1.1 Introduction

Since the 9–11 attacks in 2001 and the beginning of the Arab uprisings more than a decade ago, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has witnessed interstate and civil wars, revolutions, coup d’états, rebellions, failing states, and unprecedented humanitarian crises. Naturally, the politics of the region is of great importance to academics, researchers, and the public. Yet, studies of the region and its transformation usually focus on traditional issues, such as the effects of cultural factors like religion or ethnicity, and rarely utilize advancements in social sciences. This book fills both gaps by focusing on MENA leadership as an explanatory factor in shaping the politics of the region by using cutting-edge theoretical and methodological advancements in the foreign policy analysis (FPA) field.

This book makes an important contribution for many reasons. It answers multiple relevant questions: Are MENA leaders’ views on politics utterly conflictual or do their beliefs reflect a friendly world? Are MENA leaders more likely to use cooperative instruments or coercive measures in foreign policy? Do MENA leaders believe they are the masters of history or do they think historical control lies with the political competitors? Are Middle Eastern leaders rational actors, or are they irrational, as portrayed in some popular media? What type of leadership styles can be associated with MENA leaders, and what are the strategies associated with these leadership types? Are MENA leaders significantly different from the average for world leaders in foreign policy beliefs and strategies? What are some possible strategies to negotiate with them? Are traditional great power strategies of “deterrence,” “compellence,” “coercive diplomacy,” and “brinkmanship” toward certain MENA leaders useful, or are they counterproductive in achieving diplomatic results? What are the optimal strategies to negotiate with MENA leaders? What are the best strategies for MENA leaders to deal with the United States, Russia, and other great powers in the region? Are there significant differences in foreign policy beliefs and strategies of MENA leaders coming from distinct ideologies such as Sunni political Islam, Shia political Islam, secularism, or Marxism? Finally, how useful is it to answer these questions in terms of solving real-life political issues in the region, such as the Syrian civil war, Iran’s nuclear program, the Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict, and the various insurgencies in the region?

Our results indicate a balanced portrayal of MENA leaders. Although, on average, MENA leaders analyzed in this study see a more conflictual political world and are less inclined toward cooperative strategies than norming group leaders, we also observe a set of rational actors who can be negotiated with and who reach diplomatic outcomes. Our results also present variance among leaders who represent different ideologies and backgrounds. While secular nationalist and Sunni Islamist leaders have shown more positive political beliefs and an inclination toward cooperative strategies, Shia revolutionaries’ and armed nonstate organization leaders’ beliefs appear to be less cooperative.

1.2 Historical Background

Almost four hundred years of relative stability in MENA was punctuated by the onset of the First World War in 1914. Following the demise of the Ottoman Empire, MENA was divided among the Allied powers and tribal rulers. The region has also witnessed periods of colonization, independence movements, and upheavals associated with finding the right social order to fit the local populations in the post–Second World War era. Regarding the latter struggle, secular nationalist movements of Turkey, Iran, and Egypt modernized their societies to some extent. With the rise of unmet social demands, the Cold War competition, regional political turmoil, and economic problems, many MENA countries have encountered the rise of political Islam as a strong challenger to mostly autocratic secularist regimes. These Islamist movements came to power through a revolution in Iran in 1979 and via elections in Turkey and Algeria during the 1990s, while they were harshly suppressed in other countries, such as Egypt. The democratic and economic demands of large populations exploded during the Arab uprisings. Since December 2010, a series of uprisings, revolutions, coups, and civil wars have shaken up the region beyond expectations.

Politics and foreign policy in the MENA cannot be fully understood without factoring individual leaders into the analysis as the region has been susceptible to powerful and charismatic political leaders. The explanations for the MENA region’s receptiveness to leader-oriented politics include the prevalence of dynastic monarchies and presidents for life as predominant regimes and failed/illiberal democratic experiments in the bulk of the region, as well as the recurrent uprisings, wars, and revolutions throughout the broader region (Reference DekmejianDekmejian, 1975; Reference ZakariaZakaria, 1997; Reference Hinnebusch, Brummer and HudsonHinnebusch, 2015). The MENA region has been a fertile political ground, producing many influential and transformative leaders with diverse personal and ideological credentials. Such high-profile leaders include the founding fathers of secular nationalism in the MENA – Kemal Atatürk and Gamal Abdel Nasser; late proponents of the Ba’ath Party – Hafez al-Assad and Saddam Hussein; the new generation of hereditary monarchs – Mohammed bin Zayed and Mohammed bin Salman; Islamic militant top dogs – Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and Osama bin Laden; and modern Sunni and Shia political Islamist leaders – for example, Ali Khamenei and the late Yusuf al-Qaradawi. Because there is no dearth of strong-willed political personalities at the helm of MENA politics and foreign policy, the MENA region offers extensive, albeit hitherto underutilized, data and a plethora of theoretical and methodological resources for the students of leadership studies and FPA.

