Introduction

In organizational research, self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017) has emerged as one of the most comprehensive frameworks for explaining employees' wellbeing. A central tenet of SDT is that satisfaction of basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) is required for high-quality motivation (self-directed behaviors) and healthy functioning at work. Recent meta-analyses gather considerable research support for this assumption, revealing that both basic need satisfaction at work (Van den Broeck, Ferris, Chang, & Rosen, Reference Van den Broeck, Ferris, Chang and Rosen2016) and autonomous forms of work motivation (Van den Broeck, Howard, Van Vaerenbergh, Leroy, & Gagné, Reference Van den Broeck, Howard, Van Vaerenbergh, Leroy and Gagné2021) are associated with key indicators of employees' wellbeing (e.g., work engagement, lower burnout), including adaptive job attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction, lower turnover intentions) and behaviors (e.g., task performance, lower absenteeism).

Although research provides valuable insights into the fundamental roles of need satisfaction and motivation at work, scholars have not yet jointly considered the multidimensionality of these two constructs. More precisely, they have generally ignored the distinctive role played by global (i.e., overall levels of need satisfaction or work motivation reported across all indicators) and specific (i.e., the extent to which scores obtained on the specific dimensions of need satisfaction or motivation deviate, or tap into something unique, beyond these global levels) components of these constructs in relation to wellbeing.

From a theoretical perspective, distinguishing the global and specific aspects of both need satisfaction and work motivation provides important information regarding the unique importance of each specific component of both constructs beyond what all components share with one another. For example, a study using a traditional operationalization of need satisfaction might report similar associations between the needs for competence and relatedness and one specific outcome variable, but a lack of association between the need for autonomy and the same outcome. However, knowing that the satisfaction of all three needs is highly correlated, this conclusion might simply reflect the fact that the explanatory power of autonomy need satisfaction overlaps entirely with that of the other needs, rather than a true lack of effect of autonomy. In contrast, a study relying on a proper disaggregation of global and specific levels of need satisfaction might rather indicate that the key driver of scores on the outcome variable is the global levels of need satisfaction shared across all three needs (thus supporting the idea that all three needs are important), with some additional positive effects associated with participants' specific levels of relatedness satisfaction (supporting the idea that these needs play an additional role beyond what it shares with the others). This interpretation is consistent with Gillet, Morin, Choisay, and Fouquereau's (Reference Gillet, Morin, Choisay and Fouquereau2019, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2020a; also see Sheldon & Niemiec, Reference Sheldon and Niemiec2006) theoretical proposition that the core driver of positive functioning and wellbeing was the extent to which all three needs were satisfied (i.e., as captured by the global level of need satisfaction), whereas they noted that the extent to which each specific need was satisfied beyond this global level should rather be considered to reflect an imbalance in the satisfaction of all three needs.

The same reasoning applies to multidimensional ratings of motivation, which have long been assumed by SDT (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2008; Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017) to follow a continuum of self-determination, ranging from the most self-determined types of motivation to the least self-determined ones. Based on a review of SDT research evidence related to this motivational continuum, Howard, Gagné, and Morin (Reference Howard, Gagné and Morin2020) recently concluded that motivation seems to be best represented by a semi-radex structure. More precisely, they indicated that an optimal representation of motivation, from the perspective of SDT, would require the dual consideration of participants' global levels of self-determination (reflecting their global position on this continuum), while also considering the extent to which participants' specific motives to engage in an activity might deviate from this global continuum. Importantly, from a statistical and measurement perspective, research has demonstrated that failing to account for the dual global and specific nature of complex multidimensional constructs tends to lead to biased estimates of associations with other constructs (Asparouhov, Muthén, & Morin, Reference Asparouhov, Muthén and Morin2015; Mai, Zhang, & Wen, Reference Mai, Zhang and Wen2018; Morin, Arens, & Marsh, Reference Morin, Arens and Marsh2016).

For these reasons, a comprehensive theoretical understanding of the role played by need satisfaction and motivation for wellbeing should consider whether and how employees' wellbeing can be attributed to global and/or specific components of both constructs. Therefore, this study examines the associations between global and specific levels of psychological need satisfaction and work motivation in the prediction of occupational wellbeing, assuming that these variables will form a mediation system. More precisely, we expect need satisfaction to predict self-determined forms of work motivation which, in turn, are expected to predict higher levels of wellbeing. In doing so, the present study thus provides a further test of Gillet et al.'s (Reference Gillet, Morin, Choisay and Fouquereau2019, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2020a) and Howard, Gagné, and Morin's (Reference Howard, Gagné and Morin2020) recent propositions regarding the structure of need satisfaction and motivation, while providing the first investigation of the interrelations between both constructs and components of employees' wellbeing conducted by relying on a proper disaggregation of their dual global/specific nature. This research should also provide guidance to practitioners in devising tailored interventions to help nurture wellbeing at work by highlighting whether it is more important to focus on nurturing global levels of need satisfaction and self-determination rather than focusing on nurturing specific types of motivations or specific needs. By capturing the role played by the unique nature of each need and motivation type beyond what they share with the others, this study also has the potential to highlight possible risks associated with imbalanced levels of need satisfaction or motivational styles dominated by specific types of motives.

Motivation

SDT differentiates distinct types of work motivation organized along a continuum of self-determination (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2008; Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017). Intrinsic motivation is the most self-determined type of motivation. Individuals who are intrinsically motivated work for the interest and enjoyment that they derive from work activities seen as inherently rewarding. Next on the continuum, identified regulation occurs when work activities align with employees' personal values, leading them to view these activities as important and meaningful. In contrast, introjected regulation occurs when work involvement is driven by internal pressures, including the pursuit of self-esteem and pride, as well as the avoidance of guilt. Then, external regulation occurs when work activities are driven externally, such as to obtain material or social rewards, or to avoid undesirable consequences. Finally, amotivation refers to the complete absence of motivation or intention. SDT typically groups intrinsic motivation and identified regulation under the label of ‘autonomous motivation’ because they both denote involvement in an activity that is mainly driven by a personal endorsement (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2008). In contrast, introjected and external regulation are typically referred to as ‘controlled motivation’ because they involve external or internal pressures that remain disconnected from personal desires or core values. As noted, these motives are expected to be organized along a single overarching continuum of self-determination, reflecting individuals' global sense of volition and self-directedness (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017).

SDT posits that more autonomous forms of motivation are more likely to cultivate satisfaction, performance, and wellbeing relative to more controlled forms of motivation or to amotivation, which should rather be associated with higher levels of burnout and turnover intentions (Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017). Indeed, research has shown that, when facing high job demands (such as role ambiguity, role overload, and role conflict), more autonomously driven employees were less likely to find these demands overwhelming, and thus more likely to address them efficiently (Trépanier, Fernet, & Austin, Reference Trépanier, Fernet and Austin2013). Likewise, autonomously motivated employees have been found to derive pleasure and satisfaction from their work, and to feel that their work aligns more with their personal interests (Fernet, Trépanier, Demers, & Austin, Reference Fernet, Trépanier, Demers and Austin2017). In contrast, employees who work for more controlled reasons tend to feel pressured to work and to focus on external gratifications to escape negative feelings (Fernet et al., Reference Fernet, Trépanier, Demers and Austin2017). As a result, working for more autonomous reasons has been found to be associated with higher levels of psychological engagement at work, fewer absences, and lower turnover intentions, whereas the opposite relations have generally been reported for controlled motivations (Austin, Fernet, Trépanier, & Lavoie-Tremblay, Reference Austin, Fernet, Trépanier and Lavoie-Tremblay2020; Fernet et al., Reference Fernet, Trépanier, Demers and Austin2017).

