1. Introduction

The term ‘competition’ is a core notion for social and economic thinking and the organisation of markets. It has a special, double function within the European Union (EU) context. First, safeguarding competition is one of the justifications for the EU’s operation. The Preamble of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) declares that concerted action by the Member States is necessary to ‘guarantee steady expansion, balanced trade and fair competition’.Footnote 1 Article 119 TFEU specifies that EU economic policy follows ‘the principles of an open market economy with free competition’. Moreover, the concept of the internal market itself ‘includes a system ensuring that competition is not distorted’.Footnote 2 Second, the notion of competition also defines the border between legal and illegal behaviour. The competition law prohibitions only forbid behaviour that may hinder competition: Article 101 TFEU prohibits an anti-competitive agreement that has the object or effect of restricting competition within the internal market; and Article 102 TFEU, prohibits the abuse of a dominant position in a manner that prohibits effective competition.Footnote 3

Despite the centrality of the notion of competition – both as a justification for the operation of the EU and as a concept that defines the scope of prohibited behaviour – its meaning is far from unequivocal. The term and its legal-economic underpinnings were not defined in the Treaties or in secondary EU law. They were also left mostly undefined by the European Commission’s decisional practice and policy papers as well as by the judgements of the EU Courts.

This article demonstrates that there is no single acceptable economic imaginary ascribed to the notion of competition in Europe. The search for the meaning of competition is an ongoing journey, from the very inception of the EU 60 years ago to the present day, which is inherently tied to the objectives, scope, and boundaries of EU (competition) law and to socio-economic transformations.Footnote 4 The article first traces the history of the notion of competition in both common-usage language and in legal–economic thinking. It exposes the emergence of three parallel, partly conflicting, imaginaries influencing the notion in EU competition law: First, according to a Keynesian notion of competition, free market forces are not viewed as the only source of economic development. Such forces, it is believed, should be limited to promote other public interest values, such as industrial and social policies. In the EU, Keynesian theories were particularly invoked to foster market integration; Second, an ordoliberal notion of fair competition calls for governmental intervention to foster the individual freedom of market participants; and finally, a neoliberal notion of competition focuses on the maximization of economic welfare. Institutional intervention in markets, according to a neoliberal approach, is prone to result in inefficient market outcomes. Since those three notions are being applied in parallel, the European economic imaginary of competition is still contentious and subject to ongoing political and legal-economic debate.

After demonstrating that no single imaginary of competition was adopted by EU primary, secondary, or soft laws, the article applies Critical Discourse Analysis to the Commission’s annual reports on competition (1971–2020) in search for the meaning of the notion. This exercise reveals that the economic imaginary of competition had acquired different meanings according to the context in which it was used. A strong transformation occurred in the ‘hard’ context of defining the scope of the prohibitions on anti-competitive agreements and abuse of dominance position. Accordingly, the rhetoric of correcting and strengthening the internal market and correcting market failures was almost completely abandoned in favour of a focus on consumer welfare. A similar transformation, yet to a more limited extent, also appeared when interpreting the exceptions and justifications for anti-competitive conduct and when setting the enforcement priorities. Yet, almost no transformation appeared when it comes to the ‘soft’ aims and mandates of competition. Although Keynesian and ordoliberal ideas have characterised the discourse up until the late-1990s, since then the Commission referred to consumer welfare as a supplementary, rather than a new, meaning of competition.

The lack of a clear definition for competition undoubtedly raises challenges relating to the rule of law, legal certainty, and uniformity. Yet, its ambiguity also serves as a powerful tool in safeguarding the durability and legitimacy of competition as an economic imaginary. It allows the Commission and other EU institutions, the Member States, national competition authorities, and EU and national courts to tailor the notion of competition to changing legal, economic, and social conditions. This flexibility guarantees that the competition law prohibitions of the Treaty could remain intact and sway support ever since they were included in the Treaty of Rome, in the face of dramatic social and economic transformations. In the words of the Commission,

the Community competition rules, which have had to be implemented in very different economic circumstances—from sustained expansion to marked recession—have stood the test of time. Based on the general principle of prohibition accompanied by possible exemptions, the system of supervision is sufficiently flexible to take account of the economic conditions prevailing at any given time’.Footnote 5

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology and approach of this study and the definitions used. Notably, it defends the use of the Commission’s annual reports on competition as the unit of study. Section 3 reviews the history of the development of the notion of competition in common-usage language and in legal and economic thinking. That section does not attempt to provide a complete record, but points to the emergence of three imaginaries of competition that have influenced the notion in the EU. Section 4 explores the lack of definition of competition in EU primary and secondary law, the case law of the EU Courts, and the Commission’s decisional practice and policy papers.

Section 5 introduces the findings resulting from applying Critical Discourse Analysis to the Commission’s annual reports. It demonstrates that the notion of competition had acquired one meaning in ‘hard’ contexts of competition law enforcement, and another meaning in ‘softer’ contexts. While the ‘hard’ contexts have experienced a transformation from Keynesian and ordoliberal imaginary of competition to a neoliberal notion; the ‘soft’ contexts still invoke a broad notion of competition reflecting influences from all three theories.

Section 6 concludes by discussing the impact of the above findings. It argues that on the one hand, the unclear scope of competition carries the power of vagueness, a significant advantage for both the durability and legitimacy of competition law and policy in the EU. On the other hand, this vagueness also raises serious concerns about the respect for the rule of law and the legal certainty and uniformity of EU competition law.

2. Methodology, approach, and definitions

This article explores the development and transformation of the economic imaginary of competition in the EU by applying Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to the Commission’s annual reports on competition (1971–2020). Economic imaginaries are understood as ‘a semiotic system that gives meaning and shape to the “economic” field’.Footnote 6 Comprising of a specific configuration of genres, discourses, and styles, they frame individual subjects’ lived experience of an inordinately complex world and inform collective calculation social practices in a given social field, institutional order, or wider social formation.Footnote 7

CDA was chosen as an inter-disciplinary method to investigate language in use, aiming to study society through discourse, and to contextualise and understand discourse through an analysis of its historical, socio-political, and cultural foundations.Footnote 8 CDA is grounded on the belief that discourse, and in particular the use of specific terms, is socially constitutive and conditioned.Footnote 9 It is a means through which ideologies are reproduced.Footnote 10 Tracing the various and changing meanings ascribed to competition in the Commission’s annual reports, therefore, seeks to reveal the use of language as social action and the development a shared imaginary.

At first sight, the focus on the annual reports may seem like a curious unit of study. Arguably, the search for an EU economic imaginary of competition should naturally focus on its manifestation in ‘hard’ law instruments – such as EU primary and secondary laws and the case law of the EU Courts – or at least on the Commission’s decisional practice or guidelines. Nevertheless, past research has observed that the Member States and the EU institutions have abstained from defining the meaning of competition in such sources or defined them by using general and vague language.Footnote 11 This led scholars to search for the meaning of competition in other sources, such as the speeches of the EU Commissioners for Competition,Footnote 12 the debate in the European Parliament Plenary,Footnote 13 or economic experts’ discourse on competition in the media.Footnote 14

Against this background, the annual reports provide valuable information on the Commission’s views on the concept of competition. Such reports are an important subject of study in search of the economic imaginary of competition not only because they have not been previously explored systematically, but also given some of their special characteristics:

The Commission has begun to publish its annual reports on competition in 1971, upon the European Parliament’s Resolution.Footnote 15 Since then, they provide ‘both an overview and a detailed picture’Footnote 16 of the main developments in competition law each year, highlighting important changes to law and policy and presenting the main cases on the Commission’s docket. By detailing the concrete implementation of the competition rules over a given year,Footnote 17 the annual report provides the Commission with an opportunity to put those developments into context.