This book analyzes different foreign policy approaches in today’s MENA by focusing on representative executive decision-makers affiliated with four main ideological categories in the region: Sunni political Islamists, Shia political Islamists, secular nationalists, and armed nonstate actors (ANSAs) leadership. In this context, we will depict foreign policy beliefs and strategies of Muslim Brotherhood leaders – Mohamed Morsi, Rashid Ghannouchi, and Khaled Mashaal; Shia leaders in Iran and Iraq – Ali Khamenei, Hassan Rouhani, Ali al-Sistani, and Nuri al-Maliki; secular leaders, such as Bashar al-Assad, Saad al-Hariri, and Benjamin Netanyahu; and ANSA leaders, including Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi of ISIS, Abdullah Öcalan of PKK, Salih Muslim of PYD, and Hassan Nasrallah of Hezbollah.

We situate our work within the operational code analysis (OCA) framework (Reference LeitesLeites, 1951; Reference GeorgeGeorge, 1969; Reference WalkerWalker, 1990; Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker et al., 1998; Reference Walker, Schafer and Young1999) because it is a unique leadership assessment tool that can successfully synthesize both instrumental (strategic) and philosophical (theoretical) factors shaping foreign policy with a nuanced focus on agency. The operational code construct offers a viable tool to identify psychological and political sources of states’ foreign policy conceptions and behavior at the same time. By employing OCA to survey different strands of modern political leaderships in MENA, we present a theory-driven and data-based empirical analysis of the current foreign policymaking patterns in the region.

This research addresses multiple lacunas in the literature on non-Western political leaders and area studies concerning MENA. First, while the scholarly and media portrayals of the modern MENA are laden with discussions on the clashing sectarian (Sunni versus Shia) and political factions (secularism versus political Islam) and on the proliferation of ANSAs, there has been insufficient focus on the executive leadership dimension of such competing ideologies and their implications for MENA’s international relations. By engaging with ideologies and foreign policy beliefs via the operational code construct, we suggest a novel and nuanced viewpoint on the conflict-ridden MENA region from the vantage point of political psychology.

Second, although there is a large literature on MENA politics and foreign policy decision-making, most studies provide a descriptive analysis of the region based on historical anecdotes. As noted by Reference Hinnebusch, Brummer and HudsonHinnebusch (2015), there is a dearth of data-based and theory-driven systematic research on regional politics. Moreover, given the geographical boundedness of FPA as a North America–based scholarly discipline, there is a void in the leadership research program concerning the study of non-Western decision-makers. Third, the centrality of political personalities in MENA politics notwithstanding, there are only a few theoretical and empirically rich studies on MENA’s significant political leaders (see Reference Malici and BucknerMalici and Buckner, 2008; Reference Duelfer and DysonDuelfer and Dyson, 2011; Reference KesginKesgin, 2013; Reference Kesgin2020a; Reference Kesgin2020b; Reference ÖzdamarÖzdamar, 2017b; Reference Özdamar and CanbolatÖzdamar and Canbolat, 2018; Reference Brummer, Young and ÖzdamarBrummer et al., 2020; Reference CanbolatCanbolat, 2020a; Reference Canbolat2020b; Reference Canbolat, Schafer and Walker2021).

The case selection is informed by our readings and expertise about the region. These four leadership categories have dominated domestic politics and foreign policy in the region as they compete for supremacy and diffusion. Sunni political Islam has broadly gained strength across the MENA in the post–Cold War era. Following the Arab uprisings, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) of Sunni political Islam, generally viewed as the world’s largest and most influential Islamist organization, has shaped the wider landscape of MENA politics. Shia political Islam has reasserted itself in MENA politics, in tandem with the increasing Iranian influence in the region in the wake of the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979. The long-lasting secular nationalist movements in MENA produced secularist leaders in many countries, including Israel, Syria, Turkey, and Lebanon. The Arab uprisings have mostly targeted secularist autocratic regimes and empowered political Islamists in the region whose quest for executive power is still in the making. Lastly, MENA has been one of the few regions in the world where ANSAs can control and govern pockets of territories at the expense of the region’s nation-states. In the post–Arab uprisings era, the ANSAs have gained in strength and seized opportunities, which made them local and regional actors to be reckoned with, including the PYD in Syria, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and the PKK in the broader region.

Regarding our methodology, we profile select representative leaders of each ideology and their foreign policy beliefs by using automated content analysis procedures and by analyzing cases with process-tracing methods. The level of analysis in all operational code work is either individual or group. Our book utilizes an individual level of analysis. In line with the general operational code scholarship, the unit of analysis in our research is the individual public statements of the studied leaders. We employ the canonical Verbs in Context System (VICS) and use the Profiler Plus software to profile the MENA leaders epitomizing different political ideologies in the region (Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker et al., 1998). With regard to the data, we have marshaled the most extensive and systematic evidence on modern MENA leaders, which is the whole universe of available speech data on the studied leaders. In total, for 14 MENA leaders, we garnered around 550 public statements whose total word count exceeds 1.7 million words and around 100,000 codable verbs; the required minimum word count is 1,000 and the minimum number of codable verbs is 20 for each speech (Reference Schafer, Walker, Schafer and WalkerSchafer and Walker, 2006a: 44).

In this context, the book makes rich theoretical and empirical contributions as it tests the usefulness of operational code construct in foreign policymaking in the developing world. Beyond its theoretical promise, the book also focuses on a timely issue and strives to answer important questions about the region and world politics. To that end, we hope our book is appealing to policymakers, the think-tank sector, and general readers.

