Archaeology prides itself on its ability—unlike most text-based histories—to see beyond the urban elite. The study of the countryside and the poor, while never a main focus of research, has a long history, giving archaeology part of its broad perspective. Since the 1960s, women and gender have also received attention, and from the 1990s, perhaps as a natural development of this trend, children also came to the fore. The elderly, however, did not receive significant attention. Relatively few articles were devoted to this demographic group,Footnote 1 and even these groundbreaking studies examined the question from a specific angle (below). In this article, using an exceptionally detailed archaeological case-study and aided by ancient texts and ethnography, I would like to take a small step toward identifying the ‘elderly’ and ‘elders’ in the domestic sphere (households) of Iron Age Israel.

The archaeology of old age: an introduction

Despite the growing interest in society, including gender and children, ‘the old remain very under-studied’ (Appleby Reference Appleby2018, 145). The first article to deal with the topic was apparently published in 2001 (Welinder Reference Welinder2001), followed by only a trickle of publications, by Appleby (Reference Appleby2010; Reference Appleby2011; Reference Appleby2018) and others who mostly examined cemeteries (e.g. Fahlander Reference Fahlander2013; Ross & Oxenham Reference Ross, Oxenham, Oxenham and Buckley2015) and aspects of skeletal remains (e.g. Gowland Reference Gowland2007; Reference Gowland2015; Reference Gowland, Tilley and Schrenk2016).

The chronological age of the interred and their physical condition are indeed the most straightforward way to identify old age, and this should be accompanied by an understanding of their social status. Old age, after all, is not just a chronological issue, but also—and for our purposes mainly—a social status.

Understanding the social significance of being old has two aspects:

-

(1) From what age does one count as ‘old’;

-

(2) What does it mean to be old.

The second question is more significant for our purposes and will be elaborated below. As for the first question, the age from which an individual is regarded as being old varies between cultures. Identifying the age of the interred based on the skeletal remains alone is therefore insufficient to determine if they were regarded as old, let alone to understand the social position of the elderly within their society. When we possess large mortuary databases, we could create a demographic profile of the society in question, and attempt to correlate it with variables like the treatment of the body, its position, the grave goods that accompany it, the relations between it and other bodies/skeletons, the skeleton’s location within the tomb, the form of the burials, etc. If we could identify age-based differential treatment of the interred, we might be able to distinguish a group that was probably regarded as elderly. This would provide us with a sort of ‘emic’ perspective on what was regarded as old age within this specific society, and might also allow us to identify the social status of the interred, for example if old age is correlated with preferential treatment, or with poor treatment.

Still, mortuary data provide only partial information on society. Often, there are no such data, or they are too limited for quantitative analysis (e.g. Faust Reference Faust2004; Reference Faust and Beitzelin press and references; Ilan Reference Ilan and Meyers1997a,b). Moreover, mortuary data are often biased, with some groups being over-represented in the sample, whereas others are under-represented (even not represented), and the remains are sometimes influenced by world-views and do not necessarily reflect social reality or demography (cf. Faust Reference Faust2004, and references; McGuire Reference McGuire, Leone and Potter1988; Parker Pearson Reference Parker Pearson and Hodder1982; Reference Parker Pearson2000).

Finally, ‘old age’ is not only a chronological question, but also one of social status. The biological age is, of course, related to the status of the individual, but it is not the only determinant. Thus, while age is a physiological reality, being accorded the status of ‘old’, usually in a positive sense, is a social issue.

Indeed, as we will see below, (1) not every individual at a certain age is automatically an elder. An extreme example would be treatment of elderly servants and slaves as ‘boys’ (e.g. Deetz Reference Deetz1996, 112–14), a reality which is known also in Iron Age Israel, where the status of young age was similarly applied socially (e.g. Genesis 18:6; Borowski Reference Borowski2003, 102; Faust Reference Faust2002, 59). (2) There is also evidence for the opposite trend, in which individuals who are still relatively young are sometimes treated as elders due to their wisdom (cf. Mishnah Berachot 1:5).

We therefore distinguish between the elderly (the biological age that was defined as old at a given society) and elders (a more exclusive social category).

Background: the elderly and the elders in traditional societies and in ancient Israel

The elders in traditional societies

The status of the elders in traditional societies, although not uniform, was generally high (e.g. Keith Reference Keith1980, 339; Turnbull Reference Turnbull1985, 227-65; and below).

Eriksen (Reference Eriksen2015, 168) noted that ‘In many societies a person’s rank rises as he or she becomes older’. Similarly, Holy (Reference Holy and Spencer1990, 167) wrote that ‘With the exception of a few hunting and nomadic societies … the nonindustrial societies emerge as distinctly old-age oriented’ (see also Turnbull Reference Turnbull1985, 227-65; Welinder Reference Welinder2001, 170; and others).

Turnbull (Reference Turnbull1985, 227–8) noted that in cultures ‘with a firm belief in an after or other life, the old are accorded a position of often enormous respect and honor and are exploited for the social good until they die, when they continue to exploited as “ancestors”’. He noted the importance of their practical skills, adding that their political role is often formalized, since ‘their long years of experience being called on to help in the resolution of otherwise intractable disputes’—a quality that also makes them good educators. Turnball (Reference Turnbull1985, 233) added that ‘In all the societies we have discussed, the aged may be considered as repositories of the sacred’.

Eriksen (Reference Eriksen2015, 168) also noted that

Advanced age is often associated with deep experience, wisdom and a sound sense of judgement. In many societies, old men are the political rulers and old women are perceived as less ‘threatening’ than younger ones … Old women in some societies may exert more direct political power than young men.

These generalizations are clearly in line with the prevailing norms in the Middle East. Not only were the old respected for their wisdom, but they also held the traditional political and economic leadership. Families were led by the father(s), often the grandfather(s), who presided over the extended, multi-generational families (e.g. Abudi Reference Abudi, Badran and Moghadam2011, 35; Avitsur Reference Avitsur1976, 83–4, 87; Baer Reference Baer1973, 74–80). The larger kinship units were led by the tribe (among the Bedouins) or village elders (among the fellahs) (e.g. Baer Reference Baer1973, 141–2, 180; Bates & Rassam Reference Bates and Rassam2001, 256).

