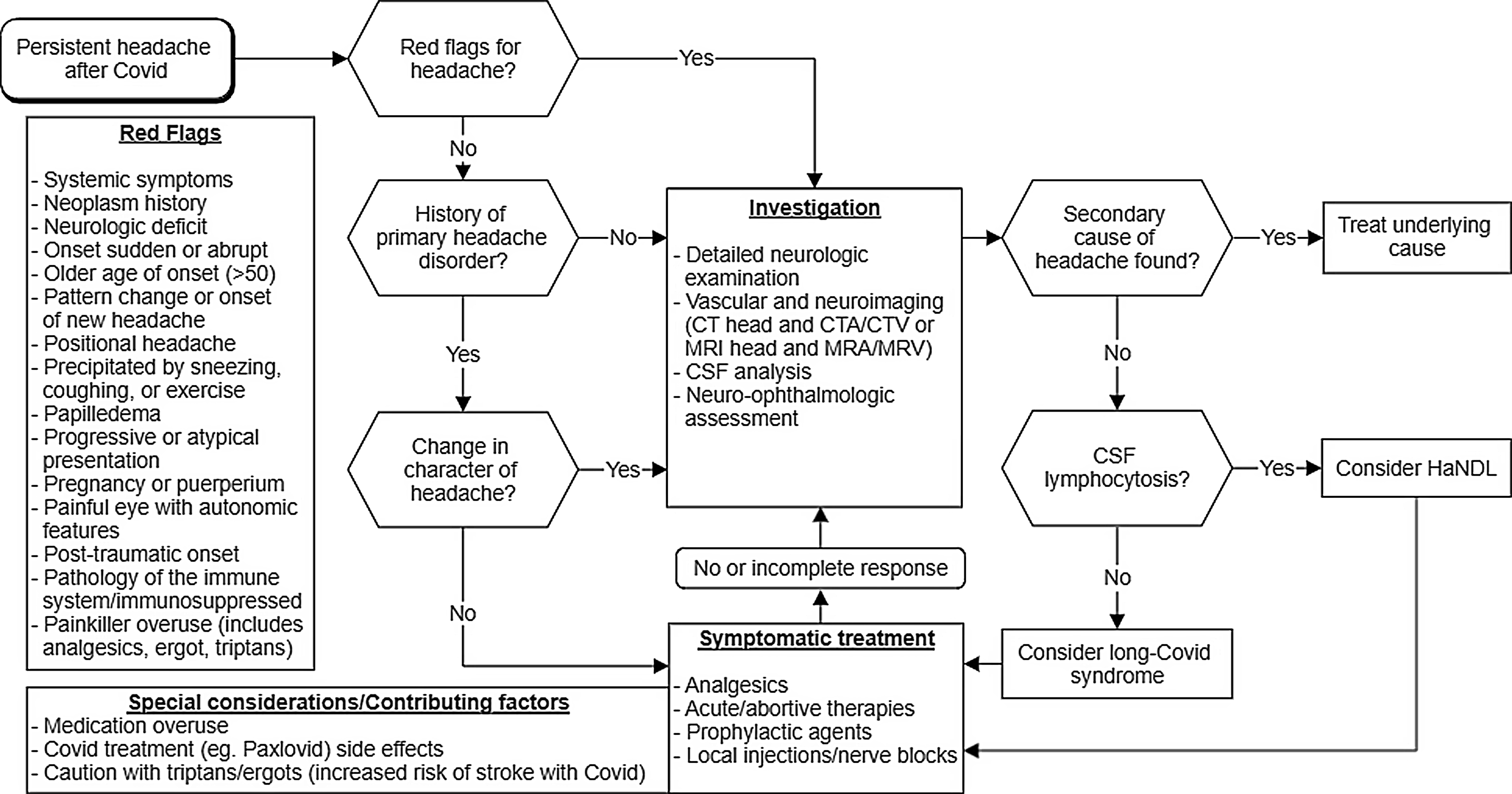

Headache is a common symptom of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during and after infection. Reference Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, Navarro-Santana and Gómez-Mayordomo1,Reference Balcom, Nath and Power2 The syndrome of headache and neurologic deficit with cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis (HaNDL) is a unique phenotype commonly associated with viral infection but with only one case reported following COVID-19 infection to date. Reference García, Isasi and Parada3 We report a second case and an approach to patients presenting with headache and focal neurological symptoms after COVID-19 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Approach to persistent headache following COVID-19. Red flags for secondary headaches adapted from the SNNOOP10 list Reference Do, Remmers and Schytz4 . CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; HaNDL = headache and neurologic deficit with cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis.