1.3 Operational Code Analysis and Leadership Studies

Foreign policy analysis is a subfield of international relations focusing on the decision-making and procedures of foreign policymaking as opposed to only outcomes. Psychological and cognitive characteristics of decision-makers have been a part of the decision-making research agenda. Many groundbreaking studies in this literature give psychological approaches a paramount place in their analyses (Reference LeitesLeites, 1951; Reference Snyder, Bruck and SapinSnyder et al., 1962; Reference Sprout and SproutSprout and Sprout, 1965; Reference JervisJervis, 1976; Reference KhongKhong, 1992). Building on these classics, numerous research programs focusing on different psychological factors have been formed in the FPA literature.Footnote 1

The origins of leadership studies literature date back to the nineteenth century and Thomas Carlyle’s “great man theory of leadership” (Carlyle 1888, as cited in Reference Rosati, Neack, Hey and HaneyRosati, 1995). The key contention of Carlyle’s theory is that world history can be explained and understood by the impact of “great men and/or heroes,” who have innate political skills and power, on historical developments and the political system. Therefore, Carlyle (1888: 2, as quoted in Reference Rosati, Neack, Hey and HaneyRosati, 1995) argues that “the history of the world is but the biography of great men.” The studies that employ the great man theory use biographies of leaders such as Napoleon of France and Churchill of Britain, but these studies are limited in their scientific basis and methodological rigor (Reference SegalSegal, 2000). This approach has been criticized as anecdotal and methodologically flawed. Studies focusing on Middle East leadership from the vantage point of sociology appeared during the second half of the last century. A few important studies include Ottoman Reform and the Politics of Notables (Reference Hourani, Hourani, Khoury and WilsonHourani, 1968), Dimensions of Elite Change in The Middle East (Reference WeinbaumWeinbaum, 1979), and The “Politics of Notables” Forty Years After (Reference GelvinGelvin, 2006).

In the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, there was a growing need for actor-specific analyses since both rational actor models and other mainstream international relations (IR) theories failed to anticipate or to account for the demise of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War (Reference Walker, Schafer, Schafer and WalkerWalker and Schafer, 2006). In this context, OCA has gained prominence in conjunction with other FPA-style studies. Operational code analysis is a classical approach to foreign policy within the cognitive/psychological paradigm that focuses narrowly on a leader’s political belief system or more broadly on a set of beliefs embedded in the character of a leader that emanate from the cultural matrix of society (Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker et al., 1998; Reference WalkerWalker, 2000; Reference Walker, Schafer, Schafer and WalkerWalker and Schafer, 2006). Accordingly, the beliefs of political leaders are used as causal mechanisms to account for a set of foreign policy decisions (Reference LeitesLeites, 1951; Reference GeorgeGeorge, 1969; Reference WalkerWalker, 1983; Reference Walker, Schafer, Schafer and WalkerWalker and Schafer, 2006).

The core argument of the operational code research program is that key individuals and their political beliefs are significant in explaining foreign policies of states which were not addressed effectively by many IR theories, and also some decision-making approaches to foreign policy. Rooted in the cognitive/psychological paradigm, the operational code approach argues that the belief system of leaders may act as causal mechanisms in explaining why they prefer a certain foreign policy decision over a set of other alternative policies. The rational choice paradigm, on the other hand, ignores differences in leaders’ beliefs and perceptions and also their impacts on foreign policy decisions, which were the reasons for its failure to foresee and explicate the end of the Cold War and many other important historical developments.

The operational code research program was originally developed by Nathan Reference LeitesLeites (1951; Reference Leites1953) during the early Cold War years to analyze the decision-making style of the Soviet Politburo. Reference LeitesLeites (1951; Reference Leites1953) argued that the Soviet Union’s precarious relations and unusual bargaining behavior with the United States leadership can be explained by analyzing the belief systems of Lenin and Stalin. Reference WalkerWalker (1983) concurred with Leites’ argument that Lenin and Stalin had a profound impact on the mindsets of other Soviet leaders and thus shaped the modus operandi of the Soviet Politburo, especially in the foreign policymaking domain. These two seminal works established the foundation of the operational code framework, and they have been both exploratory and descriptive in their analysis of Soviet Politburo decision-making.

Although Leites’ work has received some attention in the literature, during the 1950s and 1960s IR scholars preferred to focus on studies explaining IR from a structural perspective. Renewed attention to OCA came about with Reference GeorgeGeorge’s (1969) article, which categorized many questions in earlier operational code construct into a set of questions regarding philosophical and instrumental beliefs that make sense of perceptions of the political universe, the role of the leader in that universe, and strategies aiming at the efficacy of various instrumental means.

