I. Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is one of the most significant geopolitical events in post-Cold War Europe. Beyond its humanitarian impact, it forced the EU to reassess security priorities. Former German Chancellor Olaf Scholz called this moment a “Zeitenwende” (turning point), highlighting Europe’s shifting security landscape.Footnote 1 This transformation has profound implications for EU enlargement, one of the Union’s key external policy instruments.Footnote 2

Throughout its history, EU enlargement has been shaped by a combination of strategic, economic and political considerations. While the EU has consistently emphasised democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, enlargement has also served as a tool to enhance regional stability, strengthen economic ties and contain external threats. The accession of Greece, Spain and Portugal in the 1980s, for instance, was not only a response to democratisation but also a strategic move to secure these countries within the Western bloc.Footnote 3 Similarly, the 2004 and 2007 enlargement rounds, which brought Central and Eastern European states into the Union, were driven by both normative and geopolitical imperatives – extending EU governance structures while stabilising its eastern neighbourhood.Footnote 4

The war in Ukraine has further reinforced the geopolitical dimension of EU enlargement. Since February 2022, the EU has accelerated its engagement with Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia – countries that were previously part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) rather than the enlargement framework. Their rapid transition from peripheral partners to official candidates has led some analysts to compare this shift to the “Thessaloniki moment” of 2003, when the EU committed to the European perspective of the Western Balkans.Footnote 5 The ongoing conflict has intensified the EU’s strategic interest in these countries, raising the question of whether the war could serve as a catalyst for a broader and more geopolitically driven enlargement policy.Footnote 6

This article contributes to the ongoing debate on the evolving nature of EU enlargement, as discussed in this Special Issue, by examining how the EU balances its long-standing commitment to democratic governance with the growing need for security and stability in its neighbourhood. It seeks to address the central question of whether Russia’s war against Ukraine constitutes a geopolitical turning point for the EU’s enlargement policy. Grounded in the theoretical frameworks of historical institutionalism and the concept of turning points, the analysis begins with a review of the literature on EU enlargement, tracing the evolution of enlargement strategy from a multifaceted process to one increasingly shaped by geopolitical imperatives. This is followed by a discussion of the methodological approach, which includes a bibliometric analysis of academic literature to operationalise the concept of a Geopolitical Union (GPU), as well as a quantitative analysis of EU progress reports and enlargement strategies from 2006 to 2023.

The findings suggest that while the EU’s enlargement policy has undergone significant changes in response to the war in Ukraine, these changes do not yet constitute a definitive turning point. The analysis reveals a complex interplay between normative and geopolitical factors, with the EU increasingly integrating geopolitical considerations into its enlargement strategy. However, this shift towards a more strategic approach has not fully replaced the EU’s traditional emphasis on democracy and the rule of law. Instead, it reflects an adaptation to new geopolitical realities while maintaining core EU values. By examining the intersection of normative and geopolitical factors, this article provides insights into the challenges and opportunities the EU faces as it navigates an evolving geopolitical landscape.

II. Theoretical framework

1. Historical institutionalism and the concept of turning points

Historical institutionalism provides a valuable framework for analysing institutional change over time. A key assumption of this approach is path dependency, which suggests that once institutions or policies follow a certain trajectory, they become increasingly resistant to change.Footnote 7 Major transformations are rare and typically occur through critical moments that disrupt entrenched patterns and lead to new policy directions. To differentiate between different degrees of change, Janusch et al. identify four types of pivotal moments: turning points, tipping points, critical junctures, and breaking points.Footnote 8 These concepts help explain whether a given shift represents a fundamental transformation or merely an adjustment within an existing trajectory. A turning point represents a lasting departure from an established path. It occurs when a system irreversibly shifts to a new trajectory. The collapse of the Soviet Union was a turning point that triggered fundamental geopolitical realignments, including EU enlargement.

A tipping point, by contrast, refers to a moment when the forces acting upon an existing path shift, but the direction of the path itself remains unchanged. According to Gladwell, tipping points occur when gradual changes reach a threshold that accelerates further developments.Footnote 9 In the context of EU enlargement, the 2014 Ukraine crisis might be seen as a tipping point: it intensified EU engagement with Eastern Partnership countries but did not immediately alter the EU’s enlargement paradigm.

A critical juncture is a temporary period of loosened structural constraints, allowing actors to make choices that can lead to long-term institutional change.Footnote 10 Unlike turning points, which imply a definitive shift, critical junctures provide opportunities for change but do not necessarily result in a new trajectory.Footnote 11 The post-Cold War opening of EU enlargement to Central and Eastern Europe represents such a moment: While the EU had multiple strategic options at the time, it ultimately committed to integrating these countries through accession.

A breaking point differs from the previous concepts as it signifies a sudden and uncontrollable rupture, where existing structures lose their ability to regulate the system. In political terms, breaking points occur in moments of acute crisis, such as state collapse, revolutions, or severe conflicts.Footnote 12 In the context of EU enlargement, a hypothetical disintegration of the Western Balkans accession process due to internal instability could be considered a breaking point.

In assessing whether Russia’s war against Ukraine constitutes a turning point for EU enlargement, it is crucial to determine whether the shift is irreversible or merely represents a temporary window of opportunity for policy adaptation. If the war fundamentally redefines enlargement as a geopolitical necessity rather than a normative process it would indicate a turning point. If, however, the EU continues to balance normative and geopolitical considerations without fundamentally altering its accession criteria, the current situation may be better understood as a critical juncture or tipping point.

2. EU enlargement: balancing the logics of appropriateness and consequences

To better understand how normative and geopolitical logics intersect, it is useful to draw on March and Olsen’s distinction between two fundamental logics of action: the logic of appropriateness and the logic of consequences.Footnote 13 The logic of appropriateness suggests that actors follow norms based on shared identities and institutional rules, while the logic of consequences explains actions as strategic calculations shaped by material interests. These logics often overlap in practice, influencing both the EU’s foreign policy and the responses of third countries.

The Normative Power Europe (NPE) framework, developed by Ian Manners, aligns with the logic of appropriateness.Footnote 14 Manners argues that the EU exerts influence primarily through the diffusion of norms, rather than through coercion or material incentives. According to this perspective, the EU shapes global governance by promoting five core norms.Footnote 15 These core norms – peace, liberty, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law – are deeply embedded in EU treaties and codified through the Copenhagen criteria for enlargement.Footnote 16 Peace has been central to the EU’s integration project since its inception, with enlargement serving as a tool to prevent instability in neighbouring regions. This is particularly evident in the Western Balkans, where the EU has positioned itself as a stabilising force following the wars of the 1990s. Liberty, encompassing civil and political freedoms, is equally emphasised, particularly in the assessment of media pluralism and civic space in candidate countries. Democracy remains a key requirement for accession, with the EU demanding free and fair elections, institutional transparency, and accountable governance. Human rights have gained increasing weight in the EU’s conditionality, particularly regarding minority rights, gender equality and anti-discrimination policies. The EU’s monitoring frameworks now regularly assess judicial independence and civil liberties, reflecting concerns over democratic backsliding. Finally, the rule of law is perhaps the most politically sensitive norm, requiring candidate states to ensure judicial independence, anti-corruption mechanisms, and legal predictability. Weak rule-of-law reforms have repeatedly delayed accession processes, particularly in the Western Balkans. Beyond these five core norms, four additional minor norms complement the EU’s normative framework: social solidarity, anti-discrimination, good governance and sustainable development. While these norms play a less central role in enlargement conditionality, they are nonetheless embedded in EU treaties, policies, and external relations.