The elders in ancient Israel

Israelite society has received a great deal of scholarly attention (e.g. Bendor Reference Bendor1996; Borowski Reference Borowski2003; De Vaux Reference De Vaux and Mchugh1965; Faust Reference Faust2012; Reviv Reference Reviv1993; Schloen Reference Schloen2001). It is well known through excavations of dozens of sites, large and small, urban and rural, in which hundreds of structures were unearthed, providing information about various social segments. This is supplemented by a plethora of textual sources, including the Bible. While biblical-historical narratives are often suspect, the generic information they indirectly provide about society and culture is more reliable, and they can be viewed, broadly speaking, as indigenous accounts of long-term normative belief and custom (Bunimovitz & Faust Reference Bunimovitz, Faust and Levy2010; King & Stager Reference King and Stager2001, 7). In this case, the pervasiveness of the relevant information in all biblical genres reflects perspectives common over long periods,Footnote 2 and is in line with the information available from other traditional societies.

Ancient Israel was a male-dominated (commonly labelled patriarchal), patrilineal and patrilocal society (e.g. De Vaux Reference De Vaux and Mchugh1965; Faust Reference Faust2012; Reviv Reference Reviv1993; Schloen Reference Schloen2001). While society went through various changes over time, the ideal basic social unit was the bêt ʾab (literally ‘house of the father’, meaning an extended family). Each such unit was headed by the ‘father’, but since these were multigenerational families, the term often refers to the ‘grandfather’ (the ‘patriarch’). These families were part of larger units, which the sources call mišpāḥāh (probably a lineage). These units often functioned as territorial communities and were led by the elders (zĕqēnîm, literally old men),Footnote 3 comprised by the heads of the different households (e.g. Bendor Reference Bendor1996; De Vaux Reference De Vaux and Mchugh1965; Faust Reference Faust2012; Reviv Reference Reviv1989; Reference Reviv1993).Footnote 4

We will elaborate later on the role of texts in archaeological reconstructions, but should note that the information gained from them is not only generic, but is in line with the information gleaned from other ancient Near Eastern societies, and from ethnography at large. And while it is true that the texts, biblical and others, were largely written by older males, and hence represent a biased perspective, this in itself says something about the elders’ social position. Moreover, the information is derived from various genres, including stories that probably resonated with larger audiences. And while ethnography (above) is also largely male-biased, the pervasiveness of the picture about the status of the old seems to support the perspective presented here.

A preliminary note on terminology

As in other societies, the terms ‘fathers’ and ‘elders’ should often not be taken literally, and commonly refer to a social status or even situation.

Thus, while the term elder (zāqēn, sing; zĕqēnîm, pl.) can imply a person of old age (e.g. Genesis 18:13, 27:1-2; I Samuel 2:22, 8:1), often it refers to a leading position in the community (e.g. Exodus 24:14; Deuteronomy 19:12, 22:16, 29:9; I Kings 12:6, 13; II Kings 10:1; Isaiah 3:2; cf. Conrad Reference Conrad1980). As Conrad (Reference Conrad1980, 123-4) noted, ‘Linguistic usage by and large makes a clear distinction between the man characterized by his age, and the elder’. The same is true when we descend the social scale, and the words na‘ar/na‘ara (literally boy/girl or youth male/female) are also used to designate servants and slaves, regardless of biological age (e.g. Genesis 18:7; 41:12; Exodus 33:11; Judges 9:54, 16:26; I Samuel 20:21, 36–8, 40).

Likewise, although the term father (ʾab) could refer to anyone who fathered children (e.g. Genesis 19:37–8, 28:2; Exodus 20:12; Isaiah 38:19; Ezekiel 22:7), in social contexts it refers to a high social status of a father (head) of a household (e.g. Genesis 45:8; Judges 17:10, 18:19; II Samuel 7:14; Isaiah 22:21; Jeremiah 3:4, 31:8; Psalms 78:6). Thus, in an extended family of three generations, for example, there could be between three and six males who fathered children, but only one household’s ‘father’.

The fathers and the elders

The father had wide authority over the other members of the household (e.g. De Vaux Reference De Vaux and Mchugh1965, 19–21; Faust Reference Faust2012, 12–13; Malul Reference Malul2002, 347–74; Niditch Reference Niditch1997, 86–7; Reviv Reference Reviv1993, 44). The ‘fathers’, as a collective, were called elders (zĕqēnîm; always in the plural, and see Reviv Reference Reviv1989, 11), and acted as the traditional leadership of kinship units and settlements in ancient Israel and in the ancient Near East at large (e.g. Matthews & Benjamin Reference Matthews and Benjamin1993, 122; Reviv Reference Reviv1989, 11; Reference Reviv1993, 54), serving as judges and local leaders (see references above and also e.g. Conrad Reference Conrad1980, 127–31; De Vaux Reference De Vaux and Mchugh1965, 137–8, 152–3; Reviv Reference Reviv1989; Reference Reviv1993).

The mothers

Women rarely filled public roles in such a male-dominated society, and the public space was probably regarded as male (e.g. Faust Reference Faust2002, 60 and references; cf. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977, passim; Eriksen Reference Eriksen2015, 160–61). Still, the limited data supplied by the sources (e.g. Meyers Reference Meyers2013), along with ethnographic information (e.g. Eriksen Reference Eriksen2015, 168, and above), suggest that many enjoyed a high status within the households, in relation to their children and their daughters-in-law. Meyers (Reference Meyers2013, 188) noted that ‘senior women, especially when extended or complex families are involved, held what today we would call managerial roles’.