Reference GeorgeGeorge (1969) elaborated on Leites’ study by developing two main groups of political beliefs which are the answers to the ten questions posed in his groundbreaking study. Firstly, the five philosophical beliefs enable researchers to highlight the leader’s perceptions of the political universe and the role of Other with whom the leader confronts in this universe. The second set contains five instrumental beliefs which show the image of the Self and provide a mapping of the means for the ends following the most optimal strategy and tactics for the achievement of foreign policy goals (Reference GeorgeGeorge, 1969; Reference WalkerWalker, 1990). These two sets of beliefs are used together to account for decision-makers’ tendencies within and attitudes toward foreign policymaking (Reference Schafer, Walker, Schafer and WalkerSchafer and Walker, 2006a). Put differently, Reference GeorgeGeorge (1969: 200) argues that these ten fundamental questions “would capture a leader’s fundamental orientation towards the problem of leadership and action.” The ten questions of the operational code research program are listed here (Reference GeorgeGeorge, 1969: 200):

The Philosophical Beliefs in an Operational Code are:

P-1. What is the essential nature of political life? Is the political universe essentially one of harmony or conflict? What is the fundamental character of one’s political opponents?

P-2. What are the prospects for the eventual realization of one’s fundamental values and aspirations? Can one be optimistic, or must one be pessimistic on this score, and in what respects the one and/or the other?

P-3. Is the political future predictable? In what sense and to what extent?

P-4. How much control or mastery do Self and Other have over historical development? What is Self and Other’s role in moving and shaping history in the desired direction?

P-5. What is the role of chance in human affairs and in historical development?

The Instrumental Beliefs in an Operational Code are:

I-1. What is the best approach for selecting goals or objectives for political action?

I-2. How are the goals of action pursued most effectively?

I-3. How are the risks of political action calculated, controlled, and accepted?

I-4. What is the best timing of action to advance one’s interests?

I-5. What is the utility and role of different means for advancing one’s interests?

Reference GeorgeGeorge (1969: 202) further contributed to the operational code approach by reconceptualizing the first two philosophical beliefs and the first instrumental belief as master beliefs that functioned as a primary constraint on the belief systems and perceptions of leaders. Following Reference GeorgeGeorge’s (1969) seminal work, a good number of qualitative operational code analyses were brought into the literature that employed his theoretical template and verified the causal mechanism offered by early scholars of the program (Reference Johnson and HermannJohnson, 1977; Reference WalkerWalker, 1977; Reference StarrStarr, 1984).

In particular, Reference WalkerWalker’s (1977) study on Henry Kissinger’s leadership style was significant because he systematically analyzed the relationship between political beliefs and foreign policy behavior by exploring the interface between Kissinger’s political beliefs and his bargaining behavior during the Vietnam impasse. This work is seen as “the most consistent attempt to connect the operational code to the policy behavior of a leader” (Reference Young and SchaferYoung and Schafer, 1998: 73). Loch Reference Johnson and HermannJohnson (1977) also contributed to the theoretical arsenal of operational code construct which laid the foundations for the development of the quantitative approach within the research program. Reference Johnson and HermannJohnson’s (1977) study of Senator Frank Church’s belief system found that “the beliefs in operational code were arranged along a continuum making the answers to philosophical and instrumental questions applicable to interval-level scales, thus facilitating comparison among political actors” (Reference Young and SchaferYoung and Schafer, 1998: 70).

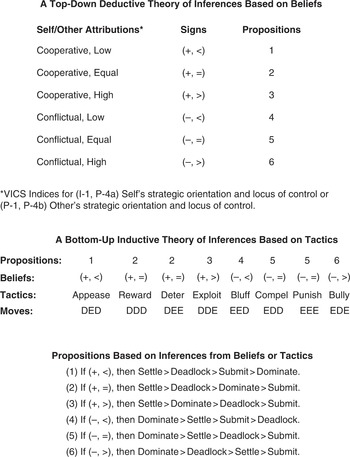

Building on Reference GeorgeGeorge’s (1969) framework, Reference HolstiHolsti (1977) constructed a leadership typology based on leaders’ operational codes by answering George’s ten questions about philosophical and instrumental beliefs. He established six types of op-codes (A, B, C, D, E, F) which were later reduced to four groups (A, B, C, DEF) by Reference WalkerWalker (1983; Reference Walker1990). Holsti’s typology is based on the nature (temporary or permanent) and the source (individual/society/international system) of conflict in the political world, derived from the master beliefs which are answers to the P-1, I-1, and P-4 questions. Figure 1.1 represents the revised version of Reference HolstiHolsti’s (1977) typology in detail.

Figure 1.1 Contents of Holsti’s revised operational code typology.

In the late 1990s, the turning point for the operational code research program came with the paradigmatic work of Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker et al. (1998), which paved the way for an excessive body of literature on leadership analysis to flourish. First, Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker et al. (1998), which focused on the change in Jimmy Carter’s political beliefs in the late 1970s, established an at-a-distance and quantitative operational code research agenda. This novel research agenda allowed for measurements such as the subject’s view of conflict propensities in the world and the utility of conflict as a means of policy by the subject himself (Reference SchaferSchafer, 2000).