A 27-year-old non-obese woman with a history of migraine without aura for over 10 years, developed new headaches 3 weeks following a mild COVID-19 infection. She also had a recent history of acne, and depression, managed on bupropion and isotretinoin for the last 6 months. Over 2 weeks, she developed increasing holocranial, mixed pressure and throbbing, headaches lasting 5–120 minutes, occurring up to 6 times per day, without provocation. There was associated photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and occasional vomiting. These episodes were more severe and frequent than her typical migraines, and she had never had any visual or somatosensory aura previously. Twice, she experienced migratory hemibody paresthesias following headache; the first involved spread from the perioral region down the right hemibody over 30 minutes lasting a few hours, the second down the left side. The initially intermittent headaches became persistent with waxing and waning intensity and variable positional features (initially improved and later in the course worse when supine). She denied transient visual obscurations, diplopia, or pulsatile tinnitus. She presented to two separate community hospitals and both times were treated with IV fluids, ketorolac, and metoclopramide with minimal benefit. Sumatriptan, metoclopramide, and ibuprofen were prescribed but provided no pain relief. Urgent outpatient neurology opinion was requested.

Examination showed no meningismus or fever. She was alert and oriented with fluent speech. Severe photophobia made pupil and fundoscopic examination challenging although there did not appear to be papilledema. Visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye, with full visual fields. The remainder of the neurological examination was unremarkable. Given several red flag features, she was admitted to hospital for urgent investigation. Isotretinoin was discontinued.

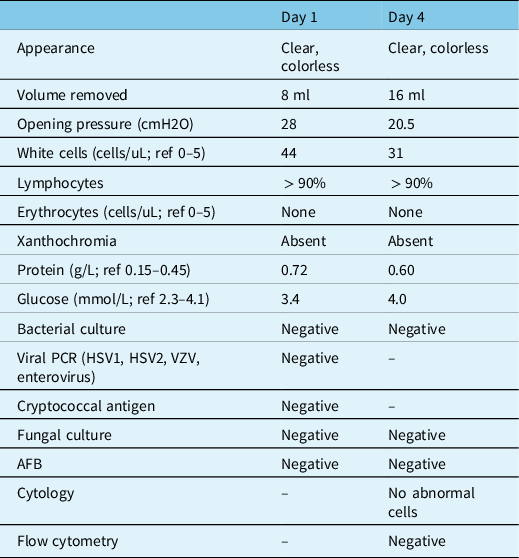

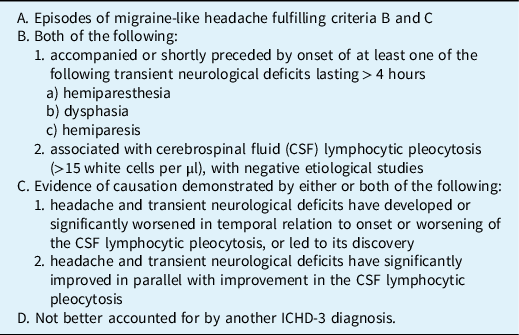

Noncontrast head computed tomography (CT) and multiphase CT angiogram head and neck showed no intracranial mass, venous thrombosis, or vascular irregularities (beading, vasospasm, or dissection). Lumbar puncture (LP) demonstrated elevated opening pressure (28 cmH2O), lymphocytic pleocytosis (44 cells/uL; reference 0–5), and elevated protein, but negative infectious studies (Table 1). Repeat LP 3 days later revealed improvement in opening pressure (20 cmH2O) and lymphocytosis (Table 1). Cytology and flow cytometry showed no abnormal or malignant cells. Her headache did not improve significantly immediately following either lumbar puncture. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spinal cord with gadolinium was normal. Optical coherence tomography and automated perimetry were normal. Her course and investigations were felt to be in keeping with HaNDL (Table 2). After 6 weeks, her headaches had gradually resolved with symptomatic treatment, and there was no recurrence of transient neurologic symptoms.

Table 1: Cerebrospinal fluid results

HSV = Herpes simplex virus; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; VZV = varicella zoster virus.

Table 2: ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for HaNDL

ICHD-3 = International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition; IHS = from the International Headache Society.

