Young adulthood, age 18–25 years, represents a transitional life stage often characterised by unique stressors(Reference Arnett1), such as moving out of a childhood home, finding permanent employment, starting a family or enrolling in post-secondary education. These changes are often coupled with developmental, biological, neurocognitive and/or social changes and have the potential to establish a positive or negative trajectory of health across adulthood(Reference Wood, Crapnell, Lau, Halfon, Forrest, Lerner and Faustman2). Because of the pivotal life changes that occur during this period, research focused on understanding the factors impacting the health status of young adults has increased over the last 20 years.

Recent studies emphasise the high prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression and sleep problems among young adults(Reference Eisenberg, Hunt and Speer3–Reference Petrov, Lichstein and Baldwin5). For example, one study of almost 15 000 college undergraduate students found that 17·1 % reported high levels of perceived stress(3). When considering anxiety and depression, another study of over 14 000 college students found that 17·3 % reported depressive symptoms and 9·8 % reported anxiety symptoms(Reference Vankim and Nelson4). Additional work with college students found that 36 % of participants screened positive for a major sleep disorder(Reference Petrov, Lichstein and Baldwin5), including insomnia. The high prevalence of mental health challenges among young adults is problematic, as this life stage often sets the trajectory of health outcomes into adulthood.

Food insecurity, defined as inconsistent access to nutritious foods to maintain an active and healthy lifestyle(6), is a social determinant of health associated with poor health outcomes across multiple populations(Reference Banerjee, Radak and Khubchandani7). Within the USA, it is estimated that approximately 10 % of the population experiences food insecurity(8), yet among young adults, the prevalence of food insecurity ranges between 11 and 28 %( Reference Larson, Laska and Neumark-Sztainer9,Reference Nagata, Palar and Gooding10) for non-student young adults and 32–42 % for college and university students(Reference Bruening, Argo and Payne-Sturges11). These findings strongly suggest that existing research may be overlooking this unique group that is highly impacted by food insecurity.

Emerging evidence suggests a relationship between food insecurity and mental health. For example, a recent study among young adults aged 24–32 years found that food insecurity was associated with a depression diagnosis, anxiety or panic disorder, suicidal ideation and poor sleep outcomes(Reference Nagata, Palar and Gooding12). While this finding provides important early insight, exploration of other groups, particularly young adults aged 18–25 years, is needed to understand the relationship between food insecurity and mental health, as these individuals are transitioning between adolescence and adulthood. Therefore, this study aims to determine the association between food insecurity and mental health outcomes, among a diverse sample of young adults, controlling for social and demographic factors.

Methods

Data for the present study were drawn from the Promoting Young Adult Health cross-sectional online survey(Reference Buettner, Pasch and Poulos13,Reference Pitman, Pasch and Poulos14) . Young adults aged 18–25 years were recruited using the Qualtrics panel from January–April 2022(15). Qualtrics members were recruited through various methods (e.g. social media, targeted email, Qualtrics website) and validated through a third-party verification system. Qualtrics automatically dropped participants who finished in less than half the median survey completion time and/or had missing, incomplete or straight-line data. Additional participants were recruited until sufficient data were reached(15). For this study, participants were recruited from anywhere in the USA and were oversampled by racial/ethnic identity to ensure at least 30 % Hispanic/Latinx or Spanish origin and 30 % Black or African American identifying participants. All study methods and protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas at Austin. A total of 1630 young adults completed the survey. Participants missing any responses to questions included in the survey were excluded from the analytic sample for the present study (n 589), resulting in an analytic sample of 1041 (Table 1). Independent sample t tests and chi-square tests were performed to examine differences between those who were in the analytic sample (n 1041) and those who were in the original sample (n 1630). There were no differences on stress, anxiety, depression, insomnia, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic American Indian and non-Hispanic other. Significant differences were found in social status, parent status, student status, sexual or gender minority status, each measure of financial responsibility including rent, credit card, insurance and cell phone bill and participants that identified as non-Hispanic white or Hispanic.