The annual reports are an important outlet to influence the economic imaginary of competition. Over the years, the Commission declared that they are a valuable source for communicating its policy not only to other EU institutions (including the Parliament and the Economic and Social Committee) and the Member States, but also to the industry at large, the epistemic community, and the general public.Footnote 18

The annual reports pursue multiple aims. They are intended to provide information comprehension of past policyFootnote 19 and to increase transparency by clarifying and explaining the Commission’s policy.Footnote 20 They seek to foster accountability and compliance,Footnote 21 and accordingly, the Commission aspires to use ‘non-technical language as possible’, providing for the wide dissemination of its policy as ‘a factor fundamental in any democratic society for the successful application of policy’.Footnote 22 The annual reports have the political task of increasing the support for the Commission’s powers and enforcement efforts.Footnote 23 They also offer guidance to national competition authorities (NCAs) and courts to facilitate the decentralised enforcement setting,Footnote 24 and to avoid adopting conflicting decisions.Footnote 25

At times, the annual reports were also forward-looking. The Commission declared that they intended to generate debate on future policy and how to achieve a balance between the EU’s different objectives and priorities,Footnote 26 noting that ‘it is customary’ for the Commission to ‘set out its competition objectives for the coming year in its annual report’.Footnote 27 The annual discussions of the reports in the Parliament and its subsequent resolutions were ‘very useful for the Commission, not only as a sounding-board for its policy, but also as a commentary, both critical and supportive on the quality and contents of the reports’.Footnote 28 They were considered to be of particular importance in the field of competition law enforcement, where the Commission enjoys greater autonomous powers in comparison to other fields of EU law and where formal consultation with the Parliament ‘is the exception rather than the rule’.Footnote 29

Finally, annual reports are a noteworthy subject of study because although they are mostly viewed as a ‘soft’ law outlet explaining and justifying the Commission’s practice, they are binding on the Commission and may carry legal effects on others. In Polypropylene, the applicant alleged that the Commission failed to adequately reason its infringement decision applying Article 101 TFEU, inter alia due to failing to mention that the hearing officer had delivered his opinion.Footnote 30 The applicant based its claim on the rules adopted by the Commission and reported in its annual report, setting the terms of reference for the operation of the hearing officer. In the course of examining whether the Commission had followed its own procedure, the General Court (GC) implicitly confirmed that the Commission must abide by the rules it imposes on itself within the annual reports, under the pain of breaching the EU principle of legal certainty.

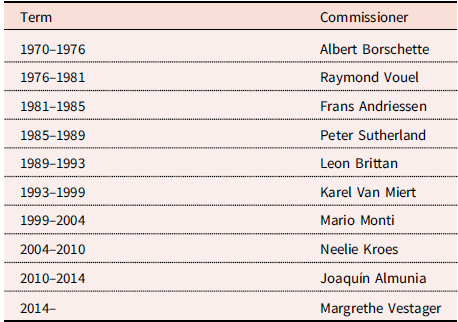

To eliminate irrelevant differences resulting from changes in the format and style of the annual reports over the years, the analysis focused on the body of the reports (excluding, in particular, the introductory notes by the Commissioners for Competition and the annexes). Moreover, the CDA was limited to the description of EU competition law and policy in general and to the application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. It did not cover statements relating to merger control and state aid, which may reflect other meanings of competition. The identity of the Commissioners for Competition (see Table 1), which carries much significance in the drafting of the reports, was considered when analysing the results in Section 5.

Table 1. EU commissioners for competition

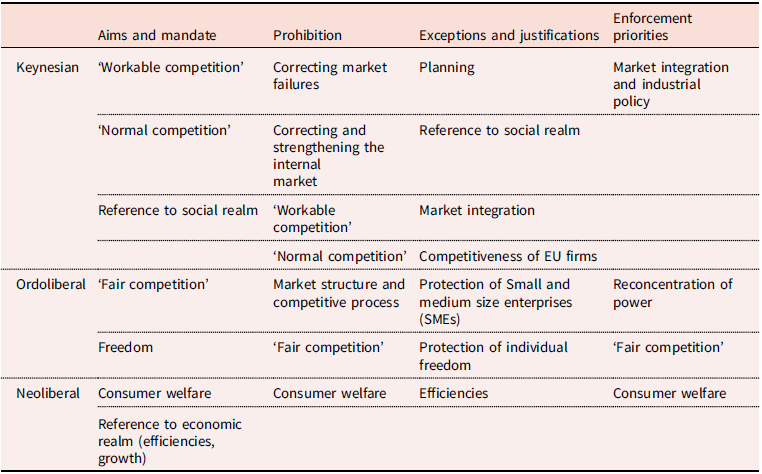

The analysis centred on the expression of the economic imaginary of competition. The categorisation (see Table 2) of the various meanings of competition – as an expression of Keynesian, ordoliberal, or neoliberal notions – were inspired by codes identified in Pühringer et al based on a theory-driven coding system.Footnote 31 Yet, this article suggests that the concept of competition had acquired different meaning across four contexts of competition law enforcement:, that is (i) the scope of the prohibition of competition; (ii) the exceptions or justifications for allowing otherwise anti-competitive behaviour in favour of promoting other public policies; (iii) the aim and mandates of the competition rules; and (iv) the selection of enforcement priorities. The analytical categorisation system and the four contexts of competition law enforcement guiding the analysis are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Categorisation system

3. The economic imaginary of competition: from Roman Law to the Treaty of Rome

This section provides historical background on the development of the notion of competition from Roman civil law and up until the entry into force of the Treaty of Rome establishing the EEC. This overview intends to place the debate into context, pointing to the multifaceted and vague meaning of this notion. It does not intend to provide a full account of the history of the concept, which was explored by previous studies.

A. The genesis of the term in non-technical language

The definition of the notion of competition has occupied economic and legal thinking for decades, if not centuries. One of the reasons for this vagueness lies in the history of the concept. ‘Competition’ is not a term that is limited to law or economics. It was not originally developed in technical language, and entered legal and economic scholarship gradually, as a term of common usage.Footnote 32 The English verb was borrowed from late medieval Latin or early modern French, becoming part of the non-technical language as early as the 14th century. At first, it was used in a passive manner to describe ‘to fall together, coincide, be fitting’,Footnote 33 yet from the second half of the 16th century it shifted towards an active sense, pertaining to the process of contending or striving.Footnote 34

Dennis shows that after the verb was first defined analytically by Dyohe and Pardon in 1735 as ‘the striving of two or more persons to get or do the same thing’,Footnote 35 its common usage remained relatively stable. This stability was made possible due to its ‘vagueness, ambiguity, nebulousness, elasticity and general lack of precision’.Footnote 36 As an open-ended term, competition is not limited to a specific type of competitive grouping, competitive strategies, or setting nor to the attainment of a single economic objective.Footnote 37 It is used beyond the fields of economics or law, to describe a wide array of interactions, ranging from personal relationships, to contact between nation states, funding of academic work, entrustment, and more.Footnote 38

At the same time, there is one stable element in the non-technical usage of the term. Competition, in its common use, rarely describes a form of pure conflict. It typically refers to a type of ‘civilized conflict, that is, a pattern of inter-action in which both conflictual and co-operative elements subsist together. Though the conflictual predominates, the co-operative gives to competition its social structuring’.Footnote 39 To this end, competition is considered as a social process expressing the observance of some (explicit or implicit) ‘rules of the game’ or shared conventions.Footnote 40

As elaborated below, this common element also characterises the legal–economic meaning ascribed to competition. Competition is not merely the process of rivalry between producers, buyers, or sellers. It reflects complex notions on how markets and societies should be organised and operate. The protection of competition is often seen as an instrument to achieve other public policy aims, such as economic growth, social equality, or the distribution of wealth. Keeping in mind the non-technical origin of the term when searching for the economic imaginary is useful nevertheless, as it tends to distinguish between the means (competition) with its (socio-economic) ends.Footnote 41

B. The emergence of legal and economic theories of competition until the 1900s

Technical definitions of competition, such as those developed in the fields of law and economics, are often more complicated because the rivalry among firms is mostly viewed only as a means to achieve desirable aims. Different notions of competition reflect various theories of markets and societies and manifest distinctive preferences towards the balancing of economic, social, and political objectives.Footnote 42 Theories of competition differ in the character of competition they pertain to (eg, static or dynamic), the scope of competition (eg, the competing actors and what these actors are competing for), the methods to investigate competition and their epistemological orientations, and the normative connotations and political links underpinning the debate.Footnote 43

There is no clear point in time in which the term has entered legal–economic theory. The classical Latin antecedent (‘compete’) was used in Roman civil law in the sense of petitioning a legal case or seeking a legal claim. A similar term to the modern idea of competition was rather embedded in the notion of ‘monopoly’, which was coined by Aristotle in Politics, and later employed by Roman jurists to develop the theory of just (fair) prices.Footnote 44 The verb competition commonly appeared through the Justinian reports of Roman civil law, and – interestingly – next to the passages on just and fair pricing.Footnote 45 Although competition carried no economic significance in that context, it was proposed that the proximity of the passages suggests that competition was developed by medieval and early modern scholarship on just price and gradually transformed into a more actively economic verb form.Footnote 46

The notion of competition was central to the development of classical economics. Dominant in the 18th and 19th centuries, this school of thought responded to the industrial revolution and the rise of Western capitalism, at a time of transition from monarchic rules to capitalistic democracies with self-regulation. Classical authors believed that markets that are characterised by free competition will gravitate towards a ‘natural price’.Footnote 47 This idea was fundamental to the works of Adam Smith. Smith believed that competition among producers is a safeguard against monopoly pricing, explaining that: ‘the price of monopoly is upon every occasion the highest which can be got. The natural price, or the price of free competition, on the contrary, is the lowest’.Footnote 48 Ricardo later limited this conclusion, restricting it situations in ‘which competition operates without restraint’.Footnote 49 In this context, competition was used to describe the activity in which people engage in, that is the rivalling behaviour of individual economic actors. Footnote 50