To that end, Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker, Schafer, and Young (1998) developed The Verbs in Context System (VICS), which conducts an automated content analysis to draw inferences about a decision-maker’s operational code establishment from publicly available sources that include speeches, interviews, and other public statements made by the leaders. The VICS, as a content analysis technique, refers to a set of methods that are used to retrieve the patterns of beliefs from a leader’s public statements and then draw inferences about public behavior which are considered to be consistent with these beliefs (Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker et al., 1998; Reference Walker, Schafer, Schafer and WalkerWalker and Schafer, 2006). To locate leaders’ images of the Self and Other in one of the four quadrants of Holsti’s typology, the VICS indices of the master beliefs (P-1, I-1, and P-4 scores) must be mapped on the horizontal (P-4) and vertical (P-1/I-1) axes in Figure 1.1. Based on this leadership typology and associated strategies, a researcher can make forecasts about strategic preferences for the goals of settle, submit, dominate, and deadlock (Reference Walker, Schafer, Schafer and WalkerWalker and Schafer, 2006).

Building on earlier work by Reference HolstiHolsti (1977), Walker and his colleagues (Reference Marfleet, Walker, Schafer and WalkerMarfleet and Walker, 2006; Reference Walker, Schafer, Schafer and WalkerWalker and Schafer, 2006: 21) formulated the theory of inferences about preferences (TIP), which is depicted in Figure 1.2. This theory specifies “whether a leader is generally inclined to use strategies involving cooperation or conflict (I-1) and whether that individual believes that Self is in control of historical development (P-4)” (Reference Marfleet, Walker, Schafer and WalkerMarfleet and Walker, 2006: 56). Indexed to TIP, as noted by Reference Crichlow, Schafer and WalkerCrichlow (2006: 78), I-1 and P-4 master beliefs “point to the types of strategies leaders may engage in that differ from the norm of reciprocity. For example, leaders who believe in cooperative strategies and also believe that they have little control in shaping the world around them are more likely to engage in appeasement tactics than other leaders.” Explicating different functions of TIP, Reference Marfleet, Walker, Schafer and WalkerMarfleet and Walker (2006: 56) also maintained that “moves and tactics may be guided by the strategies for the subjective games embedded in a leader’s belief system, which are defined by different combinations of ‘master beliefs’ and a theory of inferences about strategic preferences.”

Figure 1.2 A theory of inferences about preferences (TIP) from beliefs or tactics.

This renewed research program has led to a growing body of literature on operational code analyses of leaders and also novel research areas which include studies on change in political beliefs and its impacts on policy behavior, group decision-making (e.g., the relationship between leaders and advisors), political beliefs of rogue and terrorist leaders, operational code and democratic peace theory, operational code and game theoretical models, and operational code and international policy economy (Reference Schafer and CrichlowSchafer and Crichlow, 2000; Reference CrichlowCrichlow, 2002; Reference FengFeng, 2005; Reference Malici and MaliciMalici and Malici, 2005a; Reference Malici and Malici2005b; Reference Drury, Schafer and WalkerDrury, 2006; Reference MaliciMalici, 2006a; Reference Schafer and WalkerSchafer and Walker, 2006c; Reference Malici and BucknerMalici and Buckner, 2008; Reference RenshonRenshon, 2008, Reference Renshon2009; Reference He and FengHe and Feng, 2013; Reference Özdamar and CeydilekÖzdamar and Ceydilek, 2020; Reference Canbolat, Schafer and WalkerCanbolat, 2021; Reference Schafer and WalkerSchafer and Walker, 2021).

While many FPA-style studies focus on individual decision-makers, including mainstream, rogue, terrorist, and emerging leaderships (e.g., populist, nativist, and radical/far-right leaders), there has been a stream of research on comparative political culture and their implications on the operational codes of leaders operating in different regime types. For instance, Reference Schafer and WalkerSchafer and Walker (2006b) bring the operational code construct to bear on the “democratic peace theory” debates and find that both Tony Blair and Bill Clinton exhibited exceedingly friendly propensities in their foreign policy conceptualization toward democracies as they viewed democratic countries as more peaceable compared to autocratic regimes.

In a similar vein, Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker and his colleagues (1998) show that Jimmy Carter’s operational codes are bifurcated as the authors compared Carter’s generic political belief system to his specific beliefs concerning the Soviet Union during his time in the Oval Office. While there were educated guesses that Putin’s political beliefs, as a new actor in Russian and world politics, would be largely analogous to those of the mainstream world leaders (Reference DysonDyson, 2001), Reference Dyson and ParentDyson and Parent (2018) find that Putin’s operational codes about the NATO/Western countries were at variance with his general political beliefs. These studies also demonstrate that the “political universe” can be divided into regional subgroups – for example, the MENA, and/or a group of states such as the NATO countries.

In conclusion, with the introduction of VICS and Profiler Plus software, Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker and his coauthors’ (1998) success in standardizing the English coding scheme for leadership analysis led the OCA research program into an expansionary phase. This study by Reference Walker, Mark and YoungWalker et al. (1998) also marked a methodological shift from hand-coding to computer-assisted coding as the default research technique of the at-a-distance leadership assessment programs. Profiler Plus enables leadership analysis scholars to access systematic and swift text coding. Thanks to such theoretical and methodological developments, there has been an exponential increase in the number of studies within the operational code research program. The verb-focused scheme of VICS proved instrumental in a plethora of operational code studies analyzing individual leaders and/or elite groups from diverse regions across the world.