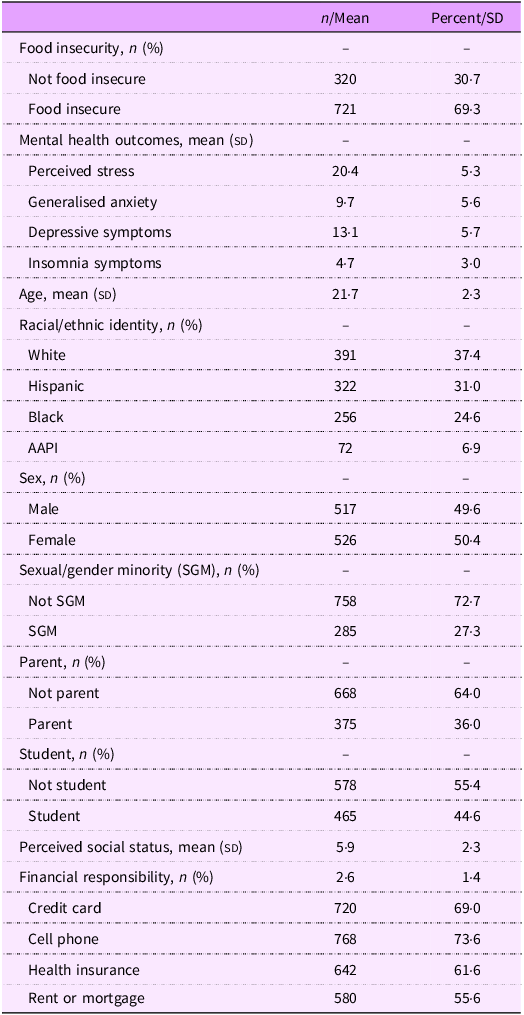

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for socio-demographic factors of young adults in the USA (n 1041)

AAPI, Asian American Pacific Islander.

Measures

Food insecurity

Food insecurity was measured using the two-item screening tool, Hunger Vital Signs(Reference Hager, Quigg and Black16). The two items included, ‘In the past 12 months, I was worried whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more,’ and ‘In the past 12 months, the food that I bought just didn’t last and I didn’t have money to get more.’ Response options included often true, sometimes true, never true, or don’t know. Responses were coded according to recommended practice from Hager et al., 2010(Reference Hager, Quigg and Black16) and Gundersen et al., 2017(Reference Gundersen, Engelhard and Crumbaugh17), where responding often true or sometimes true to either question was considered food insecure (1) and never true or don’t know to each question was food secure (0).

Mental health

Perceived stress was measured with the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale(Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein18). Anxiety was measured with the 7-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale(Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams19). Depressive symptoms were measured with the 10-item Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10)(Reference Bjorgvinsson, Kertz and Bigda-Peyton20). Insomnia was measured with three questions adapted from the insomnia severity index(Reference Morin, Belleville and Belanger21).

Socio-demographics

Socio-demographic variables included age (range = 18–25), racial/ethnic identity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic; American Indian, Asian, Black, Pacific Islander and White), sex (female and male), sexual/gender minority identity (Male, Female, Transgender, Gender Nonbinary or Other; Heterosexual or straight, Gay or Lesbian, Bisexual, Queer, Asexual or Other), parent status (yes/no), student status (full-time/part-time, non-student) and perceived social status (range = 1 (bottom) to 10 top)(Reference Ferreira, Giatti and Figueiredo22). Financial responsibility was determined with four questions that asked if the participant was financially responsible for: rent/mortgage, health insurance, cellular phone bill and/or credit card bill (yes = 1, no = 0, range = 0–4).

