Reference Mucci, Vignapiano, Bitter, Austin, Delouche and Dollfus74]. The two studies [Reference Ahmed, Kirkpatrick, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bertolino71,Reference Strauss, Esfahlani, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bucci73] identified a potential sixth factor, “lack of normal distress” of the BNSS (a reduction in the intensity or frequency of negative emotional experience), that corresponds to the “diminished emotional range” item of the SDS, which also assesses the consummatory anhedonia. However, the results of previous factor analytic studies are controversial. Five SDS studies reported that the item “diminished emotional range” loaded on the Expressive factor [Reference Strauss, Horan, Kirkpatrick, Fischer, Keller and Miski56,Reference Kimhy, Yale, Goetz, McFarr and Malaspina61–Reference Peralta, Moreno-Izco, Sanchez-Torres, Garcia de Jalon, Campos and Cuesta64]. The BNSS studies found that the item “lack of normal distress” loaded on the Expressive factor, with a low saturation [Reference Strauss, Hong, Gold, Buchanan, McMahon and Keller67] and presented low communalities [Reference Mucci, Galderisi, Merlotti, Rossi, Rocca and Bucci27]. Further studies are needed to clarify whether the lack of normal distress belongs to the current negative symptom construct or whether it is part of other psychopathological constructs.

Actually, the above-mentioned studies were conducted by the same investigators [Reference Strauss, Ahmed, Young and Kirkpatrick37,Reference Ahmed, Kirkpatrick, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bertolino71–Reference Strauss, Esfahlani, Galderisi, Mucci, Rossi and Bucci73], thus requiring independent validation; in addition, the psychometric properties of the rating scales considered in these studies (BNSS and CAINS) do not allow an adequate testing of the model, since a factor with less than three items (avolition and asociality include only two items) is generally considered weak and unstable [Reference Brown75]. Notwithstanding the importance of findings provided by CFA and network analyses for future investigations on negative symptom structure and pathophysiological underpinnings, as well as for treatment trials, so far, the available evidence is not strong enough for recommending the use of the five-factor model in clinical trials.

No recommendation is deemed appropriate by the EPA Guidance Group on Negative Symptoms on the factor model to be used in clinical trials. However, as most CFA equally supported the five-factor and hierarchical models of negative symptoms, in which second-order factors were the Experiential and Expressive ones, EPA considers potentially useful to report treatment effects separately for these two factors, which include more than three items and are psychometrically stronger than the five individual domains for all second-generation rating scales as well as SANS, but not PANSS-Negative, BPRS, and the Negative Symptom Assessment (NSA) Scale.

The burden of negative symptoms in schizophrenia

Negative symptoms pose a substantial burden on patients with schizophrenia, their families, and society. In fact, negative symptoms are related to poor functional outcome, increased unemployment, greater severity of the illness, and usually higher antipsychotic dosages [Reference Bobes, Arango, Garcia-Garcia and Rejas7,Reference Harvey and Strassnig76–Reference Galderisi, Rossi, Rocca, Bertolino, Mucci and Bucci78]. A substantial literature, nicely summarized in Awad and Voruganti, highlighted the burden of care [Reference Awad and Voruganti79]. The burden of care is a complex construct encompassing the impact and consequences of the illness on caregivers. Usually, it is subdivided into a so-called “objective burden of care”, which indicates the effect of the disease on taking care of daily tasks (e.g., the household tasks), whereas the so-called “subjective burden of care” indicates the extent to which the caregivers perceive the burden of care [Reference Awad and Voruganti79]. If symptoms persist over a longer period, as could be shown in 25–30% of the patients [Reference Nordstroem, Talbot, Bernasconi, Berardo and Lalonde80], this patient group will show impaired personal and social functioning, unsuitability for work, and reduced quality of life, which include problems with mobility, washing, and dressing. In parallel, this study looked at the carer burden and found that carers of this specific group of patients do devote an average of 20.5 h per week with a notable negative impact on the quality of life measures to support ill relatives [Reference Nordstroem, Talbot, Bernasconi, Berardo and Lalonde80].

In general, increased symptomatology is connected to an increased family burden [Reference Lasebikan and Ayinde81]. Looking at the objective caregiver burden more specifically, the perceived severity of negative symptoms seems to have a direct impact, which is not true for positive symptoms [Reference Provencher and Mueser82]. In families of subjects with schizophrenia the “objective burden” was related to the severity of psychopathology and cognitive deficits, with negative symptoms accounting for the largest percentage of explained variance, while the “subjective burden” was related to psychotic symptoms and age of disease onset, with the latter variable explaining most of the variance [Reference Mantovani, Ferretjans, Marcal, Oliveira, Guimaraes and Salgado83].