The concept of NPE becomes particularly relevant in the context of EU enlargement.Footnote 17 The enlargement process is often portrayed as a key mechanism through which the EU diffuses its norms to candidate countries.Footnote 18 By setting stringent accession criteria, known as the Copenhagen criteria, the EU has been able to promote democracy, human rights and the rule of law in accession states.Footnote 19

According to Frank Schimmelfennig, this approach transformed the EU into a “liberal community,” using the policy of conditionality as its primary mechanism for transformation.Footnote 20 Through what Schimmelfennig terms “rhetorical action,” the EU compelled reluctant member states to align with its normative agenda by appealing to shared values and shaming opposition.Footnote 21 This strategy was particularly effective during the “big bang” enlargement, as Member States departed from self-interested behaviour to accommodate Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, driven by a sense of collective responsibility.Footnote 22 However, the logic of consequences has always played a role in EU enlargement, reflecting geopolitical and strategic interests.Footnote 23 While the EU has positioned itself as a normative power, its enlargement policy has often served broader strategic objectives, including regional stability, economic security, and countering external threats. This dual logic is particularly evident in the Western Balkans, where the EU has balanced democratic conditionality with stability concerns.Footnote 24

Nonetheless, the effectiveness of the EU’s conditionality-based approach has declined in recent years.Footnote 25 Noutcheva argues that candidate countries increasingly perceive EU conditionality as externally imposed and strategically motivated rather than genuinely normative.Footnote 26 This has led to fake or partial compliance, where governments formally adopt EU norms without implementing substantive reforms, particularly in the Western Balkans. While rhetorical action and the community trap mechanism were decisive during the first phase of enlargement, their influence has waned in later phases, especially where geopolitical considerations have begun to outweigh normative goals.Footnote 27

The war in Ukraine has intensified the geopolitical dimension of enlargement, accelerating accession processes for Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia. While the core norms of NPE – peace, liberty, democracy, the rule of law, and human rights – remain central to the enlargement framework, the EU’s increasing focus on geopolitical considerations suggests a shift towards a more strategic and interest-driven enlargement approach. The question remains whether this shift represents a full departure from NPE or an adaptation of existing enlargement strategies to new geopolitical realities.

3. From normative power to geopolitical union?

While NPE has long served as a conceptual framework for understanding the EU as a promoter of democratic values and norms, the idea of a Geopolitical Union (GPU) reflects a more pragmatic and strategic orientation, aimed at securing the EU’s interests in an increasingly fragmented, power-driven global order.

The concept of a GPU was explicitly articulated by Ursula von der Leyen in her 2019 inauguration speech, where she emphasised the need for the EU to become more strategic in its external policies.Footnote 28 According to von der Leyen, this would mean not only relying on traditional soft power tools but also adopting a more robust and interest-driven approach to foreign policy, including defence, economic security, and geopolitical stability. This vision reflects the idea that the EU must adapt to an international system increasingly defined by power politics and competition, particularly in response to crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine.Footnote 29 Von der Leyen’s vision of a geopolitical Commission underscores a shift from a primarily normative power – where the EU influences global norms and values – to a more interest-driven geopolitical model.Footnote 30 It is worth recalling Diez’s argument here: Even when the EU invokes security and stability as key enlargement considerations, these interests are framed within a discourse that justifies them in terms of European norms and values. Thus, while the EU’s enlargement policy is becoming more geopolitically strategic, its core narrative remains embedded in a normative framework.Footnote 31

This shift has sparked intense debate among scholars and policymakers.Footnote 32 Beshku highlights the persistent tension between normative objectives and geopolitical concerns, particularly in the Western Balkans, where the EU has had to balance democratic reforms with stability imperatives.Footnote 33 In this context, the GPU perspective suggests that enlargement should no longer be viewed primarily as a tool for spreading European values, but as a mechanism for securing strategic interests, including regional stability and countering foreign influence. However, Bialasiewicz critically examines the notion of a “geopolitical turn,” warning that a shift towards a more interest-driven enlargement policy could risk replicating problematic historical narratives, including neo-imperial tendencies.Footnote 34

Kundnani adds another important layer of critique by noting the “geopolitical confusion” within Europe.Footnote 35 He argues that while the EU aspires to be more geopolitical, there is a lack of clarity and consensus about what this actually means in practice. Different member states interpret the concept in ways that reflect their own national interests, leading to a disjointed and sometimes contradictory approach. This “geopolitical confusion” complicates the EU’s ability to present a united front in global affairs, particularly in relation to enlargement policy and relations with neighbouring countries.

Although the concept of a GPU provides a useful lens for understanding the EU’s evolving role, as Kundnani argues, it remains under-theorised and lacks the analytical clarity required for a comprehensive analysis. This vagueness makes it difficult to apply in its current form, particularly when trying to assess the rethinking of the EU’s enlargement policy in response to external pressures, as it is the aim of this Special Issue. To address this conceptual gap, the following analysis aims to empirically substantiate the concept of GPU through a bibliometric study of the academic literature. This will allow a clearer examination of the question of whether the enlargement of the EU is indeed experiencing a substantial turning point.

III. Methodology

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining bibliometric analysis to conceptualise the GPU and quantitative content analysis of EU progress reports to examine the evolution of normative and geopolitical priorities in enlargement policy. This dual approach allows for both a theoretical and an empirical assessment of whether Russia’s war against Ukraine constitutes a geopolitical turning point for EU enlargement.