The archaeology of the elders in ancient Israel, Take 1

The city gate

But where are we supposed to find the elders? Sources suggest that, as a group, they were active at, or near, the city gate (e.g. Joshua 20:4; also Deuteronomy 21:18–19; 22:15; 25:7; Ruth 4:1; Lamentations 5:14, and more). Many Iron Age gates were excavated (Figs 1, 2), and the gate’s various roles have been thoroughly studied (e.g. Blomquist Reference Blomquist1999; Cogan Reference Cogan and Tadmor1982; Faust Reference Faust2012, 100–109, and additional references; Herzog Reference Herzog1976). The gate and the open square in front of it were the most appropriate place for public activities involving a large number of people (e.g. Cogan Reference Cogan and Tadmor1982, 231–6; Herzog Reference Herzog1976), serving as a ‘focal point for public life in the city’ (Cogan Reference Cogan and Tadmor1982, 232). This was the most public location, as everyone coming in and out of the settlement had to pass there. It served as a place of justice, where legal proceedings took place, and where punishments were executed. There is also evidence for commercial activity in the city gate, the natural arena for such activity, and many noted that it also served as a place of worship (e.g. Cogan Reference Cogan and Tadmor1982, 236; Emerton Reference Emerton1994).

Figure 1. Plan of Beersheba (level II). A small, planned urban centre in Judah. (Courtesy of Ze’ev Herzog.)

Figure 2. One of the chambers of the Beersheba city gate. (Photograph: Avraham Faust.)

It is therefore not surprising that the elders, as a group, were active in the gate area. Men were apparently expected to stay outside the home most of the day (cf. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977, 123) and therefore stayed in the public (male) space (cf. Eriksen Reference Eriksen2015, 160–61; Faust Reference Faust2002, 60 and references), hanging together. This is a suitable place for people who do not do physical work (either temporarily due to the weather/season, or permanently due to age or physical conditions), but who want to see and be in ‘control’, and to be seen.

Still, although the elders were active in the gate area, and scholars pointed to the benches unearthed in the city gates’ chambers (Fig. 2; Herzog Reference Herzog, Kempinski and Reich1992, 271; Matthews & Benjamin Reference Matthews and Benjamin1993, 122) or to the entire city gate complex (including adjacent structures) as the arena for public action (e.g. Faust Reference Faust2012), no evidence for the elders was yet identified there.

Iron Age cemeteries

While the simplest path to identify the elderly (i.e., chronological age), and sometimes even elders (i.e. social age), is to examine mortuary data, this is impractical for our purposes.

First of all, for most of the Iron Age we lack substantial mortuary data from Israelite settlements (Faust Reference Faust2004; Faust & Safrai Reference Faust and Safrai2022 and references; Ilan Reference Ilan and Meyers1997a, 385; Reference Ilan and Meyers1997b, 220).

And while hundreds of burial caves are known from eighth- to seventh-century bce Judah, they (1) represent only part of the population and (2) the skeletons were transferred to repository pits for second burials, where all the bones were ‘mixed’, preventing us from identifying the old (and their treatment).

The archaeology of the elders in ancient Israel, Take 2: the father and mother in Building 101 at Tel ʿEton

The following will focus on the study of the fathers and mothers at home, zooming in on building 101 at Tel ʿEton, which provides a uniquely detailed case-study (e.g. Faust Reference Faust2019a,b; Faust & Katz Reference Faust and Katz2017; Faust & Sapir Reference Faust and Sapir2018; Reference Faust and Sapir2021; Faust et al. Reference Faust, Katz and Sapir2017; Faust Reference Faustforthcoming; Sapir et al. Reference Sapir, Avraham and Faust2018).

Tel ʿEton

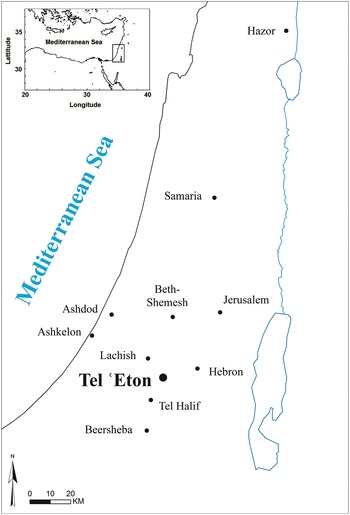

Tel ʿEton is located in the southeastern Shephelah, Israel (Fig. 3). The site was occupied intermittently from the mid-third millennium until the third century bce. The main occupation revealed in the excavations is a massive eighth-century bce destruction layer, inflicted by the Assyrian army. Among the remains from this phase is Building 101, excavated in its entirety in the uppermost part of the mound (Area A, Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Map showing the location of Tel ʿEton and additional sites in the region.

Figure 4. Tel ʿEton, with excavation areas. (Prepared by Segev Ramon.)

Building 101

Building 101 (Fig. 5) belongs to the well-known longitudinal four-space (LFS) or four-room house type (e.g. Faust & Bunimovitz Reference Faust and Bunimovitz2003; Reference Faust, Bunimovitz, Albertz, Nakhai, Olyan and Schmitt2014; Netzer Reference Netzer, Kempinski and Reich1992; Shiloh Reference Shiloh1973; also Hardin Reference Hardin2010). The entrance to the building was from the east, into the long courtyard, that was paralleled with the two additional long spaces (each divided into smaller rooms) to its north and south, and which led to a broad space (divided into two rooms) at the back. It was built almost parallel to the east–west axis, and its (ground floor) area is about 225 m2. The foundations and the lower courses were constructed of stones, and the upper courses (of the inner walls) were made of mud bricks. The construction was of high quality, included masonry stones in the corners and entrances, and part of the building was covered with a second story.Footnote 5 While the building’s location, size, quality of construction, etc., suggest that it was an elite residence, this was nevertheless the dwelling of a (large and wealthy) family (Faust et al. Reference Faust, Katz and Sapir2017), and is likely to be representative of many of the period’s large households.

Figure 5. Building 101, on the eve of its destruction by the Assyrian army in the late eighth century bce. (Prepared by Vered Yacobi.)