A large-scale study found that the severity of psychopathology in patients, the ability of relatives to cope, and the extent of contacts between patients and relatives were predictive of family burden [Reference Roick, Heider, Toumi and Angermeyer84]. Family burden was closely related to patient’s needs and particularly to negative symptoms causing greater disability. A regression model indicated that needs around daytime activities, alcohol and drug consumption, severity of psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms, and degree of disability are all related to higher levels of family burden [Reference Ochoa, Vilaplana, Haro, Villalta-Gil, Martinez and Negredo85].

While these results indicated a central role of negative symptoms in determining caregiver burden, the majority of studies investigating family burden in schizophrenia did not evaluate them or used only a limited assessment of these symptoms. Thus, further studies are needed to draw conclusions.

Assessment of Negative Symptoms

Assessment instruments

Standardized assessments for negative symptoms are necessary in both clinical practice and research. In clinical practice, they allow us to quantify the intensity of the symptoms but especially to appreciate their evolution with a more objective approach. In research, they are essential in therapeutic trials because they provide a standard framework for the definition and quantification of symptoms and allow different clinicians from different cultures to evaluate symptoms of interest in a similar way.

There are two types of scales, on one hand those that have been developed in order to assess symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and on the other hand, those developed for the assessment in other disorders and focused on one domain of the negative symptoms such as apathy/avolition or anhedonia. We can also distinguish scales in which the assessment is carried out by professionals via an interview (hetero-evaluations) and those based on self-evaluations by the patients themselves.

Scales developed for assessing symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia

The NIMH-Negative Symptom Consensus Development Conference [Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder23] has been a milestone for the development of second-generation scales covering five negative symptom dimensions (alogia, social withdrawal, anhedonia, blunted affect, and avolition). Consequently, this paper will present the scales developed before (first generation) and after (second generation) this conference.

Seventeen instruments have been identified (Table e4) but only the second-generation scales are detailed in Table e5. Most of these scales are based on observer ratings and aim to quantify the severity of negative symptoms. Recently, self-report scales have been developed, allowing patient self-assessment of their feelings and experience related to negative symptoms.

First-generation scales

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

Even if BPRS and PANSS are scales covering all the symptoms of schizophrenia, they deserve to be reported for their widespread use in past and present trials. The BPRS is a general psychopathology scale, which originally included 16 items and was later extended to include 18 or 24 items, with ratings ranging from 0 to 6 (or from 1 to 7 depending on the version). Four BPRS negative symptom subscales have been proposed [Reference Nicholson, Chapman and Neufeld86], based on factor analyses, but the most widely used is the “anergy” factor including three items, emotional withdrawal, motor slowing, and emotional blunting [Reference Overall, Hollister and Pichot87,Reference Shafer88]. The sensitivity of this factor to change is lesser than the SANS [Reference Eckert, Diamond, Miller, Velligan, Funderburg and True89]. Moreover, the negative subscale compared to other subscales presents the lowest inter-rater agreement [Reference Andersen, Korner, Larsen, Schultz, Nielsen and Behnke90] and insufficient internal consistency [Reference Dingemans91]. Widely used in therapeutic trials, BPRS as a whole has been supplanted by PANSS since the 1990s.

The PANSS [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler26] includes 30 items rated from 1 (no symptom) to 7 (severe symptom) with three subscales: positive (7 items), negative (7 items), and general psychopathology (16 items). Each item is scored on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 to 7. The absence of a zero score implies that computations of ratios (e.g., percent changes) are not mathematically appropriate and might result in an underestimation of a response. A suggested correction is to subtract the minimum score (e.g., 30) from the total score [Reference Obermeier, Schennach-Wolff, Meyer, Moller, Riedel and Krause92]. The negative symptoms subscale (PANSS negative) includes N1 blunted affect, N2 emotional withdrawal, N3 poor rapport, N4 passive/apathetic social withdrawal, N5 difficulty in abstract thinking, N6 lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation, and N7 stereotyped thinking [Reference Kay93]. PANSS has good psychometric validity [Reference Kay, Opler and Lindenmayer94–Reference Wu, Lan, Hu, Lee and Liou100] and is still widely used in therapeutic trials, including those that target negative symptomatology (see related paragraph). The existence of a semi-structured interview (Structured Clinical Interview for the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia [SCI-PANSS]) and a precise definition of the items and their quantification allow obtaining a very good inter-rater reliability. Internal consistency and test–retest reliability can be considered moderate for the negative subscale. However, compared to other scales (e.g., SANS), PANSS negative subscale had the greatest internal consistency [Reference Peralta, Cuesta and de Leon101] and the use of the SCI-PANSS increases its inter-rater reliability [Reference Lindstrom, Wieselgren and von Knorring102,Reference Von Knorring and Lindstrom103]. Some limitations must also be underlined. Among the seven negative items, N7 is related to disorganization of thought and N5 to cognitive symptoms. Other limitations of the PANSS are the poor assessment of avolition–apathy, the lack of assessment of anhedonia, and the assessments only based on behavioral observation [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Blanchard, Kring, Horan and Gur104–Reference Kumari, Malik, Florival, Manalai and Sonje107].

