Introduction

To mitigate the spread of infectious diseases, individual infection preventive behaviours – such as mask-wearing, hand washing, and hand sanitization – are essential alongside vaccination and broader social regulatory measures, including lockdowns. These individual actions are particularly important due to their relatively low invasiveness and economic cost compared to large-scale interventions. The effectiveness of individual infection prevention has been previously reported [Reference Chu1, Reference Mo2]. A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that infection preventive behaviours were effective in slowing the transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [3].

Understanding the factors influencing preventive behaviour is crucial to its promotion. These factors may be classified into contextual factors, socioeconomic position, and intermediary determinants [Reference Shushtari4]. Among these, intermediary determinants – such as individual knowledge, attitudes, and risk perception – serve as the direct pathway through which broader structural conditions influence preventive behaviour. In particular, risk perception of infectious diseases is considered a key determinant. Slovic identified two primary dimensions of risk perception: dread and unknown [Reference Slovic5]. Dread risk perception encompasses elements such as high fatality and uncontrollability, whereas unknown risk perception includes characteristics such as a lack of awareness of exposure or the consequences. Stronger perceptions along these dimensions are associated with greater support for regulatory measures. The association between COVID-19 infection preventive behaviours and risk perception has been documented globally [Reference Dryhurst6]. Furthermore, repeated cross-sectional and cohort studies have observed that COVID-19 risk perception was associated with the implementation of preventive behaviour [Reference Schneider7, Reference Murakami, Yamagata and Miura8]. Risk perception of COVID-19 is not constant, with increases after social regulatory measures and decreases after relaxation of measures [Reference Yamagata, Murakami and Miura9, Reference Attema10].

One key determinant of risk perception is prior experience related to the risk itself [Reference Wachinger11, Reference Machida12]. Previous studies have found that individuals who experienced infection personally, within their families, or believed themselves to have been infected reported higher levels of COVID-19 risk perception [Reference Schneider7, Reference Ishikawa13]. In addition, cohort studies revealed that individuals with a history of COVID-19 infection were less likely to refrain from social activities such as gatherings with friends or colleagues, whereas those with acquaintances diagnosed with COVID-19 were more likely to restrict such activities [Reference Mori14]. However, these studies did not control for prior risk perception or preventive behaviour, raising the possibility of reverse causality. One recent study reported that experiencing COVID-19 infection led to reduced mask-wearing and hand washing, partially due to a decreased perceived risk of infection, even after controlling for prior risk perception or preventive behaviour [Reference Lam15]. As a result, there is limited research examining the causal impact of infection experience on subsequent risk perception and preventive behaviour. A deeper understanding of how infection experience relates to risk perception and preventive behaviour may offer insights into the psychology of individuals who have been infected. In particular, if risk perception mediates the relationship between infection experience and preventive behaviour, recognizing differences in risk perception between infected and non-infected individuals could inform public health policy development.

Therefore, this study examined whether experience of COVID-19 infection led to changes in risk perception and preventive behaviours among participants in a panel survey conducted in Japan between January 2020 and March 2024, comprising 30 waves. Using propensity score matching, we selected participants with infection experience and matched them with participants of similar baseline characteristics, including risk perception, preventive behaviours, sociopsychological variables, and individual attributes. We then evaluated the impact of infection experience on risk perception and preventive behaviours, including mask-wearing and hand disinfection. Additionally, we investigated whether infection experience influenced preventive behaviour through the mediating role of risk perception.

Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Behavioral Subcommittee of the Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Human Sciences, The University of Osaka (Authorization Number: HB019-099: until February 2023; HB022-117: from February 2023 onward). Informed consent was obtained online from all participants prior to the commencement of the survey.

Participants

The panel survey was conducted among individuals aged ≥18 years residing in Japan. Initially, surveys were administered every 2 weeks to 1 month from January 2020, and then every 2 months from the seventh wave (May 2020), amounting to a total of 30 waves. Detailed descriptions of the survey have been provided in prior studies [Reference Murakami, Yamagata and Miura8, Reference Yamagata, Murakami and Miura9, Reference Yamagata, Teraguchi and Miura16]. In each wave, inattentive participants were identified using the Directed Questions Scale (DQS) [Reference Maniaci and Rogge17, Reference Miura and Kobayashi18]. The DQS consists of two items that instruct respondents to select a specific response option, allowing the identification of inattentive individuals. Individuals who failed to follow the instructions on both items were excluded. The initial wave included 1,248 participants, and 600 new participants were added during the 13th wave (May 2021) (Supplementary Figure S1). Participants received a reward of 120–150 yen (equivalent to 0.8–1 United States dollar) per survey.