1. A bibliometric analysis for operationalising a geopolitical union

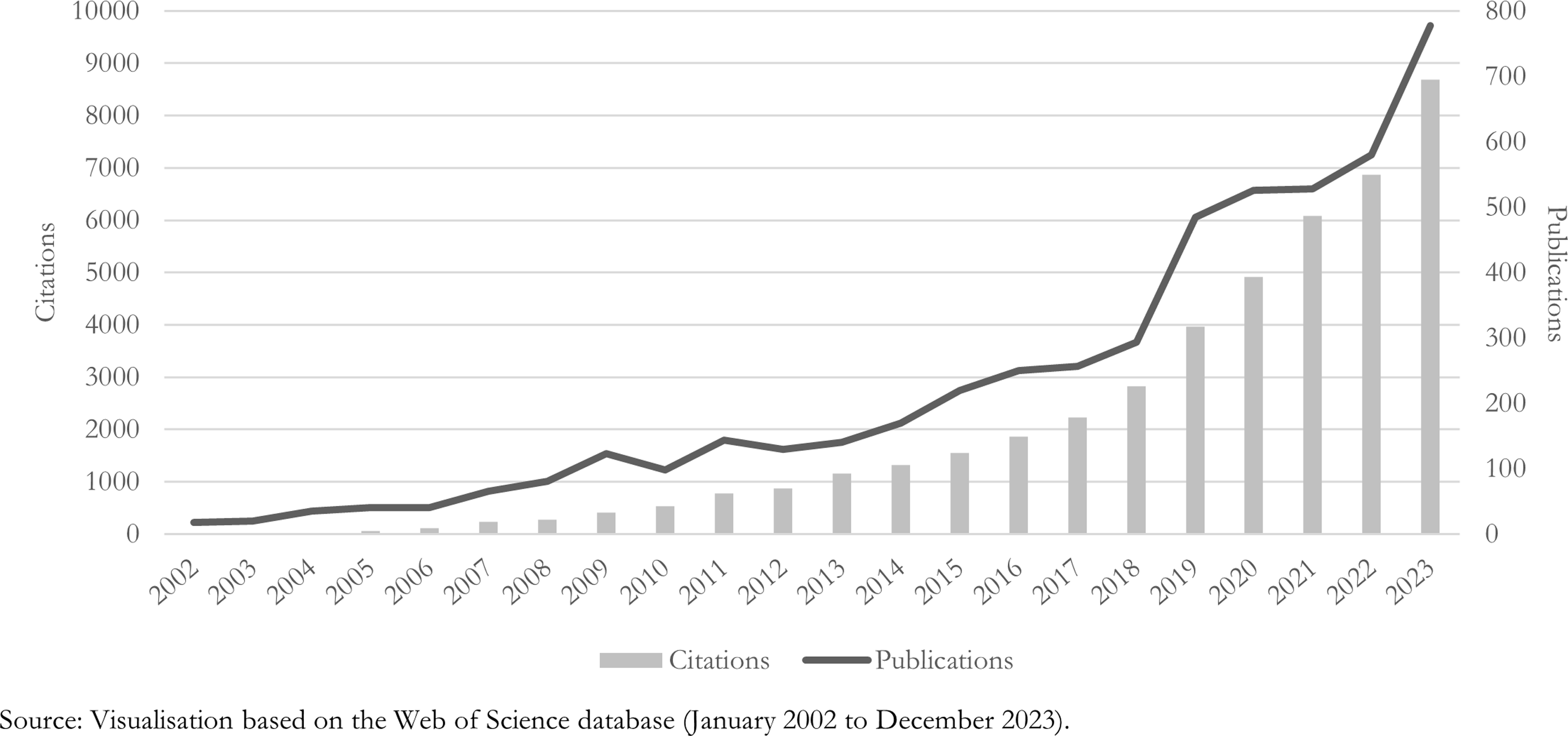

To analyse the academic debate on the concept of GPU, a bibliometric analysis was conducted, identifying key themes and trends in scholarly literature.Footnote 36 The analysis followed a five-step process: The search in the Web of Science Core Collection for the terms “EU,” “Europe” or “European” combined with “geopolitical” or “geopolitics” from 2002 to 2023 yielded 5,018 results in titles, abstracts and keywords. Articles, book chapters, proceedings papers, editorial material, book reviews, review articles, early access works and books were qualified for further analysis. Other publication types were left out. The search results are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Number of publications and citations in the field of GPU.

