Dear Editor,

We read with interest the study by Qing et al. (Reference Qing, Ji and Yuan1), titled “Global, regional and national burdens of nutritional deficiencies, from 1990 to 2019”, published in The British Journal of Nutrition. The study provides insights into the global, regional and national burden of nutritional deficiencies over the past 30 years. However, we believe that this study lacks sufficient exploration of children as a unique population, failing to provide an in-depth analysis of their distinctive burden trends and global distribution. Malnutrition during childhood, a critical period for human development, can lead to wasting, underweight, and stunted growth, and may also increase the risk of chronic diseases later in life(Reference Belayneh, Loha and Lindtjorn2). In addition, the United Nations General Assembly’s Sustainable Development Goals, established in 2015, aim to eliminate all forms of malnutrition by 2030(3). These goals also seek to meet international targets related to stunting and wasting in children under five years of age by 2025. Given that the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study has been updated to its 2021 edition, it is essential to examine the most current burden of childhood nutritional deficiencies and their unequal distribution.

Data in this study were obtained from the GBD 2021 results, which is the largest and most recent comparative assessment of the burdens of 371 diseases and injuries at the global, regional, and national levels(Reference Ferrari, Santomauro and Aali4). We extracted data on the prevalence and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) of four common childhood (0–14 years) nutritional deficiencies (including protein-energy malnutrition, iodine deficiency, vitamin A deficiency, dietary iron deficiency) from the GBD 2021 study, covering 204 countries and regions. The distribution inequality of the total burden of childhood nutritional deficiencies across countries was measured by the slope index of inequality and the health inequality concentration index(Reference Hosseinpoor, Bergen and Schlotheuber5).

