Introduction

In conflicts which involve the participation of armed groups, counterterrorism has mostly led to either the groups’ end or their reintegration with the state.Footnote 1 Traditionally, counterterrorism signals the legitimisation and normalisation of certain power, political, and institutional practices.Footnote 2 Even as political elites have a range of responses to choose from when dealing with domestic instability, engagement with repression as a tactic of containment is ineffective as a long-term solution to addressing grievances.Footnote 3 There is also a parallel line of empirical research that suggests that governments may choose to fight an insurgency militarily, by providing public goods and services to motivate the community to share information, which in turn enhances the effectiveness of military counterinsurgency.Footnote 4 Despite this, the questions remain: how have the groups in India Administered Kashmir withstood the decades-long onslaught of counterterrorism? Additionally, how do these groups, in particular the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), and the Hizbul Mujahideen (HM), continue to mobilise support and recruitment for their cause?

It is useful to look into the configuration of historical precedents, existing resources, and institutional arrangements which enable the development and spread of such protest movements.Footnote 5 It is worth noting that political cleavages and opportunities vary from one conflict to the next, given that each is anchored in different sociocultural conflict structures.Footnote 6 Beyond the scope of empirical and theoretical research, this provides nuance to understanding policy choices and commensurate responses to terrorist recruitment and violence. To that effect, Kashmir offers a unique case study. First, aside from the issue of historic contestation, ‘opportunities’ in Kashmir are marked by the absence of a regional political class and democratically elected representation.Footnote 7 Second, such opportunities are underscored by coercive counterterrorism policies from India. These policies in turn shape bystanders’ and groups’ recruitment and retaliation narrative accordingly. The next section discusses existing research, followed by the validity of positioning Kashmir as a case study. Then we offer the methodology used to derive our findings. The article examines three groups operating in Pakistan and/or Kashmir: Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), and Hizbul Mujahideen (HM). While these groups have been the subject of existing research, they remain empirically understudied in terms of their responses to counterterror policies, compared to other similar organisations. The research leverages original data from field interviews and digital ethnography using a semi-encrypted application, Telegram, as well as descriptive data from the South Asia Terrorism Portal.

After that, we present an argument for how coercive counterterrorism enables violence in Kashmir. Our research reinforces the understanding that transnational terrorist organisations often operate in environments characterised by political instability, social fragmentation, and economic deprivation. In such contexts, civilian support becomes a crucial resource for militant groups, facilitating recruitment, operational logistics, and the maintenance of high morale.Footnote 8 We therefore argue that despite this dependence on civilian constituencies, states often resort to repression and coercive counterterrorism strategies, which, paradoxically, do not eliminate popular support for groups. Instead, these coercive strategies may inadvertently legitimise the need for these groups among their members and sympathisers, while simultaneously raising the costs of inaction for non-involved members. This analysis seeks to explain the complex dynamics between a state’s coercive actions, civilian perceptions, and terrorist groups actions in the face of this type of counterterrorism.

Literature: Counterterrorism, coercion, concession

In absolute terms, counterterrorism is understood to leverage ‘hard power’ through human intelligence, legal practices, institutions of policing, and military intervention.Footnote 9 The literature on how terrorist groups end credits five broad reasons for the end of groups: better policing and intelligence, aggressive military force, splintering and competition within the terrorist group, peaceful political inclusion, and, in rare cases, victory by the group itself.Footnote 10 While the decline of terrorist groups is equally a function of external and internal dynamics,Footnote 11 focusing on their internal feuds and interpersonal rivalries offers additional insight into the groups’ vulnerability and provides clues on how to best unravel or collapse the groups.Footnote 12 Literature also suggests that repression and direct state action, group burnout, loss of a leader, unsuccessful generational transition, loss of popular support, and emergence of new alternatives could also lead to the natural decimation of a group.Footnote 13 Contrarily, states with aggrieved minority populations may find those civilians less inclined to cooperate with state counterterrorism representatives.Footnote 14 In the process of counterterrorism, the use of coercive repression or offer of concessions influences dissent.Footnote 15 In this specific context, concessions may be understood as softer approaches, with states appealing to families of mujahideen, as well as legislation aimed at containment. Ironically, when states restrict rights or try to curb popular dissent, this might generate sympathy for the group and further legitimise the militants.Footnote 16 This is typical of Kashmir, where contestation and the presence of decades-long grievances has now swayed popular support in favour of groups that ostensibly champion the cause of the people against Indian authorities and their interventions.

One aspect of counterterrorism also focuses on the efficacy of strategic decapitation, more commonly known as targeted assassination.Footnote 17 Tilly suggested that the struggle for power is often a dyad between two groups (terrorist groups and the state), and terrorist group behaviour is dictated by the scale of repression or the degree to which the state might facilitate its existence. He adds that the scale of repression raises the costs of collective action and overall mobilisation. States might focus on disrupting the group by making communication inaccessible, freezing material and logistical resources, forbidding assemblies, penalising sympathisers, or killing and arresting its leaders.Footnote 18 The last is reflected in the Taliban’s strategy, where it has extensively used targeted assassination to eliminate rivals in North Waziristan, killing over 50 people in 2020 and 2019 (Combined) including tribal leaders, activists, and government officials. Despite the routine occurrence of assassinations, these attacks are rarely investigated, and few of the perpetrators are ever charged.Footnote 19 This article, however, argues that along with coercive counterterror strategies, non-coercive approaches, such as enhanced intelligence gathering, spur increased coercive kinetic military action. At the same time, in conflicts marked by high levels of violence (where groups challenge the legitimacy and authority of the state), any form of police control is unlikely to alter the shape and outcome of protest.Footnote 20 ‘While targeted killing provides states with a method of combating terrorism, and while it is “effective” on a number of levels, it is inherently limited and not a panacea.’Footnote 21

Better counterterror policies require people’s participation and their rejection of political violence, but the instruments of state power such as the police or military invariably inflame grievances and amplify the root causes of violence.Footnote 22 In order for terrorist groups to end, state actors need to facilitate the disengagement process, through a comprehensive anti-terror strategy.Footnote 23 If militants have nowhere to run, they have no incentive to stop fighting. Recent counterterror initiatives have emphasised the need to channel frustration and offer off-ramps that allow people to mobilise but in pro-social rather than anti-social ways.Footnote 24 Although critics of the ‘soft’ power approach argue that it is an ineffective strategy for lasting stability,Footnote 25 coercive deterrence is insufficient to foster permanent disengagement from terrorism,Footnote 26 even in the case of Kashmir, where government retaliation focused primarily on an armed response.