Questions regarding participants’ own COVID-19 infection experiences were introduced in the 11th wave (January 2021); thus, only participants from wave 11 onwards were included in this study. Of the 1,248 initial participants, 600 remained by the 11th wave, with one individual excluded for not responding to the social gender question. Among the 600 new participants in the 13th wave, 11 were excluded for the same reason. Consequently, the total number of participants included in the analysis was 1,188. This exceeded the minimum sample size of 384, as calculated based on the Japanese population, a 95% confidence interval (CI), and a 5% margin of error [Reference Serdar19].

Survey items

Outcome

Infection preventive behaviour was assessed in each wave from wave 1 to wave 30 by asking participants whether they were currently engaging in alcohol-based hand disinfection and mask-wearing at the time of the survey [Reference Murakami, Yamagata and Miura8]. Responses were categorized dichotomously as either implemented or not implemented.

In line with previous studies [Reference Slovic5, Reference Yamagata, Teraguchi and Miura16], risk perception related to COVID-19 was assessed using two dimensions: dread and unknown risk. Dread risk perception was evaluated with two items: ‘Will result in death’ (dread risk perception 1) and ‘Never know when it might happen’ (dread risk perception 2). Unknown risk perception was similarly measured using two items: ‘We may be affected without realizing it’ (unknown risk perception 1) and ‘Cannot tell what type of effect this will have’ (unknown risk perception 2). Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The mean scores of the two items were calculated to determine overall dread and unknown risk perceptions respectively. Additionally, for sensitivity analysis, participants were asked to estimate the probability of COVID-19 infection on a scale from 0% to 100% (hereinafter referred to as the estimated probability of infection) [Reference Yamagata, Teraguchi and Miura16].

Temporal changes in risk perception (dread and unknown) and preventive behaviours (hand disinfection and mask-wearing) among the 1,188 participants are depicted in Supplementary Figure S2.

Exposure factors (infection experience)

A participant’s infection experience was defined based on whether they reported being newly infected in survey wave x (i.e., infected between waves x − 1 and x). Participants who indicated infection in wave x but not in any prior wave were considered newly infected. Because this question was introduced in wave 11, analyses of participants who had been enrolled since wave 1 excluded those who reported having had an infection experience at wave 11, and the analysis period for these participants started from wave 12 onward. For example, a participant who had no infection experience at wave 11 but reported infection at wave 12 was considered infected at wave 12. Similarly, for participants who joined the study at wave 13, those who reported infection experience at wave 13 were excluded, and their analysis began from wave 14 onward.

Covariates

Covariates included factors associated with infection experience, risk perception, and preventive behaviour in wave x, as identified in prior literature [Reference Murakami, Yamagata and Miura8, Reference Yamagata, Murakami and Miura9, Reference Yamagata, Teraguchi and Miura16, Reference Uchibori20–Reference Adachi24]. Specifically, items measured in wave x-1 were used: dread and unknown risk perception, hand disinfection, mask-wearing, interest in COVID-19 (a variable representing and individual’s interest in the COVID-19 pandemic; 7-point Likert scale), pathogen-avoidance tendency (a variable representing an individual’s psychological disposition to avoid uncleanliness and exposure to others’ coughs; mean of five items; 7-point Likert scale) [Reference Duncan, Schaller and Park25, Reference Kitamura and Matsuo26], family members with infection experience, and COVID-19 vaccination history. Gender, age, and residential region (prefectures including Tokyo and designated cities vs. others) were recorded at initial participation (wave 1 or wave 13).

Statistical analysis

Extraction of individuals in the infection group and non-infection group using propensity score matching.

