Craniosynostosis is the premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures, estimated to occur in approximately 1/2500 live births.Reference Johnson and Wilkie 1 Rarely, secondary craniosynostosis may occur in a previously open suture following the primary repair of the pathological suture.Reference Yarbrough, Smyth, Holekamp, Ranalli, Huang and Patel 2 - Reference Agrawal, Steinbok and Cochrane 7

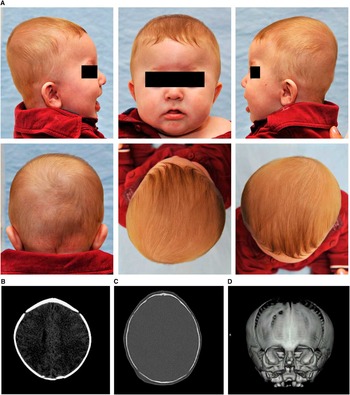

A 6-month-old male presented with trigonocephaly (Figure 1A). A preoperative computed tomography scan was obtained, which demonstrated closure of the metopic suture (Figure 1B-D) and bilateral open coronal sutures. The decision was made to concentrate surgically on the frontal contour of the skull. The child underwent a metopic strip craniectomy and bifrontal rotational craniotomy. No surgical correction of the supraorbital bar was attempted. The frontal craniotomies were barrel staved and contoured to improve the trigonocephaly with an absorbable plating system. The pterion were released bilaterally. There was no laceration of the dura or any dissection of the coronal suture and dural interface.

Figure 1 A Photograph of 6-month-old patient with trigonocephaly resulting from metopic craniosynostosis, (B) computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain, (C) CT scan of the bone windows, and (D) three-dimensional CT scan demonstrate fusion of the metopic suture and patency of the coronal, lamboid, and sagittal sutures.

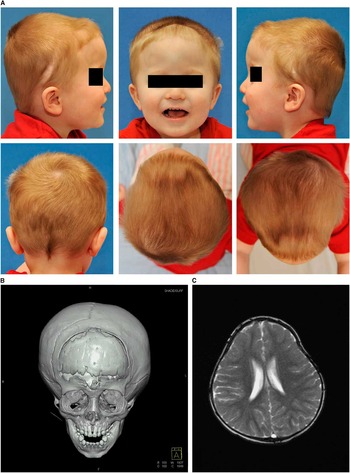

The patient was seen again 9 months postoperatively. His head circumference was normal, but abnormal bone formation was noted over the frontal bone and a suboptimal surgical result was present (Figure 2A). Interval fusion of the left coronal suture was noted via computed tomography scan, confirming the presence of left coronal synostosis (Figure 2B). No intracranial abnormality was observed (Figure 2C). The patient was admitted for cranial vault reconstruction. A repeat two-piece bifrontal craniotomy was lifted followed by removal of the supraorbital bar. The orbital bar and bifrontal bone flap were then contoured and replaced using an absorbable plating system.

Figure 2 (A) Photograph of the 15-month-old patient with suboptimal cosmetic result caused by left secondary coronal synostosis. (B) Three-dimensional computed tomography scan of the skull demonstrating a new left unilateral coronal synostosis. (C) fast imaging with steady-state free precession (FISP) magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

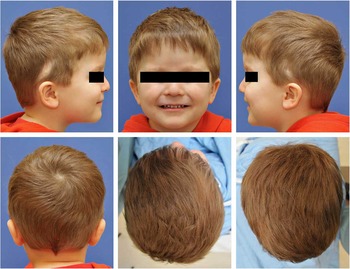

On genetic testing, the child did not meet the criteria for any syndrome, and FGFR3 testing was negative. The patient has since recovered and no other deformities have been noted as of a 2-year follow-up (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Photograph of the 3-year-old patient at 2-year follow-up after secondary synostosis repair.

Metopic craniosynostosis is classically the third most common craniosynostosis, although its incidence has increased.Reference Kolar 8 Secondary synostosis following surgical repair of a primary craniosynostosis is a recognized but rare clinical entity.Reference Yarbrough, Smyth, Holekamp, Ranalli, Huang and Patel 2 - Reference Agrawal, Steinbok and Cochrane 7 We report the first known case of unicoronal synostosis secondary to a surgical repair of metopic synostosis.

There are several theories pertaining to the pathogenesis of craniosynostosis.Reference Johnson and Wilkie 1 , Reference Esmaeli, Nejat, Habibi and El Khashab 6 , Reference Karabagil 9 Some implicate metabolic or genetic primary bone pathologies. Mutations to FGFR genes as well as to EFNB1, TWIST1, POR, and FBN1 have been linked to syndromic and nonsyndromic multisutural craniosynostosisReference Greene, Mulliken, Proctor, Meara and Rogers 10 - Reference Panigrahi 12 with FGFR and EFNB1 accounting for ~25%.Reference Panigrahi 12 Although the child did not exhibit findings of syndromic craniosynostosis (Crouzon, Apert, Pfeiffer, and Muenke syndromes), genetic factors may promote delayed sutural fusion. The progressive nature of this case might alternatively suggest that an osseous pathology, perhaps from the stress of surgery or a genetic predisposition, may be responsible for this patient’s phenotype. Arnaud et al. postulated that surgery might abrogate signaling between the dura and the calvarial sutures, which normally maintains sutural patency,Reference Arnaud, Capon-Degardin, Michienzi, Di Rocco and Renier 4 but the dura was not damaged during surgery.

Although secondary craniosynostosis is uncommon, it is an entity that surgeons must be aware of after suboptimal cosmetic results following craniosynostosis surgery.

Disclosures

GL has served as a speaker and received honoraria from AO North America. All other others have nothing to disclose.