An alternate response to applying military and political power,Footnote 27 focusing on granting political concessions or peaceful outlets for change, allows the state to reduce hostilities and end conflict by addressing the underlying root causes.Footnote 28 As Cronin claims, ‘the question of how terrorist groups decline is insufficiently studied, and the available research is virtually untapped’.Footnote 29 Previous attempts to explain terror group persistence and decline focused on strategic choices made by groups. While some groups do in fact end (Jones and Libicki suggest that most fail),Footnote 30 there are a handful of cases in which terrorist groups become more violent following the promise of concessions. This is because moderate factions who consent to concessions exclude the more extremist elements, creating incentives to splinter. Concessions create the space for the participation of former terrorists and might improve the state’s counterterror capabilities and strategies, while these same concessions allow former rebel groups to adapt to the more inclusive state policies and peace discourse.Footnote 31

This article challenges conventional wisdom on the efficacy of counterterrorism, including the offer of concessions. Across regions with protracted conflict and repression such as Kashmir, militant actors are unlikely to adopt non-violent approaches. The pattern is true also for bystanders who might be on the fence. This process encourages them to sympathise with the movement. Many forms of control, therefore, especially those considered repressive and illegitimate, exacerbate a sense of injustice. To the actor, this can heighten the perceived risk of inaction, thereby spurring greater violent radicalisation in groups which are most at risk of police violence.Footnote 32 Therefore, while (repressive) state control strategies initially appear to be directed at controlling protest strategies, they affect movement actors and therefore, organisation models within movements, where eventually the organisation prefers to operate underground.Footnote 33 We therefore argue that heightened repression does not deter but rather, under specific conditions explored below, enhances recruitment into terrorist groups. As such, while coercive counterterrorism might appear effective in curtailing recruitment into terrorist groups in the short run, over time groups adapt to such policies, thus rendering counterterrorism ineffective in curtailing terrorist groups, especially those who benefit from state sponsorship. This hypothesis is examined in the following sections.

Case examination: Counterterrorism in Kashmir

India Administered Kashmir (henceforth, Kashmir) challenges debates about the efficacy of counterterrorism policies and how terrorist groups end. While the prediction that 95 per cent of terrorist groups fail in the first two years holds true generally, groups in Kashmir flout assumptions about the ephemeral boundedness of such groups. The terrorist groups in Kashmir survive despite sophisticated Indian counterterrorism policies.Footnote 34 This is where a question can naturally flow about why groups indigenous to Pakistan (LeT and JeM) or those ethnically Kashmiri such as the HM even need to rely on the local population in Kashmir to survive there. For one, even as the local Kashmiri population forms the recruit base for these groups,Footnote 35 former HM members stated in their interviews with the author that ‘especially since LeT and JeM were foreign groups, they relied very heavily on local guides, families for their lodging and ration for as long as they needed … and of course intelligence tip-offs before an Army raid’.Footnote 36

The groups’ longevity can also be partially explained by their internal mechanisms, which enable them to adapt to wide-ranging Indian counterterror strategies, as the paper further explains. Furthermore, India’s offers of concessions have different implications for civilians, terrorists, and secessionist groups. This is especially the case when coercive counterterrorism masquerades as concessions. The research on counterterror and group responses in Kashmir remains understudied and suffers critical theoretical and empirical gaps. This is partially a reflection of access problems and a lack of primary research in the local languages. The article, whilst assessing the efficacy of coercive Indian counterterror initiatives and concessions, provides a nuanced understanding of how terrorist groups rebrand themselves, reshape old recruitment policies, and render irrelevant deterrence mechanisms for their long-term survival.

Kashmir offers an ideal case study to measure group resilience, to chart the shifting evolution of state counterterrorism policies, and to assess how groups adapt to them. This pattern of violence, adaptation, and further violence created an almost seamless cycle of recruitment and survival during the period under review from 1989–2022. Even though Kashmir remains one of the most militarised zones in the world,Footnote 37 many counterterrorism practices have failed to contain terrorist recruitment. In a recent shift in tactics towards integration, the Indian central government offered a comprehensive policy of inclusionFootnote 38 and regional autonomy, and offered more transparent political structures despite tight and secretive counterterrorism policies, aimed at preventing recruitment and driving a wedge between groups and their larger constituency from which they recruit.

This article examines the period from 1989 to 2022, and how three transnational terrorist groups, LeT, JeM, and HM, have successfully circumvented counterterrorism policies – ensuring their ability to recruit and radicalise a new generation. All three are under the patronage and sponsorship of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).Footnote 39 While the LeT is led by Hafiz Saeed, JeM is led by Maulana Masood Azhar, and the HM is led by Syed Salahuddin. By precluding peaceful engagement with the central government, they have guaranteed their continued relevance and ensured their longevity. It is worth noting here that the HM, which is essentially the militant wing and sectarian subset of the Jamaat-e-Islami,Footnote 40 did not originally start out as a typical transnational organisation, like the LeT or JeM. Instead, in the 1990s, Salahuddin was granted Pakistan’s unconditional backing.Footnote 41 In diverging from the LeT or JeM, the HM operates exclusively in Kashmir. Much like the LeT and JeM, their training camps and even their ‘emir’ remain in Pakistan, hence controlling the militant group’s operations across the border, into neighbouring Kashmir.