Apart from the autonomous-controlled distinction, some studies (e.g., Howard, Gagné, Morin, & Forest, Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018) have also highlighted the value of considering a direct estimate of employees' global levels of self-determined work motivation via the application of bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling (bifactor-ESEM; Morin, Arens, & Marsh, Reference Morin, Arens and Marsh2016, Reference Morin, Myers, Lee, Tenenbaum and Eklund2020). This analytic approach explicitly disaggregates employees' global levels of self-determined work motivation (defined by their ratings obtained across all types of work motivation), from the unique nature of each specific type of work motivation left unexplained by this global level (Howard, Gagné, & Morin, Reference Howard, Gagné and Morin2020). Furthermore, this approach makes it possible to achieve this disaggregation while accounting for the normative degree of overlap that typically occurs when multiple conceptually related constructs are assessed within the same instrument thus resulting in a more accurate estimation of the factors (Asparouhov, Muthén, & Morin, Reference Asparouhov, Muthén and Morin2015; Morin, Arens, & Marsh, Reference Morin, Arens and Marsh2016, Reference Morin, Myers, Lee, Tenenbaum and Eklund2020). Importantly, these studies were able to estimate a global self-determination factor that perfectly matched SDT's continuum hypothesis. More precisely, this global factor was defined by strong positive loadings from intrinsic motivation items, moderate positive loadings from identified regulation items, smaller positive loadings from introjected regulation items, null or negative loadings from the external regulation items, and stronger negative loadings from the amotivation items (work: Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018; education: Litalien, Morin, Gagné, Vallerand, Losier, & Ryan, Reference Litalien, Morin, Gagné, Vallerand, Losier and Ryan2017).

Studies relying on bifactor-ESEM have generally demonstrated that this global self-determination factor presented the strongest association with a variety of outcomes (e.g., Fernet et al., Reference Fernet, Litalien, Morin, Austin, Gagné, Lavoie-Tremblay and Forest2020; Gillet, Morin, Ndiaye, Colombat, & Fouquereau, Reference Gillet, Morin, Ndiaye, Colombat and Fouquereau2020c; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018; Tóth-Király, Morin, Bőthe, Rigó, & Orosz, Reference Tóth-Király, Morin, Bőthe, Rigó and Orosz2021). More specifically, this global factor was found to be positively associated with affective commitment as well as with the satisfaction of the needs for autonomy, relatedness, competence (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018), proactivity and adaptivity (Howard, Morin, & Gagné, Reference Howard, Morin and Gagné2021), perceived organizational support (Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Morin, Ndiaye, Colombat and Fouquereau2020c), work satisfaction (Tóth-Király et al., Reference Tóth-Király, Morin, Bőthe, Rigó and Orosz2021), and in-role performance (Fernet et al., Reference Fernet, Litalien, Morin, Austin, Gagné, Lavoie-Tremblay and Forest2020). However, these studies also showed that these associations could not be entirely subsumed under this global self-determination factor, so that the specific motivation factors remained able to explain meaningful outcome variance over and above the variance explained by the global factor. These results thus reinforce the importance of accounting for both the global and specific nature of work motivation with respect to work-related outcomes (e.g., Howard, Gagné, & Morin, Reference Howard, Gagné and Morin2020).

Basic psychological need satisfaction

According to SDT (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2008), every human, irrespective of age, culture, or situation, seeks the fulfillment of three basic psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence. These needs are positioned by SDT as the core drivers of self-determination and wellbeing. Relatedness refers to the need to feel a sense of connection and belonging in relation to other members of one's social environment. Competence reflects the need to feel a sense of mastery and accomplishment. Autonomy refers to a sense of volition in one's actions. These three needs have been shown to be universal, and their satisfaction has been found to be associated with a variety of desirable outcomes across multiple life domains, including education (Ratelle & Duchesne, Reference Ratelle and Duchesne2014), sports (Gunnell, Crocker, Mack, Wilson, & Zumbo, Reference Gunnell, Crocker, Mack, Wilson and Zumbo2014), and work (Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017; Gagné & Deci, Reference Gagné and Deci2005). In work settings, need satisfaction has been shown to predict higher levels of job performance and psychological adjustment (Baard, Deci, & Ryan, Reference Baard, Deci and Ryan2004), to enhance vitality (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2008) and employees' affective commitment to their organizations (Greguras & Diefendorff, Reference Greguras and Diefendorff2009), and to help nurture more autonomous forms of work motivation (Dysvik, Kuvaas, & Gagné, Reference Dysvik, Kuvaas and Gagné2013). In contrast, when need satisfaction is thwarted by a controlling social environment, individuals are expected to lean toward extrinsically motivated tasks (Trépanier, Forest, Fernet, & Austin, Reference Trépanier, Forest, Fernet and Austin2015). Deci, Olafsen, and Ryan (Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017) thus suggest that employers seeking to improve their work environment and to motivate employees should implement measures that help nurture need satisfaction, such as by nurturing respect and positive social interactions, supporting employees' sense of confidence and ability, and encouraging initiative. According to SDT, such practices should foster autonomous forms of motivation, wellbeing, and work performance.

When looking at the three basic psychological needs separately, research has also revealed that work conditions able to support the satisfaction of each of these needs played a positive role in driving workplace motivation and wellbeing. In relation to relatedness, a longitudinal study showed that a lack of social support from supervisors and colleagues was associated with increased levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and with decreased levels of personal accomplishment 1 year later (Van der Ploeg & Kleber, Reference Van der Ploeg and Kleber2003). Likewise, exposure to interpersonal conflicts was found to be positively associated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and negatively associated with personal accomplishment (García-Izquierdo & Ríos-Rísquez, Reference García-Izquierdo and Ríos-Rísquez2012). Finally, teamwork and collaboration with physicians were found to be related to lower levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization among nurses (O'Mahony, Reference O'Mahony2011), whereas the frequency and quality of nurses' communications with their managers, as well as their sense of group cohesion, were found to decrease job stress and turnover intentions while increasing job satisfaction (Boyle, Bott, Hansen, Woods, & Taunton, Reference Boyle, Bott, Hansen, Woods and Taunton1999; Mealer, Burnham, Goode, Rothbaum, & Moss, Reference Mealer, Burnham, Goode, Rothbaum and Moss2009).

Although research focusing more specifically on the needs for competence and autonomy satisfaction is scarcer than research focusing on relatedness satisfaction, results are generally similar. Thus, individuals low in personal accomplishment (i.e., competence) have been found to experience more feelings of inefficacy, which can in turn decrease the efforts that they expend at work and increase their turnover intentions (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997). Likewise, nurses higher in perceived competence tend to be more resilient to job demands, and thus tend to persist longer in their job (Boudrias, Trépanier, Foucreault, Peterson, & Fernet, Reference Boudrias, Trépanier, Foucreault, Peterson and Fernet2020). In relation to autonomy, Browning, Ryan, Thomas, Greenberg, and Rolniak (Reference Browning, Ryan, Thomas, Greenberg and Rolniak2007) found that emergency nurses tended to report higher levels of emotional exhaustion than other nurses as a result of their reduced level of control over their work environment, resulting from their exposure to more frequent work-related of stressors. Likewise, a lack of autonomy was found to longitudinally predict higher levels of emotional exhaustion and a lower sense of personal accomplishment 1 year later (Van der Ploeg & Kleber, Reference Van der Ploeg and Kleber2003). Similarly, Moreau and Mageau (Reference Moreau and Mageau2012) found that individuals who receive autonomy support from their superiors and colleagues tend to report higher levels of work satisfaction and psychological wellbeing. In fact, nurses' perception of autonomy and control were found to directly influence workplace trust and work satisfaction (Laschinger, Shamian, & Thomson, Reference Laschinger, Shamian and Thomson2001) and turnover intentions (Boudrias et al., Reference Boudrias, Trépanier, Foucreault, Peterson and Fernet2020; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, O'Brien-Pallas, Duffield, Shamian, Buchan, Hughes and Stone2006).