Data analysis

All data were downloaded from Qualtrics and imported into STATA SE 18 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the prevalence and distribution of each variable. Chi-square and t test were used to examine differences in socio-demographic factors according to food security status. Multiple linear regression models were used to determine the association between food insecurity and each mental health outcome, controlling for age, racial/ethnic identity, sex, SGM identity, parent status, student status, perceived social status and financial responsibility.

Results

Food insecurity was high among participants, with 69·3 % of the sample identifying as food insecure (Table 1). Participants reported moderate to high levels of perceived stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms and insomnia. The mean age of participants was 21·7 years old, and 37·4 % identified as white, 31·0 % as Hispanic, 24·6 % as Black and 6·9 % as Asian American Pacific Islander. Slightly over half identified as female (50·4 %). Over a quarter identified as a sexual or gender minoritised individual (27·3 %). When considering additional demographic and lifestyle factors, 36·0 % were parents and 44·6 % of participants were enrolled as students (full-time/part-time). The mean perceived social status score was 5·9. Most participants reported financial responsibility for credit card payments (69·0 %), a cell phone bill (73·6 %), insurance (61·6 %) and rent or mortgage (55·6 %).

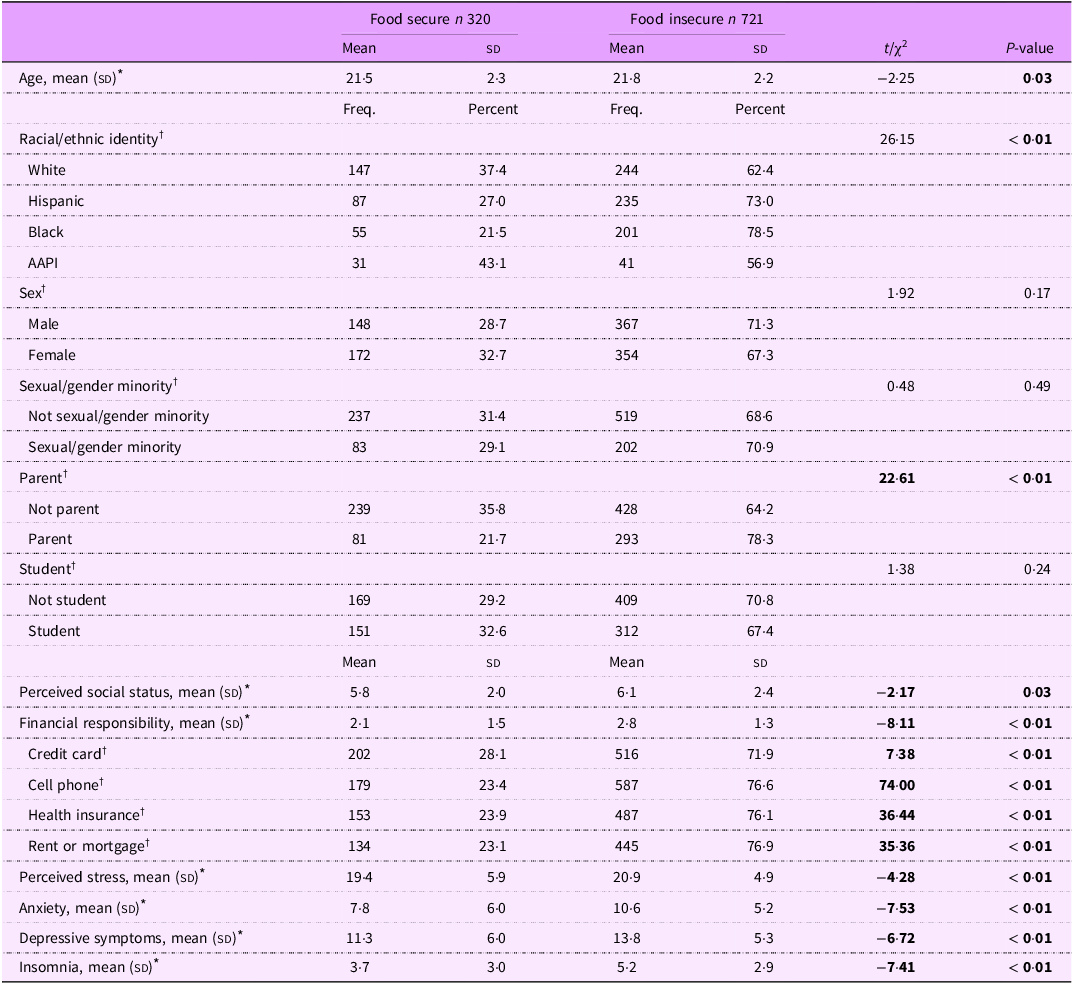

When considering food security status, differences were found among socio-demographic factors, including age, racial/ethnicity identity, parent status, social status, overall financial responsibility, as well as individual components, including responsibility for a credit card, cell phone, health insurance and rent or mortgage (Table 2). Mental health outcomes, including stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms and insomnia, also differed according to food security status.

Table 2. Difference in socio-demographic characteristics and mental health outcomes by food security status among young adults in the USA (n 1041)

AAPI, Asian American Pacific Islander.

* t test.

† Chi-Square test, significant values indicated in bold.

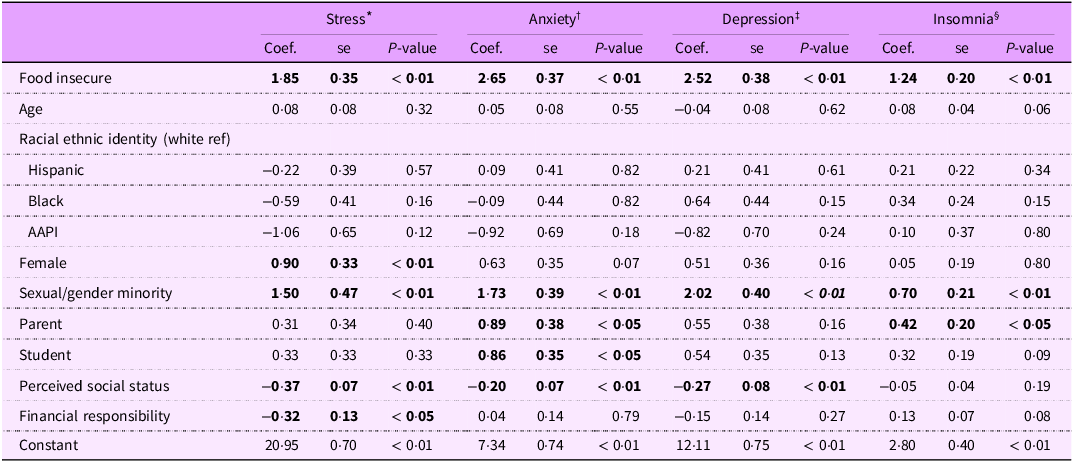

Food insecurity was significantly associated with each mental health outcome, including perceived stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms and insomnia, after controlling for age, racial/ethnic identity, sex, SGM status, parent status, student status, perceived social status and financial responsibility (Table 3). Co-variates associated with mental health outcomes included SGM status, sex, parent status, student status, social status and financial responsibility.

Table 3. Linear regression analyses of perceived stress, anxiety, depression and insomnia with food insecurity and covariates among young adults in the USA (n 1041)

AAPI, Asian American Pacific Islander.

Bold values indicate significant test results.

* Model 1: Dependent variable total perceived stress.

† Model 2: Dependent variable total generalised anxiety.

‡ Model 3: Dependent variable total depressive symptoms.

§ Model 4: Dependent variable total insomnia sleep problems.

Discussion

Food insecurity was significantly associated with perceived stress, depressive symptoms, anxiety and insomnia among our sample of diverse USA 18–25-year-olds, after controlling for all other factors. Our findings align with previous research identifying associations between food insecurity and mental health outcomes among young adults attending college or university(Reference Neal and Zigmont23) and adults aged 24–32(Reference Nagata, Palar and Gooding12). Our findings add to the growing literature highlighting the interconnectedness of food insecurity and mental health outcomes, particularly among young adults, a population at high risk of both food insecurity and poor mental health outcomes.