The Indian government’s focus on counterterrorism has been twofold: to end the operations of the groups in the region and to eliminate (or at least limit) the population’s incentives for mobilisation.Footnote 42 The latter can be accomplished in a variety of ways, including addressing the underlying grievances or the psychological need for significance.Footnote 43 Counterterrorism officials tend to conduct a cost–benefit analysis strengthened by three goals: preventing future attacks; limiting the scope and scale of violence (by preventing organisations from recruiting or by thwarting the organisation’s objectives); and the eventual elimination of the organisation or the demobilising of members, i.e. how terrorism ends.Footnote 44 The governments understand that local ‘buy in’ is crucial for success, and there is a need for a cohesive strategy in which the group’s supporters have ‘skin in the game’. An overly aggressive counterterrorism approach increases support for the groups and often results in increased radicalisation and mobilisation.Footnote 45 This is the classic explanation for why militant groups target civilians: the goal is to force governments to overreact. To quote Gorriti on the Shining Path in Peru, ‘the goal was to provoke blind, excessive reactions from the state … Blows laid on indiscriminately would also provoke among those unjustly or disproportionately affected an intense resentment of the government.’Footnote 46

To that end, not only does aggressive counterterrorism have implications for human rights, but it can also inflame sympathisers, increasing their willingness to mobilise and engage in violence.Footnote 47 While this policy raises questions regarding why states engage in repressive crackdowns against terrorists to begin with, the argument holds that states face a trade-off in their counterterror choices between efficacy and the desire for revenge. Although it is essential for national security, aggressive counter strategies unintentionally cause the population to tacitly support terrorist groups, assuming (from the violence) that the state is unconcerned with the safety, health, and welfare of the civilian population, thereby exacerbating resentmentFootnote 48 and amplifying the relevance of terrorist groups.

Methodology

To test the above-mentioned hypothesis, the research examines the LeT, JeM, and HM.Footnote 49 We draw on field research and original qualitative data collected from semi-structured interviews (n = 22) of respondents across India Administered Kashmir and Pakistan collected by the lead author. All respondents and locations have been anonymisedFootnote 50 for the study and assigned pseudonyms – ‘Respondent 1–22’. As a result, the names and locations of respondents have been removed from the study due to security concerns to both the respondents and the author. Four groups of respondents were involved in the study: (a) intelligence, security, and counterterrorism operatives (n = 7); (b) former mujahideen group members (n = 6); (c) Kashmiri civil society members and family members of slain mujahideen with privileged insights into the phenomenon of jihadist violence (n = 5); and (d) Pakistan-based civil society members associated with the LeT and JeM (n = 4).Footnote 51 While one of the authors encountered some methodological limitations due to restricted access in rural Kashmir for security and safety reasons, for triangulation purposes, additional data was supplemented using Telegram groups (n = 16) operated by the representatives of the militant groups in Kashmir and Pakistan. While the interviews (in-person and virtual – given security and travel restrictions for Pakistan and rural Kashmir) were conducted from January to June 2022, following the University of York's Ethical approval for candidate number 207017941, the Telegram Data was collected from April to October 2022. The findings were analysed through principles of Thematic Analysis (TA), using NVivo.Footnote 52

Findings and results

In Kashmir, Indian counterterrorism included both coerciveFootnote 53 and non-coerciveFootnote 54 counterterrorism policies (carrots and sticks) intended to enhance national securityFootnote 55 and ensure public safety,Footnote 56 peaceful dialogue, discussions,Footnote 57 and legislation aimed at regional integrationFootnote 58 and development.Footnote 59 However, no concrete programme for de-radicalisation exists for this region. While coercive and non-coercive counterterrorismFootnote 60 was intended to enhance containment,Footnote 61 it actually shaped terrorist groups’ strategies for survival, exacerbated civilian resentment, and solidified the perpetuation of jihad in the region. Each counterterrorism programme was met with a corresponding response from civilians and terrorist groups – ranging from peaceful to violent protest, public demonstrations, and stone-throwing,Footnote 62 by people aged 14 to 70.Footnote 63 Groups subsequently increased recruitment in the aftermath of counterterrorism operations. This can be divided into three broad variables of analysis: (a) state perceptions and political counterterrorism and the corresponding response, i.e. how India perceived the Muslim civilian population and devised policies of containment; (b) intelligence and spying, i.e. less coercive aspects of counterterrorism and how groups inoculated against it; (c) mathematics of terror and kinetic action, i.e. coercive and armed counterterrorism that enabled recruitment.

State perceptions and political counterterrorism

Two factors shaped non-coercive political and policy counterterrorism and their execution: (a) state perception of civilians aiding and abetting terrorists and (b) policies, legislations, and geopolitical sanctions. A proclivity for more violent repertoires of protest and subsequent recruitment into transnational terrorist groups in Kashmir was found to be a key function of the Indian state’s perception of civilians. The first step towards shaping this perception was extensive militarisation of Kashmir from 1990,Footnote 64 whereby civilians were subject to random checks and searches on the basis of suspicion.Footnote 65 Simultaneously, both coercive and non-coercive counterterrorism and national security laws upheld the Indian state and its security apparatus’s perception of civilians, even once regimes changed at the Central level.Footnote 66 Not only did it exacerbate civilian insecurity, but the perception of civilians as potential mujahideen (terrorists) became more deeply entrenched.Footnote 67

Beyond mere perception, respondents concurred that the Indian state’s counterterrorism historically included coercive and persuasive elements. Duschinski asserts that India’s military policies in Kashmir, since the outbreak of the insurgency and the birth of the Hizbul Mujahideen in 1989, has been rooted in ‘violent nationalism, and jingoistic militarism … through a moral performance of national security in the Kashmir Valley’.Footnote 68 Through the lens of this national security concern, state violence was legitimised as ‘necessary’ for law and order in the region,Footnote 69 underpinned by the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA).Footnote 70 Between the late 1990s and 2004, counterterrorism exercises veered towards non-coercive norms which could be aimed at ‘winning hearts and minds’ through inclusive exercises such as Operation Sadbhavna.Footnote 71 In the post-2014 period, leading up to the revocation of Article 370 in 2019, the state’s execution of counterterrorism pivoted back to coercive.Footnote 72

