Introduction: Rewilding for a new earth beyond life-forgetfulness

This article assumes that life on Earth is currently constrained by dominant, life-forgetfulFootnote 1 and life-hostileFootnote 2 societal structures (Nørreklit & Paulsen, Reference Nørreklit and Paulsen2023). Consequently, we inhabit a world where prevailing human norms and actions limit and harm life within the life-critical zone — the area near the Earth’s surface supporting life (Latour, Reference Latour2017; Lin, Reference Lin2010; Paulsen, jagodzinski and Hawke, Reference Paulsen, Jagodzinski and Hawke2022; Nørreklit & Paulsen, Reference Nørreklit, Paulsen, Paulsen, jagodzinski and Hawke2022). We explore how arts education might instead foster life-friendly relationships with the world (Brückner & Paulsen, Reference Brückner, Paulsen and Windsor2025), while investigating whether arts-based approaches can disrupt the current situation, where earthly life is severely restricted by human dominance. By life-friendly we signify any attempt to pay heed to and approach life (as a whole, as singular living beings and as an impersonal process) in a friendly manner, i.e. ways conducive to life, to make it flourish and thrive, and thus affirm and support life, but also seek guidance and inspiration from life, i.e. listen to what life — in the broadest sense — has to say about how to live a full life of mutual flourishing and co-thriving.Footnote 3

We concur with those advocating the need for a complete transformation of how we live (Varpanen et al., Reference Varpanen, Kallio, Saari, Helkala and Holmberg2024). This is in alignment with three central tenets within wild pedagogies literature (Blenkinsop, Morse & Jickling Reference Blenkinsop, Morse and Jickling2022): (1) the Earth’s current climate and environmental state threaten countless species, including humans; (2) effective responses require a radical rethinking of values and ways of being that oppose life-reductive practices; and (3) education is crucial for this fundamental rethinking of ideas and practices, breaking free from life-constraining norms (Blenkinsop et al., Reference Blenkinsop, Morse and Jickling2022; Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse & Jensen Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse and Jensen2018). In addition, we are inspired by the touchstones developed within wild pedagogies literature (Blenkinsop et. al, Reference Blenkinsop, Morse and Jickling2022), emphasising, for instance, nature as a co-teacher, making room for surprises, listening to the living world, opening up imaginative spaces, building flourishing communities across the human-more-than-human span, disrupting prevailing modern norms and hereby pushing education to co-foster needed eco-social-cultural change.

However, simply opposing control and dominance presents risks (Fettes & Blenkinsop, Reference Fettes and Blenkinsop2023). Mere dismantling could lead to worse outcomes. As Bennett (Reference Bennett2001), drawing upon Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1986), suggests, we must proceed cautiously when disrupting, dislodging, and rewilding, resisting the temptation of total freedom and disorganisation. The goal is not negation, but rather the thoughtful creation of something different, robust and life-friendly (Paulsen, Reference Paulsen, Petersen, von Brömssen, Jacobsen, Garsdal, Paulsen and Koefoed2022b). Ontologically, wild life transcends simple disorder; it is a dynamic interplay of order and disorder, resonance and dissonance, a continuous process of becoming (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze1993).

Our focus is on arts education, not solely due to our personal interests, but because its open experimentation with forms offers a potential starting point for rewilding education. We are interested in arts-mediated education as experimental and disruptive research, creating spaces for unpredictable subjectification (Biesta, Reference Biesta2017; Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Reference Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles2022). Such spaces offer alternative ways of relating to life, contrasting with dominant practices that harm flourishing life and constrain thought, action and response (Anundsen & Illeris, Reference Anundsen, Illeris, Østern and Knudsen2019; Blenkinsop et al., Reference Blenkinsop, Morse and Jickling2022; Roy, Reference Roy2003). Thus, we apply arts education as a means of relating to more-than-human life and engaging in the creative process, embracing unpredictability, openness, and relationality (Fredriksen & Groth, Reference Fredriksen and Groth2022; Illeris et al., Reference Illeris, Fossnes and Anundsen2024). Understood in that way, arts education might generate knowledge beyond purely calculative, techno-scientific paradigms (Illeris & Skregelid, Reference Illeris, Skregelid, Østern, Illeris, Knudsen, Jusslin and Holdhus2024).

Thus, this article speculates on rewilding through arts practices that might foster life-friendly education. Rejecting a simplistic human/wild dichotomy, we view wildness as self-willed or self-emerging flourishing life, potentially inclusive of both humans and more-than-humans, fostering mutual flourishing within relational and sympoietic processes (Blenkinsop et al., Reference Blenkinsop, Morse and Jickling2022; Blenkinsop & Kuchta, Reference Blenkinsop and Kuchta2024). Life-friendly practices attune to life’s multiplicity, supporting and nurturing its self-emergence, diversity, and vibrancy (Paulsen, Reference Paulsen2023). Echoing Bennett’s assertion that loving life precedes caring for anything (Bennett, Reference Bennett2001), we acknowledge the inherent links between friendliness, friendship, care and love (Brückner & Paulsen, Reference Brückner, Paulsen and Windsor2025).