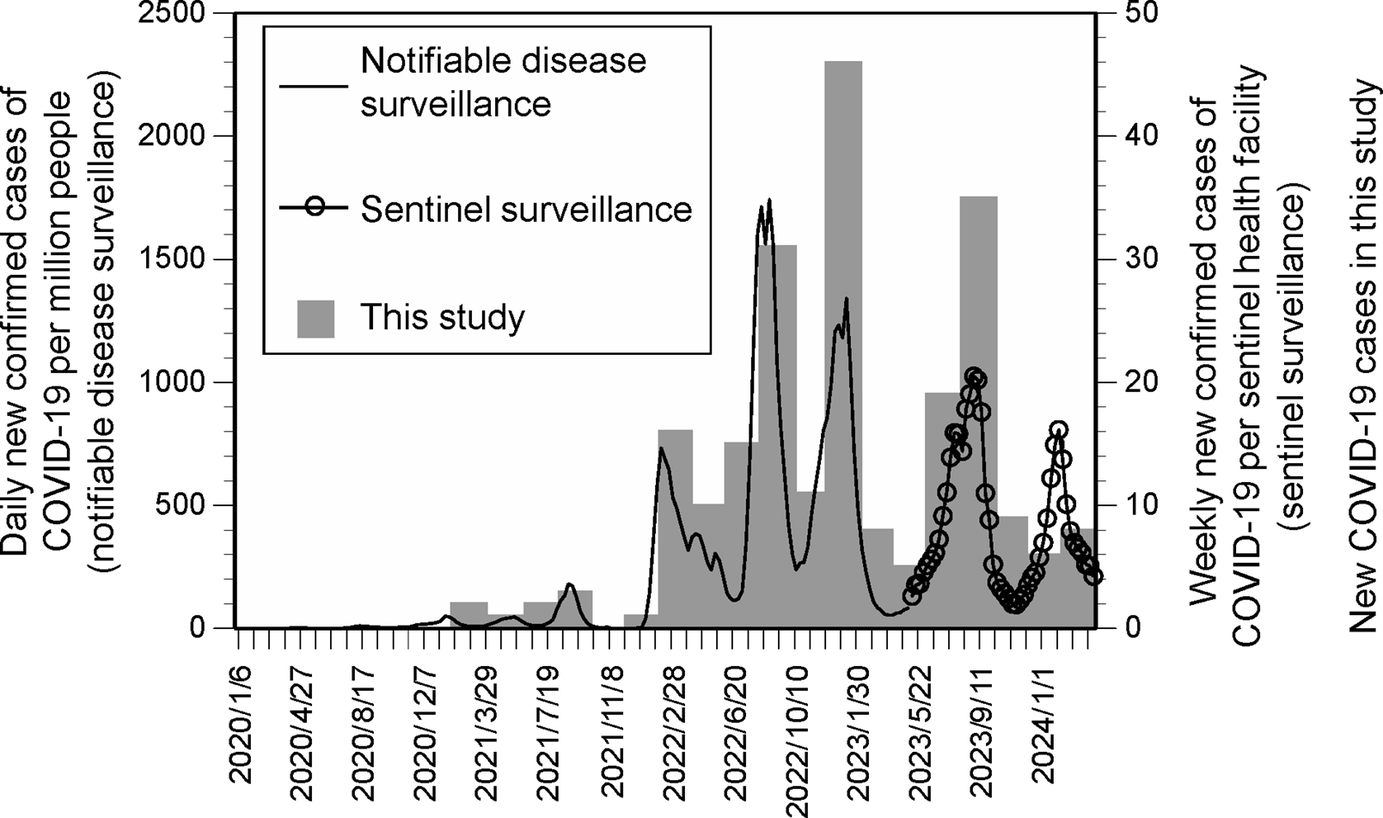

To obtain infection and non-infection groups with similar covariate characteristics but differing in infection experience, participants were selected using propensity score matching [Reference Rosenbaum and Rubin27]. First, the number of newly infected individuals was confirmed. A total of eight waves were identified – waves x = 18–23 (March 2022 to January 2023) and x = 26–27 (July to September 2023) – in which ≥10 new infections were reported per wave (Figure 1). Temporal trends in newly infected individuals generally corresponded with national trends in confirmed COVID-19 cases in Japan [Reference Mathieu28, 29]. For the confirmed COVID-19 cases shown here, data prior to 8 May 2023, were obtained from the notifiable disease surveillance system. On that date, COVID-19 was reclassified into the same category as seasonal influenza, and preventive measures were relaxed. After this change, data were obtained from the sentinel surveillance system.