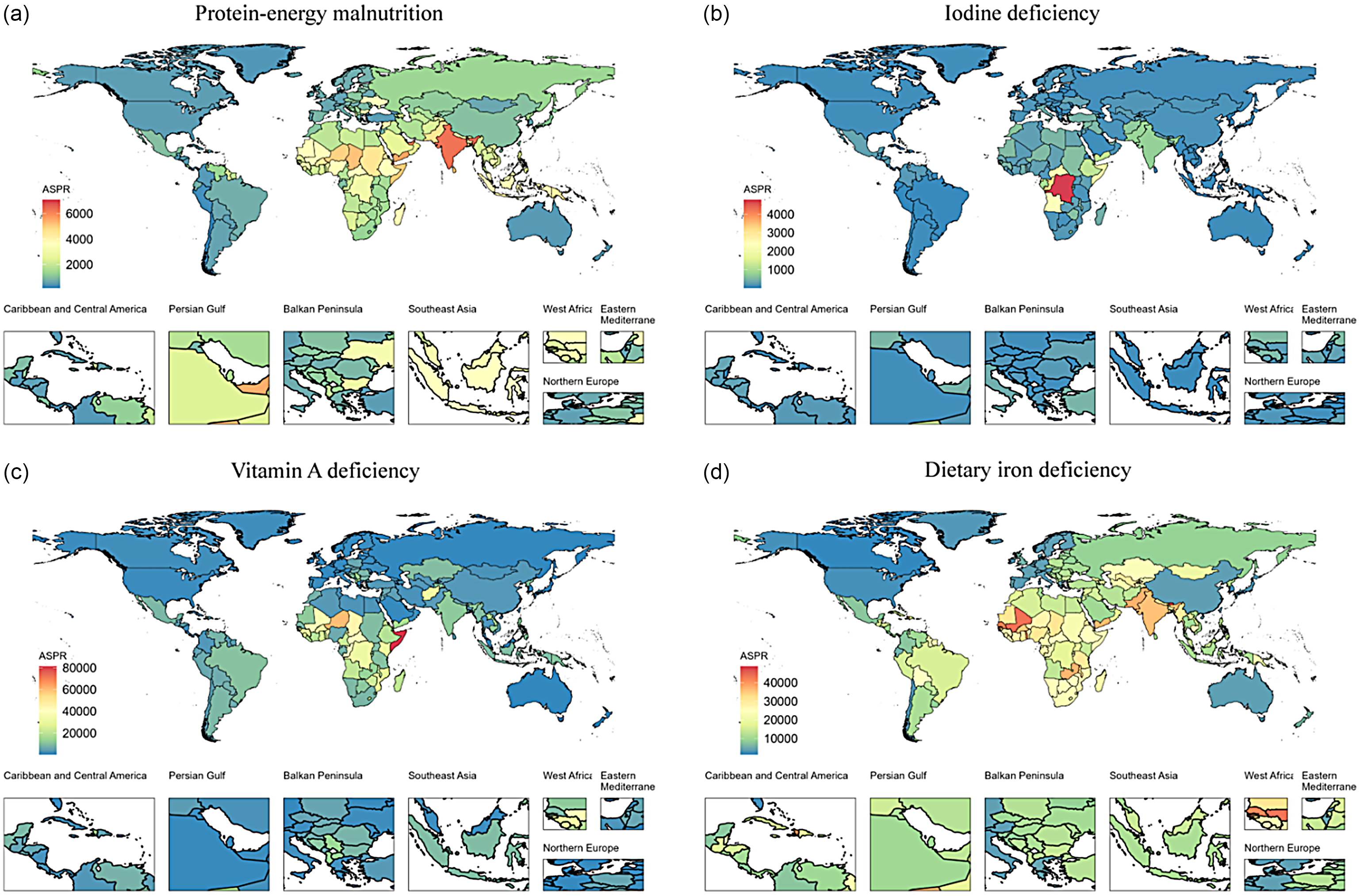

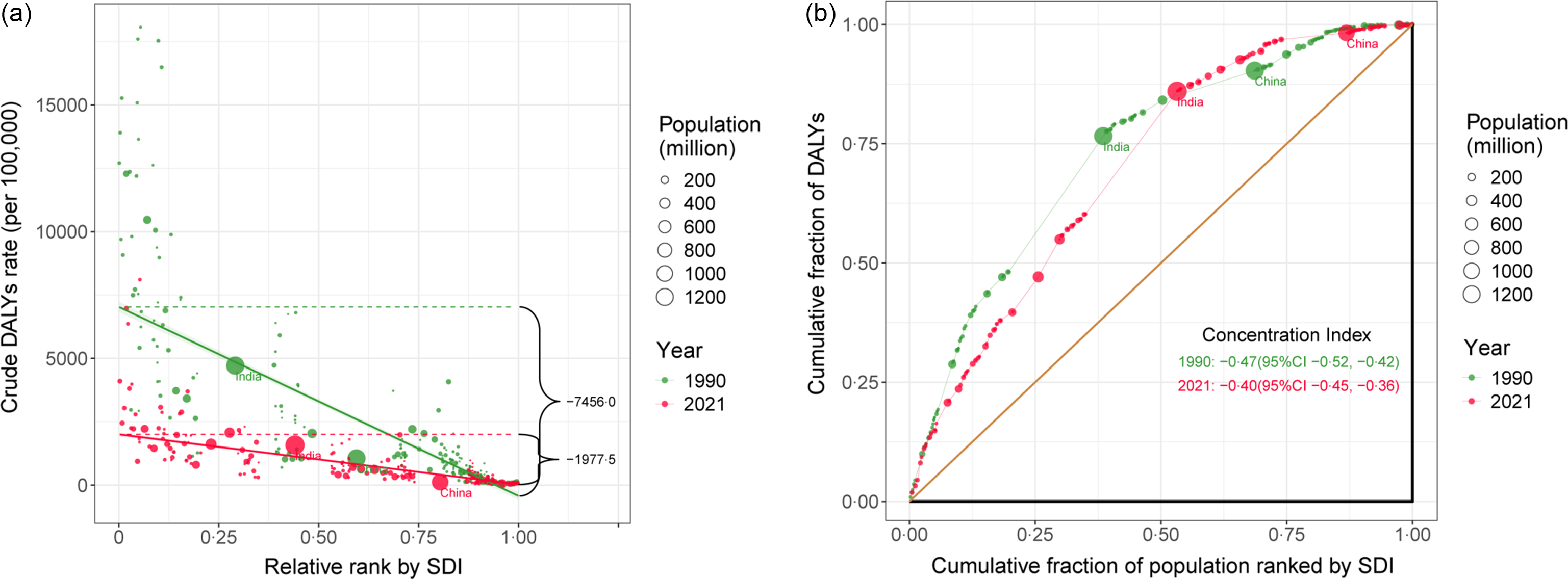

In 2021, children in South Asia exhibited the highest age-standardised prevalence rate (ASPR) of nutritional deficiencies caused by protein-energy malnutrition and dietary iron deficiency, while children in Central Sub-Saharan Africa experienced the highest ASPR due to iodine deficiency and vitamin A deficiency (Figure 1). Among the 204 countries globally, the highest ASPR of nutritional deficiencies in children due to protein-energy malnutrition, iodine deficiency, vitamin A deficiency, and dietary iron deficiency were observed in South Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, and Bhutan, respectively (Figure 1). Additionally, the cross-national inequality analysis observed both absolute and relative inequalities in the total burden of childhood malnutrition associated with the sociodemographic index (SDI), with countries having lower SDI shouldering a disproportionate burden. Over time, these inequalities have significantly diminished. As indicated by the inequality slope index, the gap in DALYs between countries with the highest and lowest SDI decreased from −7456·0 (95 % confidence interval (CI), −7870·1, −7041·8) in 1990 to −1977·5 (95 % CI, −2120·8, −1834·1) in 2021 (Figure 2(a)). Moreover, the concentration index in 1990 was −0·47 (95 % CI, −0·52, −0·42), compared to −0·40 (95 % CI, −0·45, −0·36) in 2021 (Figure 2(b)), indicating that the burden remains disproportionately concentrated in poorer countries.

Figure 1. ASPR of four common nutritional deficiencies in childhood in different countries and regions in 2021. (a) protein-energy malnutrition; (b) iodine deficiency; (c) vitamin A deficiency; (d) dietary iron deficiency. ASPR, age-standardised prevalence rate.

Figure 2. Health inequality slope index (a) and concentration index (b) for DALYs of four common nutritional deficiencies in childhood across 204 counties and territories, 1990 and 2021. ASPR, age-standardised prevalence rate; DALYs, disability-adjusted life years; SDI, sociodemographic index.

The negative inequality slope index indicates that as the SDI ranking improves, the burden of childhood malnutrition decreases, further highlighting that the burden is primarily concentrated in poorer countries. The decline in the absolute values of these two indicators suggests that from 1990 to 2021, the inequality in disease burden has reduced, marking a narrowing gap between high-income and low-income countries. While this outcome is encouraging, the widespread severity of the global burden of childhood malnutrition remains a significant concern. Therefore, to reduce health inequalities, greater attention must be paid to children’s nutritional health, improving dietary quality, and implementing effective measures such as strengthening preschool education and ensuring early and proactive treatment.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the excellent works by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2021 collaborators.

No fund support

K. C.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Y. S.: Writing – review & editing. Y. S. is the guarantors for the manuscript.

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Data sources and code used in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 are available on the internet (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/). The data presented is unpublished elsewhere and are not duplicated.