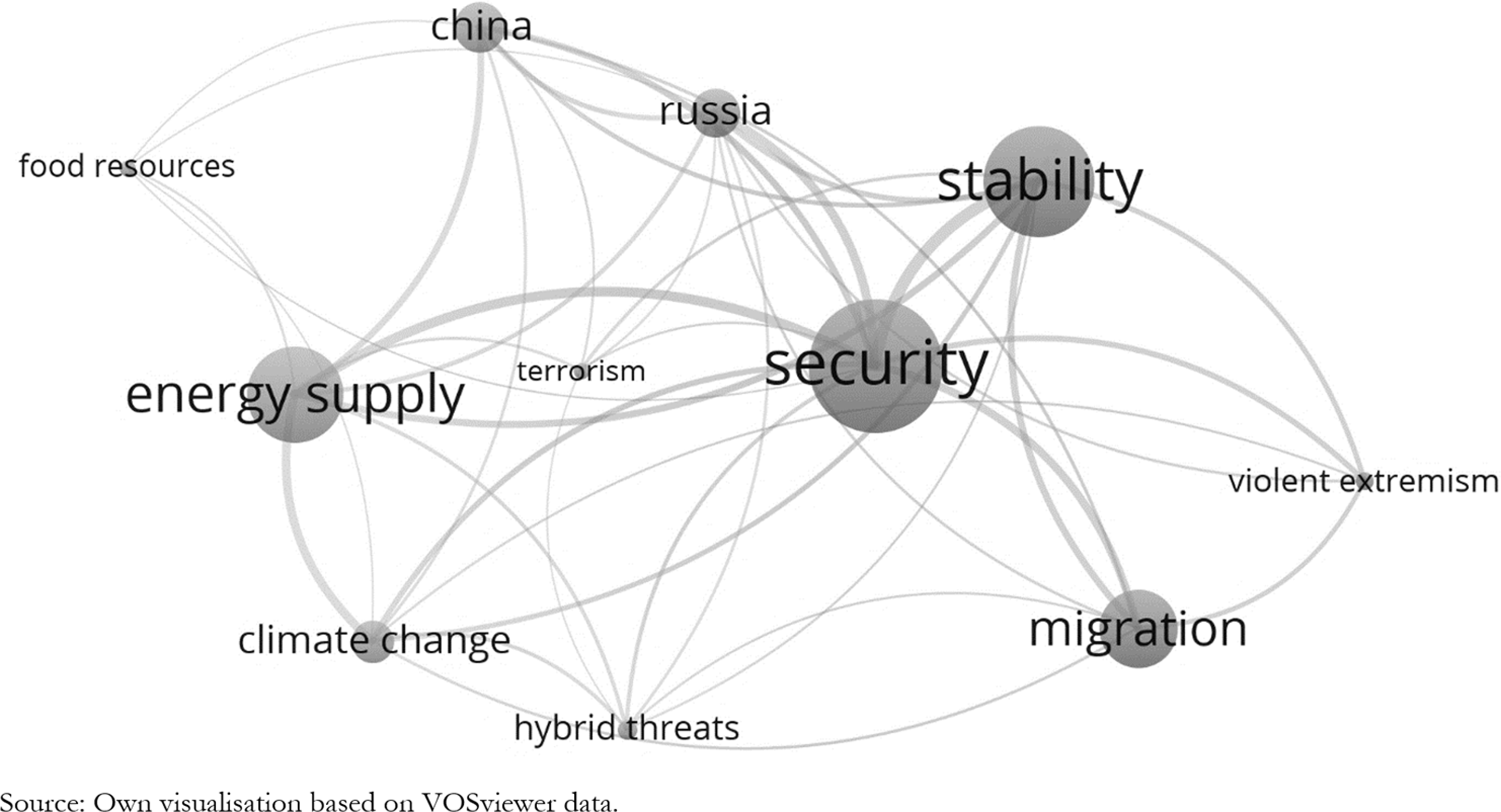

Based on the obtained data, the most frequently occurring keywords were detected. To eliminate different types of terms with the same meaning or irrelevant to the study, a thesaurus file was additionally prepared.Footnote 37 For this file only keywords were used that appeared at least five times. This resulted in a set of 372 specific keywords, covering the field of European geopolitics over the past two decades. Then, based on an in-depth review of these keywords, thematic clusters were identified and a map reflecting the co-occurrence of keywords related to GPU was prepared via VOSviewer.Footnote 38 The resulting final set contained nine thematic clusters. The most frequent terms and the links between these clusters are presented in Fig. 2. To enable a structured comparison, this study defines five core norms and four minor norms for GPU in analogy to the NPE model.

Figure 2. Cluster co-occurrence map on GPU.

Security and stability are the most frequently referenced themes, reflecting the EU’s emphasis on regional stability in response to external threats, particularly in the Western Balkans and Eastern Partnership countries. The war in Ukraine has further reinforced this priority, positioning EU enlargement as a strategic necessity rather than a normative project. Energy supply has also gained prominence, especially since 2014, as the EU has sought to reduce dependency on Russian gas and bolster energy diversification. The importance of energy security is reflected in the increasing references to energy transition, interconnectivity and market integration in enlargement reports, particularly regarding the Western Balkans’ integration into the EU’s energy market. Foreign interferences, particularly from Russia and China, are another growing concern. EU policy documents highlight hybrid threats, disinformation campaigns and economic dependencies as key risks, particularly in Serbia, Montenegro and Ukraine. The EU’s response has included enhanced monitoring mechanisms and diplomatic countermeasures, signalling a more assertive approach. Migration remains a crucial issue, particularly in Greece, Italy and the Western Balkans, where migration pressures have shaped both domestic and EU-level policies. While earlier EU enlargement reports framed migration in terms of labour mobility and rights protection, more recent discourse has increasingly emphasised border security, returns and readmission agreements. Climate change, though not the most dominant theme, is gaining strategic relevance, particularly through the EU Green Deal and decarbonisation policies. Enlargement reports increasingly reference climate adaptation measures, particularly in relation to candidate countries’ obligations to align with EU environmental and energy policies. Beyond these five core norms, additional four minor norms such as food security, hybrid threats, terrorism, and violent extremism appear in the literature, albeit with less frequency. Their relevance fluctuates depending on specific political and security contexts, as seen in references to cybersecurity threats in the Western Balkans or food supply challenges following the war in Ukraine.

After introducing the theoretical model of NPE and operationalising the GPU concept through a bibliometric analysis, the focus now shifts to how these models are applied in practice within the EU enlargement policy.

2. A quantitative analysis of EU progress reports

The European Commission’s progress reports, or “enlargement reports,” are key documents assessing candidate countries’ progress in meeting EU membership criteria. Published annually, they evaluate political and economic reforms.Footnote 39 The first progress reports were published in 1998 in preparation for the Eastern enlargement, when ten countries joined the EU. Since 2005, the Commission has also produced an annual “enlargement strategy” or “communication on EU enlargement policy”. The enlargement strategy is a policy framework outlining the EU’s strategic approach to enlarging its membership through the integration of (potential) candidate countries. Both types of documents provide valuable insights into the evolving normative structure of EU enlargement policy.

To quantitatively map this evolution, a computer-assisted content analysis is used to make reproducible comparisons across norms, time and countries.Footnote 40 For the purposes of this study, all progress reports and enlargement strategies published by the European Commission between 2013 and 2023 were collected. The time period was chosen for various reasons. Firstly, Croatia joined the EU in 2013, so from that year onwards the focus was on the countries of the Western Balkans and Türkiye. In the same year, the Commission also presented its first progress report for Kosovo. It was also important to cover as many different European Commission colleges as possible. The dataset therefore covers the Barroso II Commission (2010–2014), the Juncker Commission (2014–2019) and the von der Leyen I Commission (2019–2024). All documents, which are publicly available on the Commission’s website, were imported into MAXQDA for coding and analysis. The coding was done using the MAXQDA auto code method with dictionary. Generally, auto coding proved to be a powerful tool.Footnote 41 Veen and Meyer-Sahling have already demonstrated this, particularly for the Commission’s progress reports.Footnote 42

Once the coding process was complete, the results of MAXQDA were summarised quantitatively to analyse the frequency and distribution of codes across the documents, as shown in the following section. However, it must be noted that while this quantitative approach provides valuable insights into the shifting prominence of normative and geopolitical considerations in EU enlargement discourse, it does not capture how these concepts are constructed and contested within specific policy contexts.

IV. Findings and analysis

The following analysis presents the quantitative findings of the study, focusing on the relative frequency of references to normative and geopolitical concepts in EU enlargement reports between 2013 and 2023. This quantitative approach allows for a systematic assessment of trends over time, identifying whether geopolitical considerations have gained prominence at the expense of normative commitments.

From a social constructivist perspective or a Foucauldian standpoint, terms such as security, stability, or sovereignty are not static categories but are discursively constructed in different ways depending on the policy context.Footnote 43 The EU’s enlargement discourse has evolved over time, shifting from a predominantly normative agenda towards a more strategic, geopolitical framing. While this quantitative approach provides valuable insights into the shifting prominence of these categories, it must be noted that the meaning attributed to these terms varies across different enlargement reports. To better capture these dynamics, the following analysis presents the quantitative findings and contextualises them by incorporating direct references from the official EU enlargement reports, illustrating how key geopolitical norms have been framed in specific political contexts.