Figure 1. Number of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in Japan, as well as data from this study.

The infection group comprised participants reporting their first infection in wave x, while the non-infection group comprised those without any prior infection experience. Participants with missing values were excluded from propensity score matching due to their small number (Supplementary Table S1). For each of the eight waves, nearest-neighbour matching was performed with a calliper of 0.01, adjusting for covariates. This resulted in the extraction of 135 matched pairs (270 individuals in total).

Analysis of differences in outcomes and covariates between infected and non-infected individuals.

Analysis 1

To determine whether differences existed in the variance and mean values of covariates between infection and non-infection groups prior to new infection (wave x-1), F-tests and t-tests were employed for continuous variables (e.g., risk perception), while chi-square tests were used for categorical variables (e.g., preventive behaviour).

Analysis 2

To assess whether the outcomes differed between infection and non-infection groups following new infection (wave x), F-tests, t-tests, or chi-square tests were conducted, as appropriate.

Analysis 3

As a significant difference in gender was identified between the two groups in Analysis 1, multiple regression and binary logistic regression analyses were performed for risk perception and preventive behaviour, respectively, adjusting for gender.

Analysis 4

Given that Analyses 2 and 3 identified significant differences in unknown risk perception 1 and mask-wearing between the two groups, further analysis was conducted using multiple regression and binary logistic regression. In this model, infection experience was treated as the exposure factor, mask-wearing as the outcome, and unknown risk perception 1 as the mediating factor. A 95% CI for the indirect effect was estimated using a bias-corrected method with 2,000 bootstrap samples.

For all Analyses 1–3, sensitivity analyses were conducted for each risk perception item and the estimated probability of infection, instead of the composite measures derived from two items each for dread risk perception and unknown risk perception. Namely, t-tests were used to compare scores on each risk perception item and the estimated probability of infection between infection and non-infection groups (wave x-1 and wave x). Multiple regression analyses were also performed to analyse the association between infection experience and each risk perception item or estimated probability of infection, adjusting for gender. Analyses were performed using R [30, Reference Randolph31]. SPSS version 28 (IBM, Chicago, IL), and HAD [Reference Shimizu32]. Effect sizes were interpreted following a previous study [Reference Cohen33], with |d| = 0.20 considered small, 0.50 medium, and |φ| = 0.10 considered small, 0.30 medium. Statistical significance was set at P = 0.05.