A five-factor model of the PANSS has been developed [Reference Marder and Kirkpatrick108] and among these factors, a negative symptom factor score (NSFS) containing five items from the PANSS negative (N1, N2, N3, N4, and N6) and two items from the general subscale (G7 motor retardation and G16 active social avoidance) has been identified [Reference Marder, Davis and Chouinard109]. Evidence for reliability and validity and sensitivity to change of the NSFS in schizophrenia patients with prominent negative symptoms has been demonstrated in one study [Reference Edgar, Blaettler, Bugarski-Kirola, Le Scouiller, Garibaldi and Marder110] in which, however, subjects were included if they had either prominent negative symptoms or thought disorganization. Besides the limitations previously suggested, motor retardation and active social avoidance should not be considered as negative symptoms since they might be more related to extrapyramidal symptoms, depression, suspiciousness, or social anxiety. Finally, no single negative symptom factor from PANSS has achieved broad consensus, neither NSFS, even if it has been widely used in many trials, nor the most replicated negative factor including N2, N3, N4, N6, and G7 [Reference Jiang, Sim and Lee111–Reference Ang, Rekhi and Lee113].

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms

SANS [Reference Andreasen25] is an extension of the emotional blunting scale [Reference Abrams and Taylor114] and includes 25 items grouped into the five dimensions: alogia, emotional blunting, avolition–apathy, anhedonia–asociality, and deficit of attention. Each item is defined in a glossary and is scored from 0 to 5. Each of the five dimensions has a global score and a composite score that is the sum of the dimension item scores. The reliability and validity of SANS have been widely proved [Reference Norman, Malla, Cortese and Diaz98,Reference Peralta, Cuesta and de Leon101,Reference Andreasen and Olsen115–Reference McAdams, Harris, Bailey, Fell and Jeste118]. However, obtaining corroborative history from a family member may substantially improve the validity of the assessment of negative symptoms [Reference Ho, Flaum, Hubbard, Arndt and Andreasen119]. SANS has been translated into several languages. A short SANS version with 11 items and 3 response options has been suggested with similar reliability as the original version [Reference Levine and Leucht120].

Although SANS is probably the reference in the evaluation of negative symptoms, some weakness has been pointed out [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4,Reference Strauss, Nunez, Ahmed, Barchard, Granholm and Kirkpatrick72,Reference Blanchard, Kring, Horan and Gur104–Reference Kumari, Malik, Florival, Manalai and Sonje107,Reference Wallwork, Fortgang, Hashimoto, Weinberger and Dickinson121]. Indeed, several factor analyses have supported that the item “deficit of attention” loads on a cognitive factor and other items (“speech content poverty”, “response latency”, and “inappropriate affect”) load more on a disorganization component than on negative factors [Reference Mueser, Sayers, Schooler, Mance and Haas122,Reference Peralta and Cuesta123]. These results are in accordance with previous data that inappropriate affect, inattention, and blocking should not be considered as negative symptoms [Reference Keefe, Harvey, Lenzenweger, Davidson, Apter and Schmeidler124–Reference Peralta and Cuesta126]. In the same vein, the items “poor eye contact” and “grooming and hygiene” did not load on negative dimensions [Reference Rabany, Weiser, Werbeloff and Levkovitz127]. Moreover, anhedonia and social withdrawal are also criticized for evaluating the observed behavior without taking into account the environment and the desire to establish social relations and the ability to experience pleasure during activities. Furthermore, the fact that both these latter aspects are assessed within the same domain constitutes a further limitation as SANS does not separately assess the five negative domains required by the NIMH-Negative Symptom Consensus Development Conference.

As for the PANSS, the SANS is based on behavior manifested by the patient, leading to substantial overlap with functioning, and poor discrimination of secondary negative symptoms [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Buchanan and Arango4]. Moreover, both scales include items, such as “abstract thinking” for PANSS and “attention” for SANS, which rate cognitive deficits, accounting for the association between negative symptoms and cognition [Reference Farreny, Usall, Cuevas-Esteban, Ochoa and Brebion128].