1. Assessing EU enlargement over time

The data show that EU enlargement has consistently operated within two frameworks: NPE and GPU. These models reflect the EU’s ambition to balance normative values and geopolitical interests, as outlined in the 2016 Global Strategy:

“Our interests and values go hand in hand. We have an interest in promoting our values in the world. At the same time, our fundamental values are embedded in our interests. “Peace and security, prosperity, democracy and a rules-based global order are the vital interests underpinning our external action.”Footnote 44

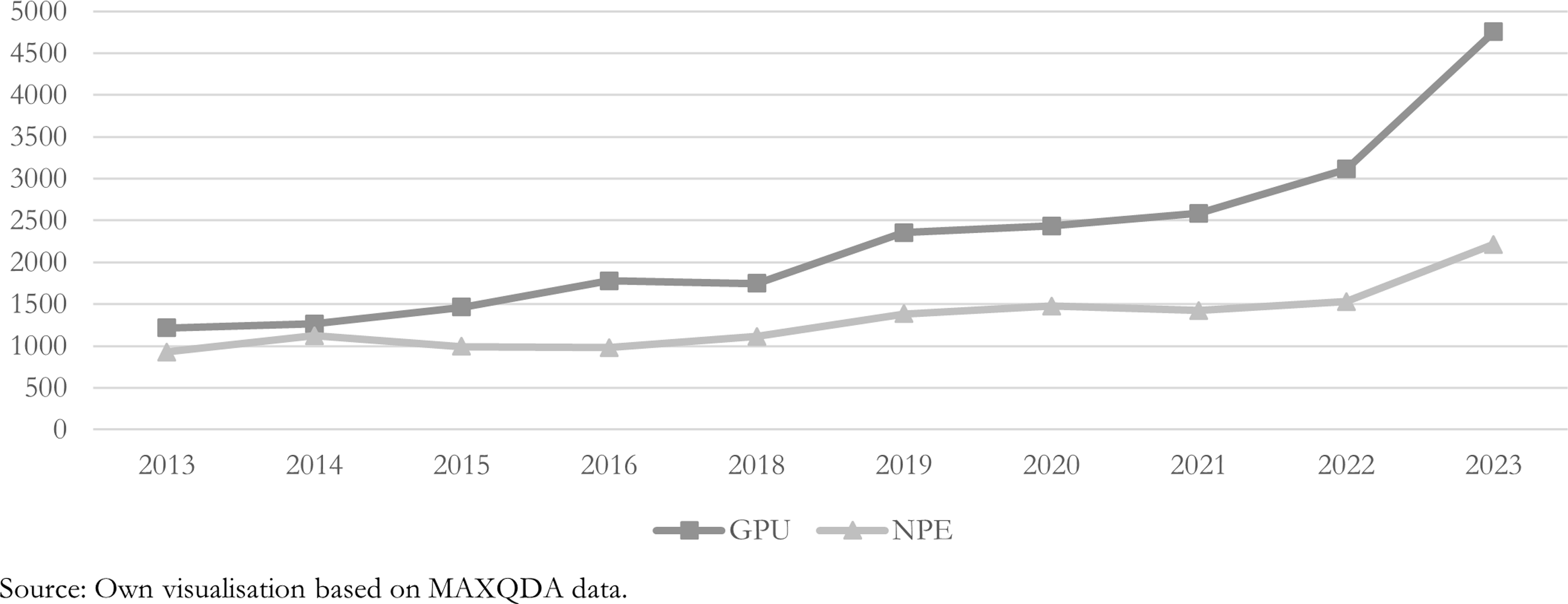

By analysing the trends between 2013 and 2023, distinct developments that align with key events in EU external relations become apparent. As the absolute numbers show, both NPE and GPU have seen a rising trend over the years, with notable peaks in specific periods (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Development of the NPE and GPU model in absolute numbers (2013–2023).

The NPE model, capturing the EU’s normative ambitions, remained consistently important, peaking in 2014 and 2018. These spikes correspond with heightened EU efforts to promote democratic reforms, particularly during the 2014 Ukraine crisis. 2014 was also the year of the launch of the so-called Berlin process, a German initiative to reinvigorate the integration process in the Western Balkans.Footnote 45 This initiative aligned with the 2014 European Commission’s medium-term strategy for EU enlargement, which underscored the broader rationale for enlargement:

The EU’s enlargement policy is an investment in peace, security and stability in Europe. It provides increased economic and trade opportunities to the mutual benefit of the EU and the aspiring Member States. The prospect of EU membership has a powerful transformative effect on the countries concerned, embedding positive democratic, political, economic and societal change.Footnote 46

The 2018 peak aligns with the EU-Western Balkans summit in Sofia, where the EU reaffirmed its commitment to enlargement. The summit emphasised both the EU’s normative commitment to democratic reforms in the region and its strategic interest in countering external pressures, particularly from Russia and China, showing the dual-track approach that combines NPE and GPU.Footnote 47

In contrast, the GPU experienced a significant increase from 2015, with some peaks in 2019 and 2023. The data highlights a significant increase in GPU mentions, suggesting a growing concern with geopolitical stability. This shift coincides with certain security threats, particularly after the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, which underscored the vulnerability of regions like the Western Balkans to external geopolitical influence. The Prespa Agreement of 2018, which resolved the long-standing name dispute between Greece and North Macedonia, was a key moment in this evolution. The agreement not only demonstrated the EU’s leverage in facilitating regional diplomacy but also reinforced the notion that geopolitical stability had become a precondition for accession progress. In its 2019 enlargement communication, the Commission explicitly linked EU enlargement to the containment of external geopolitical influences, warning that:

Failure to reward objective progress by moving to the next stage of the European path would damage the EU’s credibility throughout the region and beyond. A tepid response to historic achievements and substantial reforms would undermine stability, seriously discourage much needed further reforms and affect work on sensitive bilateral issues like the Belgrade–Pristina dialogue. Strategically, it would only help the EU’s geopolitical competitors to root themselves on Europe’s doorstep.Footnote 48

The steady rise of GPU mentions in the years following 2015 reflects this shift in focus, as the EU responded to growing external pressures from actors like Russia and China. The data suggests that by this point, the EU had begun integrating its normative agenda with its geopolitical strategy, using enlargement as a dual tool for promoting stability and countering external threats. Moreover, by 2021, geopolitical arguments dominated the rationale for enlargement:

A credible enlargement policy is a geostrategic investment in peace, stability, security and economic growth in the whole of Europe.Footnote 49

A certain trend change can therefore already be seen under the aegis of Jean-Claude Juncker and thus long before Ursula von der Leyen took office. However, the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022 has had a particular impact on the EU’s enlargement policy. In its 2022 communication, the Commission now explicitly framed enlargement as a defensive geopolitical tool to counter external aggression:

The Russian aggression has demonstrated more clearly than ever that the perspective of membership of the European Union is a strong anchor not only for prosperity, but also for peace and security.Footnote 50

By 2023, the EU’s rhetoric had shifted further, explicitly linking enlargement to the war in Ukraine:

Responding to the call of history, we must now work on accelerating EU enlargement and completing the Union.Footnote 51