Results

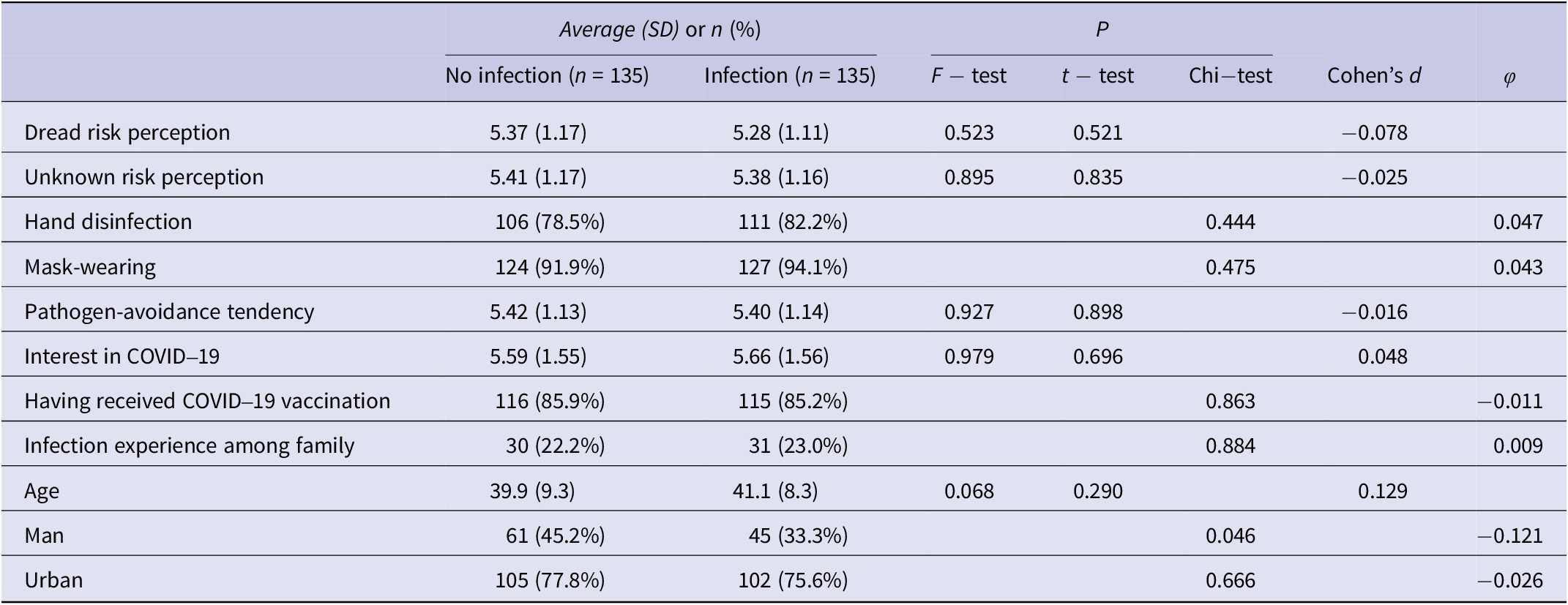

Comparison of covariates revealed no significant differences (P > 0.05), except for gender, between the infection and non-infection groups prior to infection experience (Table 1). A significant difference with a small effect size was noted for gender between the two groups (P = 0.046, φ = −0.121).

Table 1. Comparison of covariates between the infection and non-infection groups during the wave preceding infection experience

SD, standard deviation.

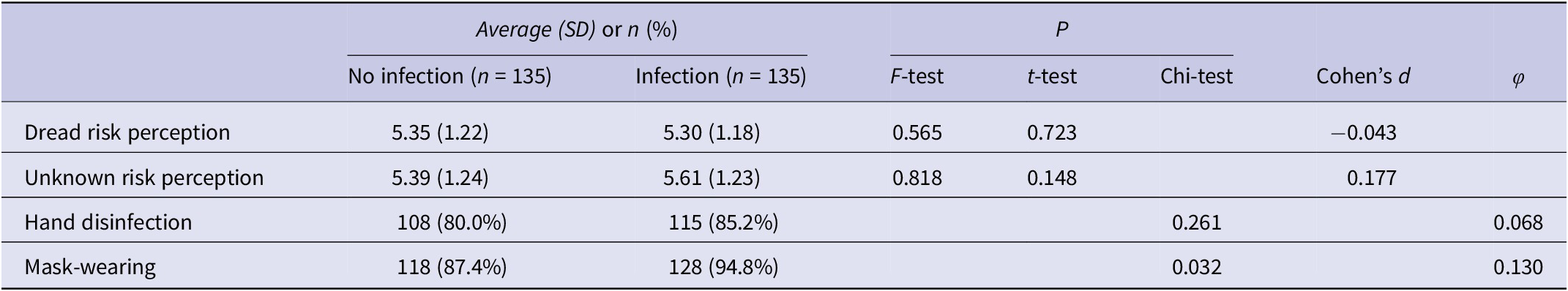

Regarding outcomes following infection experience (Table 2), no significant differences were observed in the variance or mean values of dread and unknown risk perceptions between the groups (P > 0.05). The proportion of participants wearing masks was significantly higher in the infection group than in the non-infection group (94.8% vs. 87.4%, P = 0.032), whereas no significant difference was observed in the proportion engaging in hand disinfection between the two groups (85.2% vs. 80.0%, P = 0.261). The effect size for mask-wearing ranged from small to medium (φ = 0.130).

Table 2. Comparison of risk perception and implementation of preventive behaviour between the infection and non-infection groups in the wave following infection experience

SD, standard deviation.