Recommendation 3 (based on studies included in Tables e2 and e5)

The EPA Guidance Group on Negative Symptoms considers appropriate the use of a second-generation rating scale to assess negative symptoms in clinical practice and trials. However, due to the present regulatory agency requirements and to the need of further evidence concerning the sensitivity to change of second-generation rating scales for negative symptoms, EPA recommends using a second-generation scale to complement the PANSS and SANS for the assessment of negative symptoms in clinical trials.

Schedule for Deficit Syndrome

The SDS [Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, McKenney, Alphs and Carpenter42] is the only scale that categorizes patients into deficit and non-deficit subtypes. Six negative symptoms are assessed from 0 (normal) to 4 (severely impaired) in a semi-structured interview: restricted affect, diminished emotional range, poverty of speech, curbing of interests, diminished sense of purpose, and diminished social drive. Deficit schizophrenia is defined by the presence of two or more negative symptoms with a score ≥2 (moderate) and judged both primary (i.e., not caused by neuroleptic akinesia, depression, anxiety, delirium, disorganization, environmental deprivation, and other factors) and enduring for 12 months, including periods of clinical stability and remission of psychotic symptoms. This scale has strong inter-rater reliability and convergent validity [Reference Citak, Oral, Aker and Senocak129], and has the greatest stability compared to other scales [Reference Fenton and McGlashan130]. However, this scale is difficult to use in clinical practice, and the assessment of persistent negative symptoms is more convenient for clinical trials [Reference Buchanan44].

While the limitations of the SDS are relevant to the use of the scale to assess negative symptom domains, they should not put into question the validity of the scale to diagnose the deficit syndrome, which remains a validated categorical approach to identify subjects with primary enduring negative symptoms [Reference Kirkpatrick, Mucci and Galderisi38].

The Negative Symptom Assessment Scale

The NSA [Reference Axelrod, Goldman and Alphs131], largely used in therapeutic trials, is a 16-item scale with a semi-structured interview filled in 30 min, each item is rated on a six-point scale (1–6; or rated as 9 = not ratable). A total score and a global rating are provided. NSA includes five factors, communication, emotion/affect, social involvement, motivation, and retardation. Negative symptoms assessed with NSA-16 drove the changes in the Social and Occupational Functioning Scale rather than the reverse, suggesting that improving negative symptoms may lead to improvements in functional outcomes [Reference Velligan, Alphs, Lancaster, Morlock and Mintz132]. However, the ratings for some of the items are based on behavior and thus a substantial overlap with functioning cannot be excluded. The agreement among raters after training was good [Reference Axelrod and Alphs133] or among raters coming from different countries was at least as high using the NSA-16 as using the PANSS negative subscale or Marder negative factor [Reference Daniel, Alphs, Cazorla, Bartko and Panagides134]. NSA-16 has good psychometric properties and a cutoff point of 31 provided excellent sensitivity and good specificity for separating patients with and without negative symptoms [Reference Garcia-Alvarez, Garcia-Portilla, Saiz, Fonseca-Pedrero, Bobes-Bascaran and Gomar135].

A short version, which allows rapid evaluation of negative symptoms, exists in the form of a four-item scale (NSA-4; 1. Restricted speech quantity, 2. Emotion: Reduced range, 3. Reduced social drive, and 4. Reduced interests). It was tested by more than 400 medical professionals [Reference Alphs, Morlock, Coon, van Willigenburg and Panagides136] and presented good psychometric properties [Reference Alphs, Morlock, Coon, Cazorla, Szegedi and Panagides137]. However, the validation of the short version scale has been carried out only by the group developing NSA and should be independently replicated.

The originality of NSA-16 is to evaluate on the one hand the emotional feeling and on the other hand the emotional expression by asking the patient to mimic emotions. However, similar limitations as those evoked with SANS and PANSS can be pointed out [Reference Blanchard, Kring, Horan and Gur104–Reference Kumari, Malik, Florival, Manalai and Sonje107]. Anhedonia is not evaluated as a separate domain since the capacity to feel pleasure during activity is included in the item “emotion: reduced range” also encompassing the capacity to feel anxious or depressed. Consequently, NSA-16 does not cover the five negative domains required. Some items as impoverished speech content, inarticulate speech, and slowed movements are not considered as negative symptoms. Several items (poor grooming and hygiene, reduced hobbies and interest, and reduced daily activity) are based on functioning or behaviors and their severity is measured by considering the type and the frequency of behavior. Scores on NSA, SANS, and SDS may be reliably converted between them [Reference Preda, Nguyen, Bustillo, Belger, O’Leary and McEwen138].