Analysing Building 101

Building 101 was excavated in its entirety in the course of 10 seasons. The material was sifted using a 0.5×0.5 cm metal mesh, and all the finds were recorded with their exact location, using ArcGIS program. Large segments of the floors were excavated using a grid of 20×20 cm, and every vessel that was identified in situ was excavated separately as a unit of its own. Every sherd—including body sherds—was registered, allowing us to reconstruct the breaking patterns and to identify post-depositional processes. All in all, nearly 500 artefacts along with almost 200 complete pottery vessels (and numerous other finds) were found in an excellent state of preservation, enabling us to study the building in depth. Although the building was erected already in the tenth century (e.g. Faust & Sapir Reference Faust and Sapir2018; Reference Faust and Sapir2021), and the inner spaces experienced some changes over the years (e.g. Sapir et al. Reference Sapir, Avraham and Faust2018), in this article we focus on the final phase of the building. The finds from this phase were buried within a massive destruction layer that, in addition to providing a secure dating (and ensuring that the finds are contemporaneous), also enable us (cautiously) to reconstruct how the large household functioned on the eve of the structure’s destruction (the summary below is based mostly on Faust et al. Reference Faust, Katz and Sapir2017; see also Faust Reference Faust2019a,b; Faust & Katz Reference Faust and Katz2017).Footnote 6

The Courtyard (Fig. 5)

When the building was destroyed, the courtyard was divided into three sub-units. The ceramic vessels were quite scattered, and some of them probably fell from the second floor that partially surrounded it.

Space A1: Very few in situ vessels were found in this space, but it is worth noting a relatively large concentration of astragali, as well as a few pieces of worked, decorated bone.

Space A2: Only a few vessels were found in this space, but 66 loom weights were unearthed in one batch in its eastern part. An additional 21 loom weights were found nearby, either in the same space or in the northwestern part of space A3. It appears that at least two looms stood here (cf. Miszk Reference Miszk2012, 120–23 and references).

Space A3: nine vessels, including bowls, juglets, storage jars and a stand, were unearthed around a plastered installation. Three additional vessels were found in the northwestern part of this space.

The northern sector

The rooms in the northern sector were used for storage. The finds in room D, below a layer of chalky material (apparently the remains of the ceiling), included smashed storage jars, uncovered with the remains of their contents still inside, mainly olive pits, grape stones, lentils, and even bitter vetch. Wheat, probably stored in sacks, was found on the floor. Between the jars were additional finds, including a few juglets. The finds that are associated with the ground floor included eight storage vessels, three bowls, three jugs, four juglets, one lamp, and more. Additional vessels were unearthed in the debris of the second story (above the chalky material), including bullae/sealings.

Room E was also used for storage, and nine storage vessels were unearthed there, along with a few smaller vessels. Room F was pretty small, and the finds were more limited, including only one large storage jar, and additional smaller vessels. The finds in Room G included seven storage jars, a krater and a funnel, along with one cooking pot and one juglet, hence indicating that the room was used almost solely for storage. Below the vessels and above the floor, large quantities of wheat, apparently stored in sacks, was uncovered.

The southern sector

The southern sector had far fewer ceramic finds, and it appears that it served different purposes.

Room I was used for food preparation, as the finds included six cooking pots, along with other small vessels (and only three storage jars and one hole-mouth jar). The finds also included a small square installation, and attached to it were the poorly preserved remains of what might have been an oven or a similar installation. These, and the fact that this is the highest concentration of cooking pots in the building, suggest the room served for food preparation. Additionally, 41 loom weights were unearthed in the southeastern part of the room, indicating that weaving also took place here. Both food preparation and weaving were regarded as women’s work in the ancient Near East in general, and in Iron Age Israelite society in particular (e.g. Meyers Reference Meyers2013, 128–33; also Borowski Reference Borowski2003, 31–2; Faust Reference Faust2002 and references; Singer-Avitz Reference Singer-Avitz, Yasur-Landau, Ebeling and Mazow2011, 292–3), and both often took place in the same space, allowing for better use of space and time (Aizner Reference Aizner2011; Meyers Reference Meyers2013, 133). Additionally, a few astragali were unearthed in this room, probably resulting from children’s play (cf. Gilmour Reference Gilmour1997 and references). The room, therefore, served what was regarded as female activities, including food preparation, weaving and child-care. The nearby courtyard was apparently an extension of this room (below).

Room J was a large room that was found devoid of complete vessels. The total absence of ceramic vessels in the room, especially given its large size and the high frequency of vessels in the other rooms, has been discussed at length elsewhere (Faust Reference Faust2019b,c; Faust & Katz Reference Faust and Katz2017), and we have suggested that the room was used to house individuals who were in the state of impurity. Both archaeological evidence and biblical testimony suggest that in Israelite society pottery was regarded as a potent material that could not be purified (e.g. Leviticus 6:21; 11:33, 15:12; Numbers 31:20-24; see also Faust Reference Faust2019c), and it was therefore counter-productive to give it to unclean people. This is supported by the wood (charcoals) assemblage unearthed in this room, which was the most varied in the house, suggesting that the inhabitants used wooden vessels.Footnote 7 This interpretation of the room is also in line with some unique features of biblical purity laws. While purity laws, including restrictions on menstruating women, are practically universal (e.g. Buckser Reference Buckser, Levinson and Ember1996; Frandsen Reference Frandsen2007; Small Reference Small1999; Strassmann Reference Strassmann1992), biblical purity laws are somewhat unique in allowing unclean people to stay in the house (usually, such persons are expected to relocate; cf. Milgrom Reference Milgrom1991, 952–3; Galloway Reference Galloway, Classen and Joyce1997).

This interpretation is further supported by the discovery of an 80×90 cm crushed limestone surface at the entrance to the room, extending slightly into the courtyard, at the edge of which a basin made of soft limestone was uncovered. The surface and the basin apparently served in the washing ritual (Faust & Katz Reference Faust and Katz2017). Additionally, the location of the room, near the entrance to the building, allowed easy access and prevented potential interaction between clean and unclean individuals,Footnote 8 whereas the form and the placement of the door meant that most of the room could not have been viewed from the courtyard, providing privacy (cf. Bafna Reference Bafna2003; Hanson Reference Hanson1998; see Faust & Katz Reference Faust and Katz2017).

The southern sector housed humans and human activities, and it is worth noting that a bench accompanied the entire southern wall, enabling sitting or working. Since most of the unclean people (Room J) were menstruating women, and as food preparation and weaving—as well as child-care (Room I)—were regarded as feminine activities, the southern sector should apparently be viewed as female.