The late 1990s was very important. It was the commencement of the humanisation of conflict. We started looking at it less kinetically although we were still counting terrorists killed, we started looking at other things … at the social domain, development, education, national integration. But the 1999 Kargil War changed everything, and by 2007 local resentment had peaked and they just wanted security forces out of Kashmir. Today there’s a soldier at every yard … and it’s heavy handed.Footnote 73

As such, ‘non-coercive’ counterterrorism policies post-2014 continued to focus on searches of the local civilian population and invasive checkpoints.Footnote 74 The deterrent presence of armed personnel in public, including outside mosques to pre-empt civilian resistance in the forms of stone-throwing or large demonstrations,Footnote 75 was also complemented by the state ‘randomly slapping PSA (public safety act) on local people, journalists, and activists’,Footnote 76 ostensibly to pre-empt civilians from joining forces with mujahideen or groups. This pre-emption was aided by the presence of legislation and laws which enabled forces to search and/or place individuals under arrest on the basis of suspicion.Footnote 77 As one of the counterterrorism officials summed up:

Around 2007 onwards this had the opposite effect. These feelings that we are all just treated like terrorists … this erupted. There was so much hatred among civilians against forces that we actually thought that if forces move back a little, things will be fine. But that didn’t happen and instead protest took the form of stone pelting. During search operations people would be taken out of their homes in the cold (in the) middle of the night … even forcefully. And civilian homes were burnt after an encounter just to be sure. An entire generation of kids grew up seeing all this. That was very damaging to any counterterror effort. Even those who were neutral earlier turned against us.Footnote 78

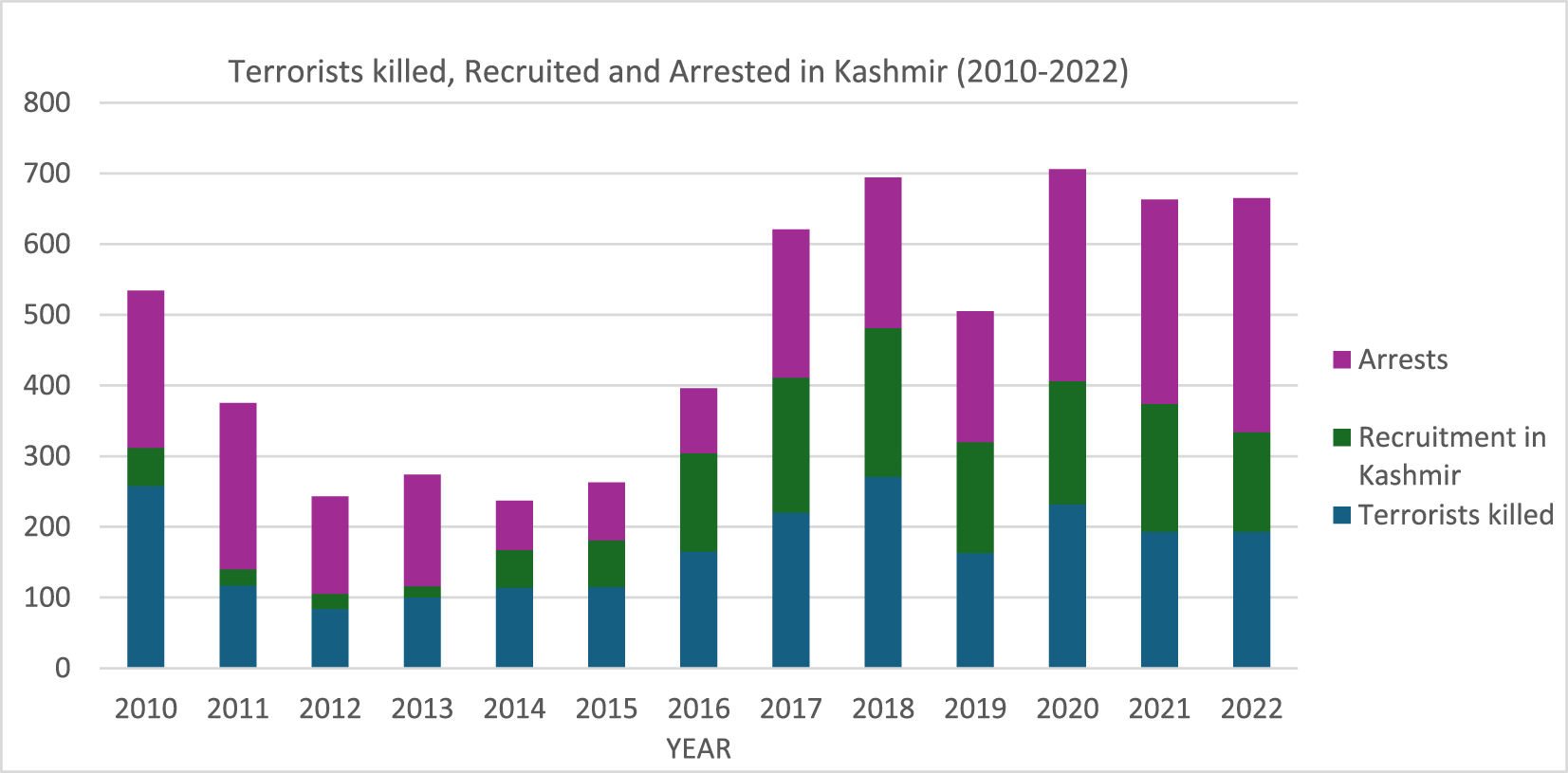

It was observed that these approaches were consistent with global approaches to counterterrorism that substantially reduced fundamental human rights, an expansion in the state’s authority on privacy laws, and arresting suspects and detaining them without charge.Footnote 79 Remarkably, the less coercive anti-terrorism policies – which were not punctuated by kinetic action by security forces – consequently led to more profound entrenchment of resentment and grievances. Conflating civilians with active militants was underpinned by the ‘arbitrary’ execution of such policies.Footnote 80 Since shaq (suspicion) was sufficient for state counterterrorism officials to enforce such policies, civilians often became collateral damage in the process of prosecuting terrorists and their accomplices – eventually turning even those who favoured a peace process against the state.Footnote 81 This naturally predisposed Kashmir’s civilians to sympathise with terrorist groups who would ostensibly champion their cause,Footnote 82 keeping recruitment consistent despite coercive and legislative counterterrorism approaches between 2010 and 2022 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Terrorists killed, recruited and arrested in Kashmir (2010–22). Source: Calculations based on data from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) and the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs annual reports.