Recommendation 4 (based on studies included in Table e5)

The EPA Guidance Group on Negative Symptoms considers appropriate the use of a second-generation scale to assess negative symptoms in clinical practice and trials. As reported for the other first-generation scales, the group recommends using a second-generation scale to complement the NSA-16 for the assessment of negative symptoms in clinical trials.

Second Generation Scales

The Brief Negative Aymptom Scale

The BNSS [Reference Kirkpatrick, Strauss, Nguyen, Fischer, Daniel and Cienfuegos28] includes a semi-structured interview to evaluate 13 items that measure the five negative dimensions and the lack of distress. According to the authors of the scale, the interview requires 10–15 min; however, in practice, it generally takes longer (20–25 min). The scale presents good psychometric properties (Table e5). Several studies reported that negative symptoms measured with the BNSS are not significantly affected by the presence of depressive or positive symptoms in stable schizophrenia patients [Reference Mucci, Galderisi, Merlotti, Rossi, Rocca and Bucci27,Reference Treen, Savulich, Mezquida, Garcia-Portilla, Toll and Garcia-Rizo139,Reference Strauss, Keller, Buchanan, Gold, Fischer and McMahon140].

BNSS originality is to take into account the expression of internal experiences and the observed behavior for the social withdrawal and avolition dimensions. Anhedonia is also evaluated by differentiating the consummatory and anticipatory pleasures. An item evaluates the ability to feel distress, and the lack of “distress” is considered as pathological. This item is the subject of controversy, some authors considering that it is not consistent with the definition of negative symptoms [Reference Blanchard, Shan, Andrea, Savage, Kring, Weittenhiller, Badcock and Paulik105], others supporting that might help to differentiate primary and enduring symptoms from secondary negative symptoms [Reference Strauss, Keller, Buchanan, Gold, Fischer and McMahon140]. BNSS was designed for easy application in the context of clinical trials or clinical routines and has excellent psychometric properties in schizophrenia [Reference Kirkpatrick, Strauss, Nguyen, Fischer, Daniel and Cienfuegos28,Reference Ang, Rekhi and Lee113] and in bipolar disorders (76). It has been translated and validated into 29 languages [Reference Tatsumi, Kirkpatrick, Strauss and Opler141], notably Danish [Reference Gehr, Glenthoj and Odegaard Nielsen142], Polish [Reference Wojciak, Gorna, Domowicz, Jaracz, Golebiewska and Michalak143], German [Reference Bischof, Obermann, Hartmann, Hager, Kirschner and Kluge144], Brazilian [Reference de Medeiros, Vasconcelos, Elkis, Martins, de Alexandria Leite and de Albuquerque68,Reference de Medeiros HL, Silva, Rodig, Souza, Sougey and Vasconcelos145], and Spanish [Reference Mane, Garcia-Rizo, Garcia-Portilla, Berge, Sugranyes and Garcia-Alvarez146]. Nine translations were used in a European validation study [Reference Mucci, Vignapiano, Bitter, Austin, Delouche and Dollfus74]. BNSS has substantial advantages with respect to PANSS for the identification of the experiential domain (including avolition, asociality, and anhedonia) and in subjects with predominant negative symptoms [Reference Mucci, Vignapiano, Bitter, Austin, Delouche and Dollfus74]. Preliminary evidence indicates that BNSS is also sensitive to change [Reference Kirkpatrick, Saoud, Strauss, Ahmed, Tatsumi and Opler147].

The Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms

The CAINS came from the Collaboration to Advance Negative Symptom Assessment in Schizophrenia [Reference Blanchard, Kring, Horan and Gur104]. The development of CAINS was based on data-driven iterative process leading to several successive versions [Reference Horan, Kring, Gur, Reise and Blanchard29,Reference Kring, Gur, Blanchard, Horan and Reise30,Reference Forbes, Blanchard, Bennett, Horan, Kring and Gur148]. In its final version, the scale includes 13 items and is administered in 15–30 min, each item being scored on a five-point Likert scale. As BNSS, CAINS contains a comprehensive manual and workbook that provides a semi-structured interview. CAINS addresses the notions of anticipated and consumed pleasures, motivation through the social, professional, and leisure domains. Goal-oriented behaviors are evaluated through the patient’s effort to engage in an activity. The scale has good psychometric qualities and several factor analyses displayed two factors, MAP and EXP (Table e5). These two subscales have good psychometric properties and have been validated in a large sample from nonacademic clinical settings by raters not affiliated with the scale’s developers [Reference Blanchard, Bradshaw, Garcia, Nasrallah, Harvey and Casey149]. A proxy scores of >25 on the CAINS total or a proxy score of >17 on the MAP has been proposed to identify subjects with persistent negative symptoms [Reference Li, Li, Zou, Yang, Xie and Yang150]. These data need to be replicated by an independent group.