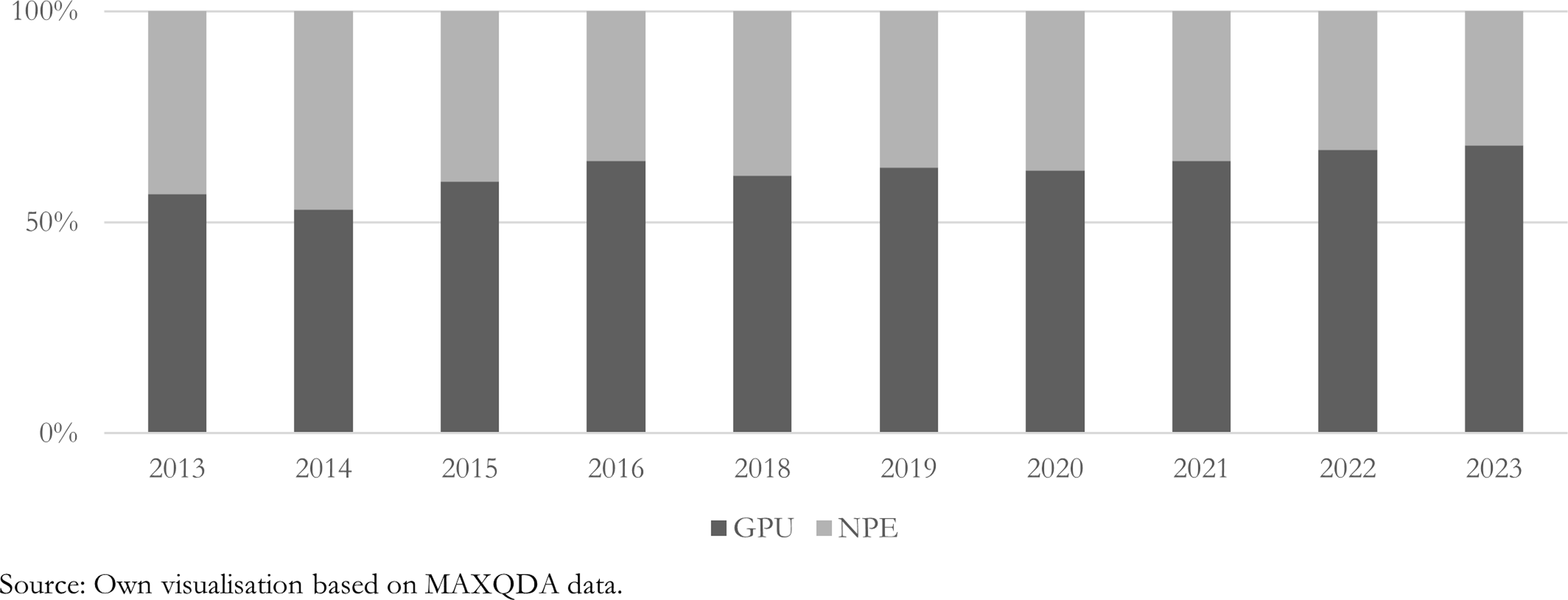

The relative increase in the GPU model can be seen very clearly when both models are related to each other, with the fluctuations mentioned above occurring over the years (Fig. 4). Effectively, the data reveals a moderate positive correlation of 0.63 between NPE and GPU, underscoring that these two frameworks are intertwined in the EU’s enlargement strategy to a certain degree. Accordingly, the EU’s emphasis on normative reforms often goes hand-in-hand with its geopolitical strategy. Enlargement is not only seen as a way to promote European norms and values but also as a strategic geopolitical tool in neighbouring third countries. The simultaneous rise of NPE and GPU in key years, such as 2014 and 2018, suggests that the EU has increasingly recognised the importance of integrating its normative and geopolitical objectives. This dual approach allows the EU to promote democracy and rule of law in candidate countries while also ensuring that these regions remain secure and stabile, especially in the face of influence from other external powers like China and Russia.

Figure 4. Relative percentage ratio of the NPE and GPU model (2013–2023).

2. Balancing normative values and geopolitical interests

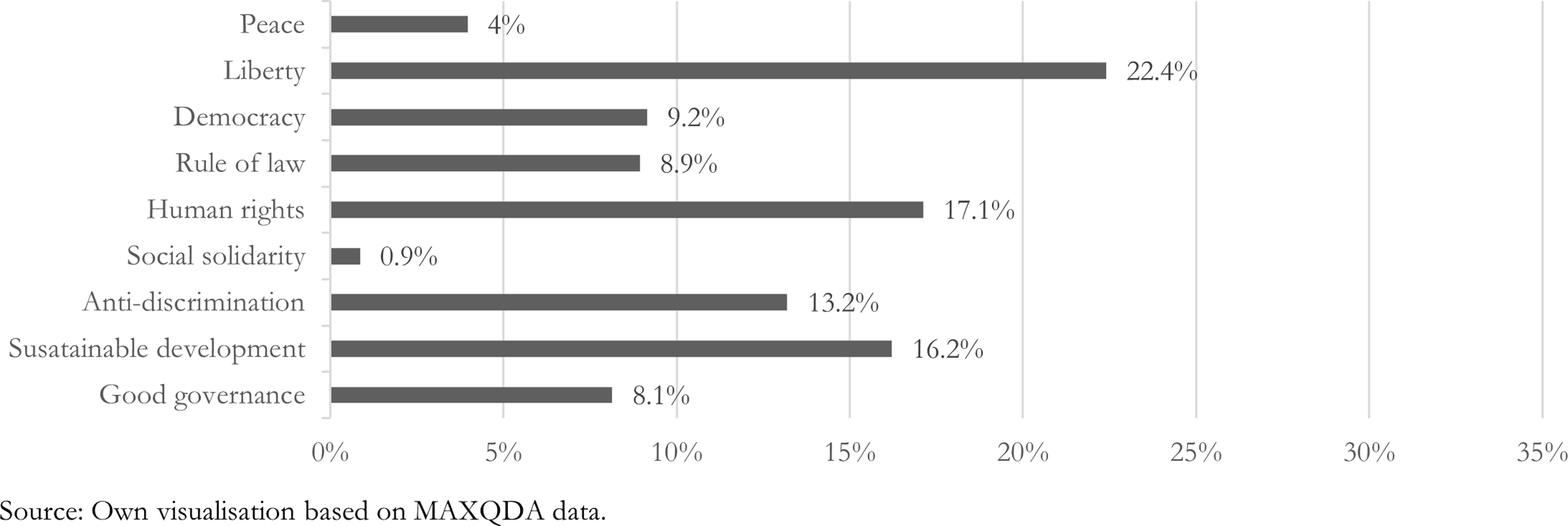

A look at the distribution of norms according to both models over the entire period provides a differentiated picture. In the NPE model, liberty and sustainable development standing out as the most dominant norms (Fig. 5). Liberty constitutes 22.4 per cent of the total mentions, making it the most frequently cited norm, with 2,952 occurrences. This reflects the strong focus on personal freedoms and democratic principles across the analysed countries, aligning with the NPE model, which prioritises the promotion of liberal democratic values. Following closely, sustainable development makes up 16.2 per cent of the total mentions, with 2,137 occurrences. This highlights the growing importance of environmental and economic sustainability, particularly within the context of EU integration processes and global environmental challenges. The increasing prominence of sustainability indicates a shift in regional priorities toward long-term ecological and economic considerations.