On a macro level, counterterrorism policies encompassed economic and diplomatic sanctions against Pakistan.Footnote 83 While geopolitical sanctions focused on imposing proscriptions on the leadership (emirs) of groups,Footnote 84 these were rarely effective in supressing recruitment. Sanctioned leaders continued to operate from within ‘house arrest’. All organisational decisions regarding groups’ shura council and allocation of funds were controlled by the emir,Footnote 85 remotely, while being officially enacted by the de facto emir.Footnote 86 The immediate aftermath of sanctions and non-coercive counterterrorism policies slowed the influx of local Kashmiri youth into terrorist groups.Footnote 87

However, locally in Kashmir, episodes of civilian violence as well as individuals’ experiences gained momentum, as youth perceived prevailing policies as too aggressive and too repressive.Footnote 88 There were no reintegration opportunities for the families of mujahideen (neither those serving nor slain).Footnote 89 Simultaneously, Indian counterterrorism initiatives that included unconscious negative perceptions triggered youth to seek out (more) violent and extremist repertoires of protest and action.Footnote 90 Not only was there an absence of equal opportunities and fundamental rights, but terrorist groups also reframed participation and recruitmentFootnote 91 by altering recruitment strategies.Footnote 92 Stringent screening and training criteria were eliminated in favour of quicker induction, rudimentary training by district commanders,Footnote 93 and a condensed turnaround time for deployment and counter-attacks.Footnote 94

Intelligence and spy frameworks

Terrorist organisations attract new recruits in a variety of ways and often in response to the very state policies intended to counter the group’s mobilisation efforts.Footnote 95 Kashmiri civilians perceived Indian counterterrorism strategies with both scepticism and resentment. India’s use of coercive and kinetic counterterrorism was extensive.Footnote 96 The data found that coercive counterterrorism was split between surveillance and intelligence, on the one hand, and kinetic action (discussed in the next section) on the other. Intelligence gathering was centred on persuading civilians to provide information on terrorist movements, hideouts, structures, and operations,Footnote 97 with the aim of limiting recruitment or thwarting a nascent attack.Footnote 98

Indian counter-intelligence units relied on tactical intelligence (TACINT),Footnote 99 which concentrated on intercepting telephonic or social media communication between mujahideen, which then informed the units’ on-ground operations.Footnote 100 Because terrorist groups relied so heavily on social media and chat software to communicate or disseminate propaganda,Footnote 101 intelligence units traced the phone applications (apps) used by the mujahideen and their commanders. Their technology tracked the location and origin of communications within a radius of 50 metres, followed by manual searches of the area while India’s information and broadcasting ministry blocked their broadcasts.Footnote 102 Inputs from TACINT traced and pre-empted missions by mujahideen; however, this method was also easily circumvented by groups.Footnote 103 Not only did groups set up parallel networks,Footnote 104 but they did so also on the encrypted channels, making it significantly more challenging for intelligence units to intercept and track the groups’ digital footprints.Footnote 105

After 1998, intelligence comprised mainly of Human Intelligence (HUMINT), to supplement TACINT, in case the latter failed.Footnote 106 To ensure reliability of HUMINT and to protect sources against detection by terrorist groups, sources were only in contact with a single handler within a counter-intelligence unit.Footnote 107 To guarantee secrecy, message inputs were conveyed to a handler through the phone, without ever travelling to the agency.Footnote 108 The reliance on HUMINT was fraught, as sources could get caught by the groups or agents could betray them and double-cross the agencies.Footnote 109 The intelligence units created a system of consistent incentivisation.

The biggest thing is to maintain secrecy of source. The second is incentive. Are you working for money or job or material? When they ask for something then you are bound to fulfil it. Their rates are very high now – earlier it could be just a rum bottle. Now rates differ according to the levels of informers and information. Foreign militants, commanders etc … and their rates start at a few hundred thousand. Sources are not just local sources, and you can have sources in Pakistan as well and then they have to be paid as well.Footnote 110

At the same time, HUMINT was bolstered by female operatives conveying intelligence. Cultivating women for intelligence was based on the premise of ‘passion’, where women were subject to forced marriages or liaisons with mujahideen.Footnote 111 In such cases, the intelligence agencies tracked them.Footnote 112 The incentives included protecting the family against the mujahideen. Consequently, mothers or sisters provided information about a mujahid’s whereabouts. While women provided ‘an extremely strong tool in intelligence generation’,Footnote 113 sentiments of passion and vengeance were cautiously harnessed by counter-intelligence (CI) units. In the instances where a mujahideen was seeking refuge in one village and rumours of his dalliances with local women were rife, CI units traced ‘the woman who fancies him and he is not returning her affection … or the mother of a girl who was opposed to the alliance’.Footnote 114 In either case, CI units traced and cultivated the ‘aggrieved woman’ in order to gain information, given the extent of her incentive to alert the forces as to the whereabouts of the mujahideen.Footnote 115

Despite the first author’s efforts, no additional information on intelligence gathering was possible, primarily because of national security. At the same time, intelligence gathering was combined with kinetic actions such as armed strikes after identifying the location of mujahideen. Following a check on the accuracy of the ‘tip’, the nearest army unit, paramilitary camp, and the special operations group (SOG) were alerted to seal the village or locality where the mujahideen was found to be hidden. Should the mujahideen not surrender, an encounter would subsequently be carried out.Footnote 116