The western sector

The western sector was composed of two rooms.

Room C, in the northern part of the sector, was used for storage, and some 38 storage vessels were found there, along with an oil lamp and a funnel. Various lines of evidence, including the complete absence of botanical remains and the nature of finds that were unearthed within a few of the vessels, along with the type of funnel discovered (see also Faust Reference Faust2019a) and the fact that this is the only room that did not face direct sunlight (and hence the coolest), suggest that this room was used to store liquids (Faust et al. Reference Faust, Katz and Sapir2017, 157, 161).

Room B, in the southern part of the sector, had far fewer finds, and only eight vessels and a ceramic footbath were unearthed inside it, along with an oil lamp that was discovered in the doorway. In the southern part of the room, one could see the above-mentioned bench, as well as a small stone platform. We will elaborate on this room below.

The western sector was therefore also divided between north and south; the finds uncovered in the northern room are similar to those found in the northern sector (storage), while the finds in the southern room are similar to those unearthed in the southern sector (other human activities).

Who lived in the house? On the nature of the household occupying Building 101

Despite the impressive architecture, the house served as the abode of a family. Given the size of the building (225 m2 gross; 121 m2 net on the ground floor during the last phase) and the finds unearthed, it is quite clear that this was an extended family (cf. Faust Reference Faust2012, 110–12, 159–63; Yorburg Reference Yorburg1975).

While different density coefficients were presented (e.g. Brown Reference Brown1987; Ember & Ember Reference Ember and Ember1995; Naroll Reference Naroll1962; Watson Reference Watson1979, 191), even opting for the lowest one would mean that the structure housed a family of a few generations. Whether one wishes to examine the gross area of the house, the net area, or even the net roofed area (67–67.6 m2 on the ground floor), the figures are sufficient for a large family, especially given the existence of a second storey. Moreover, the house should not be viewed in isolation, as it is part of a large group of Iron Age LFS houses, 99 per cent of which were smaller, usually much smaller (see Faust Reference Faust2012, esp. 207–12; also Hardin Reference Hardin2010, 171–3; Zorn Reference Zorn1993, 300). Hence, even if one wished to reject all the suggested density coefficients, claiming that density is culturally specific, the relative size of Building 101 (compared to hundreds of other such houses) indicates that a large family dwelt in it.

Moreover, the actual evidence unearthed within the building, for example the finding of the remains of at least three looms, indicates that at least three adult (married?) women lived in the house (for the association, see Faust Reference Faust2002; Malul Reference Malul1996; see also Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977, 135–7, 144; Meyers Reference Meyers2013, 133, 141). The magnitude of the surpluses that were stored in many dozens of storage vessels (and in sacks) also greatly exceeds the needs of a nuclear family.

Finally, we have evidence for changes in the inner division of the house over time, suggesting that it housed an extended family with changing needs (e.g. Faust et al. Reference Faust, Katz and Sapir2017, 147, 149, 150, 166, 169; Sapir et al. Reference Sapir, Avraham and Faust2018).

‘When brothers live together’: family usage of domestic space

But what were the sleeping arrangements within the building? The ethnographic literature provides a wealth of examples in which many inhabitants (including separate nuclear units) jointly shared one sleeping space, and others in which different internal spaces served different nuclear families.

Hirschfeld’s study of traditional Arab houses provides examples of 15–20 people living in one space (Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1995, 182, 187), and instances in which each nuclear unit had its own, separate unit (Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1995, 167–77, and also 193–206). Hirschfeld (Reference Hirschfeld1995, 258–9) notes that Roman-Byzantine houses usually had several living rooms.

Similar situations are recorded elsewhere in the Middle East. Watson (Reference Watson1979, 282, also 292), in her detailed ethnoarchaeological study in Kurdistan, noted that sleeping in the same room was common, whereas Oliver (Reference Oliver2003, 163) provides an analysis of a western Anatolian farmhouse in which married sons had their own rooms.

Similar examples can be brought from other parts of the world. Crouch & Johnson (Reference Crouch and Johnson2001, 68–9) provide examples for the use of one room for sleeping in Japan, but for the use of separate bedrooms among relatively wealthy inhabitants of houseboats in Kashmir (Reference Crouch and Johnson2001, 143) and in Nepal (Reference Crouch and Johnson2001, 252). One sleeping space was also reported in Igloos (Oliver Reference Oliver2003, 24), while in parts of Africa, when polygamy was common, there were separate huts for the different wives (e.g. Oliver Reference Oliver2003, 76, for the Maasai).

Ethnography, therefore, suggests that sometimes members of the household shared one living room, whereas in other cases each nuclear unit had its own separate space. It appears that beyond social norms, wealth and ability played a role, and the larger the house, the more possibilities for separation it provided.

Given the size of Building 101, the large number of rooms it contained (nine on the ground floor alone), and the evidence presented above for dividing spaces, it is clear that the different nuclear units lived in separate rooms (cf. Blanton Reference Blanton1994, 64).

Living in Building 101: Room B and its inhabitants

It is not easy to define a living-room assemblage (also Hardin Reference Hardin2010, 136–7), and it is simpler to define assemblages that serve other purposes. Thus, the five rooms in the north (including Room C) served for storage of various types, whereas the open courtyard served various activities, but not for sleeping. And the same applies to the rooms in the southern wing. Here, one room served for food preparation and the other, which was devoid of ceramic finds, apparently served to host impure individuals (especially women during menstruation or after childbirth). While the latter interpretation can be questioned, the lack of vessels indicates that the room did not serve as a sleeping and eating space. Room B is therefore the only room on the ground floor that could have served such a purpose. Additionally, it is likely that second-storey rooms also served for sleeping (cf. Borowski Reference Borowski2003, 18–19; King & Stager Reference King and Stager2001, 35; Netzer Reference Netzer, Kempinski and Reich1992, 199).Footnote 9

Let us zoom-in into Room B (Figs 6–7).

Figure 6. Plan of Room B, with the distribution of the main finds (see also Table 1). (Prepared by James McLellan.)