More generally, studies have shown that global levels of need satisfaction were important predictors of a variety of work-related outcomes, while also supporting the presence of well-differentiated relations between each specific need and these outcomes, and thus supporting the distinctive nature of each need. This consideration is important for the measurement of need satisfaction and has led to the observation that, similar to work motivation, it is important to simultaneously account for global and specific levels of need satisfaction via bifactor-ESEM analyses (Morin, Arens, & Marsh, Reference Morin, Arens and Marsh2016, Reference Morin, Myers, Lee, Tenenbaum and Eklund2020). Emerging research has provided strong support for this assertion (e.g., Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Morin, Choisay and Fouquereau2019, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2020a, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huyghebaert-Zouagh, Alibran, Barrault and Vanhove-Meriaux2020b; Sánchez-Oliva, Morin, Teixeira, Carraça, Palmeira, & Silva, Reference Sánchez-Oliva, Morin, Teixeira, Carraça, Palmeira and Silva2017; Tóth-Király, Bőthe, Orosz, & Rigó, Reference Tóth-Király, Bőthe, Orosz and Rigó2019), showing that need satisfaction can be separated into global levels of need satisfaction and specific levels of autonomy, competence, and relatedness left unexplained by these global levels. This second, specific, component is generally interpreted as reflecting an imbalanced level (i.e., deviations) in the satisfaction of each need relative to these global levels (Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Morin, Choisay and Fouquereau2019, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2020a, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huyghebaert-Zouagh, Alibran, Barrault and Vanhove-Meriaux2020b). These studies have also demonstrated that global levels of need satisfaction tended to be associated with, for instance, students' interests in, and satisfaction with, their studies (Gillet, Morin, Huyghebaert-Zouagh, Alibran, Barrault, & Vanhove-Meriaux, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huyghebaert-Zouagh, Alibran, Barrault and Vanhove-Meriaux2020b), lower levels of burnout (Sánchez-Oliva et al., Reference Sánchez-Oliva, Morin, Teixeira, Carraça, Palmeira and Silva2017), higher levels of positive affect and lower levels of negative affect (Tóth-Király et al., Reference Tóth-Király, Bőthe, Orosz and Rigó2019), and higher levels of perceived organizational support and psychological wellbeing (i.e., higher levels of work engagement, positive affect, job satisfaction, and citizenship behaviors, and lower levels of burnout; Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat, & Fouquereau, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2020a). In addition, the specific need satisfaction factors have also been shown to explain additional outcome variance beyond that explained by the global factor, highlighting the importance of taking both the global and the specific components into account.

Workplace wellbeing outcomes

The present study specifically focuses on burnout, work satisfaction, and turnover intentions as indicators of wellbeing, given that these dimensions represent significant concerns for many occupations including nursing (Adriaenssens, De Gucht, & Maes, Reference Adriaenssens, De Gucht and Maes2015; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, O’Brien-Pallas, Duffield, Shamian, Buchan, Hughes and North2012). Burnout is typically assumed to result from exposure to chronic work stressors (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter2001; Shirom & Melamed, Reference Shirom and Melamed2006) and is known to carry a heavy burden for organizations and employees alike (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter2001). Burnout represents a work-related state of low energy and unpleasant affect encompassing attitudinal (i.e., cynicism, reflecting callousness, or detachment from one's job), emotional (i.e., emotional exhaustion, reflecting feelings of being worn-out, and drained of one's psychological and emotional resources), and behavioral (i.e., professional inefficacy, reflecting feelings of incompetence, and lack of accomplishment) manifestations (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter2001). In this study, we focus on emotional exhaustion, which represents the core component of burnout (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter2001; Schonfeld & Bianchi, Reference Schonfeld and Bianchi2016).

Contrasting with burnout, work satisfaction reflects a positive manifestation of wellbeing at work (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2001), referring to a sense of fulfillment and gratification derived from work (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter2001). In organizational research, work satisfaction has received attention for providing an important source of information on employees' occupational wellbeing (Faragher, Cass, & Cooper, Reference Faragher, Cass and Cooper2005; Judge, Thoresen, Bono, & Patton, Reference Judge, Thoresen, Bono and Patton2001).

Finally, turnover intentions, defined as employees' intentions to leave their job, are generally positioned as a core component of work dissatisfaction known to carry a high cost for organizations given its strong links with voluntary turnover (Rubenstein, Eberly, Lee, & Mitchell, Reference Rubenstein, Eberly, Lee and Mitchell2018). Generally, previous research anchored in SDT has supported the connection between all of these components of employees' psychological wellbeing at work, their work motivation, and the degree to which their psychological needs are satisfied in their workplaces (Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017; Van den Broeck et al., Reference Van den Broeck, Ferris, Chang and Rosen2016, Reference Van den Broeck, Howard, Van Vaerenbergh, Leroy and Gagné2021).

SDT's motivation mediation model

Apart from highlighting the importance of need satisfaction and work motivation, SDT research also proposes that these psychological factors form a motivation mediation model (Jang, Kim, & Reeve, Reference Jang, Kim and Reeve2012; Olafsen, Deci, & Halvari, Reference Olafsen, Deci and Halvari2018) in which need satisfaction is assumed to predict work motivation, which in turn is assumed to predict wellbeing outcomes. Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2017) argued that fulfilling employees' psychological needs promotes better internalization and integration processes, leading to the development of more autonomous forms of motivation and, as a result, to improved wellbeing. Even though prior research has found support for this motivation mediation model in different contexts (e.g., Garn, Morin, & Lonsdale, Reference Garn, Morin and Lonsdale2019; Jang, Kim, & Reeve, Reference Jang, Kim and Reeve2012), including work (Olafsen, Deci, & Halvari, Reference Olafsen, Deci and Halvari2018), none of these studies have simultaneously considered the global/specific levels of need satisfaction and work motivation at the same time.