Conventionally, police and intelligence units collected information on terrorist groups, penetrated cells, and arrested members, hoping to end a terrorist group.Footnote 117 While a more stringent form of law enforcement or intelligence might lead to a reduction in militant activities and recruitment and disrupt networks,Footnote 118 Kashmiri transnational groups quickly adapted to intelligence networks and counterterrorism efforts. Groups not only restricted the movements of their cadres within KashmirFootnote 119 but also disbanded compromised command centres and temporarily suspended mujahideen infiltration into Kashmir and exfiltration of their members into Pakistan.Footnote 120 Groups issued strict diktats to mujahideen operating transnationally or in Pakistan, in the hopes of weeding out anyone suspected of being an informant.Footnote 121 At the same time, groups reconsidered their outreach, targeting women to increase their numbers but perhaps also, in part, to prevent them from defecting to and aligning with Indian intelligence.Footnote 122 Conscious of the damage of spying, groups issued warnings to not just to loyal mujahideen but to those suspected of double-crossing the group:

What is Mukhbiri (spying)? It’s not only an information given to Murtadeen and Mushriqeen (disloyal people) by specific Informers. It is also the input given by those people in resistance leadership who have loopholes in their strategies … The Mujahedeen at this moment of time should only focus on exposing and punishing the spies so that the lives of their brothers should be protected. The day-to-day encounters are only due to human intelligence. Dismantling spy network is the only way to survive in the guerrilla warfare. Do not trust any application as none of the application is encrypted and they leak data to intelligence agencies.Footnote 123

To safeguard against such detection, transnational district commanders also conducted in-depth video footage analyses of encounters with Indian security forces providing mujahideen with extensive debriefs on deception strategies and identifying weaknesses in their strike operations prior to operations.Footnote 124 While strike action and encounters (clashes) with Indian security were often the result of intelligence failures or tip-offs,Footnote 125 using mujahideen experience, the groups evaluated and analysed sources and methods of past performance, while drafting best practices for averting detection and minimising losses during future encounters.Footnote 126

Mathematics of kinetic action

The shift to coercive counterterrorism practices was signalled when the Indian state changed its framing from ‘counter-insurgency’ to ‘counterterrorism’ in the late 1990s. Despite the fact that any definitional distinction between the two terminologies is nebulous,Footnote 127 for the Indian security apparatus, especially the army, the former represented action against freedom fighters targeting security personnel and government assets.Footnote 128 The latter encompassed an encroachment by the group on the civilians in KashmirFootnote 129 and relied on civilian participation in enabling or abetting terrorist operations there.Footnote 130 The somewhat less invasive ‘hearts and minds’ approach using national integration and humanitarian methods was replaced with kinetic approaches beginning in 1999. The outbreak of a border skirmish between India and PakistanFootnote 131 marked the final transition from ‘counter-insurgency’ to ‘counterterrorism’. In adapting to the latter, coercive counterterrorism practices were based on the ‘mathematics of terror’, in which the focus was to reduce the absolute number of terrorists operating within KashmirFootnote 132 and to maintain annual figures below the threshold.Footnote 133

Given that ‘you cannot eliminate as many as are created’,Footnote 134 calculation and target setting were drawn out in a manner where, if 2,000 terrorists were deployed into Kashmir or were homegrown, the target was to then kill and eliminate about 1,400 of them, such that 600 remain. This became critical, especially in 2001, when the supposed number of mujahideen in the Kashmir region was pegged at approximately a quarter of what it had been in 1990. With the counterterrorism and security apparatus having reduced that figure to about 180–200, the new target was revised so that the absolute number of mujahideen never surpassed 200. Kinetic action was then aimed at reducing the strength, ‘because total elimination is not possible’.Footnote 135

The first step towards a more aggressive strategy manifested in the security apparatus setting up ambushes along the boundary between the two countries,Footnote 136 designed to prevent an influx of terrorists into Kashmir.Footnote 137 Pakistan would conduct shelling exercises to provide cover for mujahideen infiltrating into Kashmir.Footnote 138 Militarisation of the region in the early 1990s had placed security personnel in every district in the region, thereby enabling the army to conduct invasive searches of individuals or locations based on nothing more than suspicionFootnote 139 Coercive counterterrorism was expressed in a three-pronged approach involving the army, regional police forces, and a central paramilitary force. Local police shared tactical or human intelligence about the presence of possible mujahideen in local villages with the nearest army and paramilitary post.Footnote 140

The first stage followed an intelligence ‘tip’ and resulted in ‘cordon and search operations’ (CASO) of the area.Footnote 141 Villages where mujahideen were believed to be hidden would be cordoned off and their inhabitants evacuated and questioned, with ‘people … taken out of their homes in the cold (in the) middle of the night … even forcefully’.Footnote 142 Depending on the extent of cooperation from local civiliansFootnote 143 and whether mujahideen surrendered, an armed encounter might ensue.Footnote 144 Following the elimination of the mujahideen, hideouts (which were identified as homes of civilians in the villages) were then set ablaze to ensure that no mujahideen might be hiding inside.Footnote 145 Once these steps were completed, security personnel conferred their findings to the commanding officers and adjudicated which inhabitants merited investigation for harbouring terrorists, which was severely punished.Footnote 146 This was inherently aimed at isolating the region against the proliferation of terrorists – both homegrown and foreign. It however, failed to effect change at the grassroots level, where resentment were dominant. An example of this sentiment was articulated by one of the respondents: ‘There was so much hatred among civilians against forces that we thought that if forces move back a little, things will be fine. But that didn’t happen and instead protest took the form of stone pelting. An entire generation of kids grew up seeing all this. That was very damaging to any counterterror effort. Even those who were neutral earlier, ultimately turned against us (Indian counterterrorism forces).’Footnote 147

Response by terrorist groups: Attrition, sympathy, and adapting

Violence stems from a reaction to indiscriminate repression and policing. Reciprocity to violent policing, therefore, centres on ‘counter-violence’.Footnote 148 Methods of popular protest undergo profound shifts as mechanisms of counterterrorism change, providing resistance groups new opportunities, repertoires, and pathways to violent action.Footnote 149 This ‘competitive adaptation’Footnote 150 allows us to appreciate how terrorist groups not only become resilient and adapt to changes in counterterrorism but also motivate potential recruits who fear death. Our research findings suggest that transnational terrorist groups adapted to coercive counterterrorism on two levels, mirroring state strategies (in this case India): (a) using persuasion and (b) using coercion.