CAINS is available in several languages such as Czech, French, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean, Polish, Greek, Swedish, Lithuanian, and German [Reference Blanchard, Shan, Andrea, Savage, Kring, Weittenhiller, Badcock and Paulik105]. Validation studies of CAINS translated into Chinese [Reference Chan, Shi, Lui, Ho, Hung and Lam151,Reference Xie, Shi, Lui, Shi, Li and Ho152], Korean [Reference Jang, Park, Choi, Yi, Park and Lee153,Reference Jung, Woo, Kim and Kwak154], Spanish [Reference Valiente-Gomez, Mezquida, Romaguera, Vilardebo, Andres and Granados155], and German [Reference Engel, Fritzsche and Lincoln65] have been published.

As BNSS, CAINS is based on observer rating and does not need informant to be completed. Both scales assess behavior for the five negative dimensions and internal experiences for avolition and social withdrawal. However, if BNSS contains distinct items for assessing internal experiences, CAINS combines internal experiences and observed behaviors in the same ratings. As BNSS, CAINS yields scores reflecting MAP and EXP. A direct psychometric comparison of BNSS and CAINS showed high correspondence for blunted affect and alogia items but moderate convergence for avolition and asociality items, and low convergence among anhedonia items [Reference Strauss and Gold156]. This finding on anhedonia may be related with the different definitions of items and how these items on anhedonia are assessed. Indeed, CAINS examines the frequency of pleasure and has distinct items assessing social, work, and recreational pleasures while BNSS assesses frequency and intensity of pleasure and has one item assessing social, work, and recreational pleasures, and physical pleasure.

Recommendation 5 (based on studies included in Tables e3 and e5)

EPA considers the use of the BNSS or CAINS appropriate to assess negative symptoms in clinical practice and trials as these scales provide an adequate assessment of all negative symptoms domains (Evidence level I–II). As the evidence concerning their sensitivity to change is limited for BNSS and not present for CAINS, EPA recommends using these scales to complement first-generation scales (such as PANSS, SANS, or NSA-16) in clinical trials.

Scales based on self-assessments

Self-assessments should be considered as complementary measures of scales based on observer-ratings. Compared to these last evaluations, self-evaluation provides clinical information not necessarily detected by caregivers or medical staff in a standard interview and can provide information on the symptoms as recognized by the patients themselves [Reference Engel and Lincoln157].

Two recent scales, the Motivation and Pleasure Scale Self-Report (MAP-SR) [Reference Llerena, Park, McCarthy, Couture, Bennett and Blanchard158] and the Self-evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS) [Reference Dollfus, Mach and Morello159] have been developed specifically for the negative symptoms and supplanted previous tools that do not have good psychometric properties or do not cover the five negative dimensions required [Reference Jaeger, Bitter, Czobor and Volavka160–Reference Iancu, Poreh, Lehman, Shamir and Kotler163].

The Motivation and Pleasure Scale-Self-Report

The MAP-SR [Reference Llerena, Park, McCarthy, Couture, Bennett and Blanchard158] is a self-assessment scale derived from the CAINS motivation/pleasure subscale. The Expression items were removed due to poor reliability and validity, yielding a 18-item version of the MAP-SR [Reference Park, Llerena, McCarthy, Couture, Bennett and Blanchard164]. This point might be considered as a weakness since emotional expression or emotional feeling might allow to differentiate between negative and depressive symptoms [Reference Dollfus, Mach and Morello159,Reference Richter, Holz, Hesse, Wildgruber and Klingberg165]. Although the 18-item version demonstrated adequate internal consistency, three items were excluded due to low item-total correlations yielding a 15-item version. Anhedonia is assessed with six items focusing on experienced and expected pleasure in social, physical, and recreational/vocational domains. Asociality and avolition are evaluated with three and six items, respectively, each item scoring from 0 to 4. This scale presents good psychometric properties [Reference Llerena, Park, McCarthy, Couture, Bennett and Blanchard158] and has been translated and validated into German [Reference Engel and Lincoln166] and Korean [Reference Kim, Jang, Park, Yi, Park and Lee167]. However, it only focuses on the motivation/pleasure dimension and if it is adequate to assess anhedonia it might be less suitable when assessing motivation [Reference Richter, Hesse, Eberle, Eckstein, Zimmermann and Schreiber168]. Moreover, the evaluation contains many questions like “how often” and “how much”, which require that patients remember and quantify what feelings or events happened in the past week, potentially difficult for patients with memory impairment.