Sensitivity analysis showed no significant differences in any items related to risk perception before infection experience between the groups (P > 0.05, Table 3). After infection experience, participants in the infection group exhibited significantly higher levels of dread risk perception 2 (6.48 vs. 6.13, P = 0.004), unknown risk perception 1 (6.33 vs. 5.79, P < 0.001), and estimated probability of infection (64.0 vs. 54.6, P = 0.001) compared with the non-infection group. Conversely, dread risk perception 1 was significantly lower in the infection group (4.12 vs. 4.58, P = 0.041). Unknown risk perception 2 showed a significant difference in variance (P = 0.031) but not in mean value (P = 0.651). Among the items, unknown risk perception 1 had the largest absolute effect size (|d| = 0.489). Multivariable analyses adjusting for gender yielded similar findings (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 3. Comparison of individual risk perception items between the infection and non-infection groups

SD, standard deviation.

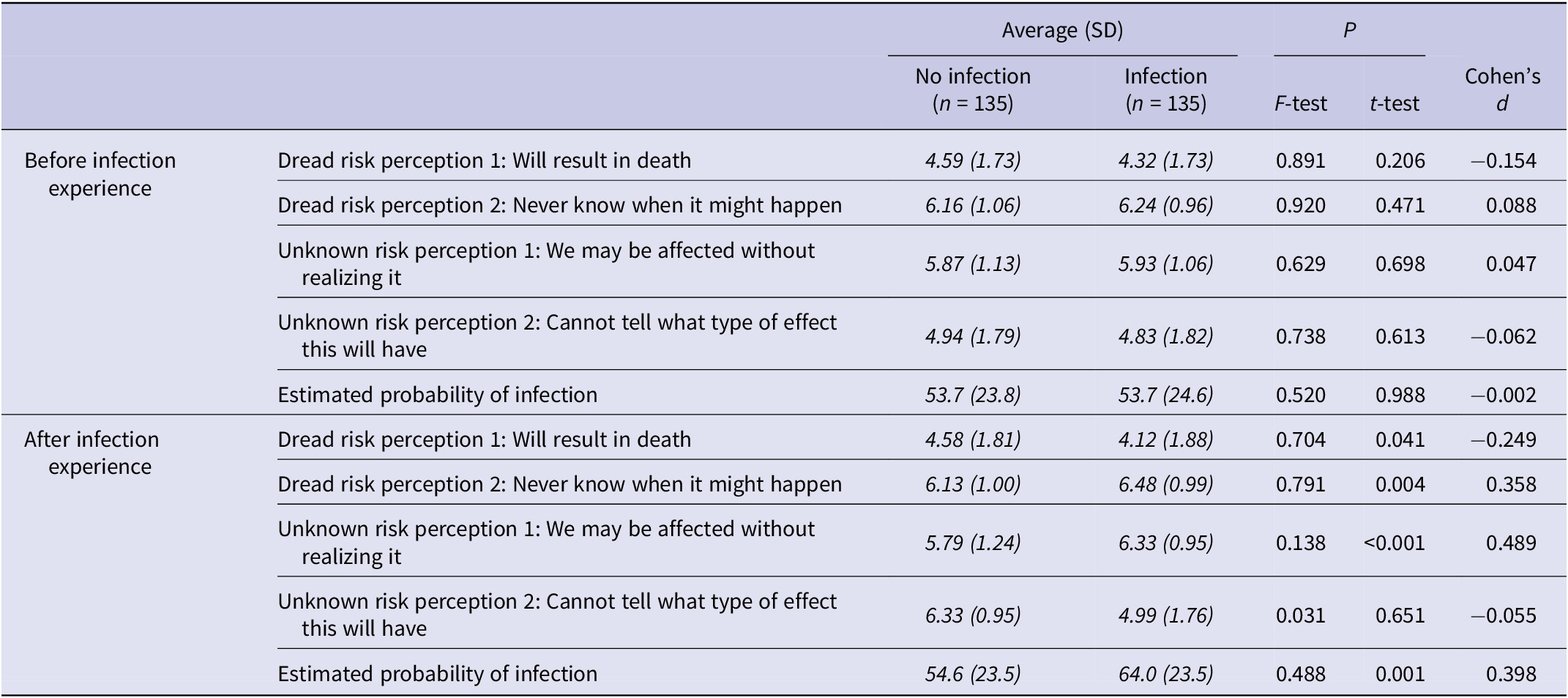

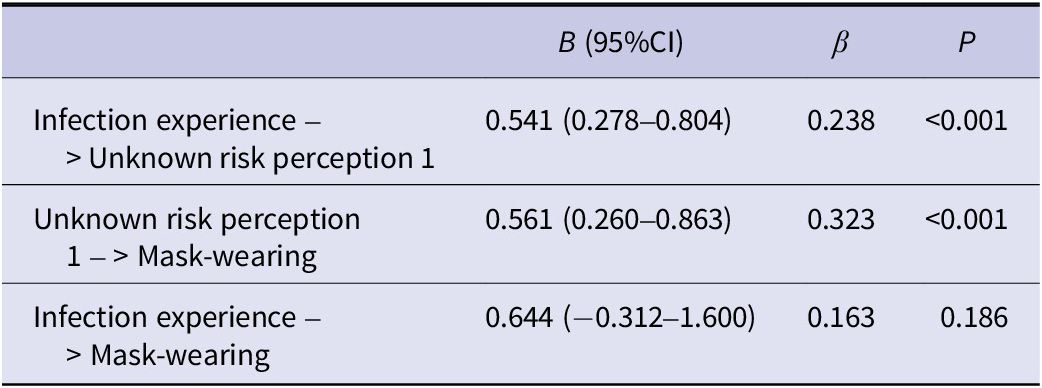

In an analysis with mask-wearing as the outcome, infection experience as the exposure factor, and unknown risk perception 1 as the mediating factor (Table 4), a significant positive association was observed between infection experience and unknown risk perception 1 (unstandardized partial regression coefficient B [95% CI] = 0.541 [0.278–0.804], P < 0.001), as well as between unknown risk perception 1 and mask-wearing (B = 0.561 [0.260–0.863], P < 0.001). The indirect effect of infection experience on mask-wearing, mediated by unknown risk perception 1, was also significant (B [95% CI] = 0.303 [0.126–0.584]).

Table 4. Associations between infection experience and mask-wearing, with unknown risk perception 1 (‘We may be affected without realizing it’) as a mediating factor. Indirect effect of infection experience on mask-wearing via unknown risk perception 1: B (95% CI) = 0.303 (0.126–0.584)

B, unstandardized partial regression coefficient; β, standardized partial regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Following infection experience, the infection group demonstrated higher levels of certain elements of risk perception – specifically, perceived risk of being unknowingly affected and estimated probability of infection – as well as increased mask-wearing, compared to the non-infection group. In contrast, prior to infection experience, the two groups did not differ significantly in these or other sociopsychological and individual characteristics, except for gender. This association remained consistent after adjusting for gender in multivariable analysis. Moreover, an indirect effect of infection experience on mask-wearing, mediated by perceived risk of being unknowingly affected, was also observed.