Classical thinkers have predominately ascribed positive connotations to competition. Competition depicted a dynamic process, the race against scarcity of resources that forces price towards an equilibrium of supply and demand.Footnote 51 Werron noted that the emergence of this classical imaginary of competition justified competition as an institution. It puts ‘pressure on the competitors and works to the advantage of consumers and, by implication, the advantage of society at large’.Footnote 52

Competition served an important role in the formalisation of economic reasoning in the course of the 19th century. Footnote 53 In the famous words of John Stuart Mill ‘only through the principle of competition has political economy any pretension to the character of a science’.Footnote 54 Nevertheless, despite its importance, the notion of competition began to receive systematic attention in economic literature only towards the late 1800s. Competition, as Stigler noted, ‘as pervasive and fundamental as any in the whole structure of classical and neoclassical economic theory – was long treated with the kindly casualness with which one treats of the intuitively obvious’.Footnote 55

The first steps to analytically refine the concept were made by mathematical economists. They developed the terms as a model-based analysis, whereby competition is investigated by creating an artificial surrogate for the actual system under investigation.Footnote 56 The ‘archetype’ of the model-based approach to competition is reflected in the theory of perfect competition. Its genesis traces back to 1838, when French mathematician Cournot analysed the profit-maximization problem of a producer deciding how much to supply to a market of homogeneous goods, taking as given the quantities supplied by its rivals. In this oligopolistic market structure model, competition resulted in the reduction of prices. Cournot identified cases of ‘unlimited competition’, in which no seller could appreciably affect the market price.Footnote 57

Edgeworth was the first to attempt a systematic and rigorous definition of perfect competition, observing that competition requires indefinitely buyers and sellers; absence of limitations upon individual self-seeking behaviour; and divisibility of the commodities traded.Footnote 58 The modern theory of perfect competition was developed and formalised up until the 1920s by attaching additional conditions such as the existence of homogeneous products, that all firms are price takers, perfect information, and lack of entry and exit barriers.Footnote 59

As a model-based analysis, perfect competition provided a mathematical model, which scholars study analytically. Such classical authors did not focus on the correctness of the assumptions of the model, but rather on the derivation of mathematical results within its sphere.Footnote 60

The emergence of early neoclassical economics in the early 1900s represented a transformation in the meaning of competition, which still characterises much of economic imaginary of the notion to this very day. Neoclassical thinkers departed from the classical economics approach to determining the value of a good or service. Instead of focusing on the cost of production, the welfare of consumers is key. Unlike classical thinkers that described competition as a process, therefore, neoclassical analysis emphasis its results. Competition is presumed to lead to an efficient allocation of resources within an economy; and by maximising economic efficiency is likely to also maximise the overall social welfare.Footnote 61

Around the same time, from the mid-1800s, there was also a transformation in the normative connotations of competition.Footnote 62 The debate about more ambivalent effects of competition was aptly summarised by Edgeworth in his ‘Competition and Regulation’ entry contributed to the Dictionary of Political Economy of 1910:

[t]he general presumption in favour of competition may be outweighed in particular cases by the disadvantages which have been noticed. The balance of contemporary opinion seems inclining to the position thus indicated by Professor Sidgwick: ‘It does not appear to me that the answer (.. .) in concrete cases can reasonably be decided by any broad general formula; but rather that every case must be dealt with on its own merits, after carefully weighing the advantages and drawbacks of intervention. The expediency of such interference in any particular case can only be decided by the light of experience after a careful balance of conflicting considerations’.Footnote 63

A famous and systematic challenge to the benefits of competition also emerged in the writing of Karl Marx. Marx rejected the idea of competition ‘as the mutual repulsion and attraction of free individuals, and hence as the absolute mode of existence of free individuals in the sphere of consumption and exchange’.Footnote 64 Competition was considered as a negative force, fostering the development and reproduction of a capitalistic production mode, where the command of capital over labour has already been established.Footnote 65

C. Competition in the post-war era: Keynesian, Ordoliberalism, and Neoliberalism theories

The notion of competition in the post-war era was greatly influenced by academic theories developed in other disciplines of social science beyond economics.Footnote 66 As elaborated below, such theories were advanced as a response to the economic and social crises following the World Wars and the Great Depression. As such, unlike the theory- and model-based mathematical approaches, they strived to offer practical solutions and rules to the organisation of society and markets.

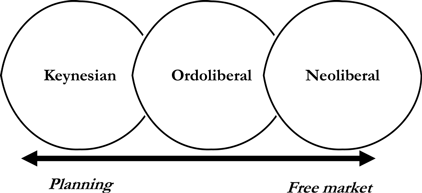

This section focuses on the three theories that inspired the development and application of EU competition law: Keynesian, Ordoliberalism, and Neoliberalism. As demonstrated by Figure 1 and elaborated below, such theories vary in the degree of what they portrayed as optimal market interference: on the one side of the scale, Neoliberalism favours laissez faire and limited intervention in markets; on the other side, Keynesian theory calls for governmental intervention and planning; and Ordoliberalism represents a middle ground between the two.

Figure 1. Theories of competition.

Keynesian theory, ‘workable competition’, and market integration

An important challenge to the classical theory of competition risen in the 1930s, against the background of World War I and the Great Depression. British economist John Maynard Keynes contested the classical economics assumption that competition will lead towards a point of equilibrium and ‘natural prices’. He argued that there was neither a guarantee that supply will meet effective demand, nor that the economy could maintain full employment. Contending that free market economies often result in under-consumption and under-spending, Keynes suggested that the global markets could recover by increasing government expenditures and lowering taxes to stimulate demand.

According to Keynesian macroeconomic theory of competition, therefore, pure competition and free market forces are not always regarded as the best stimulants of economic growth. At times, state involvement is necessary to correct market failures and competition should be actively limited in favour of fostering other industrial and social policies.Footnote 67

Keynesian theories have inspired the development of the workable competition school of thought, dominating the United States (USA) antitrust policy in the 1950s.Footnote 68 The term workable competition was coined by economist John M. Clark, submitting that perfect competition cannot serve as a norm for economic policy because it stifles economic development. Some restrictions of competition were viewed as inseparable from economic progress.Footnote 69 Workable competition aimed to offer a realistic standard, by which competition is considered to be workable to the extent that it is likely to result in socially beneficial outcomes.Footnote 70

Keynesian microeconomic theories were embraced by many European states from the post-war order and up until the 1970s. As elaborated below, Keynesian theories in general and the notion of workable competition in particular, had an immense influence on EU (competition) law during that period.Footnote 71

Importantly, Keynesian ideas have also guided the application of EU competition law and policy as a means for completing the internal market and for the development of the EU’s industrial policy. The objective of market integration directed focusing the enforcement priorities on practices having the most negative impact on cross-border trade rather than on competition as such; and tolerating practices that did not hinder cross-border activity or promoted EU industrial policy, even when they considerably restricted competition.Footnote 72 Informed by Keynesian theory, the Commission took into account EU industrial policy interests aimed at growth, regional cohesion, and employment when applying the EU competition rules.Footnote 73

Ordoliberalism

A separate challenge to classical theory of competition emerged from Ordoliberalism. Also known as German Neoliberalism, this political economy school of thought was developed in the early 1930s against Hitler’s ascent to power and stimulated the creation of the social market economy in Germany after World War II.Footnote 74 It was inspired by the works of the Freiburg School, consisting of economics as well as legal scholars.

Ordoliberal theories reserve an important role for competition policy as a means to protect individual economic freedom of action. They call for the creation of an economic system where all individuals can freely participate in economic life, and where governmental regulation safeguards against cartels and monopolies that can hamper such economic freedom. Ordoliberal competition policy is directed at eliminating private economic power concentrations and establishing and enforcing complete competition on markets. Governmental intervention is directed at imposing fair conduct obligations and for suppressing economic power.Footnote 75 While the protection of individual freedom is presumed to bring about more efficient economic outcomes, the preservation of free society is understood as the ultimate goal of ordoliberal competition policy.

The protection of economic freedom and safeguarding against concentrated economic power have characterised US antitrust law in its early years.Footnote 76 Yet, Ordoliberalism has profoundly inspired EU competition law.Footnote 77 As elaborated below, it informed the EU’s lenient policy towards Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and the aspiration towards an ideal of ‘free’ or ‘normal’ competition.