The Self-evaluation of Negative Symptoms

The SNS [Reference Dollfus, Mach and Morello159,Reference Wojciak, Gorna, Domowicz, Jaracz, Szpalik and Michalak169] is a concise and easy-to-understand self-assessment scale consisting of 20 items, most of which coming from verbatim reports of patients with schizophrenia. The patient has three choices of answers “completely agree”, “slightly agree”, “strongly disagree” corresponding to 2, 1, and 0, respectively. Thus, a total score (from 0 to 40 for severe negative symptoms) and five sub-scores can be obtained. The advantage of this scale is also to take into account the consummatory and anticipatory pleasure. A pathological threshold at 7 was determined with a very good sensitivity and specificity in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders compared to healthy subjects [Reference Dollfus, Delouche, Hervochon, Mach, Bourgeois and Rotharmel170]. SNS was also used in a general adolescent population demonstrating its possible use for the screening of negative symptoms [Reference Rodriguez-Testal, Perona-Garcelan, Dollfus, Valdes-Diaz, Garcia-Martinez and Ruiz-Veguilla171]. This scale was translated into more than 17 languages [Reference Dollfus, Vandevelde and Bitter172].

Recommendation 6 (based on studies included in Table e5)

Scales focused on one dimension of negative symptoms

Even if negative symptoms are considered as core features in patients with psychotic disorders, they are not specific to schizophrenia and can be found in other mental or neurological disorders such as depression, parkinsonism, dementia, and even in the general population. Consequently, some scales assessing, in particular, anhedonia and avolition/apathy were initially developed in disorders other than schizophrenia. Only scales that were validated in patients with schizophrenia and that presented good psychometric properties are displayed in Table e6.

The scales assessing anhedonia need more validation studies in schizophrenia to be recommended for the assessment of this domain of negative symptoms.

Three kinds of measures have been used in assessing motivation deficit or apathy in schizophrenia, self-reported, clinician-rated, and performance-based measures.

The Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES), commonly used in neurological disorders [Reference Clarke, Van Reekum, Patel, Simard, Gomez and Streiner173], has been also validated in schizophrenia [Reference Clarke, Ko, Kuhl, van Reekum, Salvador and Marin174]. The scale comprises 18 core items that assess and quantify the affective, behavioral, and cognitive domains of apathy but with phrasing varying by rater [self, informant, or clinician] and that rates on a four-point response scale (0 = not at all true/characteristic to 3 = very much true/characteristic). The clinician version of the AES was also validated in first psychotic episode [Reference Faerden, Nesvag, Barrett, Agartz, Finset and Friis175]. The scores of AES, SANS, and Quality of Life Scale (QLS) were highly intercorrelated, supporting that these instruments evaluating motivational deficits are tapping into a similar underlying construct [Reference Fervaha, Foussias, Takeuchi, Agid and Remington176]. A validated shortened Self-reported Apathy Evaluation Scale was also validated in first psychotic episode [Reference Faerden, Lyngstad, Simonsen, Ringen, Papsuev and Dieset177]. It is a 12-item scale, each item scoring on a four-point Likert scale, higher scores indicating severe apathy. The questions focus on the degree of self-experienced motivation and interests during the last 4 weeks and do not include measures of functioning.

Recommendation 7 (based on studies included in Table e6)

Assessment of negative symptoms in first-episode psychosis patients

In first episode psychoses, the assessment of negative symptoms is of interest for several reasons. Meta-analyses on first episode studies find that a higher level of negative symptoms is associated with a lower quality of life [Reference Watson, Zhang, Rizvi, Tamaiev, Birnbaum and Kane178] and is predictive of a poorer functional outcome in terms of functional recovery [Reference Santesteban-Echarri, Paino, Rice, Gonzalez-Blanch, McGorry and Gleeson179]. Likewise, first-episode psychosis patients with a high level of negative symptoms have a lower adherence to treatment [Reference Leclerc, Noto, Bressan and Brietzke180] and an increased risk of deliberated self-harm after treatment [Reference Challis, Nielssen, Harris and Large181].

In the above-mentioned meta-analyses, most of the included trials used the original seven-item sub-score PANSS-Negative to estimate the severity of negative symptoms, while a minority of them measured negative symptoms with the SANS scale. The second-generation scales, that is, BNSS and CAINS, were not used in any of the included trials and there are no published first episode studies using them. Validation studies were mainly carried out in stable and/or chronic patients. Only one study, published after the search end date, included a small sample of unstable, first episode patients [Reference Gehr, Glenthoj and Odegaard Nielsen142] and found a low discriminant validity with respect to positive symptoms and parkinsonism. Although the preliminary nature of these findings does not allow conclusions, they suggest that the challenge of separating primary negative symptoms from those secondary to psychosis and parkinsonism is not yet solved with the use of second-generation scales, such as BNSS, in first episode subjects. Accurate assessment of positive symptoms, depression, and parkinsonism should be carried out in FEP subjects to exclude the secondary nature of negative symptoms.