Figure 5. Core and minor norms of the NPE model.

Human rights are another key norm, representing 17.1 per cent of the mentions. Its strong presence underscores the EU’s commitment to promoting human dignity and rights in the region, further reinforcing the normative goals of the NPE model. Additionally, anti-discrimination plays a significant role, accounting for 13.2 per cent of the total mentions. This norm indicates ongoing concerns in the region regarding equality and social justice, particularly as these countries navigate the complexities of post-conflict recovery and democratisation. Other norms, such as democracy and rule of law, while less frequently mentioned, still hold considerable importance, making up 9.2 per cent and 8.9 per cent of the total mentions, respectively. These values are essential to the EU’s broader normative framework and are integral to the criteria for potential EU membership. Together, these trends illustrate a consistent focus on core democratic principles such as liberty and human rights, while also highlighting the growing emphasis on sustainability and anti-discrimination policies, which reflect both normative aspirations and pragmatic concerns in EU foreign policy during the analysed period.

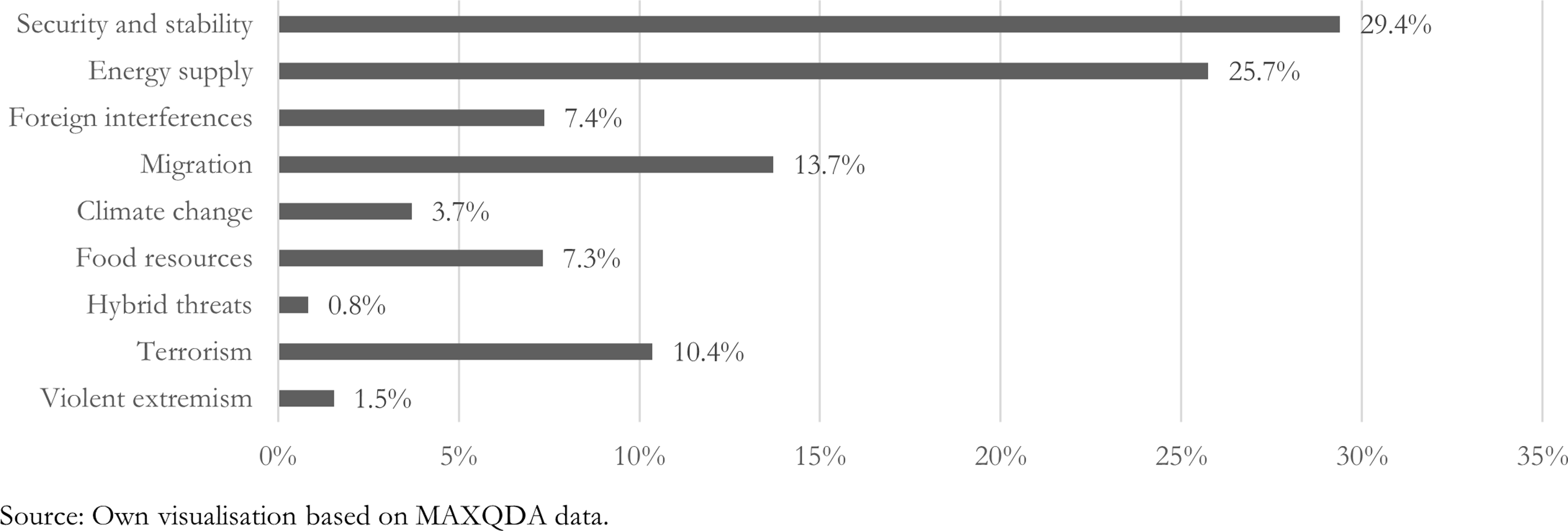

In the GPU model, security and stability emerges as the most dominant norm, making up 29.4 per cent of the total mentions with 6,682 occurrences (Fig. 6). This high percentage reflects the growing importance of maintaining stability in the region, particularly in the face of ongoing geopolitical tensions. The second most significant concern is energy supply, which accounts for 25.7 per cent of the total mentions. The prominence of this norm highlights the region’s dependency on external energy sources and the strategic importance of securing reliable energy supplies, especially in light of regional vulnerabilities. Foreign interferences, with 7.4 per cent of the mentions, signals a persistent concern regarding the influence of external actors in the domestic affairs of these countries. This aligns with broader geopolitical challenges, particularly regarding Russia’s role in Eastern Europe. Similarly, migration, which constitutes 13.7 per cent of the total, is another key issue, reflecting the challenges posed by both internal displacement and migration into and out of the region, especially in the context of economic instability and political unrest. Other norms, such as climate change and food resources, are less prominent but still significant, representing 3.7 per cent and 7.3 per cent of the total, respectively. These figures suggest that while environmental issues are not the primary focus, they are still relevant concerns in the broader geopolitical landscape. Terrorism also holds a notable place, comprising 10.4 per cent of the mentions, pointing to ongoing security challenges related to both domestic and international terrorism.

Figure 6. Core and minor norms of the GPU model.

The evolution of norms from 2013 to 2023 demonstrates a considerable dynamic across countries and years. For example, rule of law and human rights gains early emphasis in Kosovo, with a strong focus on governance reforms, while liberty sees greater prominence in Serbia, which reflects its unique political trajectory compared to neighbouring countries like Bosnia and Herzegovina. Energy supply emerges as a critical issue, particularly for Kosovo, where concerns about energy security were already high by 2013, foreshadowing the growing regional dependency on external resources. Security and stability remain consistently important, with Serbia recording high mentions in this area, reflecting the broader geopolitical instability in the Western Balkans. Additionally, migration becomes increasingly prominent in countries like Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia, highlighting the region’s shifting priorities in response to both domestic and international pressures. These trends illustrate how norms evolve dynamically, influenced by both national circumstances and broader geopolitical changes. In order to provide an even clearer picture of the distribution of certain norms in the candidate countries, the year 2023 is therefore focussed on in the following section.