The present study

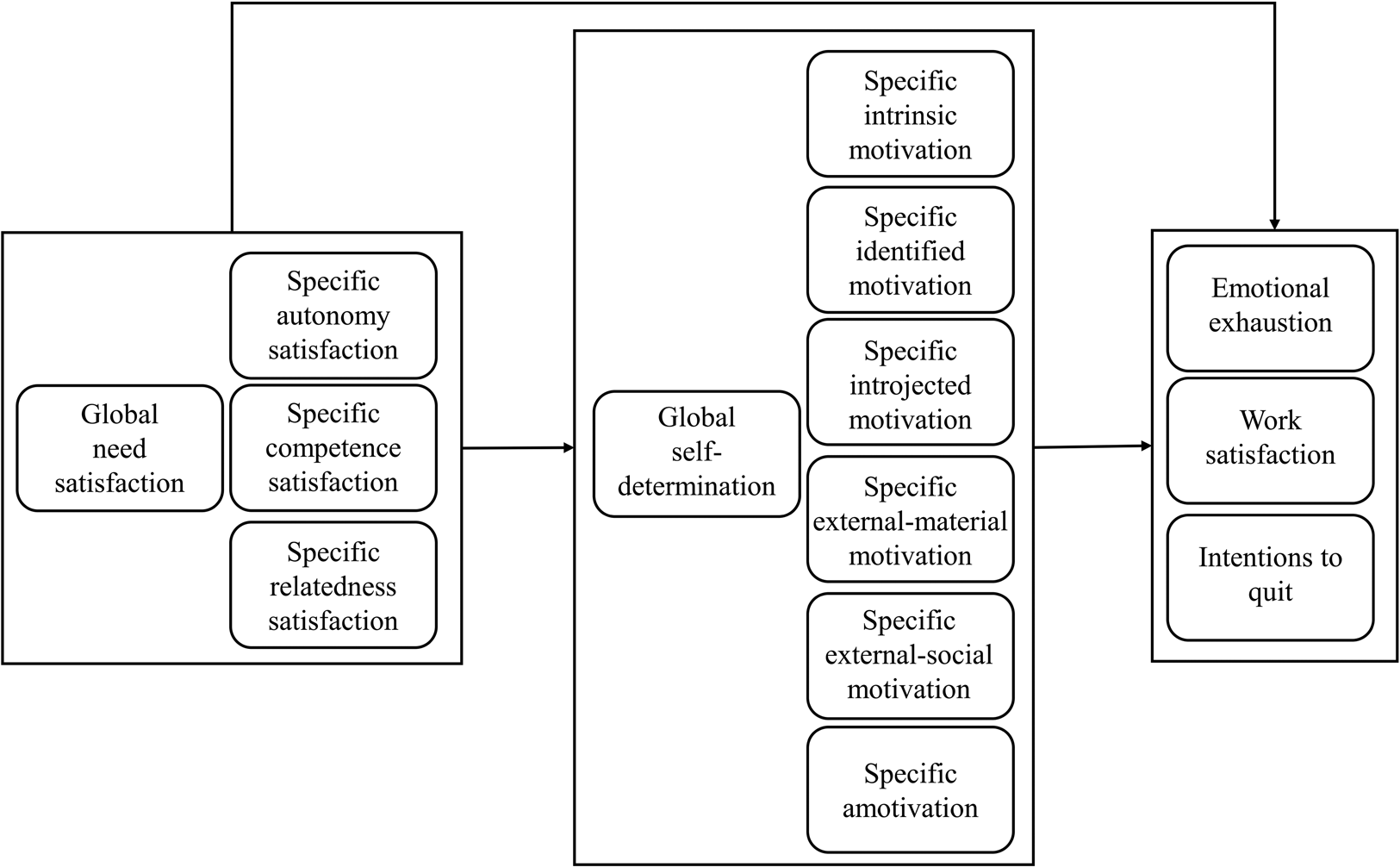

This study seeks to examine the associations between need satisfaction, work motivation, and workplace wellbeing outcomes, while assessing the role of work motivation as a mediator of the association between need satisfaction and the wellbeing outcomes proposed by SDT (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017). Given the multidimensionality of work motivation and need satisfaction, we will first examine their measurement structure to achieve a more accurate picture of the role of their global and specific components in these various associations. Based on previous research, we expected the bifactor-ESEM solution to provide the most accurate representation of employees' ratings of work motivation (hypothesis 1a) and need satisfaction (hypothesis 2). For ratings of work motivation, we also expected the global factor to be associated with a factor loading pattern corresponding to the SDT continuum hypothesis (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018; Litalien et al., Reference Litalien, Morin, Gagné, Vallerand, Losier and Ryan2017) (hypothesis 1b): strong positive loadings for the intrinsic motivation items, moderate positive loadings for the identified regulation items, smaller positive loadings for the introjected regulation items, null or negative loadings for the external regulation items, and stronger negative loadings for the amotivation items. In relation to our theoretical (predictive) model, illustrated in Figure 1, we first expect global levels of need satisfaction and specific levels of relatedness, competence, and autonomy need satisfaction to be associated with higher global levels of self-determination and specific levels on the autonomous forms of motivation (hypothesis 3). In turn, we expect global levels of self-determination and specific levels on the autonomous forms of motivation to be associated with more desirable outcome levels (hypothesis 4a), whereas we expect specific levels on the controlled forms of motivation to be associated with less desirable outcome levels (low levels of work satisfaction, high levels of burnout and turnover intentions) (hypothesis 4b). Furthermore, we also expect global levels of need satisfaction and specific levels of relatedness, competence, and autonomy satisfaction to be associated with more desirable outcomes (higher levels of work satisfaction, lower levels of burnout and turnover intentions) (hypothesis 5). Finally, we expect work motivation to mediate the relations between need satisfaction and the outcomes (hypothesis 6).

Figure 1. Hypothesized path model.

Note. Rectangles with rounded corners represent factor scores saved from preliminary measurement models. Directional arrows represent regression paths. Variables in boxes belong to the same theoretical set (i.e., predictors, mediators, outcomes).

Method

Participants and procedures

The participants of this study were French-Canadian registered nurses working in the public healthcare sector and members of the Quebec Nursing Association (Ordre des infirmières et des infirmiers du Québec). They were recruited in 2014 via a letter sent to their home address describing the purpose of the study and inviting them to participate by completing an online questionnaire. The letter guaranteed the anonymity of responses and indicated that participation was voluntary. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. An informed consent form was signed by all participants who answered the questionnaire.

The final sample includes 708 French-Canadian nurses (87.7% females) working in the Quebec public healthcare system and aged between 20 and 52 years (M = 27.00, sd = 6.82). Participants had an average of 2.06 years of experience in the nursing profession (sd = 1.44), and most of them held permanent positions (77.5%). Of those, 44.2% worked full-time, whereas 55.8% worked part-time. Additionally, 15.6% worked day shifts, 34.9% worked evening shifts, 23.6% worked night shifts, and 25.9% reported working shifts at varying times of the day.

Materials

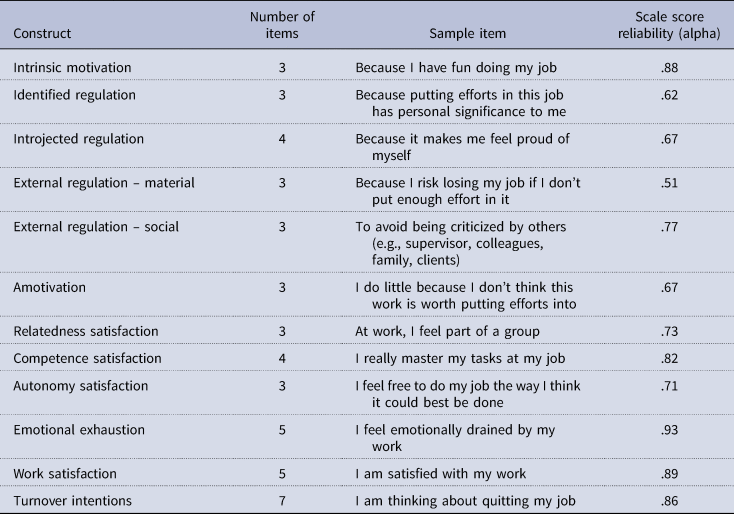

Participants completed the questionnaires in French, using versions validated in this language. Sample items and scale score reliabilities (Cronbach's alpha) are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive information on the questionnaires

Work motivation

The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (original French version by Gagné, Forest, Vansteenkiste, Crevier-Braud, & Van den Brock, Reference Gagné, Forest, Vansteenkiste, Crevier-Braud and Van den Brock2015) includes 19 items measuring the motives behind individuals' effort expenditure at work. Items started with the stem ‘Why do you put effort into your current job?’ and participants responded using a rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely).

Need satisfaction

The Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction Scale (Van den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, De Witte, Soenens, & Lens, Reference Van den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, De Witte, Soenens and Lens2010; French version by Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2020a) includes 10 items assessing the satisfaction of participants needs. Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree).

Burnout

The emotional exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory – General Survey (Schaufeli, Leiter, Maslach, & Jackson, Reference Schaufeli, Leiter, Maslach, Jackson, Maslach, Jackson and Leiter1996; French adaptation by Fernet, Lavigne, Vallerand, & Austin, Reference Fernet, Lavigne, Vallerand and Austin2014) was used to assess burnout. The participants responded using a rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (every day).

Work satisfaction

An adapted version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985; French version by Bouizegarene, Bourdeau, Leduc, Gousse-Lessard, Houlfort, & Vallerand, Reference Bouizegarene, Bourdeau, Leduc, Gousse-Lessard, Houlfort and Vallerand2018) was used to measure participants’ satisfaction with their work by replacing the word ‘life’ with the word ‘work.’ Participants responded using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Turnover intentions

A scale adapted from O'Driscoll and Beehr's (Reference O'Driscoll and Beehr1994; French version by Fernet, Trépanier, Austin, Gagné, & Forest, Reference Fernet, Trépanier, Austin, Gagné and Forest2015) scale was administered to participants to measure turnover intention. The participants responded using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2020) and the robust weighted least square estimator with mean- and variance-adjusted statistics (WLSMV in Mplus) due to our reliance on ordinal indicators following asymmetric response thresholds (Finney & DiStefano, Reference Finney, DiStefano, Hancock and Mueller2013). Missing data were handled using the algorithms implemented in Mplus for WLSMV estimation (Asparouhov & Muthén, Reference Asparouhov and Muthén2010), allowing us to retain all participants for all analyses (Enders, Reference Enders2010; Graham, Reference Graham2009). Following recent recommendations (e.g., Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018, Reference Howard, Gagné and Morin2020; Tóth-Király, Morin, Bőthe, Orosz, & Rigó, Reference Tóth-Király, Morin, Bőthe, Orosz and Rigó2018), we relied on the bifactor-ESEM analyses (Morin, Arens, & Marsh, Reference Morin, Arens and Marsh2016, Reference Morin, Myers, Lee, Tenenbaum and Eklund2020) to examine the underlying factor structure of the work motivation and need satisfaction measures. Details on these preliminary analyses are provided in Appendix 1 of the online Supplementary materials. Consistent with hypotheses 1a and 2, these results support the adequacy and composite reliability of the factors estimated as part of a bifactor-ESEM solution. For work motivation, the pattern of factor loadings on the global factor is consistent with the SDT motivation continuum, thus supporting hypothesis 1b.

Once the optimal solution was selected for each measure separately, factor scores were saved from these retained measurement models and combined into two predictive models. In the first model of partial mediation (including direct and indirect associations between need satisfaction and the outcomes), the work motivation and need satisfaction factors were used to predict all three outcomes, and the need satisfaction factors were also used to predict the work motivation factors. In the second model of full mediation (including only indirect associations between need satisfaction and the outcomes), the direct links between the need satisfaction factors and the wellbeing outcomes were removed to verify if the hypothesized predictive system can be considered to entirely occur via the mediating role of the work motivation factors. Finally, the statistical significance of the indirect effects (i.e., the product of the path linking a predictor to a mediator by the path linking that mediator and an outcome) were calculated using 95% bias-corrected bootstrap (5,000 bootstrap samples) confidence intervals (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams2004).

The adequacy of all models was evaluated using typical goodness-of-fit indices (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; Marsh, Hau, & Grayson, Reference Marsh, Hau, Grayson, Maydeu-Olivares and McArdle2005): the chi-square test (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values are considered to be adequate or excellent when they are above .90 and .95, respectively. RMSEA values are considered to be adequate or excellent below .08 and .06, respectively. As the χ2 test is known to be oversensitive to minor model misspecifications and sample size (Marsh, Hau, & Grayson, Reference Marsh, Hau, Grayson, Maydeu-Olivares and McArdle2005), it is simply reported for the sake of transparency, but not used in model evaluation. We also calculated model-based omega (ω) coefficients of composite reliability (McDonald, Reference McDonald1970) for each factor using the standardized parameter estimates form these measurement models (Morin, Myers, & Lee, Reference Morin, Myers, Lee, Tenenbaum and Eklund2020).

Results

Predictive models

Factor scores were saved from the bifactor-ESEM solution for work motivation and need satisfaction, and from the confirmatory factor analytic (CFA) solution for the wellbeing indicators. Factor scores have the advantage of preserving the nature of the measurement model (e.g., bifactor) and of maintaining partial control for unreliability (e.g., Morin et al., Reference Morin, Boudrias, Marsh, McInerney, Dagenais-Desmarais, Madore and Litalien2017; Skrondal & Laake, Reference Skrondal and Laake2001). They are also protected against the challenges posed by the prediction of bifactor factors in a predictive model (Koch, Holtmann, Bohn, & Eid, Reference Koch, Holtmann, Bohn and Eid2018).

Model fit for the partial mediation model was perfect (CFI = 1, TLI = 1, RMSEA = 0) as this model was just identified (i.e., all possible structural paths were estimated). The fit of the full mediation model was substantially worse (ΔCFI = −.093; ΔTLI = −.658; ΔRMSEA = +.119) and not acceptable according to the TLI and RMSEA, suggesting that taking out the direct paths resulted in an unsatisfactory model. The partial mediation model was thus retained for interpretation, a conclusion that is supported by the inspection of the regression estimates. This model is equivalent to any just identified multiple regression model, but allows us to test chains of associations involved in the theoretical motivation mediation model.

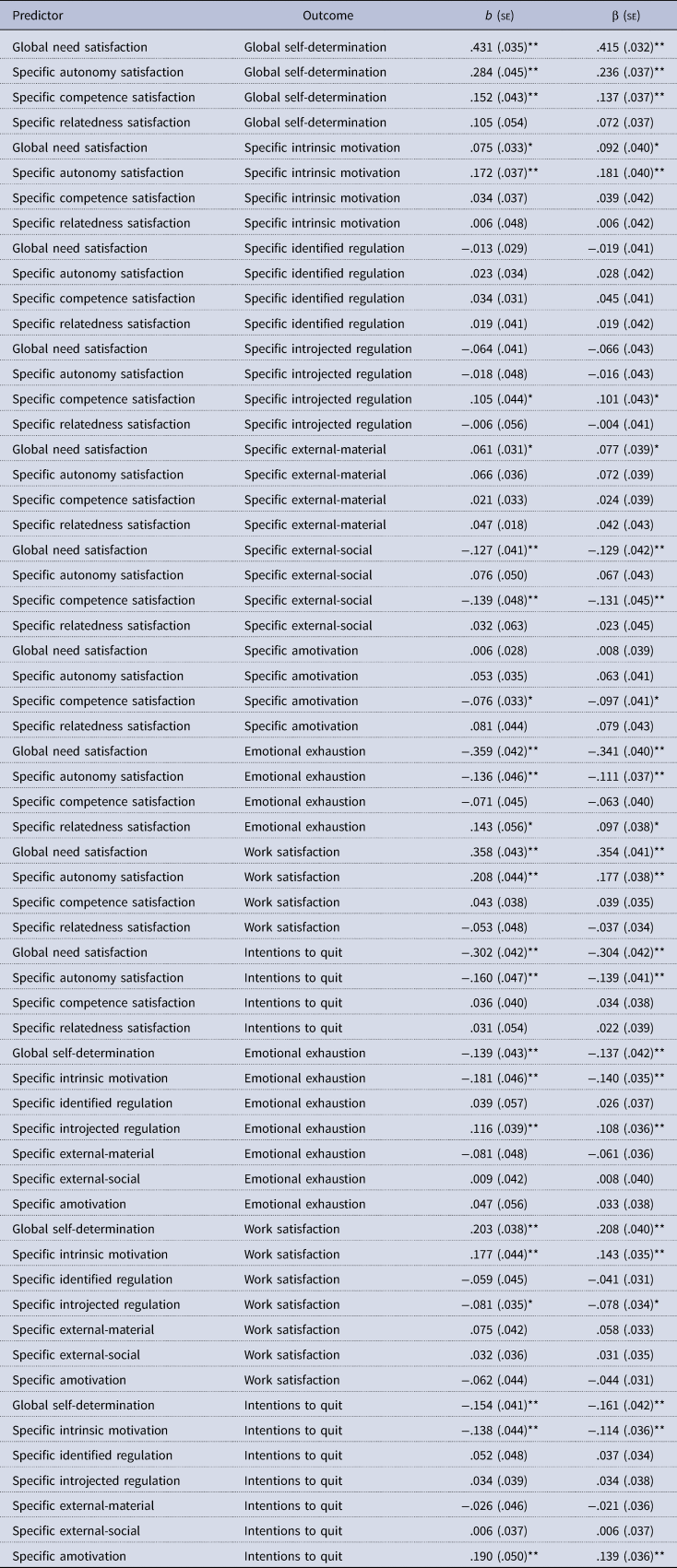

This solution revealed several associations, reported in Table 2. First, partly supporting hypothesis 3, global levels of need satisfaction were associated with higher levels of global self-determination (β = .415), specific intrinsic motivation (β = .092), specific external-material regulation (β = .077), but with lower levels of external-social regulation (β = −.129). These results suggest that when employees' global levels of basic psychological needs are satisfied, they are more likely to work for self-determined, intrinsic, or external-material reasons but also less likely to work for external-social reasons. Beyond global levels of need satisfaction, specific levels of autonomy satisfaction were associated with higher levels global self-determination (β = .236) and specific levels of intrinsic motivation (β = .181), suggesting that employees might also work for self-determined or intrinsic reasons when they experience higher than average levels of autonomy satisfaction in their workplace. Finally, specific levels of competence were associated with higher levels of global self-determination (β = .137) and specific introjected regulation (β = .101), and with lower levels of specific external-social regulation (β = −.131) and specific amotivation (β = −.097). These results suggest that employees experiencing higher than average levels of competence satisfaction at work are more likely to work for global self-determined or introjected reasons, while also being less likely to work for external-social reasons or to be amotivated.