1.4 Operational Code Analysis Outside of North America

Although Nathan Reference LeitesLeites (1951; Reference Leites1953) originally developed an operational code construct to analyze a non-Western political group (the Soviet Politburo), the contemporary operational code research agenda mostly focuses on Western-based leaders and political groups, for various reasons. Therefore, it has been relatively difficult to apply the operational code approach to examine national leaders and decision-making groups which operate in non-Western political systems that have an impact on the dynamics of foreign policy behaviors of states in different parts of the world such as the MENA region. Admittedly, Western-originated FPA theories have mainly suffered from “boundedness” and “inapplicability” problems when used for non-North American cases, and the operational code approach to foreign policy also could not break this “universal inapplicability” mold. As a result, there are very few FPA-style studies that zero in on non-Western cases and political Islam as a distinct political ideology with particular foreign policy behaviors (Reference CrichlowCrichlow, 1998; Reference MaliciMalici, 2007; Reference Malici and BucknerMalici and Buckner, 2008; Reference PicucciPicucci, 2008; Reference WalkerWalker, 2011; Reference JacquierJacquier, 2012; Reference ÖzdamarÖzdamar, 2017b; Reference Özdamar and CanbolatÖzdamar and Canbolat, 2018; Reference Brummer, Young and ÖzdamarBrummer et al., 2020).

Studying the impact of Islam and religious political groups and/or leaders (e.g., the Mullahs) on foreign policy preferences began in Western academia in the aftermath of the Iranian revolution of 1979. The early studies were not as developed in terms of their methodologies and theoretical approaches as other social sciences that failed to examine the impact of political Islam on foreign policy (Reference DawishaDawisha, 1985; Reference LewisLewis, 1991). Since then, the sources of foreign policy in the Islamic world have been studied by both Muslim scholars with an Islamic perspective on the religion–foreign policy nexus and also by other scholars who applied Western-oriented geopolitical theories to expound MENA’s international relations (Reference AbuSulaymanAbuSulayman, 1987; Reference LewisLewis, 1995; Reference Fuller and LesserFuller and Lesser, 1995). Although there has been an upsurge of scholarly interest in Islamic movements and leaders in the wake of cataclysmic events such as the 9/11 attacks and the US-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the literature on Islamic leaders’ influences on the foreign policy choices of MENA countries can be defined as, at best, inchoate. This book aims to address this consequential gap in the FPA literature.

The extant but limited literature on operational code analyses of MENA political leaders can be traced back to Reference CrichlowCrichlow’s (1998) study comparatively measuring the operational codes of Israeli leaders Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres that shaped not only Israeli foreign policy but also the Arab–Israeli peace process and hence Middle East politics from the 1970s to 1990s. Israeli political leaders were among the first subjects of the data-based and systematic profiling efforts focusing on the application of the operational code approach to MENA leadership cases. In his study, Reference CrichlowCrichlow (1998: 623) observed that “both leaders’ conception of their political environment changed over time, from conflictual in the 1970s to neutral in the 1990s but unlike Rabin, operational code of Peres underwent acute fluctuations, in response to the perceived different situational context.” Reference O’ReillyO’Reilly (2007) focused on “rogue state leadership” in the world and used operational code analysis to explain the modus operandi of rogue states by analyzing the belief systems of the leaders of those states. The author studied the political leadership of Muammar Kaddafi as a case study to shed some light on a rogue state of mind. Reference O’ReillyO’Reilly (2007: 24–25) argues that in examining the operational code of Kaddafi, “a distinct world view emerges dissimilar to that of the average world leader.”

Similarly, there were a few more FPA-style studies that focused on “rogue leaders” and their foreign policy behaviors, especially in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Reference MaliciMalici (2007) and Reference Malici and BucknerMalici and Buckner (2008) aimed at theorizing on the foreign policy preferences of such leaders by establishing a link between the levels of their frustration with the perceptions of hostile American foreign policy toward their regimes and, in return, their aggressive foreign policy behavior toward Western powers, especially the United States. By examining the psychology of leaders such as Kim Jong-Il of North Korea, he suggested a “realistic empathy” toward “rogue” leaders, and the mutual advantages of pursuing engagement strategies rather than containment (Reference MaliciMalici, 2007). Building on this theoretical template, Reference Malici and BucknerMalici and Buckner (2008) elaborated on the psychological profiling of rogue leaders and broadened the research agenda on rogue leaders by examining the operational codes of two MENA leaders: Iran’s Ahmadinejad and Syria’s al-Assad. Their study provides evidence against the conventional wisdom that Iran and Syria are antagonistic states headed by bellicose leaders and that Ahmadinejad’s and al-Assad’s uncompromising policy behaviors stem from their perceptions of “US actions towards their countries as highly hostile that threaten the survival of the regimes in Tehran and Damascus” (Reference Malici and BucknerMalici and Buckner, 2008: 798).

In parallel with the study of “rogue” leaders, there were a few studies in the late 2000s that utilized the operational approach in the study of terrorism and terrorist organizations mainly operating in the MENA region (Reference PicucciPicucci, 2008; Reference JugazZugaj, 2010; Reference JacquierJacquier, 2012). These authors had the common starting point that “beliefs are central features of terrorist decision-making and therefore to understanding their behaviors … Understanding the beliefs of terrorist organizations is also therefore a crucial element in informing counter-terrorism efforts” (Reference PicucciPicucci, 2008: 117). However, contrary to the conventional operational code approach, these studies aimed to focus on political actors (both individual leaders and groups) who do not take part in a state’s leadership structure but continue to have an impact on MENA’s international relations (Reference JacquierJacquier, 2012).