Neoliberalism

A considerably different approach to competition was inspired by the neoliberal movements of the 1970s. Neoliberal authors, such as Milton Friedman and George Stigler, used the analytical tools of neo-classical economics to advance a political-moral philosophy. Criticising central planning policies such as those informed by Keynesian and ordoliberal theories, they questioned the nature of state intervention in markets. Governmental interventions were depicted as motivated by self-seeking politicians and pressure groups. A host of ‘governmental failures’ (eg, regulatory capture, rent-seeking, and corruption) were described as more harmful than market failures.Footnote 78 Neoliberalism, accordingly, represents both an economic and a political policy, enhancing the working of free markets and attempting to limit government spending, regulation, and public ownership.

A neoliberal concept of competition was developed by the writings of Bork on US antitrust law and the Chicago School thinkers.Footnote 79 According to this approach, markets are normally expected to cure themselves, and a competitive outcome is likely to emerge without governmental intervention. The intervention embedded in the actions of competition agencies and courts, in and of themselves, might result in inefficient outcomes and hindrance to consumer welfare. Hence, the test for using the force of competition law enforcement should not be the market power held by the competitors, but rather whether the potentially anti-competitive practice is efficient and likely to enhance consumer welfare.Footnote 80

The neoliberal approach to competition law and policy and the focus on consumer welfare became the hallmark of competition law systems across the globe.Footnote 81 While the notion of consumer welfare has become the cornerstone of many modern competition law systems, it does not have a clear definition. Some equate consumer welfare with the economic concept of consumer surplus, referring to the price consumers would be willing to pay for a good or service, less what they actually paid. Others link consumer welfare to the economic concept of total welfare, that is the aggregate of the consumer and the producer surplus produced by a certain arrangement.Footnote 82 Like the term competition, consumer welfare too is an open-ended and often vague notion.

4. The notion of competition in EU law and policy

This section demonstrates that EU primary and secondary laws have not designated a clear economic or legal theory to define the aims, nature, and scope of competition that is protected by EU law. Such gap, moreover, was not fully filled by the case law of the EU Courts or the Commission’s decisional practice.

A. EU treaties

The absence of a reference to a theory of competition in EU primary law is particularly striking when compared with the Treaty Establishing the European Steel and Coal Committee of 1951 (ECSC), the predecessor of the EEC. While the competition law provisions of the ECSC resembled those that were later included in the Treaty of Rome, they take a more normative stance. The ECSC declares that it aimed to ‘assure the establishment, the maintenance and the observance of normal conditions of competition, and take direct action with respect to production and the operation of the market only when circumstances make it absolutely necessary’. Along the same lines, anti-competitive agreements were prohibited under the ECSC if they prevented, restricted or distorted ‘normal competition within the common market’.Footnote 83 The term ‘normal competition’ reflects Keynesian influences. In the words of the ECSC High Authority, ‘[c]ompetition in the Common Market is not therefore the general “free-for-ad” jungle which would result from the pure and simple abolition of every obstacle to trade, but a regulated competition resulting from dehberate action and permanent arbitration’.Footnote 84

The Spaak Report of 1956, laying down the foundations of the Treaty of Rome, reverted to a more neutral phrasing of competition. It noted that the competition law provisions ‘will be limited to practices affecting interstate commerce which take the form of cartel organizations (ententes) and monopolies using discriminatory practices dividing markets, limiting production and controlling the market for a particular product’.Footnote 85 Accordingly, the Treaty of Rome of 1957 and its successors used general and vague statements, which do not fit a single theory of competition.

The Treaty of Rome declared that the EU aims to guarantee ‘balanced trade and fair competition’, ‘the principles of an open market economy with free competition’,Footnote 86 and that the internal market ‘includes a system ensuring that competition is not distorted’.Footnote 87 The Treaty prohibitions against anti-competitive practices outlaw anti-competitive agreements having the ‘object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market’ (Article 101 TFEU, ex. Article 85 EEC and Article 81 EC), and the abuse of a dominant position in a manner that prohibits effective competition (Article 102 TFEU, ex. Article 86 EEC and Article 82 EC).Footnote 88 Furthermore, the two competition law prohibitions seem to follow the same standard of competition despite the different market situations and harms they pertain to.Footnote 89

The wording of the EU competition law prohibitions has remained untouched in following Treaty amendments. As Section 5 will illustrate, their vague and open-ended wording meant that they could survive a significant transformation in the meaning of competition without modifying the Treaty. The general references to competition, however, underwent some changes throughout the years.

In the early days, ‘a system ensuring that competition in the internal market is not distorted’ was identified as one of the EU ‘activities’.Footnote 90 In 1997, in anticipation of the completion of the internal market and the opening of traditionally public sectors to competition, the Treaty of Amsterdam introduced a new provision for services of general economic interests. The new Article 7d, in the words of the Commission, ‘reinforces the principle whereby a balance must be struck between the competition rules and the fulfilment of public services’ missions’ and conferred ‘a new legitimacy’ on the main institutional and legal balances relating to competition policy.Footnote 91

The discarded draft of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe of 2004 had proposed to increase the status of competition beyond a mere ‘activity’, by declaring that ‘an internal market where competition is free and undistorted’ is a separate objective of the EU.Footnote 92 Yet, this proposal was abandoned following strong opposition from the French government, maintaining that competition should not be understood as a means and an end unto itself, but as a mechanism for the realisation of the EU’s industrial policy.Footnote 93 Not only did this debate not result in the elevation of the status of competition, but from the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, competition is no longer even mentioned as an ‘activity’ of the EU.

While this reform might carry a political significance, it did not change the legal status of competition. The EU’s commitment to competition is still enshrined in Article 119 TFEU, declaring that EU economic policy follows ‘the principles of an open market economy with free competition’, and in the Protocol on the Internal Market and Competition annexed to the Treaty, stating that the internal market includes ‘a system ensuring that competition is not distorted’.Footnote 94 Despite some early doubts, the European Court of Justice (CJEU) reaffirmed the status of competition, noting that the Protocol is an essential part of the objectives of the Treaty.Footnote 95

B. EU secondary law and jurisprudence

EU secondary legislation detailing the enforcement particularities does not offer a definition of the notion of competition. Like the Treaty, it uses convoluted and general terms: the preamble of the old Regulation 17/62 states that Articles 101 and 102 TFEU should be applied ‘to establish a system ensuring that competition shall not be distorted in the common market’, and the new Regulation 1/2003 declares that the two Articles ‘have as their objective the protection of competition on the market’.Footnote 96

This gap was not filled by the EU Courts.Footnote 97 Over the years, the courts made various statements that can be linked with a specific theory of competition. Yet, they did not take a clear and a consistent stance, attributing numerous – and sometimes conflicting – meanings to the notion:

In some cases, the courts tied the protection of competition to the achievement of an array of socially desirable outcomes. In 1977, the CJEU declared in its Metro judgement that Article 101 TFEU is not necessarily guided by a standard of perfect competition. Rather, it is a representation of workable competition, that is to say, a degree of competition ‘necessary to ensure the observance of the basic requirements and the attainment of the objectives of the Treaty’.Footnote 98 Reflecting Keynesian theories, the Court maintained that a lower degree of competition is optimal where an agreement is necessary for the pursuit of an economic or social objective of the Treaty.

In later cases, the EU Courts appeared to advocate similar ideas, without referring to the notion of workable competition directly. They announced that the function of the EU competition prohibitions is to ‘prevent competition from being distorted to the detriment of the public interest, individual undertakings and consumers, thereby ensuring the well-being of the European Union’.Footnote 99 In particular, the Courts tied the protection of competition directly to the internal market objective, noting that Article 101 TFEU ‘should be read in the context of the provisions of the preamble to the Treaty which clarify it and reference should particularly be made to those relating to “the elimination of barriers” and to “fair competition” both of which are necessary for bringing about a single market’.Footnote 100

However, in other judgements, the Courts have invoked competition as an independent value that is not tied to its outcomes. They stated, for instance, that Article 101 TFEU aims to protect ‘competition as such’.Footnote 101

The ambiguity of the case law is reflected in the CJEU’s more recent ruling in Servizio. The Court defined a broad range of objectives for Article 102 TFEU, declaring that it was designed to prevent restrictions of competition to the detriment of the public interest, individual undertakings, and consumers.Footnote 102 The Court, on the one hand, agreed with the Advocate General that the ultimate objective of Article 102 TFEU is to protect the welfare of (final and intermediate) consumers. Yet, on the other hand, it disagreed with the Advocate General by holding that a competition authority is not required to prove that a practice has the capability of harming consumers, but merely demonstrate that it is likely to undermine, by using resources or means other than those governing normal competition, an effective competitive structure.Footnote 103