The mechanisms by which food insecurity is associated with mental health have not been fully elucidated; however, it is hypothesised that experiencing food insecurity may put individuals at risk for micronutrient deficiencies that are associated with increased risk of mental health conditions. For example, evidence exists that dietary deficiencies in folate, thiamin or Fe are associated with depression, apathy and altered mood(Reference Benton and Donohoe24), while nutritional insufficiency is associated with poor stress management(Reference Gonzalez and Miranda-Massari25). More recently, research suggests that dietary interventions can improve symptoms of mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), through reductions in inflammation and oxidative stress(Reference Marx, Moseley and Berk26). Given that individuals experiencing food insecurity often have reduced food access, limited dietary choices and experience multiple stressors simultaneously, research should explore how macronutrient and micronutrient intake among populations experiencing food insecurity contributes to the body’s ability to manage mental health conditions.

Previous research suggests the prevalence of food insecurity among young adults may range between 11 % and 42 %(Reference Bruening, Argo and Payne-Sturges11); however, the present study found almost 70 % of participants were food insecure in the past year. There may be a few reasons for this difference. First, data were collected during the later phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many populations saw increased food insufficiency(Reference Nagata, Ganson and Whittle27). Second, this study intentionally oversampled Hispanic and Black populations, which are often at higher risk for food insecurity(Reference Wolfson and Leung28) but are underrepresented in research. Finally, this study used the Hunger Vital Signs tool(Reference Hager, Quigg and Black16), a two-item screening measure to determine food insecurity, instead of the eighteen-item US Household Food Security Module(29). Collectively, these factors may have contributed to the higher estimate of food insecurity seen in this study when compared to other published studies. Nevertheless, this sample provides a unique opportunity to examine the association between food insecurity and mental health outcomes among a sample of diverse young adults.

While this study highlights associations between food insecurity and mental health among an understudied population, limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study was completed during later phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced both food insecurity prevalence and mental health due to disrupted food systems and social isolation recommendations. This study was completed using self-reported, cross-sectional data, which limits the ability to determine the directionality of the relationship between food security and mental health. Future research among young adults should aim to follow participants over time to determine the directionality of this relationship, particularly as new life stages and challenges occur. Research should also consider more sensitive measures of food security, as food security may be transitional or temporary for young adults due to their rapidly changing lifestyles. Finally, our sample of young adults was taken from an online panel, which although provides access to a diverse sample of young adults, is not nationally representative which may limit generalisability of the findings. However, given the limited research with young adults and the importance of including diverse samples in research, these findings provide important information about food insecurity and mental health.

The prevalence of mental health challenges among young adults has grown substantially in recent years,(Reference Eisenberg, Hunt and Speer3–Reference Petrov, Lichstein and Baldwin5) and it is important to determine what may be contributing to this increase. Experiencing food insecurity is one such factor associated with mental health, according to study results. Therefore, it may be plausible that efforts toward improving food security among young adults have the potential to improve mental health among this population. While research still needs to determine the precise impacts of food security programmes on mental health, we believe that public health practitioners, medical professionals, social service agencies and community organisations who interact with young adults should consider screening for food insecurity among their young adult clients and establishing quality referral systems to food access programmes. Although the impact is still unknown, programmes focused on alleviating food insecurity may serve as a potential mechanism for improving the mental health of young adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to report.

Authorship

N.S.P. completed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. S.A.P. supported survey creation, revised the manuscript and provided critical feedback. C.E.V. revised the manuscript and provided critical feedback. K.E.P. was responsible for survey creation and data collection, revised the manuscript and provided critical feedback.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board Committee. Informed consent was provided before participants began the online survey.