The latest subject matters of operational code studies on terrorism have been the well-known terrorist organization al-Qaeda (Reference PicucciPicucci, 2008; Zugaj, 2010; Reference WalkerWalker, 2011), Palestinian Islamist organization Hamas (Reference PicucciPicucci, 2008), and the leaders of al-Qaeda: Osama bin Laden and his successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri (Reference WalkerWalker, 2011; Reference JacquierJacquier, 2012). Reference WalkerWalker’s (2011) study highlights significant differences between the operational codes of bin Laden and al-Zawahiri, which provides significant insights into al-Qaeda’s terrorist strategies to achieve their political aims and the capabilities of the global jihadist movement. However, there is a growing critical perspective on these leadership studies using “at a great distance” theoretical approaches and methods that, albeit rigorous, are destined to be bounded in scope and substance (Reference JacquierJacquier, 2012; Reference ÖzdamarÖzdamar, 2017b).

More recently, there has been a resurgent interest in the MENA leaders and regional politics owing to the popular uprisings in the Arab world since 2010, which have paved the way for the reconfiguration of political power centers and made Islamist movements and leaders indispensable actors in understanding the changing character of MENA’s international relations. In the aftermath of the Cold War, Islamic movements resurged and manifested themselves in terrorist activities and resistance organizations against expansionist states (Reference PicucciPicucci, 2008; Reference ÖzdamarÖzdamar, 2011), and also in democratic systems such as in Tunisia with the Ennahda Movement (Reference Özdamar and CanbolatÖzdamar and Canbolat, 2018).

In his study, Reference ÖzdamarÖzdamar (2017) analyzes the operational codes of three Islamist leaders of MENA in a comparative manner: Necmettin Erbakan of Turkey, Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran, and Muammar Kaddafi of Libya. The author asserts that, although these MENA leaders have distinct personal characteristics and political experiences, their approaches to foreign affairs show notable uniformity. Reference ÖzdamarÖzdamar (2011: 13) underlines that while “all three leaders showed very negative and high scores of P1 and very high scores of P4b (with low P4a scores) that can be explained by their nations’ early experiences of Western colonialism and imperialism, these leaders’ foreign policy strategies showed a mixed picture. The most general pattern is the Islamists see themselves as cooperative if opportunities arise.”

FPA-style studies focusing on MENA leaders and foreign policymaking are still in the minority compared to mainstream approaches in the IR discipline (see Reference Malici and BucknerMalici and Buckner, 2008; Reference KesginKesgin, 2013; Reference Çuhadar, Kaarbo, Kesgin and Ozkececi-TanerÇuhadar et al., 2017; Reference ÖzdamarÖzdamar, 2017b; Reference Özdamar and CanbolatÖzdamar and Canbolat, 2018; Reference Canbolat, Schafer and WalkerCanbolat, 2021; Reference Canbolat, Gansen and JamesCanbolat et al., 2021). Reference Hinnebusch, Brummer and HudsonHinnebusch (2015: 84) argues that the rational choice model (RCM) is the prevailing paradigm in leadership analysis and decision-making studies, which dwarfs psychology- and cognition-based treatments of MENA politics and foreign policy. FPA scholarship beyond the Anglosphere has also suffered from data quantity and quality issues because at-a-distance leadership assessment tools have, by and large, remained limited to English-language text corpora only. Such shortcomings largely hampered FPA-style research in the non-English speaking domains until recently (see Reference Brummer, Young and ÖzdamarBrummer et al., 2020). With the introduction of operational code schemes in Turkish (Reference Özdamar, Canbolat and YoungÖzdamar et al., 2020; Reference CanbolatCanbolat 2020b), Arabic (Reference CanbolatCanbolat, 2020a), and Persian (Reference MehvarMehvar, 2020), the bounded nature of opcode theory and application is remedied to some extent.

To sum up, the operational code construct has shown some success in its application to various case studies concerning MENA leadership and foreign policymaking over the years, which has enabled scholars to systematically measure the political belief systems of key decision-makers operating in the region.

1.5 Overview of the Book

This chapter has introduced the background and current developments in the MENA region in the past decade. Particular emphasis is given to understanding the MENA’s international relations and its current transformation as an ongoing clash of competing blocs of Sunni and Shia political Islamist, secularist, and ANSAs leaderships. The chapter succinctly identifies the four prominent political categories and their implications for foreign policymaking in the region. We then introduced operational code analysis and the methodological approach of the book. Classical examples of the operational code construct literature since the early 1950s, as well as the most recent works of the last decade, are discussed. Contributions of the operational code approach and where exactly this study fits in the literature are at the heart of this chapter.

