Introduction

Older adults disproportionately bear the health impacts of natural disasters. Frailty, chronic illness, and limited mobility place many older individuals at heightened risk of adverse health outcomes—including cardiovascular morbidity and hospitalization—and all-cause mortality after extreme weather events (EWEs) like hurricanes; these risks can remain elevated years after the disaster.Reference Adams, Sharon and Taslim1–Reference Gautam, Menachem and Srivastav3 Approximately three-quarters of those who died in Hurricane Katrina, for example, were over the age of 60.Reference Wilson4

Dementia introduces additional layers of vulnerability in disaster settings. Cognitive impairment and memory loss can prevent those with dementia from recognizing danger, following emergency instructions, or finding safety without assistance. Older adults with Alzheimer’s or related dementias, therefore, are fundamentally dependent on caregivers during a crisis.Reference Bell, Miranda and Bynum5 Disaster conditions often disrupt routines and support systems that persons with dementia rely on, as access to medications and caregiving support is interrupted, and familiar environments are upended. These disruptions increase the risk of mortality, as demonstrated in a recent cohort study of older adults with dementia exposed to hurricanes, which showed an increase in mortality following hurricane landfall that peaked after 3-6 months.Reference Bell, Miranda and Bynum5 These findings align with reports that even planned evacuations can be deadly for the cognitively impaired elderly: one analysis of nursing home evacuations during Hurricane Gustav documented a 218% increase in 30-day mortality among residents with severe dementia who were relocated compared to non-evacuated residents.Reference Brown, Dosa and Thomas6 This convergence of cognitive, behavioral, and care-dependence factors makes dementia a potent risk multiplier in disasters.

Older adults residing in institutional settings—a group which overlaps with dementia patients—constitute another especially vulnerable group in EWEs due to their institutional care needs. Skilled nursing facilities (SNF) house older adults, many with significant disability or advanced illness, who depend on complex systems of support and on-site caregivers for survival. Infrastructure failure following EWEs can have devastating consequences in these facilities, including power outages, flood damage, supply disruptions, and staff shortages. SNF residents have been shown to experience significantly higher morbidity and mortality following major hurricanes.Reference Dosa, Skarha and Peterson7 A recent review of the impact of EWEs on health outcomes of nursing home residents by Gad et al. found increased risk of mortality or hospitalization across 10 studies.Reference Gad, Keenan and Ancker8 In one analysis of Florida facilities, exposure to Hurricane Irma was associated with 433 excess nursing home resident deaths in the 90 days after the storm.Reference Dosa, Skarha and Peterson7 Critically, however, most disaster studies in long-term care have examined all nursing home residents as a group, without specifically examining dementia as a modifying factor.Reference Bell, Miranda and Bynum5, Reference Gad, Keenan and Ancker8

Hurricane Sandy’s landfall in October 2012 provides a case study of disaster-induced infrastructure collapse in a densely populated region. Sandy struck the Tri-State area (New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut) with record storm surge flooding and prolonged and extensive power outages, causing widespread devastation. Older adults bore the impact: more than half of the fatalities attributed to Hurricane Sandy were adults aged 60 and above.Reference Kleier, Krause and Ogilby9 In New York City, several nursing homes located in flood zones were inundated by seawater, which knocked out electrical systems and back-up generators.Reference Powell and Fink10 Hurricane Sandy thus represents a severe test of the resilience of SNFs and caregiving systems in the face of post-hurricane infrastructure failure.Reference Lee, Jayaweera and Mirsaeidi11

Given these intersection vulnerabilities—age, dementia, and residence in an SNF—it is critical to determine whether cognitive impairment compounds long-term mortality risk for SNF residents during disasters. However, there has been little research examining dementia as a modifier of disaster outcomes in institutional care environments. As a result, it remains unclear to what extent residents with dementia suffer worse post-disaster outcomes in SNFs, where baseline frailty is high but on-site support is available.