C. Commission’s guidelines, notices, and decisional practice

The Commission’s guidelines, notices, and decisional practice too do not reflect a single meaning of competition. To this end, commentators have pointed to a transformation in the economic theory and political ideology surrounding the Commission’s approach; while in the past the Commission placed emphasis on the preservation of economic freedom and the internal market (reflecting Keynesian and ordoliberal influences), since the late-1990s it called for a ‘more economic approach’ advocating an increased focus on consumer welfare (reflecting a neoliberal approach).Footnote 104 Such a transformation is apparent, for example, in the rhetoric used in the Commission’s guidelines and notices interpreting Articles 101 and 102 TFEU and when setting its enforcement priorities.Footnote 105

At the same time, the Commission did not adopt a clear imaginary of competition. First, previous empirical studies revealed the multiplicity of goals and interpretations of the notion of competition in the Commission’s decisional practice.Footnote 106 While neoliberal notions clearly influenced the Commission, their full effect is uncertain, and the Commission’s interpretation was influenced by other notions too. Second, although consumer welfare ‘is repeatedly pronounced as a motto in reference to the ultimate objective of [EU] competition rules’, the Commission did not articulate a test to guide its application.Footnote 107 Despite the use of the consumer welfare rhetoric in its policy papers, the Commission avoided applying this standard in its decisional practice.Footnote 108

Consequently, it is unclear how the Commission interpreted this notion and to what degree the notion of competition underwent a significant substantive transformation. These uncertainties grow as the Commission does not have the legal competence to depart from the substance of the EU competition rules as they are defined in primary and secondary laws and the case law of the EU Courts. As the EU Courts continue to link the interpretation of the competition rules to the broad economic and social objective of the Treaty, the Commission cannot adopt a fully neoliberal approach.

5. Empirical findings: economic imaginary of competition in the Commission’s annual reports on competition

The previous sections demonstrated the wide range of possible meanings that the concept of competition acquired in technical and non-technical language. No clear definition was embraced in EU competition law, and multiple – sometimes conflicting – approaches were applied side by side. As Pühringer et al noted, the coexistence of such a range serves as an economic imaginary in the process of transmission of economic knowledge into political and social practice.Footnote 109

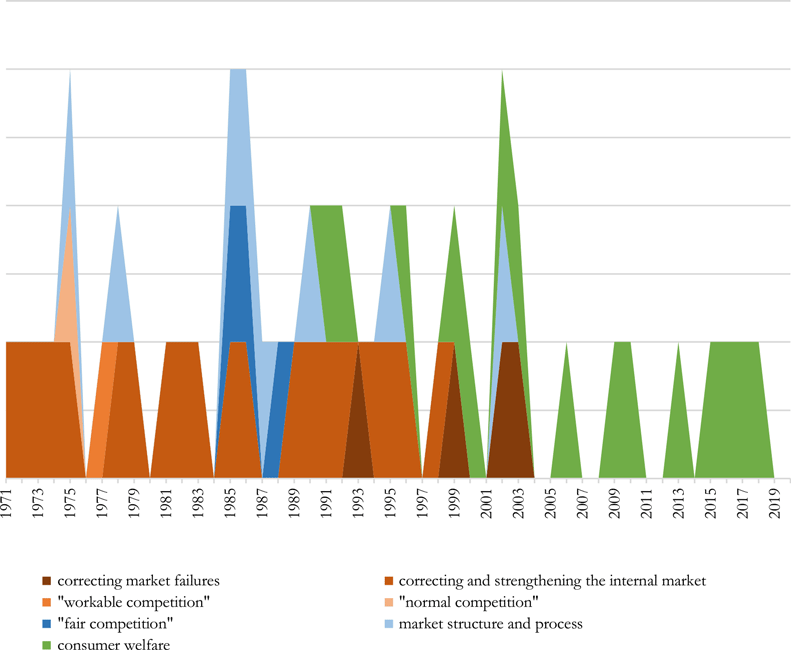

This section, therefore, moves to examine the transformation of the economic imaginary of competition in the Commission’s annual reports on competition. It summarises the findings of applying Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to the Commission’s annual reports (1971–2020). The figures presented in the following subsections categorise the various meanings ascribed to competition in each year’s report, differentiating between the expression of Keynesian (orange areas), ordoliberal (blue areas), or neoliberal (green areas) notions.Footnote 110 Notably, in many cases, the various notions of competition are complementary to each other: the prohibitions of anti-competitive agreements and abuse of dominance are likely to generate positive socio-economic effects pursuant to all of those approaches. In other situations, however, the notions of competition might stand in tension with one another.Footnote 111 The CDA therefore, focuses on the latter, that is the expressions of a specific imaginary of competition.

Each figure describes the development of the notion of competition in one context of competition law enforcement: the scope of the prohibition of competition; the exceptions or justifications for allowing an otherwise anti-competitive behaviour; the aims and mandates of the competition rules; and the selection of enforcement priorities.

Before moving to present the findings, it is noteworthy to point out what the CDA did not find. The CDA reveals that perfect competition was never presented as the standard for competition in either of the four contexts of enforcement. On the contrary, in 1990, the Commission expressly declared that ‘it has never been the intention that competition policy, as pursued by the Community, should create a model of perfect competition’. The Commission argued that competition policy is ‘directed towards attaining the objectives set by the Treaty, primarily the establishment of a genuine single market which is both open and competitive’.Footnote 112 Two years later, it once again emphasised that competition policy ‘cannot be pursued in isolation, as an end in itself, without reference to the legal, economic, political and social context’.Footnote 113

A. Prohibitions

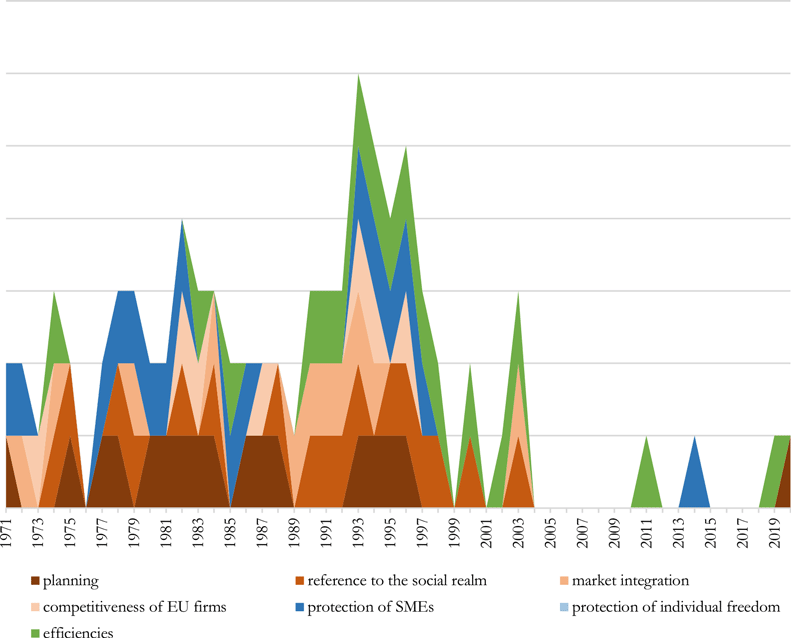

The CDA points to a clear transformation in the economic imaginary of competition as it was developed in the Commission’s annual reports when describing the prohibitions of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. Figure 2 demonstrates that from the 1990s, the notion of competition has gradually shifted from a representation of Keynesians ideas of correcting and strengthening the internal market and correcting market failures and ordoliberal notions of ‘fair’ competition to a focus on the impact of an alleged infringement on consumer welfare.

Figure 2. Prohibitions.

These findings are consistent with the common view in the scholarship, reporting this shift in the Commission’s policy papers and decisional practice.Footnote 114 The Figure shows that from the 1970s to the late-1990s, the Commission emphasised the market integration function of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. This goal, in particular, was used to explain the Commission’s approach to vertical agreements concluded among suppliers and distributors in the various Member States. The Commission declared that such agreements ‘always received particular attention under Community law in view of the goal of market integration. It has been a core element of Community policy to keep channels for parallel trade open and free from restrictions by private business’.Footnote 115

The Commission had also interpreted the function of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU as a means to attain other objectives beyond the protection of competition as such. In 1977, following the CJEU’s judgement in Metro that was described above, it explained that the requirements of Article 101 TFEU and Article 3 of the EEC Treaty entailing ‘that competition shall not be distorted implies the existence on the market of “workable competition”’.Footnote 116 In the following years, as elaborated in the next sub-section, the workable competition standard mostly played a role in justifying the exemptions to the prohibitions.