Figure 7. An aerial image of Room B, after the conclusion of the excavations in 2015. Note that the platform was already removed when Square O22 was exposed, and is therefore not visible in the picture (although its contour is visible, since the rest of the room was burned during the destruction, and hence its colour is different). (Photograph: Skyview.)

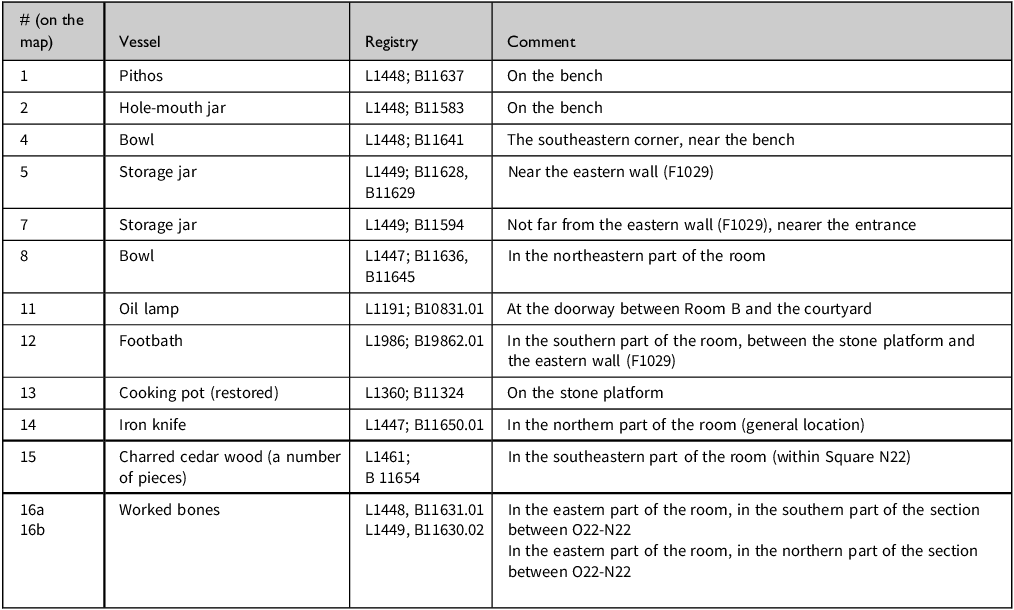

The ceramic finds, as identified in situ during the excavations, include a cooking pot, a pithos, two bowls, two storage jars, one hole-mouth jar and one oil lamp (unearthed in the doorway, by courtyard A1). A restorer examined the assemblage of sherds, adding only one probable (third) bowl, and perhaps also a jug (the vessels were not yet restored). Additional finds worthy of note include a ceramic footbath, an iron knife and a few pieces of worked bone (Figs 6, 8 & 9; Table 1). The finds in the room could clearly serve for “living”, i.e., the room could have been used for sleeping and eating, and even hosting family “guests” (probably other members of the kinship group).

Figure 8. The footbath. (Photograph: Avraham Faust.)

Figure 9. An Iron Knife from Room B. (Photograph: Avraham Faust.)

Table 1. Distribution of the Main Finds in Room 101B.

Note: The initial figures (#1–10) were allocated during the 2015 season (when most of the room was excavated) to vessels (or sherd concentrations suspected to be vessels) identified in the field (the identification of the vessel type is based mostly on the field observations). Some of the vessels were later ‘cancelled’ (#3, 6, 9), either because two such concentrations proved to be part of one vessel or because restoration showed that it was not a vessel after all. Another vessel (#10) seems to have fallen from the second storey, and is therefore not discussed here. To the 2015 listing we added three vessels that were discovered before this season, including an oil lamp (#11) that was discovered in the doorway leading to the courtyard, a footbath (#12) that was found on the floor after robbers pulled its pieces from the baulk (section) after the 2014 season (its location is marked at the place where the robbery was visible), and a cooking pot (#13 excavated in the 2014 season). Also added are an iron knife (#14) and the charred cedar fragments (#15). The location of the latter two is based on the basket number, and is only schematic. We should note that the restorer identified at least one more bowl, and perhaps also a jug, but as they were not identified in the field, they are not marked on the map.

The finds provide additional evidence for the identity of the room’s inhabitants:

-

• The unique footbath (Fig. 8) suggests that the room was used by individuals of higher than usual status. The various sources, both from ancient Israel and the ancient Near East (and the ancient world at large), indicate that footbaths had an important role, serving in washing the feet before going to sleep, but also for meals and hosting guests (cf. Genesis 18:4, 19:2, 24:32; 43:24; Judges 19:21; I Samuel 25:41; see also Psalms 60:8; 108:10). Despite their importance, however, footbaths are rare and appear to be associated with higher status (see also King & Stager Reference King and Stager2001, 70–71; Nuefeld Reference Nuefeld1971, 51),Footnote 10 and perhaps even symbolized the head of this rich household (the ‘official’ host). Its daily use might have been a special ‘treat’ of the father, and it was likely ‘associated’ with the patriarch.

-

• The vast majority of the 300 charcoals from the building (analysed by Dafna Langgut) were of olive (see Faust et al. Reference Faust, Katz and Sapir2017, 146). Three samples proved to be of imported cedar wood (1 per cent of the total), and all three were found in the southeastern part of Room B (L1461). These were most likely the remains of prized furniture, serving as another indication for the status of the room’s inhabitants.

-

• Two pieces of a worked bone were unearthed in the room’s eastern part (Fig. 6). We note that a larger concentration was found in the courtyard, mostly in the nearby space A1, and it is possible that some of them served as inlays, covering boxes or perhaps (but less likely) furniture, such as a chair (cf. Naeh Reference Naeh, Finkelstein and Martin2022, 472–3 and references).

-

• The large iron knife (Fig. 9) unearthed in the room, while not a crucial piece of evidence in itself, fits the other lines of evidence and further associates the room with eating.Footnote 11

The importance of the room is supported also by a number of architectural features:

-

• The room contained a unique stone platform (Figs 5–6). While the causes for its erection were complex (Faust Reference Faustforthcoming), it served as a convenient working area, and perhaps even for eating and sleeping (the cooking pot was discovered on top of it).