Arts educational responses to current life-forgetfulness

In this section, we outline three arts-based educational responses to contemporary predicaments, aiming to identify potential life-friendly practices.Footnote 4 We suggest these to examine the intentions, reactions and potential outcomes of various arts educational practices (presented in subsequent sections) that might dislodge normalised practices, thus fostering life-friendly relationships with life (Illeris & Paulsen, Reference Illeris, Paulsen, Østern, Illeris, Jusslin, Holdhus and Knudsen2024; Illeris, Reference Illeris2012a; Nørreklit & Paulsen, Reference Nørreklit, Paulsen, Paulsen, jagodzinski and Hawke2022). The three responses we want to speculate with are these:

(1) The Modern Compensatory Response. This response attempts to compensate for the violence and control inherent in dominant modes of human existence within the contemporary precarious situation (Jukes, Reference Jukes2023). In education, this might involve taking students into nature (e.g., a forest) for less structured activities — a temporary break from the classroom setting. Students might engage in nature-inspired art, creating a contrast to the pressures and limitations of conventional education (Roy, Reference Roy2003). Such a response, however, may reinforce binary oppositions such as culture/nature, indoor/outdoor, standard/exceptional education and may reinforce a view of nature as something external to culture, available for human use (Illeris et al., Reference Illeris, Paulsen, Østern, Illeris, Jusslin, Holdhus and Knudsen2024; Illeris, Reference Illeris2012b).

(2) The Critical-Disillusional Response. This response critiques the nature/culture dichotomy, recognising that we live in the Anthropocene, where human activity profoundly impacts all life within the life-critical zone (Paulsen, Jagodzinski & Hawke Reference Paulsen, Jagodzinski and Hawke2022). The concept of pure, untouched nature is obsolete; human influence now pervades all life. Consequently, this response focuses on the impact of human actions on the environment. In arts education, this might involve creating art that reflects the “wasteland” resulting from human dominance (Illeris et al., Reference Illeris, Paulsen, Østern, Illeris, Jusslin, Holdhus and Knudsen2024; Illeris, Reference Illeris2012a). Yet, the drawback of this response is that it overemphasises human influence. It fails to recognise that more-than-human life creates new life beyond human impacts, but also penetrates everything human beings do (because everything they do can only be done because they are living beings in a living world).

(3) The Life-Opening Response. This response engages with emerging more-than-human life, acknowledging its transformative power. It seeks to support and align with self-emerging life, potentially contributing to a deconstruction of the Anthropocene (Illeris et al., Reference Illeris, Paulsen, Østern, Illeris, Jusslin, Holdhus and Knudsen2024; Paulsen, Reference Paulsen2023). Arts educational practices might involve attending to life’s own powers, even in seemingly damaged or impacted environments (e.g., a landfill). The aim is to foster co-flourishing with diverse life forms, recognising that creative potential is not solely a human attribute but inherent in life itself (Bergson, Reference Bergson1998). In arts education, this might involve fostering unpredictable arts practices that rewild education, aiming for a future where life is nurtured. Such practices aim to disrupt established norms, fostering alternative ways of being in the world (Paulsen et al., Reference Paulsen, Jagodzinski and Hawke2022). This response moves beyond simply critiquing human impact to actively support life’s flourishing.

The following sections will explore three specific arts educational practices. In each case, we will draw on the outlined art educational responses to discuss to what extent the practices can be twisted in more or less life-friendly directions. By twisting we mean altering the framing of a particular practice, without making it into a totally different practice. Using a post-qualitative lens (St. Pierre, Reference St Pierre2021; Malone & Crinall, Reference Malone and Crinall2024), we speculate how twisting each practice might promote life-friendly education and foster new relationships with the living world. Our focus lies not on exhaustive documentation, but on imaginative exploration and exemplification of pathways.

Practice # 1: Poetry and nature writing

Writing is a central educational concern. Even before formal schooling, writing served as a meaningful human practice, a means of engaging with the world through language (Ingold, Reference Ingold2022a; Reference Ingold2022b). On the other hand, writing can be seen as a form of distancing from the living world that contributes to its forgetfulness (Abram, Reference Abram1997), especially when it privileges abstract and disembodied forms. However, we can hypothesise that certain writing practices could be twisted in order to promote a different kind of experience, towards life-opening forms of relationships between the subjects and the living word. Creative writing, in particular, occupies a unique space within education, bridging linguistic education, arts education, and broader pedagogical approaches. This section explores creative writing practices — specifically, poetry — that emphasise the dynamics of relationships with nature and places (Blenkinsop & Kuchta, Reference Blenkinsop and Kuchta2024; Sobel, Reference Sobel2004). These practices provide different opportunities for teachers and students to engage in generative dialogues with these places and they acknowledge nature’s inherent educational agency (Ford & Blenkinsop, Reference Ford and Blenkinsop2018; Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse and Jensen2018; Quay & Jensen, Reference Quay and Jensen2018).

This study employed place-based writing (PBW) practices within an upper secondary school in north-eastern Italy. Using a participatory action research framework (Kemmis, McTaggart & Nixon Reference Kemmis, McTaggart and Nixon2014), a research group comprising three literature teachers (L1) and three outdoor educators, coordinated by Tommaso Reato, conducted the project.

PBW encompasses diverse educational practices situated at the intersection of place-based education and writing pedagogies (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2011; Montgomery & Montgomery, Reference Montgomery and Montgomery2024). PBW has been widely used to foster student connections with their communities, developing place attachment and civic skills (Brooke, Reference Brooke2003; Donovan, Reference Donovan2016; Esposito, Reference Esposito2012). Creative PBW has been studied theoretically (Case, Reference Case2017; Harper, Reference Harper2024), regarding the development of linguistic skills (Neville et al., Reference Neville, Petrass and Ben2023) and in relation to wild pedagogies (Jickling & Morse, Reference Jickling and Morse2022). The process of attuning with places through creative linguistic practices is also explored in some relevant studies about indigenous ways of knowing and researching (Arnold et al, Reference Arnold, Atchison and McKnight2023; Poelina et al, Reference Poelina, Perdrisat, Wooltorton and Mulligan2024).

The theoretical underpinnings of this practice draw on Ricoeur’s (Reference Ricoeur2020) work on metaphor. The French thinker, starting from a hermeneutic approach, attributes a referential capacity to metaphor that emerges as an authentic way of knowledge. Guardini (Reference Guardini1995) further emphasises poetry’s role in giving voice to human encounters with the living world, mirroring humanity’s earliest experiences with nature (Guardini, Reference Guardini1995, p. 25).

The PBW practices included diverse indoor and outdoor, theoretical and experiential activities. Settings included a school garden, city parks, and an educational farm. Activities involved embodied experiences, writing experiments, and group reading and reflection. These practices engage with arts education in two ways: (1) formally, integrating with language curricula and exploring disciplinary content (e.g., poetic form and rhetorical figures); and (2) broadly, fostering life-friendly relationships between students, humans and more-than-humans, thereby cultivating life-friendly perspectives within the school system (Paulsen, Reference Paulsen2023).

Perceive more and think for yourself: student voices from the woods

We will now present and comment on two poems composed by two teenage students at the vocational school involved in the research: Riccardo and Marco. The interpretations of the texts will be accompanied by insights regarding their lived experience of PBW, explored through an interview with the young authors within a framework of narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, Reference Clandinin and Connelly2000). We will attempt to reread these materials through the interpretive lenses proposed in the opening sections of the paper. Both students participated in a poetry workshop conducted in an urban forest; the writing assignment was quite open and began with the tentative title suggested by the teachers, “The forest is like me.” The first text is by Riccardo, a turbulent, extroverted and nature-loving student:

The forest is like me

A set of land

Leaves and trees.

A flowing stream

Slow.

And a boy who gets lost

in its mystery.

The first part of the text is descriptive and appears to capture the context in which the writing experience took place: a forest on the outskirts of the city. The second part offers a personal image, where Riccardo expresses his struggle with the questions that crowd his mind regarding the future. Riccardo notes that he was inspired by the metaphor of getting lost during the blindfolded walk in the woods that preceded the writing moment; this theme also serves as an archetypal metaphor for the woodland experience, with numerous examples in the history of literatureFootnote 5. The content of the poem seems to represent the modern compensatory response very well, reflecting a romantic idea of nature as a mirror of interiority. However, the exploration of the student’s lived experience invites consideration of some elements of the life-opening response. Indeed, during the interview, Riccardo shares the challenge of translating into words the perceptive fullness experienced in contact with nature. The process of PBW is described by Riccardo as a perceptive broadening, a time of attentive intensity set in motion by the concrete relationship with the outdoors.

You have to know how to listen: if before I heard a bird, now maybe I hear a bird and the stream. If before I could smell mint, now I can smell mint and rose. Let’s say that really, it opened me, it opened me. The sensations that come to me are just more. The sensations are more and deeper, more enriched, more full-bodied (interview).

An inverse path seems to describe the experience of Marco, a student in the same class who is introverted and occupies a newcomer position in the peer group. His poem appears to be entirely descriptive, as if he intends to give full voice to the here and now of his encounter with the place:

The forest is like me

In the quiet of this forest

The light blowing of the wind

He rubs through the leaves

Without knowing it

Soon they will hug

The land making it

Then an integral part.

In this case as well, the interview reveals more about the process and the meaning of the experience. The significance of the described process is intertwined with an autobiographical reason: Marco recognises in it his journey of integration with the new class group after changing schools the previous year. We are dealing with what Ricoeur referred to as a living metaphor (2020): a re-description of reality that opens new meanings by connecting two or more different processes.

The role of the more-than-human beings in this process seems quite clear, both as partners in learning and as co-teachers (Ford & Blenkinsop, Reference Ford and Blenkinsop2018; Quay & Jensen, Reference Quay and Jensen2018). Marco emphasises how being in nature, alone and in silence, while listening to the sounds of nature, helped him distance himself from group dynamics, making him feel “calmer, more confident” (interview) and more in tune with his feelings and thoughts. It appears that nature has interrupted some relational dynamics present in the class group, thanks to solitude, silence and the rich sensory landscape, which opened unexpected possibilities for being present (Biesta, Reference Biesta2021).

These two experiences reveal many elements for discussion. First, it is necessary to emphasise the relevance of the process dimension. The analysis of the poetic texts written by the students, although linguistically simple, seems to highlight mostly romantic themes; it is only by reflecting on the writing experience through interviews that significant aspects of the practices can be grasped. In particular, we recognise a certain tension between attitudes and dynamics typical of the modern compensatory response, which is connected to a particular lyrical or romantic atmosphere emerging from the content of the poems, and signs of openness and dialogue with the place, which evoke the life-opening response. In this direction, a life-friendly perspective seems evident, especially considering the writing process, which represents a true entanglement of subjective motives and suggestions connected to the place, a sort of dialogue between students and place. Sounds, colours and concrete observations are often described as the crucial elements of inspiration for the generation of meanings, as a student noted: “with words I tried to translate what nature was trying to tell us, with the noises, those sounds it made.”

We also find it significant that a strong personal and subjective dimension emerged, in which the singularity and uniqueness of life is expressed (Nørreklit & Paulsen, Reference Nørreklit, Paulsen, Paulsen, jagodzinski and Hawke2022), when students took the opportunity to give voice to their unique existential situations and search for meaning.

Finally, it should be noted that twisting towards openness was one of the intentions of the practice and that it was promoted by inviting a sort of educational epoché (Waldenfels, Reference Waldenfels2023), both for the type of bodily experiences and the linguistic invitations. The idea of suspending control to encourage dialogue between students and place implies a process of emergence, and resonates with the second touchstone of Wild Pedagogies, where spontaneity and emergence are discussed (Blenkinsop et al., Reference Blenkinsop, Morse and Jickling2022; Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse and Jensen2018). In addition, it should be noted, that there is an absence of elements of the critical disillusional response, in both cases presented, and in the overall writings and voices of the students. We can speculate that an eco-critical interest was not on their agenda, while a lyrical approach is perhaps more common within the Italian cultural context. Nevertheless, the practice fostered a certain critical movement as students reinterpreted conventional classroom teaching as judgmental, disembodied and cold compared to the outdoor learning experiences.

Practice # 2: Propositions

In Southern Norway, at the faculty of fine arts of the University of Agder (UiA) I, Helene Illeris, has experimented with the practice of propositions as part of Bachelor- and Master’s courses in arts education together with my colleagues Tormod W. Anundsen and Lisbet Skregelid (Illeris & Anundsen, Reference Illeris, Anundsen, Paulsen and Tække2024; Illeris & Skregelid, Reference Illeris, Skregelid, Østern, Illeris, Knudsen, Jusslin and Holdhus2024). “Propositions” as a form of pedagogical practice was originally proposed by the American process philosopher Alfred North Whitehead (Reference Whitehead1978), who defined the proposition as “a hybrid between pure potentialities and actualities (pp. 185-186).

Inspired by Whitehead and by the use of propositions by the Canadian philosophers Erin Manning and Brian Massumi (Reference Manning, Massumi, Faber, Halewood and Davies2020), we have involved our students as research partners in case studies, adopting methodological approaches from participatory action research similar to those employed in practice # 1 above (Kemmis et al., Reference Kemmis, McTaggart and Nixon2014; Illeris & Skregelid, Reference Illeris, Skregelid, Østern, Illeris, Knudsen, Jusslin and Holdhus2024). We introduced the task to the students by presenting them with the following introduction to the concept of propositions (also quoted in Illeris, Reference Illeris, Paulsen, Jagodzinski and Hawke2022:187):

A proposition is as an open invitation that someone/something offers to you

It is not an assignment but an occasion to open your worldviews and let them develop in new and unexpected directions

Instead of explaining and simplifying, a proposition maintains and explores complexity

A proposition works from a premise of equality instead of hierarchy

A proposition is an occasion to experience sensuous knowledge in the making

A proposition is a practice, meaning that you can only create propositions by practicing them yourself before you offer them to others

We ask the students to elaborate propositions to each other in pairs through different forms of practice and in relation to a theme. Examples of themes that we have been working with have included: “paradoxes in society,” “‘sensuous sustainability education” and “resonance in the Anthropocene.” The students experiment with propositional practices as a form of relational art (Bourriaud, Reference Bourriaud2002), meaning that the sensuous, aesthetic and provocative qualities that characterise contemporary art forms are to be found within the relationships to the world created by the propositions. Whitehead (Reference Whitehead1978: 187) writes: “A proposition is an element in the objective lure proposed for feeling, and when admitted into feeling it constitutes what is felt.” (Italics in original).

The process of the students (in pairs) goes like this: First they sketch some lines that could be used for a proposition. As inspiration, each of them has brought an image from home that represents how they relate affectively to the theme, e.g., of the Anthropocene. For example, the two master students Ingvild and Veslemøy worked with the following proposition (shortened version):

Go out in nature […]. Walk in silence. […] Find a man-made object that does not belong in the surroundings. Decide by yourself if you will remove the object or if it should remain. […]” (translated quote from Illeris et al., Reference Illeris, Anundsen, Paulsen and Tække2024:249).