The Commission has also interpreted the prohibitions of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU in the light of preventing and combating adverse effects resulting from undistorted competition. It maintained, for example, that Article 101 TFEU should not be used to prohibit collective negotiation agreements aimed at improving conditions of work and protecting employment. Such agreements, according to the Commission, ‘do not, given their nature and purpose, fall within the scope of Article [101 TFEU]’ as the aim of the EU Treaties is not only to ensure competition but also to pursue social policy.Footnote 117 In other times, the Commission argued that the prohibitions should be interpreted with due regard to their impact on other social policies. In 1993, it stated that the

[p]rotection of culture is also a concern that has always been borne in mind in applying the competition rules that affect businesses. Although culture is not mentioned by name in Articles [101 and 102 TFEU], the Commission takes account of the cultural dimension when investigating cases in the light of those provisions. Yet the aim is not to frame a policy on culture or to make value judgements in applying the provisions, but rather to assess business practices with due regard to the repercussions they could have on the Community’s cultural policy.Footnote 118

The annual reports up to the late-1990s have also ascribed ordoliberal motives to the competition law prohibitions, especially in the context of the protection of SMEs.Footnote 119 The Commission explained, for example, that conducted adopted ‘to eliminate a smaller competitor constitutes one of the worst forms of infringement of Article [102 TFEU]’.Footnote 120 Similarly, it emphasised the importance of allowing new participants to freely enter markets and compete with existing market players,Footnote 121 and the avoidance of market concentration, in particular in situations of crisis. The Commission argued that although ‘[i]n times of economic stagnation, weak, uncompetitive enterprises inevitably go out of business, driven out by a process of natural selection’, such a process is ‘desirable only up to a certain extent. Where economic difficulties persist, there is a danger that structural changes would be undesirable for competition, because they intensify concentration and economic power’.Footnote 122

This rhetoric was gradually abandoned in favour of a consumer welfare centric approach. Early references to benefits for consumers were evident already from the early 1990s.Footnote 123 Yet, following the adoption of the Green Paper on Vertical Restrictions in 1996, the annual reports stressed the more economic approach guiding the application of the prohibitions and the focus on the impact on consumer welfare.Footnote 124

The transformation in the economic imaginary of competition embedded in the interpretation of the competition law prohibitions is significant. The prohibitions impose strong restrictions on the conduct of business and are often accompanied by heavy sanctions. Even in this ‘hard’ context, and despite the lack of legal competence to alter the scope of the law,Footnote 125 the Commission was able to transform the concept of competition in Articles 101 and 102 TFEU towards a neoliberal interpretation as a matter of policy change rather than law. In other words, the scope of the prohibition was significantly changed by means of interpretation of the notion of competition, without a need to alter EU primary or secondary laws. This demonstrates the flexibility afforded by the lack of a clear definition of competition.

B. Exceptions and justifications

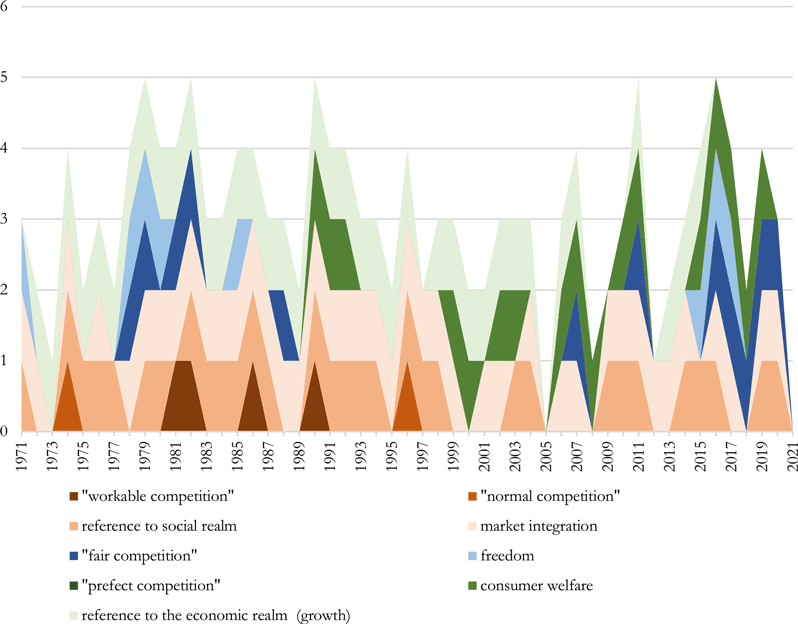

Figure 3 reports another remarkable change to the economic imaginary of competition in the context of the exceptions and justifications for anti-competitive conduct.

Figure 3. Exceptions and justifications.

Similarly to the context of the prohibitions, the Figure reports the strong prevalence of Keynesian theory from the 1970s and throughout the 1990s. The exceptions and justifications granted to otherwise anti-competitive behaviour were linked to the importance of planning (eg, elimination of overcapacity)Footnote 126 and by reference to the social realm (eg, environmental considerations,Footnote 127 sports,Footnote 128 ethical rules of professions,Footnote 129 regional cohesion,Footnote 130 and employmentFootnote 131). The Commission noted that potentially anti-competitive practices could only be accepted if they benefit not only consumers, but also the ‘legitimate interests of workers, users and consumers. These persons should be allowed a fair share of the benefits derived by firms from agreements that restrict competition between themselves’.Footnote 132 Following the Metro judgement, in the 1980s, the Commission often linked this approach to the workable competition standard.Footnote 133

Informed by Keynesian theory, the Commission also considered industrial policy interests. It justified restriction of competition that would increase the competitiveness of EU firmsFootnote 134 or promote the integration of the EU markets.Footnote 135 The exemption of Article 101(3) TFEU, for example, was understood as ‘more than just a means of lifting the ban on restrictive practices’, as a tool giving the Commission ‘the ability to open up cooperation possibilities for firms which enable them to implement an industrial plan and increase their competitiveness’.Footnote 136

The emphasis placed on social benefits had gained further importance toward the 1990s, as regulated sectors have increasingly opened up to competition.Footnote 137 The Commission explained that alongside the benefits associated with competition ‘there has to be a proper balance between this drive for economic efficiency and the need to take account of the social dimension and to maintain a universal service, or in the case of sectors such as gas and electricity to maintain security of supply’.Footnote 138 According to the Commission, ‘[t]he basic question in these sectors is how to arrive at solutions which restrict competition and the fundamental freedoms of Community law as little as possible, while at the same time preserving a public service’. Footnote 139

Other justifications and exceptions were directed at the protection of SMEs,Footnote 140 as a reflection of a ordoliberal notion of competition. The Commission declared that it made ‘liberal use’ of its power to grant exemption under Article 101(3) TFEU ‘in favour of small SME’.Footnote 141 This approach was warranted by the need ‘to strengthen the position of small and medium-sized undertakings’, especially at times of crisis as they are ‘an important source of jobs and serve to promote adaptation to the necessary structural changes’, to allow them ‘to cope better with competition from larger undertakings’. The Commission admitted that it accepted ‘certain major restrictions of competition, in particular in the area of licensing and distribution agreements, as a special concession restricted to small and medium-sized undertakings’.Footnote 142 The special protection offered to SMEs was limited since the mid-1990s, as the Commission declared it shifted the analysis towards market share instead of the size or turnover of the firms.Footnote 143

Alongside the Keynesian and ordoliberal influences, economic efficiencies and consumer benefits also warranted accepting some restrictions of competition. In the early years, they were mostly invoked in addition to other benefits to the economy or society at large.Footnote 144 From the beginning of Commissioners Van Miert’s tenure in 1993 onwards, they were gradually used as a stand-alone justification and were tied to the economic notion of consumer welfare.Footnote 145

Figure 3 points to a drastic change following the modernisation of competition law enforcement in 2004. Since that time, there was almost no discussion about the meaning of competition in context of exceptions and justifications in the Commission’s annual reports. The few cases in which exceptions and justifications were discussed involved very general statements, that have not pertained to a specific case.Footnote 146

This change could partially be explained by the reform of the enforcement setting, introduced by Regulation 1/2003. Following May 2004, the enforcement is based on self-assessment of firms rather than on notifications, and the Commission tends to close investigations into suspected infringements that can be justified without issuing a formal or informal decision.Footnote 147

Nevertheless, the findings of Figure 3 are remarkable because they demonstrate that the Commission has chosen not to use its annual reports to reveal the reasons justifying closing such investigations. This is not an obvious choice. The nature and scope of the exceptions and justifications are subject to a heated debate – both positively and normatively. Difficult questions arise, for example, as to when the competition law prohibitions should be limit in favour of promoting sustainability, workers’ rights, and the digital economy.Footnote 148 As the Commission generally refrains from adopting formal or informal decisions declaring that a certain practice does not infringe Articles 101 or 102 TFEU and explaining its position,Footnote 149 its annual reports appear to be a natural forum for communicating its interpretation. Such reporting could have increased compliance to the competition rules as well as the transparency and accountability of the Commission’s action.Footnote 150 The Commission, however, did not clarify whether it believes that the neoliberal transformation in the imaginary of competition was limited to defining what types of practices should fall within the scope of the prohibition, or whether it should also extend to the justifications for an otherwise anti-competitive practice.