We hypothesized that, following hurricane-related flooding, SNF residents with dementia would experience higher long-term mortality than residents without dementia, reflecting their greater dependence on the stability of facility-based infrastructure, such as staffing and specialized Alzheimer’s care units, and on the broader community context in which those facilities operate.

This study addresses this gap in the literature by evaluating whether dementia diagnosis was associated with increased long-term mortality among short-stay SNF residents in areas heavily flooded by Hurricane Sandy. Its objective is to clarify the role of dementia as a compounding vulnerability in disasters and to inform targeted strategies to protect this high-risk subgroup in future emergencies.

Methods

Study Population, Cohort Definition, Data Sources

The cohort study population included individuals aged 65 years or older who were short-stay SNF residents who experienced flooding due to Hurricane Sandy. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the authors’ home institution. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Privacy Board approved a waiver of informed consent, as research using administrative datasets cannot practicably be carried out without such a waiver.

This study used Medicare fee-for-service claims for beneficiaries who met the inclusion criteria. These included Medicare claims for inpatient and outpatient services, as well as the Master Beneficiary Summary File. These records were linked to Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessments, facility-level data from the Long-Term Care: Facts on Care in the US (LTCFocus) database, and Medicare’s Care Compare for SNFs.

SNF resident clinical characteristics were derived from MDS assessments, which are federally mandated for all SNFs. These assessments include activities of daily living (ADLs) score and Cognitive Function Scale (CFS), as well as information on demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and measures of both physical and cognitive functional status.

The US Census provided census tract-level covariates of general and socioeconomic status and demographic characteristics. Geographic Information System (GIS) data from the US Geological Survey (USGS) Inundation Shapefile, based on USGS field-verified High-Water Marks and Storm Surge Sensor Data, was used to determine flooded ZIP codes.

Exposure: Dementia

This study defined dementia as the presence of a subtype of dementia—Alzheimer’s, vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal, other, or mixed—in at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims, occurring at least 7 days apart during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy’s landfall, as indicated by the Medicare FFS dataset.

Outcomes: All-Cause Mortality

All-cause mortality was defined using the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File as any deaths up to an approximate 5-year timeframe since hurricane exposure.

Other Independent Variables

Individual demographic factors included age, sex, race and ethnicity, comorbidities, Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility, total days spent in a SNF during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy, and number of hospitalizations during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy. Facility level characteristics included total number of beds, indicators of for-profit status, indicators of the facility being part of a chain, indicators of whether or not the facility is hospital-based, indicators of the presence of an Alzheimer’s disease Special Care Unit (SCU), proportion of residents present on the 1st Thursday in April with a CFS greater than or equal to 5, the average ADLs score for all residents present on the 1st Thursday in April, proportion of facility residents whose primary support is Medicare, number of occupied beds divided by the total number of beds, direct-care staff hours per resident day, and proportion of residents admitted during the calendar year who were White. ZIP-code level characteristics included the percent of residents with a college education or higher, and the percent of residents living below the federal poverty line.

Statistical Analyses

Unadjusted comparisons based on whether a subject had or did not have dementia were made using t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

This study used Kaplan-Meier plots to visually inspect the cumulative risk of death for each group.

Risk of mortality was calculated using a Cox proportional hazard model. This study adopted a stepwise strategy of adding variables to this model. With the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), this study assessed if the covariates were collinear using a cut-off of 3. Participants were censored at the end of their Medicare Parts A and B coverage or December 31, 2017 (whichever came first). This study chose 5 years after the hurricane’s landfall to examine 5-year mortality risk because existing long-term mortality studies demonstrate impacts up to 2 years after hurricane landfall, and have not measured risk beyond this range. Finally, this study tested the assumption of proportionality of all Cox models using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals approach.