Table 2. Parameter estimates from the mediation model

b, unstandardized regression coefficients; se, standard errors of the coefficient; β, standardized regression coefficients.

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01.

With respect to the associations between work motivation and the wellbeing outcomes, our results provided support for hypotheses 4a and 4b. More specifically, global levels of self-determination and specific levels of intrinsic motivation were both associated with higher levels of work satisfaction (β = .208 for global self-determination; .143 for specific intrinsic motivation), and with lower levels of emotional exhaustion (β = −.137 for global self-determination; −.140 for specific intrinsic motivation) and intentions to quit (β = −.161 for global self-determination; −.114 for specific intrinsic motivation). In addition, specific levels of introjected regulation were associated with higher levels of emotional exhaustion (β = .108) and with lower levels of work satisfaction (β = −.078). Finally, specific levels of amotivation were associated with higher levels of turnover intentions (β = .139). Overall, employees tended to report lower levels of emotional exhaustion and intentions to quit when they worked for self-determined or intrinsic reasons. They also tended to report higher levels of emotional exhaustion and intentions to quit when working for introjected or amotivated reasons, respectively. Conversely, employees reported higher levels of work satisfaction when working for self-determined or intrinsic reasons, but lower levels of work satisfaction when working for introjected reasons.

Direct associations between need satisfaction and the wellbeing outcomes mainly involved employees' global levels of need satisfaction and their specific levels of autonomy satisfaction. More specifically and in support of hypothesis 5, both were associated with higher levels of work satisfaction (β = .354 for global need satisfaction; .177 for specific autonomy satisfaction), and with lower levels of emotional exhaustion (β = −.341 for global need satisfaction; −.111 for specific autonomy satisfaction) and intentions to quit (β = −.304 for global need satisfaction; −.139 for specific autonomy satisfaction). Therefore, employees who experience more work satisfaction, but less emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions tended to have higher levels of global need satisfaction and to experience higher than average levels of autonomy satisfaction at work. Unexpectedly, specific levels of relatedness satisfaction were also associated with higher levels of emotional exhaustion (β = .097), suggesting that more intense interpersonal work relationships tended to result in higher levels of emotional exhaustion.

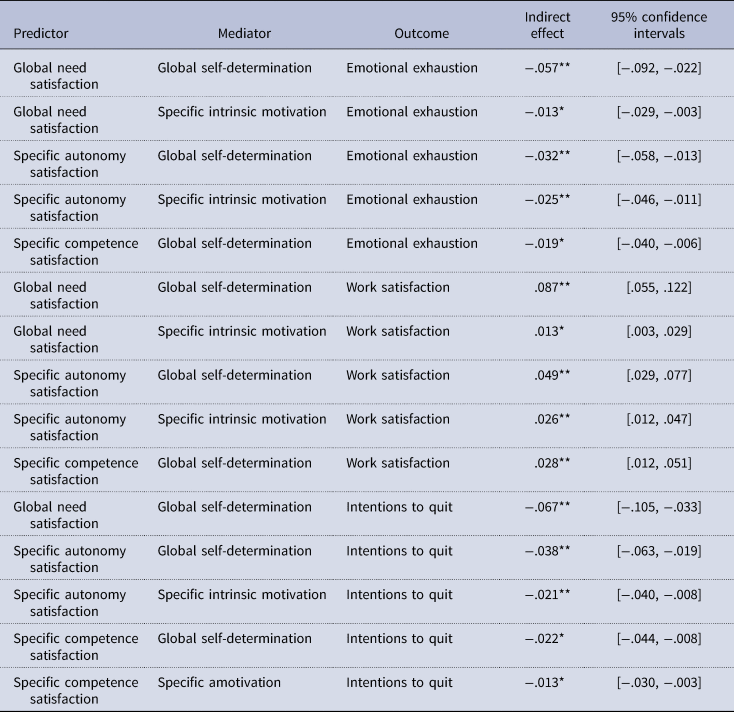

Our results thus suggest 15 indirect (mediated) associations, thus supporting hypothesis 6. The statistical significance of these indirect effects was tested, and the results from these tests are reported in Table 3, indicating that all 15 indirect associations were supported by the data (i.e., all confidence intervals excluded the value of zero). Finally, the proportion of explained variance was moderate for global levels of self-determination (27.8%), emotional exhaustion (28.8%), work satisfaction (37%), and intentions to quit (25.1%), and lower for the specific levels of intrinsic (4.6%), identified (.3%), introjected (1.4%), external-material (1.4%), and external-social (4.1%) regulations, as well as for specific levels of amotivation (2%).

Table 3. Indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals from the partial mediation model

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01.

Discussion

Dimensionality

The purpose of this study was to verify the associations between global and specific levels of need satisfaction and work motivation in the prediction of psychological wellbeing at work proposed by SDT's motivation mediation model (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017). In testing these associations, we relied on bifactor-ESEM analyses (Morin, Arens, & Marsh, Reference Morin, Arens and Marsh2016; Morin, Myers, & Lee, Reference Morin, Myers, Lee, Tenenbaum and Eklund2020) to account for the dual global/specific nature of employees' multidimensional ratings of their own work motivation and need satisfaction. Our results supported the superiority of the bifactor-ESEM representation of work motivation (hypothesis 1a), highlighting the need to disaggregate employees' global levels of self-determination (reflecting their global sense of volition and directedness from the specific qualities associated with each type of behavioral regulation). The factor loadings associated with this global factor matched the hypothesized continuum structure of motivation (i.e., strong positive loadings for the intrinsic motivation items, moderate positive loadings for the identified regulation items, smaller positive loadings for the introjected regulation items, null or negative loadings for the external regulation items, and stronger negative loadings for the amotivation items), thus also supporting hypothesis 1b. This result adds to accumulating evidence supporting the value of a bifactor-ESEM representation of motivation measures anchored in the SDT framework across life domains, including education (Litalien et al., Reference Litalien, Morin, Gagné, Vallerand, Losier and Ryan2017) and work (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018). Although most S-factors retained a meaningful level of specificity once the variance explained by the G-factor was accounted for, the identified regulation and, to a smaller extent, the intrinsic regulation S-factors retained a lower amount of specificity. This observation indicates that employees' ratings of intrinsic and identified regulation mainly served to define their global levels of self-determined work motivation, retaining only a limited amount of specificity beyond these global levels.

Our results also supported the value of a bifactor-ESEM representation of need satisfaction (hypothesis 2), allowing us to obtain a global estimate of employees' global need satisfaction at work, while being able to consider the degree of imbalance (i.e., deviation) in the satisfaction of their specific needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness beyond their global level of need satisfaction. This result thus supports previous research on the usefulness of bifactor representation of need satisfaction (Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Morin, Choisay and Fouquereau2019, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2020a, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huyghebaert-Zouagh, Alibran, Barrault and Vanhove-Meriaux2020b; Sánchez-Oliva et al., Reference Sánchez-Oliva, Morin, Teixeira, Carraça, Palmeira and Silva2017; Tóth-Király et al., Reference Tóth-Király, Bőthe, Orosz and Rigó2019). In this representation, the global need satisfaction factor, together with the specific autonomy and competence satisfaction factors were all well-defined and reliable. In contrast, the specific relatedness factor only retained a limited amount of specificity beyond the variance explained by the global factor. This result suggests that, in this study, the items used to assess relatedness need satisfaction provided a clearer indication of employees' global need satisfaction than of their specific levels of their relatedness satisfaction. In practical terms, this finding suggests a lack of imbalance (or the presence of an alignment) between employees' reports of their relatedness satisfaction relative to their global need satisfaction. This result is particularly interesting when we consider the fact that previous studies have generally revealed that global levels of need satisfaction were often anchored into one specific need for which imbalance was rare. Thus, among generic populations of workers and university students, the need for autonomy appeared to play such an anchoring role with regard to global levels of need satisfaction, retaining only a limited amount of specificity once global levels of need satisfaction are taken into account (Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Morin, Choisay and Fouquereau2019, Reference Gillet, Morin, Huyghebaert-Zouagh, Alibran, Barrault and Vanhove-Meriaux2020b; Sánchez-Oliva et al., Reference Sánchez-Oliva, Morin, Teixeira, Carraça, Palmeira and Silva2017). In contrast, the need for relatedness seemed to play a similar role among younger populations of students (Garn, Morin, & Lonsdale, Reference Garn, Morin and Lonsdale2019) and nurses (Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, Morin, Forest, Fouquereau, & Gillet, Reference Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, Morin, Forest, Fouquereau and Gillet2022), a result that was replicated in the present study.