C. Aims and mandates

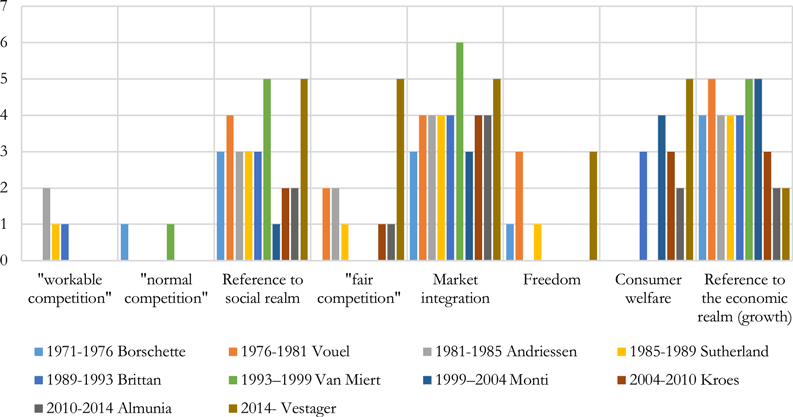

In striking contrast to the prohibitions and the exceptions and justifications, Figure 4 reveals that there has been only very limited transformation in the economic imaginary of competition when it comes to the aims and mandates of competition law and policy. The Commission’s annual reports throughout the years have referred to a relatively consistent mix of Keynesian, ordoliberal, and neoliberal notions.

Figure 4. Aims and mandates.

The aims and mandates clearly express some Keynesian notions. First, there is a strong emphasis on the role of competition in ensuring market integration. From the very first annual report in 1971, and throughout the years, competition policy was described as a complementary measure to the EU free movement rules, ensuring that private firms will not re-establish national market divisions that were previously put in place by Member States’ protectionist measures.Footnote 151 Competition policy, thereby, was described as an ‘important instrument for creating a Community-wide market free of internal barriers’.Footnote 152 In the late-1980s and 1990s, in preparation for the completion of the single market, more emphasis was placed on preventing regulatory trade barriers and on the opening up of recently privatised or highly regulated markets.Footnote 153

The market integration aim was also linked to the EU’s industrial policy. Competition policy was not only directed at preserving competition, but also encouraging some ‘cooperation, reorganisation and combination’ among firms to promote the EU industrial policy, that is ‘to render Community enterprises as competitive as possible both inside and outside the Common Market’.Footnote 154 Moreover, competition was seen as a tool to foster market integration by harmonising public intervention as a response to a crisis.Footnote 155

Second, the annual reports referred to the role of competition in the social realm. Competition was described as a means to ensure a wide host of policies, including employment, fighting inflation, and improving the standard of living.Footnote 156 In 1979, for instance, the Commission noted that

the proper functioning of the market mechanism is not in itself sufficient to ensure that other objectives are attained beyond those of greater productivity and competitiveness of Community firms. If we are to advance towards greater economic and social justice, other Community policies must be pressed into service, always of course ensuring that they are consistent with the competition policy.Footnote 157

Competition was perceived as part of the EU’s response to economic crisis, especially during the 1980s.Footnote 158 The Commission observed the ‘far-reaching and recurrent consequences’ of the crisis, the removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers in international trade, and the growing competitive capacity of developing countries have ‘hastened the international division of labour and shown up certain defects in the economic fabric of the Community’.Footnote 159 Against this backdrop, ‘competition policy cannot succeed without a stamp of approval from the social and political forces. In current circumstances in particular, the Commission’s competition policy not only has to sustain effective competition; it has to support an industrial policy which promotes the necessary restructuring’.Footnote 160 The Commission declared that it would endorse cooperation among firms particularly to protect the EU industry against ‘competitive conduct incompatible with international trade law’.Footnote 161

Third, following the Metro Judgement, in the 1980s the Commission embraced the notion of workable competition as the model of EU competition policy. It clarified that while the EU is based on a market economy, its competition policy ‘is not based on a laissez-faire model, but is designed to maintain and protect the principle of workable competition’. In particular, ‘decisive importance is attached to the interaction between competition policy and the policies which contribute to the attainment of a single market, where conditions are similar to those on national markets’.Footnote 162 Explicit reference to workable competition did not appear in the Commission’s annual reports after the 1990s. At times, it declared that it must ensure ‘the right amount of competition in order for the Treaty’s requirements to be met and its aims attained’ rather than perfect competition.Footnote 163 Yet, gradually, the Commission shifted to the more economic approach, emphasising the positive effects of competition on economic growth.

Keynesian notions of competition, therefore, justified a broad and holistic approach to competition. Along those lines, the Commission declared that it would be ‘wrong to look at the Community’s competition policy in isolation from its other policies (…) Where the Commission under the competition rules has to assess agreements, practices, government regulations and State aids, it will take a more favourable view if they pursue an objective which is in line with the Community’s policy in the relevant area’. Footnote 164

In parallel, ordoliberal ideas of ‘fair competition’ and of individual freedom appeared from the late-1970s to the 1980s. In 1979, for example, the Commission maintained that ‘competition carries within it the seeds of its own destruction’, warning against an ‘excessive concentration of economic, financial and commercial power’.Footnote 165 It declared that the EU competition system requires that the conditions under which competition takes place ‘remain subject to the principle of fairness in the market place’. This includes three aspects: equality of opportunity for all commercial operators in the common market limiting favouring of some firms by states; adapting the competition rules so as to pay special regard in particular to SMEs lacking market power; and taking into account ‘the legitimate interests of workers, users and consumers’.Footnote 166

In its 1985 report, the Commission linked the protection of competition to democratic values. The Member States, according to the Commission

share a common commitment to individual rights, to democratic values and to free institutions. It is those rights, values and institutions at the European and national levels that provide necessary checks and balances in our political systems. Effective competition provides a set of similar checks and balances in the market economy system. It preserves the freedom and right of initiative of the individual economic operator and it fosters the spirit of enterprise. It creates an environment within which European industry can grow and develop in the most efficient manner and at the same time take account of social goals. Competition policy should ensure that abusive use of market power by a few does not undermine the rights of the many.Footnote 167

The 1990s experienced a growing influence of neoliberal ideas. While the role of competition policy in fostering economic growth, optimal allocation of resources, and innovation was always present,Footnote 168 from the early 1990s the Commission began to emphasise the benefits competition brings to consumers – rather than the general public. Footnote 169 Since the mid-2000s, the Commission explicitly declares that Article 101 TFEU aims ‘to protect competition on the market as a means of enhancing consumer welfare’ Footnote 170 and that the ‘main thrust of competition policy should be on maximizing consumer welfare’. Footnote 171 Yet, it also still recourse to vague expressions such as that the ‘ultimate aim of competition policy is to make markets work better – to the advantage of households and businesses’. Footnote 172

While the aim of consumer welfare has clearly gained a hold, Figure 4 shows that it was developed side-by-side to Keynesian and ordoliberal ideas. In 2020, for example, the Commission still insisted that ‘[c]ompetition policy also evolves in tandem with societal, economic and regulatory changes’.Footnote 173 In particular, the Figure reveals that the objective of fairness has re-entered the discourse towards the 2010s. Commentators largely attributed this trend to Commissioner Vestager, which was reported to mention fairness in more than half of her public remarks since she took office in 2014.Footnote 174 The growing reference to fairness is also mirrored by the annual reports published during her tenure,Footnote 175 yet fairness was also mentioned before, during the years of Commissioners’ Kroes Footnote 176 and Almunia Footnote 177 leadership.