To address potential unobserved bias in modeling strategy, this study used propensity scoring, a method that reduces confounding by matching subjects on a number of variables relevant to both exposure and outcome. Informed by an integrative framework that links hurricane-related flooding to long-term health via individual demographics, clinical status, pre-event healthcare utilization, facility resources, and neighborhood socioeconomic context—adapted from Waddell et al.’s hurricane-health conceptual model and further shaped by post-acute dementia-care utilization findings and nursing-home disaster studiesReference Dosa, Skarha and Peterson7, Reference Lee, Jayaweera and Mirsaeidi11–Reference Waddell, Jayaweera and Mirsaeidi14—this study included the following covariates in its propensity scoring: age, sex, race/ethnicity, dual eligibility, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, total days spent in a SNF during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy, number of hospitalizations during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy, SNF ownership type, facility size (total beds), direct-care staff hours per resident day, and the median income, percent of residents with bachelor’s degree or higher, and percent of residents below the Federal poverty level of the ZIP code in which the subject resided. This study matched one-to-one, accounting for clustering within matched pairs, at a caliper of 0.5 and a caliper of 0.2. After the matching process, this study then derived both a crude and a fully adjusted hazard ratio for each caliper.

This study also did a subgroup analysis for SNFs with Alzheimer’s dementia SCUs to test the hypothesis that SNFs with SCUs may provide better care in the post-hurricane period compared to non-SCU SNFs.

This study performed all analyses using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata, version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Unadjusted Comparisons

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for SNF residents and SNFs in flooded ZIP codes. The study population included 1,627 individuals (mean [SD] age, 82.35 [8.00]). Compared to patients without dementia, patients with dementia were older (proportion aged ≥ 85 years: 399 [52%] vs 324 [37.7%]; P < 0.001), were less likely to identify as non-Hispanic white (513 [66.9%] vs 647 [75.2%]; P < 0.001), and were more likely to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (479 [62.5%] vs 347 [40.3%]; P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the mean or median Charlson comorbidity values between the two groups (mean [SD]: 4.9 [3.0] vs 4.9 [2.6]; P = 0.95; median [IQR]: 5.0 [3.0, 6.0] vs 5.0 [3.0, 7.0]; P = 0.59). While the median number of hospital stays during the baseline year was not significant, the median number of days at an SNF during the baseline year was (median [IQR]: 35.0 [5.0, 81.0] vs 13.0 [0.0, 43.0]).

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants

Residents with dementia were more likely to be in facilities with a lower proportion of residents whose primary support was Medicare (mean [SD]: 18.2 [14.0] vs 23.1 [18.2]; P < 0.001; median [IQR]: 14.3 [10.1, 20.9] vs 16.8 [11.5, 27.1]), a lower ratio of direct-care staff hours per resident day (mean [SD]: 3.5 [0.7] vs 3.7 [0.8]; P <0.001; median [IQR]: 3.4 [3.2, 3.8] vs 3.5 [3.2, 3.9]), and a lower proportion of residents admitted during the calendar year who were white, though only the mean was significant (mean [SD]: 68.0 [27.5] vs 72.0 [25.6]; P = 0.002; median [IQR]: 77.4 [49.5, 91.3] vs 81.5 [59.3, 92.2]; P = 0.010).