Overall, bifactor-ESEM made it possible to simultaneously consider the role played by global and specific components of work motivation and need satisfaction. In doing so, this study was able to address the limitations of previous studies that failed to take into this multidimensional nature into account, thus resulting in a more accurate picture of the associations occurring at the global versus specific level.

Associations between need satisfaction and work motivation

Our results revealed significant associations between need satisfaction and work motivation. First, in line with hypothesis 3, employees' global need satisfaction was associated with higher levels of global self-determination, which is aligned with previous research (e.g., Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2020) suggesting that experiencing need satisfaction at work allows employees to act in a more volitional and self-directed manner. In addition, global levels of need satisfaction were also found to be associated with higher specific levels of intrinsic and external-material regulation but with lower levels of external-social regulation. These results suggest that when employees' basic psychological needs are globally satisfied, they are more likely to work for intrinsic or external-material reasons, but less likely to work for external-social reasonsFootnote 1.

These results match those obtained in previous studies (e.g., Dysvik, Kuvaas, & Gagné, Reference Dysvik, Kuvaas and Gagné2013) showing that when employees basic psychological needs are satisfied, they are more likely to work because of the interest and enjoyment associated with working. Similarly, when employees feel that their needs are globally satisfied, they are less likely to be driven to work by external-social reasons due to the fact that their relatedness need (which is captured by the global factor) is already adequately fulfilled. However, when employees' needs are globally satisfied, they also seemed more likely to work to achieve material gains. One explanation might be that when their needs are satisfied, employees do not need to engage in compensatory behaviors (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, Reference Vansteenkiste and Ryan2013) to counter a lack of autonomy, competence, or relatedness at the expense of their work, and can instead focus directly on their core work-related tasks by providing a service to an employer in exchange for money. In the Quebec public health care system, the unionized nature of the nursing occupation might have contributed to the participants' perceptions of material gains as a required form of recognition for the highly demanding nature of their work.

Turning our attention to more specific associations, our results suggest that when employees feel a sense of autonomy and competence at work beyond their global need satisfaction, they tend to adopt a more volitional and self-determined approach to their work, thus providing further support for hypothesis 3. These results are in line with previous research (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gagné, Morin and Forest2018) demonstrating that higher global self-determination tend to be positively associated with the satisfaction of the needs for autonomy and competence, and suggest that a positive imbalance in employees' specific levels of autonomy and competence need satisfaction might have additional positive effects on their global levels of self-determined work motivation. The benefits of such a positive imbalance are also supported by the relations observed between the specific level of satisfaction of the need for competence and lower specific levels of amotivation and external-social regulation, as well as by the positive associations found between the specific levels of autonomy need satisfaction and higher specific levels of intrinsic motivation. However, the presence of a positive imbalance in the satisfaction of the specific need for competence (beyond one's global levels of need satisfaction) might be a double-edged sword, as it was also found to be associated with higher specific levels of introjected regulation. Thus, employees experiencing higher than average levels of satisfaction of their need for competence at work might be partly driven internal pressures to maintain this high level of competence satisfaction. Overall, our results suggest that employees characterized by high specific levels of satisfaction of their need for autonomy tend to act in a more self-determined manner at work. Employees characterized by high specific levels of satisfaction of their need for competence also tend to experience higher global self-determined motivation and specific levels of intrinsic motivation, showing that they find their work to be inherently rewarding and enjoyable. However, these employees also tend to be motivated by internal pressures (i.e., specific levels of introjected regulation), although they also appear to be less likely to experience an absence of motivation or be externally motivated by social factors.

Finally, the observed lack of associations involving the specific relatedness factor is consistent with the lack of specificity associated with this factor once global levels of self-determination were considered, suggesting that ratings of relatedness satisfaction are an anchor upon which their global levels of need satisfaction are organized (Huyghebaert-Zouaghi et al., Reference Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, Morin, Forest, Fouquereau and Gillet2022). As such, this result does not indicate that relatedness satisfaction is not important, simply that it does not contribute to employees' motivation beyond the role played by their global levels of need satisfaction observed across all three needs. Future research is needed to replicate this finding in employees from other sectors and occupations.

Associations between work motivation and wellbeing

We found associations between employees' work motivation and their levels of psychological wellbeing. First, in line with hypothesis 4a, our study suggests that globally self-determined employees and those motivated intrinsically tend to be more satisfied with their work, to experience less emotional exhaustion, and to express fewer turnover intentions. These results are generally well-aligned with those reported by previous studies (e.g., Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017; Fernet et al., Reference Fernet, Trépanier, Demers and Austin2017). Conversely, employees who work for more introjected reasons tended to report higher levels of emotional exhaustion and lower levels of work satisfaction, while amotivated employees were more likely to consider leaving their job. These results also align with hypothesis 4b as well as previous studies (e.g., Austin et al., Reference Austin, Fernet, Trépanier and Lavoie-Tremblay2020; Choi, Cho, Kim, Kim, Chung, & Lee, Reference Choi, Cho, Kim, Kim, Chung and Lee2020; Gagné et al., Reference Gagné, Forest, Vansteenkiste, Crevier-Braud and Van den Brock2015) and with SDT's (e.g., Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017) assumption that more controlled forms of motivation (e.g., introjected) and amotivation are likely to lead to higher levels of emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions.

Associations between need satisfaction and wellbeing

With regard to the associations between need satisfaction and psychological wellbeing at work, our results showed that employees characterized by higher global levels of need satisfaction and specific levels of autonomy satisfaction tended to be more satisfied with their work, to experience less emotional exhaustion, and to report less intentions to leave their current occupation. These results match hypothesis 5 and are in line with previous research showing that employees who perceive less personal control over their work environment are more likely to experience increased levels of emotional exhaustion (Browning et al., Reference Browning, Ryan, Thomas, Greenberg and Rolniak2007), whereas those who receive autonomy support from their supervisors are more likely to report higher levels of work satisfaction (Moreau & Mageau, Reference Moreau and Mageau2012). Turnover intentions have also been previously found to decrease in response to a more autonomous work environment (Boudrias et al., Reference Boudrias, Trépanier, Foucreault, Peterson and Fernet2020). These results are consistent with findings previously reported by Laschinger, Shamian, and Thomson (Reference Laschinger, Shamian and Thomson2001), suggesting that perceptions of autonomy and control tended to predict workplace satisfaction and trust, two important determinants of employees' wellbeing. Therefore, fostering a need satisfying work environment, while also putting more emphasis on the autonomy satisfaction, might help to reduce workplace turnover and to increase work satisfaction.