Chapter 2 first provides a brief description of Sunni political Islam as an ideology, with a focus on the historical provenances of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and its expansion in the broader MENA region. Second, we present succinct biographical accounts (psycho-biographies) of individual Muslim Brotherhood leaders: Mohamed Morsi, Rashid Ghannouchi, and Khaled Mashal. We then discuss the OCA results of the leaders respectively: (1) among each other (in-group); (2) within the average world leadership norming group (systemic/world out-group). Next, we address the following key questions: What kind of generic foreign policy behavior and strategies we should expect from the Sunni political Islamist leaders? What do these results and strategies mean for current MENA politics and the IR discipline? We conclude that, despite the conventional portrayal of MB leadership, these leaders use negotiation and cooperation to settle their differences in foreign affairs, and the best way to approach them is to engage in a Rousseauvian assurance game that emphasizes international social cooperation. At-a-distance leadership assessment of MB leaders also suggests important implications in terms of mainstream IR theories.

In Chapter 3, we first trace the origins and evolution of Shia political Islam, with a focus on the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the Ayatollahs’ revolutionary vision for the broader MENA region based on exporting the Iranian political-religious model to other countries. This chapter proceeds with succinct psycho-biographies of influential Shia leaders in Iran and Iraq: Ali Khamenei, Hassan Rouhani, Ali al-Sistani, and Nuri al-Maliki. We then discuss the operational code results of the leaders respectively: (1) among each other (a narrow in-group); and (2) compared to the average world leadership norming group (a systemic/world out-group). A discussion as to what kind of generic foreign policy behavior and strategies we should expect from the Shia political Islamist leaders follows, which includes implications of this analysis mainly for Iran’s and, to a lesser extent, Iraq’s relations with the United States, the EU, and regional powers. What do these results and strategies mean for current MENA politics? A discussion on what these results mean about foreign policy decision-making and IR discipline concludes the chapter.

Chapter 4 commences with a compendious historical description of the secular nationalist ideologies in the three Levant countries and compares the secular political movements in these countries as they have different regime types and political cultures. The chapter also provides brief biographical accounts of the three top executive leaders in Syria, Lebanon, and Israel: Bashar al-Assad, Saad al-Hariri, and Benjamin Netanyahu. We then present the operational code results of the leaders and compare them against each other and with other ideological groups. Next, we address the following key questions: What kind of generic foreign policy behavior and strategies we should expect from the studied secular nationalist leaders? What do these results and strategies mean for the current MENA politics and the IR discipline?

Chapter 5 focuses on the leadership of armed nonstate actors in MENA, with special emphasis on their top executive leaders’ foreign policy conceptualizations. We first account for the genesis of ANSAs in the region and stress their emergence and increasing significance for MENA politics by drawing on Reference Dalacoura, Josselin and WallaceDalacoura’s (2001) and Reference Byman and KohliByman’s (2016) prominent works in this vein. Second, brief psycho-biographies of certain prominent leaders of ANSAs in the MENA are presented. These ANSAs leaders include Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi of ISIS, Abdullah Öcalan of PKK, Salih Muslim of PYD, and Hassan Nasrallah of Hezbollah. Last, we discuss the operational code results of the studied ANSAs leaders respectively, with implications for MENA and world politics. The discussion focuses on what kind of leadership ANSAs produce and what it means for states that are trying to contain or negotiate with them. For example, what does the analysis of Abdullah Öcalan’s political beliefs mean for the Turkish government to prevent PKK violence in Turkey or to deal with PKK in Northern Syria? Is Hassan Nasrallah a “rational” leader with whom Israel can negotiate? Is Salih Muslim likely to declare Kurdish/Rojava independence from Syria that may lead to a regional conflict? What do these results mean in terms of FPA’s actor-specific approach, as opposed to IR theories’ actor-general explanations of world politics?

Chapter 6 focuses on the theoretical conclusions of the book. Specifically, we focus on the utility of operational code analysis in explaining individual-level foreign policy decisions, and how different competing ideologies translate into different foreign policy tendencies mediated by individual MENA leaders. The comparative analysis of individual leaders’ operational codes will be broken down into out-group, regional, and world leadership norming-sample comparisons. A specific reference to the usefulness of FPA as a subfield of IR literature is made and ideas for future research are discussed. The concluding chapter synthesizes insights drawn from the analyses and case studies, followed by an expanded discussion of the implications of this research for policy-oriented studies.

In Chapter 7, we zero in on the policy implications and avenues for future research, which build upon the empirical and theoretical findings that we explicate in Chapters 3–6. Our discussion in Chapter 7 revolves around the following questions: What do all the empirical operational code results mean for the current political issues and the day-to-day management of international relations in the MENA region? How do these at-a-distance leadership analysis findings and inferences help us to make sense of MENA’s international relations today? How does the actor-specific analysis in this book cue regional and international policymakers in understanding and engaging with certain political leaders in the MENA region? To address these questions substantially, we utilize a case study approach and focus on four salient political issues that continue to grab headlines in the regional and international media at the time of writing this book: (1) Iran’s diplomatic crisis with the United States (2010–2022) over the Iranian nuclear program; (2) the Egyptian crisis in the post–Arab uprisings era (2011–2014); (3) the ongoing civil war in Syria since the Arab uprisings (2011–2022); and (4) the rise and fall of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and its top leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (2013–2019). We succinctly summarize these four regional crises and bring operational code construct to bear on making sense of these crises from the vantage point of an individual level of analysis.