Pakistani ideological and political persuasionFootnote 151 leveraged the severity of Indian injustices in Kashmir so that potential mujahideen could understand the scale and magnitude of its counterterrorism practices.Footnote 152 The aggressive counterterrorism practices convinced already-aggrieved Kashmir civilians to adopt more violent repertoires of protest.Footnote 153 This had two advantages – violent expressions of resentment by even a small group can have a butterfly effect, leading to revolt by even larger groups of civilians.Footnote 154 Civilians protesting against the state provided intelligence on numerical strength and locations of Indian security personnel, as well as estimates of weaponry and tactical positions.Footnote 155 At the same time, their participation extended to stone-throwing, while also acting as human shields to distract security forces. Footnote 156 Strategically, before an encounter would break out, mujahideen communicated with their handlers ‘here in Pakistan that a fight is about to break out. So, the high command attempts to rescue them if possible. The localities in which they are fighting … the high command asks the local jamaat (transnational council of the group) to step in and divert the attention of the security forces so that the jihadis have a window of escape.’Footnote 157

Even as stone throwing forms a critical method of diverting attention, terrorist groups also have to factor in bystanders’ fear of punitive action should they be caught. Appealing effectively to their basic sentiment of resentment, groups inform stone throwers that, ‘if you people are hesitant because you will get arrested … you are treated by badly by India anyway. So, stand up and fight.’Footnote 158 Likewise, as with dealing with bystanders’ fear of participation, to circumvent their own mujahideen serving as informants to Indian counterterror officials, ‘tanzeems (groups) have changed strategy and started targeting civilians now who are shown to comply with police’.Footnote 159 While jamaatis would go into villages to drum up support. ... (shows that while they ostensibly went as friendly figures requesting participation, people actually joined out of coercion). However, initial coercion prompted long-term participation, whereby ‘it’s better to join them because at least our families will not be harmed. That’s why I had gone back then. It’s the same even now. But even if you go out of fear, they brainwash you in a manner where your stance and ideology changes totally and you believe that there is no better life than jihad. Even if you join out of fear, leaving becomes almost impossible.’Footnote 160

One of the key instruments for terrorist groups to resist counterterrorism was to balance Indian violent policing, calculated as part of the mathematics of terror, with their own coercion of the civilian population.Footnote 161 While recruits may not always be ideologically aligned with the group or sufficiently motivated to sacrifice their lives,Footnote 162 terrorist groups adjust their tactics to encourage participation, using inducements as well as force. To maintain their longevity, as well as recruiting new members, groups in Pakistan and in Kashmir leveraged guilt and fear. In such scenarios, civilians are coerced into joining the jihad out of fear of their families being abducted or killed by the transnational cells of the groups.Footnote 163 Furthermore, the fear of divine retribution – underscored by the fear of not entering Jannat (heaven) – fosters action and support for violence.Footnote 164 Given that terrorist groups compete with states for popular support from the same constituency, intimidation becomes a crucial element in outbidding the competition.Footnote 165 However, even as militant groups may sometimes use capture and coercion techniques to induct new members, recruits eventually acclimatise to membership and organisational goals regardless of whether they were lured by the carrot or the stick.Footnote 166

Analysis and discussion

The research findings support the hypothesis put forth in this paper: the greater the criminalisation attached to the perception of the target group (Kashmiri Muslim youth) by the state institutions (central government, military, and police), the greater the bystander sympathy and radicalisation of the target constituency. Heightened repression in Kashmir did not deter but led to greater successes in recruitment of Kashmiri youth using a combination of persuasion and coercion. Similarly, evidence supports the argument that non-coercive approaches, such as intelligence gathering and geopolitical sanctions, still result in increased coercive kinetic military actions.

We therefore argue that, in the short term, alternating coercive and non-coercive counterterrorism approaches may result in increased mobilisation to terrorism. In the long run, however, neither approach is sustainable. Consistent repression does not weaken terrorist groups. On the contrary, groups adapt to changing counterterrorism policies over time and regulate their own control over their base to sustain recruitment. Secondly, non-coercive counterterrorism, when accompanied by punitive action, is ineffective as a deterrent. It neither prevents initial engagement with violence nor fortifies against recidivism. In geographically contested regions such as Kashmir (and the recent case of Gaza), coercive states use kinetic and violent action less for the goal of ending terrorism, but more likely hoping it will plateau to create a lasting stalemate. Recruitment into terrorist groups is as pivotal to the perpetuation of jihad as it is to geopolitics. These propositions have implications for Kashmir and for broader studies of counterterrorism, such as the 2023 lead-up to the war in Gaza.

Every counterterrorism strategy comprises a cyclical interaction between the states engaged in contestation, terrorist groups, and civilians in the Kashmir region. Rarely are these simple dyads in which there is one state and one militant group. Instead, the terrorist landscape is complex and involves multiple and overlapping groups who sometimes compete and at other times cooperate. While the strategy of terrorist groups evolves in conjunction with shifting counterterrorism policies in India, India’s counterterrorism tactics were repetitive, consistently coercive, and did not keep pace with the evolving clandestinity and metamorphosis of groups. This had two broad effects: not only did this enable the proliferation of terrorism by feeding the ideological and political relevance of terrorist groups, but it also enabled recruitment over time despite calculations to weaken the groups.