HaNDL, also known as migraine with cerebrospinal pleocytosis or pseudomigraine with lymphocytic pleocytosis, presents as a constellation of self-limited migraine-like headaches, neurological symptoms, and CSF lymphocytosis. Reference Bartleson, Swanson and Whisnant5 Headaches resemble migraines (often moderate to severe, throbbing, unilateral or bilateral, lasting hours, with nausea, vomiting, and photophobia) occurring in association with neurological symptoms (most commonly hemiparesthesia, followed by hemiparesis or dysphasia, and rarely positive visual phenomena) typically lasting from 15 minutes to 120 hours or longer. Reference Bartleson, Swanson and Whisnant5,Reference Gómez-Aranda, Cañadillas and Martí-Massó6 The course may be monophasic, but often repeated attacks occur over weeks to months. Reference Bartleson, Swanson and Whisnant5 A preceding viral illness has been associated with 25%–40% of cases, Reference Gómez-Aranda, Cañadillas and Martí-Massó6 often up to 3 weeks prior to the development of neurological symptoms. Active infection (i.e. chronic fungal or viral meningitis) requires exclusion with negative viral, bacterial, and fungal studies in serum and CSF. Antibodies against a subunit of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels have been found in some cases, supporting an autoimmune or inflammatory mechanism. Reference Kürtüncü, Kaya and Zuliani7 CSF lymphocytosis ranges from 10 to 760 cells/uL (mean 199), while elevated protein and opening pressure may also be seen. Reference Gómez-Aranda, Cañadillas and Martí-Massó6 Neuroimaging is generally normal in HaNDL but remains important in excluding structural causes of headache and focal neurological symptoms (mass lesion, hydrocephalus, cerebral edema, leptomeningeal inflammation, infarct, hemorrhage) or vascular abnormality (aneurysm, vasoconstriction, or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis). Treatment is supportive along with patient education and expectant management for this self-limited condition.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) was also considered in our case, given isotretinoin exposure and elevated opening pressure. However, IIH symptomatology generally develops soon after isotretinoin exposure (mean time to diagnosis 2.3 months) and resolves gradually over weeks to months with medication discontinuation. Reference Fraunfelder, Fraunfelder and Corbett8 Our patient had been on isotretinoin for 6 months, and symptoms seemed to resolve fairly quickly, with documented normalization of CSF opening pressure on repeat LP within days. Additionally, she had tolerated longer courses of isotretinoin previously. CSF composition in IIH should be normal, and rare cases that report lymphocytosis are often seen in association with papilledema and vision loss requiring treatment with acetazolamide or shunting. Reference Barkana, Levin, Goldhammer and Steiner9 There were no neuro-ophthalmologic or neuroimaging features in our case to suggest IIH. There have been rare reports of IIH associated with COVID-19 occurring during active infection but again with normal CSF composition. Reference Silva, Lima and Torezani10

To date, there is only one other report of HaNDL following COVID-19 infection. Reference García, Isasi and Parada3 Headache is a common symptom of both active COVID-19 infection and in the postinfectious period, Reference Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, Navarro-Santana and Gómez-Mayordomo1,Reference Balcom, Nath and Power2 with several proposed mechanisms including inflammation, cytokine release, endothelial dysfunction, raised intracranial pressure, and venous congestion. Reference Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, Navarro-Santana and Gómez-Mayordomo1,Reference Silva, Lima and Torezani10 The absence of detectable virus in inflammatory CSF of patients with neurological symptoms supports an indirect autoimmune mechanism. Reference Balcom, Nath and Power2 Furthermore, the timing of symptom onset in our case 3 weeks following infection would support a postinfectious hypothesis as described in other cases of HaNDL Reference Gómez-Aranda, Cañadillas and Martí-Massó6 . It is proposed that viral infection could trigger activation of the immune system, producing antibodies to antigens in cranial vessels and aseptic inflammation accounting for headaches and CSF lymphocytosis, and transient cerebral hypoperfusion leading to neurological symptoms. Reference Gómez-Aranda, Cañadillas and Martí-Massó6 This is also reflective of the often-monophasic course, with resolution within 3 months, also seen in our case. The most common chronic headache phenotypes following COVID-19 are migraine or tension, Reference Garcia-Azorin, Layos-Romero and Porta-Etessam11,Reference Tana, Bentivegna and Cho12 which may be part of a wider spectrum of the so-called “long-Covid syndrome” which can also include fatigue, rash, respiratory symptoms, and mental health and cognitive symptoms including anxiety, depression, and insomnia. A monophasic course with focal neurological symptoms atypical for migraine aura makes HaNDL unique. Recognition of this uncommon syndrome is important and should be included in the differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with headache and focal neurological symptoms after viral illness including COVID-19. However, it remains important to exclude other potentially serious conditions presenting in a similar fashion.

Disclosures

S. Marzoughi reports no disclosures. A. Plecash reports no disclosures. T. Chen reports no disclosures.

Statement of authorship

SM: drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data. AP: drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content. TC: drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept and design; analysis or interpretation of data.