Contrary to previous research and our expectations, we found that employees who report higher specific levels of relatedness satisfaction (i.e., a positive imbalance) tend to experience more emotional exhaustion. This result is unexpected as most previous studies found a positive association between employees' relatedness satisfaction and their workplace wellbeing. Social support from supervisors (Van der Ploeg & Kleber, Reference Van der Ploeg and Kleber2003) and coworkers (O'Mahony, Reference O'Mahony2011) are generally seen as important buffers against emotional exhaustion and burnout, while interpersonal conflicts tend to exacerbate these negative outcomes (García-Izquierdo & Ríos-Rísquez, Reference García-Izquierdo and Ríos-Rísquez2012). One possible explanation for this finding is that participants in our sample had an average of 2 years of occupational tenure. As nurses are at greater risk of leaving their job (organization or departments, units, team) during the first years in employment (Rudman, Gustavsson, & Hultell, Reference Rudman, Gustavsson and Hultell2014), they may not have had sufficient time to form meaningful workplace relationships, and instead may have experienced emotional exhaustion from their initial efforts to develop meaningful workplace relationships and to manage emerging social dynamics within a stressful work context. Another possible explanation might be that extreme types of interpersonal relationships (i.e., imbalance) might be detrimental for nurses whose work is naturally characterized by intensive relationships with highly vulnerable people (e.g., patients and their relatives). Thus, having to deal with higher-than-average levels of intensive interpersonal relationships might leave nurses little time for relaxation and rest, in turn increasing their emotional exhaustion (Gillet, Fernet, Colombat, Cheyroux, & Fouquereau, Reference Gillet, Fernet, Colombat, Cheyroux and Fouquereau2021). This ‘extreme imbalance’ interpretation is consistent with the global lack of specificity which was found to remain associated with the relatedness S-factors, suggesting that this unexpected, and undesirable, effect might be related to the few employees for whom interpersonal relations become more intense than the norm. Although this finding is aligned with the ‘too much of a good thing’ perspective (Caesens & Stinglhamber, Reference Caesens and Stinglhamber2020), suggesting curvilinear relations between social support and employees' outcomes (i.e., trust, affective commitment), future studies are needed to verify the replicability of these associations.

Mediation

Finally, coming back to our global objective to empirically assess SDT's motivation mediation model (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017), our results added to accumulating evidence supporting this model (Garn, Morin, & Lonsdale, Reference Garn, Morin and Lonsdale2019; Jang, Kim, & Reeve, Reference Jang, Kim and Reeve2012; Olafsen, Deci, & Halvari, Reference Olafsen, Deci and Halvari2018), by demonstrating that need satisfaction contributed to employees' psychological wellbeing in part via the mediating role of work motivation (hypothesis 6). More specifically, global self-determination, specific intrinsic motivation and, to a smaller extent, specific amotivation, were found to mediate the associations between global need satisfaction, specific autonomy and competence satisfaction, and various indicators of psychological wellbeing at work (emotional exhaustion, work satisfaction, and intentions to quit). In practical terms, these results suggest that when employees' basic psychological needs are met in their workplaces, they tend to endorse more adaptive forms of motivation, which ultimately help them to experience higher levels of psychological wellbeing at work.

Practical implications

Our results have practical implications for the development and implementation of strategies aimed at preventing negative, and nurturing positive, workplace wellbeing outcomes. More specifically, while our results suggest that global levels of need satisfaction and self-determination should be nurtured as those appeared to be the core drivers of wellbeing, these results also highlight the specific aspects of need satisfaction and work motivation that should be targeted in a more direct way. For example, if managers engage in behaviors that support employees' basic psychological needs, employees may feel more autonomous and competent at work, which promotes the adoption of global self-determined or specific autonomous motivations. This could be achieved by encouraging employees to use their judgment whenever appropriate and to provide praise for good work to reinforce employees' confidence in their abilities. When employees' needs are met and they are more autonomously motivated, wellbeing can be further reinforced. In other words, strategies aimed at meeting employees' psychological needs can increase autonomous motivation and, in turn, promote their job satisfaction while preventing their emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions.

Care should be taken when designing strategies specifically focused on relatedness satisfaction to avoid creating an imbalance in the satisfaction of this specific need (i.e., experiencing high levels of relatedness beyond one's global levels of need satisfaction), which we found to have a negative effect on wellbeing. Indeed, while maintaining social connections with others brings a multitude of benefits for wellbeing, experiencing social overload (i.e., being exposed to more social contacts than one can handle; McCarthy & Saegert, Reference McCarthy and Saegert1978) could be detrimental when employees do not have the necessary resources to tackle this overload. One promising avenue for taming social overload could be incorporating brief periods of solitude (i.e., the state of being alone and not physically with others; Nguyen, Weinstein, & Ryan, Reference Nguyen, Weinstein, Ryan, Coplan, Bowker and Nelson2021) into employees' workday. Recent studies (Nguyen, Ryan, & Deci, Reference Nguyen, Ryan and Deci2018, Reference Nguyen, Weinstein and Deci2022) demonstrated that even a brief solitude experience (which is distinct from loneliness) is accompanied by a deactivation effect that decreases high-arousal affects that typically characterize the nursing occupation. This brief voluntary alone period could allow nurses to regulate their own emotions and to regain their relatedness balance.

Limitations and future directions

The present study adds to the literature through testing SDT's motivation mediation model while accounting for the multidimensional nature of need satisfaction and work motivation. However, it is not without limitations. First, participants were all French-Canadian nurses working in the Quebec public healthcare system. As such, our findings may not be applicable to nurses in other provinces and countries characterized by different healthcare systems, and to nurses working in the public versus private system. It would also be interesting to replicate the current study among other populations of healthcare workers (e.g., physicians, pharmacists, etc.) and in other organizational contexts.

Second, our study only focused on a subset of wellbeing indicators. Future studies should rely on a more diverse range of outcomes. This should include outcomes that are objectively measured (e.g., physiological indicators of health) in order to expand the application of SDT-based interventions to a wider range of issues. Other studies would do well in incorporating measures focusing on the need supportive and thwarting characteristics of the social environment, rather than solely on nurses’ reports of the extent to which their needs are satisfied. Likewise, future research should also consider the extent to which employees' global and specific levels of psychological needs might be frustrated by their work environment, as well as the role played by work characteristics known to thwart the satisfaction of their psychological needs (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, Reference Vansteenkiste and Ryan2013). These additions would make it possible to achieve a more comprehensive perspective of the mechanisms at play in influencing employees' wellbeing.

The cross-sectional design of this study introduces another important limitation which is the inability to draw causal inferences from our results, or to ascertain the directionality of the observed associations. Future longitudinal or experimental research could expand on the current study by helping to determine causality and directionality in this mediation model. Because self-report measures were used to gather data, self-report biases (i.e., social desirability, recall) might also play a role in our results. In the future, data obtained through other means would provide additional evidence of reliability and validity (e.g., obtaining data from other observational sources such as supervisors or colleagues).

Another aspect worth investigating further is the negative association between specific relatedness satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Studying the extent to which relatedness satisfaction might, or might not, benefits workers can help to specially design programs that do not overwhelm individuals with too much socialization, without sacrificing the basic psychological need for interpersonal relationships. Finally, apart from merely focusing on need satisfaction as a foundation for autonomous motivation and wellbeing, future studies could more closely look at the issue of imbalance in these needs as our study suggests that experiencing too much satisfaction of a particular need might also have minor detrimental effects, thus potentially making imbalanced levels of need satisfaction counterproductive.

Conclusion

SDT is a pivotal perspective from which to study workplace wellbeing. Adding to this theory, this study supported the usefulness of the bifactor-ESEM representation of the underlying structure of employees' need satisfaction and work motivation, allowing us to better capture their complexity and dual nature. When considering the motivation mediation model from this global/specific perspective, we found that nurses who work for self-determined reasons do so because their global levels of need satisfaction are high, as are their specific levels of autonomy satisfaction and competence satisfaction. In turn, self-determined nurses experience less emotional exhaustion, express fewer turnover intentions, and are more satisfied with their work. Therefore, results should be carefully applied to practical settings as well as considered in theoretical advancement to continue promoting positive workplace wellbeing outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2022.76

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this paper was supported by grants from the Social Science and Humanity Research Council of Canada (435-2018-0368), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (275334), and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Société et Culture (127091 and 2019-SE1-252542). The second author was also supported by a Horizon Postdoctoral Fellowship from Concordia University.

Conflict of interest

None declared.