In analysing the apparent success or failure of counterterrorism in Kashmir, and its role in ending terrorism, existing explanations are as much a clash between ‘identities, imagination, and history’ as a competition over territory and resources.Footnote 167 Armed responses by India have largely failed to contain this conflict.Footnote 168 Indian counterterrorism focused on punitive containment and criminalisation of the civilian population to pre-empt and stymie attempts at widespread mobilisation.Footnote 169 This coercive strategy was intertwined with the existing complex trauma and recollection of repression and grievances.Footnote 170 In essence, the interplay between terrorism and counterterrorism efforts actually perpetuated the conflict. To say that it is a summation of India’s intransigent security policies and Pakistan’s enduring ablity to sponsor terrorist groups to wrest territorial control of Kashmir, would be an oversimplication. Existing explanations on the conflict stop short of examining the very counterterrorism practices that have perpetuated the violence.Footnote 171 State sponsorship exists along a spectrum from turning a blind eye to militant organisations using the state’s territory as a base of operations, providing material and/or financial support, to actually directing the militant movement’s attacks and targets, whereby the terrorist group is a proxy for the state.Footnote 172 While India carried out these policies in hopes of containing terrorism and ending the groups altogether,Footnote 173 terrorism can end actively the civilian population rejects violence.Footnote 174

When counterterrorism is conflated with concessions, especially in contested areas, actions to maintain peace are accorded some legitimacy. Not only can this lead to a domino effect where sympathetic civilians and terrorist groups respond to kinetic actions with equal fervour, but the longevity of groups and recruitment increases exponentially, as a result of popular support,Footnote 175 thereby legitimising the replacement of peacebuilding with coercive counterterrorism.Footnote 176 Population-centred approaches such as dialogue or political engagement with ethnonationalist groups or domestic interlocutors are often perceived with distrust and concessions withdrawn where the benefits of coercive counterterror outweigh its costs, and contrarily the cost of peacebuilding outweighs its benefits.Footnote 177

Concessions, in case of Kashmir, have unfortunately been conflated with counterterrorism. In geographically contested regions, states favour coercive counterterrorism, not with the intention of ending terrorism, but also to allow it to instead function on a plateau. Not only does this lend greater legitimacy to states that engage in coercive counterterrorism, but it also prevents issues of contestation from either petering out or tilting in favour of either region. Both terrorist violence as well as counterterrorism, as instruments of state policy and engagement, are self-ratified by contesting states. This allows for a generational endurance and perpetuation of jihad, recruitment into jihad, legitimation of the existence of jihad, and bystander sympathy, thus having important implications for the long-term survival of terrorist groups.

Conclusion and future policy directions

The article argues that as far as the effectiveness of counterterrorism goes, coercive and non-coercive counterterrorism or concessions might function as deterrents in suppressing active bystander sympathy and transnational terrorist cells. As groups regroup and adapt, counterterrorism is mooted since consistent state repression stalls neither the movement nor the terrorist groups that might emerge. Instead, counterterrorism animates increased lethality, recidivism, and violent collective action. The resilience of militant groups does not occur in a vacuum. It is critical to recognise the processes and structures that enable resilience in the wake of counterterrorism and how the policies can backfire. The absence of state-to-state rapprochement and prolonged contestation has enabled groups to outwit counterterrorism measures and outbid the state in retaining control over their base.Footnote 178

Examining the longevity of terrorist groups and recruitment has critical implications for the broader study of terrorism and counterterrorism, as well as of policy formulation. This research found that the Indian state’s perception of the region’s civilians en masse as sympathetic to the cause of transnational terrorist groups mooted their counterterrorism strategies. Coercive legislation and containment policies masqueraded as concessions but over time led to greater resentment and retaliation by the civilian population. Counterterrorism against transnational terrorist groups was realised on two levels. The first was the use of their intelligence framework, and the second was kinetic action. In both, groups (and civilians) eluded Indian counterterrorism. Groups regrouped, resisted attrition rates, and continued to recruit into their ranks. Counterterrorism, therefore, did not end terrorist recruitment and violence but rather maintained it.

While the research suffered from some methodological limitations such as accessing additional interview participants in rural Pakistan, the findings have important policy implications. Not only do they explain how terrorist groups circumvent counterterrorism practices, regroup, and sustain mobilisation, but we also find that traditional counterterrorism alone fails to end terrorist groups. Furthermore, consistent repression fails to weaken terrorist groups or their regional support structure. On the contrary, groups adapt to changing counterterrorism policies over time and regulate control over their target recruit base, thereby perpetuating recruitment, even if it is clandestine, and outbidding the state in controlling the region’s civilians.

Considering the above findings, the research offers insights into possible peacebuilding strategies essential for fostering long-term stability in conflict-affected regions like Kashmir. Echoing the counterterrorism–terrorist violence link in Kashmir, Hsu and McDowall found that the interaction was mirrored in Israel, where repressive counterterrorism actions led to increased terrorist violence. We suggest a more constructive approach is necessary to break the cycle of violence.Footnote 179 For such regions, peace needs to be two-pronged. The first should carry forward the psychological approachFootnote 180 which provides a platform to address trauma-informed policies for prolonged conflict. Not only does community-based peacebuilding empower local populations, but they also enhance social cohesion and create alternative narratives to counter extremist ideologies and radicalisation of bystander populations. Second, the psychosocial approach should be supplemented with policy-based peacebuilding initiatives that address the root causes of conflict and foster dialogue and reconciliation among potential recruits or bystanders and the state. While Hsu and McDowall’s examination of Israel finds resonance in the study of Kashmir, future research is required to answer questions of whether states engaged in contestation prefer coercive to softer approaches. The field would benefit greatly from more granular empirical research on the sociocultural and psychological ramifications of concessions to inform potential peacebuilding programmes in other regions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We would also like to thank Dr Sophia Moskalenko for her feedback and consistent support. This paper was presented at the Council for European Studies’ 30th Annual Conference in 2024. We thank CES for their support.

Funding Information

The research was partially supported by the Minerva Research Initiative, DoD Grant No. N00014-21-1-2339-P00001. Any opinions, findings, and recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the views of the Office of Naval Research, the Department of the Navy, or the Department of Defense.

Shaswati Das is a lecturer in economics. Her research focuses on examining patterns of terrorist recruitment and counterterrorism optimisation. She has a PhD in politics from the University of York (United Kingdom).

Mia Bloom is an International Security Fellow at New America and Professor at Georgia State University. She’s the author of Dying to Kill: The Allure of Suicide Terror (2005), Living Together after Ethnic Killing (2007), Bombshell: Women and Terror (2011), Small Arms: Children and Terror (2019), Pastels and Pedophiles: Inside the Mind of QAnon with Sophia Moskalenko (2021), and Veiled Threats: Women and Jihad (2025), recently published by Cornell University Press.