The practice was then to try out how the proposition could be experienced and if and how it could eventually be changed, before handing it over to someone else. For example, the above proposition might turn into something simpler like: “Go out in nature. Find a man-made object that does not belong here. Relate to it” — or even the simplest proposition that has been created by our students so far: “Make a difference.”

In the second part of the assignment, the proposition is given to one of the other pairs — like a gift, with no explanations, maybe in the form of a letter. The receivers then will practice and experience the proposition their way.

At the end of the workshop (occurring over 2–3 days), the pairs present their work to each other — both how they developed their own proposition and how they enacted and experienced the proposition that was given to them.

Propositions as a way of embracing life-friendly practices in arts education

The arts educational practice described above is developed to challenge students’ possible conceptions of 1) arts education as something that leads to some kind of independent product, e.g. a painting, a concert, a show; 2) arts education as a purely aesthetic activity focused on “giving form,” e.g. to experiences of nature like in the compensatory modern response; 3) arts education as sustaining critical consciousness, e.g. by questioning life-forgetful ways of treating the environment like the critical-disillusional response; 4) arts education as a way of “finding solutions,” e.g. on how to deal with the facts of global warming by expressing your feelings in a therapeutical manner.

In the thought example above, one could see how the students tend to mix different responses to current life-forgetfulness by beginning with the idea of “going out in nature” and “walking in silence,” which could be related to a modern-compensatory response of enjoying nature as a contrast to culture, an exception from a daily life of constraints. The next step, “Find a man-made object that does not belong here,” could then be seen as a critical-disillusional response, a consciousness of the fact that such a thing as “nature” does not exist in its pure form, because traces of human activities are found everywhere “polluting” nature with “unbelonging” phenomena. Finally, the last short imperative, “Relate to it,” might be connected to a more life-opening response where the receiver of the proposition is left to artfully play with what s/he has found and experienced, opening her-/himself to invigorating creative powers of the actual place including both “nature” and “man-made-objects” and the ongoing intertwining of the two. In her reflections on her work with this proposition, one of the students wrote:

[…] I removed it [the man-made object], but what about the empty space that was left? […] After all, nature had already started to fix it, hiding, covering, adapt itself, and then I came and took the object away? […] I removed it, and I thought about our use of the word ‘natural beauty’ and when we want something to look untouched. I felt we started a dialogue […] and that the forest looked at itself through me. Sounds a little awkward, but in that very moment this was how it felt” (Ingvild in Illeris et al., Reference Illeris, Anundsen, Paulsen and Tække2024:250, own translation)

This situation, and in particular the last part where the student writes that she felt “that the forest looked at itself through me,” could be interpreted as a possible twist towards a life-friendly education where different modes of being in the world intertwine — Ingvild’s body, nature, the object, the empty space left by the removal of the object, and the dialogues between them, looking and looking back. Following this line of thought, one could even imagine further twists by asking more-than-human agents, for example, a flower or an empty can, left in nature, to propose their own propositions. Who knows, maybe a flower or a can already formulate unspoken propositions though their being, propositions like “Touch me with your human body. Feel if and how our bodies connect.” In this way, working with propositions opens for possibilities of creating art with life instead of only about life. Art that is — as Whitehead (Reference Whitehead1978:185–186) puts it — “a hybrid between pure potentialities and actualities.”

Practice #3: Minor experiences

Becoming friends with life is not easy, but which genuine friendships are easy anyway? To find ways, Jane Bennett suggests, in our interpretation, that it might be helpful to cultivate ourselves to become open to and co-create minor experiences, consisting of moments of enchantments, from which attachments to life and love for the world can flow (Bennett, Reference Bennett2001; Paulsen, Reference Paulsen2022). Such moments can be cultivated and intensified by artful means, as an uneasy combination of artifice and spontaneity (Bennett, Reference Bennett2001:10). In accord with Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1986), minor experiences indicate moments that break off, and open up to alternative worlds, but are discarded, ignored, suppressed, marginalised, rejected or made irrelevant by dominating norms and structures, not least in modern mainstream techno-bureaucratic education (Roy, Reference Roy2003).

The wonder of some minor experiences — and the artificial ways to cultivate and create such — can be shared here, gathered through three post-qualitative speculative experiments (St. Pierre, Reference St Pierre2021) that correspond with Jane Bennett (Reference Bennett2020), Eric Nelson (Reference Nelson2020) and Bron Taylor (Reference Taylor2009) respectively. The three experiments have been caried out four times, in each case making up “a life-friendly walk” conducted and iterated by me, Michael Paulsen, together with different people (ten to sixty, age 0–80) and more-than-human life between 2022 and 2024, in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Italy.Footnote 6

Onto-sympathies

The first experiment invites participants to become aware of what Bennett has termed onto-sympathies (Reference Bennett2016; Reference Bennett2017a; Reference Bennett2017b; Reference Bennett2020; Paulsen, Reference Paulsen2022). The idea is to create a presence in the world where this awareness is intensified. Onto-sympathies emerge when one body injects sympathy into another, resulting in positive attraction and affection between them.

In the experiment, participants are provided with examples of possible onto-sympathies that arise from encounters with the living world and are then asked to move slowly around an area with more-than-human life, trying to notice any emerging onto-sympathies in their interactions with the surroundings. After a period of 10 to 20 minutes, we gather to share our experiences. Most participants have noticed some onto-sympathies, for example by lying on the ground and attending to the wind, sun, plants, animals, fungi, etc. Some are surprised by the existence and power of these, while others become fascinated with a specific being that attracted them.

In one instance, a child reported becoming aware of a little bird sitting on the forest floor in front of them, and they began to gaze at this delicate creature with tenderness and care, recognising its fragility amid the vastness of the big forest. Then, the child looked up, mirroring the little bird and realised that they, too, are a small creature in a big world, surrounded by towering trees and the expansive sky. In another case, a participant was profoundly moved by an encounter with a stone (and its cavity; see photo below), which felt friendly and inviting. The participant described a sense of being welcomed, akin to coming home:

The encounter with the stone’s cavity, where over millennia, stagnant moving time has transformed an unbroken whole into a fragmented whole. Something grows and lives velvety and friendly [..] A moss-soft bed for [..] sleep and all the world’s micro-life.Footnote 7

Doing-nothing: staying with the life

A second experiment invites participants to go individually or in small groups to specific positions in an area (which they choose themselves or are guided to by the place) and remain there for a set time (10, 15 or 20 minutes), focusing on the life occurring around (or in) them. They are to attend carefully to this life, supporting it only if prompted, while otherwise remaining attentive to what unfolds from their chosen location. This exercise is inspired by Daoist concepts of wuwei and ziran, contextualised within today’s environmental crisis (Nelson, Reference Nelson2020). Ziran refers to what spontaneously arises from itself (relationally and dynamically), while wuwei, meaning non-doing, signifies a non-dominating and receptive attitude toward ziran (life). In this sense, one engages in “doing nothing” by listening to and following the unfolding of life.

As in the first experiment, participants gather after a while to share their experiences of “doing nothing.” Many were surprised by the abundance of life they experienced. One older participant recounted sitting by a small waterhole, stating he had never seen so much life in his entire life as he did in just 15 minutes of doing nothing by the waterhole. He noticed a dragonfly who repeatedly visited the same spot and was happy to share his observations. Many participants told stories about micro life at their locations, such as a beetle, a spider or a bee, each engaged in various activities. Others formed connections and even attachments to specific beings, such as a tree or place. Some observed the effects of the wind on everything around them.

Zoë-memories

In a third experiment, participants gather around a fire, a waterhole or something else. They are asked to silently go back in their memory and find an encounter from their life, perhaps from early childhood, where a particular other-than-human living being was significant. These can be termed zoë-memories (Paulsen, Reference Paulsen2022).Footnote 8 Before participants begin, examples are provided: it might be a cherished place, a tree from their childhood, or a moment when they encountered a fox on a foggy summer morning, recognising that the fox sees them seeing it, thus creating a shared gaze. Bron Taylor (Reference Taylor2009) refers to these moments as eye-to-eye epiphanies, where one may realise the irreplaceability of that other living being.

After five to ten minutes, participants are invited to share their zoë-memories. Through the sharing, it becomes evident that more-than-human life matters to us in various ways. Some recount experiences they had forgotten. Others connect their zoë-memories to challenging phases in their lives, such as coping with the loss of a parent. This demonstrates that human life is not as disconnected from more-than-human life as it might seem. Sitting around a fire appears to encourage deeper memories, while in the variation where we sat by the waterhole, many water-related memories surfaced. This suggest that our memories are influenced by the living context.

Discussion of minor experiences

Experiments with minor experiences seem to foster momentary life communities and what the educational researcher Mathilda Brückner calls collective glowing moments and living we-stories (Brückner, Reference Brückner, Lysgaard, Reid and Elf2025). Like in the poems shared by Riccardo and Marco in practice # 1 and the propositions created and enacted by Ingvild and Veslemøy, minor experiences facilitate moments of wonder, life-friendly attunement and micro-care. Sharing minor experiences, building trust and courage, finding the words to express shared feelings, and creating space for vulnerable conversations about what matters — how we relate to the world — appears to cultivate life-friendly and life-caring communities that include both humans and more-than-humans. Through consistent engagement with onto-sympathies, doing-nothing and zoë-memories, this may gradually give rise to what Bennett describes as a kaleidoscopic shift in everything we see, hear, smell, touch, taste and think (Bennett, Reference Bennett2017a).

However, these experiments also highlight the potential for regressions. If minor experiences are viewed merely as brief respites from modern life — escapist excursions into nature — they might reinforce the modern compensatory response and the nature-culture divide, contributing to romanticisation. To counter this, one could focus the search for onto-sympathies, doing-nothing and zoë-memories on deconstructing such artificial divisions. Onto-sympathies can arise from encounters with all vibrant materialities, and doing-nothing is a mode of being applicable in any context. To avoid regression towards the compensatory response, we might also adjust the timeframe. Instead of brief doing-nothing exercises (e.g., 15 minutes), we could incorporate wuwei strategies within longer-term educational initiatives. An example might be digging waterholes in human-damaged landscapes and then observing how the living world itself may re-habituate and heal the area (see photo below). The same can be said about PBW: if it remains an episodic initiative and not a part of ordinary schooling, its educational meaning could be misinterpreted as a compensatory response.

Another example could involve allowing more-than-human life the opportunity each day to act pedagogically first, setting the stage for what we will explore and learn with and from it (Blenkinsop & Kuchta, Reference Blenkinsop and Kuchta2024). When sharing zoë-memories, a different approach could be to focus on memories where more-than-human life is significant, but not necessarily in a romanticised way. For instance, Val Plumwood (Reference Plumwood2012) recounts her memory of nearly being eaten by a crocodile. What would happen if we began the search for zoë-memories with such examples?

Furthermore, these experiments might elicit critical-disillusioned responses. For example, we might find that what appears to be pristine nature is, in fact, a colonised or human-managed environment (Blenkinsop & Kuchta, Reference Blenkinsop and Kuchta2024). This underscores the importance of decolonising practices while cautioning against an overly critical stance that overlooks the enduring presence of life beyond human control.

Finally, across all three experiments and also in PBW practice, we observed a dynamic interplay between collective gathering, individual engagement with the environment, and subsequent sharing. This cyclical process reflects the rhythms of life — breathing, the heartbeat, a dance between singularities and the wider living world.

Conclusion: Life-friendly twisting-with-more-than-humans as a diffracted way forward or a thousand minor side steps?

In this article we have tried to show and discuss numerous ways that life-friendly practices can open opportunities to come to know, understand and care for the world around us. More specifically, we have described three sets of arts educational practices and encounters with the more-than-human world that go beyond contemporary, standard, mainstream classroom teaching and education (Anundsen et al., Reference Anundsen, Illeris, Østern and Knudsen2019; Roy, Reference Roy2003). Of course, other activities and experiments might also transcend these bounds. Likewise, all three could regress into mainstream formats of classroom teaching. What we find important is that the framing around minor experiences, propositions and nature poetry writings can be twisted — in partnership and inspired by more-than-humans — in multiple, infinite ways that allow for degrees of divergence from mainstream education. What matters is that such twisting — when approached cautiously (Paulsen, Reference Paulsen, Petersen, von Brömssen, Jacobsen, Garsdal, Paulsen and Koefoed2022b, Reference Paulsen2023) — might create opportunities for imagining and experiencing life-friendly comportments, where life is opened up, and the world may then become wondrous, loveable and something we care for (Bennett, Reference Bennett2001). As demonstrated, the three arts educational responses outlined in the article can be used as a first step to elaborate on important “vectors of twisting” towards life-friendly comportments: If, for instance, a practice turns out to only respond in a modern-compensatory way, one might work out how the practice can be twisted towards a critical-disillusional and even life-opening way, to become more life-friendly by fully including more-than-human perspectives, voices and possibilities of participation.

Thus, as authors of this paper, we feel that what has been genuinely opened up for us by putting our arts educational practices together, in dialogue with each other and the more-than-human world, is a meta-awareness of opportunities for speculative twisting-with-more-than-humans. What matters is not just to carry out education through nature writing, propositions and minor experiences. What matters is to co-develop practices where playful twisting-together-with-more-than-humans becomes possible, allowed and intended, in ways that might be life-friendly. That said, we acknowledge that we have only sketched “twisting” as something that could use further research: what does it mean, more precisely? How can it be conducted in multiple ways, together with more-than-humans? And with what benefits could it be developed methodologically?

The three responses we have outlined at the start of this paper might help to clarify, nuance and work with such twisting and considerations along the way. In that sense, it might be helpful to think of rewilding educational practice as an ongoing experiment about how much twisting-together-with-more-than-humans is actually possible, and how much the practice allows for the opening up of life for the participants engaged in doing so in life-friendly ways. Thus, the practices we have considered in the paper might function as inspiration for how to rewild pedagogical life further and differently, where one embraces the idea of continuing with twisting nature writing, propositions, and minor experiences and/or other play spaces (Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Reference Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles2022). However, it can also mean beginning to or continuing to twist one’s own and other existing practices in diverse directions, aiming to open them up for life, and in each step, considering whether other twists and turns might also be needed to liberate life and become a friend to life, understood as an infinite desire and process rather than as an end result or state of being.

Figure 1. Place-based writing, individual and group sessions. Italy 2022.

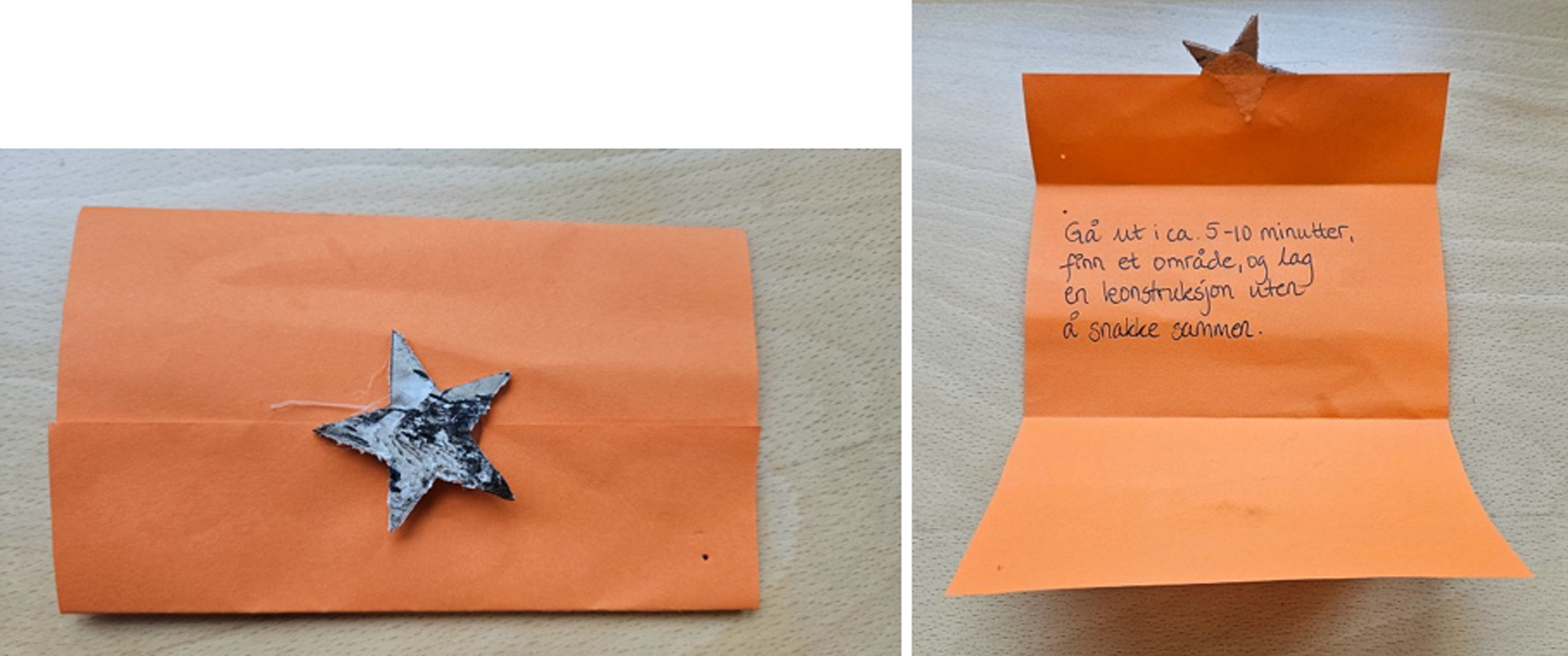

Figure 2. Example of how a proposition was handed over to other students — like a letter with no further explanations. (Translated into English, the proposition reads “Go outside for ca. 5-10 minutes. Find a site and make a construction without talking to each other”).

Figure 3. Found object hidden, discovered and removed. Pictures by Ingvild Haugen and Veslemøy Olsen.

Figure 4. Participants searching for onto-sympathies, at Himmelbjerget in Denmark, 2024.

Figure 5. Stone. Photo and words by Helene Waage, Norway, 2022.

Figure 6. A participant finding a position to “do nothing” from. Italy 2024.

Figure 7. Sharing life experiences, Italy, 2024 and Norway, 2022.

Figure 8. A rewilding project, Milesov, the Czech Republic, an area eco-damaged in the The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics occupation era.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to our students and other participants who took part in our experimental practices and willingly shared their experiences and visual material with us for this article.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit.

Ethical standards

Nothing to note.

Author Biographies

Michael Paulsen Associate Professor in Pedagogy and head of CUHRE (Centre for Understanding Human Relationship with the Environment), at the University of Southern Denmark. Author and editor of several books and special issues. He holds a Ph.D. in Social Philosophy. Currently he is working on a pedagogical theory of life-friendly education situated in the Anthropocene. Together with Linda Wilhelmsson, he co-organised the international Wild Pedagogies conference Nature as Co-teacher in Enaforsholm, in August 2023. See https://portal.findresearcher.sdu.dk/en/persons/mpaulsen.

Helene Illeris is PhD and Professor of Art Education at the University of Agder, Norway. Her research interests comprise contemporary art in education, aesthetic learning Helene is a co-leader of the research group Arts and Social relations. She has published more than 50 books, chapters, and articles in English, Danish, Swedish, and Italian, comprising chapters in the anthologies Pedagogy of the Anthropocene (Paulsen et al., 2022), Expanding Environmental Awareness in Education Through the Arts (Fredriksen & Groth, 2023), and Pedagogical Propositions: Playful Walking with A/r/tography. Book One: Encounters (Lee et. al, 2024).

Tommaso Reato, Phd in Educational Sciences at the University of Padua where he teaches as adjunct professor. His interest area is school based outdoor education, with a focus on adolescence and art based languages. He also works as an educator and trainer.