-

• The bench along the southern wall also enabled convenient sitting and could serve various activities as a sort of a table (the pithos and the hole-mouth jar were discovered on it).

And this is further supplemented by some broader architectural considerations:

-

• Room B is the largest room in the building (net 16.7 m2).

-

• The room has an excellent view. It is one of the two rooms from which the entrance is visible (Fig. 10; the other was used for storage and was packed with vessels), enabling anyone sitting in it to see everything that goes on in the courtyard, and who is coming in and out of the building. Naturally, unless the inhabitants close the opening, the entrance to the room is also visible to anyone in the courtyard. Hence, the room has high visibility in both the active and passive sense.Footnote 12

-

• The room is located next to Room I, where the mother of the house was preparing the food, and where ‘her’ loom was standing (see below).

Figure 10. Viewshed of structure 101, as seen from Room B. (Prepared by Vered Yacoby and Dvir Rotem.)

While the first points stand on their own, testifying to the importance of the room and its inhabitants, the last point also contributes to our understanding of the use of space in the building at large. During the last phase of the house’s existence, the part of the courtyard that was adjacent to rooms B and I was blocked by very shallow partition walls, creating Space A1 (Fig. 5). These walls were probably built on the eve of the destruction, when more people perhaps entered the house, but regardless of the exact circumstances of their erection, they were too low (especially wall F1041; Fig. 11) to prevent someone from entering this part of the courtyard or even blocking view. One may also wonder why no opening was left in this shallow wall (see Figs. 5, 11). We suggest that F1041 was built to prevent toddlers from wandering from their ‘ward’. Interestingly, in large households, the children were often guarded by their grandmother (the ‘mother’ of the household), freeing the biological mothers (her daughters in-law) to do other work (e.g. in the fields) (Scott-Kincheloe Reference Scott-Kincheloe1984, 121–2; cf. Meyers Reference Meyers2013, 137). The rarity of (breakable) ceramic vessels in this part of the courtyard supports this interpretation. In other words, Rooms B and I functioned, together with courtyard A1 as a separate ‘unit’, and I propose that Room B was the room of ‘father’ and the ‘mother’ of the house, where they slept and sometimes ate and even entertained ‘guests’ (such as were allowed to enter the inner parts of the structure, e.g. kin who lived elsewhere). This insight might also explain the storage jar that was embedded in the floor near the entrance to the room (see its base in Fig. 11), and could have served as a permanent source of water for the ‘grandparents’ and the guests. The room was also farther away from the other rooms, providing some privacy.

Figure 11. Square N23 (looking west, taken during the 2007 season), showing part of the courtyard and the entrances to Rooms B, C and D. Note the low partition wall that divides the courtyard (F1041), abutting its western wall, and the storage jar’s base, embedded into the courtyard’s floor near the entrance to Room B. (Photograph: Avraham Faust.)

The father spent most of his time outside the house, either at work or with the elders, and it is even likely that staying too much at the house was viewed negatively (cf. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977, 123). But when he was at the house, he either stayed near the entrance, perhaps outside in the front courtyard, or, when he was actually at home (either in the evenings, or when old), he spent time in Room B, where he also entertained ‘guests’, either other members of the household or even other family members who lived elsewhere, and from which he could ‘supervise’ everything.

It appears, therefore, that the older couple lived in Room B. The adjacent Room I was the territory of the ‘mother’, in which food was prepared, and where her loom was standing, and where she looked after the small children—activity that extended into Space A1. This partially ‘enclosed’ segment of the courtyard was indeed part of the old couple’s ‘suite’.

Where did the older couple sleep: a technical note

We have seen that the ground floor included only one possible living (sleeping) room. But what about the second storey? It is commonly thought that this is where most people slept (e.g Borowski Reference Borowski2003, 18–19; King & Stager Reference King and Stager2001, 35; Netzer Reference Netzer, Kempinski and Reich1992, 199, and see above), and there must have been additional living rooms there. So, can we not expect the older couple to live in the second storey?

The mere existence of a second storey, and the fact that this is where most of the household’s members slept, only accentuates the importance of the ground floor’s living room, and the likelihood of the above reconstruction.

After all, there were no stairs in this large house, and the second storey was reached by ladders (Faust et al. Reference Faust, Katz and Sapir2017, 158; cf. Netzer Reference Netzer, Kempinski and Reich1992, 197). But the elders, at least from a certain stage, could not easily (and frequently) climb a ladder. Thus, the only room on the ground floor that served for living must have been used by the older couple, strengthening the above-mentioned lines of reasoning.

The elders in Building 101: archaeology’s contribution to the understanding of Iron Age lived experience

In the main body of the article we reconstructed a detailed picture of the lives of the elders in traditional societies on the basis of various (textual and ethnographic) sources, and then attempted to identify them in the archaeological record.Footnote 13 Since archaeologists have largely ignored the elderly, their mere identification is an important accomplishment, and this was the initial aim of this paper.

Hower, the study of Building 101 furnished us with insights into the lived experience of the old which go beyond ‘confirming’ the information that is usually provided by the texts and ethnography. Thus, while the location of the elder couple in an inner room on the ground floor, visually controlling the entire courtyard and the entrance to the building, could perhaps be ‘expected’, it is by no means explicit in any of the sources, and in itself provides some insights on the status of the elderly within the household. Moreover, the study of the finds in the nearby spaces teaches us about the elders’ association with other activities, and therefore about various aspects of their daily life. Among other things, the material evidence shed further light to the role and position of the grandmother (the ‘matriarch’), which received far less attention in the (typically androcentric) texts. The physical position of the elders’ room, forming a separate suite that includes also the room in which food was prepared and the part of the courtyard in which small children were apparently looked after, highlights her important position, and marks the grandmother’s realm.

Similarly, the material evidence reminds us of some biological factors that were not mentioned in the limited biblical evidence, and are not often explicitly addressed by the ethnographic evidence, i.e. the limitations old age imposes even on the household’s leaders. In this case, the fact that the grandparents lived on the ground floor, whereas most living spaces were located on the upper storey, is a reminder of the physical difficulties that old age brings with it.