The meaning of ‘fairness’ in the recent annual reports is ambiguous. The 2016 report seem to equate fairness with ordoliberal or Keynesian notions by quoting the State of the Union speech of the President of the European Commission Juncker. Juncker labelled the creation of a ‘fair’ playing field in Europe, by which ‘consumers are protected against cartels and abuses by powerful companies’ as the ‘social side of competition law’.Footnote 178 The annual report ties the enforcement of competition law to ensuring that ‘there is a voice for the consumers’. Competition contributes towards ‘a society that gives people choice, stimulates innovation, prevents abuses by dominant players, and drives companies to make the most of scarce resources thus contributing to addressing global challenges like climate change’.Footnote 179

The very broad meaning ascribed to the aims and mandates of competition should perhaps not come as a surprise: this is a relatively ‘soft’ context, in the sense that the aims and mandates do not directly impose legal obligations; and a broad formulation of the aims and mandates can increase the political support towards EU competition law. As summarised by the Commission in 1993, ‘[a] competition policy that did not have an impact on these policies [industrial, cultural, and environmental goals, growth, and employment] or was not influenced by them would be marginalized and of less relevance’. Footnote 180

The gap between the interpretation of the notion of competition in the ‘hard’ context of the prohibitions and exceptions and justifications and the ‘soft’ context of the aims and mandates, is also highlighted by looking at the findings according to the term of each Commissioner for Competition. To this end, Figure 5 presents the interpretations of the aims and mandates of competition during the tenure of each Commissioner. For each interpretation, the bars representing the number of annual reports reflecting such interpretation during each of the Commissioner’s tenure are ordered chronologically from left to right, allowing to observe trends in the meaning ascribed to the aims and mandate of competition over time.

Figure 5. Aims and mandates – according to Commissioner.

In particular, the Figure demonstrates that Commissioner Vestager invoked benefits relating to the social realm, market integration, individual freedom, and ‘fairness’ when describing the aims and mandates of competition, while almost exclusively focusing on neoliberal notions when describing the prohibitions (as reported by Figure 2).

The broad construction of the economic imaginary can increase the legitimacy of EU competition policy. At the same time, the gap between the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ contexts of competition give raise to a concern that the broad economy imaginary in the context of the aims and mandates does not actually reflect the operation of the notion of competition in practice. The broad meaning of competition in the context of aims and mandates, moreover, renders this concept inoperable. The Commission’s annual reports do not set a hierarchy between the different aims and mandates nor offer guidance on how to reconcile conflicts. They cannot, therefore, direct the execution of the competition policy.

D. Enforcement priorities

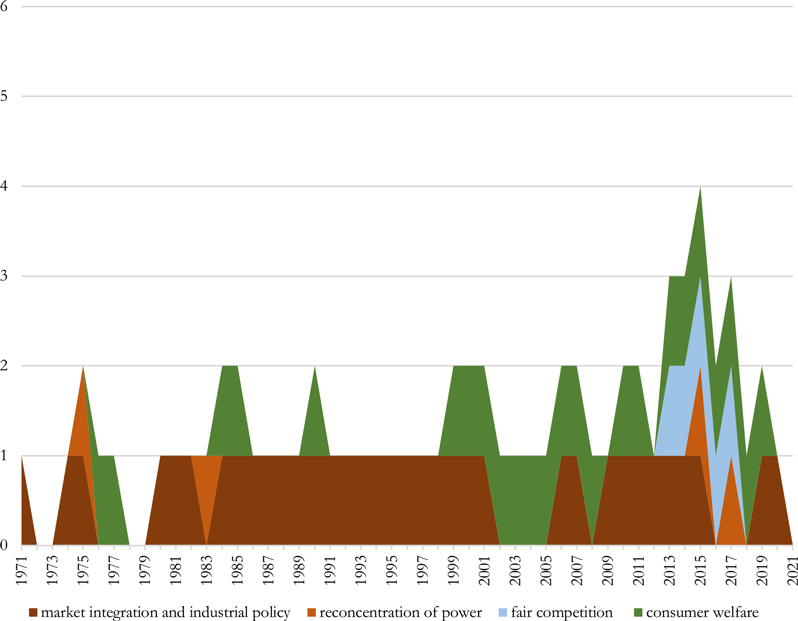

Finally, Figure 6 summarises the development of the economic imaginary of competition as reflected in the description of the Commission’s enforcement priorities in its annual reports. The Figure shows that despite the growing importance of the neoliberal consumer welfare notion from the late-1990s, market integration and industrial policy – as well as some notions of fairness – are still key. Fewer enforcement priorities were defined by the wish to limit the concentration of power,Footnote 181 and protection of SMEs,Footnote 182 but in recent years, they were linked to the emergence of digital markets.Footnote 183

Figure 6. Enforcement priorities.

The importance of furthering market integration and the EU’s industrial policy was clearly reflected by the Commission’s enforcement priorities up until the 2000s.Footnote 184 In the 1970s, the Commission openly declared that it would direct its enforcement efforts toward fighting agreements that had the most negative impact on cross-border trade, rather than on competition as such.Footnote 185 This called for directing the enforcement efforts to combat vertical agreements.Footnote 186

Similar justifications manifested until the late-1990s. In 1993, the Commission explained that its priorities were ‘largely determined by the contribution which competition policy can make to the Community’s objective of growth, competitiveness and employment’ which ‘always been one of the raisons d’etre of competition policy’. In particular, ‘[t]he completion of a genuine internal market and an effective industry policy (.. .) implies the need for renewed vigour in competition policy in areas where it complements and enhances these objectives’.Footnote 187 During that period, the Commission also focused on enforcement in newly liberated sectors and the opening up of markets which were mostly confined to national borders.Footnote 188

From the beginning of Commissioner’s Monti tenure in 1999 onwards, the more economic approach warranted shifting the enforcement priorities towards combating cartels.Footnote 189 The Commission affirmed that by concentrating on consumer welfare, it could ‘better focus its limited resources on the most harmful agreements between firms, such as cartels which effectively have no pro-competitive effects and are therefore in practice always prohibited’. Footnote 190 Similarly, it stated that when adopting its enforcement priorities guidance on exclusionary abuse under Article 102 TFEU, ‘the economic approach aimed at maximising consumer welfare has become embedded into the antitrust enforcement framework’. Footnote 191 Hence, while harm to consumer interest had sometime directed the setting of the enforcement priorities also in the past,Footnote 192 Monti’s tenure represented a systematic shift towards a focus on practices harming consumer welfare.

At the same time, the Commission still invokes market integration and industrial policy considerations when setting its enforcement priorities.Footnote 193 This was summarised in its 2010 report noting that

The broadened focus encompassing consumer welfare – ensuring that markets can deliver the best outcomes for consumers in terms of prices, output, innovation and quality and diversity of products and services – does not mean that the internal market is no longer relevant. On the contrary, in legal terms, the nexus between competition policy and the internal market was confirmed by the Lisbon Treaty. Moreover, as the crisis has shown, the integrity of the internal market must never be taken for granted. The Commission must be prepared to use all its available tools whenever this core asset of the European Union comes under attack. Footnote 194

Likewise, the reference to ‘fairness’ in competition law, which characterised the ‘soft’ context of the aims and mandates, was also evident in Commissioner Vestager’s account of the enforcement priorities.Footnote 195 In fact, during her tenure, the reference to consumer welfare in this context was often applied side by side the fairness goal.Footnote 196

Setting the enforcement priorities lies somewhere between the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ contexts. On the one hand, enforcement priorities are a means to concretise and distinguish the limits between legal and illegal behaviour, suggesting this is a ‘hard’ context with the prohibitions and the exceptions and justifications. On the other hand, the enforcement priorities are greatly left to the Commission’s discretion, suggesting that this is a ‘soft’ context, with the aims and mandates. Correspondingly, the economic imaginary of competition was also developed in between those two ends when it comes to setting the enforcement priorities: it was strongly influenced by neoliberal theory, while maintaining some Keynesian and ordoliberal influences.

6. Conclusion

‘Competitiveness’, as the Commission observed in its 2013 report, ‘is a composite and multi-dimensional concept’.Footnote 197 This paper showed that vagueness and lack of precision have characterised the notion of competition from its early non-technical usage in Roman Law, during the drafting of the Treaty of Rome, and in the application of the EU competition law and policy up until the present day.

The notion of competition went mostly undefined by EU primary and secondary laws and the Commission’s and EU Courts’ decisional practice, and this gap was not filled by the Commission’s annual reports. The reports reflect a mix of Keynesian, ordoliberal, and neoliberal notions of competition. There is no single economic imaginary of competition or a clear, single transformation of the meaning of competition; multiple concepts of competition were developed through time, sometimes applied in parallel and even contradicting each other.

More specifically, a CDA of the Commission’s annual reports revealed that the economic imaginary of competition had acquired different meanings according to the context in which it was interpreted. A strong transformation occurred in the ‘hard’ context of defining the scope of the prohibitions on anti-competitive agreements and abuse of dominance position. The rhetoric of correcting and strengthening the internal market and correcting market failures was almost completely abandoned in favour of a focus on consumer welfare. A similar transformation, yet to a more limited extent, also appeared when it comes to the exceptions and justifications for anti-competitive conduct and to the setting of enforcement priorities. Yet, almost no transformation was reported when it comes to the ‘soft’ aims and mandates of competition. While Keynesian and ordoliberal ideas have characterised the discourse up until the late-1990s, since then the Commission referred to consumer welfare as a supplementary, rather than a new, meaning of competition.