Overall, the propensity score matching effectively identified comparable pairs of infected and non-infected participants. Furthermore, infection experience appears to elevate unknown risk perception – that is, the belief that one might be infected without realizing it – which in turn promotes mask-wearing. Although the estimated probability of infection is a distinct construct from dread or unknown risk perception, the observed increase in this probability after infection is consistent with heightened perception of potential undetected infection.

These findings suggest that infection experience heightens the perceived risk of unrecognized infection, resulting in a higher estimated probability of infection. In reality, however, infection provides a degree of immunity, so the actual risk of reinfection does not increase among individuals who have experienced COVID-19 infection [Reference Altarawneh34]. In this study, infected participants were identified from the 18th survey wave (March 2022), which corresponded with the spread of the Omicron variant [35]. The high transmissibility of Omicron may have contributed to a perception among infected participants that they had been unknowingly infected.

Conversely, this study found that infection experience had an ambivalent effect on two items of dread risk perception. While the fear of not knowing when infection might occur increased similarly to the perceived risk of being unknowingly affected, the fear that COVID-19 could be fatal decreased. A previous study reported that individuals who had experienced severe COVID-19 themselves, or in their families, exhibited heightened fear of the disease between 2020 and 2022 [Reference Ishikawa13]. One explanation for the differing results may be the timing of this study, which was conducted after the spread of the Omicron variant, known for reduced severity [Reference Wolter36]. In addition, few older adults (aged ≥65 years) [Reference Taylor37] – those at higher risk of severe illness – were included in the study sample (mean [standard deviation]: 41.1 [8.3] years old for the infection group and 39.9 [9.3] years old for the non-infection group (Table 1)). The participants also consisted of individuals who had survived the infection and were able to complete the surveys. Although no significant association was found between infection experience and hand disinfection, the increase in its practice following infection mirrored the trend seen in mask-wearing.