The above are but examples of the ways in which archaeology better articulates the lived experience of the elders, which together with other aspects (like hosting guests) opens the way for broader studies, that should incorporate additional structures and will increase our understanding of the way the old lived in the past (more below). As Nevett (Reference Nevett2023, 26) noted, ‘housing can be used actively as a tool for understanding … society, rather than simply to illustrate social-historical accounts based on texts’ (see also Alston et al. Reference Alston, Baird, Pudsey, Alston, Baird and Pudsey2022, 8).

The archaeology of old age: summary and conclusions

Despite the important role of the elders in traditional societies, and although paying significant attention to other social segments, including women and children, the old did not attract much archaeological interest. The few exceptional studies that examined this important group focused on mortuary data, and on evidence relating to the ‘body’ of the elderly.

Above I argued that these important studies are only a first step in a long journey. Not only is it not always easy to identify the biological age of the interred (but see Appleby Reference Appleby2018; Cave & Oxenham Reference Cave and Oxenham2016), but defining old age is also a cultural issue, and not every old person was regarded as an elder. Furthermore, mortuary data is often completely missing, and when it exists, it is often partial.

Subsequently, in most cases, we must study settlements and houses to identify the old and to understand their social role. However, studying the elderly and the elders in their daily setting is far more difficult, even when compared to the study of gender and children. The study of women, despite the difficulties involved, is somewhat simpler as in traditional societies women were usually associated with some activities that can be identified archaeologically, and often with items that symbolized them. Moreover, some of their ‘attributes’ in traditional societies are also related to biology, for example to birth and child nursing, or to menstruation (e.g. Eriksen Reference Eriksen2015, 156–8; Galloway Reference Galloway, Classen and Joyce1997; Small Reference Small1999; Strassmann Reference Strassmann1992). Even the study of children, which is notoriously difficult (e.g. Baxter Reference Baxter2005; Crawford et al. Reference Crawford, Hadley and Shepherd2018; Kamp Reference Kamp2001), is still influenced by biological factors, since at least in very young age children have to be cared for. And while almost every item can be used by children as a toy, such objects can sometimes be identified (e.g. Baxter Reference Baxter2005, 41–50, 77–8; Crawford Reference Crawford2009). The study of the elderly is trickier since there are hardly any artifacts that are associated only with old age.

In this article, based on Israelite society—for which we possess uniquely rich sets of data—we attempted to identify the ‘elders’ and especially the ‘fathers’ (i.e. the heads of the households) and the ‘mothers’. No relevant mortuary data is available, and while we know that the elders, as a group, were active near the gate of settlements, in this article we focused on the domestic context, i.e. ‘the house of the father’, taking advantage of the uniquely detailed information from Building 101 at Tel ʿEton—a large, two-storey building which housed an extended family.

We examined the architecture of the building and scrutinized the finds to reconstruct the use of space when the house was destroyed. The courtyard was divided into three parts by low partition walls, the innermost of which had no apparent doorway, but one of whose walls was very shallow and easy to go over. The evidence suggests that the five rooms in the north were all used for various types of storage activities, whereas the three rooms in the south were used for daily activities. The easternmost of these rooms was found devoid of pottery, and we suggested that it was used to host impure individuals, whereas the middle one was used for food preparation. This room also contained a loom, and we have evidence for children playing there, which extended into the nearby (innermost) part of the courtyard (Space A1).

The westernmost room (B) of the southern row was the only room on the ground floor that could have been used as a living room, i.e. as a space for sleeping. While most of the inhabitants probably slept on the upper floor, various lines of evidence suggest that Room B was the room of the ‘father’ and the ‘mother’, i.e. the patriarch and matriarch of the extended family.

The fact that this is the only room on the ground floor that could have been used as a living room already suggests that it was the room of the older couple, as access to the second story was via ladders and it is unlikely that the elderly couple was expected to climb up and down a couple of times a day.

This interpretation is also supported by other finds and by architectural evidence. Thus, in addition to pottery, this was the only room in which imported cedar wood was unearthed, most likely the remains of expensive furniture. Additionally, a footbath was unearthed in the room, not far from the cedar remains, indicating high status and perhaps an ‘attribute’ of the patriarch. The knife uncovered in the room could be associated with hosting (food), and so is the storage jar that was embedded into the floor near the entrance to the room. Two worked bones were also unearthed in the room, but it is especially worthwhile to mention the larger concentration of decorated worked bone unearthed in the courtyard (and mostly in space A1). Whether or not these might have been bone inlays, perhaps even the remains of decoration of furniture, they were clearly part of a unique object (or objects).Footnote 14

This was also the building’s largest room, and it had complete control (in terms of visibility) over the courtyard and the entrance to the building. Inside the room, a platform was built, and it could have served for sitting, eating and perhaps even sleeping. Additionally, the room is located adjacent to the room in which food was prepared, and both were connected to the innermost part of the courtyard, which was separated from the rest of the courtyard. This created a separate unit in which the patriarch and matriarch of the household conducted their activities, and where the (grand)mother was responsible for food preparation and caring for the young and educating them.

This is, of course, only a small step toward the study of the old, and I hope that in the future the information from additional houses will be studied, providing additional insights into the world of the old. The above also suggests that the study of the old—just like that of children and other groups—should be integrated within broader studies of society, and in this case within what is commonly referred to as household archaeology (e.g. Hardin Reference Hardin2010; Müller Reference Müller2015; Parker & Foster Reference Parker and Foster2012; Steadman Reference Steadman2015). Finally, I hope that this paper enlarged the opening created by the previous studies in order to shed light on this neglected sector and that it will encourage additional studies to pursue the issue further.

Acknowledgements

The research that resulted in this article was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation (#284/11; ‘The Birth, Life and Death of a Four-Room House at Tel ʿEton’). I would also like to thank the Tel ʿEton Expedition staff for their help in the study of the finds and the analysis of the material, and the anonymous reviewers and CAJ editors for their comments. The responsibility for the ideas expressed in the article and for any mistake or error is, of course, mine alone.