Adjusted Comparisons

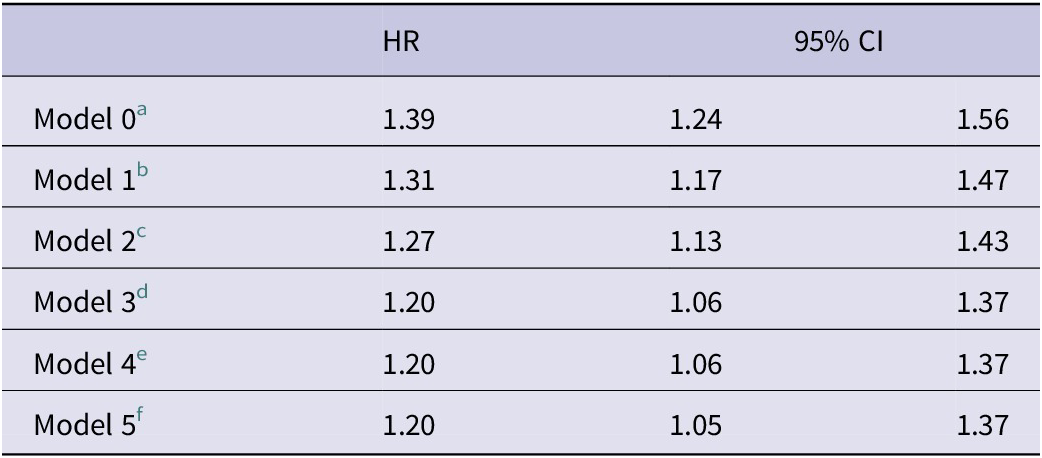

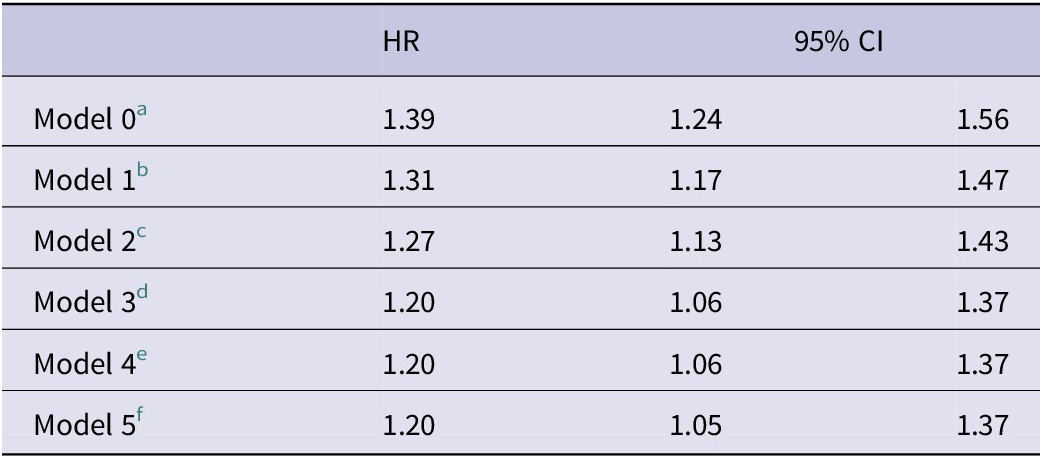

Table 2 presents hazard ratios for individuals with and without dementia who resided in an SNF in a flooded ZIP code during Hurricane Sandy, where the outcome is all-cause mortality. The crude (model 0) hazard ratio was 1.39 (95% CI: 1.24-1.56). Model 1 show adjustments for age and sex (HR [95% CI]: 1.31 [1.17, 1.47]), model 2 adds comorbidity as measured by the Charlson comorbidity index, race and ethnicity, and dual Medicaid status (HR [95% CI]: 1.27 [1.13, 1.43]), model 3 adds facility-level characteristics (HR [95% CI]: 1.20 [1.06, 1.37]), model 4 adds ZIP-code level characteristics (HR [95% CI]: 1.20 [1.06, 1.37]), and model 5 adds total days spent in an SNF during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy and the number of hospitalizations during the year prior to the hurricane (HR [95% CI]: 1.20 [1.05, 1.37]).

Table 2. Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality among individuals with and without dementia who resided in an SNF in a flooded ZIP code during Hurricane Sandy

Notes

a Crude Cox proportional hazard model.

b Cox proportional hazard model incorporating variables of age and sex.

c Cox proportional hazard model incorporating variables from Model 1 as well as the Charlson comorbidity score, dual Medicare-Medicaid status, and race.

d Cox proportional hazard model incorporating variables from Model 2 as well as the following nursing home variables: total number of beds, indicators of for-profit status, indicators of the facility being part of a chain, indicators of whether or not the facility is hospital-based, indicators of the presence of an Alzheimer’s disease Special Care Unit (SCU), proportion of residents present on the 1st Thursday in April with a Cognitive Function Scale (CFS) greater than or equal to 5, the average Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) score for all residents present on the 1st Thursday in April, proportion of facility residents whose primary support is Medicare, number of occupied beds divided by the total number of beds, direct-care staff hours per resident day, and proportion of residents admitted during the calendar year who were White.

e Cox proportional hazard model incorporating variables from Model 3 as well as the ZIP-code level characteristics of the percent of residents with a college education or higher and the percent of residents living below the federal poverty line.

f Cox proportional hazard model incorporating variables from Model 4 as well as the total days spent in an SNF during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy and the number of hospitalizations during the year prior to the hurricane.

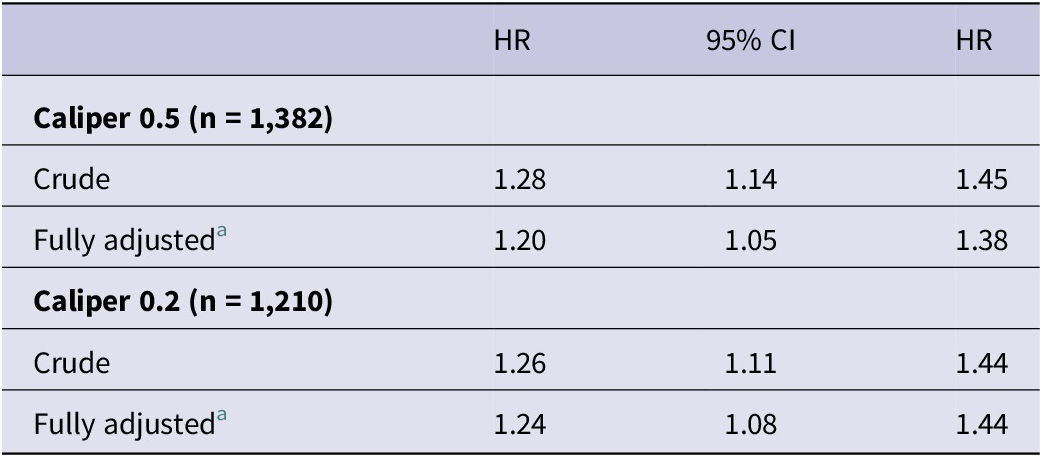

Table 3 shows hazard ratios after one-to-one propensity score matching. At a caliper of 0.5 (n = 1,382), a crude hazard ratio without covariates was calculated (HR [95% CI]: 1.28 [1.14, 1.45]) as well as a model adjusted with the covariates included in model 5 above (HR [95% CI]: 1.21 [1.05, 1.38]). At a caliper of 0.2 (n = 1,210), a crude hazard ratio (HR [95% CI]: 1.26 [1.11, 1.45]) and an adjusted hazard ratio were again calculated (HR [95% CI]: 1.24 [1.07, 1.44]).

Table 3. Hazard ratios after 1-to-1 greedy propensity score matching, accounting for clustering within matched pairs

Note

a Adjusted with the following individual covariates: age, sex, Charlson comorbidity score, dual Medicare-Medicaid status, race; the following nursing home variables: total number of beds, indicators of for-profit status, indicators of the facility being part of a chain, indicators of whether or not the facility is hospital-based indicators of the presence of an Alzheimer’s disease Special Care Unit (SCU), proportion of residents present on the 1st Thursday in April with a Cognitive Function Scale (CFS) greater than or equal to 5, the average Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) score for all residents present on the 1st Thursday in April, proportion of facility residents whose primary support is Medicare, number of occupied beds divided by the total number of beds, direct-care staff hours per resident day, and proportion of residents admitted during the calendar year who were White; the following ZIP-code level characteristics: percent of residents with a college education or higher and percent of residents living below the federal poverty line; and the total days spent in an SNF during the year prior to Hurricane Sandy and the number of hospitalizations during the year prior to the hurricane.

Subgroup Analysis

A subgroup analysis of patients with dementia diagnosis at Hurricane Sandy landfall (n = 767) showed Alzheimer’s SCU residents (n = 78) had a lower unadjusted 1-year survival (HR [95% CI]: 1.19 [0.93, 1.54]); however, this finding was not statistically significant (P = 0.11) (see analysis in Supplement Figure S2).

Limitations

This study has 5 important limitations. First, because this study restricted its analysis to SNFs located in ZIP codes that experienced flooding after Hurricane Sandy made landfall, comparing dementia patients to non-dementia patients, this study did not include a contemporaneous group of residents in unflooded facilities. Thus, the effect size noted (a ~20% increased risk of adjusted mortality) likely is a combination of mortality risk jointly from flooding exposure and the dementia diagnosis. Nonetheless, despite this, we argue the findings are significant because they highlight the unique vulnerabilities of individuals with dementia in post-hurricane settings.

Second, Medicare claims provide only ZIP-code level data, so this study could not verify flooding at the level of individual facility or resident. This spatial imprecision likely biases effect estimates toward the null but cannot be ruled out as a source of misclassification. Third, this study was unable to stratify by dementia subtype (e.g., Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia). Prior studies show that survival trajectories differ across subtypes, so important heterogeneity may be masked.Reference Ono, Sakurai and Sugimoto15 Because the MDS includes instruments such as the CFS, future work could stratify by dementia severity to assess whether mortality risk is concentrated in those with advanced impairment. Fourth, evacuation status was not measured, and differences in decisions to evacuate or shelter in place—as well as the success of evacuation efforts—may have differentially affected residents with dementia and contributed to the observed mortality gap. We recognize this as an important area of future research, given ambivalence in the literature as to the effects of sheltering-in-place vs evacuation and the long-term health outcomes associated with these strategies for nursing home residents.Reference Hua, Patel and Thomas13, Reference Dosa, Hyer and Thomas16 Finally, as a retrospective observational study, residual confounding from unmeasured or incompletely measured variables may persist despite multivariable adjustment and propensity-score matching.

Discussion

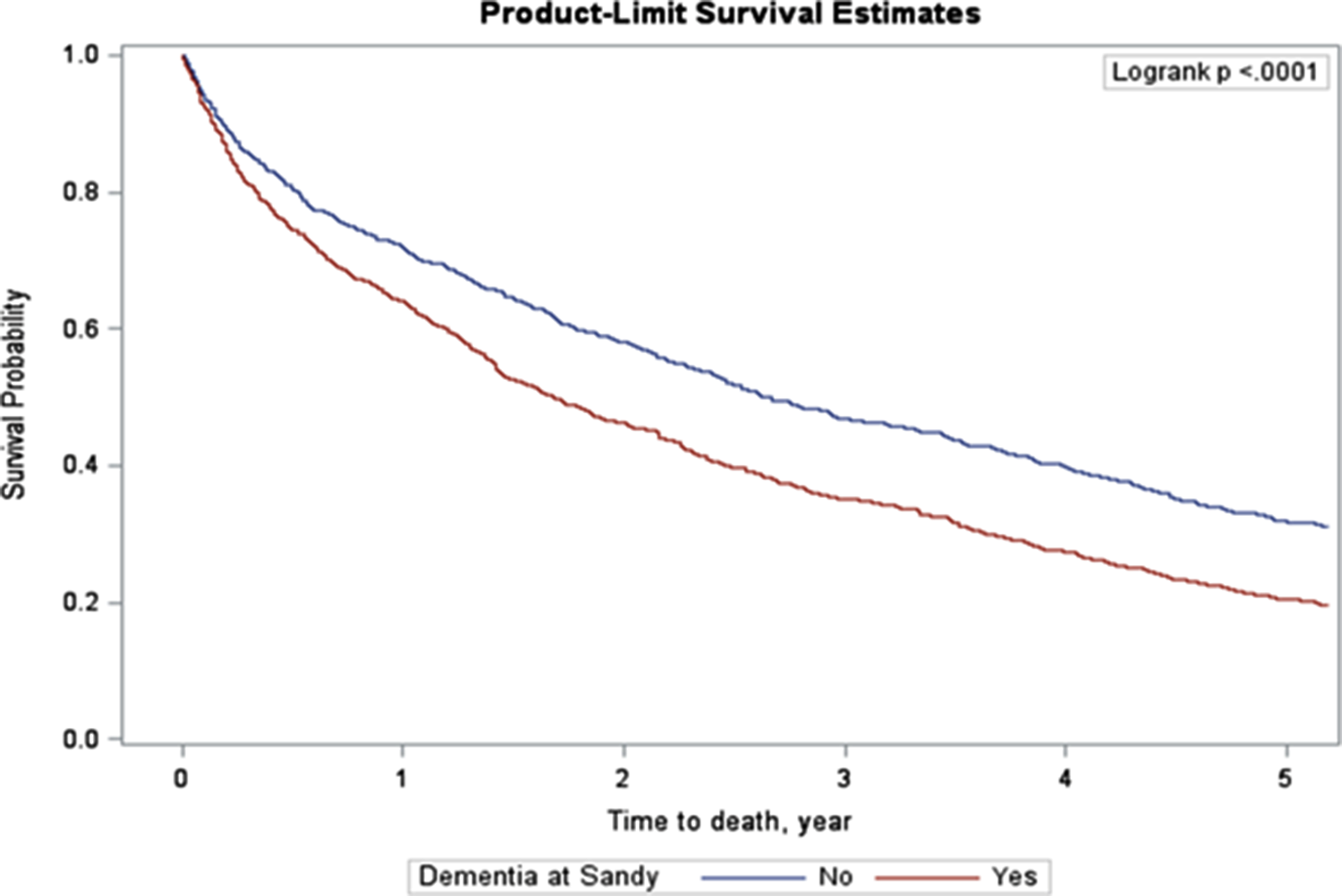

In this retrospective cohort of 1,627 SNF residents whose facilities flooded during Hurricane Sandy, dementia was associated with a 20% increase in the hazard of all-cause mortality over 5 years (fully adjusted HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.05-1.37). Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 1) showed that survival in the dementia group diverged early and remained lower throughout follow-up, yielding a median survival of 1.68 years among residents with dementia versus 2.61 years among residents without dementia. Applying the fully adjusted HR of 1.20 and the 47% prevalence of dementia, this study estimates that ~8.6% of all deaths (≈104 of 1,205) were attributable to dementia beyond the baseline risk conferred by age, comorbidity, and facility and neighborhood factors. These data indicate that the excess risk attributable to dementia is not confined to the acute post-disaster period, but persists for years.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curve comparing SNF residents with and without dementia within 5 years of Hurricane Sandy landfall.

This study’s 5-year adjusted hazard ratio is directionally consistent with 2 prior disaster studies that used different effect measures and comparison groups. Bell et al. examined >346,000 Medicare beneficiaries with and without pre-existing dementia who resided in FEMA-declared disaster counties during Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, or Florence, tracing monthly all-cause mortality 12 months before landfall through 12 months after, and calculating attributable risks, attributable fraction, and relative risks (RRs).Reference Bell, Miranda and Bynum5 They found an overall 12-month RR of 1.08 (95% CI 1.07-1.09); hurricane-specific RRs were 1.12 for Harvey, 1.07 for Irma, and 1.09 for Florence. Dosa et al. focused on all Florida SNF residents (irrespective of dementia diagnosis) and compared post-Irma mortality with outcomes for residents of the same facilities over the same time period 2 years earlier.Reference Dosa, Skarha and Peterson7 They found 30-day and 90-day risk ratios of 1.12 and 1.07, respectively—i.e., a 12% and 7% increase in short-term death risk attributable to hurricane exposure when the baseline is a pre-event year in identical facilities.