Although the vast majority of first episode studies have used PANSS or SANS for evaluating negative symptoms, there have been few studies focusing on specific domains, particularly apathy/avolition/amotivation. Only the Apathy Evaluation Scale has been validated in a sample of first episode patients [Reference Faerden, Nesvag, Barrett, Agartz, Finset and Friis175] and was used in two studies [Reference Faerden, Barrett, Nesvag, Friis, Finset and Marder182,Reference Evensen, Rossberg, Barder, Haahr, Hegelstad and Joa183].

As to the factor structure of negative symptoms in first episode samples, the sum score of selected items from PANSS believed to cover the subdomain of amotivation [Reference Fervaha, Foussias, Agid and Remington184] have been used in two studies [Reference Luther, Lysaker, Firmin, Breier and Vohs185,Reference Chang, Kwong, Chan, Jim, Lau and Hui186]. In line with this, few studies have used a suggested factor-structure from the SANS [Reference Foussias and Remington187] to report on the severity of amotivation [Reference Chang, Kwong, Hui, Chan, Lee and Chen188,Reference Chang, Wong, Or, Chu, Hui and Chan189]. Several studies have reported specifically on each of the four SANS-subdomains, that is, Affective flattening, Alogia, Anhedonia/Asociality, and Avolition/Apathy [Reference Ventura, Subotnik, Gretchen-Doorly, Casaus, Boucher and Medalia190–Reference Li, Eack, Montrose, Miewald and Keshavan193]. For both scales, confirmatory factor analyses in first episode samples were published in 2013. The Wallwork/Fortgang five-factor model of PANSS [Reference Wallwork, Fortgang, Hashimoto, Weinberger and Dickinson112] was confirmed to have a reasonable fit in patients with first-episode psychosis [Reference Langeveld, Andreassen, Auestad, Faerden, Hauge and Joa194]. The factor-analyses on SANS detected a three-factor model, consisting of expressivity, experiential, and alogia/inattention, which showed similar model fit as the original SANS five-factor model [Reference Lyne, Renwick, Grant, Kinsella, McCarthy and Malone195]. However, in these factor analyses performed in first episode patients, none of the suggested factor models fully covers the five domains identified by the NIMH-consensus statement. Validation of BNSS and CAINS in first episode samples is therefore crucial for future optimal assessment of negative symptoms in this group of patients.

Because of the convincing prognostic role of negative symptoms in first episode psychosis [Reference Watson, Zhang, Rizvi, Tamaiev, Birnbaum and Kane178–Reference Challis, Nielssen, Harris and Large181], efforts have been made to identify patients with the deficit syndrome or persistent negative symptoms early in the disease. Identifying the deficit syndrome already at the time of admittance to psychiatric services is challenged by the inclusion of a 12-month observation period in the original criteria [Reference Carpenter, Heinrichs and Wagman31] and the need to use the specific scale, SDS [Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, McKenney, Alphs and Carpenter42]. When SDS is combined with a longitudinal observation-period, only 5–10% of a first episode cohort fulfill the criteria for the deficit syndrome [Reference Mayerhoff, Loebel, Alvir, Szymanski, Geisler and Borenstein196], whereas 37% of the patients from another cohort was identified when SDS was applied without a longitudinal observation period [Reference Chen, Jiang, Zhong, Wu, Jiang and Du197]. When using proxy-measures based on BPRS or PANSS [Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan, Breier and Carpenter45] in first episode studies, 26–31% fulfill the criteria of deficit syndrome [Reference Trotman, Kirkpatrick and Compton198,Reference Lopez-Diaz, Galiano-Rus and Herruzo-Rivas199], but again, these high numbers were based on cross-sectional observations only.

In order to evaluate the number of first episode patients with persistent negative symptoms, comparisons of six different definitions were carried out; the proportion of patients with persistent negative symptoms varied between 11 and 26 % [Reference Ucok and Ergul200]. This is in contrast to a large European first episode cohort, where only 6.7% of the sample was identified to fulfill the criteria for persistent negative symptoms when controlling for confounders like depression and parkinsonism [Reference Galderisi, Mucci, Bitter, Libiger, Bucci and Fleischhacker201].