3. EU enlargement in the shadow of Russia’s war

2023 was the year when the first progress reports were published for Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, providing a comparative picture with the countries of South-East Europe for the first time. This marked a significant shift in the EU’s enlargement discourse, as these former ENP countries were now firmly placed on the accession track. Reflecting this change in strategic priorities, the Commission’s 2023 communication emphasised this shift, stating:

The EU’s enlargement policy has already gained new momentum. A firm prospect of EU membership for the Western Balkans, Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia is in the EU’s very own political, security and economic interest and essential in the current geopolitical context.Footnote 52

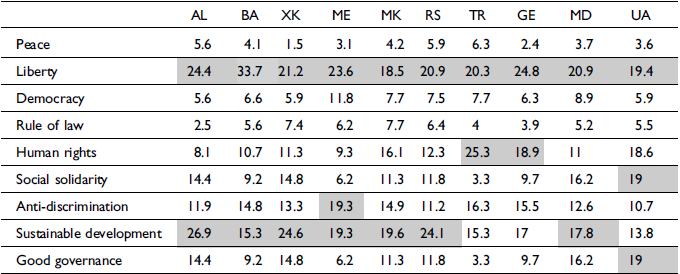

This statement demonstrates how enlargement has evolved from a primarily normative project into a central pillar of the EU’s geopolitical strategy. The explicit reference to security and economic interests underscores how enlargement is no longer framed solely in terms of democratic transformation, but rather as a means of enhancing the EU’s strategic position in an increasingly volatile geopolitical environment. In the first table, which shows the two most frequently mentioned norms of the NPE model per country, liberty stands out as the most frequently cited norm across almost all countries (Table 1). This suggests a regional emphasis on civil and political rights, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, possibly reflecting post-conflict developments and aspirations for stronger democratic governance. Sustainable development also ranks highly, particularly in Albania, Kosovo and Serbia. This suggests that, driven by the EU’s Green Deal agenda, the regional challenges of the green transition in the Western Balkans are growing.Footnote 53 Human rights are especially prominent in Georgia and Türkiye, reflecting domestic and international debates surrounding these issues, particularly in Türkiye’s case. These countries, including Moldova and Ukraine, show a moderate focus on good governance and social solidarity, indicating the ongoing challenges in improving governance structures and addressing social inequalities.

Table 1. Most frequently mentioned norms of the NPE model (in percentage)

Source: Own visualisation based on the 2023 progress reports.

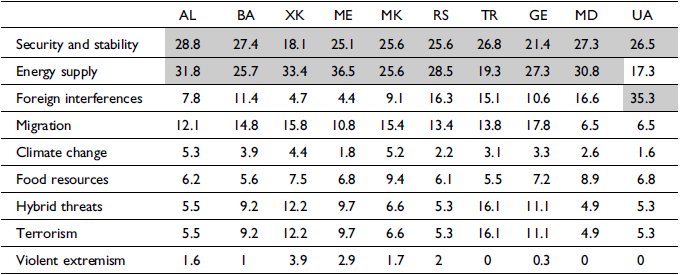

The second table, focusing on the GPU model norms, highlights energy supply as a critical issue, particularly in Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro (Table 2). This reflects the strategic importance of energy resources in a region heavily reliant on external suppliers.Footnote 54 Security and stability are also frequent norms, particularly in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Moldova. While Albania tends to be emphasised as a provider of security and stability in the region, there are more concerns about the internal constitution of both states in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Moldova.Footnote 55 Foreign interferences stand out significantly in Ukraine, reflecting the ongoing war with Russia and its heavy geopolitical repercussions. Migration, though important in countries like Georgia and Kosovo, is less dominant in overall concerns. Climate change, by contrast, appears as a low priority, with Ukraine and Montenegro showing minimal engagement on this issue.

Table 2. Most frequently mentioned norms of the GPU model (in percentage)

Source: Own visualisation based on the 2023 progress reports.

V. Discussion of results

The 2014 Crimea annexation impacted both the NPE and GPU models, but the 2022 invasion accelerated the EU’s enlargement reorientation. The data shows rising GPU priorities, particularly for Moldova, Ukraine, and the Western Balkans. This post-2022 increase highlights the growing importance of security and stability in the EU’s enlargement strategy. The war has pushed the EU to accelerate accession talks with Ukraine and Moldova, reflecting a recalibration towards geopolitical stability, while traditional normative benchmarks, such as anti-corruption and judicial independence, have taken a secondary role.

In the Western Balkans, NPE and GPU values have also fluctuated in response to regional and global crises. The post-2022 data indicates a rise in GPU values for these countries, pointing to a stronger focus on geopolitical concerns, particularly regarding Russian influence in the region. Overall, the war has intensified the EU’s shift towards a more geopolitically driven enlargement approach. While normative values remain central to the EU’s identity, the data suggests that enlargement is increasingly shaped by geopolitical considerations, particularly in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans, as the EU seeks to secure its borders against further Russian aggression.

However, rather than constituting a clear turning point, the data suggests that the EU’s enlargement policy is undergoing a significant critical juncture. This aligns with recent scholarship in the field, which argues that while geopolitical concerns have gained weight, they have not entirely replaced normative considerations.Footnote 56 This empirical evidence also supports the broader rethinking of EU enlargement discussed in this Special Issue, suggesting that the EU’s enlargement policy has adapted to new geopolitical realities but that this shift does not yet mark a complete transformation of its strategic direction.

VI. Conclusions and outlook

The Russian war against Ukraine has undoubtedly marked a significant shift in Europe’s geopolitical landscape, often referred to as a “Zeitenwende” by Former German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. This moment has pushed countries like Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia into the centre of the EU’s accession process, signalling a broader reorientation within the EU’s enlargement policy. However, rather than a full-scale turning point, this shift represents a recalibration of priorities, where geopolitical stability and security are taking precedence, but normative commitments to democracy, human rights and the rule of law remain integral to the process.

Historically, EU enlargement was driven by “normative power,” promoting democracy and human rights. The Ukraine war intensified strategic concerns, but normative and geopolitical considerations remain balanced. The case of Georgia exemplifies this dual approach: While the European Council acknowledged Georgia’s European perspective, its decision to delay full candidate status until democratic reforms progress underscores the EU’s insistence on upholding fundamental values alongside geopolitical considerations. While the idea of a “geopolitical” EU has gained traction, it remains conceptually fluid, and its integration into EU policy is still evolving.

Future research will need to focus on the long-term balance between normative goals and geopolitical imperatives: How can the EU sustain its commitment to democracy, the rule of law and human rights in its enlargement process, while responding to new geopolitical threats and security concerns? Another critical research area concerns the internal dynamics within the EU. How do different member states perceive the shift toward a more geopolitically focused enlargement strategy and could this lead to internal divisions, especially regarding the accession of countries like Ukraine and Moldova? Additionally, it will be important to examine how this geopolitical reorientation impacts candidate countries themselves. Does the increasing emphasis on geopolitical considerations alter the reform processes in these states and how does it affect their long-term integration into the EU? Finally, the concept of a GPU requires further theoretical development. To what extent can the EU translate its geopolitical ambitions into actionable policies and how will this affect its credibility and role as a global actor?

These questions align with the broader theme of this Special Issue, reflecting the ongoing need to balance normative ambitions with external security demands. Understanding the long-term implications of this shift – and how the EU navigates the dual objectives of norm promotion and geopolitical stability – will be crucial for shaping the future of EU enlargement policy.

Acknowledgments

This article has been written in the framework of the Horizon Europe project “InvigoratEU – Invigorating Enlargement and Neighbourhood Policy for a Resilient Europe.” The EU is not responsible for the content of this article, which expresses just the author’s opinion. The author declares that there are no competing interests.