SNF preparedness offers several concrete pathways by which dementia could translate into sustained excess mortality after a post-hurricane flood. First, residents with dementia rely on stable, round-the-clock caregiving routines; when an SNF loses power or staff during a storm, behavioral cues, medication timing, and fall-prevention protocols break down, leading to delirium, injury, or accelerated functional decline.Reference Brown, Dosa and Thomas6 Second, environmental hazards that arise inside an under-prepared facility can act as chronic stressors: failed heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems elevate indoor temperatures, damp walls foster mold growth, and disrupted food supply chains alter diet quality—each of which can worsen cardiopulmonary disease and potentially accelerate neurodegeneration in cognitively impaired residents.Reference Hasegawa, Yoshino and Yanagi17–Reference Chu, Warren and Spatz22 Third, observational data show that injury-related hospitalizations carry higher case-fatality among dementia patients.Reference Harvey, Mitchell and Brodaty23 Finally, post-disaster service gaps persist well beyond the initial emergency; for example, NYU Langone remained partially closed for 59 days after Hurricane Sandy landfall,24 and some outpatient services in flooded ZIP codes were disrupted for months, prolonging barriers to medical follow-up.Reference Lee, Jayaweera and Mirsaeidi11 In short, the degree to which a SNF’s physical infrastructure, staffing, and supply networks are disaster-ready may modify the impact and duration of dementia as a risk factor for increased all-cause mortality. Strengthening these facility-level preparedness domains is therefore essential to mitigating long-term disaster risk in this high-vulnerability population.

Although this study adjusted for direct-care staff hours per resident day, the evidence linking staffing levels or staff training to mortality outcomes in disaster settings remains limited. Most disaster studies in skilled nursing care focus on evacuation rather than personnel factors.Reference Gad, Keenan and Ancker25 Nonetheless, consistent staffing and dementia-specific training are likely critical for maintaining routines, preventing delirium, and ensuring timely care during crises—mechanisms that warrant further investigation in future research.

This study hypothesized that a dedicated SCU could buffer these risks by concentrating trained staff and dementia-friendly design features. Its analysis showed a lower unadjusted 1-year survival for SCU residents; however, this result was not significant. Larger datasets are needed to clarify whether specialized dementia units mitigate or merely select for higher risk.

Key strengths of this study include linkage of Medicare claims, MDS assessments, facility-level characteristics, and GIS-based flood exposure; a 5-year horizon, longer than most disaster-mortality studies; and rigorous adjustment plus propensity-score matching that yielded consistent estimates.

Conclusion

This study’s 5-year follow-up of 1,627 storm-surge-flooded SNF residents shows that dementia is not just an acute-phase vulnerability but a persistent amplifier of mortality: residents with dementia faced a 20% higher death hazard and survived nearly a year less than their cognitively intact peers. This long-tail risk underscores the need to move toward research-informed solutions. Future work should do four things. First, disentangle absolute flood effects by pairing flooded and non-flooded facilities within the same event and tracking recovery metrics such as power, water, and staffing restoration. Second, test facility-level interventions—backup generators sized for HVAC, dementia-trained surge staff, and resilient unit layouts—through prospective studies, as well as study post-disaster strategies to mitigate harm to individuals with dementia. Third, stratify analyses by dementia subtype and severity to pinpoint residents who would benefit most from targeted protections. And fourth, integrate healthcare-utilization variables and neighborhood social-vulnerability indices into disaster-risk models to refine triage and resource allocation. Rigorous work along these lines may lay the groundwork for interventions that more effectively safeguard cognitively impaired residents during flood events.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2025.10280.

Author contribution

NA contributed to study conception and drafted the manuscript. OS contributed to study conception, performed the statistical analysis, and assisted with manuscript writing. AK conceived the research topic and assisted with manuscript writing.

Funding statement

This work was supported with funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08HL163329 Ghosh) and the National Center for Advancing Clinical Translational Science (R03TR004976 Ghosh).

Competing interests

None.