Importantly, the rise in perceived risk of being unknowingly affected and the estimated probability of infection may encourage greater self-protective behaviour. This result contrasts with findings from the United States, where prior infection experience was associated with reduced mask-wearing [Reference Lam15]. One possible explanation lies in cross-national differences. In Japan, compliance with mask-wearing is particularly high [Reference Murakami38]. This may reflect Japan’s strong social norms and established practices surrounding mask-wearing [Reference Murakami38]. Individuals who have experienced infection may feel a heightened sense of responsibility to prevent further infections, leading to increased preventive behaviour such as mask-wearing. Additionally, a previous study conducted in Japan in February 2021 also reported that individuals with prior infection did not refrain from social gatherings, whereas those with infected friends did [Reference Mori14]. However, that study did not account for pre-infection social activity levels, suggesting that the direction of causality may be reversed – individuals who did not reduce social interaction may have been more likely to contract the virus. Another key difference between the studies is the timing of data collection. As previously noted, this study was conducted following the emergence of the more widespread Omicron variant. Furthermore, after the vaccination campaign began in February 2021, vaccinated individuals increased their preventive behaviour until September 2021 [Reference Yamamura39]. Taken together, these studies suggest that individuals do not necessarily reduce preventive behaviour after acquiring immunity; on the contrary, they may reinforce it. Moreover, in the context of demotivation toward preventive behaviour due to the prolonged pandemic – a phenomenon known as ‘pandemic fatigue’ [40]) – experiencing infection may have led to increased risk perception and a corresponding rise in preventive behaviour. This study offers valuable insights into how shifts in infection risk perception following infection experience can influence preventive behaviour.

The findings indicate that individuals who have experienced infection develop a distinct risk perception compared to those who have not. Therefore, sharing the personal insights and risk perceptions of infected individuals with those who remain uninfected could foster greater preventive behaviour among the wider public. Disseminating such personal narratives through public information media – while taking care to avoid stigmatization – may serve as an effective risk communication strategy to promote a prevention-focused mindset in society.

This study has several limitations. First, as it utilized a cohort of online survey participants, selection bias may have occurred in the recruitment of respondents and through survey attrition. Caution should therefore be exercised in generalizing the findings. Second, infection status was based on self-reported responses. However, as infection was assessed in each survey wave, recall bias was minimized. Additionally, the number of newly infected participants in this study aligned with nationwide infection trends in Japan. Third, data on infection routes and severity were not collected. Fourth, although the infection and non-infection groups were formed using propensity score matching, the absence of random assignment limits the ability to infer causality.

Conclusion

Infection experience increased the perceived risk of being unknowingly affected. It also led to greater adoption of mask-wearing, with this perception serving as a mediator. Sharing the experiential insights and risk perceptions of infected individuals with those who have not been infected may be a promising strategy for enhancing infection prevention efforts in public contexts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268825100940.

Data availability statement

The dataset analysed in this study, as well as the full panel survey dataset and its codebook, are publicly available [Reference Miura and Yamagata41]. Study-specific processed data and analysis code will be made available on request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepL and ChatGPT solely for the purpose of possible improvement of English language expression. The authors created the original texts before using these tools. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed. Furthermore, the paper was carefully edited by native professional editors. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the publication. This article has already been registered for Preprints on medRxiv. DOI is as follows: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.05.07.25327146.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: M.M., M.Y., A.M.; Data curation: M.Y., A.M.; Formal analysis: M.M.; Funding acquisition: M.M., M.Y., A.M.; Methodology: M.M., M.Y., A.M.; Project administration: A.M.; Visualization: M.M.; Writing – original draft: M.M.; Writing – review and editing: M.Y., A.M.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Human Science Project, Graduate School of Human Sciences, The University of Osaka, and ‘The Nippon Foundation-Osaka University Project for Infectious Disease Prevention’, and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP24K21500.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests.